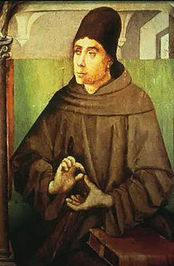

John Duns Scotus

Born

Duns, Berwickshire, Scotland

Died

October 23, 1308

Genre

|

Philosophical Writings

by

—

published

1961

—

7 editions

|

|

|

A Treatise on God as First Principle

—

published

1308

—

32 editions

|

|

|

Duns Scotus on the Will and Morality

by

—

published

1986

—

6 editions

|

|

|

John Duns Scotus: Four Questions on Mary

by

—

published

2000

—

2 editions

|

|

|

Early Oxford Lecture on Individuation

by |

|

|

On Being and Cognition: Ordinatio 1.3 (Medieval Philosophy: Texts and Studies

by |

|

|

Selected Writings on Ethics

by |

|

|

Concerning Metaphysics: Extracts

by |

|

|

God and Creatures: The Quodlibetal Questions

—

published

1975

—

7 editions

|

|

|

Scotus Vs. Ockham: A Medieval Dispute over Universals: Commentary

|

|

“If all men by nature desire to know, then they desire most of all the greatest knowledge of science. And he immediately indicates what the greatest science is, namely the science which is about those things that are most knowable. But there are two senses in which things are said to be maximally knowable: either because they are the first of all things known and without them nothing else can be known; or because they are what are known most certainly. In either way, however, this science is about the most knowable. Therefore, this most of all is a science and, consequently, most desirable.”

―

―

“…those who deny that some being is ‘contingent’ should be exposed to torments until they concede that it is possible for them not to be tormented.”

―

―

“Also, I say that although things other than God are actually contingent as regards their actual existence, this is not true with regard to potential existence. Wherefore, those things which are said to be contingent with reference to actual existence are necessary with respect to potential existence. Thus, though "Man exists" is contingent, "It is possible for man to exist" is necessary, because it does not include a contradiction as regards existence. For, for something other than God to be possible, then, is necessary. Being is divided into what must exist and what can but need not be. And just as necessity is of the very essence or constitution of what must be, so possibility is of the very essence of what can but need not be. Therefore, let the former argument be couched in terms of possible being and the propositions will become necessary. Thus: It is possible that something other than God exist which neither exists of itself (for then it would not be possible being) nor exists by reason of nothing. Therefore, it can exist by reason of another. Either this other can both exist and act in virtue of itself and not in virtue of another, or it cannot do so. If it can, then it can be the first cause, and if it can exist, it does exist—as was proved above. If it cannot [both be and act independently of every other thing] and there is no infinite regress, then at some point we end up [with a first cause].”

― A Treatise on God as First Principle

― A Treatise on God as First Principle