The Old Curiosity Club discussion

The Pickwick Papers

>

PP. Chapters 38 - 40

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 40

In chapter 40 we are faced with a much different tone as Pickwick returns to London and finds himself in the clutches of the legal system rather than in the congenial company of his friends.

On the third day after their arrival Sam observes a rather distinctive vehicle arrive outside the George and Vulture and out of this vehicle emerges an equally interesting man with black hair, much over-sized jewelry, and a bright silk handkerchief “with which he whisked a speck or two of dust from his boots.” This gentleman is Mr Nanby. Sam also notices a rather shabby-looking man who shadowed the man with black hair. Nanby serves Pickwick with a warrant in the case of Bardell. Sam, ever faithful, tries to protect Pickwick and knocks off Namby’s hat. Sam indicates that he will protect Pickwick and prepares to fight Namby, only to be told by Pickwick that “if you say another word, or offer the slightest interference” he will be dismissed.

Sam “flatly and positively refuses” to back down. Here we witness at least two interesting character events. First, as we have seen earlier in the novel, Pickwick does have a temper which surfaces on many occasions. Second, Sam is a completely loyal person, a man who would do anything for his master.

Thoughts

Dickens likes to create contrast between his chapters. Chapter 39 was one of broad humour. In this chapter, we are put in a much more somber setting.

To what extent do you think this style format is a conscious decision of Dickens?

How effective do you find this stylistic format?

Not only do we often encounter a stylistic format that finds its opposite in the preceding chapter in The Pickwick Papers, but we also find that the twin chapters share a similar topic. In this case the foibles of love in chapter 39 are in stark contrast with a court case to establish or refute the love between two individuals. The common footprint is marital relationships. We have discussed earlier what form of novel The Pickwick Papers most closely resembles. Does this style help or hinder us to classify the fundamental structure of the novel?

Pickwick is taken by coach to Namby’s place of business whose front parlour smelt of “fresh sand and stale tobacco.” In this room are three other men who have been collected by Nanby and are now awaiting the next step in the legal process. Pickwick listens to the conversation of these men and is “a little disgusted with its dialogue.” Pickwick is able to get himself into a private room. Mr Parker arrives and urges Pickwick to pay the fine. Pickwick, on the other hand, is determined to see his day in court. Before Pickwick is transferred, however, Pickwick wants to finish his breakfast. It appears that even the reality of being locked up in jail does not dampen Pickwick’s hunger. Parker cannot convince Pickwick to free himself; indeed, Pickwick is now in a state of mind which Dickens describes as “unmoved patience.”

What follows are more character sketches of the working and underclasses of society. Further insight into how the court is set up, what those awaiting trial think and say, how “professional jurists” intermingle within the system, and how the judge’s chambers is a place of confused jockeying. Pickwick is our eyes in this chapter. He is a recorder of sights, sounds, and emotions. Perhaps the teeming confusion of the law courts comes from Dickens’s own experiences as a court reporter.

Thoughts

I really enjoyed Sam’s pronunciation of habeas corpus as “have-his-carcasses.” Did you enjoy how Dickens used this mispronunciation to suggest the function of the entire legal system?

Pickwick ends up in the Fleet Prison. For some reason the initial description of the Fleet reminded me of both Pickwick’s earlier encounters with gates and walls. First, at the red-brick boarding house, and more recently the midnight rendezvous with Arabella. Now that I think about it, Pickwick seems prone to getting trapped, held captive or in prisoned in many shapes and forms from wheelbarrows to the top of carriages to hiding behind bedroom curtains. Can you think of any other prison or prison-like state that Pickwick has been part of so far in the novel?

Once in the Fleet, Pickwick undergoes a “sitting for [a] portrait” which seems to be what we would call today a mug shot. I was, of course, very happy to note there is a bird-cage in the prison which Sam points out as an example of “Veels vithin veels, a prison in a prison.”

We have noted throughout our reading the number of interpolated stories that occur in the novel, the many forms that love can take between individuals, and the pairing of characters such as Sam and Pickwick and Jingle and Job. We are now far enough into the novel to think about motifs and themes that seem to exist. Can you think of ideas and concepts that are presenting themselves in the novel?

As we find ourselves reading deeper into the novel I have noticed that there is a definite change in the overall mood. While the early chapters contained interpolated tales that were full of grief, pain, revenge, and death, they were surrounded by a much lighter framework of characters, events, and chapters that have a lighter tone, a touch of romance, and a delight in both the characters’ adventures and their misadventures. Now, however, a darker, brooding tone has entered the novel. There is a seriousness, and ever-increasing acknowledgement that England is a place that is not ideal, perfect, or noble. Rather, it is a place of unhappiness, lost opportunity, and discomfort. Gone are the interpolated fictitious tales of misery. Now, the bruising events of real life are present in the characters’ lives. To what extent do you agree with me?

If you do agree with me, how would you characterize your impressions?

In chapter 40 we are faced with a much different tone as Pickwick returns to London and finds himself in the clutches of the legal system rather than in the congenial company of his friends.

On the third day after their arrival Sam observes a rather distinctive vehicle arrive outside the George and Vulture and out of this vehicle emerges an equally interesting man with black hair, much over-sized jewelry, and a bright silk handkerchief “with which he whisked a speck or two of dust from his boots.” This gentleman is Mr Nanby. Sam also notices a rather shabby-looking man who shadowed the man with black hair. Nanby serves Pickwick with a warrant in the case of Bardell. Sam, ever faithful, tries to protect Pickwick and knocks off Namby’s hat. Sam indicates that he will protect Pickwick and prepares to fight Namby, only to be told by Pickwick that “if you say another word, or offer the slightest interference” he will be dismissed.

Sam “flatly and positively refuses” to back down. Here we witness at least two interesting character events. First, as we have seen earlier in the novel, Pickwick does have a temper which surfaces on many occasions. Second, Sam is a completely loyal person, a man who would do anything for his master.

Thoughts

Dickens likes to create contrast between his chapters. Chapter 39 was one of broad humour. In this chapter, we are put in a much more somber setting.

To what extent do you think this style format is a conscious decision of Dickens?

How effective do you find this stylistic format?

Not only do we often encounter a stylistic format that finds its opposite in the preceding chapter in The Pickwick Papers, but we also find that the twin chapters share a similar topic. In this case the foibles of love in chapter 39 are in stark contrast with a court case to establish or refute the love between two individuals. The common footprint is marital relationships. We have discussed earlier what form of novel The Pickwick Papers most closely resembles. Does this style help or hinder us to classify the fundamental structure of the novel?

Pickwick is taken by coach to Namby’s place of business whose front parlour smelt of “fresh sand and stale tobacco.” In this room are three other men who have been collected by Nanby and are now awaiting the next step in the legal process. Pickwick listens to the conversation of these men and is “a little disgusted with its dialogue.” Pickwick is able to get himself into a private room. Mr Parker arrives and urges Pickwick to pay the fine. Pickwick, on the other hand, is determined to see his day in court. Before Pickwick is transferred, however, Pickwick wants to finish his breakfast. It appears that even the reality of being locked up in jail does not dampen Pickwick’s hunger. Parker cannot convince Pickwick to free himself; indeed, Pickwick is now in a state of mind which Dickens describes as “unmoved patience.”

What follows are more character sketches of the working and underclasses of society. Further insight into how the court is set up, what those awaiting trial think and say, how “professional jurists” intermingle within the system, and how the judge’s chambers is a place of confused jockeying. Pickwick is our eyes in this chapter. He is a recorder of sights, sounds, and emotions. Perhaps the teeming confusion of the law courts comes from Dickens’s own experiences as a court reporter.

Thoughts

I really enjoyed Sam’s pronunciation of habeas corpus as “have-his-carcasses.” Did you enjoy how Dickens used this mispronunciation to suggest the function of the entire legal system?

Pickwick ends up in the Fleet Prison. For some reason the initial description of the Fleet reminded me of both Pickwick’s earlier encounters with gates and walls. First, at the red-brick boarding house, and more recently the midnight rendezvous with Arabella. Now that I think about it, Pickwick seems prone to getting trapped, held captive or in prisoned in many shapes and forms from wheelbarrows to the top of carriages to hiding behind bedroom curtains. Can you think of any other prison or prison-like state that Pickwick has been part of so far in the novel?

Once in the Fleet, Pickwick undergoes a “sitting for [a] portrait” which seems to be what we would call today a mug shot. I was, of course, very happy to note there is a bird-cage in the prison which Sam points out as an example of “Veels vithin veels, a prison in a prison.”

We have noted throughout our reading the number of interpolated stories that occur in the novel, the many forms that love can take between individuals, and the pairing of characters such as Sam and Pickwick and Jingle and Job. We are now far enough into the novel to think about motifs and themes that seem to exist. Can you think of ideas and concepts that are presenting themselves in the novel?

As we find ourselves reading deeper into the novel I have noticed that there is a definite change in the overall mood. While the early chapters contained interpolated tales that were full of grief, pain, revenge, and death, they were surrounded by a much lighter framework of characters, events, and chapters that have a lighter tone, a touch of romance, and a delight in both the characters’ adventures and their misadventures. Now, however, a darker, brooding tone has entered the novel. There is a seriousness, and ever-increasing acknowledgement that England is a place that is not ideal, perfect, or noble. Rather, it is a place of unhappiness, lost opportunity, and discomfort. Gone are the interpolated fictitious tales of misery. Now, the bruising events of real life are present in the characters’ lives. To what extent do you agree with me?

If you do agree with me, how would you characterize your impressions?

Peter wrote: "Let’s have a mid-novel vote. What has been you favourite humorous scene to this point in the novel?..."

Peter wrote: "Let’s have a mid-novel vote. What has been you favourite humorous scene to this point in the novel?..."I hate "favorite" questions! It's much too hard. It's not playing fair, but I have to say that the overall feeling of goodwill and amusement I get from the novel as a whole far outweighs any one specific incident. As you pointed out, our anticipation, based on our knowledge of previous misadventures, is almost as fun as the events themselves.

Peter wrote: "What exactly makes Dickens characters’ attachments so dissimilar to a Jane Austen or a Bronte love attachment?..."

Peter wrote: "What exactly makes Dickens characters’ attachments so dissimilar to a Jane Austen or a Bronte love attachment?..."Julie rightly pointed out that Austen is fun, but I don't think one can really say her romances could be described that way. Her social commentary can be a hoot, but her characters' romantic relationships are fraught with angst. The course of true love may not always run smooth with the Pickwick Club, but it's a fun ride, nonetheless.

As for the Brontës, I've read three of their books: one I liked, one I could take or leave, and one I hated. But I don't remember a moment of light-hearted frivolity in any of them.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Let’s have a mid-novel vote. What has been you favourite humorous scene to this point in the novel?..."

I hate "favorite" questions! It's much too hard. It's not playing fair, but I ..."

Hi Mary Lou

Yes. The “favourite” question is a minefield. For me, I find such questions concerning music especially difficult because my mood at the moment often is the foundation for my opinion. As for Dickens, well, I’m sure with the Curiosities (and pre-Curiosities) I’ve said BH, GE, DC, and TTC are my favourite Dickens. I think my only consistant answer would be that D&S is Dickens’s most underrated novel.

As for PP and my personal favourite incident I’ll remain quiet for now. When we look back at the entire novel it will be interesting to see what people think. Also, I find that as we move further into the novel more and more shade falls upon our Pickwickian landscape. I confess that I am interested in how many of us will find their favourite chapter in the second half of the novel. I am planning to ask the question again just for fun. Time will tell.

I well remember when I was teaching I would be asked the same question about favourites by some of my students. My answer was always “Baskin and Robbins.” To their puzzled expression I would say there are so many flavours to select from that I never choose the same one twice.

Although the truth is I do love orange sherbet. :-))

I hate "favorite" questions! It's much too hard. It's not playing fair, but I ..."

Hi Mary Lou

Yes. The “favourite” question is a minefield. For me, I find such questions concerning music especially difficult because my mood at the moment often is the foundation for my opinion. As for Dickens, well, I’m sure with the Curiosities (and pre-Curiosities) I’ve said BH, GE, DC, and TTC are my favourite Dickens. I think my only consistant answer would be that D&S is Dickens’s most underrated novel.

As for PP and my personal favourite incident I’ll remain quiet for now. When we look back at the entire novel it will be interesting to see what people think. Also, I find that as we move further into the novel more and more shade falls upon our Pickwickian landscape. I confess that I am interested in how many of us will find their favourite chapter in the second half of the novel. I am planning to ask the question again just for fun. Time will tell.

I well remember when I was teaching I would be asked the same question about favourites by some of my students. My answer was always “Baskin and Robbins.” To their puzzled expression I would say there are so many flavours to select from that I never choose the same one twice.

Although the truth is I do love orange sherbet. :-))

Peter wrote: "To what extent could it be argued that The Pickwick Papers is a novel without a clear protagonist or hero?..."

Peter wrote: "To what extent could it be argued that The Pickwick Papers is a novel without a clear protagonist or hero?..."Pickwick is like Seinfeld - it's a sitcom with a great ensemble cast. Jerry and Pickwick are the central characters, but without their friends, and all the wonderful people in their orbit, it wouldn't be much of a show (or story).

Peter wrote: "Chapter 38

Peter wrote: "Chapter 38...our good friend Mr Winkle is stepping out of the Frying-pan and walking “gently and comfortably into the Fire.” Have..."

Help me out here.... Mary and Sam meet and concoct a way for Mr. Winkle (have you ever googled "Mr. Winkle"? Do it now... I'll wait...) to meet Arabella. Mr. Pickwick comes along as something of a chaperone. Then we have this passage:

'Is Miss Allen in the garden yet, Mary?' inquired Mr. Winkle,

much agitated.

'I don't know, sir,' replied the pretty housemaid. 'The best

thing to be done, sir, will be for Mr. Weller to give you a hoist up

into the tree, and perhaps Mr. Pickwick will have the goodness

to see that nobody comes up the lane, while I watch at the other

end of the garden. Goodness gracious, what's that?'...

The scene proceeds, and we hear nothing more from Mary.

How is it possible that Mary doesn't show a bit of awkwardness or coquettishness (if that's even a word), or give any hint that she was the recipient of a Valentine from Mr. Pickwick? Is this just an oversight on Dickens' part? Am I missing something? I've just been waiting for that delicious moment to come where Sam's using Pickwick's name on the Valentine would come to a head, and thought it would surely happen here, but... nothing.

Peter wrote: "... Pickwick seems prone to getting trapped, held captive or in prisoned in many shapes and forms from wheelbarrows to the top of carriages to hiding behind bedroom curtains. Can you think of any other prison or prison-like state that Pickwick has been part of so far in the novel?

Peter wrote: "... Pickwick seems prone to getting trapped, held captive or in prisoned in many shapes and forms from wheelbarrows to the top of carriages to hiding behind bedroom curtains. Can you think of any other prison or prison-like state that Pickwick has been part of so far in the novel?It's undeniable that this is a strong theme in the novel, and yet it doesn't (so far, at least) feel oppressive or symbolic to me as it would have in TTC or BH, for example. I could be missing something, or perhaps the feeling of being locked up will become more significant in the next few chapters. Or is it just possible that Dickens was still a comparatively immature author, and was either unconsciously weaving this theme though the novel, or doing it purposely, but without any real metaphorical meaning? I suppose we'll have to wait and see.

Peter wrote: I was, of course, very happy to note there is a bird-cage in the prison which Sam points out as an example of “Veels vithin veels, a prison in a prison.” ..."

I was, too, Peter. I thought of you immediately when I read that passage. :-) I wonder if any of Kim's artistic discoveries will include the birdcage in the prison....

Mary Lou,

I like the similarity you pointed out between PP and Seinfeld because in both cases you have a set of supporting characters and even one-time characters that make for a lot of the charm of the whole thing. What would Jerry be without Newman? Or Uncle Leo? (Although, my favourite minor character is clearly George's father.) And let's not forget, in both series there is a lawsuit, and if PP had been even more like Seinfeld, we would surely have had the lawyers dig out the Valentine card signed "lovesick-Pickwick". As matters stand, however, Dickens seems to have dropped that plot element completely, which is sad.

As to Jane Austen's and Dickens's ways of treating love relationships, I must confess that I have never got any enjoyment out of Ms. Austen's novels. But, to use another Seinfeld phrase, I'd say to Ms. Austen, "It's not you, it's me." I even tired ahem tried another of her novels lately, Northanger Abbey, only to find that it still did not work with me at all.

As to whom I like better, the two medical men or Job and Jingle, I'd say that I could imagine spending a jolly night with Allen and Sawyer but would probably try my influence to make Allen treat his sister less like a tyrant.

I like the similarity you pointed out between PP and Seinfeld because in both cases you have a set of supporting characters and even one-time characters that make for a lot of the charm of the whole thing. What would Jerry be without Newman? Or Uncle Leo? (Although, my favourite minor character is clearly George's father.) And let's not forget, in both series there is a lawsuit, and if PP had been even more like Seinfeld, we would surely have had the lawyers dig out the Valentine card signed "lovesick-Pickwick". As matters stand, however, Dickens seems to have dropped that plot element completely, which is sad.

As to Jane Austen's and Dickens's ways of treating love relationships, I must confess that I have never got any enjoyment out of Ms. Austen's novels. But, to use another Seinfeld phrase, I'd say to Ms. Austen, "It's not you, it's me." I even tired ahem tried another of her novels lately, Northanger Abbey, only to find that it still did not work with me at all.

As to whom I like better, the two medical men or Job and Jingle, I'd say that I could imagine spending a jolly night with Allen and Sawyer but would probably try my influence to make Allen treat his sister less like a tyrant.

I much enjoy the more satirical run of things in the more recent PP chapters, especially the criticism of the legal system, and I also admire Mr. Pickwick's determination not to submit to the jury's unfair verdict because it adds quite a new dimension to a rather childlike (there's a lot of benevolence and curiosity, but also unchecked temper in Mr. Pickwick) hero. He now arises as a man of principle.

Thackeray calls Vanity Fair a "novel without a hero" and I think he does so because he wants his readers to understand his book as a social comment although the novel is dominated more strongly by the anti-heroine Becky Sharp (one of my favourite characters) than Pickwick dominates PP. Vanity Fair is, on the whole, more serious in tone than Dickens's first novel is, although saying that, one has to bear in mind that the second half of PP also seems to move away from presenting a chain of light-hearted episodes and concentrate on social ills. Maybe, Dickens did not intend this at first, but soon realized that he had more to say than what happens at Manor Farm ...

I was astonished by how heavily the chapters of this instalment relied on coincidence, and I found this slightly annoying even: After a fruitless search for Arabella's whereabouts, Sam happens to run into Mary, who would tell him what he needs to know. This was simply too ridiculous a coincidence to be believable. And then whom should Mr. Winkle meet in Bristol but Mr. Allen and Mr. Sawyer? This was also a very awkward way of tying up loose ends. And why on earth should Mr. Allen talk about Arabella to Mr. Winkle? Apparently, he has a feeling that Mr. Winkle has been making eyes at his sister, and so the last topic he should bring up in Mr. Winkle's presence would be his sister, wouldn't it?

Thackeray calls Vanity Fair a "novel without a hero" and I think he does so because he wants his readers to understand his book as a social comment although the novel is dominated more strongly by the anti-heroine Becky Sharp (one of my favourite characters) than Pickwick dominates PP. Vanity Fair is, on the whole, more serious in tone than Dickens's first novel is, although saying that, one has to bear in mind that the second half of PP also seems to move away from presenting a chain of light-hearted episodes and concentrate on social ills. Maybe, Dickens did not intend this at first, but soon realized that he had more to say than what happens at Manor Farm ...

I was astonished by how heavily the chapters of this instalment relied on coincidence, and I found this slightly annoying even: After a fruitless search for Arabella's whereabouts, Sam happens to run into Mary, who would tell him what he needs to know. This was simply too ridiculous a coincidence to be believable. And then whom should Mr. Winkle meet in Bristol but Mr. Allen and Mr. Sawyer? This was also a very awkward way of tying up loose ends. And why on earth should Mr. Allen talk about Arabella to Mr. Winkle? Apparently, he has a feeling that Mr. Winkle has been making eyes at his sister, and so the last topic he should bring up in Mr. Winkle's presence would be his sister, wouldn't it?

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 38

...our good friend Mr Winkle is stepping out of the Frying-pan and walking “gently and comfortably into the Fire.” Have..."

Help me out here.... Mary and Sam meet and conc..."

Mary Lou

I just googled Mr Winkle. Gee, not the same person, er, species as our Mr Winkle. Thank you for the suggestion to learn about another Winkle.

...our good friend Mr Winkle is stepping out of the Frying-pan and walking “gently and comfortably into the Fire.” Have..."

Help me out here.... Mary and Sam meet and conc..."

Mary Lou

I just googled Mr Winkle. Gee, not the same person, er, species as our Mr Winkle. Thank you for the suggestion to learn about another Winkle.

Tristram wrote: "I much enjoy the more satirical run of things in the more recent PP chapters, especially the criticism of the legal system, and I also admire Mr. Pickwick's determination not to submit to the jury'..."

Yes, indeed. Coincidence has always been a hallmark of Dickens but he does stretch it a bit far in places within PP. I’d put it down to Dickens’s early writing style. I can’t think of a novel that does not contain at least one seemingly surprising coincidence but PP certainly has many.

The change in mood and tone that seems to shade the exuberance of the first part of the novel comes, I believe, as Dickens begins to find his own voice and groove. The first chapters of The Pickwick Papers were focussed more on the desires of Seymour and the publishers. Dickens was brought in to complement a book on sporting scenes. It was not long, however, before Dickens became the alpha of the group. Whether Dickens was, in any way, too much of a stress to Seymour will keep critics busy for decades to come.

Certainly, it is noticeable that the sporting life and rambling tales of the first part of the book step back and the motifs of poverty, greed, incarceration, political corruption and the like step forward into the spotlight. When we consider that he started writing Oliver Twist before even completing PP we can see how Dickens assumes centre stage for his own unique voice to be heard.

Yes, indeed. Coincidence has always been a hallmark of Dickens but he does stretch it a bit far in places within PP. I’d put it down to Dickens’s early writing style. I can’t think of a novel that does not contain at least one seemingly surprising coincidence but PP certainly has many.

The change in mood and tone that seems to shade the exuberance of the first part of the novel comes, I believe, as Dickens begins to find his own voice and groove. The first chapters of The Pickwick Papers were focussed more on the desires of Seymour and the publishers. Dickens was brought in to complement a book on sporting scenes. It was not long, however, before Dickens became the alpha of the group. Whether Dickens was, in any way, too much of a stress to Seymour will keep critics busy for decades to come.

Certainly, it is noticeable that the sporting life and rambling tales of the first part of the book step back and the motifs of poverty, greed, incarceration, political corruption and the like step forward into the spotlight. When we consider that he started writing Oliver Twist before even completing PP we can see how Dickens assumes centre stage for his own unique voice to be heard.

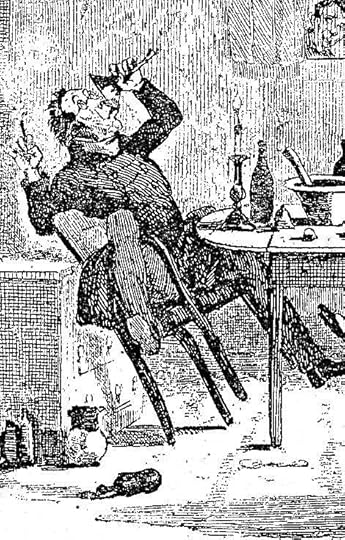

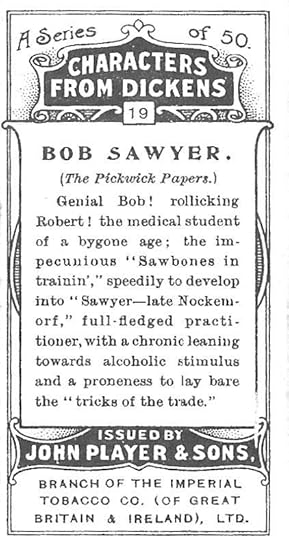

Conviviality at Bob Sawyer's

Chapter 38

Phiz - 1837

Commentary:

As one might well expect in a picaresque novel, the indefatigable flim-flam artist Bob Sawyer turns up again, this time established as an apothecary in Bristol, which Mr. Pickwick visits in order to bring back the fugitive Mr. Winkle to Bath. Winkle has fled Royal Crescent (photograph)for fear of Dowler's exacting vengeance for Winkle's supposedly trying to elope with Mrs. Dowler (see the second April illustration). Although formerly a medical student at Guy's Hospital in London, clearly Bob knows little about the professional calling he has assumed; otherwise, he would not be drinking punch from a chemist's vessel! He and his fellow student Ben Allen, proprietors of the Bristol surgery, are going bankrupt, so that the numerous drawers in the apothecary shop contain nothing. However, the bachelor medical students have their shop well-stocked with alcohol, which the timid Winkle agrees reluctantly to consume with them, despite the earliness of the hour. Only Winkle's presence is out of the ordinary — the pair over the past three weeks of their business arrangement have "been wavering between intoxication partial, and intoxication complete."

Bob Sawyer's return was the immediate precursor of the arrival of a meat-pie from the baker's, of which that gentleman insisted on his staying to partake. The cloth was laid by an occasional charwoman, who officiated in the capacity of Mr. Bob Sawyer's housekeeper; and a third knife and fork having been borrowed from the mother of the boy in the gray livery (for Mr. Sawyer's domestic arrangements were as yet conducted on a limited scale), they sat down to dinner; the beer being served up, as Mr. Sawyer remarked, "in its native pewter."

After dinner, Mr. Bob Sawyer ordered in the largest mortar in the shop, and proceeded to brew a reeking jorum of rum-punch therein, stirring up and amalgamating the materials with a pestle in a very creditable and apothecary-like manner. Mr. Sawyer, being a bachelor, had only one tumbler in the house, which was assigned to Mr. Winkle as a compliment to the visitor, Mr. Ben Allen being accommodated with a funnel with a cork in the narrow end, and Bob Sawyer contented himself with one of those wide-lipped crystal vessels inscribed with a variety of cabalistic characters, in which chemists are wont to measure out their liquid drugs in compounding prescriptions. These preliminaries adjusted, the punch was tasted, and pronounced excellent; and it having been arranged that Bob Sawyer and Ben Allen should be considered at liberty to fill twice to Mr. Winkle's once, they started fair, with great satisfaction and good-fellowship. [chapter 38]

Since the gentleman to the right holds a tumbler, he must be Winkle; Ben Allen falls back in his chair as he drinks punch from a funnel; Bob, presiding as the host, rests his right hand on the table, perhaps to steady himself against advancing tipsiness, while he consumes his potation from an apothecary's measuring vessel. The shop boy peeps through the glass door in the rear, watching his employers rather than "devoting the evening to his ordinary occupation of writing his name on the counter, and rubbing it out again" (ch. 38). Remark Guiliano and Collins,

The reintroduction of Bob Sawyer serves two functions: it aids in the development of the Winkle/Arabella [Allen romantic] subplot that is now put centre stage, and it permits Dickens to take some more comic jabs at the medical profession, as he has with the clergy and the law. All three are traditional objects of satire in the picaresque novel.

Travelling medical students Ben Allen and Bob Sawyer made their initial appearance in chapter 30, when old Mr. Wardle introduces Pickwick — and the reader — to the hedonistic pair of bachelors. Clearly Phiz has made use of the following descriptions in his May illustration of the hosts of the party in the back room of the apothecary shop:

Mr. Benjamin Allen was a coarse, stout, thick-set young man, with black hair cut rather short, and a white face cut rather long. He was embellished with spectacles, and wore a white neckerchief. Below his single-breasted black surtout, which was buttoned up to his chin, appeared the usual number of pepper- and-salt coloured legs, terminating in a pair of imperfectly polished boots. Although his coat was short in the sleeves, it disclosed no vestige of a linen wristband; and although there was quite enough of his face to admit of the encroachment of a shirt collar, it was not graced by the smallest approach to that appendage. He presented, altogether, rather a mildewy appearance, and emitted a fragrant odour of full-flavoured Cubas.

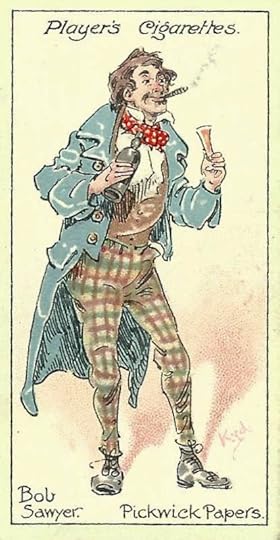

Mr. Bob Sawyer, who was habited in a coarse, blue coat, which, without being either a greatcoat or a surtout, partook of the nature and qualities of both, had about him that sort of slovenly smartness, and swaggering gait, which is peculiar to young gentlemen who smoke in the streets by day, shout and scream in the same by night, call waiters by their Christian names, and do various other acts and deeds of an equally facetious description. He wore a pair of plaid trousers, and a large, rough, double-breasted waistcoat; out of doors, he carried a thick stick with a big top. He eschewed gloves, and looked, upon the whole, something like a dissipated Robinson Crusoe.

Such were the two worthies to whom Mr. Pickwick was introduced, as he took his seat at the breakfast-table on Christmas morning.

Referring back to that chapter, the reader can identify Ben Allen (left) by virtue of his "black hair cut rather short," and his spectacles, and Bob Sawyer (centre) merely by his "slovenly smartness, and swaggering gait."

Details:

Tippling Ben Allen

Bob Sawyer and Nathaniel Winkle

The shelves of the apothecary's

If you can see these shelves, you can do at least one thing I can't.

Mr. Bob Sawyer's boy.....peeped through the glass door, and thus listened and looked on at the same time

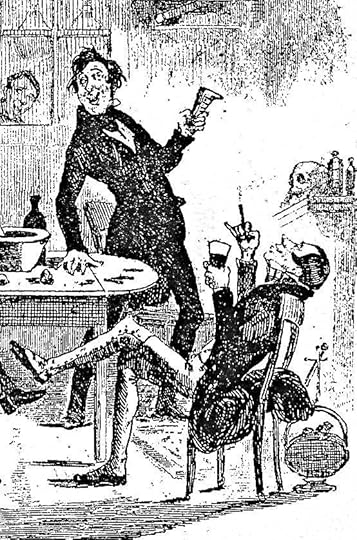

Chapter 38

Phiz

1874 - Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

After dinner, Mr. Bob Sawyer ordered in the largest mortar in the shop, and proceeded to brew a reeking jorum of rum-punch therein, stirring up and amalgamating the materials with a pestle in a very creditable and apothecary-like manner. Mr. Sawyer, being a bachelor, had only one tumbler in the house, which was assigned to Mr. Winkle as a compliment to the visitor, Mr. Ben Allen being accommodated with a funnel with a cork in the narrow end, and Bob Sawyer contented himself with one of those wide-lipped crystal vessels inscribed with a variety of cabalistic characters, in which chemists are wont to measure out their liquid drugs in compounding prescriptions. These preliminaries adjusted, the punch was tasted, and pronounced excellent; and it having been arranged that Bob Sawyer and Ben Allen should be considered at liberty to fill twice to Mr. Winkle’s once, they started fair, with great satisfaction and good-fellowship.

There was no singing, because Mr. Bob Sawyer said it wouldn’t look professional; but to make amends for this deprivation there was so much talking and laughing that it might have been heard, and very likely was, at the end of the street. Which conversation materially lightened the hours and improved the mind of Mr. Bob Sawyer’s boy, who, instead of devoting the evening to his ordinary occupation of writing his name on the counter, and rubbing it out again, peeped through the glass door, and thus listened and looked on at the same time.

"Bless my soul, every body says, 'Somebody taken suddenly ill! Sawyer, late Nockemorf, sent for!"

Chapter 38

Thomas Nast - 1874 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘Then shut the door, and mind the shop.’

‘Come,’ said Mr. Winkle, as the boy retired, ‘things are not quite so bad as you would have me believe, either. There is some medicine to be sent out.’

Mr. Bob Sawyer peeped into the shop to see that no stranger was within hearing, and leaning forward to Mr. Winkle, said, in a low tone—

‘He leaves it all at the wrong houses.’

Mr. Winkle looked perplexed, and Bob Sawyer and his friend laughed.

‘Don’t you see?’ said Bob. ‘He goes up to a house, rings the area bell, pokes a packet of medicine without a direction into the servant’s hand, and walks off. Servant takes it into the dining-parlour; master opens it, and reads the label: “Draught to be taken at bedtime—pills as before—lotion as usual—the powder. From Sawyer’s, late Nockemorf’s. Physicians’ prescriptions carefully prepared,” and all the rest of it. Shows it to his wife—she reads the label; it goes down to the servants—they read the label. Next day, boy calls: “Very sorry—his mistake—immense business—great many parcels to deliver—Mr. Sawyer’s compliments—late Nockemorf.” The name gets known, and that’s the thing, my boy, in the medical way. Bless your heart, old fellow, it’s better than all the advertising in the world. We have got one four-ounce bottle that’s been to half the houses in Bristol, and hasn’t done yet.’

‘Dear me, I see,’ observed Mr. Winkle; ‘what an excellent plan!’

‘Oh, Ben and I have hit upon a dozen such,’ replied Bob Sawyer, with great glee. ‘The lamplighter has eighteenpence a week to pull the night-bell for ten minutes every time he comes round; and my boy always rushes into the church just before the psalms, when the people have got nothing to do but look about ‘em, and calls me out, with horror and dismay depicted on his countenance. “Bless my soul,” everybody says, “somebody taken suddenly ill! Sawyer, late Nockemorf, sent for. What a business that young man has!”’

Mr. Bob Sawyer and Mr. Ben Allen

Chapter 38

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867 Household Edition

Commentary:

In this thirteenth full-page character study for the last novel in the compact American publication, Eytinge focuses on the whimsical pair of medical students, Ben Allen and Bob Sawyer.

After Ben Allen and Bob Sawyer leave Guy's Hospital in London, set up a pharmacy in Bristol, having bought the business from a German named Nockemorf, undoubtedly a continuation of Dickens's satire on the medical profession (the Germanic pun constitutes a humorous allusion to the propensity of drug prescriptions' often having unfortunate consequences for the patient). Compare this realistic dual character study to Phiz's May 1837 illustration "Conviviality at Bob Sawyer's" (plate) in which the jovial bachelor plays host, after the consumption of a meat pie from the baker's nearby (undoubtedly purchased on credit) by using a large mortar and pestle (clearly evident in Eytinge's woodcut) to mix "a reeking jorum of rum-punch," which, short of tumblers, he consumes from a chemist's vessel, while his guest, Mr. Winkle, uses the only glass. As in the text, in Eytinge's illustration Ben Allen consumes his portion in "a funnel with a cork in the narrow end."

After dinner, Mr. Bob Sawyer ordered in the largest mortar in the shop, and proceeded to brew a reeking jorum of rum-punch therein, stirring up and amalgamating the materials with a pestle in a very creditable and apothecary-like manner. Mr. Sawyer, being a bachelor, had only one tumbler in the house, which was assigned to Mr. Winkle as a compliment to the visitor, Mr. Ben Allen being accommodated with a funnel with a cork in the narrow end, and Bob Sawyer contented himself with one of those wide-lipped crystal vessels inscribed with a variety of cabalistic characters, in which chemists are wont to measure out their liquid drugs in compounding prescriptions. These preliminaries adjusted, the punch was tasted, and pronounced excellent; and it having been arranged that Bob Sawyer and Ben Allen should be considered at liberty to fill twice to Mr. Winkle's once, they started fair, with great satisfaction and good-fellowship.

Comparing Eytinge's study with Phiz's original, one is immediately struck by two features of the 1867 version: its comparative dearth of background detail, establishing the setting as an apothecary's shop, and the artist's rendering the medical gentlemen as three-dimensional individuals in terms of their physical types, clothing, postures, and attitudes. Whereas only his glasses and his tipping back in his chair set him apart from Bob and Winkle in the 1837 illustration, here Ben's more philosophical visage is complemented by his slumping in his chair as he smokes a cigar. Bob Sawyer, on the other hand — distinguished in costume from his business partner by his "flash" waistcoat, high collar, patterned trousers, and tousled hair — hoists his cabalistic glass to Winkle (not depicted, but assumed to be present here, although clearly enjoying himself in Phiz's 1837 steel engraving). Phiz realises a highly specific moment, with the shop boy peering in through the window; Eytinge renders the owners of thge business in a more substantial, less cartoonish manner than Phiz, but offers the reader none of the telling and delightful contextual details of the type that characterise the work of Dickens's principal illustrator from 1836 through 1859. In his 1873 program of illustration for the Household Edition volume, Phiz elected to translate the 1837 bacchic scene of Bob Sawyer, Ben Allen, and Winkle tippling in the apothecary's back room into a woodcut, to complement a scene depicting the antics of the drunken footmen as Mr. Tuckle, their chief at the "Swarry" in Bath, does a frog hornpipe on the table top as Sam Weller applauds his host's agility. In this later version of "Mr. Bob Sawyer's boy. . . peeped through the glass door, and thus listened and looked on at the same time" ( to be matched against a scene in the previous chapter), Phiz has maintained the details in the background and rendered the three chief figures somewhat more realistically, conveying a sense of the physical comedy but without the grotesque hyperbole of his earlier work. Nevertheless, his figures are not as convincing as Eytinge's in the 1867 Diamond Edition.

"Unlock that door, and leave this room immediately, Sir," said Mr. Winkle.

Chapter 38

Phiz - 1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

Although in his original series Phiz allowed some space for the misadventures of the medical students Bob Sawyer and Ben Allen, he did not provide visual counterparts to the romance between Pickwick intimate Nathaniel Winkle and Arabella Allen, probably because the limited program of two illustrations per monthly part prevented such realisation. However, freed from such constraints in the Household Edition of the novel, Phiz in "'Unlock that door, and leave this room immediately, sir,' said Mr. Winkle", refers to ch. 38, as Dickens introduces the Winkle/Arabella Allen romantic subplot. On the other hand, Thomas Nast (apparently not interested in Ben Allen or his sister) maintains Bob Sawyer, who has set up a pharmacy with Ben Allen at Bristol, as the focus of his ch. 38 woodcut in "'Bless my soul!' every body says, 'Somebody taken suddenly ill! Sawyer, late Knockenorf, sent for!'"

The highly episodic plot now shifts to the bustling port city of Bristol as the Pickwickians interact with the scapegrace Guy's Hospital students Ben Allen and Bob Sawyer, who have bought out the practice of a German pharmacist named "Nockemorf," clearly a Dickensian pun on the poor quality of medical treatment provided by chemists, whom the poor often consulted as a cheap alternative to physicians. Winkle, trying to escape a confrontation with the irate Dowler, determines to escape from Bath, and, finding a coach outside the Royal Hotel bound for nearby Bristol, concludes that that will be as good a place as any other to hide until the affair blows over. A Victorian reader might have accepted this plot development as mere coincidence, or as evidence of a Divine plan, since Winkle's visit to Bristol results in his re-establishing contact with the Allens. Wandering around the port, Winkle stumbles upon a "Surgery" whose proprietor in green spectacles (strongly realised in Nast's illustration) turns out to be Bob Sawyer. After a convivial visit, Winkle encounters Dowler, who apologises for his behaviour at Royal Crescent, apparently as much afraid of provoking a duel as Winkle. The timid Pickwickian, now feeling much more secure, retires to his room at The Bush, where shortly afterward Sam Weller arrives, charged by Pickwick to bring Winkle back to Bath. However, having learned from Ben Allen that Arabella (with whom he had fallen at Wardle's) is living not far from Bristol at an aunt's, Winkle is not disposed to leave, and bargains with Sam Weller to be permitted to remain for a few days. This, then, is the relatively minor passage realised in this Phiz illustration, one of twenty-seven entirely new scenes which Dickens's principal illustrator devised in 1873 for the Household Edition:

The young man gave a gentle kick at one of the lower panels of the door, after he had given utterance to this hint, as if to add force and point to the remark.

"Is that you, Sam?" inquired Mr. Winkle, springing out of bed.

"Quite unpossible to identify any gen'l'm'n vith any degree o' mental satisfaction, vithout lookin' at him, sir,' replied the voice dogmatically.

Mr. Winkle, not much doubting who the young man was, unlocked the door; which he had no sooner done than Mr. Samuel Weller entered with great precipitation, and carefully relocking it on the inside, deliberately put the key in his waistcoat pocket; and, after surveying Mr. Winkle from head to foot, said —

"You're a wery humorous young gen'l'm'n, you air, sir!"

"What do you mean by this conduct, Sam?' inquired Mr. Winkle indignantly. 'Get out, sir, this instant. What do you mean, sir?"

"What do I mean,' retorted Sam; "come, sir, this is rayther too rich, as the young lady said when she remonstrated with the pastry-cook, arter he'd sold her a pork pie as had got nothin' but fat inside. What do I mean! Well, that ain't a bad 'un, that ain't."

"Unlock that door, and leave this room immediately, sir," said Mr. Winkle.

"I shall leave this here room, sir, just precisely at the wery same moment as you leaves it,' responded Sam, speaking in a forcible manner, and seating himself with perfect gravity.

Nathaniel Winkle, depicted as an angry, lean young man in a night-shirt and rather diminutive night-cap, strides towards Sam, who smiles complacently as he sits on the chair to block Winkle's escape. Phiz implies that, although Winkle may sound self-assertive and even aggressive, Sam knows very well that he is easily cowed and feels sure that he can carry out Pickwick's directive. Sam Weller is this illustration resembles the Sam of previous woodcuts, and Winkle's profile from the previous illustration ("Mr. Bob Sawyer's Boy . . . . peeped through the glass door, and thus listened and looked on at the same time") does indeed that of the night-shirt wearer here. For this same chapter, Thomas Nast, on the other hand, focuses on the character and business circumstances of Ben Allen's partner, Bob Sawyer, his illustration being based on the following passage in which Bob explains his advertising strategy to the naive Winkle:

Mr. Winkle looked perplexed, and Bob Sawyer and his friend laughed.

"Don't you see?" said Bob. "He goes up to a house, rings the area bell, pokes a packet of medicine without a direction into the servant's hand, and walks off. Servant takes it into the dining-parlour; master opens it, and reads the label: "Draught to be taken at bedtime — pills as before — lotion as usual — the powder. From Sawyer's, late Nockemorf's. Physicians' prescriptions carefully prepared," and all the rest of it. Shows it to his wife — she reads the label; it goes down to the servants — they read the label. Next day, boy calls: "Very sorry — his mistake — immense business — great many parcels to deliver — Mr. Sawyer's compliments — late Nockemorf." The name gets known, and that's the thing, my boy, in the medical way. Bless your heart, old fellow, it's better than all the advertising in the world. We have got one four-ounce bottle that's been to half the houses in Bristol, and hasn't done yet."

"Dear me, I see," observed Mr. Winkle; "what an excellent plan!"

"Oh, Ben and I have hit upon a dozen such," replied Bob Sawyer, with great glee. "The lamplighter has eighteenpence a week to pull the night-bell for ten minutes every time he comes round; and my boy always rushes into the church just before the psalms, when the people have got nothing to do but look about 'em, and calls me out, with horror and dismay depicted on his countenance. "Bless my soul," everybody says, "somebody taken suddenly ill! Sawyer, late Nockemorf, sent for. What a business that young man has!"'

"My dear," said Mr. Pickwick, looking over the wall, and catching sight of Arabella on the other side. "Don't be frightened, my dear,k 'tis only me."

Chapter 39

Phiz - 1874 Household Edition

"Lor Do Adun, Mr. Weller!"

Chapter 39

Thomas Nast

1874 Household Edition

"Don't Be Longer Than You Can Conveniently Help, Sir. You're Rather Heavy."

Chapter 39

Thomas Nast

1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

Having been sent by Pickwick on the seemingly impossible quest for Arabella Allen's aunt's house on the outskirts of Bristol, investigating likely villas in the suburbs Sam Weller runs into Mary, formerly Mr. Nupkins's maid at Ipswich, who by coincidence (type in bold for Tristram) knows where Arabella Allen is staying — immediately next door. A pleasant interlude involves Sam and the pretty house-maid exchanging a few kisses, a minor moment in the narrative strikingly captured by Thomas Nast in his illustration of the epiusode:

Incorporating salient background details, Nast has included one of the carpets that Mary had come outside to shake, the garden door into the laneway, and a large villa beyond the garden wall:

Mr. Weller was a gentleman of great gallantry in his own way, and he no sooner remarked this circumstance than he hastily rose from the large stone, and advanced towards her.

"My dear," said Sam, sliding up with an air of great respect, "you'll spile that wery pretty figure out o' all perportion if you shake them carpets by yourself. Let me help you."

The young lady, who had been coyly affecting not to know that a gentleman was so near, turned round as Sam spoke — no doubt (indeed she said so, afterwards) to decline this offer from a perfect stranger — when instead of speaking, she started back, and uttered a half-suppressed scream. Sam was scarcely less staggered, for in the countenance of the well-shaped female servant, he beheld the very features of his valentine, the pretty housemaid from Mr. Nupkins's.

"Wy, Mary, my dear!" said Sam.

"Lauk, Mr. Weller," said Mary, "how you do frighten one!"

Sam made no verbal answer to this complaint, nor can we precisely say what reply he did make. We merely know that after a short pause Mary said, "Lor, do adun, Mr. Weller!" and that his hat had fallen off a few moments before — from both of which tokens we should be disposed to infer that one kiss, or more, had passed between the parties.

Subsequently, clambering up the wall by means of the overhanging boughs of a great pear-tree (more like an oak in Phiz's illustration), Sam makes contact with Arabella, and arranges that she will be out in the garden again the following evening, after sunset. When Sam returns to The Bush at Bristol with this intelligence, Pickwick determines to accompany Winkle and Sam to serve as a sort of chaperon. This, then, is the situation that both Nast and Phiz describe in their illustrations for chapter 39's "garden assignation," although neither includes Pickwick's dark lantern, which affords considerable comic business:

"Is Miss Allen in the garden yet, Mary?" inquired Mr. Winkle, much agitated.

"I don't know, sir,' replied the pretty housemaid. 'The best thing to be done, sir, will be for Mr. Weller to give you a hoist up into the tree, and perhaps Mr. Pickwick will have the goodness to see that nobody comes up the lane, while I watch at the other end of the garden. Goodness gracious, what's that?"

"That 'ere blessed lantern 'ull be the death on us all," exclaimed Sam peevishly. "Take care wot you're a-doin' on, sir; you're a-sendin' a blaze o' light, right into the back parlour winder."

"Dear me!" said Mr. Pickwick, turning hastily aside, "I didn't mean to do that."

"Now, it's in the next house, sir," remonstrated Sam.

"Bless my heart!" exclaimed Mr. Pickwick, turning round again.

"Now, it's in the stable, and they'll think the place is afire," said Sam. "Shut it up, sir, can't you?"

"It's the most extraordinary lantern I ever met with, in all my life!" exclaimed Mr. Pickwick, greatly bewildered by the effects he had so unintentionally produced. "I never saw such a powerful reflector."

"It'll be vun too powerful for us, if you keep blazin' avay in that manner, sir," replied Sam, as Mr. Pickwick, after various unsuccessful efforts, managed to close the slide. 'There's the young lady's footsteps. Now, Mr. Winkle, sir, up vith you."

"Stop, stop!" said Mr. Pickwick, "I must speak to her first. Help me up, Sam."

"Gently, sir," said Sam, planting his head against the wall, and making a platform of his back. "Step atop o' that 'ere flower-pot, Sir. Now then, up vith you."

"I'm afraid I shall hurt you, Sam,' said Mr. Pickwick.

"Never mind me, sir," replied Sam. "Lend him a hand, Mr. Winkle. sir. Steady, sir, steady! That's the time o' day!'"

As Sam spoke, Mr. Pickwick, by exertions almost supernatural in a gentleman of his years and weight, contrived to get upon Sam's back; and Sam gently raising himself up, and Mr. Pickwick holding on fast by the top of the wall, while Mr. Winkle clasped him tight by the legs, they contrived by these means to bring his spectacles just above the level of the coping.

"My dear," said Mr. Pickwick, looking over the wall, and catching sight of Arabella, on the other side, "don't be frightened, my dear, it's only me."

"Oh, pray go away, Mr. Pickwick," said Arabella. "Tell them all to go away. I am so dreadfully frightened. Dear, dear Mr. Pickwick, don't stop there. You'll fall down and kill yourself, I know you will."

"Now, pray don't alarm yourself, my dear," said Mr. Pickwick soothingly. "There is not the least cause for fear, I assure you. Stand firm, Sam," said Mr. Pickwick, looking down.

"All right, sir," replied Mr. Weller. "Don't be longer than you can conweniently help, sir. You're rayther heavy."

"Only another moment, Sam,' replied Mr. Pickwick.

"I merely wished you to know, my dear, that I should not have allowed my young friend to see you in this clandestine way, if the situation in which you are placed had left him any alternative; and, lest the impropriety of this step should cause you any uneasiness, my love, it may be a satisfaction to you, to know that I am present. That's all, my dear."

"Indeed, Mr. Pickwick, I am very much obliged to you for your kindness and consideration," replied Arabella, drying her tears with her handkerchief. She would probably have said much more, had not Mr. Pickwick's head disappeared with great swiftness, in consequence of a false step on Sam's shoulder which brought him suddenly to the ground. He was up again in an instant, however, and bidding Mr. Winkle make haste and get the interview over, ran out into the lane to keep watch, with all the courage and ardour of youth. Mr. Winkle himself, inspired by the occasion, was on the wall in a moment, merely pausing to request Sam to be careful of his master.

The illustrations complement each other insofar as Phiz's represents the earlier moment, when Pickwick gets up on Sam's back, whereas in Nast's illustration Pickwick stands on Sam's shoulders to converse with Arabella. Whereas Nast's interpretation is more realistic in that all the figures are but dimly apprehended in the darkness, Phiz's more clearly reveals the postures, positions, and expressions of the three principals, avuncular Samuel Pickwick, the romantic Nathaniel Wardle, and the enabling Sam Weller. However, from the point of view of situation and character comedy, Phiz's treatment is vastly more entertaining because his figures are better modelled and individualised; in particular, Pickwick seems oblivious to Sam's exertions as he is caught up in his role as advisor to the young couple, while Sam Weller and Nathaniel Winkle are captured in awkward positions, supporting their chief. In order to show clearly the irregularities of the wall and the tree, as well as the particulars of the three men, Phiz has had to disregard the lack of available light. In contrast, Nast manages his material in a realistic manner, but without any humour — but at least his illustration occurs on the same page as the passage visualised, whereas the reader has to flip back a dozen pages to re-read the passage associated with the woodcut on page 289 of the Chapman and Hall Household Edition.

The farcical situation itself seems to be a reprise of the ladies' seminary escapade of chapter 16, which, as Collins and Guiliano note, reveals the influence of Elizabeth Simpson Inchbald's plot gambits upon Dickens, who had read her Collection of Farces (1807): "Dickens surely drew upon Mrs. Inchbald's plays and perhaps other works of popular theatre and literature for this scene" (The Annotated Dickens, I: 378).

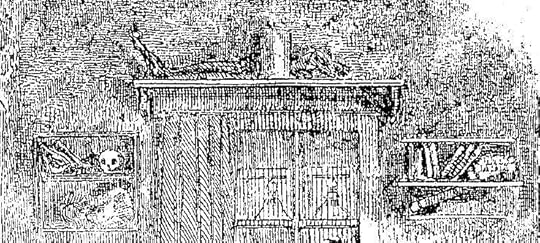

Mr. Pickwick sits for his Portrait

Chapter 40

Phiz - 1837

Commentary:

Phiz depicts the passage in which the prison staff gathers around poor Pickwick to memorize what he looks like — a necessary procedure in the days before photography. In other words, our protagonist undergoes what some in the twenty-first century euphemistically and bureaucratically term "security imaging processing." Pickwick has found himself in this situation because he has stubbornly refused to be "bailed" or to have his solicitor, Perker, pay the damages awarded by the court.

Here they stopped, while the tipstaff delivered his papers; and here Mr. Pickwick was apprised that he would remain, until he had undergone the ceremony, known to the initiated as "sitting for your portrait."

"Sitting for my portrait?" said Mr. Pickwick.

"Having your likeness taken, sir," replied the stout turnkey. "We're capital hands at likenesses here. Take 'em in no time, and always exact. Walk in, sir, and make yourself at home."

Mr. Pickwick complied with the invitation, and sat himself down; when Mr. Weller, who stationed himself at the back of the chair, whispered that the sitting was merely another term for undergoing an inspection by the different turnkeys, in order that they might know prisoners from visitors.

"Well, Sam," said Mr. Pickwick, "then I wish the artists would come. This is rather a public place."

"They von't be long, Sir, I des-say," replied Sam. "There's a Dutch clock, sir."

"So I see," observed Mr. Pickwick.

"And a bird-cage, sir," says Sam. "Veels vithin veels, a prison in a prison. Ain't it, Sir?"

As Mr. Weller made this philosophical remark, Mr. Pickwick was aware that his sitting had commenced. The stout turnkey having been relieved from the lock, sat down, and looked at him carelessly, from time to time, while a long thin man who had relieved him, thrust his hands beneath his coat tails, and planting himself opposite, took a good long view of him. A third rather surly-looking gentleman, who had apparently been disturbed at his tea, for he was disposing of the last remnant of a crust and butter when he came in, stationed himself close to Mr. Pickwick; and, resting his hands on his hips, inspected him narrowly; while two others mixed with the group, and studied his features with most intent and thoughtful faces. Mr. Pickwick winced a good deal under the operation, and appeared to sit very uneasily in his chair; but he made no remark to anybody while it was being performed, not even to Sam, who reclined upon the back of the chair, reflecting, partly on the situation of his master, and partly on the great satisfaction it would have afforded him to make a fierce assault upon all the turnkeys there assembled, one after the other, if it were lawful and peaceable so to do.

At length the likeness was completed, and Mr. Pickwick was informed that he might now proceed into the prison.

Pickwick, indignant at having lost his breach-of-promise case against Mrs. Bardell, refuses to pay the substantial damages the court has awarded her. In due course, upon arriving back in London, he is arrested, and consigned to the Fleet, a debtors' prison then at the junction of London's Fleet and Farringdon Streets. Rebuilt after the Gordon Riots of 1780, the Fleet Prison was demolished in 1845-46 to make way for the Holborn Viaduct Railway Station in Central London. Owing to its location, Londoners often referred to the Fleet as "The Farringdon Hotel." While so many of the people whom Pickwick meets in his induction to the penal system would give anything to be released, Samuel Pickwick enters prison of his own volition, in preference to admitting his guilt by paying a fine that, as a retired businessman, he is more than capable of paying.

By the solemn expression on the prisoner's face in Phiz's second May 1837 illustration the viewer can surmise that the full significance of his choosing debtors' prison on a point of principle has now occurred to the determined little man. It must now also be dawning on him that no artists will be arriving to render his likeness, and the the expression "sitting for his portrait" simply means that the various turnkeys are studying his face so that they do not confuse him for a visitor and inadvertently release him. The officials in the room are exactly as Dickens describes them in position, appearance, and posture (hands in pockets, under coat tails, and so forth), with the exception of the small man smoking a pipe in the upper-left corner — he is apparently Phiz's invention. The picture is a realisation not merely of a physical situation but also of Samuel Pickwick's mental state as the artist gives us his principal subject's growing sense of the seriousness of his refusal to pay an unjust judgment.

And at this point in the composition of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club and the production of its two monthly illustrations fate intervened. The death of Dickens's beloved young sister-in-law, Mary Hogarth, on the 6th of May came as such a shock to the writer that he produced no copy for Phiz to illustrate, so that Chapman and Hall issued the next illustrations in the series in July 1837.

Details:

Mr. Pickwick and Sam

The symbolic bird cage (you should already have seen that one Peter)

Mr. Pickwick sitting for his portrait

Chapter 40

Phiz - 1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

Although Dickens, aged 25 at the time he wrote about Pickwick's incarceration for debt, is not likely to have mentioned his own family's involvement in just such an issue some dozen years earlier, the serial writer undoubtedly impressed upon Phiz the importance to the novel's plot of the Fleet Prison scenes in monthly parts 14, 15, 16, and 17 (that is, the instalments for May, July, August, and September, 1837). Thus, in the original serial for chapters 40 through 46, of the pertinent eight illustrations five are set in the Fleet Prison, and four feature Pickwick prominently.

Redrafting many of his original steel engravings for the woodcuts of the Household Edition, Phiz took "Mr. Pickwick sits for his Portrait" as the basis for the first of seven prison scenes (numbers 41 through 47), four of which concern Pickwick, but four of which feature Sam Weller prominently. Thus, even though the Household Edition gave Phiz an opportunity to expand his range of subjects, he elected not to devote more scenes to the Fleet, but did elect to make Sam Weller and Samuel Pickwick joint protagonists in his narrative-pictorial sequence. The passage that Phiz twice realised is this:

Here [at the opening of the Fleet Prison proper] they stopped, while the tipstaff delivered his papers; and here Mr. Pickwick was apprised that he would remain, until he had undergone the ceremony, known to the initiated as "sitting for your portrait."

"Sitting for my portrait?" said Mr. Pickwick.

"Having your likeness taken, sir," replied the stout turnkey. "We're capital hands at likenesses here. Take 'em in no time, and always exact. Walk in, sir, and make yourself at home."

Mr. Pickwick complied with the invitation, and sat himself down; when Mr. Weller, who stationed himself at the back of the chair, whispered that the sitting was merely another term for undergoing an inspection by the different turnkeys, in order that they might know prisoners from visitors.

"Well, Sam," said Mr. Pickwick, "then I wish the artists would come. This is rather a public place."

"They von't be long, Sir, I des-say," replied Sam. "There's a Dutch clock, sir."

"So I see," observed Mr. Pickwick.

"And a bird-cage, sir," says Sam. "Veels vithin veels, a prison in a prison. Ain't it, Sir?"

As Mr. Weller made this philosophical remark, Mr. Pickwick was aware that his sitting had commenced. The stout turnkey having been relieved from the lock, sat down, and looked at him carelessly, from time to time, while a long thin man who had relieved him, thrust his hands beneath his coat tails, and planting himself opposite, took a good long view of him. A third rather surly-looking gentleman, who had apparently been disturbed at his tea, for he was disposing of the last remnant of a crust and butter when he came in, stationed himself close to Mr. Pickwick; and, resting his hands on his hips, inspected him narrowly; while two others mixed with the group, and studied his features with most intent and thoughtful faces. Mr. Pickwick winced a good deal under the operation, and appeared to sit very uneasily in his chair; but he made no remark to anybody while it was being performed, not even to Sam, who reclined upon the back of the chair, reflecting, partly on the situation of his master, and partly on the great satisfaction it would have afforded him to make a fierce assault upon all the turnkeys there assembled, one after the other, if it were lawful and peaceable so to do.

At length the likeness was completed, and Mr. Pickwick was informed that he might now proceed into the prison.

Since the new picture has a horizontal orientation, Phiz had the opportunity to add several turnkeys, for whereas he could conveniently fit only six prison officers into the May 1837 engraving, he included eight in his 1873 redrafting, moving Pickwick and Sam to the left margin so that they are no longer surrounded by jailers. The Dutch clock is still in evidence, but the symbolic birdcage has disappeared. Whereas three of the original jailers look somewhat alike, Phiz organizes the look-alikes into three groups: the pair, dimly apprehended, behind Pickwick; the John Bull pair in the center; and the trio with almost identical faces to the right. Dickens describes the majority of the turnkeys as "stout" and "surly-looking," but lists only five as present at for Pickwick's "sitting." Phiz has disposed of the figures in similar poses and juxtapositions in both illustrations, except that the smoker (left rear) has disappeared and the "long, thin man" with his hands beneath his coat-tails, who is to the extreme left in the 1837 (one of just two turnkeys distinguished by their lacking any sort of hat), is now sitting on a stool, down center, studying Pickwick. Whereas the earlier illustration gives prominence to the barred widows, the later illustration emphasizes a heavy, iron-studded door (right), behind one of the larger jailors. More significantly, Pickwick seems more relaxed and less nervous in the 1873 woodcut, holding his hat jauntily on one knee and maintaining the sort of erect posture one would expect of a person sitting for a portrait. The overall effect of the 1873 revision is Pickwick's occupying a less constricted space, and not being studied quite so closely, for only the man to the right actually focus on him. Sam, as ever, is quite sanguine, perhaps because he knows that at any time Pickwick can elect to pay his fine and leave the confines of the Fleet Prison.

Built in 1197, the notorious prison on the eastern bank of the Fleet River, London, was in continuous use until 1844. Although it was destroyed and rebuilt a number of times (in 1381, during Wat Tyler's Peasants' Revolt; on the third day of the Great Fire of London in 1666; and during the Gordon Riots of 1780), it was not finally demolished until 1846. During the eighteenth century, the Fleet Prison was generally reserved for debtors and bankrupts, often housing about 300 prisoners and even their families. Among the prison's most famous inmates were Metaphysical poet John Donne and American colonizer William Penn. Perhaps as a result of Dickens's use of the Fleet as a setting for Pickwick, William Makepeace Thackeray in 1844 consigned the anti-hero of The Luck of Barry Lyndon there for the last nineteen years of his life, the most famous literary inmate prior to the early nineteenth century being Shakespeare's braggart knight Sir John Falstaff in Henry the Fourth, Part Two. For Dickens, the Shakespeare association was probably paramount, but he significantly avoided using as the setting London's chief debtors' prison, the Marshalsea, in which his own father had been incarcerated in 1824, although he did make use of the Marshalsea as one of the settings for the interpolated Pickwick short story in chapter 21, "The Old Man's Tale of the Queer Client" (Part 8, November 1836).

Kim wrote: "Mr. Bob Sawyer's boy.....peeped through the glass door, and thus listened and looked on at the same time

Chapter 38

Phiz

1874 - Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

After dinner, Mr. Bob Sawyer..."

Thank you Kim. And I do like your “close ups” of some of the illustrations. The original Phiz is rather full of scratchy etchings. The 1874 Phiz allows us to finally see the shelves clearly. The differences between the original first publication of the novel and the later edition gives us a look at how Phiz re-worked his original interpretation. Overall, I find the latter illustrations a bit too clean and sterile. Yet any Phiz is a wonderful Phiz.

Chapter 38

Phiz

1874 - Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

After dinner, Mr. Bob Sawyer..."

Thank you Kim. And I do like your “close ups” of some of the illustrations. The original Phiz is rather full of scratchy etchings. The 1874 Phiz allows us to finally see the shelves clearly. The differences between the original first publication of the novel and the later edition gives us a look at how Phiz re-worked his original interpretation. Overall, I find the latter illustrations a bit too clean and sterile. Yet any Phiz is a wonderful Phiz.

Kim wrote: "Mr. Pickwick sits for his Portrait

Chapter 40

Phiz - 1837

Commentary:

Phiz depicts the passage in which the prison staff gathers around poor Pickwick to memorize what he looks like — a necessar..."

Ah, the bird cage. Thank you Kim. I hope everyone spends a moment looking at the faces in this illustration. Considering their small size in relation to the entire illustration it is remarkable to see how Phiz can give each face a different touch of curiosity towards Mr Pickwick who does sit in the middle of all the gaolers who surround him. In terms of an an emblematic illustration, the gaolers surround the now incarcerated Pickwick just as the metal of a bird cage surrounds the trapped bird. “Veels vithin veels” as Sam so correctly observes.

Chapter 40

Phiz - 1837

Commentary:

Phiz depicts the passage in which the prison staff gathers around poor Pickwick to memorize what he looks like — a necessar..."

Ah, the bird cage. Thank you Kim. I hope everyone spends a moment looking at the faces in this illustration. Considering their small size in relation to the entire illustration it is remarkable to see how Phiz can give each face a different touch of curiosity towards Mr Pickwick who does sit in the middle of all the gaolers who surround him. In terms of an an emblematic illustration, the gaolers surround the now incarcerated Pickwick just as the metal of a bird cage surrounds the trapped bird. “Veels vithin veels” as Sam so correctly observes.

From The History of Pickwick: An Account of Its Characters, Localities, Allusions, and Illustrations, with a Bibliography by Percy Hetherington Fitzgerald, 1891:

Two or three years ago an amusing coincidence brought the author's son, a barrister in good practice, into connection with his father's famous book. It occurred at a trial on the circuit.

Mr. Dickens, who was counsel for the defense, announced that he meant to call Mr. Pickwick. The judge entered into the humor of the thing. "Pickwick," he said, "is a very appropriate character to be called by Dickens". (laughter). With much pleasantness the advocate replied:

"I fully believe that the sole reason why I was instructed in this case was that I might call Mr. Pickwick" (laughter), "and it may interest your lordship to learn that the witness is a descendant, - a grandnephew, I believe, of Mr. Moses Pickwick who kept a coach at Bath, and that I have every reason to believe that it was from this Moses Pickwick that the name of the immortal Pickwick was taken. I daresay your lordship will remember that that very eccentric and faithful follower of Mr. Pickwick - Sam Weller - seeing his name outside of the coach was indignant because he thought it was a personal reflection upon his employer." This little bit of comedy harmonizes well with our old Pickwickian associations. -----

"How I envy," says Mr. Herman Merivale, "the generation which read Pickwick as it came out in numbers, - and my father has told me that it was the phenomenon of the time. My grandfather's whole family of sons and daughters (a very large one), used to cluster round him to hear number after number read out to them. He always studied them himself for an hour or two, in order to be able to read them aloud with decent gravity, and his apoplectic struggles and occasional shouts made them feel bad - longing for their turn." -----

The most impressive testimony to this success is Miss Mitford's letter of rebuke to some incurious Dublin friends who knew nothing of Pickwick:

"So you never heard of the Pickwick Papers! Well, they publish a number once a month, and print 25,000. It is fun - London life - but without anything unpleasant; a lady might read it aloud; and this so graphic, so individual, and so true, that you could courtesy to all the people as you see them in the streets. I did think there had not been a place where English is spoken, to which Boz had not penetrated. All the boys and girls talk his fun - the boys in the streets; and yet those who are of the highest taste like it the most. Sir Benjamin Brodie takes it to read in his carriage between patient and patient; and Lord Dunman studies Pickwick on the Bench while the jury are deliberating. Do take some means to borrow the Pickwick Papers. It seems like not having heard of Hogarth."

Two or three years ago an amusing coincidence brought the author's son, a barrister in good practice, into connection with his father's famous book. It occurred at a trial on the circuit.

Mr. Dickens, who was counsel for the defense, announced that he meant to call Mr. Pickwick. The judge entered into the humor of the thing. "Pickwick," he said, "is a very appropriate character to be called by Dickens". (laughter). With much pleasantness the advocate replied:

"I fully believe that the sole reason why I was instructed in this case was that I might call Mr. Pickwick" (laughter), "and it may interest your lordship to learn that the witness is a descendant, - a grandnephew, I believe, of Mr. Moses Pickwick who kept a coach at Bath, and that I have every reason to believe that it was from this Moses Pickwick that the name of the immortal Pickwick was taken. I daresay your lordship will remember that that very eccentric and faithful follower of Mr. Pickwick - Sam Weller - seeing his name outside of the coach was indignant because he thought it was a personal reflection upon his employer." This little bit of comedy harmonizes well with our old Pickwickian associations. -----

"How I envy," says Mr. Herman Merivale, "the generation which read Pickwick as it came out in numbers, - and my father has told me that it was the phenomenon of the time. My grandfather's whole family of sons and daughters (a very large one), used to cluster round him to hear number after number read out to them. He always studied them himself for an hour or two, in order to be able to read them aloud with decent gravity, and his apoplectic struggles and occasional shouts made them feel bad - longing for their turn." -----

The most impressive testimony to this success is Miss Mitford's letter of rebuke to some incurious Dublin friends who knew nothing of Pickwick:

"So you never heard of the Pickwick Papers! Well, they publish a number once a month, and print 25,000. It is fun - London life - but without anything unpleasant; a lady might read it aloud; and this so graphic, so individual, and so true, that you could courtesy to all the people as you see them in the streets. I did think there had not been a place where English is spoken, to which Boz had not penetrated. All the boys and girls talk his fun - the boys in the streets; and yet those who are of the highest taste like it the most. Sir Benjamin Brodie takes it to read in his carriage between patient and patient; and Lord Dunman studies Pickwick on the Bench while the jury are deliberating. Do take some means to borrow the Pickwick Papers. It seems like not having heard of Hogarth."

Kim

What a great insight you have provided. It is always good to read how much of an impact Dickens had on his audience. It is fascinating to read how often and how common was the reading of Dickens by one person to a group. Along with the human voice, I can also imagine how the novel’s illustrations would have been a valuable asset to the listening audience.

Dickens was a public experience. To hear one of his books read, to see his novels performed on the stage almost immediately after the release of the separate parts (legality or copyright of Dickens’s work totally ignored) and to share the stories with friends, neighbours and relatives all attest to a phenomenon not seen before in literature.