The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Nicholas Nickleby

>

NN Chapters 46-50

NN Chapter 47

This is one of the chapters that, to paraphrase the fat boy from Pickwick Papers, makes my flesh creep. I doubt if we need any more convincing how evil Ralph Nickleby is, but this chapter should put all doubts to rest.

The chapter begins with Newman Noggs complaining about his employer: “I don’t believe he ever had an appetite ... except for pounds, shillings, and pence, and with them he’s as greedy as a wolf.” With this declaration, he prepares to do a bit of shadow boxing to release some of his frustration and anger. Newman then hears Ralph returning to the office with someone and decides to hid in a closet rather than be detained by any of Ralph Nickleby’s requests.

Ralph Nickleby enters the room with someone whose name is Gride who is described as “a little old man, of about seventy or seventy-five years of age, of a very lean figure, much bent, and slightly twisted.” Dickens continues to describe Gride’s clothes, his jewelry, and even the fact that he has lost many teeth. All in all, a rather revolting character who seems to spend much time flattering Ralph. Like Ralph Nickleby, Gride is a man of questionable business ethics. In the scene, Dickens seats Gride on a stool so that he must “look up into the face of Nickleby.” All in all, a wonderfully effective description of an odious character and the fact that Ralph is even more odious. Nickleby senses that Gride must be here for some business reason. Gride continues to heap praise on Nickleby by saying that Ralph is “a giant among pigmies.” Gride then tells Nickleby that he plans to marry “a young, and beautiful girl; fresh, lovely, bewitching, and not nineteen.” Ralph demands to know her name. Gride answers “Madeline Bray.”

Thoughts

Newman Noggs has been a very important minor character in the novel, but the fact he overhears the conversation between Gride and Nickleby is perhaps his most important function so far. What are your feelings about Nogg’s role so far in the novel? What other minor characters have impressed you to date in terms of their description, their interactions with major characters, their role in advancing the plot, or any other point of interest you have as a reader?

I found the description of Gride to be truly remarkable. He is physically repulsive and verbally annoying. Once again, Dickens employs a verbal tag to link a person to a unique dialect, pattern of speech, or specific word. Why would Dickens do this? To what extinct do you think the technique is effective? Could such a technique be overused in this novel? Can you recall any other novel that you have read where you found the verbal tag to have been used to great success or been overwhelmingly annoying?

When Gride states that he intends to marry Madeline Bray, I imagine some Curiosities might have gasped in disbelief. What a plot twist! What was your reaction to this latest plot development?

I found some irony in the fact that Newman Noggs has overheard the conversation. This is the young lady Newman was to have followed home for Nicholas. Now she is mentioned as a potential bride for a business associate of his uncle. We now have Ralph Nickleby not only attempting to despoil his niece’s character but also get involved in a scheme to help Gride buy Madeline Bray. What is your response to this turn of events?

Ralph hears Gride’s plan. Gride and Ralph are both owed money by Walter Bray. His daughter Madeline is devoted to her father and is “a slave to every wish, of her only parent.” Walter Bray loves himself more than he loves his daughter. Gride wants Madeline for his wife and wants to strike a deal with Ralph Nickleby by buying the debt Bray owes Nickleby. Nickleby counters with the fact that he wants full price for the debt he holds and, in addition, wants £500 more to help negotiate the union of Bray’s daughter with Gride. Nickleby wants this deal completed the day before the marriage. Gride consents to these stipulations. Off go Ralph Nickleby and Gride to the Bray’s lodgings and Newman Noggs emerges from his hiding place with full knowledge of this despicable plan.

Thoughts

First we had Squeers and the horrid Dotheboys Hall. Now we have Nickleby and his financial house of horrors. For a young author, Dickens seems to contain much anger. How might we account for it?

There seems to be no end to Ralph Nickleby’s desire to make money. In two major incidences we have read about so far, that of Kate and now Madeline, young innocent women are the victims of greed and schemes to make money. To what extent do you think Dickens intended to focus his writing in this manner? What might other reasons be for Dickens’s focus?

When Nickleby and Gride put their proposal to Bray, he plays the role of an aristocrat, a man of high principles and stature. What a sham. Bray’s response to Nickleby and Gride “you have money, and Miss Madeline has beauty and worth. She has youth, you have money. She has no money, you have not youth. Tit for tat - quits - a match” is repulsive. Bray’s feigning of status is as hollow as his present pockets. What is disconcerting are Ralph’s arguments about how often such financial marriages are made to “strengthen some family interest, or secure some seat in Parliament.” So horrid a thought, and yet, sadly, so common and true. Dickens here is at his best. His point is made. It sits for all Victorian readers to read and reflect upon.

Madeline, aware of what is occurring, remains silent. I would suggest, however, that Dickens may have embedded some subliminal sexual commentary in the chapter through his word selection. Dickens has Gride observe about Madeline that she is “a dainty morsel” to which Ralph responds “I have no great taste for beauty.” Gride replies “but I have ... . Oh, dear! How handsome her eyes looked when she was stooping over him - such long lashes - such delicate fringe! She - she looked at me so soft.” Gride sees Madeline as a morsel to be consumed.

Ralph responds “with a sneer, and between his teeth - .” Did you notice how this chapter began with a discussion of food and consumption? When Newman Noggs, at the beginning of the chapter, commented of Ralph Nickleby that “I don’t believe he ever had an appetite” he is referring to food. We know that Ralph’s appetite is only for money. He is willing to pimp out Kate to Verisopht and he is only too happy to act as a mediator to put Madeline Bray in the clutches of Gride. The only compliment that Nickleby pays Gride, and it is one cruelty delivered, occurs when he says Gride has “ripe lips and clustering hair.” This phrase seems out of place until it is placed within the context of this chapter’s ending.

Thoughts

To what extent do you see this chapter as the most horrific of all the chapters in the novel thus far?

We have touched on the possible subdued references to sexuality in this novel. Do you see any merit in my comments?

This is one of the chapters that, to paraphrase the fat boy from Pickwick Papers, makes my flesh creep. I doubt if we need any more convincing how evil Ralph Nickleby is, but this chapter should put all doubts to rest.

The chapter begins with Newman Noggs complaining about his employer: “I don’t believe he ever had an appetite ... except for pounds, shillings, and pence, and with them he’s as greedy as a wolf.” With this declaration, he prepares to do a bit of shadow boxing to release some of his frustration and anger. Newman then hears Ralph returning to the office with someone and decides to hid in a closet rather than be detained by any of Ralph Nickleby’s requests.

Ralph Nickleby enters the room with someone whose name is Gride who is described as “a little old man, of about seventy or seventy-five years of age, of a very lean figure, much bent, and slightly twisted.” Dickens continues to describe Gride’s clothes, his jewelry, and even the fact that he has lost many teeth. All in all, a rather revolting character who seems to spend much time flattering Ralph. Like Ralph Nickleby, Gride is a man of questionable business ethics. In the scene, Dickens seats Gride on a stool so that he must “look up into the face of Nickleby.” All in all, a wonderfully effective description of an odious character and the fact that Ralph is even more odious. Nickleby senses that Gride must be here for some business reason. Gride continues to heap praise on Nickleby by saying that Ralph is “a giant among pigmies.” Gride then tells Nickleby that he plans to marry “a young, and beautiful girl; fresh, lovely, bewitching, and not nineteen.” Ralph demands to know her name. Gride answers “Madeline Bray.”

Thoughts

Newman Noggs has been a very important minor character in the novel, but the fact he overhears the conversation between Gride and Nickleby is perhaps his most important function so far. What are your feelings about Nogg’s role so far in the novel? What other minor characters have impressed you to date in terms of their description, their interactions with major characters, their role in advancing the plot, or any other point of interest you have as a reader?

I found the description of Gride to be truly remarkable. He is physically repulsive and verbally annoying. Once again, Dickens employs a verbal tag to link a person to a unique dialect, pattern of speech, or specific word. Why would Dickens do this? To what extinct do you think the technique is effective? Could such a technique be overused in this novel? Can you recall any other novel that you have read where you found the verbal tag to have been used to great success or been overwhelmingly annoying?

When Gride states that he intends to marry Madeline Bray, I imagine some Curiosities might have gasped in disbelief. What a plot twist! What was your reaction to this latest plot development?

I found some irony in the fact that Newman Noggs has overheard the conversation. This is the young lady Newman was to have followed home for Nicholas. Now she is mentioned as a potential bride for a business associate of his uncle. We now have Ralph Nickleby not only attempting to despoil his niece’s character but also get involved in a scheme to help Gride buy Madeline Bray. What is your response to this turn of events?

Ralph hears Gride’s plan. Gride and Ralph are both owed money by Walter Bray. His daughter Madeline is devoted to her father and is “a slave to every wish, of her only parent.” Walter Bray loves himself more than he loves his daughter. Gride wants Madeline for his wife and wants to strike a deal with Ralph Nickleby by buying the debt Bray owes Nickleby. Nickleby counters with the fact that he wants full price for the debt he holds and, in addition, wants £500 more to help negotiate the union of Bray’s daughter with Gride. Nickleby wants this deal completed the day before the marriage. Gride consents to these stipulations. Off go Ralph Nickleby and Gride to the Bray’s lodgings and Newman Noggs emerges from his hiding place with full knowledge of this despicable plan.

Thoughts

First we had Squeers and the horrid Dotheboys Hall. Now we have Nickleby and his financial house of horrors. For a young author, Dickens seems to contain much anger. How might we account for it?

There seems to be no end to Ralph Nickleby’s desire to make money. In two major incidences we have read about so far, that of Kate and now Madeline, young innocent women are the victims of greed and schemes to make money. To what extent do you think Dickens intended to focus his writing in this manner? What might other reasons be for Dickens’s focus?

When Nickleby and Gride put their proposal to Bray, he plays the role of an aristocrat, a man of high principles and stature. What a sham. Bray’s response to Nickleby and Gride “you have money, and Miss Madeline has beauty and worth. She has youth, you have money. She has no money, you have not youth. Tit for tat - quits - a match” is repulsive. Bray’s feigning of status is as hollow as his present pockets. What is disconcerting are Ralph’s arguments about how often such financial marriages are made to “strengthen some family interest, or secure some seat in Parliament.” So horrid a thought, and yet, sadly, so common and true. Dickens here is at his best. His point is made. It sits for all Victorian readers to read and reflect upon.

Madeline, aware of what is occurring, remains silent. I would suggest, however, that Dickens may have embedded some subliminal sexual commentary in the chapter through his word selection. Dickens has Gride observe about Madeline that she is “a dainty morsel” to which Ralph responds “I have no great taste for beauty.” Gride replies “but I have ... . Oh, dear! How handsome her eyes looked when she was stooping over him - such long lashes - such delicate fringe! She - she looked at me so soft.” Gride sees Madeline as a morsel to be consumed.

Ralph responds “with a sneer, and between his teeth - .” Did you notice how this chapter began with a discussion of food and consumption? When Newman Noggs, at the beginning of the chapter, commented of Ralph Nickleby that “I don’t believe he ever had an appetite” he is referring to food. We know that Ralph’s appetite is only for money. He is willing to pimp out Kate to Verisopht and he is only too happy to act as a mediator to put Madeline Bray in the clutches of Gride. The only compliment that Nickleby pays Gride, and it is one cruelty delivered, occurs when he says Gride has “ripe lips and clustering hair.” This phrase seems out of place until it is placed within the context of this chapter’s ending.

Thoughts

To what extent do you see this chapter as the most horrific of all the chapters in the novel thus far?

We have touched on the possible subdued references to sexuality in this novel. Do you see any merit in my comments?

NN Chapter 48

I was happy to see that the epigraph to this chapter stated that Mr Crummles was going to be featured. I was equally saddened that apparently it was to be “Positively his last Appearance on this Stage.” Knowing Crummles as we do, final appearances are often less than final, so let’s see what’s up.

We begin the chapter by learning how much and how far Nicholas has fallen for Madeline and that he was “now conscious of much deeper and stronger feelings.” Nicholas intends to honour his vow to help her in any way he can. On his way home one evening he finds himself reading a “large play-bill hanging outside a Minor Theatre.” Much to his surprise he learns that he sees announced the “Positively ... last appearance of Mr Vincent Crummles of Provincial Celebrity.” Nicholas thinks to himself “surely it must be the same man ... . There can’t be be two Vincent Crummleses.” Indeed, it is THE Vincent Crummles.

Needless to say, Crummles was delighted to see Nicholas (aka. Mr Johnson) again. Nicholas learns that the Crummles are heading to America and that Mrs Crummles is expecting again, for the seventh time. I think this means that they will have more children than final performances. Crummles has hopes that his next child will have the genius for juvenile tragedy or the tight-rope. Nicholas learns that the farewell-supper in honour of the family is that night and he is invited to attend. Then comes what I believe to be a touch of Dickens stepping from the shadows of a writer to standing on a stage himself. First, he observes how theatres mingle the odours of “orange-peel, and gunpowder, which pervaded the hot and glaring theatre.” Surely this is Dickens, the actor and frequenter of the stage talking. Second, and I think much more predominantly, Nicholas finds himself in a rather animated discussion with a playwright who claims that fame occurs when he dramatizes a book “for its author.” Dickens, of course, was one of many novelists who suffered financially when their work was adapted for the stage by pirates who paid no royalty fees, and did not, in any way, recompense the original author. Nicholas, speaking in Dickens’s voice, comments:

“You drag within the magic circle of your dullness, subjects not at all adapted to the purposes of the stage, as he exalted. For instance, you take the uncompleted books of living authors, fresh from their hands, wet from the press, cut hack, and carve them to the powers and capacities of your actors, and the capacity of your theatres, finish unfinished works, hastily and crudely vamp up ideas not yet worked out by their original projector, but which have doubtless cost him many thoughtful days and sleepless nights ...”

I am using the Penguin edition of NN and a footnote to this part of the chapter expands on a personal feud between Dickens and a W.T.Moncrieff who was a playwright and a very bad offender and robber of Dickens’s original work.

Thoughts

Were you glad that Dickens included a chapter that tells the readers what had been happening to the Crummles and what their future was to be?

To what extent were you happy to see Dickens, through Nicholas, make very pointed comments about the plagiarism of his work? That said, should an author frequently use their platform as a writer to make a political, social, economic, or cultural comment so clearly and obviously?

Did you find the Crummles and the “theatrical” episodes of NN to have been a positive addition to the novel? Why or why not?

It’s fair to say, I think, that this discussion put a slight damper on part of the Crummles farewell proceedings. Nicholas presents each of the Crummles and their children with a parting gift. The farewell is heartfelt with a touch of the theatrical (we should expect no less from the Crummles troupe). And so Nicholas, with a wave of his hat, “took farewell of the Vincent Crummles.”

Thoughts

Our novel must be approaching its long glide path to its end as we bid the Crummles a fond farewell. Do you think they may well make yet another appearance, a curtain call, so to speak?

If this is truly a final farewell to the Crummles what did the chapters that featured them contribute to the overall structure of the novel?

In terms of speculation, who do you think Dickens will bid farewell to next? Why?

I was happy to see that the epigraph to this chapter stated that Mr Crummles was going to be featured. I was equally saddened that apparently it was to be “Positively his last Appearance on this Stage.” Knowing Crummles as we do, final appearances are often less than final, so let’s see what’s up.

We begin the chapter by learning how much and how far Nicholas has fallen for Madeline and that he was “now conscious of much deeper and stronger feelings.” Nicholas intends to honour his vow to help her in any way he can. On his way home one evening he finds himself reading a “large play-bill hanging outside a Minor Theatre.” Much to his surprise he learns that he sees announced the “Positively ... last appearance of Mr Vincent Crummles of Provincial Celebrity.” Nicholas thinks to himself “surely it must be the same man ... . There can’t be be two Vincent Crummleses.” Indeed, it is THE Vincent Crummles.

Needless to say, Crummles was delighted to see Nicholas (aka. Mr Johnson) again. Nicholas learns that the Crummles are heading to America and that Mrs Crummles is expecting again, for the seventh time. I think this means that they will have more children than final performances. Crummles has hopes that his next child will have the genius for juvenile tragedy or the tight-rope. Nicholas learns that the farewell-supper in honour of the family is that night and he is invited to attend. Then comes what I believe to be a touch of Dickens stepping from the shadows of a writer to standing on a stage himself. First, he observes how theatres mingle the odours of “orange-peel, and gunpowder, which pervaded the hot and glaring theatre.” Surely this is Dickens, the actor and frequenter of the stage talking. Second, and I think much more predominantly, Nicholas finds himself in a rather animated discussion with a playwright who claims that fame occurs when he dramatizes a book “for its author.” Dickens, of course, was one of many novelists who suffered financially when their work was adapted for the stage by pirates who paid no royalty fees, and did not, in any way, recompense the original author. Nicholas, speaking in Dickens’s voice, comments:

“You drag within the magic circle of your dullness, subjects not at all adapted to the purposes of the stage, as he exalted. For instance, you take the uncompleted books of living authors, fresh from their hands, wet from the press, cut hack, and carve them to the powers and capacities of your actors, and the capacity of your theatres, finish unfinished works, hastily and crudely vamp up ideas not yet worked out by their original projector, but which have doubtless cost him many thoughtful days and sleepless nights ...”

I am using the Penguin edition of NN and a footnote to this part of the chapter expands on a personal feud between Dickens and a W.T.Moncrieff who was a playwright and a very bad offender and robber of Dickens’s original work.

Thoughts

Were you glad that Dickens included a chapter that tells the readers what had been happening to the Crummles and what their future was to be?

To what extent were you happy to see Dickens, through Nicholas, make very pointed comments about the plagiarism of his work? That said, should an author frequently use their platform as a writer to make a political, social, economic, or cultural comment so clearly and obviously?

Did you find the Crummles and the “theatrical” episodes of NN to have been a positive addition to the novel? Why or why not?

It’s fair to say, I think, that this discussion put a slight damper on part of the Crummles farewell proceedings. Nicholas presents each of the Crummles and their children with a parting gift. The farewell is heartfelt with a touch of the theatrical (we should expect no less from the Crummles troupe). And so Nicholas, with a wave of his hat, “took farewell of the Vincent Crummles.”

Thoughts

Our novel must be approaching its long glide path to its end as we bid the Crummles a fond farewell. Do you think they may well make yet another appearance, a curtain call, so to speak?

If this is truly a final farewell to the Crummles what did the chapters that featured them contribute to the overall structure of the novel?

In terms of speculation, who do you think Dickens will bid farewell to next? Why?

NN Chapter 49

Our previous chapter was one of partings. In this chapter we turn to matters of the heart and glimmerings of love in the air or, believe it or not, up the chimney. The chapter begins with a tone of sadness, however, as we learn that Smike is in poor health. Naturally, Nicholas is concerned. Nicholas continues to execute his commissions to Madeleine Bray.

Smike’s condition is consumption and the notes in the Penguin Edition state that Dickens’s description “was considered so accurate that it was quoted verbatim in W. Aitken’s “Science and Practice of Medicine, 3rd ed., vol. 1 (1864) and in J. Miller’s “Principles of Surgery, 2nd ed. (1850). Impressive stuff. Upon reading this footnote I went back and reread Dickens’s description. I never knew the exact symptoms of consumption although I did know that many people died from the disease. Dickens’s phrase about this disease that be it “slow or quick, is ever sure and certain” was quite chilling. Given the treatment and past of Smike it is little wonder that he would be susceptible to consumption. Then, in a following paragraph of reflection, Dickens says that Nicholas will look back on this period of his life and dwell with a “pleasant sorrow upon every slight remembrance” of this time in his life. Personally, I found this paragraph powerful. To date, Nicholas has been somewhat prone to outbursts of temper or frustration. He may still show such emotion in future chapters. Yet here, I believe Dickens introduces a more reflective personality. Nicholas is becoming a much more rounded person.

Thoughts

Why might Dickens give the reader such a long and detailed description of consumption? How might Dickens link this description to Smike in the future?

Have you noticed any other instances recently where Nicholas’s character has been expressed in more mature actions, words, and thoughts? If so, why might Dickens be effecting such a change in Nicholas’s character?

The remainder of the chapter turns on a much happier note. Do I detect love in the air? The Cheeryble brothers continue to be kind and supportive of Nicholas. Indeed, we are told that they bestowed upon Nicholas every day some “new and substantial mark of kindness.” The brothers often visit the Nickleby home, as does Tim Linkinwater and Frank Cheeryble who appears at the Nickleby’s door “at least three nights in the week.” Mrs Nickleby notices Frank’s great attentiveness and the fact that Kate appears to blush when Frank or his name is mentioned in Kate’s presence. Mrs Nickleby, of course, assumes Ralph’s attentions are for her. Oh, Mrs Nickleby, your time will come in this chapter.

Miss La Creevy arrives at the Nickleby’s and announces that she has seen Mr Linkinwater with Frank Cheeryble. The Nickleby house seems attractive to many people. We further learn that when young Frank Cheeryble comes to the Nickleby home Smike tends to disappear. We soon learn that “quite a flirtation” sprung up between Miss La Creevy and Tim Linkinwater, Frank and Kate appear to enjoy a mutual opportunity to linger near each other. Whatever love dust may be in the air, our next lover makes a most dramatic entrance. We read that “romantic sounds ... proceeded from the throat of some man up the chimney, of whom nothing was visible but a pair of legs.” I love this part. We now have a scene where timid or temperate lovers are surpassed by Mrs Nickleby’s vegetable throwing lover who is attempting to come down their chimney to see her. Dickens makes much of this delightful scene. How could anyone not enjoy such a great setting? It reminds me of the grand frivolity of some sections of The Pickwick Papers. Mrs Nickleby rushes to explain that she has, in no way, encouraged such attention. Frank Cheeryble and Tim Linkinwater are speechless. Little wonder.

Assuming the role of a knight in shining armour, Frank asks if Mrs Nickleby “expected this old gentleman.” One wonders if Frank thought this was the normal and expected manner of Mrs Nickleby’s nocturnal visitor arriving at the house.

Thoughts

There was a convention of suitors, lovers, and hopeful romantics in this chapter. What was your favourite pairing, situation, and event?

In what ways has Dickens advanced the motifs and the combinations of lovers in this chapter?

Do you think the vegetable and chimney gentleman will become accepted by Mrs Nickleby by the end of the novel? Why or why not?

Our chapter winds down to a somber note as Nicholas and Kate visit Smike in his room. They find he has not undressed even though he has been in his room for hours. Smike will not tell them why he is feeling such melancholy except to comment that “My heart is very full;- you do not know how full it is.” The chapter ends with Smike looking at Kate and Nicholas “as if there was something in their strong affection which touched him very deeply.”

Thoughts

In your opinion, what is in Smike’s heart and mind?

Our previous chapter was one of partings. In this chapter we turn to matters of the heart and glimmerings of love in the air or, believe it or not, up the chimney. The chapter begins with a tone of sadness, however, as we learn that Smike is in poor health. Naturally, Nicholas is concerned. Nicholas continues to execute his commissions to Madeleine Bray.

Smike’s condition is consumption and the notes in the Penguin Edition state that Dickens’s description “was considered so accurate that it was quoted verbatim in W. Aitken’s “Science and Practice of Medicine, 3rd ed., vol. 1 (1864) and in J. Miller’s “Principles of Surgery, 2nd ed. (1850). Impressive stuff. Upon reading this footnote I went back and reread Dickens’s description. I never knew the exact symptoms of consumption although I did know that many people died from the disease. Dickens’s phrase about this disease that be it “slow or quick, is ever sure and certain” was quite chilling. Given the treatment and past of Smike it is little wonder that he would be susceptible to consumption. Then, in a following paragraph of reflection, Dickens says that Nicholas will look back on this period of his life and dwell with a “pleasant sorrow upon every slight remembrance” of this time in his life. Personally, I found this paragraph powerful. To date, Nicholas has been somewhat prone to outbursts of temper or frustration. He may still show such emotion in future chapters. Yet here, I believe Dickens introduces a more reflective personality. Nicholas is becoming a much more rounded person.

Thoughts

Why might Dickens give the reader such a long and detailed description of consumption? How might Dickens link this description to Smike in the future?

Have you noticed any other instances recently where Nicholas’s character has been expressed in more mature actions, words, and thoughts? If so, why might Dickens be effecting such a change in Nicholas’s character?

The remainder of the chapter turns on a much happier note. Do I detect love in the air? The Cheeryble brothers continue to be kind and supportive of Nicholas. Indeed, we are told that they bestowed upon Nicholas every day some “new and substantial mark of kindness.” The brothers often visit the Nickleby home, as does Tim Linkinwater and Frank Cheeryble who appears at the Nickleby’s door “at least three nights in the week.” Mrs Nickleby notices Frank’s great attentiveness and the fact that Kate appears to blush when Frank or his name is mentioned in Kate’s presence. Mrs Nickleby, of course, assumes Ralph’s attentions are for her. Oh, Mrs Nickleby, your time will come in this chapter.

Miss La Creevy arrives at the Nickleby’s and announces that she has seen Mr Linkinwater with Frank Cheeryble. The Nickleby house seems attractive to many people. We further learn that when young Frank Cheeryble comes to the Nickleby home Smike tends to disappear. We soon learn that “quite a flirtation” sprung up between Miss La Creevy and Tim Linkinwater, Frank and Kate appear to enjoy a mutual opportunity to linger near each other. Whatever love dust may be in the air, our next lover makes a most dramatic entrance. We read that “romantic sounds ... proceeded from the throat of some man up the chimney, of whom nothing was visible but a pair of legs.” I love this part. We now have a scene where timid or temperate lovers are surpassed by Mrs Nickleby’s vegetable throwing lover who is attempting to come down their chimney to see her. Dickens makes much of this delightful scene. How could anyone not enjoy such a great setting? It reminds me of the grand frivolity of some sections of The Pickwick Papers. Mrs Nickleby rushes to explain that she has, in no way, encouraged such attention. Frank Cheeryble and Tim Linkinwater are speechless. Little wonder.

Assuming the role of a knight in shining armour, Frank asks if Mrs Nickleby “expected this old gentleman.” One wonders if Frank thought this was the normal and expected manner of Mrs Nickleby’s nocturnal visitor arriving at the house.

Thoughts

There was a convention of suitors, lovers, and hopeful romantics in this chapter. What was your favourite pairing, situation, and event?

In what ways has Dickens advanced the motifs and the combinations of lovers in this chapter?

Do you think the vegetable and chimney gentleman will become accepted by Mrs Nickleby by the end of the novel? Why or why not?

Our chapter winds down to a somber note as Nicholas and Kate visit Smike in his room. They find he has not undressed even though he has been in his room for hours. Smike will not tell them why he is feeling such melancholy except to comment that “My heart is very full;- you do not know how full it is.” The chapter ends with Smike looking at Kate and Nicholas “as if there was something in their strong affection which touched him very deeply.”

Thoughts

In your opinion, what is in Smike’s heart and mind?

NN Chapter 50

In chapter 50 we have two more characters leave its pages. I, for one, disliked them greatly, but found they played a major role in furthering the plot and especially developing the characters of Ralph, Nicholas, and Kate Nickleby. I am speaking, of course, of Lord Verisopht and Sir Mulberry Hawk. Along with their exit I presume we will have seen the last of Pyke and Pluck as well. While these two were cads and free-loaders, they did amuse me. Have we seen any other characters who were able to confound Mrs Nickleby with such enjoyable results?

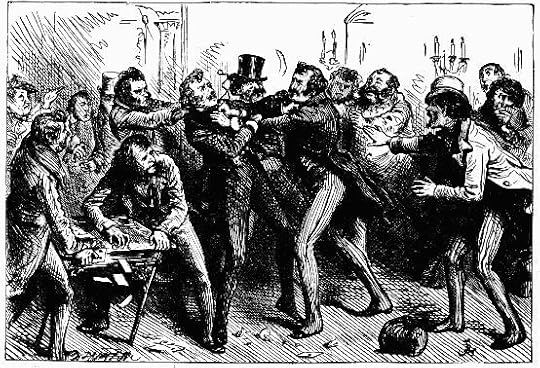

I found Chapter 50’s beginning a masterpiece of style. Dickens creates a picture-perfect setting. One can feel and sense and see the little race-course perfectly. The people and the place come alive to us. It’s at a time like this I wish I had an audio version. If you did listen to this chapter please let us know if it is as wonderful in an audio format as it is to read.

I also really enjoyed how Dickens transitions the reader from a larger view of the Hampton race-course to one that is more specific. How perfect is the sentence “It is into one of these booths that our story takes its way.” The reader feels he has just been invited by Dickens himself to experience a new focus. The focus of the booth is then also narrowed as Dickens’s words seeks out various individuals within the gambling booth. Next, as our eyes become accustomed to the booth, we observe Sir Mulberry Hawk “with whom were his friend and pupil, and a small train of gentlemanly-dressed men, of characters more doubtful than obscure.”

There is much interest in Hawk since he has not been in public since his confrontation with Nicholas. It appears that Hawk has never forgotten his thrashing and plans to remedy his injury and, no doubt, his reputation. Lord Verisopht is unsettled to hear that Hawk has plans for revenge, and presses Sir Mulberry for details. When none are forthcoming, Lord Verisopht strengthens somewhat and tells Hawk that he will prevent any violent recriminations against Nicholas. Hawk retorts that “I advise no man to interfere in the proceedings that I choose to take, and I am sure you know me better than to do so.” Hawk resolves to not only punish Nicholas but to make Verisopht pay for his attitude as well. Hawk has nothing but contempt for Verisopht. Indeed, Hawk hates Verisopht. Hawk and Verisopht leave the race-course, dine “sumptuously” and the “wine flowed freely.” Then they went to another party with “hot rooms, and glaring lights [and a] giddy whirl of noise and confusion.” Amid the cacophony of sight, sound, and liquor a fight breaks out and Hawk claims that Verisopht struck him.

Thoughts

Did you notice how Dickens drew his readers into this chapter? Beginning with a large panorama, we move slowly to the gambling tent, then inside, then to the characters of Hawk and Verisopht. As these movements occur we slowly begin to see an increase in the action and movement of Hawk and Verisopht. Then these individuals become irritated, then words are spoken, then wine, noise and a cacophony of action end with a physical assault.

How effective was Dickens in writing this setting in your opinion? What part of the setting did you find most/least enjoyable?

It is obvious that Verisopht has respect and true affection for Kate. To what extent does this effect the way you see him in comparison to Hawk?

Hawk has suffered one thrashing from Nicholas. How could this help explain his volatile anger and desire for revenge on Verisopht?

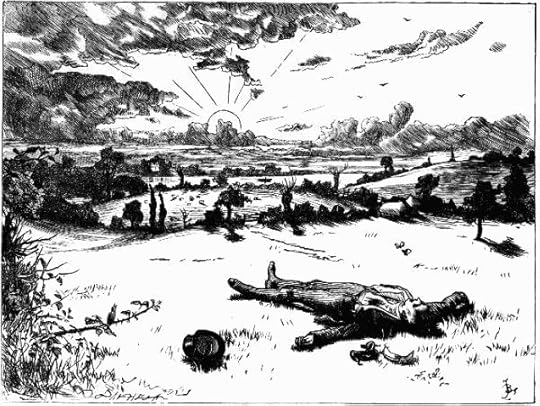

Hawk demands satisfaction from Verisopht for striking him. A duel appears to be the only way these men can resolve their differences. As we are told “a blow has been struck, and there is but one course, of course.” No one disagrees. The seconds are selected, the location chosen, and all that needs to be done is the meeting of the two combatants. Little else need be said. Both men fire “as nearly as possible at the same instant.” Verisopht is shot. He dies. Sir Mulberry Hawk flees the scene. The sun comes up. Two more of the characters in the novel have ended their time with us.

Thoughts

What do you think Kate’s feelings will be when she learns that a duel has been fought over her honour?

In the chapters we read this week Dickens has begun to narrow the cast of characters for us. First, the Crummles and the theatre troupe have left for America. In this chapter we have seen the characters of Hawk, Verisopht, Pyke and Pluck head into the wings of the novel’s theatre. Such events suggest that Dickens is clearing the stage so the major characters will have more room to evolve. Which character or groups of characters do you think will leave the pages of the novel next? Why?

Given the actions of Sir Mulberry Hawk towards Lord Verisopht do you have more sympathy for Verisopht or did he get what he deserved?

Hawk and Verisopht were quick to adopt the idea of a duel to solve their differences. Earlier in the novel Nicholas gave both Squeers and Sir Mulberry Hawk a beating. Xan raised the point of why there were no repercussions for Nicholas because of his actions to Hawk. Do you think, now that Hawk has his health again, he would have challenged Nicholas to a duel?

In chapter 50 we have two more characters leave its pages. I, for one, disliked them greatly, but found they played a major role in furthering the plot and especially developing the characters of Ralph, Nicholas, and Kate Nickleby. I am speaking, of course, of Lord Verisopht and Sir Mulberry Hawk. Along with their exit I presume we will have seen the last of Pyke and Pluck as well. While these two were cads and free-loaders, they did amuse me. Have we seen any other characters who were able to confound Mrs Nickleby with such enjoyable results?

I found Chapter 50’s beginning a masterpiece of style. Dickens creates a picture-perfect setting. One can feel and sense and see the little race-course perfectly. The people and the place come alive to us. It’s at a time like this I wish I had an audio version. If you did listen to this chapter please let us know if it is as wonderful in an audio format as it is to read.

I also really enjoyed how Dickens transitions the reader from a larger view of the Hampton race-course to one that is more specific. How perfect is the sentence “It is into one of these booths that our story takes its way.” The reader feels he has just been invited by Dickens himself to experience a new focus. The focus of the booth is then also narrowed as Dickens’s words seeks out various individuals within the gambling booth. Next, as our eyes become accustomed to the booth, we observe Sir Mulberry Hawk “with whom were his friend and pupil, and a small train of gentlemanly-dressed men, of characters more doubtful than obscure.”

There is much interest in Hawk since he has not been in public since his confrontation with Nicholas. It appears that Hawk has never forgotten his thrashing and plans to remedy his injury and, no doubt, his reputation. Lord Verisopht is unsettled to hear that Hawk has plans for revenge, and presses Sir Mulberry for details. When none are forthcoming, Lord Verisopht strengthens somewhat and tells Hawk that he will prevent any violent recriminations against Nicholas. Hawk retorts that “I advise no man to interfere in the proceedings that I choose to take, and I am sure you know me better than to do so.” Hawk resolves to not only punish Nicholas but to make Verisopht pay for his attitude as well. Hawk has nothing but contempt for Verisopht. Indeed, Hawk hates Verisopht. Hawk and Verisopht leave the race-course, dine “sumptuously” and the “wine flowed freely.” Then they went to another party with “hot rooms, and glaring lights [and a] giddy whirl of noise and confusion.” Amid the cacophony of sight, sound, and liquor a fight breaks out and Hawk claims that Verisopht struck him.

Thoughts

Did you notice how Dickens drew his readers into this chapter? Beginning with a large panorama, we move slowly to the gambling tent, then inside, then to the characters of Hawk and Verisopht. As these movements occur we slowly begin to see an increase in the action and movement of Hawk and Verisopht. Then these individuals become irritated, then words are spoken, then wine, noise and a cacophony of action end with a physical assault.

How effective was Dickens in writing this setting in your opinion? What part of the setting did you find most/least enjoyable?

It is obvious that Verisopht has respect and true affection for Kate. To what extent does this effect the way you see him in comparison to Hawk?

Hawk has suffered one thrashing from Nicholas. How could this help explain his volatile anger and desire for revenge on Verisopht?

Hawk demands satisfaction from Verisopht for striking him. A duel appears to be the only way these men can resolve their differences. As we are told “a blow has been struck, and there is but one course, of course.” No one disagrees. The seconds are selected, the location chosen, and all that needs to be done is the meeting of the two combatants. Little else need be said. Both men fire “as nearly as possible at the same instant.” Verisopht is shot. He dies. Sir Mulberry Hawk flees the scene. The sun comes up. Two more of the characters in the novel have ended their time with us.

Thoughts

What do you think Kate’s feelings will be when she learns that a duel has been fought over her honour?

In the chapters we read this week Dickens has begun to narrow the cast of characters for us. First, the Crummles and the theatre troupe have left for America. In this chapter we have seen the characters of Hawk, Verisopht, Pyke and Pluck head into the wings of the novel’s theatre. Such events suggest that Dickens is clearing the stage so the major characters will have more room to evolve. Which character or groups of characters do you think will leave the pages of the novel next? Why?

Given the actions of Sir Mulberry Hawk towards Lord Verisopht do you have more sympathy for Verisopht or did he get what he deserved?

Hawk and Verisopht were quick to adopt the idea of a duel to solve their differences. Earlier in the novel Nicholas gave both Squeers and Sir Mulberry Hawk a beating. Xan raised the point of why there were no repercussions for Nicholas because of his actions to Hawk. Do you think, now that Hawk has his health again, he would have challenged Nicholas to a duel?

Peter wrote: "This is one of the chapters that, to paraphrase the fat boy from Pickwick Papers, makes my flesh creep...."

Peter wrote: "This is one of the chapters that, to paraphrase the fat boy from Pickwick Papers, makes my flesh creep...."Me, too, Peter. Gride's overt lasciviousness made my skin crawl. Hollywood could learn a thing or two from Dickens. He showed his readers every disgusting desire Gride had, while mentioning only her eyelashes! Those Victorians were masters of innuendo.

I just loved the opening of this chapter, with Noggs grumbling about missing his meal, and being so hungry, then hiding in a closet when he hears Ralph approaching. It was so very human and honest! I'm trying to imagine Dickens at his desk, knowing he has to have Noggs overhear this conversation, and trying to determine how to make it happen. This was such a simple solution, but beautifully executed, in my opinion.

That said, I was frustrated when Dickens introduced yet another new character in a novel that is already heavily populated. I admit, it made my brain hurt a bit. I'm still trying to figure out the last associate of Ralph's whom he (and we) met a few chapters ago, and now we have Gride. At least Gride's place in the story seems more straightforward. But we have been dealt a whole new group of characters with Gride, the Brays, and the other guy whose name isn't coming to me. I hope the remaining chapters won't introduce any other new characters.

Peter wrote: "NN Chapter 46..."

Peter wrote: "NN Chapter 46..."Peter, as is so often the case, I enjoyed your summary of this chapter almost more than the chapter itself because you point out things I missed in my own reading. I so appreciate your insight and keen observations.

Was anyone else annoyed by Nicholas's expressions of adoration for Madeline? My gosh -- all he needed was a zucchini to toss in her direction! Madeline should have been thinking, "Geez, I've got enough problems with my bitter old father... I don't need a stalker whom I've never met before professing his 'love' for me!" Surprisingly, this doesn't seem to bother her. She's so grateful, I suppose, and trusts that the Cheerybles would only send someone upstanding that she's not the least bit creeped out by his declarations.

Peter wrote: "NN Chapter 48... Mr Crummles ...Positively his last Appear..."

Peter wrote: "NN Chapter 48... Mr Crummles ...Positively his last Appear..."In terms of speculation, who do you think Dickens will bid farewell to next? ..."

I was surprised that Nicholas didn't bring Smike along for his farewell with the acting troupe. Are we to assume he was too sick to join the party?

This makes me think we may be saying goodbye to Smike before much longer. I look forward to learning how Dickens will tie the loose ends of Smike's story together. I hope he won't disappoint me!

As you may remember, I'm not a fan of the "story within a story" and I think I put off reading NN all these years because I knew there was a theater troupe in the story, and I didn't like the idea of reading the plots of the plays they were producing, etc. I have been pleasantly surprised that there was so little of this, and that I found many of their scenes good comic relief -- particularly the infant phenomenon. :-) I couldn't tell you most of their names at this point, or much about most of them, but when they strut their hour upon this particular stage, I found them to be entertaining.

Peter wrote: "In chapter 50 we have two more characters leave its pages. I, for one, disliked them greatly, but found they played a major role in furthering the plot and especially developing the ..."

Peter wrote: "In chapter 50 we have two more characters leave its pages. I, for one, disliked them greatly, but found they played a major role in furthering the plot and especially developing the ..."The end of this chapter really took me by surprise! We saw a glimpse of Verisopht's backbone when Hawk was laid up, but I never thought he'd have the nerve to confront him again once he was ambulatory. A sad ending to Verisopht's story! Have we seen the end of Hawk? Seems like there should be at least one more encounter between him and the Nicklebys.

Peter's summation of Dickens' description of the race-course gave me a greater appreciation of it, but I've always preferred action and dialogue to descriptive passages, and this was no exception. I found our stroll through the attractions to the tent very tedious, and was relieved to finally get back to the meat of the story. FYI, Peter, I was listening to this bit in the car, and actually grumbled out loud to the reader to get on with it!

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "In chapter 50 we have two more characters leave its pages. I, for one, disliked them greatly, but found they played a major role in furthering the plot and especially developing the ...."

Hi Mary Lou

I always enjoy reading your thoughts and comments. Within them is much to consider and reflect upon. As to you grumbling in your car, I am sure it was a reasonably polite grumble.

For myself, I do enjoy Dickens’s descriptions of setting. While they do tend to stretch out a bit, I find his language and the manner in which he cascades ideas, thoughts and words and then links or joins everything to another part of the text amazing. How he kept all the chapters rolling along I will never understand, but I will enjoy poking around them with you and our fellow Curiosities.

Hi Mary Lou

I always enjoy reading your thoughts and comments. Within them is much to consider and reflect upon. As to you grumbling in your car, I am sure it was a reasonably polite grumble.

For myself, I do enjoy Dickens’s descriptions of setting. While they do tend to stretch out a bit, I find his language and the manner in which he cascades ideas, thoughts and words and then links or joins everything to another part of the text amazing. How he kept all the chapters rolling along I will never understand, but I will enjoy poking around them with you and our fellow Curiosities.

Peter wrote: "Dickens has Gride observe about Madeline that she is “a dainty morsel” to which Ralph responds “I have no great taste for beauty.” Gride replies “but I have ... . Oh, dear! How handsome her eyes looked when she was stooping over him - such long lashes - such delicate fringe! She - she looked at me so soft.” Gride sees Madeline as a morsel to be consumed..."

Peter wrote: "Dickens has Gride observe about Madeline that she is “a dainty morsel” to which Ralph responds “I have no great taste for beauty.” Gride replies “but I have ... . Oh, dear! How handsome her eyes looked when she was stooping over him - such long lashes - such delicate fringe! She - she looked at me so soft.” Gride sees Madeline as a morsel to be consumed..."Yuck! I agree about the innuendo. I see many parallels to when Kate was harassed by Hawk at Ralph's mansion. When Kate started reading, Hawk said something like, "is that to display the eyelashes?" What is it with the bad guys and eyelashes? Both scenes mixed food and lust too.

Alissa wrote: "Peter wrote: "Dickens has Gride observe about Madeline that she is “a dainty morsel” to which Ralph responds “I have no great taste for beauty.” Gride replies “but I have ... . Oh, dear! How handso..."

Hi Alissa

Yes. I think food and the consumption of it are both frequently linked to sexual suggestion in books. The woman’s body is something to be possessed and consumed by a male.

I am Canadian and one of our best authors is Margaret Atwood who wrote a novel titled “The Edible Woman.” Here is a link for you.

The Edible Woman

Hi Alissa

Yes. I think food and the consumption of it are both frequently linked to sexual suggestion in books. The woman’s body is something to be possessed and consumed by a male.

I am Canadian and one of our best authors is Margaret Atwood who wrote a novel titled “The Edible Woman.” Here is a link for you.

The Edible Woman

As always, Peter, your chapter summaries are very insightful and thought-provoking! I do agree that Dickens's descriptive passages are quite a treat in that they manage to create an atmosphere and also to give us a vivid impression of the setting. I was able to see the race-course and the raucous festivities in front of my inner eye. Still, I can also understand readers who are impatient for the action and the dialogue to go on - no matter how inveterate a fan of descriptions I am (provided they are given in an expressive and original style, which we can give Dickens credit for).

What I really start to dislike at this point is the way Dickens starts new sub-plots while, at the same time, he is putting other sub-plots to rest in a most awkward way. We see him introduce the old usurer Arthur Gride - and with him a new plot of a long-forgotten inheritance that only Gride has got wind of. At this stage, one may rightly ask how he has come to know about this. Introducing Gride and all the paraphernalia concerning his courtship of Madeline fills one entire chapter. If I were sarcastic, I'd say that Dickens wanted to fill some pages, or that he somehow had to account for that old villain's interest in the young woman - but, of course, I gently forbear being sarcastic.

At the same time, while he is introducing Gride, he has Sir Mulberry and Verisopht come back from abroad and then come up with that duel to give those two characters short shrift. Okay, a conflict between the Lord and his scrounger was on the cards because of their disagreeing about Hawk's treatment of Nicholas, but still, I could not help thinking that the whole chapter was written with a sense of not knowing how else to dispense with those two characters nor how to use them any further. They had already gone for France, and I had the impression that the only reason Dickens got them back was to kill off Lord V. and to have Sir M. leave the country for good. - This time, at least, Dr. Payne from PP would have been satisfied with the outcome of the whole affair, but I wasn't. Dealing with this villain and his dupe, who had both played quite an important role in the novel, in such a desultory manner is a thing that the Dickens of DaS and the novels following this one would never have done. It shows the young writer's difficulties with coming to terms with his plots.

And unluckily, Mary Lou, there will be yet another character introduced after Arthur Gride. Wait till next week ;-)

What I really start to dislike at this point is the way Dickens starts new sub-plots while, at the same time, he is putting other sub-plots to rest in a most awkward way. We see him introduce the old usurer Arthur Gride - and with him a new plot of a long-forgotten inheritance that only Gride has got wind of. At this stage, one may rightly ask how he has come to know about this. Introducing Gride and all the paraphernalia concerning his courtship of Madeline fills one entire chapter. If I were sarcastic, I'd say that Dickens wanted to fill some pages, or that he somehow had to account for that old villain's interest in the young woman - but, of course, I gently forbear being sarcastic.

At the same time, while he is introducing Gride, he has Sir Mulberry and Verisopht come back from abroad and then come up with that duel to give those two characters short shrift. Okay, a conflict between the Lord and his scrounger was on the cards because of their disagreeing about Hawk's treatment of Nicholas, but still, I could not help thinking that the whole chapter was written with a sense of not knowing how else to dispense with those two characters nor how to use them any further. They had already gone for France, and I had the impression that the only reason Dickens got them back was to kill off Lord V. and to have Sir M. leave the country for good. - This time, at least, Dr. Payne from PP would have been satisfied with the outcome of the whole affair, but I wasn't. Dealing with this villain and his dupe, who had both played quite an important role in the novel, in such a desultory manner is a thing that the Dickens of DaS and the novels following this one would never have done. It shows the young writer's difficulties with coming to terms with his plots.

And unluckily, Mary Lou, there will be yet another character introduced after Arthur Gride. Wait till next week ;-)

Mary Lou wrote: "Was anyone else annoyed by Nicholas's expressions of adoration for Madeline? My gosh -- all he needed was a zucchini to toss in her direction! Madeline should have been thinking, "Geez, I've got enough problems with my bitter old father... I don't need a stalker whom I've never met before professing his 'love' for me!" "

Yes, I was! But I was not surprised, knowing what a soft spot our Nick has for theatrical language and hammy climaxes. Fancy telling a woman who has never spoken two words with you that you would die to do her a service. She may take you at your word, even though the service merely be to have peace and quiet again.

I was very annoyed at how Mr. Bray treats his daughter - and I like Peter's idea that the stick with which he beats the ground can be seen as a sign that he even beats or used to beat his daugther, and probably also his wife. At the same time, I cannot see any reason why I should follow the narrator's obvious admiration for a young woman who submits herself to the tyranny of a self-seeking, petulous invalid simply because this man happens to be her father. This kind of father is not any better than those fathers (like Snawley) who leave their children with Mr. Squeers to get rid of them. In fact, he is probably worse because he keeps his daughter near him to sell her to a lecherous old crocodile, ensuring himself a life away from the necessity of seeing her pine under the duress of her new life.

There is no real merit in Madeline's readiness to sacrifice herself, although I know that in the eyes of many a Victorian reader this was regarded as exactly the thing a daughter was supposed to do.

Yes, I was! But I was not surprised, knowing what a soft spot our Nick has for theatrical language and hammy climaxes. Fancy telling a woman who has never spoken two words with you that you would die to do her a service. She may take you at your word, even though the service merely be to have peace and quiet again.

I was very annoyed at how Mr. Bray treats his daughter - and I like Peter's idea that the stick with which he beats the ground can be seen as a sign that he even beats or used to beat his daugther, and probably also his wife. At the same time, I cannot see any reason why I should follow the narrator's obvious admiration for a young woman who submits herself to the tyranny of a self-seeking, petulous invalid simply because this man happens to be her father. This kind of father is not any better than those fathers (like Snawley) who leave their children with Mr. Squeers to get rid of them. In fact, he is probably worse because he keeps his daughter near him to sell her to a lecherous old crocodile, ensuring himself a life away from the necessity of seeing her pine under the duress of her new life.

There is no real merit in Madeline's readiness to sacrifice herself, although I know that in the eyes of many a Victorian reader this was regarded as exactly the thing a daughter was supposed to do.

Peter wrote: "Newman Noggs has been a very important minor character in the novel, but the fact he overhears the conversation between Gride and Nickleby is perhaps his most important function so far."

The irony, however, is that - unlike the reader - Newman Noggs has no idea that the young lady whose future is bartered away here it the very lady that Nicholas adores because as yet Newman is ignorant of the name of Nicholas's beloved one, or isn't he?

The irony, however, is that - unlike the reader - Newman Noggs has no idea that the young lady whose future is bartered away here it the very lady that Nicholas adores because as yet Newman is ignorant of the name of Nicholas's beloved one, or isn't he?

Peter wrote: "Once again, Dickens employs a verbal tag to link a person to a unique dialect, pattern of speech, or specific word. Why would Dickens do this? To what extinct do you think the technique is effective? Could such a technique be overused in this novel?"

Dickens's endeavour to give most of his characters individual speaking patterns - and he is often extremely good at it, getting better and better in the course of his career - is probably due to the fact that those novels were serialized in monthly instalments and that those patterns made the characters memorable to the reading public. There were considerable time spans between individual numbers, the dramatis personae was usually very extensive so that a lot of characters had to be remembered, and not everyone could read on their own but had the instalments read out to them, and those might have been reasons why Dickens decided to make his characters differ from each other by particular speech habits. Besides, it's also more realistic.

However, some of these idiosyncrasies could also become annoying. I did not particularly enjoy Mr. Browdie's dialect but what I really hated and still hate is Mr. Mantalini's demd demnition way of speaking.

Dickens's endeavour to give most of his characters individual speaking patterns - and he is often extremely good at it, getting better and better in the course of his career - is probably due to the fact that those novels were serialized in monthly instalments and that those patterns made the characters memorable to the reading public. There were considerable time spans between individual numbers, the dramatis personae was usually very extensive so that a lot of characters had to be remembered, and not everyone could read on their own but had the instalments read out to them, and those might have been reasons why Dickens decided to make his characters differ from each other by particular speech habits. Besides, it's also more realistic.

However, some of these idiosyncrasies could also become annoying. I did not particularly enjoy Mr. Browdie's dialect but what I really hated and still hate is Mr. Mantalini's demd demnition way of speaking.

Tristram wrote: "If I were sarcastic, I'd say that Dickens wanted to fill some pages,

I'm glad you're not.

I'm glad you're not.

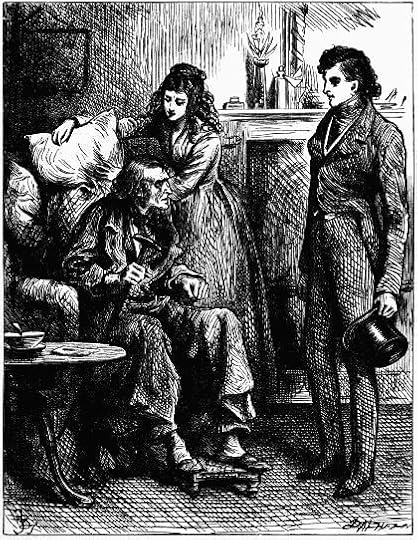

Nicholas Makes His First Visit to Mr. Bray

Chapter 46

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It is not to be supposed that he took in everything at one glance, for he had as yet been unconscious of the presence of a sick man propped up with pillows in an easy-chair, who, moving restlessly and impatiently in his seat, attracted his attention.

He was scarce fifty, perhaps, but so emaciated as to appear much older. His features presented the remains of a handsome countenance, but one in which the embers of strong and impetuous passions were easier to be traced than any expression which would have rendered a far plainer face much more prepossessing. His looks were very haggard, and his limbs and body literally worn to the bone, but there was something of the old fire in the large sunken eye notwithstanding, and it seemed to kindle afresh as he struck a thick stick, with which he seemed to have supported himself in his seat, impatiently on the floor twice or thrice, and called his daughter by her name.

‘Madeline, who is this? What does anybody want here? Who told a stranger we could be seen? What is it?’

‘I believe—’ the young lady began, as she inclined her head with an air of some confusion, in reply to the salutation of Nicholas.

‘You always believe,’ returned her father, petulantly. ‘What is it?’

By this time Nicholas had recovered sufficient presence of mind to speak for himself, so he said (as it had been agreed he should say) that he had called about a pair of hand-screens, and some painted velvet for an ottoman, both of which were required to be of the most elegant design possible, neither time nor expense being of the smallest consideration. He had also to pay for the two drawings, with many thanks, and, advancing to the little table, he laid upon it a bank note, folded in an envelope and sealed.

‘See that the money is right, Madeline,’ said the father. ‘Open the paper, my dear.’

‘It’s quite right, papa, I’m sure.’

‘Here!’ said Mr. Bray, putting out his hand, and opening and shutting his bony fingers with irritable impatience. ‘Let me see. What are you talking about, Madeline? You’re sure? How can you be sure of any such thing? Five pounds—well, is that right?’

‘Quite,’ said Madeline, bending over him. She was so busily employed in arranging the pillows that Nicholas could not see her face, but as she stooped he thought he saw a tear fall.

Commentary:

After the two large-group scenes for May, Phiz elects to produce compositions that focus on the relationships between three characters in each of the June (Part 15) etchings. Here, Nicholas, acting as the agent for the Cheerybles (who have bought drawings from her in order to support her), visits Madeline Bray and her invalid father, who is within the "Rules" of the King's Bench Prison, St. George's Fields, for a debt incurred to Ralph Nickleby. As he enters the room, Nicholas is surprised to see that the object of his employers' financial assistance is none other than the beautiful young lady who attracted his attention earlier. Her artistic creations have funded Bray's renting of the apartment and the purchase of such elegant furnishings as the harp (shown right) and a piano (presumably too large an object to be worked conveniently into the picture). Phiz has used cross-hatching to suggest the dimness of the interior, but has otherwise not suggested the dilapidated nature of Bray's residence. As in the letterpress, as Nicholas enters the upstairs front room, Madeline is seated at a table by the window (not shown, but a source of light, left) drawing, while her father, scarcely fifty yet emaciated, sits propped up by pillows in an easy chair. The scene realized, therefore encompasses almost a whole page in this forty-sixth chapter, "Throws some Light upon Nicholas's Love; but whether for Good or Evil the Reader must determine" (Part 15, June 1839).

"No matter! Do you think you bring your paltry money here as a favour or a gift"

Chapter 46

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘See that the money is right, Madeline,’ said the father. ‘Open the paper, my dear.’

‘It’s quite right, papa, I’m sure.’

‘Here!’ said Mr. Bray, putting out his hand, and opening and shutting his bony fingers with irritable impatience. ‘Let me see. What are you talking about, Madeline? You’re sure? How can you be sure of any such thing? Five pounds—well, is that right?’

‘Quite,’ said Madeline, bending over him. She was so busily employed in arranging the pillows that Nicholas could not see her face, but as she stooped he thought he saw a tear fall.

‘Ring the bell, ring the bell,’ said the sick man, with the same nervous eagerness, and motioning towards it with such a quivering hand that the bank note rustled in the air. ‘Tell her to get it changed, to get me a newspaper, to buy me some grapes, another bottle of the wine that I had last week—and—and—I forget half I want just now, but she can go out again. Let her get those first, those first. Now, Madeline, my love, quick, quick! Good God, how slow you are!’

‘He remembers nothing that she wants!’ thought Nicholas. Perhaps something of what he thought was expressed in his countenance, for the sick man, turning towards him with great asperity, demanded to know if he waited for a receipt.

‘It is no matter at all,’ said Nicholas.

‘No matter! what do you mean, sir?’ was the tart rejoinder. ‘No matter! Do you think you bring your paltry money here as a favour or a gift; or as a matter of business, and in return for value received? D—n you, sir, because you can’t appreciate the time and taste which are bestowed upon the goods you deal in, do you think you give your money away? Do you know that you are talking to a gentleman, sir, who at one time could have bought up fifty such men as you and all you have? What do you mean?’

‘I merely mean that as I shall have many dealings with this lady, if she will kindly allow me, I will not trouble her with such forms,’ said Nicholas.

‘Then I mean, if you please, that we’ll have as many forms as we can, returned the father. ‘My daughter, sir, requires no kindness from you or anybody else. Have the goodness to confine your dealings strictly to trade and business, and not to travel beyond it. Every petty tradesman is to begin to pity her now, is he? Upon my soul! Very pretty. Madeline, my dear, give him a receipt; and mind you always do so.’

While she was feigning to write it, and Nicholas was ruminating upon the extraordinary but by no means uncommon character thus presented to his observation, the invalid, who appeared at times to suffer great bodily pain, sank back in his chair and moaned out a feeble complaint that the girl had been gone an hour, and that everybody conspired to goad him.

‘When,’ said Nicholas, as he took the piece of paper, ‘when shall I call again?’

This was addressed to the daughter, but the father answered immediately.

‘When you’re requested to call, sir, and not before. Don’t worry and persecute. Madeline, my dear, when is this person to call again?’

‘Oh, not for a long time, not for three or four weeks; it is not necessary, indeed; I can do without,’ said the young lady, with great eagerness.

‘Why, how are we to do without?’ urged her father, not speaking above his breath. ‘Three or four weeks, Madeline! Three or four weeks!’

‘Then sooner, sooner, if you please,’ said the young lady, turning to Nicholas.

‘Three or four weeks!’ muttered the father. ‘Madeline, what on earth—do nothing for three or four weeks!’

‘It is a long time, ma’am,’ said Nicholas.

‘You think so, do you?’ retorted the father, angrily. ‘If I chose to beg, sir, and stoop to ask assistance from people I despise, three or four months would not be a long time; three or four years would not be a long time. Understand, sir, that is if I chose to be dependent; but as I don’t, you may call in a week.’

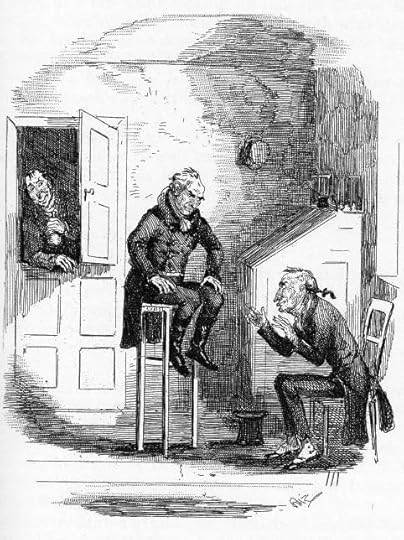

The Consultation [between Arthur Gride and Ralph Nickleby]

Chapter 47

Phiz

Dickens and Phiz begin to utilize Newman Noggs as more than a mere accessory to Ralph Nickleby, placing him in the position of an eavesdropper on the conspiratorial conversation between the covetous, grasping, aged moneylender, Arthur Gride, and the scheming Ralph Nickleby in this forty-seventh chapter, "Mr. Ralph Nickleby has some confidential Intercourse with another old Friend. They concert between them a Project, which promises well for both" (Part 15, June 1839). The plot the two are concocting involves Gride's intention to marry the beautiful Madeline Bray, not out of lust but greed, for if she marries her husband will come into a substantial property (twelve-thousand pounds). Nickleby agrees to apply pressure to her father by offering to wipe out Bray's debt if he consents to the unequal marriage. Phiz suggests the seventy-five-year-old Gride's malignant disposition by his misshapen, over sized head. The particulars of his dress, however, Phiz neglects since Dickens has provided a detailed description of these:

He wore a grey coat, with a very narrow collar, an old-fashioned waistcoat of ribbed black silk, and such scanty trousers as displayed his shrunken spindle-shanks in their full ugliness. The only articles of display or ornament in his dress, were a steel watch-chain to which were attached some large gold seals; and a black ribbon into which, in compliance with an old fashion scarcely ever observed in these days, his grey hair was gathered behind. His nose and chin were sharp and prominent, his jaws had fallen inwards from loss of teeth, his face was shrivelled and yellow, save where the cheeks were streaked with the colour of a dry winter apple; where his beard had been, there lingered yet a few grey tufts which seemed, like the ragged eyebrows, to denote the badness of the soil from which they sprung. The whole air and attitude of the form was one of stealthy cat-like obsequiousness; the whole expression of the face was concentrated in a wrinkled leer, compounded of cunning, lecherousness, slyness, and avarice.

Such was old Arthur Gride, in whose face there was not a wrinkle, in whose dress there was not one spare fold or plait, but expressed the most covetous and griping penury, and sufficiently indicated his belonging to that class of which Ralph Nickleby was a member. Such was old Arthur Gride, as he sat in a low chair looking up into the face of Ralph Nickleby, who, lounging on the tall office stool, with his arms upon his knees, looked down into his; a match for him, on whatever errand he had come.

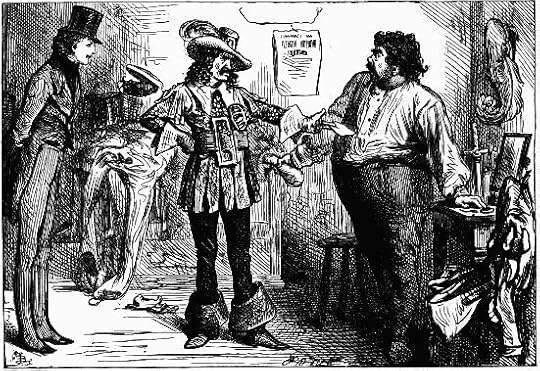

Was presently conducted by a robber, with a very large belt and buckle round his waist

Chapter 48

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

In this pensive, wayward, and uncertain state, people are apt to lounge and loiter without knowing why, to read placards on the walls with great attention and without the smallest idea of one word of their contents, and to stare most earnestly through shop-windows at things which they don’t see. It was thus that Nicholas found himself poring with the utmost interest over a large play-bill hanging outside a Minor Theatre which he had to pass on his way home, and reading a list of the actors and actresses who had promised to do honour to some approaching benefit, with as much gravity as if it had been a catalogue of the names of those ladies and gentlemen who stood highest upon the Book of Fate, and he had been looking anxiously for his own. He glanced at the top of the bill, with a smile at his own dulness, as he prepared to resume his walk, and there saw announced, in large letters with a large space between each of them, ‘Positively the last appearance of Mr. Vincent Crummles of Provincial Celebrity!!!’

‘Nonsense!’ said Nicholas, turning back again. ‘It can’t be.’

But there it was. In one line by itself was an announcement of the first night of a new melodrama; in another line by itself was an announcement of the last six nights of an old one; a third line was devoted to the re-engagement of the unrivalled African Knife-swallower, who had kindly suffered himself to be prevailed upon to forego his country engagements for one week longer; a fourth line announced that Mr. Snittle Timberry, having recovered from his late severe indisposition, would have the honour of appearing that evening; a fifth line said that there were ‘Cheers, Tears, and Laughter!’ every night; a sixth, that that was positively the last appearance of Mr. Vincent Crummles of Provincial Celebrity.

‘Surely it must be the same man,’ thought Nicholas. ‘There can’t be two Vincent Crummleses.’

The better to settle this question he referred to the bill again, and finding that there was a Baron in the first piece, and that Roberto (his son) was enacted by one Master Crummles, and Spaletro (his nephew) by one Master Percy Crummles—their last appearances—and that, incidental to the piece, was a characteristic dance by the characters, and a castanet pas seul by the Infant Phenomenon—her last appearance—he no longer entertained any doubt; and presenting himself at the stage-door, and sending in a scrap of paper with ‘Mr. Johnson’ written thereon in pencil, was presently conducted by a Robber, with a very large belt and buckle round his waist, and very large leather gauntlets on his hands, into the presence of his former manager.

Mr. Crummles was unfeignedly glad to see him, and starting up from before a small dressing-glass, with one very bushy eyebrow stuck on crooked over his left eye, and the fellow eyebrow and the calf of one of his legs in his hand, embraced him cordially; at the same time observing, that it would do Mrs. Crummles’s heart good to bid him goodbye before they went.

‘You were always a favourite of hers, Johnson,’ said Crummles, ‘always were from the first. I was quite easy in my mind about you from that first day you dined with us. One that Mrs. Crummles took a fancy to, was sure to turn out right. Ah! Johnson, what a woman that is!’

Mysterious Appearance of the Gentleman in Small-Clothes

Chapter 49

Phiz

Commentary:

Although the oral tale may well be much older, the tale of the three little pigs it first appeared in print in 1849, in James Orchard Halliwell's Nursery Rhymes and Nursery Tales. Consequently, Dickens and Phiz are not necessarily alluding to the children's story of the braggadocio wolf caught in the chimney in this forty-ninth chapter, "Chronicles the further proceedings of the Nickleby family, and the sequel of the adventure of the gentleman in the small-clothes" (Part 16, July 1839). The subplot involving Mrs. Nickleby's demented suitor offers suitable comic counterpoint to the more serious, "business" aspect of marriage (Ralph Nickleby's plotting with Arthur Gride against the Brays to acquire Madeline's inheritance). The identification of a uni-dimensional character by some detail of costume, facial distinction, or habitual phrase had been a standard "short-hand" method of characterization for Dickens ever since The Pickwick Papers. A secondary comedic feature is Mrs. Nickleby's chagrin that her "suitor" seems to have shifted his attention to Miss Le Creevy. The figures in the illustration, set in the Nicklebys' cottage, are Mrs. Nickleby (left); Kate Nickleby and Frank Cheeryble, nephew of the merchant brothers; their clerk, Tim Linkwater (centre), holding thetongs as he pinches the stranger's ankles to ascertain that they are real and not the appendages of a dummy; and the lower extremities of the lunatic neighbour (in the fireplace, the disembodied head having appeared already in plate 26):

Advancing to the door of the mysterious apartment, they were not a little surprised to hear a human voice, chaunting with a highly elaborated expression of melancholy, and in tones of suffocation which a human voice might have produced from under five or six feather-beds of the best quality, the once popular air of '"Has she then failed in her truth, the beautiful maid I adore!" Nor, on bursting into the room without demanding a parley, was their astonishment lessened by the discovery that these romantic sounds certainly proceeded from the throat of some.man up the chimney, of whom nothing was visible but pair of legs, which were dangling above the grate; apparently feeling, with extreme anxiety, for the top bar whereon to effect a landing.

A sight so unusual and unbusiness-like as this, paralysed Tim Linkinwater, who after one or two gentle pinches at the stranger's ankles, which were productive of no effect, stood clapping the tongs together, as if he were sharpening them for another assault, and did nothing else.

"This must be some drunken fellow," said Frank. "No thief would announce his presence thus."

As he said this, with great indignation, he raised the candle to obtain a better view of the legs, and was darting forward to pull them down with very little ceremony, when Mrs. Nickleby, clasping her hands, uttered a sharp sound, something between a scream and an exclamation, and demanded to know whether the mysterious limbs were not clad in small clothes and worsted stockings, or whether her eyes had deceived her?

"Yes," cried Frank, looking a little closer. "Small-clothes certainly, and — and — rough grey stockings, too. Do you him, ma'am?"

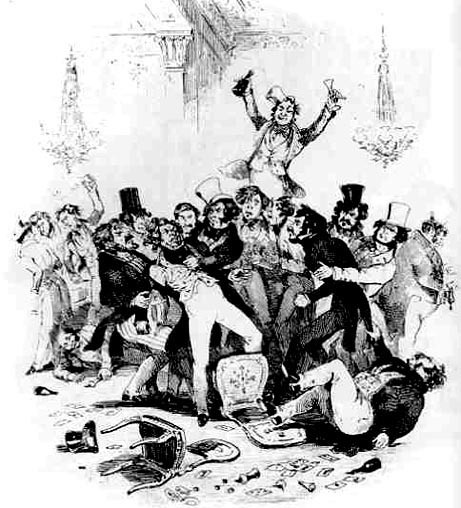

The Last Brawl between Sir Mulberry and His Pupil

Chapter 50

Phiz