The History Book Club discussion

SUPREME COURT OF THE U.S.

>

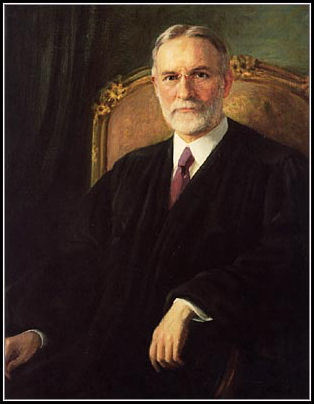

#70 - ASSOCIATE JUSTICE GEORGE SUTHERLAND

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Alexander George Sutherland (March 25, 1862 – July 18, 1942) was an English-born U.S. jurist and political figure. One of four appointments to the Supreme Court by President Warren G. Harding, he served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court between 1922 and 1938.

Alexander George Sutherland (March 25, 1862 – July 18, 1942) was an English-born U.S. jurist and political figure. One of four appointments to the Supreme Court by President Warren G. Harding, he served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court between 1922 and 1938. Early life and career

Sutherland was born in Buckinghamshire, England, to a Scottish father, Alexander George Sutherland, and an English mother, Frances, née Slater. A recent convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), Alexander Sutherland moved the family to Utah in the summer of 1863. Initially Alexander Sutherland settled his family in Springville, Utah, but moved to Montana and prospected for a few years before moving his family back to Utah in 1869, where he pursued a number of different occupations.

At the age of twelve, the need to help his family financially forced Sutherland to leave school and take a job, first as a clerk in a clothing store, then as an agent of the Wells Fargo Company. Yet Sutherland aspired to a higher education, and in 1879 had saved enough to attend Brigham Young Academy. There he studied under Karl G. Maeser, who proved an important influence in his intellectual development, most notably by introducing Sutherland to the ideas of Herbert Spencer, which would form an enduring part of Sutherland's philosophy. After graduating in 1881, Sutherland worked for the Rio Grande Western Railroad for a little over a year before moving to Michigan to enroll in the University of Michigan Law School, where he was a student of Thomas M. Cooley.

Sutherland left school before earning his law degree. After admission to the Michigan bar, he married Rosamond Lee in 1883; their marriage proved a happy one, and produced two daughters and a son. After his marriage, Sutherland moved back to Utah, where he joined his father (who had also become a lawyer) in a partnership in Provo. In 1886, they dissolved their partnership and Sutherland formed a new one with Samuel Thurman, a future chief justice of the Utah Supreme Court. After running unsuccessfully as the Liberal Party candidate for mayor of Provo, Sutherland moved to Salt Lake City in 1893. There he joined one of the state's leading law firms, and the following year was one of the organizers of the Utah State Bar Association. In 1896 he was elected as a Republican to the newly created Utah State Senate, where he served as chairman of the senate's Judiciary Committee and sponsored legislation granting powers of eminent domain to mining and irrigation companies.

Years in Congress

In 1900, Sutherland received the Republican nomination as the party's candidate for Utah's seat in the federal House of Representatives. In the subsequent election, Sutherland narrowly defeated his Democratic incumbent (and former law partner), William H. King, by 241 votes out of over 90,000 cast. He went on to serve as a Representative in the 57th Congress, where he fought to maintain the tariff on sugar and was active in both Indian affairs and legislation addressing the irrigation of arid lands.

Sutherland declined to run for a second term and returned to Utah in order to campaign for election to the United States Senate. With the state legislature firmly under Republican control, the contest was an intra-party battle with the incumbent, Thomas Kearns. With the backing of Utah's other senator, Reed Smoot, Sutherland secured the unanimous support of the caucus in January 1905. Sutherland repaid his debt to Smoot in 1907 by speaking on the floor in the Senate in defense of the senior senator during the climax of the Smoot hearings.

Sutherland's tenure in the Senate coincided with the Progressive Era in American politics. He voted for much of Theodore Roosevelt' s legislative program, including the Pure Food and Drug Act, the Hepburn Act, and the Federal Employers Liability Act. He was also "a longstanding women’s rights advocate. He introduced the Nineteenth Amendment into the Senate . . . campaigned for the passage of that amendment, helped draft the Equal Rights Amendment, and was a friend and adviser of Alice Paul of the National Woman's Party." Yet he generally sided with the "Old Guard" of conservatives who battled with their Progressive counterparts within the party during William Howard Taft's presidency. He was also involved closely with the legal codification of the period, and joined Taft in opposing the legislation admitting New Mexico and Arizona into the union because of clauses within their constitutions allowing for the recall of judges.

The election of Woodrow Wilson and the Democratic takeover of Congress in 1912 put Sutherland and the other conservatives on the defensive. By now a national figure, Sutherland opposed many of Wilson's legislative proposals and foreign policy measures. Sutherland's opposition contributed to his defeat in 1916, when he faced reelection for the first time under the terms of the Seventeenth Amendment. Once again he faced William H. King, who campaigned on Sutherland's opposition to the popular president. Following his Senate defeat, he resumed the private practice of law in Washington, D.C., and served as President of the American Bar Association from 1916 to 1917.

Supreme Court

On September 5, 1922, Sutherland was nominated by President Warren G. Harding to the Associate Justice seat on the Supreme Court of the United States vacated by John Hessin Clarke. Sutherland was confirmed by the United States Senate on September 5, 1922, and received his commission the same day.

Sutherland wrote a decision refusing to declare unconstitutional a local zoning ordinance, in Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co.. The decision was widely interpreted as a general endorsement of the constitutionality of zoning laws.

During Franklin Roosevelt's early years in office as president, Justice Sutherland along with James Clark McReynolds, Pierce Butler and Willis Van Devanter, was part of the conservative Four Horsemen, who were instrumental in striking down Roosevelt's New Deal legislation. Sutherland was regarded as the leader of this conservative bloc of judges as well.

Important decisions authored by Sutherland include the 1932 case Powell v. Alabama, overturning a conviction in the Scottsboro Boys Case because the defendant, Ozie Powell, was deprived of his right to counsel, and U.S. v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp..

In United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), Sutherland authored a decision that classified Indian Sikh although classified as members of the "Caucasian race," as not white within the meaning of the Naturalization Act of 1790, and thus ineligible for naturalized American citizenship.

In 1937, the Supreme Court began to side with New Deal policies and Sutherland's influence declined. Sutherland retired from the U.S. Supreme Court on January 17, 1938, as the balance of power in the US Supreme Court was shifting away from him. Following his retirement as a Justice, Sutherland sat by special designation as a member of the Second Circuit panel that reviewed the bribery conviction of former Second Circuit Chief Judge Martin Manton, and authored the court's opinion upholding the conviction.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_S...

Books by and about:

Books by and about:(no image) Mr. Justice Sutherland, A Man Against the State by Joel Francis Paschal (no photo)

The Real Culture War: Individualism vs. Collectivism & How Bill O'Reilly Got It All Wrong

The Real Culture War: Individualism vs. Collectivism & How Bill O'Reilly Got It All Wrong  by Gerard Emershaw(no photo)

by Gerard Emershaw(no photo)Synopsis:

In his book Culture Warrior, Bill O'Reilly--the host of the Fox News Channel show "The O'Reilly Factor"--incorrectly characterizes the Culture War as a social, political, and intellectual struggle between "traditionalists" and "secular-progressives."

THE REAL CULTURE WAR analyzes, dissects, and discredits Bill O'Reilly's conception of the Culture War and argues that he gets it all wrong. His "traditionalism" and "secular-progressivism" are merely two heads of the same collectivist beast.

THE REAL CULTURE WAR pits Individualism versus Collectivism. Individualism states that human beings have intrinsic value and possess the natural rights to life, liberty, and property. This view was held by the Founding Fathers. Collectivism states that human beings only have value in virtue of their relationship to the collective. This view was held by the "Philosopher-Kings" (PKs)--tyrannical leaders who view themselves as enlightened and exempt themselves from the draconian laws they force upon others.

PKs discussed in THE REAL CULTURE WAR include Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, and Mao as well as American leaders Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Al Gore, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama. The intellectual, historical, and empirical foundations of Individualism and Collectivism are examined, and it is argued that logic and reason establish that Individualism is the superior worldview because Individualism naturally leads to peace, prosperity, and freedom whereas Collectivism invariably leads to war, poverty, and tyranny.

Specific formulations of Collectivism--Communism, Fascism/Nazism, Progressivism, Environmentalism, Neoconservatism, Racism, Religionism, Corporatism, and Labor Unionism--are fully exposed and critiqued. Next, an alternate conception of government in the form of the Individualist State is developed and defended while building the "Night-Watchman State" from first principles. Within this "Minarchist State" is a system of taxation which provides a justifiable connection between the tax paid by the people in order to maintain the State whose duty it is to defend the natural rights of the people. These natural rights--life, liberty, and property--are each examined in depth and controversial issues related to them are analyzed fully in order to present philosophically sound solutions. Additionally, the structure and functions of the three branches of government--Executive, Legislative, and Judicial--of the Individualist State are explained, and it is demonstrated that the form of government written into the Constitution is a "Night-Watchman State" similar to the Individualist State.

Later, modern threats to Individualism--the economic tyranny of the Federal Reserve, the globalism of the New World Order, and the collectivist Neo-Progressivism of President Barack Obama--within the United States are described in detail.

Finally, a five-step plan of action is revealed for what individualists can do to win the Real Culture War.

Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Supreme Court

Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Supreme Court by

by

Artemus Ward, Christopher Brough (no photo), and Robert Arnold (no photo)

Artemus Ward, Christopher Brough (no photo), and Robert Arnold (no photo)Synopsis:

The US Supreme Court is an institution that operates almost totally behind closed doors. This book opens those doors by providing a comprehensive look at the justices, procedures, cases, and issues over the institution s more than 200-year history. The Court is a legal institution born from a highly politicized process. Modern justices time their departures to coincide with favorable administrations and the confirmation process has become a highly-charged political spectacle played out on television and in the national press.

Throughout its history, the Court has been at the center of the most important issues facing the nation: federalism, separation of powers, war, slavery, civil rights, and civil liberties. Through it all, the Court has generally, though not always, reflected the broad views of the American people as the justices decide the most vexing issues of the day. The Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Supreme Court covers its history through a chronology, an introductory essay, appendixes, and an extensive bibliography.

The dictionary section has over 700 cross-referenced entries on every justice, major case, issue, and process that comprises the Court s work. This book is an excellent access point for students, researchers, and anyone wanting to know more about the Supreme Court."

message 6:

by

Lorna, Assisting Moderator (T) - SCOTUS - Civil Rights

(last edited Jun 18, 2017 06:37PM)

(new)

George Sutherland

Representative, Senator, U.S. Supreme Court Justice, Defender of the U.S. Constitution - Brigham Young Academy High School Class of 1881

Justice George Sutherland

George Sutherland's distinction as Utah's only U.S. Supreme Court justice capped a long and distinguished legal and political career.

Born on 25 March 1862 in England, he immigrated to the United States with his parents in 1863. They had joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in England, and by the 1870s the family had settled in Utah. His family later disaffected from the Mormon Church.

From 1879 to 1881 Sutherland attended Brigham Young Academy and absorbed the Social Darwinism of Herbert Spencer as well as a reverence for the Constitution from Academy principal Karl G. Maeser -- both were ideas that would shape his life.

In 1883 Sutherland had completed one term at the University of Michigan Law School and qualified for the Michigan bar. That summer he returned to Utah and married Rosamund Lee. They had three children -- Emma (born 1884), Philip (born 1886), and Edith (born 1888) -- whom he supported by practicing law in Utah. In 1894 he helped to organize the Utah State Bar Association.

In 1896 Sutherland, a Republican, joined the first Utah House of Representatives. In 1899 he was admitted to the bar of the United States Supreme Court, and from 1900 to 1903 he served as Utah's only Representative in the U.S. House.

He then served in the U.S. Senate from 1905 to 1916. During this period, he supported much progressive legislation, including a Utah law for an eight-hour day in the mining and smelting industries, as well as national statutes such as the Pure Food and Drug Act.

Defeated for the Senate nomination in 1916, Sutherland went into private law practice, served as president of the American Bar Association, and became an advisor to Republican presidential hopeful Warren G. Harding in the campaign of 1920. Harding's election and the sudden resignation of a Supreme Court justice in 1922 paved the way for Sutherland's appointment to the bench.

In 1922, President Harding appointed Sutherland to the U.S. Supreme Court, where Sutherland became a jealous protector of individual liberty.

In 1896 Sutherland, a Republican, joined the first Utah House of Representatives. In 1899 he was admitted to the bar of the United States Supreme Court, and from 1900 to 1903 he served as Utah's only Representative in the U.S. House.

One of his first cases, for example, was Adkins v. Lyons in which Sutherland supported a woman’s right to negotiate a wage contract for herself —- without state regulation.

In a later case, New Ice Company v. Liebmann, Sutherland wrote the majority opinion that struck down an Oklahoma law that virtually prohibited anyone from entering the ice business to compete with the monopolistic New State Ice Company.

As Sutherland was to discover, the New Ice case was the tip of an emerging iceberg in government regulation. In the thirties, he opposed most of the New Deal legislation, and became the intellectual leader of the "Four Horsemen" -- four conservative justices consistently voting against President Franklin D. Roosevelt's programs.

The National Industrial Recovery Act (NRA), which was an early part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal program, far surpassed the New State Ice Company in its threat to free enterprise. All major industries in the nation were invited to form cartels. They were urged to develop industry-wide codes that would regulate the prices charged for the products they made, wages paid, number of hours worked, and even the quality of products sold. These NRA rules would, in practice, be binding on all corporations in their industry, even those who opposed such interference.

Over 500 NRA codes emerged, which stifled American production through higher prices for goods and lack of innovation in industry. As monetary expert Benjamin Anderson observed, “NRA was not a revival measure. It was an anti-revival measure.” Indeed, it was a major reason the Great Depression worsened in 1933.

Read the remainder of the article at: http://www.byhigh.org/Alumni_P_to_T/S...

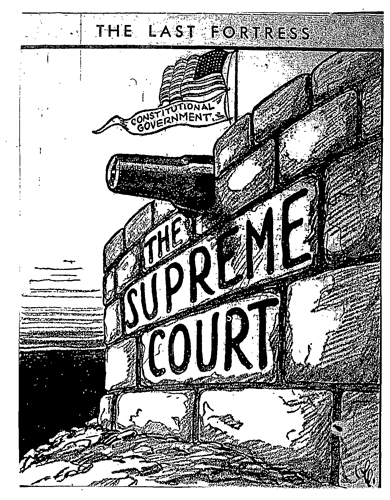

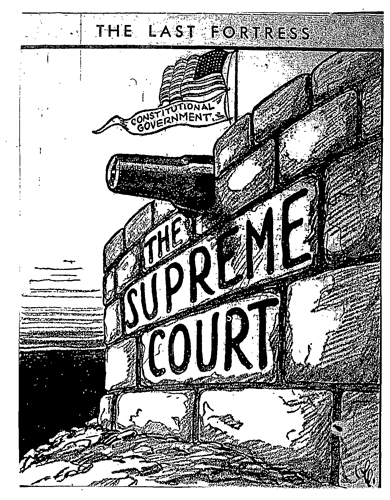

A political cartoon of that era

The Justices of the US Supreme Court pose for a photo in 1932. Justice George Sutherland, BYA High School Class of 1881, is the seated on the right side

Other:

by Edward Lazarus (no photo)

by Edward Lazarus (no photo)

Source(s): Brigham Young University High School Alumnae Organization

Representative, Senator, U.S. Supreme Court Justice, Defender of the U.S. Constitution - Brigham Young Academy High School Class of 1881

Justice George Sutherland

George Sutherland's distinction as Utah's only U.S. Supreme Court justice capped a long and distinguished legal and political career.

Born on 25 March 1862 in England, he immigrated to the United States with his parents in 1863. They had joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in England, and by the 1870s the family had settled in Utah. His family later disaffected from the Mormon Church.

From 1879 to 1881 Sutherland attended Brigham Young Academy and absorbed the Social Darwinism of Herbert Spencer as well as a reverence for the Constitution from Academy principal Karl G. Maeser -- both were ideas that would shape his life.

In 1883 Sutherland had completed one term at the University of Michigan Law School and qualified for the Michigan bar. That summer he returned to Utah and married Rosamund Lee. They had three children -- Emma (born 1884), Philip (born 1886), and Edith (born 1888) -- whom he supported by practicing law in Utah. In 1894 he helped to organize the Utah State Bar Association.

In 1896 Sutherland, a Republican, joined the first Utah House of Representatives. In 1899 he was admitted to the bar of the United States Supreme Court, and from 1900 to 1903 he served as Utah's only Representative in the U.S. House.

He then served in the U.S. Senate from 1905 to 1916. During this period, he supported much progressive legislation, including a Utah law for an eight-hour day in the mining and smelting industries, as well as national statutes such as the Pure Food and Drug Act.

Defeated for the Senate nomination in 1916, Sutherland went into private law practice, served as president of the American Bar Association, and became an advisor to Republican presidential hopeful Warren G. Harding in the campaign of 1920. Harding's election and the sudden resignation of a Supreme Court justice in 1922 paved the way for Sutherland's appointment to the bench.

In 1922, President Harding appointed Sutherland to the U.S. Supreme Court, where Sutherland became a jealous protector of individual liberty.

In 1896 Sutherland, a Republican, joined the first Utah House of Representatives. In 1899 he was admitted to the bar of the United States Supreme Court, and from 1900 to 1903 he served as Utah's only Representative in the U.S. House.

One of his first cases, for example, was Adkins v. Lyons in which Sutherland supported a woman’s right to negotiate a wage contract for herself —- without state regulation.

In a later case, New Ice Company v. Liebmann, Sutherland wrote the majority opinion that struck down an Oklahoma law that virtually prohibited anyone from entering the ice business to compete with the monopolistic New State Ice Company.

As Sutherland was to discover, the New Ice case was the tip of an emerging iceberg in government regulation. In the thirties, he opposed most of the New Deal legislation, and became the intellectual leader of the "Four Horsemen" -- four conservative justices consistently voting against President Franklin D. Roosevelt's programs.

The National Industrial Recovery Act (NRA), which was an early part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal program, far surpassed the New State Ice Company in its threat to free enterprise. All major industries in the nation were invited to form cartels. They were urged to develop industry-wide codes that would regulate the prices charged for the products they made, wages paid, number of hours worked, and even the quality of products sold. These NRA rules would, in practice, be binding on all corporations in their industry, even those who opposed such interference.

Over 500 NRA codes emerged, which stifled American production through higher prices for goods and lack of innovation in industry. As monetary expert Benjamin Anderson observed, “NRA was not a revival measure. It was an anti-revival measure.” Indeed, it was a major reason the Great Depression worsened in 1933.

Read the remainder of the article at: http://www.byhigh.org/Alumni_P_to_T/S...

A political cartoon of that era

The Justices of the US Supreme Court pose for a photo in 1932. Justice George Sutherland, BYA High School Class of 1881, is the seated on the right side

Other:

by Edward Lazarus (no photo)

by Edward Lazarus (no photo)Source(s): Brigham Young University High School Alumnae Organization

Remembering George Sutherland: Defender of the Constitution

By Dr. Burton W. Folsom - May 2, 2005

U.S. Supreme Court Justice George Sutherland understood the value of limited government and was a valiant defender of individual liberty.

Who was George Sutherland? Some remember him as a Michigan-trained justice of the United States Supreme Court, but he was more than that.

Seventy years ago this month — May 27, 1935 — Sutherland led the charge in striking down what may have been the greatest legislative roadblock ever put in the path of free enterprise in America: the National Recovery Act. Sutherland’s victory in declaring the NRA unconstitutional returned competition to American business and lowered prices for consumers.

Sutherland was a quiet, unlikely hero. Born in England in 1862, he and his parents migrated to Utah in the 1860s, and made their living from mining. Young Sutherland showed strong aptitude, and after schooling in Utah he went to the University of Michigan law school. In Ann Arbor, he studied under Thomas Cooley, whose landmark book Constitutional Limitations educated generations of students in the virtues of limited government.

Sutherland learned his lessons well and returned to Utah committed to supporting free enterprise and natural rights, which stressed the individual worth of each person and the importance of providing constitutional protection to everyone. He entered politics in Utah — a protestant in a Mormon state — and won election first to the state legislature, then to the U.S. House of Representatives, and finally to the U. S. Senate.

In 1922, President Harding appointed Sutherland to the U.S. Supreme Court, where Sutherland became a jealous protector of individual liberty. One of his first cases, for example, was Adkins v. Lyons in which Sutherland supported a woman’s right to negotiate a wage contract for herself — without state regulation. In a later case, New Ice Company v. Liebmann, Sutherland wrote the majority opinion that struck down an Oklahoma law that virtually prohibited anyone from entering the ice business to compete with the monopolistic New State Ice Company.

As Sutherland was to discover, the New Ice case was the tip of an emerging iceberg in government regulation. The NRA, which was part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal program, far surpassed the New State Ice Company in its threat to free enterprise. All major industries in the nation were invited to form cartels. They were urged to develop industry-wide codes that would regulate the prices charged for the products they made, wages paid, number of hours worked, and even the quality of products sold. These NRA rules would, in practice, be binding on all corporations in their industry, even those who opposed such interference.

Over 500 NRA codes emerged, which stifled American production through higher prices for goods and lack of innovation in industry. As monetary expert Benjamin Anderson observed, “NRA was not a revival measure. It was an anti-revival measure.” Indeed, it was a major reason the Great Depression worsened in 1933.

Finally, the Schechter brothers challenged the constitutionality of this law which forced so much of American business into a straitjacket. Their lawyers observed that the NRA was trying “to regulate human activities literally from the cradle to the grave and beyond.” For example, the tailors of America decided in their code to establish 40 cents as the minimum price that could be charged to press a pair of pants. When Jack Magid in New Jersey charged a customer only 35 cents, he was sent to jail for breaking the law.

In the Schechter Poultry Corporation v. U.S. case, Sutherland ruled against the NRA and for the rights of the Schechter brothers to sell chickens freely in the Jewish community of New York City. Justices Sutherland and James McReynolds were effective in their questioning — so effective that the audience frequently erupted in laughter as the government tried to explain why customers should not have been allowed to select the particular chickens they wished to purchase from the Schecters, but should have had them selected randomly instead.

So persuasive was Sutherland, and so bad was the NRA, that the Supreme Court voted unanimously that the law was unconstitutional. Three years later Sutherland retired from the court, leaving future generations to defend the Constitution. Seventy years after his landmark rebuke of the NRA we should remember him for his commitment to individual liberty and for temporarily halting the rise of big government.

Link to article: https://www.mackinac.org/V2005-15

Other:

by William E. Leuchtenburg (no photo)

by William E. Leuchtenburg (no photo)

Source: Mackinac Center for Public Study

By Dr. Burton W. Folsom - May 2, 2005

U.S. Supreme Court Justice George Sutherland understood the value of limited government and was a valiant defender of individual liberty.

Who was George Sutherland? Some remember him as a Michigan-trained justice of the United States Supreme Court, but he was more than that.

Seventy years ago this month — May 27, 1935 — Sutherland led the charge in striking down what may have been the greatest legislative roadblock ever put in the path of free enterprise in America: the National Recovery Act. Sutherland’s victory in declaring the NRA unconstitutional returned competition to American business and lowered prices for consumers.

Sutherland was a quiet, unlikely hero. Born in England in 1862, he and his parents migrated to Utah in the 1860s, and made their living from mining. Young Sutherland showed strong aptitude, and after schooling in Utah he went to the University of Michigan law school. In Ann Arbor, he studied under Thomas Cooley, whose landmark book Constitutional Limitations educated generations of students in the virtues of limited government.

Sutherland learned his lessons well and returned to Utah committed to supporting free enterprise and natural rights, which stressed the individual worth of each person and the importance of providing constitutional protection to everyone. He entered politics in Utah — a protestant in a Mormon state — and won election first to the state legislature, then to the U.S. House of Representatives, and finally to the U. S. Senate.

In 1922, President Harding appointed Sutherland to the U.S. Supreme Court, where Sutherland became a jealous protector of individual liberty. One of his first cases, for example, was Adkins v. Lyons in which Sutherland supported a woman’s right to negotiate a wage contract for herself — without state regulation. In a later case, New Ice Company v. Liebmann, Sutherland wrote the majority opinion that struck down an Oklahoma law that virtually prohibited anyone from entering the ice business to compete with the monopolistic New State Ice Company.

As Sutherland was to discover, the New Ice case was the tip of an emerging iceberg in government regulation. The NRA, which was part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal program, far surpassed the New State Ice Company in its threat to free enterprise. All major industries in the nation were invited to form cartels. They were urged to develop industry-wide codes that would regulate the prices charged for the products they made, wages paid, number of hours worked, and even the quality of products sold. These NRA rules would, in practice, be binding on all corporations in their industry, even those who opposed such interference.

Over 500 NRA codes emerged, which stifled American production through higher prices for goods and lack of innovation in industry. As monetary expert Benjamin Anderson observed, “NRA was not a revival measure. It was an anti-revival measure.” Indeed, it was a major reason the Great Depression worsened in 1933.

Finally, the Schechter brothers challenged the constitutionality of this law which forced so much of American business into a straitjacket. Their lawyers observed that the NRA was trying “to regulate human activities literally from the cradle to the grave and beyond.” For example, the tailors of America decided in their code to establish 40 cents as the minimum price that could be charged to press a pair of pants. When Jack Magid in New Jersey charged a customer only 35 cents, he was sent to jail for breaking the law.

In the Schechter Poultry Corporation v. U.S. case, Sutherland ruled against the NRA and for the rights of the Schechter brothers to sell chickens freely in the Jewish community of New York City. Justices Sutherland and James McReynolds were effective in their questioning — so effective that the audience frequently erupted in laughter as the government tried to explain why customers should not have been allowed to select the particular chickens they wished to purchase from the Schecters, but should have had them selected randomly instead.

So persuasive was Sutherland, and so bad was the NRA, that the Supreme Court voted unanimously that the law was unconstitutional. Three years later Sutherland retired from the court, leaving future generations to defend the Constitution. Seventy years after his landmark rebuke of the NRA we should remember him for his commitment to individual liberty and for temporarily halting the rise of big government.

Link to article: https://www.mackinac.org/V2005-15

Other:

by William E. Leuchtenburg (no photo)

by William E. Leuchtenburg (no photo)Source: Mackinac Center for Public Study

JUSTICE GEORGE SUTHERLAND (1862-1942)

Guest Essayist: Daniel A. Cotter

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (Wikipedia)

Justice George Sutherland: One of the Four Horsemen

Introduction

In the Supreme Court’s history, six justices were born outside of the United States. The fifth of those born on foreign soil was George Sutherland (second born in England). After a career in private practice and public office, Sutherland became an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court in 1923, and would figure prominently in the New Deal jurisprudence as one of the “Four Horsemen” of the Supreme Court.

Early Life and Career

George Sutherland was born on March 25, 1862, in Buckinghamshire, England, to Alexander George Sutherland and Frances Sutherland (nee Slater). His father, a convert to The Church of Jesus Christ Latter Day Saints, moved his family to the Utah Territory in 1863 and pursued prospecting, as well as other occupations, including practicing law, there. His father later renounced his Mormon faith. At the age of seventeen, Sutherland enrolled in Brigham Young Academy (now Brigham Young University) and, upon graduation, attended the University of Michigan Law School.

Sutherland did not graduate from law school, but was admitted to the bar in Michigan, and returned to Utah to join his father’s law practice. Sutherland practiced law in Utah for almost a decade. During that time, he also served as a State Senator in the first Utah Senate. In 1900, he ran for and was elected to the United States House of Representatives, defeating his former law partner. After one term, Sutherland returned to Utah and private practice, preparing for a run for a United States Senate seat.

In 1905, he became a U.S. Senator and served two terms, establishing a strong reputation for his mastery of the Constitution. Sutherland also advocated for women’s rights, sponsoring the Nineteenth Amendment in the Senate and working hard for its passage and ratification. Sutherland is also considered one of the main proponents behind the passage of the Federal Employer Liability Act, which established a worker’s compensation system. In his last year as Senator, Sutherland served as President of the American Bar Association.

Upon leaving the Senate, he remained in Washington, D.C., where he practiced law and was a close advisor to President Warren Harding. On September 5, 1922, Harding nominated Sutherland to the vacancy created by Justice John Clarke’s retirement. Sutherland was confirmed by voice vote the same day and took his oath on October 21, 1922. Along with fellow Justices James McReynolds, Pierce Butler and Willis Van Devanter, Sutherland became part of a conservative bloc on the Supreme Court that became known as the “Four Horsemen.” During his sixteen years on the Court, Sutherland voted with the majority to invalidate seventeen acts of Congress, including several of the “New Deal” initiatives advanced by President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration.

The Four Horsemen

When Van Devanter and McReynolds were joined by Sutherland and then Butler in early 1923, they formed a powerful conservative faction on the Court, first under Chief Justice William Howard Taft and then under Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes. In the 1932 Term, their cohesiveness on Court decisions resulted in the nickname “The Four Horsemen” from the national press (a reference to the “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse”). From 1932 to 1937, the Four Horsemen (together with Chief Justice Hughes and Justice Owen Roberts) issued opinions invalidating much of President Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation, including the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the Federal Farm Bankruptcy Act, the Railroad Act, and the Coal Mining Act. The Four Horsemen also ruled with Justices Roberts and Hughes that the National Industrial Act and minimum wage laws for women and children were unconstitutional. One of the last opinions joined by the four justices was a dissent in Associated Press v. National Labor Relations Board (1937), a case in which the majority held that the Wagner Act’s prohibition of unfair labor practices applied to the Associated Press and the First Amendment did not shield the AP from the Act. Sutherland, writing for the Four Horsemen, dissented:

No one can read the long history which records the stern and often bloody struggles by which these cardinal rights [in the First Amendment] were secured, without realizing how necessary it is to preserve them against any infringement, however slight….For the saddest epitaph which can be carved in memory of a vanished liberty is that it was lost because its possessors failed to stretch forth a saving hand while yet there was time.

The Four Horsemen rode to the Supreme Court in one car every day to discuss strategy and positions, and were opposed to laws regulating labor as well as state economic regulation. The Supreme Court’s invalidation of much of the New Deal led to a potential constitutional crisis when President Roosevelt proposed a court-packing plan that would have added a new justice for each sitting justice over the age of 70. (The Constitution does not specify the number of justices who sit on the Supreme Court, and the current composition of nine justices, which was also in effect at the time of Roosevelt’s proposal, is set by the Judiciary Act of 1869.) The crisis was averted when Justice Roberts voted to uphold a Washington minimum wage law in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937). Known as the “switch in time that saved nine,” recent scholars have concluded that Roberts actually cast his vote in this case before the court-packing legislation was introduced, rather than as a result of political pressure stemming from Roosevelt’s effort to reconstitute the Court. Sutherland considered retirement from the Court several times, but was determined to remain on the bench so long as President Roosevelt continued his efforts to pack the Court. Once that plan was defeated, Sutherland gave notice of his plans to retire and did so on January 17, 1938, at the age of 75.

Sutherland’s Other Work on the Court

In his more than fifteen years on the Court, Sutherland wrote a number of other important decisions, including Powell v. Alabama, a 1932 case that overturned a conviction in the Scottsboro Boys Case because the defendant was deprived of counsel. He also wrote the majority opinion in U.S. v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., a case that established the president’s strong powers in foreign affairs.

Conclusion

Upon his retirement, Sutherland was replaced by Stanley Reed. Combined with the retirement of Van Devanter the previous year, The Four Horsemen were no more and Roosevelt saw a number of New Deal victories from the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has not seen such a consistent voting bloc since the Four Horsemen and one wonders if we will see its equal in the future. To date, Sutherland is the only Utahan to sit on the Supreme Court.

Link to audiotape biography: https://constitutingamerica.org/justi...

Link to article: https://constitutingamerica.org/justi...

Other: \

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)

Source: Constituting America, Wikipedia

Guest Essayist: Daniel A. Cotter

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (Wikipedia)

Justice George Sutherland: One of the Four Horsemen

Introduction

In the Supreme Court’s history, six justices were born outside of the United States. The fifth of those born on foreign soil was George Sutherland (second born in England). After a career in private practice and public office, Sutherland became an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court in 1923, and would figure prominently in the New Deal jurisprudence as one of the “Four Horsemen” of the Supreme Court.

Early Life and Career

George Sutherland was born on March 25, 1862, in Buckinghamshire, England, to Alexander George Sutherland and Frances Sutherland (nee Slater). His father, a convert to The Church of Jesus Christ Latter Day Saints, moved his family to the Utah Territory in 1863 and pursued prospecting, as well as other occupations, including practicing law, there. His father later renounced his Mormon faith. At the age of seventeen, Sutherland enrolled in Brigham Young Academy (now Brigham Young University) and, upon graduation, attended the University of Michigan Law School.

Sutherland did not graduate from law school, but was admitted to the bar in Michigan, and returned to Utah to join his father’s law practice. Sutherland practiced law in Utah for almost a decade. During that time, he also served as a State Senator in the first Utah Senate. In 1900, he ran for and was elected to the United States House of Representatives, defeating his former law partner. After one term, Sutherland returned to Utah and private practice, preparing for a run for a United States Senate seat.

In 1905, he became a U.S. Senator and served two terms, establishing a strong reputation for his mastery of the Constitution. Sutherland also advocated for women’s rights, sponsoring the Nineteenth Amendment in the Senate and working hard for its passage and ratification. Sutherland is also considered one of the main proponents behind the passage of the Federal Employer Liability Act, which established a worker’s compensation system. In his last year as Senator, Sutherland served as President of the American Bar Association.

Upon leaving the Senate, he remained in Washington, D.C., where he practiced law and was a close advisor to President Warren Harding. On September 5, 1922, Harding nominated Sutherland to the vacancy created by Justice John Clarke’s retirement. Sutherland was confirmed by voice vote the same day and took his oath on October 21, 1922. Along with fellow Justices James McReynolds, Pierce Butler and Willis Van Devanter, Sutherland became part of a conservative bloc on the Supreme Court that became known as the “Four Horsemen.” During his sixteen years on the Court, Sutherland voted with the majority to invalidate seventeen acts of Congress, including several of the “New Deal” initiatives advanced by President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration.

The Four Horsemen

When Van Devanter and McReynolds were joined by Sutherland and then Butler in early 1923, they formed a powerful conservative faction on the Court, first under Chief Justice William Howard Taft and then under Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes. In the 1932 Term, their cohesiveness on Court decisions resulted in the nickname “The Four Horsemen” from the national press (a reference to the “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse”). From 1932 to 1937, the Four Horsemen (together with Chief Justice Hughes and Justice Owen Roberts) issued opinions invalidating much of President Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation, including the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the Federal Farm Bankruptcy Act, the Railroad Act, and the Coal Mining Act. The Four Horsemen also ruled with Justices Roberts and Hughes that the National Industrial Act and minimum wage laws for women and children were unconstitutional. One of the last opinions joined by the four justices was a dissent in Associated Press v. National Labor Relations Board (1937), a case in which the majority held that the Wagner Act’s prohibition of unfair labor practices applied to the Associated Press and the First Amendment did not shield the AP from the Act. Sutherland, writing for the Four Horsemen, dissented:

No one can read the long history which records the stern and often bloody struggles by which these cardinal rights [in the First Amendment] were secured, without realizing how necessary it is to preserve them against any infringement, however slight….For the saddest epitaph which can be carved in memory of a vanished liberty is that it was lost because its possessors failed to stretch forth a saving hand while yet there was time.

The Four Horsemen rode to the Supreme Court in one car every day to discuss strategy and positions, and were opposed to laws regulating labor as well as state economic regulation. The Supreme Court’s invalidation of much of the New Deal led to a potential constitutional crisis when President Roosevelt proposed a court-packing plan that would have added a new justice for each sitting justice over the age of 70. (The Constitution does not specify the number of justices who sit on the Supreme Court, and the current composition of nine justices, which was also in effect at the time of Roosevelt’s proposal, is set by the Judiciary Act of 1869.) The crisis was averted when Justice Roberts voted to uphold a Washington minimum wage law in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937). Known as the “switch in time that saved nine,” recent scholars have concluded that Roberts actually cast his vote in this case before the court-packing legislation was introduced, rather than as a result of political pressure stemming from Roosevelt’s effort to reconstitute the Court. Sutherland considered retirement from the Court several times, but was determined to remain on the bench so long as President Roosevelt continued his efforts to pack the Court. Once that plan was defeated, Sutherland gave notice of his plans to retire and did so on January 17, 1938, at the age of 75.

Sutherland’s Other Work on the Court

In his more than fifteen years on the Court, Sutherland wrote a number of other important decisions, including Powell v. Alabama, a 1932 case that overturned a conviction in the Scottsboro Boys Case because the defendant was deprived of counsel. He also wrote the majority opinion in U.S. v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., a case that established the president’s strong powers in foreign affairs.

Conclusion

Upon his retirement, Sutherland was replaced by Stanley Reed. Combined with the retirement of Van Devanter the previous year, The Four Horsemen were no more and Roosevelt saw a number of New Deal victories from the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has not seen such a consistent voting bloc since the Four Horsemen and one wonders if we will see its equal in the future. To date, Sutherland is the only Utahan to sit on the Supreme Court.

Link to audiotape biography: https://constitutingamerica.org/justi...

Link to article: https://constitutingamerica.org/justi...

Other: \

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)Source: Constituting America, Wikipedia

Chasing the Devil Around the Stump: Securities Regulation, the SEC and the Courts

A New Era Unfolds: The Four Horsemen and Jones v. SEC

February 25, 1937 The Last Fortress

Yet the path for a new regime of regulation was not easy. The Supreme Court, with four conservative justices -- Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland, and Willis Van Devanter -- continued to decide cases based on the substantive due process protection of contractual and property rights. They often convinced one or more fellow justices to form a majority to defeat new attempts at property regulation. As New Deal laws regulating business came before the Supreme Court, the conservative majority, protecting property rights, struck many of them down as unconstitutional violations of the delegation powers or the interstate commerce clause. The conservative four at the heart of these denials came to be referred in apocryphal admonition as the “Four Horsemen.”

These actions posed immense problems for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which sought to use its broad statutory authority to regulate individual and company property rights in every state of the nation. Facing this dilemma, the SEC deftly moved cases of its own choosing to the Court with arguments they hoped would reverse the Court’s anti-New Deal and anti-regulatory majority.

The SEC found intellectual support in Justice Louis Brandeis’ dissent in the 1933 case of Liggett v Lee, in which Brandeis, realizing the effect of the conservative majority philosophy on increased administrative regulations, attempted to reformulate the argument. The case involved a Florida attempt to tax chain stores, generally constituted by larger national retail chains, in a greater amount than individual, locally-owned stores. The chain stores challenged the regulation as arbitrary and unreasonable, and thus unconstitutional. Justice Owen Roberts, writing for the conservative majority, agreed with the chain stores that the state regulation was unconstitutional.

Justice Brandeis dissented, arguing that the legislative goal of “protecting the individual, independently-owned, retail stores from the competition of chain stores” was valid. He argued that Florida was regulating corporations in intrastate commerce, and that the state had acted entirely within its powers. “Limitations upon the scope of a business corporation’s powers and activity were …universal,” and thus, “the difference in power between corporations and natural persons is ample basis for placing them in different classes.” Brandeis wanted to show that the power of huge national corporations, which he believed controlled and mismanaged much of the reeling economy, should be a proper constitutional basis for regulation. Proponents of New Deal administrative regulatory reform cheered. The SEC, arguing cases in lower courts as they made their way to the Supreme Court, hoped that the Court majority would adopt a position on securities issues consistent with Brandeis’, instead of the conservative majority’s, argument.

As the SEC’s cases moved through the appeals process, the agency searched for one to test the constitutionality of the Securities Acts. It believed it had found its case in Jones v. SEC. Jones, an issuer of stock under the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, filed a registration statement with the SEC stating his intent to offer stock for sale. SEC staff members questioned the accuracy and completeness of the statement, issued a stop order, and subpoenaed records of Jones regarding the statement. Before the hearing, Jones withdrew his registration and refused to proffer the subpoenaed records, insisting that he could voluntarily withdraw the statement and effectively deny the SEC’s continuing jurisdiction and the constitutionality of the federal acts. The SEC, cognizant of this challenge to their investigative powers, appealed.

The Supreme Court, with Justice George Sutherland writing the opinion, disagreed with the SEC. Sutherland analogized that the SEC, as an administrative agency, had the same power of a court to order that Jones appear and give testimony, but it could do so only if the SEC was acting “in the public interest and for the protection of investors.” Since the sale of the stock had been withdrawn, and therefore there was no threat to the public or potential investors, Sutherland and his six-justice majority found that the SEC had acted beyond the scope of their authority. Their ruling compared the agency to the infamous “star-chamber” of English history.

Justices Brandeis, Harlan Stone and Benjamin Cardozo dissented. “Recklessness and deceit,” wrote Cardozo, “do not automatically excuse themselves by notice of repentance.” The dissenters believed that the misrepresentations made by Jones in the registration statement vested the right and power of the SEC to investigate and, if necessary, prosecute any violations. After losing the first case the agency appealed to the Supreme Court, the SEC faced a restricted interpretation of its powers that, if successful, could undermine the agency’s ability to investigate and prosecute wrongdoing.

Link to article and footnotes: http://www.sechistorical.org/museum/g...

More:

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

Source: Securities and Exchange Commission Historical Society

A New Era Unfolds: The Four Horsemen and Jones v. SEC

February 25, 1937 The Last Fortress

Yet the path for a new regime of regulation was not easy. The Supreme Court, with four conservative justices -- Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland, and Willis Van Devanter -- continued to decide cases based on the substantive due process protection of contractual and property rights. They often convinced one or more fellow justices to form a majority to defeat new attempts at property regulation. As New Deal laws regulating business came before the Supreme Court, the conservative majority, protecting property rights, struck many of them down as unconstitutional violations of the delegation powers or the interstate commerce clause. The conservative four at the heart of these denials came to be referred in apocryphal admonition as the “Four Horsemen.”

These actions posed immense problems for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which sought to use its broad statutory authority to regulate individual and company property rights in every state of the nation. Facing this dilemma, the SEC deftly moved cases of its own choosing to the Court with arguments they hoped would reverse the Court’s anti-New Deal and anti-regulatory majority.

The SEC found intellectual support in Justice Louis Brandeis’ dissent in the 1933 case of Liggett v Lee, in which Brandeis, realizing the effect of the conservative majority philosophy on increased administrative regulations, attempted to reformulate the argument. The case involved a Florida attempt to tax chain stores, generally constituted by larger national retail chains, in a greater amount than individual, locally-owned stores. The chain stores challenged the regulation as arbitrary and unreasonable, and thus unconstitutional. Justice Owen Roberts, writing for the conservative majority, agreed with the chain stores that the state regulation was unconstitutional.

Justice Brandeis dissented, arguing that the legislative goal of “protecting the individual, independently-owned, retail stores from the competition of chain stores” was valid. He argued that Florida was regulating corporations in intrastate commerce, and that the state had acted entirely within its powers. “Limitations upon the scope of a business corporation’s powers and activity were …universal,” and thus, “the difference in power between corporations and natural persons is ample basis for placing them in different classes.” Brandeis wanted to show that the power of huge national corporations, which he believed controlled and mismanaged much of the reeling economy, should be a proper constitutional basis for regulation. Proponents of New Deal administrative regulatory reform cheered. The SEC, arguing cases in lower courts as they made their way to the Supreme Court, hoped that the Court majority would adopt a position on securities issues consistent with Brandeis’, instead of the conservative majority’s, argument.

As the SEC’s cases moved through the appeals process, the agency searched for one to test the constitutionality of the Securities Acts. It believed it had found its case in Jones v. SEC. Jones, an issuer of stock under the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, filed a registration statement with the SEC stating his intent to offer stock for sale. SEC staff members questioned the accuracy and completeness of the statement, issued a stop order, and subpoenaed records of Jones regarding the statement. Before the hearing, Jones withdrew his registration and refused to proffer the subpoenaed records, insisting that he could voluntarily withdraw the statement and effectively deny the SEC’s continuing jurisdiction and the constitutionality of the federal acts. The SEC, cognizant of this challenge to their investigative powers, appealed.

The Supreme Court, with Justice George Sutherland writing the opinion, disagreed with the SEC. Sutherland analogized that the SEC, as an administrative agency, had the same power of a court to order that Jones appear and give testimony, but it could do so only if the SEC was acting “in the public interest and for the protection of investors.” Since the sale of the stock had been withdrawn, and therefore there was no threat to the public or potential investors, Sutherland and his six-justice majority found that the SEC had acted beyond the scope of their authority. Their ruling compared the agency to the infamous “star-chamber” of English history.

Justices Brandeis, Harlan Stone and Benjamin Cardozo dissented. “Recklessness and deceit,” wrote Cardozo, “do not automatically excuse themselves by notice of repentance.” The dissenters believed that the misrepresentations made by Jones in the registration statement vested the right and power of the SEC to investigate and, if necessary, prosecute any violations. After losing the first case the agency appealed to the Supreme Court, the SEC faced a restricted interpretation of its powers that, if successful, could undermine the agency’s ability to investigate and prosecute wrongdoing.

Link to article and footnotes: http://www.sechistorical.org/museum/g...

More:

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Burt Solomon (no photo)Source: Securities and Exchange Commission Historical Society

Books mentioned in this topic

FDR v. The Constitution: The Court-Packing Fight and the Triumph of Democracy (other topics)Supreme Power: Franklin Roosevelt vs. the Supreme Court (other topics)

Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1940 (other topics)

Closed Chambers: The Rise, Fall, and Future of the Modern Supreme Court (other topics)

Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Supreme Court (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Burt Solomon (other topics)Jeff Shesol (other topics)

William E. Leuchtenburg (other topics)

Edward Lazarus (other topics)

Artemus Ward (other topics)

More...

Biography

George Sutherland was born in England but raised in Utah where he later practiced law and achieved a measure of Republican political prominence. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives and in the Senate. Sutherland was a confidant of Warren Harding when he ran for the presidency. Harding later nominated him to the Supreme Court. While in private practice, Sutherland articulated a fundamentally conservative position on the role of government. His vision did not change on the Court.

Sutherland offered his vote and voice in support of substantive due process and other judicial barriers to state government regulation and control. Much of this approach was rejected by subsequent Courts.

Sutherland was not a cipher, however. He left his mark on other domains including the law of "standing" and the constitutional constraints governing foreign relations. Sutherland also forged an important link in the nationalization of the Bill of Rights by articulating the steps states must take to assure the right to counsel in capital cases.

Personal Information

Born Tuesday, March 25, 1862

Died Saturday, July 18, 1942

Childhood Location England

Childhood Surroundings England

Position Associate Justice

Seat 7

Nominated By Harding

Commissioned on Tuesday, September 5, 1922

Sworn In Monday, October 2, 1922

Left Office Monday, January 17, 1938

Reason For Leaving Retired

Length of Service 15 years, 3 months, 15 days

Home Utah

Source: http://www.oyez.org/justices/george_s...