The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Nicholas Nickleby

>

NN Chapters 26-30

Chapter 27

This chapter opens with Mrs Nickleby having visions of Kate being married to Sir Mulberry Hawk. She concludes her fantasy with the phrase “it sounds very well” or, as Dickens phrases it with his tongue, I am sure, firmly planted in his cheek- Mrs Nickleby had “triumphs of aerial architecture.” I do not want to belabour the point of who could afford a servant, (and so this will be the last time :-)) but we read that as Mrs Nickleby prepares a “frugal dinner” a “girl who attends her, partly for company, and partly to assist in the household affairs” enters the room to tell her that there are two gentlemen who are at the door who want to see her. Clearly, even those who eat “frugal meals” have servants. The two callers turn out to be Pyke and Pluck, and if anyone can speak with more annoying tone and phraseology than Mrs Nickleby it is these two men who announce they are friends of Sir Mulberry Hawk. At one point Pyke snatches from the chimney-piece a miniature of Kate done by Miss La Creevy. Now this part of the chapter struck me as highly amusing. We are told that Pyke and Pluck put on such a display of astonishment, enthusiasm, and even perhaps tears that “even the servant girl who had peeped in at the door, remained rooted to the spot in astonishment at the ecstasies of the two friendly visitors.” The curious and yet persuasive nature of these two men is evidenced when they claim to be thirsty and manage to convince Mrs Nickleby to pay for “a pot of mild half-and-half.” They, of course, drink it while Mrs Nickleby watches.

Thoughts

Who do you think sent Pyke and Pluck to visit Mrs Nickleby? For what purposes do you think they came? Given the conversation at Mrs Nickleby’s house, what information did they learn and what of that information could be most effectively be used in the future?

To what extent did you find the Pyke, Pluck, and Mrs Nickleby to be humourous?

Mrs Nickleby travels to the theatre where Pyke and Pluck are waiting. They escort her to a theatre box. Almost like magic, Sir Mulberry and Lord Verisopht appear dressed in all the finery of the foppish wealthy. Sir Mulberry tells Mrs Nickleby he wants to get to know her better. The more sophisticated and knowing Mrs Nickleby attempts to be in her conversation with Sir Mulberry, the bigger the fool she makes of herself. I imagine Sir Mulberry must have been almost choking with delight at her naïveté. Kate appears next and turns pale at the thought of her mother being in such company, not to mention her own dislike of Sir Mulberry. Mrs Nickleby, of course, thinks Kate is pale because of her “violent love” for Sir Mulberry. What a mess! What a great touch for Dickens to use the word “violent.” The oxymoron is perfect, and so very accurate in terms of Sir Mulberry. The social climber Mrs Wititterly appears next and has, perhaps, the best lines of this chapter. In her attempt to impress Hawk, Verisopht, Pyke, Pluck, Kate, and Mrs Nickleby she says “l’m always ill after Shakespeare .. I find the reaction so very great after a tragedy ... Shakespeare is such a delicious creature.” Mrs Nickleby follows with her own rambling reminiscence.

“I fear Shakespeare may never be the same for me.”

Thoughts

I enjoyed the addition of the Wititterly’s which was a fine touch by Dickens. This couple offers a good balance to Mrs Nickleby’s own pretensions of status and class. Which of these characters did you enjoy most in this chapter?

The chapter has both the tension of Kate obliged, once again, to reject the odious advances of Sir Mulberry and the humour of Mrs Nickleby and the Witittery’s as they pretend to have more social standing and class than they really do. Did you enjoy the mingling of humour and horror in this chapter?

The evening draws to a painful conclusion with Sir Mulberry passing his arm around Kate’s waist before she can reach the safety of a coach in which to cry. Sir Mulberry is very pleased with his own cleverness in tracking Kate down so quickly. Lord Verisopht bemoans his fate to be linked to Kate’s mother. Sir Mulberry then twists Lord Verisopht’s emotions around until he has Verisopht thinking Sir Mulberry is his best friend. Sir Mulberry, smelling blood in Verisopht’s weakness, suggests they go to the gaming table where Verisopht was “cleared out so handsomely last evening.” The chapter ends with Pyke and Pluck following the two gamblers, their patron Sir Mulberry and his victim Lord Verisopht.

Thoughts

Sir Mulberry is a despicable man, and yet he does seem to have some fear of Ralph Nickleby. From what we have read so far can you speculate what the reasons are for his respect for, if not fear of, Ralph Nickleby?

We are edging closer and closer to a time when Sir Mulberry must be dealt with by Dickens. For fun, what are your early guesses and suppositions as to how Dickens might deal with Sir Mulberry?

This chapter opens with Mrs Nickleby having visions of Kate being married to Sir Mulberry Hawk. She concludes her fantasy with the phrase “it sounds very well” or, as Dickens phrases it with his tongue, I am sure, firmly planted in his cheek- Mrs Nickleby had “triumphs of aerial architecture.” I do not want to belabour the point of who could afford a servant, (and so this will be the last time :-)) but we read that as Mrs Nickleby prepares a “frugal dinner” a “girl who attends her, partly for company, and partly to assist in the household affairs” enters the room to tell her that there are two gentlemen who are at the door who want to see her. Clearly, even those who eat “frugal meals” have servants. The two callers turn out to be Pyke and Pluck, and if anyone can speak with more annoying tone and phraseology than Mrs Nickleby it is these two men who announce they are friends of Sir Mulberry Hawk. At one point Pyke snatches from the chimney-piece a miniature of Kate done by Miss La Creevy. Now this part of the chapter struck me as highly amusing. We are told that Pyke and Pluck put on such a display of astonishment, enthusiasm, and even perhaps tears that “even the servant girl who had peeped in at the door, remained rooted to the spot in astonishment at the ecstasies of the two friendly visitors.” The curious and yet persuasive nature of these two men is evidenced when they claim to be thirsty and manage to convince Mrs Nickleby to pay for “a pot of mild half-and-half.” They, of course, drink it while Mrs Nickleby watches.

Thoughts

Who do you think sent Pyke and Pluck to visit Mrs Nickleby? For what purposes do you think they came? Given the conversation at Mrs Nickleby’s house, what information did they learn and what of that information could be most effectively be used in the future?

To what extent did you find the Pyke, Pluck, and Mrs Nickleby to be humourous?

Mrs Nickleby travels to the theatre where Pyke and Pluck are waiting. They escort her to a theatre box. Almost like magic, Sir Mulberry and Lord Verisopht appear dressed in all the finery of the foppish wealthy. Sir Mulberry tells Mrs Nickleby he wants to get to know her better. The more sophisticated and knowing Mrs Nickleby attempts to be in her conversation with Sir Mulberry, the bigger the fool she makes of herself. I imagine Sir Mulberry must have been almost choking with delight at her naïveté. Kate appears next and turns pale at the thought of her mother being in such company, not to mention her own dislike of Sir Mulberry. Mrs Nickleby, of course, thinks Kate is pale because of her “violent love” for Sir Mulberry. What a mess! What a great touch for Dickens to use the word “violent.” The oxymoron is perfect, and so very accurate in terms of Sir Mulberry. The social climber Mrs Wititterly appears next and has, perhaps, the best lines of this chapter. In her attempt to impress Hawk, Verisopht, Pyke, Pluck, Kate, and Mrs Nickleby she says “l’m always ill after Shakespeare .. I find the reaction so very great after a tragedy ... Shakespeare is such a delicious creature.” Mrs Nickleby follows with her own rambling reminiscence.

“I fear Shakespeare may never be the same for me.”

Thoughts

I enjoyed the addition of the Wititterly’s which was a fine touch by Dickens. This couple offers a good balance to Mrs Nickleby’s own pretensions of status and class. Which of these characters did you enjoy most in this chapter?

The chapter has both the tension of Kate obliged, once again, to reject the odious advances of Sir Mulberry and the humour of Mrs Nickleby and the Witittery’s as they pretend to have more social standing and class than they really do. Did you enjoy the mingling of humour and horror in this chapter?

The evening draws to a painful conclusion with Sir Mulberry passing his arm around Kate’s waist before she can reach the safety of a coach in which to cry. Sir Mulberry is very pleased with his own cleverness in tracking Kate down so quickly. Lord Verisopht bemoans his fate to be linked to Kate’s mother. Sir Mulberry then twists Lord Verisopht’s emotions around until he has Verisopht thinking Sir Mulberry is his best friend. Sir Mulberry, smelling blood in Verisopht’s weakness, suggests they go to the gaming table where Verisopht was “cleared out so handsomely last evening.” The chapter ends with Pyke and Pluck following the two gamblers, their patron Sir Mulberry and his victim Lord Verisopht.

Thoughts

Sir Mulberry is a despicable man, and yet he does seem to have some fear of Ralph Nickleby. From what we have read so far can you speculate what the reasons are for his respect for, if not fear of, Ralph Nickleby?

We are edging closer and closer to a time when Sir Mulberry must be dealt with by Dickens. For fun, what are your early guesses and suppositions as to how Dickens might deal with Sir Mulberry?

NN Chapter 28

We begin this chapter the morning after the theatrical evening of Kate, her mother, the Wititterly’s, and Sir Mulberry’s dissipated quartette. Kate’s problems continue, and, if possible grow even worse. The Wititterly’s have invited Sir Mulberry and Lord Verisopht to visit. Such an invitation works for both parties. The Wititterly’s see this as an opportunity to move further up the social and class ladder by associating with those with titles. For Hawk and his gull Verisopht, it is an opportunity to continue to worm themselves further into the world of Kate. For Kate, however, such invitations just create another chapter of horror into her life.

Kate is reading a rather insipid novel to Mrs Wititterly when Sir Mulberry and his hangers-on arrive which gives Mrs Wititterly the opportunity to throw herself into the most striking “little pantomime of graceful attitudes ... to astonish the visitors.” As before, Pyke and Pluck are effervescent in their attentions to the group and Lord Verisopht ends up amusing himself while Sir Mulberry continues his rabid pursuit of Kate. At the end of this visit the Wititterly’s invite their distinguished visitors back and, of course, they do return, time and time again for a fortnight. During these visits Sir Mulberry “attached himself to Kate with less and less disguise [and] Mrs Wititterly began to grow jealous of the superior attractions of Miss Nickleby.” Kate is now completely trapped. On the one hand Sir Mulberry has received unrestricted freedom to pursue Kate and the person who is unwittingly allowing such a pursuit is becoming jealous of the attention that Kate is getting. Mrs Wititterly develops a “virtuous indignation” against Kate and tells Kate to stop her pursuit of Sir Mulberry. To her credit, Kate defends herself against these false accusations which leads to Mrs Wititterly screaming and her husband declaring “that society has been too much for her.”

Thoughts

Sir Mulberry is relentless in his pursuit of Kate. To what extent do you think Dickens has accurately portrayed the Kate-Sir Mulberry situation and reflected the reality of the class structure and attitudes of the individuals within each of the classes?

Both Mrs Nickleby and the Wititterly’s strive to improve their social standing. Who do you find the most interesting to follow?

Dickens makes both Mrs Nickleby and The Wititterly’s objects of both humour and derision. Why do you think Dickens created both sets of characters to establish basically the same idea in the novel?

Kate has had enough. She decides to visit her uncle and see what influence he may have over the unwanted advances of Sir Mulberry and his band of disreputable hangers on. Before he sees his niece, Ralph puts away his cash-box and replaces it with an empty purse. As Ralph sees his niece and witnesses her tears, he is basically unsympathetic. Kate firmly and assertively tells her uncle that he is cruel and knowingly has allowed her life to be miserable. She tells Ralph that she is “wretched, and that [her] heart is breaking.” Not only does she find the men’s attentions odious, but her mother is deluded into thinking the men are honourable. Kate does not want to ruin “these little delusions, which are the only happiness she has.”

Her uncle is unmoved by Kate’s pleading. He says that “we are connected by business ... in business, and I cannot afford to offend them ... some girls would be proud to have such gallants at their feet.” Well, so much for his understanding! Kate then outlines how she will become “the scorn of my own sex, and the toy of the other” without some resolution to her situation.

Thoughts

Kate is a fascinating character. With her creation, Dickens is able to raise several social and cultural questions to his readership. Let’s have a look at some of them.

Women and girls of limited financial means had very few options in their lives. We have seen passing comments referring to serving girls and girls-of-all-work. Miss La Creevy, with a skill, is able to sustain herself. There are, however, untold females who were faced with difficult choices in their lives. They could do manual labour, hope that they had some special skill like those who work at Madame Mantalini’s, or become companions or governesses. After that, however, a short life of a mistress, a life on the streets as a prostitute, or an early grave were, in all likelihood, very common options. To this point in the novel what other options for life has Dickens presented to his readers?

From your other reading of Dickens and other Victorian novelists how common is Kate’s plight?

Both Kate and Nicholas have strong morals and a keen sense of the difference between right and wrong. Both characters also have quick tempers when they perceive an injustice has occurred. To what extent do you think Dickens is supportive of people like Nicholas and Kate so clearly expressing themselves?

The next scene in the chapter is one where Kate and Newman Noggs are together. Newman offers comfort and care. We see that Newman also sheds a tear with and for Kate. He also tells Kate that he will soon see her again and offers the prophecy that she shall see someone else soon as well. In the office we read that although Ralph Nickleby’s libertine clients have done exactly what he expected, and indeed wanted, they still disgust him. He then comments to himself “Oh! you shall pay for this.” When I see the “pay” I don’t think he means, in this instance, pay with money. Could this be a threat? Is it a prediction? What do you think he means?

As the chapter we see Newman Noggs “bestowing the most vigorous, scientific, and straightforward blows upon the empty air.” His opponent in his imagination - Mr Ralph Nickleby.

Thoughts

We have moved far from the horrors of the rural Dotheboys Hall and are now in the urban world of finance. Now, our disreputable characters are titled men and money lenders, not schoolmasters, but the end game remains the same. Each person of power is intent on doing whatever means it takes to make money. The needs and fate others are of no concern. Money, money, money, and cruelty are the two drivers of those in power. How do you think Dickens could tilt the balance of events to this point in the novel?

How realistic have you found the novel to date?

We begin this chapter the morning after the theatrical evening of Kate, her mother, the Wititterly’s, and Sir Mulberry’s dissipated quartette. Kate’s problems continue, and, if possible grow even worse. The Wititterly’s have invited Sir Mulberry and Lord Verisopht to visit. Such an invitation works for both parties. The Wititterly’s see this as an opportunity to move further up the social and class ladder by associating with those with titles. For Hawk and his gull Verisopht, it is an opportunity to continue to worm themselves further into the world of Kate. For Kate, however, such invitations just create another chapter of horror into her life.

Kate is reading a rather insipid novel to Mrs Wititterly when Sir Mulberry and his hangers-on arrive which gives Mrs Wititterly the opportunity to throw herself into the most striking “little pantomime of graceful attitudes ... to astonish the visitors.” As before, Pyke and Pluck are effervescent in their attentions to the group and Lord Verisopht ends up amusing himself while Sir Mulberry continues his rabid pursuit of Kate. At the end of this visit the Wititterly’s invite their distinguished visitors back and, of course, they do return, time and time again for a fortnight. During these visits Sir Mulberry “attached himself to Kate with less and less disguise [and] Mrs Wititterly began to grow jealous of the superior attractions of Miss Nickleby.” Kate is now completely trapped. On the one hand Sir Mulberry has received unrestricted freedom to pursue Kate and the person who is unwittingly allowing such a pursuit is becoming jealous of the attention that Kate is getting. Mrs Wititterly develops a “virtuous indignation” against Kate and tells Kate to stop her pursuit of Sir Mulberry. To her credit, Kate defends herself against these false accusations which leads to Mrs Wititterly screaming and her husband declaring “that society has been too much for her.”

Thoughts

Sir Mulberry is relentless in his pursuit of Kate. To what extent do you think Dickens has accurately portrayed the Kate-Sir Mulberry situation and reflected the reality of the class structure and attitudes of the individuals within each of the classes?

Both Mrs Nickleby and the Wititterly’s strive to improve their social standing. Who do you find the most interesting to follow?

Dickens makes both Mrs Nickleby and The Wititterly’s objects of both humour and derision. Why do you think Dickens created both sets of characters to establish basically the same idea in the novel?

Kate has had enough. She decides to visit her uncle and see what influence he may have over the unwanted advances of Sir Mulberry and his band of disreputable hangers on. Before he sees his niece, Ralph puts away his cash-box and replaces it with an empty purse. As Ralph sees his niece and witnesses her tears, he is basically unsympathetic. Kate firmly and assertively tells her uncle that he is cruel and knowingly has allowed her life to be miserable. She tells Ralph that she is “wretched, and that [her] heart is breaking.” Not only does she find the men’s attentions odious, but her mother is deluded into thinking the men are honourable. Kate does not want to ruin “these little delusions, which are the only happiness she has.”

Her uncle is unmoved by Kate’s pleading. He says that “we are connected by business ... in business, and I cannot afford to offend them ... some girls would be proud to have such gallants at their feet.” Well, so much for his understanding! Kate then outlines how she will become “the scorn of my own sex, and the toy of the other” without some resolution to her situation.

Thoughts

Kate is a fascinating character. With her creation, Dickens is able to raise several social and cultural questions to his readership. Let’s have a look at some of them.

Women and girls of limited financial means had very few options in their lives. We have seen passing comments referring to serving girls and girls-of-all-work. Miss La Creevy, with a skill, is able to sustain herself. There are, however, untold females who were faced with difficult choices in their lives. They could do manual labour, hope that they had some special skill like those who work at Madame Mantalini’s, or become companions or governesses. After that, however, a short life of a mistress, a life on the streets as a prostitute, or an early grave were, in all likelihood, very common options. To this point in the novel what other options for life has Dickens presented to his readers?

From your other reading of Dickens and other Victorian novelists how common is Kate’s plight?

Both Kate and Nicholas have strong morals and a keen sense of the difference between right and wrong. Both characters also have quick tempers when they perceive an injustice has occurred. To what extent do you think Dickens is supportive of people like Nicholas and Kate so clearly expressing themselves?

The next scene in the chapter is one where Kate and Newman Noggs are together. Newman offers comfort and care. We see that Newman also sheds a tear with and for Kate. He also tells Kate that he will soon see her again and offers the prophecy that she shall see someone else soon as well. In the office we read that although Ralph Nickleby’s libertine clients have done exactly what he expected, and indeed wanted, they still disgust him. He then comments to himself “Oh! you shall pay for this.” When I see the “pay” I don’t think he means, in this instance, pay with money. Could this be a threat? Is it a prediction? What do you think he means?

As the chapter we see Newman Noggs “bestowing the most vigorous, scientific, and straightforward blows upon the empty air.” His opponent in his imagination - Mr Ralph Nickleby.

Thoughts

We have moved far from the horrors of the rural Dotheboys Hall and are now in the urban world of finance. Now, our disreputable characters are titled men and money lenders, not schoolmasters, but the end game remains the same. Each person of power is intent on doing whatever means it takes to make money. The needs and fate others are of no concern. Money, money, money, and cruelty are the two drivers of those in power. How do you think Dickens could tilt the balance of events to this point in the novel?

How realistic have you found the novel to date?

NN 29

In this chapter we leave the congested streets of London and travel down to Portsmouth where we find the Crummles theatre troupe have enjoyed much success. Nicholas has distinguished himself and the benefit raised “no less than the sum of twenty pounds.” When we consider that the pay for Nicholas for one year at Dotheboys Hall was to be five pounds, Nicholas must think that he has struck it rich. Possessed with this money, Nicholas sends John Browdie the amount he owes him with wishes for his “matrimonial happiness” and then to Newman Noggs he sends half the rest, to be given to Kate in secret along with his love and affection. He also asks Newman for an update on his mother and sister.

The opening sentences of this chapter are very important as they fulfill many functions in terms of the plot and the setting. First, Dickens keeps open the connection with John Browdie. As readers, we see how Nicholas is maturing. He wants to pay his debts and his wish for success of the Bowdrie’s in genuine. Nicholas’s links with the north are therefore continued and strengthened. With John Browdie still in the reader’s mind, he may well make another appearance later in the novel. Second, the money sent to his sister, and thus, by implication, to his mother, develops Nicholas’s family connections and thus we see Nicholas maintaining his role as the dutiful son. For everything that Ralph Nickleby is not in connection to the family, Nicholas is to the family. The third affirmation comes in the conversation Nicholas has with Smike. Smike learns that Nicholas has a sister, that he will meet her one day, and that Nicholas and Smike will continue their close relationship. Smike also learns that Nicholas has an enemy. For his part, Smike says, in a masterful stroke of understatement, that he certainly does understand what an enemy is - “Oh, yes, I understand that.” Squeers always hovers in the background, or would that be the foreground, of his thoughts.

Thoughts

To me, this chapter is one of transitions and reinforcement. Besides what I have noted, what other important elements of plot, character, and setting does Dickens establish in this chapter?

Nicholas does not seem to be able to get a break. Just when it seems that all will be well for Nicholas in this chapter Mr Folair appears with the unsettling news that another actor has felt his nose out of joint with Nicholas’s success and reception. It was Lenville’s initial intent to wound Nicholas in a sword fight, and thus get Nicholas off the stage for a month or so and, at the same time, ride on the notoriety of being the man who “pinked” another actor. “Notoriety, notoriety, is the thing ... ah, it would have been worth eight to ten shillings a week to him.” Fast forward to the next morning where after some delightfully described antics between Nicholas and Lenville, Nicholas knocks Lenville to the ground. After Mrs Lenville’s insistence, her husband apologizes to Nicholas. Nicholas, for his part, gives Lenville a short lecture on the dangers of excessive jealousy and not understanding an adversary’s anger. Nicholas, in his own theatrical flourish, breaks Lenville’s ash stick in two, bows to the spectators, and walks away.

Thoughts

What are we to think of Nicholas’s actions? To what extent do you think he was justified in not only not apologizing to Lenville - albeit for nominal slight - but in knocking Lenville down, lecturing Lenville, and then breaking his stick? Was this an over-reaction on Nicholas’s part?

In this scene we see that Nicholas has a temper, and that it can flair up quickly. Why do you think Dickens keeps demonstrating that Nicholas has a temper?

This scene, for all its physicality, is broadly humourous. Was this a favourite comic scene to you? If not, what scene has given you the most pleasure so far in the novel? Why?

Later, Nicholas receives a letter from Newman Noggs and manages to decipher it in 30 minutes. The contents are unsettling. Newman hints that a time may come soon when Kate would need the protection and presence of Nicholas. If and when such a situation would arise, Newman says he will write immediately. Nicholas suspects that such unease on Newman’s part may well be because of something connected to Ralph Nickleby. Nicholas hurries off to see Mr Crummles and tells him that he will be shortly leaving the acting company. Some actors are upset, but others are relieved. With Nicholas gone, there will be more space for their own careers.

The chapter ends with Nicholas thinking about his sister and the trouble and distress she might be encountering.

Thoughts

Are you surprised that Nicholas's acting career is coming to a halt so soon in the novel?

So far, Nicholas has had three short-lived careers, one at Dotheboys, one as a private tutor, and one with Crummles acting troupe. Which of these three did you find most effectively presented to the reader? Why?

How has Dickens grown the character of Nicholas Nickleby during his time with Crummles?

In this chapter we leave the congested streets of London and travel down to Portsmouth where we find the Crummles theatre troupe have enjoyed much success. Nicholas has distinguished himself and the benefit raised “no less than the sum of twenty pounds.” When we consider that the pay for Nicholas for one year at Dotheboys Hall was to be five pounds, Nicholas must think that he has struck it rich. Possessed with this money, Nicholas sends John Browdie the amount he owes him with wishes for his “matrimonial happiness” and then to Newman Noggs he sends half the rest, to be given to Kate in secret along with his love and affection. He also asks Newman for an update on his mother and sister.

The opening sentences of this chapter are very important as they fulfill many functions in terms of the plot and the setting. First, Dickens keeps open the connection with John Browdie. As readers, we see how Nicholas is maturing. He wants to pay his debts and his wish for success of the Bowdrie’s in genuine. Nicholas’s links with the north are therefore continued and strengthened. With John Browdie still in the reader’s mind, he may well make another appearance later in the novel. Second, the money sent to his sister, and thus, by implication, to his mother, develops Nicholas’s family connections and thus we see Nicholas maintaining his role as the dutiful son. For everything that Ralph Nickleby is not in connection to the family, Nicholas is to the family. The third affirmation comes in the conversation Nicholas has with Smike. Smike learns that Nicholas has a sister, that he will meet her one day, and that Nicholas and Smike will continue their close relationship. Smike also learns that Nicholas has an enemy. For his part, Smike says, in a masterful stroke of understatement, that he certainly does understand what an enemy is - “Oh, yes, I understand that.” Squeers always hovers in the background, or would that be the foreground, of his thoughts.

Thoughts

To me, this chapter is one of transitions and reinforcement. Besides what I have noted, what other important elements of plot, character, and setting does Dickens establish in this chapter?

Nicholas does not seem to be able to get a break. Just when it seems that all will be well for Nicholas in this chapter Mr Folair appears with the unsettling news that another actor has felt his nose out of joint with Nicholas’s success and reception. It was Lenville’s initial intent to wound Nicholas in a sword fight, and thus get Nicholas off the stage for a month or so and, at the same time, ride on the notoriety of being the man who “pinked” another actor. “Notoriety, notoriety, is the thing ... ah, it would have been worth eight to ten shillings a week to him.” Fast forward to the next morning where after some delightfully described antics between Nicholas and Lenville, Nicholas knocks Lenville to the ground. After Mrs Lenville’s insistence, her husband apologizes to Nicholas. Nicholas, for his part, gives Lenville a short lecture on the dangers of excessive jealousy and not understanding an adversary’s anger. Nicholas, in his own theatrical flourish, breaks Lenville’s ash stick in two, bows to the spectators, and walks away.

Thoughts

What are we to think of Nicholas’s actions? To what extent do you think he was justified in not only not apologizing to Lenville - albeit for nominal slight - but in knocking Lenville down, lecturing Lenville, and then breaking his stick? Was this an over-reaction on Nicholas’s part?

In this scene we see that Nicholas has a temper, and that it can flair up quickly. Why do you think Dickens keeps demonstrating that Nicholas has a temper?

This scene, for all its physicality, is broadly humourous. Was this a favourite comic scene to you? If not, what scene has given you the most pleasure so far in the novel? Why?

Later, Nicholas receives a letter from Newman Noggs and manages to decipher it in 30 minutes. The contents are unsettling. Newman hints that a time may come soon when Kate would need the protection and presence of Nicholas. If and when such a situation would arise, Newman says he will write immediately. Nicholas suspects that such unease on Newman’s part may well be because of something connected to Ralph Nickleby. Nicholas hurries off to see Mr Crummles and tells him that he will be shortly leaving the acting company. Some actors are upset, but others are relieved. With Nicholas gone, there will be more space for their own careers.

The chapter ends with Nicholas thinking about his sister and the trouble and distress she might be encountering.

Thoughts

Are you surprised that Nicholas's acting career is coming to a halt so soon in the novel?

So far, Nicholas has had three short-lived careers, one at Dotheboys, one as a private tutor, and one with Crummles acting troupe. Which of these three did you find most effectively presented to the reader? Why?

How has Dickens grown the character of Nicholas Nickleby during his time with Crummles?

NN Ch 30

Upon learning that Nicholas and Smike plan to leave the theatre company and return to London Mr Crummles is suitably distraught. On the other hand, Mr Crummles also sees the leaving of Nicholas as a way to make some money for the troupe. Nicholas will make three final appearances although Nicholas does draw the line at singing a song on a pony’s back. What follows is a delightful and lighthearted look at the theatre troupe and its various characters. There is much talk about Smike which helps to continue the importance of Smike to Nicholas and the novel. What is made clear in the conversation is Smike’s lack of intelligence and background. The close relationship between Smike and Nicholas is again reinforced. We learn that there remains many questions about the relationship between Nicholas and Smike.

We then get delightful interactions between Nicholas, Miss Snecellicci and Miss Ledrook which adds to the light-hearted nature of the chapter3. Nicholas and Smike next find themselves at a party at the tailor’s house where Dickens takes delight in describing both the place and the characters. There are many lines and descriptions that could be used as examples but I offer one as being so delightful and so absurd that I cannot let it pass. Mr Lillyvick is singing the praises of the late Miss Petowker and states “Look at her now she moves to put the kettle on. There! Isn’t it fascination, Sir?” Nicholas’s response is a masterful stroke of understatement - “You’re a lucky man.” I have never thought about how anyone moves to put a kettle on before I read these lines. I may never watch anyone put a kettle on in the future the same way again. To me, Dickens at his best. The party ends with Nicholas successfully navigating the shoals of unattached females and he takes his leave and “the ladies were unanimous in pronouncing him quite the monster of insensibility.

Thoughts

Kettles aside ... where there any lines in this chapter that you found particularly quirky, unique, or entertaining? Please share them with us.

Dickens loved the theatre and I think that love comes through clearly in this chapter. Would this chapter have been more revealing if Dickens had dwelt on the grand and tragic struggles of rural theatre companies rather than its humourous aspects.

I can’t help but ask a trivia question. Do you recall - without peeking - what Nicholas Nickleby and Smike’s stage pseudonyms were?

And, of course, what is a party without someone getting a bit tipsy? We are told that Mr Snevellicci “was a little addicted to drinking; or, if the whole truth must be told, that he was scarcely ever sober.” Should we invite him to meet with The Curiosities at the Saracen’s Head?

The next day all the theatre posters announced Nicholas’s final appearance(s). There is a London manager in the audience and so the theatre excitement doubles. Everyone in Crummles company believes he is there to see them. It turns out that the London manager is asleep in the audience. He then left the theatre. So many great expectations shattered.

Nicholas receives a letter from Newman Noggs which was “very inky, very short, very dirty, very small, and very mysterious, urging Nicholas to return to London instantly; not to lose an instant; to be there that night if possible.” Nicholas dashes off to say goodbye to Mr Crummles and dashes off to the coach office. There he meets with Crummles again and receives from Crummles an Oscar-worthy embrace (technically a Toni for acting in the theatre) and then off he and Smike go, heading for London, and whatever fate they will encounter.

Thoughts

As you know I love finding patterns and echoes in novels and so the ending of this chapter resonated very strongly with me. I’m not sure if it means anything or not so I need your help. I do realize that to travel a distance one would take a coach but still ... . When Nicholas set off for Dotheboys Hall he did so by coach in a scene rich in character, action, and accompanied by a great illustration by Phiz. We recall, at that time, Nicholas was given a letter by Newman Noggs. In this chapter we have Nicholas once again setting off on another coach journey. This time rather than leaving London in order to help support his family he is coming back to London. Again, a letter from Newman Noggs frames the action of Nicholas, and again we have a delightful illustration by Phiz. Do you think there is any pattern, logic or link in these two scenes? What might be the meaning?

Upon learning that Nicholas and Smike plan to leave the theatre company and return to London Mr Crummles is suitably distraught. On the other hand, Mr Crummles also sees the leaving of Nicholas as a way to make some money for the troupe. Nicholas will make three final appearances although Nicholas does draw the line at singing a song on a pony’s back. What follows is a delightful and lighthearted look at the theatre troupe and its various characters. There is much talk about Smike which helps to continue the importance of Smike to Nicholas and the novel. What is made clear in the conversation is Smike’s lack of intelligence and background. The close relationship between Smike and Nicholas is again reinforced. We learn that there remains many questions about the relationship between Nicholas and Smike.

We then get delightful interactions between Nicholas, Miss Snecellicci and Miss Ledrook which adds to the light-hearted nature of the chapter3. Nicholas and Smike next find themselves at a party at the tailor’s house where Dickens takes delight in describing both the place and the characters. There are many lines and descriptions that could be used as examples but I offer one as being so delightful and so absurd that I cannot let it pass. Mr Lillyvick is singing the praises of the late Miss Petowker and states “Look at her now she moves to put the kettle on. There! Isn’t it fascination, Sir?” Nicholas’s response is a masterful stroke of understatement - “You’re a lucky man.” I have never thought about how anyone moves to put a kettle on before I read these lines. I may never watch anyone put a kettle on in the future the same way again. To me, Dickens at his best. The party ends with Nicholas successfully navigating the shoals of unattached females and he takes his leave and “the ladies were unanimous in pronouncing him quite the monster of insensibility.

Thoughts

Kettles aside ... where there any lines in this chapter that you found particularly quirky, unique, or entertaining? Please share them with us.

Dickens loved the theatre and I think that love comes through clearly in this chapter. Would this chapter have been more revealing if Dickens had dwelt on the grand and tragic struggles of rural theatre companies rather than its humourous aspects.

I can’t help but ask a trivia question. Do you recall - without peeking - what Nicholas Nickleby and Smike’s stage pseudonyms were?

And, of course, what is a party without someone getting a bit tipsy? We are told that Mr Snevellicci “was a little addicted to drinking; or, if the whole truth must be told, that he was scarcely ever sober.” Should we invite him to meet with The Curiosities at the Saracen’s Head?

The next day all the theatre posters announced Nicholas’s final appearance(s). There is a London manager in the audience and so the theatre excitement doubles. Everyone in Crummles company believes he is there to see them. It turns out that the London manager is asleep in the audience. He then left the theatre. So many great expectations shattered.

Nicholas receives a letter from Newman Noggs which was “very inky, very short, very dirty, very small, and very mysterious, urging Nicholas to return to London instantly; not to lose an instant; to be there that night if possible.” Nicholas dashes off to say goodbye to Mr Crummles and dashes off to the coach office. There he meets with Crummles again and receives from Crummles an Oscar-worthy embrace (technically a Toni for acting in the theatre) and then off he and Smike go, heading for London, and whatever fate they will encounter.

Thoughts

As you know I love finding patterns and echoes in novels and so the ending of this chapter resonated very strongly with me. I’m not sure if it means anything or not so I need your help. I do realize that to travel a distance one would take a coach but still ... . When Nicholas set off for Dotheboys Hall he did so by coach in a scene rich in character, action, and accompanied by a great illustration by Phiz. We recall, at that time, Nicholas was given a letter by Newman Noggs. In this chapter we have Nicholas once again setting off on another coach journey. This time rather than leaving London in order to help support his family he is coming back to London. Again, a letter from Newman Noggs frames the action of Nicholas, and again we have a delightful illustration by Phiz. Do you think there is any pattern, logic or link in these two scenes? What might be the meaning?

(PET PEEVE ALERT!)

(PET PEEVE ALERT!) It took us until chapter 28 to get there, but I could have bet my childrens' lives that it was coming:

"'I have gone on day after day,' said Kate, bending over him, and timidly placing her little hand in his..."

I'm starting to see tiny hands and feet as often as Peter sees birds. Only where he delights in his finds, I cringe at mine. I'm tempted to write the Dickens Museum and see if they have any of Mary's shoes, so we'll know just how tiny she was.

Peter wrote: "Who do you find to be the worst? Of these three, do you think Dickens will rehabilitate any of them by the end of the novel? Why? ..."

Peter wrote: "Who do you find to be the worst? Of these three, do you think Dickens will rehabilitate any of them by the end of the novel? Why? ..."Ralph and Hawk are reprehensible, but I think the worst is Squeers. Squeers and Hawk don't seem to see anything wrong with their behaviour, so I don't hold out hope that they'll change. Ralph, though, has shown hairline cracks in his veneer, and I think he'll be somewhat reformed by the end of the novel. Or, at least, realize he's been a cad, even if he doesn't make amends. Some quotes that lead me to this conclusion:

'Well,' said Ralph, roughly enough; but still with something more of kindness in his manner than he would have exhibited towards anybody else.

"Well!' thought Ralph--for the moment quite disconcerted, as he watched the anguish of his beautiful niece.

Ralph looked at her for an instant; then turned away his head, and beat his foot nervously upon the ground.

...although his libertine clients had done precisely what he had expected... still he hated them for doing it, from the very

bottom of his soul.

All of these are indications that deep - DEEP - down, Ralph has a conscience. Guilt is seeping through the cracks. I don't think he recognizes it - it's not a feeling he's had for a long, long time. But a few more encounters with Kate, and maybe he'll soften up, at least enough that he won't die a cold, lonely death like Dombey. But I can't see a full turn-around like Scrooge, either. It will be enough for me if he just feels some remorse and asks forgiveness.

PS Peter wrote: Both Kate and Nicholas have strong morals and a keen sense of the difference between right and wrong. Both characters also have quick tempers when they perceive an injustice has occurred.

As Mrs. Nickleby is such a twit, we can only assume that Nick and Kate inherited their noble characteristics from their father, which would indicate that Nick, Sr. and Ralph were probably raised in a moral, upright way, but Ralph got lost along the way. Which also bodes well for him getting back on the right path as the novel progresses.

Pyke and Pluck are something else, aren't they? And the perfect pair to befuddle Mrs. Nickleby. When she finally showed some common sense at the theater and asked where Ralph was, they succeeded in talking circles around it, without ever answering her question. What's in it for them, I wonder....

Pyke and Pluck are something else, aren't they? And the perfect pair to befuddle Mrs. Nickleby. When she finally showed some common sense at the theater and asked where Ralph was, they succeeded in talking circles around it, without ever answering her question. What's in it for them, I wonder....

Peter wrote: "This novel is supposedly one that contains much humour, but I confess to finding little to laugh about in the novel so far or in this chapter either. No doubt Mrs Nickleby is supposedly funny in her own way, but I find her speeches far too lengthy and, candidly, annoying. What am I missing in my response to Mrs Nickleby’s character? ..."

Peter wrote: "This novel is supposedly one that contains much humour, but I confess to finding little to laugh about in the novel so far or in this chapter either. No doubt Mrs Nickleby is supposedly funny in her own way, but I find her speeches far too lengthy and, candidly, annoying. What am I missing in my response to Mrs Nickleby’s character? ..."I don't think you're missing a thing where Mrs. Nickleby is concerned. The humor in this book is not from her (at least I hope it wasn't meant to be that way), but from the knowing, cynical narrator, pointing out human quirks and foibles.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Who do you find to be the worst? Of these three, do you think Dickens will rehabilitate any of them by the end of the novel? Why? ..."

Ralph and Hawk are reprehensible, but I think t..."

Mary Lou

You point out some very interesting cracks in Ralph Nickleby’s veneer of being cold and avaricious. It will be interesting to see how far Dickens will move our initial impressions of him. No doubt, surprises still await us.

Ralph and Hawk are reprehensible, but I think t..."

Mary Lou

You point out some very interesting cracks in Ralph Nickleby’s veneer of being cold and avaricious. It will be interesting to see how far Dickens will move our initial impressions of him. No doubt, surprises still await us.

Peter wrote: "This novel is supposedly one that contains much humour, but I confess to finding little to laugh about in the novel so far or in this chapter either. No doubt Mrs Nickleby is supposedly funny in her own way, but I find her speeches far too lengthy and, candidly, annoying. What am I missing in my response to Mrs Nickleby’s character?"

Peter wrote: "This novel is supposedly one that contains much humour, but I confess to finding little to laugh about in the novel so far or in this chapter either. No doubt Mrs Nickleby is supposedly funny in her own way, but I find her speeches far too lengthy and, candidly, annoying. What am I missing in my response to Mrs Nickleby’s character?"For me, this novel alternates between humorous and disturbing, but overall, funnier than OT. I don't think you're missing much about Mrs. Nickleby. She truly is annoying and unlikable.

I thought the depths of her ignorance turned scary in chapter 26, when she basically gave her daughter to a predator, without asking her daughter's feelings or doing her due diligence. She reminded me of the Dotheboys parents, in this respect.

The only time Mrs. Nickleby made me laugh was chap. 27, when she talked about an elaborate cold remedy with a bucket of bran and boiling water, "Then, you put your head in it for twenty minutes...I mean, feet!" Otherwise, it was the narrator and the silly charades of Hawk, Pyke, and Pluck that made me laugh.

What I find interesting about Mrs. Nickleby now, is that Dickens is bringing out her evil side. Her fantasies spring from vanity, greed, and arrogance, not true concern for Kate's welfare. I don't think she intentionally wants to hurt anyone, but at the same time, she is self-absorbed and lacking in moral fiber.

What I find interesting about Mrs. Nickleby now, is that Dickens is bringing out her evil side. Her fantasies spring from vanity, greed, and arrogance, not true concern for Kate's welfare. I don't think she intentionally wants to hurt anyone, but at the same time, she is self-absorbed and lacking in moral fiber.Ralph's comment at the end, "selling a girl" as "match-making mothers do the same thing every day,” was thought-provoking, since it puts Mrs. Nickleby at the same level of evil as him.

Alissa wrote: "What I find interesting about Mrs. Nickleby now, is that Dickens is bringing out her evil side. Her fantasies spring from vanity, greed, and arrogance, not true concern for Kate's welfare. I don't ..."

Alissa

You raise a very interesting point about Mrs Nickleby and Ralph Nickleby being on the same level of evil in some ways. I never thought of that angle. It is true. Marrying off a female child was not unusual.

Alissa

You raise a very interesting point about Mrs Nickleby and Ralph Nickleby being on the same level of evil in some ways. I never thought of that angle. It is true. Marrying off a female child was not unusual.

The Wititterlys are funny, especially the husband. He seems to take pride in his weak, delicate wife. She is all soul...she could be blown away! Pho!

The Wititterlys are funny, especially the husband. He seems to take pride in his weak, delicate wife. She is all soul...she could be blown away! Pho!The scene where the wife was screaming on the sofa and the husband was dancing around her wondering what to do was comical and would make a good theater scene.

It is your poetical temperament, my dear—your ethereal soul—your fervid imagination, which throws you into a glow of genius and excitement.

The snuff of a candle, the wick of a lamp, the bloom on a peach, the down on a butterfly. You might blow her away, my lord; you might blow her away.’

What is this talk of candles, snuff, and being blown away? Is Mrs. Wititterly supposed to represent a weak flame? The "titter" in Wititterly means to giggle in a suppressed or nervous way. Her doctor is Tumley Snuffim, which to me sounds like, "tumult snuffer," for when she gets too excited.

I'm listening to the Librivox free audio version of NN. The reader is "Czeckchris," and you can make of that what you will, but I think he is fantastic, and his Sir Mulberry is awesome. You just want to despise Mulberry from the reader's voice alone. Unfortunately, Czeckchris reads only through chapter 26, then others take over.

I'm listening to the Librivox free audio version of NN. The reader is "Czeckchris," and you can make of that what you will, but I think he is fantastic, and his Sir Mulberry is awesome. You just want to despise Mulberry from the reader's voice alone. Unfortunately, Czeckchris reads only through chapter 26, then others take over.PS: Librivox has 4 or 5 versions of NN, each with different readers. The one I'm listening to is the first in the list.

Alissa wrote: "Ralph's comment at the end, "selling a girl" as "match-making mothers do the same thing every day,” was thought-provoking, since it puts Mrs. Nickleby at the same level of evil as him. ..."

Alissa wrote: "Ralph's comment at the end, "selling a girl" as "match-making mothers do the same thing every day,” was thought-provoking, since it puts Mrs. Nickleby at the same level of evil as him. ..."This is good, Alissa.

I sometimes wonder if Mrs. Nickleby is as out of touch with reality as she presents herself to be. She walks into Kate's interview for the companion job and pretty much takes over. She doesn't sound out of touch then. Looking at her that way makes her truly evil.

Peter wrote: "There are several types of villains in the novel so far. Squeers was unabashedly cruel and vindictive. Ralph Nickleby is callous and calculating. Sir Mulberry Hawk is a schemer and a womanizer. Who do you find to be the worst? Of these three, do you think Dickens will rehabilitate any of them by the end of the novel? Why? ..."

Peter wrote: "There are several types of villains in the novel so far. Squeers was unabashedly cruel and vindictive. Ralph Nickleby is callous and calculating. Sir Mulberry Hawk is a schemer and a womanizer. Who do you find to be the worst? Of these three, do you think Dickens will rehabilitate any of them by the end of the novel? Why? ..."Pike and Pluck?

Well, the first two chapters of this section have taken a turn towards the sinister. When this is over where will Sir Mulberry Hawke reside on a list of Dickens most despised characters?

So, Peter, I guess you know who I think is worse. Of course, another visit to Squeers might change my mind. No, really, I'll stick with Hawke. The damage Squeers can do, as great as it can be, is still limited by his situation and temperament, but there is no end to the damage a person like Hawke can do.

Hawke has a talent for being a sneak.

My list of villains in NN is headed by Mr. Squeers, simply because he is exercising his power over little children, who have no way of defending themselves, while Ralph and Hawk at least concentrate on adult people. Sir Mulberry's preferred victims are rich gulls like Lord Verisopht, and I cannot help thinking that if somebody allows another person to take him in, then this person has only got himself to blame. But then we don't know why Lord Verisopht has become such a feeble-minded person without no capacity of judgment. Maybe, his parents kept the whole world away from him when he was growing up, and so now, he does not know any better?

Still, Squeers is the most abominable scoundrel to me but close at his heels, there is Haw, whereas - I must say - I do not really dislike Ralph as deeply as the other two.

Still, Squeers is the most abominable scoundrel to me but close at his heels, there is Haw, whereas - I must say - I do not really dislike Ralph as deeply as the other two.

Peter wrote: "What are we to think of Nicholas’s actions? To what extent do you think he was justified in not only not apologizing to Lenville - albeit for nominal slight - but in knocking Lenville down, lecturing Lenville, and then breaking his stick? Was this an over-reaction on Nicholas’s part?

In this scene we see that Nicholas has a temper, and that it can flair up quickly. Why do you think Dickens keeps demonstrating that Nicholas has a temper?"

I find it very interesting that you mention this point, Peter, because it was one little detail that made me fall foul of Nicholas, i.e. his breaking Lenville's stick and throwing the two halves on him. It was a humiliation that was no longer needed because, after all, he had already got the better of Lenville, and why should he then break his stick? Maybe, once again, there is some deeper symbolism behind this act? Can we read it as Nicholas's emasculating his opponent symbolically in front of all the spectators - there are ladies and gentlemen watching, and the ladies are all in favour of Nicholas, whereas the gentleman are all having it in for him. So, by symbolically emasculating Lenville (who is a future father), Nicholas is enhancing his own position with the ladies, whereas he sends a clear warning message to all the other gentlemen. - Is it too much to read this into the broken stick?

Apart from that, in the Middle Ages, or even earlier, in some European countries, it was usual to break a staff, or stick, above a comdemned person's head, which was a visual sign of this person having forfeited his life. I also felt reminded of this custom when reading the scene in NN.

Whatever hidden meaning there is (there may be none, after all), I did not like Nick doing this, and neither do I like his readiness to flare up about trifles. He has absolutely no sense of irony related with himself, but instead is a most pompous ass! Whose ears I would gladly box!

Why does Dickens make Nick so irascible? That's another good question, Peter ... Maybe, this makes it easier for the author to tell a good story, because after all, with Nick's short fuses, there is always trouble guaranteed, and it will never get boring. Another reason may be that by and by he will change and learn patience, but I can't see him do so as yet.

And then, I am reminded of Tobias Smollett's heroes, who also had their serious shortcomings, and as we know, Dickens, esp. the early Dickens, took a lot of inspiration from Smollett and his contemporaries.

In this scene we see that Nicholas has a temper, and that it can flair up quickly. Why do you think Dickens keeps demonstrating that Nicholas has a temper?"

I find it very interesting that you mention this point, Peter, because it was one little detail that made me fall foul of Nicholas, i.e. his breaking Lenville's stick and throwing the two halves on him. It was a humiliation that was no longer needed because, after all, he had already got the better of Lenville, and why should he then break his stick? Maybe, once again, there is some deeper symbolism behind this act? Can we read it as Nicholas's emasculating his opponent symbolically in front of all the spectators - there are ladies and gentlemen watching, and the ladies are all in favour of Nicholas, whereas the gentleman are all having it in for him. So, by symbolically emasculating Lenville (who is a future father), Nicholas is enhancing his own position with the ladies, whereas he sends a clear warning message to all the other gentlemen. - Is it too much to read this into the broken stick?

Apart from that, in the Middle Ages, or even earlier, in some European countries, it was usual to break a staff, or stick, above a comdemned person's head, which was a visual sign of this person having forfeited his life. I also felt reminded of this custom when reading the scene in NN.

Whatever hidden meaning there is (there may be none, after all), I did not like Nick doing this, and neither do I like his readiness to flare up about trifles. He has absolutely no sense of irony related with himself, but instead is a most pompous ass! Whose ears I would gladly box!

Why does Dickens make Nick so irascible? That's another good question, Peter ... Maybe, this makes it easier for the author to tell a good story, because after all, with Nick's short fuses, there is always trouble guaranteed, and it will never get boring. Another reason may be that by and by he will change and learn patience, but I can't see him do so as yet.

And then, I am reminded of Tobias Smollett's heroes, who also had their serious shortcomings, and as we know, Dickens, esp. the early Dickens, took a lot of inspiration from Smollett and his contemporaries.

Chapter 26 confronted me with a puzzle, I must confess, a very disturbing one at that. Remember that Hawk and Lord V. were just about to leave when Mrs. Nickleby chanced to call on Ralph, with a letter directed to him (another strange coincidence). And then our narrator goes on like this:

To me, it seems as though Newman really wants Ralph's visitors to become aware of Mrs. Nickleby's identity and he also wants them to meet her. Why else should he have abstained from his normal habit of showing newcomers in silently and having them wait for the preceding interview to end, and why else should he shout Mrs. Nickleby's name?

Now, I am asking myself, why Newman should want the two strangers to become aware of Mrs. Nickleby. Can he not imagine that a lady like her would be easy prey to a Hawk (pardon the pun)? I don't see any logical consistency in Newman's behaviour here. Or am I overlooking something?

"There had been a ring at the bell a few moments before, which was answered by Newman Noggs just as they reached the hall. In the ordinary course of business Newman would have either admitted the new-comer in silence, or have requested him or her to stand aside while the gentlemen passed out. But he no sooner saw who it was, than as if for some private reason of his own, he boldly departed from the established custom of Ralph's mansion in business hours, and looking towards the respectable trio who were approaching, cried in a loud and sonorous voice, 'Mrs. Nickleby!'

'Mrs. Nickleby!' cried Sir Mulberry Hawk, as his friend looked back, and stared him in the face."

To me, it seems as though Newman really wants Ralph's visitors to become aware of Mrs. Nickleby's identity and he also wants them to meet her. Why else should he have abstained from his normal habit of showing newcomers in silently and having them wait for the preceding interview to end, and why else should he shout Mrs. Nickleby's name?

Now, I am asking myself, why Newman should want the two strangers to become aware of Mrs. Nickleby. Can he not imagine that a lady like her would be easy prey to a Hawk (pardon the pun)? I don't see any logical consistency in Newman's behaviour here. Or am I overlooking something?

Newman doesn't know about Hawke's and Kate's encounter that I know of. I'm not sure how much that matters, but he doesn't. It's is a mystery.

Newman doesn't know about Hawke's and Kate's encounter that I know of. I'm not sure how much that matters, but he doesn't. It's is a mystery.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 26 confronted me with a puzzle, I must confess, a very disturbing one at that. Remember that Hawk and Lord V. were just about to leave when Mrs. Nickleby chanced to call on Ralph, with a le..."

I thought the same thing.

I thought the same thing.

Tristram wrote: "My list of villains in NN is headed by Mr. Squeers, simply because he is exercising his power over little children, who have no way of defending themselves, while Ralph and Hawk at least concentrat..."

Oh no! I agree.

Oh no! I agree.

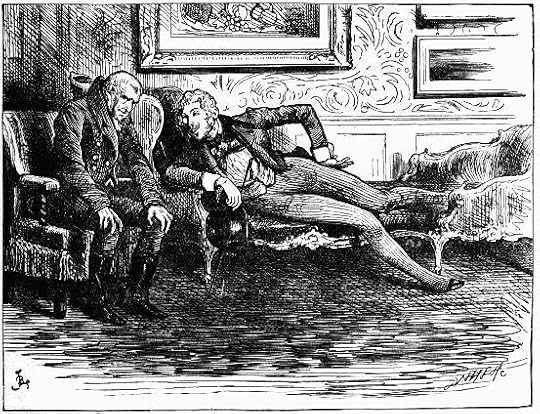

"Nickleby," said his client, throwing himself along the sofa on which he had been previously seated, so as to bring his lips nearer to the old man's ear, "What a pretty creature your niece is!"

Chapter 26

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

They found Ralph at home, and alone. As he led them into the drawing-room, the recollection of the scene which had taken place there seemed to occur to him, for he cast a curious look at Sir Mulberry, who bestowed upon it no other acknowledgment than a careless smile.

They had a short conference upon some money matters then in progress, which were scarcely disposed of when the lordly dupe (in pursuance of his friend’s instructions) requested with some embarrassment to speak to Ralph alone.

‘Alone, eh?’ cried Sir Mulberry, affecting surprise. ‘Oh, very good. I’ll walk into the next room here. Don’t keep me long, that’s all.’

So saying, Sir Mulberry took up his hat, and humming a fragment of a song disappeared through the door of communication between the two drawing-rooms, and closed it after him.

‘Now, my lord,’ said Ralph, ‘what is it?’

‘Nickleby,’ said his client, throwing himself along the sofa on which he had been previously seated, so as to bring his lips nearer to the old man’s ear, ‘what a pretty creature your niece is!’

‘Is she, my lord?’ replied Ralph. ‘Maybe—maybe—I don’t trouble my head with such matters.’

‘You know she’s a deyvlish fine girl,’ said the client. ‘You must know that, Nickleby. Come, don’t deny that.’

‘Yes, I believe she is considered so,’ replied Ralph. ‘Indeed, I know she is. If I did not, you are an authority on such points, and your taste, my lord—on all points, indeed—is undeniable.’

Nobody but the young man to whom these words were addressed could have been deaf to the sneering tone in which they were spoken, or blind to the look of contempt by which they were accompanied. But Lord Frederick Verisopht was both, and took them to be complimentary.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘p’raps you’re a little right, and p’raps you’re a little wrong—a little of both, Nickleby. I want to know where this beauty lives, that I may have another peep at her, Nickleby.’

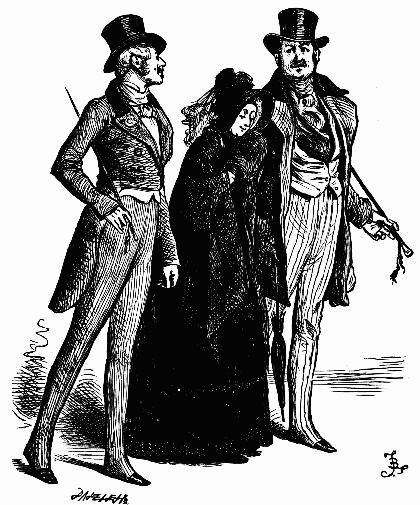

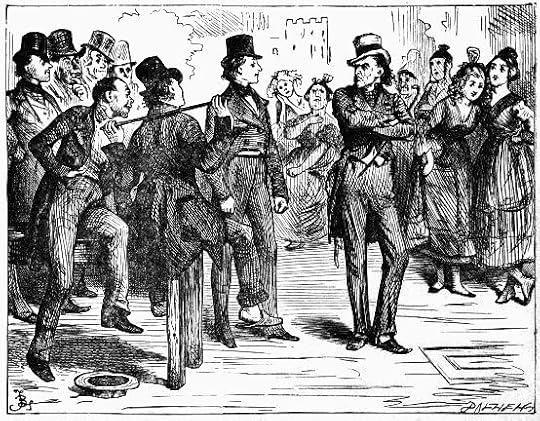

Sir Mulberry Hawk and his friend exchanged glances over the top of the bonnet

Chapter 26

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘For you, brother-in-law,’ replied Mrs. Nickleby, ‘and I walked all the way up here on purpose to give it you.’

‘All the way up here!’ cried Sir Mulberry, seizing upon the chance of discovering where Mrs. Nickleby had come from. ‘What a confounded distance! How far do you call it now?’

‘How far do I call it?’ said Mrs. Nickleby. ‘Let me see. It’s just a mile from our door to the Old Bailey.’

‘No, no. Not so much as that,’ urged Sir Mulberry.

‘Oh! It is indeed,’ said Mrs. Nickleby. ‘I appeal to his lordship.’

‘I should decidedly say it was a mile,’ remarked Lord Frederick, with a solemn aspect.

‘It must be; it can’t be a yard less,’ said Mrs. Nickleby. ‘All down Newgate Street, all down Cheapside, all up Lombard Street, down Gracechurch Street, and along Thames Street, as far as Spigwiffin’s Wharf. Oh! It’s a mile.’

‘Yes, on second thoughts I should say it was,’ replied Sir Mulberry. ‘But you don’t surely mean to walk all the way back?’

‘Oh, no,’ rejoined Mrs. Nickleby. ‘I shall go back in an omnibus. I didn’t travel about in omnibuses, when my poor dear Nicholas was alive, brother-in-law. But as it is, you know—’

‘Yes, yes,’ replied Ralph impatiently, ‘and you had better get back before dark.’

‘Thank you, brother-in-law, so I had,’ returned Mrs. Nickleby. ‘I think I had better say goodbye, at once.’

‘Not stop and—rest?’ said Ralph, who seldom offered refreshments unless something was to be got by it.

‘Oh dear me no,’ returned Mrs. Nickleby, glancing at the dial.

‘Lord Frederick,’ said Sir Mulberry, ‘we are going Mrs. Nickleby’s way. We’ll see her safe to the omnibus?’

‘By all means. Ye-es.’

‘Oh! I really couldn’t think of it!’ said Mrs. Nickleby.

But Sir Mulberry Hawk and Lord Verisopht were peremptory in their politeness, and leaving Ralph, who seemed to think, not unwisely, that he looked less ridiculous as a mere spectator, than he would have done if he had taken any part in these proceedings, they quitted the house with Mrs Nickleby between them; that good lady in a perfect ecstasy of satisfaction, no less with the attentions shown her by two titled gentlemen, than with the conviction that Kate might now pick and choose, at least between two large fortunes, and most unexceptionable husbands.

As she was carried away for the moment by an irresistible train of thought, all connected with her daughter’s future greatness, Sir Mulberry Hawk and his friend exchanged glances over the top of the bonnet which the poor lady so much regretted not having left at home, and proceeded to dilate with great rapture, but much respect on the manifold perfections of Miss Nickleby.

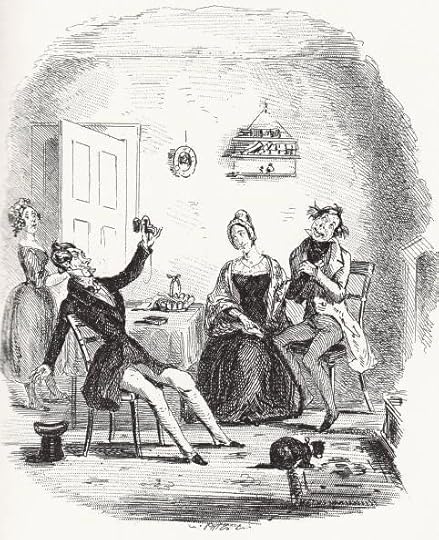

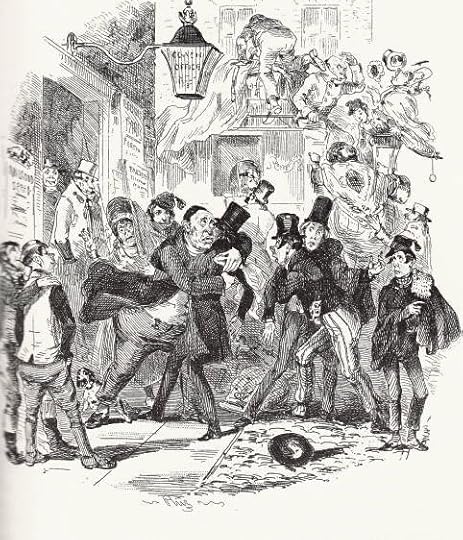

Affectionate Behaviour of Messrs. Pyke and Pluck

Chapter 27

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Hah!’ cried Mr. Pyke at this juncture, snatching something from the chimney-piece with a theatrical air. ‘What is this! what do I behold!’

‘What do you behold, my dear fellow?’ asked Mr. Pluck.

‘It is the face, the countenance, the expression,’ cried Mr. Pyke, falling into his chair with a miniature in his hand; ‘feebly portrayed, imperfectly caught, but still the face, the countenance, the expression.’

‘I recognise it at this distance!’ exclaimed Mr. Pluck in a fit of enthusiasm. ‘Is it not, my dear madam, the faint similitude of—’

‘It is my daughter’s portrait,’ said Mrs. Nickleby, with great pride. And so it was. And little Miss La Creevy had brought it home for inspection only two nights before.

Mr. Pyke no sooner ascertained that he was quite right in his conjecture, than he launched into the most extravagant encomiums of the divine original; and in the warmth of his enthusiasm kissed the picture a thousand times, while Mr. Pluck pressed Mrs. Nickleby’s hand to his heart, and congratulated her on the possession of such a daughter, with so much earnestness and affection, that the tears stood, or seemed to stand, in his eyes. Poor Mrs. Nickleby, who had listened in a state of enviable complacency at first, became at length quite overpowered by these tokens of regard for, and attachment to, the family; and even the servant girl, who had peeped in at the door, remained rooted to the spot in astonishment at the ecstasies of the two friendly visitors.

By degrees these raptures subsided, and Mrs. Nickleby went on to entertain her guests with a lament over her fallen fortunes, and a picturesque account of her old house in the country: comprising a full description of the different apartments, not forgetting the little store-room, and a lively recollection of how many steps you went down to get into the garden, and which way you turned when you came out at the parlour door, and what capital fixtures there were in the kitchen. This last reflection naturally conducted her into the wash-house, where she stumbled upon the brewing utensils, among which she might have wandered for an hour, if the mere mention of those implements had not, by an association of ideas, instantly reminded Mr. Pyke that he was ‘amazing thirsty.’

‘And I’ll tell you what,’ said Mr. Pyke; ‘if you’ll send round to the public-house for a pot of milk half-and-half, positively and actually I’ll drink it.’

And positively and actually Mr. Pyke did drink it, and Mr. Pluck helped him, while Mrs. Nickleby looked on in divided admiration of the condescension of the two, and the aptitude with which they accommodated themselves to the pewter-pot; in explanation of which seeming marvel it may be here observed, that gentlemen who, like Messrs Pyke and Pluck, live upon their wits (or not so much, perhaps, upon the presence of their own wits as upon the absence of wits in other people) are occasionally reduced to very narrow shifts and straits, and are at such periods accustomed to regale themselves in a very simple and primitive manner.

Commentary:

This plate further conveys Dickens' and Phiz's vision of a confusion between appearance and reality. In "Affectionate behaviour of Messrs. Pyke & Pluck" (ch. 27), Sir Mulberry's two henchmen are performing for the benefit of Mrs. Nickleby, who in her stupidity — which is actually stereotyped behavior operating as a defense against reality of course does not know it is a performance.

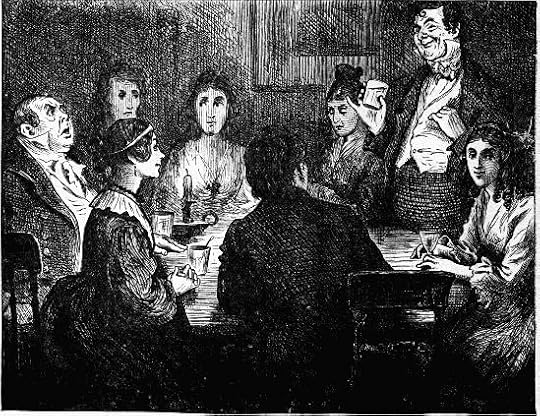

"I see how it is," said poor Noggs, drawing from his pocket what seemed to be a very old duster, and wiping Kate's eyes with it as gently as if she were an infant.

Chapter 28

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘I don’t say,’ rejoined Ralph, raising his forefinger, ‘but that you do right to despise them; no, you show your good sense in that, as indeed I knew from the first you would. Well. In all other respects you are comfortably bestowed. It’s not much to bear. If this young lord does dog your footsteps, and whisper his drivelling inanities in your ears, what of it? It’s a dishonourable passion. So be it; it won’t last long. Some other novelty will spring up one day, and you will be released. In the mean time—’

‘In the mean time,’ interrupted Kate, with becoming pride and indignation, ‘I am to be the scorn of my own sex, and the toy of the other; justly condemned by all women of right feeling, and despised by all honest and honourable men; sunken in my own esteem, and degraded in every eye that looks upon me. No, not if I work my fingers to the bone, not if I am driven to the roughest and hardest labour. Do not mistake me. I will not disgrace your recommendation. I will remain in the house in which it placed me, until I am entitled to leave it by the terms of my engagement; though, mind, I see these men no more. When I quit it, I will hide myself from them and you, and, striving to support my mother by hard service, I will live, at least, in peace, and trust in God to help me.’

With these words, she waved her hand, and quitted the room, leaving Ralph Nickleby motionless as a statue.

The surprise with which Kate, as she closed the room-door, beheld, close beside it, Newman Noggs standing bolt upright in a little niche in the wall like some scarecrow or Guy Faux laid up in winter quarters, almost occasioned her to call aloud. But, Newman laying his finger upon his lips, she had the presence of mind to refrain.

‘Don’t,’ said Newman, gliding out of his recess, and accompanying her across the hall. ‘Don’t cry, don’t cry.’ Two very large tears, by-the-bye, were running down Newman’s face as he spoke.

‘I see how it is,’ said poor Noggs, drawing from his pocket what seemed to be a very old duster, and wiping Kate’s eyes with it, as gently as if she were an infant. ‘You’re giving way now. Yes, yes, very good; that’s right, I like that. It was right not to give way before him. Yes, yes! Ha, ha, ha! Oh, yes. Poor thing!’

With these disjointed exclamations, Newman wiped his own eyes with the afore-mentioned duster, and, limping to the street-door, opened it to let her out.

‘Don’t cry any more,’ whispered Newman. ‘I shall see you soon. Ha! ha! ha! And so shall somebody else too. Yes, yes. Ho! ho!’

‘God bless you,’ answered Kate, hurrying out, ‘God bless you.’

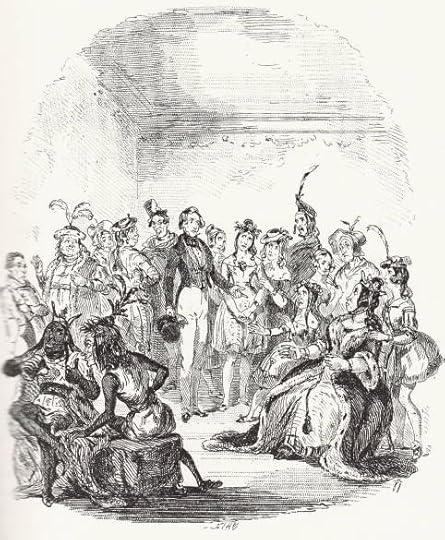

Nicholas Hints at the Probability of His Leaving the Company

Chapter 29

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"I have some reason to fear," interrupted Nicholas, "that before you leave here my career with you will have closed.

"Closed!" cried Mrs. Crummles, raising her hands in astonishment.

Closed!" cried Miss Snevellicci, trembling so much in her tights that she actually laid her hand upon the shoulder of the manageress for support.

"Why, he don't mean to say he's going!" exclaimed Mrs. Grudden, making her way towards Mrs. Crummles, "Hoity toity! Nonsense."

The phenomenon, being of an affectionate nature and moreover excitable, raised a loud cry, and Miss Belvawney and Miss Bravassa actually shed tears. Even the male performers stopped in their conversation, and echoed the word "Going!" although some among them (and they had been the loudest in their congratulations that day) winked at each other as though they would not be sorry to lose such a favoured rival. . . .

Commentary:

Nicholas and Smike, centre, stand out from the rest of the company by virtue of the fact that they are in street clothes rather than costume. Appropriately, Mrs. Crummles (right foreground) is dressed as a Renaissance queen, and her husband (centre, left) as a Renaissance monarch. As in the letterpress, the young women seem far more concerned than the young men of the company about the prospect of Nicholas's leaving.

The falsity of Pyke and Pluck (who are after all only acting out their everyday roles) contrasts with the range of genuine emotion expressed by the costumed actors in the companion plate, "Nicholas hints at the probability of his leaving the company" (ch. 29). Mrs. Crummles' costume as a queen does not prevent her surprise and consternation from seeming genuine, nor do their disguises as savage and demon conceal the glee of the two actors at lower left at the prospective departure of their rival. As usual, Nicholas has the stagiest expression of all, and he is not even in stage dress.

"But they shall not protect ye!" said the tragedian

Chapter 29

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

As Mr. Folair was pretty well known among his fellow-actors for a man who delighted in mischief, and was by no means scrupulous, Nicholas had not much doubt but that he had secretly prompted the tragedian in the course he had taken, and, moreover, that he would have carried his mission with a very high hand if he had not been disconcerted by the very unexpected demonstrations with which it had been received. It was not worth his while to be serious with him, however, so he dismissed the pantomimist, with a gentle hint that if he offended again it would be under the penalty of a broken head; and Mr. Folair, taking the caution in exceedingly good part, walked away to confer with his principal, and give such an account of his proceedings as he might think best calculated to carry on the joke.

He had no doubt reported that Nicholas was in a state of extreme bodily fear; for when that young gentleman walked with much deliberation down to the theatre next morning at the usual hour, he found all the company assembled in evident expectation, and Mr. Lenville, with his severest stage face, sitting majestically on a table, whistling defiance.

Now the ladies were on the side of Nicholas, and the gentlemen (being jealous) were on the side of the disappointed tragedian; so that the latter formed a little group about the redoubtable Mr. Lenville, and the former looked on at a little distance in some trepidation and anxiety. On Nicholas stopping to salute them, Mr. Lenville laughed a scornful laugh, and made some general remark touching the natural history of puppies.

‘Oh!’ said Nicholas, looking quietly round, ‘are you there?’

‘Slave!’ returned Mr. Lenville, flourishing his right arm, and approaching Nicholas with a theatrical stride. But somehow he appeared just at that moment a little startled, as if Nicholas did not look quite so frightened as he had expected, and came all at once to an awkward halt, at which the assembled ladies burst into a shrill laugh.

‘Object of my scorn and hatred!’ said Mr. Lenville, ‘I hold ye in contempt.’

Nicholas laughed in very unexpected enjoyment of this performance; and the ladies, by way of encouragement, laughed louder than before; whereat Mr Lenville assumed his bitterest smile, and expressed his opinion that they were ‘minions’.

‘But they shall not protect ye!’ said the tragedian, taking an upward look at Nicholas, beginning at his boots and ending at the crown of his head, and then a downward one, beginning at the crown of his head, and ending at his boots—which two looks, as everybody knows, express defiance on the stage. ‘They shall not protect ye—boy!’

Thus speaking, Mr. Lenville folded his arms, and treated Nicholas to that expression of face with which, in melodramatic performances, he was in the habit of regarding the tyrannical kings when they said, ‘Away with him to the deepest dungeon beneath the castle moat;’ and which, accompanied with a little jingling of fetters, had been known to produce great effects in its time.