The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

The Old Curiosity Shop

The Old Curiosity Shop

>

TOCS. Chapters 36 - 40

Chapter 37 takes a look at whom all the Brasses would like to take a look at but can’t – viz. at the mysterious Lodger –, and it also reintroduces us to the two puppet masters Codlin and Short. At the beginning, we learn that, to Mr. Brass’s chagrin, the Lodger has a deep interest in Punch and Judy shows and that whenever there is one of these entertainments in the vicinity, he rushes thither and brings them back with him to the house, where they have to show their act outside, with his watching from a window and afterwards withdrawing for a private conference with them. While Mr. Brass is indignant at his neighbourhood being turned into some kind of funfair, Dick revels in the Punch and Judy shows “upon the ground that looking at a Punch, or indeed looking at anything out of window, was better than working”. Interestingly, however, for all his rancour Mr. Brass never takes legal steps against the Punches haunting his premises, and our narrator gives a good explanation:

In the course of events, the Lodger also comes across our two old acquaintances Codlin and Short, and when he interviews them in his chambers, it very soon becomes clear that what he actually wants of all those diverse Punches is not so much distraction and merriment but a particular kind of information bearing on Little Nell and her Grandfather. When it turns out that finally, after all those failures, he has found the two very puppet masters he has been looking for and that furthermore, especially Mr. Codlin has always been a true and loyal friend to Little Nell, the Lodger grows restless and excited – but he will be disappointed in the end because the two men cannot really tell him anything he does not know, except that Nell was seen travelling with a waxwork company by Jerry, the dog-master. The mysterious Lodger then promises the two men a reward if they manage to bring Jerry to him so that he may question him; the feat should be an easy one, with Jerry being in London right now.

Writing this, I still smirk at Codlin’s constant attempts at presenting himself in the light of Nell’s particular friend, and his readiness to set himself over Short or at least to put the latter aside so that the limelight falls on him. I wonder how the two men are getting on when we don’t meet them. Do you think they are satisfied with their acquaintance or they are just forming some partnership of convenience, or rather of purpose?

And then there’s another thing that has me wondering: Not only does Codlin miss no opportunity of representing himself, in his own words, as Nell’s dearest bosom friend, nay even as “Father Codlin”, but there is also Dick telling to the Brasses how the mysterious gentleman never fails to call him his pillar, his confidant, his prop and what not. Then there is Mrs. Jarley, who is, we have got it in black and white, printed on posters, the particular favourite of the Royal Family, and there is the shifty landlord Jem Groves, who is also full of praise for himself. It seems to me that The Old Curiosity Shop is brimming with people who are keen on drawing a certain image of themselves to others. Might this have a particular meaning, leading us anywhere? Even if it doesn’t, it is still entertaining, especially in Dick and Codlin.

”It may, at first sight, be matter of surprise to the thoughtless few that Mr Brass, being a professional gentleman, should not have legally indicted some party or parties, active in the promotion of the nuisance, but they will be good enough to remember, that as Doctors seldom take their own prescriptions, and Divines do not always practise what they preach, so lawyers are shy of meddling with the Law on their own account: knowing it to be an edged tool of uncertain application, very expensive in the working, and rather remarkable for its properties of close shaving, than for its always shaving the right person.”

In the course of events, the Lodger also comes across our two old acquaintances Codlin and Short, and when he interviews them in his chambers, it very soon becomes clear that what he actually wants of all those diverse Punches is not so much distraction and merriment but a particular kind of information bearing on Little Nell and her Grandfather. When it turns out that finally, after all those failures, he has found the two very puppet masters he has been looking for and that furthermore, especially Mr. Codlin has always been a true and loyal friend to Little Nell, the Lodger grows restless and excited – but he will be disappointed in the end because the two men cannot really tell him anything he does not know, except that Nell was seen travelling with a waxwork company by Jerry, the dog-master. The mysterious Lodger then promises the two men a reward if they manage to bring Jerry to him so that he may question him; the feat should be an easy one, with Jerry being in London right now.

Writing this, I still smirk at Codlin’s constant attempts at presenting himself in the light of Nell’s particular friend, and his readiness to set himself over Short or at least to put the latter aside so that the limelight falls on him. I wonder how the two men are getting on when we don’t meet them. Do you think they are satisfied with their acquaintance or they are just forming some partnership of convenience, or rather of purpose?

And then there’s another thing that has me wondering: Not only does Codlin miss no opportunity of representing himself, in his own words, as Nell’s dearest bosom friend, nay even as “Father Codlin”, but there is also Dick telling to the Brasses how the mysterious gentleman never fails to call him his pillar, his confidant, his prop and what not. Then there is Mrs. Jarley, who is, we have got it in black and white, printed on posters, the particular favourite of the Royal Family, and there is the shifty landlord Jem Groves, who is also full of praise for himself. It seems to me that The Old Curiosity Shop is brimming with people who are keen on drawing a certain image of themselves to others. Might this have a particular meaning, leading us anywhere? Even if it doesn’t, it is still entertaining, especially in Dick and Codlin.

Chapter 38 treats us to a change of scene, promising “to call upon us imperatively to pursue the track we most desire to take”, by showing us again how Kit is faring. What do you think Dickens himself preferred to write about when working on this novel: Was he interested most in the travels of Nell and her obnoxious Grandfather? Did he sympathize most with Kit, whom he really made from a comic relief clown into a good-hearted and determined young man? Or was he especially intrigued with Dick, our man of poetry and imagination? Maybe, Dickens also had a soft spot for Quilp, endowing him with all sorts of miraculous faculties, like that of showing up wherever and whenever he wants? I wonder how Dickens could have known that I as a reader am rooting for Kit and wish his prospects to prove solid and undeceiving – also for the sake of the little family.

Kit has grown more and more familiar with the household at Finchley, although his heart is still back in London with his mother and his siblings, and he has rendered himself useful and nearly indispensable. There is no one but he who can deal with the pony on any footing nearing equality – it “is true that in exact proportion as he [i.e. the pony] became manageable by Kit he became utterly ungovernable by anyone else” –, and Kit’s admiration of that self-willed animal leads him into representing all the pony’s antics as signs of its affection for the family. One day when Kit is taking Mr. Abel to the Notary’s office, he is asked – by an ever-condescending Mr. Chuckster – to step inside for he is wanted there. Entering, he is faced with “an elderly gentleman, but of a stout, bluff figure”, who has been talking with Mr. Witherden. The old man opens his interview with Kit in the following words:

If the stout and bluff figure had not already given him away to the careful reader, these words might have done the trick at the very latest: We are, again, faced with the single gentleman who has taken lodgings at Bevis Mark and who has been grilling the Punches. One might wonder in what connection he stands to Nell and the Grandfather, and why he calls himself “a stranger to this country […] for many years”. Did he travel? Did he do business abroad, like in the colonies? Or was his business like that of Mr. Magwitch? Be that as it may, he shows a liking for unpolished honesty, or at least quite a disregard for English manners when he rebuffs Mr. Witherden for his businesslike flatteries of his potential client by saying

Maybe, one could see this as a parallel: On the one hand, we have Mr. Witherden, whose client does not wish him to pay him the usual flatteries, on the other, there is Sampson Brass, whose oily flatteries are taken by Quilp as his due.

When he turns back to Kit in order to get more information out of him, he tells the young man that he is solely motivated by the wish “of serving and reclaiming those I am in search of”. In the following conversation Kit tells the single gentleman everything he knows about Nell and her Grandfather’s life, their secret departure and Quilp’s role in the whole affair. We also learn how the single gentleman has come to take up lodgings at Mr. Brass’s, namely by a board on the door of the closed curiosity shop that referred all inquirers to that eminent attorney. In that context, we have the following amusing exchange of words between Mr. Witherden, who is shocked to find out where the single gentleman resides, and the single gentleman himself, who appears to know very well what he is doing:

Kit obtains the permission to tell his mother about this interview but is admonished to let nobody else know. However, when he leaves the Notary’s house together with the single gentleman, he is seen by Dick Swiveller, who happens to drop by because Mr. Chuckster is one of the members of the Lodge of Glorious Appolos of which Mr. Swiveller is a Perpetual Grand. This is one of the famous coincidences occurring in Dickens’s novels, and after the narrator has just cleared out one coincidence – by explaining how Mr. Brass got his lodger –, one may be generous and grant the narrative this new coincidence as a way of stringing some subplots together.

Dick loses no time but engages in a conversation with Kit, and in order to intensify their relation he offers to buy him a glass of beer – an offer that Kit is somewhat reluctant to accept. Why is Kit’s reluctance mentioned here? In their following conversation you can see how Dick tries in at least two ways to worm the information as to the stranger’s identity out of Kit: He both tries to catch Kit at unawares, e.g. when he drinks to the stranger’s health and makes as though the name had slipped him, and he also plays on Kit’s love for his family and his desire to support them and ensure their survival in good circumstances when he intimates that the stranger, who is “’a liberal sort of fellow’” must be got to do something for Kit’s mother, and that therefore it would be good to bring the two together.

What does this manner of leading the conversation – although, eventually, it proves to be in vain – tell us about Dick Swiveller? And what do you think about his emptying the remnants of the beer onto the floor in front of the little boy who serves the guests? Is that not quite nasty? I wonder what direction Swiveller – always true to his name – will finally head for.

Kit has grown more and more familiar with the household at Finchley, although his heart is still back in London with his mother and his siblings, and he has rendered himself useful and nearly indispensable. There is no one but he who can deal with the pony on any footing nearing equality – it “is true that in exact proportion as he [i.e. the pony] became manageable by Kit he became utterly ungovernable by anyone else” –, and Kit’s admiration of that self-willed animal leads him into representing all the pony’s antics as signs of its affection for the family. One day when Kit is taking Mr. Abel to the Notary’s office, he is asked – by an ever-condescending Mr. Chuckster – to step inside for he is wanted there. Entering, he is faced with “an elderly gentleman, but of a stout, bluff figure”, who has been talking with Mr. Witherden. The old man opens his interview with Kit in the following words:

”’My business is no secret; or I should rather say it need be no secret here,'’said the stranger, observing that Mr Abel and the Notary were preparing to retire. ‘It relates to a dealer in curiosities with whom he lived, and in whom I am earnestly and warmly interested. I have been a stranger to this country, gentlemen, for very many years, and if I am deficient in form and ceremony, I hope you will forgive me.’”

If the stout and bluff figure had not already given him away to the careful reader, these words might have done the trick at the very latest: We are, again, faced with the single gentleman who has taken lodgings at Bevis Mark and who has been grilling the Punches. One might wonder in what connection he stands to Nell and the Grandfather, and why he calls himself “a stranger to this country […] for many years”. Did he travel? Did he do business abroad, like in the colonies? Or was his business like that of Mr. Magwitch? Be that as it may, he shows a liking for unpolished honesty, or at least quite a disregard for English manners when he rebuffs Mr. Witherden for his businesslike flatteries of his potential client by saying

”’Sir […], you speak like a mere man of the world, and I think you something better. Therefore, pray do not sink your real character in paying unmeaning compliments to me.’”

Maybe, one could see this as a parallel: On the one hand, we have Mr. Witherden, whose client does not wish him to pay him the usual flatteries, on the other, there is Sampson Brass, whose oily flatteries are taken by Quilp as his due.

When he turns back to Kit in order to get more information out of him, he tells the young man that he is solely motivated by the wish “of serving and reclaiming those I am in search of”. In the following conversation Kit tells the single gentleman everything he knows about Nell and her Grandfather’s life, their secret departure and Quilp’s role in the whole affair. We also learn how the single gentleman has come to take up lodgings at Mr. Brass’s, namely by a board on the door of the closed curiosity shop that referred all inquirers to that eminent attorney. In that context, we have the following amusing exchange of words between Mr. Witherden, who is shocked to find out where the single gentleman resides, and the single gentleman himself, who appears to know very well what he is doing:

”’[…] Yes, I live at Brass’s – more shame for me, I suppose?’

‘That’s a mere matter of opinion,’ said the Notary, shrugging his shoulders. ‘He is looked upon as rather a doubtful character.’

‘Doubtful?’ echoed the other. ‘I am glad to hear there’s any doubt about it. I supposed that had been thoroughly settled, long ago. […]’”

Kit obtains the permission to tell his mother about this interview but is admonished to let nobody else know. However, when he leaves the Notary’s house together with the single gentleman, he is seen by Dick Swiveller, who happens to drop by because Mr. Chuckster is one of the members of the Lodge of Glorious Appolos of which Mr. Swiveller is a Perpetual Grand. This is one of the famous coincidences occurring in Dickens’s novels, and after the narrator has just cleared out one coincidence – by explaining how Mr. Brass got his lodger –, one may be generous and grant the narrative this new coincidence as a way of stringing some subplots together.

Dick loses no time but engages in a conversation with Kit, and in order to intensify their relation he offers to buy him a glass of beer – an offer that Kit is somewhat reluctant to accept. Why is Kit’s reluctance mentioned here? In their following conversation you can see how Dick tries in at least two ways to worm the information as to the stranger’s identity out of Kit: He both tries to catch Kit at unawares, e.g. when he drinks to the stranger’s health and makes as though the name had slipped him, and he also plays on Kit’s love for his family and his desire to support them and ensure their survival in good circumstances when he intimates that the stranger, who is “’a liberal sort of fellow’” must be got to do something for Kit’s mother, and that therefore it would be good to bring the two together.

What does this manner of leading the conversation – although, eventually, it proves to be in vain – tell us about Dick Swiveller? And what do you think about his emptying the remnants of the beer onto the floor in front of the little boy who serves the guests? Is that not quite nasty? I wonder what direction Swiveller – always true to his name – will finally head for.

The following chapter does not add a lot to our story in terms of plot development but it is interesting with regard to Kit and Barbara and their relationship. We can also witness Dickens’s mastery at describing delightful situations – here Kit’s first quarter day, and his night at Astley’s and the ensuing meal of oysters at a restaurant together with his mother and brothers and with Barbara and her mother – in a way to intrigue and amuse his readers. Of course, just having read the Sketches, we Curiosities know well how Dickens achieves scenes like these.

Let me just point out that Kit, for all his gentleness, sometimes behaves in a rather clumsy way, as when he extols on the “extraordinary beauty of Nell” and is taken aback when he notices that “the last-named circumstance failed to interest his hearers to anything like the extent he had supposed”. Kit’s mother points out “that there was no doubt Miss Nell was very pretty, but she was but a child after all, and there were many young women quite as pretty as she”.

Here we are again faced with the question whether Nell is more like a young woman or like a child at 14 years of age. Barbara cannot be but two years older, I should say. The motif of Kit’s unwittingly slighting and hurting Barbara is pursued through the whole chapter, and while on the one hand, one might feel sorry for the stick the young woman has to put up with, on the other hand, it is also funny to see Kit’s lack of perception, e.g. when he includes Barbara’s mother in a compliment he has paid her a few seconds before. Common sense should tell him that no young woman takes kindly to being told that she looks a great deal better than a certain actress, and that so does her mother. Ouch, Kit, ouch!!!

All in all, what does this chapter tell us about Kit’s development in the novel? In which respects has he changed, in which has he remained constant? And do you think that Barbara will put up with Kit’s praise of Nell’s beauty and innocence for long? Wouldn’t it be nice if Kit noticed that Barbara is much better for him than Nell – or what do you think?

Let me just point out that Kit, for all his gentleness, sometimes behaves in a rather clumsy way, as when he extols on the “extraordinary beauty of Nell” and is taken aback when he notices that “the last-named circumstance failed to interest his hearers to anything like the extent he had supposed”. Kit’s mother points out “that there was no doubt Miss Nell was very pretty, but she was but a child after all, and there were many young women quite as pretty as she”.

Here we are again faced with the question whether Nell is more like a young woman or like a child at 14 years of age. Barbara cannot be but two years older, I should say. The motif of Kit’s unwittingly slighting and hurting Barbara is pursued through the whole chapter, and while on the one hand, one might feel sorry for the stick the young woman has to put up with, on the other hand, it is also funny to see Kit’s lack of perception, e.g. when he includes Barbara’s mother in a compliment he has paid her a few seconds before. Common sense should tell him that no young woman takes kindly to being told that she looks a great deal better than a certain actress, and that so does her mother. Ouch, Kit, ouch!!!

All in all, what does this chapter tell us about Kit’s development in the novel? In which respects has he changed, in which has he remained constant? And do you think that Barbara will put up with Kit’s praise of Nell’s beauty and innocence for long? Wouldn’t it be nice if Kit noticed that Barbara is much better for him than Nell – or what do you think?

After the easy-going pace of the previous chapter, Chapter 40 once more puts the story in top-gear. Our narrator shows himself as a close observer of human nature when he points out that on the next morning, Kit wakes up in a slightly miserable shape, “with a heart something heavier than his pockets”. This is due to the fact that Kit experiences what is so typical of most of us – the inexplicable feeling of regret and dispiritedness after a holiday. It has to be noted, however, that Kit is well aware that the pleasures they indulged in were harmless and honest enough, and he is such a responsible son that he can put a lot of money on the table for his family before leaving, i.e. he did not squander all the money, as Mr. Swiveller would doubtless have done.

Soon, Kit and Barbara – who is, of course, very quiet – arrive at their employers’ house, and they enter into their duties as though they had never been away. Kit’s business soon calls him into the garden where he has to prune a tree – or do something similar – while Mr. Garland is doing something else. During their work, Mr. Garland mentions the single gentleman again, as well as his intention to employ Kit in his own services. Hearing this, Kit would nearly have fallen from his ladder, but he manages to keep his balance, and he points out that there is no way he would ever leave his present situation as long as he is wanted there. Mr. Garland duly points out to him that the stranger gentleman will definitely be able to pay him better wages, but even this does not make any strong impression on Kit. The only thing that somewhat affects him is Mr. Garland’s hint that Kit ws a very faithful servant to his old employer and that, obviously, the strange gentleman has the intention to find out about and bring back the old man and his granddaughter, which would also gratify Kit. After some momentary pangs, Kit returns to his initial attitude, saying

Saying this, Kit adds that if Nell came back and wanted his services, this would be quite another matter, but even then his time would be divided between the Garlands and Nell. Apart from that, Kit adds, Nell will probably return a wealthy young lady and stand no longer in need of him and his services. – His then hammering a nail into the wall, and his doing it “much harder than was necessary”, might tell something about his feelings for Little Nell. What does the Morse code betray?

Enter Mr. Chuckster now, and with him his usual arrogance towards Kit, but also towards the countryside and all those who dwell in it in general. Mr. Chuckster has come because once again Kit is wanted at his office, but since his horse needs some time to recover, the young clerk gracefully accepts the hospitality of the Garlands, entertaining them with the latest town gossip and proving that a man like he is quite enough to carry on a good conversation single-handedly.

By the way, what do you think about Mr. Chuckster’s monologue? Is it just a filler, or is it meant to show something with regard to the opposition between city life and rural life that has been established in the past few chapters? Remember that Kit had a half-holiday, which he spent with his family, indulging in typical city entertainments, and that he now has returned to gardening, a very useful, but also healthy and sometimes – depending on your speed and ambition – contemplative activity. Can Kit’s unwillingness to leave the Garland sphere for the single gentleman also have something to do with the city-countryside opposition? How do Nell and her Grandfather’s travels fit into this picture?

When Kit is eventually taken to the office by Mr. Chuckster, he, of course, finds the single gentleman there in Mr. Witherden’s company, and he is told that he has found out the whereabouts of Little Nell and her Grandfather through the help of Jerry, the dog-master. Now Kit’s help is needed because the single gentleman is well aware that he cannot simply face Nell and the old man without running the risk of scaring them off, and so he has come to the conclusion that a familiar face like that of Kit would inspire the two waifs with confidence and induce them to give up their odyssey and return home. Although Kim is delighted at this news, he soon has to realize that he cannot be of any virtual use in this quest because of the estrangement occurring between the old man and himself. Some deliberation, however, makes him come up with the idea of his mother’s being the person the single gentleman needs, since she is familiar with Nell and her Grandfather and, unlike him, not anathematized. Kit promises that in two hours’ time, his mother will be at the single gentleman’s beck and call.

Do you think the single gentleman’s mission will be successful? Apart from that, did it strike you as odd with what kind of matter-of-factness Kit and the other people at the office disposed of his mother’s time? Who will take care of the children in the meantime?

We can witness how the narrator has started linking the different strands of the story again: The story around Kit is going to be joined again with that of Little Nell, or at least, there is some chance of this coming to pass. Via the single gentleman, Brass (and Quilp) also come into play – might it not be possible that it will be the single gentleman himself that is going to deliver some cue to Quilp as to where Nell can be found? I just wonder how the single gentleman was led to turn to Mr. Witherden for help, there being no immediate connection between Witherden and the single gentleman, neither between that latter and the Garlands. Do you see any hint in the text that I have overlooked?

Soon, Kit and Barbara – who is, of course, very quiet – arrive at their employers’ house, and they enter into their duties as though they had never been away. Kit’s business soon calls him into the garden where he has to prune a tree – or do something similar – while Mr. Garland is doing something else. During their work, Mr. Garland mentions the single gentleman again, as well as his intention to employ Kit in his own services. Hearing this, Kit would nearly have fallen from his ladder, but he manages to keep his balance, and he points out that there is no way he would ever leave his present situation as long as he is wanted there. Mr. Garland duly points out to him that the stranger gentleman will definitely be able to pay him better wages, but even this does not make any strong impression on Kit. The only thing that somewhat affects him is Mr. Garland’s hint that Kit ws a very faithful servant to his old employer and that, obviously, the strange gentleman has the intention to find out about and bring back the old man and his granddaughter, which would also gratify Kit. After some momentary pangs, Kit returns to his initial attitude, saying

”’[…] why should I care for his thinking, sir, when I know that I should be a fool, and worse than a fool, sir, to leave the kindest master and mistress that ever was or can be, who took me out of the streets a very poor and hungry lad indeed – poorer and hungrier perhaps than even you think for, sir […]’”

Saying this, Kit adds that if Nell came back and wanted his services, this would be quite another matter, but even then his time would be divided between the Garlands and Nell. Apart from that, Kit adds, Nell will probably return a wealthy young lady and stand no longer in need of him and his services. – His then hammering a nail into the wall, and his doing it “much harder than was necessary”, might tell something about his feelings for Little Nell. What does the Morse code betray?

Enter Mr. Chuckster now, and with him his usual arrogance towards Kit, but also towards the countryside and all those who dwell in it in general. Mr. Chuckster has come because once again Kit is wanted at his office, but since his horse needs some time to recover, the young clerk gracefully accepts the hospitality of the Garlands, entertaining them with the latest town gossip and proving that a man like he is quite enough to carry on a good conversation single-handedly.

By the way, what do you think about Mr. Chuckster’s monologue? Is it just a filler, or is it meant to show something with regard to the opposition between city life and rural life that has been established in the past few chapters? Remember that Kit had a half-holiday, which he spent with his family, indulging in typical city entertainments, and that he now has returned to gardening, a very useful, but also healthy and sometimes – depending on your speed and ambition – contemplative activity. Can Kit’s unwillingness to leave the Garland sphere for the single gentleman also have something to do with the city-countryside opposition? How do Nell and her Grandfather’s travels fit into this picture?

When Kit is eventually taken to the office by Mr. Chuckster, he, of course, finds the single gentleman there in Mr. Witherden’s company, and he is told that he has found out the whereabouts of Little Nell and her Grandfather through the help of Jerry, the dog-master. Now Kit’s help is needed because the single gentleman is well aware that he cannot simply face Nell and the old man without running the risk of scaring them off, and so he has come to the conclusion that a familiar face like that of Kit would inspire the two waifs with confidence and induce them to give up their odyssey and return home. Although Kim is delighted at this news, he soon has to realize that he cannot be of any virtual use in this quest because of the estrangement occurring between the old man and himself. Some deliberation, however, makes him come up with the idea of his mother’s being the person the single gentleman needs, since she is familiar with Nell and her Grandfather and, unlike him, not anathematized. Kit promises that in two hours’ time, his mother will be at the single gentleman’s beck and call.

Do you think the single gentleman’s mission will be successful? Apart from that, did it strike you as odd with what kind of matter-of-factness Kit and the other people at the office disposed of his mother’s time? Who will take care of the children in the meantime?

We can witness how the narrator has started linking the different strands of the story again: The story around Kit is going to be joined again with that of Little Nell, or at least, there is some chance of this coming to pass. Via the single gentleman, Brass (and Quilp) also come into play – might it not be possible that it will be the single gentleman himself that is going to deliver some cue to Quilp as to where Nell can be found? I just wonder how the single gentleman was led to turn to Mr. Witherden for help, there being no immediate connection between Witherden and the single gentleman, neither between that latter and the Garlands. Do you see any hint in the text that I have overlooked?

Tristram wrote: "Apart from that, did it strike you as odd with what kind of matter-of-factness Kit and the other people at the office disposed of his mother’s time? Who will take care of the children in the meantime?"

Tristram wrote: "Apart from that, did it strike you as odd with what kind of matter-of-factness Kit and the other people at the office disposed of his mother’s time? Who will take care of the children in the meantime?"I did find myself wondering if the kids were coming too.

There are so many mysterious loose ends hanging now. I guess I'm betting on the Strange Lodger being Nell's dad, who so far has not even been mentioned, but surely she must have one. And that would help explain why Grandfather is so worried about being followed all the time. I had been thinking loan sharks, but now I don't know.

He could also be a lawyer in charge of the Vast Fortune that Nell is supposed to be entitled to, although this is a less interesting read and Grandfather's gambling addiction seems to be a more realistic reason for the Vast Fortune talk. But when did realism really have all that much to do with the concluding plot moves in an early Dickens novel?

I do like the little girl and it is a colossal disappointment to me to see Sally Brass revealed as a truly awful person, regardless of whether she is this out of career frustration. I was all ready to root for her, even against Dickens's implicit intentions, as a thwarted career gal who could nonetheless come to appreciate a good outing with Dick Swiveller, but no sense of shame can excuse the way she treats the girl in the basement.

Also maybe it's just getting away from Grandfather and Quilp and traveling entertainers for a while, but I'm enjoying this book a lot now and am glad I made it past the first few chapters this time.

Also maybe it's just getting away from Grandfather and Quilp and traveling entertainers for a while, but I'm enjoying this book a lot now and am glad I made it past the first few chapters this time.

Tristram wrote: "Apparently, Sally has an inveterate hate of that poor, unoffending girl – and when we remember that her brother implied to Dick that the servant is, maybe, “a love-child”, this may enable us to put A and B, or maybe S.B. and Q. together … Or am I getting carried away on a wild goose chase here? ..."

Tristram wrote: "Apparently, Sally has an inveterate hate of that poor, unoffending girl – and when we remember that her brother implied to Dick that the servant is, maybe, “a love-child”, this may enable us to put A and B, or maybe S.B. and Q. together … Or am I getting carried away on a wild goose chase here? ..."An awful lot was made of the girl's diminutive size, and I don't believe that's a coincidence. And Dickens has established that the Brasses will employ people at Quilp's behest. But as a mother, I can't bring myself to suspect that Sally might be so cruel to her own child. So if Quilp is her father, who might her mother be? I hope that Dick will be her knight in shining armor.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 37 takes a look at whom all the Brasses would like to take a look at but can’t – viz. at the mysterious Lodger ..."

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 37 takes a look at whom all the Brasses would like to take a look at but can’t – viz. at the mysterious Lodger ..."Can we trust the Lodger? Is he there to do the Trents harm or will he be a benefactor? Mr. Garland, Kit, et al, seem to trust him, so I believe we're meant to, as well. But why should we? I'm withholding judgment for the time being.

Tristram wrote: "The following chapter does not add a lot to our story in terms of plot development..."

Tristram wrote: "The following chapter does not add a lot to our story in terms of plot development..."Maybe not much plot development, but certainly my favorite chapter in the book so far. Oh, how I laughed! Sinister antagonists and orphaned waifs are all very well and good, but THIS is why I love Dickens. "Poor Barbara!"

Mary Lou wrote: "But as a mother, I can't bring myself to suspect that Sally might be so cruel to her own child. So if Quilp is her father, who might her mother be?"

But imagine Sally Brass was pregnant without wanting a child, and Quilp would not or could not marry her - how long has he been married with his actual wife, by the way? If Sally had to give birth to an unwanted child, and if she was left alone with the situation, all her frustration and anger might possibly unload themselves on the child. Her returning to the little servant in order to give her some blows seems so strange and cranky to me that I can easily believe that Sally has a deeply ingrained personal grudge against the poor little girl.

And then, do you remember Quilp saying, with reference to Sally, "This is the woman I should have married!"? On the surface, this is flattery, cheap flattery, but still flattery. But if we see the little servant as Quilp and Sally's illegitimate child, then this seemingly harmless sentence is a very cruel mockery, and I am sure Quilp would enjoy this kind of mockery heartily.

But imagine Sally Brass was pregnant without wanting a child, and Quilp would not or could not marry her - how long has he been married with his actual wife, by the way? If Sally had to give birth to an unwanted child, and if she was left alone with the situation, all her frustration and anger might possibly unload themselves on the child. Her returning to the little servant in order to give her some blows seems so strange and cranky to me that I can easily believe that Sally has a deeply ingrained personal grudge against the poor little girl.

And then, do you remember Quilp saying, with reference to Sally, "This is the woman I should have married!"? On the surface, this is flattery, cheap flattery, but still flattery. But if we see the little servant as Quilp and Sally's illegitimate child, then this seemingly harmless sentence is a very cruel mockery, and I am sure Quilp would enjoy this kind of mockery heartily.

Tristram wrote: "But imagine Sally Brass was pr..."

Tristram wrote: "But imagine Sally Brass was pr..."Your suppositions are compelling, Tristram, and probably correct. And I know that some people are horrible, but I just can't bring myself to believe it until the truth comes to light.

I'm shocked that Sally was so cruel to the servant girl. It's possible the girl is her unwanted child. What I don't get is why she would have an affair with Quilp! He sure goes after the ladies, doesn't he?

I'm shocked that Sally was so cruel to the servant girl. It's possible the girl is her unwanted child. What I don't get is why she would have an affair with Quilp! He sure goes after the ladies, doesn't he?Tristram wrote: "And then, do you remember Quilp saying, with reference to Sally, "This is the woman I should have married!"? On the surface, this is flattery, cheap flattery, but still flattery. But if we see the little servant as Quilp and Sally's illegitimate child, then this seemingly harmless sentence is a very cruel mockery."

It's certainly possible, and within Quilp's character, that he was mocking her. He called Sally, "virgin," too, another sarcastic dig.

I like that Dick is playing detective and trying to find the truth.

How interesting that Codlin and Short are back! I thought they were just a vignette, and we'd never see them again. I love how Dickens ties the characters together in unexpected ways. It reminds me of theater somehow.

How interesting that Codlin and Short are back! I thought they were just a vignette, and we'd never see them again. I love how Dickens ties the characters together in unexpected ways. It reminds me of theater somehow.The single gentleman is very mysterious. He knows Nell and Grandpa, but I don't know who he could be. Hopefully, he's one of the good guys.

Tristram wrote: "Hello Curiosities,

This week we will not meet Little Nell and her Grandfather, which will guarantee you relatively grumpiness-free recaps from my side! Since we are now experiencing the advent of ..."

I am very happy to see the question of the background of the little servant of the Brass household introduced. I too see her as, very probably, the love child of Sally Brass and Quilp. We know that Quilp has a lustful nature. We know that there is a long-standing connection between the Brass’s and Quilp. In terms of ethics, I doubt if it matters much if Sally was pregnant before or after Quilp’s marriage. As to Sally’s own treatment of the little maid, I can fully believe that Sally’s resentment towards her own child is probable.

Yes, the decent into the basement of their home is a perfect setting to continue our fractured fairy tale trope. That the little servant is not allowed out of the house and dwells beneath the surface of the street intensifies the nature of her existence.

What will future chapters reveal?

This week we will not meet Little Nell and her Grandfather, which will guarantee you relatively grumpiness-free recaps from my side! Since we are now experiencing the advent of ..."

I am very happy to see the question of the background of the little servant of the Brass household introduced. I too see her as, very probably, the love child of Sally Brass and Quilp. We know that Quilp has a lustful nature. We know that there is a long-standing connection between the Brass’s and Quilp. In terms of ethics, I doubt if it matters much if Sally was pregnant before or after Quilp’s marriage. As to Sally’s own treatment of the little maid, I can fully believe that Sally’s resentment towards her own child is probable.

Yes, the decent into the basement of their home is a perfect setting to continue our fractured fairy tale trope. That the little servant is not allowed out of the house and dwells beneath the surface of the street intensifies the nature of her existence.

What will future chapters reveal?

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 37 takes a look at whom all the Brasses would like to take a look at but can’t – viz. at the mysterious Lodger –, and it also reintroduces us to the two puppet masters Codlin and Short. At ..."

The re-introduction of Codlin and Short is delightful. The fact that the mysterious lodger of the Brasses is in search of information about Nell and her grandfather establishes the point of the plot where Dickens begins to draw the often seemingly unconnected parts of the story together.

By bringing Codlin and Short into Bevis Marks we also see how the world of the itinerant country travellers and those who create fantasy begins to intersect with the harsh business reality of the city. The segregation of these two settings is now being merged. It is the mysterious gentleman who is the bridge between the two. Who is he and what is his purpose?

The re-introduction of Codlin and Short is delightful. The fact that the mysterious lodger of the Brasses is in search of information about Nell and her grandfather establishes the point of the plot where Dickens begins to draw the often seemingly unconnected parts of the story together.

By bringing Codlin and Short into Bevis Marks we also see how the world of the itinerant country travellers and those who create fantasy begins to intersect with the harsh business reality of the city. The segregation of these two settings is now being merged. It is the mysterious gentleman who is the bridge between the two. Who is he and what is his purpose?

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 38 treats us to a change of scene, promising “to call upon us imperatively to pursue the track we most desire to take”, by showing us again how Kit is faring. What do you think Dickens hims..."

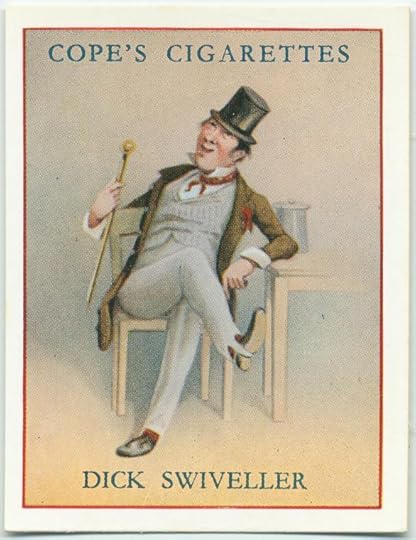

Kit and Swiveller together. Kit represents all that is good. He is an honest, hard-working, family-loving and faithful son. On the other hand, Swiveller is rather debauched, sarcastic, edgy and enjoys a couple (or more) drinks on every occasion. Still, Dickens manages to make both equally enduring. While Dick is obviously questioning Kit for his own advantage, I can’t help but see Dick as firmly planted on the side of the good characters. Because Dick is part of the Brass’s organization, and thus directly connected to Quilp, it means Dick is both an insider with the forces of disharmony and allied with the forces of good in the novel. A very clever character creation by Dickens.

Kit and Swiveller together. Kit represents all that is good. He is an honest, hard-working, family-loving and faithful son. On the other hand, Swiveller is rather debauched, sarcastic, edgy and enjoys a couple (or more) drinks on every occasion. Still, Dickens manages to make both equally enduring. While Dick is obviously questioning Kit for his own advantage, I can’t help but see Dick as firmly planted on the side of the good characters. Because Dick is part of the Brass’s organization, and thus directly connected to Quilp, it means Dick is both an insider with the forces of disharmony and allied with the forces of good in the novel. A very clever character creation by Dickens.

Alissa wrote: "I'm shocked that Sally was so cruel to the servant girl. It's possible the girl is her unwanted child. What I don't get is why she would have an affair with Quilp! He sure goes after the ladies, do..."

Hmm, I don't know if Sally Brass goes after the ladies, there being no ladies in the vicinity so far. It's difficult to picture her having an affair with Quilp, but it is even more difficult for me to think of reasons why a delicate woman like Mrs Quilp née Jiniwin should have tied herself in marriage to ugly and evil Quilp -- unless there were any base machinations of her own parents at work, as we surmised in a previous threat.

Compared to that unequal union, it is indeed easier to picture the rough Sally fall in with Quilp for the sole purpose of ... you know.

Hmm, I don't know if Sally Brass goes after the ladies, there being no ladies in the vicinity so far. It's difficult to picture her having an affair with Quilp, but it is even more difficult for me to think of reasons why a delicate woman like Mrs Quilp née Jiniwin should have tied herself in marriage to ugly and evil Quilp -- unless there were any base machinations of her own parents at work, as we surmised in a previous threat.

Compared to that unequal union, it is indeed easier to picture the rough Sally fall in with Quilp for the sole purpose of ... you know.

Alissa wrote: "How interesting that Codlin and Short are back! I thought they were just a vignette, and we'd never see them again. I love how Dickens ties the characters together in unexpected ways. It reminds me..."

I, too, was very delighted to see those two puppet masters again, especially Mr. Codlin because a friend of Nell's is a friend of mine :-)

I, too, was very delighted to see those two puppet masters again, especially Mr. Codlin because a friend of Nell's is a friend of mine :-)

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 38 treats us to a change of scene, promising “to call upon us imperatively to pursue the track we most desire to take”, by showing us again how Kit is faring. What do you t..."

Yes, Peter, Dick is surely a very interesting character, although I suspect that it wasn't originally Dickens's intention to present him as such an ambiguous and two-sided character, whom we now inadvertantly find ourselves somehow rooting for. This change is probably due to the fact that TOCS became something different than Dickens had planned it to be when he started the story. We have already discussed Nell's varying age, the fading-away of the first person narrator and, apparently, of Fred Trent, and the very unlikely change of Kit, who starts as a half-wit and becomes more and more of a responsible, clear-sighted young gentleman. He has even learned how to write and read letters, although it was previously quite a feat for him to write a single letter.

Dick's change, however, is quite believable, and more subtle. At first, he was little more than Fred's tool, but when he is thrown into the world, he is becoming cleverer and cleverer.

Yes, Peter, Dick is surely a very interesting character, although I suspect that it wasn't originally Dickens's intention to present him as such an ambiguous and two-sided character, whom we now inadvertantly find ourselves somehow rooting for. This change is probably due to the fact that TOCS became something different than Dickens had planned it to be when he started the story. We have already discussed Nell's varying age, the fading-away of the first person narrator and, apparently, of Fred Trent, and the very unlikely change of Kit, who starts as a half-wit and becomes more and more of a responsible, clear-sighted young gentleman. He has even learned how to write and read letters, although it was previously quite a feat for him to write a single letter.

Dick's change, however, is quite believable, and more subtle. At first, he was little more than Fred's tool, but when he is thrown into the world, he is becoming cleverer and cleverer.

Tristram wrote: "Compared to that unequal union, it is indeed easier to picture the rough Sally fall in with Quilp for the sole purpose of ... you know."

Well thanks for putting a picture of Sally and Quilp both naked and in the same bed in my head.

Well thanks for putting a picture of Sally and Quilp both naked and in the same bed in my head.

We talk about little Nell's age and I would love to talk about the little servant's age, but I can't. Not until the last chapter anyway.

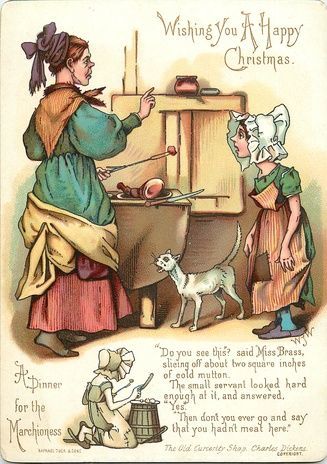

The Small Servant's Dinner

Chapter 36

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Now,’ said Dick, walking up and down with his hands in his pockets, ‘I’d give something—if I had it—to know how they use that child, and where they keep her. My mother must have been a very inquisitive woman; I have no doubt I’m marked with a note of interrogation somewhere. My feelings I smother, but thou hast been the cause of this anguish, my—upon my word,’ said Mr Swiveller, checking himself and falling thoughtfully into the client’s chair, ‘I should like to know how they use her!’

After running on, in this way, for some time, Mr Swiveller softly opened the office door, with the intention of darting across the street for a glass of the mild porter. At that moment he caught a parting glimpse of the brown head-dress of Miss Brass flitting down the kitchen stairs. ‘And by Jove!’ thought Dick, ‘she’s going to feed the small servant. Now or never!’

First peeping over the handrail and allowing the head-dress to disappear in the darkness below, he groped his way down, and arrived at the door of a back kitchen immediately after Miss Brass had entered the same, bearing in her hand a cold leg of mutton. It was a very dark miserable place, very low and very damp: the walls disfigured by a thousand rents and blotches. The water was trickling out of a leaky butt, and a most wretched cat was lapping up the drops with the sickly eagerness of starvation. The grate, which was a wide one, was wound and screwed up tight, so as to hold no more than a little thin sandwich of fire. Everything was locked up; the coal-cellar, the candle-box, the salt-box, the meat-safe, were all padlocked.

There was nothing that a beetle could have lunched upon. The pinched and meagre aspect of the place would have killed a chameleon. He would have known, at the first mouthful, that the air was not eatable, and must have given up the ghost in despair. The small servant stood with humility in presence of Miss Sally, and hung her head.

‘Are you there?’ said Miss Sally.

‘Yes, ma’am,’ was the answer in a weak voice.

‘Go further away from the leg of mutton, or you’ll be picking it, I know,’ said Miss Sally.

The girl withdrew into a corner, while Miss Brass took a key from her pocket, and opening the safe, brought from it a dreary waste of cold potatoes, looking as eatable as Stonehenge. This she placed before the small servant, ordering her to sit down before it, and then, taking up a great carving-knife, made a mighty show of sharpening it upon the carving-fork.

‘Do you see this?’ said Miss Brass, slicing off about two square inches of cold mutton, after all this preparation, and holding it out on the point of the fork.

The small servant looked hard enough at it with her hungry eyes to see every shred of it, small as it was, and answered, ‘yes.’

‘Then don’t you ever go and say,’ retorted Miss Sally, ‘that you hadn’t meat here. There, eat it up.’

This was soon done. ‘Now, do you want any more?’ said Miss Sally.

The hungry creature answered with a faint ‘No.’ They were evidently going through an established form.

‘You’ve been helped once to meat,’ said Miss Brass, summing up the facts; ‘you have had as much as you can eat, you’re asked if you want any more, and you answer, ‘no!’ Then don’t you ever go and say you were allowanced, mind that.’

With those words, Miss Sally put the meat away and locked the safe, and then drawing near to the small servant, overlooked her while she finished the potatoes.

It was plain that some extraordinary grudge was working in Miss Brass’s gentle breast, and that it was that which impelled her, without the smallest present cause, to rap the child with the blade of the knife, now on her hand, now on her head, and now on her back, as if she found it quite impossible to stand so close to her without administering a few slight knocks. But Mr Swiveller was not a little surprised to see his fellow-clerk, after walking slowly backwards towards the door, as if she were trying to withdraw herself from the room but could not accomplish it, dart suddenly forward, and falling on the small servant give her some hard blows with her clenched hand. The victim cried, but in a subdued manner as if she feared to raise her voice, and Miss Sally, comforting herself with a pinch of snuff, ascended the stairs, just as Richard had safely reached the office.

"Do you see this?"

Chapter 36

Charles Green

Text Illustrated:

The girl withdrew into a corner, while Miss Brass took a key from her pocket, and opening the safe, brought from it a dreary waste of cold potatoes, looking as eatable as Stonehenge. This she placed before the small servant, ordering her to sit down before it, and then, taking up a great carving-knife, made a mighty show of sharpening it upon the carving-fork.

‘Do you see this?’ said Miss Brass, slicing off about two square inches of cold mutton, after all this preparation, and holding it out on the point of the fork.

The small servant looked hard enough at it with her hungry eyes to see every shred of it, small as it was, and answered, ‘yes.’

‘Then don’t you ever go and say,’ retorted Miss Sally, ‘that you hadn’t meat here. There, eat it up.’

This was soon done. ‘Now, do you want any more?’ said Miss Sally.

The hungry creature answered with a faint ‘No.’ They were evidently going through an established form.

‘You’ve been helped once to meat,’ said Miss Brass, summing up the facts; ‘you have had as much as you can eat, you’re asked if you want any more, and you answer, ‘no!’ Then don’t you ever go and say you were allowanced, mind that.’

With those words, Miss Sally put the meat away and locked the safe, and then drawing near to the small servant, overlooked her while she finished the potatoes.

Commentary from Dickens and His Illustrators by Frederic G. Kitton, 1899:

The thirty-two illustrations contributed by Charles Green to the Household Edition of "The Old Curiosity Shop" contrast most favourably with those by "Phiz" in the original issue; these drawings, which, for the most part, were made upon paper by means of the brush-point, are entirely free from the gross exaggeration and caricature which impart such grotesqueness to the majority of the figure subjects by Hablôt Browne for this story. Mr. Green's design for the wrapper enclosing each part of the Crown Edition of the novelist's works (subsequently published by Chapman & Hall) is cleverly conceived, for here he has introduced all the leading personages, happily grouped around the principal figure, Mr. Pickwick, who occupies an elevated position upon a pile of books representing the novels of Dickens. A few years ago Messrs. A. & F. Pears commissioned Mr. Green to design a number of illustrations for a series of their Annuals, the artist's services being specially retained for the following reprints of Dickens's Christmas Books: "A Christmas Carol" (1892), twenty-seven drawings; "The Battle of Life" (1893), twenty-nine drawings; "The Chimes" (1894), thirty drawings; and "The Haunted Man" (1895), thirty drawings. His latest productions as a Dickens illustrator consist of a series of ten new designs, reproduced by photogravure for the Gadshill Edition of "Great Expectations," recently published by Chapman & Hall. Undoubtedly Mr. Green's most important work in connection with Dickens is to be found in his water-colour drawings of scenes from the novels.

Green often transformed his delicate pen and ink illustrations with the addition of watercolour. Also painting in oils, he exhibited at the Royal Academy until 1883. He died at Hampstead 15 years later on 4 May 1898. The Fine Art Society held a memorial show in October of the same year.

The titles of Mr. Charles Green's admirable series of Dickens pictures were supplied to me by the artist himself, who favoured me with a complete list shortly before his death. In reference to these remarkable drawings I have received the following communication from Mr. William Lockwood, of Apsley Hall, Nottingham, for whom they were painted on commission: "The first work of Mr. Green's that really attracted my attention was his famous water-colour Race drawing, entitled, I believe, 'Here they come!' I saw that at a friend's house, and was so struck with admiration of Mr. Green's delicate sense of humour, subtle rendering of character, and fine drawing, that I at once told my friend of my great appreciation of Charles Dickens, and saw that, in my opinion, Mr. Charles Green would make the very best illustrator of his day of that great man's work. I then sought an introduction to Mr. Green, which resulted not only in my beautiful series of drawings, but in a warm friendship with the artist. In the execution of these pictures Mr. Green found most congenial work, and I think fully justified my judgment of his special power. When the series was exhibited at our local museum, it attracted universal admiration and the delighted appreciation of all classes." Mr. Lockwood has generously lent these pictures to many London galleries, including the English Humorists' Exhibition, held at the Royal Institute of Painters in Water-Colours in 1889.

An Interview with Codlin and Short

Chapter 37

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The gentleman pointed to a couple of chairs, and intimated by an emphatic nod of his head that he expected them to be seated. Messrs Codlin and Short, after looking at each other with considerable doubt and indecision, at length sat down—each on the extreme edge of the chair pointed out to him—and held their hats very tight, while the single gentleman filled a couple of glasses from a bottle on the table beside him, and presented them in due form.

‘You’re pretty well browned by the sun, both of you,’ said their entertainer. ‘Have you been travelling?’

Mr Short replied in the affirmative with a nod and a smile. Mr Codlin added a corroborative nod and a short groan, as if he still felt the weight of the Temple on his shoulders.

‘To fairs, markets, races, and so forth, I suppose?’ pursued the single gentleman.

‘Yes, sir,’ returned Short, ‘pretty nigh all over the West of England.’

‘I have talked to men of your craft from North, East, and South,’ returned their host, in rather a hasty manner; ‘but I never lighted on any from the West before.’

‘It’s our reg’lar summer circuit is the West, master,’ said Short; ‘that’s where it is. We takes the East of London in the spring and winter, and the West of England in the summer time. Many’s the hard day’s walking in rain and mud, and with never a penny earned, we’ve had down in the West.’

‘Let me fill your glass again.’

Commentary:

Hablot Knight Browne (with no circumflex over the o, a journalistic addition unaccountably followed by some modern scholars) was born on 11 June 1815, the ninth son in a middle-class family which would ultimately number ten sons and five daughters. His father having died in 1824, the main influence upon the early course of Browne's life seems to have been his brother-in-law, Mr. Elnahan Bicknell, a wealthy, self-made businessman and self-taught collector of modern English art (Turner in particular), who was in later years a neighbour and friend of Ruskin. It was Bicknell who encouraged Browne's artistic talent and arranged for his apprenticeship to the prominent steel engravers, Finden's, as a way of acquiring a trade which would provide a means of self-support for this ninth son in a family of fifteen children. The biographical sources agree that Hablot was not very happy with the tedious labor of engraving, and although he always described his profession as that of "engraver," not use this technique during his long career and the few steel engravings he designed were executed by others. He did certainly become proficient in etching, for in 1833 he was awarded a medal from the Society of Arts for "John Gilpin's Ride," a rather crude performance which nevertheless shows considerable skill in the drawing of horses and the use of light and shadow to indicate modeling of forms (Reproduced in E. Browne). There are stories of Hablot's truancy (visits to the British Museum) and his penchant for fanciful drawing rather than tedious engraving. Whatever the immediate cause, his indentures were canceled in 1834, two years early by mutual consent, and he set up shop sometime during the next two years with Robert Young, a fellow apprentice at Finden's, as etcher, engraver, and illustrator.

Finden's was engaged in the production of many of the popular engravings of the time, including picturesque views and plates for the annuals, which were intended largely as gift books for young ladies. The subjects of such plates were usually portraits of titled ladies and scenes from Byron or Moore, with the occasional comic scene thrown in. Browne must have been influenced to a degree by his tenure at Finden's, but the only known work tying him even indirectly to his unloved masters is Winkles's Cathedrals (1835-42), the first two volumes of which contained designs by Browne.

Winkles had been an apprentice at Finden's, and a number of the line-engraved plates of English and Welsh cathedrals are signed "HKB"; we can perhaps see Browne's characteristic touch in the incidental figures that populate some of the views, but there is really no hint at all of the illustrator about to emerge into public favor, briefly as "N.E.M.O.," and then permanently as "Phiz".

Jerry's Dancing Dogs

Chapter 37

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Stay a minute,’ said Short. ‘A man of the name of Jerry—you know Jerry, Thomas?’

‘Oh, don’t talk to me of Jerrys,’ replied Mr Codlin. ‘How can I care a pinch of snuff for Jerrys, when I think of that ‘ere darling child? “Codlin’s my friend,” she says, “dear, good, kind Codlin, as is always a devising pleasures for me! I don’t object to Short,” she says, “but I cotton to Codlin.”

Once,’ said that gentleman reflectively, ‘she called me Father Codlin. I thought I should have bust!’

‘A man of the name of Jerry, sir,’ said Short, turning from his selfish colleague to their new acquaintance, ‘wot keeps a company of dancing dogs, told me, in a accidental sort of way, that he had seen the old gentleman in connexion with a travelling wax-work, unbeknown to him. As they’d given us the slip, and nothing had come of it, and this was down in the country that he’d been seen, I took no measures about it, and asked no questions

—But I can, if you like.’

‘Is this man in town?’ said the impatient single gentleman. ‘Speak faster.’

‘No he isn’t, but he will be to-morrow, for he lodges in our house,’ replied Mr Short rapidly.

‘Then bring him here,’ said the single gentleman. ‘Here’s a sovereign a-piece. If I can find these people through your means, it is but a prelude to twenty more. Return to me to-morrow, and keep your own counsel on this subject—though I need hardly tell you that; for you’ll do so for your own sakes. Now, give me your address, and leave me.’

The address was given, the two men departed, the crowd went with them, and the single gentleman for two mortal hours walked in uncommon agitation up and down his room, over the wondering heads of Mr Swiveller and Miss Sally Brass.

Mr. Swiveller's Libation

Chapter 38

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘It’s hard work,’ said Richard. ‘What do you say to some beer?’

Kit at first declined, but presently consented, and they adjourned to the neighbouring bar together.

‘We’ll drink our friend what’s-his-name,’ said Dick, holding up the bright frothy pot; ‘—that was talking to you this morning, you know—I know him—a good fellow, but eccentric—very—here’s what’s-his-name!’

Kit pledged him.

‘He lives in my house,’ said Dick; ‘at least in the house occupied by the firm in which I’m a sort of a—of a managing partner—a difficult fellow to get anything out of, but we like him—we like him.’

‘I must be going, sir, if you please,’ said Kit, moving away.

‘Don’t be in a hurry, Christopher,’ replied his patron, ‘we’ll drink your mother.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

‘An excellent woman that mother of yours, Christopher,’ said Mr Swiveller. ‘Who ran to catch me when I fell, and kissed the place to make it well?

My mother. A charming woman. He’s a liberal sort of fellow. We must get him to do something for your mother. Does he know her, Christopher?’

Kit shook his head, and glancing slyly at his questioner, thanked him, and made off before he could say another word.

‘Humph!’ said Mr Swiveller pondering, ‘this is queer. Nothing but mysteries in connection with Brass’s house. I’ll keep my own counsel, however.

Everybody and anybody has been in my confidence as yet, but now I think I’ll set up in business for myself. Queer—very queer!’

After pondering deeply and with a face of exceeding wisdom for some time, Mr Swiveller drank some more of the beer, and summoning a small boy who had been watching his proceedings, poured forth the few remaining drops as a libation on the gravel, and bade him carry the empty vessel to the bar with his compliments, and above all things to lead a sober and temperate life, and abstain from all intoxicating and exciting liquors. Having given him this piece of moral advice for his trouble (which, as he wisely observed, was far better than half-pence) the Perpetual Grand Master of the

Glorious Apollos thrust his hands into his pockets and sauntered away: still pondering as he went.

At Astley's

Chapter 39

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Dear, dear, what a place it looked, that Astley’s; with all the paint, gilding, and looking-glass; the vague smell of horses suggestive of coming wonders; the curtain that hid such gorgeous mysteries; the clean white sawdust down in the circus; the company coming in and taking their places; the fiddlers looking carelessly up at them while they tuned their instruments, as if they didn’t want the play to begin, and knew it all beforehand!

What a glow was that, which burst upon them all, when that long, clear, brilliant row of lights came slowly up; and what the feverish excitement when the little bell rang and the music began in good earnest, with strong parts for the drums, and sweet effects for the triangles! Well might Barbara’s mother say to Kit’s mother that the gallery was the place to see from, and wonder it wasn’t much dearer than the boxes; well might Barbara feel doubtful whether to laugh or cry, in her flutter of delight.

Then the play itself! the horses which little Jacob believed from the first to be alive, and the ladies and gentlemen of whose reality he could be by no means persuaded, having never seen or heard anything at all like them—the firing, which made Barbara wink—the forlorn lady, who made her cry—the tyrant, who made her tremble—the man who sang the song with the lady’s-maid and danced the chorus, who made her laugh—the pony who reared up on his hind legs when he saw the murderer, and wouldn’t hear of walking on all fours again until he was taken into custody—the clown who ventured on such familiarities with the military man in boots—the lady who jumped over the nine-and-twenty ribbons and came down safe upon the horse’s back—everything was delightful, splendid, and surprising! Little Jacob applauded till his hands were sore; Kit cried ‘an-kor’ at the end of everything, the three-act piece included; and Barbara’s mother beat her umbrella on the floor, in her ecstasies, until it was nearly worn down to the gingham.

At length everything was ready, and they went off

Chapter 39

Charles Green

Text Illustrated:

However, it was high time now to be thinking of the play; for which great preparation was required, in the way of shawls and bonnets, not to mention one handkerchief full of oranges and another of apples, which took some time tying up, in consequence of the fruit having a tendency to roll out at the corners. At length, everything was ready, and they went off very fast; Kit’s mother carrying the baby, who was dreadfully wide awake, and Kit holding little Jacob in one hand, and escorting Barbara with the other—a state of things which occasioned the two mothers, who walked behind, to declare that they looked quite family folks, and caused Barbara to blush and say, ‘Now don’t, mother!’ But Kit said she had no call to mind what they said; and indeed she need not have had, if she had known how very far from Kit’s thoughts any love-making was. Poor Barbara!

At last they got to the theatre, which was Astley’s: and in some two minutes after they had reached the yet unopened door, little Jacob was squeezed flat, and the baby had received divers concussions, and Barbara’s mother’s umbrella had been carried several yards off and passed back to her over the shoulders of the people, and Kit had hit a man on the head with the handkerchief of apples for ‘scrowdging’ his parent with unnecessary violence, and there was a great uproar. But, when they were once past the pay-place and tearing away for very life with their checks in their hands, and, above all, when they were fairly in the theatre, and seated in such places that they couldn’t have had better if they had picked them out, and taken them beforehand, all this was looked upon as quite a capital joke, and an essential part of the entertainment.

Mr. Garland and Kit

Chapter 40

Phiz

‘You see, Christopher,’ said Mr Garland, ‘this is a point of much importance to you, and you should understand and consider it in that light.

This gentleman is able to give you more money than I—not, I hope, to carry through the various relations of master and servant, more kindness and confidence, but certainly, Christopher, to give you more money.’

‘Well,’ said Kit, ‘after that, Sir—’

‘Wait a moment,’ interposed Mr Garland. ‘That is not all. You were a very faithful servant to your old employers, as I understand, and should this gentleman recover them, as it is his purpose to attempt doing by every means in his power, I have no doubt that you, being in his service, would meet with your reward. Besides,’ added the old gentleman with stronger emphasis, ‘besides having the pleasure of being again brought into communication with those to whom you seem to be very strongly and disinterestedly attached. You must think of all this, Christopher, and not be rash or hasty in your choice.’

Kit did suffer one twinge, one momentary pang, in keeping the resolution he had already formed, when this last argument passed swiftly into his thoughts, and conjured up the realization of all his hopes and fancies. But it was gone in a minute, and he sturdily rejoined that the gentleman must look out for somebody else, as he did think he might have done at first.

‘He has no right to think that I’d be led away to go to him, sir,’ said Kit, turning round again after half a minute’s hammering. ‘Does he think I’m a fool?’

‘He may, perhaps, Christopher, if you refuse his offer,’ said Mr Garland gravely.

‘Then let him, sir,’ retorted Kit; ‘what do I care, sir, what he thinks? why should I care for his thinking, sir, when I know that I should be a fool, and worse than a fool, sir, to leave the kindest master and mistress that ever was or can be, who took me out of the streets a very poor and hungry lad indeed—poorer and hungrier perhaps than even you think for, sir—to go to him or anybody? If Miss Nell was to come back, ma’am,’ added Kit, turning suddenly to his mistress, ‘why that would be another thing, and perhaps if she wanted me, I might ask you now and then to let me work for her when all was done at home. But when she comes back, I see now that she’ll be rich as old master always said she would, and being a rich young lady, what could she want of me? No, no,’ added Kit, shaking his head sorrowfully, ‘she’ll never want me any more, and bless her, I hope she never may, though I should like to see her too!’

Here Kit drove a nail into the wall, very hard—much harder than was necessary—and having done so, faced about again.

‘There’s the pony, sir,’ said Kit—‘Whisker, ma’am (and he knows so well I’m talking about him that he begins to neigh directly, Sir)—would he let anybody come near him but me, ma’am? Here’s the garden, sir, and Mr Abel, ma’am. Would Mr Abel part with me, Sir, or is there anybody that could be fonder of the garden, ma’am? It would break mother’s heart, Sir, and even little Jacob would have sense enough to cry his eyes out, ma’am, if he thought that Mr Abel could wish to part with me so soon, after having told me, only the other day, that he hoped we might be together for years to come—’

There is no telling how long Kit might have stood upon the ladder, addressing his master and mistress by turns, and generally turning towards the wrong person, if Barbara had not at that moment come running up to say that a messenger from the office had brought a note, which, with an expression of some surprise at Kit’s oratorical appearance, she put into her master’s hand.

Tristram wrote: "Hmm, I don't know if Sally Brass goes after the ladies, there being no ladies in the vicinity so far."

Tristram wrote: "Hmm, I don't know if Sally Brass goes after the ladies, there being no ladies in the vicinity so far."Oops, I meant Quilp goes after the ladies, not Sally! Quilp is very lustful towards women. I agree that Quilp has more in common with Sally than his wife. I'm just surprised he would attract anyone, because he's so evil. It's interesting, though, how both Quilp and Sally are described as monster-like, so that links them together symbolically.

Nice illustrations. The Small Servant by Reynolds is so sympathetic. The Christmas card one is strange for the not-so-jolly theme they chose.

Nice illustrations. The Small Servant by Reynolds is so sympathetic. The Christmas card one is strange for the not-so-jolly theme they chose.

Kim wrote: "At length everything was ready, and they went off

Kim wrote: "At length everything was ready, and they went offChapter 39

Charles Green

Text Illustrated:

However, it was high time now to be thinking of the play; for which great preparation was required, ..."

Oh, I love the two mothers in the Green.

Kim wrote: "Jerry's Dancing Dogs

Kim wrote: "Jerry's Dancing DogsChapter 37

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Stay a minute,’ said Short. ‘A man of the name of Jerry—you know Jerry, Thomas?’

‘Oh, don’t talk to me of Jerrys,’ replied Mr Codlin. ‘H..."

My Penguin edition has a detail of the dogs from this illustration on its cover, and all I can think is that they don't actually want you to know what the book's about: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/344/3...

Alissa wrote: "I agree that Quilp has more in common with Sally than his wife. I'm just surprised he would attract anyone, because he's so evil. It's interesting, though, how both Quilp and Sally are described as monster-like, so that links them together symbolically. ..."

Alissa wrote: "I agree that Quilp has more in common with Sally than his wife. I'm just surprised he would attract anyone, because he's so evil. It's interesting, though, how both Quilp and Sally are described as monster-like, so that links them together symbolically. ..."Yes, I guess so. I find it plausible if the small servant is Quilp and Sally's child, but however it works out I am still so disappointed about this child-abusing turn of events for Sally. What a waste of a character. I could almost take up fan fiction just to fix this.

Julie wrote: "I am still so disappointed about this child-abusing turn of events for Sally."

Julie wrote: "I am still so disappointed about this child-abusing turn of events for Sally."Me too. I enjoyed the humorous depiction of Sally as a sharp lawyer and rough woman who's just "one of the guys," but the child abuse scene was a dark turn I did not expect.

I wouldn't mind reading a fan fiction about her and Dick's friendship. I laughed when he gave her a "hearty slap on the back" and called her a "jolly dog," which she took as a high compliment. I also liked her advice to help Dick relax--just pretend she's not there.

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Compared to that unequal union, it is indeed easier to picture the rough Sally fall in with Quilp for the sole purpose of ... you know."

Well thanks for putting a picture of Sall..."

Thanks for putting it into my head now! ;-) I never thought of it so vividly, but just as an abstract idea.

Well thanks for putting a picture of Sall..."

Thanks for putting it into my head now! ;-) I never thought of it so vividly, but just as an abstract idea.

Kim wrote: "This has to be one of the strangest Christmas Cards I've ever seen:

"

It's for a Scrooge's Christmas, perhaps?

"

It's for a Scrooge's Christmas, perhaps?

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "Jerry's Dancing Dogs

Chapter 37

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Stay a minute,’ said Short. ‘A man of the name of Jerry—you know Jerry, Thomas?’

‘Oh, don’t talk to me of Jerrys,’ replied M..."

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "Jerry's Dancing Dogs

Chapter 37

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Stay a minute,’ said Short. ‘A man of the name of Jerry—you know Jerry, Thomas?’

‘Oh, don’t talk to me of Jerrys,’ replied M..."

Yes. The cover of the dancing dogs makes absolutely no sense to me. Very strange indeed.

Chapter 37

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Stay a minute,’ said Short. ‘A man of the name of Jerry—you know Jerry, Thomas?’

‘Oh, don’t talk to me of Jerrys,’ replied M..."

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "Jerry's Dancing Dogs

Chapter 37

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Stay a minute,’ said Short. ‘A man of the name of Jerry—you know Jerry, Thomas?’

‘Oh, don’t talk to me of Jerrys,’ replied M..."