Victorians! discussion

This topic is about

Dombey and Son

Archived Group Reads 2023

>

Dombey and Son - Week 10: Chapters LII - LVI

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

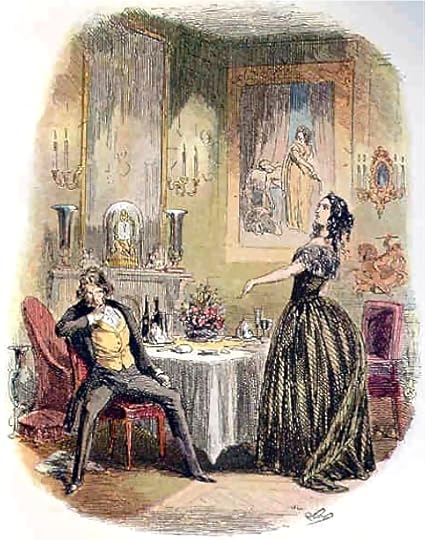

We next go to Dijon, where Edith is ensconced in lonely splendor in a luxurious hotel suite. Two servants come to serve her dinner and hard upon their heels is Carker, smiling. He embraces Edith and addresses her as his charming wife, causing her to shrink and shiver at his touch. After the servants depart, he speaks to her with familiarity, chiding her for not hiring a maid to attend her, complimenting her beauty, and calling her “my love.” It sounds as though she demanded that he arrange a safe haven for them outside of England before she would consent to be with him, for he refers to them as “hard, unrelenting terms” but that they “make the present more delicious and more safe” before revealing that they will fly to Sicily. He is clearly expecting her to be welcoming and affectionate to him, for “he was coming gaily towards her, when, in an instant, she caught the knife up from the table” and threatens to murder him if he comes one step closer (759). He is stunned by the “sudden change in her, the towering fury and intense abhorrence sparkling in her eyes,” and “rage and astonishment” are reflected on his face (759). Edith makes her hatred of him crystal clear as she reminds him of their interactions over the last two years, assuring him that even if she could have forgiven Dombey all the other reasons she had for despising him, having Carker for his counsellor and favorite would have still been enough for her to hate her husband as she does. She accuses Carker of knowing of her background, of her self-loathing as a result of it, of her reasons for agreeing to marry Dombey, and using all of this to pursue her. She finds herself trapped in a hell where she is shamed and disrespected by her husband on one hand, then experiences the same from the other man that her own husband forces her to endure, even while he pursues her under her husband’s very nose. She finds herself “forced by the two from every point of rest I had–forced by the two to yield up the last retreat of love and gentleness within me, or to be a new misfortune on its innocent object–driven from each to each, and beset by one when I escaped the other,” causing her anger to drive her to distraction (761).

We learn that the night before Edith’s flight, the night when the argument broke out at dinner and Edith told Dombey exactly how she felt and that she would not be accommodating him then or ever, Carker met with Edith in her room. Having gone to her room, he proposed that they run away together and makes it clear that this meeting between them, along with the others that he required to be in private, would all be considered compromising to her reputation, and that her reputation now depended on his silence.

The way I read this is that Edith sees Carker trying to spring the trap on her, but she sets one of her own for him. He thinks that possessing Dombey’s wife will be his ultimate revenge on his employer and will also humble her. She agrees to elope with him, causing him to abandon his high position and respectability, but determines that he will never possess her, so it will be for nothing. She leaves him, his revenge incomplete, and now with her vengeful husband on his heels. She taunts him that he has “fallen on Sicilian days and sensual rest, too soon. You might have cajoled, and fawned, and played your traitor’s part, a little longer, and grown richer. You purchase your voluptuous retirement dear!” (763). She ends by gleefully telling him that he has “been betrayed, as all betrayers are” and that his whereabouts are known (764). She claims to have seen her husband in a carriage in the street. She slips away like a wraith, and Carker is forced to sneak off like a thief and a coward.

Carker decides to return to England, unable to bear the thought of being hunted through the streets of a foreign city, alone and friendless, especially in a place where assassins are available for hire. He feels scattered and discombobulated, unable to think about “the crash of his project for the gaining of a voluptuous compensation for past restraint; the overthrow of his treachery to one who had been true and generous to him, but whose least proud word and look he had treasured up, at interest, for years–for false and subtle men will always secretly despise and dislike the object upon which they fawn, and always resent the payment and receipt of homage that they know to be worthless” (770). So is the plan that Edith wrecked one of blackmail? Did Carker plan to blackmail Dombey to keep him silent about his escapades with Edith, forbearing to further drag the Dombey name in the mud after the initial humiliation of the elopement? So her plan was actually quite a good one!

Dickens gives us a streaming description of the different vistas Carker passes through on his wild journey, trying to escape the pursuit he is convinced is right behind him. He is enveloped in a haze of “shame, disappointment, and discomfiture,” turning endlessly on a wheel of “fear, regret, and passion” and always, “useless rage” (772). The description encapsulates the fragmented state of the journey as they start and stop, changing horses and eating, but also the frenetic pace of a fearful flight from inexorable danger following and drawing, in Carker’s feverish brain, ever nearer. The people and places Carker sees outside of the carriage window seem to blend together and become mingled with visions from his past. At the same time, they all seem to come down to the “same monotony of bells and wheels, and horses’ feet, and no rest” (773). This phrase is used repeatedly, emphasizing the effect of the lack of sleep on the kaleidoscopic jumble of images that are overwhelming Carker. I love how Dickens uses this literary device and his use of anaphora by beginning each phrase with “Of” to show how the endless parade of sights and sounds, despite their wide variety, still boils down to “the same monotony.”

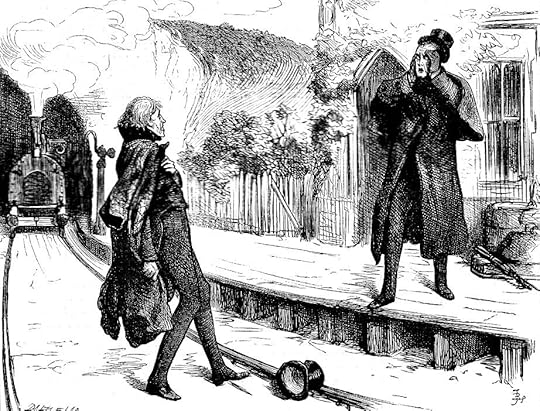

He switches from the carriage to a railway car and finds a tavern he can take refuge in, but he is still unable to sleep. At one point he believes that he has been found, but the approaching beast is not Dombey, but the train. He thinks of the trains as devils but finds himself wandering the lane beside the tracks, wondering when another will pass. He is repulsed and fascinated by the trains and returns to his room, but is unable to sleep and lies awake, listening for the passage of the trains and troubled by the visions of his journey and the “old monotony of bells and wheels and horses’ feet” (777). He is walking near the tracks, awaiting the train that he has booked passage on, when he looks up and sees Dombey. Their eyes meet, and Carker takes a few steps backward–right onto the tracks! He turns his head in time to see the train bearing down on him before he is “beaten down, caught up, and whirled away upon a jagged mill, that spun him round and round, and struck him limb from limb, and licked his stream of life up with its fiery heat, and cast his mutilated fragments in the air” (779). Whew! That is a pretty gory description for a Victorian, don’t you think? We end with them shooing the dogs that are sniffing at Carker’s blood on the road away. Shall we have a moment of silence for Mr. Carker, the Manager, now that he is literally a stain on the road?

Now that justice has prevailed for some of our characters, let’s turn to a happier scene. At the Midshipman, everyone is beatifically witnessing the contentment of Walter and Florence as they plan for their wedding and their forthcoming journey as Walter seeks his fortune. Susan Nipper and Florence have been reunited, much to their joy, and Susan can hardly believe that her little lamb is about to be married. She is gradually brought to realize that she cannot accompany Florence and Walter on their sea journey.

The engaged couple’s voyage means that they cannot accumulate a lot of material gifts, so those nearest and dearest to them are limited in what they can bestow on the pair for a wedding gift. Captain Cuttle, with difficulty, restrains his gifts to Florence to a workbox and dressing case, but each is “the very largest specimen that could be got for money.” He is torn between “extreme admiration of them, and dejected misgivings that they were not gorgeous enough” and frequently dove out into the street “to purchase some wild article that he deemed necessary to their completeness.” He felt his gifts finally achieved perfection one day when he had “FLORENCE GAY engraved upon a brass heart inlaid over the lid of each” (788).

Florence is very happy. Safe within the sheltering walls of the Midshipman, within the circle of Walter’s loving arms and surrounded by those others who love her, she flourishes. She thinks often of her departed brother, but only remembers her father as she saw him sleeping that time, never as she last saw him. In the evenings, the company would sit contentedly together, the Captain and Mr. Toots playing cribbage while Susan Nipper advised Toots. During these times, the Captain struggles to express himself appropriately. Out of respect for Florence, he feels that he should be more subdued, but his instinct is to shout his happiness out to the world. At times, his happiness would “take such complete possession of him that he would lay down his cards, and beam upon them, dabbing his head all over with his pocket-handkerchief.” Mr. Toots, having his attention drawn thus to the little bubble of love that Walter and Florence are enveloped in, rushes out of the room to indulge his feelings in privacy. His exodus is a sign to the Captain that he needs to take it down a notch. When Toots returns, the Captain turns his attention back to his cards, “with many side winks and nods, and polite waves of his hook to Miss Nipper, importing that he wasn’t going to do it anymore.” In his attempt to “discharge all expression from his face, he would sit, staring round the room, with all these expressions conveyed into it at once, and each wrestling with the other” (790-91). His excitement for Walter and Florence always wins, and Mr. Toots would have to rush out again, and it would all start over. I do so love Captain Cuttle! 🙂

We learn that the night before Edith’s flight, the night when the argument broke out at dinner and Edith told Dombey exactly how she felt and that she would not be accommodating him then or ever, Carker met with Edith in her room. Having gone to her room, he proposed that they run away together and makes it clear that this meeting between them, along with the others that he required to be in private, would all be considered compromising to her reputation, and that her reputation now depended on his silence.

The way I read this is that Edith sees Carker trying to spring the trap on her, but she sets one of her own for him. He thinks that possessing Dombey’s wife will be his ultimate revenge on his employer and will also humble her. She agrees to elope with him, causing him to abandon his high position and respectability, but determines that he will never possess her, so it will be for nothing. She leaves him, his revenge incomplete, and now with her vengeful husband on his heels. She taunts him that he has “fallen on Sicilian days and sensual rest, too soon. You might have cajoled, and fawned, and played your traitor’s part, a little longer, and grown richer. You purchase your voluptuous retirement dear!” (763). She ends by gleefully telling him that he has “been betrayed, as all betrayers are” and that his whereabouts are known (764). She claims to have seen her husband in a carriage in the street. She slips away like a wraith, and Carker is forced to sneak off like a thief and a coward.

Carker decides to return to England, unable to bear the thought of being hunted through the streets of a foreign city, alone and friendless, especially in a place where assassins are available for hire. He feels scattered and discombobulated, unable to think about “the crash of his project for the gaining of a voluptuous compensation for past restraint; the overthrow of his treachery to one who had been true and generous to him, but whose least proud word and look he had treasured up, at interest, for years–for false and subtle men will always secretly despise and dislike the object upon which they fawn, and always resent the payment and receipt of homage that they know to be worthless” (770). So is the plan that Edith wrecked one of blackmail? Did Carker plan to blackmail Dombey to keep him silent about his escapades with Edith, forbearing to further drag the Dombey name in the mud after the initial humiliation of the elopement? So her plan was actually quite a good one!

Dickens gives us a streaming description of the different vistas Carker passes through on his wild journey, trying to escape the pursuit he is convinced is right behind him. He is enveloped in a haze of “shame, disappointment, and discomfiture,” turning endlessly on a wheel of “fear, regret, and passion” and always, “useless rage” (772). The description encapsulates the fragmented state of the journey as they start and stop, changing horses and eating, but also the frenetic pace of a fearful flight from inexorable danger following and drawing, in Carker’s feverish brain, ever nearer. The people and places Carker sees outside of the carriage window seem to blend together and become mingled with visions from his past. At the same time, they all seem to come down to the “same monotony of bells and wheels, and horses’ feet, and no rest” (773). This phrase is used repeatedly, emphasizing the effect of the lack of sleep on the kaleidoscopic jumble of images that are overwhelming Carker. I love how Dickens uses this literary device and his use of anaphora by beginning each phrase with “Of” to show how the endless parade of sights and sounds, despite their wide variety, still boils down to “the same monotony.”

He switches from the carriage to a railway car and finds a tavern he can take refuge in, but he is still unable to sleep. At one point he believes that he has been found, but the approaching beast is not Dombey, but the train. He thinks of the trains as devils but finds himself wandering the lane beside the tracks, wondering when another will pass. He is repulsed and fascinated by the trains and returns to his room, but is unable to sleep and lies awake, listening for the passage of the trains and troubled by the visions of his journey and the “old monotony of bells and wheels and horses’ feet” (777). He is walking near the tracks, awaiting the train that he has booked passage on, when he looks up and sees Dombey. Their eyes meet, and Carker takes a few steps backward–right onto the tracks! He turns his head in time to see the train bearing down on him before he is “beaten down, caught up, and whirled away upon a jagged mill, that spun him round and round, and struck him limb from limb, and licked his stream of life up with its fiery heat, and cast his mutilated fragments in the air” (779). Whew! That is a pretty gory description for a Victorian, don’t you think? We end with them shooing the dogs that are sniffing at Carker’s blood on the road away. Shall we have a moment of silence for Mr. Carker, the Manager, now that he is literally a stain on the road?

Now that justice has prevailed for some of our characters, let’s turn to a happier scene. At the Midshipman, everyone is beatifically witnessing the contentment of Walter and Florence as they plan for their wedding and their forthcoming journey as Walter seeks his fortune. Susan Nipper and Florence have been reunited, much to their joy, and Susan can hardly believe that her little lamb is about to be married. She is gradually brought to realize that she cannot accompany Florence and Walter on their sea journey.

The engaged couple’s voyage means that they cannot accumulate a lot of material gifts, so those nearest and dearest to them are limited in what they can bestow on the pair for a wedding gift. Captain Cuttle, with difficulty, restrains his gifts to Florence to a workbox and dressing case, but each is “the very largest specimen that could be got for money.” He is torn between “extreme admiration of them, and dejected misgivings that they were not gorgeous enough” and frequently dove out into the street “to purchase some wild article that he deemed necessary to their completeness.” He felt his gifts finally achieved perfection one day when he had “FLORENCE GAY engraved upon a brass heart inlaid over the lid of each” (788).

Florence is very happy. Safe within the sheltering walls of the Midshipman, within the circle of Walter’s loving arms and surrounded by those others who love her, she flourishes. She thinks often of her departed brother, but only remembers her father as she saw him sleeping that time, never as she last saw him. In the evenings, the company would sit contentedly together, the Captain and Mr. Toots playing cribbage while Susan Nipper advised Toots. During these times, the Captain struggles to express himself appropriately. Out of respect for Florence, he feels that he should be more subdued, but his instinct is to shout his happiness out to the world. At times, his happiness would “take such complete possession of him that he would lay down his cards, and beam upon them, dabbing his head all over with his pocket-handkerchief.” Mr. Toots, having his attention drawn thus to the little bubble of love that Walter and Florence are enveloped in, rushes out of the room to indulge his feelings in privacy. His exodus is a sign to the Captain that he needs to take it down a notch. When Toots returns, the Captain turns his attention back to his cards, “with many side winks and nods, and polite waves of his hook to Miss Nipper, importing that he wasn’t going to do it anymore.” In his attempt to “discharge all expression from his face, he would sit, staring round the room, with all these expressions conveyed into it at once, and each wrestling with the other” (790-91). His excitement for Walter and Florence always wins, and Mr. Toots would have to rush out again, and it would all start over. I do so love Captain Cuttle! 🙂

The next comic moment happens at the church during the reading of the banns for Walter and Florence. Mr. Toots insists on being present, determined to see his unrequited passion to the end, but when their names are read out, he is overcome by his emotions and runs out of the church, followed by a concerned beadle, a pew opener, and two doctors. The beadle presently returns to assure Miss Nipper that Mr. Toots is fine, but she is still embarrassed. This emotion is not mitigated when Mr. Toots suddenly returns and sits “on a free seat in the aisle, between two elderly females” who are there for their weekly dole of bread. In this position, Mr. Toots is “greatly disturbing the congregation, who felt it impossible to avoid looking at him” until he suddenly, overcome with emotion, runs out again. Unwilling to disrupt the service again but desirous of witnessing the event, “Mr. Toots was after this, seen from time to time, looking in, with a lorn aspect, at one or other of the windows; and as there were several windows accessible to him from without, and as his restlessness was very great, it not only became difficult to conceive at which window he would appear next, but likewise became necessary, as it were, for the whole congregation to speculate upon the chances of the different windows.” Mr. Toots’ movements were so eccentric “that he seemed to generally defeat all calculation, and to appear, like a conjuror’s figure, where he was least expected.” Since it was difficult for him to see in, he would remain at each window for a long time, his face close to the glass, “until he all at once became aware that all eyes were upon him and vanished” (794). I laughed out loud at this part. I could just see Toots, popping up like a jack-in-the-box at different windows, staring in mournfully, unaware that everyone is looking at him! LOL

The night before the wedding, their cozy evening is interrupted by an unexpected visitor. Uncle Sol Gill walks in! All are astounded by his arrival. It turns out that he had gone to Barbados, Jamaica, and Demerara in search of Walter, and had written to Captain Cuttle from each of these locations. Unfortunately, these letters had been addressed to Captain Cuttle’s former residence at Mrs. MacStinger’s. Of course, none of these letters were delivered to him, and they all marveled anew at the venomous landlady.

Before Mr. Toots leaves, Walter expresses Florence’s dear love to him and thanks him for his loyalty. Toots leaves with the Chicken, who is disgusted that no one is going to be doubled over. He believes that Toots should not accept losing Florence so easily, so the two decide to part company on this philosophical difference.

So what was your favorite part of this week’s reading? Were you more satisfied by the vengeance, or by the return of the prodigal uncle? What do you think of Edith’s actions? Do you think Carker got his just desserts? Were you surprised by his ending? Dombey and Son is often regarded as one of Dickens’ strictures on industrialization through his descriptions of the encroachment of the railway, but I don’t know. The fact that the train took Carker out is more a point in its favor, don’t you think? What do you think will happen to Edith? Will we see her again? Where do you think Dombey will go from here? Please share your thoughts, questions, or predictions with the group!

The night before the wedding, their cozy evening is interrupted by an unexpected visitor. Uncle Sol Gill walks in! All are astounded by his arrival. It turns out that he had gone to Barbados, Jamaica, and Demerara in search of Walter, and had written to Captain Cuttle from each of these locations. Unfortunately, these letters had been addressed to Captain Cuttle’s former residence at Mrs. MacStinger’s. Of course, none of these letters were delivered to him, and they all marveled anew at the venomous landlady.

Before Mr. Toots leaves, Walter expresses Florence’s dear love to him and thanks him for his loyalty. Toots leaves with the Chicken, who is disgusted that no one is going to be doubled over. He believes that Toots should not accept losing Florence so easily, so the two decide to part company on this philosophical difference.

So what was your favorite part of this week’s reading? Were you more satisfied by the vengeance, or by the return of the prodigal uncle? What do you think of Edith’s actions? Do you think Carker got his just desserts? Were you surprised by his ending? Dombey and Son is often regarded as one of Dickens’ strictures on industrialization through his descriptions of the encroachment of the railway, but I don’t know. The fact that the train took Carker out is more a point in its favor, don’t you think? What do you think will happen to Edith? Will we see her again? Where do you think Dombey will go from here? Please share your thoughts, questions, or predictions with the group!

Chapter 54 has to be one of the most dramatically intense chapters I have listened to. I am listening to Mil Nicholson on Librivox.

Chapter 54 has to be one of the most dramatically intense chapters I have listened to. I am listening to Mil Nicholson on Librivox. Contrast this dark and brooding chapter with Florene & Walters happiness.

Dombey and Son is a wonderful Dicken's darkhorse.

For me, it's chapter 55 that fascinates me - so much that I just had to delve a bit deeper into what Dickens does here. I've made notes on it -

For me, it's chapter 55 that fascinates me - so much that I just had to delve a bit deeper into what Dickens does here. I've made notes on it - 1st Warning: this will be long! forgive me or just skip it!

2nd Warning: contains traces of syntax and semantics!

We are taken into the breathless, feverish, monotonous, stamping rhythm of Carker’s nightmare travel. I just had to have a closer look on how Dickens achieves this effect. What does he do with (and to) language here? - Three aspects jumped out at me from the page: syntax, rhythm, and agency.

I looked at the middle section in particular - what I call by myself the ‘litany’ of the vision. It begins with It was a vision …, goes on for about 70 lines in my PG version - probably more in print, and ends with … and of being at last again in England. The section is prepared by this sentence which introduces both the elements of ‘monotony’ and ‘vision’:

The monotonous ringing of the bells and tramping of the horses; the monotony of his anxiety, and useless rage; the monotonous wheel of fear, regret, and passion, he kept turning round and round; made the journey like a vision, in which nothing was quite real but his own torment.

(on syntax - ) Then the litany begins with It was a vision of long roads, … which is taken up three more times:

… It was a fevered vision of … ,

… A vision of …

… A troubled vision, then, …

These are the only main clauses for the whole litany - and even two of these are elliptical. Technically, the whole litany consists of only 4 full clauses on the pattern of ‘it was a vision of X’, which gets reduced to the elliptical ‘a vision of X’. Each main clause is followed by a sequence of X = phrases introduced by ‘of’. Some of these phrases are long and complex, but everything in them is subordinated to the ‘of’.

The ‘of’-constructions are prepositional phrases which all follow the pattern prep+NP, i.e. the preposition plus a noun phrase (‘of fields’, ‘of a town’, etc.). A noun phrase is a non-finite, static part of speech - only a verb phrase tells us ‘who does what, where, when’. (cf. ‘John bought the cow’ vs. ‘John milks the cow’ vs. ‘John will kill the cow’). So the ‘of’-phrases are basically timeless and action-less. Where they describe events and actions, these are subordinated to the mandate of the noun phrase, and so we get non-finite, nominalised clauses with past and present participles like ‘of … horses … panting’, ‘of long roads left behind’ which are static images without actors and actions (and relevant to the aspect of agency, see below).

(on rhythm -) The only interruption of the of-sequences is the ‘chorus’ of

still the monotony

of bells and wheels,

and horses’ feet,

and no rest

which recurs 6 times in all. This rhythmical refrain is no complete sentence either. One can read the ‘of bells etc.’ sequence as a mini-poem to get the rhythm, so you get two lines with 2 iambic feet, plus one shorter line with an anapest. We actually hear the rhythm of hoofbeats, while the last short line ending on a stressed syllable adds to the impression of a breathless, endless, restless travel.

(on agency -) In the ‘normal’ course of a narrative, we are told about things that happen, and most often, about things that the agent does (and thinks and feels); like ‘Carker fled … he travelled … he saw’ and so on: after all, he is the main character of this chapter.

The main clause pattern - ‘it was a vision of X’ - is the weakest form of statement you can make in English where some verb and subject are required by grammar. Semantically, the expletive ‘it is’ adds nothing to meaning but tempus (it is - it was etc.). It is static and impersonal, and tells nothing about who has the vision nor about the process of envisioning (as in ‘he had a vision’) The vision is just there.

The phrases with ‘of’ (see above) add to the lack of action and agency. We know it is Carker’s vision, but he is erased from the whole ‘litany’ section as an agent. What he does is relegated down into the subordinate, often infinite prepositional phrases, and becomes itself part of the vision that happens to him, e.g. ‘a vision … of getting out and eating hastily’. In this section, Carker is transformed from ‘agens’ to ‘patiens’: Carker the villain becomes Carker the victim.

He gets his agency back after the litany, on arrival in England: He had thought, in his dream, of going …

‘he’ (Carker) is re-installed as the agent, but he does not act yet - he only remembers his vision. It takes another paragraph for him to finally *do* something again (and ‘to slink’ is not exactly a heroic act): With this purpose he slunk into a railway carriage … … with the earlier ominous, menacing railway visions, this sounds more like a surrender than an autonomous action.

With the elliptical sentences, and the many repetitions of the ‘of’-construction, Dickens conveys the long duration and the feverish haste, passivity together with restlessness. As it consists of only 4 sentences, we, as readers, get ‘no rest’ in the text either. We fall in with the rhythm of the horse-drawn carriage (Dickens’ contemporaries knew it from experience), and we see Carker being reduced from villain to victim.

I think the piece is close to perfection when it comes to a match between form and function. Dickens draws on all the registers of his genius to put language into the service of meaning, imagery, and expressivity. … and I have to remind myself repeatedly that this piece of text was written in 1848! It sounds incredibly ‘modern’, expressionistic, with a touch of Dadaism maybe? Dickens was decades ahead of his time in his bold use of language.

(I can forgive him much for the sake of this writing … for example that, IMO, he sacrifices some of the believability and consistency of the Carker character on the altar of linguistic exuberance)

No moment of silence for Mr. Carker as far as I'm concerned. He was pure evil and won't be missed!

No moment of silence for Mr. Carker as far as I'm concerned. He was pure evil and won't be missed!Thanks to Sabagrey for the wonderful analysis of Mr. Dickens use of rhythm and repetition in the escape scene. It is one of the great parts of his talent and reminded me of the opening passage of A TALE OF TWO CITIES.

Dear Captain Cuttle and poor Mr. Toots! They provide comic relief but also genuine emotion in their love of Florence. The image of Mr. Toots peering through the church windows was great comedy.

As for Edith, I believe she played Mr. Carker brilliantly in order to make her escape from Dombey. I can't imagine where she will turn up, but I hope her escape is complete. I see so many parallels between her life and Alice's - as of course Mr. Dickens intended.

Finally, I didn't suspect Mr. Morphin as the mystery gentleman who approached Harriet Carker, but it will be interesting to see how his wish to help the Carkers comes to fruition.

sabagrey wrote: "For me, it's chapter 55 that fascinates me - so much that I just had to delve a bit deeper into what Dickens does here. I've made notes on it ..."

Wonderful syntactical analysis, sabagrey! Thank you so much for sharing that with us. You are so right--the complexity of his structure is often brilliant! It is one of the many things I love about his writing. When you really dig down, you find so many patterns and connections that reveal the craft that went into it.

I would like to hear more about your thoughts on how he sacrificed some of the believability of Carker's character in this scene. I see Carker as a formidable foe, but I can also see him, like so many bullies and manipulators, becoming a coward in an actual physical confrontation. I can also see him as, having had everything go his way for so long in all the setup for this coup de grace, that he has become overconfident and is knocked off his game by being outwitted by Edith, an outcome that he probably never considered as possible. I would love to hear your thoughts, though!

Wonderful syntactical analysis, sabagrey! Thank you so much for sharing that with us. You are so right--the complexity of his structure is often brilliant! It is one of the many things I love about his writing. When you really dig down, you find so many patterns and connections that reveal the craft that went into it.

I would like to hear more about your thoughts on how he sacrificed some of the believability of Carker's character in this scene. I see Carker as a formidable foe, but I can also see him, like so many bullies and manipulators, becoming a coward in an actual physical confrontation. I can also see him as, having had everything go his way for so long in all the setup for this coup de grace, that he has become overconfident and is knocked off his game by being outwitted by Edith, an outcome that he probably never considered as possible. I would love to hear your thoughts, though!

Nancy wrote: "No moment of silence for Mr. Carker as far as I'm concerned. He was pure evil and won't be missed! ..."

That is how I feel, as well, Nancy! Good riddance to bad rubbish! He caused nothing but misery even to those who cared about him.

I also hope that Edith is able to find some peace after her escape. It would be wonderful if she could still have contact with Florence, but she might want to just put that whole chapter of her life behind her.

That is how I feel, as well, Nancy! Good riddance to bad rubbish! He caused nothing but misery even to those who cared about him.

I also hope that Edith is able to find some peace after her escape. It would be wonderful if she could still have contact with Florence, but she might want to just put that whole chapter of her life behind her.

Cindy wrote: " I see Carker as a formidable foe, but I can also see him, like so many bullies and manipulators, becoming a coward in an actual physical confrontation.."

Cindy wrote: " I see Carker as a formidable foe, but I can also see him, like so many bullies and manipulators, becoming a coward in an actual physical confrontation.."I just can't see that - that's all. Carker who waits for years, prepares, knows Dombey, play-acts all the time - he must have taken into account the possibility of persecution. I can't see him lose his head so completely. And Dickens can't either, btw: he has to make use of a hallucination or apparition of a train rushing by or so to shake Carker out of his senses.

’ He was coming gaily towards her, when, in an instant, she caught the knife up from the table, and started one pace back.

"Stand still!" she said, "or I shall murder you!" [Chapter LIV, "The Fugitives," 584]’

Yes, Cindy, during this section my emotions charged along like the horses attached to Carker’s carriage.

I was so glad and at the same time relieved that, after all, the only dishonourable assault on Edith had been two kisses from Carker’s grotesque mouth. Edith turning the tables on Carker was a masterstroke by her, but could she also be cutting her own throat in the process?

In that French boudoir Carker knew that if he tried to lay a finger on her, Edith would take up the knife and kill him or kill herself before she would allow it. His meticulously calculated plans were cut to shreds by such passionate boldness and then, caught off guard, Edith’s clever escape left him reeling.

’She put the knife down upon the table, and touching her bosom wIth her hand, said: ‘I have something lying here that is no love trinket, and sooner than endure your touch once more, I would use it on you — and you know it, while I speak — with less reluctance than I would on any other creeping thing that lives.’

But it was such a tragedy that Edith had to fake her own disgrace and dishonour to stage the elopement in order to get away from Dombey. How can proud Edith survive with no one to turn to and probably very little money, now stranded on the continent?

’ ‘Too late!’ she cried, with eyes that seemed to sparkle fire. ‘I have thrown my fame and good name to the winds! I have resolved to bear the shame that will attach to me — resolved to know that it attaches falsely — that you know it too — and that he does not, never can, and never shall.’

As for Carker, how ironic that this evil man should be crushed under the wheels of a railway engine, having been betrayed by the wayward son of a railway engine driver. All that railway imagery building up to Carker’s demise signalled that something dramatic was about to happen. It happened in such a quiet out of the way place to shatter the peace and tranquility of the scene. And the bloody, ugly death was witnessed by Dombey in all its horrific and grisly details.

’ He saw the face change from its vindictive passion to a faint sickness and terror ’

Hooray for the return of Susan Nipper. I loved how she tried to explain her emotions, almost as unintelligible as Toots on occasions. My favourite was this on being reunited with Florence…..

Hooray for the return of Susan Nipper. I loved how she tried to explain her emotions, almost as unintelligible as Toots on occasions. My favourite was this on being reunited with Florence…..’ for though I may not gather moss I’m not a rolling stone nor is my heart a stone or else it wouldn’t bust as it is busting now oh dear oh dear!’

Do I detect a coming together of Susan and Toots or will their vastly different personalities remain an insurmountable barrier? They both deserve to be loved and what better than to be loved by each other!

Trev wrote: "Do I detect a coming together of Susan and Toots or will their vastly different personalities remain an insurmountable barrier? …..

The same thought has crossed my mind, Trev! Toots did try to steal a kiss from her that one time. I think they both deserve love and want them each to have someone worthy of them. I'm torn between thinking Susan is just too clever for him, and thinking that his good qualities would outweigh his lack of intellect. It would also be a rise in station for Susan. I guess I will leave it up to Dickens to decide! :)

The same thought has crossed my mind, Trev! Toots did try to steal a kiss from her that one time. I think they both deserve love and want them each to have someone worthy of them. I'm torn between thinking Susan is just too clever for him, and thinking that his good qualities would outweigh his lack of intellect. It would also be a rise in station for Susan. I guess I will leave it up to Dickens to decide! :)

sabagrey wrote: "Cindy wrote: " I see Carker as a formidable foe, but I can also see him, like so many bullies and manipulators, becoming a coward in an actual physical confrontation.."

I just can't see that - tha..."

You make a good point. I do agree that pursuit is something Carker should have expected. Maybe he thought that pursuit of a woman who had so dishonored the Dombey name would have been beneath Dombey's dignity. Clearly there was no love lost between them, so Dombey wasn't being driven by his broken heart. It's possible that Carker thought the blackmail scheme would have held Dombey at bay, but actually, blackmail gives Dombey increased motivation to take him out. Could he have thought that they would be safe in their Sicilian hideaway? I'm just grasping at straws! :)

I just can't see that - tha..."

You make a good point. I do agree that pursuit is something Carker should have expected. Maybe he thought that pursuit of a woman who had so dishonored the Dombey name would have been beneath Dombey's dignity. Clearly there was no love lost between them, so Dombey wasn't being driven by his broken heart. It's possible that Carker thought the blackmail scheme would have held Dombey at bay, but actually, blackmail gives Dombey increased motivation to take him out. Could he have thought that they would be safe in their Sicilian hideaway? I'm just grasping at straws! :)

This segment opens with Good Mrs. Brown and Alice waiting in their miserable hovel for expected visitors. The first is Mr. Dombey, whom Mrs. Brown accosted in the street and spoke to, claiming to know the whereabouts of his runaway wife and her accomplice. Mrs. Brown, apparently, was the mysterious source Dombey referred to when talking to Major Bagshot and Cousin Feenix previously. Dombey is there, but clearly against his better judgment. He’s not sure he can trust this information, but it’s the only lead he has, so he decides to stick around despite this being an unworthy setting for one of his stature and magnificence. Mrs. Brown quickly makes her appeal for money, but Alice surprises Dombey by making it clear that it is her hatred for Carker that is driving her participation in this. Mrs. Brown informs him that another person is necessary for the information they need, and that turns out to be young Rob the Grinder. He arrives for the visit he reluctantly promised to make in our last reading, and the trap is set.

Mr. Dombey is hidden in the adjoining room so he can overhear everything Rob says. Rob is greeted with excessive affection by the old woman, who smothers him with caresses until he refuses to cooperate with her. When he refuses to answer her questions, “Mrs. Brown instantly directed the clutch of her right hand at his hair, and the clutch of her left hand at his throat, and held on to the object of her fond affection with such extraordinary fury, that his face began to blacken in a moment” (730). Rob is being strangled again! I wonder if this will make him devote himself heart and soul to Mrs. Brown. It certainly worked that way with Carker!

Rob appeals for help to Alice, who watches the scene, unmoved, and only responds, “Well done, mother. Tear him to pieces!”

Mrs. Brown changes her tactics and declares herself done with Rob, and metaphorically casts him off. She follows this with a threat to “slip those after him that shall talk too much; that won’t be shook away; that’ll hang to him like leeches, and slink arter him like foxes” and she references his knowledge of these people and their ways from “his old games and his old ways” (731). Under this aggression, Rob capitulates and reveals that Carker and Edith actually left separately. That is how they escaped with so little notice. Rob escorted Edith to Southampton and saw her onto the packet the following morning. Mrs. Brown continues to apply pressure to Rob until he admits that Carker and Edith are to meet up at Dijon, all of which Dombey hears, also.

After Rob falls asleep, Dombey pays Mrs. Brown and hurries away, his paleness and hurried tread indicating “that the least delay was an insupportable restraint upon him, and how he was burning to be active and away” (737). The women speculate that “he’s a madman, in his wounded pride” and could possibly commit murder (737). Mr. Dombey has indeed become obsessed with the idea of revenge. It became “the object into which his whole intellectual existence resolved itself. All the stubbornness and implacability of his nature, all its hard impenetrable quality, all its gloom and moroseness, all its exaggerated sense of personal importance, all its jealous disposition to resent the least flaw in its ample recognition of his importance by others, set this way like many streams united into one, and bore him on upon their tide . . . A wild beast would have been easier turned or soothed than the grave gentleman without a wrinkle in his starched cravat” (739). So emotion has finally broken through the icy barriers around Dombey’s heart, but of course, it is a negative emotion. Did we really expect anything different?

John Carker, the older brother of the Manager, has been fired from Dombey and Son since Dombey can no longer endure having a person of that name around him. John is not surprised or resentful of this, having seen it coming. Mr. Dombey has given him a generous severance, and John is appreciative of it, since it wasn’t required. Harriet finally tells John of the mysterious gentleman who visited her and pledged friendship to them both, but John is unable to guess who it could possibly be. The gentleman shows up and it is Mr. Morfin from Dombey and Son. How many of you guessed that correctly? Mr. Morfin points out how humans are, unfortunately, ruled by habit, which “confirms some of us, who are capable of better things, in Lucifer’s own pride and stubbornness–that confirms and deepens others of us in villainy–more of us in indifference–that hardens us from day to day, according to the temper of our clay, like images, and leaves us as susceptible as images to new impressions and convictions” (745). He confesses that it also blinds him to the true situation between the brothers, but his eyes are opened when he overhears a conversation between them through the thin walls of his office. After overhearing the conversation in which the brothers mention Harriet and her place in their lives, Mr. Morfin decides to meet her for himself.

Mr. Morfin reveals that he didn’t want to approach John Carker until he could actually do something concrete to help his situation, and he also hoped that possibly the brothers would reconcile. He felt that his involvement might interfere with that process, so he kept out of the picture. He promises to talk more with them later, but before he leaves, he reassures Harriet that James Carker did not embezzle from Dombey and Son. He admits that James has left the company weakened, but not in danger . . . unless “the head of the House, unable to bring his mind to the reduction of its enterprises, and positively refusing to believe that it is, or can be, in any position but the position in which he has always represented it to himself, should urge it beyond its strength. Then it would totter” (749). Does that seem likely? Would anyone we know possibly do that? Hmmmm.

The next day, John goes out to check on an employment prospect provided by their new friend and Harriet is left alone in the house. It is almost dark when suddenly a pale face appears at the window and rattling at the glass, demands to be let in. Harriet, recognizing Alice and remembering their last encounter, is terrified for a moment, but then the urgency of Alice’s requests moves her and she lets her in. Alice proceeds to share her backstory with Harriet.

She tells Harriet how her mother, Good Mrs. Brown, had always neglected her, but when she realizes that Alice’s beauty is a commodity worth much money, she suddenly becomes attached to her and begins to plan how to turn it to profit for herself. In a move that once again links their maternal relationship to that of Edith and her mother, Alice observes, “No great lady ever thought that of a daughter yet, I’m sure, or acted as if she did–it’s never done, we all know–and that shows that the only instances of mothers bringing up their daughters wrong, and evil coming of it, are among such miserable folks as us” (752). Do you think that Alice believes this, or is she being facetious? Is the lower class unaware that despite the gulf of privilege that divides them, those in the upper class often experience some of the same problems?

She goes on to disclose that instead of a wretched marriage, she “was made a short-lived toy, and flung aside more cruelly and carelessly than even such things are” and that it was James Carker who had treated her thus (752). After being used and abandoned by him, she “was sunk in wretchedness and ruin” and became “concerned in a robbery” (752). Arrested and sent to trial, she was alone and penniless but determined not to ask her former lover for help. Her mother, without Alice’s knowledge, did so, but to no avail. James refused to lift a finger to help her or to send her a penny, well-satisfied that she should be sent abroad and not around to trouble him further.

Alice goes on to confess that she, now knowing Carker’s location and situation, had helped to reveal his whereabouts to a man looking to destroy him. She admits that she now regrets this and despite what he has done to her, she cannot have his blood on her hands. She advises Harriet to write to him at once and warn him to get away, to put time and distance between himself and Dombey. And then she is gone.