The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Our Mutual Friend

>

Book 4 Chapters 5-7

message 1:

by

Peter

(new)

Sep 23, 2017 04:47PM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

Hello Curiosities

Tristram has other obligations at school ( I suspect overloaded with marking) and Kim is on vacation (could it be the first stirrings of the Christmas season?) so I'm standing in this week. I am in Portugal to visit my wife's family. And so, first, hello to Tristram, Jean and Hilary. I'm in Europe with you, and perhaps as close to you as I will ever be. Hello neighbours!

This chapter is titled “Concerning the Mendicant’s Wife.” For interest, let's frame the first portion of this chapter around the concept that was known as the “separate spheres” of domestic life in the Victorian times. https://www.google.ca/search?q=separa... Basically, the man went to work, dealt with the economic world and its rough and tumble ways while the wife stayed home and ensured that the domestic world of the home offered a quiet and tranquil setting.

In this chapter we see two examples of the concept of separate spheres playing out for us. First, Mr. Wilfer returns home from witnessing the marriage of Bella to John. At the end of the previous chapter Mr Wilfer says “Goodbye darling! Take her away, my dear John. Take her home.” With these words we see the concept of separate spheres being enacted. Mr. Wilfer turns his daughter over to her husband, and then comments how it is John's duty to take her home. It is now John’s duty to provide a home and Bella’s duty to manage that home.

And so Mr. Wilfer returns to his home and the “ impressive gloom” of Mrs Wilfer’s reception. Mr. Wilfer has to feign ignorance of Bella’s marriage to John Rokesmith. The ensuing dialogue between the Wilfer’s offers us a delightful spot of humour in a novel that has, so far, been lacking much laughter for the reader. It is refreshing to listen to their dialogue and imagine how this scene would be read or performed. In earlier chapters some of you have mentioned how hearing the novel as opposed to reading it is a much more enjoyable experience. I imagine this chapter must be delightful to listen to. Lavinia’s comments and the presence of Mr. Sampson heighten the scene even more. I laughed out loud when Mr. Wilfer gladly agreed with his wife that he should go to bed. In my mind’s eye I imagine how Mr Wilfer pulls the covers over his head and enjoys a pleasant chuckle with himself as he recalls how he just pulled the wool over his wife’s eyes.

Bella’s first visit to her parent’s home as Rokesmith’s wife occurs with her showering a blizzard of kisses for everyone. Bella recounts how delightful her “doll’s house” is and how “ de-lightfully furnished” and how “ de-cidedly … economical and orderly” they live on £150 a year. Bella, unlike Nora in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, is totally happy to be domesticated. As LindaH noted in last week’s comments, Bella is not a very good cook. Nothing is mentioned about how content Rokesmith/Harmon is with Bella’s cooking in this chapter. Perhaps their little maid does the cooking for the happy new couple. Some things remain best in our imaginations.

Thoughts:

* OMF is a rather dark, brooding and somber novel. Why might Dickens have chosen to bring humour into the novel at this particular point?

* We have witnessed a very sharp change in Bella’s character. Once aloof and seemingly consumed with wealth and money, she is now apparently thoroughly domesticated and content to have no expectations beyond being a housewife. To what extent do you find this transition to be believable?

On the way home from visiting her parents Rokesmith asks Bella “whether you wouldn't like me to be rich?” Bella tells him she would” almost be afraid to try.” They discuss the extent that money can alter a person’s personality. We learn that instead of the magnificent clothes and lifestyle that Bella enjoyed with the Boffins her shoes are now “a full size too large” and she does not want a carriage for her transportation. Bella then tells John that “your wishes are as real to me as the wishes in the fairy tale that were all fulfilled as soon as spoken.”

With this comment Dickens brings the concept of the fairy tale of Cinderella to the attention of the reader. With the mention of shoes that fit - or not - we find echoes of Cinderella. The added comment of not wanting a carriage further enhances how Bella has undergone a transformative experience, just like Cinderella. The difference is, of course, Bella does not want a carriage and the shoes do not fit. In addition, Bella is unaware of how princely rich John Harmon is. Clever of Mr Dickens to put such a slant and twist on the original fairy tale. John, as the princely figure in waiting, has just received the symbolic conformation that his princess is quite happy to wear shoes that do not fit and to walk in the mud rather than ride in a carriage. She is now a thoroughly domesticated woman.

Our second example of the concept of separate spheres comes as we learn that Bella happily walks with Rokesmith to the railroad each morning and meets him again at the railway station at night. We read at how proficient in “household affairs” Bella has become. Whatever Rokesmith/Harmon does in the city does not matter. He does his manly thing at work and she does her wifely thing at home. All rather neat, clean, and, well, newly-minted middle class Victorians.

Much of Bella’s knowledge of being a wife comes from “a sage volume entitled The Complete British Family Housewife.” I found it interesting how often Dickens has used books to help instruct the characters in the novel. We have seem Wegg pompously reading history to Boffin, Boffin searching out books on misers, and now Bella is reading books on how to be a perfect housewife. Books do indeed define their readers. Here is a link to the famous book of household management in the 19C that was published in 1861. . https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isabe...

A groan or two might be in order as it appears Dickens has turned Bella into a domestic goddess like Mrs Beeton. And yet it is true. This chapter is about domestic life and how the males and the females have very specific and defined roles. Consider the fact that Dickens ends this chapter on a perfect note of domestic bliss. Bella is pregnant.

Thoughts

* To what extent did you find this chapter too sugary and sweet?

* The Fairy Tale motifs seem to be slowly unravelling for us. I would suggest that with the Bella-Rokesmith relationship we have also shades of Beauty and the Beast. Bella has finally come to see and realize Rokesmith as he really is. He is not a monster, but rather a good person. Once she has been able to see who he is as opposed to what he appeared to be their relationship has grown. Can you find any other fairy tale elements so far in our reading?

Tristram has other obligations at school ( I suspect overloaded with marking) and Kim is on vacation (could it be the first stirrings of the Christmas season?) so I'm standing in this week. I am in Portugal to visit my wife's family. And so, first, hello to Tristram, Jean and Hilary. I'm in Europe with you, and perhaps as close to you as I will ever be. Hello neighbours!

This chapter is titled “Concerning the Mendicant’s Wife.” For interest, let's frame the first portion of this chapter around the concept that was known as the “separate spheres” of domestic life in the Victorian times. https://www.google.ca/search?q=separa... Basically, the man went to work, dealt with the economic world and its rough and tumble ways while the wife stayed home and ensured that the domestic world of the home offered a quiet and tranquil setting.

In this chapter we see two examples of the concept of separate spheres playing out for us. First, Mr. Wilfer returns home from witnessing the marriage of Bella to John. At the end of the previous chapter Mr Wilfer says “Goodbye darling! Take her away, my dear John. Take her home.” With these words we see the concept of separate spheres being enacted. Mr. Wilfer turns his daughter over to her husband, and then comments how it is John's duty to take her home. It is now John’s duty to provide a home and Bella’s duty to manage that home.

And so Mr. Wilfer returns to his home and the “ impressive gloom” of Mrs Wilfer’s reception. Mr. Wilfer has to feign ignorance of Bella’s marriage to John Rokesmith. The ensuing dialogue between the Wilfer’s offers us a delightful spot of humour in a novel that has, so far, been lacking much laughter for the reader. It is refreshing to listen to their dialogue and imagine how this scene would be read or performed. In earlier chapters some of you have mentioned how hearing the novel as opposed to reading it is a much more enjoyable experience. I imagine this chapter must be delightful to listen to. Lavinia’s comments and the presence of Mr. Sampson heighten the scene even more. I laughed out loud when Mr. Wilfer gladly agreed with his wife that he should go to bed. In my mind’s eye I imagine how Mr Wilfer pulls the covers over his head and enjoys a pleasant chuckle with himself as he recalls how he just pulled the wool over his wife’s eyes.

Bella’s first visit to her parent’s home as Rokesmith’s wife occurs with her showering a blizzard of kisses for everyone. Bella recounts how delightful her “doll’s house” is and how “ de-lightfully furnished” and how “ de-cidedly … economical and orderly” they live on £150 a year. Bella, unlike Nora in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, is totally happy to be domesticated. As LindaH noted in last week’s comments, Bella is not a very good cook. Nothing is mentioned about how content Rokesmith/Harmon is with Bella’s cooking in this chapter. Perhaps their little maid does the cooking for the happy new couple. Some things remain best in our imaginations.

Thoughts:

* OMF is a rather dark, brooding and somber novel. Why might Dickens have chosen to bring humour into the novel at this particular point?

* We have witnessed a very sharp change in Bella’s character. Once aloof and seemingly consumed with wealth and money, she is now apparently thoroughly domesticated and content to have no expectations beyond being a housewife. To what extent do you find this transition to be believable?

On the way home from visiting her parents Rokesmith asks Bella “whether you wouldn't like me to be rich?” Bella tells him she would” almost be afraid to try.” They discuss the extent that money can alter a person’s personality. We learn that instead of the magnificent clothes and lifestyle that Bella enjoyed with the Boffins her shoes are now “a full size too large” and she does not want a carriage for her transportation. Bella then tells John that “your wishes are as real to me as the wishes in the fairy tale that were all fulfilled as soon as spoken.”

With this comment Dickens brings the concept of the fairy tale of Cinderella to the attention of the reader. With the mention of shoes that fit - or not - we find echoes of Cinderella. The added comment of not wanting a carriage further enhances how Bella has undergone a transformative experience, just like Cinderella. The difference is, of course, Bella does not want a carriage and the shoes do not fit. In addition, Bella is unaware of how princely rich John Harmon is. Clever of Mr Dickens to put such a slant and twist on the original fairy tale. John, as the princely figure in waiting, has just received the symbolic conformation that his princess is quite happy to wear shoes that do not fit and to walk in the mud rather than ride in a carriage. She is now a thoroughly domesticated woman.

Our second example of the concept of separate spheres comes as we learn that Bella happily walks with Rokesmith to the railroad each morning and meets him again at the railway station at night. We read at how proficient in “household affairs” Bella has become. Whatever Rokesmith/Harmon does in the city does not matter. He does his manly thing at work and she does her wifely thing at home. All rather neat, clean, and, well, newly-minted middle class Victorians.

Much of Bella’s knowledge of being a wife comes from “a sage volume entitled The Complete British Family Housewife.” I found it interesting how often Dickens has used books to help instruct the characters in the novel. We have seem Wegg pompously reading history to Boffin, Boffin searching out books on misers, and now Bella is reading books on how to be a perfect housewife. Books do indeed define their readers. Here is a link to the famous book of household management in the 19C that was published in 1861. . https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isabe...

A groan or two might be in order as it appears Dickens has turned Bella into a domestic goddess like Mrs Beeton. And yet it is true. This chapter is about domestic life and how the males and the females have very specific and defined roles. Consider the fact that Dickens ends this chapter on a perfect note of domestic bliss. Bella is pregnant.

Thoughts

* To what extent did you find this chapter too sugary and sweet?

* The Fairy Tale motifs seem to be slowly unravelling for us. I would suggest that with the Bella-Rokesmith relationship we have also shades of Beauty and the Beast. Bella has finally come to see and realize Rokesmith as he really is. He is not a monster, but rather a good person. Once she has been able to see who he is as opposed to what he appeared to be their relationship has grown. Can you find any other fairy tale elements so far in our reading?

Chapter 6 is titled “A Cry for Help” and a perfect title it is. The previous chapter was one of sugary domestic bliss, harmony, and humour; this chapter is the direct opposite. The placid love of Bella and John is replaced with the turmoil of the Lizzie - Headstone - Wrayburn love triangle. What a mess, and an ultimately bloody and life-threatening mess, this chapter turns out to be. Here, we as readers find no humour, no joy, no comfort, and seemingly no end to Lizzie’s struggle for some normality in her life.

Dickens begins the chapter with the workers of the paper-mill going home and their sounds “of laughter.” Words and expressions such as “cheerful,” “rosy evening,” “ever-widening beauty of the landscape,” and “ there were no immensity of space between mankind and Heaven” tend to lull the reader into a state of harmonious tranquility. To this setting Dickens introduces the discordant presence of Eugene Wrayburn who has come to meet with Lizzie. Wrayburn walks with “a measured step and preoccupied air of one who was waiting.” He sees a Bargemen by a hayrick. The scene reminds me of a Constable painting. http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/c... Lizzie comes as promised, and requests that Wrayburn not touch her. Lizzie implores him to leave her alone. Wrayburn, for his part, with ernest and honest emotion expresses his feelings to her. I admit this speech made me like Wrayburn much more than I have so far in the novel. As with Rokesmith, there is true passion in Wrayburn, but Lizzie asks that he think of Lizzie “as belonging to another station and quite cut off from [Wrayburn] in honour … I am removed from you and your family by being a working girl.” Lizzie begs Wrayburn to leave her lest she be obliged to continually move on in order to avoid him as she could not have a lover of another class. We learn that Lizzie “loved him so in secret - whose heart had long been so full, and he the cause of its overflowing - “.

Well now, isn't this interesting? Lizzie does love Wrayburn, but sees their class differences as being a hurdle too high to leap over. I can't help but think how Dickens has blended the storylines of Bella and Lizzie. From different social backgrounds, their love stories offer the reader a look at how social standing, family background and the nature of a lover create different patterns and plot lines. Lizzie tells Wrayburn that “ there is nothing for us in this life but separation.” OMF is frequently referred to as a novel about money, money, money. To a great degree, I see the novel demonstrate how money defines love. Much like fairy tales such as Cinderella and Beauty and the Beast, the central motif is more about love than riches. Indeed, one could argue that love is the greatest richness there is.

But back to the title of this chapter. Wrayburn wanders along the banks of the river musing how class structure is a “Brute Beast” and Dickens tells us that “the rippling of the river seemed to cause a correspondent stir in his uneasy reflections.” There is the presence of water again. It seems whenever the Thames is present something dreadful occurs. And so it does. Wrayburn is savagely attacked and the person who is “mashing his life” is wearing a red neckerchief. Headstone has finally unleashed the fury of his long-suppressed anger. Lizzie hears strange sounds “like the sounds of blows” and then “a faint groan and a fall into the river.” She sees evidence of a struggle, and then her eyes see “a bloody face turned up towards the moon and drifting away.”

It is at this point of the chapter, and indeed the novel, that we get to watch the the full breadth and depth of Dickens’s style. We may say that the next few paragraphs are over-the-top melodrama and sensationalist writing. My answer is absolutely, and how grand it is.

Lizzie’s early life and skills on the Thames reemerge. Swiftly, and with “a sure touch of her old practiced hand, a sure step of her old practiced foot, a sure light balance of her body, and she was in the boat … and the boat shot out into the moonlight, and she was rowing down the stream as never other woman rowed on English water.” Lizzie rescues Eugene and “seldom removed her eyes from him in the bottom of the boat.”

Thoughts

the rescue of Wrayburn creates an interesting opportunity to reflect on our first meeting with Lizzie in Chapter One of the novel. In what ways can these chapters be compared and contrasted?

With Wrayburn pulled from the water we have echoes of other characters such as John Harmon, Riderhood, and the sailor dressed as John Harmon. What might Dickens be attempting symbolically, structurally, and stylistically in the use of this reoccurring plot device?

At the end of this chapter we learn that Wrayburn is close to death. Will his hand drop? The surgeons cannot believe that Lizzie was capable of the feat of strength necessary to “lift, far less carry, this weight.” I found the last words of this chapter very powerful and moving. the doctor comments “Poor girl, poor girl! She must be amazingly strong of heart, but it is much to be feared that she has set her heart upon the dead. Be gentle with her.” First, with Betty, and now with Eugene Wrayburn, Lizzie Hexam has shown compassion and love. Sadly, the words of the doctor to “be gentle with her” are among the very few caring words directed to Lizzie in the novel.

Thoughts

* It is generally accepted that John Harmon is the central character in OMF. However, more and more, I see this novel as centring around Lizzie Hexam. Could she be our protagonist as much as Harmon?

Dickens begins the chapter with the workers of the paper-mill going home and their sounds “of laughter.” Words and expressions such as “cheerful,” “rosy evening,” “ever-widening beauty of the landscape,” and “ there were no immensity of space between mankind and Heaven” tend to lull the reader into a state of harmonious tranquility. To this setting Dickens introduces the discordant presence of Eugene Wrayburn who has come to meet with Lizzie. Wrayburn walks with “a measured step and preoccupied air of one who was waiting.” He sees a Bargemen by a hayrick. The scene reminds me of a Constable painting. http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/c... Lizzie comes as promised, and requests that Wrayburn not touch her. Lizzie implores him to leave her alone. Wrayburn, for his part, with ernest and honest emotion expresses his feelings to her. I admit this speech made me like Wrayburn much more than I have so far in the novel. As with Rokesmith, there is true passion in Wrayburn, but Lizzie asks that he think of Lizzie “as belonging to another station and quite cut off from [Wrayburn] in honour … I am removed from you and your family by being a working girl.” Lizzie begs Wrayburn to leave her lest she be obliged to continually move on in order to avoid him as she could not have a lover of another class. We learn that Lizzie “loved him so in secret - whose heart had long been so full, and he the cause of its overflowing - “.

Well now, isn't this interesting? Lizzie does love Wrayburn, but sees their class differences as being a hurdle too high to leap over. I can't help but think how Dickens has blended the storylines of Bella and Lizzie. From different social backgrounds, their love stories offer the reader a look at how social standing, family background and the nature of a lover create different patterns and plot lines. Lizzie tells Wrayburn that “ there is nothing for us in this life but separation.” OMF is frequently referred to as a novel about money, money, money. To a great degree, I see the novel demonstrate how money defines love. Much like fairy tales such as Cinderella and Beauty and the Beast, the central motif is more about love than riches. Indeed, one could argue that love is the greatest richness there is.

But back to the title of this chapter. Wrayburn wanders along the banks of the river musing how class structure is a “Brute Beast” and Dickens tells us that “the rippling of the river seemed to cause a correspondent stir in his uneasy reflections.” There is the presence of water again. It seems whenever the Thames is present something dreadful occurs. And so it does. Wrayburn is savagely attacked and the person who is “mashing his life” is wearing a red neckerchief. Headstone has finally unleashed the fury of his long-suppressed anger. Lizzie hears strange sounds “like the sounds of blows” and then “a faint groan and a fall into the river.” She sees evidence of a struggle, and then her eyes see “a bloody face turned up towards the moon and drifting away.”

It is at this point of the chapter, and indeed the novel, that we get to watch the the full breadth and depth of Dickens’s style. We may say that the next few paragraphs are over-the-top melodrama and sensationalist writing. My answer is absolutely, and how grand it is.

Lizzie’s early life and skills on the Thames reemerge. Swiftly, and with “a sure touch of her old practiced hand, a sure step of her old practiced foot, a sure light balance of her body, and she was in the boat … and the boat shot out into the moonlight, and she was rowing down the stream as never other woman rowed on English water.” Lizzie rescues Eugene and “seldom removed her eyes from him in the bottom of the boat.”

Thoughts

the rescue of Wrayburn creates an interesting opportunity to reflect on our first meeting with Lizzie in Chapter One of the novel. In what ways can these chapters be compared and contrasted?

With Wrayburn pulled from the water we have echoes of other characters such as John Harmon, Riderhood, and the sailor dressed as John Harmon. What might Dickens be attempting symbolically, structurally, and stylistically in the use of this reoccurring plot device?

At the end of this chapter we learn that Wrayburn is close to death. Will his hand drop? The surgeons cannot believe that Lizzie was capable of the feat of strength necessary to “lift, far less carry, this weight.” I found the last words of this chapter very powerful and moving. the doctor comments “Poor girl, poor girl! She must be amazingly strong of heart, but it is much to be feared that she has set her heart upon the dead. Be gentle with her.” First, with Betty, and now with Eugene Wrayburn, Lizzie Hexam has shown compassion and love. Sadly, the words of the doctor to “be gentle with her” are among the very few caring words directed to Lizzie in the novel.

Thoughts

* It is generally accepted that John Harmon is the central character in OMF. However, more and more, I see this novel as centring around Lizzie Hexam. Could she be our protagonist as much as Harmon?

Chapter 7 is titled “Better To Be Abel Than Cain.” This title must be an allusion to the Biblical story of Abel and Cain. Cain kills Abel, and when asked where Abel was Cains replies “Am I my brother’s keeper?” So, one question for us to contemplate is how the title of this chapter is connected to the Biblical story.

The chapter begins at the Plashwater Weir-Mill Lock. Riderhood opens the door to Bradley who appears tired and who falls asleep almost immediately. Rogue notices that Bradley’s clothes are ragged, torn, stained with grass, wet and spotted with, as Rogue notices “ I know with what.” Blood. Bradley cuts his hand while eating a meal and “he shook his hand under the smart of the wound and shook the blood over Riderhood’s dress.” Now, why would Headstone want to shake blood onto Riderhood’s clothes? Why would Headstone want to dress exactly like, Rogue Riderhood, even to the specific detail of a red scarf? And why would Headstone have hidden his regular clothes amid brambles and change into them after a wash in the river? And there is the presence of the river, yet again. And there again is the motif of doubles, look-alikes and changes of character or nature. Consider the repeating style and form of a person emerging from the river into a new persona.

Dickens points out the consequences of guilt as Headstone blunders his way back to London and recounts how “a shedder of blood forever strives in vain.” The next day Headstone is back in class but his mind was elsewhere, replaying his struggle with Wrayburn. Charley Hexam comes to see Headstone and delivers the news that Wrayburn is dead. Charley is deeply suspicious of Wrayburn and wants nothing else to do with him. It’s a bit hard for me to take. Charley delivers a moral homily to Headstone in which he says “you are in all your passions so selfish and so concentrated upon yourself that you have not bestowed one proper thought on me.” Oh, please, Charley. And how do you explain your attitude and earlier comments towards your sister Lizzie?

Thoughts

To what extent do you find Charley’s comments selfish and egotistical?

How do you interpret the reasons for Dickens to title this chapter “Better To Be Cain Than Able.”

This chapter seems to be one of doubles and binary opposites. We have the similarity of dress with Riderhood and Headstone and then the rather bizarre doubling of Headstone as he first tracks Wrayburn’s movements and then Riderhood as he tracks Headstone’s movements. What do you make of this plot structure? To what extent do you find it successful?

Earlier, Riderhood, having watched Headstone toss a bundle into the river, decided to go fishing for the bundle tossed in the river rather than follow Headstone. Riderhood, as we know, was a proficient fisherman of bodies, so why not bundles? Lizzie used the skills she learned while working with her father to rescue Wrayburn. Now we see Riderhood successfully find the discarded bundle of clothes thrown into the river by Headstone. And so both Lizzie and Rogue, in their own ways, use their earlier skills to resurrect a person, or a person’s clothes from the river. The Thames both takes life and perhaps even restores life. The Thames is a powerful presence in OMF.

Thoughts

* As we move towards the end of the novel Dickens must begin to tie up all the loose ends and events of the story. In what ways has this week’s chapters begun the process of reconciliation and conclusion?

The chapter begins at the Plashwater Weir-Mill Lock. Riderhood opens the door to Bradley who appears tired and who falls asleep almost immediately. Rogue notices that Bradley’s clothes are ragged, torn, stained with grass, wet and spotted with, as Rogue notices “ I know with what.” Blood. Bradley cuts his hand while eating a meal and “he shook his hand under the smart of the wound and shook the blood over Riderhood’s dress.” Now, why would Headstone want to shake blood onto Riderhood’s clothes? Why would Headstone want to dress exactly like, Rogue Riderhood, even to the specific detail of a red scarf? And why would Headstone have hidden his regular clothes amid brambles and change into them after a wash in the river? And there is the presence of the river, yet again. And there again is the motif of doubles, look-alikes and changes of character or nature. Consider the repeating style and form of a person emerging from the river into a new persona.

Dickens points out the consequences of guilt as Headstone blunders his way back to London and recounts how “a shedder of blood forever strives in vain.” The next day Headstone is back in class but his mind was elsewhere, replaying his struggle with Wrayburn. Charley Hexam comes to see Headstone and delivers the news that Wrayburn is dead. Charley is deeply suspicious of Wrayburn and wants nothing else to do with him. It’s a bit hard for me to take. Charley delivers a moral homily to Headstone in which he says “you are in all your passions so selfish and so concentrated upon yourself that you have not bestowed one proper thought on me.” Oh, please, Charley. And how do you explain your attitude and earlier comments towards your sister Lizzie?

Thoughts

To what extent do you find Charley’s comments selfish and egotistical?

How do you interpret the reasons for Dickens to title this chapter “Better To Be Cain Than Able.”

This chapter seems to be one of doubles and binary opposites. We have the similarity of dress with Riderhood and Headstone and then the rather bizarre doubling of Headstone as he first tracks Wrayburn’s movements and then Riderhood as he tracks Headstone’s movements. What do you make of this plot structure? To what extent do you find it successful?

Earlier, Riderhood, having watched Headstone toss a bundle into the river, decided to go fishing for the bundle tossed in the river rather than follow Headstone. Riderhood, as we know, was a proficient fisherman of bodies, so why not bundles? Lizzie used the skills she learned while working with her father to rescue Wrayburn. Now we see Riderhood successfully find the discarded bundle of clothes thrown into the river by Headstone. And so both Lizzie and Rogue, in their own ways, use their earlier skills to resurrect a person, or a person’s clothes from the river. The Thames both takes life and perhaps even restores life. The Thames is a powerful presence in OMF.

Thoughts

* As we move towards the end of the novel Dickens must begin to tie up all the loose ends and events of the story. In what ways has this week’s chapters begun the process of reconciliation and conclusion?

Ch5

Ch5Title?

In a search for Rokesmith's idea to "test" Bella, I found this little line (from his soliloquy) that might explain the title:

“I love her against reason—but who would as soon love me for my own sake, as she would love the beggar at the corner. "

Rokesmith's funds?

In that same chapter I read about how the fired secretary might have been able able to provide a wedding breakfast:

“I could not have done it, but for the fortune in the waterproof belt round my body. Not a great fortune, forty and odd pounds for the inheritor of a hundred and odd thousand! But it was enough. Without it I must have disclosed myself. Without it, I could never have gone to that Exchequer Coffee House, or taken Mrs Wilfer's lodgings.”

Testing Bella?

It was while Rokesmith was realizing the circumstances of mistaken identity that he came up with the idea of...

“proving Bella. The dread of our being forced on one another, and perpetuating the fate that seemed to have fallen on my father's riches—the fate that they should lead to nothing but evil—was strong”

All of the above quotes are from book second, chapter 13. Now to book fourth,chapter 5.

Testing:

In this chapter Bella teases her new husband to test her, the irony being that Rokesmith has been doing that , THAT, since the day they met.

“Try me through some reverse, John—try me through some trial—and tell them after THAT, what you think of me.”

More echoes of Cinderella?

The wicked stepmother?

Well, she's not wicked but Mrs wilfer does make it clear she is not the biological ma:

“No. Your daughter Bella,' said Mrs Wilfer, with a lofty air of never having had the least copartnership in that young lady: of whom she now made reproachful mention as an article of luxury which her husband had set up entirely on his own account, and in direct opposition to her advice: '—your daughter Bella has bestowed herself upon a Mendicant.'

The wicked stepsister?

Again , not wicked, but Lavinia chooses to fly into hysteria and faint over Bella's marriages.

Reference to cinder girl's clothes?

Another reverse, as Bella changes from her pretty appearance to her chore-doer's."...

“trim little wrappers and aprons would be substituted, and Bella, putting back her hair with both hands, as if she were making the most business-like arrangements for going dramatically distracted, would enter on the household affairs of the day."

LindaH wrote: "Ch5

Title?

In a search for Rokesmith's idea to "test" Bella, I found this little line (from his soliloquy) that might explain the title:

“I love her against reason—but who would as soon love me f..."

Hi Linda

Thanks for the thoughtful analysis and hunting down of great quotations. I have missed much. I found the links back to Book 2 Chapter 13 very interesting and exciting. You have demonstrated how Dickens does indeed run his ideas and threads throughout his novels.

Often, there is so much going on, and often so much seems rather inconsequential, that I forget how intricate Dickens really is.

I am intrigued by the fairy tale trope that seems somewhat hidden beneath the main narrative. Your insights are valuable.

Title?

In a search for Rokesmith's idea to "test" Bella, I found this little line (from his soliloquy) that might explain the title:

“I love her against reason—but who would as soon love me f..."

Hi Linda

Thanks for the thoughtful analysis and hunting down of great quotations. I have missed much. I found the links back to Book 2 Chapter 13 very interesting and exciting. You have demonstrated how Dickens does indeed run his ideas and threads throughout his novels.

Often, there is so much going on, and often so much seems rather inconsequential, that I forget how intricate Dickens really is.

I am intrigued by the fairy tale trope that seems somewhat hidden beneath the main narrative. Your insights are valuable.

I was wondering once again as I read another Dickens book, it seems to me that no matter how poor you may be almost all main characters have servants. The Lammles have two servants and John and Bella have a "a clever little servant who is de-cidedly pretty". How do they afford servants? I know that John can afford a servant, but Bella has no idea of his money yet she doesn't seem to find it odd they have a servant.

We have witnessed a very sharp change in Bella’s character. Once aloof and seemingly consumed with wealth and money, she is now apparently thoroughly domesticated and content to have no expectations beyond being a housewife. To what extent do you find this transition to be believable?

When I was reading this chapter I remember thinking I loved Bella's change in character. I love the dear, sweet wife she has become and while I don't know how others would feel about the transition being believable, I certainly believe it, in Dickens novels anything can happen. :-) Hopefully out of Dickens novels too. I also thought as I read this chapter that as Bella was rising in my opinion in some other peoples opinions she is falling. Good, sweet heroines are just not appreciated by certain grumpy people.

And thank you so much Peter for filling in for us.

We have witnessed a very sharp change in Bella’s character. Once aloof and seemingly consumed with wealth and money, she is now apparently thoroughly domesticated and content to have no expectations beyond being a housewife. To what extent do you find this transition to be believable?

When I was reading this chapter I remember thinking I loved Bella's change in character. I love the dear, sweet wife she has become and while I don't know how others would feel about the transition being believable, I certainly believe it, in Dickens novels anything can happen. :-) Hopefully out of Dickens novels too. I also thought as I read this chapter that as Bella was rising in my opinion in some other peoples opinions she is falling. Good, sweet heroines are just not appreciated by certain grumpy people.

And thank you so much Peter for filling in for us.

Hello everyone,

It's time now for one of the grumpy people to show up and have his say ;-) First of all, thank you, Peter, for your inspiring recaps of the chapters. Actually, with all those questions - and with LindaH's links with quotations from earlier on in the book - they are so much more than recaps.

I have never really noticed the fairy-tale-references before in this novel, but in Chapter 5 they are really obvious. If I am not mistaken, Rokesmith even asks Bella three times whether she would not prefer being rich, and if there is one number that occurs a lot in fairy tales, it's the 3. I could not help feeling bemused by the description of homely bliss that Dickens is giving here, turning the capricious Bella into a homespun bore all of a sudden but that is probably the way he, and most others at the time, saw the ideal wife. This division between the public and the private world, and the different spheres of the sexes, also comes out in Schiller's famous poem The Song of the Bell where one extract goes:

Interestingly, we never really learn what it is that John Harmon is doing in the City. It would also be interesting if, among real people, living on a scanty salary, would be as blissful after, let's say three or four years, still. I can't help thinking that maybe the Wilfers also were a happy couple at first and that Mrs Wilfer has learned to despise her husband by and by and become a bitter and mercenary woman because after all, it was her who had to make do with the money her husband brought home.

It's time now for one of the grumpy people to show up and have his say ;-) First of all, thank you, Peter, for your inspiring recaps of the chapters. Actually, with all those questions - and with LindaH's links with quotations from earlier on in the book - they are so much more than recaps.

I have never really noticed the fairy-tale-references before in this novel, but in Chapter 5 they are really obvious. If I am not mistaken, Rokesmith even asks Bella three times whether she would not prefer being rich, and if there is one number that occurs a lot in fairy tales, it's the 3. I could not help feeling bemused by the description of homely bliss that Dickens is giving here, turning the capricious Bella into a homespun bore all of a sudden but that is probably the way he, and most others at the time, saw the ideal wife. This division between the public and the private world, and the different spheres of the sexes, also comes out in Schiller's famous poem The Song of the Bell where one extract goes:

"The man must go out

In hostile life living,

Be working and striving

And planting and making,

Be scheming and taking,

Through hazard and daring,

His fortune ensnaring.

Then streams in the wealth in an unending measure,

The silo is filled thus with valuable treasure,

The rooms are growing, the house stretches out.

And indoors ruleth

The housewife so modest,

The mother of children,

And governs wisely

In matters of family,

And maidens she traineth

And boys she restraineth,

And goes without ending

Her diligent handling,

And gains increase hence

With ordering sense.

And treasure on sweet-smelling presses is spreading,

And turns 'round the tightening spindle the threading,

And gathers in chests polished cleanly and bright

The shimmering wool, and the linen snow-white,

And joins to the goods, both their splendor and shimmer,

And resteth never."

Interestingly, we never really learn what it is that John Harmon is doing in the City. It would also be interesting if, among real people, living on a scanty salary, would be as blissful after, let's say three or four years, still. I can't help thinking that maybe the Wilfers also were a happy couple at first and that Mrs Wilfer has learned to despise her husband by and by and become a bitter and mercenary woman because after all, it was her who had to make do with the money her husband brought home.

As to servants, I think even lower middle class people had them, and that was for two reasons: Firstly, if you wanted to be respected in society, you had to have at least one servant. And secondly, servants did not earn a lot of money, if I remember correctly. There was a tax on male servants, especially if they wore livery, but there was no tax on female servants, and so even not so wealthy families could afford a female servant. Many of those were women who simply had to earn money, and the Victorian world did not offer a lot of jobs for women. If you couldn't be a governess (for lack of education), if you were not married to a craftsman, then you could only work as a servant, and that put you onto a rather weak basis for negotiation of wages and job conditions.

Charley Hexam is terribly selfish, and the narrator even shows some sympathy with Bradley Headstone her:

The illustration in my book shows Bradley lying on the floor with a picture of Cain and Abel on the wall, by the way. Charley is also a character who deliberately chooses to work towards a marriage of convenience when he says that he might marry the schoolmistress: "I hope, before many years are out, to succeed the master in my present school, and the mistress being a single woman, though some years older than I am, I might even marry her. If it is any comfort to you to know what plans I may work out by keeping myself strictly respectable in the scale of society, these are the plans at present occurring to me." While he tries to improve his social status via marriage, his sister expressly denies to do the very thing in the previous chapter. A similar thing is done by Bella, who renounces social status and wealth in favour of love, although in a different way.

It is fairy-tale-like but not very sensible ;-)

"Was it strange that the wretched man should take this heavily to heart? Perhaps he had taken the boy to heart, first, through some long laborious years; perhaps through the same years he had found his drudgery lightened by communication with a brighter and more apprehensive spirit than his own; perhaps a family resemblance of face and voice between the boy and his sister, smote him hard in the gloom of his fallen state. For whichsoever reason, or for all, he drooped his devoted head when the boy was gone, and shrank together on the floor, and grovelled there, with the palms of his hands tight-clasping his hot temples, in unutterable misery, and unrelieved by a single tear."

The illustration in my book shows Bradley lying on the floor with a picture of Cain and Abel on the wall, by the way. Charley is also a character who deliberately chooses to work towards a marriage of convenience when he says that he might marry the schoolmistress: "I hope, before many years are out, to succeed the master in my present school, and the mistress being a single woman, though some years older than I am, I might even marry her. If it is any comfort to you to know what plans I may work out by keeping myself strictly respectable in the scale of society, these are the plans at present occurring to me." While he tries to improve his social status via marriage, his sister expressly denies to do the very thing in the previous chapter. A similar thing is done by Bella, who renounces social status and wealth in favour of love, although in a different way.

It is fairy-tale-like but not very sensible ;-)

Tristram wrote: "This division between the public and the private world, and the different spheres of the sexes, also comes out in Schiller's famous poem The Song of the Bell where one extract goes:

"The man must go out

In hostile life living,

Be working and striving"

Who can find a capable wife?

She is far more precious than jewels.

11

The heart of her husband trusts in her,

and he will not lack anything good.

12

She rewards him with good, not evil,

all the days of her life.

13

She selects wool and flax

and works with willing hands.

14

She is like the merchant ships,

bringing her food from far away.

15

She rises while it is still night

and provides food for her household

and portions for her female servants.

16

She evaluates a field and buys it;

she plants a vineyard with her earnings.

17

She draws on her strength

and reveals that her arms are strong.

18

She sees that her profits are good,

and her lamp never goes out at night.

19

She extends her hands to the spinning staff,

and her hands hold the spindle.

20

Her hands reach out to the poor,

and she extends her hands to the needy.

21

She is not afraid for her household when it snows,

for all in her household are doubly clothed.

22

She makes her own bed coverings;

her clothing is fine linen and purple.

23

Her husband is known at the city gates,

where he sits among the elders of the land.

24

She makes and sells linen garments;

she delivers belts to the merchants.

25

Strength and honor are her clothing,

and she can laugh at the time to come.

26

She opens her mouth with wisdom

and loving instruction is on her tongue.

27

She watches over the activities of her household

and is never idle.

28

Her sons rise up and call her blessed.

Her husband also praises her:

29

“Many women[s] are capable,

but you surpass them all!”

30

Charm is deceptive and beauty is fleeting,

but a woman who fears the Lord will be praised.

31

Give her the reward of her labor,

and let her works praise her at the city gates.

Proverbs 31

So there. I hope evaluating fields, planting vineyards, selling clothes to merchants and such isn't important to God because I've falling rather behind in any of these things. :-)

"The man must go out

In hostile life living,

Be working and striving"

Who can find a capable wife?

She is far more precious than jewels.

11

The heart of her husband trusts in her,

and he will not lack anything good.

12

She rewards him with good, not evil,

all the days of her life.

13

She selects wool and flax

and works with willing hands.

14

She is like the merchant ships,

bringing her food from far away.

15

She rises while it is still night

and provides food for her household

and portions for her female servants.

16

She evaluates a field and buys it;

she plants a vineyard with her earnings.

17

She draws on her strength

and reveals that her arms are strong.

18

She sees that her profits are good,

and her lamp never goes out at night.

19

She extends her hands to the spinning staff,

and her hands hold the spindle.

20

Her hands reach out to the poor,

and she extends her hands to the needy.

21

She is not afraid for her household when it snows,

for all in her household are doubly clothed.

22

She makes her own bed coverings;

her clothing is fine linen and purple.

23

Her husband is known at the city gates,

where he sits among the elders of the land.

24

She makes and sells linen garments;

she delivers belts to the merchants.

25

Strength and honor are her clothing,

and she can laugh at the time to come.

26

She opens her mouth with wisdom

and loving instruction is on her tongue.

27

She watches over the activities of her household

and is never idle.

28

Her sons rise up and call her blessed.

Her husband also praises her:

29

“Many women[s] are capable,

but you surpass them all!”

30

Charm is deceptive and beauty is fleeting,

but a woman who fears the Lord will be praised.

31

Give her the reward of her labor,

and let her works praise her at the city gates.

Proverbs 31

So there. I hope evaluating fields, planting vineyards, selling clothes to merchants and such isn't important to God because I've falling rather behind in any of these things. :-)

Tristram wrote: "I could not help feeling bemused by the description of homely bliss that Dickens is giving here, turning the capricious Bella into a homespun bore all of a sudden..."

I knew it. Grump.

Poor, poor Bella

I knew it. Grump.

Poor, poor Bella

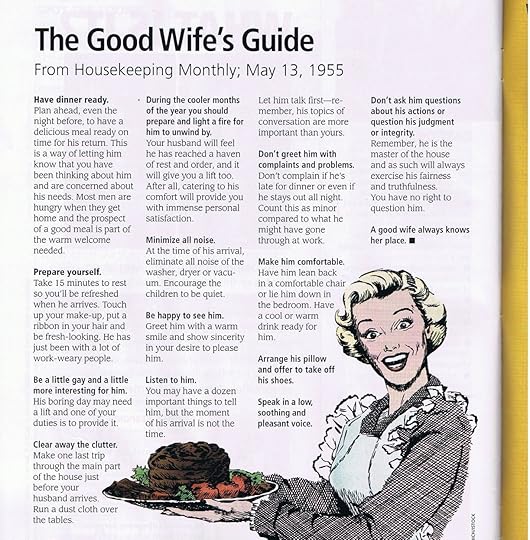

Mrs. Wilfer, Miss Lavinia, and Mr. Geo. Sampson

Chapter 5

Sol Eytinge

Household Edition 1870

Commentary:

Eytinge continues with his realisation of the story of Bella Wilfer, her younger sister, Lavinia, and their dictatorial mother in the last plate of his series, illustrating a scene of the fifth chapter of the fourth book, "Concerning the Mendicant's Bride." The publisher, however, has positioned the illustration so that it falls in the previous chapter, "A Runaway Match," in which John Rokesmith makes a rendezvous with Bella and her father at Greenwhich, and marries her at the picturesque eighteenth-century church there. As the reader encounters the illustration, Bella has just read a letter aloud to her father and new husband in which she briefly announces that she and Rokesmith have married; she has taken the interesting precaution of attempting to protect her long-suffering father from the wrath of her mother by giving her mother the impression that R. Wilfer knows nothing about the wedding ("Please tell darling Pa,"). We now await the moment in the text when in company with Bella's ex-beau, George Sampson, and her daughter Lavinia, the imperious Mrs. Wilfer (depicted as somewhat cadaverous of face by Eytinge) receives the correspondence and reacts negatively to the news it imparts. Curiously, the illustrator has not included the letter itself in the picture, which apparently deals with the following passage:

"Ma," interposed the young lady, "I must say I think it would be much better if you would keep to the point, and not hold forth about people's flying into people's faces, which is nothing more nor less than impossible nonsense."

"How!" exclaimed Mrs. Wilfer, knitting her dark brows.

"Just im-possible nonsense, Ma," returned Lavvy, "and George Sampson knows it is, as well as I do."

Assimilating poses and utterances in this scene with much earlier descriptions that Dickens has provided of these three characters, Eytinge renders Lavina Wilfer as a little vain, indolent, and self-centred, but not particularly upset by the news contained in the letter that her mother has just read aloud; nor does Dickens's characterizing her as "the Irrepressible" seem consistent with Eytinge's image of her. In the picture, Mrs. Wilfer is ugly to the point of being frightening; however, although she is as rigid, angular, and thin as Dickens describes her in the fourth chapter of Book One, Mrs. Wilfer is hardly "grimly heroic" and majestic in this final Eytinge illustration. Dickens does not describe George Sampson as specifically gnawing the head of his cane in this chapter; rather, Eytinge has given him the pose which Dickens describes him adopting in the ninth chapter of the first book: "He put the round head of his cane in his mouth, like a stopper, when he sat down. As if he felt himself full to the throat with affecting sentiments." Eytinge correctly communicates this minor character's mental vacuity. Finally, since Eytinge does not show the girls' father, R. Wilfer, in the picture, the illustrator is implying that we are regarding the three characters from his perspective.

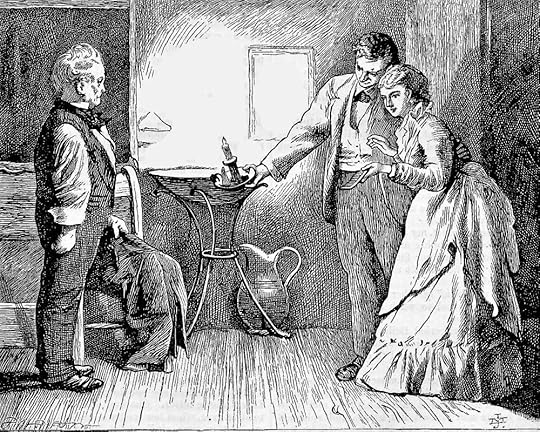

"Now, you are something like a genteel boy!"

Book 4 Chapter 5

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

Pa had his special chair and his special corner reserved for him on all occasions, and — without disparagement of his domestic joys — was far happier there, than anywhere. It was always pleasantly droll to see Pa and Bella together; but on this present evening her husband thought her more than usually fantastic with him.

"You are a very good little boy," said Bella, "to come unexpectedly, as soon as you could get out of school. And how have they used you at school to-day, you dear?"

"Well, my pet," replied the cherub, smiling and rubbing his hands as she sat him down in his chair, 'I attend two schools. There's the Mincing Lane establishment, and there's your mother's Academy. Which might you mean, my dear?"

"Both," said Bella.

"Both, eh? Why, to say the truth, both have taken a little out of me to-day, my dear, but that was to be expected. There's no royal road to learning; and what is life but learning!"

"And what do you do with yourself when you have got your learning by heart, you silly child?"

"Why then, my dear," said the cherub, after a little consideration, "I suppose I die."

"You are a very bad boy," retorted Bella, "to talk about dismal things and be out of spirits."

"My Bella," rejoined her father, "I am not out of spirits. I am as gay as a lark." Which his face confirmed.

"Then if you are sure and certain it's not you, I suppose it must be I," said Bella; 'so I won't do so any more. John dear, we must give this little fellow his supper, you know."

"Of course we must, my darling."

"He has been grubbing and grubbing at school," said Bella, looking at her father's hand and lightly slapping it, 'till he's not fit to be seen. O what a grubby child!"

"Indeed, my dear," said her father, "I was going to ask to be allowed to wash my hands, only you find me out so soon."

"Come here, sir!' cried Bella, taking him by the front of his coat, "come here and be washed directly. You are not to be trusted to do it for yourself. Come here, sir!"

The cherub, to his genial amusement, was accordingly conducted to a little washing-room, where Bella soaped his face and rubbed his face, and soaped his hands and rubbed his hands, and splashed him and rinsed him and towelled him, until he was as red as beet-root, even to his very ears: "Now you must be brushed and combed, sir," said Bella, busily. "Hold the light, John. Shut your eyes, sir, and let me take hold of your chin. Be good directly, and do as you are told!"

Her father being more than willing to obey, she dressed his hair in her most elaborate manner, brushing it out straight, parting it, winding it over her fingers, sticking it up on end, and constantly falling back on John to get a good look at the effect of it. Who always received her on his disengaged arm, and detained her, while the patient cherub stood waiting to be finished.

"There!' said Bella, when she had at last completed the final touches. "Now, you are something like a genteel boy! Put your jacket on, and come and have your supper."

Commentary:

Mahoney does not attempt to describe the wedding dinner since the subject of the marriage of John (who has yet to reveal his true identity as John Harmon) and Bella had been dealt with (albeit in a lacklustre fashion) by Marcus Stone ten years earlier in The Wedding Dinner at Greenwich (August 1865). The illustration presents the Rokesmiths' early married life in their cottage on Blackheath as idyllic. In their little house Bella's father is an honoured guest, with whom Bella continues her playful banter as if she were R. W.'s mother rather than his daughter. Lurking behind the domestic bliss is the question of how Bella will respond when she learns that her husband is the wealthy John Harmon rather than the "mendicant" John Rokesmith. There is no comparable scene to the domestic bliss of the Rokesmiths in the original serial sequence, which jumps from the clandestine wedding to the romantic plot involving Eugene Wrayburn and Lizzie Hexam, The Parting by the River (Chapter Six, "A Cry for Help," in the September 1865 installment).

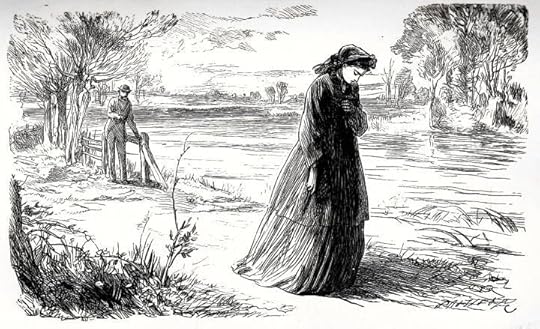

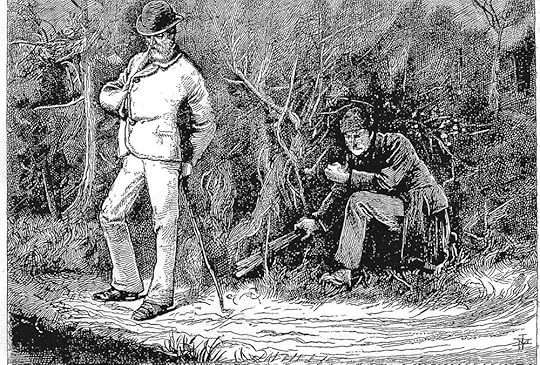

The Parting by the River

Book 4 Chapter 6

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

One of the more effective illustrations in the second half of Marcus Stone's narrative-pictorial sequence for the serialisation of Our Mutual Friend from May 1864 through November 1865 is the thirty-fourth, "The Parting by the River," in which Lizzie Hexam reluctantly quits Eugene Wrayburn's company on the banks of the upper Thames, near the paper mill where she works. The illustrator foregrounds a highly dignified Lizzie and her feeling of deep regret in a posture suggestive of mourning for a relationship that a class-conscious society militates against. In the background, left, Eugene Wrayburn contemplates her figure, complementing the text, which foregrounds his consciousness and his honest self-appraisal. Thus, the illustrator captures the external, theatrical aspects of the parting while the writer presents interior analysis. The passage realised in the first September 1865 illustration is accordingly this:

He held her, almost as if she were sanctified to him by death, and kissed her, once, almost as he might have kissed the dead.

'I promised that I would not accompany you, nor follow you. Shall I keep you in view? You have been agitated, and it's growing dark.'

'I am used to be out alone at this hour, and I entreat you not to do so.'

'I promise. I can bring myself to promise nothing more tonight, Lizzie, except that I will try what I can do.'

'There is but one means, Mr. Wrayburn, of sparing yourself and of sparing me, every way. Leave this neighbourhood to-morrow morning.'

'I will try.'

As he spoke the words in a grave voice, she put her hand in his, removed it, and went away by the river-side.

'Now, could Mortimer believe this?' murmured Eugene, still remaining, after a while, where she had left him. 'Can I even believe it myself?'

He referred to the circumstance that there were tears upon his hand, as he stood covering his eyes. 'A most ridiculous position this, to be found out in!' was his next thought. And his next struck its root in a little rising resentment against the cause of the tears.

Symbolically, a stile or wooden fence by the river bank terminates at the figure of Eugene Wrayburn, who has reached a crucial point in his life as he must decide whether to pursue Lizzie against her better judgment and his, or yield to the barriers presented by the class system and abandon any hope of personal fulfillment with her. The skillfully drawn vegetation in the lower left and the artist's rendering of the natural backdrop complement the interior and psychological aspects of the scene, tacitly commenting on the artificiality of the social code that requires the lovers to part. The waters of the Thames like their conflicting feelings are full, nearly reaching the banks on either side, and there is little evidence of civilization in the sweeping aerial perspective. Although the face is definitely that of the young woman depicted in the first illustration "The Bird of Prey" and the thirteenth, "The Garden on the Roof", Lizzie's attire is now that of a respectable middle-class woman, and she looks inward here in contrast to her previous poses, holding her left hand over her heart as her right droops despondently towards the ground, her body casting a shadow forward, as if implying what her future will be without the love and companionship of this strange, cynical gentleman capable of such passion for her. The romantic setting and the strong feelings of the characters implied by Lizzie's pose and Eugene' s legalistic monologue or "voice-over" underscore the monumentality of the decision that the witty, cavalier attorney must now make.

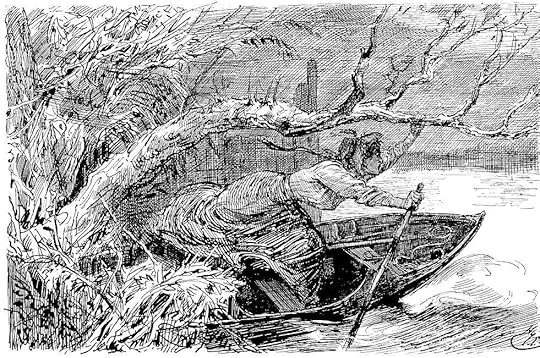

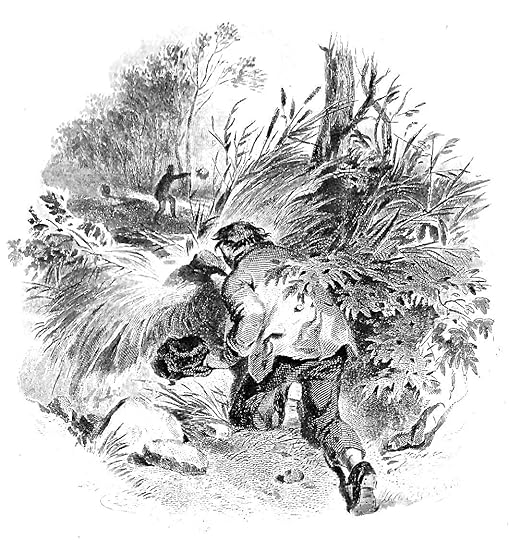

Lizzie Hexam to the rescue

Book 4 Chapter 6

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

"It was thought, fervently thought, but not for a moment did the prayer check her. She was away before it welled up in her mind, away, swift and true, yet steady above all — for without steadiness it could never be done — to the landing-place under the willow-tree, where she also had seen the boat lying moored among the stakes.

A sure touch of her old practised hand, a sure step of her old practised foot, a sure light balance of her body, and she was in the boat. A quick glance of her practised eye showed her, even through the deep dark shadow, the sculls in a rack against the red-brick garden-wall. Another moment, and she had cast off (taking the line with her), and the boat had shot out into the moonlight, and she was rowing down the stream as never other woman rowed on English water.

Intently over her shoulder, without slackening speed, she looked ahead for the driving face. She passed the scene of the struggle — yonder it was, on her left, well over the boat's stern — she passed on her right, the end of the village street, a hilly street that almost dipped into the river; its sounds were growing faint again, and she slackened; looking as the boat drove, everywhere, everywhere, for the floating face.

She merely kept the boat before the stream now, and rested on her oars, knowing well that if the face were not soon visible, it had gone down, and she would overshoot it. An untrained sight would never have seen by the moonlight what she saw at the length of a few strokes astern. She saw the drowning figure rise to the surface, slightly struggle, and as if by instinct turn over on its back to float. Just so had she first dimly seen the face which she now dimly saw again.

Firm of look and firm of purpose, she intently watched its coming on, until it was very near; then, with a touch unshipped her sculls, and crept aft in the boat, between kneeling and crouching. Once, she let the body evade her, not being sure of her grasp. Twice, and she had seized it by its bloody hair."

Commentary:

In "A Cry for Help," the daughter of Thames waterman Gaffer Hexam turns her practiced skill with oars and skiff to good account as she comes to the rescue of her admirer, Eugene Wrayburn, who has just been assaulted by the envious and mentally unstable Bradley Headstone. Furniss's vigorous, impressionistic style is well suited to this dynamic scene in which the Dickensian heroine snatches her lover (whom she just rejected at the river-bank) from drowning near Plashwater Weir. It was a sign of the times that in the year that the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910), illustrated by Harry Furniss, was published, suffragette spokesperson Emily Davies wrote Thoughts on Some Questions Relating to Women and in the House of Commons a bill was introduced to give vote rights to single and widowed females of a household, an initiative that would have granted young women such as Lizzie Hexam the right to vote.

Whereas the other nineteenth-century illustrators focused on the romantic aspect of Lizzie's parting from Eugene (as in Marcus Stone's The Parting by the River, Part 17, September 1865) or the impending violence of the scene in the Household Edition, working at the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, Harry Furniss dares to realize an atypical aspect of the story, as one of the romantic heroines, the emotionally-conflicted girl of the working class uses her workaday skills learned from her father to rescue the privileged young attorney. Whereas F. O. C. Darley in the fourth American "Household" Edition volume of 1866 had focused in the frontispiece on Rogue Riderhood's surveillance of Headstone as he attempts to destroy the evidence of his involvement in what he believes to be the murder of the young lawyer in On the Track, the crime-and-detection aspect of the novel, Furniss has seized upon one of the most suspenseful sequences in the final movement of the story which reverses the reader's conventional expectations about the hero's rescuing the heroine, an expectation reinforced by the new medium of motion pictures in an era when women were demanding political and social emancipation — and recognition of their potentialities beyond the hearth and home. Although Dickens's novel appeared just a decade after Coventry Patmore's idealization of the woman's domestic function, The Angel in the House (1854-55), Lizzie is in many ways a much more complex, multi-faceted figure than Dickens's previous heroines — indeed, she strikes us today as the most modern, as Furniss points out by his selection of this scene of the dynamic Lizzie fearlessly acting in the male domain.

Although series editor J. A. Hammerton describes Lizzie in patriarchal terms in "Characters in the Story" — she appears a total of four times in twenty-eight Furniss illustrations, and occupies a prominent position (upper right) in the ornamental title-page Characters in the Story. She is one of two focal characters in the frontispiece, "Keep her out, Lizzie," and makes two solo appearances, in Lizzie Hexam's Vigil and Lizzie Hexam to the Rescue, in a narrative-pictorial sequence that involves only a very few individual studies other than Lizzie: Silas Wegg on his way to the Bower, and Bella's Baby. Thus, in a novel in which male characters predominate, Furniss accords a special prominence to Lizzie, who in so many ways violates the norms of the Victorian heroine, but by her courage, strength of character, and intelligence is worthy of development and concludes the story by crossing the class barrier. Furniss uses her as a foil to the more conventional female protagonist, Bella Wilfer, who is shown as feted, beautifully dressed, and mingling with upper-middle class society. Since chance plays a significant role in Lizzie's rescuing Wrayburn in that it is mere coincidence that she remembers seeing a boat at a convenient distance from the scene of the assault, Furniss sees her as a force, an agent of Providence.

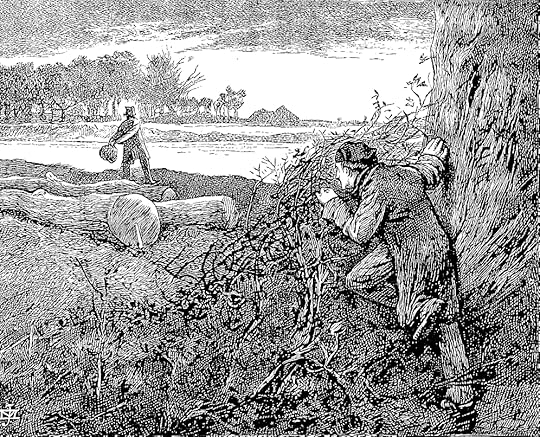

He had sauntered far enough. Before returning to retrace his steps, he stopped upon the margin to look down at the reflected night

Book 4 Chapter 6

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

"A landing-place overshadowed by a willow, and a pleasure-boat lying moored there among some stakes, caught his eye as he passed along. The spot was in such dark shadow, that he paused to make out what was there, and then passed on again.

The rippling of the river seemed to cause a correspondent stir in his uneasy reflections. He would have laid them asleep if he could, but they were in movement, like the stream, and all tending one way with a strong current. As the ripple under the moon broke unexpectedly now and then, and palely flashed in a new shape and with a new sound, so parts of his thoughts started, unbidden, from the rest, and revealed their wickedness. "Out of the question to marry her," said Eugene, "and out of the question to leave her. The crisis!"

He had sauntered far enough. Before turning to retrace his steps, he stopped upon the margin, to look down at the reflected night. In an instant, with a dreadful crash, the reflected night turned crooked, flames shot jaggedly across the air, and the moon and stars came bursting from the sky.

Was he struck by lightning? With some incoherent half-formed thought to that effect, he turned under the blows that were blinding him and mashing his life, and closed with a murderer, whom he caught by a red neckerchief — unless the raining down of his own blood gave it that hue.

Eugene was light, active, and expert; but his arms were broken, or he was paralysed, and could do no more than hang on to the man, with his head swung back, so that he could see nothing but the heaving sky. After dragging at the assailant, he fell on the bank with him, and then there was another great crash, and then a splash, and all was done."

Commentary:

Mahoney does not attempt to describe the assault itself, for doing so would render the wrestling scene on the lock, Mahoney's penultimate illustration, a repetition of this earlier violent episode. Nor does he merely ignore it, as Dickens's own serial illustrator, Marcus Stone did in the monthly number of September 1865, in which he prepares the reader for the setting and circumstances of the assault but does not forewarn the reader that Headstone's shadowing Wrayburn will result in attempted murder. The other approach by the third significant illustrator of the text, Harry Furniss's, is as successful as Mahoney's at generating suspense, and is equally dramatic. Again the illustrator realizes a significant moment in the chapter "A Cry for Help" without giving away the fact that the young attorney will survive the attack. The Mahoney plate is not without its technical difficulties, however, since the illustrator is showing Headstone lying in wait in the growing darkness and Wrayburn oblivious to his adversary's presence without this being a dark plate, so that, at first glance, a viewer cannot understand why the lawyer is not aware of the crouching school-master immediately behind him. There is no comparable scene to this, anticipating the assault, in the original serial sequence, which jumps from the romantic scene involving Eugene Wrayburn and Lizzie Hexam, The Parting by the River (Chapter Six, "A Cry for Help") to Headstone's anguish at what he has done and what he has become, Better to be Abel than Cain River in the chapter of the same name (Chapter Seven, still within the September 1865 installment) — a psychological interpretation that Dickens himself probably endorsed.

Whereas F. O. C. Darley in the fourth American "Household" Edition volume of 1866 had focused in the frontispiece on Rogue Riderhood's surveillance of Headstone as he attempts to destroy the evidence of his involvement in what he believes to be the murder of the young lawyer in On the Track, the crime-and-detection aspect of the novel, Mahoney and Furniss seized upon one of the most suspenseful sequences in the final movement of the story. Furniss's illustration Lizzie Hexam to the Rescue shifts the emphasis significantly from the rivalry between the male admirers of Lizzie towards an appreciation of her pivotal role in Eugene's escaping drowning and being recalled to life.

In the Mahoney illustration, which would have influenced how so many late Victorian readers would have processed the incidents in what had originally been the September 1865 monthly number, respectably clad Eugene with his bowler-hat is engaged in observing the surface of the river beneath him while the malevolent Headstone, clad in working-class attire, steels himself, grabbing a branch with his right hand. The object may be tree-branch, in which case the assault is a spur-of-the-moment decision; it may also be something that the assailant has brought with him, suggesting that the crime is entirely pre-meditated. In the text, Eugene encounters a man carrying something upon his shoulder — "which might have been a broken oar, or spar, or a bar" — but Dickens does not specifically identify this "man" as Headstone, and does not even describe his clothing. Nor does Dickens describe how Headstone prepares for the attack, so that the part of the illustration dealing with the assailant is pure speculation on Mahoney's part. In coloration Headstone in the wood-engraving is one with the vegetation on the river-bank, and therefore Mahoney would seem to be suggesting that Headstone at this point is at one with the antagonistic natural forces that oppose humanity, or perhaps an exemplar of the Darwinian ethos of "Survival of the Fittest." By this point in the narrative in the letterpress surrounding the illustration in the Chapman and Hall edition, Headstone has already attempted to destroy the disguise that would implicate him in what he believes is the murder of his romantic rival, and is now resting in the lock-keeper's hut.

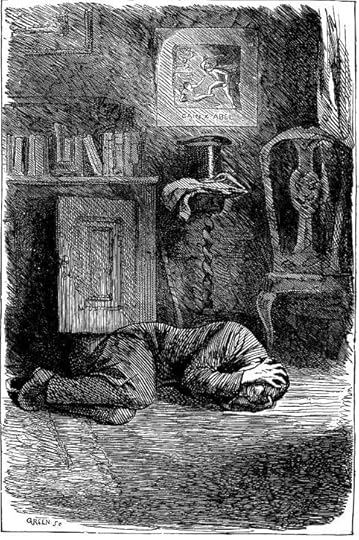

Better to be Abel than Cain

Book 4 Chapter 7

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration for Book 4, "A Turning," Chapter 7, "Better To Be Abel Than Cain," appeared in the September, 1865, installment. The precise moment captured in the illustration is easily determined since Headstone grovels on the floor after Charley Hexam's chastising for his selfishness in attacking Wrayburn, a criminal act that may well blight Charley's career as a school-master.

"When he had dried his eyes and heaved a sob over his injuries, he began moving towards the door.

'However, I have made up my mind that I will become respectable in the scale of society, and that I will not be dragged down by others. I have done with my sister as well as with you. Since she cares so little for me as to care nothing for undermining my respectability, she shall go her way and I will go mine. My prospects are very good, and I mean to follow them alone. Mr Headstone, I don't say what you have got upon your conscience, for I don't know. Whatever lies upon it, I hope you will see the justice of keeping wide and clear of me, and will find a consolation in completely exonerating all but yourself. I hope, before many years are out, to succeed the master in my present school, and the mistress being a single woman, though some years older than I am, I might even marry her. If it is any comfort to you to know what plans I may work out by keeping myself strictly respectable in the scale of society, these are the plans at present occurring to me. In conclusion, if you feel a sense of having injured me, and a desire to make some small reparation, I hope you will think how respectable you might have been yourself and will contemplate your blighted existence.'

Was it strange that the wretched man should take this heavily to heart? Perhaps he had taken the boy to heart, first, through some long laborious years; perhaps through the same years he had found his drudgery lightened by communication with a brighter and more apprehensive spirit than his own; perhaps a family resemblance of face and voice between the boy and his sister, smote him hard in the gloom of his fallen state. For whichsoever reason, or for all, he drooped his devoted head when the boy was gone, and shrank together on the floor, and grovelled there, with the palms of his hands tight-clasping his hot temples, in unutterable misery, and unrelieved by a single tear."

Marcus Stone has adopted some tricks of realization customary in Phiz's illustrations of Dickens's novels, namely the chair whose central back support resembles a grinning mask and the embedded biblical scene on the wall, above Bradley Headstone's respectable bourgeois top hat. The barley cane twist table-leg links the illustration of the first murder with the murderer — in fact, the table-leg creates the illusion of the picture and the hat drilling down into the prostrate school-master, whose impetuosity and jealousy — in short, his utter inability to control his emotions — have cost him his livelihood, his social station, his friendship with the equally self-centered Charley, and (if apprehended for the crime) his life. His pose bespeaks utter misery, as he shields his ears, as if to block out the recollection of Charley's stinging rebuke. The image of Headstone on the floor is Rodinesque in that it remains in the mind's eye and reveals so much about the psychological state of the subject. The chapter title prepares the reader for this narrative moment in the two media as, it implies, Headstone so deeply regrets the consequences of his rash action that he wishes he were dead rather than having to confront what he has done: "Better to be Abel [the victim] rather than Cain [the assailant].

On The Track

Book 4 Chapter 7

Felix O. C. Darley

Household Edition 1866

Text Illustrated:

"By George and the Draggin!" cried Riderhood, "if he ain't a going to bathe!"

"He had passed back, on and among the trunks of trees again, and has passed on to the water-side and had begun undressing on the grass. For a moment it had a suspicious look of suicide, arranged to counterfeit accident. "But you wouldn't have fetched a bundle under your arm, from among that timber, if such was your game!" said Riderhood. Nevertheless it was a relief to him when the bather after a plunge and a few strokes came out. "For I shouldn't," he said in a feeling manner, "have liked to lose you till I had made more money out of you neither."

Prone in another ditch (he had changed his ditch as his man had changed his position), and holding apart so small a patch of the hedge that the sharpest eyes could not have detected him, Rogue Riderhood watched the bather dressing. And now gradually came the wonder that he stood up, completely clothed, another man, and not the Bargeman.

"Aha!" said Riderhood. "Much as you was dressed that night. I see. You're a taking me with you, now. You're deep. But I knows a deeper."

When the bather had finished dressing, he kneeled on the grass, doing something with his hands, and again stood up with his bundle under his arm. Looking all around him with great attention, he then went to the river's edge, and flung it in as far, and yet as lightly as he could. It was not until he was so decidedly upon his way again as to be beyond a bend of the river and for the time out of view, that Riderhood scrambled from the ditch.

"Now," was his debate with himself, "shall I foller you on, or shall I let you loose for this once, and go a fishing?" The debate continuing, he followed, as a precautionary measure in any case, and got him again in sight. "If I was to let you loose this once," said Riderhood then, still following, "I could make you come to me agin, or I could find you out in one way or another. If I wasn't to go a fishing, others might. — I'll let you loose this once, and go a fishing!" With that, he suddenly dropped the pursuit and turned."

Commentary:

Commentary: Bradley Headstone and Rogue Riderhood