Ten Books That Inspired Mortal Engines

I’ve written elsewhere about some of the more obvious influences on Mortal Engines – Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings, and other SF and fantasy works which I’d loved in my childhood and early teens and was starting to look back on nostalgically in my mid-to-late twenties when I started working on what became M.E. But I was reading a lot of other books at that time too. I’m sure I picked up influences from all over the place, but the ones which stick in my mind are these:

Victorian Inventions by Leonard de Vries

Packed with careful steel-engravings of whacky flying machines and hat-mounted cameras, I think this is the book which first made me start thinking that a world full of implausible machines might make a rewarding setting.

Bleak House by Charles Dickens

I’d read this in my teens and I read it again around the time I started work on Mortal Engines: it had the sort of scale I was after, and it’s a portrait of a city – Dickens’s heightened and grotesque vision London, with its rich and poor, its slums and taverns, and the glacially slow workings of the Kafkaesque Court of Chancery. I don’t know if you can still trace much of its influence in Mortal Engines, but I guess Valentine’s dark secret is a kind of echo, as is Hester’s name (the heroine of Bleak House is called Esther). And Bleak House alternates between chapters told in the first person past tense and chapters told in the third person present tense, which probably encouraged me to insert some present tense passages in Mortal Engines – I really wish I hadn’t now, but it’s a conceit which lends Bleak House a weirdly cinematic power.

Take Back Plenty by Colin Greenland

I’d very much lost interest in Science Fiction around the middle ’80s, but for some reason in about 1990 I picked up this book, and it reminded me why I’d liked the genre in the first place. Set in a solar system where humans rub shoulders with all sorts of alien races, it plunges a space-freighter captain named Tabitha Jute into a murky mystery which leads her to Mars, Venus, and into the bowels of Plenty – an alien space artefact. Reading it made me want to write science fiction again.

(Oddly, when I went back to it recently it was still brilliant, but not nearly as much fun as I remembered – all the characters are having horrible lives. Perhaps I was confusing my memories of it with another rollicking space opera, Babylon 5, which I used to watch at the end of a hard day’s illustrating a few years later.)

Vainglory by Geraldine McCaughrean

I probably wouldn’t have set out to write a novel at all if I hadn’t come across Geraldine’s novel Fire’s Astonishment – I talked about it here. One day, when I walked up the hill on my afternoon break from drawing, the box of books outside the second-hand furniture shop at Fiveways yielded up a battered copy of another of her novels, Vainglory. A family saga set in mediaeval France, it’s long been out-of-print – I suspect because it’s too strange and playful to sell as a straight-up historical romance, and too much of a rip-roaring story to count as lit-fic. But it’s brilliant, and I’ve gone back to it many times. The section where one of the main characters tries to win favour with the king by building a road through an impassable bog is one of the best literary descriptions of a futile task I’ve ever read, but it may be bettered a few pages later when he sets off to find a unicorn for the royal menagerie (and ends up after many annoyances capturing a very grumpy rhino).

Elsewhere, it’s enormously moving, partly because of Geraldine’s unnerving habit of killing off characters just when you’re getting to know them and assume they’re going to be the hero or heroine. After two or three have bitten the dust you realise that you have no idea where this story is going, or whether anyone will be left alive at the end of it. It was an exhilarating experience, and when people complain about their favourite characters in Mortal Engines getting bumped off, I blame Geraldine McCaughrean.

The King Must Die by Mary Renault

I’d read this book (and its sequel, The Bull From The Sea) when I was about twelve (when a lot of it must have sailed straight over my head). It’s a brilliant novel about the Greek hero Theseus which gets rid of the mythic, supernatural elements and tries to find plausible explanations for the Minotaur, the Centaurs, etc. It’s real influence on my stuff probably shows up in Here Lies Arthur, a novel about the British hero Arthur which gets rid of the mythic, supernatural elements and tries to find plausible explanations for the Lady of the Lake, the Holy Grail, etc. But rereading it in the ’90s did reawaken an interest in Greek myths, and I think led among other things to the idea that people in the Mortal Engines world worship a whole pantheon of gods.

The Aubrey/Maturin novels by Patrick O’Brian

I’ve written elsewhere about these fantastic books, which look to the casual observer like Nelsonic tales of nautical derring-do but are so much more (including, apart from anything else, being some of the most unexpectedly funny books I’ve ever read)*. There’s not much more to add here, but I was reading them in the late ’90s (Mr O’Brian would obligingly publish a new one each September, just in time for me to take with me on holiday to Dartmoor). Did they influence Mortal Engines? Well, they’re basically about people steering huge complicated machines around the world in pursuit of other huge complicated machines which they must attempt to capture or avoid being captured by, so it’s anybody’s guess.

*Unfortunately WordPress has done horrid and apparently unfixable things to the formatting of a lot of my older posts, but I think it’s just about readable.

The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes

In the early versions of Mortal Engines the weird science available to the Guild of Engineers wasn’t quite so weird (apart from, you know, a mobile city). The McGuffin that Valentine had rediscovered was an atomic weapon, or at least the recipe for building one. I didn’t know much about atom bombs, so I went out and bought a copy of this, which I believe is still the definitive history of the Manhattan Project. Fairly quickly I worked out that if London had the Bomb it wouldn’t need to move, and that the story would work better if the Engineers were building a weapon which was fixed to the city but had limited reach, so that London had to manouevre itself into range. So I doubt there are any traces of this book in the final version, but I’m glad I read it; it explains both the science and the history with great clarity, and is one of those non-fiction books which really are as compelling as any novel.

Millennium by Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

As I worked away at early drafts of Mortal Engines the Twentieth Century was fizzling out, and historians and their publishers were starting to look back at its highs and lows. Felipe Fernandez-Armesto went one better with this massive book which takes in the second two thousand years of the Christian Era. It was one of the first properly global history books I’d read, giving as much weight to China, South America and Africa as to the more familiar (to me) European stuff, and it probably nudged me towards the idea that Mortal Engines wasn’t just about mobile cities, but a world with many different cultures and civilizations.

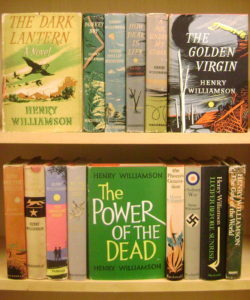

A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight by Henry Williamson

Photo: Keel Row Books

Not one novel but a ten volume sequence of them, heavily based on the author’s own life. Henry Williamson is remembered now mostly for Tarka the Otter, but he had a long and prolific career after that and in these books he looks back over his whole life (or at least over that of Philip Maddison, a thinly-veiled version of himself). A number of the volumes deal with his time in the First World War, and manage to convey the reality of it better than any other account I’ve read: the boredom and squalor of life in the trenches, the alienating spells of leave back home in London, and the experience of battle – which, seen from Williamson’s perspective, are extraordinary maelstroms of noise and confusion in which time seems to speed up or slow to a crawl. Loads of small details found their way into the grain of Mortal Engines.

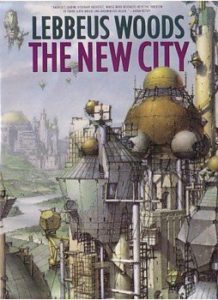

The New City by Lebbeus Woods

An outsize book of drawings by the US architect which I found in the arty remaindered bookshop in Kensington Gardens on one of my mooches around Brighton. The text is a word-gumbo of architecture and physics jargon which went straight over my head, but the pictures – beautifully rendered in soft graphite and what looks like pencil crayon – conjure up a bizarre townscape which is still one of my favourite sci-fi worlds. There wasn’t much room for these hi-tech, organic looking structures in the rickety world of Mortal Engines, but I kept The New City on my desk while I was writing the final drafts to remind me that despite all the airships and sword fights I was dealing with the far future, not the past. The ‘black glass claw’ where the Engineers have their HQ definitely sounds like a Lebbeus Woods design.

newest »

newest »

Thank you so much for this inspiring and illuminating post! As a lover of Mortal Engines (not to mention Zen and his trains), it encourages me to be daring and completely myself in my writing - a real gift from the most individual of writers.

Thank you so much for this inspiring and illuminating post! As a lover of Mortal Engines (not to mention Zen and his trains), it encourages me to be daring and completely myself in my writing - a real gift from the most individual of writers.