The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

Battle Cry of Freedom

AMERICAN CIVIL WAR

>

16. Military Series: BATTLE CRY... May 28th ~ June 3rd ~~ Chapters EIGHTEEN & NINETEEN (546 - 590); No Spoilers Please

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter Overview and Summary

Chapter Overview and SummaryChapter Eighteen: John Bull's Virginia Reel

In Liverpool, Confederates were able to build ships in the pro-southern community. The ships would be built there, then the guns would be added at a different port away from England. Due to the 1862 cotton famine, there was growing sympathy for the South. However, British radicals and a number of workers supported the North. The upper class tended to support the South, and two cabinet ministers, William Gladstone and John Russell, favored support for the Confederacy. However, Palmerston still did not want to recognize them. In France, the Confederate government was willing to help Napoleon III overthrow Benito Juarez in Mexico, but France was not willing to go too far.

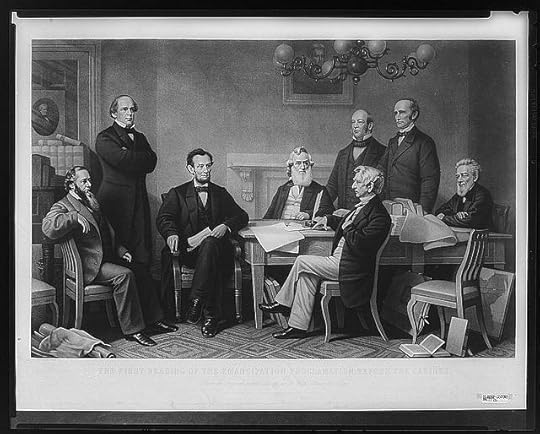

On January 1, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and it helped usher in black soldiers. The South reacted harshly, vowing to executive white officers and black soldiers. The Democrats fared well in the elections, because people were weary of the war, Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus, and Democrats successfully inflaming racist sentiment due to the proclamation. However, the Republicans still controlled Congress.

Chapter Nineteen: Three Rivers in Winter, 1862-1863

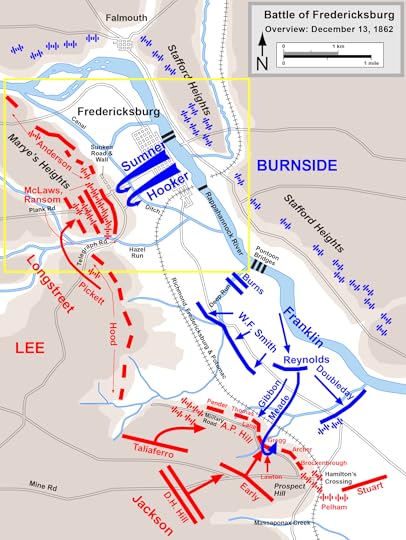

On the war-front, Lincoln tried to get McClellan to attack Lee. However, McClellan just resupplied and reorganized. On November 7, Lincoln replaced McClellan with General Burnside. Burnside moved on Richmond via Fredericksburg. He was slow in getting the pontoon bridges, giving Lee time to dig in. From December 11-12, the battle waged near town. It was a huge Union loss. Lincoln fired Burnside and put in General Hooker.

Out west, Davis gave Joseph Johnston command of the Department of the West, even though the general wanted to stay in the east. Grant tried to take Vicksburg, but the swamps around it stopped his army. Disease became rampant, and there was talk of Grant's incompetnance and drinking. Lincoln sent Charles Dana to look at the situation and Dana reported back that he approved of Grant.

Henry Hotze:

Henry Hotze:

Although he lived in Alabama for less than a decade, Henry Hotze (1834-1887) left an impressive record of literary, military, and diplomatic service to his adopted state and to the Confederacy. From 1855 to 1865, Hotze was an associate editor for the Mobile Register, served in the Confederate Army and as a Confederate diplomat, and edited a London-based newspaper that promoted the Confederate cause. His writings promoting a scientific hierarchy of race-based intelligence were used by white supremacists as a justification for slavery. A sometimes overlooked figure from the American Civil War, Hotze was perhaps the South's most effective propagandist abroad.

Henry Hotze was born in Zurich, Switzerland, on September 2, 1834, to Rudolph Hotze, a captain in the French Royal Service, and Sophie Esslinger. Little is known about his childhood other than that he received a very strong Jesuit education. Around 1850, Hotze emigrated to the United States and ended up in Mobile. On June 27, 1856, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen. Outgoing and well-educated, Hotze soon made contacts among Mobile's elites. One of his mentors was Josiah C. Nott, physician, scientist, and author, who promoted the study of race-based intelligence. Nott enlisted Hotze to translate Count Arthur de Gobineau's Essai sur L'inégalité des Races Humaines (Essay on the Inequality of Human Races), Josiah Clark Nott (1804-1873) was a medical doctor Josiah C. Nott to which Hotze added his own introduction of more than 100 pages. Hotze's version, entitled Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races (1856), was a detailed discussion of various cultures that purported to prove through science a hierarchy of racial intelligence among various groups of people based on skin color and continent of origin. Proponents of slavery used his finished product as a manifesto on the justification of slavery and subjugation. Hotze specifically adapted Gobineau's racial views to justify the unequal treatment of what he believed to be unequal races.

In Mobile, Hotze served in a number of municipal positions, including secretary of the Mobile Board of Harbor Commissioners and as the secretary to the Belgian mission from 1858 to 1859. He then worked as an associate editor at John Forsyth's Mobile Register. Hotze's tenure at the Register coincided with the presidential election of 1860 when he worked with Forsyth to support the candidacy of Stephen A. Douglas. After the Civil War began, Hotze entered the more public phase of his career. As a member of the Mobile Cadets, a military organization made up mostly of Mobile's affluent sons, Hotze was sent to Virginia as part of the Third Alabama Infantry Regiment. A journalist by profession, he wrote firsthand accounts of his brief time in the Confederate military, sending a series of letters back to the Mobile Register under the pseudonym "Cadet." While on active duty, John Forsyth Jr. (1812-1877) was a newspaperman and John Forsyth Jr.Hotze was never involved in any hostile action. One year later, Hotze, by then working for the Confederate State Department in London, published, in his own newspaper, a series of articles under the title "Three Months in the Confederate Army." Both accounts are primarily filled with the routine aspects of camp life near Lynchburg and Norfolk, Virginia. Although Hotze describes the hard work involved in setting up the camp, his accounts of the first few weeks of his tour focus on descriptions of a very lively social scene.

In the fall of 1861, the Confederate government sent Hotze on a special mission to Europe to purchase arms, but when he arrived in Great Britain, he came to believe that his time could be better spent on pro-Confederate diplomacy and propaganda. In November 1861 he successfully lobbied for an appointment as a "commercial agent" to London. Such an agent would normally be charged with procuring arms and supplies for the Confederate armies, but Hotze was actually sent to keep the Confederate government apprised of European public opinion and to present the Southern cause in the best possible light to the local reading public. Working in an anonymous fashion, Hotze arranged for an unsigned editorial to be inserted in the London Morning Post. In March 1862, Hotze used this newfound access to contribute a series of four letters to the Post. Writing under the pseudonym "Moderator," Hotze detailed the legality, necessity, practicality, and desirability of Southern independence and Europe's recognition of the Confederacy in a piece entitled "The Question of Recognition of the Confederate States."

By the end of April, Hotze had made the most important decision of his foreign tenure. He informed the Confederate government that he wanted to publish a newspaper devoted to the Confederate cause and used his journalist skills to edit a European-based Confederate newspaper, The Index, which first appeared on May 1, 1862. For the next three years, the paper was an effective means of presenting propaganda to an often sympathetic, yet in Hotze's opinion, sadly misinformed population. Although never exceeding a circulation of 2,250, the Index was read by many in the British government and by a sizeable number of Southern sympathizers in Europe. The weekly Index published accounts of Civil War battles that were surprisingly accurate given Hotze's position as a propagandist, as well as editorials pushing for European recognition of the Confederacy and, as the South neared defeat, an increasing amount of venomous racist propaganda. Although slavery was illegal in Britain, Hotze's racial diatribes struck a responsive chord among groups such as the Anthropological Society of London, a group that shared similar views. As the war ended, Hotze realized the Index could no longer stay afloat financially. He published the 172nd and final issue on August 12, 1865. Although it appeared four months after Lee's surrender, Hotze remained pro-Southern and defiant until the end.

With the suspension of his newspaper, Hotze quickly faded from public view. Very little is known of his final 20 years. Although he apparently maintained his U.S. citizenship, Hotze never returned to the United States. He obviously kept writing in some form because his obituary made mention that in his later years, he "received various decorations from foreign governments for services as a publicist." In 1868 he married Ruby Senac, a daughter of the Confederate paymaster in Europe. Hotze moved several times between London and Paris until, after a long period of illness, he died in Zug, Switzerland, on April 19, 1887.

(Source: http://encyclopediaofalabama.org/face...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Hotze

Lonnie A. Burnett

Lonnie A. Burnett

The British/French part of this chapter just shows you there were international dimensions to this war. I think we forget that at times.

The British/French part of this chapter just shows you there were international dimensions to this war. I think we forget that at times.

Emancipation Proclamation:

Emancipation Proclamation:

Whereas on the 22nd day of September, A.D. 1862, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

"That on the 1st day of January, A.D. 1863, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

"That the executive will on the 1st day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State or the people thereof shall on that day be in good faith represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such States shall have participated shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State and the people thereof are not then in rebellion against the United States."

Now, therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-In-Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for supressing said rebellion, do, on this 1st day of January, A.D. 1863, and in accordance with my purpose so to do, publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days from the first day above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof, respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana (except the parishes of St. Bernard, Palquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James, Ascension, Assumption, Terrebone, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the city of New Orleans), Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkeley, Accomac, Morthhampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Anne, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth), and which excepted parts are for the present left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States and parts of States are, and henceforward shall be, free; and that the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all case when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known that such persons of suitable condition will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

(Source: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h1...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emancipa...

http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/feat...

I am confused by this sentence: "Though the South did not actually do this, considerable evidence indicates that captured officers were sometimes "dealt with red-handed on the field or immediately thereafter," as Secretary of War Seddon suggested to General Kirby Smith in 1863." (p. 566)

I am confused by this sentence: "Though the South did not actually do this, considerable evidence indicates that captured officers were sometimes "dealt with red-handed on the field or immediately thereafter," as Secretary of War Seddon suggested to General Kirby Smith in 1863." (p. 566)So, if the South didn't do this, who did? Or is the author telling us about this "evidence", and at the same time that it is false evidence? Or is he merely saying that this was not official policy of the South? Strangely worded if that is the case.

Kristjan wrote: "I am confused by this sentence: "Though the South did not actually do this, considerable evidence indicates that captured officers were sometimes "dealt with red-handed on the field or immediately..."

Kristjan wrote: "I am confused by this sentence: "Though the South did not actually do this, considerable evidence indicates that captured officers were sometimes "dealt with red-handed on the field or immediately..."Unfortunately, McPherson does not cite the evidence.

This is how I read it: The Confederate Congress had a policy of sending captured Union officers to military courts. It seems that Confederate officers were supposed to do this, but the evidence seems to indicate they were administered justice right on the battle-field (shot) or maybe taken to state authorities.

What are your thoughts on the southern reaction to enlisting black soldiers?

What are your thoughts on the southern reaction to enlisting black soldiers? You really see how emotions and patriotism run raw during this war.

Battle of Fredericksburg:

Battle of Fredericksburg:

On November 14, Burnside, now in command of the Army of the Potomac, sent a corps to occupy the vicinity of Falmouth near Fredericksburg. The rest of the army soon followed. Lee reacted by entrenching his army on the heights behind the town. On December 11, Union engineers laid five pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock under fire. On the 12th, the Federal army crossed over, and on December 13, Burnside mounted a series of futile frontal assaults on Prospect Hill and Marye’s Heights that resulted in staggering casualties. Meade’s division, on the Union left flank, briefly penetrated Jackson’s line but was driven back by a counterattack. Union generals C. Feger Jackson and George Bayard, and Confederate generals Thomas R.R. Cobb and Maxey Gregg were killed. On December 15, Burnside called off the offensive and recrossed the river, ending the campaign. Burnside initiated a new offensive in January 1863, which quickly bogged down in the winter mud. The abortive “Mud March” and other failures led to Burnside’s replacement by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker in January 1863.

(Source: http://www.nps.gov/hps/abpp/battles/v...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_o...

http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/...

http://www.nps.gov/frsp/fredhist.htm

http://www.civilwarhome.com/fredrick.htm

This is an interesting quote:

This is an interesting quote:"The battle of Fredericksburg on December 13 once again pitted great valor in the Union ranks and mismanagement by their commanders against stout fighting and effective generalship on the Confederate side." (p. 571)

We are beginning to understand the importance of great generalship the Union did not have right now.

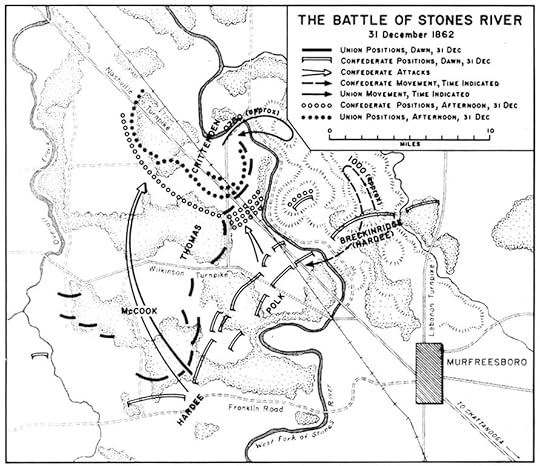

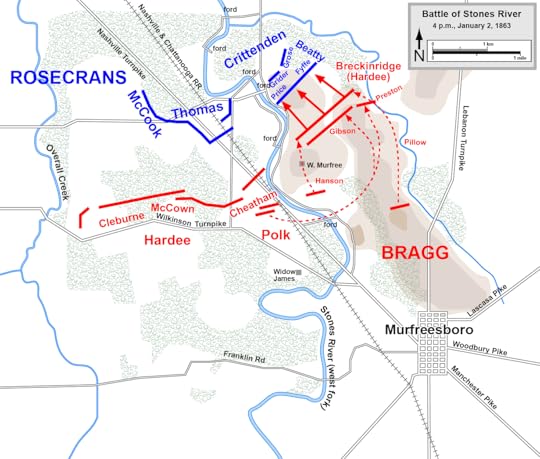

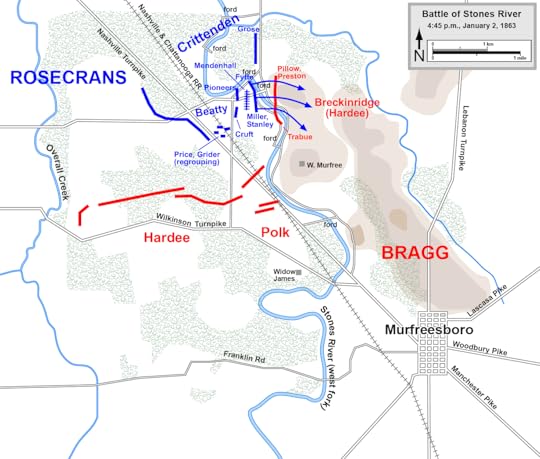

Battle of Murfreesboro/Stones River:

Battle of Murfreesboro/Stones River:

After Gen. Braxton Bragg’s defeat at Perryville, Kentucky, October 8, 1862, he and his Confederate Army of the Mississippi retreated, reorganized, and were redesignated as the Army of Tennessee. They then advanced to Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and prepared to go into winter quarters. Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans’s Union Army of the Cumberland followed Bragg from Kentucky to Nashville. Rosecrans left Nashville on December 26, with about 44,000 men, to defeat Bragg’s army of more than 37,000. He found Bragg’s army on December 29 and went into camp that night, within hearing distance of the Rebels. At dawn on the 31st, Bragg’s men attacked the Union right flank. The Confederates had driven the Union line back to the Nashville Pike by 10:00 am but there it held. Union reinforcements arrived from Rosecrans’s left in the late forenoon to bolster the stand, and before fighting stopped that day the Federals had established a new, strong line. On New Years Day, both armies marked time. Bragg surmised that Rosecrans would now withdraw, but the next morning he was still in position. In late afternoon, Bragg hurled a division at a Union division that, on January 1, had crossed Stones River and had taken up a strong position on the bluff east of the river. The Confederates drove most of the Federals back across McFadden’s Ford, but with the assistance of artillery, the Federals repulsed the attack, compelling the Rebels to retire to their original position. Bragg left the field on the January 4-5, retreating to Shelbyville and Tullahoma, Tennessee. Rosecrans did not pursue, but as the Confederates retired, he claimed the victory. Stones River boosted Union morale. The Confederates had been thrown back in the east, west, and in the Trans-Mississippi.

(Source: http://www.nps.gov/hps/abpp/battles/t...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_o...

http://www.nps.gov/stri/index.htm

http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/...

My great grandfather's older brother, Pal Mikkel Paulson, fought and won a medal for bravery at Stone's River along with the other Scandinavians in the 15th Wisconsin Volunteer Regiment under Col. Hans Christian Heg. He went on to fight at the Battle of Chickamauga but when the Union lost the troops were scattered. Pal was captured several months later, sent to Libby Prison in Richmond and died a few weeks prior to the end of the war.

My great grandfather's older brother, Pal Mikkel Paulson, fought and won a medal for bravery at Stone's River along with the other Scandinavians in the 15th Wisconsin Volunteer Regiment under Col. Hans Christian Heg. He went on to fight at the Battle of Chickamauga but when the Union lost the troops were scattered. Pal was captured several months later, sent to Libby Prison in Richmond and died a few weeks prior to the end of the war. Many of these men were Norwegian immigrants farming in Wisconsin and Iowa. Pal and his parents came to the US in 1849 when he was 9 years old - so he was 21 when he enlisted in 1861. Their farm was in NW Iowa.

Colonel Heg

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/15th_Wis...

Very interesting, Becky, thanks for sharing some family history! It is never a good experience to be a POW, especially during the Civil War.

Very interesting, Becky, thanks for sharing some family history! It is never a good experience to be a POW, especially during the Civil War.

You're welcome, but oops! They immigrated in 1852 (he was 9) so that made him 18 at the time of enlistment and deceased a 21. (Got confused with the immigration date of another branch of the family.)

You're welcome, but oops! They immigrated in 1852 (he was 9) so that made him 18 at the time of enlistment and deceased a 21. (Got confused with the immigration date of another branch of the family.)

Grant's drinking is interesting chapter in all of this. Grant really only needed 1 or 2 drinks to get drunk. Halleck heard about his exploits, and I forgot that Lincoln sent Dana to look into the matter. I would think this would create a lot of pressure.

Grant's drinking is interesting chapter in all of this. Grant really only needed 1 or 2 drinks to get drunk. Halleck heard about his exploits, and I forgot that Lincoln sent Dana to look into the matter. I would think this would create a lot of pressure.Do agree with the author about his discipline in not to drink making him a better general?

Bryan wrote: "Grant's drinking is interesting chapter in all of this. Grant really only needed 1 or 2 drinks to get drunk. Halleck heard about his exploits, and I forgot that Lincoln sent Dana to look into the..."

Bryan wrote: "Grant's drinking is interesting chapter in all of this. Grant really only needed 1 or 2 drinks to get drunk. Halleck heard about his exploits, and I forgot that Lincoln sent Dana to look into the..."I think that Grant's earlier difficulties, before the war, made him a more deliberate and modest man.

I think his handling of his drinking was indicative of his posture and that he was vunerable to alcohol and didn't seem to get drunk during the war, critical times anyway, shows his character and sense of responsibility.

When you ask "better general" - compared to many of his colleagues just being willing and enthusicatic to engage the enemy nade him a "better general" I think.

Books mentioned in this topic

Henry Hotze, Confederate Propagandist: Selected Writings on Revolution, Recognition, and Race (other topics)Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (other topics)

Authors mentioned in this topic

Lonnie A. Burnett (other topics)James M. McPherson (other topics)

Welcome all to the sixteenth week of the History Book Club's brand spanking new Military Series. We at the History Book Club are pretty excited about this offering and the many more which will follow. The first offering in the new MILITARY SERIES is a wonderful group selected book: Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era by James M. McPherson.

The week's reading assignment is:

Week Sixteen - May 28th - June 3rd -> Chapters EIGHTEEN & NINETEEN p. 546 - 590

We will open up a thread for each week's reading. Please make sure to post in the particular thread dedicated to those specific chapters and page numbers to avoid spoilers. We will also open up supplemental threads as we did for other books.

This book was officially kicked off on February 13th. We look forward to your participation. Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Powell's and other noted on line booksellers do have copies of the book and shipment can be expedited. The book can also be obtained easily at your local library, or on your Kindle/Nook. This weekly thread will be opened up either during the weekend before or on the first day of discussion.

There is no rush and we are thrilled to have you join us. It is never too late to get started and/or to post.

Welcome,

~Bryan

TO ALWAYS SEE ALL WEEKS' THREADS SELECT VIEW ALL

Battle Cry of Freedom The Civil War Era by James M. McPherson

REMEMBER NO SPOILERS ON THE WEEKLY NON SPOILER THREADS

Notes

It is always a tremendous help when you quote specifically from the book itself and reference the chapter and page numbers when responding. The text itself helps folks know what you are referencing and makes things clear.

Citations

If an author or book is mentioned other than the book and author being discussed, citations must be included according to our guidelines. Also, when citing other sources, please provide credit where credit is due and/or the link. There is no need to re-cite the author and the book we are discussing however. For citations, add always the book cover, the author's photo when available and always the author's link.

If you need help - here is a thread called the Mechanics of the Board which will show you how:

http://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/2...

Glossary

Remember there is a glossary thread where ancillary information is placed by the moderator. This is also a thread where additional information can be placed by the group members regarding the subject matter being discussed.

http://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/8...

Bibliography

There is a Bibliography where books cited in the text are posted with proper citations and reviews. We also post the books that the author may have used in his research or in his notes. Please also feel free to add to the Bibliography thread any related books, etc with proper citations or other books either non fiction or historical fiction that relate to the subject matter of the book itself. No self promotion, please.

http://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/8...