Divine Comedy + Decameron discussion

This topic is about

The Decameron

Boccaccio's Decameron

>

9/1-9/7: Seventh Day, Stories 6-10 & Conclusion

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Kris

(new)

-

added it

Apr 14, 2014 09:34AM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

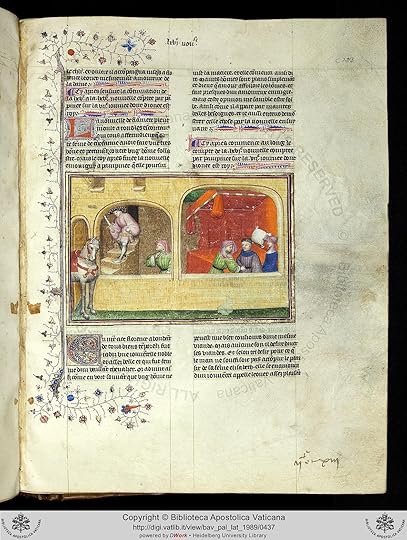

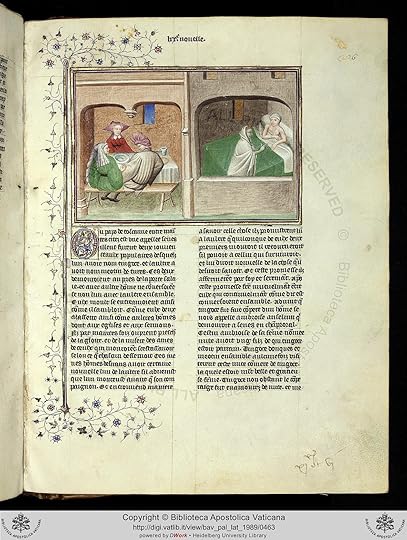

Illustrations - Day VII Story 6

Illustrations - Day VII Story 6

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Lambertuccio & le mari trompé

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

{I'm on a roll so I'll post next week too. ^^}

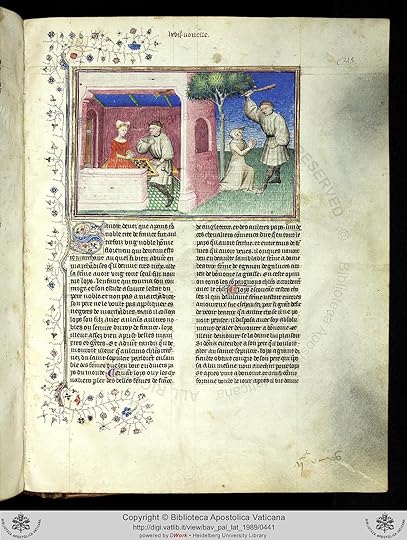

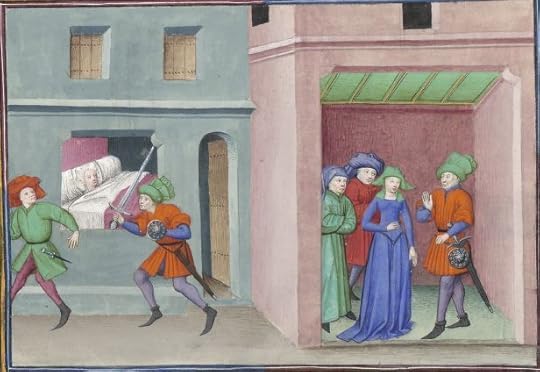

Illustrations - Day VII Story 7

Illustrations - Day VII Story 7

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Anichino & Beatrice devant un jeu d'échecs

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

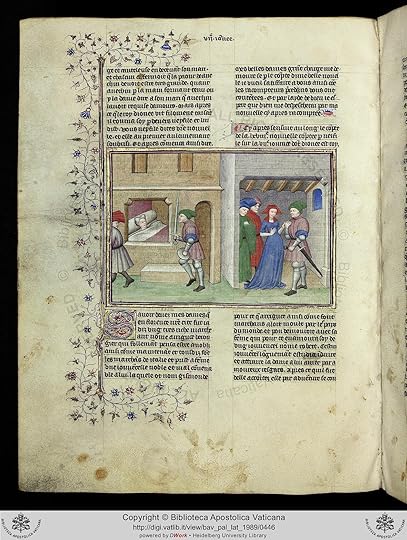

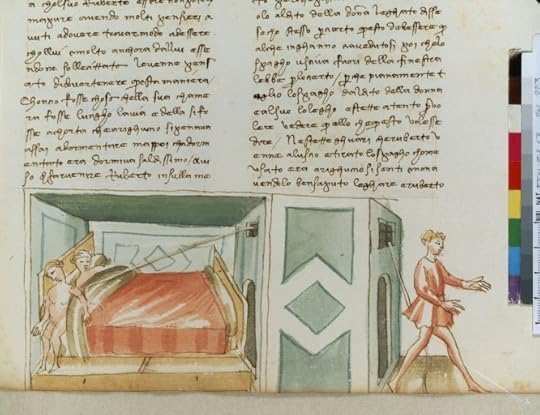

Illustrations - Day VII Story 8

Illustrations - Day VII Story 8

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Arriguccio découvrant la ruse de Ruberto et Sismonda

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

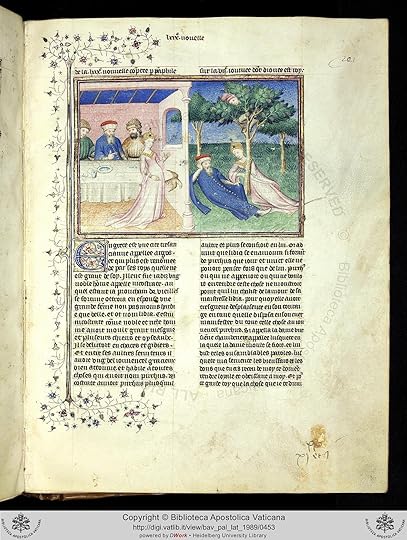

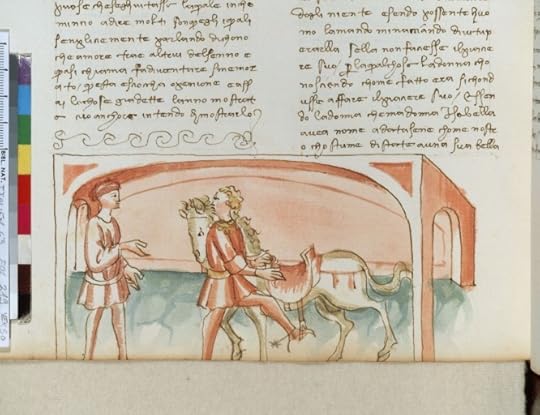

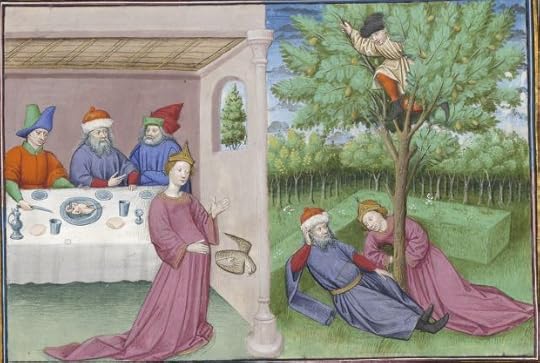

Illustrations - Day VII Story 9

Illustrations - Day VII Story 9

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Nicostrate abusé par sa femme Lydia

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Illustrations - Day VII Story 10

Illustrations - Day VII Story 10

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Tingoccio Mini réveillant Meuccio

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Book Portrait, your illustrations are always so delightful. Thank you :)

Sixth tale (VII, 6)

Pampinea narrates this version of a common medieval tale which originates from the Hitopadesha of India. Later versions pass the tale into Persian, French, Latin (in The Seven Wise Masters), and Hebrew.

Hitopadesha (Sanskrit:हितोपदेशः Hitopadeśa) is a collection of Sanskrit fables in prose and verse meant as an exposition on statecraft in a format easily digestible for young princes. It is an independent treatment of the Panchatantra, which it resembles in form.

Sixth tale (VII, 6)

Pampinea narrates this version of a common medieval tale which originates from the Hitopadesha of India. Later versions pass the tale into Persian, French, Latin (in The Seven Wise Masters), and Hebrew.

Hitopadesha (Sanskrit:हितोपदेशः Hitopadeśa) is a collection of Sanskrit fables in prose and verse meant as an exposition on statecraft in a format easily digestible for young princes. It is an independent treatment of the Panchatantra, which it resembles in form.

Ninth tale (VII, 9)

Panfilo narrates. Boccaccio combined two earlier folk tales into one to create this story. The test of fidelity is previously recorded in French (a fabliau) and Latin (Lidia, an elegiac comedy), but comes originally from India or Persia. The story of the pear tree, best known to English speaking readers from The Canterbury Tales, also originates from Persia in the Bahar-Danush, in which the husband climbs a date tree instead of a pear tree. The story could have arrived in Europe through the One Thousand and One Nights, or perhaps the version in book VI of the Masnavi by Rumi.

Panfilo narrates. Boccaccio combined two earlier folk tales into one to create this story. The test of fidelity is previously recorded in French (a fabliau) and Latin (Lidia, an elegiac comedy), but comes originally from India or Persia. The story of the pear tree, best known to English speaking readers from The Canterbury Tales, also originates from Persia in the Bahar-Danush, in which the husband climbs a date tree instead of a pear tree. The story could have arrived in Europe through the One Thousand and One Nights, or perhaps the version in book VI of the Masnavi by Rumi.

Dioneo

During the seventh day Dioneo serves as king of the brigata and sets the theme for the stories: tales in which wives play tricks on their husbands. Stories of this type are typical of the misogynistic sentiment of the Medieval era. However, in many of the stories the wives are portrayed as more intelligent and clever than their husbands. Though Boccaccio portrays many of the women of these stories in a positive light, most of the men in the stories are stereotypical medieval/Renaissance cuckolds.

In his introduction to I.4, the first story he tells, Dioneo expresses the opinion "that each must be allowed [...] to tell whatever story we think most likely to amuse." Consequently he will be granted the privilege not to follow the theme of the day and to tell instead the story that most pleases him, regardless of its consonance or dissonance with the others told in that day. In exchange, he will be the last of the ten narrators to tell a story. This positioning is significant because it is meant not to interfere with the pattern developed in a given day; on the contrary, Dioneo's privilege grants him a role of transgressor while at the same time, as an exception, reinforces the (narrative) rule that governs the Decameron.

Dioneo as Transgressor

Within the space of their paradisiac seclusion from reality, death and disease, Dioneo reminds the brigata of their mortality, their humanity in the face of stronger forces. His manner of narration is forthright and clear, as is his language. The puns he uses resonate immediately with the rest of the company because they refer to situations and feelings they can recognize in their own experience; indeed they are common to all human experience. Dioneo has an incredibly strong command of language in communicating with exact intention - he can do so without thought, "naturally," while the other members of the troupe are most recognizably self-aware of themselves in the position of narrator. For this reason, one could argue that Dioneo is, in actuality, the ruling narrator of the Decameron, disguising - and at the same time revealing - this role through his position each day as the final narrator. That he holds the greatest power becomes clear by way of his effective and confident storytelling.

Dioneo is the personification of freedom. He is an anarchic figure, though not an extremist. We should not forget the "urbanity" of the Decameron, and the crucial importance of social interaction among the members of the brigata. Absolute lack of conformity and compromise would mean for Dioneo isolation, as any social interaction requires some degree of conformity to or acceptance of the rules. Although he represents the "pleasure principle," Dioneo is also the embodiment of a social necessity, he is an integral part of the brigata' s "utopian" society. His narration - unfettered as it is by the thematic constraints imposed upon the others - could fairly be seen as a metaphor for a sort of "liberation of the repressed" within the framework of the Decameron, a safety valve for the frustrations and anxiety of his society at large.

Dioneo as King

Boccaccio's assignment of Dioneo as the ruler of the seventh day is significant because Dioneo represents a transgressive, though salubrious, spirit within the infinite potentiality of language. The infinite play in which literature engages mirrors an arabesque, or spiral, which regenerates itself in a constant re-centering, changing of balance, and movement in an infinite number of possible directions. The number seven signifies a chaotic tendency, transformation which is continuous and incomplete. The Thousand and One Nights imitates this process. This chaotic and disruptive tendency is echoed by the topic dictated by Dioneo for this day (the imposal of a theme notably runs counter to his own privilege): that of tricks played by women on their husbands, the ultimate transgression within patriarchal society. Trickery is characteristic of narration itself - an endeavor of which Dioneo is undoubtedly a master.

Dioneo's Stories - General Comments

Dioneo is the ideal lover, a verbal Don Juan in the world of the Decameron (the man who loves to please women, the work's self-proclaimed implied readers). That he might represent Boccaccio's view of "natural" love is demonstrated by his song at the end of the fifth day. Indeed, his is the most sincere love song yet sung in the Decameron.

During the seventh day Dioneo serves as king of the brigata and sets the theme for the stories: tales in which wives play tricks on their husbands. Stories of this type are typical of the misogynistic sentiment of the Medieval era. However, in many of the stories the wives are portrayed as more intelligent and clever than their husbands. Though Boccaccio portrays many of the women of these stories in a positive light, most of the men in the stories are stereotypical medieval/Renaissance cuckolds.

In his introduction to I.4, the first story he tells, Dioneo expresses the opinion "that each must be allowed [...] to tell whatever story we think most likely to amuse." Consequently he will be granted the privilege not to follow the theme of the day and to tell instead the story that most pleases him, regardless of its consonance or dissonance with the others told in that day. In exchange, he will be the last of the ten narrators to tell a story. This positioning is significant because it is meant not to interfere with the pattern developed in a given day; on the contrary, Dioneo's privilege grants him a role of transgressor while at the same time, as an exception, reinforces the (narrative) rule that governs the Decameron.

Dioneo as Transgressor

Within the space of their paradisiac seclusion from reality, death and disease, Dioneo reminds the brigata of their mortality, their humanity in the face of stronger forces. His manner of narration is forthright and clear, as is his language. The puns he uses resonate immediately with the rest of the company because they refer to situations and feelings they can recognize in their own experience; indeed they are common to all human experience. Dioneo has an incredibly strong command of language in communicating with exact intention - he can do so without thought, "naturally," while the other members of the troupe are most recognizably self-aware of themselves in the position of narrator. For this reason, one could argue that Dioneo is, in actuality, the ruling narrator of the Decameron, disguising - and at the same time revealing - this role through his position each day as the final narrator. That he holds the greatest power becomes clear by way of his effective and confident storytelling.

Dioneo is the personification of freedom. He is an anarchic figure, though not an extremist. We should not forget the "urbanity" of the Decameron, and the crucial importance of social interaction among the members of the brigata. Absolute lack of conformity and compromise would mean for Dioneo isolation, as any social interaction requires some degree of conformity to or acceptance of the rules. Although he represents the "pleasure principle," Dioneo is also the embodiment of a social necessity, he is an integral part of the brigata' s "utopian" society. His narration - unfettered as it is by the thematic constraints imposed upon the others - could fairly be seen as a metaphor for a sort of "liberation of the repressed" within the framework of the Decameron, a safety valve for the frustrations and anxiety of his society at large.

Dioneo as King

Boccaccio's assignment of Dioneo as the ruler of the seventh day is significant because Dioneo represents a transgressive, though salubrious, spirit within the infinite potentiality of language. The infinite play in which literature engages mirrors an arabesque, or spiral, which regenerates itself in a constant re-centering, changing of balance, and movement in an infinite number of possible directions. The number seven signifies a chaotic tendency, transformation which is continuous and incomplete. The Thousand and One Nights imitates this process. This chaotic and disruptive tendency is echoed by the topic dictated by Dioneo for this day (the imposal of a theme notably runs counter to his own privilege): that of tricks played by women on their husbands, the ultimate transgression within patriarchal society. Trickery is characteristic of narration itself - an endeavor of which Dioneo is undoubtedly a master.

Dioneo's Stories - General Comments

Dioneo is the ideal lover, a verbal Don Juan in the world of the Decameron (the man who loves to please women, the work's self-proclaimed implied readers). That he might represent Boccaccio's view of "natural" love is demonstrated by his song at the end of the fifth day. Indeed, his is the most sincere love song yet sung in the Decameron.

The Seventh day of the Decameron, Poole, Paul Falconer (1807-79) / Private Collection / Roy Miles Fine Paintings / The Bridgeman Art Library

Toto wrote: "Frankly I'm getting bleary eyed reading these sex-capades. But I do love the language of the gardens at the end of each day -- as Falconer's painting tries to capture. If I had time I would compar..."

Toto wrote: "Frankly I'm getting bleary eyed reading these sex-capades. But I do love the language of the gardens at the end of each day -- as Falconer's painting tries to capture. If I had time I would compar..."Payne's says, Accordingly, the all, ladies and men alike, arose and some began to go barefoot through the clear water, whilst others went a-pleasuring upon the greensward among the straight and goodly trees." I'm not sure whether that's better or not....there are some interesting choices for words there, but I'm not certain as to whether they're Bocaccio's or Payne's.