Divine Comedy + Decameron discussion

Boccaccio's Decameron

>

8/18-8/24: Sixth Day, Stories 6-10 & Conclusion

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Kris

(new)

Apr 14, 2014 09:36AM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

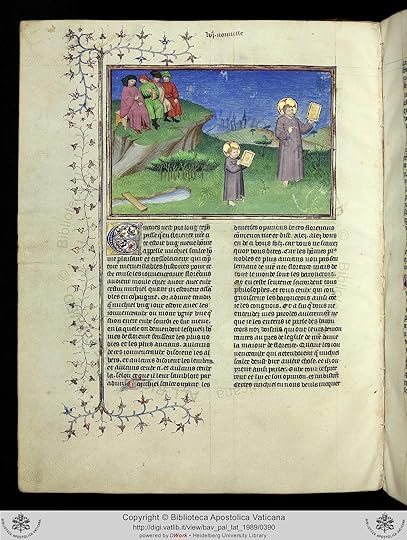

Illustrations - Day VI Story 6

Illustrations - Day VI Story 6

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Michele Scalza & les jeunes gens

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

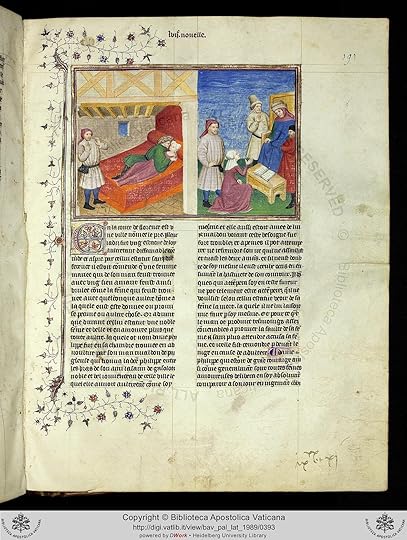

Illustrations - Day VI Story 7

Illustrations - Day VI Story 7

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Filippa de'Pugliesi devant le juge

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

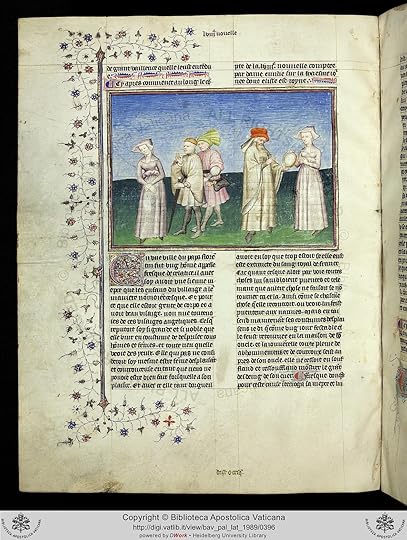

Illustrations - Day VI Story 8

Illustrations - Day VI Story 8

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Cesca da Celatico & son oncle

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

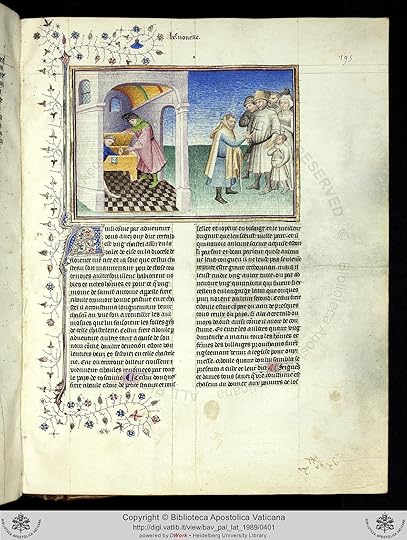

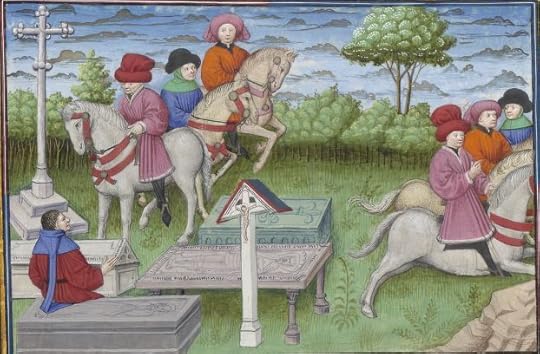

Illustrations - Day VI Story 9

Illustrations - Day VI Story 9

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Guido Cavalcanti au cimetière

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Illustrations - Day VI Story 10

Illustrations - Day VI Story 10

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Cipolla trompant les fidèles

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Thank you BP. All your art work contributions inspired a search that may be of interest to Kalli as she prepares for her trip to Florence:

Visualizing the Text: the Cassoni stories

Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron, written in the Tuscan vernacular between 1348 to 1350, was a major source for Florentine cassoni paintings of the late fourteenth century and the first decades of the fifteenth century. The explanations for this phenomenon are many. The Decameron was accessible to readers of all social classes, and was a part of a body of literature that would have been familiar to all educated Florentines. Other works by Boccaccio, particularly his Genealogia deorum, De casibus virorum illustrium, and De mulieribus claris, made ancient history and mythology accessible to a wider audience than that of texts from the classical period. These works are considered to have contributed to the revival of ancient subject matter in literature and the visual arts that took place in the fifteenth century. It is ironic that it was precisely this surge of interest in classical imagery and stories that led to a decrease in the number of cassoni panels depicting scenes from the Decameron.1

The stories of the Decameron deal with themes, characters, and locations that would have been familiar to readers even a century after its writing. The explicit way in which Boccaccio addressed the issues of marriage, love and adultery make many of the Decameron's stories apt selections for the decoration of marriage chests. It is no coincidence that the stories of Griselda (X.10) and Nastagio degli Onesti (V,8), which appear most frequently on cassoni and spalliera panels, highlight the necessity of a woman's obedience, virtue and chastity. The moral message of these scenes is in keeping with the didactic role of cassoni as teachers decorated with stories intended to inspire newly married couples, particularly young brides, to abide by a strict moral code. Depictions of Boccaccio's many playful stories featuring adulterous relationships are conspicuously absent from the body of fifteenth century secular paintings.

Nearly all of the stories that appeared on cassoni end happily and illustrate aspects of the moral code to which women in the Renaissance were expected to conform. Much as paintings of religious subjects illustrated biblical stories, cassoni depicting scenes from the Decameron would have served as textual illustrations to men and women reading the work in the privacy of their own bedchamber. Similarly, visual representations made stories accessible to those who were not well educated enough to read the textual sources.

Cassoni themselves are also narrative elements in several of Boccaccio's stories, most notably in the stories of Bernabò and Zinevra di Genova (II.9), Zeppa and Spinelloccio (VIII.8), the Abbess and the priest (IX.2) and the King of Spain and Messer Ruggieri (X.1).

Boccaccian Themes in Italian Secular Painting, 1400-1550

In surveying the available literature on imagery derived from Decameron themes, Paul F. Watson's "A Preliminary List of Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1400-1550" proved particularly illuminating. Despite the fact that more and more comprehensive compilations of "visualized" boccaccian themes are available each year, scholars still tend to restrict their examinations of visual renditions of certain tales to long available masterpieces. In doing so they disregard multitudes of images which shed light on Renaissance artists' exegetic attempts to interpret Boccaccio's text.

Three tales from the Decameron seem to have been particularly popular among Italian Renaissance painters, Cimone's story, the story of Griselda (X.10) and Nastagio degli Onesti (V.8). In the following excerpt from Watson's list we have included only those references which pertain to these themes. They constitute over thirty works of art out of approximately one hundred extant images of boccaccian content from the time period. The large proportion of artistic energy devoted to these three specific tales by the same author, or perhaps the favored preservation of these specific works by their patrons, points to some form of Renaissance fascination with the textual themes as they were rendered visually. Due to the preponderance of imagery surrounding these stories, it behooves the scholar interested in questioning image-text relationships to examine as many different visualizations as possible in order to arrive at a more comprehensive view of social and cultural attitudes toward the original text and its interpretation.

A selected bibliography of articles and books on Decameron visualizations has also been compiled for your reference, along with a list of Decameron related paintings by Italian artists between 1400 and 1550. Watson's list is divided into two parts, paintings by unknown masters and those by known artists.

Part 1: Paintings by Unknown Masters

Part 2: Paintings by Known Artists

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1.Callmann, Ellen. "Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1375-1525" Studi sul Boccaccio, Firenze: Sansoni Editore, 23 (1995):19-78. ↩

(S. A. & C. C.)

Visualizing the Text: the Cassoni stories

Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron, written in the Tuscan vernacular between 1348 to 1350, was a major source for Florentine cassoni paintings of the late fourteenth century and the first decades of the fifteenth century. The explanations for this phenomenon are many. The Decameron was accessible to readers of all social classes, and was a part of a body of literature that would have been familiar to all educated Florentines. Other works by Boccaccio, particularly his Genealogia deorum, De casibus virorum illustrium, and De mulieribus claris, made ancient history and mythology accessible to a wider audience than that of texts from the classical period. These works are considered to have contributed to the revival of ancient subject matter in literature and the visual arts that took place in the fifteenth century. It is ironic that it was precisely this surge of interest in classical imagery and stories that led to a decrease in the number of cassoni panels depicting scenes from the Decameron.1

The stories of the Decameron deal with themes, characters, and locations that would have been familiar to readers even a century after its writing. The explicit way in which Boccaccio addressed the issues of marriage, love and adultery make many of the Decameron's stories apt selections for the decoration of marriage chests. It is no coincidence that the stories of Griselda (X.10) and Nastagio degli Onesti (V,8), which appear most frequently on cassoni and spalliera panels, highlight the necessity of a woman's obedience, virtue and chastity. The moral message of these scenes is in keeping with the didactic role of cassoni as teachers decorated with stories intended to inspire newly married couples, particularly young brides, to abide by a strict moral code. Depictions of Boccaccio's many playful stories featuring adulterous relationships are conspicuously absent from the body of fifteenth century secular paintings.

Nearly all of the stories that appeared on cassoni end happily and illustrate aspects of the moral code to which women in the Renaissance were expected to conform. Much as paintings of religious subjects illustrated biblical stories, cassoni depicting scenes from the Decameron would have served as textual illustrations to men and women reading the work in the privacy of their own bedchamber. Similarly, visual representations made stories accessible to those who were not well educated enough to read the textual sources.

Cassoni themselves are also narrative elements in several of Boccaccio's stories, most notably in the stories of Bernabò and Zinevra di Genova (II.9), Zeppa and Spinelloccio (VIII.8), the Abbess and the priest (IX.2) and the King of Spain and Messer Ruggieri (X.1).

Boccaccian Themes in Italian Secular Painting, 1400-1550

In surveying the available literature on imagery derived from Decameron themes, Paul F. Watson's "A Preliminary List of Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1400-1550" proved particularly illuminating. Despite the fact that more and more comprehensive compilations of "visualized" boccaccian themes are available each year, scholars still tend to restrict their examinations of visual renditions of certain tales to long available masterpieces. In doing so they disregard multitudes of images which shed light on Renaissance artists' exegetic attempts to interpret Boccaccio's text.

Three tales from the Decameron seem to have been particularly popular among Italian Renaissance painters, Cimone's story, the story of Griselda (X.10) and Nastagio degli Onesti (V.8). In the following excerpt from Watson's list we have included only those references which pertain to these themes. They constitute over thirty works of art out of approximately one hundred extant images of boccaccian content from the time period. The large proportion of artistic energy devoted to these three specific tales by the same author, or perhaps the favored preservation of these specific works by their patrons, points to some form of Renaissance fascination with the textual themes as they were rendered visually. Due to the preponderance of imagery surrounding these stories, it behooves the scholar interested in questioning image-text relationships to examine as many different visualizations as possible in order to arrive at a more comprehensive view of social and cultural attitudes toward the original text and its interpretation.

A selected bibliography of articles and books on Decameron visualizations has also been compiled for your reference, along with a list of Decameron related paintings by Italian artists between 1400 and 1550. Watson's list is divided into two parts, paintings by unknown masters and those by known artists.

Part 1: Paintings by Unknown Masters

Part 2: Paintings by Known Artists

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1.Callmann, Ellen. "Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1375-1525" Studi sul Boccaccio, Firenze: Sansoni Editore, 23 (1995):19-78. ↩

(S. A. & C. C.)

Sorry the links didn't work:

Boccaccian Themes in Italian Cassone Painting, 1400-1550, Part 1: Paintings by Unknown Masters

Each entry follows this form: location (city, collection); general artistic tradition (eg. Florentine); approximate date; subject with textual source; and format (i.e., cassone, spalliera, etc.). "SENZA CASA" shelters many pictures. They fall into two sub-groupings: (1) paintings cited in sales catalogues or listed in photographic archives without indication of location; (2) homeless pictures once in well-known collections, as in SENZA CASA (Formerly Firenze, Serristori Coll.) Griselda, etc.

Griselda

FIRENZE, Biblioteca Marucelliana, Vol. F. 67, Florentine, ca. 1470. Griselda (Decameron X.10). Drawing, project for a cassone. Cfr B. DEGENHARDT and A. SCHMITT, Corpus der italienischen Zeichnungen 1300-1450, Berlin 1968, II, p. 566, Cat. 561.

LONDON, National Gallery. Umbrian, close to Signorelli, ca. 1500 (The Griselda Master). Griselda I [outgoing link, BBC] (Decameron X.10). Spalliera, companion to Griselda II and III. Cfr. M. DAVIES, The Earlier Italian Schools, 2nd ed., London 1961, pp. 365-367, No. 912.

————, National Gallery. Umbrian, close to Signorelli, ca. 1500 (The Griselda Master). Griselda II [outgoing link, BBC] (Decameron X.10). Spalliera, companion to Griselda I and III. Cfr. M. DAVIES, ibid., No. 913.; also Decameron, ed. Branca, I, pp. xii-xiii.

————, National Gallery. Umbrian, close to Signorelli, ca. 1500 (The Griselda Master). Griselda III [outgoing link, BBC] (Decameron X.10). Spalliera, companion to Griselda I and II. Cfr. M. DAVIES, ibid., No. 914.

LONGLEAT, Warminster, Great Britain, Coll. Marquess of Bath, Florentine, ca. 1465. Unidentified, but clearly Griselda (Decameron X.10). Cassone. Cfr. Photographic Archive, Courtauldt Institute, London B54/398-400.

PAVIA, Castello Visconteo, lost, Lombard, before 1430. Griselda (Decameron X.10). Fresco cycle. Cfr. V. Brance, Boccaccio medievale, 3rd ed., Florence 1970, p. 313.

Castello di Roccabianca

ROCCABIANCA, Parma, formerly (now MILANO, Castello Sforzesco), Milanese (possibly Niccolo da Varallo?), 1458-1464. Sala di Griselda, fresco cycle based on Decameron X.10; 24 episodes plus astrological cycle in ceiling. Cfr. M. ARESE SIMICK, Il ciclo profano degli affreschi di Roccabianca: ipotesi per un'interpretazione iconografica in "Arte lombarda", LXV 1983, pp. 5-26; A. LORENZI, Gli affreschi di Roccabianca, Milano 1967; Decameron, ed. Branca, II, p. 565 and III, p. 953, 955, 956, 957; Daniela Romagnoli, "La storia di Griselda nella camera picta di Roccabianca: un altro autunno del medioevo?" (download pdf). Cfr. also (in Italian) Maria Grazia Tolfo, Il cielo in una stanza a Roccabianca [outgoing link].

SENZA CASA, Florentine, ca. 1430. Subject not identified but possibly conclusion of Griselda (Decameron X.10). Cassone. Cfr. Fototeca, Villa I Tatti, Settignano, Firenze.

————, Florentine, ca. 1450, close to Pesselino. Subject unidentified but clearly Griselda (Decameron X.10). Cassone. Cfr. Fototeca, Villa I Tatti, Settignano, Firenze.

————, formerly FIRENZE, Coll. Serristori, Florentine, ca. 1450. Griselda (Decameron X.10). Cassone. Cfr. Decameron, ed. Branca, III, p. 946, 947; Sotheby Park Burnet Italia sale, Firenze, 9 May 1977. lot. 21.

————, formerly MILANO, Coll. Bagatti-Valsecchi, Florentine, ca. 1490. Griselda (Decameron X.10)?. Cassone. Cfr. SCHUBRING, Cassoni, I, p. 300, No. 347 and II, Taf. LXXXI; E. FAHY, Some Followers of Domenico Ghirlandaio, New York 1976, pp. 181, 183.

Cimone

ALLENTOWN, Pennsylvania, USA, Allentown Art Museum, Florentine, ca. 1460. Story of Cimone (Decameron V.1). Cassone. Cfr. E. CALLMANN, Beyond Nobility: Art for the Private Citizen in the Early Renaissance, Allentown 1981, pp. 7-8.

FIRENZE, Collezione Marchese Ginori, Umbrian, ca. 1500, close to Giovanni Santi. Shepherd and Nymph but more likely Cimone and Efigenia (Decameron V.1). Spalliera (?), companion to Firenze, Ginori. Cfr. B. BERENSON, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: Central Italian and North Italian Schools, London 1968, I, p. 383 and II, pl. 1018.

————, Collezione Marchese Ginori, Umbrian, Shepherd and Nymph, companion to Firenze, Ginori. Cfr. B. BERENSON, ibid., I, p. 383 and II, pl. 1020.

Nastagio

SAINT LOUIS, Missouri, USA, St.Louis Museum of Art, No. 152-1962, Possibly Modern copy of a lost Ferrarese original, late 15th c. Nastagio degli Onesti (Decameron V.8). Cassone. Cfr. SCHUBRING, Cassoni, I, p. 355, No. 537 and II, Taf. CXXVIII; B. B. FREDERICKSON and F. ZERI, Census of Pre-Nineteenth Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections, Cambridge, Mass. 1972, p. 630.

Part 2: Paintings by Known Artists

(S. A.; M.R.) Bibliography: Watson, Paul F. "A Preliminary List of Subjects from Bocaccio in Italian Painting, 1400-1550" Studi sul Boccaccio, Firenze: Sansoni Editore, 1985-6, 15, p. 149-166.

Boccaccian Themes in Italian Cassone Painting, 1400-1550, Part 1: Paintings by Unknown Masters

Each entry follows this form: location (city, collection); general artistic tradition (eg. Florentine); approximate date; subject with textual source; and format (i.e., cassone, spalliera, etc.). "SENZA CASA" shelters many pictures. They fall into two sub-groupings: (1) paintings cited in sales catalogues or listed in photographic archives without indication of location; (2) homeless pictures once in well-known collections, as in SENZA CASA (Formerly Firenze, Serristori Coll.) Griselda, etc.

Griselda

FIRENZE, Biblioteca Marucelliana, Vol. F. 67, Florentine, ca. 1470. Griselda (Decameron X.10). Drawing, project for a cassone. Cfr B. DEGENHARDT and A. SCHMITT, Corpus der italienischen Zeichnungen 1300-1450, Berlin 1968, II, p. 566, Cat. 561.

LONDON, National Gallery. Umbrian, close to Signorelli, ca. 1500 (The Griselda Master). Griselda I [outgoing link, BBC] (Decameron X.10). Spalliera, companion to Griselda II and III. Cfr. M. DAVIES, The Earlier Italian Schools, 2nd ed., London 1961, pp. 365-367, No. 912.

————, National Gallery. Umbrian, close to Signorelli, ca. 1500 (The Griselda Master). Griselda II [outgoing link, BBC] (Decameron X.10). Spalliera, companion to Griselda I and III. Cfr. M. DAVIES, ibid., No. 913.; also Decameron, ed. Branca, I, pp. xii-xiii.

————, National Gallery. Umbrian, close to Signorelli, ca. 1500 (The Griselda Master). Griselda III [outgoing link, BBC] (Decameron X.10). Spalliera, companion to Griselda I and II. Cfr. M. DAVIES, ibid., No. 914.

LONGLEAT, Warminster, Great Britain, Coll. Marquess of Bath, Florentine, ca. 1465. Unidentified, but clearly Griselda (Decameron X.10). Cassone. Cfr. Photographic Archive, Courtauldt Institute, London B54/398-400.

PAVIA, Castello Visconteo, lost, Lombard, before 1430. Griselda (Decameron X.10). Fresco cycle. Cfr. V. Brance, Boccaccio medievale, 3rd ed., Florence 1970, p. 313.

Castello di Roccabianca

ROCCABIANCA, Parma, formerly (now MILANO, Castello Sforzesco), Milanese (possibly Niccolo da Varallo?), 1458-1464. Sala di Griselda, fresco cycle based on Decameron X.10; 24 episodes plus astrological cycle in ceiling. Cfr. M. ARESE SIMICK, Il ciclo profano degli affreschi di Roccabianca: ipotesi per un'interpretazione iconografica in "Arte lombarda", LXV 1983, pp. 5-26; A. LORENZI, Gli affreschi di Roccabianca, Milano 1967; Decameron, ed. Branca, II, p. 565 and III, p. 953, 955, 956, 957; Daniela Romagnoli, "La storia di Griselda nella camera picta di Roccabianca: un altro autunno del medioevo?" (download pdf). Cfr. also (in Italian) Maria Grazia Tolfo, Il cielo in una stanza a Roccabianca [outgoing link].

SENZA CASA, Florentine, ca. 1430. Subject not identified but possibly conclusion of Griselda (Decameron X.10). Cassone. Cfr. Fototeca, Villa I Tatti, Settignano, Firenze.

————, Florentine, ca. 1450, close to Pesselino. Subject unidentified but clearly Griselda (Decameron X.10). Cassone. Cfr. Fototeca, Villa I Tatti, Settignano, Firenze.

————, formerly FIRENZE, Coll. Serristori, Florentine, ca. 1450. Griselda (Decameron X.10). Cassone. Cfr. Decameron, ed. Branca, III, p. 946, 947; Sotheby Park Burnet Italia sale, Firenze, 9 May 1977. lot. 21.

————, formerly MILANO, Coll. Bagatti-Valsecchi, Florentine, ca. 1490. Griselda (Decameron X.10)?. Cassone. Cfr. SCHUBRING, Cassoni, I, p. 300, No. 347 and II, Taf. LXXXI; E. FAHY, Some Followers of Domenico Ghirlandaio, New York 1976, pp. 181, 183.

Cimone

ALLENTOWN, Pennsylvania, USA, Allentown Art Museum, Florentine, ca. 1460. Story of Cimone (Decameron V.1). Cassone. Cfr. E. CALLMANN, Beyond Nobility: Art for the Private Citizen in the Early Renaissance, Allentown 1981, pp. 7-8.

FIRENZE, Collezione Marchese Ginori, Umbrian, ca. 1500, close to Giovanni Santi. Shepherd and Nymph but more likely Cimone and Efigenia (Decameron V.1). Spalliera (?), companion to Firenze, Ginori. Cfr. B. BERENSON, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: Central Italian and North Italian Schools, London 1968, I, p. 383 and II, pl. 1018.

————, Collezione Marchese Ginori, Umbrian, Shepherd and Nymph, companion to Firenze, Ginori. Cfr. B. BERENSON, ibid., I, p. 383 and II, pl. 1020.

Nastagio

SAINT LOUIS, Missouri, USA, St.Louis Museum of Art, No. 152-1962, Possibly Modern copy of a lost Ferrarese original, late 15th c. Nastagio degli Onesti (Decameron V.8). Cassone. Cfr. SCHUBRING, Cassoni, I, p. 355, No. 537 and II, Taf. CXXVIII; B. B. FREDERICKSON and F. ZERI, Census of Pre-Nineteenth Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections, Cambridge, Mass. 1972, p. 630.

Part 2: Paintings by Known Artists

(S. A.; M.R.) Bibliography: Watson, Paul F. "A Preliminary List of Subjects from Bocaccio in Italian Painting, 1400-1550" Studi sul Boccaccio, Firenze: Sansoni Editore, 1985-6, 15, p. 149-166.

Boccaccian Themes in Italian Cassoni Painting, 1400-1550, Part 2: Paintings by Known Artists

In this section each entry is arranged as follows: artist, subject with textual source, approximate date of painting, location, format and bibliographical citation. As in Part 1, a question mark indicates that identifications are open to doubt or, at this time of writing (1987), remain to be proven. I have also deployed the interrogative to indicate attributions that are the topic of current controversy, or should be.

Botticelli, Nastagio

Nastagio

BOTTICELLI, SANDRO, The Calumny of Apelles, with many ancillary scenes including Nastagio degli Onesti (Decameron V.8) and others to be published by S. Meltzoff, forthcoming (Botticelli, Signorelli and Savonarola, Firenze, Olschki, cfr. here p. 109), ca. 1495, Firenze, Uffizi Gallery. Panel, perhaps spalliera. Cfr. R. LIGHTBOWN, Botticelli, Berkeley and Los Angeles 1978, I, pl. 49 and II, pp. 86-92 (for Nastagio only).

————, Nastagio degli Onesti I Art Gallery] (Decameron V.8), 1482-1483, Madrid, Prado. Spalliera companion to BOTTICELLI, Nastagio II, III, IV. Cfr. R. LIGHTBOWN, Botticelli, I, pl. 28A and II, pp. 47, 49-50. Decameron, ed. Branca, II, p. 490.

————, Nastagio II [outgoing link, Web Art Gallery] (Decameron V.8), 1481-1483, Madrid, Prado. Spalliera companion to BOTTICELLI, Nastagio I, III, IV. Cfr. R. LIGHTBOWN, Botticelli, I, pl. 28B and II, pp. 47-48, 49-50. Decameron, ed. Branca, II, p. 491.

————, Nastagio III [outgoing link, Web Art Gallery] (Decameron V.8), 1481-1483, Madrid, Prado. Spalliera companion to BOTTICELLI, Nastagio I, II, IV. Cfr. R. LIGHTBOWN, Botticelli, I, pl. 28C and II, pp. 48, 49-50. Decameron, ed. Branca, II, p. 491.

————, Nastagio IV [outgoing link, Web Art Gallery] (Decameron V.8), 1481-1483, Firenze, private collection. Spalliera companion to BOTTICELLI, Nastagio I-III. Cfr. R. LIGHTBOWN, Botticelli, II, pp. 48-49 and fig. 38.

SELLAIO, JACOPO DEL (?), Nastagio degli Onesti I (Decameron V.8), ca. 1490, Brooklyn, New York, Museum of Art. Cassone companion to SELLAIO, Nastagio Philadelphia.

————, Nastagio II (Decameron V.8), ca. 1490, Philadelphia, Museum of Art, Johnston Coll. Cassone, companion to Nastagio, Brooklyn. Cfr SWEENY, Johnston Collection, pp. 64-65, No. 64 and Pl. 139.

Cimone

BONIFAZIO VERONESE, Shepherd with Sleeping Nymph but more plausibly CIMONE AND IFIGENIA, ca. 1540, senza casa, formerly Basilea, Baron Robert von Hirsch, sold 1978. Panel, perhaps a cassone. Cfr. D. WESTPHAL, Bonifazio Veronese (Bonifazio dei Pitati), Monaco di Baviera 1931, pp. 87-88; B.BERENSON, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: Venetian School, London 1957, I, p. 41; V. Branca, here pp. 109-110.

————, Cimone and Ifigenia (Decameron V.1), ca. 1540, senza casa. Panel, perhaps cassone, variant of BONIFAZIO, Cimone, formerly Hirsch. Cfr. Christie's sale, 23 march 1973, Cat. 36, p. 32; Sotheby sale, 25 november 1980. Verbal communication, V. Branca (cfr. here pp. 109-110).

————, Diana and Actaeon but clearly Cimone and Ifigenia (Decameron V.1), ca. 1550, senza casa. Panel, perhaps cassone, variant of BONIFAZIO, Cimone, formerly Hirsch. Cfr. Sales catalogue, Christie's, London, 9 July 1982, lot 49, illus. p. 100. Verbal communication, V. Branca (cfr. here pp. 109-110).

LUINI, BERNARDINO, Cephalus and Procris, but perhaps Cimone and Efigenia (Decameron V.1), ?, ca. 1520, Washington, National Gallery of Art. Fresco, part of a large cycle perhaps from Milano, Casa Rabia. Cfr. F. R. SHAPLEY, Catalogue of Italian Paintings, Washington 1979, I, p. 287, and II, pl. 202.

PALMA, VECCHIO, Cimone and Efigenia (Decameron V, 1), ca. 1515, London, National Gallery, No. 4037. Panel perhaps a cassone front. Cfr. C. GOULD, The Sixteenth Century Venetian School, London 1959, p. 135 (identification).

The story of Cimone also inspired other famous artists, such as, for example, Peter Paul Rubens (1617) and John. Everett Millais (1848).

Griselda

APOLLONIO DI GIOVANNI, Griselda (Decameron X.10), ca. 1460. Modena, Galleria Estense. Cassone. Cfr. CALLMANN, Apollonio, p. 60, no. 18 and Pls. 112, 113, 116; Decameron, ed. Branca, III, pp. 939, 941, 943.

NICCOLÒ DELL'ABATE, Story of Griselda (Decameron X.10), ca. 1550, Mauriziano (Reggio Emilia), Casino dell'Ariosto. Fresco cycle. Cfr. U. BELLOCCHI, Il Mauriziano, Reggio Emilia 1967, pp. 161-169.

PESELLINO (?), Story of Griselda (Decameron X.10), ca. 1450, Bergamo, Accademia Carrara. Testata to PESELLINO (?), Griselda cassone. Cfr. A. OTTINO DELLA CHIESA, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo 1955, p. 17 and illus.

————(?), Story of Griselda (Decameron X.10), ca. 1450, Bergamo, Accademia Carrara. companion to PESELLINO (?), Griselda testata, Bergamo. Cfr. Decameron, ed. Branca, III, pp. 944-945; H. WOHL, The Paintings of Domenico Veneziano c. 1410-1461, New York and London 1980, p. 155 and pl. 187.

Part 1: Paintings by Unknown Masters

(S. A.) Bibliography: Watson, Paul F. "A Preliminary List of Subjects from Bocaccio in Italian Painting, 1400-1550" Studi sul Boccaccio, Firenze: Sansoni Editore, 1985-6, 15, p. 149-166.

In this section each entry is arranged as follows: artist, subject with textual source, approximate date of painting, location, format and bibliographical citation. As in Part 1, a question mark indicates that identifications are open to doubt or, at this time of writing (1987), remain to be proven. I have also deployed the interrogative to indicate attributions that are the topic of current controversy, or should be.

Botticelli, Nastagio

Nastagio

BOTTICELLI, SANDRO, The Calumny of Apelles, with many ancillary scenes including Nastagio degli Onesti (Decameron V.8) and others to be published by S. Meltzoff, forthcoming (Botticelli, Signorelli and Savonarola, Firenze, Olschki, cfr. here p. 109), ca. 1495, Firenze, Uffizi Gallery. Panel, perhaps spalliera. Cfr. R. LIGHTBOWN, Botticelli, Berkeley and Los Angeles 1978, I, pl. 49 and II, pp. 86-92 (for Nastagio only).

————, Nastagio degli Onesti I Art Gallery] (Decameron V.8), 1482-1483, Madrid, Prado. Spalliera companion to BOTTICELLI, Nastagio II, III, IV. Cfr. R. LIGHTBOWN, Botticelli, I, pl. 28A and II, pp. 47, 49-50. Decameron, ed. Branca, II, p. 490.

————, Nastagio II [outgoing link, Web Art Gallery] (Decameron V.8), 1481-1483, Madrid, Prado. Spalliera companion to BOTTICELLI, Nastagio I, III, IV. Cfr. R. LIGHTBOWN, Botticelli, I, pl. 28B and II, pp. 47-48, 49-50. Decameron, ed. Branca, II, p. 491.

————, Nastagio III [outgoing link, Web Art Gallery] (Decameron V.8), 1481-1483, Madrid, Prado. Spalliera companion to BOTTICELLI, Nastagio I, II, IV. Cfr. R. LIGHTBOWN, Botticelli, I, pl. 28C and II, pp. 48, 49-50. Decameron, ed. Branca, II, p. 491.

————, Nastagio IV [outgoing link, Web Art Gallery] (Decameron V.8), 1481-1483, Firenze, private collection. Spalliera companion to BOTTICELLI, Nastagio I-III. Cfr. R. LIGHTBOWN, Botticelli, II, pp. 48-49 and fig. 38.

SELLAIO, JACOPO DEL (?), Nastagio degli Onesti I (Decameron V.8), ca. 1490, Brooklyn, New York, Museum of Art. Cassone companion to SELLAIO, Nastagio Philadelphia.

————, Nastagio II (Decameron V.8), ca. 1490, Philadelphia, Museum of Art, Johnston Coll. Cassone, companion to Nastagio, Brooklyn. Cfr SWEENY, Johnston Collection, pp. 64-65, No. 64 and Pl. 139.

Cimone

BONIFAZIO VERONESE, Shepherd with Sleeping Nymph but more plausibly CIMONE AND IFIGENIA, ca. 1540, senza casa, formerly Basilea, Baron Robert von Hirsch, sold 1978. Panel, perhaps a cassone. Cfr. D. WESTPHAL, Bonifazio Veronese (Bonifazio dei Pitati), Monaco di Baviera 1931, pp. 87-88; B.BERENSON, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: Venetian School, London 1957, I, p. 41; V. Branca, here pp. 109-110.

————, Cimone and Ifigenia (Decameron V.1), ca. 1540, senza casa. Panel, perhaps cassone, variant of BONIFAZIO, Cimone, formerly Hirsch. Cfr. Christie's sale, 23 march 1973, Cat. 36, p. 32; Sotheby sale, 25 november 1980. Verbal communication, V. Branca (cfr. here pp. 109-110).

————, Diana and Actaeon but clearly Cimone and Ifigenia (Decameron V.1), ca. 1550, senza casa. Panel, perhaps cassone, variant of BONIFAZIO, Cimone, formerly Hirsch. Cfr. Sales catalogue, Christie's, London, 9 July 1982, lot 49, illus. p. 100. Verbal communication, V. Branca (cfr. here pp. 109-110).

LUINI, BERNARDINO, Cephalus and Procris, but perhaps Cimone and Efigenia (Decameron V.1), ?, ca. 1520, Washington, National Gallery of Art. Fresco, part of a large cycle perhaps from Milano, Casa Rabia. Cfr. F. R. SHAPLEY, Catalogue of Italian Paintings, Washington 1979, I, p. 287, and II, pl. 202.

PALMA, VECCHIO, Cimone and Efigenia (Decameron V, 1), ca. 1515, London, National Gallery, No. 4037. Panel perhaps a cassone front. Cfr. C. GOULD, The Sixteenth Century Venetian School, London 1959, p. 135 (identification).

The story of Cimone also inspired other famous artists, such as, for example, Peter Paul Rubens (1617) and John. Everett Millais (1848).

Griselda

APOLLONIO DI GIOVANNI, Griselda (Decameron X.10), ca. 1460. Modena, Galleria Estense. Cassone. Cfr. CALLMANN, Apollonio, p. 60, no. 18 and Pls. 112, 113, 116; Decameron, ed. Branca, III, pp. 939, 941, 943.

NICCOLÒ DELL'ABATE, Story of Griselda (Decameron X.10), ca. 1550, Mauriziano (Reggio Emilia), Casino dell'Ariosto. Fresco cycle. Cfr. U. BELLOCCHI, Il Mauriziano, Reggio Emilia 1967, pp. 161-169.

PESELLINO (?), Story of Griselda (Decameron X.10), ca. 1450, Bergamo, Accademia Carrara. Testata to PESELLINO (?), Griselda cassone. Cfr. A. OTTINO DELLA CHIESA, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo 1955, p. 17 and illus.

————(?), Story of Griselda (Decameron X.10), ca. 1450, Bergamo, Accademia Carrara. companion to PESELLINO (?), Griselda testata, Bergamo. Cfr. Decameron, ed. Branca, III, pp. 944-945; H. WOHL, The Paintings of Domenico Veneziano c. 1410-1461, New York and London 1980, p. 155 and pl. 187.

Part 1: Paintings by Unknown Masters

(S. A.) Bibliography: Watson, Paul F. "A Preliminary List of Subjects from Bocaccio in Italian Painting, 1400-1550" Studi sul Boccaccio, Firenze: Sansoni Editore, 1985-6, 15, p. 149-166.

BP and Reem... you are well ahead of me... I still have a couple of stories from last week, but will catch up soon...knowing that the illustrations and goodies are up motivates me.

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Visualizing the Text: the Cassoni stories..."

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Visualizing the Text: the Cassoni stories..."These pages from Brown are very good. I looked at them when I was looking for Botticelli's Cimone & Iphigenia illustrations. The rest of the pages on cassoni is worth reading too: http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Ital...

The Courtauld Gallery in London has some amazing cassoni, which they exhibited in 2009 (see http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/gallery/ex... and http://arttattler.com/archiverenaissa...). One of which illustrates the story 2 from day II. I'll go post images in the correct thread. :)

Book Portrait wrote: "3 very good (short) videos from Courtauld on cassoni:

http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/gallery/vo..."

Thanks Beepers! Will check out your fabulous links!These really are amazing cassoni!

http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/gallery/vo..."

Thanks Beepers! Will check out your fabulous links!These really are amazing cassoni!

Book Portrait wrote: "3 very good (short) videos from Courtauld on cassoni:

http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/gallery/vo..."

Thank you for these, BP.. excellent.. and now I am relieved to have learnt that I should not keep my chicken and the eggs in any of my s.

http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/gallery/vo..."

Thank you for these, BP.. excellent.. and now I am relieved to have learnt that I should not keep my chicken and the eggs in any of my s.

There are these books...

The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance

Cassone Painting, Humanism, And Gender In Early Modern Italy

The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance

Cassone Painting, Humanism, And Gender In Early Modern Italy

Kalliope wrote: "There are these books...

The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance

Cassone Painting, Humanism, And Gender In Early Modern Italy"

Very good Kalli! I also found this teacher's resource that also explains the cassoni.

http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/publicprog...

Do you think the notion of putting eggs into the marriage cassoni might have inspired artists to create Faberge eggs?

The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance

Cassone Painting, Humanism, And Gender In Early Modern Italy"

Very good Kalli! I also found this teacher's resource that also explains the cassoni.

http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/publicprog...

Do you think the notion of putting eggs into the marriage cassoni might have inspired artists to create Faberge eggs?

Nope:

The story began when Tsar Alexander III decided to give a jewelled Easter egg to his wife the Empress Marie Fedorovna, in 1885, possibly to celebrate the 20th anniversary of their betrothal. It is believed that the Tsar, who had first become acquainted with Fabergé’s virtuoso work at the Moscow Pan-Russian Exhibition in 1882, was inspired by an 18th century egg owned by the Empress’s aunt, Princess Wilhelmine Marie of Denmark. The object was said to have captivated the imagination of the young Maria during her childhood in Denmark. Tsar Alexander was apparently involved in the design and execution of the egg, making suggestions to Fabergé as the project went along. Easter was the most important occasion of the year in the Russian Orthodox Church, equivalent to Christmas in the West. A centuries-old tradition of bringing hand-coloured eggs to Church to be blessed and then presented to friends and family, had evolved through the years and, amongst the highest echelons of St Petersburg society, the custom developed of presenting valuably bejewelled Easter gifts. So it was that Tsar Alexander III had the idea of commissioning Fabergé to create a precious Easter egg as a surprise for the Empress, and thus the first Imperial Easter egg was born.

The story began when Tsar Alexander III decided to give a jewelled Easter egg to his wife the Empress Marie Fedorovna, in 1885, possibly to celebrate the 20th anniversary of their betrothal. It is believed that the Tsar, who had first become acquainted with Fabergé’s virtuoso work at the Moscow Pan-Russian Exhibition in 1882, was inspired by an 18th century egg owned by the Empress’s aunt, Princess Wilhelmine Marie of Denmark. The object was said to have captivated the imagination of the young Maria during her childhood in Denmark. Tsar Alexander was apparently involved in the design and execution of the egg, making suggestions to Fabergé as the project went along. Easter was the most important occasion of the year in the Russian Orthodox Church, equivalent to Christmas in the West. A centuries-old tradition of bringing hand-coloured eggs to Church to be blessed and then presented to friends and family, had evolved through the years and, amongst the highest echelons of St Petersburg society, the custom developed of presenting valuably bejewelled Easter gifts. So it was that Tsar Alexander III had the idea of commissioning Fabergé to create a precious Easter egg as a surprise for the Empress, and thus the first Imperial Easter egg was born.

Sixth tale (VI, 6)

Michele Scalza proves to certain young men that the Baronci are the best gentlemen in the world and the Maremma, and wins a supper.

The Maremma region is an extensive area of Italy bordering the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian Seas. It comprises part of southwestern Tuscany - Maremma Livornese and Maremma Grossetana (the latter in the province of Grosseto) - and part of northern Lazio (in the province of Viterbo and Rome on the border of the region).

The poet Dante Alighieri in his Divina Commedia places Maremma as the region between Cecina, and Corneto (formerly known as Tarquinia).

Non han sì aspri sterpi nè sì folti

quelle fiere selvagge che 'n odio hanno

tra Cecina e Corneto i luoghi colti.

It was traditionally populated by the Butteri, cattle breeders who until recently used horses with a distinctive style of saddle. Once unhealthy because of its many marshes, Maremma was drained under the fascist regime and repopulated with people from other Italian regions, notably the Veneto.

Michele Scalza proves to certain young men that the Baronci are the best gentlemen in the world and the Maremma, and wins a supper.

The Maremma region is an extensive area of Italy bordering the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian Seas. It comprises part of southwestern Tuscany - Maremma Livornese and Maremma Grossetana (the latter in the province of Grosseto) - and part of northern Lazio (in the province of Viterbo and Rome on the border of the region).

The poet Dante Alighieri in his Divina Commedia places Maremma as the region between Cecina, and Corneto (formerly known as Tarquinia).

Non han sì aspri sterpi nè sì folti

quelle fiere selvagge che 'n odio hanno

tra Cecina e Corneto i luoghi colti.

It was traditionally populated by the Butteri, cattle breeders who until recently used horses with a distinctive style of saddle. Once unhealthy because of its many marshes, Maremma was drained under the fascist regime and repopulated with people from other Italian regions, notably the Veneto.

Toto wrote: "Thank you BP for the Courtauld videos. I can see why Boccaccio's moralistic tales would be painted on the cassoni.

Boccaccio is notoriously superficial when it comes to presenting philosophical..."

Toto, did you read the endnotes on the Baronci family?

As the story shows, the Baronci, a well -to-do family of the Florentine bourgeoisie, were notoriously ill-favored. But Scalza's explanation (that they were formed when God was learning the rudiments of his craft) caused problems for B.'s post-Tridentine editors, as well as for the English translators. The apparent blasphemy so shocked the 1620's translator that he replaced it with a different tale altogether, whilst in the 1702 translation Scalza is reported as saying that the antiquity of the Baronci will be evident by that Prometheus made them in time when he first began to Paint, and made others after he was Master of his Art. The 1741 translation has Scalza saying : " You must understand therefore that they were formed when nature was in its infancy, and before she was perfect at her work." This became the standard way of translating the passage until John Payned set matters right in 1886. He anglicized the Baronci calling them " the Cadgers", claiming in a footnote that Baronci is " the Florentine name for what we should call professional beggars." Later in the same footnote, Payne observes, with tongue firmly in cheek, that " this story has been a prodigious stumbling block to former translators, not one of whom appears to have had the slightest idea of Boccaccio's meaning.

Boccaccio is notoriously superficial when it comes to presenting philosophical..."

Toto, did you read the endnotes on the Baronci family?

As the story shows, the Baronci, a well -to-do family of the Florentine bourgeoisie, were notoriously ill-favored. But Scalza's explanation (that they were formed when God was learning the rudiments of his craft) caused problems for B.'s post-Tridentine editors, as well as for the English translators. The apparent blasphemy so shocked the 1620's translator that he replaced it with a different tale altogether, whilst in the 1702 translation Scalza is reported as saying that the antiquity of the Baronci will be evident by that Prometheus made them in time when he first began to Paint, and made others after he was Master of his Art. The 1741 translation has Scalza saying : " You must understand therefore that they were formed when nature was in its infancy, and before she was perfect at her work." This became the standard way of translating the passage until John Payned set matters right in 1886. He anglicized the Baronci calling them " the Cadgers", claiming in a footnote that Baronci is " the Florentine name for what we should call professional beggars." Later in the same footnote, Payne observes, with tongue firmly in cheek, that " this story has been a prodigious stumbling block to former translators, not one of whom appears to have had the slightest idea of Boccaccio's meaning.

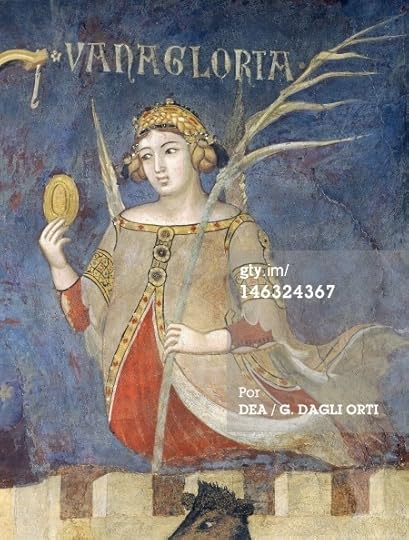

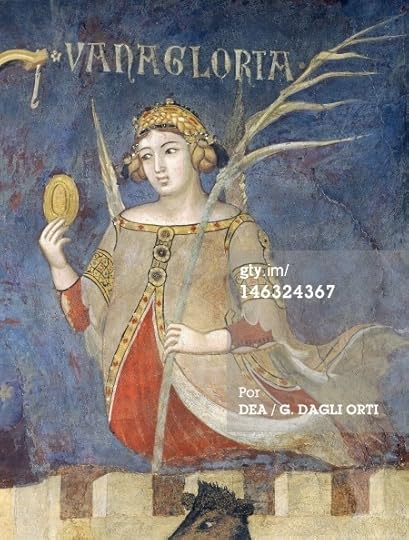

Eighth tale (VI, 8)

Fresco admonishes his niece not to look at herself in the glass, if it is, as she says, grievous to her to see nasty folk.

Emilia narrates. Admonitions against the sin of vanity were common in the medieval era.

In conventional parlance, vanity is the excessive belief in one's own abilities or attractiveness to others. Prior to the 14th century it did not have such narcissistic undertones, and merely meant futility.

The related term vainglory is now often seen as an

archaic synonym for vanity, but originally meant boasting in vain, i.e. unjustified boasting; although glory is now seen as having an exclusively positive meaning, the Latin term gloria (from which it derives) roughly means boasting, and was often used as a negative criticism.

Fresco admonishes his niece not to look at herself in the glass, if it is, as she says, grievous to her to see nasty folk.

Emilia narrates. Admonitions against the sin of vanity were common in the medieval era.

In conventional parlance, vanity is the excessive belief in one's own abilities or attractiveness to others. Prior to the 14th century it did not have such narcissistic undertones, and merely meant futility.

The related term vainglory is now often seen as an

archaic synonym for vanity, but originally meant boasting in vain, i.e. unjustified boasting; although glory is now seen as having an exclusively positive meaning, the Latin term gloria (from which it derives) roughly means boasting, and was often used as a negative criticism.

Ninth tale (VI, 9)

Guido Cavalcanti by a quip meetly rebukes certain Florentine gentlemen who had taken him at a disadvantage.

Elissa narrates.

Guido Cavalcanti (between 1250 and 1259 – August 1300) was an Italian poet and troubadour, as well as an intellectual influence on his best friend, Dante Alighieri

Cavalcanti was the son of Cavalcante de' Cavalcanti, a Guelph whom Dante condemns to torment in the sixth circle of his Inferno, where the heretics are punished. Unlike Dante, he was an atheist. As Giovanni Boccaccio (Decameron, VI, 9) wrote during the generation after Cavalcanti’s death, “Si diceva tralla gente volgare che queste sue speculazioni erano solo in cercare se trovar si potesse che Iddio non fosse” (People commonly said his speculations were only in trying to find that God did not exist).

Influenced by Averroës, the twelfth century Islamic philosopher who commented on Aristotle, Cavalcanti saw humans with three basic capacities: the vegetative, which humans held in common with plants; the sensitive, which man shared with animals; and, the intellectual, which distinguished humans from the two lower forms. Averroës maintained that the proper goal of humanity was the cultivation of the intellect according to reason. Further, Averroës maintained that the intellect was part of a universal consciousness that came into the body at birth and returned to the universal consciousness after death. As such, it meant there was no afterlife, and, as well, the thing that gives an individual his or her identity was not the intellect, but the sensitive faculty, the appetites and desires of the body. Hence, the goal for Averroës and Cavalcanti was the perfection of the sensitive capacity through reason in order to achieve a balance between the body’s physical desires and the intellect. This balance was considered the buon perfetto, the "good perfection." Guido thought this balance could not be achieved, which is why he speaks of “tormented laments” that makes his soul cry, that make his eyes dead, so he can feel “neither peace nor even rest in the place where I found love and my Lady.”

Guido Cavalcanti by a quip meetly rebukes certain Florentine gentlemen who had taken him at a disadvantage.

Elissa narrates.

Guido Cavalcanti (between 1250 and 1259 – August 1300) was an Italian poet and troubadour, as well as an intellectual influence on his best friend, Dante Alighieri

Cavalcanti was the son of Cavalcante de' Cavalcanti, a Guelph whom Dante condemns to torment in the sixth circle of his Inferno, where the heretics are punished. Unlike Dante, he was an atheist. As Giovanni Boccaccio (Decameron, VI, 9) wrote during the generation after Cavalcanti’s death, “Si diceva tralla gente volgare che queste sue speculazioni erano solo in cercare se trovar si potesse che Iddio non fosse” (People commonly said his speculations were only in trying to find that God did not exist).

Influenced by Averroës, the twelfth century Islamic philosopher who commented on Aristotle, Cavalcanti saw humans with three basic capacities: the vegetative, which humans held in common with plants; the sensitive, which man shared with animals; and, the intellectual, which distinguished humans from the two lower forms. Averroës maintained that the proper goal of humanity was the cultivation of the intellect according to reason. Further, Averroës maintained that the intellect was part of a universal consciousness that came into the body at birth and returned to the universal consciousness after death. As such, it meant there was no afterlife, and, as well, the thing that gives an individual his or her identity was not the intellect, but the sensitive faculty, the appetites and desires of the body. Hence, the goal for Averroës and Cavalcanti was the perfection of the sensitive capacity through reason in order to achieve a balance between the body’s physical desires and the intellect. This balance was considered the buon perfetto, the "good perfection." Guido thought this balance could not be achieved, which is why he speaks of “tormented laments” that makes his soul cry, that make his eyes dead, so he can feel “neither peace nor even rest in the place where I found love and my Lady.”

Cavalcanti's Legacy:

Cavalcanti is widely regarded as the first major poet of Italian literature: Dante calls him "mentor". In the Commedia he says through Oderisi da Gubbio that "...ha tolto l'uno a l'altro Guido / la gloria de la lingua" (Purgatory XI, 97-8): the verse of the latter, younger Guido (Cavalcanti) has surpassed that of the former, (Guido) Guinizzelli, the founder of Dolce Stil Novo. Dante sees in Guido his mentor; his meter, his language deeply inspire his work (cfr. De Divina Eloquentia), though Guido's esthetic materialism would be taken a step further to an entirely new spiritual, Christian vision of the gentler sex, as personified by Beatrice whose soul becomes Dante's guide to Paradise.

Guido's controversial personality and beliefs attracted the interest of Boccaccio, who made him one of the most famous heretical characters in his Decameron, helping popularise the belief about his atheism. Cavalcanti would be studied with perhaps more interest during the Renaissance, by such scholars as Luigi Pulci and Pico della Mirandola. By passing to Dante's study of the Italian language, Guido's style has influenced all those who, like cardinal Pietro Bembo, helped turn the volgare illustre into today's Italian language.

Cavalcanti was to become a strong influence on a number of writers associated with the development of Modernist poetry in English. This influence can be traced back to the appearance, in 1861, of Dante Gabriel Rossetti's The Early Italian Poets, which featured translations of works by both Cavalcanti and Dante.

The young Ezra Pound admired Rossetti and knew his Italian translations well, quoting extensively from them in his 1910 book The Spirit of Romance. In 1912, Pound published his own translations under the title The Sonnets and Ballate of Guido Cavalcanti and in 1932, he published the Italian poet's works as Rime. A reworked translation of Donna me prega formed the bulk of Canto XXXVI in Pound's long poem The Cantos. Pound's main focus was on Cavalcanti's philosophy of love and light, which he viewed as a continuing expression of a pagan, neo-platonic tradition stretching back through the troubadours and early medieval Latin lyrics to the world of pre-Christian polytheism. Pound also composed a three-act opera titled Cavalcanti at the request of Archie Harding, a producer at the BBC. Though never performed in his lifetime, excerpts are available on audio CD.

Pound's friend and fellow modernist T. S. Eliot used an adaptation of the opening line of Perch'i' no spero di tornar giammai ("Because I do not hope to turn again") to open his 1930 poem Ash Wednesday.

Cavalcanti is widely regarded as the first major poet of Italian literature: Dante calls him "mentor". In the Commedia he says through Oderisi da Gubbio that "...ha tolto l'uno a l'altro Guido / la gloria de la lingua" (Purgatory XI, 97-8): the verse of the latter, younger Guido (Cavalcanti) has surpassed that of the former, (Guido) Guinizzelli, the founder of Dolce Stil Novo. Dante sees in Guido his mentor; his meter, his language deeply inspire his work (cfr. De Divina Eloquentia), though Guido's esthetic materialism would be taken a step further to an entirely new spiritual, Christian vision of the gentler sex, as personified by Beatrice whose soul becomes Dante's guide to Paradise.

Guido's controversial personality and beliefs attracted the interest of Boccaccio, who made him one of the most famous heretical characters in his Decameron, helping popularise the belief about his atheism. Cavalcanti would be studied with perhaps more interest during the Renaissance, by such scholars as Luigi Pulci and Pico della Mirandola. By passing to Dante's study of the Italian language, Guido's style has influenced all those who, like cardinal Pietro Bembo, helped turn the volgare illustre into today's Italian language.

Cavalcanti was to become a strong influence on a number of writers associated with the development of Modernist poetry in English. This influence can be traced back to the appearance, in 1861, of Dante Gabriel Rossetti's The Early Italian Poets, which featured translations of works by both Cavalcanti and Dante.

The young Ezra Pound admired Rossetti and knew his Italian translations well, quoting extensively from them in his 1910 book The Spirit of Romance. In 1912, Pound published his own translations under the title The Sonnets and Ballate of Guido Cavalcanti and in 1932, he published the Italian poet's works as Rime. A reworked translation of Donna me prega formed the bulk of Canto XXXVI in Pound's long poem The Cantos. Pound's main focus was on Cavalcanti's philosophy of love and light, which he viewed as a continuing expression of a pagan, neo-platonic tradition stretching back through the troubadours and early medieval Latin lyrics to the world of pre-Christian polytheism. Pound also composed a three-act opera titled Cavalcanti at the request of Archie Harding, a producer at the BBC. Though never performed in his lifetime, excerpts are available on audio CD.

Pound's friend and fellow modernist T. S. Eliot used an adaptation of the opening line of Perch'i' no spero di tornar giammai ("Because I do not hope to turn again") to open his 1930 poem Ash Wednesday.

Tenth tale (VI, 10)

Saint Lawrence on trial. The saint figures in tale VI, 10.

Friar Cipolla promises to show certain country-folk a feather of the Angel Gabriel, in lieu of which he finds coals, which he avers to be of those with which Saint Lawrence was roasted.

Dioneo narrates this story which pokes fun at the worship of relics.

The story originates in the Sanskrit collection of stories called Canthamanchari.

This story—a classic from the collection—takes place in Certaldo, Boccaccio's hometown (and the location where he would later die). Friar Cipolla's name means "Brother Onion," and Certaldo was famous in that era for its onions. In the story one can sense a certain love on Boccaccio's part for the people of Certaldo, even while he is mocking them.

Saint Lawrence on trial. The saint figures in tale VI, 10.

Friar Cipolla promises to show certain country-folk a feather of the Angel Gabriel, in lieu of which he finds coals, which he avers to be of those with which Saint Lawrence was roasted.

Dioneo narrates this story which pokes fun at the worship of relics.

The story originates in the Sanskrit collection of stories called Canthamanchari.

This story—a classic from the collection—takes place in Certaldo, Boccaccio's hometown (and the location where he would later die). Friar Cipolla's name means "Brother Onion," and Certaldo was famous in that era for its onions. In the story one can sense a certain love on Boccaccio's part for the people of Certaldo, even while he is mocking them.

Again there is mention of the nightingale:

But no nightingale was ever as happy on the branch of a tree as Guccio Imbratta in the kitchen of an inn, especially if there happened to be a serving-wench in the offing. (6.10)

But no nightingale was ever as happy on the branch of a tree as Guccio Imbratta in the kitchen of an inn, especially if there happened to be a serving-wench in the offing. (6.10)

Reem, I will come back to the excellent posts above.., since I am very interested in the topic

Now I just wanted to remind everyone that the Santa Reparata mentioned in the 9th Tale is the church that was there before the new Cathedral of Santa Maria dei Fiore was built... Funnily enough a certain Betto Brunelleschi es mentioned in this same tale..., not the same as Filippo.

Now I just wanted to remind everyone that the Santa Reparata mentioned in the 9th Tale is the church that was there before the new Cathedral of Santa Maria dei Fiore was built... Funnily enough a certain Betto Brunelleschi es mentioned in this same tale..., not the same as Filippo.

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Cavalcanti's Legacy:

Cavalcanti is widely regarded as the first major poet of Italian literature: Dante calls him "mentor". In the Commedia he says through Oderisi da Gubbio that "...ha tolto l'un..."

Yes, the name Cavalcanti appears often when dealing with the Italian Renaissance... it does not always refer to the famous poet.. but I always think of him and of Dante.

Cavalcanti is widely regarded as the first major poet of Italian literature: Dante calls him "mentor". In the Commedia he says through Oderisi da Gubbio that "...ha tolto l'un..."

Yes, the name Cavalcanti appears often when dealing with the Italian Renaissance... it does not always refer to the famous poet.. but I always think of him and of Dante.

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Eighth tale (VI, 8)

Fresco admonishes his niece not to look at herself in the glass, if it is, as she says, grievous to her to see nasty folk.

Emilia narrates. Admonitions against the sin of vani..."

Vainglory is present in the Bad Government fresco by Ambroggio Lorenzetti in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena.

Here she is, in all her splendor.., and with her mirror of vanity.

Fresco admonishes his niece not to look at herself in the glass, if it is, as she says, grievous to her to see nasty folk.

Emilia narrates. Admonitions against the sin of vani..."

Vainglory is present in the Bad Government fresco by Ambroggio Lorenzetti in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena.

Here she is, in all her splendor.., and with her mirror of vanity.

Kalliope wrote: "ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Eighth tale (VI, 8)

Fresco admonishes his niece not to look at herself in the glass, if it is, as she says, grievous to her to see nasty folk.

Emilia narrates. Admon..."

I saw your video. It really is fantastic. Thanks for sharing this pic.

Fresco admonishes his niece not to look at herself in the glass, if it is, as she says, grievous to her to see nasty folk.

Emilia narrates. Admon..."

I saw your video. It really is fantastic. Thanks for sharing this pic.

Book Portrait wrote: "Illustrations - Day VI Story 10

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Cipolla trompant les fidèles

http://digi.vatlib.it/diglitData/imag......"

I liked this story. In my Spanish edition, Cipolla's name has been translated... (cebolla/onion). The name must be related to the story, it made me think that onions have several shells (not sure what the word is)..

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Cipolla trompant les fidèles

http://digi.vatlib.it/diglitData/imag......"

I liked this story. In my Spanish edition, Cipolla's name has been translated... (cebolla/onion). The name must be related to the story, it made me think that onions have several shells (not sure what the word is)..

I was struck by the description of the Valley of the Ladies/Dames..

Has anyone found anything for this?

It is another Eden.

And in this description, the Narrator (Boccaccio himself?) makes reference to himself.

Has anyone found anything for this?

It is another Eden.

And in this description, the Narrator (Boccaccio himself?) makes reference to himself.

I am trying to find an illustration of the Valley of Women, which I have found a very interesting section...

Not quite the valley, but still, by Jacques Wagrez (I had never heard of him before). I think this image comes not from a free-standing painting but from a fully illustrated edition.

I will try to take down notes from the article in Jstor above...

Not quite the valley, but still, by Jacques Wagrez (I had never heard of him before). I think this image comes not from a free-standing painting but from a fully illustrated edition.

I will try to take down notes from the article in Jstor above...

More on the Valley of Women...

Decameron

VI. The Valley of Women

Together with the comic insert which has as its protagonists the relatives of the brigade in the Introduction Boccaccio inserts into the Conclusion to the day a digression on the trip the female storytellers make to the Valley of Women. The place’s fabulous topography, which has at the centre of a crown formed by six hills a lake with crystal clear waters, is inspired to the topos of the locus amoenus and appears to be the fruit of literary recollections, rather than personal reminiscences tied to a recollection of the beauty of the local countryside. The young women’s washing session of the afternoon is followed by the young men’s bathing in the evening; and the two ablutions, almost a purgatorial rite that marks a passage, are a break between the first and the second half of Boccaccio’s hundred novellas.

If the themes of Love and Fortune would seem to dominate the first five days, with Madonna Oretta’s novella (VI, 1) the theme here becomes human genius and virtue. The brief proemial tale also contains a strong erotic element, based on insistent recourse to the equine metaphor of the “trot”. The specific nature of the novella is however visible in the evaluation of the metaliterary allusions, which make of the narrative a sort of set of instructions for the use of the Decameron. The incident occurred to Madonna Oretta would seem to cast a shadow upon the indication of how to more congruously utilise the work, which is, in the end, in the declaration of the novellas as it is made by the youths of the brigade within the framework.

Decameron

VI. The Valley of Women

Together with the comic insert which has as its protagonists the relatives of the brigade in the Introduction Boccaccio inserts into the Conclusion to the day a digression on the trip the female storytellers make to the Valley of Women. The place’s fabulous topography, which has at the centre of a crown formed by six hills a lake with crystal clear waters, is inspired to the topos of the locus amoenus and appears to be the fruit of literary recollections, rather than personal reminiscences tied to a recollection of the beauty of the local countryside. The young women’s washing session of the afternoon is followed by the young men’s bathing in the evening; and the two ablutions, almost a purgatorial rite that marks a passage, are a break between the first and the second half of Boccaccio’s hundred novellas.

If the themes of Love and Fortune would seem to dominate the first five days, with Madonna Oretta’s novella (VI, 1) the theme here becomes human genius and virtue. The brief proemial tale also contains a strong erotic element, based on insistent recourse to the equine metaphor of the “trot”. The specific nature of the novella is however visible in the evaluation of the metaliterary allusions, which make of the narrative a sort of set of instructions for the use of the Decameron. The incident occurred to Madonna Oretta would seem to cast a shadow upon the indication of how to more congruously utilise the work, which is, in the end, in the declaration of the novellas as it is made by the youths of the brigade within the framework.

Kalliope wrote: "I am trying to find an illustration of the Valley of Women, which I have found a very interesting section...

Not quite the valley, but still, by Jacques Wagrez (I had never heard of him before). ..."

Have a look at this. I can't post the photo, it's the third one down. Warning:some racy images.

The Case for 14th Century Erotica: Boccaccio and Sexual Economy in The Decameron

Anyone who has read Boccaccio’s Decameron knows that it is undeniably the erotica of the 14th century: virtually all of the hundred stories contained in the book deal with illicit sexual escapes of some kind or another. And, living up to the Italian stereotype, most of them involve priests and nuns.

But Tobias Foster Gittes argues that Boccaccio’s stories are more than titillating fantasies for the Italian public: rather, they provide an alternate, socially productive outlet for the pent-up sexual frustrations that can otherwise result in ultimately destructive sexual behavior such as incest or rape. Erotica and other forms of ‘voyeurism’ “provid[ed] erotic pleasure by proxy” (148). In other words, distributing the Decameron to men of the cloth was one way to keep priests from molesting the altar boys.

On the seventh day, the ladies of the group decide to go to a secluded lake in the woods to bathe — a place they call the ‘valle delle donne’ [the valley of women, or alternately the women’s valley]. Gittes argues that Boccaccio uses their romp in this valley to illustrate how sexual energy can be productively released through voyeurism.

Gittes argues that Boccaccio, in describing the ‘valle delle donne’ through simile, transforms the three “classical loci of rape” in Greek literature — the theatre, the wooded tarn*, and the pleasance** — into productive venues of sexual energy.

tarn (n): a small steep-banked mountain lake or pool.

pleasance: a pleasant rest or recreation place usually attached to a mansion

Gittes cites a variety of classical sources that describe the theatre, the wooded tarn, and the pleasance as sexually threatening. For example, Ovid writes that in the theatre, “chaste modesty doesn’t stand a chance”:

“Urgently brooding in silence, the men kept glancing

About them, each marking his choice

Among the girls…

The king gave the sign for which

They’d so eagerly watched. Project Rape was on…

…Ever since that day, by hallowed

custom,

Our theatres have always held dangers for pretty girls.” (qtd. in Gittes 151)

When the women bathe in the pool in the ‘valle delle donne,’ Boccaccio writes that the lake “non altrimenti li lor corpi candidi nascondeva, che farebbe una vermiglia rosa un sottil vetro” [“hid their white bodies no otherwise than as a thin glass would do with a vermeil rose”] (qtd. in Gittes 153). Gittes points out that this wording is remarkably similar to Ovid’s description of Salmacis and Hermaphroditus: “the light / shines through the limpid pool, revealing him — / as if, within clear glass, one had encased / white lilies with the white of ivory shapes” (qtd. in Gittes 153). Unlike most of the tales of naked bathing women in antiquity, Boccaccio’s does not end in rape or attempted sexual assault of any kind.

To read more:

http://ucb-cluj.org/2013/02/10/the-ca...

It leads to the same JSTOR article you site above.

Not quite the valley, but still, by Jacques Wagrez (I had never heard of him before). ..."

Have a look at this. I can't post the photo, it's the third one down. Warning:some racy images.

The Case for 14th Century Erotica: Boccaccio and Sexual Economy in The Decameron

Anyone who has read Boccaccio’s Decameron knows that it is undeniably the erotica of the 14th century: virtually all of the hundred stories contained in the book deal with illicit sexual escapes of some kind or another. And, living up to the Italian stereotype, most of them involve priests and nuns.

But Tobias Foster Gittes argues that Boccaccio’s stories are more than titillating fantasies for the Italian public: rather, they provide an alternate, socially productive outlet for the pent-up sexual frustrations that can otherwise result in ultimately destructive sexual behavior such as incest or rape. Erotica and other forms of ‘voyeurism’ “provid[ed] erotic pleasure by proxy” (148). In other words, distributing the Decameron to men of the cloth was one way to keep priests from molesting the altar boys.

On the seventh day, the ladies of the group decide to go to a secluded lake in the woods to bathe — a place they call the ‘valle delle donne’ [the valley of women, or alternately the women’s valley]. Gittes argues that Boccaccio uses their romp in this valley to illustrate how sexual energy can be productively released through voyeurism.

Gittes argues that Boccaccio, in describing the ‘valle delle donne’ through simile, transforms the three “classical loci of rape” in Greek literature — the theatre, the wooded tarn*, and the pleasance** — into productive venues of sexual energy.

tarn (n): a small steep-banked mountain lake or pool.

pleasance: a pleasant rest or recreation place usually attached to a mansion

Gittes cites a variety of classical sources that describe the theatre, the wooded tarn, and the pleasance as sexually threatening. For example, Ovid writes that in the theatre, “chaste modesty doesn’t stand a chance”:

“Urgently brooding in silence, the men kept glancing

About them, each marking his choice

Among the girls…

The king gave the sign for which

They’d so eagerly watched. Project Rape was on…

…Ever since that day, by hallowed

custom,

Our theatres have always held dangers for pretty girls.” (qtd. in Gittes 151)

When the women bathe in the pool in the ‘valle delle donne,’ Boccaccio writes that the lake “non altrimenti li lor corpi candidi nascondeva, che farebbe una vermiglia rosa un sottil vetro” [“hid their white bodies no otherwise than as a thin glass would do with a vermeil rose”] (qtd. in Gittes 153). Gittes points out that this wording is remarkably similar to Ovid’s description of Salmacis and Hermaphroditus: “the light / shines through the limpid pool, revealing him — / as if, within clear glass, one had encased / white lilies with the white of ivory shapes” (qtd. in Gittes 153). Unlike most of the tales of naked bathing women in antiquity, Boccaccio’s does not end in rape or attempted sexual assault of any kind.

To read more:

http://ucb-cluj.org/2013/02/10/the-ca...

It leads to the same JSTOR article you site above.

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Kalliope wrote: "I am trying to find an illustration of the Valley of Women, which I have found a very interesting section...

Not quite the valley, but still, by Jacques Wagrez (I had never heard..."

Has anyone watched Pasolini's film?

Not quite the valley, but still, by Jacques Wagrez (I had never heard..."

Has anyone watched Pasolini's film?

Have we mentioned this book before?

In 1360, Boccaccio began work on De mulieribus claris, a book offering biographies of one hundred and six famous women, that he completed in 1374.

Boccaccio claimed to have written the 106 biographies for the posterity of the women who were considered renowned, whether good or bad. He believed that recounting the deeds of certain women who may have been wicked would be offset by the exhortations to virtue by the deeds of good women. He writes in his presentation of this combination of all types of women that hopefully it would encourage virtue and curb vice

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_mulie...

In 1360, Boccaccio began work on De mulieribus claris, a book offering biographies of one hundred and six famous women, that he completed in 1374.

Boccaccio claimed to have written the 106 biographies for the posterity of the women who were considered renowned, whether good or bad. He believed that recounting the deeds of certain women who may have been wicked would be offset by the exhortations to virtue by the deeds of good women. He writes in his presentation of this combination of all types of women that hopefully it would encourage virtue and curb vice

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_mulie...

I started to watch Boccaccio '70 with Sophia Loren on Netflix but got distracted after after a few min and haven't gone back to it yet.

I started to watch Boccaccio '70 with Sophia Loren on Netflix but got distracted after after a few min and haven't gone back to it yet. I found a copy of Pasolini's The Decameron but haven't watched it yet either.

(so little free time and I prefer to read when I have it)

Kalliope wrote: "Book Portrait wrote: "Illustrations - Day VI Story 10

Kalliope wrote: "Book Portrait wrote: "Illustrations - Day VI Story 10http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Cipolla trompant les fidèles

http://digi.vatlib.it/diglitData/imag......"

..."

Hi Kall,

In English, anyway, it's 'layers", so appropriate....and there's a certain type of small onion that we still call cipollini: a smaller, flat, pale onion. The flesh is a slight yellowish color and the skins are thin and papery. The color of the skin ranges from pale yellow to the light brown color of Spanish onions. These are sweeter onions, having more residual sugar than garden-variety white or yellow onions, but not as much as shallots.

The advantage to cipollinis is that they are small and flat and the shape lends them well to roasting. This combined with their sweetness makes for a lovely addition to recipes where you might want to use whole caramelized onions.

So, tiny, small, delicate, pale, but more to them than meets the eye....

(I think I'm a frustrated chef at heart :) )

I haven't read all the comments yet but i was wondering whether anyone else found Day 6 the least enjoyable so far? I have to say the stories were slightly dull. On to Day 7 now:)

I haven't read all the comments yet but i was wondering whether anyone else found Day 6 the least enjoyable so far? I have to say the stories were slightly dull. On to Day 7 now:)

Somehow, I went from pretty far behind to ahead of the game....must have been all of the pre-semester procrastination! :)

Somehow, I went from pretty far behind to ahead of the game....must have been all of the pre-semester procrastination! :)But yes, I was getting the feeling that they were running out of material and the stories are starting to blend together. There was that story in the other section that made me say "This must have been the medieval "50 Shades", bc that one was spicy!

Rowena wrote: "I haven't read all the comments yet but i was wondering whether anyone else found Day 6 the least enjoyable so far? I have to say the stories were slightly dull. On to Day 7 now:)"

Rowena, I couldn't agree with you more. At some point the stories all begin to blend together as Linda says. Perhaps this link will help us to look further at the complexity of the references and allusions that Boccaccio provides us with.

Marchesi makes the assertion: "There is no single Ideal reader of the Decameron, but there are (were) different readerships who enjoy(ed)the work."

Do have a look:

http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Ital...

Rowena, I couldn't agree with you more. At some point the stories all begin to blend together as Linda says. Perhaps this link will help us to look further at the complexity of the references and allusions that Boccaccio provides us with.

Marchesi makes the assertion: "There is no single Ideal reader of the Decameron, but there are (were) different readerships who enjoy(ed)the work."

Do have a look:

http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Ital...

http://heliotropia.org/ some reviews to check out

Also check out the American Boccaccio Association and newsletters:

Also check out the American Boccaccio Association and newsletters:

Linda and Reem,

Linda and Reem,Thank you! I'm glad it wasn't just me! I have enjoyed The Decameron up to this point. I'm sure (I hope!) the stories will become more enjoyable.

And thanks for the links, Reem! I'll have a look during my lunch break:)

Rowena wrote: "Linda and Reem,

Thank you! I'm glad it wasn't just me! I have enjoyed The Decameron up to this point. I'm sure (I hope!) the stories will become more enjoyable.

And thanks for the links, Reem! I'..."

Certainly Rowena. You know what they say:

Begin at the beginning... and go on till you come to the end: then stop. ~Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

... it will all come together!

Thank you! I'm glad it wasn't just me! I have enjoyed The Decameron up to this point. I'm sure (I hope!) the stories will become more enjoyable.

And thanks for the links, Reem! I'..."

Certainly Rowena. You know what they say:

Begin at the beginning... and go on till you come to the end: then stop. ~Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

... it will all come together!

Haha! So very true! I have a silly question about translations: the little poems they include at the end of each day all rhyme; as the original language is Italian, how do they get them all to rhyme? I'm thinking the translations aren't accurate then? That's a question that's bugged me since I read a bit of "The Misanthrope."

Haha! So very true! I have a silly question about translations: the little poems they include at the end of each day all rhyme; as the original language is Italian, how do they get them all to rhyme? I'm thinking the translations aren't accurate then? That's a question that's bugged me since I read a bit of "The Misanthrope."

Rowena wrote: "Haha! So very true! I have a silly question about translations: the little poems they include at the end of each day all rhyme; as the original language is Italian, how do they get them all to rhym..."

That's a really good question, and good translators I suppose do their best to pick up the essence of the period, the voice of the author and then translate that into an English voice that will allow us to read comfortably. I think that no matter how good it sounds to our ears, we still have a poor substitute for Boccaccio's original style in Italian prose.

The Misanthrope is fantastic! I thought it was so funny!

That's a really good question, and good translators I suppose do their best to pick up the essence of the period, the voice of the author and then translate that into an English voice that will allow us to read comfortably. I think that no matter how good it sounds to our ears, we still have a poor substitute for Boccaccio's original style in Italian prose.

The Misanthrope is fantastic! I thought it was so funny!

Ah thank you, Reem! Your explanation makes sense. I will pick up The Misanthrope after The Decameron:)

Ah thank you, Reem! Your explanation makes sense. I will pick up The Misanthrope after The Decameron:)

Rowena wrote: "Linda and Reem,

Rowena wrote: "Linda and Reem,Thank you! I'm glad it wasn't just me! I have enjoyed The Decameron up to this point. I'm sure (I hope!) the stories will become more enjoyable.

And thanks for the links, Reem! I'..."

They do. I noticed the brevity of these, and these were the ones that made me wish I could read Italian better than I do, as I felt some of the humor was either lost in translation or not as agile. The one that made me say "Oh, my!", I guess, was in 7th Day.

Books mentioned in this topic

The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance (other topics)Cassone Painting, Humanism and Gender in Early Modern Italy (other topics)

The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance (other topics)

Cassone Painting, Humanism and Gender in Early Modern Italy (other topics)