The Readers Review: Literature from 1714 to 1910 discussion

This topic is about

Mansfield Park

2022/23 Group Reads - Archive

>

Mansfield Park, week 4: June 11-17: Volume 2, Chapters 7-13

um ... little detail: Fanny did not dance with William; siblings did not usually dance together - Fanny and William did so when they were much younger, and William says he would do so at a public assembly in Northampton - incognito!

um ... little detail: Fanny did not dance with William; siblings did not usually dance together - Fanny and William did so when they were much younger, and William says he would do so at a public assembly in Northampton - incognito! I’d dance with you if you would, for nobody would know who I was here

But not at the private ball in Mansfield Park, where they are both known. Remember Emma, who feels she has to remark explicitly that she and Knightley are not really brother and sister (Knightley's brother is married to Emma's sister) and therefore there is nothing objectionable about their dancing together.

But real siblings - no. I read somewhere that dancing was too much seen in the light of courtship and 'mating behaviour' to be innocuous for siblings.

Mary instantly approves of the match, both because she does like Fanny

Mary instantly approves of the match, both because she does like Fanny Mary spends time with Fanny because she likes her. Fanny does not approve of Mary but spends time with her anyway. I think this says something much more positive about Mary than Fanny. And, yes, I know this will be an unpopular opinion. Mary wants a friendship while Fanny does not. She is continuing to judge Mary and I continue to maintain it is not Fanny's job to judge. It is her choice to select her friends but if she does not approve of Mary then she should not pretend to care about her.

Fanny isn't taken in for one minute by Henry but she is too nice and polite to tell him to get lost. Well, she can't as she has no power in the household. At least she doesn't seriously take on any project to improve him. Again because she sees everybody clearly all the time. She's a bit like Cassandra of myth, if Cassandra wasn't even allowed to speak her correct predictions.

The idea of having a ball for Fanny when she really doesn't enjoy the fuss reminded me of recent stories where employees were uncomfortable with enforced birthday celebrations and other jollities at work. Once again Fanny is being used to make other people feel good about themselves.

The idea of having a ball for Fanny when she really doesn't enjoy the fuss reminded me of recent stories where employees were uncomfortable with enforced birthday celebrations and other jollities at work. Once again Fanny is being used to make other people feel good about themselves.

Jan wrote: "Mary wants a friendship while Fanny does not..."

Jan wrote: "Mary wants a friendship while Fanny does not..."But what kind of friendship? - Friendship as Mary undersatnds it, and only as far as it does not interfere with her abetting her adored brother'. (I wonder how active Mary's role was in the Maria affair). Fanny has her suspicions regarding the necklace scheme:

... for Miss Crawford, complaisant as a sister, was careless as a woman and a friend.

I like the expression 'as a woman and a friend'. It seems to point to an implicit code of conduct among women which requires them to put gender solidarity before family and marital loyalty - which would have been an important defense of women in a patriarchal world. And Mary does not abide by this code.

Jan wrote: "She is continuing to judge Mary and I continue to maintain it is not Fanny's job to judge."

The necklace affair shows that Fanny's judging is not a luxury of feeling morally superior - Mary's behaviour concerns her and puts her in a grey zone of 'proper conduct'. Fanny cannot rely on Mary's solidarity , and therefore has to judge at any step whether she herself is well within the narrow and complicated boundaries of a young woman's acceptable behaviour.

Then Fanny is insincere. She does not like Mary but pretends to do so. I think it is more than mere politeness. Fanny is an odd duck. She could just decline Mary's overtures and stand by her principals. Or she could accept Mary for who she is and stop judging her. If you haf a teenage daughter now with the same friendship issue, what would you tell her?

Then Fanny is insincere. She does not like Mary but pretends to do so. I think it is more than mere politeness. Fanny is an odd duck. She could just decline Mary's overtures and stand by her principals. Or she could accept Mary for who she is and stop judging her. If you haf a teenage daughter now with the same friendship issue, what would you tell her?

I'm the last one to defend Fanny but I don't think she is pretending to like Mary. She is being polite, and she has learned the hard way that there is no benefit to expressing her true opinions to most people. Teenage girls today have so much more independence and freedom and therefore more choices of how to react.

If Fanny started speaking up, it would probably only make people angry at her, even though (or especially because ) they know she is right. They don't want a spoilsport. Someone in my family went through a very religious period years ago and her sister said, "It's like having a nun in the house". Fanny is a bit like that just by being who she is and living within her own virtues.

If Fanny started speaking up, it would probably only make people angry at her, even though (or especially because ) they know she is right. They don't want a spoilsport. Someone in my family went through a very religious period years ago and her sister said, "It's like having a nun in the house". Fanny is a bit like that just by being who she is and living within her own virtues.

My point is, Mary likes Fanny. What is Fanny's deal? Is she checking out the competion? Is she just being Fanny? Why does everyone assume Fanny is a good person because she will hang out with Mary but Mary is the one with ulterior motives? They can both have nuances. Fanny does not have to be a perfect paragon and Mary all bad.

My point is, Mary likes Fanny. What is Fanny's deal? Is she checking out the competion? Is she just being Fanny? Why does everyone assume Fanny is a good person because she will hang out with Mary but Mary is the one with ulterior motives? They can both have nuances. Fanny does not have to be a perfect paragon and Mary all bad. Is she were my daughter, I would tell her to either stop judging Mary of stop hanging out with her.

Robin P wrote: "The idea of having a ball for Fanny when she really doesn't enjoy the fuss reminded me of recent stories where employees were uncomfortable with enforced birthday celebrations and other jollities at work. Once again Fanny is being used to make other people feel good about themselves.."

Robin P wrote: "The idea of having a ball for Fanny when she really doesn't enjoy the fuss reminded me of recent stories where employees were uncomfortable with enforced birthday celebrations and other jollities at work. Once again Fanny is being used to make other people feel good about themselves.."This made me laugh. At my workplace, we're all judging a woman who won't tell us when her birthday is, as there's always a round of chocolates or cookies on birthdays. Maybe she's Fanny Price in disguise...

I do find Mary comes across a little badly in the necklace interlude, but am also enormously frustrated by Fanny's dislike of Mary. She justifies with according to Mary's failings (things she never thinks directly about Maria or Julia), but it becomes clear that it's simply because she is consumed by jealousy.

I do find Mary comes across a little badly in the necklace interlude, but am also enormously frustrated by Fanny's dislike of Mary. She justifies with according to Mary's failings (things she never thinks directly about Maria or Julia), but it becomes clear that it's simply because she is consumed by jealousy.

Emily wrote: "Robin P wrote: "The idea of having a ball for Fanny when she really doesn't enjoy the fuss reminded me of recent stories where employees were uncomfortable with enforced birthday celebrations and o..."

You're right that it seems silly to resist fun and most of us love any excuse for a celebration to break up the monotony of work. That's one of the things people miss when everyone is remote. But with all the emphasis on diversity and inclusion, it's only fair to recognize that some people detest any attention. (I am the opposite, there isn't enough attention in the world for me!)

For Fanny, she was from a big family originally, where individual children probably were barely acknowledged. Then she was put in the Cinderella role and reminded of it constantly. Mostly when she has gotten attention it was negative, except for Edmund. Keeping a low profile is a survival skill for her. And I assume nobody made an effort to teach her all the graces for a ball. I don't remember if the book says anything about this, but I suppose she would learn dancing only because other young people were doing it and they needed an even number.

You're right that it seems silly to resist fun and most of us love any excuse for a celebration to break up the monotony of work. That's one of the things people miss when everyone is remote. But with all the emphasis on diversity and inclusion, it's only fair to recognize that some people detest any attention. (I am the opposite, there isn't enough attention in the world for me!)

For Fanny, she was from a big family originally, where individual children probably were barely acknowledged. Then she was put in the Cinderella role and reminded of it constantly. Mostly when she has gotten attention it was negative, except for Edmund. Keeping a low profile is a survival skill for her. And I assume nobody made an effort to teach her all the graces for a ball. I don't remember if the book says anything about this, but I suppose she would learn dancing only because other young people were doing it and they needed an even number.

Jan wrote: "Mary spends time with Fanny because she likes her. Fanny does not approve of Mary but spends time with her anyway. I think this says something much more positive about Mary than Fanny. ... It is her choice to select her friends but if she does not approve of Mary then she should not pretend to care about her.

Jan wrote: "Mary spends time with Fanny because she likes her. Fanny does not approve of Mary but spends time with her anyway. I think this says something much more positive about Mary than Fanny. ... It is her choice to select her friends but if she does not approve of Mary then she should not pretend to care about her.When did Fanny ever get the chance to choose who she spends time with? Her role is always to be at the beck and call of her social superiors, to keep them company and entertain them when they want her to. Mary isn't interested in Fanny when better company and other amusements are available, and is happy to leave her at home or on her own when they are. It's only when winter sets in and the Bertram girls are away and she's bored that she calls on Fanny for company.

She is mildly fond of her, or rather is sorry for her, comforting her when everybody's having a go at her during the casting of the play, and she doesn't want Henry to hurt her too badly with his nasty little game - but doesn't care enough to tell Henry he's out of order, or to refuse to collude in the necklace trick. A true friend would have warned Fanny what he was up to, but to Mary she's just a source of entertainment.

Nor does Fanny 'pretend to care' about Mary. She is obliging and courteous towards her, as she is towards her aunts and to Mrs Grant, but although Mary moves onto first-name terms as soon as she regards her as a future sister-in-law, to Fanny she is never more than 'Miss Crawford' - underlining the difference in their social status. It's the social superior who decides the level of intimacy, and you notice Miss Crawford never invites Fanny to call her 'Mary'.

Robin P wrote: "The idea of having a ball for Fanny when she really doesn't enjoy the fuss reminded me of recent stories where employees were uncomfortable with enforced birthday celebrations and other jollities at work. Once again Fanny is being used to make other people feel good about themselves..."

Robin P wrote: "The idea of having a ball for Fanny when she really doesn't enjoy the fuss reminded me of recent stories where employees were uncomfortable with enforced birthday celebrations and other jollities at work. Once again Fanny is being used to make other people feel good about themselves..."I don't think we can say Fanny didn't enjoy the ball. She's uncomfortable with being the centre of attention (especially since she's spent half her life being told she's not worthy of it and not to put herself forward) but she enjoys dancing and her new status as de facto daughter of the house ("This was treating her like her cousins!") rather than lowly poor relation. And having young men actively wanting to dance with her, rather than just being used by Tom as an excuse to avoid cards!

She had to be ordered to go to bed at 3am when, even though she was tired, she would have clearly liked to have stayed.

Robin P wrote: "Emily wrote: "Robin P wrote: "The idea of having a ball for Fanny when she really doesn't enjoy the fuss reminded me of recent stories where employees were uncomfortable with enforced birthday cele..."

Robin P wrote: "Emily wrote: "Robin P wrote: "The idea of having a ball for Fanny when she really doesn't enjoy the fuss reminded me of recent stories where employees were uncomfortable with enforced birthday cele..."We get birthday cookies or donuts at work but with no fuss. They are just on the table in the break room with a note. I would definitely not want people singing to me and making me the center of attention in a group.

I agree with Jenny’s take on Fanny’s intimacy with Mary Crawford—that Mary is bored and any company is better than none, and Fanny, with her habits of obedience and rating others’ claims above her own, feels obliged by civility to go along. Although Mary can see some of Fanny’s good qualities, she routinely misunderstands her, attributing her own motives and subtleties to Fanny when Fanny didn’t intend anything of the kind. The scene where Mary offers Fanny a necklace is a case in point: if she truly understood Fanny, she would yield and drop the subject when Fanny shows herself so uncomfortable about it; instead, she manipulates Fanny’s feelings to get her way. Fanny is truly embarrassed at the idea that Henry gave the necklace to his sister, but Mary believes she is simply “protesting too much.” The literature of the period (including Austen’s own writing starting with “Catharine; or, The Bower,” which she wrote in her teens), is rife with worldly characters who talk their way around less sophisticated heroines to get their own way. Mary’s note to Fanny after Henry has proposed is another effort to maneuver Fanny.

I agree with Jenny’s take on Fanny’s intimacy with Mary Crawford—that Mary is bored and any company is better than none, and Fanny, with her habits of obedience and rating others’ claims above her own, feels obliged by civility to go along. Although Mary can see some of Fanny’s good qualities, she routinely misunderstands her, attributing her own motives and subtleties to Fanny when Fanny didn’t intend anything of the kind. The scene where Mary offers Fanny a necklace is a case in point: if she truly understood Fanny, she would yield and drop the subject when Fanny shows herself so uncomfortable about it; instead, she manipulates Fanny’s feelings to get her way. Fanny is truly embarrassed at the idea that Henry gave the necklace to his sister, but Mary believes she is simply “protesting too much.” The literature of the period (including Austen’s own writing starting with “Catharine; or, The Bower,” which she wrote in her teens), is rife with worldly characters who talk their way around less sophisticated heroines to get their own way. Mary’s note to Fanny after Henry has proposed is another effort to maneuver Fanny.In general, the Crawfords are forever putting Fanny in situations that make her uncomfortable while trapping her in a false position. Securing William’s promotion is a lulu.

In this section we see more of Fanny’s jealousy, which poses a delicate moral problem for her. I think she genuinely believes that Mary would be a bad wife for Edmund, always dissatisfied and pressuring him to neglect his calling and spend more money than he can afford, but of course she also wants him to love her romantically without ever believing she is entitled to such love. In vol. 2, chap. 9, it says, “It was her intention, as she felt it to be her duty, to try to overcome all that was excessive, all that bordered on selfishness in her affection for Edmund.” The part that is excessive and borders on selfishness is her desire to be loved by him, but that’s only a portion of her feeling; the part she feels justified is the part that wishes him to fulfill his calling without being burdened with a wife who will undermine him at every turn. At the ball (chapter 10) she sees Mary ridiculing him for his determination to become not juste a clergyman, but a clergyman attentive to his duties. (Mary herself has second thoughts afterward, thinking maybe she spoke too harshly.) Fanny is happy about the resultant rift, I think not for her own sake but because she believes Edmund would be making a mistake he would later regret in marrying Mary. She celebrates his short-term pain in the belief that he will ultimately be better off.

In chapter 11, Mary all but confesses her love for Edmund and jealousy of the Misses Owen. Speaking to Fanny, she says, “But you must give my compliments to him. Yes—I think it must be compliments. Is not there a something wanted, Miss Price, in our language—a something between compliments and—and love—to suit the sort of friendly acquaintance we have had together?” In the manners of the day, this would have been seen as very forward, and it also echoes the behavior of Amelia in Lovers’ Vows, the role Mary was to have played. Later in the scene Mary makes it clear that her mind is focused on matrimony.

I think Mary is not an appropriate wife for Edmond but not because I think she is a bad person. They are not compatible because she does not like church or the country.

I think Mary is not an appropriate wife for Edmond but not because I think she is a bad person. They are not compatible because she does not like church or the country.

Jan wrote: "I think Mary is not an appropriate wife for Edmond but not because I think she is a bad person. They are not compatible because she does not like church or the country."

Yes, she would quickly become bored and whiny, and would flirt with other men.

Yes, she would quickly become bored and whiny, and would flirt with other men.

I think we can all agree that Mary would be a bad wife for Edmund. And I have sympathy for Fanny's jealousy.

I think we can all agree that Mary would be a bad wife for Edmund. And I have sympathy for Fanny's jealousy. But I suppose there's a tension here between what ages well in all Austen novels (pacing, written flair, satire, psychological insight) and what I think ages badly in this one (perhaps alone among her novels).

Abigail describes Mary as worldly and I think that's right. I think what is difficult for the modern reader is seeing this as a bad thing. Experienced, sophisticated, aware of how the world works. None of these would be considered bad things any more. And Mary is not cruel. Agreed, she doesn't protect Fanny from her brother, but then according to her own worldly state, Fanny could probably use a bit of modernising. She does protect Fanny from other uncomfortable situations.

And while she and Edmund aren't suited, it seems to be a case of opposites attracting. In fact, Mary shows she isn't mercenary by continuing to prefer Edmund although his brother is the heir, and by encouraging her brother to marry Fanny despite its being a low match (in part because this will entangle her further with Edmund, but basically, she's prepared for the whole family to take a step down in the world and live happily in the countryside. We may suspect that none of them would be that happy, but nonetheless this seems to be her motivation).

The Mary/Fanny dynamic reminds me a little of Becky/Amelia in Vanity Fair, except that Mary is nowhere near and machinating or backhanded as Becky.

Emily wrote: "I think what is difficult for the modern reader is seeing this as a bad thing. Experienced, sophisticated, aware of how the world works. None of these would be considered bad things any more. "

Emily wrote: "I think what is difficult for the modern reader is seeing this as a bad thing. Experienced, sophisticated, aware of how the world works. None of these would be considered bad things any more. "Many of Austen's readers in her time would have seen Mary in the same way. For Austen, Mary is the product not only of her upbringing, but also of London society: she is in line with the (new) 'urban' morals of the time, as contrasted with the (old) 'rural' morals of Sir Thomas, Edmund, and Fanny.

Maybe MP is Austen's most 'moralist' novel? She holds up the mirror to the worldly society and confronts it with values that begin to look old-fashioned even in her own time.

Fanny’s jealousy is a part of her I like- a.feeling I can identify with - even if she never expresses it.

sabagrey wrote: "She holds up the mirror to the worldly society and confronts it with values that begin to look old-fashioned even in her own time."

sabagrey wrote: "She holds up the mirror to the worldly society and confronts it with values that begin to look old-fashioned even in her own time."Agreed.

Robin P wrote: "Fanny’s jealousy is a part of her I like- a.feeling I can identify with - even if she never expresses it."

Robin P wrote: "Fanny’s jealousy is a part of her I like- a.feeling I can identify with - even if she never expresses it."Yes - I admire her for acknowledging it in herself, trying to overcome it and not acting on it. Even if such a thing were not totally out of order for a lady of the time (though that didn't stop Lady Caroline Lamb!), we know she would never manipulate Edmund or try to make him feel under an obligation to return her love.

That's her moral dilemma - she must wonder to herself how much her concern about Edmund marrying Mary is really due to fear for Edmund's happiness and how much of it her own jealousy. But I'm pretty sure if it were one of the Miss Owens she'd be gritting her teeth and trying to be happy for him.

Emily wrote: "In fact, Mary shows she isn't mercenary by continuing to prefer Edmund although his brother is the heir...

Emily wrote: "In fact, Mary shows she isn't mercenary by continuing to prefer Edmund although his brother is the heir...She continues to prefer him, but she's by no means happy about marrying him ... until (view spoiler).

That's her dilemma - yes, I'm in love with him, but he's a younger son and a mere parson and I could get someone richer, smarter and of higher status.

I do not think Jane Austen wants us to see these characters in black and white. People are complicated and nuanced and otherwise bad people can do nice things without ulterior motives. Fanny may see Henry and Mary in a negative light but we are required to see every thing they do as bad. And if it is nice, they are nice for all the wrong reasons. Fanny sees no shades of grey but we can.

I do not think Jane Austen wants us to see these characters in black and white. People are complicated and nuanced and otherwise bad people can do nice things without ulterior motives. Fanny may see Henry and Mary in a negative light but we are required to see every thing they do as bad. And if it is nice, they are nice for all the wrong reasons. Fanny sees no shades of grey but we can.

I don’t know that the values expressed in the book are old-fashioned for Austen’s time so much as they are class-based. After all, a lot of the moral assumptions behind this book prevailed throughout the Victorian era and only started to fade in the 1890s. The behavior of the Crawfords was perhaps the norm in aristocratic circles but the rural gentry and middle classes were more straitlaced. I think the book plays more on dichotomies between the genuine/substantive and the fake/surface in human relations. Fanny has to be so straightforward in her worldview (and Edmund so humorless) because they are set in opposition to the maneuvering and deceptiveness of the Crawfords and Yates. Maria, Julia, and Tom are all seduced by the pleasures of that more sophisticated world, but their behavior threatens to render the world of Mansfield Park nonviable. That’s why the idea of a play (a deceptive depiction of reality) is key, and why it needs to seem so perilous an undertaking.

I don’t know that the values expressed in the book are old-fashioned for Austen’s time so much as they are class-based. After all, a lot of the moral assumptions behind this book prevailed throughout the Victorian era and only started to fade in the 1890s. The behavior of the Crawfords was perhaps the norm in aristocratic circles but the rural gentry and middle classes were more straitlaced. I think the book plays more on dichotomies between the genuine/substantive and the fake/surface in human relations. Fanny has to be so straightforward in her worldview (and Edmund so humorless) because they are set in opposition to the maneuvering and deceptiveness of the Crawfords and Yates. Maria, Julia, and Tom are all seduced by the pleasures of that more sophisticated world, but their behavior threatens to render the world of Mansfield Park nonviable. That’s why the idea of a play (a deceptive depiction of reality) is key, and why it needs to seem so perilous an undertaking.I see the following passage in the previous section as central to the thesis: on hearing William’s tales of life at sea, Henry Crawford

longed to have been at sea, and seen and done and suffered as much. His heart was warmed, his fancy fired, and he felt the highest respect for a lad who, before he was twenty, had gone through such bodily hardships, and given such proofs of mind. The glory of heroism, of usefulness, of exertion, of endurance, made his own habits of selfish indulgence appear in shameful contrast; and he wished he had been a William Price, distinguishing himself and working his way to fortune and consequence with so much self-respect and happy ardour, instead of what he was!

The wish was rather eager than lasting. He was roused from the reverie of retrospection and regret produced by it, by some inquiry from Edmund as to his plans for the next day’s hunting; and he found it was as well to be a man of fortune at once with horses and grooms at his command.

The admiration for striving and achievement was largely alien to the aristocracy but was central to the worldview of the middle class. Austen was more middle-class than otherwise herself and had brothers in the navy, and I feel this book perhaps more than any of the others (except Persuasion?) celebrates those values.

I am not saying Jane Austen thought audultry was okay or questioning the values of the time. I am just saying people can give Mary and Henry credit were credit is due and not ascribe any act of kindness on their part to an ulterior motive. They are not all bad.

I am not saying Jane Austen thought audultry was okay or questioning the values of the time. I am just saying people can give Mary and Henry credit were credit is due and not ascribe any act of kindness on their part to an ulterior motive. They are not all bad. JA may not have wanted us to see Fanny as perfect, either. She does not deserve the evil aunt Norris. Her abuse explains much of Fanny's timidity. Jane may be telling us this is what happens when you treat a person like this. She has principles but does not know how to engage in the world and that is a flaw in itself. We do not know a lot about what Jane thought because so little of her personal writing beyond her novels survives.

There's one quite breathtaking example of different moral values across the centuries in the case of William's promotion. It is shown as admirable in Sir Thomas that he does what he can to use his wealth and influence to secure advantages for his more disadvantaged connections, and the only reason he didn't get William's promotion himself was that he didn't have the right influence in the right place.

There's one quite breathtaking example of different moral values across the centuries in the case of William's promotion. It is shown as admirable in Sir Thomas that he does what he can to use his wealth and influence to secure advantages for his more disadvantaged connections, and the only reason he didn't get William's promotion himself was that he didn't have the right influence in the right place.That William's promotion depends on knowing the right people who will pull strings for him (and that his father's lack of it was partly down to not knowing them) is taken absolutely for granted; yet today if an MP were caught trying to wangle promotions in the armed forces for his wife's nephews there would the most colossal scandal, he would be expected to resign and so would his connections who did the wangling for him. It would be regarded as corruption, plain and simple.

In fact, even at the time that's what happened when it was discovered that men were bribing the Duke of York's mistress to get them military promotions via pillow talk, but it wasn't the doing of favours for mates that was the problem - it was that money changed hands and it was a mistress, rather than having, say, an uncle who belonged to the same club as the Duke's cousin.

So does the fact that Sir Thomas is willing to pull strings in this way, and that William is willing to take advantage of it, make them bad people?

Jenny wrote: "There's one quite breathtaking example of different moral values across the centuries in the case of William's promotion. It is shown as admirable in Sir Thomas that he does what he can to use his ..."

Jenny wrote: "There's one quite breathtaking example of different moral values across the centuries in the case of William's promotion. It is shown as admirable in Sir Thomas that he does what he can to use his ..."Not to mention living off the profits of slavery and imperialism! Yes, we have to swallow a lot in the value system that has changed.

Abigail wrote: "Jenny wrote: "There's one quite breathtaking example of different moral values across the centuries in the case of William's promotion. It is shown as admirable in Sir Thomas that he does what he c..."

Abigail wrote: "Jenny wrote: "There's one quite breathtaking example of different moral values across the centuries in the case of William's promotion. It is shown as admirable in Sir Thomas that he does what he c..."Well said, Abigail

As far as the patronage system, it is maybe a minority view that nobody should get advantages. The US gets angry when they give money to nations in need and the people in charge give contracts, jobs, etc. to their relatives. We see that as corruption. But in the local culture, it is corrupt to have access to power and money and not share it with your friends and family.

It seems like in Austen's time, the fact that someone of high rank spoke up for you was more important than your personal qualities.

I love Henry's brief fantasy of being a sea hero. He wants to "have done it", not actually do it. Of course, he wouldn't last a week at sea or at most actual jobs! I think that's very psychologically astute and is the same as people exaggerating or lying about their exploits to get admiration.

It seems like in Austen's time, the fact that someone of high rank spoke up for you was more important than your personal qualities.

I love Henry's brief fantasy of being a sea hero. He wants to "have done it", not actually do it. Of course, he wouldn't last a week at sea or at most actual jobs! I think that's very psychologically astute and is the same as people exaggerating or lying about their exploits to get admiration.

Jenny wrote: "There's one quite breathtaking example of different moral values across the centuries in the case of William's promotion.."

Jenny wrote: "There's one quite breathtaking example of different moral values across the centuries in the case of William's promotion.."Ahem. You really think so? - I'd rather say it is timeless. Maybe no longer for the lower career levels, but as you get higher ... but perhaps you live in a country where all is clean and transparent and impartial and whatnot (where is that country, please?) - where I live, the bad old system of connections is alive and kicking.

For England in Jane Austen's time, you had the 'moral' choice between connections used to make an officer in the navy - and the sale of ranks in the army for money. ... I sometimes imagine the staggering accumulation of incompetence that ensued in both cases, including the unnecessary loss of thousands of lives.

sabagrey wrote: "Jenny wrote: "There's one quite breathtaking example of different moral values across the centuries in the case of William's promotion.."

sabagrey wrote: "Jenny wrote: "There's one quite breathtaking example of different moral values across the centuries in the case of William's promotion.."Ahem. You really think so? - I'd rather say it is timeless..."

Yes, neither system was based on merit.

sabagrey wrote: "Jenny wrote: "There's one quite breathtaking example of different moral values across the centuries in the case of William's promotion.."

sabagrey wrote: "Jenny wrote: "There's one quite breathtaking example of different moral values across the centuries in the case of William's promotion.."Ahem. You really think so? - I'd rather say it is timeless..."

Oh yes, it still happens, and indeed a recent Prime Minister of our own has been an egregious example of it. But it's not supposed to happen, and when people are caught doing it it's considered scandalous and a resigning matter. In Austen's world, it's the normal way of doing things and even considered admirable, a duty.

But my question was, how far is it fair of us to judge the characters for behaviour that they considered good but we consider bad? Jane Austen clearly wants us to think Sir Thomas good for trying to pull strings for William. There's no evidence that she wanted us to think him bad for profiting from slavery and imperialism. Where do we draw the line?

Owning humans is bad whether Jane Austen wanted us to think so or not. Many people thought so at the time. Not a 21st century idea. The US Founding Fathers fought over the issue. Owning people is not the same level of morality as calling in favors.

Owning humans is bad whether Jane Austen wanted us to think so or not. Many people thought so at the time. Not a 21st century idea. The US Founding Fathers fought over the issue. Owning people is not the same level of morality as calling in favors.I will give credit to Sir Thomas and all others in this novel for trying to help William but I expect Sabagray has a point with it and the purchase of commission not contributing to a quality armed forces. It may have also had something to do with the south's ultimate failure in the US Civil War. The officers were the sons of the wealthy because they had no military to draw from where the Union army had a system in place with West Point for education and some chance for deserved promotions amongst a established army.

Another example of merit not winning out - The fact that church "livings" were given out by the local gentry also didn't contribute to the most pious or responsible or caring people becoming local clergymen. From some of the books by Trollope and others, it was common for the person with the living to farm out his duties to a curate who was barely paid, while the vicar got to live in a big house and collect the salary. Even if the vicar did the work, such as Mr. Collins, the parish was stuck with him until he died, no possibility of removing him (unless there was some huge scandal.)

Digression to cover points of comparison.

Digression to cover points of comparison.Actually, the Confederacy had an excellent officer corps, also drawn from West Point graduates, and former students of VMI (the Virginia Military Institute), where Stonewall Jackson was an instructor.

One of the Union's advantages was that Confederate President Jefferson Davis, another West Pointer, did not trust many of his generals (including Lee), and often interposed his own ideas of strategy. Or, as Grant later put it, he 'exercised his military genius, always to the benefit of the United States,' or words to that effect.

A problem with both armies was that the majority of the manpower came from Volunteer regiments raised by the several states, whose governors treated commissions as political plums: and some Union regiments actually elected their own officers (I don't know about the Confederacy on this). It took years to get that sorted out, although the high rate of officer casualties (including generals) suggests that these men were at least brave.

(One the most notable of the West Point generals, Albert Sidney Johnston, Davis' favorite officer, got himself killed by riding ahead of his the firing line of his own troops, exposing himself to 'friendly fire.')

The British army's system of purchased commissions went back to nervousness about a standing army, after Cromwell. Making all officers, in effect, post bond for their good behavior was thought to be a check on revolutionary ambitions. It was not the most efficient system for producing an officer corps, but the real problems with it surfaced during the Crimean War (1853-56).

By that time the only "veteran" generals left had been aides-de-camp to the Duke of Wellington in 1815, and some out of touch with even the new words of command in a restructured army. (Veteran non-commissioned officers were sometimes needed to translate.)

There were some experienced officers, but they had fought in India, and were considered hopelessly middle class, since they couldn't afford to take leave and stay in England on half-pay, like a gentleman. A few senior officers were smart enough to take them on their staff, but their experience in combat, logistics, etc., was mostly ignored.

There were CSA generals such as Lee, but there were also plenty of the Ashley Wilkes sort that joined up thinking it would be a grand and noble adventure over rather quickly. These sons of planters who came is as officers, the lieutenants, simply because they were rich was who I was referring to, not the elite corp.

There were CSA generals such as Lee, but there were also plenty of the Ashley Wilkes sort that joined up thinking it would be a grand and noble adventure over rather quickly. These sons of planters who came is as officers, the lieutenants, simply because they were rich was who I was referring to, not the elite corp.

Jan wrote: "Owning humans is bad whether Jane Austen wanted us to think so or not. Many people thought so at the time. Not a 21st century idea. The US Founding Fathers fought over the issue. Owning people is n..."

Jan wrote: "Owning humans is bad whether Jane Austen wanted us to think so or not. Many people thought so at the time. Not a 21st century idea. The US Founding Fathers fought over the issue. Owning people is n..."Not a C21st idea, but only in the last 2 or 3 centuries, compared to the millennia before that when nobody thought twice about it. In the ancient world even slaves didn't think slavery was wrong, however much they may have wished they weren't on the wrong end of it; and generally when they were freed and had the means, they would own slaves themselves. Was everybody above a certain level of income a 'bad person' for several thousand years?

And it does matter whether JA wanted us to think of a character of hers as bad or not: because these are not real people. They have no existence outside the words Austen used to create them and those words are all we have to define those characters. She uses words to describe them and their actions, and chooses to give them actions that demonstrate their character as she conceives them.

Therefore whether she believed an action to be bad or not is the only criterion for judging whether a character is meant to be a bad person or not. And whether they are meant to be bad is the only criterion for saying whether they are - because they have no existence outside Austen's intentions for them.

She wants us to think Sir Thomas a good person for trying to pull strings on behalf of his nephew, even though we would think otherwise. I don't see any evidence that she intends his profiting from imperialism and slavery to indicate that he was a bad person.

Further digressions.

Further digressions.The professional skills of the British Army’s engineers and artillerists should be taken into account.

The Union army was full of officers who got state commissions because they had political connections or were socially prominent, often meaning wealthy. They ranged in rank from second lieutenant to full colonel. The tiny regular army in any case couldn’t provide enough trained officers for the huge armies that emerged, even without the loss of personnel to the Confederacy, and including retired officers returning to service.

Some those politically connected Union officers did have valuable experience in specialized occupations, not covered at West Point, including making roads and running railroads, while the Confederate officer pool generally didn’t.

Jenny wrote: "Jan wrote: "Owning humans is bad whether Jane Austen wanted us to think so or not. Many people thought so at the time. Not a 21st century idea. The US Founding Fathers fought over the issue. Owning..."

Jenny wrote: "Jan wrote: "Owning humans is bad whether Jane Austen wanted us to think so or not. Many people thought so at the time. Not a 21st century idea. The US Founding Fathers fought over the issue. Owning..."I have no issue with Sir Thomas pulling strings for William and give credit where credit is due on that account. I said that before.

I disagree with you that we have to agree with the point of view of the author on his or her intent on every character in every book. Then why discuss them? If Jane Austen thinks this person is good they are good and if she thinks this is bad it is bad, case closed. That is why there are book clubs. To discuss books, not to say this is what the author meant so we must say it is so.

I am not even applying 21st century attitudes to the situation of Sir Thomas and slavery. The US Civil War was a 19th century war fought over slavery. Slavery was a fraught issue from the inception of the country to the until after reconstruction after the civil war.

Ian wrote: "Further digressions.

Ian wrote: "Further digressions.The professional skills of the British Army’s engineers and artillerists should be taken into account.

The Union army was full of officers who got state commissions because t..."

Ian, you seem interested in the US Civil War. Have you read Crucible of Command or Rebel Yell?

I know. Digression.

Fortunately, Jane Austen is much better at creating characters than simply giving us 'good persons' and 'bad persons'. If it were so, there would indeed be nothing to discuss. Instead, she created characters that are much more realistic, therefore complex, and therefore mixtures of strengths and weaknesses - and strengths that turn out weaknesses - and the other way round.

Fortunately, Jane Austen is much better at creating characters than simply giving us 'good persons' and 'bad persons'. If it were so, there would indeed be nothing to discuss. Instead, she created characters that are much more realistic, therefore complex, and therefore mixtures of strengths and weaknesses - and strengths that turn out weaknesses - and the other way round.

sabagrey wrote: "Fortunately, Jane Austen is much better at creating characters than simply giving us 'good persons' and 'bad persons'. If it were so, there would indeed be nothing to discuss. Instead, she created ..."

sabagrey wrote: "Fortunately, Jane Austen is much better at creating characters than simply giving us 'good persons' and 'bad persons'. If it were so, there would indeed be nothing to discuss. Instead, she created ..."They have nuances.

Crucible is somewhere on my wish lists. I read or re-read a lot on the Civil War a couple of years ago — it is a recurring interest since childhood.

Crucible is somewhere on my wish lists. I read or re-read a lot on the Civil War a couple of years ago — it is a recurring interest since childhood.I have also been reading a great deal about the Napoleonic Wars, particularly Wellington’s Peninsular campaigns (Spain and Portugal), but I don’t feel able to summarize broadly. I will say that some of the most efficient officers were gentry, rather than aristocracy. But that may have involved demographics, one group being much more numerous. There are a remarkable number of journals or memoirs, many in Kindle, but I haven’t read very many.

This is much more relevant to Jane Austen, and I could supply some basic bibliography for the curious. (Georgette Heyer’s The Spanish Bride is solidly based on memoirs from one regiment in the Light Division, and is a relatively painless way of absorbing information on how the infantry saw the war.)

I was wondering if it was good and not a Lost Cause promo. I asked since you seemed to have insight on that topic.

I was wondering if it was good and not a Lost Cause promo. I asked since you seemed to have insight on that topic.

While looking through memoirs from British officers of the Napoleonic Wars, I discovered one with a description of Antigua, and reflections on slavery, from just before Trafalgar. It also reminded me that Yellow Fever was also a major threat to those venturing to the West Indies. See the Kindle edition of “Captain of then95th (Rifles)…..,” by Jonathan Leach. The first chapter may be sufficient, although there are mentions of how commissions were bought, sold, and traded, so that officers jumped from one regiment to another in a way that now seems peculiar, in the following material.

While looking through memoirs from British officers of the Napoleonic Wars, I discovered one with a description of Antigua, and reflections on slavery, from just before Trafalgar. It also reminded me that Yellow Fever was also a major threat to those venturing to the West Indies. See the Kindle edition of “Captain of then95th (Rifles)…..,” by Jonathan Leach. The first chapter may be sufficient, although there are mentions of how commissions were bought, sold, and traded, so that officers jumped from one regiment to another in a way that now seems peculiar, in the following material.

This is one of my favourite parts of the book because it ends with Henry grovelling in front of Fanny. All his schemes and his sister’s collaborations to overwhelm Fanny end up biting the dust by her curt rejection. Not only that, she shows her anger in the way she thinks he is mocking her. She does well to contain those conflicting emotions of great joy for her brother and contempt for Henry’s proposal. In the end she reduces his proposal to something that she believes is ridiculous.

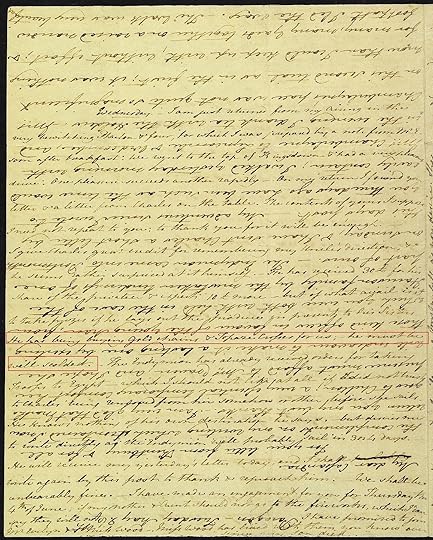

This is one of my favourite parts of the book because it ends with Henry grovelling in front of Fanny. All his schemes and his sister’s collaborations to overwhelm Fanny end up biting the dust by her curt rejection. Not only that, she shows her anger in the way she thinks he is mocking her. She does well to contain those conflicting emotions of great joy for her brother and contempt for Henry’s proposal. In the end she reduces his proposal to something that she believes is ridiculous.I must mention the symbolism of the cross and the chain. To begin with the episode shows just how close Fanny was to Jane Austen’s own heart. Jane and her sister were each sent a cross and chain by her younger brother Charles who was a naval officer.

’ Charles, an officer in the Royal Navy, bought the crosses with prize money he received from the capture of an enemy ship. In a letter to Cassandra, dated 26/27 May, 1801, Jane Austen writes with mock indignation (but obvious delight):

‘…of what avail is it to take prizes if he lays out the produce in presents to his Sisters. He has been buying Gold chains and Topaze (sic) Crosses for us; – he must be well scolded…I shall write again by this post to thank and reproach him. We shall be unbearably fine.’

Here is the extract from the actual letter……

……and here is one of the the crosses with a chain…

I believe that this reveals how important a heroine Fanny was to Jane Austen because she almost places Fanny in her own shoes and certainly into a similar situation in receiving the present of a cross.

I believe that the two chains have a distinct symbolism in the way they represent Henry/Mary and Edmund. The chunky, gaudy, over elaborate chain from Henry which Mary deliberately guided Fanny to choose represents the overblown debauchery and glittering falsehoods of Henry’s sentiments. (More about his ‘love’ later.) Edmund’s slender and simple but elegant chain reveals his honest sentiments as well as his understanding of Fanny’s own tastes. The fact that Henry’s chain won’t fit through the bail of the cross is symbolic of his selfish ‘love’ and the bloated ostentation of his sentiments. He could never be a trusted partner to anyone due to his overblown ego.

Fanny was so pleased to join Edmund’s chain with her brother’s cross, to create something very similar to the photo. A cross and chain that Jane Austen herself no doubt wore with such pride.

I don’t believe that Henry has fallen in love with Fanny. Instead, all his attempts to ingratiate himself with her and her subsequent indifference has led his flirtatious prank to become an all consuming infatuation. How infuriating it must have been to Henry to watch Fanny dote on her brother yet treat him, a supposedly much superior being, with respectful disregard.

I don’t believe that Henry has fallen in love with Fanny. Instead, all his attempts to ingratiate himself with her and her subsequent indifference has led his flirtatious prank to become an all consuming infatuation. How infuriating it must have been to Henry to watch Fanny dote on her brother yet treat him, a supposedly much superior being, with respectful disregard.For those who have read War and Peace, (I wonder if Tolstoy ever read Jane Austen?), I think there is a passing resemblance between the way Henry and Mary collaborate over Fanny and (view spoiler)

It seems that Edmund is finally realising that Mary may not be a suitable clergyman’s wife. She would certainly be closer in morals to Hélène Kuragin than Mrs. Grant. And I wonder if Henry really should be proposing to Fanny. Judging by his sister’s assessment of his past it is quite possible he ought to be married already, (á la Willoughby.)

As for William’s promotion, I agree with those who feel it is tainted with the canker of cronyism. I am quite sure that if Fanny had known what type of man the admiral really was she would not have approved of her brother being stained by his corruption. Favours like that are often called in at a later date by unscrupulous types like the admiral. Who knows what William might be asked to do to stay in the admiral’s good favour. Someone who could have a man hung almost as quickly as they could get him promoted.

Books mentioned in this topic

War and Peace (other topics)Emma (other topics)

To everyone’s surprise, the social life between the two houses continues to be pleasant and enjoyable, likely due to the enlivening presence of Henry Crawford and William Price, but probably also as Fanny becomes somewhat more engaged and included. A chance enquiry by William as to Fanny’s dancing leads Sir Thomas to propose a ball in Fanny’s honour as she has never been to one. It appears that this was never done for the Misses Bertram, so this is quite an honour for Fanny.

Henry Crawford begins his unkind scheme of trying to make Fanny in love with him, and ends by falling in love with Fanny himself, much to his sister’s surprise, although Mary instantly approves of the match, both because she does like Fanny and believes she will be a good wife for her brother, but also as it will serve to maintain communication between the two families. Fanny however is distressed by his attentions as she neither trusts nor esteems him, and she even disbelieves a full on proposal from him and confirmation from Mary. I have seen too much of Mr Crawford not to understand his manners; if he understood me as well, he would, I dare say, behave differently.

Mary and Edmund have not been able to see eye to eye on the question of Edmund becoming a clergyman and living in his parish, and Edmund despairs of ever succeeding in making her his wife.

The ball is a mixed blessing for Fanny. She is uncomfortable being the centre of attention, and of Henry’s attention. The little contretemps of the necklace or chain for the amber cross upsets her, and she is of course unused to crowds and strangers. However she receives a most welcome and thoughtful gift from Edmund, she has two dances with him and she dances with William, and she enjoys seeing William appearing happy and confident in himself, and in the end …creeping slowly up the principal staircase, pursued by the ceaseless country dance, feverish with hopes and fears, soup and negus, sore-footed and fatigued, restless and agitated, yet feeling, in spite of everything, that a ball was indeed delightful.

Finally, there is the delight of William’s promotion, a scheme which has been pushed forward by Henry Crawford through his uncle the admiral. While this was no doubt done as another way to win Fanny’s good opinion, it does seem that William is worthy of the promotion and impressed the Admiral by his own merits as well.

So this section ends with a successful ball, a rejected proposal from Henry, a promotion for William, and a failure on the part of Edmund and Mary to find a way of reconciling their differences.

Please share your thoughts on the development of our characters and their relationships, and on the contrasts between Edmund and Henry, and Mary and Fanny, in their approach to relationships with friends or potential partners.