Art Lovers discussion

Interior Decor, a Different Art

>

Ming Dynasty

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644)

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644)While northern traditions of Cizhou and Jun ware continued to decline, pottery production in the south expanded. It was chiefly centred on Jingdezhen, an ideal site because of the abundance of minerals used for porcelain manufacture—kaolin (china clay) and petuntse (china stone)—ample wood fuel, and good communications by water. Most of the celadon, however, was still produced in Zhejiang, notably at Longchuan and Chuzhou, whose Ming products are more heavily potted than those of the Song and Yuan and are decorated with incised and molded designs under a sea-green glaze. Celadon dishes, some of large size, were an important item in China’s trade with the Middle East, whose rulers, it was said, believed that the glaze would crack or change colour if poison touched it.

At Jingdezhen the relatively coarse-bodied shufu ware was developed into a hard white porcelain that no longer reveals the touch of the potter’s hand. The practically invisible designs sometimes carved in the translucent body are known as anhua (“secret decoration”). In the Yongle period (1402–24) the practice began of putting the reign mark on the base. This was first applied to the finest white porcelain and to monochrome ware decorated with copper red under a transparent glaze. As aforementioned, a white porcelain with ivory glaze was also made at Dehua in Fujian.

Ming dynasty Chinese history

Ming dynasty Chinese historyWritten By: The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Ming dynasty, Wade-Giles romanization Ming, Chinese dynasty that lasted from 1368 to 1644 and provided an interval of native Chinese rule between eras of Mongol and Manchu dominance, respectively. During the Ming period, China exerted immense cultural and political influence on East Asia and the Turks to the west, as well as on Vietnam and Myanmar to the south.

Ming ceramics

Standing male figures, glazed ceramic, China, Ming dynasty, 1500s; in the Indianapolis Museum of Art. 33.3 × 9.5 × 7.6 cm.

History

The Ming dynasty, which succeeded the Yuan (Mongol) dynasty (1206–1368), was founded by Zhu Yuanzhang. Zhu, who was of humble origins, later assumed the reign title of Hongwu. The Ming became one of the most stable but also one of the most autocratic of all Chinese dynasties.

The basic governmental structure established by the Ming was continued by the subsequent Qing (Manchu) dynasty and lasted until the imperial institution was abolished in 1911/12. The civil service system was perfected during the Ming and then became stratified; almost all the top Ming officials entered the bureaucracy by passing a government examination. The Censorate (Yushitai), an office designed to investigate official misconduct and corruption, was made a separate organ of the government. Affairs in each province were handled by three agencies, each reporting to separate bureaus in the central government. The position of prime minister was abolished. Instead, the emperor took over personal control of the government, ruling with the assistance of the especially appointed Neige, or Grand Secretariat.

Basically, the Ming incorporated the Song dynasty’s policy of relying on the literati in managing state affairs. However, from the Yongle emperor onward, the emperors relied increasingly on trusted eunuchs to contain the literati. Also introduced at that time was a system of punishment by flogging with a stick in court, which was designed to humiliate civil officials—while also making use of them to realize the emperor’s aim of maintaining practical control of the state in his own hands. By decree of the emperor, a vast spying service was organized under three special agencies.

Struggles with peoples of various nationalities continued throughout the Ming period. Clashes with Mongols were nearly incessant. During the first decades of the dynasty, the Mongols were driven north to Outer Mongolia (present-day Mongolia), but the Ming could not claim a decisive victory. From then onward the Ming were generally able to maintain their northern border, though by the later stages of the dynasty it in effect only reached the line of the Great Wall. On the northeast, the Juchen (Chinese: Nüzhen, or Ruzhen), who rose in the northeast around the end of the 16th century, pressed the Ming army to withdraw successively southward, and eventually the Ming made the east end of the Great Wall their last line of defense. The Ming devoted considerable resources toward maintaining and strengthening the wall, especially near Beijing, the dynasty’s capital.

Great Wall of China

Portion of the Great Wall of China built during the Ming dynasty.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming...

Cultural achievements

Cultural achievementsDespite the many foreign contacts made during the Ming period, cultural developments were characterized by a generally conservative and inward-looking attitude. Ming architecture is largely undistinguished with the Forbidden City, a palace complex built in Beijing in the 15th century by the Yongle emperor (and subsequently enlarged and rebuilt), its main representative. The best Ming sculpture is found not in large statues but in small ornamental carvings of jade, ivory, wood, and porcelain. Although a high level of workmanship is manifest in Ming decorative arts such as cloisonné, enamelware, bronze, lacquerwork, and furniture, the major achievements in art were in painting and pottery.

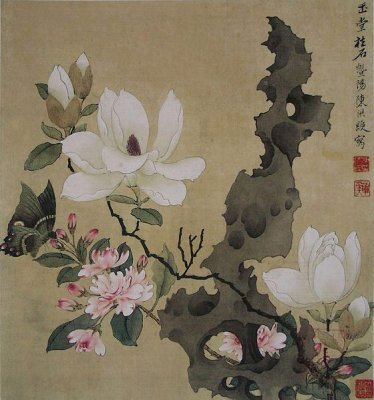

While there were two main traditions in painting in the Ming period, that of “literati painting” (wenrenhua) of the Wu school and that of the “professional academics” (huayuanpai) associated with the Zhe school, artists generally stressed independent creation, impressing their work with strong marks of their personal styles.

A Tall Pine and Daoist Immortal, ink and colour on silk hanging scroll with self-portrait (bottom centre) by Chen Hongshou, 1635, Ming dynasty; in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China

There were many new developments in ceramics, along with the continuation of established traditions. Three major types of decoration emerged: monochromatic glazes, including celadon, red, green, and yellow; underglaze copper red and cobalt blue; and overglaze, or enamel painting, sometimes combined with underglaze blue. The latter, often called “blue and white,” was imitated in Vietnam, Japan, and, from the 17th century, in Europe. Much of this porcelain was produced in the huge factory at Jingdezhen in present-day Jiangsu province. One of the period’s most-influential wares was the stoneware of Yixing in Jiangsu province, which was exported in the 17th century to the West, where it was known as boccaro ware and imitated by such factories as Meissen.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming...

Ming Dynasty Art

Ming Dynasty ArtThe Ming Dynasty continued the imperial Chinese tradition of support for artistic endeavors. A wide variety of arts flourished during the period, ranging from painting to drama and from poetry to music.

Porcelain and Lacquer

The decoration of porcelain reached a new level of sophistication with glazed designs showing scenes of immense intricacy, at times coming close to the level of detail found in paintings.

Similarly, lacquer carvings approached the height of their beauty and complexity during the Ming Dynasty. Wealthy families often displayed these items as a sign of their status and to show off their respect for the arts. Furniture, decorations, and even writing materials were chosen for their aesthetic impact.

Famous Ming Dynasty Painters

Painting styles in the Ming Dynasty were evolutionary rather than revolutionary, with clear influences being seen from the previous Yuan and Song periods. A number of China's most famous painters lived during the Ming era. Among these were Qiu Yeng, Wen Zhengming, Ni Zan, and Shen Zhou.

Their works were in such great demand that it was possible for the best artists to obtain a comfortable living simply from commissions. Existing paintings also sold for high prices to collectors. One account states that Qiu Ying received six pounds of silver as payment for the painting of a long scroll marking a wealthy man's mother's birthday.

Ceramic Arts

The main center for sculpted porcelain production during the Ming Dynasty was Jingdezhen, although Dehua was also important, especially in the export trade. By the later Ming period, Chinese exports were becoming increasingly important to the empire's economy.

White was the dominant color for artistic ceramics, although blue became widely used as the era wore on. Other colors were occasionally employed, but the blue and white combination became characteristic of Chinese porcelain design. To increase the desirability and decorative appeal of ceramic sculptures, precious substances such as ivory and jade were also widely used.

http://themingdynasty.org/ming-dynast...

By Roderick Conway Morris

Oct. 16, 2014

‘Amusements in the Xuande Emperor’s Palace,’’ which shows eunuchs playing a form of soccer, is one example of scrolls depicting life in the Chinese court. CreditCreditThe Palace Museum, Beijing

LONDON — The Ming Dynasty ruled China from 1368 to 1644, and it was under its aegis, during the first half of the 15th century, that technological and design advances brought milky white and cobalt-blue porcelain to perfection.

The most internationally sought-after of all ceramics, Ming products became synonymous with the country that produced them, referred to in India and the Middle East as “chini” and in English as “china.”

But this artistic high point was just one of the many achievements of the Ming Dynasty between 1400 and 1450, as shown by “Ming: 50 years that changed China,” in the recently opened Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery at the British Museum. The show runs from Sept. 18 until Jan. 5, 2015.

Five years in the planning, this dazzling show is curated by Professor Craig Clunas of Oxford University and Jessica Harrison-Hall of the British Museum.

With its population of around 85 million, 15th-century Ming China was by far the largest state on the globe. As Professor Clunas points out in the exhibition’s exemplary catalog, everything about it was on a grand scale: “It had a greater land area, bigger cities (and more big cities), bigger armies, bigger ships, bigger palaces, bigger bells, more literate people, more religious professionals.”

A Ming vase from the Yongle dynasty, when the porcelain reached its most refined form.CreditBritish Museum

Ming was not a family name but an appellation, meaning “bright,” “luminous” or “shining.” It was adopted by the founder of the dynasty, Zhu Yuanzhang, who had overthrown the Mongol Yuan dynasty, the previous rulers of China for almost a century. The exhibition opens with two magnificent silk hanging scrolls: the earliest known painting of Nanjing, where Zhu Yuanzhang made his capital from 1368 to 1398, and a later 15th-century image of the Forbidden City in Beijing.

The third Ming ruler, the Yongle emperor (1403-1424), made the momentous decision to move the capital to Beijing. A long-term consequence of this relocation was the adoption of the local dialect, Mandarin, as the language of imperial administration and communication. During this period, in the far south of the country, the Ming also fixed China’s southern borders, which have remained unchanged till this day.

The ambition and scope of the Yongle emperor’s construction projects and military campaigns from the far north to the far south of his domains led historians to see his reign as a “second founding” of the Ming dynasty.

The first Ming emperor, who took the personal title Hongwu (Vast Military Power), was prolifically procreative, fathering 36 sons and 16 daughters. Although none of his successors produced so many, the opening section of the exhibition, “Ming Courts,” radically reassesses the importance of these male heirs as agents of the emperor’s rule. The dispatch of these princes to the provinces played a hitherto underestimated part in projecting the dynasty’s image through the length and breadth of China.

A fuller appreciation of the grandeur of these princely courts — in Xi’an the court took up half the area of the city — has been made possible above all by the excavation of princely tombs in recent years. A selection of finds from tombs in Sichuan, Shandong and Hubei vividly bring alive the lavish lifestyles of these provincial courts, the traces of which have mostly disappeared above ground.

The finds include clothes, ornaments, gold jewelry, ceramic figures, and furniture; there is even a set of miniature furniture from the Prince of Lu’s tomb in Shandong, including a bed with pillows and mattress, wash stands with towels, and storage boxes.

A tasseled crown excavated from the tomb of Prince Huang of Lu in Yanzhou.CreditShandong Museum

Innovations in the visual arts also opened windows into the life of the imperial court. At the instigation of the Xuande emperor, a new genre emerged of paintings showing the “Son of Heaven” at leisure. A wonderful scroll here, “Amusements in the Xuande Emperor’s Palace,” on loan from the Palace Museum in Beijing, shows him watching an archery competition, a polo match, soccer; playing a form of miniature golf; participating in an arrow-throwing game; and taking refreshments and retiring with his entourage in the evening. Xuande, known as “the aesthete,” was also an accomplished artist, as is shown by two of his own paintings on display.

Blue and white porcelain was not a Ming invention, but during the Yongle emperor’s reign it reached dizzy new heights of refinement. New clay recipes made it possible for vessels to become thinner, and new glazes produced a much purer translucent white and a glossier finish. A far greater range of shapes was introduced, including a number inspired by bottles, flasks, jugs, candleholders and pen boxes from the Islamic world. The exhibition includes a fascinating series of juxtapositions of porcelain items with brass vessels of Middle Eastern origin.

The imperial court fostered the development of more exotic color schemes, combining red and green, yellow and red, and green and white. The size of some orders given to the imperial kilns was staggering: One for 443,500 porcelain pieces with dragon and phoenix designs was placed in 1433, during the Xuande emperor’s reign.

The role of Middle East-inspired designs and of cobalt from Iran, which gave a stronger blue than the local product, in the perfection of blue-and-white porcelain are both telling markers of another central initiative of the Ming emperors of the first half of the 15th century: the opening up of China to the wider world. This occurred well over half a century before Portuguese and Spanish ships appeared on the horizon, which according to traditional Eurocentric historical narratives was the primary force in exposing China to foreign influences.

Sign up for the Louder Newsletter

Between 1405 and 1433, the eunuch Admiral Zheng He made seven voyages into the so-called Western Ocean, an area extending from the South China Sea to the east coast of Africa and the Red Sea. The impact of these expeditions, which lasted two years at a time, on trading and cultural relations between South Asia and the Middle East is the subject of the last section of the show, “Diplomacy and Trade.”

Zheng He’s expeditions were born of the dynasty’s desire to establish, internationally, the legitimacy of its rule in China and to exact recognition of its primacy in the entire hemisphere, either through persuasion and gifts or military threats. The admiral’s armadas consisted of as many as 250 ships, some of them 60 meters long, at the time the largest ever built. These huge treasure ships carried porcelain, lacquer, silks and other precious Chinese goods, and were escorted by up to 27,000 men, most of them armed.

Although the prime purpose of the voyages was political, they played a major part in distributing Chinese goods westward and bringing back to China cargos of pepper, spices and artifacts — not to mention gems, gold and silver bullion. And, as exported luxury Chinese goods began to trickle into far-distant Europe, not the least of the consequences was to stimulate adventurous European navigators to set out across the oceans in search of the sources of these wonders in the mythical regions of “Cathay.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/16/ar...