Divine Comedy + Decameron discussion

This topic is about

The Decameron

Group Lounge for Decameron

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Lily

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Jun 03, 2014 10:07AM

Per request, am adding this thread for "Group Lounge" discussions related to

The Decameron

by Giovanni Boccaccio.

Per request, am adding this thread for "Group Lounge" discussions related to

The Decameron

by Giovanni Boccaccio.

reply

|

flag

Thanks Lily! While "googling", I came across this undergraduate honors thesis that looks at the Decameron as: Narrative as Therapy and of the Medieval Methods of Medicine and Storytelling as Prescribed Healing. Do have a look:

The Decameron:Balm for a Ravaged Society

http://comcul.ucalgary.ca/Decameron

The Decameron:Balm for a Ravaged Society

http://comcul.ucalgary.ca/Decameron

Numerology in the Decameron plays a large role and possibly points to larger themes in the text. The number ten is significant, as it appears in the title (The Decameron), the number of members in the brigata, and the number of stories told in each day. The year in which Florence was decimated by the plague was 1348. The first and last digits add up to nine, while the middle two digits sum seven. There are three men and seven ladies in the brigata. The ladies all fall between the ages of eighteen and twenty-seven, both of which are multiples of three. The seven ladies are further divided into a group of three (the theological virtues) and four (the cardinal virtues). This division is made by those who bring handmaids and those who do not (cardinal virtues and theological virtues, respectively). The three theological virtues dominate the stories on the third, sixth, and ninth days. [28]

Furthermore, the years in which the ladies were born fall between 1321 and 1330, the digits of both of which add up to seven. The minimum age of the men is 25, and the digits “2” and “5” sum seven.

Aldo believes the numbers to “point to the presence of a triune God and of the labors involved in the seven days of creation (or in observing the seven virtues)” [29] The brigata, however, does not recognize God’s hand, and they choose to escape the plagued city and enjoy ten days of festivities. Their ignorance of the divine presence in their numbers, the brigata proves to be spiritually blind.

Furthermore, the years in which the ladies were born fall between 1321 and 1330, the digits of both of which add up to seven. The minimum age of the men is 25, and the digits “2” and “5” sum seven.

Aldo believes the numbers to “point to the presence of a triune God and of the labors involved in the seven days of creation (or in observing the seven virtues)” [29] The brigata, however, does not recognize God’s hand, and they choose to escape the plagued city and enjoy ten days of festivities. Their ignorance of the divine presence in their numbers, the brigata proves to be spiritually blind.

Members of the Brigata

◦Pampinea

◦Filomena

◦Neifile

◦Filostrato

◦Fiammetta

◦Elissa

◦Dioneo

◦Lauretta

◦Emilia

◦Panfilo

The group of ten Florentine youths, known as the “brigata,” comprises seven women and three men, each of whom has an allegorical role. McWilliam writes that the women probably represent the four cardinal virtues (Prudence, Justice, Temperance, and Fortitude) and the three theological virtues (Faith, Hope, and Love) [15]. The men are the three could represent the tripartite division of the soul into Reason, Anger, and Lust. The author writes in the Introduction that he has withheld the true names of the members of the brigata, because he doesn’t want them to “feel embarrassed, at any time in the future, on account of the ensuing stories, all of which they either listened to or narrated themselves [16]. The translations of the Italian names of the members of the Brigata, with their possible allegorical roles, is as follows [17]:

Pampinea-full of vigor (Prudence) Fiammetta-little flame (Temperance) Filomena-the beloved, or lover of song (Fortitude) Emilia-she who allures (Faith) Elissa-an Italian variant on Dido (Hope) Neifile-newly enamored, possibly a reference to the dolce stil novo and Dante (Charity) Lauretta-a diminutive of Petrach’s Laura (Justice) Panfilo-all-loving (Reason) Filostrato- defeated by love (Anger) Dioneo-an italianized version of Dionysus (Lust)

Notes that don't have spoilers:

Pampinea

Pampinea, the eldest of the seven lady narrators at twenty-seven years of age, is the natural leader among them. In Italian her name means "la rigogliosa" which could be translated as "the flourishing one." It was her suggestion for the group to move to the countryside and her initiative that brought the three men into their plans. In return, she was made Queen of the first day.

Neifile

Appearance: young, beautiful, charming, elegant, cheerful.

"Neifile whose manners were no less striking than her beauty, replied with a smile..." (I.2).

Fiammetta

Several scholars of Boccaccio like to believe that the Fiammetta of the brigata was based upon a real woman, Maria d'Aquino, with whom Boccaccio fell in love. "Fiammetta" is a recurring character in a number of Boccaccio's works (e.g., The Filocolo and L'elegia di Madonna Fiammetta ) and is generally described in consistent terms: "[her hair] is so blonde that the world holds nothing like it; it shades a white forehead of noble width, beneath which are the curves of two black and most slender eyebrows ... and under these two roguish eyes ... cheeks of no other colour than milk."

In the Decameron, Fiammetta is one of the most assertive women. She often engages Filostrato and others in competitive storytelling about the nature of love. She is a clever, independent and resourceful woman who admires these same qualities in others. Fiammetta often tells stories about tricksters and delights in tales about strong female characters. Her tone is largely positive, with the exception of her stories of the Fourth and Fifth Days.

Elissa

There has been much discussion concerning the significance of the names Boccaccio has given to his narrators - allegorical representations of the seven virtues, symbols of other moral qualities, or just characters that have populated Boccaccio's earlier works. It has been said that Elissa represents either "hope" (Kirkham) or "justice" (Ferrante) and also that she is very young and dominated by a violent passion. Paden suggests that she is the sole recognizable Ghibelline of the group.

The first glimpse of Elissa's character comes in the Introduction of the First Day in which Pampinea has suggested to the other women her plan for fleeing the city in order in an attempt to save their own lives and to return to a somewhat ordered and rational existence. Filomena agrees that this is a good idea but she believes since they are all women and, by nature, "fickle, quarrelsome, suspicious, cowardly, and easily frightened," they will never succeed in their venture.

It is here that Elissa speaks up: she agrees that women are unsuited and unable to act without male guidance but, she wonders, where will they find suitable male companions. She fears for the safety of the group and is concerned about any possible scandal related to traveling with a group of men.

Dioneo

In his introduction to I.4, the first story he tells, Dioneo expresses the opinion "that each must be allowed [...] to tell whatever story we think most likely to amuse." Consequently he will be granted the privilege not to follow the theme of the day and to tell instead the story that most pleases him, regardless of its consonance or dissonance with the others told in that day. In exchange, he will be the last of the ten narrators to tell a story. This positioning is significant because it is meant not to interfere with the pattern developed in a given day; on the contrary, Dioneo's privilege grants him a role of transgressor while at the same time, as an exception, reinforces the (narrative) rule that governs the Decameron.

Dioneo as Transgressor

Within the space of their paradisiac seclusion from reality, death and disease, Dioneo reminds the brigata of their mortality, their humanity in the face of stronger forces. His manner of narration is forthright and clear, as is his language. The puns he uses resonate immediately with the rest of the company because they refer to situations and feelings they can recognize in their own experience; indeed they are common to all human experience. Dioneo has an incredibly strong command of language in communicating with exact intention - he can do so without thought, "naturally," while the other members of the troupe are most recognizably self-aware of themselves in the position of narrator. For this reason, one could argue that Dioneo is, in actuality, the ruling narrator of the Decameron, disguising - and at the same time revealing - this role through his position each day as the final narrator. That he holds the greatest power becomes clear by way of his effective and confident storytelling.

Dioneo is the personification of freedom. He is an anarchic figure, though not an extremist. We should not forget the "urbanity" of the Decameron, and the crucial importance of social interaction among the members of the brigata. Absolute lack of conformity and compromise would mean for Dioneo isolation, as any social interaction requires some degree of conformity to or acceptance of the rules. Although he represents the "pleasure principle," Dioneo is also the embodiment of a social necessity, he is an integral part of the brigata' s "utopian" society. His narration - unfettered as it is by the thematic constraints imposed upon the others - could fairly be seen as a metaphor for a sort of "liberation of the repressed" within the framework of the Decameron, a safety valve for the frustrations and anxiety of his society at large.

Lauretta

Lauretta, the name given by Boccaccio to one of the female narrators, implies Justice. The defining characteristic of Lauretta is the way in which that Justice is meted out. In her world view, women should obey men.

Emilia

Narrative functions

In "Framing Boccaccio," Patrick Rumble discusses the similar roles of Dioneo and Emilia. On the first day, Queen Pampinea, granting Dioneo's request to tell whatever story he pleases and, in exchange, to be the last storyteller of each day, reflects that "if the company should grow weary of hearing people talk, he could enliven the proceedings with some story that would move them to laughter" (First Day, Conclusion). Rumble points out that thus "Dioneo adopts the structural function of the transgressor, the one unbound by the laws of the group, precisely to maintain the integrity and stability of the small community. Dioneo reveals that the exercise of the law, indeed the very possibility of legislation or rule-making within a society, is dependent upon the transgression that legitimates it" (p. 111).

Emilia draws the brigata's attention to herself through her looks and narcissism; she often dances at the end of the days while the others sing, play instruments, and watch her. On the First Day, Emilia sings a song about love, as the other narrators will do in turn. The song begins (First Day, Conclusion):

"In mine own beauty take I such delight

That to no other love could I

My fond affections plight.

Since in my looking-glass each hour I spy

Beauty enough to satisfy the mind,

Why seek out past delights, or new ones try

When all content within my glass I find?"

Clearly, Emilia is presented as a narcissist. Boccaccio casts Emilia as an object to be viewed and desired.

Panfilo

Panfilo - lover of all. Panfilo would seem to be one of the simplest characters in the brigata:

Love, I take such delight in thee,

And find such joy and pleasure in thy name,

That I am happy burning in your flame.

Panfilo is in love with love, in love with joy. Though it would at first appear that Panfilo is in the brigata simply to fulfill the slap-happy-fool-in-love role, a second look at his novelle reveals another side of Panfilo. Panfilo repeatedly emphasizes the need to look deeper into the stories of the brigata by presenting characters and situations which hide their true nature. Indeed, Panfilo acts as an almost direct voice of Boccaccio, in that he reminds us that the Decameron is not simply a collection of entertaining stories. It is Boccaccio's intention that we look deeper into the stories of the Decameron, so that it becomes a vehicle from which "useful advice" can be gleaned.

Panfilo begins the Decameron with a story about Cepparello (I.1), a scoundrel and usurer who, through a skillful confession on his death bed, becomes glorified as a saint. We can see from this story that, unless we want to look as silly as the townsfolk who considered Cepparello a saint, it is important to look deeper into things before judging their meaning. This translates easily into looking deeper into the stories of the Decameron. When Panfilo ends his first story by saying how wonderful God is because God can transmit His message through even the worst sinner, it appears that Panfilo is going to end all of his tales with a gay and positive moral. Instead, the theme that Panfilo comes back to time and time again is the "Don't judge a book by its cover" theme - a particularly apt proverb considering the medium in which he exists.

◦Pampinea

◦Filomena

◦Neifile

◦Filostrato

◦Fiammetta

◦Elissa

◦Dioneo

◦Lauretta

◦Emilia

◦Panfilo

The group of ten Florentine youths, known as the “brigata,” comprises seven women and three men, each of whom has an allegorical role. McWilliam writes that the women probably represent the four cardinal virtues (Prudence, Justice, Temperance, and Fortitude) and the three theological virtues (Faith, Hope, and Love) [15]. The men are the three could represent the tripartite division of the soul into Reason, Anger, and Lust. The author writes in the Introduction that he has withheld the true names of the members of the brigata, because he doesn’t want them to “feel embarrassed, at any time in the future, on account of the ensuing stories, all of which they either listened to or narrated themselves [16]. The translations of the Italian names of the members of the Brigata, with their possible allegorical roles, is as follows [17]:

Pampinea-full of vigor (Prudence) Fiammetta-little flame (Temperance) Filomena-the beloved, or lover of song (Fortitude) Emilia-she who allures (Faith) Elissa-an Italian variant on Dido (Hope) Neifile-newly enamored, possibly a reference to the dolce stil novo and Dante (Charity) Lauretta-a diminutive of Petrach’s Laura (Justice) Panfilo-all-loving (Reason) Filostrato- defeated by love (Anger) Dioneo-an italianized version of Dionysus (Lust)

Notes that don't have spoilers:

Pampinea

Pampinea, the eldest of the seven lady narrators at twenty-seven years of age, is the natural leader among them. In Italian her name means "la rigogliosa" which could be translated as "the flourishing one." It was her suggestion for the group to move to the countryside and her initiative that brought the three men into their plans. In return, she was made Queen of the first day.

Neifile

Appearance: young, beautiful, charming, elegant, cheerful.

"Neifile whose manners were no less striking than her beauty, replied with a smile..." (I.2).

Fiammetta

Several scholars of Boccaccio like to believe that the Fiammetta of the brigata was based upon a real woman, Maria d'Aquino, with whom Boccaccio fell in love. "Fiammetta" is a recurring character in a number of Boccaccio's works (e.g., The Filocolo and L'elegia di Madonna Fiammetta ) and is generally described in consistent terms: "[her hair] is so blonde that the world holds nothing like it; it shades a white forehead of noble width, beneath which are the curves of two black and most slender eyebrows ... and under these two roguish eyes ... cheeks of no other colour than milk."

In the Decameron, Fiammetta is one of the most assertive women. She often engages Filostrato and others in competitive storytelling about the nature of love. She is a clever, independent and resourceful woman who admires these same qualities in others. Fiammetta often tells stories about tricksters and delights in tales about strong female characters. Her tone is largely positive, with the exception of her stories of the Fourth and Fifth Days.

Elissa

There has been much discussion concerning the significance of the names Boccaccio has given to his narrators - allegorical representations of the seven virtues, symbols of other moral qualities, or just characters that have populated Boccaccio's earlier works. It has been said that Elissa represents either "hope" (Kirkham) or "justice" (Ferrante) and also that she is very young and dominated by a violent passion. Paden suggests that she is the sole recognizable Ghibelline of the group.

The first glimpse of Elissa's character comes in the Introduction of the First Day in which Pampinea has suggested to the other women her plan for fleeing the city in order in an attempt to save their own lives and to return to a somewhat ordered and rational existence. Filomena agrees that this is a good idea but she believes since they are all women and, by nature, "fickle, quarrelsome, suspicious, cowardly, and easily frightened," they will never succeed in their venture.

It is here that Elissa speaks up: she agrees that women are unsuited and unable to act without male guidance but, she wonders, where will they find suitable male companions. She fears for the safety of the group and is concerned about any possible scandal related to traveling with a group of men.

Dioneo

In his introduction to I.4, the first story he tells, Dioneo expresses the opinion "that each must be allowed [...] to tell whatever story we think most likely to amuse." Consequently he will be granted the privilege not to follow the theme of the day and to tell instead the story that most pleases him, regardless of its consonance or dissonance with the others told in that day. In exchange, he will be the last of the ten narrators to tell a story. This positioning is significant because it is meant not to interfere with the pattern developed in a given day; on the contrary, Dioneo's privilege grants him a role of transgressor while at the same time, as an exception, reinforces the (narrative) rule that governs the Decameron.

Dioneo as Transgressor

Within the space of their paradisiac seclusion from reality, death and disease, Dioneo reminds the brigata of their mortality, their humanity in the face of stronger forces. His manner of narration is forthright and clear, as is his language. The puns he uses resonate immediately with the rest of the company because they refer to situations and feelings they can recognize in their own experience; indeed they are common to all human experience. Dioneo has an incredibly strong command of language in communicating with exact intention - he can do so without thought, "naturally," while the other members of the troupe are most recognizably self-aware of themselves in the position of narrator. For this reason, one could argue that Dioneo is, in actuality, the ruling narrator of the Decameron, disguising - and at the same time revealing - this role through his position each day as the final narrator. That he holds the greatest power becomes clear by way of his effective and confident storytelling.

Dioneo is the personification of freedom. He is an anarchic figure, though not an extremist. We should not forget the "urbanity" of the Decameron, and the crucial importance of social interaction among the members of the brigata. Absolute lack of conformity and compromise would mean for Dioneo isolation, as any social interaction requires some degree of conformity to or acceptance of the rules. Although he represents the "pleasure principle," Dioneo is also the embodiment of a social necessity, he is an integral part of the brigata' s "utopian" society. His narration - unfettered as it is by the thematic constraints imposed upon the others - could fairly be seen as a metaphor for a sort of "liberation of the repressed" within the framework of the Decameron, a safety valve for the frustrations and anxiety of his society at large.

Lauretta

Lauretta, the name given by Boccaccio to one of the female narrators, implies Justice. The defining characteristic of Lauretta is the way in which that Justice is meted out. In her world view, women should obey men.

Emilia

Narrative functions

In "Framing Boccaccio," Patrick Rumble discusses the similar roles of Dioneo and Emilia. On the first day, Queen Pampinea, granting Dioneo's request to tell whatever story he pleases and, in exchange, to be the last storyteller of each day, reflects that "if the company should grow weary of hearing people talk, he could enliven the proceedings with some story that would move them to laughter" (First Day, Conclusion). Rumble points out that thus "Dioneo adopts the structural function of the transgressor, the one unbound by the laws of the group, precisely to maintain the integrity and stability of the small community. Dioneo reveals that the exercise of the law, indeed the very possibility of legislation or rule-making within a society, is dependent upon the transgression that legitimates it" (p. 111).

Emilia draws the brigata's attention to herself through her looks and narcissism; she often dances at the end of the days while the others sing, play instruments, and watch her. On the First Day, Emilia sings a song about love, as the other narrators will do in turn. The song begins (First Day, Conclusion):

"In mine own beauty take I such delight

That to no other love could I

My fond affections plight.

Since in my looking-glass each hour I spy

Beauty enough to satisfy the mind,

Why seek out past delights, or new ones try

When all content within my glass I find?"

Clearly, Emilia is presented as a narcissist. Boccaccio casts Emilia as an object to be viewed and desired.

Panfilo

Panfilo - lover of all. Panfilo would seem to be one of the simplest characters in the brigata:

Love, I take such delight in thee,

And find such joy and pleasure in thy name,

That I am happy burning in your flame.

Panfilo is in love with love, in love with joy. Though it would at first appear that Panfilo is in the brigata simply to fulfill the slap-happy-fool-in-love role, a second look at his novelle reveals another side of Panfilo. Panfilo repeatedly emphasizes the need to look deeper into the stories of the brigata by presenting characters and situations which hide their true nature. Indeed, Panfilo acts as an almost direct voice of Boccaccio, in that he reminds us that the Decameron is not simply a collection of entertaining stories. It is Boccaccio's intention that we look deeper into the stories of the Decameron, so that it becomes a vehicle from which "useful advice" can be gleaned.

Panfilo begins the Decameron with a story about Cepparello (I.1), a scoundrel and usurer who, through a skillful confession on his death bed, becomes glorified as a saint. We can see from this story that, unless we want to look as silly as the townsfolk who considered Cepparello a saint, it is important to look deeper into things before judging their meaning. This translates easily into looking deeper into the stories of the Decameron. When Panfilo ends his first story by saying how wonderful God is because God can transmit His message through even the worst sinner, it appears that Panfilo is going to end all of his tales with a gay and positive moral. Instead, the theme that Panfilo comes back to time and time again is the "Don't judge a book by its cover" theme - a particularly apt proverb considering the medium in which he exists.

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Members of the Brigata

◦

The group of ten Florentine youths, known as the “brigata,” comprises seven wo..."

I like this list... during the First Day, it is hard to create a personality for each of the ten narrators.

◦

The group of ten Florentine youths, known as the “brigata,” comprises seven wo..."

I like this list... during the First Day, it is hard to create a personality for each of the ten narrators.

Rowena wrote: "Reem, thanks for the notes. How interesting!"

Good to see you Rowena! I will add more notes as our reading progresses.

Good to see you Rowena! I will add more notes as our reading progresses.

Thank you! I started reading the book last night and I hope to catch up soon. So far it's been very interesting:)

Thank you! I started reading the book last night and I hope to catch up soon. So far it's been very interesting:)

Rowena wrote: "Thank you! I started reading the book last night and I hope to catch up soon. So far it's been very interesting:)"

Wonderful! You should catch up fast. I've been waiting for you to post in the threads.

Wonderful! You should catch up fast. I've been waiting for you to post in the threads.

Introduction to Boccaccio

Boccaccio's Life: Boccaccio made a point of presenting himself by giving details of his life. However, his account may be the most unreliable. In fact, being a master of storytelling, chances are that he made his life conform to the character he made of himself.

He says that he was born in Paris, a fruit of a secret love affair his father had with the king's daughter. Then, as his father moved back to Florence, he was brought along and destined to live with a cruel stepmother.

But he was able to get away from all of this when he went to live in Naples, where he was supposed to study accounting, since his father wanted him to be a merchant.

Here in Naples, he met Fiammetta, an illegitimate daughter of the king of Naples: this was a very difficult love because supposedly she was being unfaithful to him. Nevertheless, Boccaccio says that he became a poet and storyteller because of her.

However, the facts are quite different. Very likely, Giovanni Boccaccio was born in Florence, from a widow who had an affair with Boccaccio's father. And Fiammetta was a daughter of a noblewoman from Naples, wife of a rich merchant, and expert in the matters of love.

Boccaccio's family came from the town of Certaldo, his father was Boccaccio da Chellino, who moved to Florence to practice the profession of merchant. In fact, we know that in 1310 he was working for the Bardi Financial House, one of the most important financial institution in Europe. His employment lasted until 1342, when the institution went bankrupt.

As such he was in Paris a few times, including the time of Giovanni's birth (1313). However, it is certain that his son was born in Florence (or perhaps in Certaldo) from this affair in the latter part of the year 1313.

Later, in 1320, Boccaccio's father married a lady called Margherita dei Mondali (the famous stepmother), who was a relative of Beatrice Portinari, loved by Dante a few years earlier. Hence Boccaccio's interest for Dante's works.

Boccaccio did go to Naples around 1325 where he lived at the court of the kings of Naples, supported by the Bardi financial institution, with the specific purpose of getting the training needed to be a merchant.

Naples was at the time one of the most influential political and economical centers in Europe. Here Boccaccio heard stories of incredible travels, which, along with the environment of the city, inspired some of the best stories of his major work, The Decameron.

This leisurely life is present mostly in his youthful works, such as Filocolo, Ameto, Fiammetta, in which one can feel an intense passion for life.

Meanwhile, Boccaccio studies Mathematics and Arithmetic for his future career, although he cares little for these studies. He prefers poetry and other academic subjects. In fact he will say that he wasted time studying mathematics.

His life in Naples was easy. He lived in a fairy-tale world, with no financial worries. He was in the environment of merchants, it is the middle class society that he got to know so well.

His stay in Naples lasted until 1340, enough time to assimilate the intellectual culture of the time. In a way he learned from real life, and not from schooling. Here he studied medieval lyric poetry (Provençal, Italian, and Dante). In this environment he invented his passionate love story centered on a gentlewoman called Fiammetta. In fact she is present in most of his works up to and including The Decameron.

These early works are based on conventional writing forms of the time, mostly epic narrative. Herre they are:

Filocolo: the story of Florio and Biancifiore (1336);

Filostrato, the story of Troilo and Griselda, from the French Roman de Troie, later imitated by Chaucer and Shakespeare in their Troilus and Cressida.

Teseida, in 12 cantos, an epic poem written in 1340-41, which tells the story of Theseus's deeds against Thebe and the Amazons. But the plot is an excuse for Boccaccio to describe a triangle love affair that put against each other Arcita and Palemone, who are both in love with Emilia, a sister of Ippolita who was Theseus's wife. This story became the plot of Chaucer's Knight's Tale, in the Canterbury Tales.

Later he wrote other minor books of prose and poetry, some of them with allegorical meanings. Among those, one stands out: Elegia di Madonna Fiammetta, which portrays the state of mind of a woman in love as she is betrayed by her lover. This is part of Boccaccio's fictional account of his love misadventures.

About this time he was forced to return to Florence because the financial institution of the Bardi went bankrupt, and the source of his income vanished. This was a sour turn of events for Boccaccio. His happy life ended. And so his works changed style, reflecting these changes. His happiness was over, and he would always feel nostalgia for the happy time spent in Naples.

The financially difficult years between 1342 and 1348 were crucial for his literary career. However, his economical difficulties did not destroy his interests for creative writing. In Florence, he comes in contact with the Florentine intellectual circles, and his artistic writings become more "realistic," meaning that he turned his attention to everyday life. In the meantime he travels throughout North Italy.

During these travels Boccaccio observes Nature, which is portrayed in his Ninfale fiesolano, the last verso work before the The Decameron.

In 1348 he is in Florence, where he witnesses the black death, a bubonic plague that hit Europe and killed more than half of the population, especially in cities. The effect of the black death is described in the Introduction to the Decameron. After these events he remains in Florence to administer what's left of the family business.

Between 1348 and 1351 Boccaccio writes the Decameron.

Then Boccaccio undergoes a religious crisis, which will affect his writings from then on. In fact, he turns to the official culture, obviously influenced by Petrarch, whom he met as he was traveling. When he was in Romagna, he also met Dante's daughter, who was in the monastery of Santo Stefano, in Ravenna.

At this time he became a diplomat, traveling all over. Among his assignments, he was the one who represented Florence, when in 1365, the Pope returned to Rome from Avignon.

Throughout these years he feels disappointed by the way he lives, especially because he has little money. He retires in the town of Certaldo to get away from Florence. Here many humanist scholars visit him, as he is already a legend. And during these years, following Petrarch's lead, he writes many scholarly books.

In the meantime, he becomes a deacon, with the purpose to straighten up the souls of the sinners. This is Christian Humanism.

Most of the works written during these years were in Latin, however, he wrote Corbaccio in Italian. This is a book to chastise women (in the early 50's). In this book he criticizes the nature and behavior of women, a definite shift from the free-spirited Decameron.

Later in life he wrote also, in Italian, two books on Dante: a Life of Dante and a series of lessons on the Inferno. He was giving these lectures in a Florentine church.

But, as mentioned, the majority of the writing done between 1350 and his death in 1374 was in Latin: the most important is Genealogia Deorum Gentilium, a dictionary of mythology. He began this book in 1350, and kept working on it until he died. In this book (chpt.15 and 16, Boccaccio defends his theories of poetry -- a similar defense is present in the introduction to the fourth day of the Decameron).

He also wrote:

Bucolicum Carmen (1351-66): allegorical poems based on contemporary events. Here Boccaccio follows the same pattern begun by Dante and employed by Petrarch.

De Claribus Mulieribus (1360-74): a collection of lives of the most famous women from ancient times to Middle Ages (parallel to Petrarch's book on the most illustrious men).

De Montibus, silvis, fontibus (1355-74): on the geographic culture of the time.

De Casibus Virorum Illustrium (1355-74): to show the vanity of earthly wealth.

Boccaccio's Life: Boccaccio made a point of presenting himself by giving details of his life. However, his account may be the most unreliable. In fact, being a master of storytelling, chances are that he made his life conform to the character he made of himself.

He says that he was born in Paris, a fruit of a secret love affair his father had with the king's daughter. Then, as his father moved back to Florence, he was brought along and destined to live with a cruel stepmother.

But he was able to get away from all of this when he went to live in Naples, where he was supposed to study accounting, since his father wanted him to be a merchant.

Here in Naples, he met Fiammetta, an illegitimate daughter of the king of Naples: this was a very difficult love because supposedly she was being unfaithful to him. Nevertheless, Boccaccio says that he became a poet and storyteller because of her.

However, the facts are quite different. Very likely, Giovanni Boccaccio was born in Florence, from a widow who had an affair with Boccaccio's father. And Fiammetta was a daughter of a noblewoman from Naples, wife of a rich merchant, and expert in the matters of love.

Boccaccio's family came from the town of Certaldo, his father was Boccaccio da Chellino, who moved to Florence to practice the profession of merchant. In fact, we know that in 1310 he was working for the Bardi Financial House, one of the most important financial institution in Europe. His employment lasted until 1342, when the institution went bankrupt.

As such he was in Paris a few times, including the time of Giovanni's birth (1313). However, it is certain that his son was born in Florence (or perhaps in Certaldo) from this affair in the latter part of the year 1313.

Later, in 1320, Boccaccio's father married a lady called Margherita dei Mondali (the famous stepmother), who was a relative of Beatrice Portinari, loved by Dante a few years earlier. Hence Boccaccio's interest for Dante's works.

Boccaccio did go to Naples around 1325 where he lived at the court of the kings of Naples, supported by the Bardi financial institution, with the specific purpose of getting the training needed to be a merchant.

Naples was at the time one of the most influential political and economical centers in Europe. Here Boccaccio heard stories of incredible travels, which, along with the environment of the city, inspired some of the best stories of his major work, The Decameron.

This leisurely life is present mostly in his youthful works, such as Filocolo, Ameto, Fiammetta, in which one can feel an intense passion for life.

Meanwhile, Boccaccio studies Mathematics and Arithmetic for his future career, although he cares little for these studies. He prefers poetry and other academic subjects. In fact he will say that he wasted time studying mathematics.

His life in Naples was easy. He lived in a fairy-tale world, with no financial worries. He was in the environment of merchants, it is the middle class society that he got to know so well.

His stay in Naples lasted until 1340, enough time to assimilate the intellectual culture of the time. In a way he learned from real life, and not from schooling. Here he studied medieval lyric poetry (Provençal, Italian, and Dante). In this environment he invented his passionate love story centered on a gentlewoman called Fiammetta. In fact she is present in most of his works up to and including The Decameron.

These early works are based on conventional writing forms of the time, mostly epic narrative. Herre they are:

Filocolo: the story of Florio and Biancifiore (1336);

Filostrato, the story of Troilo and Griselda, from the French Roman de Troie, later imitated by Chaucer and Shakespeare in their Troilus and Cressida.

Teseida, in 12 cantos, an epic poem written in 1340-41, which tells the story of Theseus's deeds against Thebe and the Amazons. But the plot is an excuse for Boccaccio to describe a triangle love affair that put against each other Arcita and Palemone, who are both in love with Emilia, a sister of Ippolita who was Theseus's wife. This story became the plot of Chaucer's Knight's Tale, in the Canterbury Tales.

Later he wrote other minor books of prose and poetry, some of them with allegorical meanings. Among those, one stands out: Elegia di Madonna Fiammetta, which portrays the state of mind of a woman in love as she is betrayed by her lover. This is part of Boccaccio's fictional account of his love misadventures.

About this time he was forced to return to Florence because the financial institution of the Bardi went bankrupt, and the source of his income vanished. This was a sour turn of events for Boccaccio. His happy life ended. And so his works changed style, reflecting these changes. His happiness was over, and he would always feel nostalgia for the happy time spent in Naples.

The financially difficult years between 1342 and 1348 were crucial for his literary career. However, his economical difficulties did not destroy his interests for creative writing. In Florence, he comes in contact with the Florentine intellectual circles, and his artistic writings become more "realistic," meaning that he turned his attention to everyday life. In the meantime he travels throughout North Italy.

During these travels Boccaccio observes Nature, which is portrayed in his Ninfale fiesolano, the last verso work before the The Decameron.

In 1348 he is in Florence, where he witnesses the black death, a bubonic plague that hit Europe and killed more than half of the population, especially in cities. The effect of the black death is described in the Introduction to the Decameron. After these events he remains in Florence to administer what's left of the family business.

Between 1348 and 1351 Boccaccio writes the Decameron.

Then Boccaccio undergoes a religious crisis, which will affect his writings from then on. In fact, he turns to the official culture, obviously influenced by Petrarch, whom he met as he was traveling. When he was in Romagna, he also met Dante's daughter, who was in the monastery of Santo Stefano, in Ravenna.

At this time he became a diplomat, traveling all over. Among his assignments, he was the one who represented Florence, when in 1365, the Pope returned to Rome from Avignon.

Throughout these years he feels disappointed by the way he lives, especially because he has little money. He retires in the town of Certaldo to get away from Florence. Here many humanist scholars visit him, as he is already a legend. And during these years, following Petrarch's lead, he writes many scholarly books.

In the meantime, he becomes a deacon, with the purpose to straighten up the souls of the sinners. This is Christian Humanism.

Most of the works written during these years were in Latin, however, he wrote Corbaccio in Italian. This is a book to chastise women (in the early 50's). In this book he criticizes the nature and behavior of women, a definite shift from the free-spirited Decameron.

Later in life he wrote also, in Italian, two books on Dante: a Life of Dante and a series of lessons on the Inferno. He was giving these lectures in a Florentine church.

But, as mentioned, the majority of the writing done between 1350 and his death in 1374 was in Latin: the most important is Genealogia Deorum Gentilium, a dictionary of mythology. He began this book in 1350, and kept working on it until he died. In this book (chpt.15 and 16, Boccaccio defends his theories of poetry -- a similar defense is present in the introduction to the fourth day of the Decameron).

He also wrote:

Bucolicum Carmen (1351-66): allegorical poems based on contemporary events. Here Boccaccio follows the same pattern begun by Dante and employed by Petrarch.

De Claribus Mulieribus (1360-74): a collection of lives of the most famous women from ancient times to Middle Ages (parallel to Petrarch's book on the most illustrious men).

De Montibus, silvis, fontibus (1355-74): on the geographic culture of the time.

De Casibus Virorum Illustrium (1355-74): to show the vanity of earthly wealth.

The Decameron

Dedication: Boccaccio writes this book for women. This is one of the revolutionary element of the book. Why women? Because, says Boccaccio, they are being wrongfully neglected. They have no saying in shaping their destinies, they have no outlet to express their feelings, they are left in their castles by their fathers, brothers, husbands with nothing to do. [Obviously Boccaccio is talking about the women of the nobility]

The background for this book is the black death of 1348, which killed a large number of people in Florence. Within this environment Boccaccio creates the structure of the book.

The premise: The black death is terrorizing the city of Florence, and is causing a complete breakdown of all moral values. Surrounded by this horrible death, people loose respect for each other. Boccaccio is, for all purposes, describing what is happening as hell on earth. (He brought to earth what Dante had placed in the Inferno)

Within this dissolution, one Spring morning seven young ladies meet in a church where they went to pray. Soon they put their prayers aside and turn to a more pragmatic topic: how to survive the rampant death. After considering various possibilities, they decide that it is their duty to preserve their lives by getting out of the city, and isolate themselves in the countryside, away from death. However, in their opinion, they will be successful only if they are joined by some men. (At this time women felt that a man's guidance was necessary).

In the meantime, three young men, friends and relatives to the ladies, enter the church, and are asked to go along. They agree, and the next morning they leave the city with a few of their servants who have survived death. They go to a beautiful country villa, and there they will wait for the pestilence to be over.

But in order for the group to function well, they decide that they need a ruler (king or queen). So, in a democratic fashion, the decide that each one of them will be king or queen for a day, and everyone will obey and follow his/her rules. They also decide to spent the time entertaining themselves, eating well, singing, dancing, and telling stories: one story each for each day.

These stories represent the content of the book. Therefore, we have ten stories for each day. These stories portray all aspects of society, form the most noble behavior to most vulgar and depraved. This is the world of the Decameron. Here we find merchants alongside with kings, clerics, and the common people.

It is a complete representation of human behavior. It is the "human comedy," where the real life becomes the centerpiece (Dante, instead, saw life from a distance). In fact the Decameron completes Dante's vision of life. This is humanity as it is actually behaving in everyday circumstances.

From this point of view, the Decameron does not belong, as it has been suggested, to the new culture centered on Petrarch. Rather it is more properly medieval, as it is encyclopedic in nature (like Dante's Commedia).

However, this work is what we consider today as politically incorrect. It disregards all rules of literature and accepted etiquette. As already mentioned, it is dedicated to women, written with the specific purpose to entertain them, as they are bored during long days with nothing to do. This is a very modern concept: the artist addresses and meets the needs of a specific audience.

In fact, the purpose of the book was so out of place that Boccaccio had practically all the intellectual establishment against him (see his defense in the Introduction to day 4). Even he himself, later in his life, denounced his own masterpiece. In fact, the scholars who immediately followed him admired his scholarly works, not the Decameron. It will take 150 years for the book to be recognized for its artistic, intellectual, and linguistic values.

On the other hand, this book was well received by an audience that was outside the official intelligentsia. It found a crowd of imitators already in its own time in writers who realized that there was an audience for narrative. In fact, the Decameron ended up as being one of the most imitated books in history. No one escaped Boccaccio's influence: he set the rules for story-telling. His presence is felt in the entire Europe, in English literature his influence is felt by many, to name just two, Chaucer and Shakespeare.

With the Decameron, Boccaccio takes the short story and makes it come to life. His characters are, in fact, psychologically alive; he gives the plot and the characters an evolutionary development. In short, he took a minor art form -- telling short anecdotal stories, and created an artistic form.

The Decameron, contrary to other collections of stories of the time, is not a series of unrelated plots. Here, each story becomes a part of the whole. These stories are complete in themselves, and yet they add to the completeness of the book. The stories are in fact grouped by themes and by authorship (the story-tellers). Each day covers a specific theme.

The external structure (the ten young people escaping death to preserve life) is itself a story which contains all other stories; some individual stories have their own stories within, etc. Each story is characterized by the person who tells it. For examples, Dioneo (one of the ten) reserves his position to be the last one to tell his story so that he can be free to close the day with his peculiar tales that do not necessary follow to the themes of the day. Chaucer's Canterbury Tales uses the same concept of a large story as the framework which includes all other stories. The frame-story will be a description of a pilgrimage to Canterbury during which the characters tell their stories.

And at the center of this world we find humanity, in all its variety. People are seen as victim of jokes, victims to human cruelty, or survivor to misfortunes, etc. But what stands out in all this is the triumph of intelligence (mostly in day 6).

Dedication: Boccaccio writes this book for women. This is one of the revolutionary element of the book. Why women? Because, says Boccaccio, they are being wrongfully neglected. They have no saying in shaping their destinies, they have no outlet to express their feelings, they are left in their castles by their fathers, brothers, husbands with nothing to do. [Obviously Boccaccio is talking about the women of the nobility]

The background for this book is the black death of 1348, which killed a large number of people in Florence. Within this environment Boccaccio creates the structure of the book.

The premise: The black death is terrorizing the city of Florence, and is causing a complete breakdown of all moral values. Surrounded by this horrible death, people loose respect for each other. Boccaccio is, for all purposes, describing what is happening as hell on earth. (He brought to earth what Dante had placed in the Inferno)

Within this dissolution, one Spring morning seven young ladies meet in a church where they went to pray. Soon they put their prayers aside and turn to a more pragmatic topic: how to survive the rampant death. After considering various possibilities, they decide that it is their duty to preserve their lives by getting out of the city, and isolate themselves in the countryside, away from death. However, in their opinion, they will be successful only if they are joined by some men. (At this time women felt that a man's guidance was necessary).

In the meantime, three young men, friends and relatives to the ladies, enter the church, and are asked to go along. They agree, and the next morning they leave the city with a few of their servants who have survived death. They go to a beautiful country villa, and there they will wait for the pestilence to be over.

But in order for the group to function well, they decide that they need a ruler (king or queen). So, in a democratic fashion, the decide that each one of them will be king or queen for a day, and everyone will obey and follow his/her rules. They also decide to spent the time entertaining themselves, eating well, singing, dancing, and telling stories: one story each for each day.

These stories represent the content of the book. Therefore, we have ten stories for each day. These stories portray all aspects of society, form the most noble behavior to most vulgar and depraved. This is the world of the Decameron. Here we find merchants alongside with kings, clerics, and the common people.

It is a complete representation of human behavior. It is the "human comedy," where the real life becomes the centerpiece (Dante, instead, saw life from a distance). In fact the Decameron completes Dante's vision of life. This is humanity as it is actually behaving in everyday circumstances.

From this point of view, the Decameron does not belong, as it has been suggested, to the new culture centered on Petrarch. Rather it is more properly medieval, as it is encyclopedic in nature (like Dante's Commedia).

However, this work is what we consider today as politically incorrect. It disregards all rules of literature and accepted etiquette. As already mentioned, it is dedicated to women, written with the specific purpose to entertain them, as they are bored during long days with nothing to do. This is a very modern concept: the artist addresses and meets the needs of a specific audience.

In fact, the purpose of the book was so out of place that Boccaccio had practically all the intellectual establishment against him (see his defense in the Introduction to day 4). Even he himself, later in his life, denounced his own masterpiece. In fact, the scholars who immediately followed him admired his scholarly works, not the Decameron. It will take 150 years for the book to be recognized for its artistic, intellectual, and linguistic values.

On the other hand, this book was well received by an audience that was outside the official intelligentsia. It found a crowd of imitators already in its own time in writers who realized that there was an audience for narrative. In fact, the Decameron ended up as being one of the most imitated books in history. No one escaped Boccaccio's influence: he set the rules for story-telling. His presence is felt in the entire Europe, in English literature his influence is felt by many, to name just two, Chaucer and Shakespeare.

With the Decameron, Boccaccio takes the short story and makes it come to life. His characters are, in fact, psychologically alive; he gives the plot and the characters an evolutionary development. In short, he took a minor art form -- telling short anecdotal stories, and created an artistic form.

The Decameron, contrary to other collections of stories of the time, is not a series of unrelated plots. Here, each story becomes a part of the whole. These stories are complete in themselves, and yet they add to the completeness of the book. The stories are in fact grouped by themes and by authorship (the story-tellers). Each day covers a specific theme.

The external structure (the ten young people escaping death to preserve life) is itself a story which contains all other stories; some individual stories have their own stories within, etc. Each story is characterized by the person who tells it. For examples, Dioneo (one of the ten) reserves his position to be the last one to tell his story so that he can be free to close the day with his peculiar tales that do not necessary follow to the themes of the day. Chaucer's Canterbury Tales uses the same concept of a large story as the framework which includes all other stories. The frame-story will be a description of a pilgrimage to Canterbury during which the characters tell their stories.

And at the center of this world we find humanity, in all its variety. People are seen as victim of jokes, victims to human cruelty, or survivor to misfortunes, etc. But what stands out in all this is the triumph of intelligence (mostly in day 6).

An interesting article to read after our recent discoveries of "appropriation"...

What Is Literature?

In defense of the canon

http://harpers.org/archive/2014/03/wh...

What Is Literature?

In defense of the canon

http://harpers.org/archive/2014/03/wh...

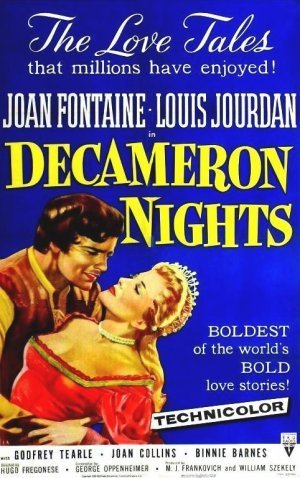

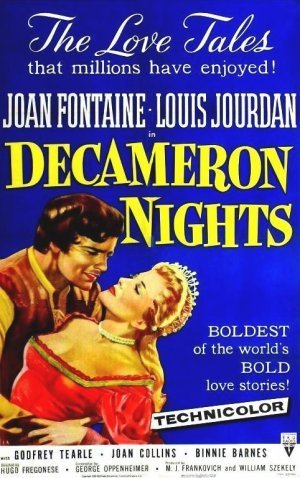

Kalli, were you aware that there was a movie about Fiammetta?

Decameron Nights is a 1953 anthology film based on three tales from The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio, specifically the ninth and tenth tales of the second day and the ninth tale of the third. It stars Joan Fontaine and, as Boccaccio, Louis Jourdan.

Decameron Nights is a 1953 anthology film based on three tales from The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio, specifically the ninth and tenth tales of the second day and the ninth tale of the third. It stars Joan Fontaine and, as Boccaccio, Louis Jourdan.

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Kalli, were you aware that there was a movie about Fiammetta?

Decameron Nights is a 1953 anthology film based on three tales from The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio, specifically the ninth and..."

HaHa.. the things you find... This could be hilarious.

Decameron Nights is a 1953 anthology film based on three tales from The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio, specifically the ninth and..."

HaHa.. the things you find... This could be hilarious.

If anyone is interested in knowing beforehand the theme for each day, have a look at this list:

The Decameron is a collection of 100 tales by Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio written between 1350 and 1353. It is a medieval allegorical work best known for its bawdy tales of love, appearing in all its possibilities from the erotic to the tragic. Many notable writers such as Shakespeare and Chaucer are said to have borrowed from it. The tale begins with 7 women and 3 men who move to a country villa to escape the Black Death in Florence. The group stays there for fourteen days and on ten of those days they each tell one tale on a set theme. Each day a different person is King or Queen and they decide what the theme will be. One character Dioneo, who usually tells the tenth tale each day, has the right to tell a tale on any topic he wishes, due to his wit.

http://listverse.com/2007/12/10/10-da...

1. Day Under the rule of Pampinea, the first day of story telling is open topic. Although there is no assigned theme of the tales this first day, six deal with one person censuring another and four are satires of the Catholic Church.

2. Day Two

Filomea reigns during the second day and she assigns a topic to each of the storytellers: Misadventures that suddenly end happily.

and so on...

The Decameron is a collection of 100 tales by Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio written between 1350 and 1353. It is a medieval allegorical work best known for its bawdy tales of love, appearing in all its possibilities from the erotic to the tragic. Many notable writers such as Shakespeare and Chaucer are said to have borrowed from it. The tale begins with 7 women and 3 men who move to a country villa to escape the Black Death in Florence. The group stays there for fourteen days and on ten of those days they each tell one tale on a set theme. Each day a different person is King or Queen and they decide what the theme will be. One character Dioneo, who usually tells the tenth tale each day, has the right to tell a tale on any topic he wishes, due to his wit.

http://listverse.com/2007/12/10/10-da...

1. Day Under the rule of Pampinea, the first day of story telling is open topic. Although there is no assigned theme of the tales this first day, six deal with one person censuring another and four are satires of the Catholic Church.

2. Day Two

Filomea reigns during the second day and she assigns a topic to each of the storytellers: Misadventures that suddenly end happily.

and so on...

We have the 7 women of the Decameron....

Religious significance of the number seven:

http://www.biblestudy.org/bibleref/me...

http://www.studying-islam.org/forum/t...

http://www.myjewishlearning.com/belie...

Religious significance of the number seven:

http://www.biblestudy.org/bibleref/me...

http://www.studying-islam.org/forum/t...

http://www.myjewishlearning.com/belie...

Has this been posted before?:

The Decameron. The title itself is Greek and means "10 Days" (Deca-hemeron)

The Decameron. The title itself is Greek and means "10 Days" (Deca-hemeron)

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Has this been posted before?:

The Decameron. The title itself is Greek and means "10 Days" (Deca-hemeron)"

I knew the Deca part...!!

The Decameron. The title itself is Greek and means "10 Days" (Deca-hemeron)"

I knew the Deca part...!!

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Has this been posted before?:

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Has this been posted before?: The Decameron. The title itself is Greek and means "10 Days" (Deca-hemeron)"

I figured that "deca" means 10, wasn't sure what hemeron meant. Boccaccio sure did like numbers!

These days I am reading Florence: A Portrait and I come upon this:

In 1432 a new magistracy had been created.. whose business was specifically to deal with.. preserving purity among nuns...

This made me think of Boccaccio.. and then later on, I read:

Some incidents that Boccaccio might have liked to put into The Decameron are documented among the cases that arose. A certain Michele di Piero Mangioni, employed as a mason, gained access to a convent in San Miniato through his work and started an affair with a nun. when he decided to confess his sins to an Augustinian friar he ingeniously disguised himself as a fellow-friar, and in that habit managed to enter the convent again.

In 1432 a new magistracy had been created.. whose business was specifically to deal with.. preserving purity among nuns...

This made me think of Boccaccio.. and then later on, I read:

Some incidents that Boccaccio might have liked to put into The Decameron are documented among the cases that arose. A certain Michele di Piero Mangioni, employed as a mason, gained access to a convent in San Miniato through his work and started an affair with a nun. when he decided to confess his sins to an Augustinian friar he ingeniously disguised himself as a fellow-friar, and in that habit managed to enter the convent again.

I'm not sure where I posted about the Arabian Nights/ Alf Layla wa Layla read where I thought it might be too soon to read the Arabian Nights after the Decameron being that we are sort of struggling to keep up with these types of tales.

Anyway, I picked up O Alquimista/ The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho to read yesterday not knowing it has a cult following. I was intrigued that Coelho would write a rather Islamic-themed novel, and yes it is very much like The Secret as self-help genre which would explain its popularity(becoming one of the best-selling books in history and setting the Guinness World Record for most translated book by a living author).

Well further research reveals:

One of the chief complaints lodged against the book is that the story, praised for its fable-like simplicity, actually is a fable — A RETELLING of "The Ruined Man who Became Rich Again through a Dream" (Tale 14 from the collection One Thousand and One Nights).

Coelho, however, does not credit this source text anywhere in the book or in the preface, passing the story as an original work of fiction.

Also the life story of Takkeci Ibrahim Aga who is believed to live in Istanbul during the 1500s, has the same plot. So too does the English folk tale, the Pedlar of Swaffham.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/burt1...

Another BORROWING, and maybe " an omen" that we should stick to our original schedule. lol

Anyway, I picked up O Alquimista/ The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho to read yesterday not knowing it has a cult following. I was intrigued that Coelho would write a rather Islamic-themed novel, and yes it is very much like The Secret as self-help genre which would explain its popularity(becoming one of the best-selling books in history and setting the Guinness World Record for most translated book by a living author).

Well further research reveals:

One of the chief complaints lodged against the book is that the story, praised for its fable-like simplicity, actually is a fable — A RETELLING of "The Ruined Man who Became Rich Again through a Dream" (Tale 14 from the collection One Thousand and One Nights).

Coelho, however, does not credit this source text anywhere in the book or in the preface, passing the story as an original work of fiction.

Also the life story of Takkeci Ibrahim Aga who is believed to live in Istanbul during the 1500s, has the same plot. So too does the English folk tale, the Pedlar of Swaffham.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/burt1...

Another BORROWING, and maybe " an omen" that we should stick to our original schedule. lol

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "I'm not sure where I posted about the Arabian Nights/ Alf Layla wa Layla read where I thought it might be too soon to read the Arabian Nights after the Decameron being that we are sort of strugglin..."

Thank you Reem. I was not aware of Coelho's 'borrowing'. But he is not an author I would pick.

What do you mean by 'sticking to our original schedule?

Thank you Reem. I was not aware of Coelho's 'borrowing'. But he is not an author I would pick.

What do you mean by 'sticking to our original schedule?

Kalliope wrote:

What do you mean by 'sticking to our original schedule?

January 2015? Maybe a longer break after the Decameron?

What do you mean by 'sticking to our original schedule?

January 2015? Maybe a longer break after the Decameron?

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Kalliope wrote:

What do you mean by 'sticking to our original schedule?

January 2015? Maybe a longer break after the Decameron?"

Ok, so you mean the original plan is back.

I think we need a break, though, one or two months.

What do you mean by 'sticking to our original schedule?

January 2015? Maybe a longer break after the Decameron?"

Ok, so you mean the original plan is back.

I think we need a break, though, one or two months.

Kalliope wrote: "ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Kalliope wrote:

What do you mean by 'sticking to our original schedule?

January 2015? Maybe a longer break after the Decameron?"

Ok, so you mean the original plan i..."

I agree, if not even longer. Maybe 6 months? Anyone else like to weigh in on this? Are people really interested in reading the Arabian Nights?

Maybe we can bring "this cult following" to read along with us if interest in a tale like this is so popular!!!

What do you mean by 'sticking to our original schedule?

January 2015? Maybe a longer break after the Decameron?"

Ok, so you mean the original plan i..."

I agree, if not even longer. Maybe 6 months? Anyone else like to weigh in on this? Are people really interested in reading the Arabian Nights?

Maybe we can bring "this cult following" to read along with us if interest in a tale like this is so popular!!!

Being that this is our lounge, please forgive me for posting about another book in here. Kalli maybe we should create a lounge for the Arabian Nights. We meaning you, my dear.

Just read an article where Brazil's author Paulo Coelho writes about his love for Islam but no mention of The Arabian Nights.

"Paulo Coelho, the Brazilian writer who took the world stage with his thundering book The Alchemist, the source of inspiration for many around the world, told Syria's leading English-speaking magazine, Forward, his writings were influenced by the Sufi traditions of Islam.

Indeed, Sufism has inspired me a lot throughout my life and I refer to this tradition in some of my books such as The Alchemist and more recently The Zahir. Rumi is of course the first figure that springs to mind. His teachings and visions are incredibly subtle and clear," Coelho told Sami Moubayed, the Syrian political analyst and editor-in-chief of Forward Magazine.

When writing the Alchemist, Coelho was under the influence of Spirituality, which in his opinion came from curiosity. He believes that whether you like it or not life itself is a pilgrimage, a concept widely shared by Sufi thought and approach. "

Just read an article where Brazil's author Paulo Coelho writes about his love for Islam but no mention of The Arabian Nights.

"Paulo Coelho, the Brazilian writer who took the world stage with his thundering book The Alchemist, the source of inspiration for many around the world, told Syria's leading English-speaking magazine, Forward, his writings were influenced by the Sufi traditions of Islam.

Indeed, Sufism has inspired me a lot throughout my life and I refer to this tradition in some of my books such as The Alchemist and more recently The Zahir. Rumi is of course the first figure that springs to mind. His teachings and visions are incredibly subtle and clear," Coelho told Sami Moubayed, the Syrian political analyst and editor-in-chief of Forward Magazine.

When writing the Alchemist, Coelho was under the influence of Spirituality, which in his opinion came from curiosity. He believes that whether you like it or not life itself is a pilgrimage, a concept widely shared by Sufi thought and approach. "

I hope the plan to read The Arabian Nights is still on. I lost the train on the Decameron, but I hope to jump back in with the Nights.

I hope the plan to read The Arabian Nights is still on. I lost the train on the Decameron, but I hope to jump back in with the Nights.

Algernon wrote: "I hope the plan to read The Arabian Nights is still on. I lost the train on the Decameron, but I hope to jump back in with the Nights."

Wonderful Algernon! We'll look forward to having you read with us!

Wonderful Algernon! We'll look forward to having you read with us!

Sharing some articles on reading:

How to Boost Your Reading Focus in a Busy, Buzzy Age

http://publishingperspectives.com/201...

"I subscribe to the theory that reading a book is similar to walking a trail, and I’m most comfortable walking when I can see where I’m going and where I’ve been. When I’m reading a printed book, the weight of the pages I’ve turned gives me a sense of how far I’ve come. I can easily make scribbles (tracks) of my passage, and the pages I have yet to turn give me a clear sense of how far I have to go.

But when I’m reading long-form prose on a screen, I tend to feel like I’m walking through fog, with no clear guideposts for how far I’ve come or how far I’m going. I often start feel a bit lost, and I wonder if I might not be walking in circles.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/08...

How to Boost Your Reading Focus in a Busy, Buzzy Age

http://publishingperspectives.com/201...

"I subscribe to the theory that reading a book is similar to walking a trail, and I’m most comfortable walking when I can see where I’m going and where I’ve been. When I’m reading a printed book, the weight of the pages I’ve turned gives me a sense of how far I’ve come. I can easily make scribbles (tracks) of my passage, and the pages I have yet to turn give me a clear sense of how far I have to go.

But when I’m reading long-form prose on a screen, I tend to feel like I’m walking through fog, with no clear guideposts for how far I’ve come or how far I’m going. I often start feel a bit lost, and I wonder if I might not be walking in circles.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/08...

An interesting read:

Green: The History of a Color

Trained as a medievalist, Pastoureau argues that the history of color is an “altogether more vast” subject than the history of painting, and this book’s concerns range from Latin etymologies to the green neon crosses that hang outside modern French pharmacies. Still, many of his examples do come from the world of art, and I’ll use one of them to pry open the complex of questions, issues, and associations on which his work depends.

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archi...

Green: The History of a Color

Trained as a medievalist, Pastoureau argues that the history of color is an “altogether more vast” subject than the history of painting, and this book’s concerns range from Latin etymologies to the green neon crosses that hang outside modern French pharmacies. Still, many of his examples do come from the world of art, and I’ll use one of them to pry open the complex of questions, issues, and associations on which his work depends.

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archi...

Great article. I've "suggested" to my library that they get this book - still waiting to hear from them! I enjoyed Pastoureau's Black: The History of a Color and got his Blue: The History of a Color when Kalliope posted her review. :)

Great article. I've "suggested" to my library that they get this book - still waiting to hear from them! I enjoyed Pastoureau's Black: The History of a Color and got his Blue: The History of a Color when Kalliope posted her review. :)DL - Good to see you around! Did you get a look at the medieval underwear stuff this week? ^^

I am really loving the theme/design of your web site. Do you ever run into any browser compatibility problems? A few of my blog readers have complained about my website not working correctly in Explorer but looks great in Chrome. Do you have any tips to help fix this issue? panting artist

I am really loving the theme/design of your web site. Do you ever run into any browser compatibility problems? A few of my blog readers have complained about my website not working correctly in Explorer but looks great in Chrome. Do you have any tips to help fix this issue? panting artist

Books mentioned in this topic

Black: The History of a Color (other topics)Blue: The History of a Color (other topics)

Florence: A Portrait (other topics)

The Decameron (other topics)