Sci-Fi & Fantasy Girlz discussion

This topic is about

Contact

Group Reads

>

March 2019 - Contact

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Yoly

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Mar 02, 2019 03:57PM

Don't forget to use the spoiler tags! :)

Don't forget to use the spoiler tags! :)

reply

|

flag

Interesting. Twitter (or, at least, that tiny fraction of Twitter that sees/responds my tweets) thought we should read The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. That is the most contemporaneous of those books, and the others all got votes in their publication order, oldest least. It's not like that's nearly large enough a random sample to draw any conclusions, but it's the first thing that leaps out to me when I see the Twitter results:

Interesting. Twitter (or, at least, that tiny fraction of Twitter that sees/responds my tweets) thought we should read The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. That is the most contemporaneous of those books, and the others all got votes in their publication order, oldest least. It's not like that's nearly large enough a random sample to draw any conclusions, but it's the first thing that leaps out to me when I see the Twitter results:

Contact is an interesting choice for this group. Aside from the fact that it's been a movie already (which I guess means at some point I'm going to have to revisit it) Sagan was a really intriguing guy. I've read a few of his science books. Dragons of Eden, Broca's Brain, The Demon-Haunted World, and the nearly obligatory Cosmos. It's been an awful long time since I picked up any of them, though, so I'm curious how his prose stands up.

Just getting into this reread. Alien messages have just been discovered* and the politics is creeping in.

Just getting into this reread. Alien messages have just been discovered* and the politics is creeping in.* I don't think that's a spoiler; the title of the book is "contact" and it's science fiction, so it's safe to say the book isn't about a vision correcting lens.

A few notes:

1. I hadn't picked up on the portrayal of sexism, or I didn't remember it so much from my first reading back in the day. It is interesting to see how much ahead or how anticipatory of the current politics this book is in that regard.

I think back in the day I took that aspect as read more than anything else, which is a pointed thing to recognize all on its own. Interestingly, my niece is off in college right now, which makes her the sixth in a direct line of college educated women in my family. I recall, however, talking about this very subject with family members, and my mother and grandmother both pointing out that their choices of major were fairly limited. So, education and social work were where they wound up. Both my sisters went into the hard sciences (biochemistry and chemistry) and were by their accounts usually the only women in their classes. Astronomy seems like a pretty open field these days, but I wonder....

These elements read as pretty realistic to me this time around, but I'm a middle-class (more or less...), suburban (more or less...), white (more or less...) boy, and may be blinded by my CIS nature, so I'm curious what some of the Girlz Group readers think.

2. Sagan appears to me to be a pretty unabashed "alien apologist". That is, he's one of those folks who believes that a more advanced society will by definition be a more beneficent one. So, Sagan's narrative is that those concerned with things like security when it comes to the content of the messages received from space are being paranoid. That's as opposed to someone like Stephen Hawking who raised concerns about the survival of humanity in contact with a more advanced civilization, comparing the situation to what happened to Native American populations when encountering Europeans.

Personally, I think I might be more inclined to be paranoid than naive when it comes to something like this. The story goes into a pretty massive (view spoiler), a huge portion of which would not necessarily be well understood by Earth's scientists and engineers.

So, let's take a cue from this event:

https://www.zdnet.com/article/us-soft...

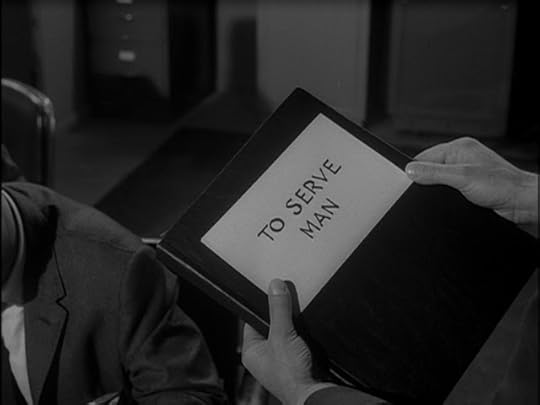

Now, let's say you're a member of an advanced, technological society on another world. Your civilization might be so advanced as to have solved certain things like mortality, and generational (in the sense of time, not actual generations, because people in your civilization don't die anymore...) space travel. You could even travel by wormhole if we're being theoretical about it. Radio astronomy might be something of an archaic tech to you, ever since you've been using tachyon-based communication, but it's as good a method as any to note when another civilization is going to be able and willing to dedicate an awful lot of time to a particular construction program. What if, instead of establishing contact (or Contact) the goal is to get that society to prep their world for colonization a la the film They Live but without the bubblegum? Or maybe that civilization has already made an assessment of human potential and found us lacking, so they send the equivalent of a false flag so we destroy ourselves, like in Species but with more giant asteroids zooming out of a wormhole effect that we point at our own planet for their convenience?

There are as many possibilities as recipes in a cookbook:

Even if we assume a more advanced society is going to be more benevolent, why would we assume it must be monolithically so? It only took a few Europeans to distribute infected blankets to kill off huge swaths of Native Americans, and even in the relatively advanced society in which we live there are still people so misguided as to head off to isolated islands where uncontacted people are minding their own business like this unholier than thou jackass:

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

All it takes is the proverbial "bad apple" in a society. One equivalent of a MAGA teen who wants to "pwn the libruls" because it'll be good for a few laughs.

One of the assumptions of astronomy is that the physics that we observe and utilize on earth is universal, and that does very much seem to the be case, even if we've still just begun to scratch the surface of the universe and its content. (For instance, recently the astronomical estimation of the number of galaxies in our universe was raised from 200 billion to 2 trillion, proving once again that astronomy is the only science that expands faster than the national debt....) We extrapolate in our search for life outside our solar system by using conditions that we see on Earth as the basis for life itself: water, radiation levels, gravity, etc. Yet folks like Sagan assume that as civilizations advance they become more kindly and downright avuncular if not outright paternal. Objectively, it's hard to see the basis for that argument here on Earth.

Interesting that Sagan made the President of the United States a woman in this story. I didn't even remember that from my first reading. It meshes in a weird way with the sexism as portrayed in particularly earlier bits of the novel.

Interesting that Sagan made the President of the United States a woman in this story. I didn't even remember that from my first reading. It meshes in a weird way with the sexism as portrayed in particularly earlier bits of the novel.

It's funny, I'm finding this a lot less plausible this time around than I recall from my first reading (which was an awful long time ago, admittedly.) My objections come more from the arguments that Sagan presents than anything else. There are plot/character issues that I think sci-fi readers have to be more than a little forgiving about. That is, Ellie is the head of SETI and also a main candidate to be (view spoiler) and they manage to build the Machine within a period of time so that that can happen. Which... OK. It's a science fiction book. That might make it a bit more of a soft science fiction book than a hard science fiction book, but it's not that unusual for the genre as a whole.

It's funny, I'm finding this a lot less plausible this time around than I recall from my first reading (which was an awful long time ago, admittedly.) My objections come more from the arguments that Sagan presents than anything else. There are plot/character issues that I think sci-fi readers have to be more than a little forgiving about. That is, Ellie is the head of SETI and also a main candidate to be (view spoiler) and they manage to build the Machine within a period of time so that that can happen. Which... OK. It's a science fiction book. That might make it a bit more of a soft science fiction book than a hard science fiction book, but it's not that unusual for the genre as a whole.What's making me incredulous, however, is that he presents the counter arguments for a lot of that, but is rather dismissive of those counter arguments. He presents them only in so far as to shoot them down as straw men. So, for instance, the speed with which the Machine is built is justified by the fact that the world's superpowers (view spoiler) in response to receiving the Message. I'm not so sure the response of the world's nuclear powers to receiving a message from space would be to disarm, personally. Most of the people making that decision would be the kind of folks who long to deliver the President's speech from Independence Day and it doesn't take much to connect up those dots. If it were just that one thing then it'd be all well and good for the narrative, but a lot more of the counter arguments to building the Machine and dealing with the Message seem to be given such cursory attention that it tracks to me like they should have been left out entirely. That is, there's an argument to be made that building the Machine should be done in a much greater period of time. It should take a generation or two given the amounts of money he's talking about for a single project. His justification for it happening at the speed with which he portrays it is that the world's corporations and governments just can't help themselves jumping on board the project because of the R&D potential it represents.

(view spoiler)Well, OK, maybe... but that doesn't really mean they'd be able to do that given the costs. Building the Machine becomes a kind of surrogate arms race, but one that also has a tone of peace on Earth and goodwill towards all (or most) humankind, which tracks as a little awkward to me. Maybe that's just because I haven't got a message from space yet.... Even with the religious content of the book, nobody points out that cathedrals were begun by one generation and finished two, three, sometimes four generations later. Nobody in the scientific community talks about a "leap of Evolution" that the technology represents.

Similarly, the speed with which the Machine is built is given an explanation that to me tracks as more than a little pie in the sky, almost to being dismissive:

(view spoiler)From a story standpoint, I think this makes sense because Sagan wants his protagonist to be both the discoverer of the message and the person who responds to it personally, but I don't know that it would play out like that realistically, and that "The pace quickened" seems like a more than slightly pat conclusion to the issue.

In Chapter 11 when the various worthies are discussing the possibility of the Machine being a Trojan Horse or some other problematic scene, we get this as the counter argument:

(view spoiler)And that's where he ends the chapter. We have to build it because not doing so would be... not good space manners.

And here's another thing: If we get a message from Vega, 26 light years away then UFOs are real. They weren't just on that star by accident. It's an observation post. They knew humanity was developing rapidly and were waiting for a signal from Earth. I would even suspect interplanetary intervention at a biological/genetic level (a la the obelisk from 2001) if we get a message from a star so near. Our galaxy is somewhere around 200,000 ly across (depending on how one delineates such things) and has 200 billion stars in it. If the Message just happens to come from a nearby star then that's a pretty universe-shattering coinkydink. If they're just 1,000 years ahead of us then they could have gone back and forth from Vega to Sol many times even using something like a tenth of light speed. No warp speed, wormholes or hyperspace needed.

I finished this yesterday but haven't had time to get my thoughts together.

I finished this yesterday but haven't had time to get my thoughts together. As usual Gary, your comments are awesome! I want to comment on almost every one of your points. I will find some time to get my ideas in order and contribute to the conversation.

Yoly wrote: "I finished this yesterday but haven't had time to get my thoughts together.

Yoly wrote: "I finished this yesterday but haven't had time to get my thoughts together. As usual Gary, your comments are awesome! I want to comment on almost every one of your points. I will find some time to get my ideas in order and contribute to the conversation."

Looking forward to it.

I'm at about the 3/4 point. (The Machine just got fired up.)

I think at this point, I've got a handle on what Sagan was doing here. It's something of a self-indulgence. That is, he's essentially spinning out a personal fantasy that is in the guise of a hard science fiction novel. That may not be entirely fair, since he does at least use real world physics and astronomy even if at certain points the technology gets advanced enough that he just kind of leaves it blank.

So a lot of my objections to the dynamics Sagan presents are there because they reflect his personal fantasy version of events. Sagan was, from my memory of his work, a guy who believed in the ultimate benevolence of more advanced civilizations, for instance, so the idea of a less than benevolent one gets short shrift. He was also very happy to talk about life, the universe and everything with theologians, and though he had a POV that he expressed, he was happy to assume good faith, if you will, when engaging with people who had X, Y, or Z (insert whatever adjectives you like) religious beliefs, or were UFO conspiracy theorists, or the simply uninformed, etc.

These days I find myself growing less and less patient with that sort of stuff. In part because I think in the last 40 years or so the pendulum has swung way, way too far on the side of the ignorati, the charlatans and the entitled villains who manipulate and oversee them. Sagan had a lot more patience with that kind of nonsense than I do, making him something of a shiny, happy McCartney ("It's gettin' better all the time!") to Hawkings as Lennon ("It can't get much worse....")

There’s so much I want to say about this book that I don’t even know where to begin.

There’s so much I want to say about this book that I don’t even know where to begin.I loved it. I keep thinking what reading this as a teenager would’ve done for me. The first parts of the novel, when Ellie was a kid, then later a young woman gave me a warm fuzzy feeling.

2. Sagan appears to me to be a pretty unabashed "alien apologist". That is, he's one of those folks who believes that a more advanced society will by definition be a more beneficent one.

I kept thinking about this. And I think this is true for most of sci fi. An alien civilization is always expected to be more advanced than us, and also it will be a more beneficent one.

Also, it’s safe to assume in sci-fi that aliens will have a hard time communicating with us because they can’t speak English, and then we turn to things like mathematics because “it is the universal language” but is it really? Mathematics is the universal language on planet Earth, but why is it safe to assume that a different civilization in a completely different planet will be able to understand our mathematics?

The president of the US being a woman was also a very nice surprise! But it would’ve been nicer to have a woman as the president of the US right now 😢 That part, in a way, made me a bit sad.

One thing I didn’t see clearly explained in the book (or maybe I just missed it because I was listening to the audio version while doing other stuff) is how much time had passed since receiving the first signal, to making the machine to actually using the machine. I think they eventually turned it on in 1999?

I have yet to read this book, but I have seen the film adaptation and am familiar with the life and work of Carl Sagan. From what I have come to learn, the story parallels his life and those of several of his colleagues very closely. It's actually really amazing to see how his fictional accounts parallels the history of SETI research and all the challenges (and challengers) it's faced.

I have yet to read this book, but I have seen the film adaptation and am familiar with the life and work of Carl Sagan. From what I have come to learn, the story parallels his life and those of several of his colleagues very closely. It's actually really amazing to see how his fictional accounts parallels the history of SETI research and all the challenges (and challengers) it's faced.

Finished last night. A few more notes:

Finished last night. A few more notes:Matthew wrote: "I have seen the film adaptation and am familiar with the life and work of Carl Sagan."

I'm going to have to watch the movie again. I saw it in the theater when it came out, but that was long enough ago that it'll be interesting to compare/contrast with a more recent reading of the book.

I remember not being terribly wild about it the first time I saw it, and mainly I think that was because of the casting. Jodie Foster is one of those actors I just don't always like to watch on screen, and it's for reasons that are hard to describe. I recall seeing an interview with Laurence Olivier in which he read off one of the critics describing his work, and the critic—rather poetically—compared watching Olivier to a clock, noting that the job of the actor was to tell the audience the time, but watching Olivier act was like looking at a clock and seeing the springs and gears tick. (He said it more romantically than that, IIRC, but that was the idea.) I find Foster like that. Even when playing a character seeped in emotional turmoil, she delivers a technical performance. In a lot of roles that works perfectly well, but in this case it contrasted weirdly with Matthew McConaughey, who is a very physical actor (his early career appears to have been based mostly on doing sit ups in pre-production...) and who hits an emotional note and sticks with it with the consistency of a medieval drone. Again, that works in a certain role/context, but my memory of the movie is that they came together like nails on a chalkboard.

Plus, the movie suffered from the standard range of Hollywood "dumb it down" studio notes, production changes, rotating directors, etc. and it ends on something of a whimper.

All of which is particularly interesting in this case because according to the Wikipedia article for the movie and the novel, Sagan began the book as a loose novelization of the film treatment that he was working on, but when that production stalled, he sold it as a book for $2 million, yet unwritten, to Simon & Schuster, a record at the time. So, if one were to ask which came first, the chicken or the egg, in this case it's kind of both.

Point being, I'm normally one of those annoying people who prefers the book to the movie, but this is one of those relatively few movies that one can't really say, "Oh, the book was better..." because the book might not have been better without a first failed attempt to make a movie. Apparently, for instance, a lot of the religious content was inspired by the interactions that Sagan had with producers and the studio. The novel wasn't written until after the production stalled and Sagan had gone through all those brainstorming meetings, and though it looks like all the studio notes, producers chiming in, actors being actors stuff happened all over again when the second effort to adapt the book came together, it seems that in this case there was a chicken then an egg and then another chicken.... (Or egg/chicken/egg, I guess, depending on how you scramble your terms in your teleological omelets.)

Yoly wrote: "Sagan appears to me to be a pretty unabashed "alien apologist". That is, he's one of those folks who believes that a more advanced society will by definition be a more beneficent one.

I kept thinking about this. And I think this is true for most of sci fi. An alien civilization is always expected to be more advanced than us, and also it will be a more beneficent one."

I wonder what the numbers would be on this if we had a database on alien portrayals in sci-fi. Advanced aliens as beneficent and idealized civilizations on one side versus aliens as rapacious invaders on the other. Off the cuff, I want to say that in prose, it's probably more the former than the latter, with the aliens being more likely to serve as a nearly angelic human analogue, and in other media they're more likely to hit us with death rays and implant their spore in our puny human brains....

That said, I think from a story telling POV, Sagan rather missed an opportunity by not raising some of the issues I mentioned, or by giving them rather short shrift. That is, there was an opportunity to build up an awful lot of tension when his characters board the Machine if there is more doubt about it, and he could have portrayed them as much more devout and brave than they wound up being. If you think about it comparatively, getting into the Machine has more risk and reward to it than strapping oneself into a capsule atop a Saturn rocket. Those astronauts knew they could set foot on the Moon... or they could wind up a fine particulate mist scattered between Florida and the upper atmosphere.

There was some tension in his portrayal of starting up the Machine, but that could have been The Right Stuff meets The Time Machine with a sprinkle of Mars Attacks!. Just one or two of the crazy civilian/semi-civilian speculators and pundits pointing out that the Message could have been the equivalent of cannibalistic alien teenagers ordering a pizza with extra humans on top could have planted that seed in the mind of the reader. He could have still laughed it off, and dismissed the idea in his narrative or dialogue, but that mindworm would have still been there in the scene, creating tension and doubt. He could have pointed out how the astronauts experienced the tension of the space program:

"I felt exactly how you would feel if you were getting ready to launch and knew you were sitting on top of two million parts -- all built by the lowest bidder on a government contract."That's an unbelievably great quote, and I'm pretty confident Sagan had heard it. He doesn't entirely ignore those issues, but he seems to shrug them off rather easily and dismissively in his novel. Philosophical debates aside, I think that was a missed opportunity from a story telling POV.

― John Glenn

I suspect one of the reasons he didn't do that, though, is that he was saving all that skepticism up for his last act in which (view spoiler) using some rather shoddy conspiracy theory level logic. That way he kept his protagonist the main character involved in the story/plot. She can investigate the messages built into (view spoiler) and I think he did that in order to keep Ellie as the POV character. The skepticism exists there so that she has to prove herself, and she has to do it more or less by herself. Still, I think some of that skepticism and tension would have been better spent earlier in the story. It would have created more tension throughout, and the sudden appearance of almost irrational denialism in the last act would have jibed better IMO.

Yoly wrote: "There’s so much I want to say about this book that I don’t even know where to begin.

Yoly wrote: "There’s so much I want to say about this book that I don’t even know where to begin.I loved it. I keep thinking what reading this as a teenager would’ve done for me. The first parts of the novel,..."

We both know the automatic assumption of the benign nature of aliens is not true. The First Peoples of the Americas made that assumption of the Europeans and we're still technically at war with the Seminoles, therefore the so-called "Indian" Wars and NOT the "War on Terror" are the longest running war the US has been involved in: 1492-?. We're still at war with the Seminoles because if you do NOT have a peace treaty, you're still engaged in hostilities. https://dos.myflorida.com/florida-fac...

And DON'T get me started on Standing Rock.

The point is that we can't really know the motivations of someone who ISN'T human because we also can't fully understand the motivations of our fellow humans.

Pastor Collins in the 1953 version of The War of the Worlds makes that assumption of the "Martians" and we ALL know what happened to him, don't we? I wish I could find a clip of his speech to his niece Sylvia on YouTube, but I can't.