The History Book Club discussion

SUPREME COURT OF THE U.S.

>

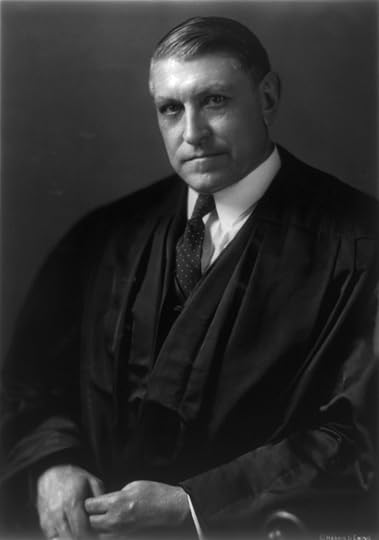

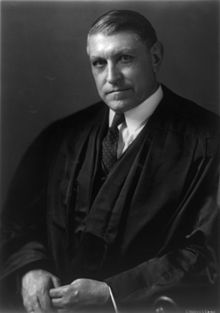

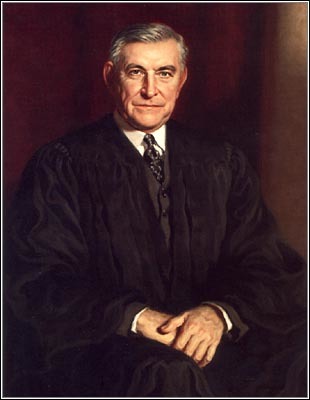

#74 - ASSOCIATE JUSTICE OWEN ROBERTS

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Owen Josephus Roberts (May 2, 1875 – May 17, 1955) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court for fifteen years. He also led two Roberts Commissions, the first that investigated the attack on Pearl Harbor and the second that focused on works of cultural value during the war. At the time of World War II, he was the only Republican appointed Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States and one of only three justices to vote against Franklin D. Roosevelt's orders for Japanese American internment camps in Korematsu v. United States.

Owen Josephus Roberts (May 2, 1875 – May 17, 1955) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court for fifteen years. He also led two Roberts Commissions, the first that investigated the attack on Pearl Harbor and the second that focused on works of cultural value during the war. At the time of World War II, he was the only Republican appointed Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States and one of only three justices to vote against Franklin D. Roosevelt's orders for Japanese American internment camps in Korematsu v. United States.Early life and career

Roberts was born in Philadelphia and attended Germantown Academy and the University of Pennsylvania, where he was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa Society and was the editor of The Daily Pennsylvanian. He completed his bachelor's degree in 1895 and went on to graduate at the top of his class from University of Pennsylvania Law School in 1898.

He first gained notice as an assistant district attorney in Philadelphia. He was appointed by President Calvin Coolidge to investigate oil reserve scandals, known as the Teapot Dome scandal. This led to the prosecution and conviction of Albert B. Fall, the former Secretary of the Interior, for bribe-taking.

Supreme Court

Roberts was appointed to the Supreme Court by Herbert Hoover after Hoover's nomination of John J. Parker was defeated by the Senate.

On the Court, Roberts was a swing vote between those, led by Justices Louis Brandeis, Benjamin Cardozo, and Harlan Fiske Stone, as well as Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, who would allow a broader interpretation of the Commerce Clause to allow Congress to pass New Deal legislation that would provide for a more active federal role in the national economy, and the Four Horsemen (Justices James Clark McReynolds, Pierce Butler, George Sutherland, and Willis Van Devanter) who favored a narrower interpretation of the Commerce Clause and believed that the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause protected a strong "liberty of contract." In 1936's United States v. Butler, Roberts sided with the Four Horsemen and wrote an opinion striking down the Agricultural Adjustment Act as beyond Congress's taxing and spending powers.

"Switch in Time that Saved the Nine"

Roberts switched his position on the constitutionality of the New Deal in late 1936, and the Supreme Court handed down West Coast Hotel v. Parrish in 1937, upholding the constitutionality of minimum wage laws. Subsequently, the Court would vote to uphold all New Deal programs. Since President Roosevelt's plan to appoint several new justices as part of his "Court-packing" plan of 1937 coincided with the Court's favorable decision in Parrish, many people called Roberts's vote in that case the "switch in time that saved nine," although Roberts's vote in Parrish occurred several months before announcement of the Court-packing plan. While Roberts is often accused of inconsistency in his jurisprudential stance towards the New Deal, legal scholars note that he had previously argued for a broad interpretation of government power in the 1934 case of Nebbia v. New York, and so his later vote in Parrish was not a complete reversal. Roberts, however, had sided with the four conservative justices in finding a similar state minimum wage in New York unconstitutional in June 1936. Because the announcement of the Parrish decision took place in March 1937, one month after Roosevelt announced his plan to pack the court, it created speculation that Roberts had voted in favor of the Washington's state minimum wage law because he had succumbed to political pressure.

However, Chief Justice Charles Evan Hughes contended in his autobiographical notes that Roosevelt's attempt to pack the court "had not the slightest effect" on the court's ruling in the Parrish case and records showed that Roberts indicated his desire to uphold Washington state's minimum wage law two months prior to Roosevelt's court-packing announcement in December 1936. On December 19, 1936, two days after oral arguments ended for the Parrish case, Roberts voted in favor of Washington's state minimum wage law, but the Supreme Court was divided 4–4 because pro-New Deal Associate Justice Harlan Fiske Stone was absent due to an illness; Hughes contended that this long delay in the Parrish case's announcement led to false speculation that Roosevelt's court packing plan intimidated the court into ruling in favor of the New Deal. Roberts and Hughes both acknowledged that because of the overwhelming support that had been shown for the New Deal through Roosevelt's re-election in November of 1936, Hughes was able to persuade Roberts to no longer base his votes on his own political beliefs and side with him during future votes on New Deal related policies. In one of his notes from 1936, Hughes wrote that Roosevelt's re-election forced the court to depart from "its fortress in public opinion" and severely weakened its capability to base its rulings on personal or political beliefs.

Other rulings and Roberts Commissions

Roberts wrote the majority opinion in the landmark case of New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co., 303 U.S. 552 (1938), which safeguarded the right to boycott in the context of the struggle by African Americans against discriminatory hiring practices. He also wrote the majority opinion sustaining provisions of the second Agricultural Adjustment Act applied to the marketing of tobacco in Mulford v. Smith, 307 U.S. 38 (1939).

Roberts was appointed by Roosevelt to head the commission investigating the attack on Pearl Harbor; his report was published in 1942 and was highly critical of the United States Military. Journalist John T. Flynn wrote at the time that Roosevelt's appointment of Roberts: was a master stroke. What the public overlooked was that Roberts had been one of the most clamorous among those screaming for an open declaration of war. He had doffed his robes, taken to the platform in his frantic apprehensions and demanded that we immediately unite with Great Britain in a single nation. The Pearl Harbor incident had given him what he had been yelling for – America's entrance into the war. On the war issue he was one of the President's most impressive allies. Now he had his wish. He could be depended on not to cast any stain upon it in its infancy.

Perhaps influenced by his work on the Pearl Harbor commission, Roberts dissented from the Court's decision upholding internment of Japanese-Americans along the West Coast in 1944's Korematsu v. United States.

The second Roberts Commission was established in 1943 to consolidate earlier efforts on a national basis with the US Army to help protect Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives in war zones. The commission ran until 1946, when its activities were consolidated into the State Department

In his later years on the bench, Roberts was the only Justice on the Supreme Court not appointed (or in the case of Stone, who had become Chief Justice, promoted) by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roberts became frustrated with the willingness of the new justices to overturn precedent and with what he saw as their result-oriented liberalism as judges. Roberts dissented bitterly in the 1944 case of Smith v. Allwright, which in finding the white primary unconstitutional overruled an opinion Roberts himself had written nine years previously. It was in his dissent in that case that he coined the oft-quoted phrase that the frequent overruling of decisions "tends to bring adjudications of this tribunal into the same class as a restricted railroad ticket, good for this day and train only."

Retirement

Roberts retired from the Court the following year, in 1945; Roberts's relations with his colleagues had become so strained that fellow Justice Hugo Black refused to sign the customary letter acknowledging Roberts's service on his retirement. Other justices refused to sign a modified letter that would have been acceptable to Black, and in the end, no letter was ever sent.

Shortly after leaving the Court, Roberts reportedly burned all of his legal and judicial papers. As a result, there is no significant collection of Roberts' manuscript papers, as there is for most other modern Justices. Roberts did prepare a short memorandum discussing his alleged change of stance around the time of the court-packing effort, which he left in the hands of Justice Felix Frankfurter.

Later life

While in retirement Roberts, along with Robert P. Bass, convened the Dublin Declaration, a plan to change the U.N. General Assembly into a world legislature with "limited but definite and adequate power for the prevention of war."

Roberts served as the Dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School from 1948 to 1951.

He died at his Chester County, Pennsylvania, farm known as the Strickland-Roberts Homestead after a four-month illness. He was survived by his wife, Elizabeth Caldwell Rogers, and daughter, Elizabeth Hamilton.

Germantown Academy named its debate society after Owen J. Roberts in his honor. In addition, a school district near Pottstown, Pennsylvania, the Owen J. Roberts School District, was named after him.

In 1946, Roberts was the first layperson elected to serve as President of the House of Deputies for the General Convention of the Episcopal Church (United States). He served for one convention.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Owen_Rob...

Books by and about:

Books by and about:(no image) The Court and the Constitution by Owen J. Roberts (no photo)

(no image) The Owen J. Roberts Memorial Lectures, 1957-1974: Delivered Under the Auspices of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, Its Chapter of the Order by University of Pennsylvania (no photo)

Paths Out of Dixie: The Democratization of Authoritarian Enclaves in America's Deep South, 1944-1972

Paths Out of Dixie: The Democratization of Authoritarian Enclaves in America's Deep South, 1944-1972 by Robert Mickey(no photo)

by Robert Mickey(no photo)Synopsis:

The transformation of the American South--from authoritarian to democratic rule--is the most important political development since World War II. It has re-sorted voters into parties, remapped presidential elections, and helped polarize Congress. Most important, it is the final step in America's democratization. "Paths Out of Dixie" illuminates this sea change by analyzing the democratization experiences of Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina.

Robert Mickey argues that Southern states, from the 1890s until the early 1970s, constituted pockets of authoritarian rule trapped within and sustained by a federal democracy. These enclaves--devoted to cheap agricultural labor and white supremacy--were established by conservative Democrats to protect their careers and clients. From the abolition of the whites-only Democratic primary in 1944 until the national party reforms of the early 1970s, enclaves were battered and destroyed by a series of democratization pressures from inside and outside their borders.

Drawing on archival research, Mickey traces how Deep South rulers--dissimilar in their internal conflict and political institutions--varied in their responses to these challenges. Ultimately, enclaves differed in their degree of violence, incorporation of African Americans, and reconciliation of Democrats with the national party. These diverse paths generated political and economic legacies that continue to reverberate today.

Focusing on enclave rulers, their governance challenges, and the monumental achievements of their adversaries, "Paths Out of Dixie" shows how the struggles of the recent past have reshaped the South and, in so doing, America's political development.

Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Supreme Court

Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Supreme Court by

by

Artemus Ward, Christopher Brough (no photo), and Robert Arnold (no photo)

Artemus Ward, Christopher Brough (no photo), and Robert Arnold (no photo)Synopsis:

The US Supreme Court is an institution that operates almost totally behind closed doors. This book opens those doors by providing a comprehensive look at the justices, procedures, cases, and issues over the institution s more than 200-year history. The Court is a legal institution born from a highly politicized process. Modern justices time their departures to coincide with favorable administrations and the confirmation process has become a highly-charged political spectacle played out on television and in the national press.

Throughout its history, the Court has been at the center of the most important issues facing the nation: federalism, separation of powers, war, slavery, civil rights, and civil liberties. Through it all, the Court has generally, though not always, reflected the broad views of the American people as the justices decide the most vexing issues of the day. The Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Supreme Court covers its history through a chronology, an introductory essay, appendixes, and an extensive bibliography.

The dictionary section has over 700 cross-referenced entries on every justice, major case, issue, and process that comprises the Court s work. This book is an excellent access point for students, researchers, and anyone wanting to know more about the Supreme Court."

A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination

A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination by

by

Philip Shenon

Philip ShenonSynopsis:

A groundbreaking, explosive account of the Kennedy assassination that will rewrite the history of the 20th century's most controversial murder investigation

The questions have haunted our nation for half a century: Was the President killed by a single gunman? Was Lee Harvey Oswald part of a conspiracy? Did the Warren Commission discover the whole truth of what happened on November 22, 1963?

Philip Shenon, a veteran investigative journalist who spent most of his career at The New York Times, finally provides many of the answers. Though A Cruel and Shocking Act began as Shenon's attempt to write the first insider's history of the Warren Commission, it quickly became something much larger and more important when he discovered startling information that was withheld from the Warren Commission by the CIA, FBI and others in power in Washington. Shenon shows how the commission's ten-month investigation was doomed to fail because the man leading it – Chief Justice Earl Warren – was more committed to protecting the Kennedy family than getting to the full truth about what happened on that tragic day. A taut, page-turning narrative, Shenon's book features some of the most compelling figures of the twentieth century—Bobby Kennedy, Jackie Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, J. Edgar Hoover, Chief Justice Warren, CIA spymasters Allen Dulles and Richard Helms, as well as the CIA's treacherous "molehunter," James Jesus Angleton.

Based on hundreds of interviews and unprecedented access to the surviving commission staffers and many other key players, Philip Shenon's authoritative, scrupulously researched book will forever change the way we think about the Kennedy assassination and about the deeply flawed investigation that followed.

message 7:

by

Lorna, Assisting Moderator (T) - SCOTUS - Civil Rights

(last edited Jul 13, 2017 12:55PM)

(new)

Justice of the Day - Owen Roberts

By JLGARZON1 May 2, 2015

Justice Owen Roberts

Today’s Justice of the Day is: OWEN ROBERTS. Justice Roberts was born on this day, May 2, in 1875.

Justice Roberts was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the state where he would spend his entire academic and early legal career, and from which he would be appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States. He received his undergraduate education at the University of Pennsylvania, earning an A.B. in 1895, and attended its law school, receiving a J.D. in 1898.

Justice Roberts spent much of his early career in private practice (from 1898 to 1903) and teaching at his law school alma mater (from 1898 to 1913). He began a three year-long term as First Assistant District Attorney for Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania in 1903, immediately after which he started a career as a private attorney in his home town that would last until his appointment to the SCUS. Justice Roberts also served with the United States Department of Justice, first as Special Deputy Attorney General for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania (in 1918) and a Special United States Attorney to investigate the Teapot Dome Scandals (in 1924).

Justice Roberts was nominated by President Herbert Hoover on May 9, 1930, to a seat vacated by Justice Edward Terry Sanford. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on May 20, and received his commission that day. Justice Roberts took the Judicial Oath to officially join the SCUS on June 2, and served on the Hughes and Stone Courts. His service was terminated on July 31, 1945, due to his resignation.

Justice Roberts is most famous today for his role in the “switch in time that saved nine” in the West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish (1937) case, wherein his decision to switch from voting with the famous Four Horseman Justices (who opposed the New Deal and helped strike down huge parts of it) to voting against them helped sink President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ‘court-packing’ plan (which would have allowed him to appoint a huge number of new Justices to the SCUS, thus defeating the power of the conservative block that kept striking down his legislation). However, there is much dispute over the timeline of that event, with some asserting that Justice Roberts decided to support Washington’s minimum wage law (which was the primary issue in that controversy) before President Roosevelt had even announced the court-packing scheme. While often seen as the ‘swing vote’ (along the lines of Justice Anthony M. Kennedy today) early in his career, he later became a mostly dissenting voice as the SCUS moved to the left thanks to the addition of members like Justices Hugo Black and William O. Douglas. Perhaps his single most righteous dissent was in Korematsu v. United States (1944), which saw him oppose the majority of his colleagues, who had decided that the mass internment of Japanese Americans was constitutionally acceptable. There is no known relation between Justice Roberts and the current Chief Justice of the United States, John G. Roberts, Jr.

Other:

(no image) A Search for a Judicial Philosophy: Mr. Justice Roberts and the Constitutional Revolution of 1937 by Charles A. Leonard (no photo)

Source: Daily Kos

By JLGARZON1 May 2, 2015

Justice Owen Roberts

Today’s Justice of the Day is: OWEN ROBERTS. Justice Roberts was born on this day, May 2, in 1875.

Justice Roberts was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the state where he would spend his entire academic and early legal career, and from which he would be appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States. He received his undergraduate education at the University of Pennsylvania, earning an A.B. in 1895, and attended its law school, receiving a J.D. in 1898.

Justice Roberts spent much of his early career in private practice (from 1898 to 1903) and teaching at his law school alma mater (from 1898 to 1913). He began a three year-long term as First Assistant District Attorney for Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania in 1903, immediately after which he started a career as a private attorney in his home town that would last until his appointment to the SCUS. Justice Roberts also served with the United States Department of Justice, first as Special Deputy Attorney General for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania (in 1918) and a Special United States Attorney to investigate the Teapot Dome Scandals (in 1924).

Justice Roberts was nominated by President Herbert Hoover on May 9, 1930, to a seat vacated by Justice Edward Terry Sanford. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on May 20, and received his commission that day. Justice Roberts took the Judicial Oath to officially join the SCUS on June 2, and served on the Hughes and Stone Courts. His service was terminated on July 31, 1945, due to his resignation.

Justice Roberts is most famous today for his role in the “switch in time that saved nine” in the West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish (1937) case, wherein his decision to switch from voting with the famous Four Horseman Justices (who opposed the New Deal and helped strike down huge parts of it) to voting against them helped sink President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ‘court-packing’ plan (which would have allowed him to appoint a huge number of new Justices to the SCUS, thus defeating the power of the conservative block that kept striking down his legislation). However, there is much dispute over the timeline of that event, with some asserting that Justice Roberts decided to support Washington’s minimum wage law (which was the primary issue in that controversy) before President Roosevelt had even announced the court-packing scheme. While often seen as the ‘swing vote’ (along the lines of Justice Anthony M. Kennedy today) early in his career, he later became a mostly dissenting voice as the SCUS moved to the left thanks to the addition of members like Justices Hugo Black and William O. Douglas. Perhaps his single most righteous dissent was in Korematsu v. United States (1944), which saw him oppose the majority of his colleagues, who had decided that the mass internment of Japanese Americans was constitutionally acceptable. There is no known relation between Justice Roberts and the current Chief Justice of the United States, John G. Roberts, Jr.

Other:

(no image) A Search for a Judicial Philosophy: Mr. Justice Roberts and the Constitutional Revolution of 1937 by Charles A. Leonard (no photo)

Source: Daily Kos

Justice Owen Roberts

By DENNIS DRABELL November/ December 2009

Appointed to the Supreme Court for his crusading prosecution of the Teapot Dome Scandal in the 1920s, Owen Roberts went from New Deal obstructionist to enabler after Roosevelt threatened to “pack” the court. Was the alumnus and future Law School dean merely expedient, or a statesman who put country before consistency?

Before Rod Blagojevich or Jack Abramoff, before Nixon approved that second-rate burglary or Bill met Monica, there was the Teapot Dome scandal of the 1920s. Though far from the most lucrative or juiciest case of government wrongdoing, it does stand out in one respect: When it comes to building federal cases, few can match the standard set by Teapot Dome special prosecutor Owen J. Roberts C1895 L1898.

Roberts worked for five years to expose a group of crooks that included a member of the president’s cabinet, going so far as to pay his own expenses to keep the investigation alive when Congress was late in funding it. Largely on the strength of his Teapot Dome performance, Roberts was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1930.

A few years later, however, most Americans held a quite different view of Roberts: He was he one of the “nine old men” obstructing the New Deal. And then he made the “switch in time that saved nine”—a reference to Roberts’s perceived move toward the judicial Left when President Franklin D. Roosevelt, frustrated by the high court’s repeatedly thwarting his legislative efforts to combat the Great Depression, tried to “pack” it with new justices who could be counted on to vote his way. In joining with liberal colleagues to uphold the constitutionality of several New Deal programs—thus reducing the urgency to remodel the court—Roberts is assumed to have saluted the president.

It hasn’t been easy to square these contrasting images of Roberts as a vigorous, improvising prosecutor on the one hand, and a drifting, expediency-minded judge on the other. However, a pair of recent books, focusing on the Teapot Dome scandal and on the court-packing scheme, suggest that in both instances Roberts acted as a statesman. Although the famous switch was not a direct response to Roosevelt’s attempt to remake the court, it looks like a calculated maneuver by a man less concerned about his own consistency than about the future of his country.

Owen Josephus Roberts (1875-1955) was every inch a Penn man. As an undergraduate, the Germantown native was editor of The Daily Pennsylvanian—and that was only the most visible of his extracurricular activities. As Burt Solomon writes in his excellent account of the court-packing episode, FDR v. the Constitution, the list of Roberts’s undergraduate doings “fell a single word short of the longest yearbook caption for any member of his eighty-man class.” After graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1895, Roberts went over to the Law School, from which he graduated three years later with highest honors. For the better part of the next two decades he maintained a private practice; founded the Philadelphia firm now known as Montgomery, McCracken, Walker & Rhoads; and taught at the Law School, where he was made a full professor in 1907. Late in his career, after leaving the bench, he returned to serve as dean (for $1 a year) and taught a course in constitutional law. The school’s annual Owen J. Roberts Lecture perpetuates the bond between the man and the institution.

Read the remainder of the article at: http://www.upenn.edu/gazette/1109/fea...

Other:

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

Source: University of Pennsylvania Gazette

By DENNIS DRABELL November/ December 2009

Appointed to the Supreme Court for his crusading prosecution of the Teapot Dome Scandal in the 1920s, Owen Roberts went from New Deal obstructionist to enabler after Roosevelt threatened to “pack” the court. Was the alumnus and future Law School dean merely expedient, or a statesman who put country before consistency?

Before Rod Blagojevich or Jack Abramoff, before Nixon approved that second-rate burglary or Bill met Monica, there was the Teapot Dome scandal of the 1920s. Though far from the most lucrative or juiciest case of government wrongdoing, it does stand out in one respect: When it comes to building federal cases, few can match the standard set by Teapot Dome special prosecutor Owen J. Roberts C1895 L1898.

Roberts worked for five years to expose a group of crooks that included a member of the president’s cabinet, going so far as to pay his own expenses to keep the investigation alive when Congress was late in funding it. Largely on the strength of his Teapot Dome performance, Roberts was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1930.

A few years later, however, most Americans held a quite different view of Roberts: He was he one of the “nine old men” obstructing the New Deal. And then he made the “switch in time that saved nine”—a reference to Roberts’s perceived move toward the judicial Left when President Franklin D. Roosevelt, frustrated by the high court’s repeatedly thwarting his legislative efforts to combat the Great Depression, tried to “pack” it with new justices who could be counted on to vote his way. In joining with liberal colleagues to uphold the constitutionality of several New Deal programs—thus reducing the urgency to remodel the court—Roberts is assumed to have saluted the president.

It hasn’t been easy to square these contrasting images of Roberts as a vigorous, improvising prosecutor on the one hand, and a drifting, expediency-minded judge on the other. However, a pair of recent books, focusing on the Teapot Dome scandal and on the court-packing scheme, suggest that in both instances Roberts acted as a statesman. Although the famous switch was not a direct response to Roosevelt’s attempt to remake the court, it looks like a calculated maneuver by a man less concerned about his own consistency than about the future of his country.

Owen Josephus Roberts (1875-1955) was every inch a Penn man. As an undergraduate, the Germantown native was editor of The Daily Pennsylvanian—and that was only the most visible of his extracurricular activities. As Burt Solomon writes in his excellent account of the court-packing episode, FDR v. the Constitution, the list of Roberts’s undergraduate doings “fell a single word short of the longest yearbook caption for any member of his eighty-man class.” After graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1895, Roberts went over to the Law School, from which he graduated three years later with highest honors. For the better part of the next two decades he maintained a private practice; founded the Philadelphia firm now known as Montgomery, McCracken, Walker & Rhoads; and taught at the Law School, where he was made a full professor in 1907. Late in his career, after leaving the bench, he returned to serve as dean (for $1 a year) and taught a course in constitutional law. The school’s annual Owen J. Roberts Lecture perpetuates the bond between the man and the institution.

Read the remainder of the article at: http://www.upenn.edu/gazette/1109/fea...

Other:

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Burt Solomon (no photo)Source: University of Pennsylvania Gazette

I have to say he does not look too happy in his photo in message 7 - like he is looking at the photographer and saying can you please hurry and get this over with (smile0

JUSTICE OWEN ROBERTS’ MOST MEMORABLE FIRST AMENDMENT PASSAGES

Owen J. Roberts (Wikipedia)

By DAVID L. HUDSON, JR. May 14, 2018

Justice Owen J. Roberts (1875–1955) was a U.S. Supreme Court Justice perhaps best known for changing his view on the constitutionality of federal New Deal legislation that established the minimum wage. His vote switch is colloquially referred to as the “switch in time that saved nine.”

But, Owen Roberts also authored several significant First Amendment decisions during his time on the High Court. Below are five of his more memorable passages on subjects such as freedom of assembly, freedom of religion, political dissident speech, and commercial advertising.

“Wherever the title of streets and parks may rest, they have immemorially been held in trust for the use of the public and, time out of mind, have been used for purposes of assembly, communicating thoughts between citizens, and discussing public questions.”

Roberts wrote this line in Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization (1939), ruling that a group of citizens could convene in a public park in Jersey City for a political assembly. Roberts’ passage above forms the basis for the public forum doctrine – the idea that certain types of public property are open to citizen engagement and First Amendment activity.

“In the realm of religious faith, and in that of political belief, sharp differences arise. In both fields the tenets of one man may seem the rankest error to his neighbor.”

Roberts authored this passage in Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940), reversing the convictions of Jehovah Witness Newton Cantwell and his sons for going door to door and preaching their religious faith. Local officials charged the Cantwells with several offenses, including breach of the peace. Roberts ruled that the convictions violated the free-exercise of religion rights of Cantwell and his sons, recognizing that in a free society people have very different religious beliefs.

“The power of a state to abridge freedom of speech and of assembly is the exception rather than the rule and the penalizing even of utterances of a defined character must find its justification in a reasonable apprehension of danger to organized government.”

Justice Roberts wrote this statement in Herndon v. Lowry (1937), invalidating the conviction of labor agitator Angelo Herndon, who was punished by Georgia state officials essentially for being both black and a Communist. Herndon was prosecuted and convicted under a state anti-insurrection law for recruiting people to the Communist Party. The Court narrowly reversed his conviction by a 5-4 vote in an opinion by Justice Roberts, who recognized that restricting speech should be “the exception rather than the rule.”

“If the state cannot constrain one to violate his conscientious religious conviction by saluting the national emblem, then certainly it cannot punish him for imparting his views on the subject to his fellows and exhorting them to accept those views.”

Roberts penned this passage in Taylor v. Mississippi (1943), invalidating a Mississippi law used to convict Jehovah Witness R.E. Taylor for passing out literature that criticizing the saluting of the American flag. The Court issued this opinion the same day its more famous flag-salute decision West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), in which the High Court struck down a West Virginia law that allowed for the expulsion of students for saluting the flag. In the Taylor case, Roberts reasoned that the First Amendment protected individuals’ rights to imparting his or her views on flag salutes.

“We are equally clear that the Constitution imposes no such restraint on government as respects purely commercial advertising.”

Roberts drafted this line in Valentine v. Chrestensen (1942), ruling that the First Amendment did not protect purely commercial advertising. The case involved an entrepreneur F.J. Chrestensen who distributed leaflets on New York City streets, advertising his World War I submarine, which he showcased as an exhibit. Roberts and his colleagues on the Court took a crabbed view on commercial speech, one which the U.S. Supreme Court would overruled in the 1970s.

Link to article: https://www.freedomforuminstitute.org...

Other:

by Owen J Roberts (no photo)

by Owen J Roberts (no photo)

Source: Freedom Forum Institute

Owen J. Roberts (Wikipedia)

By DAVID L. HUDSON, JR. May 14, 2018

Justice Owen J. Roberts (1875–1955) was a U.S. Supreme Court Justice perhaps best known for changing his view on the constitutionality of federal New Deal legislation that established the minimum wage. His vote switch is colloquially referred to as the “switch in time that saved nine.”

But, Owen Roberts also authored several significant First Amendment decisions during his time on the High Court. Below are five of his more memorable passages on subjects such as freedom of assembly, freedom of religion, political dissident speech, and commercial advertising.

“Wherever the title of streets and parks may rest, they have immemorially been held in trust for the use of the public and, time out of mind, have been used for purposes of assembly, communicating thoughts between citizens, and discussing public questions.”

Roberts wrote this line in Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization (1939), ruling that a group of citizens could convene in a public park in Jersey City for a political assembly. Roberts’ passage above forms the basis for the public forum doctrine – the idea that certain types of public property are open to citizen engagement and First Amendment activity.

“In the realm of religious faith, and in that of political belief, sharp differences arise. In both fields the tenets of one man may seem the rankest error to his neighbor.”

Roberts authored this passage in Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940), reversing the convictions of Jehovah Witness Newton Cantwell and his sons for going door to door and preaching their religious faith. Local officials charged the Cantwells with several offenses, including breach of the peace. Roberts ruled that the convictions violated the free-exercise of religion rights of Cantwell and his sons, recognizing that in a free society people have very different religious beliefs.

“The power of a state to abridge freedom of speech and of assembly is the exception rather than the rule and the penalizing even of utterances of a defined character must find its justification in a reasonable apprehension of danger to organized government.”

Justice Roberts wrote this statement in Herndon v. Lowry (1937), invalidating the conviction of labor agitator Angelo Herndon, who was punished by Georgia state officials essentially for being both black and a Communist. Herndon was prosecuted and convicted under a state anti-insurrection law for recruiting people to the Communist Party. The Court narrowly reversed his conviction by a 5-4 vote in an opinion by Justice Roberts, who recognized that restricting speech should be “the exception rather than the rule.”

“If the state cannot constrain one to violate his conscientious religious conviction by saluting the national emblem, then certainly it cannot punish him for imparting his views on the subject to his fellows and exhorting them to accept those views.”

Roberts penned this passage in Taylor v. Mississippi (1943), invalidating a Mississippi law used to convict Jehovah Witness R.E. Taylor for passing out literature that criticizing the saluting of the American flag. The Court issued this opinion the same day its more famous flag-salute decision West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), in which the High Court struck down a West Virginia law that allowed for the expulsion of students for saluting the flag. In the Taylor case, Roberts reasoned that the First Amendment protected individuals’ rights to imparting his or her views on flag salutes.

“We are equally clear that the Constitution imposes no such restraint on government as respects purely commercial advertising.”

Roberts drafted this line in Valentine v. Chrestensen (1942), ruling that the First Amendment did not protect purely commercial advertising. The case involved an entrepreneur F.J. Chrestensen who distributed leaflets on New York City streets, advertising his World War I submarine, which he showcased as an exhibit. Roberts and his colleagues on the Court took a crabbed view on commercial speech, one which the U.S. Supreme Court would overruled in the 1970s.

Link to article: https://www.freedomforuminstitute.org...

Other:

by Owen J Roberts (no photo)

by Owen J Roberts (no photo)Source: Freedom Forum Institute

Owen J. Roberts, 1930-1945

OWEN J. ROBERTS was born in Germantown, Pennsylvania, on May 2, 1875. He was graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1895 and received a law degree in 1898. Roberts was named a University Fellow in 1898 and taught in an adjunct capacity at the University of Pennsylvania until 1919. Roberts established a law practice in Philadelphia and served in a number of public offices. In 1901, he was appointed Assistant District Attorney in Philadelphia and served until 1904. In 1918, Roberts was appointed a Special Deputy Attorney General of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. From 1924 to 1930, he served as a Special United States Attorney to investigate alleged wrongdoing in the Harding Administration. Roberts briefly returned to private practice in 1930, but on May 20, 1930, President Herbert Hoover nominated him to the Supreme Court of the United States. The Senate confirmed the appointment on June 2, 1930. While on the Court, Roberts oversaw an investigation into the attack on Pearl Harbor and headed a commission that traced art objects seized by the Germans in World War II. Roberts resigned from the Supreme Court on July 31, 1945, after fifteen years of service. He died on May 17, 1955, at the age of eighty.

Link to article: https://supremecourthistory.org/timel...

More:

by Joy Waldron Jasper (no photo)

by Joy Waldron Jasper (no photo)

Source: The Supreme Court Historical Society

OWEN J. ROBERTS was born in Germantown, Pennsylvania, on May 2, 1875. He was graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1895 and received a law degree in 1898. Roberts was named a University Fellow in 1898 and taught in an adjunct capacity at the University of Pennsylvania until 1919. Roberts established a law practice in Philadelphia and served in a number of public offices. In 1901, he was appointed Assistant District Attorney in Philadelphia and served until 1904. In 1918, Roberts was appointed a Special Deputy Attorney General of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. From 1924 to 1930, he served as a Special United States Attorney to investigate alleged wrongdoing in the Harding Administration. Roberts briefly returned to private practice in 1930, but on May 20, 1930, President Herbert Hoover nominated him to the Supreme Court of the United States. The Senate confirmed the appointment on June 2, 1930. While on the Court, Roberts oversaw an investigation into the attack on Pearl Harbor and headed a commission that traced art objects seized by the Germans in World War II. Roberts resigned from the Supreme Court on July 31, 1945, after fifteen years of service. He died on May 17, 1955, at the age of eighty.

Link to article: https://supremecourthistory.org/timel...

More:

by Joy Waldron Jasper (no photo)

by Joy Waldron Jasper (no photo)Source: The Supreme Court Historical Society

Books mentioned in this topic

The USS Arizona (other topics)The Court and the Constitution (other topics)

FDR v. The Constitution: The Court-Packing Fight and the Triumph of Democracy (other topics)

A search for a judicial philosophy;: Mr. Justice Roberts and the constitutional revolution of 1937 (other topics)

A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Joy Waldron Jasper (other topics)Owen J Roberts (other topics)

Burt Solomon (other topics)

Charles A. Leonard (other topics)

Philip Shenon (other topics)

More...

Biography

Owen Roberts graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the University of Pennsylvania in 1895. Three years later he began a prosperous private law practice in Philadephia after completing his legal eduation at the University of Pennsylvania Law School.

Roberts was a replacement nominee to the Supreme Court. His name was sent to the Senate after the defeat of John J. Parker's nomination in May 1930.

Roberts returned to the University of Pennsylania following his retirement from the Court. Roberts taught and served as dean.

Personal Information

Born Sunday, May 2, 1875

Died Tuesday, May 17, 1955

Childhood Location Pennsylvania

Childhood Surroundings Pennsylvania

Position Associate Justice

Seat 9

Nominated By Hoover

Commissioned on Tuesday, May 20, 1930

Sworn In Monday, June 2, 1930

Left Office Tuesday, July 31, 1945

Reason For Leaving Resigned

Length of Service 15 years, 1 month, 29 days

Home Pennsylvania

Source: http://www.oyez.org/justices/owen_j_r...