The History Book Club discussion

SUPREME COURT OF THE U.S.

>

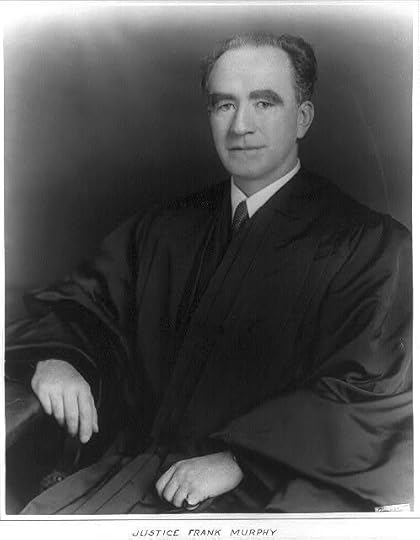

#80 - ASSOCIATE JUSTICE FRANK MURPHY

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

William Francis "Frank" Murphy (April 13, 1890 – July 19, 1949) was a politician and jurist from Michigan. He served as First Assistant U.S. District Attorney, Eastern Michigan District (1920–23), Recorder's Court Judge, Detroit (1923–30). Mayor of Detroit (1930–33), the last Governor-General of the Philippines (1933–35), U.S. High Commissioner of the Philippines (1935–36), the 35th Governor of Michigan (1937–39), United States Attorney General (1939–40), and United States Supreme Court Associate Justice (1940–49).

William Francis "Frank" Murphy (April 13, 1890 – July 19, 1949) was a politician and jurist from Michigan. He served as First Assistant U.S. District Attorney, Eastern Michigan District (1920–23), Recorder's Court Judge, Detroit (1923–30). Mayor of Detroit (1930–33), the last Governor-General of the Philippines (1933–35), U.S. High Commissioner of the Philippines (1935–36), the 35th Governor of Michigan (1937–39), United States Attorney General (1939–40), and United States Supreme Court Associate Justice (1940–49).Early life

Murphy was born in Harbor Beach, Michigan, then known as "Sand Beach," in 1890. His Irish parents, John T. Murphy and Mary Brennan, raised him as a devout Catholic. He followed in his father’s footsteps by becoming a lawyer. He attended the University of Michigan Law School, and graduated with a BA in 1912 and LLB in 1914. He was a member of the Sigma Chi Fraternity and the senior society Michigamua. Murphy was stricken with diphtheria in the winter of 1911 but was allowed to begin his course in the Law Department from which he received his LL.B. degree in 1914. He performed graduate work at Lincoln's Inn in London and Trinity College, Dublin, which was said to be formative for his judicial philosophy. He developed a need to decide cases based on his more holistic notions of justice, eschewing technical legal arguments. As one commentator quipped of his later Supreme Court service, he "tempered justice with Murphy."

He served in the U.S. Army during World War I, achieving the rank of Captain with the occupation Army in Germany before leaving the service in 1919.

Murphy opened a private law office in Detroit and soon became the Chief Assistant United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan. He opened the first civil rights section of a U.S. Attorney's office.

He taught at the University of Detroit for five years.

Murphy served as a Judge in the Detroit Recorder's Court from 1923 to 1930, and made many administrative reforms in the operations of the court.

While on Recorder's Court, he established a reputation as a trial judge. He was a presiding judge in the famous murder trials of Dr. Ossian Sweet and his brother, Henry Sweet, in 1925 and 1926. Clarence Darrow, then one of the most prominent trial lawyers in the country, was lead counsel for the defense. After an initial mistrial of all of the black defendants, Henry Sweet —who admitted that he fired the weapon which killed a member of the mob surrounding Dr. Sweet's home and was retried separately —was acquitted by an all-white jury on grounds of the right of self-defense. The prosecution then elected to not prosecute any of the remaining defendants. Murphy's rulings were material to the outcome of the case.

U.S. Attorney Eastern District of Michigan (1919–1922)

Murphy was appointed and took the oath of office as first assistant United States attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan on August 9, 1919. He was one of three assistant attorneys in the office.

When Murphy began his career as a federal attorney, the workload of the attorney's office was increasing at a rapid rate, mainly because of the number of prosecutions resulting from the enforcement of national prohibition. The government's excellent record in winning convictions in the Eastern District was partially due to Murphy's record of winning all but one of the cases that he prosecuted. Murphy practiced law privately to a limited extent while he was still a federal attorney. He resigned his position as a United States attorney on March 1, 1922. Murphy had several offers to join private practices but decided to go it alone and formed a partnership with Edward G. Kemp.

Recorder's Court (1923–1930)

He ran unsuccessfully as a Democrat for the United States Congress in 1920, when national and state Republicans swept Michigan. He drew upon his legal reputation and growing political connections to win a seat on the Recorder's Court, Detroit's criminal court. In 1923, Murphy was elected judge of the Recorder's Court on a non-partisan ticket by one of the largest majorities ever cast for a judge in Detroit. Murphy took office on January 1, 1924, and served seven years during the Prohibition Era.

Mayor of Detroit (1930–1933)

In 1930, Murphy ran as a Democrat and was elected Mayor of Detroit. He served from 1930 to 1933, during the first years of the Great Depression. He presided over an epidemic of urban unemployment, a crisis in which 100,000 people were unemployed in the summer of 1931. He named an unemployment committee of private citizens from businesses, churches, and labor and social service organizations to identify all residents who were unemployed and not receiving welfare benefits. The Mayor’s Unemployment Committee raised funds for its relief effort and worked to distribute food and clothing to the needy, and a Legal Aid Subcommittee volunteered to assist with the legal problems of needy clients. In 1933, Murphy convened in Detroit and organized the first convention of the United States Conference of Mayors. They met and conferred with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Murphy was elected its first president.

Murphy was an early and enthusiastic supporter of Roosevelt and the New Deal, helping Roosevelt to become the first Democratic presidential candidate to win the state of Michigan.

Melvin G. Holli rated Murphy an exemplary mayor and highly effective leader.

Governor-General of the Philippines (1933–1935)

By 1933, after Murphy’s second mayoral term, the reward of a big government job was waiting. Roosevelt appointed Murphy as Governor-General of the Philippines. Murphy demonstrated sympathy for Filipino masses, especially for the land-hungry and oppressed tenant farmers, and emphasized the need for social justice.

High Commissioner to the Philippines (1935–1936)

When his position as Governor-General was abolished in 1935, he stayed on as United States High Commissioner until 1936. That year he served as a delegate from the Philippine Islands to the Democratic National Convention.

High Commissioner to the Philippines was the title of the personal representative of the President of the United States to the Commonwealth of the Philippines during the period 1935–1946. The office was created by the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934, which provided for a period of transition from direct American rule to the complete independence of the islands on July 4, 1946.

Governor of Michigan (1937–1939)

Murphy was elected the 35th Governor of Michigan on November 3, 1936, defeating Republican incumbent Frank Fitzgerald, and served one two-year term. During his two years in office, an unemployment compensation system was instituted and mental health programs were improved.

The United Automobile Workers engaged in an historic sit-down strike at the General Motors' Flint plant. The Flint Sit-Down Strike was a turning point in national collective bargaining and labor policy. After 27 people were injured in a battle between the workers and the police, including 13 strikers with gunshot wounds, Murphy sent the National Guard to protect the workers. The governor didn't follow a court's order requesting him to expel the strikers, and refused to order the Guard's troops to suppress the strike.

Murphy successfully mediated an agreement and end to the confrontation; G.M. recognized the U.A.W. as bargaining agent under the newly adopted National Labor Relations Act. This recognition had a significant effect upon the growth of organized labor unions. In the next year the UAW saw its membership grow from 30,000 to 500,000 members. As later noted by the British Broadcasting System, this strike was "the strike heard round the world."

In 1938, Murphy was defeated by his predecessor, Fitzgerald, who became the only governor from Michigan to succeed and precede the same person.

Attorney General of the United States (1939–1940)

In 1939, Roosevelt appointed Murphy the 56th Attorney General of the United States. Murphy established a Civil Liberties Section in the Criminal Division of the United States Department of Justice. The section was designed to centralize enforcement responsibility for the Bill of Rights and civil rights statutes.

Supreme Court

Supreme CourtAfter a year as Attorney General, on January 4, 1940, Murphy was nominated by Roosevelt to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, filling a seat vacated by Pierce Butler. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on January 16 and was sworn in on January 18. The timing of the appointment put Murphy on the cusp of the Charles Evans Hughes[24] and the Harlan Fiske Stone courts. Upon the death of Chief Justice Stone, Murphy served in the court led by Frederick Moore Vinson, who was confirmed in 1946.

Murphy took an expansive view of individual liberties, and the limitations on government he found in the Bill of Rights.

Murphy authored 199 opinions: 131 majority, 68 in dissent.

Opinions differ about him and his jurisprudential philosophy. He has been acclaimed as a legal scholar and a champion of the common man. Justice Felix Frankfurter disparagingly nicknamed Murphy "the Saint", criticizing his decisions as being rooted more in passion than reason. It has been said he was "Neither legal scholar nor craftsman" who was criticized "for relying on heart over head, results over legal reasoning, clerks over hard work, and emotional solos over team play."

Murphy's support of African-Americans, aliens, criminals, dissenters, Jehovah's Witnesses, Native Americans, women, workers, and other outsiders evoked a pun: “tempering justice with Murphy.” As he wrote in Falbo v. United States (1944), “The law knows no finer hour than when it cuts through formal concepts and transitory emotions to protect unpopular citizens against discrimination and persecution.”

According to Frankfurter, Murphy was part of the more liberal "Axis" of justices on the Court, along with Justices Rutledge, Douglas, and Black; the group would for years oppose Frankfurter's judicially-restrained ideology. Douglas, Murphy, and then Rutledge were the first justices to agree with Hugo Black's notion that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporated the Bill of Rights protection into it; this view would later become law.

Murphy is perhaps most well known for his vehement dissent from the court's ruling in Korematsu v. United States, which upheld the constitutionality of the government's internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. Murphy sharply criticized the majority ruling as "legalization of racism."

This was the first time that the word "racism" found its way into the lexicon of words used in Supreme Court opinion (he used it twice in a concurring opinion in Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co. 323 U.S. 192 (1944) issued that same day). He would use that word in five separate opinions. However the word "racism" disappeared with Murphy and from the court for almost two decades, not reappearing until the landmark decision of Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)[33][34] which struck down as unconstitutional the Virginia anti-miscegenation statute. See also Jim Crow laws.

Though Murphy was serving on the Supreme Court during World War II, he still longed to be part of the war effort. Consequently, during recesses of the Court, he served in Fort Benning, Georgia as an infantry officer.

On January 30, 1944, almost exactly one year before Allied liberation of the Auschwitz death camp on January 27, 1945, Justice Murphy unveiled the formation of the National Committee Against Nazi Persecution and Extermination of the Jews. Serving as committee chair, he stated it was created to combat Nazi propaganda "breeding the germs of hatred against Jews." The announcement was made on the 11th anniversary of Adolf Hitler becoming Chancellor of Germany. The eleven committee members included U.S. Vice President Henry Wallace, 1940 Republican presidential candidate Wendell Wilkie and Henry St. George Tucker, Presiding Bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church.

He acted as chairman of the National Committee against Nazi Persecution and Extermination of the Jews and of the Philippine War Relief Committee. The first committee was established in early 1944 to promote rescue of European Jews, and to combat antisemitism in the United States.

Personal life

Murphy was a confirmed bachelor, leading to speculation about his personal life. Speculation has been recorded about the sexual orientation of a few justices who were lifelong bachelors but no unambiguous evidence exists proving that they were gay. Perhaps the greatest body of circumstantial evidence surrounds Justice Murphy, who was dogged by "[r]umors of homosexuality [...] all his adult life".

For more than 40 years, Edward G. Kemp was Frank Murphy's devoted, trusted companion. Like Murphy, Kemp was a lifelong bachelor. From college until Murphy's death, the pair found creative ways to work and live together. [...] When Murphy appeared to have the better future in politics, Kemp stepped into a supportive, secondary role.

As well as Murphy's close relationship with Kemp, Murphy's biographer, historian Sidney Fine, found in Murphy's personal papers a letter that "if the words mean what they say, refers to a homosexual encounter some years earlier between Murphy and the writer." However, the letter's veracity cannot be confirmed and a review of all the evidence led Fine to conclude that he "could not stick his neck out and say [Murphy] was gay".

Death and legacy

Murphy died at fifty-nine of coronary thrombosis during his sleep at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. Over 10,000 people attended his funeral in Detroit. He was engaged to be married in August to Joan Cuddihy.

His remains are interred at Our Lady of Lake Huron Cemetery of Harbor Beach, Michigan. The Frank Murphy Hall of Justice was home to Detroit's Recorder's Court and now houses part of Michigan's Third Judicial Circuit Court. There is a plaque in his honor on the first floor, which is recognized as a Michigan Legal Milestone.

Outside the Hall of Justice is Carl Milles's statue "The Hand of God". This rendition was cast in honor of Murphy and financed by the United Automobile Workers. It features a nude figure emerging from the left hand of God. Although commissioned in 1949 and completed by 1953, the work, partly because of the male nudity involved, was kept in storage for a decade and a half. The work was chosen in tribute to Murphy by Walter P. Reuther and Ira W. Jayne. It was placed on a pedestal in 1970 with the help of sculptor Marshall Fredericks, who was a Milles student.

Murphy's personal and official files are archived at the Bentley Historical Library of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and are open for research. This also includes an oral history project about Murphy. His correspondence and other official documents are deposited in libraries around the country.

In memory of Murphy, one of three University of Michigan Law School alumni to become a U.S. Supreme Court justice, Washington D.C.-based attorney John H. Pickering, who was a law clerk for Murphy, donated a large sum of money to the law school as a remembrance, establishing the Frank Murphy Seminar Room.

Murphy was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Law degree by the University of Michigan in 1939.

The University of Detroit has a Frank Murphy Honor Society.

The Sweet Trials: Malice Aforethought is a play written by Arthur Beer, based on the trials of Ossian and Henry Sweet, and derived from Kevin Boyle's Arc of Justice.

The Detroit Public Schools named Frank Murphy Elementary in his honor

source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Mu...

book mentioned:

by Kevin Boyle

by Kevin Boyleauthor mentioned: Arthur Beer(no photo)

Korematsu was a horrendous decision. Good for Murphy for dissenting from it. Murphy isn't prominent in this book

Korematsu was a horrendous decision. Good for Murphy for dissenting from it. Murphy isn't prominent in this book

Noah Feldman but he is part of the court that is the focus of the book.

Noah Feldman but he is part of the court that is the focus of the book.

Korematsu was horrendous indeed. I have not read Scorpions: The Battles and Triumphs of FDR's Great Supreme Court Justices yet but it is on my list.

Korematsu was horrendous indeed. I have not read Scorpions: The Battles and Triumphs of FDR's Great Supreme Court Justices yet but it is on my list.I have read Arc of Justice: A Saga of Race, Civil Rights, and Murder in the Jazz Age and it was disturbing and enlightening.

It is one thing to read these opinions and quite another to get the story behind the case.

Kevin Boyle

Kevin Boyle

Noah Feldman

Noah Feldman

Double Agent: The First Hero of World War II and How the FBI Outwitted and Destroyed a Nazi Spy Ring

Double Agent: The First Hero of World War II and How the FBI Outwitted and Destroyed a Nazi Spy Ring by Peter Duffy (no photo)

by Peter Duffy (no photo)Synopsis:

The never-before-told tale of the German-American who spearheaded a covert mission to infiltrate New York's Nazi underground in the days leading up to World War II; the most successful counterespionage operation in US history.

From the time Adolf Hitler came into power in 1933, German spies were active in New York. In 1937, a German national living in Queens stole the blueprints for the country's most precious secret, the Norden Bombsight, delivering them to the German military two years before World War II started in Europe and four years before the US joined the fight. When the FBI uncovered a ring of Nazi spies in the city, President Franklin Roosevelt formally declared J. Edgar Hoover as America's spymaster with responsibility for overseeing all investigations.

As war began in Europe in 1939, a naturalized German-American was recruited by the Nazis to set up a radio transmitter and collect messages from spies active in the city to send back to Nazi spymasters in Hamburg. This German-American, William G. Sebold, approached the FBI and became the first double agent in the Bureau's history, the center of a sixteen-month investigation that led to the arrest of a colorful cast of thirty-three enemy agents, among them a South African adventurer with an exotic accent and a monocle and a Jewish femme fatale, Lilly Stein, who escaped Nazi Vienna by offering to seduce US military men into whispering secrets into her ear.

A riveting, meticulously researched, and fast-moving story, Double Agent details the largest and most important espionage bust in American history.

Frank Murphy: The New Deal Years

Frank Murphy: The New Deal Years by Sidney Fine (no photo)

by Sidney Fine (no photo)Synopsis:

Achieving national recognition as mayor of Detroit during the Depression and eventually becoming the foremost civil libertarian on the Supreme Court, Frank Murphy was one of America's most significant public figures from the 1920s to the late '40s. In this second volume of the monumental biography of Murphy, Sidney Fine focuses on the critical New Deal years when Murphy was the chief American official in the Philippines and the governor of Michigan during the great labor upheaval of 1937.

In keeping with his intention to illuminate both the life of Murphy and the times in which he lived, Fine examines not only the character of the Murphy regime in the Philippines but also the achievements and shortcomings of American domination in that country. The second half of the book is devoted to the years of Murphy's governorship, which Fine scrutinizes more closely than any previous historian. As governor, Murphy mediated the General Motors sit-down strike and played a crucial role in the absorption of organized labor into the American system. Fine also details Murphy's efforts to cope with the 1937-38 recession, delineating in the process the changing nature of federalism during that time.

The first historian to make full use of the relevant documentation, Fine has not only created a compelling portrait of an enlightened politician and administrator, he has also considerably increased our understanding of the New Deal Years.

The Era, 1947-1957: When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World

The Era, 1947-1957: When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World by Roger Kahn (no photo)

by Roger Kahn (no photo)Synopsis:

Celebrated sports writer Roger Kahn casts his gaze on the golden age of baseball, an unforgettable time when the game thrived as America's unrivaled national sport. The Era begins in 1947 with Jackie Robinson changing major league baseball forever by taking the field for the Dodgers. Dazzling, momentous events characterize the decade that followed-Robinson's amazing accomplishments; the explosion on the national scene of such soon-to-be legends as Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, Bobby Thomson, Duke Snider, and Yogi Berra; Casey Stengel's crafty managing; the emergence of televised games; and the stunning success of the Yankees as they play in nine out of eleven World Series. The Era concludes with the relocation of the Dodgers from Brooklyn to Los Angeles, a move that shook the sport to its very roots.

message 11:

by

Lorna, Assisting Moderator (T) - SCOTUS - Civil Rights

(last edited Jun 14, 2017 11:17AM)

(new)

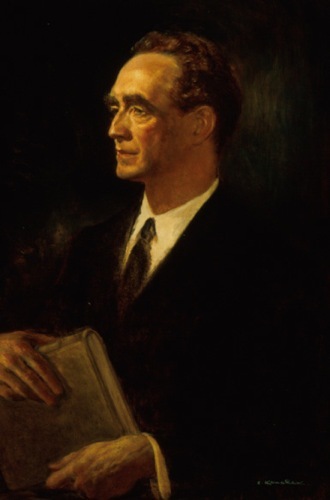

Frank Murphy

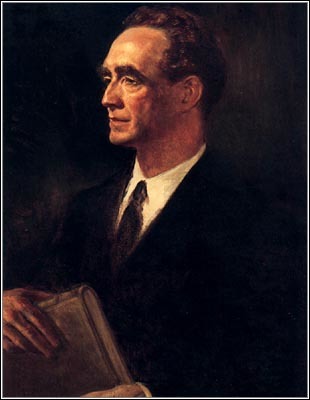

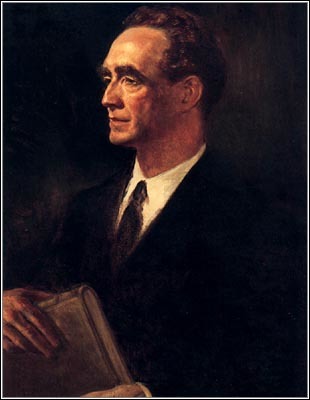

Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court February 5, 1940 - July 19, 1949

The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States (Artist: Elek Kanarek)

Frank Murphy held diverse positions before his elevation to the Court. He was mayor of Detroit from 1930 to 1933, governor general of the Philippines from 1933 to 1935, governor of Michigan from 1937 to 1939, and United States attorney general from 1939-40. While attorney general, Murphy established the first civil rights unit in the Justice Department. Murphy longed to be part of the war effort while on the bench. During Court recesses, he served as an infantry officer in Fort Benning, Georgia.

Murphy was a strong liberal who had the most impact through his concurring and dissenting opinions.

Other:

Justice Frank Murphy: 'Champion of First Amendment Freedoms'

By DAVID L. HUDSON, JR. November 26, 2001

When legal commentators speak of First Amendment greats on the U.S. Supreme Court, they often mention Oliver Wendell Holmes and Louis Brandeis, the so-called “Fathers of the First Amendment” who contributed greatly to the development of free-expression jurisprudence with their seminal opinions in the 1910s and 1920s. Holmes crafted the clear-and-present-danger test and wrote about the marketplace-of-ideas justification for free speech with his “the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.” Brandeis articulated the fundamental First Amendment principle of counterspeech when he wrote that the preferred remedy to harmful speech is “more speech, not enforced silence.”

Many mention Hugo Black, who was famous for carrying a copy of the Constitution in his pocket and noting that “no law” in the First Amendment really meant no law. In his opinion in the Pentagon Papers case of New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), Black opined that “the press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government” and that “only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government.”

Still others speak of William J. Brennan, whose 34 years on the Court included a remarkable turnabout on obscenity law and the authoring of the seminal free-press, libel-law decision of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), in which he wrote about the “profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be robust, uninhibited and wide-open.” Today, many laud Justice Anthony Kennedy for his vigilant protection of First Amendment interests. For example, Kennedy believes that content-based restrictions on political speech are per se unconstitutional. He explained in Republican Party of Minnesota v. White (2002) that “content-based speech restrictions that do not fall within any traditional exception should be invalidated without inquiry into narrow tailoring or compelling government interests.”

Yet, there is another justice who deserves mention with all these First Amendment judicial giants. Though he served less than a decade on the high court from 1940 to 1949, Justice Frank Murphy distinguished himself for his passionate defense of individual liberties. He wrote the Court’s opinion in Thornhill v. Alabama (1940), finding that labor picketing was entitled to First Amendment protection. “Free discussion concerning the conditions in industry and the causes of labor disputes appears to us indispensable to the effective and intelligent use of the processes of popular government to shape the destiny of modern industrial society,” Murphy wrote.

Murphy repeatedly voiced his belief that religious freedom was entitled to great constitutional protection, and he showed concern over the plight of Jehovah’s Witnesses, who were often persecuted for their religious beliefs and expression. In his concurring opinion in Martin v. City of Struthers (1943), he wrote: “I believe that nothing enjoys a higher estate in our society than the right given by the First and Fourteenth Amendments freely to practice and proclaim one’s religious convictions.” The next year, he dissented in the Court’s decision in Prince v. Massachusetts (1944), in which the majority convicted a Jehovah Witness woman for allowing children to sell religious magazines on the street. Murphy explained that “Religious freedom is too sacred a right to be restricted or prohibited in any degree without convincing proof that a legitimate interest of the state is in grave danger.”

Read the remainder of the article at: http://www.newseuminstitute.org/2001/...

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

Source(s): Oyez, Newseum Institute

Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court February 5, 1940 - July 19, 1949

The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States (Artist: Elek Kanarek)

Frank Murphy held diverse positions before his elevation to the Court. He was mayor of Detroit from 1930 to 1933, governor general of the Philippines from 1933 to 1935, governor of Michigan from 1937 to 1939, and United States attorney general from 1939-40. While attorney general, Murphy established the first civil rights unit in the Justice Department. Murphy longed to be part of the war effort while on the bench. During Court recesses, he served as an infantry officer in Fort Benning, Georgia.

Murphy was a strong liberal who had the most impact through his concurring and dissenting opinions.

Other:

Justice Frank Murphy: 'Champion of First Amendment Freedoms'

By DAVID L. HUDSON, JR. November 26, 2001

When legal commentators speak of First Amendment greats on the U.S. Supreme Court, they often mention Oliver Wendell Holmes and Louis Brandeis, the so-called “Fathers of the First Amendment” who contributed greatly to the development of free-expression jurisprudence with their seminal opinions in the 1910s and 1920s. Holmes crafted the clear-and-present-danger test and wrote about the marketplace-of-ideas justification for free speech with his “the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.” Brandeis articulated the fundamental First Amendment principle of counterspeech when he wrote that the preferred remedy to harmful speech is “more speech, not enforced silence.”

Many mention Hugo Black, who was famous for carrying a copy of the Constitution in his pocket and noting that “no law” in the First Amendment really meant no law. In his opinion in the Pentagon Papers case of New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), Black opined that “the press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government” and that “only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government.”

Still others speak of William J. Brennan, whose 34 years on the Court included a remarkable turnabout on obscenity law and the authoring of the seminal free-press, libel-law decision of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), in which he wrote about the “profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be robust, uninhibited and wide-open.” Today, many laud Justice Anthony Kennedy for his vigilant protection of First Amendment interests. For example, Kennedy believes that content-based restrictions on political speech are per se unconstitutional. He explained in Republican Party of Minnesota v. White (2002) that “content-based speech restrictions that do not fall within any traditional exception should be invalidated without inquiry into narrow tailoring or compelling government interests.”

Yet, there is another justice who deserves mention with all these First Amendment judicial giants. Though he served less than a decade on the high court from 1940 to 1949, Justice Frank Murphy distinguished himself for his passionate defense of individual liberties. He wrote the Court’s opinion in Thornhill v. Alabama (1940), finding that labor picketing was entitled to First Amendment protection. “Free discussion concerning the conditions in industry and the causes of labor disputes appears to us indispensable to the effective and intelligent use of the processes of popular government to shape the destiny of modern industrial society,” Murphy wrote.

Murphy repeatedly voiced his belief that religious freedom was entitled to great constitutional protection, and he showed concern over the plight of Jehovah’s Witnesses, who were often persecuted for their religious beliefs and expression. In his concurring opinion in Martin v. City of Struthers (1943), he wrote: “I believe that nothing enjoys a higher estate in our society than the right given by the First and Fourteenth Amendments freely to practice and proclaim one’s religious convictions.” The next year, he dissented in the Court’s decision in Prince v. Massachusetts (1944), in which the majority convicted a Jehovah Witness woman for allowing children to sell religious magazines on the street. Murphy explained that “Religious freedom is too sacred a right to be restricted or prohibited in any degree without convincing proof that a legitimate interest of the state is in grave danger.”

Read the remainder of the article at: http://www.newseuminstitute.org/2001/...

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

by Sidney Fine (no photo)Source(s): Oyez, Newseum Institute

Justice of the Day - FRANK MURPHY

By JLGARZON1 April 13, 2015

Justice Frank Murphy

Today’s Justice of the Day is: FRANK MURPHY. Justice Murphy was born on this day, April 13, in 1890.

Justice Murphy was born in Sand Beach, Michigan, the state from which he would be appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States. He earned an A.B. from the University of Michigan in 1912, and graduated from the University of Michigan Law School with an LL.B. in 1914.

Immediately upon graduation from law school, Justice Murphy launched his career in private practice in Detroit, Michigan, where he would work from then to 1917 and 1922 to 1923. During the five year-long break in his work as a private attorney, he was a United States Army First Lieutenant (from 1917 to 1919), Chief Assistant United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan (from 1919 to 1922), and a candidate for the United States House of Representatives from his home state (in 1920). In 1922 Justice Murphy began working as a Professor of Law at the University of Detroit, where he world work continuously for the next half-decade. The year after beginning his professorship, he became a Judge of the Detroit Recorder’s Court, and remained there until 1930, the year he began a three year-long term as the Mayor of Detroit. Justice Murphy left the mayor’s office and subsequently worked as Governor General and High Commissioner of the Philippine Islands (today called the Philippines) for three years (beginning in 1933), before starting a year-long stint as Governor of Michigan in 1937. In 1939 he took office as Attorney General of the United States, a position he would hold until his elevation to the SCUS.

Justice Murphy was nominated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on January 4, 1940, to a seat vacated by Justice Pierce Butler. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on January 16, and received his commission on January 18. Justice Murphy took the Judicial Oath to officially join the SCUS on February 5, and served on the Hughes, Stone, and Vinson Courts. His service was terminated on July 19, 1949, due to his death.

Justice Murphy is one of the least well-known Members of the SCUS who served during the mid-20th century. He was an unabashed liberal in his time, even founding the Department of Justice’s first civil rights unit during his tenure as Attorney General. Justice Murphy dissented in one of the modern SCUS’s most erroneously-decided cases, Korematsu v. United States (1944), wherein the majority upheld the internment of Japanese Americans on the grounds that the government must be given (seemingly limitless) leeway during times of national emergency.

Link to article: https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2015...

Other:

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

Source: The Daily Kos

By JLGARZON1 April 13, 2015

Justice Frank Murphy

Today’s Justice of the Day is: FRANK MURPHY. Justice Murphy was born on this day, April 13, in 1890.

Justice Murphy was born in Sand Beach, Michigan, the state from which he would be appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States. He earned an A.B. from the University of Michigan in 1912, and graduated from the University of Michigan Law School with an LL.B. in 1914.

Immediately upon graduation from law school, Justice Murphy launched his career in private practice in Detroit, Michigan, where he would work from then to 1917 and 1922 to 1923. During the five year-long break in his work as a private attorney, he was a United States Army First Lieutenant (from 1917 to 1919), Chief Assistant United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan (from 1919 to 1922), and a candidate for the United States House of Representatives from his home state (in 1920). In 1922 Justice Murphy began working as a Professor of Law at the University of Detroit, where he world work continuously for the next half-decade. The year after beginning his professorship, he became a Judge of the Detroit Recorder’s Court, and remained there until 1930, the year he began a three year-long term as the Mayor of Detroit. Justice Murphy left the mayor’s office and subsequently worked as Governor General and High Commissioner of the Philippine Islands (today called the Philippines) for three years (beginning in 1933), before starting a year-long stint as Governor of Michigan in 1937. In 1939 he took office as Attorney General of the United States, a position he would hold until his elevation to the SCUS.

Justice Murphy was nominated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on January 4, 1940, to a seat vacated by Justice Pierce Butler. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on January 16, and received his commission on January 18. Justice Murphy took the Judicial Oath to officially join the SCUS on February 5, and served on the Hughes, Stone, and Vinson Courts. His service was terminated on July 19, 1949, due to his death.

Justice Murphy is one of the least well-known Members of the SCUS who served during the mid-20th century. He was an unabashed liberal in his time, even founding the Department of Justice’s first civil rights unit during his tenure as Attorney General. Justice Murphy dissented in one of the modern SCUS’s most erroneously-decided cases, Korematsu v. United States (1944), wherein the majority upheld the internment of Japanese Americans on the grounds that the government must be given (seemingly limitless) leeway during times of national emergency.

Link to article: https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2015...

Other:

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

by Sidney Fine (no photo) by Sidney Fine (no photo)

by Sidney Fine (no photo)Source: The Daily Kos

Frank W. Murphy, 1940-1949

FRANK W. MURPHY was born on April 13, 1890, in Harbor Beach, Michigan. He was graduated from the University of Michigan in 1912 and University Law School in 1914. After his admission to the bar in 1914, Murphy clerked with a Detroit law firm for three years. In World War I, he served with the American forces in Europe and remained abroad after the War to pursue graduate studies in London and Dublin. In 1919, Murphy became Chief Assistant Attorney General for the Eastern District of Michigan, and from 1920 to 1923 he was engaged in private law practice. From 1923 to 1930, Murphy served on the Recorder’s Court of Detroit. He was elected Mayor of Detroit in 1930 and served for three years. President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Murphy Governor General of the Philippines in 1933. When the Philippines achieved independence in 1935, Murphy was named United States High Commissioner. After his return to the United States in 1936, Murphy was elected Governor of Michigan and served for two years. President Roosevelt appointed him Attorney General of the United States in 1939. One year later, on January 18, 1940, President Roosevelt nominated Murphy to the Supreme Court of the United States. The Senate confirmed the appointment on February 5, 1940. Murphy served on the Supreme Court for nine years. He died on July 19, 1949, at the age of fifty-nine.

Link: http://www.supremecourthistory.org/ti...

Other:

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

Source: The Supreme Court Historical Society

FRANK W. MURPHY was born on April 13, 1890, in Harbor Beach, Michigan. He was graduated from the University of Michigan in 1912 and University Law School in 1914. After his admission to the bar in 1914, Murphy clerked with a Detroit law firm for three years. In World War I, he served with the American forces in Europe and remained abroad after the War to pursue graduate studies in London and Dublin. In 1919, Murphy became Chief Assistant Attorney General for the Eastern District of Michigan, and from 1920 to 1923 he was engaged in private law practice. From 1923 to 1930, Murphy served on the Recorder’s Court of Detroit. He was elected Mayor of Detroit in 1930 and served for three years. President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Murphy Governor General of the Philippines in 1933. When the Philippines achieved independence in 1935, Murphy was named United States High Commissioner. After his return to the United States in 1936, Murphy was elected Governor of Michigan and served for two years. President Roosevelt appointed him Attorney General of the United States in 1939. One year later, on January 18, 1940, President Roosevelt nominated Murphy to the Supreme Court of the United States. The Senate confirmed the appointment on February 5, 1940. Murphy served on the Supreme Court for nine years. He died on July 19, 1949, at the age of fifty-nine.

Link: http://www.supremecourthistory.org/ti...

Other:

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

by Sidney Fine (no photo)Source: The Supreme Court Historical Society

Bentley wrote: "You know here is one Associate Justice who I am not as much familiar with."

Bentley, you are not alone as Justice Murphy is one of least known jurists. However, he was one of the dissenting opinions in one of the Supreme Court’s most erroneously-decided cases, Korematsu v. United States (1944), wherein the majority upheld the internment of Japanese Americans during times of national emergency.

Bentley, you are not alone as Justice Murphy is one of least known jurists. However, he was one of the dissenting opinions in one of the Supreme Court’s most erroneously-decided cases, Korematsu v. United States (1944), wherein the majority upheld the internment of Japanese Americans during times of national emergency.

Very good Lorna - thankfully I am not alone. And I think he was on the right side although he might have felt alone at the time.

The Dissenter

When the Supreme Court ruled in 1944 that Japanese internment during WWII was legal, Justice Frank Murphy’s dissent was a ringing voice amid a hostile cacophony. Through his archived papers at the Bentley, we take a look at the ways in which Murphy was a man ahead of his time—and what made him willing to take a stand against legalized prejudice.

By ROBERT HAVEY

Fred Korematsu was arrested on May 30, 1942, on the streets of San Leandro, California, for the crime of being of Japanese descent. Korematsu, born in Oakland, California, was in violation of Civilian Exclusion Order No. 34, which demanded every person of Japanese ancestry in “Military Area No. 1” (essentially all of California within 100 miles of the Pacific Ocean) report to “assembly centers” where they would be relocated to internment camps for the duration of the war. While he was imprisoned, lawyers from the ACLU asked Korematsu if he would be willing to be the test case in their legal fight against Japanese internment. Korematsu agreed.

The case found its way to the Supreme Court in 1944 where, in a 6-3 decision, it was ruled that Korematsu’s imprisonment was constitutional. The majority opinion written by Justice Hugo Black emphasized it was “military urgency” that justified internment, not racial prejudice. The nation was at war with the Japanese Empire and the forced removal of Japanese Americans was “a military imperative.”

The decision in Korematsu v. United States has been a stain on the reputation of the Supreme Court ever since. It’s considered by many contemporary justices as part of the court’s “anticanon” decisions like Dred Scott v. Sandford (former slaves could not be citizens), and Plessy v. Ferguson (separate but equal), where the court emphatically ruled on the wrong side of history. Forty-four years after the Korematsu case, President Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, formally apologizing to Japanese Americans for their treatment in WWII and paying restitution to each person held in an internment camp.

Perhaps the only redeeming aspect to the legacy of Korematsu was the fiery dissent written by Justice Frank Murphy. Murphy rejected Justice Black’s rational of military necessity, saying internment of Japanese citizens “falls into the ugly abyss of racism.” Murphy points out that in the report given to the court by Lt. General John L. DeWitt in support of the internment program, DeWitt refers to those of Japanese descent as “subversive” and says they belong to an “enemy race.” Murphy’s argument concludes:

"I dissent, therefore, from this legalization of racism. Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life. It is unattractive in any setting, but it is utterly revolting among a free people who have embraced the principles set forth in the Constitution of the United States. All residents of this nation are kin in some way by blood or culture to a foreign land. Yet they are primarily and necessarily a part of the new and distinct civilization of the United States. They must, accordingly, be treated at all times as the heirs of the American experiment, and as entitled to all the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution.”

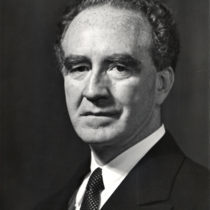

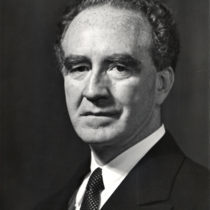

Frank Murphy giving a speech circa 1936. HS9506

Murphy’s dissent was a principled stand for individual rights at a time when the United States was panicked at the idea of a Japanese invasion in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor. His blunt condemnation of racism was unheard of at the time. In fact, Murphy was the first to use the word “racism” in a Supreme Court decision—a word that wouldn’t be used by another Justice until 1966. While Murphy’s Korematsu opinion now seems singularly ahead of its time, many of Murphy’s contemporaries saw it as another zealous stand by the court’s “crusader.” To them, according to biographer Sidney Fine, Murphy was a “humanitarian” rather than a principled jurist, who put “heart over head” when rendering verdicts, having “little respect for the traditional role of the court.”

Was Murphy a judicial visionary or a soft-hearted dilettante? The Frank Murphy papers at the Bentley chronicle each part of his life as a lawyer, soldier, politician, and judge, all of which led to his historic Korematsu dissent.

Link to remainder of the article: https://bentley.umich.edu/news-events...

More:

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

Source: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

When the Supreme Court ruled in 1944 that Japanese internment during WWII was legal, Justice Frank Murphy’s dissent was a ringing voice amid a hostile cacophony. Through his archived papers at the Bentley, we take a look at the ways in which Murphy was a man ahead of his time—and what made him willing to take a stand against legalized prejudice.

By ROBERT HAVEY

Fred Korematsu was arrested on May 30, 1942, on the streets of San Leandro, California, for the crime of being of Japanese descent. Korematsu, born in Oakland, California, was in violation of Civilian Exclusion Order No. 34, which demanded every person of Japanese ancestry in “Military Area No. 1” (essentially all of California within 100 miles of the Pacific Ocean) report to “assembly centers” where they would be relocated to internment camps for the duration of the war. While he was imprisoned, lawyers from the ACLU asked Korematsu if he would be willing to be the test case in their legal fight against Japanese internment. Korematsu agreed.

The case found its way to the Supreme Court in 1944 where, in a 6-3 decision, it was ruled that Korematsu’s imprisonment was constitutional. The majority opinion written by Justice Hugo Black emphasized it was “military urgency” that justified internment, not racial prejudice. The nation was at war with the Japanese Empire and the forced removal of Japanese Americans was “a military imperative.”

The decision in Korematsu v. United States has been a stain on the reputation of the Supreme Court ever since. It’s considered by many contemporary justices as part of the court’s “anticanon” decisions like Dred Scott v. Sandford (former slaves could not be citizens), and Plessy v. Ferguson (separate but equal), where the court emphatically ruled on the wrong side of history. Forty-four years after the Korematsu case, President Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, formally apologizing to Japanese Americans for their treatment in WWII and paying restitution to each person held in an internment camp.

Perhaps the only redeeming aspect to the legacy of Korematsu was the fiery dissent written by Justice Frank Murphy. Murphy rejected Justice Black’s rational of military necessity, saying internment of Japanese citizens “falls into the ugly abyss of racism.” Murphy points out that in the report given to the court by Lt. General John L. DeWitt in support of the internment program, DeWitt refers to those of Japanese descent as “subversive” and says they belong to an “enemy race.” Murphy’s argument concludes:

"I dissent, therefore, from this legalization of racism. Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life. It is unattractive in any setting, but it is utterly revolting among a free people who have embraced the principles set forth in the Constitution of the United States. All residents of this nation are kin in some way by blood or culture to a foreign land. Yet they are primarily and necessarily a part of the new and distinct civilization of the United States. They must, accordingly, be treated at all times as the heirs of the American experiment, and as entitled to all the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution.”

Frank Murphy giving a speech circa 1936. HS9506

Murphy’s dissent was a principled stand for individual rights at a time when the United States was panicked at the idea of a Japanese invasion in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor. His blunt condemnation of racism was unheard of at the time. In fact, Murphy was the first to use the word “racism” in a Supreme Court decision—a word that wouldn’t be used by another Justice until 1966. While Murphy’s Korematsu opinion now seems singularly ahead of its time, many of Murphy’s contemporaries saw it as another zealous stand by the court’s “crusader.” To them, according to biographer Sidney Fine, Murphy was a “humanitarian” rather than a principled jurist, who put “heart over head” when rendering verdicts, having “little respect for the traditional role of the court.”

Was Murphy a judicial visionary or a soft-hearted dilettante? The Frank Murphy papers at the Bentley chronicle each part of his life as a lawyer, soldier, politician, and judge, all of which led to his historic Korematsu dissent.

Link to remainder of the article: https://bentley.umich.edu/news-events...

More:

by Sidney Fine (no photo)

by Sidney Fine (no photo)Source: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Thank you very much Lorna for the very interesting add. Today was an eventful day for the Supreme Court.

Books mentioned in this topic

Frank Murphy: The New Deal Years (other topics)Frank Murphy: The New Deal Years (other topics)

Frank Murphy: The Detroit Years (other topics)

Frank Murphy: The Washington Years (other topics)

Frank Murphy: The Detroit Years (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Sidney Fine (other topics)Sidney Fine (other topics)

Sidney Fine (other topics)

Sidney Fine (other topics)

Roger Kahn (other topics)

More...

Biography

Frank Murphy held diverse positions before his elevation to the Court. He was mayor of Detroit from 1930 to 1933, governor general of the Philippines from 1933 to 1935, governor of Michigan from 1937 to 1939, and United States attorney general from 1939-40. While attorney general, Murphy established the first civil rights unit in the Justice Department. Murphy longed to be part of the war effort while on the bench. During Court recesses, he served as an infantry officer in Fort Benning, Georgia.

Murphy was a strong liberal who had the most impact through his concurring and dissenting opinions.

Personal Information

Born Sunday, April 13, 1890

Died Tuesday, July 19, 1949

Childhood Location Michigan

Childhood Surroundings Michigan

Position Associate Justice

Seat 11

Nominated By Roosevelt, F.

Commissioned on Thursday, January 18, 1940

Sworn In Monday, February 5, 1940

Left Office Tuesday, July 19, 1949

Reason For Leaving Death

Length of Service 9 years, 5 months, 14 days

Home Michigan

source: http://www.oyez.org/justices/frank_mu...