The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Great Expectations

Great Expectations

>

GE, Chapters 25 - 26

In Chapter 26, we have Pip and his "pals" being invited to Jaggers’s house for dinner. Jaggers tells Pip they should be at the office by 6pm the next day and they will go along with him to his house. Pip now tells us that Jaggers "washed his clients off, as if he were a surgeon or a dentist". He had a room in his office just for this. It had a large towel on a roller inside the door, and ,

"he would wash his hands, and wipe them and dry them all over this towel, whenever he came in from a police court or dismissed a client from his room. When I and my friends repaired to him at six o’clock next day, he seemed to have been engaged on a case of a darker complexion than usual, for we found him with his head butted into this closet, not only washing his hands, but laving his face and gargling his throat. And even when he had done all that, and had gone all round the jack-towel, he took out his penknife and scraped the case out of his nails before he put his coat on. is oppressive and dark, shared only with a gloomy housekeeper, Molly."

Pip’s fellow students attend the dinner at Jaggers’s with Pip, along with Herbert who I cannot remember if he is a student of his father's or not. Anyway, Pip, Herbert, Drummle, and Startop meet Jaggers at his office . After all the cleaning is done they head home with him. His home is described as "a stately house of its kind, but dolefully in want of painting, and with dirty windows." That surprised me, I would have thought that Jaggers would want to keep up appearances. For reasons I can't understand he takes a liking, or an interest maybe, in Drummle, the one who speaks the least and replies to almost nothing. But Jaggers likes him, asking Pip who he is and calling him "the spider" after that. At least to Pip he does. Now something happens that I do not understand at all, so I will just quote it and let it to you to explain it to me.

"Now the housekeeper was at that time clearing the table; my guardian, taking no heed of her, but with the side of his face turned from her, was leaning back in his chair biting the side of his forefinger and showing an interest in Drummle, that, to me, was quite inexplicable. Suddenly, he clapped his large hand on the housekeeper’s, like a trap, as she stretched it across the table. So suddenly and smartly did he do this, that we all stopped in our foolish contention.

“If you talk of strength,” said Mr. Jaggers, “I’ll show you a wrist. Molly, let them see your wrist.”

Her entrapped hand was on the table, but she had already put her other hand behind her waist. “Master,” she said, in a low voice, with her eyes attentively and entreatingly fixed upon him. “Don’t.”

“I’ll show you a wrist,” repeated Mr. Jaggers, with an immovable determination to show it. “Molly, let them see your wrist.”

“Master,” she again murmured. “Please!”

“Molly,” said Mr. Jaggers, not looking at her, but obstinately looking at the opposite side of the room, “let them see both your wrists. Show them. Come!”

He took his hand from hers, and turned that wrist up on the table. She brought her other hand from behind her, and held the two out side by side. The last wrist was much disfigured,—deeply scarred and scarred across and across. When she held her hands out she took her eyes from Mr. Jaggers, and turned them watchfully on every one of the rest of us in succession.

“There’s power here,” said Mr. Jaggers, coolly tracing out the sinews with his forefinger. “Very few men have the power of wrist that this woman has. It’s remarkable what mere force of grip there is in these hands. I have had occasion to notice many hands; but I never saw stronger in that respect, man’s or woman’s, than these.”

While he said these words in a leisurely, critical style, she continued to look at every one of us in regular succession as we sat. The moment he ceased, she looked at him again. “That’ll do, Molly,” said Mr. Jaggers, giving her a slight nod; “you have been admired, and can go.” She withdrew her hands and went out of the room, and Mr. Jaggers, putting the decanters on from his dumb-waiter, filled his glass and passed round the wine."

I am assuming that Molly tried to commit suicide, although I'm not even sure of that, but why Jaggers would want to show her wrist to guests is beyond me, it is almost like he is proud of it. Since I can't think of any reason to be proud of someone else's suicide, I can't figure out why he is doing this. Perhaps one of you can explain it to me. During the dinner there was an argument between Drummle and the others about money, borrowing and lending, and only ended when Jaggers tells them it is time to go. Drummle is still so angry with them that he refuses to walk home with Startop and so they end up walking back on different sides of the street. We are told that in another month Drummle's time with Mr. Pocket was up and he returned to his home. This is what has me changing my mind about Drummle being a main character in the rest of the book. He went home while Pip is still moving on to his great expectations.

"he would wash his hands, and wipe them and dry them all over this towel, whenever he came in from a police court or dismissed a client from his room. When I and my friends repaired to him at six o’clock next day, he seemed to have been engaged on a case of a darker complexion than usual, for we found him with his head butted into this closet, not only washing his hands, but laving his face and gargling his throat. And even when he had done all that, and had gone all round the jack-towel, he took out his penknife and scraped the case out of his nails before he put his coat on. is oppressive and dark, shared only with a gloomy housekeeper, Molly."

Pip’s fellow students attend the dinner at Jaggers’s with Pip, along with Herbert who I cannot remember if he is a student of his father's or not. Anyway, Pip, Herbert, Drummle, and Startop meet Jaggers at his office . After all the cleaning is done they head home with him. His home is described as "a stately house of its kind, but dolefully in want of painting, and with dirty windows." That surprised me, I would have thought that Jaggers would want to keep up appearances. For reasons I can't understand he takes a liking, or an interest maybe, in Drummle, the one who speaks the least and replies to almost nothing. But Jaggers likes him, asking Pip who he is and calling him "the spider" after that. At least to Pip he does. Now something happens that I do not understand at all, so I will just quote it and let it to you to explain it to me.

"Now the housekeeper was at that time clearing the table; my guardian, taking no heed of her, but with the side of his face turned from her, was leaning back in his chair biting the side of his forefinger and showing an interest in Drummle, that, to me, was quite inexplicable. Suddenly, he clapped his large hand on the housekeeper’s, like a trap, as she stretched it across the table. So suddenly and smartly did he do this, that we all stopped in our foolish contention.

“If you talk of strength,” said Mr. Jaggers, “I’ll show you a wrist. Molly, let them see your wrist.”

Her entrapped hand was on the table, but she had already put her other hand behind her waist. “Master,” she said, in a low voice, with her eyes attentively and entreatingly fixed upon him. “Don’t.”

“I’ll show you a wrist,” repeated Mr. Jaggers, with an immovable determination to show it. “Molly, let them see your wrist.”

“Master,” she again murmured. “Please!”

“Molly,” said Mr. Jaggers, not looking at her, but obstinately looking at the opposite side of the room, “let them see both your wrists. Show them. Come!”

He took his hand from hers, and turned that wrist up on the table. She brought her other hand from behind her, and held the two out side by side. The last wrist was much disfigured,—deeply scarred and scarred across and across. When she held her hands out she took her eyes from Mr. Jaggers, and turned them watchfully on every one of the rest of us in succession.

“There’s power here,” said Mr. Jaggers, coolly tracing out the sinews with his forefinger. “Very few men have the power of wrist that this woman has. It’s remarkable what mere force of grip there is in these hands. I have had occasion to notice many hands; but I never saw stronger in that respect, man’s or woman’s, than these.”

While he said these words in a leisurely, critical style, she continued to look at every one of us in regular succession as we sat. The moment he ceased, she looked at him again. “That’ll do, Molly,” said Mr. Jaggers, giving her a slight nod; “you have been admired, and can go.” She withdrew her hands and went out of the room, and Mr. Jaggers, putting the decanters on from his dumb-waiter, filled his glass and passed round the wine."

I am assuming that Molly tried to commit suicide, although I'm not even sure of that, but why Jaggers would want to show her wrist to guests is beyond me, it is almost like he is proud of it. Since I can't think of any reason to be proud of someone else's suicide, I can't figure out why he is doing this. Perhaps one of you can explain it to me. During the dinner there was an argument between Drummle and the others about money, borrowing and lending, and only ended when Jaggers tells them it is time to go. Drummle is still so angry with them that he refuses to walk home with Startop and so they end up walking back on different sides of the street. We are told that in another month Drummle's time with Mr. Pocket was up and he returned to his home. This is what has me changing my mind about Drummle being a main character in the rest of the book. He went home while Pip is still moving on to his great expectations.

Kim wrote: "I had forgotten how much I like this chapter, when I began reading about Wemmicks cottage it all came back to me, I find it absolutely delightful"

Kim wrote: "I had forgotten how much I like this chapter, when I began reading about Wemmicks cottage it all came back to me, I find it absolutely delightful"Me, too, Kim! I just love the relationship between Wemmick and his father, and love that he calls him "the Aged". This is the happy home I always look for in a Dickens novel. The home itself sounds quirky - it's not designed for the approval of outsiders, but for the comfort and delight of its inhabitants. Wemmick is very proud of it, and the work he has done on it. Despite the fact that it's not a Grand House and doesn't seem like something that would be good enough for Pip, he "highly commended" it which, to me, speaks to both its warmth and Wemmick's infectious pride. Interesting how Wemmick separates his home and work lives, and that there is actually a physical manifestation of that separation.

Here are the illustrations, everyone seemed to like the "aged":

Aged P.

F. W. Pailthorpe

c. 1900

"'Well, aged parent,' said Wemmick, shaking hands with him in a cordial and jocuse way, 'How am you?'"

Text Illustrated:

“Well aged parent,” said Wemmick, shaking hands with him in a cordial and jocose way, “how am you?”

“All right, John; all right!” replied the old man.

“Here’s Mr. Pip, aged parent,” said Wemmick, “and I wish you could hear his name. Nod away at him, Mr. Pip; that’s what he likes. Nod away at him, if you please, like winking!”

“This is a fine place of my son’s, sir,” cried the old man, while I nodded as hard as I possibly could. “This is a pretty pleasure-ground, sir. This spot and these beautiful works upon it ought to be kept together by the Nation, after my son’s time, for the people’s enjoyment."

Aged P.

F. W. Pailthorpe

c. 1900

"'Well, aged parent,' said Wemmick, shaking hands with him in a cordial and jocuse way, 'How am you?'"

Text Illustrated:

“Well aged parent,” said Wemmick, shaking hands with him in a cordial and jocose way, “how am you?”

“All right, John; all right!” replied the old man.

“Here’s Mr. Pip, aged parent,” said Wemmick, “and I wish you could hear his name. Nod away at him, Mr. Pip; that’s what he likes. Nod away at him, if you please, like winking!”

“This is a fine place of my son’s, sir,” cried the old man, while I nodded as hard as I possibly could. “This is a pretty pleasure-ground, sir. This spot and these beautiful works upon it ought to be kept together by the Nation, after my son’s time, for the people’s enjoyment."

"We found the aged heating the poker, with expectant eyes"

by F. A. Fraser. c. 1877

Chapter 25

Text Illustrated:

"I am my own engineer, and my own carpenter, and my own plumber, and my own gardener, and my own Jack of all Trades,” said Wemmick, in acknowledging my compliments. “Well; it’s a good thing, you know. It brushes the Newgate cobwebs away, and pleases the Aged. You wouldn’t mind being at once introduced to the Aged, would you? It wouldn’t put you out?”

I expressed the readiness I felt, and we went into the castle. There we found, sitting by a fire, a very old man in a flannel coat: clean, cheerful, comfortable, and well cared for, but intensely deaf.

“Well aged parent,” said Wemmick, shaking hands with him in a cordial and jocose way, “how am you?”

“All right, John; all right!” replied the old man.

“Here’s Mr. Pip, aged parent,” said Wemmick, “and I wish you could hear his name. Nod away at him, Mr. Pip; that’s what he likes. Nod away at him, if you please, like winking!”

“This is a fine place of my son’s, sir,” cried the old man, while I nodded as hard as I possibly could. “This is a pretty pleasure-ground, sir. This spot and these beautiful works upon it ought to be kept together by the Nation, after my son’s time, for the people’s enjoyment."

"Pip Shares The Treat Of Mr. Wemmick, Senior"

Chapter 25

Harry Furniss

1910

"Mr. John Wemmick took the red-hot poker, and presently the gun went off with a bang that shook the cottage. Upon this the Aged cried out exultingly, "He's fired! I heered him!"

Text Illustrated:

"Of course I felt my good faith involved in the observance of his request. The punch being very nice, we sat there drinking it and talking, until it was almost nine o’clock. “Getting near gun-fire,” said Wemmick then, as he laid down his pipe; “it’s the Aged’s treat.”

Proceeding into the Castle again, we found the Aged heating the poker, with expectant eyes, as a preliminary to the performance of this great nightly ceremony. Wemmick stood with his watch in his hand until the moment was come for him to take the red-hot poker from the Aged, and repair to the battery. He took it, and went out, and presently the Stinger went off with a Bang that shook the crazy little box of a cottage as if it must fall to pieces, and made every glass and teacup in it ring. Upon this, the Aged—who I believe would have been blown out of his arm-chair but for holding on by the elbows—cried out exultingly, “He’s fired! I heerd him!” and I nodded at the old gentleman until it is no figure of speech to declare that I absolutely could not see him."

"Well, aged parent.' said Wemmick, 'how am you?'"

Chapter 25

H. M. Brock

1903

Text Illustrated:

“I am my own engineer, and my own carpenter, and my own plumber, and my own gardener, and my own Jack of all Trades,” said Wemmick, in acknowledging my compliments. “Well; it’s a good thing, you know. It brushes the Newgate cobwebs away, and pleases the Aged. You wouldn’t mind being at once introduced to the Aged, would you? It wouldn’t put you out?”

I expressed the readiness I felt, and we went into the castle. There we found, sitting by a fire, a very old man in a flannel coat: clean, cheerful, comfortable, and well cared for, but intensely deaf.

“Well aged parent,” said Wemmick, shaking hands with him in a cordial and jocose way, “how am you?”

“All right, John; all right!” replied the old man.

“Here’s Mr. Pip, aged parent,” said Wemmick, “and I wish you could hear his name. Nod away at him, Mr. Pip; that’s what he likes. Nod away at him, if you please, like winking!”

“This is a fine place of my son’s, sir,” cried the old man, while I nodded as hard as I possibly could. “This is a pretty pleasure-ground, sir. This spot and these beautiful works upon it ought to be kept together by the Nation, after my son’s time, for the people’s enjoyment.”

“You’re as proud of it as Punch; ain’t you, Aged?” said Wemmick, contemplating the old man, with his hard face really softened; “there’s a nod for you;” giving him a tremendous one; “there’s another for you;” giving him a still more tremendous one; “you like that, don’t you? If you’re not tired, Mr. Pip—though I know it’s tiring to strangers—will you tip him one more? You can’t think how it pleases him.”

Wemmick and "The Aged"

Sol Eytinge

1867

Commentary:

"In "Wemmick and "The Aged," Eytinge contrasts the private, sentimental "Walworth" existence of Jaggers's clerk John Wemmick, Jr., with the sordid business of the law offices in Little Britain, represented by the previous illustration, "Jaggers". Despite the years of labour that John Wemmick has lavished on his castle and his devoted care of his "Aged Parent," John Wemmick, Sr., he has never invited his secretive employer, the attorney Jaggers down to Walworth. A self-centred young aristocrat such as Bentley Drummle would not have been prepared to humour Wemmick and his deaf father as Pip does — but then Wemiick would not have invited any of the others from among the privileged ranks of "The Finches of the Grove" in the first place.

In the 1877 Household Edition, illustrator F. A. Fraser includes a scene in which John Wemmick, Sr., is heating a poker in preparation for setting off "The Stinger," a small cannon which Wemmick sets off with his father's help daily so that the old fellow can continue to hear some sound and make some tenuous connection with the outside world, in a scene entitled "We found the aged heating the poker, with expectant eyes":

.........."Proceeding into the Castle again, we found the Aged heating the poker, with expectant eyes, as a preliminary to the performance of this great nightly ceremony. Wemmick stood with his watch in his hand, until the moment was come for him to take the red-hot poker from the Aged, and repair to the battery. He took it, and went out, and presently the Stinger went off with a Bang that shook the crazy little box of a cottage as if it must fall to pieces, and made every glass and teacup in it ring. Upon this, the Aged — who I believe would have been blown out of his arm-chair but for holding on by the elbows — cried out exultingly, 'He's fired! I heerd him!' and I nodded at the old gentleman until it is no figure of speech to declare that I absolutely could not see him."

The fact that in Ch. 25 Dickens specifies a heated poker, depicted here, and that Eytinge has given the Aged P. a toasting fork would suggest that the above moment is not the scene that Eytinge has chosen to depict. Despite the marvellous detail involved in the parlour setting in the Household Edition's woodcut, Fraser does convey as effectively as Eytinge either the genial relationship of father and son or the old man's delight in his "castle." Eytinge may have only a teapot and a cloth-covered table as properties; however, he creates a surer dual portrait of John Wemmick, Sr., cheerful and well-dressed, despite his advanced age and hearing impairment, and John Wemmick, Jr., happy to indulge his Walworth sentiments to the full.

John McLenan's thirtieth illustration in the Harper's Weekly series of 1860-61 contains, however, an illustration of what is apparently the same moment that engaged Eytinge five years later, "The responsible duty of making the toast was delegated to the Aged" (27 April 1861). McLenan's slightly larger plate — again does a proficient job of delineating the setting, giving us, like Fraser's, all the paraphernalia of the parlour (indeed, his fireplace and hearth are rather more credible than Fraser's), but he gives us little sense of the character of the Aged P., in leggings and the skull-cap traditionally worn by aged men in the early nineteenth century.

........"After a little further conversation to the same effect, we returned into the Castle where we found Miss Skiffins preparing tea. The responsible duty of making the toast was delegated to the Aged, and that excellent old gentleman was so intent upon it that he seemed to me in some danger of melting his eyes. It was no nominal meal that we were going to make, but a vigorous reality. The Aged prepared such a haystack of buttered toast, that I could scarcely see him over it as it simmered on an iron stand hooked on to the top-bar; while Miss Skiffins brewed such a jorum of tea, that the pig in the back premises became strongly excited, and repeatedly expressed his desire to participate in the entertainment."

John McLenan

1861

I'm just about positive that this illustration is with a different, later chapter, but since it is mentioned in the commentary for the Eytinge illustration I'm putting it here, I will again post it where it belongs, if I remember that is.

"Molly Shows Her Wrists"

Harry Furniss

1910

Chapter 26

"Molly brought her other hand from behind her, and held the two out side by side. As she did so, she took her eyes from Mr. Jaggers, and turned them watchfully on every one of the rest of us in succession."

Text Illustrated:

"Now the housekeeper was at that time clearing the table; my guardian, taking no heed of her, but with the side of his face turned from her, was leaning back in his chair biting the side of his forefinger and showing an interest in Drummle, that, to me, was quite inexplicable. Suddenly, he clapped his large hand on the housekeeper’s, like a trap, as she stretched it across the table. So suddenly and smartly did he do this, that we all stopped in our foolish contention.

“If you talk of strength,” said Mr. Jaggers, “I’ll show you a wrist. Molly, let them see your wrist.”

Her entrapped hand was on the table, but she had already put her other hand behind her waist. “Master,” she said, in a low voice, with her eyes attentively and entreatingly fixed upon him. “Don’t.”

“I’ll show you a wrist,” repeated Mr. Jaggers, with an immovable determination to show it. “Molly, let them see your wrist.”

“Master,” she again murmured. “Please!”

“Molly,” said Mr. Jaggers, not looking at her, but obstinately looking at the opposite side of the room, “let them see both your wrists. Show them. Come!”

He took his hand from hers, and turned that wrist up on the table. She brought her other hand from behind her, and held the two out side by side. The last wrist was much disfigured,—deeply scarred and scarred across and across. When she held her hands out she took her eyes from Mr. Jaggers, and turned them watchfully on every one of the rest of us in succession.

“There’s power here,” said Mr. Jaggers, coolly tracing out the sinews with his forefinger. “Very few men have the power of wrist that this woman has. It’s remarkable what mere force of grip there is in these hands. I have had occasion to notice many hands; but I never saw stronger in that respect, man’s or woman’s, than these.”

Molly's wrists don't look particularly brawny in either of the two illustrations. In fact, they look rather dainty.

Molly's wrists don't look particularly brawny in either of the two illustrations. In fact, they look rather dainty. Eytinge, Brock, and Pailthorpe capture the warmth of the Wemmick household well. The Aged looks a bit isolated in the McLenan and Fraser illustrations. I don't care for the Furniss picture at all -- it's not the scene I would choose to depict, nor is the Aged portrayed the way I see him.

I think the Brock picture is my favorite -- it captures all three men most closely to how I imagine them. But notice that Pailthorpe has included a bird on the mantle in his picture, which I know will appeal to some of you!

Kim. So many pictures. Thank you. Where would you go to have diner?

These two chapters give us a very clear way to differentiate the characters of Jaggers and Mr Wemmick. Wemmick's home is, well, unique. I have no idea how a real estate agent would list it. Wemmick's house does, however, explain the man. He chooses to lead two different lives. For all Wemmick's fascination about the law courts, the death masks, and Jaggers abilities to terrify clients, Wemmick is a man who loves both his home and his Aged Parent. Wemmick is self-reliant, whether it be his suggestion to Pip to highly value portable property or his domestic desire to create a home that is safe, secure, and self-sustaining. Wemmick is a man you could trust, a person who could be your friend. It would be easy to keep his home life very separate and very secret from Jaggers. Not that Jaggers would probably care in any case.

In Jaggers home we find a somewhat formal setting, and if the atmosphere is not totally repressive, it is certainly somewhat confrontational. Jaggers seems to enjoy gritty conversation, he seems to relish his power over maid and there must be a reason why he is so insistent that Pip and his schoolmates pay close attention to Molly's wrists. Since we were not told the full story of Molly and her wrists, it suggests that there will be more to come of her backstory later in the novel. The interplay among Jaggers and his dinner guests is also interesting. Why does Jaggers find Drummle so interesting? Further, when Drummle gets sulky it is a brooding sulkiness. Not a likeable person. Drummle and Molly were the two mysteries who came or served the dinner at Jaggers. There must be more to this than a simple meal.

All in all, I'd be happy to dine with Wemmick and his father.

Should Jaggers invite me I would be on edge, and who wants not to enjoy a meal?

These two chapters give us a very clear way to differentiate the characters of Jaggers and Mr Wemmick. Wemmick's home is, well, unique. I have no idea how a real estate agent would list it. Wemmick's house does, however, explain the man. He chooses to lead two different lives. For all Wemmick's fascination about the law courts, the death masks, and Jaggers abilities to terrify clients, Wemmick is a man who loves both his home and his Aged Parent. Wemmick is self-reliant, whether it be his suggestion to Pip to highly value portable property or his domestic desire to create a home that is safe, secure, and self-sustaining. Wemmick is a man you could trust, a person who could be your friend. It would be easy to keep his home life very separate and very secret from Jaggers. Not that Jaggers would probably care in any case.

In Jaggers home we find a somewhat formal setting, and if the atmosphere is not totally repressive, it is certainly somewhat confrontational. Jaggers seems to enjoy gritty conversation, he seems to relish his power over maid and there must be a reason why he is so insistent that Pip and his schoolmates pay close attention to Molly's wrists. Since we were not told the full story of Molly and her wrists, it suggests that there will be more to come of her backstory later in the novel. The interplay among Jaggers and his dinner guests is also interesting. Why does Jaggers find Drummle so interesting? Further, when Drummle gets sulky it is a brooding sulkiness. Not a likeable person. Drummle and Molly were the two mysteries who came or served the dinner at Jaggers. There must be more to this than a simple meal.

All in all, I'd be happy to dine with Wemmick and his father.

Should Jaggers invite me I would be on edge, and who wants not to enjoy a meal?

Mary Lou wrote: "Molly's wrists don't look particularly brawny in either of the two illustrations. In fact, they look rather dainty.

Eytinge, Brock, and Pailthorpe capture the warmth of the Wemmick household well..."

Thanks for pointing out the bird on the mantle. Did you notice in the F. A. Fraser illustration of the bird cage and bird over The the Aged's chair?

I have made note of these two in a journal I'm keeping. I've never owned a bird so why I am so intrigued with all the references to birds and illustrations of birds and birdcages - with the exception of Miss Flite in BH - must remain a mystery to me until some great revelation hits me on the head one day. I have a couple of far-fetched ideas but am too embarrassed to admit them, even to myself. :- )

Eytinge, Brock, and Pailthorpe capture the warmth of the Wemmick household well..."

Thanks for pointing out the bird on the mantle. Did you notice in the F. A. Fraser illustration of the bird cage and bird over The the Aged's chair?

I have made note of these two in a journal I'm keeping. I've never owned a bird so why I am so intrigued with all the references to birds and illustrations of birds and birdcages - with the exception of Miss Flite in BH - must remain a mystery to me until some great revelation hits me on the head one day. I have a couple of far-fetched ideas but am too embarrassed to admit them, even to myself. :- )

Peter wrote: "Did you notice in the F. A. Fraser illustration the bird cage and bird over The the Aged's chair?"

Peter wrote: "Did you notice in the F. A. Fraser illustration the bird cage and bird over The the Aged's chair?"No! And I was trying to pay particular attention to the surroundings. Amazing what the mind can miss, even when something is right there in front of you.

These days, it's quite hard for me to catch up because when I'm not at work, I'm actually in bed, trying to get my temperature down and my stomach back in working order. Dickens, however, always puts me right again.

When I read those last two chapters, I had the same idea as Peter - two different homes, two different dinner parties - which one would I prefer to be a guest at? My answer was not hard to think out, though ...

On the one hand, there is Wemmick, who has got a very cosy home, with a little drawbridge even, whose symbolical meaning is not difficult to guess, and who is living with his aged father, to whom he is a most dutiful and caring son. The rooms may be small, and the dinner might not be perfect in every way, but it is not simply a house, but a home that Pip is visiting. It must also mean something that Wemmick invited - he did, didn't he? - Pip to one day come and pay him a visit in his own house, considering that he makes a secret about his private life in the office because he knows that no one there would understand him. So in a way, inviting Pip over is a sign of confidence.

On the other hand, there is Jaggers's house, in which he only uses a couple of rooms, and which does not shelter any person he really cares for but a woman over whom he apparently exercises some kind of power and who may therefore not be too kindly disposed towards him. Nevertheless, Jaggers seems to be enjoying this kind of relationship. Unlike Wemmick, Jaggers takes a lot of his work home with himself, and although the food and the wines are of choice quality, the whole dinner is dominated by Jaggers's way of dealing with his guests, of asking them sly questions and of bullying the housekeeper.

I was also astonished to learn of Jaggers's mannerism of washing his hands of every client he has before he turns his attention to another one - this would explain why his hands smell so much of soap. And it would make him some kind of modern Pontius Pilate, showing the cynicism with which he goes about his job.

When I read those last two chapters, I had the same idea as Peter - two different homes, two different dinner parties - which one would I prefer to be a guest at? My answer was not hard to think out, though ...

On the one hand, there is Wemmick, who has got a very cosy home, with a little drawbridge even, whose symbolical meaning is not difficult to guess, and who is living with his aged father, to whom he is a most dutiful and caring son. The rooms may be small, and the dinner might not be perfect in every way, but it is not simply a house, but a home that Pip is visiting. It must also mean something that Wemmick invited - he did, didn't he? - Pip to one day come and pay him a visit in his own house, considering that he makes a secret about his private life in the office because he knows that no one there would understand him. So in a way, inviting Pip over is a sign of confidence.

On the other hand, there is Jaggers's house, in which he only uses a couple of rooms, and which does not shelter any person he really cares for but a woman over whom he apparently exercises some kind of power and who may therefore not be too kindly disposed towards him. Nevertheless, Jaggers seems to be enjoying this kind of relationship. Unlike Wemmick, Jaggers takes a lot of his work home with himself, and although the food and the wines are of choice quality, the whole dinner is dominated by Jaggers's way of dealing with his guests, of asking them sly questions and of bullying the housekeeper.

I was also astonished to learn of Jaggers's mannerism of washing his hands of every client he has before he turns his attention to another one - this would explain why his hands smell so much of soap. And it would make him some kind of modern Pontius Pilate, showing the cynicism with which he goes about his job.

You're sick again? What about all those students and soon to be teachers who are looking for you? How will they ever pass those exams you have such fun reading?

Actually, I go to work in the first part of the day and try to recover when at home. I know that's not the cleverest thing to do but then I'm usually not the cleverest person around :-)

Kim wrote: "True. :-) What's wrong anyway?"

Ah, you know that sort of thing: The children bring germs home from school or kindergarten, and then it's a kind of Russian roulette whether the parents, too, will come down with a temperature and an upset stomach, or lycanthropy, or not.

Ah, you know that sort of thing: The children bring germs home from school or kindergarten, and then it's a kind of Russian roulette whether the parents, too, will come down with a temperature and an upset stomach, or lycanthropy, or not.

Teach them at home and that wouldn't happen. You could teach them all those long words only you know. I have to go now and look up the word lycanthropy. :-)

lycanthropy:

the supernatural transformation of a person into a wolf, as recounted in folk tales.

•archaic

a form of madness involving the delusion of being an animal, usually a wolf, with correspondingly altered behavior.

Clinical lycanthropy is defined as a rare psychiatric syndrome that involves a delusion that the affected person can transform into, has transformed into, or is a non-human animal. Its name is connected to the mythical condition of lycanthropy, a supernatural affliction in which humans are said to physically shapeshift into wolves. It is purported to be a rare disorder.

It is purported to be a rare disorder?

No kidding.

:-)

the supernatural transformation of a person into a wolf, as recounted in folk tales.

•archaic

a form of madness involving the delusion of being an animal, usually a wolf, with correspondingly altered behavior.

Clinical lycanthropy is defined as a rare psychiatric syndrome that involves a delusion that the affected person can transform into, has transformed into, or is a non-human animal. Its name is connected to the mythical condition of lycanthropy, a supernatural affliction in which humans are said to physically shapeshift into wolves. It is purported to be a rare disorder.

It is purported to be a rare disorder?

No kidding.

:-)

Kim wrote: "lycanthropy:

the supernatural transformation of a person into a wolf, as recounted in folk tales.

•archaic

a form of madness involving the delusion of being an animal, usually a wolf, with corres..."

When we were sick at school, we always had to hand in a form a few days later giving the reason for our absence, and once I wrote lycanthropy just in order to check whether my teacher would even read the form. He apparently didn't because my absence was excused. Speaking of which, these forms still exist today, and one of my students once wrote "lovesickness" into the field where it says, reason for absence. I always read those forms because from time to time, they inspire students to feats of creative writing.

the supernatural transformation of a person into a wolf, as recounted in folk tales.

•archaic

a form of madness involving the delusion of being an animal, usually a wolf, with corres..."

When we were sick at school, we always had to hand in a form a few days later giving the reason for our absence, and once I wrote lycanthropy just in order to check whether my teacher would even read the form. He apparently didn't because my absence was excused. Speaking of which, these forms still exist today, and one of my students once wrote "lovesickness" into the field where it says, reason for absence. I always read those forms because from time to time, they inspire students to feats of creative writing.

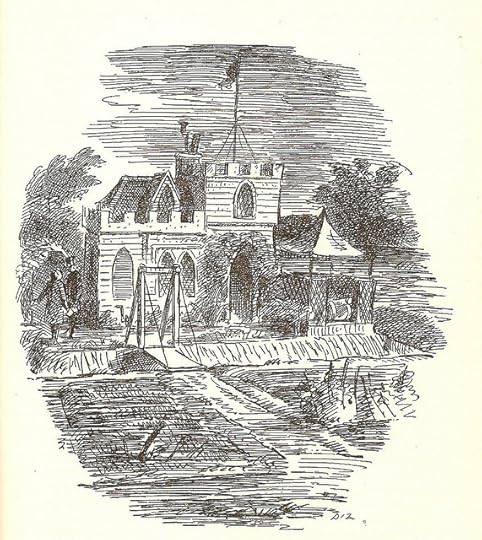

Kim wrote: "Here is an illustration of Wemmick's "castle" Edward Ardizzone in 1952.

"

That is exactly how I pictured Wemmick's little castle: a miniature replica of an old fortress, full of detail and love ;-)

"

That is exactly how I pictured Wemmick's little castle: a miniature replica of an old fortress, full of detail and love ;-)

Tristram wrote: "Speaking of which, these forms still exist today, and one of my students once wrote "lovesickness" into the field where it says, reason for absence."

Did you excuse your student for lovesickness? After your lycanthropy you should accepted just about anything. I wonder if there's a word for turning into a zombie?

Did you excuse your student for lovesickness? After your lycanthropy you should accepted just about anything. I wonder if there's a word for turning into a zombie?

Kim wrote: "lycanthropy:

the supernatural transformation of a person into a wolf, as recounted in folk tales.

•archaic

a form of madness involving the delusion of being an animal, usually a wolf, with corres..."

What does a Dickensian howl sound like anyway?

the supernatural transformation of a person into a wolf, as recounted in folk tales.

•archaic

a form of madness involving the delusion of being an animal, usually a wolf, with corres..."

What does a Dickensian howl sound like anyway?

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Speaking of which, these forms still exist today, and one of my students once wrote "lovesickness" into the field where it says, reason for absence."

Did you excuse your student f..."

I actually did excuse my student for lovesickness, telling him that it is an ailment typical of young people, who still lack the necessary imagination to figure out what the beloved person will be a score of years from hence.

As to zombification, I have noticed that it happened to some of my colleagues after a ring was put on their finger.

Did you excuse your student f..."

I actually did excuse my student for lovesickness, telling him that it is an ailment typical of young people, who still lack the necessary imagination to figure out what the beloved person will be a score of years from hence.

As to zombification, I have noticed that it happened to some of my colleagues after a ring was put on their finger.

Peter wrote: "What does a Dickensian howl sound like anyway? "

Peter, was that not a typo? You are so interested in Dickensian birds that it should have been "owl", shouldn't it? ;-)

Peter, was that not a typo? You are so interested in Dickensian birds that it should have been "owl", shouldn't it? ;-)

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "What does a Dickensian howl sound like anyway? "

Peter, was that not a typo? You are so interested in Dickensian birds that it should have been "owl", shouldn't it? ;-)"

Touché. My first laugh of the day. :-)

Peter, was that not a typo? You are so interested in Dickensian birds that it should have been "owl", shouldn't it? ;-)"

Touché. My first laugh of the day. :-)

I hope your day will give you lots of more opportunities to laugh, Peter - and knowing you from our past Dickens adventures, I'm quite sure it will.

Kim wrote: "I had forgotten how much I like this chapter, when I began reading about Wemmicks cottage it all came back to me, I find it absolutely delightful:."

I have always enjoyed the visit to Wemmick's, and re-reading it was a great pleasure.

I have always enjoyed the visit to Wemmick's, and re-reading it was a great pleasure.

Kim wrote: "For now though he writes a note to Wemmick proposing he go home with him, another thing I found strange. As far as I remember I never called someone up and say "hey can I come to your house?" but I've always waited for the person call me. ."

Did you recall that back in Chapter 24 Wemmick had said

“If at any odd time when you have nothing better to do, you wouldn’t mind coming over to see me at Walworth, I could offer you a bed, and I should consider it an honor. I have not much to show you; but such two or three curiosities as I have got you might like to look over; and I am fond of a bit of garden and a summer-house.”

I said I should be delighted to accept his hospitality.

“Thankee,” said he; “then we’ll consider that it’s to come off, when convenient to you."

I think Pip considered that the invitation, and he was saying it was now convenient to him.

BTW, Walworth is now, of course, part of London, but then it was quite apart, on the south side of the Thames roughly a mile from the City proper.

Did you recall that back in Chapter 24 Wemmick had said

“If at any odd time when you have nothing better to do, you wouldn’t mind coming over to see me at Walworth, I could offer you a bed, and I should consider it an honor. I have not much to show you; but such two or three curiosities as I have got you might like to look over; and I am fond of a bit of garden and a summer-house.”

I said I should be delighted to accept his hospitality.

“Thankee,” said he; “then we’ll consider that it’s to come off, when convenient to you."

I think Pip considered that the invitation, and he was saying it was now convenient to him.

BTW, Walworth is now, of course, part of London, but then it was quite apart, on the south side of the Thames roughly a mile from the City proper.

Mary Lou wrote: "I just love the relationship between Wemmick and his father, and love that he calls him "the Aged"."

In Arthur Ransome's Coot Club and The Big Six, the Farland twins, Port and Starboard (Bess is the left handed twin and Nell the right handed twin but since they're excellent sailors they're called Port and Starboard throughout) call their widowed father A.P. for Aged Parent.

In Arthur Ransome's Coot Club and The Big Six, the Farland twins, Port and Starboard (Bess is the left handed twin and Nell the right handed twin but since they're excellent sailors they're called Port and Starboard throughout) call their widowed father A.P. for Aged Parent.

Kim wrote: ""Well, aged parent.' said Wemmick, 'how am you?'"

Chapter 25

H. M. Brock

I like the Brock illustration the best -- it's the one one that gives me an Aged I can believe in.

Chapter 25

H. M. Brock

I like the Brock illustration the best -- it's the one one that gives me an Aged I can believe in.

Tristram wrote: "Kim wrote: "Here is an illustration of Wemmick's "castle" Edward Ardizzone in 1952.

"

That is exactly how I pictured Wemmick's little castle: a miniature replica of an old fortress, full of deta..."

Except that it doesn't have the bell ringer to summon Wemmick to drop the drawbridge.

"

That is exactly how I pictured Wemmick's little castle: a miniature replica of an old fortress, full of deta..."

Except that it doesn't have the bell ringer to summon Wemmick to drop the drawbridge.

Why did Jaggers make Molly show her wrist? It seems a strange thing to do. I can't figure out what the purpose was.

Everyman wrote: "Why did Jaggers make Molly show her wrist? It seems a strange thing to do. I can't figure out what the purpose was."

Although I've read the novel twice already, I cannot recall any particulars about Molly, not even dim recollections. I think that the wrists are supposed to indicate the strength of hands, though, and so maybe Molly - we learn from Wemmick that she was a fierce woman and that Jaggers enjoys keeping her under his thumb - might have used her hands to some violent purpose.

Although I've read the novel twice already, I cannot recall any particulars about Molly, not even dim recollections. I think that the wrists are supposed to indicate the strength of hands, though, and so maybe Molly - we learn from Wemmick that she was a fierce woman and that Jaggers enjoys keeping her under his thumb - might have used her hands to some violent purpose.

Tristram, "some kind of modern Pontius Pilate, showing the cynicism with which he goes about his job" Perfect! I'm surprised how often Dickens is using this image of handwashing.

Tristram, "some kind of modern Pontius Pilate, showing the cynicism with which he goes about his job" Perfect! I'm surprised how often Dickens is using this image of handwashing.The chapters about Wemmick's home and the "Aged P" make me smile, as does this thread. Thanks all :) I too really like that Edward Ardizzone illustration. And it occurs to me to marvel at how Dickens can make us find that scene so hugely enjoyable, without feeling that he and we are patronising the Aged P. Another author might not have been able to write this without making us wince a bit.

I think we do find out the reason for the marks on Molly's wrists later, yes, if I remember rightly. But I don't like any of those illustrations for Molly. She doesn't look like that in my mind! Oh - thanks for hunting them all down though Kim, as always :)

Jean wrote: "Tristram, "some kind of modern Pontius Pilate, showing the cynicism with which he goes about his job" Perfect! I'm surprised how often Dickens is using this image of handwashing.

The chapters abou..."

You're welcome Jean, I didn't remember that we find out why Molly's wrists look the way we do, I'll be glad to at last have that answered. Again. :-)

The chapters abou..."

You're welcome Jean, I didn't remember that we find out why Molly's wrists look the way we do, I'll be glad to at last have that answered. Again. :-)

Hello all

We will most definitely find out about Molly's wrists and Molly but patience will be first required but then richly rewarded in true Dickensian style.

:-))

We will most definitely find out about Molly's wrists and Molly but patience will be first required but then richly rewarded in true Dickensian style.

:-))

I can't remember but am sure that we'll find out about Molly. Dickens is not the author to leave us with loose ends in our hands; just remember how nicely he tied up every character's future life in his earliest books. I actually loved those final chapters in which he had something to say about every single character that had made it to the end. A pity they don't do it any more.

Thanks for confirming that, Peter! The trouble is that, just as with mysteries, I sometimes remember what I thought should have happened rather than what actually did! But this detail was very specific. Right, back now in the mindset of "not knowing" :)

Thanks for confirming that, Peter! The trouble is that, just as with mysteries, I sometimes remember what I thought should have happened rather than what actually did! But this detail was very specific. Right, back now in the mindset of "not knowing" :)Tristram, I think an author needs to be very skilled indeed to leave a satisfying ambiguity at the end. I too enjoy Dickens's tendency to "tie up the loose ends". Sadly I feel with the "intriguing" open endings of modern novels or unexplained events, mostly it's lazy writing. There are some exceptions though.

Jean wrote: "Sadly I feel with the "intriguing" open endings of modern novels or unexplained events, mostly it's lazy writing. "

It's either lazy writing, or the closest the respective author can get towards clever ambiguity.

It's either lazy writing, or the closest the respective author can get towards clever ambiguity.

Kim wrote: "Another reason not to read modern novels."

My colleagues already pull my leg for not or hardly reading modern novels - but I keep telling them that reading should be fun and not like work.

My colleagues already pull my leg for not or hardly reading modern novels - but I keep telling them that reading should be fun and not like work.

It's odd isn't it? I read a story for tinies yesterday, and was so confused by it that I yearned for Dickens. Chris thought that was hilarious! And I'm sure you've also found that people who don't read classics just don't realise how very funny a lot of them are!

It's odd isn't it? I read a story for tinies yesterday, and was so confused by it that I yearned for Dickens. Chris thought that was hilarious! And I'm sure you've also found that people who don't read classics just don't realise how very funny a lot of them are!

Some things I don't like about modern literature, or modern books:

a) pretentiousness: More often than not, modern literature is more concerned about how to tell a story than about telling a story. However, this concern actually leads to unreadable prose, such as ramblingstream-of-consciousness-passages (I would rather call this device stream-of-unconsciousness because that is the effect on the reader), excessive experiments with point of view, tautness of style leading to arid atmosphere, and above all a lack of humour;

b) goriness / explicitness: When it is not really highbrow literature, then we very often have a story that is full of gory details that are rendered very explicitly to shock and impress the reader;

c) poor grammar: Lowbrow literature of our day and age is quite often full of language mistakes, and one could say that the first and most gruesomely treated victim of many a modern thriller is always the language.

I'm sure there are still other reasons one could find for preferring classic literature to modern books, but I just wrote down the first things that came to my mind ...

a) pretentiousness: More often than not, modern literature is more concerned about how to tell a story than about telling a story. However, this concern actually leads to unreadable prose, such as ramblingstream-of-consciousness-passages (I would rather call this device stream-of-unconsciousness because that is the effect on the reader), excessive experiments with point of view, tautness of style leading to arid atmosphere, and above all a lack of humour;

b) goriness / explicitness: When it is not really highbrow literature, then we very often have a story that is full of gory details that are rendered very explicitly to shock and impress the reader;

c) poor grammar: Lowbrow literature of our day and age is quite often full of language mistakes, and one could say that the first and most gruesomely treated victim of many a modern thriller is always the language.

I'm sure there are still other reasons one could find for preferring classic literature to modern books, but I just wrote down the first things that came to my mind ...

a) just your mentioning stream of consciousness has me running away from the modern novels.

b) of course there is goriness, think of all the zombie "literature" out there.

c) Of the one or two modern novels I occasionally look at in book stores two of the reasons I put them back is that the language seems to be so "easy" that it's boring. The second is that this same language is so filled with words I wouldn't say and don't want to read, even if the novel did interest me I'd put it back anyway.

b) of course there is goriness, think of all the zombie "literature" out there.

c) Of the one or two modern novels I occasionally look at in book stores two of the reasons I put them back is that the language seems to be so "easy" that it's boring. The second is that this same language is so filled with words I wouldn't say and don't want to read, even if the novel did interest me I'd put it back anyway.

This installment includes Chapters 25 and 26, and one thing I can say about both chapters is that there is a lot of eating in them. But first things first and we begin with descriptions of Pip's fellow classmates at Pockets:

"Bentley Drummle, who was so sulky a fellow that he even took up a book as if its writer had done him an injury, did not take up an acquaintance in a more agreeable spirit. Heavy in figure, movement, and comprehension,—in the sluggish complexion of his face, and in the large, awkward tongue that seemed to loll about in his mouth as he himself lolled about in a room,—he was idle, proud, niggardly, reserved, and suspicious. He came of rich people down in Somersetshire, who had nursed this combination of qualities until they made the discovery that it was just of age and a blockhead. Thus, Bentley Drummle had come to Mr. Pocket when he was a head taller than that gentleman, and half a dozen heads thicker than most gentlemen.

Startop had been spoilt by a weak mother and kept at home when he ought to have been at school, but he was devotedly attached to her, and admired her beyond measure. He had a woman’s delicacy of feature, and was—“as you may see, though you never saw her,” said Herbert to me—“exactly like his mother.” It was but natural that I should take to him much more kindly than to Drummle, and that, even in the earliest evenings of our boating, he and I should pull homeward abreast of one another, conversing from boat to boat, while Bentley Drummle came up in our wake alone, under the overhanging banks and among the rushes. He would always creep in-shore like some uncomfortable amphibious creature, even when the tide would have sent him fast upon his way; and I always think of him as coming after us in the dark or by the back-water, when our own two boats were breaking the sunset or the moonlight in mid-stream."

Since Dickens gave us more detail into both students than we had before, especially Drummle, I have a feeling they may be around for awhile. At least that's what I thought until the end of Chapter 26. Before we get there though we have the family of Mr. Pocket showing up at the door of the Pockets:

"When I had been in Mr. Pocket’s family a month or two, Mr. and Mrs. Camilla turned up. Camilla was Mr. Pocket’s sister. Georgiana, whom I had seen at Miss Havisham’s on the same occasion, also turned up. She was a cousin,—an indigestive single woman, who called her rigidity religion, and her liver love. These people hated me with the hatred of cupidity and disappointment. As a matter of course, they fawned upon me in my prosperity with the basest meanness. Towards Mr. Pocket, as a grown-up infant with no notion of his own interests, they showed the complacent forbearance I had heard them express. Mrs. Pocket they held in contempt; but they allowed the poor soul to have been heavily disappointed in life, because that shed a feeble reflected light upon themselves."

My questions is, why are these people coming to the Pockets for a visit when they hate and look down on them in the first place? I really hope any people who hate me with the hatred of whatever they hate me of, hold me in contempt and think I am a grown-up infant, don't show up for a visit. Especially one that lasts more than an hour or so. So, why are they there? Does anyone know?

And is this a hint of what's coming ? Pip tells us:

"I soon contracted expensive habits, and began to spend an amount of money that within a few short months I should have thought almost fabulous..."

Perhaps not, perhaps he will continue on and become a gentleman or whatever his great expectation is, but he has put the thought of spending more money than his guardian has to give him in my mind. For now though he writes a note to Wemmick proposing he go home with him, another thing I found strange. As far as I remember I never called someone up and say "hey can I come to your house?" but I've always waited for the person call me. Anyway, Wemmick is pleased and we find Pip coming home with him that evening. I had forgotten how much I like this chapter, when I began reading about Wemmicks cottage it all came back to me, I find it absolutely delightful:

"At first with such discourse, and afterwards with conversation of a more general nature, did Mr. Wemmick and I beguile the time and the road, until he gave me to understand that we had arrived in the district of Walworth.

It appeared to be a collection of back lanes, ditches, and little gardens, and to present the aspect of a rather dull retirement. Wemmick’s house was a little wooden cottage in the midst of plots of garden, and the top of it was cut out and painted like a battery mounted with guns.

“My own doing,” said Wemmick. “Looks pretty; don’t it?”

I highly commended it, I think it was the smallest house I ever saw; with the queerest gothic windows (by far the greater part of them sham), and a gothic door almost too small to get in at.

“That’s a real flagstaff, you see,” said Wemmick, “and on Sundays I run up a real flag. Then look here. After I have crossed this bridge, I hoist it up—so—and cut off the communication.”

The bridge was a plank, and it crossed a chasm about four feet wide and two deep. But it was very pleasant to see the pride with which he hoisted it up and made it fast; smiling as he did so, with a relish and not merely mechanically.

“At nine o’clock every night, Greenwich time,” said Wemmick, “the gun fires. There he is, you see! And when you hear him go, I think you’ll say he’s a Stinger.”

The piece of ordnance referred to, was mounted in a separate fortress, constructed of lattice-work. It was protected from the weather by an ingenious little tarpaulin contrivance in the nature of an umbrella.

“Then, at the back,” said Wemmick, “out of sight, so as not to impede the idea of fortifications,—for it’s a principle with me, if you have an idea, carry it out and keep it up,—I don’t know whether that’s your opinion—”

I said, decidedly.

“—At the back, there’s a pig, and there are fowls and rabbits; then, I knock together my own little frame, you see, and grow cucumbers; and you’ll judge at supper what sort of a salad I can raise. So, sir,” said Wemmick, smiling again, but seriously too, as he shook his head, “if you can suppose the little place besieged, it would hold out a devil of a time in point of provisions.”

Then, he conducted me to a bower about a dozen yards off, but which was approached by such ingenious twists of path that it took quite a long time to get at; and in this retreat our glasses were already set forth. Our punch was cooling in an ornamental lake, on whose margin the bower was raised. This piece of water (with an island in the middle which might have been the salad for supper) was of a circular form, and he had constructed a fountain in it, which, when you set a little mill going and took a cork out of a pipe, played to that powerful extent that it made the back of your hand quite wet."

He also meets Wemmick's father, called "aged parent" or just "aged" by Wemmick, if he calls him anything else I didn't see it. The aged likes being nodded to, so Pip and Wemmick spend quite a lot of time nodding. From this I would have thought the aged was hard of hearing, but he seemed to hear, at least he answers Wemmicks questions and speaks to them both. I guess he just likes nodding, after all. When Pip asks what Jaggers thinks of his "castle", Wemmick replies:

“Never seen it,” said Wemmick. “Never heard of it. Never seen the Aged. Never heard of him. No; the office is one thing, and private life is another. When I go into the office, I leave the Castle behind me, and when I come into the Castle, I leave the office behind me. If it’s not in any way disagreeable to you, you’ll oblige me by doing the same. I don’t wish it professionally spoken about.”

In the morning they return to Jaggers office, the closer they get the more Wemmick returns to his business personality:

"Our breakfast was as good as the supper, and at half-past eight precisely we started for Little Britain. By degrees, Wemmick got dryer and harder as we went along, and his mouth tightened into a post-office again. At last, when we got to his place of business and he pulled out his key from his coat-collar, he looked as unconscious of his Walworth property as if the Castle and the drawbridge and the arbor and the lake and the fountain and the Aged, had all been blown into space together by the last discharge of the Stinger."