Classics and the Western Canon discussion

Homer, Odyssey revisited

>

Books 15 and 16

Everyman wrote: "Then she says “For thou knowest what sort of a spirit there is in a woman's breast; she is fain to increase the house of the man who weds her, but of her former children and of the lord of her youth she takes no thought, when once he is dead, and asks no longer concerning them.” Does Homer really believe that a woman who remarries forgets all about her children from the first marriage? But maybe that’s how it was in Greek society? .."

Everyman wrote: "Then she says “For thou knowest what sort of a spirit there is in a woman's breast; she is fain to increase the house of the man who weds her, but of her former children and of the lord of her youth she takes no thought, when once he is dead, and asks no longer concerning them.” Does Homer really believe that a woman who remarries forgets all about her children from the first marriage? But maybe that’s how it was in Greek society? .."I don't think it is necessarily Homer who believed a woman forgets her children if she remarries. I think this is a case of Homer showing us, once again, the duplicity of Athena.

In Book 13 Athena assures Odysseus of Penelope's loyalty. And in Book 15 she plants seeds of doubt about Penelope's loyalty to urge Telemachus to hurry home. In each case, Athena has an agenda and will do whatever it takes to promote that agenda.

It's a mistake to think about the Greek or Roman gods as behaving according to some moral code. They don't. They are self-serving, duplicitous, deceitful, manipulative, and vengeful. They lie to humans and lie to each other. Their goal is to promote their agenda by whatever means possible.

Athena is no different. She is no friend to women and will use them to forward her goal. She used Nausicaa and she will use Penelope, accusing her of loyalty or disloyalty depending on which alternative best helps her achieve her aim.

Athena tells Telemachus ““Telemachus, thou dost not well to wander longer far from thy home, leaving behind thee thy wealth and men in thy house so insolent, lest they divide and devour all thy possessions, and thou shalt have gone on a fruitless journey.” Why fruitless when he learned so much? And why did she send him in the first place if she didn’t think the information he would get would be fruitful?

Athena tells Telemachus ““Telemachus, thou dost not well to wander longer far from thy home, leaving behind thee thy wealth and men in thy house so insolent, lest they divide and devour all thy possessions, and thou shalt have gone on a fruitless journey.” Why fruitless when he learned so much? And why did she send him in the first place if she didn’t think the information he would get would be fruitful? I took this more as Telemachus has completed his mission in visiting Nestor and Menelaus, and it’s time to get home pronto. There’s no more intel to be gathered, and both Menelaus with his plans for a road trip and Nestor with his ceremonious hospitality are in no hurry to let Telemachus go. It doesn’t mean the trip wasn’t worthwhile, but delay getting home could be dangerous. And Telemachus takes her words to heart, even kicking his friend to wake him up immediately. (I wonder if the interchange between the two highlights again Telemachus’s unfamiliarity with horses on Ithaca)

Remember Nestor concluded the moral of his story is that you shouldn't stay away from home for too long?

Remember Nestor concluded the moral of his story is that you shouldn't stay away from home for too long?I thought it's funny that Telemachus ended up staying with Menelaus for the next 11 books. It seems Telemachus is picky about who he listens to. (I suppose Athena is also trying to protect him from murderous, ambushing suitors.)

Lia wrote: "

Lia wrote: "I thought it's funny that Telemachus ended up staying with Menelaus for the next 11 books.."

Aren't those books just a report of what Odysseus was going through over the ten years since Troy fell? How much real time was passing while we got that information? I don't think that much actual time passed between the end of Book 4 and the start of Book 11.

Everyman wrote: "How much real time was passing while we got that information? I don't think that much actual time passed between the end of Book 4 and the start of Book 11..."

Everyman wrote: "How much real time was passing while we got that information? I don't think that much actual time passed between the end of Book 4 and the start of Book 11..."Athena and Hermes left the (second) assembly at the same time with Zeus' instruction, so I assume they "activated" Odysseus and Telemachus at the same time.

Odysseus took time to build his boat, share some sexy time with Calypso again, before he finally sailed off. It took him 20 days to get to Scheria, another 3 days or so to get from Scheria to Ithaca. Odysseus already slept in Ithaca, met Athena, met and spent time with Eumaeus before Telemachus comes back.

So I'm guessing Telemachus spent roughly 20 days or so at Menelaus. Given how much Telemachus had changed since he left home, it feels like very long time.

Everyman wrote: "Lia wrote: "

Everyman wrote: "Lia wrote: "I thought it's funny that Telemachus ended up staying with Menelaus for the next 11 books.."

Aren't those books just a report of what Odysseus was going through over the ten years sin..."

I think the Odyssey covers a period of approx. 40 days.

Lia wrote: "So I'm guessing Telemachus spent roughly 20 days or so at Menelaus. Given how much Telemachus had changed since he left home, it feels like very long time...

Lia wrote: "So I'm guessing Telemachus spent roughly 20 days or so at Menelaus. Given how much Telemachus had changed since he left home, it feels like very long time...How has Telemachus changed?

Is professing to killing a man really the best way to make good first impression and ask for help from strangers?

Is professing to killing a man really the best way to make good first impression and ask for help from strangers?First it was Odysseus to a disguised Athena:

I’ve been on the runThen it was Theoclymenus to Telemachus:

Since killing a man, Orsilochus,

[13.270] Idomeneus’ son, the great sprinter.

And godlike Theoclymenus answered:

“I, too, have left my country, because

[15.300] I killed a man, one of my own clan.

Tamara wrote: "Lia wrote: "So I'm guessing Telemachus spent roughly 20 days or so at Menelaus. Given how much Telemachus had changed since he left home, it feels like very long time...

Tamara wrote: "Lia wrote: "So I'm guessing Telemachus spent roughly 20 days or so at Menelaus. Given how much Telemachus had changed since he left home, it feels like very long time...How has Telemachus changed?"

Most of the changes we've witnessed were in the first 4 books. He turned from a self-pitying 20-something not acting his age, who passively fantasizes about daddy coming home to drive suitors away so that he can be happy ever after — unrealistic counterfactuals that involve no efforts on his part, to someone who is more adult, embraces of his Ithacan root, stands up to Menelaus’ somewhat patronizing generosity with diplomacy, and sees himself in a more decisive role. He started out quiet, diffident, messes it up when he tries to speak up for himself, throws a tantrum worthy of a 5 year old in front of the whole polis. He’s now kicking his friend to make him hurry, compelling compliance with force, evaluating prophecies, reading political situation (at Nestor’s), making plans, and taking charge.

That is, he did 20 years of growing up in the span of 20? 40? days.

Which is kind of interesting, some ancient Archean groups send boys away from home/ civilization for years before they are “initiated” into society as adults. I wonder if “Mentor” taking Telemachus away for him to come back transformed and mature represents that.

“If Eurymachus really does care about Telemachus, and he was dandled on the knee ow Odysseus, why is he so involved in the despoiling of his house with the other suitors? “

“If Eurymachus really does care about Telemachus, and he was dandled on the knee ow Odysseus, why is he so involved in the despoiling of his house with the other suitors? “Despite his fine words, Eurymachus doesn’t care about Telemachus or his obligation to Odysseus. He’s just been plotting Telemachus’s death via ambush at sea. After Eurymachus’ hypocritical remarks to Penelope about how Telemachus has nothing to fear from him, Homer says “Blasphemous lies in earnest tones he told—the one who planned the lad’s destruction.” (Fitzgerald translation)

I thought it was interesting here that Penelope addressed Antinoos, whose family was sheltered from its enemies by Odysseus, but it is Eurymachus who replies. Is he stepping in to help out Antinoos?

It certainly emphasizes that they are in this siege of the household together. .

Are all lies the same? Often in these two books, it seems to me Odysseus is lying to protect himself and his family’s interests, so maybe it is just as well that he’s good at it. Similarly, lying to Polyphemus about the boat being wrecked in a prior book preserved the lives of Odysseus and those of his men who escaped from the cave. (This was misposted to last week’s discussion by mistake—meant for this week’s reading)

Are all lies the same? Often in these two books, it seems to me Odysseus is lying to protect himself and his family’s interests, so maybe it is just as well that he’s good at it. Similarly, lying to Polyphemus about the boat being wrecked in a prior book preserved the lives of Odysseus and those of his men who escaped from the cave. (This was misposted to last week’s discussion by mistake—meant for this week’s reading)

Everyman wrote: "Helen interprets this as an omen that Odysseus is about to swoop down on his home and deal with the suitors. (Does anybody else think that this is a pretty far-fetched interpretation of the eagle?)"

Everyman wrote: "Helen interprets this as an omen that Odysseus is about to swoop down on his home and deal with the suitors. (Does anybody else think that this is a pretty far-fetched interpretation of the eagle?)"I don't know if it's far-fetched, ancient prophecies interpretation often seem strange to me. But Helen is actually a goddess, so I'm inclined to think there's something to it.

With that said, what caught my attention is how Helen interrupted Menelaus when he was about to give a consequential, political, religious speech -- all public functions that were exclusively in the male domain. If this were in Ithaca, Telemachus would have scolded her and sent her to her room to work the loom. It's pretty clear who "wears the pants" in the blessed Menelaus household.

Everyman wrote: "If Eurymachus really does care about Telemachus, and he was dandled on the knee ow Odysseus, why is he so involved in the despoiling of his house with the other suitors?"

Everyman wrote: "If Eurymachus really does care about Telemachus, and he was dandled on the knee ow Odysseus, why is he so involved in the despoiling of his house with the other suitors?"I think this paints a picture of how far gone the political situation is in Ithaca, and how depraved the suitors really are. It also seems to support claims that Odysseus was gentle and father-like to his subjects before sailing to Troy, and this perversion of debts of gratitude is what gentle, benevolent rules get him.

There was also an omen of two eagles at the assembly meeting in Ithaca, Book 2, which was interpreted by one old lord as meaning Odysseus was returning and would seek vengeance on the suitors. Eurymachos dismissed it: "Old man, go tell the omens for your children at home, and try to keep them out of trouble. I am more fit to interpret this than you are. Bird life aplenty is found in the sunny air, not all of it significant." Time will tell.....

There was also an omen of two eagles at the assembly meeting in Ithaca, Book 2, which was interpreted by one old lord as meaning Odysseus was returning and would seek vengeance on the suitors. Eurymachos dismissed it: "Old man, go tell the omens for your children at home, and try to keep them out of trouble. I am more fit to interpret this than you are. Bird life aplenty is found in the sunny air, not all of it significant." Time will tell.....

“Why does Eumaeus lie about Odysseus to Telemachus?” Interesting question, but I’m not sure where this happened. Can you say more?

“Why does Eumaeus lie about Odysseus to Telemachus?” Interesting question, but I’m not sure where this happened. Can you say more?

A couple of signs indicating Telemachus' growth:

A couple of signs indicating Telemachus' growth:He seems a bit of a realist not wanting to leave things to chance when Odysseus suggests that Athena and Zeus will aid them in killing the suitors:

[16.276] Telemachus answered in his clear-headed way:But shows a confidence in himself he did not seem to have before:

“You’re talking about two excellent allies,

Although they do sit a little high in the clouds

And have to rule the whole world and the gods as well.

[16.326]And Odysseus’ resplendent son answered:

“You’ll soon see what I’m made of, Father,

And I don’t think you’ll find me lacking.

There's a chance that some of the lies Odysseus told came from other versions of Odysseus' return in circulation. Thesprotians, for example, is mentioned in Proclus' summary of the (now lost) Telegony as the place Odysseus has to go to fulfill Tiresias' prophecy.

There's a chance that some of the lies Odysseus told came from other versions of Odysseus' return in circulation. Thesprotians, for example, is mentioned in Proclus' summary of the (now lost) Telegony as the place Odysseus has to go to fulfill Tiresias' prophecy.

David wrote: "Is professing to killing a man really the best way to make good first impression and ask for help from strangers?

David wrote: "Is professing to killing a man really the best way to make good first impression and ask for help from strangers?First it was Odysseus to a disguised Athena:

I’ve been on the run

Since killing..."

I think the Cretan Lie #1 to Athena is just a good way to emphasize how far he will go to protect his loots, without giving away his identity to a stranger, in order to recruit "him" for help. Fast runners are sometimes associated with thievery (Hermes, for example.) He's saying he's willing and able to over power them.

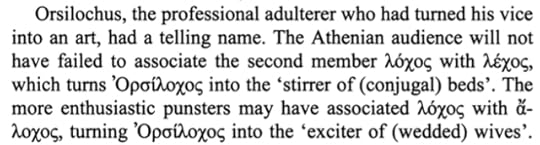

Another interesting thing is that the etymology of the name "Orsilochus" might suggest seducer and adulterer. This is in the context of a much later play by Aristophanes (source: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41756399):

I can't type in Greek... yet. Here's a screenshot

IF that is true, if the name Orsilochus suggests threat to marriage beds, it's possible that Odysseus is covertly expressing his desire to kill suitors by telling a mythical tale about killing adulterers. Demeter also told Cretan Lies that are not literal truth but covertly indicate her nature:

Demeter appears in disguise and tells a tale in which she comes from Crete [...] Like Odysseus, Demeter gives herself a name that points to her true nature and presages her epiphany

Source: https://chs.harvard.edu/CHS/article/d...

Maybe this is just a poetic strategy to tell the audience what is happening, without having the character reveal his true identity.

Lia wrote: "Is anybody else ... surprised? To discover that Odysseus has a sister?"

Lia wrote: "Is anybody else ... surprised? To discover that Odysseus has a sister?"Yes, I was. And the only way we find out is from Eumaeus!

Everyman wrote: "Homer calls Eumaeus “a leader of men.” Isn’t this a bit strange for a swineherd? "

Everyman wrote: "Homer calls Eumaeus “a leader of men.” Isn’t this a bit strange for a swineherd? "If Eumaeus’ story is true, then he is the prince of an island kingdom called “Syrie”. (Wilson called the place Syria, but I doubt Homer / Eumaeus thought Syria was an island.)

I suppose princes are brought up to govern men, not pigs. This epithet also reminds me of Agamemnon, “shepherd of the people”

Speaking of Syrie, it’s really interesting that Eumaeus said his homeland is next to Ortygie. Homeric Hymn to Apollo said Apollo and Artemis were born, one on Ortygie, the other on Delos. (Don’t ask me how can twins be born in different places...) Maybe prince Eumaeus was born to stand besides some archery-deity...

Also, that makes Eumaeus a foreigner, and Odysseus the host. Eumaeus doesn’t know it yet (or does he?), but Odysseus is playing good host by inducing him to tell his own story, just like Alcinoos played good host by inducing Odysseus to sing his own tales.

Susan wrote: "Lia wrote: "Is anybody else ... surprised? To discover that Odysseus has a sister?"

Susan wrote: "Lia wrote: "Is anybody else ... surprised? To discover that Odysseus has a sister?"Yes, I was. And the only way we find out is from Eumaeus!"

I am skeptical because i cannot find another resource for it, but Wikipedia indicates that Odysseus' sister, Ctimene, was married to none other than Eurylochus, who ran back to tell Odysseus about Circe turning the men into pigs, and later incited the men to eat Helios' cattle. It seems brother-in-laws were liabilities back then too.

David wrote: "I am skeptical because i cannot find another resource for it, but Wikipedia indicates that Odysseus' sister, Ctimene, was married to none other than Eurylochus..."

David wrote: "I am skeptical because i cannot find another resource for it, but Wikipedia indicates that Odysseus' sister, Ctimene, was married to none other than Eurylochus..."Wikipedia seems to be right.

Jenny Marsh's meticulous "Cassells Dictionary of Classical Mythology" indicates that Ctimene was indeed "Daughter of LAERTES and ANTICLEIA, and younger sister of ODYSSEUS. She married EURYLOCHUS. [Homer, Odyssey 10.441, 15.363-4.]"

(The capitals indicate cross-referenced articles).

The same Eurylochus is definitely married to Ctimene, and he is the one who came back from Circe's home, who urged landing on Thrinakia, and eating the cattle of the Sun -- covered, with references, in his much longer entry in the same reference book.

Cphe wrote: ""I'll never find a master as gentle as he was, no matter where I go"

Cphe wrote: ""I'll never find a master as gentle as he was, no matter where I go"Was somewhat taken aback to see O referred to as gentle in his dealings with someone outside of Penelope or his son. Doesn't qu..."

He’s been really gentle to his crew: he did not force them to leave Ismaro after sacking the city; he did not punish them when they opened the bag of wind; he took risks to save them from Circe when her brother in law wanted to just abandon them and escape, when he got to the pig pen he saw that he was like a mother to them. He relented when they didn’t want to sail in the dark and insist to land on Helios’ Island. When mediating between Agamemnon and Achilles, he deliberately omitted the harsh, coercive words of Agamemnon, maybe he was only being diplomatic, but harshness didn’t seem to be his style. Athena needed to keep Achilles in check; Odysseus had always checked himself. Even in Cyclope’s cave, where Polyphemus abused and cannibalized his men, Odysseus desired to kill him, but held his emotion in check and only blinded him (and took his sheep.) Seems moderation had always been Odysseus’ strength.

Mentor, Athena and IIRC, either Nestor or Menelaus have all said he was a gentle King, like a father. Athena explicitly requested Zeus to let Odysseus be gentle no more — the transformation of gentle fatherly rule into tyranny seems to be part of the divine plan.

Ominously, when Telemachus asked Athena what’s her business when he hosted her as his guest, Athena sort of lied by saying she’s trading bronze/ iron. Maybe Athena is here to usher in the harsh, bloodly Iron Age.

Lia wrote: "Seems moderation had always been Odysseus’ strength..."

Lia wrote: "Seems moderation had always been Odysseus’ strength..."That is not at all the image I have of Odysseus.

Tamara wrote: "Lia wrote: "Seems moderation had always been Odysseus’ strength..."

Tamara wrote: "Lia wrote: "Seems moderation had always been Odysseus’ strength..."That is not at all the image I have of Odysseus."

Well, my point is that according to Homer, the gods (esp Athena) are deliberately transforming Odysseus from gentle fatherly king into something else. Many characters have said he used to be gentle, we also saw some of that in his interactions with his crew. I expect to see brutality to his OWN subjects after Athena’s interventions (i.e. post Calypso), but up until that point, his brutality was mostly against enemies, unlike Achilles, for example, who didn’t mind praying for the demise of the Greeks as long as it highlights his worth.

In our discussion of Book 9 (#17), I said the following, which I guess bears repeating:

In our discussion of Book 9 (#17), I said the following, which I guess bears repeating:I think Odysseus shows his true colors in this book. He reveals more of himself than perhaps even he is aware. The book is riddled with irony.

Odysseus admits he and his men sacked the Cicones in Ismarus, killing men, dividing up spoils, and enslaving the women. When the Cicones defend themselves, Odysseus cries, “Poor us!”

He accuses the Cyclops of being “giants, louts, without a law to bless them” (Fitzgerald). This is ironic coming from an individual who has just admitted to plundering and thieving and killing.

It is ironic that Odysseus tries to depict himself as the protector of his men when he is actually the one responsible for causing many of their deaths. There are numerous occasions when his crew urge him to exercise restraint, but he refuses to heed their advice. They suggest stealing the cheese and lambs from the Cyclops and escaping before he returns. Odysseus refuses. His delay in departure causes the loss of some of his crew.

His arrogance gets the better of him when he taunts Polyphemus and reveals his name. This brings about the loss of more men and ships.

He may be trying to impress his audience with his "cleverness," but what comes across is his distorted self-image and his belief he can act with impunity.

I fail to see anything "gentle" or "fatherly" in his behavior.

Ismaro was in alliance with Troy, sacking it was the tail end of the Trojan War, he probably inflated his aggressions to make himself seem more dangerous to the Phaeacians, much like he bragged about killing someone he didn’t to Athena. I think treatment of enemies in war does not define your character as a ruler of your subjects. Having children of your subjects sitting on your knees, bringing up foreign slaves with your own children, his crew reacting (in Circe’s) as though they have already returned home when Odysseus came to fetch them, letting his crew choose the cowardly route of staying by the water while he brave Circe’s enchantment alone, not punishing them after major misbehavior like eating the cattle of the sun etc, are what made me think he was like a father to his subjects.

Ismaro was in alliance with Troy, sacking it was the tail end of the Trojan War, he probably inflated his aggressions to make himself seem more dangerous to the Phaeacians, much like he bragged about killing someone he didn’t to Athena. I think treatment of enemies in war does not define your character as a ruler of your subjects. Having children of your subjects sitting on your knees, bringing up foreign slaves with your own children, his crew reacting (in Circe’s) as though they have already returned home when Odysseus came to fetch them, letting his crew choose the cowardly route of staying by the water while he brave Circe’s enchantment alone, not punishing them after major misbehavior like eating the cattle of the sun etc, are what made me think he was like a father to his subjects.The Polyphemus story is probably as famous as the Wooden Horse story, it’s a large % of Odysseus’s kleos. Wanting to meet foreigners in itself isn’t a bad choice, gift exchange implies making alliances. He took a risk and it turned out badly, but they wouldn’t know until he tried. And now they have more knowledge about the world, and Odysseus earned fame, it wasn’t a pure negative outcome. Also, trying to form alliances and by visiting strangers in their home and participate in gift exchange doesn’t make him a not-fatherly ruler. Some fighters in the Iliad refused to fight each other when they realized their ancestors hosted each other and exchanged gifts. If it turns out well, it could be a great boon.

I think the stubborn insistence to taunt him after Polyphemus punned Odysseus’s false name as “good for nothing” and calling him a “weakling” — that is, conflating ‘metis’ (the mind, the strategist, the Athena/ Odysseus type warrior) with “weakness” and “good for nothing” — is something worth picking fight over. Especially since that was after Polyphemus ate his crew. He didn’t stop being heroic, his way of achieving heroic outcome is by tricks and by temporary endurance, temporary in the sense that eventually he’ll invert the situation and come out on top, disproving “good for nothing” and “weakling” which Polyphemus conflated with Odysseus’s identity.

Also, verbal spats seem like a kind of ritualized exchange in Classical Greek literature. Even the “nice” Phaeacians cajoled Odysseus. He engaged in mutual insults with Polyphemus and came up on top, that still doesn’t take away from the fatherly-relationship with his subjects.

I think gentle is a relative term. Odysseus' own mother calls him gentle:

I think gentle is a relative term. Odysseus' own mother calls him gentle:No, it was longing for you, my glorious Odysseus,But just prior to that they discuss the question of dying by Artemis' gentle shafts:

For your gentle heart and your gentle ways,

That robbed me of my honey-sweet life.’

The keen-eyed goddessThere are also the several instances of weeping, which, according to Socrates, roles models (gods or god-like heroes) should not be shown to complain or cry.

Did not shoot me at home with her gentle shafts,

Odysseus seems to make full use of the continuum from gentle to harsh and one might argue specific cases whether he did so appropriately or not, for mistakes were made but not everyone can follow a hero; especially a complicated one.

Cphe wrote: ""I'll never find a master as gentle as he was, no matter where I go"

Cphe wrote: ""I'll never find a master as gentle as he was, no matter where I go"Was somewhat taken aback to see O referred to as gentle in his dealings with someone outside of Penelope or his son. Doesn't qu..."

I think we have to look at the context because Odysseus is a fairly well-rounded character, perhaps the most "realistic" character in Homer. It is Eumaeus who calls him gentle, and by all accounts he has been gentle and father-like with him. He hasn't always been as gentle with others (I think of Dolon in the Iliad. Decidedly not gentle.)

I think Lia is partly right about Odysseus being transformed (@29), but I think Odysseus is actually on his way back to becoming the fatherly king. One of the things Homer is doing is showing a man in transition from war to peace, and the transition is anything but easy for a man as sophisticated as Odysseus. One would think that it would be easy for a king who was reluctant to fight in the first place to simply lay down arms and go home, but a return to gentle domesticity is not easy. It's almost like another war. In a lot of ways I think this is what the Odyssey is ultimately about -- it's an epic metaphor for what soldiers go through when they have to give up the battle. And a lot of it still rings true today.

Thomas wrote: "...but a return to gentle domesticity is not easy. It's almost like another war. In a lot of ways I think this is what the Odyssey is ultimately about -- it's an epic metaphor for what soldiers go through when they have to give up the battle. And a lot of it still rings true today..."

Thomas wrote: "...but a return to gentle domesticity is not easy. It's almost like another war. In a lot of ways I think this is what the Odyssey is ultimately about -- it's an epic metaphor for what soldiers go through when they have to give up the battle. And a lot of it still rings true today..."That's a really good observation. I hadn't thought of it in quite that way. Thank you, Thomas.

If I understand you correctly, Thomas (@33), what you're suggesting is Odysseus pre-war is fatherly. He is brutalized by the war and has a hard time shedding his "war" mentality after the war is over. He struggles to get back to what he was pre-war, but it is a long and difficult journey with many twists and turns and numerous lapses.

If I understand you correctly, Thomas (@33), what you're suggesting is Odysseus pre-war is fatherly. He is brutalized by the war and has a hard time shedding his "war" mentality after the war is over. He struggles to get back to what he was pre-war, but it is a long and difficult journey with many twists and turns and numerous lapses.Did I understand you correctly?

Tamara wrote: "If I understand you correctly, Thomas (@33), what you're suggesting is Odysseus pre-war is fatherly. He is brutalized by the war and has a hard time shedding his "war" mentality after the war is ov..."

Tamara wrote: "If I understand you correctly, Thomas (@33), what you're suggesting is Odysseus pre-war is fatherly. He is brutalized by the war and has a hard time shedding his "war" mentality after the war is ov..."Yes, I think that's the long view. I'm not sure that it is a return to gentleness exactly, but it is a return to domestic stability, which is hard to achieve with a "war" mentality.

Thank you, Thomas. That's a very interesting interpretation--one I had not considered before. I think it works well.

Thank you, Thomas. That's a very interesting interpretation--one I had not considered before. I think it works well.

Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming by Jonathan Shay looks like it might be a good treatment of the analogy. One review of the book states this

Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming by Jonathan Shay looks like it might be a good treatment of the analogy. One review of the book states thisThe book is timeless. Although it explicitly deals with a hypothetical connection between the Greek experience of war, as found in the classic tale of Odysseus, and the more recent experiences of veterans of the Vietnam War, it goes without saying that the lessons learned are applicable to today’s military as well. This, in fact, is the author’s ultimate goal.I think someone else in the group hit close to this mark earlier when they suggested Odysseus might have PTSD.

http://www.historynet.com/odysseus-in...

Cphe wrote: "I see those events as more strong/good leadership.......in war......for the times depicted ........perhaps it was a poor choice of word..."

Cphe wrote: "I see those events as more strong/good leadership.......in war......for the times depicted ........perhaps it was a poor choice of word..."That’s interesting, I thought some of that showed poor leadership — he should have been more firm with his crew, then they would have escaped without suffering Ciccione’s counterattack, they would have arrived home early without being blown all the way back; they would have endured the hunger (Odysseus endured it, it’s not like they were dying from starvation, it was merely unpleasant.) without committing the profane act of eating the cattle of the Sun. If only he were more “brutal,” if only his crew feared/ respected him more...

But we basically have very little data on how he ruled — we heard the same “gentle fatherly” description from Athena, Mentor (not Athena in disguise I believe), either Nestor or Menelaus, and now Eumaeus. We’ve heard from a suitor that he used to sit on Odysseus’s lap as a boy. We know that Ithacan were able to operate without a King for 20 years, some suggest that shows Odysseus set things in good order before he left for war. Other than that, we have no way of knowing what he was like “pre-PTSD.”

Thomas wrote: "I think Odysseus is actually on his way back to becoming the fatherly king..."

I suppose we will have to wait to see how he handles the political situation at home to find out. So far we have seen him interact with a goddess, a slave, and his son. Phaeacians weren’t his subjects so we can’t judge his ruler-style based on his behavior there. We will have to see how he settles scores, how he irons out the messy situation Ithaca is in, what course he sets Ithaca on once he is reinstated.

Cphe wrote: "A lot of times O's actions were one of expediency. He "could" have had a mutiny on his hands.

Cphe wrote: "A lot of times O's actions were one of expediency. He "could" have had a mutiny on his hands.I always thought his bottom line was to return home ASAP in one piece. In that context his leadership ..."

The near-mutiny was incited by Eurylochos (~lochos again, look at the word-root comment in @20, “lochos” means to stir up...)

In book 10, when Eurylochos was already trying to turn his crew against Odysseus. Odysseus contemplated killing him with his sword, despite being relative by marriage (Odysseus’ sister married him.)

If Odysseus were a harsher ruler, he could have rightfully executed Eurlochos at that point, thus removing the usurping element, which would have been the more expedient thing to do.

David wrote: "Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming by Jonathan Shay looks like it might be a good treatment of the analogy. One review of the book states th..."

David wrote: "Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming by Jonathan Shay looks like it might be a good treatment of the analogy. One review of the book states th..."I read Shay's book on the Iliad and thought it was brilliant. I haven't read this one, but it's been on my TBR shelf for a few years. I'm sure it's very good.

Why do Odysseus and Telemachus weep when Odysseus reveals himself? The scene is one of heartfelt lamentation and sorrow, not joy.

Why do Odysseus and Telemachus weep when Odysseus reveals himself? The scene is one of heartfelt lamentation and sorrow, not joy. With that, he sat back down. Telemachus

hurled his arms round his father, and he wept.

They both felt deep desire for lamentation,

and wailed with cries as shrill as birds, like eagles

or vultures, when the hunters have deprived them

of fledglings who have not yet learned to fly.

That was how bitterly they wept. Their grieving

would have continued till the sun went down,

but suddenly Telemachus said, "Father,

by what route did the sailors bring you here, to Ithaca?" (16.214-224, Wilson trans.)

Why is this homecoming a time for grieving?

Thomas wrote: "Why is this homecoming a time for grieving? "

Thomas wrote: "Why is this homecoming a time for grieving? "This reminds me of how Circe did not understand her “pigs” are actually human inside. Sometimes god, qua god, fail to comprehend what it means to be human, and what matters to human.

Athena callously told Odysseus that she knew he would get home sooner or later, so who cares if she waited 10 years before stepping in? You come home in 10 years, or home in 20, it’s all the same, right?

Except as human with finite time, it matters. Odysseus imagined coming home to the baby he left behind, instead he found a grown man, raised by others. Yes, he’s home, but lost time cannot be recovered. Penelope can undo her weave to suspend progress of events, but even so, she cannot turn back time. And I think THAT’s what they are grieving.

David wrote: "Is professing to killing a man really the best way to make good first impression and ask for help from strangers?

David wrote: "Is professing to killing a man really the best way to make good first impression and ask for help from strangers?First it was Odysseus to a disguised Athena:

I’ve been on the run

Since killing..."

You know how Menelaus lectured his doormen about reciprocity in hosting guests? Like, the motivation for being a good host is that one hopes to be treated well as a stranger when traveling?

I wonder if Telemachus treats a murderer-exile well because he’s plotting to murder someone (one?) from his own tribe. And he’s hoping for reciprocity when/ if he’s exiled for it.

And maybe Odysseus is testing the water to see how murder-exiles are treated around this neck of the woods...

More signs of Odysseus’s “gentle rule”, Penelope said to Antinous:

More signs of Odysseus’s “gentle rule”, Penelope said to Antinous:Have you forgotten that your father came here,

running in terror from the Ithacans,

who were enraged because he joined the pirates

of Taphos, and was hounding the Thesprotians,

our allies? So the Ithacans were eager |430|

to kill him, rip his heart out, and devour

his wealth. Odysseus protected him!”

Antinous himself replies

I swear to you, if someone tries, my sword

will spill his blood! Your city-sacking husband

often would take me on his lap, and give me

tidbits of meat with his own hands, and sips

of red wine.

My first thought is: like father, like son. His father back-stabbed their treaty-allies by attacking the Thesprotians. The Ithacans demanded justice by killing him, Odysseus gave him protection. And now, it’s the son’s turn to back-stab his benefactor.

But then, Odysseus fed a small boy wine! Isn’t that child-abuse?

Cphe wrote: ""You surely are a god, a heaven dweller" ......Mandlebaum when O is first sighted by his son.

Cphe wrote: ""You surely are a god, a heaven dweller" ......Mandlebaum when O is first sighted by his son.The gods here are anything but "heavenly", they are quite capricious in their deeds and manipulations..."

I don’t think Telemachus was saying that he must be “good”, he only wanted to acknowledge he must be magically powerful — he can change his appearance at will. He even lowered his head and acted fearful.

I don’t think heaven connotes moral goodness here.

Lia wrote: "This reminds me of how Circe did not understand her “pigs” are actually human inside. Sometimes god, qua god, fail to comprehend what i..."

Lia wrote: "This reminds me of how Circe did not understand her “pigs” are actually human inside. Sometimes god, qua god, fail to comprehend what i..."Could you please show the lines that indicate Circe did not understand her pigs are actually human inside? I've read the section several times and cannot find any indication she wasn't aware they are human inside.

Tamara wrote: "Lia wrote: "This reminds me of how Circe did not understand her “pigs” are actually human inside. Sometimes god, qua god, fail to comprehend what i..."

Tamara wrote: "Lia wrote: "This reminds me of how Circe did not understand her “pigs” are actually human inside. Sometimes god, qua god, fail to comprehend what i..."Could you please show the lines that indicat..."

I apologize, my phrasing came out wrong. What I meant was that Circe learned compassion from Odysseus, she was *moved*, a god who effortlessly knows the nature of things, a god who knows the future and knew Odysseus was coming, who knew what Odysseus must do to return home. A know-it-all got schooled by a mortal, that’s what I was trying to emphasize. Until Odysseus put his distress on display for her to see, she cannot comprehend there’s anything wrong with penning his men up in the sty. For the deathless gods, as long as they are kept alive, fed, kept safe, it makes no difference whether they look young or old, like pigs or humans, it’s all the same.

Zeus said as much —Poseidon is only going to hurt Odysseus, as long as he doesn't kill him then all is well.

Only fellow humans comprehend the significance of these small matters that don’t even register to the deathless ones. Achilles’ tragedy is that he came to comprehend these small matters too late, only when Priam came to his tent did he understand he belongs to the mortals, and share in their sufferings. What makes Odysseus stand out is the fact that he acknowledges, comprehends and defends that at every step, rejecting immortality, vehemently grieving the loss of every small things that make mortal human life good.

Really interesting points about the "transformation" of Odysseus. It reminds me of stories of Cúchulainn in Irish mythology: when he returns from battle, he is so fired up he will kill basically anyone who crosses his path, friend or foe; to calm him down, the women of the town go out to meet him naked, and the men thrust him into barrels of cold water. The idea is apparently that the fierce warrior who saves the community by his violent rage also becomes a danger to the community unless he is successfully "re-domesticated."

Really interesting points about the "transformation" of Odysseus. It reminds me of stories of Cúchulainn in Irish mythology: when he returns from battle, he is so fired up he will kill basically anyone who crosses his path, friend or foe; to calm him down, the women of the town go out to meet him naked, and the men thrust him into barrels of cold water. The idea is apparently that the fierce warrior who saves the community by his violent rage also becomes a danger to the community unless he is successfully "re-domesticated."

Rex wrote: "The idea is apparently that the fierce warrior who saves the community by his violent rage also becomes a danger to the community unless he is successfully "re-domesticated..."

Rex wrote: "The idea is apparently that the fierce warrior who saves the community by his violent rage also becomes a danger to the community unless he is successfully "re-domesticated..."That’s a really good point. It also reminds me of the inherently amoral nature of Herakles’ “heroism” — he can be a good gift, and he can be an evil gift. Ultimately he “labours” with his strength; he also “endures” much — just like Odysseus. It seems like many heroic tales share the same theme of the “two-faced” nature of heroism.

"Rex wrote: "The idea is apparently that the fierce warrior who saves the community by his violent rage also becomes a danger to the community unless he is successfully "re-domesticated..."

"Rex wrote: "The idea is apparently that the fierce warrior who saves the community by his violent rage also becomes a danger to the community unless he is successfully "re-domesticated..."Just as an FYI, the same idea is evident in the Eastern traditions. For example, in the Devi Mahatmya: The Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition, the goddess Kali is called upon to assist Candika in the battle against the demon Raktabija. Raktabija is endowed with the ability to create an exact replica of himself with each drop of blood that falls from his body. Kali devours the blood before it touches the ground. She wins the battle on behalf of Candika but she gets caught up in the activity, wreaking havoc without stopping. The intervention of an outside agent, usually Shiva, is the only thing that stops her.

Books mentioned in this topic

Eve of the Festival: Making Myth in Odyssey 19 (other topics)Devi Mahatmya: The Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition (other topics)

Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming (other topics)

Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming (other topics)

Authors mentioned in this topic

Jonathan Shay (other topics)Jonathan Shay (other topics)

We jump back to Telemachus, whom we last saw in Book 4. Athena comes to tell him to hurry home, to watch out for a trap the suitors are setting for him, and to visit the home of the swineherd Eumaeus. As Telemachus is about to leave Sparta, an eagle carrying a goose swoops down by him. Helen interprets this as an omen that Odysseus is about to swoop down on his home and deal with the suitors. (Does anybody else think that this is a pretty far-fetched interpretation of the eagle?)

Meanwhile, Odysseus and Eumaeus discuss the past with each other until Telemachus reaches Eumaeus’s hut where he meets a stranger who he doesn’t recognize as his father (which makes sense; he was, what, 2 when his father left home? And no photo album to look through for pictures of him.) Eumaeus tells Telemachus the stranger’s story, then goes to the palace to tell Penelope that her son has returned safely, while Odysseus reveals himself to Telemachus and they plot the destruction of the suitors.

There were a few things I found curious.

Athena tells Telemachus ““Telemachus, thou dost not well to wander longer far from thy home, leaving behind thee thy wealth and men in thy house so insolent, lest they divide and devour all thy possessions, and thou shalt have gone on a fruitless journey.” Why fruitless when he learned so much? And why did she send him in the first place if she didn’t think the information he would get would be fruitful?

Then she says “For thou knowest what sort of a spirit there is in a woman's breast; she is fain to increase the house of the man who weds her, but of her former children and of the lord of her youth she takes no thought, when once he is dead, and asks no longer concerning them.” Does Homer really believe that a woman who remarries forgets all about her children from the first marriage? But maybe that’s how it was in Greek society?

In Book 16, around line 35, Homer calls Eumaeus “a leader of men.” Isn’t this a bit strange for a swineherd?

Why does Eumaeus lie about Odysseus to Telemachus?

If Eurymachus really does care about Telemachus, and he was dandled on the knee ow Odysseus, why is he so involved in the despoiling of his house with the other suitors?