The History Book Club discussion

SUPREME COURT OF THE U.S.

>

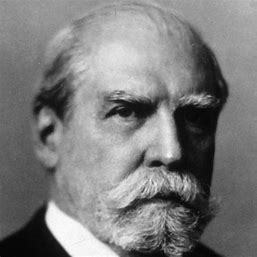

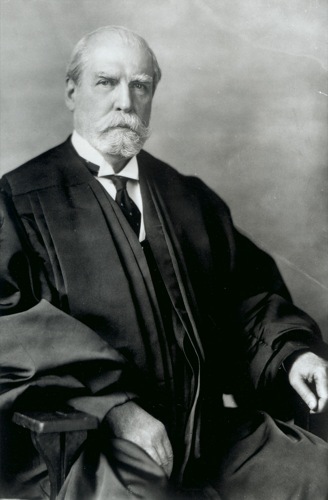

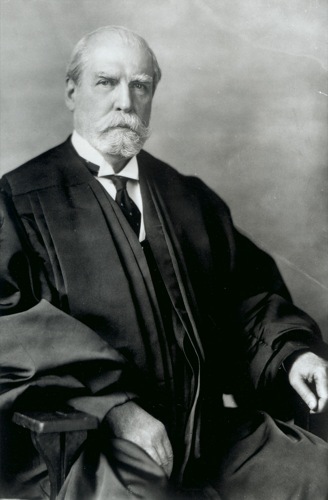

#11 - CHIEF JUSTICE CHARLES E. HUGHES

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

A book about Chief Justice Hughes

A book about Chief Justice Hughes by William G. Ross

by William G. Rossuring the 1930s the U.S. Supreme Court abandoned its longtime function as an arbiter of economic regulation and assumed its modern role as a guardian of personal liberties. William G. Ross analyzes this turbulent period of constitutional transition and the leadership of one of its central participants in The Chief Justiceship of Charles Evans Hughes, 1930-1941. Tapping into a broad array of primary and secondary sources, Ross explores the complex interaction between the court and the political, economic, and cultural forces that transformed the nation during the Great Depression.

Written with an appreciation for both the legal and historical contexts, this comprehensive volume explores how the Hughes Court removed constitutional impediments to the development of the administrative state by relaxing restrictions previously invoked to nullify federal and state economic regulatory legislation. Ross maps the expansion of safeguards for freedoms of speech, press, and religion and the extension of rights of criminal defendants and racial minorities. Ross holds that the Hughes Court's germinal decisions championing the rights of African Americans helped to lay the legal foundations for the civil rights movement.

Throughout his study Ross emphasizes how Chief Justice Hughes's brilliant administrative abilities and political acumen helped to preserve the Court's power and prestige during a period when the body's rulings were viewed as intensely controversial. Ross concludes that on balance the Hughes Court's decisions were more evolutionary than revolutionary but that the court also reflected the influence of the social changes of the era, especially after the appointmentof justices who espoused the New Deal values of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

More information about Chief Justice Hughes.

More information about Chief Justice Hughes.source: wikipedia

Charles Evans Hughes, Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was a lawyer and Republican politician from the State of New York. He served as the 36th Governor of New York (1907–1910), Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (1910–1916), United States Secretary of State (1921–1925), and the 11th Chief Justice of the United States (1930–1941). He was the Republican candidate in the 1916 U.S. Presidential election, losing to Woodrow Wilson. Hughes was an important leader of the progressive movement of the 1900s, a leading diplomat and New York lawyer in the days of Harding and Coolidge, and a leader of opposition to the New Deal in the 1930s. Historian Clinton Rossiter has hailed him as a leading American conservative.

Early life

Charles Evans Hughes was born on April 11, 1862, in Glens Falls, New York. In 1859, his family had moved to New York City, where his mother enrolled him in a private school. He was active in the Northern Baptist church, a Mainline Protestant denomination.

Hughes went to Madison University (now Colgate University) where he became a member of Delta Upsilon fraternity, then transferred to Brown University, where he continued as a member of Delta Upsilon and graduated in 1881 at age 19, youngest in his class, receiving second-highest honors. He entered Columbia Law School in 1882, and he graduated in 1884 with highest honors. While studying law, he taught at Delaware Academy.

In 1885, he met Antoinette Carter, the daughter of a senior partner of the law firm where he worked, and they were married in 1888. They had one son, Charles Evans Hughes, Jr. and three daughters, one of whom was Elizabeth Hughes Gossett, one of the first humans injected with insulin, and who later served as president of the Supreme Court Historical Society.

In 1891, Hughes left the practice of law to become a professor at the Cornell University Law School, but in 1893, he returned to his old law firm in New York City. At that time, in addition to practicing law, he taught at New York Law School with Woodrow Wilson. In 1905, he was appointed as counsel to a New York state legislative committee investigating utility rates. His uncovering of corruption led to lower gas rates in New York City. As a result, he was appointed to investigate the insurance industry in New York.

Governor of New York

Hughes served as the Governor of New York from 1907 to 1910. He defeated William Randolph Hearst in the 1906 election to gain the position, and he was the only Republican statewide candidate to win office. In 1908, he was offered the vice-presidential nomination by William Howard Taft, but he declined it to run again for Governor.

As the Governor, he pushed the passage of the Lessland Act, which gave him the power as governor to oversee civic officials as well as officials in state bureaucracies. This allowed him to fire many corrupt officials. He also managed to have the powers of the state's Public Service Commissions increased, and he attempted unsuccessfully to have their decisions exempted from judicial review. When two bills were passed to reduce railroad fares, Hughes vetoed them on that grounds that the rates should be set by expert commissioners rather than by elected ones. In his final year as the Governor, he had the state comptroller draw up an executive budget. This began a rationalization of state government and eventually it led to an enhancement of executive authority.

In 1908 Governor Hughes reviewed the clemency petition of Chester Gillette concerning the murder of Grace Brown. The governor denied the petition as well as an application for reprieve and Gillette was electrocuted in March of that year.

When Hughes left office, a prominent journal remarked "One can distinctly see the coming of a New Statism ... [of which] Gov. Hughes has been a leading prophet and exponent".

In 1909, he led an effort to incorporate Delta Upsilon fraternity. This was the first fraternity to incorporate, and he served as its first international president.

In 1926, Hughes was appointed by New York Governor Alfred E. Smith to be the chairman of a State Reorganization Commission through which Smith's plan to place the Governor as the head of a rationalized state government, was accomplished, bringing to realization what Hughes himself had envisioned.

Supreme Court

In October 1910, Hughes was appointed as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. He wrote for the court in Bailey v. Alabama 219 U.S. 219 (1911), which held that involuntary servitude encompassed more than just slavery, and Interstate Commerce Comm. v. Atchison T & SF R Co. 234 U.S. 294 (1914), holding that the Interstate Commerce Commission could regulate intrastate rates if they were significantly intertwined with interstate commerce.

On April 15, 1915, in the case of Frank v. Mangum, Justice Hughes along with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. were the two dissenting votes (7-2) that denied an appeal thus upholding the lower courts guilty verdict against Leo Frank.

Presidential candidate

He resigned from the Supreme Court on June 10, 1916,to be the Republican candidate for President in 1916. He was also endorsed by the Progressive Party. Hughes was defeated by Woodrow Wilson in a close election (separated by 23 electoral votes and 594,188 popular votes). The election hinged on California, where Wilson managed to win by 3,800 votes and its 13 electoral votes and thus Wilson was returned for a second term; Hughes had lost the endorsement of the California governor when he failed to show up for an appointment with him.

Hughes returned to public law practice, again at his old firm, Hughes, Rounds, Schurman & Dwight, today known as Hughes Hubbard & Reed LLP.

Secretary of State

Hughes' residence in 1921Hughes returned to government office in 1921 as Secretary of State under President Harding. As Secretary of State, in 1921 he convened the Washington Naval Conference for the limitation of naval armament among the Great Powers. He continued in office after Harding died and was succeeded by Coolidge, but resigned after Coolidge was elected to a full term. In 1922, September 23, he signed the Hughes - Peynado agreement, that ended the occupation of Dominican Republic by the United States (since 1916).

Various appointments

In 1907, Gov. Charles Evans Hughes became the first president of newly formed Northern Baptist Convention. He also served as President of the New York State Bar Association.

After leaving the State Department, he again rejoined his old partners at the Hughes firm, which included his son and future United States Solicitor General Charles E. Hughes, Jr., and was one of the nation's most sought-after advocates. From 1925 to 1930, for example, Hughes argued over 50 times before the U.S. Supreme Court. From 1926 to 1930, Hughes also served as a member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration and as a judge of the Permanent Court of International Justice in The Hague, Netherlands from 1928 to 1930. He was additionally a delegate to the Pan American Conference on Arbitration and Conciliation from 1928 to 1930. He was one of the co-founders in 1927 of the National Conference on Christians and Jews, now known as the National Conference for Community and Justice (NCCJ), along with S. Parkes Cadman and others, to oppose the Ku Klux Klan, anti-Catholicism, and anti-Semitism in the 1920s and 1930s.

In 1928 conservative business interests tried to interest Hughes in the GOP presidential nomination of 1928 instead of Herbert Hoover. Hughes, citing his age, turned down the offer.

Chief Justice

Herbert Hoover, who had appointed Hughes' son as Solicitor General in 1929, appointed Hughes Chief Justice of the United States in 1930, in which capacity he served until 1941. Hughes replaced former President William Howard Taft, a fellow Republican who had also lost a presidential election to Woodrow Wilson (in 1912) - and who, in 1910, had appointed Hughes to his first tenure on the Supreme Court.

His appointment was opposed by progressive elements in both parties who felt that he was too friendly to big business. Idaho Republican William E. Borah said on the United States Senate floor that confirming Hughes would constitute "placing upon the Court as Chief Justice one whose views are known upon these vital and important questions and whose views, in my opinion, however sincerely entertained, are not which ought to be incorporated in and made a permanent part of our legal and economic system." Nonetheless Hughes was confirmed as Chief Justice with a vote of 52 to 26.

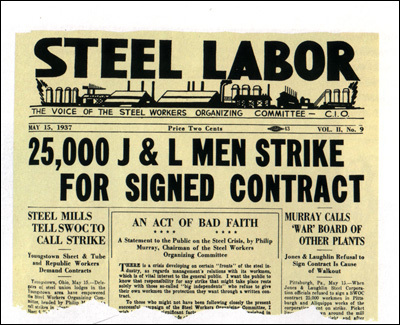

In 1937 when President Franklin D. Roosevelt attempted to pack the Court with five additional justices, Hughes worked behind the scenes to defeat the effort, which failed in the Senate. He wrote the opinion for the Court in Near v. Minnesota 283 U.S. 697 (1931)I/i>, which held prior restraints against the press are unconstitutional. He was often aligned with Justices Louis Brandeis, Harlan Fiske Stone, and Benjamin Cardozo in finding President Roosevelt's New Deal measures to be Constitutional. Although he wrote the opinion invalidating the National Recovery Administration in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States 295 U.S. 495 (1935), he wrote the opinions for the Court in NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. 301 U.S. 1 (1937), NLRB v. Friedman-Harry Marks Clothing Co., 301 U.S. 58 (1937), and West Coast Hotel v. Parrish 300 U.S. 379 (1937) which looked favorably on New Deal measures.

During Hughes' service as Chief Justice, the Supreme Court moved from its former quarters at the U.S. Capitol to the newly constructed Supreme Court building; the construction of the Supreme Court building had been authorized by Congress during President Taft's service as Chief Justice.

Hughes wrote twice as many constitutional opinions as any of his court's other members. "His opinions, in the view of one commentator, were concise and admirable, placing Hughes in the pantheon of great justices."

His "remarkable intellectual and social gifts . . . made him a superb leader and administrator. He had a photographic memory that few, if any, of his colleagues could match. Yet he was generous, kind, and forebearing in an institution where egos generally come in only one size: extra large!"

Later life

The grave of Charles Evans Hughes in Woodlawn Cemetery. For many years, he was a member of the Union League Club of New York and served as its president from 1917 to 1919. The Hughes Room in the club is named for him.

On August 27, 1948, Hughes died in Osterville, Massachusetts. His remains are interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in Bronx, New York.

A C-Span episode on the life of Hughes and his 1916 run for president:

A C-Span episode on the life of Hughes and his 1916 run for president:http://thecontenders.c-span.org/Conte...

FDR and Chief Justice Hughes: The President, the Supreme Court, and the Epic Battle Over the New Deal

FDR and Chief Justice Hughes: The President, the Supreme Court, and the Epic Battle Over the New Deal by James F. Simon (no photo)

by James F. Simon (no photo)Synopsis:

By the author of acclaimed books on the bitter clashes between Jefferson and Chief Justice Marshall on the shaping of the nation’s constitutional future, and between Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney over slavery, secession, and the presidential war powers. Roosevelt and Chief Justice Hughes's fight over the New Deal was the most critical struggle between an American president and a chief justice in the twentieth century.The confrontation threatened the New Deal in the middle of the nation’s worst depression. The activist president bombarded the Democratic Congress with a fusillade of legislative remedies that shut down insolvent banks, regulated stocks, imposed industrial codes, rationed agricultural production, and employed a quarter million young men in the Civilian Conservation Corps. But the legislation faced constitutional challenges by a conservative bloc on the Court determined to undercut the president. Chief Justice Hughes often joined the Court’s conservatives to strike down major New Deal legislation.

Frustrated, FDR proposed a Court-packing plan. His true purpose was to undermine the ability of the life-tenured Justices to thwart his popular mandate. Hughes proved more than a match for Roosevelt in the ensuing battle. In grudging admiration for Hughes, FDR said that the Chief Justice was the best politician in the country. Despite the defeat of his plan, Roosevelt never lost his confidence and, like Hughes, never ceded leadership. He outmaneuvered isolationist senators, many of whom had opposed his Court-packing plan, to expedite aid to Great Britain as the Allies hovered on the brink of defeat. He then led his country through World War II.

Just finished this one - I thought it was really good - I gave it 4 stars (4+ if good reads allowed) and can give it a hearty recommendation. It is not too technical and this non lawyer got a lot out of it.

Just finished this one - I thought it was really good - I gave it 4 stars (4+ if good reads allowed) and can give it a hearty recommendation. It is not too technical and this non lawyer got a lot out of it.The author was on CSPAN's BookTV last year talking about it and it caught my interest

Thanks Happy, I noticed you mentioned it on another thread and wanted to make sure to add the book here since it relates directly to Justice Hughes. Thanks for your recommendation, it indeed looks interesting.

Thanks Happy, I noticed you mentioned it on another thread and wanted to make sure to add the book here since it relates directly to Justice Hughes. Thanks for your recommendation, it indeed looks interesting.

I didn't see this thread or I would have posted it hear (my fault)

I didn't see this thread or I would have posted it hear (my fault)Is it OK to post a link to the author interview on BookTV for anyone interested?

That is ok, we have a lot of threads and are always adding to them. The CSPAN interview would be fine to post. We are careful not to link to third party sites such as reviews that are considered promotional in nature, but CSPAN should be fine. Thanks again.

That is ok, we have a lot of threads and are always adding to them. The CSPAN interview would be fine to post. We are careful not to link to third party sites such as reviews that are considered promotional in nature, but CSPAN should be fine. Thanks again.

US Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes goes for a morning walk in Washington DC

US Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes goes for a morning walk in Washington DChttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3BIMX...

It must have been pretty tough to get privacy and enjoy your walk when somebody was in a wagon in front of you facing you and taking photos.

I thought that video was pretty funny actually with all that was going on while he was taking the walk.

I thought that video was pretty funny actually with all that was going on while he was taking the walk.

The Supreme Court Building

The Supreme Court Building

"The Republic endures and this is the symbol of its faith." These words, spoken by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes in laying the cornerstone for the Supreme Court Building on October 13, 1932, express the importance of the Supreme Court in the American system.

Yet surprisingly, despite its role as a coequal branch of government, the Supreme Court was not provided with a building of its own until 1935, the 146th year of its existence.

Source: Supreme Court of the United States

FDR and Chief Justice Hughes: The President, the Supreme Court, and the Epic Battle Over the New Deal

FDR and Chief Justice Hughes: The President, the Supreme Court, and the Epic Battle Over the New Deal by James F. Simon (no photo)

by James F. Simon (no photo)Synopsis:

By the author of acclaimed books on the bitter clashes between Jefferson and Chief Justice Marshall on the shaping of the nation’s constitutional future, and between Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney over slavery, secession, and the presidential war powers. Roosevelt and Chief Justice Hughes's fight over the New Deal was the most critical struggle between an American president and a chief justice in the twentieth century.

The confrontation threatened the New Deal in the middle of the nation’s worst depression. The activist president bombarded the Democratic Congress with a fusillade of legislative remedies that shut down insolvent banks, regulated stocks, imposed industrial codes, rationed agricultural production, and employed a quarter million young men in the Civilian Conservation Corps. But the legislation faced constitutional challenges by a conservative bloc on the Court determined to undercut the president. Chief Justice Hughes often joined the Court’s conservatives to strike down major New Deal legislation.

Frustrated, FDR proposed a Court-packing plan. His true purpose was to undermine the ability of the life-tenured Justices to thwart his popular mandate. Hughes proved more than a match for Roosevelt in the ensuing battle. In grudging admiration for Hughes, FDR said that the Chief Justice was the best politician in the country. Despite the defeat of his plan, Roosevelt never lost his confidence and, like Hughes, never ceded leadership. He outmaneuvered isolationist senators, many of whom had opposed his Court-packing plan, to expedite aid to Great Britain as the Allies hovered on the brink of defeat. He then led his country through World War II.

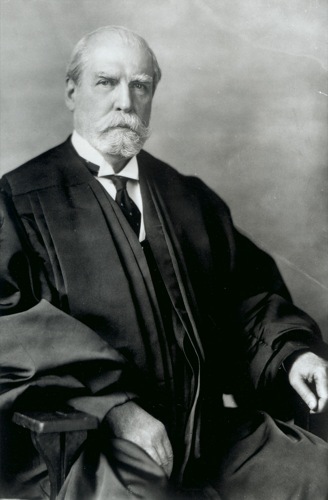

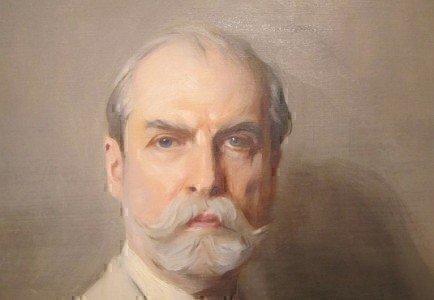

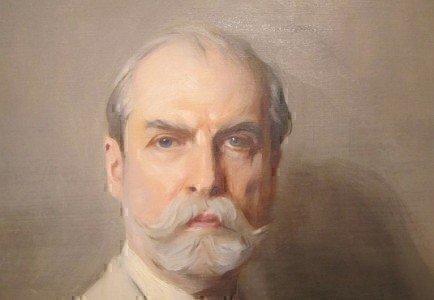

Charles Evans Hughes

Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States February 24, 1930 - June 30, 1941

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States October 10, 1910 - June 10, 1916

The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Charles Evans Hughes (1862-1948) had an extraordinary public career. In addition to serving as chief justice in 1930-1941, he was New York governor (1907-1910), Supreme Court justice (1910-1916), Republican presidential candidate (1916), secretary of state (1921-1925), and World Court judge (1928-1930). His rise in public life was due largely to his intelligence, sense of duty, capacity for hard work, and self-sufficiency.

A precocious child, Hughes learned to read at the age of three and a half. Before he was six, he was reading and reciting verses from the New Testament, doing mental arithmetic, and studying French and German. After only three and a half years of formal schooling, he graduated from high school at the age of thirteen. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Brown University, Hughes went to Columbia Law School, where he ranked first in his class. When he took the New York bar examination in 1884, he received the highest grade given up to that time, 99 1/2 percent. He had a photographic memory and could read a paragraph at a glance, a treatise in an evening. These abilities made Hughes a formidable opponent at the bar-he practiced law for almost thirty years-and contributed to his success as a politician, judge, and negotiator.

To Hughes, duty meant doing worthy things and doing them well. He drove himself mercilessly. His sense of duty led him to public service and enabled him to excel in almost everything he undertook. Hughes had no personal or political advisers, no favorites, no confidants. Herbert Hoover once said that he was the most self-contained man he had ever known. He made his own judgments based on his own analyses. At work, he was organized, intense, and serious, and had little time for pleasantries. That side of him gave rise to an aloof, cool, and humorless public image. At home, however, he showed warmth and humor; he was a sensitive husband and a caring father of three children.

Hughes came close to being elected president in 1916. A shift of less than four thousand votes in California would have given him that state’s electoral votes and the presidency. If Hughes had not projected such an austere public image (or if he had secured the support of Governor Hiram W. Johnson), he would probably have been elected.

As secretary of state in the Harding and Coolidge administrations, Hughes negotiated a separate peace treaty with Germany when the Senate failed to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. He also chaired the Washington Disarmament Conference in 1921-1922, supported U.S. participation in the World Court, and withheld American recognition of the Soviet Union. Although he served two presidents who made political capital of rejecting Woodrow Wilson’s vision of internationalism, he conducted a foreign policy that recognized the international responsibilities of the United States. In Latin America he sought a means to reduce U.S. intervention while defending a traditional conception of the national interest. In Europe he asserted a constructive role for the United States while avoiding formal commitments that would have involved Congress or excited public opinion.

As chief justice, Hughes led the Supreme Court during one of its most difficult periods. He presided over the Court’s transformation of its basic role from defender of property rights to protector of civil liberties, writing the period’s landmark opinions on freedom of speech and press-Near v. Minnesota, Stromberg v. California, and DeJonge v. Oregon. He also successfully opposed President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s plan to ‘pack’ the Supreme Court in 1937.

The Reader’s Companion to American History. Eric Foner and John A. Garraty, Editors. Copyright © 1991 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Links:

http://www.history.com/topics/charles...

https://www.oyez.org/justices/charles...

Other:

by Lewis L. Gould (no photo)

by Lewis L. Gould (no photo)

(no image) The Autobiographical Notes Of Charles Evans Hughes by

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes

Source(s): The History Channel, Oyez

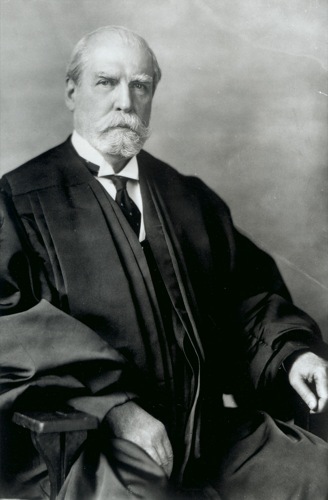

Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States February 24, 1930 - June 30, 1941

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States October 10, 1910 - June 10, 1916

The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Charles Evans Hughes (1862-1948) had an extraordinary public career. In addition to serving as chief justice in 1930-1941, he was New York governor (1907-1910), Supreme Court justice (1910-1916), Republican presidential candidate (1916), secretary of state (1921-1925), and World Court judge (1928-1930). His rise in public life was due largely to his intelligence, sense of duty, capacity for hard work, and self-sufficiency.

A precocious child, Hughes learned to read at the age of three and a half. Before he was six, he was reading and reciting verses from the New Testament, doing mental arithmetic, and studying French and German. After only three and a half years of formal schooling, he graduated from high school at the age of thirteen. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Brown University, Hughes went to Columbia Law School, where he ranked first in his class. When he took the New York bar examination in 1884, he received the highest grade given up to that time, 99 1/2 percent. He had a photographic memory and could read a paragraph at a glance, a treatise in an evening. These abilities made Hughes a formidable opponent at the bar-he practiced law for almost thirty years-and contributed to his success as a politician, judge, and negotiator.

To Hughes, duty meant doing worthy things and doing them well. He drove himself mercilessly. His sense of duty led him to public service and enabled him to excel in almost everything he undertook. Hughes had no personal or political advisers, no favorites, no confidants. Herbert Hoover once said that he was the most self-contained man he had ever known. He made his own judgments based on his own analyses. At work, he was organized, intense, and serious, and had little time for pleasantries. That side of him gave rise to an aloof, cool, and humorless public image. At home, however, he showed warmth and humor; he was a sensitive husband and a caring father of three children.

Hughes came close to being elected president in 1916. A shift of less than four thousand votes in California would have given him that state’s electoral votes and the presidency. If Hughes had not projected such an austere public image (or if he had secured the support of Governor Hiram W. Johnson), he would probably have been elected.

As secretary of state in the Harding and Coolidge administrations, Hughes negotiated a separate peace treaty with Germany when the Senate failed to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. He also chaired the Washington Disarmament Conference in 1921-1922, supported U.S. participation in the World Court, and withheld American recognition of the Soviet Union. Although he served two presidents who made political capital of rejecting Woodrow Wilson’s vision of internationalism, he conducted a foreign policy that recognized the international responsibilities of the United States. In Latin America he sought a means to reduce U.S. intervention while defending a traditional conception of the national interest. In Europe he asserted a constructive role for the United States while avoiding formal commitments that would have involved Congress or excited public opinion.

As chief justice, Hughes led the Supreme Court during one of its most difficult periods. He presided over the Court’s transformation of its basic role from defender of property rights to protector of civil liberties, writing the period’s landmark opinions on freedom of speech and press-Near v. Minnesota, Stromberg v. California, and DeJonge v. Oregon. He also successfully opposed President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s plan to ‘pack’ the Supreme Court in 1937.

The Reader’s Companion to American History. Eric Foner and John A. Garraty, Editors. Copyright © 1991 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Links:

http://www.history.com/topics/charles...

https://www.oyez.org/justices/charles...

Other:

by Lewis L. Gould (no photo)

by Lewis L. Gould (no photo)(no image) The Autobiographical Notes Of Charles Evans Hughes by

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans HughesSource(s): The History Channel, Oyez

The Hughes Court, 1930-1941

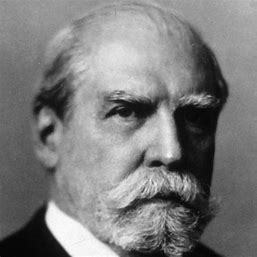

Justice Charles Evans Hughes, biography.com

Nicknamed the "roving Justices," new Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts sometimes joined the "four horsemen"–Justices George Sutherland, Pierce Butler, James C. McReynolds, and Willis Van Devanter--sometimes joined three Judges more willing to accept laws however meddlesome. These three were Louis D. Brandeis, Harlan Fiske Stone, and Oliver Wendell Holmes until he retired in 1932. Benjamin N. Cardozo succeeded him, and often voted with Brandeis and Stone.

In 1925, while the Court was deciding the Benjamin Gitlow case, Minnesota legislators were passing a new statute. It provided that a court order could silence, as "public nuisances," periodicals that published "malicious, scandalous, and defamatory" material.

"Unfortunately we are both former editors of a local scandal sheet, a distinction we regret," conceded J. M. Near and his partner in the first issue of the Saturday Press, but they promised to fight crime in Minneapolis. They called the police chief a "cuddler of criminals" who protected "rat gamblers." They abused the county attorney, who sued Near; the state’s highest court ordered the paper suppressed.

Citing the Schenck and Gitlow decisions, Near’s lawyer appealed to the Supreme Court, which struck down the state law in 1931.

For four dissenters, Pierce Butler quoted with evident distaste Near’s outbursts at "snake-faced" Jewish gangsters; peace and order need legal protection from such publishers, Butler insisted.

For the majority, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes analyzed this "unusual, if not unique" law. If anyone published something "scandalous" a Minnesota court might close his paper permanently for damaging public morals. But charges of corruption in office always make public scandals, Hughes pointed out. Anyone defamed in print may sue for libel, he added emphatically.

However disgusting Near’s words, said Hughes, the words of the Constitution controlled the decision, and they demand a free press without censorship. Criticism may offend public officials, it may even remove them from office; but trashy or trenchant, the press may not be suppressed by law.

How citizens use liberty has confronted the Justices again and again, in cases of violence as well as scandal.

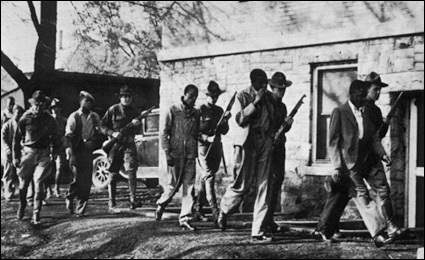

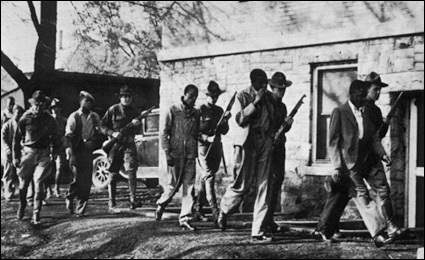

Alabama militia had machine guns on the courthouse roof, said newspaper reports from Scottsboro; mobs had a band playing "There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight"; and amid the clamor, nine black youths waited behind bars for trial on charges of raping two white women.

Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, two white mill workers, were riding a slow freight from Chattanooga on their way home to Huntsville on March 25, 1931. Across the Alabama line, white and black hoboes on board got into a fight; some jumped and some were thrown from the train. Alerted by telephone, a sheriff’s posse stopped the train, arrested the nine Negroes still on it, and took them to jail in the Jackson County seat, Scottsboro. Then Victoria Price claimed they had raped her and Ruby Bates.

Doctors found no proof of this story, but a frenzied crowd gathered swiftly. Ten thousand people, many armed, were there a week later when the nine went on trial.

Because state law provided a death penalty, it required the court to appoint one or two defense lawyers. At the arraignment, the judge told all seven members of the county bar to serve. Six made excuses.

In three trials, completed in three days, jurors found eight defendants guilty; they could not agree on Roy Wright, one of the youngest. The eight were sentenced to death.

Of these nine, the oldest might have reached 21; one was crippled, one nearly blind; each signed his name by "X"—"his mark." All swore they were innocent.

On appeal, Alabama’s highest court ordered a new hearing for one of the nine, Eugene Williams; but it upheld the other proceedings.

When a petition in the name of Ozie Powell reached the Supreme Court, seven Justices agreed that no lawyer had helped the defendants at the trials. Justice George Sutherland wrote the Court’s opinion. Facing a possible death sentence, unable to hire a lawyer, too young or ignorant or dull to defend himself—such a defendant has a constitutional right to counsel, and his counsel must fight for him, Sutherland said.

Sent back for retrial, the cases went on. Norris v. Alabama reached the Supreme Court in 1935; Chief Justice Hughes ruled that because qualified Negroes did not serve on jury duty in those counties, the trials had been unconstitutional.

"We still have the right to secede!" retorted one southern official. Again the prisoners stood trial. Alabama dropped rape charges against some; others were conflicted but later paroled; one escaped.

The Supreme Court’s rulings stood—if a defendant lacks a lawyer and a fairly chosen jury, the Constitution can help him.

The Scottsboro Boys in 1937. Library of Congress

Grocer Leo Nebbia, who violated the New York Milk Control

Board's order to fix prices of milk in order to stabilize

the market. Rochester Times Union

And the Constitution forbids any state’s prosecuting attorneys to use evidence they know is false; the Court announced this in 1935, when Tom Mooney had spent nearly 20 years behind the bars of a California prison.

To rally support for a stronger Army and Navy, San Franciscans had organized a huge parade for "Preparedness Day," July 22, 1916. As the marchers set out, a bomb exploded: 10 victims died, 40 were injured. Mooney, known as a friend of anarchists and a labor radical, was convicted of first-degree murder; soon it appeared that the chief witness against him had lied under oath. President Wilson persuaded the Governor of California to commute the death sentence to life imprisonment. For years labor called Mooney a martyr to injustice.

Finally Mooney’s lawyers applied to the Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus, and won a new ruling—if a state uses perjured witnesses, knowing that they lie, it violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of due process of law; it must provide ways to set aside such tainted convictions. The case went back to the state. In 1939 Governor Culbert Olson granted Mooney a pardon; free, he was almost forgotten.

When the stock market collapsed in 1929 and the American economy headed toward ruin, President Hoover had called for emergency measures. The states tried to cope with the general disaster. Before long, cases on their new laws began to reach the Supreme Court. Franklin D. Roosevelt won the 1932 Presidential election, and by June 1933, Congress had passed 15 major laws for national remedies.

Almost 20,000,000 people depended on federal relief by 1934, when the Supreme Court decided the case of Leo Nebbia. New York’s milk-control board had fixed the lawful price of milk at nine cents a quart; the state had convicted Nebbia, a Rochester grocer, of selling two quarts and a five-cent loaf of bread for only 18 cents. Nebbia had appealed. Justice Owen Roberts wrote the majority opinion, upholding the New York law; he went beyond the 1887 decision in the Granger cases to declare that a state may regulate any business whatever, when the public good requires it. The "four horsemen" dissented; but Roosevelt’s New Dealers began to hope their economic program might win the Supreme Court’s approval after all.

They were wrong. Considering a New Deal law for the first time, in January 1935, the Court held that one part of the National Industrial Recovery Act gave the President too much lawmaking power.

The Court did sustain the policy of reducing the dollar’s value in gold. But a five-to-four decision in May made a railroad pension law unconstitutional. Then all nine Justices vetoed a law to relieve farm debtors, and killed the National Recovery Administration; FDR denounced their "horse-and-buggy" definition of interstate commerce.

While the Court moved into its splendid new building, criticism of its decisions grew sharper and angrier. The whole federal judiciary came under attack as district courts issued—over a two-year period—some 1,600 injunctions to keep Acts of Congress from being enforced. But the Court seemed to ignore the clamor.

Farming lay outside Congressional power, said six Justices in 1936; they called the Agricultural Adjustment Act invalid for dealing with state problems. Brandeis and Cardozo joined Stone in a scathing dissent: "Courts are not the only agency . . . That must be assumed to have capacity to govern." But two decisions that followed denied power to both the federal and the state governments.

In a law to strengthen the chaotic soft-coal industry and help the almost starving miners, Congress had dealt with prices in one section, with working conditions and wages in another. If the courts held one section invalid, the other might survive. When a test case came up, seven coal-mining states urged the Court to uphold the Act, but five Justices called the whole law unconstitutional for trying to cure "local evils"—state problems.

Then they threw out a New York law that set minimum wages for women and children; they said states could not regulate matters of individual liberty.

Agitator and Martyr for Labor, Tom Mooney leaves

San Quentin in 1939. Library of Congress

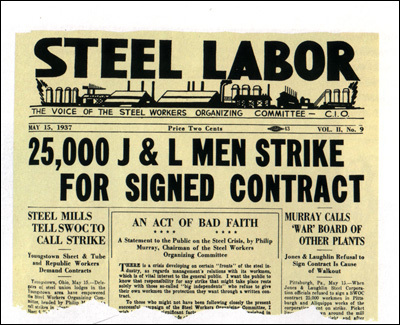

This 1937 steel strike occurred in Pittsburgh following the Supreme Court's decision to order union employees fired from their jobs at Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation reinstated. Library of Congress

By forbidding Congress and the states to act, Justice Harlan F. Stone confided bitterly to his sister, the Court had apparently "tied Uncle Sam up in a hard knot."

Link to remainder of article: http://supremecourthistory.org/timeli...

Other:

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)

Source: The Supreme Court Historical Society

Justice Charles Evans Hughes, biography.com

Nicknamed the "roving Justices," new Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts sometimes joined the "four horsemen"–Justices George Sutherland, Pierce Butler, James C. McReynolds, and Willis Van Devanter--sometimes joined three Judges more willing to accept laws however meddlesome. These three were Louis D. Brandeis, Harlan Fiske Stone, and Oliver Wendell Holmes until he retired in 1932. Benjamin N. Cardozo succeeded him, and often voted with Brandeis and Stone.

In 1925, while the Court was deciding the Benjamin Gitlow case, Minnesota legislators were passing a new statute. It provided that a court order could silence, as "public nuisances," periodicals that published "malicious, scandalous, and defamatory" material.

"Unfortunately we are both former editors of a local scandal sheet, a distinction we regret," conceded J. M. Near and his partner in the first issue of the Saturday Press, but they promised to fight crime in Minneapolis. They called the police chief a "cuddler of criminals" who protected "rat gamblers." They abused the county attorney, who sued Near; the state’s highest court ordered the paper suppressed.

Citing the Schenck and Gitlow decisions, Near’s lawyer appealed to the Supreme Court, which struck down the state law in 1931.

For four dissenters, Pierce Butler quoted with evident distaste Near’s outbursts at "snake-faced" Jewish gangsters; peace and order need legal protection from such publishers, Butler insisted.

For the majority, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes analyzed this "unusual, if not unique" law. If anyone published something "scandalous" a Minnesota court might close his paper permanently for damaging public morals. But charges of corruption in office always make public scandals, Hughes pointed out. Anyone defamed in print may sue for libel, he added emphatically.

However disgusting Near’s words, said Hughes, the words of the Constitution controlled the decision, and they demand a free press without censorship. Criticism may offend public officials, it may even remove them from office; but trashy or trenchant, the press may not be suppressed by law.

How citizens use liberty has confronted the Justices again and again, in cases of violence as well as scandal.

Alabama militia had machine guns on the courthouse roof, said newspaper reports from Scottsboro; mobs had a band playing "There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight"; and amid the clamor, nine black youths waited behind bars for trial on charges of raping two white women.

Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, two white mill workers, were riding a slow freight from Chattanooga on their way home to Huntsville on March 25, 1931. Across the Alabama line, white and black hoboes on board got into a fight; some jumped and some were thrown from the train. Alerted by telephone, a sheriff’s posse stopped the train, arrested the nine Negroes still on it, and took them to jail in the Jackson County seat, Scottsboro. Then Victoria Price claimed they had raped her and Ruby Bates.

Doctors found no proof of this story, but a frenzied crowd gathered swiftly. Ten thousand people, many armed, were there a week later when the nine went on trial.

Because state law provided a death penalty, it required the court to appoint one or two defense lawyers. At the arraignment, the judge told all seven members of the county bar to serve. Six made excuses.

In three trials, completed in three days, jurors found eight defendants guilty; they could not agree on Roy Wright, one of the youngest. The eight were sentenced to death.

Of these nine, the oldest might have reached 21; one was crippled, one nearly blind; each signed his name by "X"—"his mark." All swore they were innocent.

On appeal, Alabama’s highest court ordered a new hearing for one of the nine, Eugene Williams; but it upheld the other proceedings.

When a petition in the name of Ozie Powell reached the Supreme Court, seven Justices agreed that no lawyer had helped the defendants at the trials. Justice George Sutherland wrote the Court’s opinion. Facing a possible death sentence, unable to hire a lawyer, too young or ignorant or dull to defend himself—such a defendant has a constitutional right to counsel, and his counsel must fight for him, Sutherland said.

Sent back for retrial, the cases went on. Norris v. Alabama reached the Supreme Court in 1935; Chief Justice Hughes ruled that because qualified Negroes did not serve on jury duty in those counties, the trials had been unconstitutional.

"We still have the right to secede!" retorted one southern official. Again the prisoners stood trial. Alabama dropped rape charges against some; others were conflicted but later paroled; one escaped.

The Supreme Court’s rulings stood—if a defendant lacks a lawyer and a fairly chosen jury, the Constitution can help him.

The Scottsboro Boys in 1937. Library of Congress

Grocer Leo Nebbia, who violated the New York Milk Control

Board's order to fix prices of milk in order to stabilize

the market. Rochester Times Union

And the Constitution forbids any state’s prosecuting attorneys to use evidence they know is false; the Court announced this in 1935, when Tom Mooney had spent nearly 20 years behind the bars of a California prison.

To rally support for a stronger Army and Navy, San Franciscans had organized a huge parade for "Preparedness Day," July 22, 1916. As the marchers set out, a bomb exploded: 10 victims died, 40 were injured. Mooney, known as a friend of anarchists and a labor radical, was convicted of first-degree murder; soon it appeared that the chief witness against him had lied under oath. President Wilson persuaded the Governor of California to commute the death sentence to life imprisonment. For years labor called Mooney a martyr to injustice.

Finally Mooney’s lawyers applied to the Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus, and won a new ruling—if a state uses perjured witnesses, knowing that they lie, it violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of due process of law; it must provide ways to set aside such tainted convictions. The case went back to the state. In 1939 Governor Culbert Olson granted Mooney a pardon; free, he was almost forgotten.

When the stock market collapsed in 1929 and the American economy headed toward ruin, President Hoover had called for emergency measures. The states tried to cope with the general disaster. Before long, cases on their new laws began to reach the Supreme Court. Franklin D. Roosevelt won the 1932 Presidential election, and by June 1933, Congress had passed 15 major laws for national remedies.

Almost 20,000,000 people depended on federal relief by 1934, when the Supreme Court decided the case of Leo Nebbia. New York’s milk-control board had fixed the lawful price of milk at nine cents a quart; the state had convicted Nebbia, a Rochester grocer, of selling two quarts and a five-cent loaf of bread for only 18 cents. Nebbia had appealed. Justice Owen Roberts wrote the majority opinion, upholding the New York law; he went beyond the 1887 decision in the Granger cases to declare that a state may regulate any business whatever, when the public good requires it. The "four horsemen" dissented; but Roosevelt’s New Dealers began to hope their economic program might win the Supreme Court’s approval after all.

They were wrong. Considering a New Deal law for the first time, in January 1935, the Court held that one part of the National Industrial Recovery Act gave the President too much lawmaking power.

The Court did sustain the policy of reducing the dollar’s value in gold. But a five-to-four decision in May made a railroad pension law unconstitutional. Then all nine Justices vetoed a law to relieve farm debtors, and killed the National Recovery Administration; FDR denounced their "horse-and-buggy" definition of interstate commerce.

While the Court moved into its splendid new building, criticism of its decisions grew sharper and angrier. The whole federal judiciary came under attack as district courts issued—over a two-year period—some 1,600 injunctions to keep Acts of Congress from being enforced. But the Court seemed to ignore the clamor.

Farming lay outside Congressional power, said six Justices in 1936; they called the Agricultural Adjustment Act invalid for dealing with state problems. Brandeis and Cardozo joined Stone in a scathing dissent: "Courts are not the only agency . . . That must be assumed to have capacity to govern." But two decisions that followed denied power to both the federal and the state governments.

In a law to strengthen the chaotic soft-coal industry and help the almost starving miners, Congress had dealt with prices in one section, with working conditions and wages in another. If the courts held one section invalid, the other might survive. When a test case came up, seven coal-mining states urged the Court to uphold the Act, but five Justices called the whole law unconstitutional for trying to cure "local evils"—state problems.

Then they threw out a New York law that set minimum wages for women and children; they said states could not regulate matters of individual liberty.

Agitator and Martyr for Labor, Tom Mooney leaves

San Quentin in 1939. Library of Congress

This 1937 steel strike occurred in Pittsburgh following the Supreme Court's decision to order union employees fired from their jobs at Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation reinstated. Library of Congress

By forbidding Congress and the states to act, Justice Harlan F. Stone confided bitterly to his sister, the Court had apparently "tied Uncle Sam up in a hard knot."

Link to remainder of article: http://supremecourthistory.org/timeli...

Other:

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)Source: The Supreme Court Historical Society

Charles Evans Hughes

* Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States - October 10, 1910 - June 10, 1916

* Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States - February 13, 1930 - June 30, 1941

The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Charles Evans Hughes was born and raised in New York. He was educated by his parents but matriculated at Madison College (now Colgate) when he was fourteen. He completed his undergraduate education at Brown. Hughes taught briefly before entering Columbia Law School. He scored an amazing 99 1/2 on his bar exam at the age of 22. He practiced law in New York for 20 years, though he did hold an appointment at Cornell Law School for a few years in that period.

Hughes earned national recognition for his investigation into illegal rate-making and fraud in the insurance industry. With an endorsement from Theodore Roosevelt, Hughes ran successfully for New York governor, defeating Democrat William Randolph Hearst in 1906. In 1910, Hughes accepted nomination to the High Court from President Taft. Six years later, Hughes resigned to run against Woodrow Wilson for the presidency as the nominee of the Republican and Progressive Parties. He lost by a mere 23 electoral votes.

After a brief stint in private practice, Hughes was called to politics again, this time as secretary of state for Warren G. Harding. Hughes continued in this role during the presidency of Calvin Coolidge. Hughes's nomination to be chief justice met with opposition from Democrats who viewed Hughes as too closely aligned with corporate America. Their opposition was insufficient to deny Hughes the center chair, however.

Hughes authored twice as many constitutional opinions as any other member of his Court. His opinions, in the view of one commentator, were concise and admirable, placing Hughes in the pantheon of great justices.

Hughes had remarkable intellectual and social gifts that made him a superb leader and administrator. He had a photographic memory that few, if any, of his colleagues could match. Yet he was generous, kind, and forebearing in an institution where egos generally come in only one size: extra large!

Other:

by William G. Ross (no photo)

by William G. Ross (no photo)

Source: Oyez

* Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States - October 10, 1910 - June 10, 1916

* Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States - February 13, 1930 - June 30, 1941

The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Charles Evans Hughes was born and raised in New York. He was educated by his parents but matriculated at Madison College (now Colgate) when he was fourteen. He completed his undergraduate education at Brown. Hughes taught briefly before entering Columbia Law School. He scored an amazing 99 1/2 on his bar exam at the age of 22. He practiced law in New York for 20 years, though he did hold an appointment at Cornell Law School for a few years in that period.

Hughes earned national recognition for his investigation into illegal rate-making and fraud in the insurance industry. With an endorsement from Theodore Roosevelt, Hughes ran successfully for New York governor, defeating Democrat William Randolph Hearst in 1906. In 1910, Hughes accepted nomination to the High Court from President Taft. Six years later, Hughes resigned to run against Woodrow Wilson for the presidency as the nominee of the Republican and Progressive Parties. He lost by a mere 23 electoral votes.

After a brief stint in private practice, Hughes was called to politics again, this time as secretary of state for Warren G. Harding. Hughes continued in this role during the presidency of Calvin Coolidge. Hughes's nomination to be chief justice met with opposition from Democrats who viewed Hughes as too closely aligned with corporate America. Their opposition was insufficient to deny Hughes the center chair, however.

Hughes authored twice as many constitutional opinions as any other member of his Court. His opinions, in the view of one commentator, were concise and admirable, placing Hughes in the pantheon of great justices.

Hughes had remarkable intellectual and social gifts that made him a superb leader and administrator. He had a photographic memory that few, if any, of his colleagues could match. Yet he was generous, kind, and forebearing in an institution where egos generally come in only one size: extra large!

Other:

by William G. Ross (no photo)

by William G. Ross (no photo)Source: Oyez

The remarkable career of Charles Evans Hughes

By SCOTT BOMBOY April 11, 2020

On the anniversary of his birthday in New York state, Constitution Daily looks back at the career of Charles Evans Hughes, former Chief Justice and a man who lost the 1916 presidential election by 4,000 votes cast in California.

Hughes was a stalwart of the Republican Party in an era when the GOP dominated the White House. Between 1860 and 1932, Republicans sat in the Oval Office for 56 out of 72 years, with only Grover Cleveland and Woodrow Wilson winning elections as Democrats.

Hughes, however, never made it to the presidency, though he was incredibly close in 1916 as he contested Wilson’s re-election. Hughes reportedly went to sleep on Election Night believing that he had won after the New York Times announced that he was the winner, not taking California into account.

Hughes’s path to the 1916 GOP nomination as a third-ballot convention choice was filled with high-profile government positions. Hughes graduated first in his class at Columbia law and received a 99.5% score on his bar exams. A very successful private lawyer, Hughes ran for and won the governorship of New York state in 1906, defeating William Randolph Hearst.

Four years later, President William Howard Taft appointed Hughes to the United States Supreme Court. In June 1916, Hughes left the Court to jump into the contested 1916 Republican nomination race. Former President Theodore Roosevelt couldn’t attract enough support within the reunited party, and Republican leaders saw Hughes as a moderate who could compete with President Woodrow Wilson. Hughes led on all three convention ballots and left the Court on June 10th when he was nominated.

In the general election, Hughes had the advantage of being the candidate for the largest national political party. But his failure to gain the support of California Governor Hiram Johnson was seen as a tactical mistake that cost him the election.

Undaunted, Hughes returned to his private law practice, and he declined to run for President in 1920. Instead, newly elected President Warren Harding nominated Hughes as Secretary of State in 1921. In that office, Hughes directed the Washington Naval Conference and helped establish a professional foreign service.

Hughes resigned as Secretary when Calvin Coolidge started his first full term, but he continued in public service, serving on the Permanent Court of International Justice at The Hague. In 1930, President Herbert Hoover asked Hughes to return to the Supreme Court as Chief Justice.

During his second Court term, Hughes was known for his balanced handling of Court matters; his role in diffusing President Franklin Roosevelt’s efforts to pack the Supreme Court with favorable justices; and his famous 1937 letter to the Senate that stated, “the present number of justices is thought to be large enough so far as the prompt, adequate and efficient conduct of the work of the court is concerned.”

Hughes retired from the Supreme Court in 1941 at the age of 79 and died in 1948 while in Massachusetts. "He took his seat at the center of the Court with a mastery, I suspect, unparalleled in the history of the Court,” said Justice Felix Frankfurter.

Link to article: https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/t...

More:

by James F. Simon (no photo)

by James F. Simon (no photo)

Source: Constitution Daily

By SCOTT BOMBOY April 11, 2020

On the anniversary of his birthday in New York state, Constitution Daily looks back at the career of Charles Evans Hughes, former Chief Justice and a man who lost the 1916 presidential election by 4,000 votes cast in California.

Hughes was a stalwart of the Republican Party in an era when the GOP dominated the White House. Between 1860 and 1932, Republicans sat in the Oval Office for 56 out of 72 years, with only Grover Cleveland and Woodrow Wilson winning elections as Democrats.

Hughes, however, never made it to the presidency, though he was incredibly close in 1916 as he contested Wilson’s re-election. Hughes reportedly went to sleep on Election Night believing that he had won after the New York Times announced that he was the winner, not taking California into account.

Hughes’s path to the 1916 GOP nomination as a third-ballot convention choice was filled with high-profile government positions. Hughes graduated first in his class at Columbia law and received a 99.5% score on his bar exams. A very successful private lawyer, Hughes ran for and won the governorship of New York state in 1906, defeating William Randolph Hearst.

Four years later, President William Howard Taft appointed Hughes to the United States Supreme Court. In June 1916, Hughes left the Court to jump into the contested 1916 Republican nomination race. Former President Theodore Roosevelt couldn’t attract enough support within the reunited party, and Republican leaders saw Hughes as a moderate who could compete with President Woodrow Wilson. Hughes led on all three convention ballots and left the Court on June 10th when he was nominated.

In the general election, Hughes had the advantage of being the candidate for the largest national political party. But his failure to gain the support of California Governor Hiram Johnson was seen as a tactical mistake that cost him the election.

Undaunted, Hughes returned to his private law practice, and he declined to run for President in 1920. Instead, newly elected President Warren Harding nominated Hughes as Secretary of State in 1921. In that office, Hughes directed the Washington Naval Conference and helped establish a professional foreign service.

Hughes resigned as Secretary when Calvin Coolidge started his first full term, but he continued in public service, serving on the Permanent Court of International Justice at The Hague. In 1930, President Herbert Hoover asked Hughes to return to the Supreme Court as Chief Justice.

During his second Court term, Hughes was known for his balanced handling of Court matters; his role in diffusing President Franklin Roosevelt’s efforts to pack the Supreme Court with favorable justices; and his famous 1937 letter to the Senate that stated, “the present number of justices is thought to be large enough so far as the prompt, adequate and efficient conduct of the work of the court is concerned.”

Hughes retired from the Supreme Court in 1941 at the age of 79 and died in 1948 while in Massachusetts. "He took his seat at the center of the Court with a mastery, I suspect, unparalleled in the history of the Court,” said Justice Felix Frankfurter.

Link to article: https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/t...

More:

by James F. Simon (no photo)

by James F. Simon (no photo)Source: Constitution Daily

Books mentioned in this topic

FDR and Chief Justice Hughes: The President, the Supreme Court, and the Epic Battle Over the New Deal (other topics)The Chief Justiceship of Charles Evans Hughes, 1930-1941 (other topics)

Supreme Power: Franklin Roosevelt vs. the Supreme Court (other topics)

The First Modern Clash over Federal Power: Wilson versus Hughes in the Presidential Election of 1916 (other topics)

The Autobiographical Notes of Charles Evans Hughes (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

James F. Simon (other topics)William G. Ross (other topics)

Jeff Shesol (other topics)

Lewis L. Gould (other topics)

Charles Evans Hughes (other topics)

More...

Biography:

Charles Evans Hughes was born and raised in New York. He was educated by his parents but matriculated at Madison College (now Colgate) when he was fourteen. He completed his undergraduate education at Brown. Hughes taught briefly before entering Columbia Law School. He scored an amazing 99 1/2 on his bar exam at the age of 22. He practiced law in New York for 20 years, though he did hold an appointment at Cornell Law School for a few years in that period.

Hughes earned national recognition for his investigation into illegal rate- making and fraud in the insurance industry. With an endorsement from Theodore Roosevelt, Hughes ran successfully for New York governor, defeating Democrat William Randolph Hearst in 1906. In 1910, Hughes accepted nomination to the High Court from President Taft. Six years later, Hughes resigned to run against Woodrow Wilson for the presidency as the nominee of the Republican and Progressive Parties. He lost by a mere 23 electoral votes.

After a brief stint in private practice, Hughes was called to politics again, this time as secretary of state for Warren G. Harding. Hughes continued in this role during the presidency of Calvin Coolidge. Hughes's nomination to be chief justice met with opposition from Democrats who viewed Hughes as too closely aligned with corporate America. Their opposition was insufficient to deny Hughes the center chair, however.

Hughes authored twice as many constitutional opinions as any other member of his Court. His opinions, in the view of one commentator, were concise and admirable, placing Hughes in the pantheon of great justices.

Hughes had remarkable intellectual and social gifts that made him a superb leader and administrator. He had a photographic memory that few, if any, of his colleagues could match. Yet he was generous, kind, and forebearing in an institution where egos generally come in only one size: extra large!

Personal Information

Born: Friday, April 11, 1862

Died: Friday, August 27, 1948

Childhood Location: New York

Childhood Surroundings: New York

Position: Associate Justice

Seat: 7

Nominated By: Taft

Commissioned on: Sunday, May 1, 1910

Sworn In: Sunday, October 9, 1910

Left Office: Friday, June 9, 1916

Reason For Leaving: Resigned

Home: New York

Position: Chief Justice

Seat: 1

Commissioned on: Wednesday, February 12, 1930

Sworn In: Sunday, February 23, 1930

Left Office: Sunday, June 29, 1941

Reason For Leaving: Retired

Length of Service: 30 years, 8 months, 20 days (5 years, 8 months, 0 days / 11 years, 4 months, 6 days)

Home: New York

source:

The Oyez Project, Justice Charles E. Hughes

available at: (http://oyez.org/justices/charles_e_hu...)