Catching up on Classics (and lots more!) discussion

This topic is about

Howards End

Old School Classics, Pre-1915

>

Howards End - SPOILERS

There is a lot going on in this novel, from misplaced philanthropy to how to conduct a marriage. I enjoyed it in places but did not find it easy to read...there were just sections were I found my eyes glazing over and I wanted the story to progress at a better pace.

Helen irritated me. She never seemed to have any thought for the people around her (i.e. Margaret) and yet she professed to care so much about others that she made ridiculous gestures and meddled far too easily into their lives. I found her a bit emotionally unbalanced, which was of course the intent because it offered a contrast to reasonable Margaret. Still, I couldn't like her and I thought her unbridled happiness at the end of the book was quite undeserved.

I'm still chewing on this one, so I am looking forward to what others think.

Helen irritated me. She never seemed to have any thought for the people around her (i.e. Margaret) and yet she professed to care so much about others that she made ridiculous gestures and meddled far too easily into their lives. I found her a bit emotionally unbalanced, which was of course the intent because it offered a contrast to reasonable Margaret. Still, I couldn't like her and I thought her unbridled happiness at the end of the book was quite undeserved.

I'm still chewing on this one, so I am looking forward to what others think.

I read this a long time ago and remember not liking this one very much, mainly due to some of the characters.

I read this a long time ago and remember not liking this one very much, mainly due to some of the characters.

Interesting... I had the opposite response to this book. I haven't cared much for Forster before this, but I really liked this book. I liked his comments about the English class system, about the relations between men and women, about how society affects individual lives, and the difference between the artistic/spiritual and the practical/rational points of view.

Interesting... I had the opposite response to this book. I haven't cared much for Forster before this, but I really liked this book. I liked his comments about the English class system, about the relations between men and women, about how society affects individual lives, and the difference between the artistic/spiritual and the practical/rational points of view.

I read this book many years ago, 2004. There really is not time for a reread now. My main memory of the book all these years later is how terribly things turned out for the poor clerk, as the Schlegels somehow imagined they were helping him. I also remember the plot took many twists and turns. There were some likeable characters. In the end Margaret I think turned out well.

I read this book many years ago, 2004. There really is not time for a reread now. My main memory of the book all these years later is how terribly things turned out for the poor clerk, as the Schlegels somehow imagined they were helping him. I also remember the plot took many twists and turns. There were some likeable characters. In the end Margaret I think turned out well.

I finished this a few days ago, and while I enjoyed it there were some things that bothered me. The philosophical ramblings at the beginning of the chapters bored me. I don't usually mind that kind of thing, so I'm not sure why it did this time but I had to skim through those parts.

I finished this a few days ago, and while I enjoyed it there were some things that bothered me. The philosophical ramblings at the beginning of the chapters bored me. I don't usually mind that kind of thing, so I'm not sure why it did this time but I had to skim through those parts.I found it incredible that Margaret so quickly developed the love for Henry that she did. He was not at all the kind of man one would have paired her with since he was not interested in intellectual pursuits, and he was condescending about things that were important to Helen and Margaret like women's rights. Margaret seemed to think she could change him over time if she could only love him which seems a very naive attitude to relationships. I was happy when she finally stood up to Henry when Helen needed her at the end.

Helen was likeable but annoying to me. She had passionate ideas about the poor, but she didn't really do concrete things to help. I understand that she felt responsible for Leonard changing jobs and then losing his new one, but showing up at the wedding with the Basts and thinking it would do any good seems like poor judgement. She knew Wilcoxes would not care about the Basts' plight and this was only meant to embarrass with little possibility of assistance. Her idealism is admirable but it never amounts to much.

It isn't exactly a good vs evil story, but it is a story of conflicting values. The Schlegels value intellectual and cultural pursuits and muse about how money makes it easier, but they don't see making money as end unto itself, which annoys me since they didn't need to make a living. The Wilcoxes value money to have possessions and are very concerned about getting ahead financially and keeping what they have. They have little concern for the poor or of anyone outside their social class.

I think readers are meant to admire the Schlegels and dislike the Wilcoxes, which we do. And we can rejoice in the end when Margaret and Helen essentially win and Henry and Charles lose. That is a rather simplistic view but that's how I see it, and the ending in which the main characters get their due kind of bothers me. Especially since the Basts are a huge part of the story at the end and Leonard has a heartbreaking death while Jacky's future isn't mentioned at all. It was an unsatisfying resolution to the book for me as it seems too shallow.

Laurie wrote: "I found it incredible that Margaret so quickly developed the love for Henry that she did. He was not at all the kind of man one would have paired her with since he was not interested in intellectual pursuits, and he was condescending about things that were important to Helen and Margaret like women's rights. Margaret seemed to think she could change him over time if she could only love him which seems a very naive attitude to relationships. I was happy when she finally stood up to Henry when Helen needed her at the end...."

Laurie wrote: "I found it incredible that Margaret so quickly developed the love for Henry that she did. He was not at all the kind of man one would have paired her with since he was not interested in intellectual pursuits, and he was condescending about things that were important to Helen and Margaret like women's rights. Margaret seemed to think she could change him over time if she could only love him which seems a very naive attitude to relationships. I was happy when she finally stood up to Henry when Helen needed her at the end...."I don't think Margaret began as any kind of a feminist, unless in the abstract intellectual sense. I think she had reached an age where any kind of interest from a prospective husband would have been wonderful, especially if you consider the plight of unattached women surviving in a world at that time.

I also think Margaret was a benevolent person with a generous heart who would have had no problem learning to love someone she thought was a good man... and Henry certainly wasn't evil, he was thoughtful and generous according to typical male behavior at the time of the story. Even when the novel was published (1910) the idea of women expressing their own minds and talking back to husbands was only just emerging. So Margaret's passionate resistance to Henry's typical male behavior toward the end of the novel, at the time the book was published in England (1910), was probably considered heroic and radical.

Also, people didn't marry so much for love, as for property and security. Most couples figured they would either learn to love each other, or at the least find ways to get along. The idea of falling madly in love as a prerequisite to marriage was a very romantic and idealist notion that didn't have much to do with the reality of the times.

I would agree that Margaret had reached an age that attention from a man of standing would be agreeable, but her plight was not so terrible since she had an income that met all her needs. And since she did not need a husband to provide a living, she needed one for companionship and Henry was a somewhat odd choice for a companion given their differences. I didn't expect her to marry for love which I don't believe she did, but her love developed so quickly. It was all but instantaneous when he proposed.

I would agree that Margaret had reached an age that attention from a man of standing would be agreeable, but her plight was not so terrible since she had an income that met all her needs. And since she did not need a husband to provide a living, she needed one for companionship and Henry was a somewhat odd choice for a companion given their differences. I didn't expect her to marry for love which I don't believe she did, but her love developed so quickly. It was all but instantaneous when he proposed.

Laurie wrote: "I would agree that Margaret had reached an age that attention from a man of standing would be agreeable, but her plight was not so terrible since she had an income that met all her needs. And since..."

Laurie wrote: "I would agree that Margaret had reached an age that attention from a man of standing would be agreeable, but her plight was not so terrible since she had an income that met all her needs. And since..."I admit it seemed fast, but keep in mind she knew for some time that he was entertaining this idea, so she did have time to mull over the thought. It's not too hard to love someone who declares they love you. What I did find very telling and interesting was her disappointment after their first kiss, when Henry kind of grabbed her and planted a lusty (and lustful) kiss. She didn't like the aggressiveness or inherent violence behind it, and that reminded me that not only was she a romantic, she was also a virgin with probably virginal daydreams about physical romance.

I also have to keep in mind that this was written by a male, who might not have had a clue as to how people - women especially - fall in love.

I'm about 3/4 through the novel now. It seems a pretty traditional one, in that there is rather a lot that happens to the characters over a somewhat extended time period.

I'm about 3/4 through the novel now. It seems a pretty traditional one, in that there is rather a lot that happens to the characters over a somewhat extended time period. Characters have different personalities and values which at times mesh well but the emphasis is more on the clashes. Henry Wilcox I see as intelligent (as are all the Schlegels) but particularly flawed, especially in handling and expressing emotion. He couldn't bring himself to tell Margaret how much he cared for her- he believed his marriage proposal made that clear enough.

Margaret was approaching thirty, and was so flattered at a proposal from a man who was not "a ninny" but accomplished in business that she accepted. She believed, as many women do, that she could help him improve his shortcomings (I think some do succeed to some extent, though they are frequently disappointed). They remind me very much of my mother and stepfather who were both in their second marriage, esp since he was a successful businessman (their marriage was a pretty successful one).

About 25 years ago I read E. M. Forster's A Passage to India as well as A Room With a View. I don't know why I didn't read his other famous novel, Howards End back then- I did see the Merchant- Ivory film of it though. I've lived long enough now to finally read Howards End, and I enjoyed it very much. Its kind of funny that even a couple decades after seeing the film, I pictured the actors as the characters as I was reading it. I don't do a lot of five star ratings, but despite a few boring bits I'm giving a five star for this one- great characters, comments on people and life, and a very good story.

About 25 years ago I read E. M. Forster's A Passage to India as well as A Room With a View. I don't know why I didn't read his other famous novel, Howards End back then- I did see the Merchant- Ivory film of it though. I've lived long enough now to finally read Howards End, and I enjoyed it very much. Its kind of funny that even a couple decades after seeing the film, I pictured the actors as the characters as I was reading it. I don't do a lot of five star ratings, but despite a few boring bits I'm giving a five star for this one- great characters, comments on people and life, and a very good story.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. I haven’t seen the film version of this, but I did watch a good BBC adaptation last year, which made me like the book even more.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. I haven’t seen the film version of this, but I did watch a good BBC adaptation last year, which made me like the book even more.

Yay for good BBC adaptations so I can share it with my husband! I really liked this when I read it a couple years ago but am not ready to read it again yet... so many books.

Yay for good BBC adaptations so I can share it with my husband! I really liked this when I read it a couple years ago but am not ready to read it again yet... so many books.

I haven't finished this yet, but so far I like it better than A Room With a View and Where Angels Fear to Thread. (But I only took a middling like to those.)

I haven't finished this yet, but so far I like it better than A Room With a View and Where Angels Fear to Thread. (But I only took a middling like to those.)I have reached that part of the book where Margaret is engaged to Mr. Wilcox and I keep silently screaming, "No, Margaret, don't do it! He's utterly intolerable and self-satisfied, and barrels through discussions by relentlessly listing opinions (like they were facts) that make me want to punch him in the face. Tell her, Helen! You're not even married yet, Mags, and already you're letting him change you while he has no intention of changing at all."

Ok, so I have at least gotten more involved with this book.

I yell at characters too. And sometimes I cringe.

I yell at characters too. And sometimes I cringe.I have also cheered when a character makes a wise decision--like Nora at the end of Ibsen's play, A Doll's House.

Ha ha! I had wondered why Margaret agreed to Mr. Wilcox's proposal. It just seemed to go against everything she'd stood for all along. But then I felt it was all part of her desire 'to connect'.

Ha ha! I had wondered why Margaret agreed to Mr. Wilcox's proposal. It just seemed to go against everything she'd stood for all along. But then I felt it was all part of her desire 'to connect'. I appreciated the vision of this book - but the actual execution was sometimes bogged down too much with extra philosophizing for my taste. I love Forster's progressiveness and the way he writes female characters.

I watched the Merchant Ivory production the other day and loved it. Watching the movie combined with reading the book brought the experience up to another level for me. The casting and acting were superb.

I just finished the book and have now read through all of the group comments above. While I enjoyed it very much, I align my views with Laurie, who expressed her frustrations with it very well. I was bored with the philosophical bits, found the ending wrap up unsatisfying, and was particularly put out that no attention was given to the fate of Jacky.

I just finished the book and have now read through all of the group comments above. While I enjoyed it very much, I align my views with Laurie, who expressed her frustrations with it very well. I was bored with the philosophical bits, found the ending wrap up unsatisfying, and was particularly put out that no attention was given to the fate of Jacky. By the way, the Merchant Ivory film with Emma Thompson as Margaret is quite good. If you liked the book, I recommend the film.

I just finished and really liked. The last 50 pages seemed a little rushed. At times, it made it hard to follow. Almost seemed like a different writer.

I just finished and really liked. The last 50 pages seemed a little rushed. At times, it made it hard to follow. Almost seemed like a different writer.As to the critiques of Margaret, the Afterword in my edition (Signet Classics Centennial edition) said that Margaret was essentially a stand-in for Forster himself.

Howards End by E.M. Forster is our Old School Classic Group Read for January 2026. This is the Spoiler thread, and will reopen on January 1, 2026.

Hello, all. I've been checking on the threads when this was read previously by this group and notice that some people found the book a bit difficult to get into. It is quite dialogue-driven at times, which I found hard to get into at first. I have just finished chapter 5, the scene at the concert and returning home. I can't say I find the characters compelling yet. How is everyone else finding it?

Hello, all. I've been checking on the threads when this was read previously by this group and notice that some people found the book a bit difficult to get into. It is quite dialogue-driven at times, which I found hard to get into at first. I have just finished chapter 5, the scene at the concert and returning home. I can't say I find the characters compelling yet. How is everyone else finding it?

I read this one in 2019, so it has been a while. I loved it then, will be interesting to see if I enjoy it as much the second read through.

Tom wrote: "Hello, all. I've been checking on the threads when this was read previously by this group and notice that some people found the book a bit difficult to get into. It is quite dialogue-driven at time..."

Tom wrote: "Hello, all. I've been checking on the threads when this was read previously by this group and notice that some people found the book a bit difficult to get into. It is quite dialogue-driven at time..."I haven't started rereading this yet, but I know it took me some time to feel like the book was working for me. Then I ended up loving it. So I'd encourage you to just keep reading, if you can, and try and put your judgment of it aside for a while longer.

I'll be joining mid-month, after I get through a couple other short ones. I read this so long ago that I remember almost nothing of it. Looking forward to it!

I'll be joining mid-month, after I get through a couple other short ones. I read this so long ago that I remember almost nothing of it. Looking forward to it!

I am reading this one for the first time this month, although I saw the 1992 film with Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson years ago and loved it. Fortunately, I can’t remember the plot although I do remember liking the film okay. I was always a fan of those Merchant Ivory productions.

I am reading this one for the first time this month, although I saw the 1992 film with Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson years ago and loved it. Fortunately, I can’t remember the plot although I do remember liking the film okay. I was always a fan of those Merchant Ivory productions. I’ve only just started reading (on chapter 6) but I will get more aggressive about it this week.

I just started yesterday, and I'm on Chapter 4 now.

I just started yesterday, and I'm on Chapter 4 now.I enjoyed the dueling arrogances of Charles and Aunt Juley in Chapter 3. It's fascinating how the class distinctions are at work here, with the suburban Wilcox family on one side, and Aunt Juley from what she considers the real "England" on the other. Aunt Juley wonders about where they are headed:

"Into which country will it lead, England or Suburbia?"

She doesn't seem too fond of what she calls the "superficial comfort exacted by business men." It's fun, this clash of worlds, but it's serious too.

And it's also interesting to go back to times when political lines were drawn so differently, when the conservatives were on the side of the landed gentry and concerned about ecology and liberals were instead the party of business under the banner of "progress." It's a good reminder that the collections of political beliefs that are considered left or right or belonging to one party or another do adapt and shift over time, with particular causes or issues flip-flopping from one party to the other; the arrangement is actually somewhat arbitrary, based on political power centers and the alliances of the moment. I find it kind of comforting to spend some time in an environment so different than our own, and I enjoy the way that Forster gently pokes fun at each characters' various pretensions.

I thought I would listen to the audiobook, but I soon switched to the ebook. Forster's writing is something I want to enjoy on the page - to re-read, to look things up (e.g. the painter Maud Goodman - oh my goodness!), to re-listen (Beethoven's Fifth!) - and to explore the depths of Forster's symbolism. Forster's strange plots are only understandable to me as expressions of something more general than the doings of his characters.

I thought I would listen to the audiobook, but I soon switched to the ebook. Forster's writing is something I want to enjoy on the page - to re-read, to look things up (e.g. the painter Maud Goodman - oh my goodness!), to re-listen (Beethoven's Fifth!) - and to explore the depths of Forster's symbolism. Forster's strange plots are only understandable to me as expressions of something more general than the doings of his characters. just a personal aside: I have also started to reread Sense and Sensibility with another group, and had to put it down for a while because I tend to mix up the pairs of sisters! Is the similarity intentional?

a question to native speakers, please:

a question to native speakers, please: “Oh, Mrs. Wilcox, I have made the baddest blunder. ... "

'bad - badder - baddest' was an absolute no-go when I learned English at school. When I looked it up now, I found references to slang, non-standard, and in all cases modern usage. Here I have Forster using it in 1910. - What did it mean back then? Did it indicate a certain style or social class, or maybe an artistic/aesthetic idiosyncrasy?

sabagrey wrote: "a question to native speakers, please:

sabagrey wrote: "a question to native speakers, please: “Oh, Mrs. Wilcox, I have made the baddest blunder. ... "

'bad - badder - baddest' was an absolute no-go when I learned English at school. When I looked it ..."

So much time has passed since 1910 that I'm not sure even natives of the UK would know for sure about the slang usage of such technically incorrect grammar? Akin to "ain't" in the USA probably, another technically improper grammar that was used widely in regional ways.

My personal uninformed guess is that Forster is just reproducing the way people of those days and that particular class actually talked, maybe? I was reading another of Forster's books recently, and he used the phrase "pi-jaw." Apparently, it's a Victorian and Edwardian slang for giving a sanctimonious lecture, from pious jaw. I had never heard it before, but I'm supposing that people of his day would have known it instantly.

I've gotten to Chapter 8 now, and I'm really enjoying this. It doesn't have a single storyline yet that knits the whole thing together, but I'm appreciating the panoramic view, the mixing of people from very different economic situations and ways of life. It's still for the most part only about "gentlefolk," but it's a very broad view of that group, from those barely out of poverty to the wealthy and with different kinds of wealth as well.

I've gotten to Chapter 8 now, and I'm really enjoying this. It doesn't have a single storyline yet that knits the whole thing together, but I'm appreciating the panoramic view, the mixing of people from very different economic situations and ways of life. It's still for the most part only about "gentlefolk," but it's a very broad view of that group, from those barely out of poverty to the wealthy and with different kinds of wealth as well.I'll write more later, but I find myself marking a number of quotes and passages. There's a lot of wisdom here. I particularly got a kick out of the passage describing John Ruskin writing from his metaphorical "gondola" in the sky about things he barely understands. I like Ruskin's works, but I find a lot of truth in what Forster says in that passage.

I have finished the first for chapters, and will read through another ten chapters tomorrow, now that the discussion is getting on.

I have finished the first for chapters, and will read through another ten chapters tomorrow, now that the discussion is getting on. On "baddest," I took it as a example emphasizing the class differences of the Schlegels and Wilcoxes, but I am not familiar enough with the novel since this is my first read. The novel is a bit complex and challenging for readers not as familiar with British customs much as I imagine Faulkner is for non-Americans, so pardon any incorrect conclusions I may offer on such topics.

Finished.

Finished. A strange book. Definitely a classic that stays with me and raises doubts and questions long after having finished it: I find so many layers of contrasts that I refrain from solving them and decide to savour them instead.

I am on Chapter 18 now. I don’t know but this book feels a bit scattered for me. I noticed the same thing when I read A Room With a View last year. It’s not hard to follow, exactly. But very filled with chat. And all the chat makes me a little unfocused about what I’m supposed to care about.

I am on Chapter 18 now. I don’t know but this book feels a bit scattered for me. I noticed the same thing when I read A Room With a View last year. It’s not hard to follow, exactly. But very filled with chat. And all the chat makes me a little unfocused about what I’m supposed to care about. Overall I like the book and the characters. But I’m having trouble feeling at home and ‘comfortable’ in Forster’s writing. Anyway, I’m moving forward!

Beda wrote: "Overall I like the book and the characters. But I’m having trouble feeling at home and ‘comfortable’ in Forster’s writing."

Beda wrote: "Overall I like the book and the characters. But I’m having trouble feeling at home and ‘comfortable’ in Forster’s writing."I think that is a marvellous way to put it. And I also think that is exactly what Forster intended.

My impression in all of Forster's books I have read so far is that he keeps his characters at a distance from the reader. In a strange way, they are not 'really real' for me, but also in part personifications of types and ideas.

Spoilers through Chapter 14:

Spoilers through Chapter 14:I know what Beda means. But for me, this book is looser in focus than Forster's other novels that I have read. It has such a huge amount going on, in so many different philosophical directions! A Room with a View has a lot of talk and society as well, but here, the themes are spreading out more broadly.

One of the aspects I really appreciate so far is the clear-headedness about money and what it does. As Margaret says in Chapter 6, it "pads the edges of things." It can't make people happy, but it can definitely blunt the edges of unpleasant events. An unlucky occurrence that would be a minor nuisance to someone with money is often a complete disaster to someone lacking it. So although it can't make someone happy in itself, it can certainly reduce suffering in ways beneficial to happiness.

I really like this business about the lost umbrella.

Helen takes it as a joke because she can afford to be careless; if she loses her umbrella, she can get another. But for Leonard Bast, it's serious because he can't. And the umbrella becomes a symbol for all those little things, all those minor bumps in life that for someone struggling financially, can rise even to the level of catastrophe.

Imagine if Leonard's lodgings were being torn down to make flats. If he couldn't find lodgings at his current price, what could he do? For Margaret and Helen, it's sad, yes, but it isn't something really to fear as it would be for Leonard.

And Meg is absolutely right that people who have the luxury of leisure time and the luxury of "padding" should really keep in mind that they do have those advantages when they judge the behavior of those who lack them. As Margaret says, "we ought to remember, when we are tempted to criticize others, that we are standing on these islands, and that most of the others are down below the surface of the sea."

It's a little patronizing, but there's truth in it too. It's easy to judge from the island, when we're not swimming. And that's true in many different ways, not only about money. And leisure time can do wonders in clarifying the thoughts. It's easier to see things clearly sitting on an island than it is in the waves, when trying not to drown!

But one part where Margaret veers closest to patronizing is in Chapter 14, when she looks down upon those who, despite lacking leisure time, try to cross the gulf between what she calls the "natural man" and the "philosophic man." She says that "many good chaps" are "wrecked" in failing to fully cross from one to the other and getting stuck between. But in a way, what she is really saying is that a little knowledge is dangerous, because people can think they know more than they do. And effectively, this section suggests that people should stay in their place, as in . . . because the working class don't have the free time to study properly; they should leave such things alone, presumedly to their betters.

I happen to be reading Maurice at the moment as well, and one of the characters in that book says, "They [the poor] haven't our feelings. They don't suffer as we should in their place." Ouch.

I don't think Forster is necessarily endorsing such views, but he's skirting the line, faithfully reproducing views that are probably commonly held in his time and letting the reader decide for themselves between the alternatives he presents. I do feel some deep conflictedness in Forster here. He wants to be clear headed, and he's trying to figure out what is both truthful and humane. Even if sometimes I feel awkward where he's put me, I do like that he makes me think.

Another thing Forster seems deeply conflicted about in this book is progress with a capital "P." There are advantages, surely, but there is also something being lost. Like the pulling down of Wickham place. People need the denser lodgings that the flats represent, but it comes at a cost.

I like the part in Chapter 8 about the local superstitions about the wych-elm with the pig's teeth that has a bark that the locals think cures toothache. And Mrs. Wilcox says that because the people believed in it, the bark "could cure anything--once." The bark is scientific nonsense, of course, but it still did the people good because of how much they believed in it. And now, that is lost. That tree could stand for many things, I think.

Anyway, lots to ponder, and I'll continue reading further tonight. The library book is due back Friday; so I have an artificial deadline that is propelling me along!

my hardback edition has a motif of little red umbrellas on the cover:

my hardback edition has a motif of little red umbrellas on the cover:

I think to emphasise its "only connect" significance

Darren wrote: "my hardback edition has a motif of little red umbrellas on the cover:

Darren wrote: "my hardback edition has a motif of little red umbrellas on the cover:

I think to emphasise its "only connect" significance"

Love that Darren!

WARNING: Big Spoiler for Chapter 18:

WARNING: Big Spoiler for Chapter 18:----------------------------------------------------------

I was surprisingly moved by Mr. Wilcox' proposal to Margaret. I like her as a person; she seems to mean everyone well. And it's nice that at a point where she had practically given up on having a spouse, she is given the option of at least that sort of special companionship. I enjoyed vicariously experiencing her internal happiness at the news.

The novel is plugging along at a fairly sedate pace, but I'm still enjoying it quite a bit.

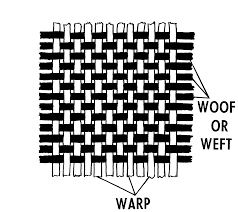

Another idea in Chapter 15 related to money: I liked Margaret's idea that money is the woof/weft of life, with the warp of life varying from person to person. The woof of money is what gives a person the wherewithal to choose, mount, and implement their other main passion crosswise, and the two are intimately intwined together. This doesn't represent every sort of life that's possible, for sure. But it does represent a very common, practical way of making human meaning, and it does that deftly.

Greg wrote: "I was surprisingly moved by Mr. Wilcox' proposal to Margaret. I like her as a person; she seems to m..."

Greg wrote: "I was surprisingly moved by Mr. Wilcox' proposal to Margaret. I like her as a person; she seems to m..."How this marriage comes into being and how it works (or not) is one of the things that puzzle me in this book. I don't understand it and I am so naughty as to suspect that Forster does not understand it either.

The closest I can get in my speculations is that it is guided by "opposites attract", at least in Margaret's case, and that she admires the other-ness of Wilcox' world of steadfast money and economy and practicality. But her admiration is somewhat in the abstract - one cannot pretend to love a man because the likes of him are the pillars of progress and wealth!? And what sort of "special companionship" can it be when she does not expect him to understand her, right from the beginning?

The only solution to the puzzle I have found for myself is the more symbolic meaning of the (attempted) marriage of two worlds, the intellectual vs. the commercial.

sabagrey wrote: "How this marriage comes into being and how it works (or not) is one of the things that puzzle me in this book. I don't understand it and I am so naughty as to suspect that Forster does not understand it either.."

sabagrey wrote: "How this marriage comes into being and how it works (or not) is one of the things that puzzle me in this book. I don't understand it and I am so naughty as to suspect that Forster does not understand it either.."sabagrey, the way I take it personally is that both of their options are extremely limited in their social worlds. It's horrifying to contemplate, but Margaret is probably already considered an old maid by that society she's living in; have you ever read The Odd Women by George Gissing?

The way I read it, Margaret has already mentally closed off the possibility of marriage for herself, especially since she is considered the less attractive and sociable of the two sisters. She seems much the more intelligent and wiser of the two sisters, but that isn't a quality that's much prized in the marriage market of those days. And she has lost hope that she'll actually find anyone to marry.

Does she really love Mr. Wilcox in a modern way? Probably not.

But that's a big thing in that era and culture, to be able to marry at all and to take that social position as a wife. And in terms of finances and social standing, Mr. Wilcox is a great catch. Another bonus is that he doesn't try to restrain her intellectual pursuits. He doesn't really understand her and he feels patronizing toward her, but he doesn't resent her having her own opinions either. It must feel refreshing to be able to discuss things openly with a man of his type, in her own manner, and to still be accepted. As limited as Mr. Wilcox is, I suspect that most of the other eligible men of that time and class wouldn't be as understanding as he is. For example, Charles by comparison is a boor. I get the feeling from their conversations that the two of them actually enjoy their talks; Margaret strikes me as a very genuine person; she doesn't put on airs.

From the other side, Mr. Wilcox is getting old. He doesn't have Mrs. Wilcox anymore, and he's extremely lonely. I think he finds Margaret's spunk and originality refreshing; he doesn't really take her seriously, but he does enjoy her spark. Talking to her and spending time with her isn't boring. It doesn't surprise me at all that he would find her an attractive mate.

If they were to meet in modern times, they'd be an absolutely terrible match. But given the culture they're living in, they seem to fit together quite well, by comparison. And I think they fit each other better than most of the other potential marriage matches in their world would fit.

That's just my own way of seeing it, and I'm only mid-Chapter 18 so there's a whole lot more coming. Perhaps, my feelings will adjust as I go. I have no idea what is coming next!

(view spoiler) is one of my fave bits in the film - it's played in a beautifully moving yet understated way by Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson

(view spoiler) is one of my fave bits in the film - it's played in a beautifully moving yet understated way by Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson

Darren wrote: "[spoilers removed] is one of my fave bits in the film - it's played in a beautifully moving yet understated way by Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson"

Darren wrote: "[spoilers removed] is one of my fave bits in the film - it's played in a beautifully moving yet understated way by Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson"I'm looking forward to watching the movie after finishing the book Darren. I loved it when I watched it, but it was so many years ago that I remember almost nothing about it!

Greg wrote: "But that's a big thing in that era and culture, to be able to marry at all and to take that social position as a wife."

Greg wrote: "But that's a big thing in that era and culture, to be able to marry at all and to take that social position as a wife."don't forget: we are in 1910, in the 20th century, not somewhere in the depths of Victorian times. There's divorce; women, even married ones, are now legal persons and can hold onto their property; there are more and more working women from the middle class, doing skilled work; women can go to university (even if they can't get degrees everywhere). etc. etc. And the social pressure to marry is declining all the time - with more and more single women, including those who live with partners without marriage (think of George Eliot, decades earlier)

Margaret, in particular, has no formal education, and no profession, but a comfortable income. She need not marry for economic reasons and financial security. She need not marry for status, especially within her circle of intellectual acquaintances. (Another, very modern-looking, way of life is shown toward the end of the novel)

sabagrey wrote: "don't forget: we are in 1910, in the 20th century, not somewhere in the depths of Victorian times. There's divorce; women, even married ones, are now legal persons and can hold onto their property; there are more and more working women from the middle "

sabagrey wrote: "don't forget: we are in 1910, in the 20th century, not somewhere in the depths of Victorian times. There's divorce; women, even married ones, are now legal persons and can hold onto their property; there are more and more working women from the middle "I think you have some really good points sabagrey. This is the Edwardian era rather than the Victorian era, and certainly, there was a lot less financial and social pressure to marry than earlier.

The book was published in 1910, but it's not completely clear to me when the book is set, maybe sometime between 1900-1910? Certainly pre-WW1. I do think I really muddled things by bringing up The Odd Women.

But changes aren't monolithic and instantaneous, and there is a difference between needing to marry and wanting to marry. Even nowadays, there are some people who regret not having the experience of marriage or couplehood, despite the fact that they have no real financial need to do it. I get the feeling from the book that Margaret was at least in the back of her mind regretting that the time for finding a husband might have passed her by. She has been standing in her sister's shadow. She's less beautiful, and the book says that she's a little socially awkward in knowing how to put people at ease. I think she found it a nice surprise to be desired by someone with the social standing of Mr. Wilcox, and as I said in my prior post, I do get the feeling that both of them genuinely enjoy their conversations.

"Yet she liked being with him. He was not a rebuke, but a stimulus, and banished morbidity."

What she feels is not sexual passion; it is not wild but still, it is pleasant. She describes her feeling for Mr. Wilcox as "the all-pervading happiness of fine weather." When she considers marrying him, "her brain . . . tingled a little." So, on the one hand, she has a man that she feels pleasant with and enjoys.

And on the other hand, her vague fears for her future:

"She had once visited a spinster . . . whose mania it was that every man who approached her fell in love. How Margaret's heart had bled for the deluded thing! How she had lectured, reasoned, and in despair, acquiesced! . . . It had always seemed to her the most hideous corner of old age, yet she might be driven into it herself by the mere pressure of virginity."

The Edwardian era is not the same as Victorian times, but it is not quite modern either. There are multiple references in the book to the sisters possibly close to becoming old maids.

I understand where you're coming from; the two of them are very different people. But within that society, I personally don't find them to be such a bad match? Margaret seems intelligent and relatively capable; she'd be perfectly fine on her own, but deep down, I think she does want a match for herself.

... and I feel that with the "match" Forster transcends the layer of individual characters and is looking at it as a (necessary?) challenge to society: to reconcile the idealistic with the pragmatic, maybe; or rather than reconcile, confront them in a dialectic way so that a synthesis might emerge?

... and I feel that with the "match" Forster transcends the layer of individual characters and is looking at it as a (necessary?) challenge to society: to reconcile the idealistic with the pragmatic, maybe; or rather than reconcile, confront them in a dialectic way so that a synthesis might emerge?This is the sense I get that I mentioned somewhat earlier: that the characters point to societal conditions beyond themselves, and that Forster does not fully commit himself to their individuality and 'personhood'. They appear to me always a bit diaphanous, like wide-angle lenses that capture their surroundings at the cost of their solidity.

sabagrey wrote: "... and I feel that with the "match" Forster transcends the layer of individual characters and is looking at it as a (necessary?) challenge to society: to reconcile the idealistic with the pragmati..."

sabagrey wrote: "... and I feel that with the "match" Forster transcends the layer of individual characters and is looking at it as a (necessary?) challenge to society: to reconcile the idealistic with the pragmati..."That's interesting sabagrey.

For sure, Forster is writing about big social trends that are beyond these individual characters. I guess I still see the characters as individuals myself, but I do also see them as representing different social and economic groups too. He's careful to choose people from very different classes and positions to show how those groups interact. It isn't an accident. And I completely agree that they point to social conditions beyond themselves.

I agree that this is not a deep psychological character study in a modern way; it's more of a societal study. These characters feel "alive" to me, even though deep psychological characterization isn't Forster's main focus. But I can definitely understand the way you see it, and I totally get why you see it that way.

In Chapter 25 now:

In Chapter 25 now:Oh my, Mr. Wilcox isn't one of those people that improves upon acquaintance, is he? All the signs were there, but somehow, I had deceived myself. I had no idea how controlling he was going to turn out to be, and I can't imagine this is going to end well. Margaret says that she hadn't deceived herself, but I don't know if I believe her; I suspect this is turning out differently than she had imagined.

How monstrously callous he is:

"As civilization moves forward, the shoe is bound to pinch in places, and it's absurd to pretend that anyone is responsible personally."

Ugh.

I still feel like I kind of understand why Margaret made the choice she did in the moment that she made it, but it's starting to look like it might have been a horrible one.

Or perhaps things will not go in the direction I'm thinking? I guess I'll see!

Chapter 37:

Chapter 37:Getting into the final chapters now. I'm on chapter 38, with about 6 chapters to go.

This book is fascinating because even more than the other novels, it does seem to be about England as much as or even more than about the characters. And Howard's End is an important symbol of what Forster perhaps worries is being lost in England. I was really touched by the line in Chapter 37 about Howard's End:

"It kills what is dreadful and makes what is beautiful live"

The house itself brings out what is best in the people who live within it. And that's perhaps because it is a house that is intended to live among the small things, like the love that Helen and Margaret still find they share toward the end, despite having no common ground.

". . . they could never be parted because their love was rooted in common things."

Books mentioned in this topic

The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox (other topics)The Yellow Wallpaper (other topics)

The Odd Women (other topics)

The Odd Women (other topics)

Howards End (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

George Gissing (other topics)John Ruskin (other topics)

E.M. Forster (other topics)

E.M. Forster (other topics)

Discuss any spoilers in this thread.