Essays discussion

The Bible as literature

>

Some resources

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Thanks, I didn’t know that! Can you click the image and see if you can get the original (as opposed to the thumbnail)?

Thanks for letting me know, I was going to try other image hosts.

The one I’m using takes a while to load the full resolution image, but it works better with Goodreads. I used to use imgur but I couldn’t get the html link to work on GR.

Or maybe I should screenshot with my ipad instead of my iphone...

The one I’m using takes a while to load the full resolution image, but it works better with Goodreads. I used to use imgur but I couldn’t get the html link to work on GR.

Or maybe I should screenshot with my ipad instead of my iphone...

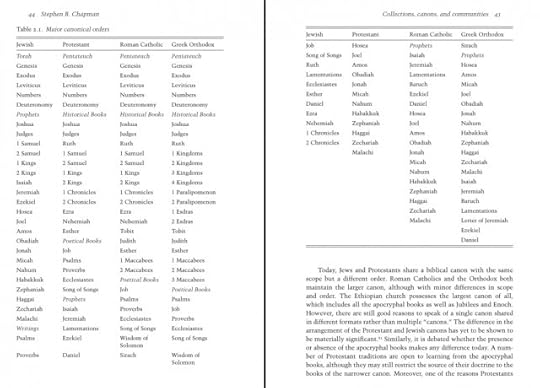

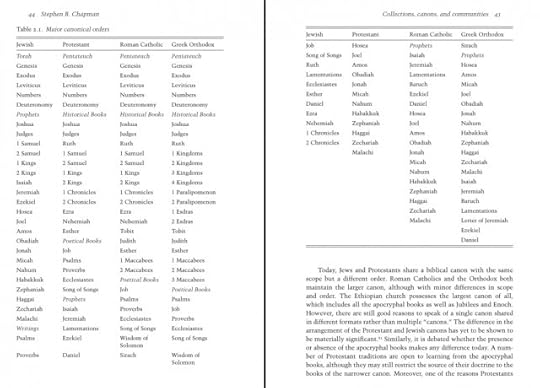

Major canonical orders (Jewish vs Protestant vs Roman Catholic vs Greek Orthodox)

source: The Cambridge Companion to the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament

source: The Cambridge Companion to the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament

YW Bryan, thanks for organizing this.

I a few secondary texts here, but they mean nothing to me, the knowledge base is so huge, I’m counting on you make it make sense!

I a few secondary texts here, but they mean nothing to me, the knowledge base is so huge, I’m counting on you make it make sense!

Lia wrote: "I’m counting on you make it make sense!"

Lia wrote: "I’m counting on you make it make sense!"Considering people spend their lifetimes studying this, I don't know that I would promise much more than some exposure. I'm just glad we'll have Ian along though--I respect his opinion on what secondary texts are worthwhile. I don't know how much side matter I'm going to explore as we move forward--really I'm just excited about actually reading through the books from start to finish. That always seemed like such a daunting task.

Lia wrote: "a few secondary texts here, but they mean nothing to me, the knowledge base is so huge, I’m counting on you make it make sense!"

Lia wrote: "a few secondary texts here, but they mean nothing to me, the knowledge base is so huge, I’m counting on you make it make sense!"If you are starting from nowhere, a good study Bible -- by which I mean one which isn't imposing a monolithic religious doctrine on a whole bunch of diverse texts, from different times, and in different genres -- is often helpful in resolving some immediate problems with the text, like the assumed background in ancient laws or customs, or who the strangely-named kings are.

And you don't have to go somewhere else (like a commentary to the specific book, or a Bible Dictionary) to look it up -- unless it is to the back of the same volume, where things like maps and extended essays tend to be tucked away). Sometimes they point out literary devices, like foreshadowing, although this is not as common as one might wish.

In an earlier thread, I mentioned The Jewish Study Bible -- the first edition, shown in the link, is fine, but the second edition has been out for several years now, and in my opinion is even better. It is attentive to the meanings of texts in Jewish tradition, but it also represents modern secular scholarship, especially regarding Ancient Near Eastern material. It is, of course, limited to the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament.

From a pretty resolutely secular or ecumenical position (at least for the most part) volume based on the New Revised Standard Version translation, see The HarperCollins Study Bible: Fully Revised & Updated

I also mentioned earlier The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version, which, if you choose the right edition, includes the Apocrypha as well as the New Testament.

There are also Study Bibles / Annotated Bibles (so named) for the Revised Standard Version, which may be available used, also with and without the Apocrypha. A lot of people prefer this older translation, although it was considered rather daring if not subversive, when it first appeared (e.g., Hebrew "young woman" for the specified "virgin" in a passage of Isaiah often used as a Christian proof-text).

I'll mention the NET Bible, Full Notes edition NET Bible, which for some reason is no longer available as a Kindle Book from Amazon -- maybe it will be restored with the recent Second Edition, although one website for the translation says that there is a problem with file size. It is pretty much overkill, with 60,000 some footnotes -- a lot of them just giving the literal translation of a Hebrew or Greek passage, where the main text has obscured it, mostly for vague "stylistic reasons." There are digital editions for platforms other than Kindle, although I have found that the interactive part of old Kindle edition was a lot better than any of the others I've tried.

Some of these "Translator's Notes" are useful, and the "Text Critical" notes are usually good, if not as frequent as one might wish. The "Study Notes" include some doctrine, and sometimes veer into the fundamentalist zone as they try to explain away oddities in the text in front of them.

There are tons of stand-alone introductions, some of them much better than others, some covering the whole Christian Canon, or the Protestant version of it, some not. And some of them make deadly dull reading.

For the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, my current favorite is How to Read the Jewish Bible by Marc Zvi Brettler, one of the editors of The Jewish Study Bible.

It is very good on genre differences and expectations, parallels in ancient texts, etc.

I don't know of a similar stand-alone introduction to the New Testament: by the time we get to it, I expect that someone will have indicated some.

I could also provide a couple of responsible websites, if anyone is interested: also a couple of Bible Dictionaries,

I forgot to mention that the Oxford Annotated Bible, to the Revised Standard Edition, Old and New Testaments (no Apocrypha) of 1962 is available from the Internet Archive as a (very fat) pdf: https://archive.org/details/OldTestam...

I forgot to mention that the Oxford Annotated Bible, to the Revised Standard Edition, Old and New Testaments (no Apocrypha) of 1962 is available from the Internet Archive as a (very fat) pdf: https://archive.org/details/OldTestam...In fact, it you can get it as plain pdf, or a machine-readable text copy, which should be useful in finding things in the pdf format.

This edition is getting a bit antiquated where historical and cultural backgrounds are concerned (and I think some of the notes are not just debatable, but plain wrong), but it is mostly a creditable part of the series of annotated and study bibles from Oxford (which includes the Jewish Study Bible, by the way), and it is free. If you can put up with navigating the pdf, it would be a useful addition to a digital library.

Thanks Ian. I think Ashley also recommended the Oxford Annotated Bible, I borrowed the “New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha”, but it’s nice to have the old free pdf so I can directly jot notes on it on my tablet with a stylus.

Right now, my main problem is that I’ve signed out too many biblical commentaries from the academic library with not enough time to read (or even explore) them;, and even the TOC is intimidatingly full of words that don’t seem pronounceable.

On top of The New Oxford Annotated Bible with Apocrypha: New Revised Standard Version, I also got The Blackwell Companion to the Bible in English Literature, and Critical Companion to the Bible (Critical Companion, and The Cambridge Companion to the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, and Dialogues of the Word: The Bible as Literature According to Bakhtin.

I think I like the Cambridge/ Blackwell companions because I’m familiar with them, it feels like I’m just approaching another literary or philosophical topic, as opposed to some real world practice that is esoteric and beyond words (ha! What else is there but words, words, and more words??)

I think I’m probably going to stick with the New Oxford Annotated Bible to start with, and flip through the other ones for charts and tables and maps and index references when I have more specific problems or questions.

Man, I thought there were too many secondary literatures published on James Joyce. Poor, naive me. I didn’t check the biblical section.

Right now, my main problem is that I’ve signed out too many biblical commentaries from the academic library with not enough time to read (or even explore) them;, and even the TOC is intimidatingly full of words that don’t seem pronounceable.

On top of The New Oxford Annotated Bible with Apocrypha: New Revised Standard Version, I also got The Blackwell Companion to the Bible in English Literature, and Critical Companion to the Bible (Critical Companion, and The Cambridge Companion to the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, and Dialogues of the Word: The Bible as Literature According to Bakhtin.

I think I like the Cambridge/ Blackwell companions because I’m familiar with them, it feels like I’m just approaching another literary or philosophical topic, as opposed to some real world practice that is esoteric and beyond words (ha! What else is there but words, words, and more words??)

I think I’m probably going to stick with the New Oxford Annotated Bible to start with, and flip through the other ones for charts and tables and maps and index references when I have more specific problems or questions.

Man, I thought there were too many secondary literatures published on James Joyce. Poor, naive me. I didn’t check the biblical section.

Also, I saw many books by Bart D. Ehrman on the shelves, I was tempted to get them because I’ve heard people debate them not infrequently. The obvious problem is that he’s clearly controversial — as in much criticized by academic Biblical scholars. So I’m curious if you have any opinion on Ehrman and whether his books are worth reading.

Lia wrote: "Also, I saw many books by Bart D. Ehrman on the shelves, I was tempted to get them because I’ve heard people debate them not infrequently. The obvious problem is that he’s clearly controversial — a..."

Lia wrote: "Also, I saw many books by Bart D. Ehrman on the shelves, I was tempted to get them because I’ve heard people debate them not infrequently. The obvious problem is that he’s clearly controversial — a..."Ehrman is a New Testament specialist, so you might want to postpone reading him for a while (or plunge right in). And yes, he is controversial: he seems to have set out to be. Either that, or he believes he knows things about the original Greek text that he has demonstrated already cannot be securely known.....

The background is that the New Testament text is a mess when looked at in detail. Many manuscripts, especially the earliest known, contain odd spellings and irregular grammar, and dramatic inconsistencies between one manuscript and another at some few points. The problem is magnified by the sheer number of manuscript copies, each with its own particular differences (as is usual with any text copied by hand many, many times, over hundreds of years).

However, scholars since the later nineteenth century have been producing New Testament editions superior to anything that had gone before them, and there is a great deal of agreement on most of the text -- with a few embarrassing exceptions, like the ending of Mark, and where the story of the Woman Taken in Adultery actually goes.

For a taste of the kind of minutiae involved, you might try the blog Evangelical Textual Criticism: http://evangelicaltextualcriticism.bl...

At the opposite pole from Ehrman are the people from whom he emerged, and against whom he is probably reacting: those who hold that there was once a perfect, divinely inspired, manuscript of the New Testament books, which can be, if not recovered, at least approximated -- to a level of exactitude professional textual critics find highly improbable. (And never mind that if St. Paul sent out multiple copies of some of his letters -- which he did -- each one of them would probably have had differences from all the others, just due to human fallibility.)

Some "King James Version ONLY" enthusiasts in that camp think that we already have a close replication of the inspired original, the Textus Receptus, followed by the King James translators. Of course, the committee the King put together for the project was charged with revising older translations, which had used different, non-identical, printed New Testaments, so their accuracy in such terms would have been literally miraculous in itself.

The Textus Receptus, which emerged from competing editions in the Reformation period, and prevailed in Western Europe for a few centuries, was generally based, not on the oldest available copies (which had fewer chances to pick up errors from multiple re-copyings), but on a larger number of copies that agreed most closely with each other, had consistent spellings, and clear grammar. And they were all fairly recent, suggesting that they all derived from a single "corrected" copy used in the Byzantine Empire, and not on an unbroken transmission of the "correct text" from antiquity. So that this "Majority Text" is that by historical accident.

The Hebrew Text has its own set of problems, which I won't go into right now -- or maybe ever.

I thought the Greek Text was more problematic than the Hebrew one, if for no other reason than additional translations.

I thought the Greek Text was more problematic than the Hebrew one, if for no other reason than additional translations.It's been years since I last read Ehrman. I have two of his books. He was a great source to me on original Christian sects, of which there were many, each believing something different from the others. The culling and merging took a while. He is my only source on Gnostic teachings and manuscripts. Not good to have only one. I have never read Elaine Pagels, and I need to.

I do think the early Christian sects are a fascinating study.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I thought the Greek Text was more problematic than the Hebrew one, if for no other reason than additional translations. ..."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I thought the Greek Text was more problematic than the Hebrew one, if for no other reason than additional translations. ..."The problem with the Hebrew Text -- the traditional Jewish Masoretic Text, which nearly everyone follows in printed editions -- is that it is suspiciously uniform.

The parent of this text-form was apparently finalized very early, and, tradition claims, entrusted to specialists who took every care to see that the consonants-only text was preserved with great exactitude, including irregular spellings, odd grammar, and sentences that just don't make any sense.

We now know that this is indeed a very ancient text type, found in the Dead Sea Scrolls and some other, contemporary, finds. (And not something cooked up by the wicked Jews in the Middle Ages, as some Christians have liked to assert.)

The vowel markings which accompany the medieval manuscripts are another, complicated matter -- they were notated from an oral tradition of how the text should be read aloud, and proving antiquity for their evidence is difficult. (Although not quite hopeless.)

Unfortunately, this means that making sense of difficult passages relies on conjecture more often than is readily admitted. And some of the emendations are so obvious that it must be suspected that early translators made the corrections for themselves, and didn't have a better text in front of them.

The early Greek translation, the Septuagint, was indeed based on a somewhat different Hebrew original, now attested in the Dead Sea Scrolls, but has its own complex history (including attempts to make it conform with the standard Hebrew edition) to confuse things. And there are a bunch of other relevant translations, like the Old Latin, via the Septuagint; St. Jerome's Vulgate, directly from the Hebrew; the Syriac Peshitta, which is related somehow to the Septuagint, but may include material from an older Jewish translation directly from the Hebrew; and a couple of others which get cited from time to time, often for the light they shed on the Greek version.

For the Five Books of Moses, there is also the Samaritan Pentateuch, modified from a text-type also found in the Dead Sea Scrolls, testifying that it too, as long suspected, is very old, and its readings are sometimes harmonistic (i.e., reconcile, or explain away, inconsistencies, make parallel passages precisely parallel, etc.).

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I have never read Elaine Pagels, and I need to.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I have never read Elaine Pagels, and I need to.I do think the early Christian sects are a fascinating study. ..."

I've been following this, off and on, since around 1975.

Elaine Pagels' "The Gnostic Gospels" (1979) has dated a bit, but is still an engaging introduction to the subject. It brought to popular attention the Nag Hammadi cache of Gnostic (or Gnostic-like) writings in Coptic, discovered in Egypt in the late 1940s, which languished for years without publication (like the Dead Sea Scrolls, although for somewhat different reasons). Except for a few excerpts in the Church Fathers, and some other Coptic works discovered in the nineteenth-century, this was the first time the Gnostics were able to speak for themselves.

In the view of most specialists, "The Gnostic Gospels" is also better than Pagels' other major early book, "The Gnostic Paul" (1975). The Wikipedia article on her is worth reading.

Much more dated, but fundamental to most discussions of the subject, even if by way of reaction, is Hans Jonas' The Gnostic Religion: The Message of the Alien God and the Beginnings of Christianity (originally 1958). This is based on material available before the Second World War, mainly Greek and Latin, and sets up a lot of the basic categories still being used in discussions of the subject.

It was an extension of the author's magnum opus of the 1930s Gnosis und spätantiker Geist (1–2, 1934–1954). At the time, his "Gnosis..." was somewhat revolutionary in taking the Gnostic teachings as reflections of a world-view, with philosophical implications, instead of just a weird religion with an origin, or origins, waiting to be detected by scholars. Jewish, Christian, Egyptian, Greco-Roman, and Iranian were the major contenders -- or pigeon-holes. (And, although I don't think Jonas mentions it, the English independent scholar G.R.S. Mead, in the late nineteenth century, offered Buddhism, as it was supposedly misunderstood in the Hellenistic and Roman world.)

"The Gnostic Religion" is now in its third, and (given the author's death in 1993), its final, edition: Nag Hammadi material began to be used in the second edition, which also included an originally separate piece comparing Gnosticism and Existentialism.

There is a selection from the whole body of original documentation in The Gnostic Bible by Bentley Layton, now in an expanded edition with the "Gospel of Judas."

https://www.amazon.com/Gnostic-Bible-...

However, the biggest single source in readable English, with useful introductions to each text, is The Nag Hammadi Scriptures, a successor to some earlier compilations. This is available in Kindle format (which of course is easily searchable, and can be highlighted and annotated at will), as well as a hefty (864 pages, 1.8 pounds) paperback.

Also quite readable, but again dated by full publication and discussion of the Nag Hammadi corpus, is Gnosis: The Nature and History of Gnosticism, by Kurt Rudolph. It surveys the doctrines of major Gnostic (or para-Gnostic) movements, and has some interesting illustrations.

I would also suggest a look at April D. DeConick's Forbidden Gospels Blog, http://aprildeconick.com/ This covers current thinking and controversies in the field of Gnostic Studies (and some other topics). There is a sidebar categorizing postings in the blog, so following the discussion is fairly easy.

DeConick was one of the first to point out that the official publication of the "Gospel of Judas" had completely misunderstood the thrust of the work, due to poor translation, and perhaps excessive eagerness to find something controversial and exciting. One can follow her thoughts on this at http://aprildeconick.com/forbiddengos...

There is a current controversy over whether "Gnostic" is actually a valid, or at least useful, category, or is a confused creation of modern scholarship, based on the dubious authority of the Church Fathers, which doesn't correspond to anything in particular. And would invalidate syntheses like those of Jonas and Rudolph.

This has produced some interesting discussions by qualified scholars.

I'm far from being one of them, but I'm provisionally willing to accept the view of two contemporaries of the "Gnostic" writings, the Neo-Platonic philosopher Plotinus (d. 270), and his disciple Porphyry (d. circa 305) that there were views that could be lumped together as Gnostic, and groups that could be labelled Gnostics, and that he was against them. (Of course, Plotinus doesn't seem to have gone out of his way to distinguish them from "orthodox" Christians.)

I have no idea what you guys are talking about.

I just want to mention I started on the Genesis (the red Oxford one) with all the supplementary readings, backgrounds, historicity, sources etc — and I’m surprised they don’t definitively say that Moses never existed, and that the book can’t be historically accurate (because I’ve read that in an academic journal years ago, on conflict-resolution in Israel, I think.)

This is my “oh my god, maybe my teacher [prof] was wrong” moment.

I just want to mention I started on the Genesis (the red Oxford one) with all the supplementary readings, backgrounds, historicity, sources etc — and I’m surprised they don’t definitively say that Moses never existed, and that the book can’t be historically accurate (because I’ve read that in an academic journal years ago, on conflict-resolution in Israel, I think.)

This is my “oh my god, maybe my teacher [prof] was wrong” moment.

Lia wrote: "I have no idea what you guys are talking about. ..."

Lia wrote: "I have no idea what you guys are talking about. ..."The Gnostics were contemporaries of early Christianity, and in some cases, at least, self-styled "true Christians," who viewed the material world as the product of a wicked, or at best incompetent, demiurge (like Plato's creator, only confused), identified him with the Biblical God, and taught salvation from him by way of the secret knowledge of the unknown supreme God, who can't be blamed for the mess we are in. (Except that in some cases this purely spiritual god does seem to have had a plan that involved the present, fallen, cosmos.)

Some Gnostic groups specifically identified Christ (but not always Jesus per se) with the latest revealer of true, saving, knowledge (their gnosis), but others did without, preferring other messengers from the higher orders of reality.

They have been somewhat romanticized in recent times, and held up as more tolerant, and more open to women, than what became Orthodox Christianity. In point of fact, they had their own heresy-fighters who opposed other Gnostics, and in general their opinion of women was pretty low.

Lia wrote: "I’m surprised they don’t definitively say that Moses never existed, and that the book can’t be historically accurate..."

Lia wrote: "I’m surprised they don’t definitively say that Moses never existed, and that the book can’t be historically accurate..."Some study / annotated Bibles do seem to dance around the subject, apparently trying to avoid open controversy with those who cling to the idea of Mosaic authorship, and literal truth, even though they mention problems with that idea.

In the present case, a long paragraph on p. 4 (in the "Introduction to the Pentateuch") points out that Mosaic authorship is never actually mentioned in the text, but is a later doctrine, and that the text contains anachronisms if one maintains that position. But it leaves it up to the reader to draw the necessary conclusion.

It then goes directly into the Documentary Hypothesis, which postulates several writings, of various dates, that were woven together to form the present text, which pretty much rules out specifically Mosaic authorship.

But you're right that they don't come right out and say that Mosaic authorship is possible *only* if you postulate a supernatural origin, which can explain away just about anything.

It is a good deal less explicit than the HarperCollins Study Bible, which in its introduction to Genesis says flatly:

"the book was primarily composed and compiled during the centuries of monarchical rule and immediately thereafter, roughly from the tenth through the sixth centuries BCE."

So Moses can't be the author.

(Even this post-Mosaic dating is now controversial -- again. Some critics postulate a very late, even post-Exilic, origin, for the whole thing. As has been pointed out in response, this means that great Hebrew prose was composed during a period for which we have no epigraphic evidence that Hebrew was even being written down. Not impossible, but odd.)

Proving a negative is very hard, even impossible in formal logic: I don't think that it is possible to prove that someone like Moses never existed, and, miracles aside, never did *any* of the things attributed to him. Not that there is any external evidence that he ever existed.

The late Walter Kaufmann (who did all those Nietzsche translations) liked to point out that the cross-culturally unusual portrayal of Moses as a fallible human being suggests some strong element of fact in the portrayal, even after the whole Exodus / Sinai tradition is thrown out.

Either that, or a very strong monotheistic impulse from an early date prevented the promotion of an idealized creation to quasi-divine status, for example by having him ascend to Heaven, instead of dying alone east of Jordan.

It is also a peculiar fact that the Levites, Moses' tribe, and especially the priests descended from his brother Aaron, have some Egyptian-derived names in their genealogies, which are scarce to non-existent in other lines of Israelite descent. Someone had an experience of contact with Egyptian culture, even if they weren't slaves in Egypt, and didn't pass through the Red Sea without getting their feet wet.

Thanks Ian, “dancing around the subject” is a better way of putting it. They make it sound like it’s the wrong question to ask, as opposed to stating it as well-established fact (which was the tone of the paper I read, from memory, of course.)

And I agree about the impossibility of proving a negative.

And I agree about the impossibility of proving a negative.

A while back I offered to provide information on some Bible Dictionaries: while no one has asked, I have pulled together information on those I had in mind, so I'll go ahead, and hope someone finds it useful.

A while back I offered to provide information on some Bible Dictionaries: while no one has asked, I have pulled together information on those I had in mind, so I'll go ahead, and hope someone finds it useful.First of all, there are a lot of Bible Dictionaries out there, some originating in the nineteenth-century, some of those available in updated versions. For an example of the this, see

The New Easton Bible Dictionary: Updated and Revised Edition (2016) 612 pages, 3.8 pounds

https://www.amazon.com/NEW-Easton-Bib...

(The original edition from, I think, 1897, is readily available in cheap Kindle editions.)

These are often quite informative, but a lot of their information is out-of-date, or something is missing, and they tend to be overtly religious and denominational, very concerned that you are indoctrinated in the True Faith (whichever one it is).

There are modern (and more expensive) dictionaries, which have much more current information (just counting archeological evidence alone), and are dictionaries of what is in the Bible, not of theological positions on it: except when they have articles reporting on the doctrine in question.

The most recent (that I know of) is HarperCollins Bible Dictionary: Revised and Updated in 2011 (in print, and Kindle, Kobo, and Nook). It runs to 1168 pages (Amazon's figure), and is something of a brick, at 3.1 pounds

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1...

https://www.amazon.com/HarperCollins-...

This was written and edited in cooperation with the ecumenical/secular Society of Biblical Literature, with (reportedly) about 50% new content, compared to an earlier edition. It offers traditional English pronunciation of names, sometimes with etymologies (which are more likely to be valid than nineteenth-century guesses). It offers descriptive, not prescriptive, definitions of terms with technical meanings, e.g. "grace" in Christianity.

There is also Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, 2000 (apparently out of print, but Amazon offers used copies for sale), which is even more massive than the HarperCollins competition, as it has 1480 pages, and weighs 4.4 pounds. (I should try to open it flat on a table, and not hold it in my hands while reading, but I usually forget until my wrists remind me.) See

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1...

https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/080...

This is a revision of an earlier (1987) version, but is basically a new book, with nearly 600 contributors (listed on 13 small-print pages) and about 5000 articles. It has (usually) pertinent illustrations, and a section of color maps at the end. The lead editor, David Noel Freedman, was a distinguished Old Testament scholar.

This one gives modern Hebrew pronunciations of Old Testament names, and Greek for the New Testament, not traditional English ones, which can lead to confusion for those who don't realize that there is a considerable difference.

It also has articles on theological positions (the Trinity, for example), and on specific very early Christian heretics (like Marcion, with his heavily edited Gospel), and heresies (Gnosticism), some of which are missing in the HarperCollins competition (I haven't checked systematically on this, so I can't estimate how great the difference is.)

I should point out that, while HarperCollins is a corporate entity with a line of religious books, Eerdmans is primarily a religious (Christian) Publisher, and their "Dictionary" is a bit different from the bulk of their publications.

Thanks for the reviews and recommendations, Ian.

Given the price difference— and the ergonomic factors — I’d probably opt for the digital version. (Keyword search would imaginably be extremely helpful as well.)

I have a weird question about the print ones: do they use that ultralight translucent paper, or do they use regular paper? (Curious factoid: I just found out “the term “Bible” derives from the Greek ἡ βύβλοϛ, or less correctly, ὁ βίβλοϛ, which originally denoted the inner layer of bark, and part of the papyrus stalk, from which paper was produced...Βύβλοϛ/βίβλοϛ came to connote a book, a writing, or a letter. Hence its diminuitive, τὸ βιβλίον, denoted a small book or tablet.”.)

I shall also read the Bible on my tablet :-)

Given the price difference— and the ergonomic factors — I’d probably opt for the digital version. (Keyword search would imaginably be extremely helpful as well.)

I have a weird question about the print ones: do they use that ultralight translucent paper, or do they use regular paper? (Curious factoid: I just found out “the term “Bible” derives from the Greek ἡ βύβλοϛ, or less correctly, ὁ βίβλοϛ, which originally denoted the inner layer of bark, and part of the papyrus stalk, from which paper was produced...Βύβλοϛ/βίβλοϛ came to connote a book, a writing, or a letter. Hence its diminuitive, τὸ βιβλίον, denoted a small book or tablet.”.)

I shall also read the Bible on my tablet :-)

Lia wrote: "I have a weird question about the print ones: do they use that ultralight translucent paper, or do they use regular paper?..."

Lia wrote: "I have a weird question about the print ones: do they use that ultralight translucent paper, or do they use regular paper?..."The Eerdmans Dictionary uses a thin, but opaque paper -- at least the copy I have does, this sometimes changes between print runs. "Bible paper" came into use out of the demand to squeeze everything into a physically smaller book, and paper thickness was something that can be controlled.

(I don't like it, either: I tolerate something almost as thin in the Jewish Study Bible, just because they crammed in so much information).

As for HarperCollins, I don't recall -- I haven't handled a copy in years (I got my Kindle copy fairly recently).

As for papyrus, Eerdmans has a slightly different report under the heading of BIBLE: "The term [for a book] derives from bublos or bublion, loanwords from Egyptian, denoting originally the stalk and then the inner pitch of the papyrus plant from which scrolls were commonly made." (It doesn't venture an opinion on the correct Greek.)

Under the heading BYBLOS (a Phoenician city which traded with Egypt), it alludes to the idea that the Greeks got the name of the product from where they bought it, not its ultimate source. But it seems by that account to be more likely the other way around. Byblos was actually Gebal to the people who lived there, and the Greeks may have had a reason for thus garbling the name. (Not that they ever needed much of an excuse for "fixing" barbarian names.)

Thanks for sharing those entries. I should point out mine came from source:A Handbook of Biblical Reception in Jewish, European Christian, and Islamic Folklores by Eric Ziolkowski.

I expect that the KJV will be of special interest in our discussion, as it is a key text in English literature, and at the very least was usually "The Bible" in the English speaking world from the late seventeenth-century to the late nineteenth century (with the main exception being the Douay-Rheims translation for Catholics).

I expect that the KJV will be of special interest in our discussion, as it is a key text in English literature, and at the very least was usually "The Bible" in the English speaking world from the late seventeenth-century to the late nineteenth century (with the main exception being the Douay-Rheims translation for Catholics).But I would like to point out a somewhat contrarian view: C.S. Lewis' essay on "The Literary Impact of the Authorised Version."

It was originally the Ethel M. Wood Lecture, delivered before the University of London on 20 March 1950 and was published by the Athlone Press in 1950.

This used to be available on-line, but the permission for this ran out in 2011, so I can't point to an easy (and free) source for it, although there might be "bootleg" copies still somewhere on the Web.

It was, however, included in C.S. Lewis, Selected Literary Essays, edited by Walter Hooper (1968), which is available as a Kindle book, and probably can be found in a library, or through a library system.

(It contains a lot of other interesting stuff. So far as I can tell, material from it is NOT in the C.S. Lewis Essay Collection: Literature, Philosophy and Short Stories, published in 2000.

Lewis praises the KJV's prose, but points out that the KJV was extensively based on Tudor-period translations, much of it still being identical, or nearly identical, to Tyndale's very unauthorized partial version of 1530. He skims over the subsequent translations with brief mentions. The complete Old and New Testaments were first issued by Myles Coverdale in 1535-1537, this time with a royal license, making extensive use of Tyndale. (Coverdale's Psalms remained in the Book of Common Prayer until 1979, and so had a very strong influence on Anglicans/Episcopalians). This in turn underlay the "Great Bible" of 1539, the first real "authorised edition" (it said so on the title page). That was a basis for Queen Elizabeth's "Bishops' Bible" of 1568 (itself "substantially revised" in 1572, according to Wikipedia), which was itself revised to create the King James Version.

So many early allusions, and even quotations, aren't from the 1611 King James Version at all, but from these lineal predecessors, or instead from the overtly Calvinist popular rival, the Geneva Bible (1567-1570, with several revisions): which itself drew on the Tyndale-Coverdale tradition.

So the The King James Version as such became a predominant influence or source of specific language surprisingly late (and had little impact on style as such).

For Milton ("Paradise Lost," etc.) and John Bunyan "The Pilgrim's Progress" and much else) in the late seventeenth century, to take two examples, the English Bible was still mainly the Geneva Bible.

(This statement is complicated by the fact that Milton was capable of reading -- probably -- the Greek New Testament, and certainly the Latin Vulgate, and even had a little Hebrew, so he wasn't dependent on any English translation. Bunyan, of course, knew nothing but English, but in another essay Lewis contended that his overall style, as opposed to substance, and actual quotations, owed little or nothing to any Biblical translation.)

As the Geneva Bible was also drawn on by King James' committee of revisers, however, this is sometimes a distinction without a difference: but not always.

Lewis had a good background for this conclusion: he had systematically read through the English literature of the relevant period in preparation for the massive English Literature In The Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama, part of the Oxford History of English Literature (1954: someone else did the volume on Elizabethan drama).

This was more recently reprinted as Poetry and Prose in the Sixteenth Century. (Some other volumes in the O.H.E.L., as Lewis liked to call it, have also been reprinted under new titles, rather than as part of the overall series.)

Lewis' reflections on the difficulty of untangling the generally Biblical (and sometimes Classical) from the KJV in particular are worth considering, too.

Books mentioned in this topic

C.S. Lewis Essay Collection: Literature, Philosophy and Short Stories (other topics)English Literature In The Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama (other topics)

Poetry and Prose in the Sixteenth Century (other topics)

Selected Literary Essays (other topics)

A Handbook of Biblical Reception in Jewish, European Christian, and Islamic Folklores (Handbooks of the Bible and Its Reception (other topics)

More...

Just a handy index of all the “books” in the bible, for ease of planning ...

source: Critical Companion to the Bible