The Old Curiosity Club discussion

The Old Curiosity Shop

>

TOCS Chapter 31-35

Chapter the Thirty-second

Mrs Jarley was understandably upset when she hears about the threats issued by Miss Monflathers and decides that rather than retaliating she will gather her friends around her and drink her despair away. This remedy was successful and Mrs Jarley is finally able to laugh and ridicule Miss Monflathers. Sadly, Nell’s problem with her father cannot be remedied with a bit of liquor. Her grandfather continues to slink away at night to gamble, continues to lose, and continues to insist that he will soon be a winner. This puts Nell is a very uncomfortable position. Does she continue to enable her grandfather’s gambling habit by giving him the money they earn or does she risk saying no to his weakness and thus create the possibility he may try and steal from Mrs Jarley? Who can Nell turn to for help; what can Nell do?

In the next part of the chapter we turn to one of those incidences that Dickens is so well known. In the previous chapter there was one of Miss Monflathers’s students, a Miss Edwards, who, in kindness, returned to Nell the handkerchief she had dropped. Nell sees Miss Edwards one evening greeting a stage-coach. On the coach was the younger sister of Miss Edwards, a person she had not seen for five years and had saved all her money to see once again. Nell watches this tableau of great love and emotion unfold in front of her eyes. Nell then follows the two sisters for the evening and then again next day follows the Edwards sisters and felt “a companionship and delight to be so near them.” Dickens tells us that for Nell “it was a weak fancy perhaps, the childish fancy of a young and lonely creature; but night after night ... the sisters loitered in the same place, and still [Nell] followed with a mild and softened heart.”

Thoughts

I know some of you enjoy finding within each character’s name a deeper meaning, suggestion or link to the character’s personality. What do you have to suggest for Mrs Jarley and Miss Monflathers?

In this chapter we see a great example of how Dickens knits previous people and events together. The “handkerchief” episode of the previous chapter seemed minor, and yet Dickens used it as both a contrast to the earlier events of Chapter 31 and now as a method to evoke pathos and empathy for Nell in this chapter. Do you think the “handkerchief” event was effectually incorporated into the novel? How did you react to Nell’s shadowing the Edwards girls? How does the episode further develop Nell’s character? Did Dickens overstep the bounds of overwriting melodrama in these paragraphs?

I enjoyed the fact that Mrs Jarley announced that the Waxworks were only to remain in the town for one more day and then to read the irony in brackets that “ all announcements connected with public amusements are well known to be irrevocable and most exact.” Ah, shades of the Crummles of NN. Mrs Jarley realizes the market for people to pay to see the waxworks is drying up. We are then treated to a series of tricks that Mrs Jarley uses entice the public to pay to see the waxworks. As the chapter ends I thought of Dickens’s own relationship with the theatre. Were the tactics employed in this chapter the standard practices of provincial theatre life? I imagine they were. We see a similar pattern in today’s advertising and announcements. I’m a child of the Sixties. Both The Rolling Stones and The Who are having yet another final tour this summer and passing through Toronto. Long live Rock and Roll!

Thoughts

This is a rather short chapter. Are you finding the inconsistency of chapter length to be, in any way, a hindrance to your enjoyment of the novel?

Our next chapter will take us back to London. Before we leave Nell and her grandfather, to what extent do you find Dickens exceeding the boundaries of acceptable melodrama and pathos in the novel to date? If you were an editor, what would you delete, shorten, or alter in the novel?

Mrs Jarley was understandably upset when she hears about the threats issued by Miss Monflathers and decides that rather than retaliating she will gather her friends around her and drink her despair away. This remedy was successful and Mrs Jarley is finally able to laugh and ridicule Miss Monflathers. Sadly, Nell’s problem with her father cannot be remedied with a bit of liquor. Her grandfather continues to slink away at night to gamble, continues to lose, and continues to insist that he will soon be a winner. This puts Nell is a very uncomfortable position. Does she continue to enable her grandfather’s gambling habit by giving him the money they earn or does she risk saying no to his weakness and thus create the possibility he may try and steal from Mrs Jarley? Who can Nell turn to for help; what can Nell do?

In the next part of the chapter we turn to one of those incidences that Dickens is so well known. In the previous chapter there was one of Miss Monflathers’s students, a Miss Edwards, who, in kindness, returned to Nell the handkerchief she had dropped. Nell sees Miss Edwards one evening greeting a stage-coach. On the coach was the younger sister of Miss Edwards, a person she had not seen for five years and had saved all her money to see once again. Nell watches this tableau of great love and emotion unfold in front of her eyes. Nell then follows the two sisters for the evening and then again next day follows the Edwards sisters and felt “a companionship and delight to be so near them.” Dickens tells us that for Nell “it was a weak fancy perhaps, the childish fancy of a young and lonely creature; but night after night ... the sisters loitered in the same place, and still [Nell] followed with a mild and softened heart.”

Thoughts

I know some of you enjoy finding within each character’s name a deeper meaning, suggestion or link to the character’s personality. What do you have to suggest for Mrs Jarley and Miss Monflathers?

In this chapter we see a great example of how Dickens knits previous people and events together. The “handkerchief” episode of the previous chapter seemed minor, and yet Dickens used it as both a contrast to the earlier events of Chapter 31 and now as a method to evoke pathos and empathy for Nell in this chapter. Do you think the “handkerchief” event was effectually incorporated into the novel? How did you react to Nell’s shadowing the Edwards girls? How does the episode further develop Nell’s character? Did Dickens overstep the bounds of overwriting melodrama in these paragraphs?

I enjoyed the fact that Mrs Jarley announced that the Waxworks were only to remain in the town for one more day and then to read the irony in brackets that “ all announcements connected with public amusements are well known to be irrevocable and most exact.” Ah, shades of the Crummles of NN. Mrs Jarley realizes the market for people to pay to see the waxworks is drying up. We are then treated to a series of tricks that Mrs Jarley uses entice the public to pay to see the waxworks. As the chapter ends I thought of Dickens’s own relationship with the theatre. Were the tactics employed in this chapter the standard practices of provincial theatre life? I imagine they were. We see a similar pattern in today’s advertising and announcements. I’m a child of the Sixties. Both The Rolling Stones and The Who are having yet another final tour this summer and passing through Toronto. Long live Rock and Roll!

Thoughts

This is a rather short chapter. Are you finding the inconsistency of chapter length to be, in any way, a hindrance to your enjoyment of the novel?

Our next chapter will take us back to London. Before we leave Nell and her grandfather, to what extent do you find Dickens exceeding the boundaries of acceptable melodrama and pathos in the novel to date? If you were an editor, what would you delete, shorten, or alter in the novel?

Chapter the Thirty - third

I really enjoy the occasional instances of interpolations that Dickens treats his readers to in his novels. The beginning of this chapter is a case in point. He tells us that this chapter is a good place to introduce us to “the domestic economy of Mr Sampson Brass” and offers to take “the friendly reader by the hand, and springing with him into the air, ... [alight] with him upon the pavement of Bevis Marks.” Once landed, the readers, who Dickens calls “intrepid aeronautics” find themselves at the home of Sampson Brass. It is a very dirty home, “discoloured by the sun” and very “threadbare.” In summary, the reader is told that “There was not much to look at.” If it is possible, it is worse inside the house. There is a sign that announces that the first floor is for let to a single person. I think I’ll look elsewhere.

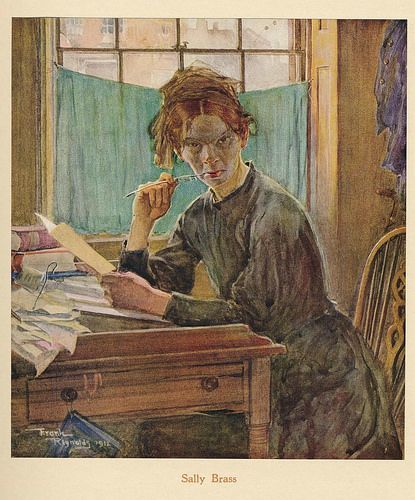

Mr Brass’s sister is his “clerk ... assistant ... intriguer, and bill of cost increased.” She is a woman of “thirty-five or thereabouts, of gaunt and bony figure, and a resolute bearing.” It is stated that she looked so like her brother that even a close friend could not really tell them apart. For those of you who enjoy lavish descriptions Dickens carries on her description for another paragraph. In summary, neither brother or sister Brass are very attractive. We learn that the Brass duo are going to employ a clerk. Actually, there is a catch to all this. It appears that Quilp wants them to take on none other than Dick Swiveller as their clerk. Quilp presents himself at the window, and “ogling the fair Miss Brass” calls her the “Virgin of Bevis.” A short time later Quilp comments that “Miss Sally; there is the woman I should have married - there is the beautiful Sarah - there is the female who has all the charms of her sex and none of the weaknesses. Oh Sally, Sally!” Strange comments? Let’s see what happens later.

Thoughts

There is so much going on in such a short space of time. Let’s see if we can untangle some of the setting and events.

Bevis Marks, the home of the Samuel and Sally Brass, is yet another derelict location. In what ways does the physical place reflect its inhabitants?

What do you think the Brass’s true feelings about Quilp are? To what extent do they reflect these feelings in front of Quilp? Why or why not?

What possible reason would Quilp have to seek employment for Dick Swiveller at the Brass’s law firm?

What do you make of Quilp’s comments to Sally? What do you find most distressing about his comments and treatment of females so far in the novel? Do you think the Victorian reading public would have a much different response to Quilp than modern readers?

Quilp establishes the rules for Dick’s employment with Brass. Sally will teach Dick “the delightful study of the law.” Brass does not object; indeed, he fawns over Quilp’s decision. The only question appears to be where will Swiveller sit. The answer is on a “second-hand stool” that will be purchased as soon as possible.

And now to the curious way Quilp leaves Bevis Marks. As Quilp leaves he mounts the same window-sill he poked his head in at the beginning of the chapter and “looked into the office for a moment with a grinning face, as a man might peep into a cage.” As Swiveller looks at Sally, he sees her deep into the delights of bookkeeping “working like a steam-engine” and he wonders how “he got into the company of that strange monster, and whether it was a dream and he would ever wake.” Dick develops “horrible desires to annihilate” Sally. In order to assuage this desire he picks up a ruler and brandishes it “after the tomahawk manner.” Sally works on unaware of Dick’s actions. Our chapter ends with Dick calming down and beginning to work, albeit with much less vigorous than Sally.

Thoughts

Have you noticed how Quilp always appears to be poking his head into doorways and windows? What might this suggest?

What do you think Dickens wanted to suggest with the simile “as a man might peep into a cage.”?

Did you notice that Dickens used the phrase “working like a steam-engine” to describe Sally’s work ethic? In chapter 31 Miss Monflathers tells Nell she should improve her mind “by the constant contemplation of the steam-engine.” Both these chapters were written in 1840 when the development of steam power was the major progressive force in England. I think the use of the word “steam-engine” is an interesting example of micro-history. To the Victorian reading audience, the reference to steam-engines would have much more of an impact and meaning than to us. Also, in the illustration by Charles Green that depicts Quilp crossing the Thames at night is, as Mary Lou mentioned, remarkable. In the background centre of the illustration we see a steam driven ship, another emblem of the new progressive world of England. This new Victorian world is, to Little Nell, frightening. She and her grandfather lived in a place that dwelt in the items of the past. It was an old curiosity shop. I think the words suggest a world that has been lost in the industrialized world of the Victorians. When we get to Dombey and Son we will see much more clearly the impact of the railway on England. For now, however, it might be interesting to frame this novel as one that shows how the past world of England is represented by Nell and the contents of the Curiosity Shop. In contrast, Quilp is a representative of the new aggressive financial and economic order. He is, first and foremost, a business man. Could we even see him as a precursor to the mindset of Scrooge in A Christmas Carol?

I really enjoy the occasional instances of interpolations that Dickens treats his readers to in his novels. The beginning of this chapter is a case in point. He tells us that this chapter is a good place to introduce us to “the domestic economy of Mr Sampson Brass” and offers to take “the friendly reader by the hand, and springing with him into the air, ... [alight] with him upon the pavement of Bevis Marks.” Once landed, the readers, who Dickens calls “intrepid aeronautics” find themselves at the home of Sampson Brass. It is a very dirty home, “discoloured by the sun” and very “threadbare.” In summary, the reader is told that “There was not much to look at.” If it is possible, it is worse inside the house. There is a sign that announces that the first floor is for let to a single person. I think I’ll look elsewhere.

Mr Brass’s sister is his “clerk ... assistant ... intriguer, and bill of cost increased.” She is a woman of “thirty-five or thereabouts, of gaunt and bony figure, and a resolute bearing.” It is stated that she looked so like her brother that even a close friend could not really tell them apart. For those of you who enjoy lavish descriptions Dickens carries on her description for another paragraph. In summary, neither brother or sister Brass are very attractive. We learn that the Brass duo are going to employ a clerk. Actually, there is a catch to all this. It appears that Quilp wants them to take on none other than Dick Swiveller as their clerk. Quilp presents himself at the window, and “ogling the fair Miss Brass” calls her the “Virgin of Bevis.” A short time later Quilp comments that “Miss Sally; there is the woman I should have married - there is the beautiful Sarah - there is the female who has all the charms of her sex and none of the weaknesses. Oh Sally, Sally!” Strange comments? Let’s see what happens later.

Thoughts

There is so much going on in such a short space of time. Let’s see if we can untangle some of the setting and events.

Bevis Marks, the home of the Samuel and Sally Brass, is yet another derelict location. In what ways does the physical place reflect its inhabitants?

What do you think the Brass’s true feelings about Quilp are? To what extent do they reflect these feelings in front of Quilp? Why or why not?

What possible reason would Quilp have to seek employment for Dick Swiveller at the Brass’s law firm?

What do you make of Quilp’s comments to Sally? What do you find most distressing about his comments and treatment of females so far in the novel? Do you think the Victorian reading public would have a much different response to Quilp than modern readers?

Quilp establishes the rules for Dick’s employment with Brass. Sally will teach Dick “the delightful study of the law.” Brass does not object; indeed, he fawns over Quilp’s decision. The only question appears to be where will Swiveller sit. The answer is on a “second-hand stool” that will be purchased as soon as possible.

And now to the curious way Quilp leaves Bevis Marks. As Quilp leaves he mounts the same window-sill he poked his head in at the beginning of the chapter and “looked into the office for a moment with a grinning face, as a man might peep into a cage.” As Swiveller looks at Sally, he sees her deep into the delights of bookkeeping “working like a steam-engine” and he wonders how “he got into the company of that strange monster, and whether it was a dream and he would ever wake.” Dick develops “horrible desires to annihilate” Sally. In order to assuage this desire he picks up a ruler and brandishes it “after the tomahawk manner.” Sally works on unaware of Dick’s actions. Our chapter ends with Dick calming down and beginning to work, albeit with much less vigorous than Sally.

Thoughts

Have you noticed how Quilp always appears to be poking his head into doorways and windows? What might this suggest?

What do you think Dickens wanted to suggest with the simile “as a man might peep into a cage.”?

Did you notice that Dickens used the phrase “working like a steam-engine” to describe Sally’s work ethic? In chapter 31 Miss Monflathers tells Nell she should improve her mind “by the constant contemplation of the steam-engine.” Both these chapters were written in 1840 when the development of steam power was the major progressive force in England. I think the use of the word “steam-engine” is an interesting example of micro-history. To the Victorian reading audience, the reference to steam-engines would have much more of an impact and meaning than to us. Also, in the illustration by Charles Green that depicts Quilp crossing the Thames at night is, as Mary Lou mentioned, remarkable. In the background centre of the illustration we see a steam driven ship, another emblem of the new progressive world of England. This new Victorian world is, to Little Nell, frightening. She and her grandfather lived in a place that dwelt in the items of the past. It was an old curiosity shop. I think the words suggest a world that has been lost in the industrialized world of the Victorians. When we get to Dombey and Son we will see much more clearly the impact of the railway on England. For now, however, it might be interesting to frame this novel as one that shows how the past world of England is represented by Nell and the contents of the Curiosity Shop. In contrast, Quilp is a representative of the new aggressive financial and economic order. He is, first and foremost, a business man. Could we even see him as a precursor to the mindset of Scrooge in A Christmas Carol?

Chapter the Thirty-fourth

This chapter opens with Miss Brass finishing her work and announcing she is going out to which Dick Swiveller gleefully responds “Very good ma’am ... And don’t hurry yourself on my account to come back ma’am.” The last bit he added inwardly. Going forward, I’m hopeful there will many more exchanges between Dick and Sally. I’m beginning to like Swiveller more and more. He seems to be an honest chap. The next few paragraphs fill in some background on how and why Dick finds himself a clerk under the Brasses. In short, he is without friends and without money. Any port in a storm. Not to worry however, for “Mr Swiveller shook off his despondency and assumed the cheerful ease of an irresponsible clerk.” What a great definition of a lazy clerk. Since Dick is alone in the office he takes the opportunity to do a bit of snooping and slacking about in the office. He then settles in to draw caricatures of Miss Brass. I’m liking Dick more and more each paragraph.

His leisure is interrupted by a “small slipshod girl in a dirty coarse apron and bib, which left nothing of her visible but her feet and face.” This young girl had the appearance of being old-fashioned and that she has been working since the cradle. We learn that she does the plain cooking and is the housemaid for the Brasses. The sign in the window of a room to let has attracted an inquiry. The little girl tells Dick that the cost of the lodging is 18 shillings a week with “us finding plate and linen. Boots and clothes is extra, and fires in winter time is eighteen pence a day.”

Thoughts

I have developed a liking for Dick Swiveller. Since Dickens has introduced this character into the Brass plot line with Quilp it is reasonable to assume he will be a recurring character for the remainder of the novel. It appears that Dickens is giving Dick a unique personality. How would you characterize Dick as a character? How might Dickens evolve his character in the novel?

What are your initial impressions of the Brasses housemaid? What does her speech pattern, her dialogue with Dick, and her physical description reveal about her character?

The second part of this chapter introduces yet another new character to us. He is described as a “single gentleman” with a massively heavy travelling trunk. The man has a bald head and was “muffled up in winter garments” thought the temperature outside was 81 in the shade. When he asks the rent Dick happily ups the price to “one pound per week” and the man does not hesitate to agree to such terms. The unnamed man says he will take the rooms for a term of two years. He is quick-witted and can keep up with Dick’s laconic comments. This single gentleman dismisses Dick as soon as he can. Before Dick leaves he watches as the man removes his outer clothing, fold it up and place it with his trunk. He then pulls down the blinds and “leisurely and methodically, got into bed.” He begins to snore immediately. Dick’s response to these rapidly unfolding events is to exclaim “This is a most remarkable and supernatural sort of house!” He is right. He has witnessed “she-dragons in the business ... plain cooks of three feet high appearing mysteriously from underground; [and] strangers walking in and going to bed without leave.” Dick Swiveller sums up all the action of the chapter by saying “it’s no business of mine - I have nothing whatever to do with it.”

Thoughts

What a busy chapter. We have the introduction of two new characters and a wonderful demonstration of Dick Swiveller’s unique view of the world.

First, what are your first impressions of the housemaid? Are there any indication that Dickens intends to expand her role in the novel yet? If so, where do you think her story line could go and who will she be integrated with in future chapters?

Second, the mysterious single gentleman is given close attention by Dickens. We get many hints as to his age, his character, and even his plans. What did you discover about his character? How might Dickens plan to involve this person in the plot?

Finally, we have the character of Dick himself. At the end of the chapter Dick claims that he will not have anything to do with all this activity in the future. To what extent do you think Dick Swiveller will keep himself separate from all the present and possible future activities at Bevis Marks? Why?

This chapter opens with Miss Brass finishing her work and announcing she is going out to which Dick Swiveller gleefully responds “Very good ma’am ... And don’t hurry yourself on my account to come back ma’am.” The last bit he added inwardly. Going forward, I’m hopeful there will many more exchanges between Dick and Sally. I’m beginning to like Swiveller more and more. He seems to be an honest chap. The next few paragraphs fill in some background on how and why Dick finds himself a clerk under the Brasses. In short, he is without friends and without money. Any port in a storm. Not to worry however, for “Mr Swiveller shook off his despondency and assumed the cheerful ease of an irresponsible clerk.” What a great definition of a lazy clerk. Since Dick is alone in the office he takes the opportunity to do a bit of snooping and slacking about in the office. He then settles in to draw caricatures of Miss Brass. I’m liking Dick more and more each paragraph.

His leisure is interrupted by a “small slipshod girl in a dirty coarse apron and bib, which left nothing of her visible but her feet and face.” This young girl had the appearance of being old-fashioned and that she has been working since the cradle. We learn that she does the plain cooking and is the housemaid for the Brasses. The sign in the window of a room to let has attracted an inquiry. The little girl tells Dick that the cost of the lodging is 18 shillings a week with “us finding plate and linen. Boots and clothes is extra, and fires in winter time is eighteen pence a day.”

Thoughts

I have developed a liking for Dick Swiveller. Since Dickens has introduced this character into the Brass plot line with Quilp it is reasonable to assume he will be a recurring character for the remainder of the novel. It appears that Dickens is giving Dick a unique personality. How would you characterize Dick as a character? How might Dickens evolve his character in the novel?

What are your initial impressions of the Brasses housemaid? What does her speech pattern, her dialogue with Dick, and her physical description reveal about her character?

The second part of this chapter introduces yet another new character to us. He is described as a “single gentleman” with a massively heavy travelling trunk. The man has a bald head and was “muffled up in winter garments” thought the temperature outside was 81 in the shade. When he asks the rent Dick happily ups the price to “one pound per week” and the man does not hesitate to agree to such terms. The unnamed man says he will take the rooms for a term of two years. He is quick-witted and can keep up with Dick’s laconic comments. This single gentleman dismisses Dick as soon as he can. Before Dick leaves he watches as the man removes his outer clothing, fold it up and place it with his trunk. He then pulls down the blinds and “leisurely and methodically, got into bed.” He begins to snore immediately. Dick’s response to these rapidly unfolding events is to exclaim “This is a most remarkable and supernatural sort of house!” He is right. He has witnessed “she-dragons in the business ... plain cooks of three feet high appearing mysteriously from underground; [and] strangers walking in and going to bed without leave.” Dick Swiveller sums up all the action of the chapter by saying “it’s no business of mine - I have nothing whatever to do with it.”

Thoughts

What a busy chapter. We have the introduction of two new characters and a wonderful demonstration of Dick Swiveller’s unique view of the world.

First, what are your first impressions of the housemaid? Are there any indication that Dickens intends to expand her role in the novel yet? If so, where do you think her story line could go and who will she be integrated with in future chapters?

Second, the mysterious single gentleman is given close attention by Dickens. We get many hints as to his age, his character, and even his plans. What did you discover about his character? How might Dickens plan to involve this person in the plot?

Finally, we have the character of Dick himself. At the end of the chapter Dick claims that he will not have anything to do with all this activity in the future. To what extent do you think Dick Swiveller will keep himself separate from all the present and possible future activities at Bevis Marks? Why?

Chapter the Thirty-fifth

Is it true that sometimes when we learn more about a mystery the more mysterious it becomes? This chapter is a case in point. At the end of this chapter we will know more about the mysterious lodger of the Brasses, but still have no idea who he is or how he will fit into the story.

The chapter begins with Brass being curious as to who their new lodger is. Brass, we learn, believes that the best way to get information for free is to be lavish with phrases and compliments and so he turns these charms on Dick Swiveller in an attempt to learn about the single gentleman. Sally, for her part, was angry that Dick did not charge more rent from someone who was so eager to lodge with them. Sally has found an office chair for Dick that has one leg longer than the others. The chair reflects the world of Bevis Marks in that both are a bit tilted, wobbly, and misaligned.

The lodger has not been heard from since he arrived. Sally wonders if he is dead upstairs. In order to cover their liability in case the lodger is indeed dead, Mr Brass has Dick draft a note of evidence. It seems that the Brasses are a cautious pair. What follows is a section where Brass, in all his legal glory, examines Dick to get as much information as he can about the new lodger. Through such a method Dickens is able to accomplish three main goals. We get humour through the questions of Brass and, through Dick’s responses, the reader learns more about the lodger. Some of the questions are self-serving, such as did the gentleman say that his personal property would be the Brasses if the lodger were to die. Thus, Dickens is able to further develop the character of both Brass and his sister as well. Brass and Sally have attempted to awaken the lodger by various noisy means. Being unsuccessful, Brass, Sally and Dick decide to use either “violent means” and “stronger measures” in their quest to awaken the lodger.

What follows next is a glorious scene of farce. We have Brass peeping through the door’s keyhole, Sally ringing a hand bell and Dick putting his wobbly stool beside the door and climbing upon it and banging his ruler on the top part of the door. The small servant watches these actions from the safety of the stairwell. Suddenly, the door is “flung violently open.”

Thoughts

Dickens has attempted to create a comic scene in the first part of this chapter. What dramatic purpose do you think he was attempting to create? To what extend has he been successful?

Has your opinion about Sampson Brass, Sally Brass and Dick Swiveller changed from the earlier chapters of the novel? How?

We learn that the lodger’s boots “were as sturdy and bluff a pair of boots as one would wish to see.” What does this suggest about the lodger?

With the door opening suddenly, the small servant flees to the coal-cellar, Sally dives into her bedroom and Sampson flees into the street which leaves our friend Dick standing on a chair with a ruler in his hand. The single gentleman, for his part, is growling and cursing. In short order, however, he regains his composure and invites Dick into his room. So, with Dick as our eyes, let’s look more closely at the lodger and his room.

He is a “brown-faced sun-burnt man. He is choleric in temperament. He is bald and seems bow to have a sense of humour about his recent wake-up call. From his heavy trunk comes a cornucopia of food, drink and “a temple, shining as polished silver” which serves as a stove that “by some wonderful and unseen agency” cooks meat, eggs and makes coffee. The great trunk, we are told, “seemed to hold everything” and worked “these miracles and thought nothing of them.”

The lodger tells Dick that he wants to do as he likes and be asked no questions. He tells Dick that if he is disturbed he will leave and the Brasses will lose a good tenant. And with that, Dick is dismissed. He will not tell Dick his name but does tell Dick that no one will call on him. And so the chapter and this week’s chapters come to a close.

Thoughts

My sense is that we have not seen the last of the lodger. What is your best guess as to who he might be, where he is from, what he is doing in London and, of course, how will he be incorporated into the story in the following chapters?

I’m very interested in the “great trunk which seemed to hold everything.” It appears to have magic properties.” What possible purpose might Dickens have for including it as part of this chapter?

My Reflections

In this week’s reading we have seen the word “steam-engine” used twice. On both occasions it was used as a method of criticism against Nell. As mentioned in my “Thoughts” in Chapter 33, I see these incidences as examples of verbal micro-history. Nell’s world is not one of industry, progress, or commerce. Nell’s world is, rather, represented by where she lives, in an old curiosity shop where past history is on display. Nell even sleeps surrounded by objects from the past. As we progress through the novel it will be interesting to study each place she and her grandfather go. We should reflect on what each place could represent in terms of social history. Could it be that the excessive melodrama in this novel is a lament for the past? To what extent could The Old Curiosity Shop be like Janus, the God who looked both backward and forward? What is it about the past that is important? What is it about the past that needs to be carried forward?

As we move through the novel I remain very interested in how Dickens consistently weaves elements of the fairy tale world into the story of Little Nell. In this week’s chapters we have an unnamed man who is mysterious, who has a magical trunk that contains all sorts of food and drink and a device that can prepare cooked food upon demand. Who is this man? How will he fit into the narrative? What archetype might he represent?

Also, when I think of food I can’t forget Quilp’s rather bizarre choice of foods and his eating habits. Should I be paying more attention to the presence of food and the trope of consumption in all its various meanings in this novel? How might food and its consumption help me understand and appreciate the novel more?

Is it true that sometimes when we learn more about a mystery the more mysterious it becomes? This chapter is a case in point. At the end of this chapter we will know more about the mysterious lodger of the Brasses, but still have no idea who he is or how he will fit into the story.

The chapter begins with Brass being curious as to who their new lodger is. Brass, we learn, believes that the best way to get information for free is to be lavish with phrases and compliments and so he turns these charms on Dick Swiveller in an attempt to learn about the single gentleman. Sally, for her part, was angry that Dick did not charge more rent from someone who was so eager to lodge with them. Sally has found an office chair for Dick that has one leg longer than the others. The chair reflects the world of Bevis Marks in that both are a bit tilted, wobbly, and misaligned.

The lodger has not been heard from since he arrived. Sally wonders if he is dead upstairs. In order to cover their liability in case the lodger is indeed dead, Mr Brass has Dick draft a note of evidence. It seems that the Brasses are a cautious pair. What follows is a section where Brass, in all his legal glory, examines Dick to get as much information as he can about the new lodger. Through such a method Dickens is able to accomplish three main goals. We get humour through the questions of Brass and, through Dick’s responses, the reader learns more about the lodger. Some of the questions are self-serving, such as did the gentleman say that his personal property would be the Brasses if the lodger were to die. Thus, Dickens is able to further develop the character of both Brass and his sister as well. Brass and Sally have attempted to awaken the lodger by various noisy means. Being unsuccessful, Brass, Sally and Dick decide to use either “violent means” and “stronger measures” in their quest to awaken the lodger.

What follows next is a glorious scene of farce. We have Brass peeping through the door’s keyhole, Sally ringing a hand bell and Dick putting his wobbly stool beside the door and climbing upon it and banging his ruler on the top part of the door. The small servant watches these actions from the safety of the stairwell. Suddenly, the door is “flung violently open.”

Thoughts

Dickens has attempted to create a comic scene in the first part of this chapter. What dramatic purpose do you think he was attempting to create? To what extend has he been successful?

Has your opinion about Sampson Brass, Sally Brass and Dick Swiveller changed from the earlier chapters of the novel? How?

We learn that the lodger’s boots “were as sturdy and bluff a pair of boots as one would wish to see.” What does this suggest about the lodger?

With the door opening suddenly, the small servant flees to the coal-cellar, Sally dives into her bedroom and Sampson flees into the street which leaves our friend Dick standing on a chair with a ruler in his hand. The single gentleman, for his part, is growling and cursing. In short order, however, he regains his composure and invites Dick into his room. So, with Dick as our eyes, let’s look more closely at the lodger and his room.

He is a “brown-faced sun-burnt man. He is choleric in temperament. He is bald and seems bow to have a sense of humour about his recent wake-up call. From his heavy trunk comes a cornucopia of food, drink and “a temple, shining as polished silver” which serves as a stove that “by some wonderful and unseen agency” cooks meat, eggs and makes coffee. The great trunk, we are told, “seemed to hold everything” and worked “these miracles and thought nothing of them.”

The lodger tells Dick that he wants to do as he likes and be asked no questions. He tells Dick that if he is disturbed he will leave and the Brasses will lose a good tenant. And with that, Dick is dismissed. He will not tell Dick his name but does tell Dick that no one will call on him. And so the chapter and this week’s chapters come to a close.

Thoughts

My sense is that we have not seen the last of the lodger. What is your best guess as to who he might be, where he is from, what he is doing in London and, of course, how will he be incorporated into the story in the following chapters?

I’m very interested in the “great trunk which seemed to hold everything.” It appears to have magic properties.” What possible purpose might Dickens have for including it as part of this chapter?

My Reflections

In this week’s reading we have seen the word “steam-engine” used twice. On both occasions it was used as a method of criticism against Nell. As mentioned in my “Thoughts” in Chapter 33, I see these incidences as examples of verbal micro-history. Nell’s world is not one of industry, progress, or commerce. Nell’s world is, rather, represented by where she lives, in an old curiosity shop where past history is on display. Nell even sleeps surrounded by objects from the past. As we progress through the novel it will be interesting to study each place she and her grandfather go. We should reflect on what each place could represent in terms of social history. Could it be that the excessive melodrama in this novel is a lament for the past? To what extent could The Old Curiosity Shop be like Janus, the God who looked both backward and forward? What is it about the past that is important? What is it about the past that needs to be carried forward?

As we move through the novel I remain very interested in how Dickens consistently weaves elements of the fairy tale world into the story of Little Nell. In this week’s chapters we have an unnamed man who is mysterious, who has a magical trunk that contains all sorts of food and drink and a device that can prepare cooked food upon demand. Who is this man? How will he fit into the narrative? What archetype might he represent?

Also, when I think of food I can’t forget Quilp’s rather bizarre choice of foods and his eating habits. Should I be paying more attention to the presence of food and the trope of consumption in all its various meanings in this novel? How might food and its consumption help me understand and appreciate the novel more?

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Thirty-first...

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Thirty-first...As many have noted, this is a rather soggy novel thanks to Nell...."

I think this coming week I'm going to making a drinking game out of TOCS, and take a swig every time Nell cries. I wonder how sloshed I'll get!

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Thirty-second

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Thirty-secondWhat do you have to suggest for Mrs Jarley and Miss Monflathers?

..."

Peter, as child of the sixties you'll get this -- the only thing that pops into my head when I read the name "Monflathers" is "...and Jerry Mathers as the Beaver." Do what you can with that! :-)

As to Mrs Jarley, I already put in my two cents about that -- when you listen to the name read with an English accent, it sounds remarkably like "Mrs. Jolly".

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Thirty-second

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Thirty-second"...or does she risk saying no to his weakness and thus create the possibility he may try and steal from Mrs Jarley?..."

Again Nell shows me a very astute side. Not having any gamblers in the family, I never would have taken this to it's logical solution, i.e. Trent stealing from Mrs. Jarley. And yet, Nell takes this into account immediately. She's weepy, but she's also savvy.

Mary Lou wrote: "Again Nell shows me a very astute side. Not having any gamblers in the family, I never would have taken this to it's logical solution, i.e. Trent stealing from Mrs. Jarley. And yet, Nell takes this into account immediately. She's weepy, but she's also savvy..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Again Nell shows me a very astute side. Not having any gamblers in the family, I never would have taken this to it's logical solution, i.e. Trent stealing from Mrs. Jarley. And yet, Nell takes this into account immediately. She's weepy, but she's also savvy..."Yes. I like how she told Grandpa about the theft in a way that preserved his dignity and gave him an "out" to return the money without embarrassment,

"I lost some money last night—out of my bedroom, I am sure. Unless it was taken by somebody in jest—only in jest, dear grandfather, which would make me laugh heartily if I could but know it—"

Perhaps it is too sweet and unrealistic, but I thought it was clever. Nell reminds me of the resourceful princess in fairy tales who uses her smarts and her charm to get out of tricky situations.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter the Thirty-second

What do you have to suggest for Mrs Jarley and Miss Monflathers?

..."

Peter, as child of the sixties you'll get this -- the only thing that pops into my he..."

Mary Lou

Oh, poor Beaver and Wally if Monflanders was their mom.

:-)

What do you have to suggest for Mrs Jarley and Miss Monflathers?

..."

Peter, as child of the sixties you'll get this -- the only thing that pops into my he..."

Mary Lou

Oh, poor Beaver and Wally if Monflanders was their mom.

:-)

There was much to be enjoyed for me in this week‘s chapters, e.g. Mrs. Jarley‘s wise way of dealing with the contemptuous attitude shown to her and her wax empire by that puny Miss Monflathers; also Mrs. Jarley‘s routine of changing her exhibits with regard to what her potential customers might expect, and I also liked to see how Mr. Swiveller puts up with his new situation. I do wonder, however, where Fred Trent is, and why he is fading out of the picture. Not that I‘d miss him, emotionally, but his presence in the story would add a potential for conflict. Saying that, maybe, Dickens thought that one really evil character was enough, and so he kept Quilp and neglected Fred ...

What I did not like, however, was this melodramatic scene of Miss Monflathers‘ picking on Little Nell and the ensuing humiliation of poor Miss Edwards. It has been done so often, especially by Dickens, whose teachers are often given to pompous or egoistic and tyrannical behaviour, and whose poor dependants are invariably men and women of dignity and blamelessness, that I could have done without this predictable, stale scene this time.

It is probably meant to show us something about Little Nell, though, but there is hardly anything worth saying about Little Nell that can‘t be summarized in one sentence. And I am talking of simple sentences, without any sub-clauses, here.

What made matters even worse was to see how Little Nell would stalk the two sisters from a distance, vicariously living through them, or pitying them (or whatever). It is a very creepy image: Little Nell tailing those two sisters from a distance, feeding on every emotion between them. This might be seen as another sign that she ought to get rid of that Grandfather of hers somehow and fall in with some people who care for her, too. But then she would not be the unimpeachable, holier-than-the-rest-of-us-all Little Nell anymore.

End of rant, for now.

What I did not like, however, was this melodramatic scene of Miss Monflathers‘ picking on Little Nell and the ensuing humiliation of poor Miss Edwards. It has been done so often, especially by Dickens, whose teachers are often given to pompous or egoistic and tyrannical behaviour, and whose poor dependants are invariably men and women of dignity and blamelessness, that I could have done without this predictable, stale scene this time.

It is probably meant to show us something about Little Nell, though, but there is hardly anything worth saying about Little Nell that can‘t be summarized in one sentence. And I am talking of simple sentences, without any sub-clauses, here.

What made matters even worse was to see how Little Nell would stalk the two sisters from a distance, vicariously living through them, or pitying them (or whatever). It is a very creepy image: Little Nell tailing those two sisters from a distance, feeding on every emotion between them. This might be seen as another sign that she ought to get rid of that Grandfather of hers somehow and fall in with some people who care for her, too. But then she would not be the unimpeachable, holier-than-the-rest-of-us-all Little Nell anymore.

End of rant, for now.

Tristram wrote: "But then she would not be the unimpeachable, holier-than-the-rest-of-us-all Little Nell anymore."

What a beautiful description of poor Little Nell, I knew you would see the light some day. :-)

What a beautiful description of poor Little Nell, I knew you would see the light some day. :-)

Peter wrote: "Who is worse, Quilp or grandfather Trent? What is your reasoning?"

Grandfather Trent. Quilp is a whole bunch of bad things, but at least we always know that, he doesn't hide a thing about it, he even enjoys it. Grandfather Trent on the other hand is poor old Grandfather who needs Nell and anyone else who comes along I suppose, to do everything for him, meanwhile he's stealing money from her and gambling it all away.

Grandfather Trent. Quilp is a whole bunch of bad things, but at least we always know that, he doesn't hide a thing about it, he even enjoys it. Grandfather Trent on the other hand is poor old Grandfather who needs Nell and anyone else who comes along I suppose, to do everything for him, meanwhile he's stealing money from her and gambling it all away.

Peter wrote: "Nell is too good, too forgiving, and the scene too melodramatic for even me,"

No Peter, not you too! You were all I had left to fight against the grumpiness that is sent my way from across the sea. :-)

No Peter, not you too! You were all I had left to fight against the grumpiness that is sent my way from across the sea. :-)

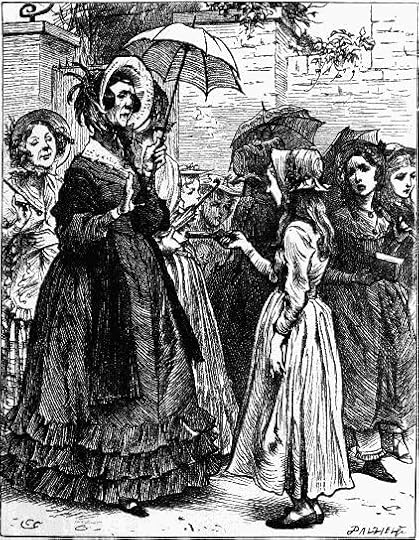

Miss Monflathers chides Nell

Chapter 31

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

As Nell approached the awful door, it turned slowly upon its hinges with a creaking noise, and, forth from the solemn grove beyond, came a long file of young ladies, two and two, all with open books in their hands, and some with parasols likewise. And last of the goodly procession came Miss Monflathers, bearing herself a parasol of lilac silk, and supported by two smiling teachers, each mortally envious of the other, and devoted unto Miss Monflathers.

Confused by the looks and whispers of the girls, Nell stood with downcast eyes and suffered the procession to pass on, until Miss Monflathers, bringing up the rear, approached her, when she curtseyed and presented her little packet; on receipt whereof Miss Monflathers commanded that the line should halt.

‘You’re the wax-work child, are you not?’ said Miss Monflathers.

‘Yes, ma’am,’ replied Nell, colouring deeply, for the young ladies had collected about her, and she was the centre on which all eyes were fixed.

‘And don’t you think you must be a very wicked little child,’ said Miss Monflathers, who was of rather uncertain temper, and lost no opportunity of impressing moral truths upon the tender minds of the young ladies, ‘to be a wax-work child at all?’

Poor Nell had never viewed her position in this light, and not knowing what to say, remained silent, blushing more deeply than before.

‘Don’t you know,’ said Miss Monflathers, ‘that it’s very naughty and unfeminine, and a perversion of the properties wisely and benignantly transmitted to us, with expansive powers to be roused from their dormant state through the medium of cultivation?’

The two teachers murmured their respectful approval of this home-thrust, and looked at Nell as though they would have said that there indeed Miss Monflathers had hit her very hard. Then they smiled and glanced at Miss Monflathers, and then, their eyes meeting, they exchanged looks which plainly said that each considered herself smiler in ordinary to Miss Monflathers, and regarded the other as having no right to smile, and that her so doing was an act of presumption and impertinence.

‘Don’t you feel how naughty it is of you,’ resumed Miss Monflathers, ‘to be a wax-work child, when you might have the proud consciousness of assisting, to the extent of your infant powers, the manufactures of your country; of improving your mind by the constant contemplation of the steam-engine; and of earning a comfortable and independent subsistence of from two-and-ninepence to three shillings per week? Don’t you know that the harder you are at work, the happier you are?’

‘“How doth the little—“’ murmured one of the teachers, in quotation from Doctor Watts.

‘Eh?’ said Miss Monflathers, turning smartly round. ‘Who said that?’

Of course the teacher who had not said it, indicated the rival who had, whom Miss Monflathers frowningly requested to hold her peace; by that means throwing the informing teacher into raptures of joy.

‘The little busy bee,’ said Miss Monflathers, drawing herself up, ‘is applicable only to genteel children.

Commentary:

Unlike most Victorian illustrators who merely provided drawings on paper or the woodblock itself, Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz") had the knowledge and skill to carry an illustration all the way from initial conception to final production. Because he served as either the engraver or etcher for his own work, he could achieve a great deal more control over the final appearance of his images than could most illustrators. However, since he constantly complained that the "cutters" damaged his designs and failed to capture his full intention, we may reasonably conclude that, especially as the commissions poured in, he often jobbed out the work of cutting after he had transferred the designs to the blocks.

Whereas wood engraving requires creating a picture in relief, cutting away wood from the lines to be printed, etching requires the cutting of lines into a wax-covered metal plate (usually of steel) in an intaglio process. Browne was adept at working in both mediums; Steig's study of Phiz's working drawings reveals that many of the details in the plates were inserted after the process of transferring the drawing to the steel was complete.

Although the illustrations for The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge, both of which appeared in the serial Master Humphrey's Clock, were wood engravings integrated with Dickens's text, Browne's usual method of illustrating involved two full-page, detached engraved pictures on separate pages for each issue of a monthly, two-shilling installment of a novel. In contrast to the plates for Master Humphrey's Clock, in Martin Chuzzlewit , for example, Phiz etched the plates. Because etchings, even on steel, do not wear well, Phiz and his life-long assistant, Robert Young, had to create doubles — two copies of each illustration — to produce sufficient copies for Chapman and Hall. As Valerie Browne Lester notes,

wood engravings can be inked and printed simultaneously with the raised typeface, whereas etching plates, with their ink in grooves rather than on the surface, must be sent through a rolling press and printed on individual dampened pages. But the use of wood engravings required that Dickens wait until all the designs were completed before he could work out exactly how much text was needed.

By the time the Household Edition of Dickens's works appeared in the 1870s, new, less labor-intensive and hence less expensive reproductive processes had become popular, processes which lent themselves to different styles of illustration. Increasingly, artists (or rather publishers and printers) used photographic processes, such as photogravure, to transform the illustrator's pen or pencil drawing into a plate capable of printing multiple images. The "wholly new" illustrations in the Household Edition by younger artists, such as Fred Barnard and W. A. Fraser, employed the new process, but, these plates do not have the delicate lines or subtle effects of the original etchings. The advantage of wood-engravings, of course, is that they can be formatted into a page of print, rendering a very effective visual-text synthesis which must have been an enjoyable novelty for readers in the 1860s when the technology came in. However, wood-engravings cannot provide much background detail, so that the artist has to focus on several large-scale figures.

"You're the wax-work child, are you not?"

Chapter 31

Charles Green

Text Illustrated:

‘You’re the wax-work child, are you not?’ said Miss Monflathers.

‘Yes, ma’am,’ replied Nell, colouring deeply, for the young ladies had collected about her, and she was the centre on which all eyes were fixed.

‘And don’t you think you must be a very wicked little child,’ said Miss Monflathers, who was of rather uncertain temper, and lost no opportunity of impressing moral truths upon the tender minds of the young ladies, ‘to be a wax-work child at all?’

Poor Nell had never viewed her position in this light, and not knowing what to say, remained silent, blushing more deeply than before.

‘Don’t you know,’ said Miss Monflathers, ‘that it’s very naughty and unfeminine, and a perversion of the properties wisely and benignantly transmitted to us, with expansive powers to be roused from their dormant state through the medium of cultivation?’

The two teachers murmured their respectful approval of this home-thrust, and looked at Nell as though they would have said that there indeed Miss Monflathers had hit her very hard. Then they smiled and glanced at Miss Monflathers, and then, their eyes meeting, they exchanged looks which plainly said that each considered herself smiler in ordinary to Miss Monflathers, and regarded the other as having no right to smile, and that her so doing was an act of presumption and impertinence.

‘Don’t you feel how naughty it is of you,’ resumed Miss Monflathers, ‘to be a wax-work child, when you might have the proud consciousness of assisting, to the extent of your infant powers, the manufactures of your country; of improving your mind by the constant contemplation of the steam-engine; and of earning a comfortable and independent subsistence of from two-and-ninepence to three shillings per week? Don’t you know that the harder you are at work, the happier you are?’

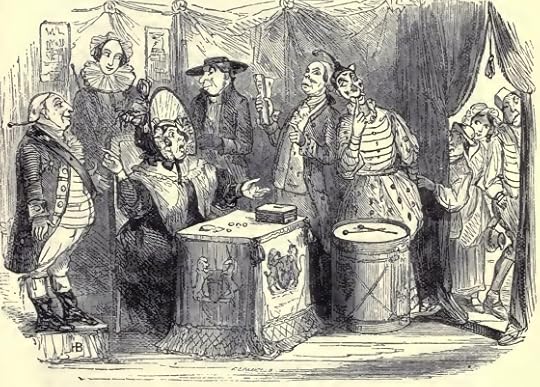

Mrs. Jarley at the Pay Place

Chapter 32

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Upon the following day at noon, Mrs Jarley established herself behind the highly-ornamented table, attended by the distinguished effigies before mentioned, and ordered the doors to be thrown open for the readmission of a discerning and enlightened public. But the first day’s operations were by no means of a successful character, inasmuch as the general public, though they manifested a lively interest in Mrs Jarley personally, and such of her waxen satellites as were to be seen for nothing, were not affected by any impulses moving them to the payment of sixpence a head. Thus, notwithstanding that a great many people continued to stare at the entry and the figures therein displayed; and remained there with great perseverance, by the hour at a time, to hear the barrel-organ played and to read the bills; and notwithstanding that they were kind enough to recommend their friends to patronise the exhibition in the like manner, until the door-way was regularly blockaded by half the population of the town, who, when they went off duty, were relieved by the other half; it was not found that the treasury was any the richer, or that the prospects of the establishment were at all encouraging.

In this depressed state of the classical market, Mrs Jarley made extraordinary efforts to stimulate the popular taste, and whet the popular curiosity. Certain machinery in the body of the nun on the leads over the door was cleaned up and put in motion, so that the figure shook its head paralytically all day long, to the great admiration of a drunken, but very Protestant, barber over the way, who looked upon the said paralytic motion as typical of the degrading effect wrought upon the human mind by the ceremonies of the Romish Church and discoursed upon that theme with great eloquence and morality. The two carters constantly passed in and out of the exhibition-room, under various disguises, protesting aloud that the sight was better worth the money than anything they had beheld in all their lives, and urging the bystanders, with tears in their eyes, not to neglect such a brilliant gratification. Mrs Jarley sat in the pay-place, chinking silver moneys from noon till night, and solemnly calling upon the crowd to take notice that the price of admission was only sixpence, and that the departure of the whole collection, on a short tour among the Crowned Heads of Europe, was positively fixed for that day week.

‘So be in time, be in time, be in time,’ said Mrs Jarley at the close of every such address. ‘Remember that this is Jarley’s stupendous collection of upwards of One Hundred Figures, and that it is the only collection in the world; all others being imposters and deceptions. Be in time, be in time, be in time!’

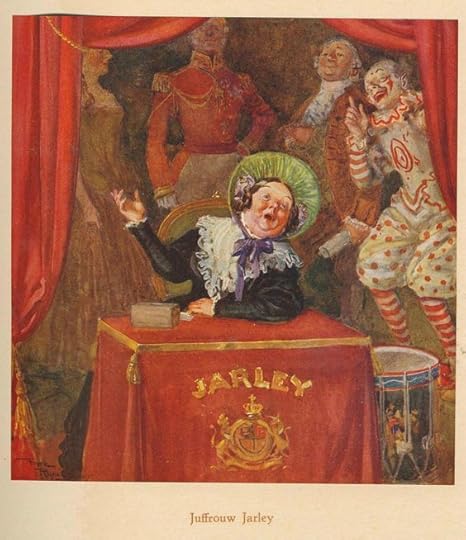

Mrs. Jarley behind the table

Chapter 32

Frank Reynolds

Text Illustrated:

Upon the following day at noon, Mrs Jarley established herself behind the highly-ornamented table, attended by the distinguished effigies before mentioned, and ordered the doors to be thrown open for the readmission of a discerning and enlightened public. But the first day’s operations were by no means of a successful character, inasmuch as the general public, though they manifested a lively interest in Mrs Jarley personally, and such of her waxen satellites as were to be seen for nothing, were not affected by any impulses moving them to the payment of sixpence a head. Thus, notwithstanding that a great many people continued to stare at the entry and the figures therein displayed; and remained there with great perseverance, by the hour at a time, to hear the barrel-organ played and to read the bills; and notwithstanding that they were kind enough to recommend their friends to patronise the exhibition in the like manner, until the door-way was regularly blockaded by half the population of the town, who, when they went off duty, were relieved by the other half; it was not found that the treasury was any the richer, or that the prospects of the establishment were at all encouraging.

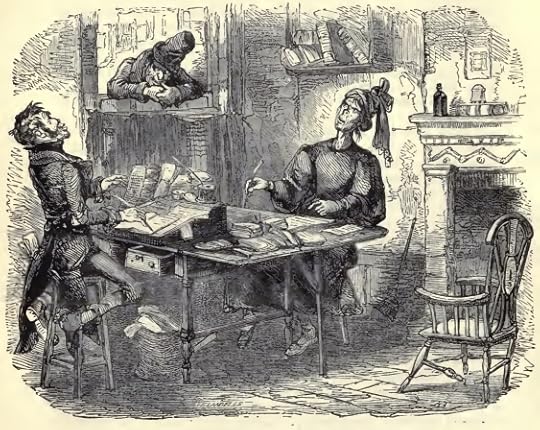

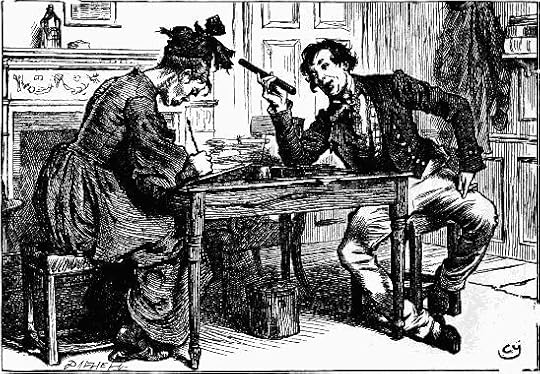

A Colleague for Miss Brass

Chapter 33

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

While they were thus employed, the window was suddenly darkened, as by some person standing close against it. As Mr Brass and Miss Sally looked up to ascertain the cause, the top sash was nimbly lowered from without, and Quilp thrust in his head.

‘Hallo!’ he said, standing on tip-toe on the window-sill, and looking down into the room. ‘Is there anybody at home? Is there any of the Devil’s ware here? Is Brass at a premium, eh?’

‘Ha, ha, ha!’ laughed the lawyer in an affected ecstasy. ‘Oh, very good, Sir! Oh, very good indeed! Quite eccentric! Dear me, what humour he has!’

‘Is that my Sally?’ croaked the dwarf, ogling the fair Miss Brass. ‘Is it Justice with the bandage off her eyes, and without the sword and scales? Is it the Strong Arm of the Law? Is it the Virgin of Bevis?’

‘What an amazing flow of spirits!’ cried Brass. ‘Upon my word, it’s quite extraordinary!’

‘Open the door,’ said Quilp, ‘I’ve got him here. Such a clerk for you, Brass, such a prize, such an ace of trumps. Be quick and open the door, or if there’s another lawyer near and he should happen to look out of window, he’ll snap him up before your eyes, he will.’

It is probable that the loss of the phoenix of clerks, even to a rival practitioner, would not have broken Mr Brass’s heart; but, pretending great alacrity, he rose from his seat, and going to the door, returned, introducing his client, who led by the hand no less a person than Mr Richard Swiveller.

Commentary:

Quilp cavorts through sixteen cuts (excluding one by Cattermole), five of which, following the text, have him thrusting himself through doors and windows, often preceded by his tall, narrow hat. In another he is shown having gone through a gateway. Elsewhere he is usually engaged in violent or disreputable behavior: leaning back in his chair with his feet on the table, smoking a long, upward — pointing cigar while his wife sits by submissively; sitting on his desk while Nell stands apprehensively near by; smoking in the grandfather's chair with his bandy legs halfway up in the air; beating savagely at Dick, whom he has mistaken for his own wife; rolling on the ground, tormenting his dog; sitting on a beer barrel, raucously drinking and enjoying Sampson's discomfort. Also in this the illustration for Chapter 16, the figure of Punch on the tombstone is like an incarnation of Quilp as Nell's pursuer; the puppet even looks as though it is making an obscene gesture at Nell (The first but not the second point has been made by Gabriel Pearson, p. 87). The cumulative effect of Phiz's illustrations is to emphasize embedded sexual nuances and to bring to the novel the vital energy of comic rascality.

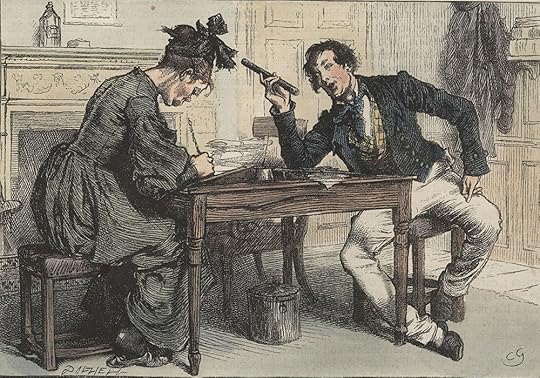

In some of these flourishes it went close to Mill Sally's head

Chapter 33

Charles Green

Text Illustrated:

Mr Swiveller pulled off his coat, and folded it up with great elaboration, staring at Miss Sally all the time; then put on a blue jacket with a double row of gilt buttons, which he had originally ordered for aquatic expeditions, but had brought with him that morning for office purposes; and, still keeping his eye upon her, suffered himself to drop down silently upon Mr Brass’s stool. Then he underwent a relapse, and becoming powerless again, rested his chin upon his hand, and opened his eyes so wide, that it appeared quite out of the question that he could ever close them any more.

When he had looked so long that he could see nothing, Dick took his eyes off the fair object of his amazement, turned over the leaves of the draft he was to copy, dipped his pen into the inkstand, and at last, and by slow approaches, began to write. But he had not written half-a-dozen words when, reaching over to the inkstand to take a fresh dip, he happened to raise his eyes. There was the intolerable brown head-dress—there was the green gown—there, in short, was Miss Sally Brass, arrayed in all her charms, and more tremendous than ever.

This happened so often, that Mr Swiveller by degrees began to feel strange influences creeping over him—horrible desires to annihilate this Sally Brass—mysterious promptings to knock her head-dress off and try how she looked without it. There was a very large ruler on the table; a large, black, shining ruler. Mr Swiveller took it up and began to rub his nose with it.

From rubbing his nose with the ruler, to poising it in his hand and giving it an occasional flourish after the tomahawk manner, the transition was easy and natural. In some of these flourishes it went close to Miss Sally’s head; the ragged edges of the head-dress fluttered with the wind it raised; advance it but an inch, and that great brown knot was on the ground: yet still the unconscious maiden worked away, and never raised her eyes.

Well, this was a great relief. It was a good thing to write doggedly and obstinately until he was desperate, and then snatch up the ruler and whirl it about the brown head-dress with the consciousness that he could have it off if he liked. It was a good thing to draw it back, and rub his nose very hard with it, if he thought Miss Sally was going to look up, and to recompense himself with more hardy flourishes when he found she was still absorbed. By these means Mr Swiveller calmed the agitation of his feelings, until his applications to the ruler became less fierce and frequent, and he could even write as many as half-a-dozen consecutive lines without having recourse to it—which was a great victory.

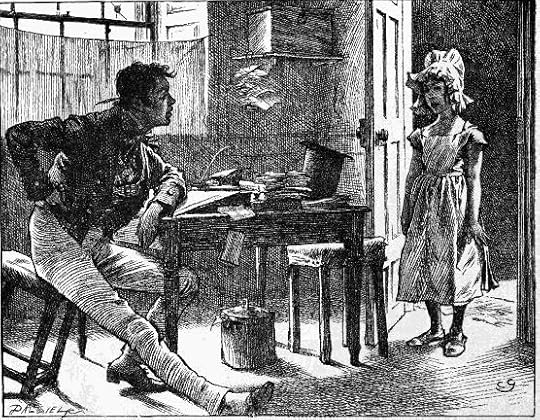

"Oh, please," said a little voice very low down in the doorway, "will you come and show the lodgings?"

Chapter 34

Charles Green

Text Illustrated:

He was occupied in this diversion when a coach stopped near the door, and presently afterwards there was a loud double-knock. As this was no business of Mr Swiveller’s, the person not ringing the office bell, he pursued his diversion with perfect composure, notwithstanding that he rather thought there was nobody else in the house.

In this, however, he was mistaken; for, after the knock had been repeated with increased impatience, the door was opened, and somebody with a very heavy tread went up the stairs and into the room above. Mr Swiveller was wondering whether this might be another Miss Brass, twin sister to the Dragon, when there came a rapping of knuckles at the office door.

‘Come in!’ said Dick. ‘Don’t stand upon ceremony. The business will get rather complicated if I’ve many more customers. Come in!’

‘Oh, please,’ said a little voice very low down in the doorway, ‘will you come and show the lodgings?’

Dick leant over the table, and descried a small slipshod girl in a dirty coarse apron and bib, which left nothing of her visible but her face and feet. She might as well have been dressed in a violin-case.

‘Why, who are you?’ said Dick.

To which the only reply was, ‘Oh, please will you come and show the lodgings?’

There never was such an old-fashioned child in her looks and manner. She must have been at work from her cradle. She seemed as much afraid of Dick, as Dick was amazed at her.

‘I hav’n’t got anything to do with the lodgings,’ said Dick. ‘Tell ‘em to call again.’

‘Oh, but please will you come and show the lodgings,’ returned the girl; ‘It’s eighteen shillings a week and us finding plate and linen. Boots and clothes is extra, and fires in winter-time is eightpence a day.’

‘Why don’t you show ‘em yourself? You seem to know all about ‘em,’ said Dick.

‘Miss Sally said I wasn’t to, because people wouldn’t believe the attendance was good if they saw how small I was first.’

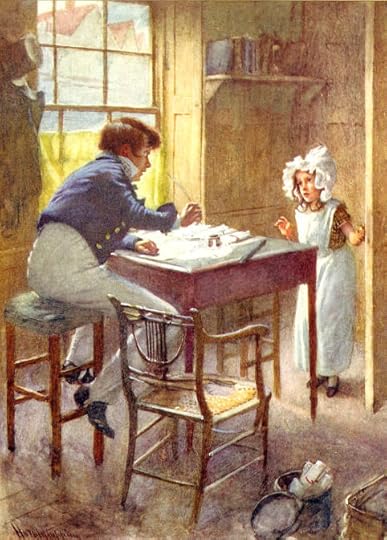

Dick Swiveller Meets the Marchioness

Chapter 34

Harold Copping

1924

Text Illustrated:

‘Come in!’ said Dick. ‘Don’t stand upon ceremony. The business will get rather complicated if I’ve many more customers. Come in!’

‘Oh, please,’ said a little voice very low down in the doorway, ‘will you come and show the lodgings?’

Dick leant over the table, and descried a small slipshod girl in a dirty coarse apron and bib, which left nothing of her visible but her face and feet. She might as well have been dressed in a violin-case.

‘Why, who are you?’ said Dick.

To which the only reply was, ‘Oh, please will you come and show the lodgings?’

There never was such an old-fashioned child in her looks and manner. She must have been at work from her cradle. She seemed as much afraid of Dick, as Dick was amazed at her.

‘I hav’n’t got anything to do with the lodgings,’ said Dick. ‘Tell ‘em to call again.’

‘Oh, but please will you come and show the lodgings,’ returned the girl; ‘It’s eighteen shillings a week and us finding plate and linen. Boots and clothes is extra, and fires in winter-time is eightpence a day.’

‘Why don’t you show ‘em yourself? You seem to know all about ‘em,’ said Dick.

‘Miss Sally said I wasn’t to, because people wouldn’t believe the attendance was good if they saw how small I was first.’

‘Well, but they’ll see how small you are afterwards, won’t they?’ said Dick.

‘Ah! But then they’ll have taken ‘em for a fortnight certain,’ replied the child with a shrewd look; ‘and people don’t like moving when they’re once settled.’

About the artist:

Born in Camden Town in 1863, he was the second son of journalist Edward Copping (1829–1904) and Rose Heathilla (née Prout) (1832–1877), the daughter of John Skinner Prout, the water-colour artist. His brother, Arthur E. Copping, became a noted author, journalist and traveller and was a member of The Salvation Army.

Harold Copping entered London's Royal Academy where he won a Landseer Scholarship to study in Paris. He quickly became established as a successful painter and illustrator, living in Croydon and Hornsey during the early years of his career. Copping had links with the missionary societies of his time including the London Missionary Society (LMS), who commissioned him as an illustrator of Biblical scenes. To achieve authenticity and realism for his illustrations he travelled to Palestine and Egypt. The resulting book, The Copping Bible (1910), became a best-seller and led to more Bible commissions. These included A Journalist in the Holy Land (1911), The Golden Land (1911), The Bible Story Book (1923) and My Bible Book (1931). Copping used family, friends and neighbours as models in his paintings, keeping a stock of costumes and props at his home. In many of his Bible paintings one of his wife's striped tea towels can be seen worn on the heads of various Bible characters. Copping's beautifully executed watercolour illustrations were put onto lantern slides and were used by Christian missionaries all over the world. His pictures were also widely reproduced by missionary societies as posters, tracts and as magazine illustrations.

Probably the most famous of Copping's Bible illustrations was 'The Hope of the World' (1915). This depicts Jesus sitting with a group of children from different continents. Dr. Sandy Brewer wrote of this image: "The Hope of the World, painted by Harold Copping for the London Missionary Society in 1915, is arguably the most popular picture of Jesus produced in Britain in the twentieth century. It was an iconic image in the Sunday school movement between 1915 and 1960". However, James Thorpe, in his book English Illustration: the Nineties wrote: "Harold Copping’s work, capable and honest as it was, does not inspire any great enthusiasm; there are so many artists doing illustrations equally satisfactory in literal translation and equally lacking in strong personal individuality." Copping was under contract to the Religious Tract Society (RTS) to produce 12 religious paintings a year up until the time of his death. He was paid £50 for each painting and, under the terms of the contract, was not allowed to paint religious paintings for any other publisher.

His illustrations for non-religious books included Hammond's Hard Lines (1894), Miss Bobbie (1897), Millionaire (1898), A Queen Among Girls (1900), The Pilgrim's Progress (1903), Westward Ho! (1903), Grace Abounding (1905), Three School Chums (1907), Little Women (1912), Good Wives (1913), A Christmas Carol (1920) and Character Sketches from Boz (1924).[2] He also illustrated the children's books by Mary Angela Dickens based on the novels of her grandfather, Charles Dickens. These included Children's Stories from Dickens (1911) and Dickens' Dream Children (1926).

The Hope of the World

Harold Copping (1915)

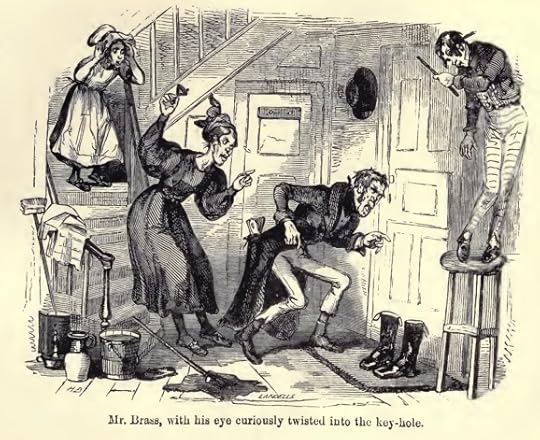

Mr. Brass at the keyhole

Chapter 35

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘What do you say to getting on the roof of the house through the trap-door, and dropping down the chimney?’ suggested Dick.

‘That would be an excellent plan,’ said Brass, ‘if anybody would be—’ and here he looked very hard at Mr Swiveller—‘would be kind, and friendly, and generous enough, to undertake it. I dare say it would not be anything like as disagreeable as one supposes.’

Dick had made the suggestion, thinking that the duty might possibly fall within Miss Sally’s department. As he said nothing further, and declined taking the hint, Mr Brass was fain to propose that they should go up stairs together, and make a last effort to awaken the sleeper by some less violent means, which, if they failed on this last trial, must positively be succeeded by stronger measures. Mr Swiveller, assenting, armed himself with his stool and the large ruler, and repaired with his employer to the scene of action, where Miss Brass was already ringing a hand-bell with all her might, and yet without producing the smallest effect upon their mysterious lodger.

‘There are his boots, Mr Richard!’ said Brass.

‘Very obstinate-looking articles they are too,’ quoth Richard Swiveller. And truly, they were as sturdy and bluff a pair of boots as one would wish to see; as firmly planted on the ground as if their owner’s legs and feet had been in them; and seeming, with their broad soles and blunt toes, to hold possession of their place by main force.

‘I can’t see anything but the curtain of the bed,’ said Brass, applying his eye to the keyhole of the door. ‘Is he a strong man, Mr Richard?’

‘Very,’ answered Dick.

‘It would be an extremely unpleasant circumstance if he was to bounce out suddenly,’ said Brass. ‘Keep the stairs clear. I should be more than a match for him, of course, but I’m the master of the house, and the laws of hospitality must be respected.—Hallo there! Hallo, hallo!’

While Mr Brass, with his eye curiously twisted into the keyhole, uttered these sounds as a means of attracting the lodger’s attention, and while Miss Brass plied the hand-bell, Mr Swiveller put his stool close against the wall by the side of the door, and mounting on the top and standing bolt upright, so that if the lodger did make a rush, he would most probably pass him in its onward fury, began a violent battery with the ruler upon the upper panels of the door. Captivated with his own ingenuity, and confident in the strength of his position, which he had taken up after the method of those hardy individuals who open the pit and gallery doors of theatres on crowded nights, Mr Swiveller rained down such a shower of blows, that the noise of the bell was drowned; and the small servant, who lingered on the stairs below, ready to fly at a moment’s notice, was obliged to hold her ears lest she should be rendered deaf for life.

Suddenly the door was unlocked on the inside, and flung violently open. The small servant flew to the coal-cellar; Miss Sally dived into her own bed-room; Mr Brass, who was not remarkable for personal courage, ran into the next street, and finding that nobody followed him, armed with a poker or other offensive weapon, put his hands in his pockets, walked very slowly all at once, and whistled.

Kim wrote: "Peter wrote: "Nell is too good, too forgiving, and the scene too melodramatic for even me,"

No Peter, not you too! You were all I had left to fight against the grumpiness that is sent my way from ..."

Kim

A momentary lapse in my true self. It must be the length of this Canadian winter. I will happily wrap the snow and cold up and send it to you.

Fear not, you and I will stand firm together. :-)

No Peter, not you too! You were all I had left to fight against the grumpiness that is sent my way from ..."

Kim

A momentary lapse in my true self. It must be the length of this Canadian winter. I will happily wrap the snow and cold up and send it to you.

Fear not, you and I will stand firm together. :-)

Kim wrote: "I almost forgot this:

https://www.abebooks.com/servlet/Sear..."

If the Curiosities would like to start a library I would be happy to keep all the Dickens material at my place. :-)

https://www.abebooks.com/servlet/Sear..."

If the Curiosities would like to start a library I would be happy to keep all the Dickens material at my place. :-)

Kim wrote: "A Colleague for Miss Brass

Chapter 33

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

While they were thus employed, the window was suddenly darkened, as by some person standing close against it. As Mr Brass and Miss S..."

Kim

What a variety of illustrations. No Kyding. I found the commentary to the illustration of message 19 very interesting. In our own commentaries and discussions we have been looking at the degree to which Quilp’s language and activities can be seen as sexually suggestive. In the commentary in message 19 we read how the multiple illustrations of Quilp in the original illustrations also have a very sexual overtone. To me, one of the most interesting aspects of Dickens is seeing how the letterpress and the illustrations relate to each other. What it must have been like for the original readers to “see” the characters and the places within the text of the original parts.

As we move further into Dickens’s novels the detail and the emblematic detail of the illustrations will increase. What fun.

Chapter 33

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

While they were thus employed, the window was suddenly darkened, as by some person standing close against it. As Mr Brass and Miss S..."

Kim