Essays discussion

Arthurian

>

Merlin and The Crystal Cave

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Niniane's singleminded protection of Merlin from her brother is a bit like Penelope protecting Telemachus from her suitors.

Lia wrote: "The special boy and the teacher in the cave really reminds me of Chiron training Achilles. ... What is with Cedal's sign against Merlin's "evil eye"? "

Lia wrote: "The special boy and the teacher in the cave really reminds me of Chiron training Achilles. ... What is with Cedal's sign against Merlin's "evil eye"? "Stewart's teacher for Merlin is something of an innovation, and an ingenious one.

In medieval texts, Merlin either has inexplicable sources of information, simply beyond human ken, or he specifically received demonic knowledge of the past from his supernatural father, and of the future from God -- such specificity being one of Robert de Boron's contributions to Geoffrey's story.

In de Boron, Merlin has a Confessor, the wise Blaise (or Blase, etc.) to whom he periodically reports events, but the adult is from the start the infant Merlin's student....

Almost every culture that has been studied in this regards seems to know of something like the "evil eye," a power produced by malice, or just jealousy, and not always in control of the person who has it. It is usually thought to be transmitted by the power of sight. Anyone who seems strange or just "different" may be suspected of having such power. Merlin certainly seems to fit in that category.

Accompanying such beliefs is usually a repertoire of gestures and actions to "ward off" such malevolent power. (Also colors and designs -- some very attractive geometric art is probably strictly utilitarian in origin.

By the way, there is a theory that Gorgons were not originally held to possess horrific faces that turned people to stone, but had the evil eye -- hence Perseus use of a mirror shield to neutralize Medusa's gaze by throwing it back at her. (Using a mirror as a guide to cutting off someone's head is pretty complicated, and would probably take a lot of practice to learn how to work in mirror-image reverse.)

One of the classical Greek theories of vision was that rays emanated from the eyes and bounced back to them, like radar: this would give a "scientific explanation" of how the evil eye transferred power to its target. (How they accounted for the rays failing in darkness is a but obscure -- presumably light played some enabling function.)

That's really fascinating. The "vision beyond human ken" sounds a bit like those blind bards who can somehow see higher "truths", like Homer's mysterious power to visualize Achilles' shield when most mortals are driven mad by the sight of it.

I did know about Gorgons' laser-eyes theory! I read it as a unique superpower, I didn't realize it could represent something more pervasive in their culture.

I did know about Gorgons' laser-eyes theory! I read it as a unique superpower, I didn't realize it could represent something more pervasive in their culture.

They took away his torn, wet princeling clothes. He is nekkied under his blankets

Not unlike Odysseus stripping Ino’s headpiece / dramatically throwing off his beggar’s costume to full nudity in front of the suitors.

Maybe it’s yet another death-rebirth motif? (Merlin even “plunged” and fell on his side as he struggled to climb out of the boat — another dive-towards-water-before-rebirth motif?)

“I threw the blankets off and sat up. With the ceasing of the dreadful motion of the ship I felt steady again -- even well, with a sort of light and purged emptiness that gave me a strange feeling of well-being, a floating, slightly unreal sensation, like the power one has in dreams”

Not unlike Odysseus stripping Ino’s headpiece / dramatically throwing off his beggar’s costume to full nudity in front of the suitors.

Maybe it’s yet another death-rebirth motif? (Merlin even “plunged” and fell on his side as he struggled to climb out of the boat — another dive-towards-water-before-rebirth motif?)

“I soon learned that the way to dodge his sarcasms and his heavy hand was to do my work quickly and well, and since this came easily to me and I enjoyed it, we soon understood one another, and got along tolerably well.”

I hope he’s not another one of those magical Mary Sue.

When young Merlin recognized and acknowledged his father, and called him “Sir,” I thought he was being snarky. But then I started reading Tolkien:

Turns out it’s normal for medieval children. I’m pretty impressed with Stewart’s attn to minor details like this.

she addresses her father formally as sir, and shows no filial affection for him. But this is an apparition of a spirit, a soul not yet reunited with its body after the resurrection, so that theories relevant to the form and age of the glorified and risen body do not concern us. And as an immortal spirit, the maiden’s relations to the earthly man, the father of her body, are altered. She does not deny his fatherhood, and when she addresses him as sir she only uses the form of address that was customary for medieval children.Source: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo

Turns out it’s normal for medieval children. I’m pretty impressed with Stewart’s attn to minor details like this.

Stewart's Merlin is, of course, a product of the fifth century, a little early for High Medieval English customs, but the principal is certainly valid.

Stewart's Merlin is, of course, a product of the fifth century, a little early for High Medieval English customs, but the principal is certainly valid.In what may have been a parallel development, well-brought-up Roman children addressed their grandfathers as "Domini," "My Lord."

I am aware of this custom because the possible perceived political implications of it so worried Augustus that he forbade his own grandchildren (or those filling the role: the family history is quite complicated) from using the term in addressing him.

He was trying to create an hereditary monarchy without actually saying so. And any accretion of titles not "freely" offered him by the Senate and People was to be avoided in any context. This one might have been inflammatory, despite its commonplace nature.

Augustus may have been right. It was alleged that the later emperor Domitian wanted to be called "Domini et Dei," "My Lord and My God." This claim seems to have appeared only in the aftermath of his assassination, and is probably untrue, but does demonstrate the possible political implications of the first term, whether or not part of a claim of divine status. (Technically, the cult of the living emperor seems to have been meant to worship, not the man, but his guardian deity, or "genius," but the distinction seems to have been meaningless outside of the Roman homeland.)

I didn't realize Merlin goes back that far! Thanks for bringing that up.

I wonder if writers/ bards back then worry about matching their language to the era the story is set in. Would they use "older language" to signal "once upon a time?" And what about translation between tribes? Did they all speak English? (Homer's Argives didn't need translators to insult the Trojans, for example.)

I thought Augustus grounded his legitimacy on his hereditary linkage to Aeneas/ Venus, I didn't know he tried to keep quiet about his not-so-secretive monarchy scheme (and what's with choosing an adopted son to inherit the throne if it's based on divine lineage?)

No wonder Ovid loved playing with contradictions and silencing in his poems. I bet he had a lot of fun mocking Augustus' hypocrisy.

I wonder if writers/ bards back then worry about matching their language to the era the story is set in. Would they use "older language" to signal "once upon a time?" And what about translation between tribes? Did they all speak English? (Homer's Argives didn't need translators to insult the Trojans, for example.)

I thought Augustus grounded his legitimacy on his hereditary linkage to Aeneas/ Venus, I didn't know he tried to keep quiet about his not-so-secretive monarchy scheme (and what's with choosing an adopted son to inherit the throne if it's based on divine lineage?)

No wonder Ovid loved playing with contradictions and silencing in his poems. I bet he had a lot of fun mocking Augustus' hypocrisy.

Lia wrote: "I didn't realize Merlin goes back that far! Thanks for bringing that up. ... I thought Augustus grounded his legitimacy on his hereditary linkage to Aeneas/ Venus..."

Lia wrote: "I didn't realize Merlin goes back that far! Thanks for bringing that up. ... I thought Augustus grounded his legitimacy on his hereditary linkage to Aeneas/ Venus..."There was a (possibly) historical Welsh poet (sixth century?) named Myrddin, to be pronounced like 'Mirth-in.' There is a story of his uttering prophecies when he went mad, of uncertain date, but clearly related to Geoffrey's "Vita Merlini," and so at least somewhat older.

When Geoffrey of Monmouth was "translating" his "old British book," the name became Merlin -- probably because when transliterated the Welsh sounded too much like French "merde," for excrement. (We know that Geoffrey knew the Welsh name, because he says that the city of Caer-Merdin -- modern Carmarthen -- was named after Merlin.)

Geoffrey's Merlin gets some of his story from an anecdote about Vortigern and a boy named "Ambrosius," found in the (perhaps ninth century) "History of the Britons" by, or attributed to, a monk named Nennius. Geoffrey simply ignored that the boy is an obvious double for Ambrosius Aurelianus (etc.), predicting his own defeat of Vortigern, and blandly asserted the identity with the poet-prophet instead. If anything like these events (Vortigern, Saxons, etc.) took place it had to be the late fifth century (or, c. 500, the very early sixth), not too long after the Roman withdrawal.

Mary Stewart, as you will have noticed, picked up on the overlapping names, and ran with it.

As for the Romans, Virgil makes a good deal of the Aeneas-son-of-Venus lineage, but the one that was critical for Augustus in his rise to power was his "descent" from his adoptive father; he wanted to be known as "Julius Caesar, son of Julius Caesar," not as Octavianus, which revealed his adoptive status to speakers of Latin.

This was important to the legions, and the Roman masses, few members of which were aware of his real parentage, and the ins-and-outs of patrician lineages, anyway.

The soldiers especially probably wouldn't have been much impressed by the Julian family's divine ancestry, if they were literate enough to learn about it, caring mainly for the descent from their victorious commander. But every little bit helped build up the overall image of legitimacy, while he went around "restoring" the Republic as its First Citizen.

By the way, he ordered the murder of the son of Julius and Cleopatra, eliminating someone with a much better claim to the name than his own.

Lia wrote: "I wonder if writers/ bards back then worry about matching their language to the era the story is set in. Would they use "o..."

Lia wrote: "I wonder if writers/ bards back then worry about matching their language to the era the story is set in. Would they use "o..."Such historical consciousness mostly runs back to Sir Walter Scott, who, according to one continental historian, "taught Europe how to write history." He seems to have invented the systematic exploitation of temporal differences in languages and customs as part of the story-telling, rather than a hindrance.

The tendency in previous centuries, as in the visual arts, had been to modernize: so earlier Arthurian romances feature coats of mail, while late ones, like Malory, seem to assume plate armor as the universal norm. Some eighteenth-century illustrations to French adaptations of Arthurian romances seem to assume that the characters, being gentleman, were using fashionable rapiers, rather than old-fashioned broadswords.

Of course, having everyone speak Greek in Homer is probably a poetic convention, in an artificial dialect meant for hexameter verse. It was simply necessary for the smooth progress of the story. But the likely difference in language may not have impressed itself on the minds of the poets or, especially, their stay-at-home listeners, to begin with. It has been suggested that a systematic distinction between "Hellenes" and "Barbarians" was a product of Ionian clashes with non-Greeks in Asia Minor, rather than an idea they brought with them from the Greek mainland and Aegean islands.

However, by Alexandrian and Roman times, Homeric Greek was certainly recognized as "old-time," and consciously used as an archaism suitable for epic poetry, but not much employed otherwise. (It was, of course, much later than anything that Achilles and company would have been speaking, but the principle remains the same.) The Roman-era satirist Lucian sometimes used the Ionian dialect of Herodotus as a conscious pastiche, which may show at least a rudimentary grasp of languages changing over time -- but he may have been thinking more of geography.

Malory is sometimes a problem in this regards. He claims to know that the story he is telling took place a long time ago, when things were different, but only rarely does this surface in the narrative. (And sometimes to lament the degeneracy of his times, a common medieval idea, although he may have had personal reasons, too.)

His English seems to have been mostly up-to-date, if a bit provincial and conservative, possibly, but not certainly, emphasizing the time difference -- for the most part it is probably pretty much how he spoke. There is archaic vocabulary in the Roman War and, like parts of the Death of Arthur, they seem to be borrowed from an older alliterative poem he was putting into prose, rather than being a deliberate effort to sound like "a long time ago." Caxton, or whoever edited his version, did away with a lot of that, along with the passages containing them, so it apparently didn't impress him as a deliberate feature (rather than a bug....).

However, there are places where Malory seems to have lost the thread of what he was saying, even though the general meaning is clear. The language in such cases often seems stilted, and very formal. (The differences are most noticeable to editors, who have to decide how to punctuate such passages: many readers will never notice.)

This could be due to scribal errors in difficult passages, but, according to source studies, it usually means that he is abridging a longer, showpiece, rhetorical declamation in his Old French source, which was not the colloquial French of his own day (and probably never in common usage at any time -- someone was showing off, in a style much admired at the time.)

Malory evidently didn't have the formal training in rhetoric of the (mainly) thirteenth-century authors he was translating, and had trouble disentangling figures of speech. But he may have kept such passages in part, instead of deleting them entirely, because he regarded them as part of the "old-fashioned" atmosphere.

By the way, Robert Graves, in his introduction to Keith Baines' condensed "Morte D'Arthur," expresses the view that Malory's English was full of rhetoric, to pad out passages, and he was not the first to have such an opinion (Mark Twain made fun of Malory's 'long-winded' speeches, although he should have known better -- Malory's speeches are sometimes "artlessly" colloquial.)

C.S. Lewis pointed out that, on the contrary, Malory is surprising spare in his descriptions, with no "padding" at all, leaving a lot to the reader's imagination: especially compared to most medieval literature. And he gives examples.

The shifting consciousness of time, history and language is so fascinating Ian, thanks for the brief write up.

I thought writers from Ovid to Cervantes were extremely conscious of time (or at least the effect of replacing old calendar system) and its effect on narratives, well before Walter Scott, though I think I remember reading about that remark somewhere too.

About “padding”: it seems like such a random accusation with complete lack of definition. I’ve heard people from literature (but not classics) department calling Homer’s depiction of Achilles’ Shield or Hades “padding”, because they don’t seem to advance the plot in a modern sense.

Gosh, I might have to finish reading SPQR. The Octavian plot is far more conniving than politics in Merlin's (or Stewart's) circle.

I thought writers from Ovid to Cervantes were extremely conscious of time (or at least the effect of replacing old calendar system) and its effect on narratives, well before Walter Scott, though I think I remember reading about that remark somewhere too.

About “padding”: it seems like such a random accusation with complete lack of definition. I’ve heard people from literature (but not classics) department calling Homer’s depiction of Achilles’ Shield or Hades “padding”, because they don’t seem to advance the plot in a modern sense.

Gosh, I might have to finish reading SPQR. The Octavian plot is far more conniving than politics in Merlin's (or Stewart's) circle.

Blood (human) sacrifice and foundation (for buildings) - Ismail Kadare wrote novels based on that too.

Young Merlin’s got the kleos of a bard:

One lie leads to another; together they make plain what the truth would not...

“Berric said it sounded, the lot of it, as true as a trumpet ... “It was all dressed up, like poets' stuff, red dragons and white dragons fighting and laying the place waste, showers of blood, all that kind of thing. But it seems you gave them chapter and verse for everything that's going to happen...”

One lie leads to another; together they make plain what the truth would not...

Lia wrote: "The shifting consciousness of time, history and language is so fascinating Ian, thanks for the brief write up.

Lia wrote: "The shifting consciousness of time, history and language is so fascinating Ian, thanks for the brief write up. I thought writers from Ovid to Cervantes were extremely conscious of time (or at lea..."

Scott's big contribution may have been to reveal that the past was not only full of differences, they were *interesting* differences, which the historian as well as the novelist was free to explore. (Whether Scott ever appreciated the significance of some of what he discovered is another matter; C.S. Lewis, on the whole an admirer, notes that he sometimes seems quite obtuse where religion is involved, liking the telling of beads, etc., but never trying to imagine what the implied set of beliefs would mean to how people behaved.)

Before Scott, a lot of individual writers were conscious of the passage of time as part of the plot, or as a general "distancing effect" on the story (in case someone began reading messages into it), but it is surprisingly hard to find a general grasp that "period" made a difference in people's basic behavior, or that what was familiar today may not have been yesterday. (As Lewis, again, points out, Milton sometimes treats Jesus and his Disciples as if they were sitting down to a typical English meal....)

Gibbon knew that he was quite different from the "barbarians" and the early Christians, but doesn't always seem to be quite as clear that the behavior of a Roman gentleman might have little in common with an eighteenth-century Englishmen or Frenchmen of equivalent rank (other than a sense of privilege).

And when differences are noted by other, mostly lesser, writers, there is usually a sense of self-congratulation that we have escaped those "rude" former times, and are now truly civilized. (Gibbon takes Rome at the height of the Empire as the standard for civilization, so he can't fully exploit this attitude.)

Before Scott arrived on the scene, treatment of the medieval past in particular was often focused entirely on how it related to the present, with no thought that it had any interest in itself.

On the one hand, there was a whole tradition of English historical writing, lasting into the twentieth century (at least) treating England's history as a gradual growth from crude seeds of Anglo-Saxon Liberties, to the peak of (choose your own era in which to write), despite the lamentable, but temporary, impact of the Norman Conquest. For Scott, this inherited notion forms a background element to "Ivanhoe," otherwise just a colorful adventure story with odd laws and customs to entertain the reader.

On the other side of the Channel, it has been said that the French needed to invent feudalism, in order to be able to revolt against it -- a process which probably began with the Absolutists decrying local customs and provincial laws on behalf of the monarchy. If something was demonstrably OLD, then it was BAD. Of course, *The* Revolution inherited this, and, as de Tocqueville pointed out, successfully imposed the sort of centralized authority and uniform legislation that the Kings had only dreamed of. (So Napoleon really was what Louis XIV wanted to be.)

Other European countries had their own paths. In England, relatively liberal institutions were linked to an imagined past, while in much of the rest of Europe medievalism was strongly linked to assertions of national identity, and authoritarian attitudes, not without consequences in the twentieth century.

Some nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century German writers supposed that the British Empire proudly derived its institutions from William the Conqueror -- they may have been right about the Norman source of particular details, but they obviously hadn't been reading much English historiography, or had entirely missed the point of it. One suspects they were trying to find a model for writing German history to show that it reached its consummation in the rule of the Hohenzollern Kaisers.

Ah okay, that makes a lot of sense. Scott did seem to precede the wave of writers who self-consciously highlight their new and improved “modernity”.

It is funny how for centuries, writers seem to lament their “fallenness” and degeneration from a golden-age past. Explicitly so in Homer, in Hesiod, in Ovid, It seems that’s also the case in medieval writings. But then suddenly (or so it seems to me) they’ve collectively decide old = bad! We the enlightened made progress!

But then, just as suddenly, that kind of cockiness is no longer cool. There are so many different attitudes towards the past, I can’t decide which to wear!

It is funny how for centuries, writers seem to lament their “fallenness” and degeneration from a golden-age past. Explicitly so in Homer, in Hesiod, in Ovid, It seems that’s also the case in medieval writings. But then suddenly (or so it seems to me) they’ve collectively decide old = bad! We the enlightened made progress!

But then, just as suddenly, that kind of cockiness is no longer cool. There are so many different attitudes towards the past, I can’t decide which to wear!

Speak of the devil Walter Scott!

most Victorians drew their impressions of the Middle Ages from Sir Walter Scott’s novels rather than from any historical medieval text. As Clare A. Simmons asserts, Victorian medievalism focuses on “the individual’s needs and desires” rather than in “discovering the authentic past.” Thus, everything about this “history” became a matter of interpretation, not an “authentic past” but an authentic fantasy.-Lorretta M. Holloway and Jennifer Palmgren

Victorians embraced all the trappings of this imagined past. Their affinity for the story of King Arthur—so much in their songs, on their stages, and in their poetry—fit how the Victorians imagined and recreated the Middle Ages for themselves. They could make Arthur up or into anything they wanted or needed, and they did.

I really really love how Stewart works images and icons from Greco-Roman cults into the narratives

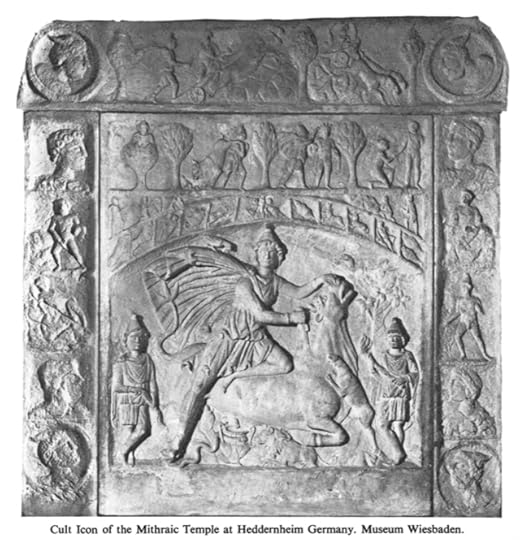

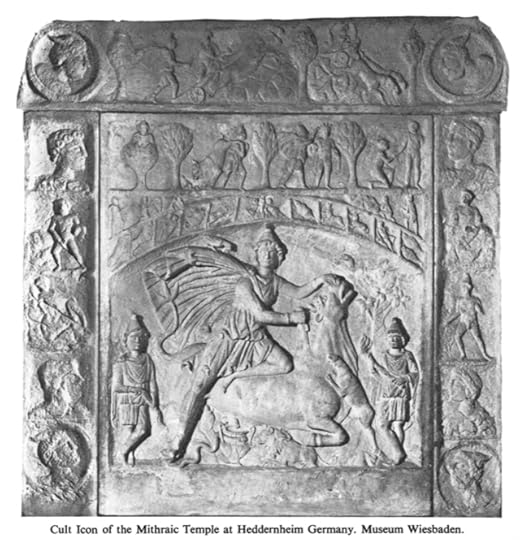

Here's one image of Mithras bull-slaying relief in stone:

Here's one image of Mithras bull-slaying relief in stone:

“In the end I had designed a wooden crib of a kind which a modern engineer might have dismissed as primitive, but which -- as the singer had been my witness -- had done the task before, and would again”.

Such a strange remark, modern as in early modern, like John Donne Shakespeare “modern”? I know Melin says he’s an old man “now” in the frame story, but how old is old? Did he live to see the march towards modernity?

Lia wrote: "“In the end I had designed a wooden crib of a kind which a modern engineer might have dismissed as primitive, but which -- as the singer had been my witness -- had done the task before, and would a..."

Lia wrote: "“In the end I had designed a wooden crib of a kind which a modern engineer might have dismissed as primitive, but which -- as the singer had been my witness -- had done the task before, and would a..."I suspect that Stewart is having Merlin use modern as meaning contemporary -- in his case, late Roman, with the inheritance of centuries of engineering experience, meant to get the job done quickly and efficiently, but sometimes without regard for permanence (which is irrelevant in this case). He is certainly said to have been introduced to such things during the preparations for Ambrosius' invasion of Britain.

In this case, however, he resorts to something workable, even without a lot of trained manpower from the Legions to create it. (In the early Empire, every Roman soldier was supposed to have a second trade, like metal-working or carpentry, to reduce dependence on civilians for help, and keep them occupied in peacetime. That probably didn't apply in the situation Stewart envisions.)

As an example, Roman armies apparently built temporary bridges across the Rhine on several occasions, surprising and (they hoped) frightening the Germans, who considered it a major barrier. (They would have wanted them temporary, to prevent them from being used by the enemy, too. One of the later Germanic invasions is said to have been facilitated by an exceptionally cold winter, which froze a section of the Rhine so solidly that it could be crossed on foot.)

I'm not sure how much thought Stewart gave to the problem, or to the issue of how much of that knowledge survived in 5th-century Gaul. The thread of transmission may have been very narrow, and easily broken. Such things may have been a Roman military specialty, not easily emulated by their foes, and not always familiar to civilians. Roman civil engineers may have relied on lots and lots of cheap manpower in situations where the army had to make do with what their logistics could support in the field. If so, that would mean that the military commanders put a priority on mechanical advantages, like using levers for lifting and moving, instead of lots of slaves. (But they certainly used conscripted worker when they could get them. They weren't teetering on the brink of an industrial revolution.)

Ah okay, I suppose the concept of "modern" was a thing even back in ancient time. They just point to different ideas.

I've said before that I hoped Merlin isn't made into a Mary-Sue -- but it turns out that's sort of the case. The idea that he heard a bard sing a song that alludes to technology, and somehow managed to conjure such engineering contraptions with rudimentary workshop experience is about as unbelievable as magic. (They no doubt heard Homer's song about Phaeacians' hydrofoils, AFAIK nobody had been inspired to build one in ancient time! Imagine the kind of military advantage they will have if they can get Phaeacians' superjets!)

I saw a huge doorstop in the reference section of the library on ancient technology. Those were literally engineering publications with math and formulas and tables, speculating on the constructions of the Trojan Horse and Phaeacian hydrofoils etc. I was shocked that anybody would *want* to read such thing, or write enough on the subject to fill two 600+ pages volumes.

Turns it it's actually pretty fascinating. I hope I'm not turning into a nerd!

I've said before that I hoped Merlin isn't made into a Mary-Sue -- but it turns out that's sort of the case. The idea that he heard a bard sing a song that alludes to technology, and somehow managed to conjure such engineering contraptions with rudimentary workshop experience is about as unbelievable as magic. (They no doubt heard Homer's song about Phaeacians' hydrofoils, AFAIK nobody had been inspired to build one in ancient time! Imagine the kind of military advantage they will have if they can get Phaeacians' superjets!)

I saw a huge doorstop in the reference section of the library on ancient technology. Those were literally engineering publications with math and formulas and tables, speculating on the constructions of the Trojan Horse and Phaeacian hydrofoils etc. I was shocked that anybody would *want* to read such thing, or write enough on the subject to fill two 600+ pages volumes.

Turns it it's actually pretty fascinating. I hope I'm not turning into a nerd!

“she's less than half Gorlois' age and spends her life mewed up in one of those cold Cornish castles with nothing to do but weave his war-cloaks and dream over them, and you may be sure it's not of an old man with a grey beard.”

...“Cadal's last remark came a little too near home for comfort. There had been another girl, once, who had had nothing to do but sit at home and weave and dream...”.

It’s a bit disappointing to see women depicted like that by somewhat contemporary writers. It’s one thing if she was translating some old but established tales. I expected more human and fully formed female characters from a contemporary woman writer spinning her own version of an old tale.

Jesus, he's going to help him impregnate her. I already know where this is going and who that child is going to be, but it's still disappointing that a woman wrote about women as though they were demure baby incubators that are mostly remarkable for bewitching men.

Noobs question for you Ian: how "orthodox" is Stewart's depiction of Uther and Lady Ygraine's affair?

“at the coronation feast, King Uther fell in love with Ygraine, wife of Gorlois, Duke of Cornwall. He lavished attention on her, to the scandal of the court; she made no response, but her husband, in fury, retired from the court without leave, taking his wife and men at arms back to Cornwall. Uther, in anger, commanded him to return, but Gorlois refused to obey. Then the King, enraged beyond measure, gathered an army and marched into Cornwall, burning the cities and castles. Gorlois had not enough troops to withstand him, so he placed his wife in the castle of Tintagel, the safest refuge, and himself prepared to defend the castle of Dimilioc. Uther immediately laid siege to Dimilioc, holding Gorlois and his troops trapped there, while he cast about for some way of breaking into the castle of Tintagel to ravish Ygraine”.This has ASOIAF written all over it. (Lyanna)

Lia wrote: "Noobs question for you Ian: how "orthodox" is Stewart's depiction of Uther and Lady Ygraine's affair?"

Lia wrote: "Noobs question for you Ian: how "orthodox" is Stewart's depiction of Uther and Lady Ygraine's affair?"Geoffrey of Monmouth keeps his focus almost entirely on the men. Gorlois has already appeared in his account as an heroic British leader and wise adviser, so his introduction is not as sudden as one might gather from summaries.

To use a nineteenth-century translation found on-line (which is just easier than copying Thorpe or Wright, who differ little here):

"Among the rest was present [at the coronation feast] Gorlois, duke of Cornwall, with his wife Igerna, the greatest beauty in all Britain. No sooner had the king cast his eyes upon her among the rest of the ladies, than he fell passionately in love with her, and little regarding the rest, made her the subject of all his thoughts. She was the only lady that he continually served with fresh dishes, and to whom he sent golden cups by his confidants; on her he bestowed all his smiles, and to her he addressed all his discourse. The husband, discovering this, fell into a great rage, and retired from the court without taking leave: nor was there any body that could stop him, while he was under fear of losing the chief object of his delight. Uther, therefore, in great wrath commanded him to return back to court, to make him satisfaction for this affront. But Gorlois refused to obey; upon which the king was highly incensed, and swore he would destroy his country, if he did not speedily compound for his offence. Accordingly, without delay, while their anger was hot against each other, the king got together a great army, and marched into Cornwall...."

The Robert de Boron "Merlin" traditions I've been reading lately more or less elaborately depict Ygraine's resistance to Uther's advances, and the various sleights he goes through to get her to accepts gifts (e.g., sending jewels to all the ladies attending court with their husbands, so she can't refuse; giving a golden cup to Gorlois, and asking that he present it to his wife; and so on). At no point does she seem interested in Uther's advances, and eventually, despite her fear of the king's predictable reaction to Gorlois' predictable reaction, tearfully informs her husband of his overtures, and those of his messengers.

Malory's account of the episode is fairly condensed, but his Ygraine is "a passing good woman," and promptly informs her husband of the King's advances. (I don't think it is clear whether Malory knew the older, more elaborate account and deliberately cut it.)

Mary Stewart faced a difficult problem with this part of the story. In her account, Merlin's "magic" is ESP, Roman engineering and medicine, local herb-lore, and the like. He can't really transform someone's appearance with a wave of his hand, not even his own. So Ygraine MUST be interested in Uther, and not be deceived by Merlin's "cunning spell."

I think she does the best she can with the unpleasant materials, in a largely rationalized context, but no one comes out of Stewart's version of the story well, except maybe poor old Gorlois, and even he is made to look a little foolish, what with his much younger wife.

I think she deserves points for just trying -- as I recall, Tennyson balked at the story, and just had Arthur a mysterious foundling.

Oh duh, I've read that in Malory. I just somehow didn't know this Ygraine and that Ygraine is the same Ygraine. I'm an idiot. (I didn't try to pronounce the names, so I just had this mental picture of a couple fleeing a persecuting lovesick king.)

Also, fair point -- no one comes out of Stewart's version very well, though I thought Merlin was completely whitewashed to the point of saintliness (if you accept the view that it's all god's will. I enjoyed Uther's tirade towards the end.)

Reading this side by side with Mabinogi, it also makes me aware how folktales (or children's fairy tales?) are not meant to be taken too literally, and we aren't meant to judge individual character's behavior. Yet, when modernized into a somewhat rational novel with magics explained away with technology and deception, everything suddenly becomes fair game for scrutiny.

Edit: I think I'm mostly surprised the Author saga started out with adultery. I thought that's specific to Lancelot and a sign of decline from what once was wholesome. I feel better knowing this isn't really canon.

Also, fair point -- no one comes out of Stewart's version very well, though I thought Merlin was completely whitewashed to the point of saintliness (if you accept the view that it's all god's will. I enjoyed Uther's tirade towards the end.)

Reading this side by side with Mabinogi, it also makes me aware how folktales (or children's fairy tales?) are not meant to be taken too literally, and we aren't meant to judge individual character's behavior. Yet, when modernized into a somewhat rational novel with magics explained away with technology and deception, everything suddenly becomes fair game for scrutiny.

Edit: I think I'm mostly surprised the Author saga started out with adultery. I thought that's specific to Lancelot and a sign of decline from what once was wholesome. I feel better knowing this isn't really canon.

Lia wrote: "I thought Merlin was completely whitewashed to the point of saintliness (if you accept the view that it's all god's will..."

Lia wrote: "I thought Merlin was completely whitewashed to the point of saintliness (if you accept the view that it's all god's will..."Of course, we are getting everything from Merlin's point of view, and in Stewart he doesn't seem prone to severe self-judgments.

In the Middle English "Prose Merlin" I've been re-reading (in fits and starts), there is a harsher view of the whole situation, as Merlin reflects on his responsibility, compared to that of Ulfin (Ulfius, etc.), Uther's flunky, who has just helped reach a peace agreement with Gorlois' vassals, and arranged Uther's marriage to the new widow, and those of Gorlois' daughters to various kings:

"And Merlin seide, "Vlfyn is som-what a-quytte of the synne that he hadde in the love makinge, but I am not yet a-quyt of that; I helped to disseyve the lady..." (a-quytte = acquited: disseyve = deceive).

This fits with the core works of the "Vulgate Cycle" for which the French original was written as an extended prologue. It does have a lot on sin and repentance, and not just in the "Quest of the Grail" portion. (The Vulgate has its own moral problems, though: in a sort of mirror image of the Uther/Arthur story, Lancelot begets Galahad after being magically tricked into thinking Elaine is Guinevere....)

In ways somewhat more elaborate than in Malory, Merlin arranges for the fostering of Arthur by Sir Antor (or Antron in other texts: Malory's Sir Ector), and things skip forward about fifteen years, until Uther becomes ill -- with gout -- and Merlin has to reassure him about his son (and now immediately prospective heir):

"the childe is feire and well growen, and well taught and norisshed."

The "well taught" is not paralleled in Malory, and doesn't seem to be behind White's decision to have the young Arthur tutored by Merlin himself -- whose whole origin and character is quite different, anyway.

(From time to time I run into people who think that "The Sword in the Stone" was substantially based on Malory, instead of just taking a few names and the over-all situation of Arthur's fostering.)

Mary Stewart devised her own version of the intervening years for "The Hollow Hills," but there is a distinct influence from T.H. White there -- although she may not have realized it. She was not happy when a review I published in a fanzine pointed out that in one detail, choosing a replacement for Lancelot from among the older layer of Arthur's followers, she seemed to have followed a precedent set by Rosemary Sutcliffe's "Sword at Sunset" (at least chronologically, if not by direct influence.)

Ian wrote: "she may not have realized it. She was not happy when a review I published in a fanzine pointed out that in one detail, choosing a replacement for Lancelot from among the older layer of Arthur's followers, she seemed to have followed a precedent set by Rosemary Sutcliffe..."

Picture/Link or it didn't happen!

I don't know how I missed all the names -- I think reading in two "different languages" made it harder for me to connect the two "worlds." Of course Ulfin is Ulfius, it never crossed my mind that they are the same character. And I keep trying to associate Ulfius with Orpheus, because I thought they sounded kind of similar (so far I found no parallel!)

It's like watching a basketball game with a gorilla dancing across the court and completely missing it. I don't believe this. Turns out I've encountered many minor characters in Stewarts' tale and I completely failed to recognize ANY.

Picture/Link or it didn't happen!

I don't know how I missed all the names -- I think reading in two "different languages" made it harder for me to connect the two "worlds." Of course Ulfin is Ulfius, it never crossed my mind that they are the same character. And I keep trying to associate Ulfius with Orpheus, because I thought they sounded kind of similar (so far I found no parallel!)

It's like watching a basketball game with a gorilla dancing across the court and completely missing it. I don't believe this. Turns out I've encountered many minor characters in Stewarts' tale and I completely failed to recognize ANY.

The special boy and the teacher in the cave really reminds me of Chiron training Achilles. Not that I would know what actually happened at Chiron's, with no more than 4 fragments.

What is with Cedal's sign against Merlin's "evil eye"?