The History Book Club discussion

SUPREME COURT OF THE U.S.

>

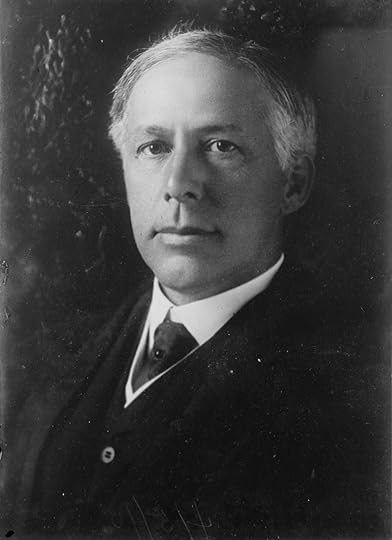

#63 - ASSOCIATE JUSTICE WILLIS VAN DEVANTER

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Willis Van Devanter (April 17, 1859 – February 8, 1941) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, January 3, 1911 to June 2, 1937.

Willis Van Devanter (April 17, 1859 – February 8, 1941) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, January 3, 1911 to June 2, 1937.Early life and career

Born in Marion, Indiana, he received a LL.B. from the Cincinnati Law School in 1881. He was a member of the Beta Theta Pi fraternity and the Knights of Pythias. After three years private practice in Marion, he moved to the Wyoming Territory where he served as city attorney of Cheyenne, Wyoming and a member of the territorial legislature. At the age of 30, he was appointed chief judge of the territorial court. Upon statehood, he served as Chief Justice of the Wyoming Supreme Court for four days, and again took up private practice for seven years, including much work for the Union Pacific and other railroads.

In 1896 he represented the state of Wyoming before the U.S. Supreme Court in Ward v. Race Horse 163 U.S. 504 (1896). At issue was a state poaching charge for hunting out of season, and its purported conflict with an Indian treaty that allowed the activity. The Native Americans won in the U.S. Federal District Court; the judgment was revised on appeal to the Supreme Court by a 7-1 majority.

In the summer and fall of 1896, Van Devanter was afflicted with typhoid fever.[3] From 1896 to 1900 he served in Washington, D.C. as an assistant attorney general, working in the Department of Interior. He was also a professor at The George Washington University Law School from 1897 to 1903.

Federal judicial service

On February 4, 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt nominated Van Devanter to a seat on the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals created by 32 Stat. 791. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on February 18, 1903, and received his commission the same day.

In 1910, William Howard Taft elevated him to the Supreme Court. Taft nominated Van Devanter on December 12, 1910 to the Associate Justice seat vacated by Edward D. White. Three days later, Van Devanter was confirmed by the United States Senate on December 15, 1910,[2] and received his commission the following day. Van Devanter assumed senior status on June 2, 1937, one of the first Supreme Court Justices to do so. Although no longer on the Court at that point, he technically remained available to hear cases until his death.

Supreme Court tenure

On the court, he made his mark in opinions on public lands, Indian questions, water rights, admiralty, jurisdiction, and corporate law, but is best remembered for his opinions defending limited government in the 1920s and 1930s. He served for over twenty-five years, and voted against the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (United States v. Butler), the National Recovery Administration (Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States), federal regulation of labor relations (National Labor Relations Board v. Jones and Laughlin Steel Corp.), the Railway Pension Act (Railroad Retirement Board v. Alton Railroad), unemployment insurance (Steward Machine Co. v. Davis), and the minimum wage (West Coast Hotel v. Parrish). For his conservatism, he was known as one of the Four Horsemen, along with Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, and George Sutherland; the four would dominate the Supreme Court for over two decades.

Van Devanter had chronic writer's block -- even characterized as "pen paralysis" -- and, as a result, he wrote fewer opinions than any of his brethren, averaging three a term during his last decade on the Court. He rarely wrote on constitutional issues. However, he was widely respected as an expert on judicial procedure. He was largely responsible for the 1925 legislation that allowed the Supreme Court greater control over its own docket through the certiorari procedure.

Retirement and final years

Van Devanter retired as a Supreme Court Justice on May 18, 1937, after Congress voted full pay for justices over seventy who retired. He acknowledged that he might have retired five years earlier due to illness, if not for his concern about New Deal legislation, and that he depended upon his salary for sustenance. In 1932, five years prior to Van Devanter's retirement, Congress had halved Supreme Court pensions. Congress had temporarily restored them to full pay in February 1933, only to see them halved again the next month by the Economy Act. Van Devanter was replaced by Justice Hugo Black, appointed by Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

He died in Washington, D.C., and was buried there in Rock Creek Cemetery. His gravesite is marked by "a stark 'VAN DEVANTER' — nothing else" which tops the family plot. However, his grave does have his name and dates on the stone.

Van Devanter's personal and judicial papers are archived at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, where they are available for research.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willis_V...

Overruled: The Long War for Control of the U.S. Supreme Court

Overruled: The Long War for Control of the U.S. Supreme Court by Damon Root (no photo)

by Damon Root (no photo)Synopsis:

Should the Supreme Court defer to the will of the majority and uphold most democratically enacted laws? Or does the Constitution empower the Supreme Court to protect a broad range of individual rights from the reach of lawmakers? In this timely and provocative book, Damon Root traces the long war over judicial activism and judicial restraint from its beginnings in the bloody age of slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction to its central role in today’s blockbuster legal battles over gay rights, gun control, and health care reform.

It's a conflict that cuts across the political spectrum in surprising ways and makes for some unusual bedfellows. Judicial deference is not only a touchstone of the Progressive left, for example, it is also a philosophy adopted by many members of the modern right. Today’s growing camp of libertarians, however, has no patience with judicial restraint and little use for majority rule. They want the courts and judges to police the other branches of government, and expect Justices to strike down any state or federal law that infringes on their bold constitutional agenda of personal and economic freedom.

Overruled is the story of two competing visions, each one with its own take on what role the government and the courts should play in our society, a fundamental debate that goes to the very heart of our constitutional system.

Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Supreme Court

Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Supreme Court by

by

Artemus Ward, Christopher Brough (no photo), and Robert Arnold (no photo)

Artemus Ward, Christopher Brough (no photo), and Robert Arnold (no photo)Synopsis:

The US Supreme Court is an institution that operates almost totally behind closed doors. This book opens those doors by providing a comprehensive look at the justices, procedures, cases, and issues over the institution s more than 200-year history. The Court is a legal institution born from a highly politicized process. Modern justices time their departures to coincide with favorable administrations and the confirmation process has become a highly-charged political spectacle played out on television and in the national press.

Throughout its history, the Court has been at the center of the most important issues facing the nation: federalism, separation of powers, war, slavery, civil rights, and civil liberties. Through it all, the Court has generally, though not always, reflected the broad views of the American people as the justices decide the most vexing issues of the day. The Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Supreme Court covers its history through a chronology, an introductory essay, appendixes, and an extensive bibliography.

The dictionary section has over 700 cross-referenced entries on every justice, major case, issue, and process that comprises the Court s work. This book is an excellent access point for students, researchers, and anyone wanting to know more about the Supreme Court."

A Life in Red: A Story of Forbidden Love, the Great Depression, and the Communist Fight for a Black Nation in the Deep South

A Life in Red: A Story of Forbidden Love, the Great Depression, and the Communist Fight for a Black Nation in the Deep South by David Beasley (no photo)

by David Beasley (no photo)Synopsis:

A Life in Red reveals the true story of star-crossed lovers Herbert Newton, a black communist seeking the end of an oppressive America, and Jane Newton, the white daughter of a wealthy American Legion commander, and their part in the Depression-Era, communist fight for a black sovereign nation.

Justice of the Day - Willis Van Devanter

By JLGARZON1 January 3, 2015

Justice Willis Van Devanter

Today’s Justice of the Day is: WILLIS VAN DEVANTER. Justice Van Devanter took the Judicial Oath to officially join the Supreme Court of the United States on this day, January 3, in 1911.

Justice Van Devanter was born on April 17, 1859 in Marion, Indiana. He attended Cincinnati Law School (today called the University of Cincinnati College of Law), graduating with an LL.B. in 1881.

Immediately upon graduation, Justice Van Devanter entered private practice in his home town of Marion, working there until 1884, the year he started a three-year stint as a private attorney in Cheyenne, a city located in the then-Wyoming Territory, which later became the state from which he would be appointed to the SCUS; he also briefly sat on the Commission to Revise the Statutes of Wyoming Territory in 1886. He was City Attorney for Cheyenne from 1887 to 1888, the year he served as Territorial Representative for the Wyoming Territory. Justice Van Devanter began serving as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Wyoming Territory in 1889, and remained in that office until the following year (he also briefly became Chief Justice of the Wyoming Supreme Court upon that territory’s attainment of statehood 1890), when he returned to private practice in Cheyenne for seven years. He started work as an Assistant Attorney General for the United States Department of Interior in 1896, and was made a Professor at Columbia University School of Law the following year. Justice Van Devanter went on to continuously hold both positions before his 1903 appointment as a Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit by President Theodore Roosevelt, an office he held until his elevation to the SCUS.

Justice Van Devanter was nominated by President William Howard Taft on December 12, 1910, to a seat vacated by then-Associate Justice Edward Douglass White. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on December 15, and received his commission the following day. Justice Van Devanter served on the White, Taft, and Hughes Courts, and assumed senior status on June 2, 1937. His service was terminated on February 8, 1941, due to his death.

Justice Van Devanter was not a particularly prolific writer while on the bench, and today is most famous for having been one of the Four Horseman, a group of Justices whose conservative views – and opposition to the New Deal in particular – came to dominate the SCUS throughout the 1920’s and early 1930’s. It was his retirement and subsequent replacement by the emphatically pro-New Deal Justice Hugo Black that most clearly signaled the end of the Four Horseman’s conservatism.

Other:

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)

Source: Daily Kos

By JLGARZON1 January 3, 2015

Justice Willis Van Devanter

Today’s Justice of the Day is: WILLIS VAN DEVANTER. Justice Van Devanter took the Judicial Oath to officially join the Supreme Court of the United States on this day, January 3, in 1911.

Justice Van Devanter was born on April 17, 1859 in Marion, Indiana. He attended Cincinnati Law School (today called the University of Cincinnati College of Law), graduating with an LL.B. in 1881.

Immediately upon graduation, Justice Van Devanter entered private practice in his home town of Marion, working there until 1884, the year he started a three-year stint as a private attorney in Cheyenne, a city located in the then-Wyoming Territory, which later became the state from which he would be appointed to the SCUS; he also briefly sat on the Commission to Revise the Statutes of Wyoming Territory in 1886. He was City Attorney for Cheyenne from 1887 to 1888, the year he served as Territorial Representative for the Wyoming Territory. Justice Van Devanter began serving as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Wyoming Territory in 1889, and remained in that office until the following year (he also briefly became Chief Justice of the Wyoming Supreme Court upon that territory’s attainment of statehood 1890), when he returned to private practice in Cheyenne for seven years. He started work as an Assistant Attorney General for the United States Department of Interior in 1896, and was made a Professor at Columbia University School of Law the following year. Justice Van Devanter went on to continuously hold both positions before his 1903 appointment as a Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit by President Theodore Roosevelt, an office he held until his elevation to the SCUS.

Justice Van Devanter was nominated by President William Howard Taft on December 12, 1910, to a seat vacated by then-Associate Justice Edward Douglass White. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on December 15, and received his commission the following day. Justice Van Devanter served on the White, Taft, and Hughes Courts, and assumed senior status on June 2, 1937. His service was terminated on February 8, 1941, due to his death.

Justice Van Devanter was not a particularly prolific writer while on the bench, and today is most famous for having been one of the Four Horseman, a group of Justices whose conservative views – and opposition to the New Deal in particular – came to dominate the SCUS throughout the 1920’s and early 1930’s. It was his retirement and subsequent replacement by the emphatically pro-New Deal Justice Hugo Black that most clearly signaled the end of the Four Horseman’s conservatism.

Other:

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Burt Solomon (no photo) by Jeff Shesol (no photo)

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)Source: Daily Kos

FDR v. The Constitution: The Court-Packing Fight and the Triumph of Democracy

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

Synopsis:

The fascinating, behind-the-scenes story of Franklin Roosevelt's attempt to pack the Supreme Court has special resonance today as we debate the limits of presidential authority.

The Supreme Court has generated many dramatic stories, none more so than the one that began on February 5, 1937. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, confident in his recent landslide reelection and frustrated by a Court that had overturned much of his New Deal legislation, stunned Congress and the American people with his announced intention to add six new justices. Even though the now-famous "court packing" scheme divided his own party, almost everyone assumed FDR would get his way and reverse the Court's conservative stance and long-standing laissez-faire support of corporate America, so persuasive and powerful had he become. I n the end, however, a Supreme Court justice, Owen Roberts, who cast off precedent in the interests of principle, and a Democratic senator from Montana, Burton K. Wheeler, led an effort that turned an apparently unstoppable proposal into a humiliating rejection—and preserved the Constitution.

FDR v. Constitution is the colorful story behind 168 days that riveted—and reshaped—the nation. Burt Solomon skillfully recounts the major New Deal initiatives of FDR's first term and the rulings that overturned them, chronicling as well the politics and personalities on the Supreme Court—from the brilliant octogenarian Louis Brandeis, to the politically minded chief justice, Charles Evans Hughes, to the mercurial Roberts, whose "switch in time saved nine." T he ebb and flow of one of the momentous set pieces in American history placed the inner workings of the nation's capital on full view as the three branches of our government squared off.

Ironically for FDR, the Court that emerged from this struggle shifted on its own to a liberal attitude, where it would largely remain for another seven decades. Placing the greatest miscalculation of FDR's career in context past and present, Solomon offers a reminder of the perennial temptation toward an imperial presidency that the founders had always feared.

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Burt Solomon (no photo)Synopsis:

The fascinating, behind-the-scenes story of Franklin Roosevelt's attempt to pack the Supreme Court has special resonance today as we debate the limits of presidential authority.

The Supreme Court has generated many dramatic stories, none more so than the one that began on February 5, 1937. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, confident in his recent landslide reelection and frustrated by a Court that had overturned much of his New Deal legislation, stunned Congress and the American people with his announced intention to add six new justices. Even though the now-famous "court packing" scheme divided his own party, almost everyone assumed FDR would get his way and reverse the Court's conservative stance and long-standing laissez-faire support of corporate America, so persuasive and powerful had he become. I n the end, however, a Supreme Court justice, Owen Roberts, who cast off precedent in the interests of principle, and a Democratic senator from Montana, Burton K. Wheeler, led an effort that turned an apparently unstoppable proposal into a humiliating rejection—and preserved the Constitution.

FDR v. Constitution is the colorful story behind 168 days that riveted—and reshaped—the nation. Burt Solomon skillfully recounts the major New Deal initiatives of FDR's first term and the rulings that overturned them, chronicling as well the politics and personalities on the Supreme Court—from the brilliant octogenarian Louis Brandeis, to the politically minded chief justice, Charles Evans Hughes, to the mercurial Roberts, whose "switch in time saved nine." T he ebb and flow of one of the momentous set pieces in American history placed the inner workings of the nation's capital on full view as the three branches of our government squared off.

Ironically for FDR, the Court that emerged from this struggle shifted on its own to a liberal attitude, where it would largely remain for another seven decades. Placing the greatest miscalculation of FDR's career in context past and present, Solomon offers a reminder of the perennial temptation toward an imperial presidency that the founders had always feared.

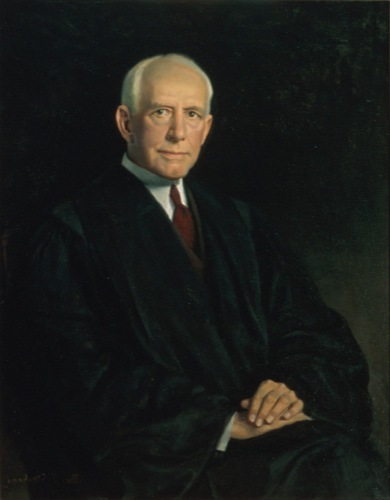

Willis Van Devanter

The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States (Artist: Thomas E. Stephens)

Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court - January 3, 1911 — June 2, 1937

Willis Van Devanter spent his early years in Indiana but headed to Wyoming Territory shortly after receiving his law degree. Van Devanter opened his law practice In Cheyenne and became active in Republican politics. For his efforts, President Benjamin Harrison appointed Van Devanter as chief justice of the Wyoming Territorial Supreme Court at the ripe old age of 30!

After a stint in Washington as an assistant attorney general, Van Devanter accepted President Theodore Roosevelt's nomination to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit. Seven years later, President William Howard Taft nominated Van Devanter to the Supreme Court. Van Devanter was afflicted with "pen paralysis." He rarely spoke for the Court in constitutional cases.

Other:

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

Source: Oyez

The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States (Artist: Thomas E. Stephens)

Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court - January 3, 1911 — June 2, 1937

Willis Van Devanter spent his early years in Indiana but headed to Wyoming Territory shortly after receiving his law degree. Van Devanter opened his law practice In Cheyenne and became active in Republican politics. For his efforts, President Benjamin Harrison appointed Van Devanter as chief justice of the Wyoming Territorial Supreme Court at the ripe old age of 30!

After a stint in Washington as an assistant attorney general, Van Devanter accepted President Theodore Roosevelt's nomination to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit. Seven years later, President William Howard Taft nominated Van Devanter to the Supreme Court. Van Devanter was afflicted with "pen paralysis." He rarely spoke for the Court in constitutional cases.

Other:

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Burt Solomon (no photo)Source: Oyez

Chasing the Devil Around the Stump: Securities Regulation, the SEC and the Courts

A New Era Unfolds: The Four Horsemen and Jones v. SEC

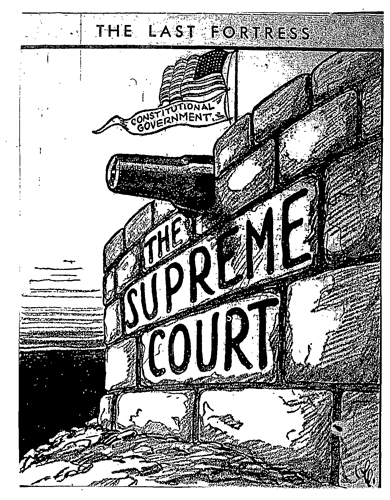

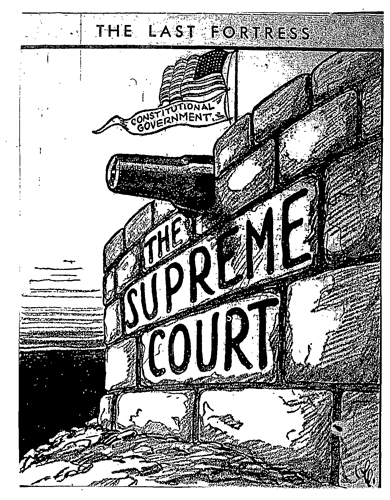

February 25, 1937 The Last Fortress

Yet the path for a new regime of regulation was not easy. The Supreme Court, with four conservative justices -- Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland, and Willis Van Devanter -- continued to decide cases based on the substantive due process protection of contractual and property rights. They often convinced one or more fellow justices to form a majority to defeat new attempts at property regulation. As New Deal laws regulating business came before the Supreme Court, the conservative majority, protecting property rights, struck many of them down as unconstitutional violations of the delegation powers or the interstate commerce clause. The conservative four at the heart of these denials came to be referred in apocryphal admonition as the “Four Horsemen.”

These actions posed immense problems for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which sought to use its broad statutory authority to regulate individual and company property rights in every state of the nation. Facing this dilemma, the SEC deftly moved cases of its own choosing to the Court with arguments they hoped would reverse the Court’s anti-New Deal and anti-regulatory majority.

The SEC found intellectual support in Justice Louis Brandeis’ dissent in the 1933 case of Liggett v Lee, in which Brandeis, realizing the effect of the conservative majority philosophy on increased administrative regulations, attempted to reformulate the argument. The case involved a Florida attempt to tax chain stores, generally constituted by larger national retail chains, in a greater amount than individual, locally-owned stores. The chain stores challenged the regulation as arbitrary and unreasonable, and thus unconstitutional. Justice Owen Roberts, writing for the conservative majority, agreed with the chain stores that the state regulation was unconstitutional.

Justice Brandeis dissented, arguing that the legislative goal of “protecting the individual, independently-owned, retail stores from the competition of chain stores” was valid. He argued that Florida was regulating corporations in intrastate commerce, and that the state had acted entirely within its powers. “Limitations upon the scope of a business corporation’s powers and activity were …universal,” and thus, “the difference in power between corporations and natural persons is ample basis for placing them in different classes.” Brandeis wanted to show that the power of huge national corporations, which he believed controlled and mismanaged much of the reeling economy, should be a proper constitutional basis for regulation. Proponents of New Deal administrative regulatory reform cheered. The SEC, arguing cases in lower courts as they made their way to the Supreme Court, hoped that the Court majority would adopt a position on securities issues consistent with Brandeis’, instead of the conservative majority’s, argument.

As the SEC’s cases moved through the appeals process, the agency searched for one to test the constitutionality of the Securities Acts. It believed it had found its case in Jones v. SEC. Jones, an issuer of stock under the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, filed a registration statement with the SEC stating his intent to offer stock for sale. SEC staff members questioned the accuracy and completeness of the statement, issued a stop order, and subpoenaed records of Jones regarding the statement. Before the hearing, Jones withdrew his registration and refused to proffer the subpoenaed records, insisting that he could voluntarily withdraw the statement and effectively deny the SEC’s continuing jurisdiction and the constitutionality of the federal acts. The SEC, cognizant of this challenge to their investigative powers, appealed.

The Supreme Court, with Justice George Sutherland writing the opinion, disagreed with the SEC. Sutherland analogized that the SEC, as an administrative agency, had the same power of a court to order that Jones appear and give testimony, but it could do so only if the SEC was acting “in the public interest and for the protection of investors.” Since the sale of the stock had been withdrawn, and therefore there was no threat to the public or potential investors, Sutherland and his six-justice majority found that the SEC had acted beyond the scope of their authority. Their ruling compared the agency to the infamous “star-chamber” of English history.

Justices Brandeis, Harlan Stone and Benjamin Cardozo dissented. “Recklessness and deceit,” wrote Cardozo, “do not automatically excuse themselves by notice of repentance.” The dissenters believed that the misrepresentations made by Jones in the registration statement vested the right and power of the SEC to investigate and, if necessary, prosecute any violations. After losing the first case the agency appealed to the Supreme Court, the SEC faced a restricted interpretation of its powers that, if successful, could undermine the agency’s ability to investigate and prosecute wrongdoing.

Link to article and footnotes: http://www.sechistorical.org/museum/g...

More:

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

Source: Securities and Exchange Commission Historical Society

A New Era Unfolds: The Four Horsemen and Jones v. SEC

February 25, 1937 The Last Fortress

Yet the path for a new regime of regulation was not easy. The Supreme Court, with four conservative justices -- Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland, and Willis Van Devanter -- continued to decide cases based on the substantive due process protection of contractual and property rights. They often convinced one or more fellow justices to form a majority to defeat new attempts at property regulation. As New Deal laws regulating business came before the Supreme Court, the conservative majority, protecting property rights, struck many of them down as unconstitutional violations of the delegation powers or the interstate commerce clause. The conservative four at the heart of these denials came to be referred in apocryphal admonition as the “Four Horsemen.”

These actions posed immense problems for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which sought to use its broad statutory authority to regulate individual and company property rights in every state of the nation. Facing this dilemma, the SEC deftly moved cases of its own choosing to the Court with arguments they hoped would reverse the Court’s anti-New Deal and anti-regulatory majority.

The SEC found intellectual support in Justice Louis Brandeis’ dissent in the 1933 case of Liggett v Lee, in which Brandeis, realizing the effect of the conservative majority philosophy on increased administrative regulations, attempted to reformulate the argument. The case involved a Florida attempt to tax chain stores, generally constituted by larger national retail chains, in a greater amount than individual, locally-owned stores. The chain stores challenged the regulation as arbitrary and unreasonable, and thus unconstitutional. Justice Owen Roberts, writing for the conservative majority, agreed with the chain stores that the state regulation was unconstitutional.

Justice Brandeis dissented, arguing that the legislative goal of “protecting the individual, independently-owned, retail stores from the competition of chain stores” was valid. He argued that Florida was regulating corporations in intrastate commerce, and that the state had acted entirely within its powers. “Limitations upon the scope of a business corporation’s powers and activity were …universal,” and thus, “the difference in power between corporations and natural persons is ample basis for placing them in different classes.” Brandeis wanted to show that the power of huge national corporations, which he believed controlled and mismanaged much of the reeling economy, should be a proper constitutional basis for regulation. Proponents of New Deal administrative regulatory reform cheered. The SEC, arguing cases in lower courts as they made their way to the Supreme Court, hoped that the Court majority would adopt a position on securities issues consistent with Brandeis’, instead of the conservative majority’s, argument.

As the SEC’s cases moved through the appeals process, the agency searched for one to test the constitutionality of the Securities Acts. It believed it had found its case in Jones v. SEC. Jones, an issuer of stock under the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, filed a registration statement with the SEC stating his intent to offer stock for sale. SEC staff members questioned the accuracy and completeness of the statement, issued a stop order, and subpoenaed records of Jones regarding the statement. Before the hearing, Jones withdrew his registration and refused to proffer the subpoenaed records, insisting that he could voluntarily withdraw the statement and effectively deny the SEC’s continuing jurisdiction and the constitutionality of the federal acts. The SEC, cognizant of this challenge to their investigative powers, appealed.

The Supreme Court, with Justice George Sutherland writing the opinion, disagreed with the SEC. Sutherland analogized that the SEC, as an administrative agency, had the same power of a court to order that Jones appear and give testimony, but it could do so only if the SEC was acting “in the public interest and for the protection of investors.” Since the sale of the stock had been withdrawn, and therefore there was no threat to the public or potential investors, Sutherland and his six-justice majority found that the SEC had acted beyond the scope of their authority. Their ruling compared the agency to the infamous “star-chamber” of English history.

Justices Brandeis, Harlan Stone and Benjamin Cardozo dissented. “Recklessness and deceit,” wrote Cardozo, “do not automatically excuse themselves by notice of repentance.” The dissenters believed that the misrepresentations made by Jones in the registration statement vested the right and power of the SEC to investigate and, if necessary, prosecute any violations. After losing the first case the agency appealed to the Supreme Court, the SEC faced a restricted interpretation of its powers that, if successful, could undermine the agency’s ability to investigate and prosecute wrongdoing.

Link to article and footnotes: http://www.sechistorical.org/museum/g...

More:

by Burt Solomon (no photo)

by Burt Solomon (no photo)Source: Securities and Exchange Commission Historical Society

Books mentioned in this topic

FDR v. The Constitution: The Court-Packing Fight and the Triumph of Democracy (other topics)FDR v. The Constitution: The Court-Packing Fight and the Triumph of Democracy (other topics)

FDR v. The Constitution: The Court-Packing Fight and the Triumph of Democracy (other topics)

FDR v. The Constitution: The Court-Packing Fight and the Triumph of Democracy (other topics)

Supreme Power: Franklin Roosevelt vs. the Supreme Court (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Burt Solomon (other topics)Burt Solomon (other topics)

Burt Solomon (other topics)

Jeff Shesol (other topics)

Burt Solomon (other topics)

More...

Biography

Willis Van Devanter spent his early years in Indiana but headed to Wyoming Territory shortly after receiving his law degree. Van Devanter opened his law practice In Cheyenne and became active in Republican politics. For his efforts, President Benjamin Harrison appointed Van Devanter as chief justice of the Wyoming Territorial Supreme Court at the ripe old age of 30!

After a stint in Washington as an assistant attorney general, Van Devanter accepted President Theodore Roosevelt's nomination to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit. Seven years later, President William Howard Taft nominated Van Devanter to the Supreme Court. Van Devanter was afflicted with "pen paralysis." He rarely spoke for the Court in constitutional cases.

Personal Information

Born Sunday, April 17, 1859

Died Saturday, February 8, 1941

Childhood Location Indiana

Childhood Surroundings Indiana

Position Associate Justice

Seat 2

Nominated By Taft

Commissioned on Friday, December 16, 1910

Sworn In Tuesday, January 3, 1911

Left Office Wednesday, June 2, 1937

Reason For Leaving Retired

Length of Service 26 years, 4 months, 30 days

Home Wyoming

Source: http://www.oyez.org/justices/willis_v...