The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

Chuzzlewit, Chapters 18 - 20

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

LOL. Yes, Tristram, I am one of those who had to skim through the first page of the next chapter to see where the action was. Although, I'm being good and holding off until the weekend to read the next instalment fully.

LOL. Yes, Tristram, I am one of those who had to skim through the first page of the next chapter to see where the action was. Although, I'm being good and holding off until the weekend to read the next instalment fully.I sure am glad we're starting to move along now. I have to be honest and say that I found the scenes in New York and at Todger's a bit tedious. I did enjoy reading them in themselves, however, I felt I got 'stuck' there as they seemed to go on far too long and didn't add much to the story beyond what could have been said in a more round about way. Sorry Dickens. I think someone said before, some of the chapters seem more fitting as scenes from Sketches of Boz. Hence the reason it's been a bit of an effort to get started reading each instalment, however, once I'm started, I'm really into it.

Would it be so wrong to suggest that Mercy is deserving of the scoundrel Jonas?!

Would it be so wrong to suggest that Mercy is deserving of the scoundrel Jonas?!Just the thought of her having to fend for herself, without her father continually there to smooth over life, to hold her up on her pedestal and encourage her spoilt and childish behaviour. Part of me knows she needs to be brought down a peg or five, however, I fear her feistiness would only enflamed the possible consequences.

I find it intriguing why Jonas should pick Mercy over Cherry, especially when we see that Mercy is disgusted by everything Jonas does. The only think I can think is that she seems to be a challenge for Jonas and that's what he wants. Something to break and put down beneath him, just as he has tried (but I think failed) to do with Chuffy.

Chuffy, what a great character. I thought the scene where Mrs Gamp's complains of Chuffy not leaving his dead master, quite funny in her reaction, but also very touching too. This is why I think Jonas has failed in his chiding of Chuffy, since Chuffy's devotion to Anthony never weakens. This probably made matters worse as Jonas was disdainful of that loyalty that wasn't shown to him from their employee. Therefore, perhaps, he sees Mercy as an easy target. Finally someone to terrorise into subservience so he can be the authoritative figure over someone else.

In Chapter 19 as they prepare for the funeral of Anthony Chuzzlewit, Mr. Mould makes the following remarks:

In Chapter 19 as they prepare for the funeral of Anthony Chuzzlewit, Mr. Mould makes the following remarks:"There is no limitation, there is positively NO limitation'--opening his eyes wide, and standing on tiptoe--'in point of expense! I have orders, sir, to put on my whole establishment of mutes; and mutes come very dear, Mr Pecksniff; not to mention their drink."

Maybe you all already knew, but I'm wondering why there would be mutes at a funeral so of course I looked it up:

The mute’s job was to stand vigil outside the door of the deceased, then accompany the coffin. The main purpose of a funeral mute was to stand around at funerals with a sad, pathetic face. A symbolic protector of the deceased, the mute would usually stand near the door of the home or church. In Victorian times, mutes would wear somber clothing including black cloaks, top hats with trailing hatbands, and gloves. There are plenty of accounts of mutes in Britain by the 1700s, and by Dickens’s time their attendance at even relatively modest funerals was almost mandatory. They were a key part of the Victorians’ extravagant mourning rituals, which Dickens often savaged as pointlessly, and often ruinously, expensive.

Mutes died out in the 1880s/90s and were a memory by 1914. Dickens played his part in their demise, as did fashion. Victorian funeral etiquette was complex and constantly changing, as befitted a huge industry, which partly depended on status anxiety for the huge profits Dickens criticised. What did for them most of all, though, was becoming figures of fun – mournful and sober at the funeral, but often drunk shortly afterwards.

In Britain, most mutes were day-labourers, paid for each individual job. In one of the many yarns told about them, a mute doubled up as a waiter at the meal after one funeral. The deceased’s brother asked him to approach a gentleman at the head of the table to say he wished to take a glass of wine with him. So he instantly changed his demeanour from friendly waiter to mournful mute, went up to the man and quietly said: “Please, sir, the corpse’s brother would like to take a glass o’wine wi’ ye.”

Apparently Oliver Twist was also a mute, but I had forgotten that.

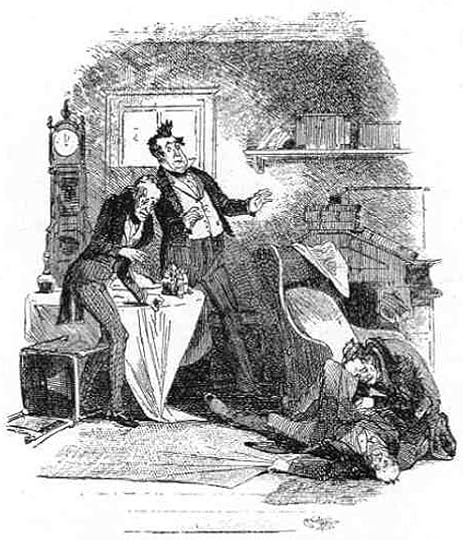

When I was looking at the illustration in Chapter 18 of the death of Anthony Chuzzlewit I thought it strange that Jonas looked as old as his father, but going back to the chapter we first meet them in it says this:

When I was looking at the illustration in Chapter 18 of the death of Anthony Chuzzlewit I thought it strange that Jonas looked as old as his father, but going back to the chapter we first meet them in it says this:"Then there were Anthony Chuzzlewit, and his son Jonas; the face of the old man so sharpened by the wariness and cunning of his life, that it seemed to cut him a passage through the crowded room, as he edged away behind the remotest chairs; while the son had so well profited by the precept and example of the father, that he looked a year or two the elder of the twain, as they stood winking their red eyes, side by side, and whispering to each other softly."

In Chapter 19 I also find:

In Chapter 19 I also find:"In short, the whole of that strange week was a round of dismal joviality and grim enjoyment; and every one, except poor Chuffey, who came within the shadow of Anthony Chuzzlewit's grave, feasted like a Ghoul."

I wanted to know what Ghouls feast on and I found this:

"What is a ghoul? Well, today's definition is someone who kills without thought, mutilates the corpse, and perhaps dines on it either by drinking the blood or eating the flesh. Today's definition is based on encounters of the past. Ghouls are flesh eaters. While they are more frequently associated with corpses, they are known to feed on human children, infants, and occasionally weak and sickened adults. Ghouls are rumored to live near graveyards and in desolate places where they can safely feed on the freshly deceased and for attacking and feasting on a tired unsuspecting traveler."

Wow. Ghouls and mutes. Nothing like dipping your pen in the inkwell and writing a rousing funeral into your story. As always, thanks for your time, research and pics Kim... and what else would Dickens call an undertaker than Mr. Mould?

Wow. Ghouls and mutes. Nothing like dipping your pen in the inkwell and writing a rousing funeral into your story. As always, thanks for your time, research and pics Kim... and what else would Dickens call an undertaker than Mr. Mould?I'm glad Mrs Gamp has made her first appearance in the story. I felt the story was limping along a bit too much, the pebble getting larger in my shoe each page but now we should pick up some more interest.

While Dickens does enjoy a long, rambling commentary and description at times, he also can easily be incisive and precise as well. When Dickens describes the little birds moving in their cages as "a little ballet of despair" it is a perfect vignette. Also, it seems to reflect the larger reality of some of the human characters in the novel so far, such as Mark Tapley and Tom Pinch who are also trapped within the caged conventions of social status.

Much like the chained goldfinch in Fabritius's picture, Tom and Mark are in a state of capture by Mr. Pecksniff or MCjr.

... a totally unrelated comment but I'm reading The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt now. It is a wonderful novel.

Yes Kate, I do think that Merry and Jonas deserve each other. Great research, Kim. Thanks. As you say, Peter, at least the novel is getting a move on.

Yes Kate, I do think that Merry and Jonas deserve each other. Great research, Kim. Thanks. As you say, Peter, at least the novel is getting a move on.Mrs Gamp, Mr Mould and Chuffey; this is the first part of the novel that I have remembered since reading it years ago. Such exquisite Dickens. Poor ol' Chuffey, the one deserving of most respect is, typically, ignored; even despised.

Kate,

Kate,Merry and Jonas might deserve each other, but still I would have that that with regard to a husband like Jonas, Charity would have had more merits still ;-)

The death of Anthony Chuzzlewit and the ensuing funeral as well as the strange behaviour of Jonas to me seem like another variation on the themes of hypocrisy and greed that run throughout the whole novel, and from the fact that they are better-crafted than the somehow additive events in the first three America chapters, one might also assume that the incidents described in Chapters 18 to 20 were part of the original draught of the novel.

The death of Anthony Chuzzlewit and the ensuing funeral as well as the strange behaviour of Jonas to me seem like another variation on the themes of hypocrisy and greed that run throughout the whole novel, and from the fact that they are better-crafted than the somehow additive events in the first three America chapters, one might also assume that the incidents described in Chapters 18 to 20 were part of the original draught of the novel.Every single detail about the undertaker Mould and his business sheds light on the hypocrisy and the mercantile interests connected with the business, even the mutes - thanks, Kim! -, about whom it is aptly said

"two mutes were at the house-door, looking as mournful as could be reasonably expected of men with such a thriving job in hand".

We readers know that Jonas has longed for his father's death and begrudged him every single hour of his existence - in this context, Chuffey's frequent exclamation, "His own son", takes on a double meaning -, and he must suspect that people in general must have known this and would probably also suspect worse ... and that is why he gives the order that nothing be spared in his father's funeral, which is, all the same, a very poor one, with only one honest mourner around.

Then there are certain passages full of dramatic irony, like this one from Chapter 18:

Then there are certain passages full of dramatic irony, like this one from Chapter 18:"'I grow deafer every day, Chuff,' said Anthony, with as much softness of manner, or, to describe it more correctly, with as little hardness as he was capable of expressing.

'No, no,' cried Chuffey. 'No, you don't. What if you did? I've been deaf this twenty year.'

'I grow blinder, too,' said the old man, shaking his head.

'That's a good sign!' cried Chuffey. 'Ha! ha! The best sign in the world! You saw too well before.'

He patted Anthony upon the hand as one might comfort a child, and drawing the old man's arm still further through his own, shook his trembling fingers towards the spot where Jonas sat, as though he would wave him off. But, Anthony remaining quite still and silent, he relaxed his hold by slow degrees and lapsed into his usual niche in the corner; merely putting forth his hand at intervals and touching his old employer gently on the coat, as with the design of assuring himself that he was yet beside him."

It seems as though Chuffey knew more than his two employers might suspect, e.g. that his son had rather see him dead, and as though he wanted to spare Anthony the knowledge of it. - By the way, the two old men's relation is described very touchingly here, in a novel that as yet has not given much room to the pleasant and warmer sides of human behaviour.

And then there is the death scene of Anthony! Brilliant Dickens, this really gives you the creeps:

And then there is the death scene of Anthony! Brilliant Dickens, this really gives you the creeps:"He had fallen from his chair in a fit, and lay there, battling for each gasp of breath, with every shrivelled vein and sinew starting in its place, as if it were bent on bearing witness to his age, and sternly pleading with Nature against his recovery. It was frightful to see how the principle of life, shut up within his withered frame, fought like a strong devil, mad to be released, and rent its ancient prison-house. A young man in the fullness of his vigour, struggling with so much strength of desperation, would have been a dismal sight; but an old, old, shrunken body, endowed with preternatural might, and giving the lie in every motion of its every limb and joint to its enfeebled aspect, was a hideous spectacle indeed."

Do not forget how fearful Anthony has seemed of death during his conversation before! The old miser clinging to life with all his might, and yet never having lived at all.

Dickens rounds this off with a very wise, and yet utterly sarcastic remark at the end of the chapter:

"Plunge him to the throat in golden pieces now, and his heavy fingers shall not close on one!"

Peter has already pointed out this quotation, but I'm going to give it in its larger context here - for the breathtaking morbid beauty of it:

Peter has already pointed out this quotation, but I'm going to give it in its larger context here - for the breathtaking morbid beauty of it:"and in every pane of glass there was at least one tiny bird in a tiny bird-cage, twittering and hopping his little ballet of despair, and knocking his head against the roof; while one unhappy goldfinch who lived outside a red villa with his name on the door, drew the water for his own drinking, and mutely appealed to some good man to drop a farthing's-worth of poison in it."

These birds, each of them confined to their own little cage - and these cages are lavishly adorned! -, what might they stand for? ;-)

An interesting feature of Mrs. Gamp's is that she is a midwife and at the same time also a nurse and helps prepare people for their funerals. Now one might say that at that time death was not yet a taboo but part of people's everyday lives, but even here Dickens throws in some hints at the theme of hypocrisy:

An interesting feature of Mrs. Gamp's is that she is a midwife and at the same time also a nurse and helps prepare people for their funerals. Now one might say that at that time death was not yet a taboo but part of people's everyday lives, but even here Dickens throws in some hints at the theme of hypocrisy:"As she was by this time in a condition to appear, Mrs Gamp, who had a face for all occasions, looked out of the window with her mourning countenance, and said she would be down directly."

Ah, Mrs. Gamp, you are really the most remarkable of women:

Ah, Mrs. Gamp, you are really the most remarkable of women:"'Ah!' repeated Mrs Gamp; for it was always a safe sentiment in cases of mourning. 'Ah dear! When Gamp was summoned to his long home, and I see him a-lying in Guy's Hospital with a penny-piece on each eye, and his wooden leg under his left arm, I thought I should have fainted away. But I bore up.'

If certain whispers current in the Kingsgate Street circles had any truth in them, she had indeed borne up surprisingly; and had exerted such uncommon fortitude as to dispose of Mr Gamp's remains for the benefit of science. But it should be added, in fairness, that this had happened twenty years before; and that Mr and Mrs Gamp had long been separated on the ground of incompatibility of temper in their drink."

Three cheers to you!

I also liked this little detail about Mr. Mould, whose hypocrisy seems to go with his business:

I also liked this little detail about Mr. Mould, whose hypocrisy seems to go with his business:"In the passage they encountered Mr Mould the undertaker; a little elderly gentleman, bald, and in a suit of black; with a notebook in his hand, a massive gold watch-chain dangling from his fob, and a face in which a queer attempt at melancholy was at odds with a smirk of satisfaction; so that he looked as a man might, who, in the very act of smacking his lips over choice old wine, tried to make believe it was physic."

It's also quite endearing of the narrator to talk about "Mr. Mould and his merry men" ;-)

Funny also how Mr. Mould and the doctor pretend not to know each other. This might be especially important for the doctor's reputation:

Funny also how Mr. Mould and the doctor pretend not to know each other. This might be especially important for the doctor's reputation:"It was a great point with Mr Mould, and a part of his professional tact, not to seem to know the doctor; though in reality they were near neighbours, and very often, as in the present instance, worked together. So he advanced to fit on his black kid gloves as if he had never seen him in all his life; while the doctor, on his part, looked as distant and unconscious as if he had heard and read of undertakers, and had passed their shops, but had never before been brought into communication with one."

Then the end of Chapter 19 adopts a more serious and bitter tone:

Then the end of Chapter 19 adopts a more serious and bitter tone:"Not in the churchyard? Not even there. The gates were closed; the night was dark and wet; the rain fell silently, among the stagnant weeds and nettles. One new mound was there which had not been there last night. Time, burrowing like a mole below the ground, had marked his track by throwing up another heap of earth. And that was all."

What I also liked about these chapters is to see Pecksniff and Jonas trying to outwit each other. Pecksniff knows that during the funeral week he can master Jonas to a certain extent, but later on Jonas regains ascendency, and it is interesting how he even turns Pecksniff's hypocrisy against him saying that in marrying Merry he has chosen the daughter Pecksniff was readier to part with - he takes Pecksniff's hypocrisy, which he knows for hypocrisy, literally - so that it would only be fair in Pecksniff to add another thousand pounds to the dowry.

What I also liked about these chapters is to see Pecksniff and Jonas trying to outwit each other. Pecksniff knows that during the funeral week he can master Jonas to a certain extent, but later on Jonas regains ascendency, and it is interesting how he even turns Pecksniff's hypocrisy against him saying that in marrying Merry he has chosen the daughter Pecksniff was readier to part with - he takes Pecksniff's hypocrisy, which he knows for hypocrisy, literally - so that it would only be fair in Pecksniff to add another thousand pounds to the dowry.Jonas's base worldliness and his lack of any ability of higher feelings and reflections is wonderfully set in contrast to the narrative voice, as in the following passage in Chapter 20:

" It was a lovely evening in the spring-time of the year; and in the soft stillness of the twilight, all nature was very calm and beautiful. The day had been fine and warm; but at the coming on of night, the air grew cool, and in the mellowing distance smoke was rising gently from the cottage chimneys. There were a thousand pleasant scents diffused around, from young leaves and fresh buds; the cuckoo had been singing all day long, and was but just now hushed; the smell of earth newly-upturned, first breath of hope to the first labourer after his garden withered, was fragrant in the evening breeze. It was a time when most men cherish good resolves, and sorrow for the wasted past; when most men, looking on the shadows as they gather, think of that evening which must close on all, and that to-morrow which has none beyond.

'Precious dull,' said Mr Jonas, looking about. 'It's enough to make a man go melancholy mad.'"

Tristram wrote: "Then the end of Chapter 19 adopts a more serious and bitter tone:

Tristram wrote: "Then the end of Chapter 19 adopts a more serious and bitter tone:"Not in the churchyard? Not even there. The gates were closed; the night was dark and wet; the rain fell silently, among the stagn..."

Tristram

It always makes me pause and smile, when amid the gush of words that Dickens so frequently uses, there will come a tiny gem of a phrase that sounds so clear, and means so much. "And that was all." how perfect is that in Ch 19?

Tristram wrote: "Peter has already pointed out this quotation, but I'm going to give it in its larger context here - for the breathtaking morbid beauty of it:

Tristram wrote: "Peter has already pointed out this quotation, but I'm going to give it in its larger context here - for the breathtaking morbid beauty of it:"and in every pane of glass there was at least one tin..."

Tristram

My understanding is these shackled birds were often placed near another tiny chain that was connected to tiny thimble-like "buckets" that contained their drinking water. In order to drink, the birds had to use their bills to pull up the chain to reach their water. Evidently, this was entertainment and lead to bragging rites for the owners of their captive birds.

The goldfinch in the quotation you refer mutely appeals to be poisoned. Thus these rather fancy cages of glitter and guild are actually prisons, the bird's world confined, and the birds reduced to performing tricks in order to survive. Since the bird wants death, my assumption is these birds represent/symbolize those who are the victims of greed and power of those who, while they may control the birds (people), actually reveal their own insensitivity, cruelty and greed. Cages can be social, economic, educational and the jailors can come in many forms ... educators, parents, professionals.

Tom to Pecksniff, the Chuzzlewit father and son, the customers and Mould would be examples.

Peter wrote: "My understanding is these shackled birds were often placed near another tiny chain that was connected to tiny thimble-like "buckets" that contained their drinking water."

Peter wrote: "My understanding is these shackled birds were often placed near another tiny chain that was connected to tiny thimble-like "buckets" that contained their drinking water."Now you have me interested in caged birds back in Dickens days, here's what I found:

From: "Victorian London - Publications - Social Investigation/Journalism - Round London : Down East and Up West, by Montagu Williams Q.C., 1894"

"I had often heard of the East End bird-fanciers, and, as most of their business is transacted on a Sunday morning, I had resolved to set off, immediately after breakfast on the following day, to visit their haunts, namely, Sclater Street, Shoreditch, and the neighbouring courts and alleys. Sclater Street was soon reached, and at once I felt that the interest of the place had been in no way overstated. Here was to be seen the East End bird-fancier in all his glory, surrounded by his pets and his pals. This little Street in Shoreditch forms the common meeting-ground for buyer and seller, chopper and changer, and I can safely say that nowhere in London is there to be seen so interesting a concourse of people. They are all absorbed in birds and bird-life. If you stand at one end of the narrow street and cast your eyes towards the other extremity, the scene presented is one long line of commotion and bustle. You hear remarks such as these: “Don’t desert the old firm, guvnor;” “Come, now, that’s a deal ;“ and “Wet the bargain, Bill.”

One side of the crowded thoroughfare is entirely taken up with shops, in the windows of which are to be seen all manner of wicker and fancy cages—from the largest “breeder” to the tiniest “carrying cage “—and birds of every description dear to the fancy—linnets, mules, canaries, chaffinches, bullfinches, starlings, and “furriners.” The cages are ranged in rows all round the wall. Each vendor is busy shouting out invitations to the crowd to come and buy or “do a deal,” which, in most cases, means a “swop,” with a bit thrown in on one side or the other just to balance the bargain. The wares are not confined to the inside and outside of the shops. In the gutter and roadway are crates and boxes tenanted by fowls, pigeons, guinea-pigs,. and hedgehogs.

I walked on, and the next thing that arrested my attention was an article that hung on the wall outside a shop. It looked like a cross between a doll’s house and a bird-cage. In the centre was a linnet standing on a perch, to which he was attached by a tiny chain fastened to his leg. On the right-hand side, separated from the bird by a door, was a string suspending a water glass, and working on little pulleys. The linnet had to exercise a good deal of ingenuity in order to slake his thirst. He had to hop forward, push open the door, pull up the string with his bill, and, when the water vessel came within reach, steady it with his claws while he drank.

During the week a considerable portion of the fancier’s time is spent in listening to the birds that are matched to warble against one another. The places of venue for these Contests are various coffee-shops and public-houses. Very often a large concourse of people will assemble to listen to the competitions.

A word or two about these singing matches may be of interest. A long course of preparatory training is essential. To induce a young bird to sing, he is brought into the presence of a tried songster, the cages being placed side by side. In the case of some beershops in Shoreditch, Westminster, and Seven Dials, the bar-parlour is used so frequently for matches that it wears all the appearance of a bird-dealer’s shop, being crowded with cages and other paraphernalia of the fancier.

The fancier’s love for his pets is truly astonishing. He will sit for hours in his favourite “ public” listening to their trills and encouraging them to further effort. Birds are trained not only by the example of other birds but by the whistle of the fancier himself. Some birds can warble as many as seven or eight “julks,” as each change of trill is called. At a singing match the victory goes to that bird which, in a given time, trills the greater number of “julks.” The cages containing the little competitors are hung on the wall, and needless to say no other birds are permitted to remain In the room while the “race” is going on. It sometimes happens that one of the competitors will refuse to utter a note. It is against the rules, and a most serious offence, to coax a bird to sing. Absolute silence, indeed, has to be maintained by all present."

Like Peter and Hilary I want to thank you, Kim, for that contribution. Interestingly, the contemporary observer does not really seem to have seen any cruelty in the fancier's way of making it so difficult for the bird to drink. - I hope my wife won't read of this, otherwise she is going to apply such a tricky conundrum contrivance to our house bar ;-)

Like Peter and Hilary I want to thank you, Kim, for that contribution. Interestingly, the contemporary observer does not really seem to have seen any cruelty in the fancier's way of making it so difficult for the bird to drink. - I hope my wife won't read of this, otherwise she is going to apply such a tricky conundrum contrivance to our house bar ;-)

Peter wrote: "Tristram

Peter wrote: "TristramIt always makes me pause and smile, when amid the gush of words that Dickens so frequently uses, there will come a tiny gem of a phrase that sounds so clear, and means so much. "And that was all." how perfect is that in Ch 19?

night was dark and wet; the rain fell silently..."

I think this is perfectly perfect, Peter! Dickens was a master of language and he was capable of both the most verbose of pathos and the crisp effect likewise, sometimes offsetting the one against the other. If we had time enough, we could probably find many of these little gems in any Dickens novel.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Peter has already pointed out this quotation, but I'm going to give it in its larger context here - for the breathtaking morbid beauty of it:

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Peter has already pointed out this quotation, but I'm going to give it in its larger context here - for the breathtaking morbid beauty of it:"and in every pane of glass there was..."

Peter,

a very interesting interpretation that does justice to the overall theme of the novel. Mine was actually bleaker still in that I would have read the birds as symbols of people in general, who live their lives in the cages of their own desires and fears, just like Anthony did, which becomes clear when he exhibits such a crazy fear of death.

However, there is one blemish to my interpretation: The bird in Dickens's example clearly seems to implore the passers-by to relieve him of his existence, whereas Anthony and most people in generally cling to life ... for dear life actually ;-) This latter aspect is better covered by your reading of the imagery.

Interestingly my first teaching job was in Shoreditch, (technically Bethnal Green) and the school was literally just around the corner from the animal market described. I used to pass the place on my walk to the tube station. It was actually at a place called Arnold Circus, if you want to look at a street map.

Interestingly my first teaching job was in Shoreditch, (technically Bethnal Green) and the school was literally just around the corner from the animal market described. I used to pass the place on my walk to the tube station. It was actually at a place called Arnold Circus, if you want to look at a street map. I never saw the animal market, thank goodness (!) as it was held on Sundays. But it was (in)famous, and there was an outcry against the conditions the animals were held in. They were mostly domestic pets - small mammals and birds - but also some wild animals. It was closed down in the late 1970's.

Perhaps a little different from Dickens's day, but not so very much. And who would have thought the animal market would have lasted so long!

This continues to be a fascinating discussion, even in retrospect. Thanks to all involved :)

Jean

JeanI guess a specific physical location will always be just that ... a specific place on a grid map with co-ordinates. Yet what history each place must hold as time and the centuries pass! A place may alter its physical shape but the human nature that was once there will always be there. The physical shape will alter, sometimes for the better. Our own human shapes and natures too often remain the same; that is the great shame of life.

That's fascinating information about the animal market, Jean. The fact that you were there when it was still in operation gives it a whole new level of reality.

That's fascinating information about the animal market, Jean. The fact that you were there when it was still in operation gives it a whole new level of reality.

Yes, I don't think the little birds had the chains described in Kim's post, but certainly there was uproar about wild animals such as polecats confined in little cages, to be sold. I think they put them with the ferrets. It took a while for it to get closed down.

Yes, I don't think the little birds had the chains described in Kim's post, but certainly there was uproar about wild animals such as polecats confined in little cages, to be sold. I think they put them with the ferrets. It took a while for it to get closed down.

this week's reading portion must have come as some sort of relief to all those who had the impression that this novel is lacking pace and structure because certain events have started to unfold. There is the death of Anthony Chuzzlewit and the very strange and superstitious behaviour of his loving paragon of a son, and the marriage plan of this self-same son also seems to come to its more or less unexpected close. The instalment ends a certain predicament of Pecksniff's that results from his attempts at running with the hare and hunting with the hounds, i.e. of furthering his interrelations with the wealthy Jonas and at the same time trying to win the favour of old Martin, who hates his family like the plague - and what a hell of a cliffhanger Dickens uses here:

"Tom's teeth chattered in his head, and he positively staggered with amazement, at witnessing the extraordinary effect produced on Mr Pecksniff by these simple words. The dread of losing the old man's favour almost as soon as they were reconciled, through the mere fact of having Jonas in the house; the impossibility of dismissing Jonas, or shutting him up, or tying him hand and foot and putting him in the coal-cellar, without offending him beyond recall; the horrible discordance prevailing in the establishment, and the impossibility of reducing it to decent harmony with Charity in loud hysterics, Mercy in the utmost disorder, Jonas in the parlour, and Martin Chuzzlewit and his young charge upon the very doorsteps; the total hopelessness of being able to disguise or feasibly explain this state of rampant confusion; the sudden accumulation over his devoted head of every complicated perplexity and entanglement for his extrication from which he had trusted to time, good fortune, chance, and his own plotting, so filled the entrapped architect with dismay, that if Tom could have been a Gorgon staring at Mr Pecksniff, and Mr Pecksniff could have been a Gorgon staring at Tom, they could not have horrified each other half so much as in their own bewildered persons.

'Dear, dear!' cried Tom, 'what have I done? I hoped it would be a pleasant surprise, sir. I thought you would like to know.'

But at that moment a loud knocking was heard at the hall door."

Can we really muster up enough self-discipline not to read on or at least flick into the next chapter to see whether it picks up the story where Dickens left it off?

Last not least we get to know one of the most colourful and memorable Dickens characters - I am talking, of course, of Mrs. Gamp, who is going to enrich this novel in many ways, and who was probably added for the same reasons that Dickens some years ago pulled Sam Weller out of his hat.

I have noted down quite some memorable quotations from these three chapters, but I will, of course, restrain myself for the moment in order to defer to you, the Highly Estimated Members of the Pickwick Club.