The Old Curiosity Club discussion

The Old Curiosity Shop

>

TOCS Chapters 41-45

Chapter the Forty-second

On an evening’s wanderings Nell had followed two sisters with whom she felt empathy. Dickens then links Nell to the evening’s mood and conflates her emotions with “a companionship in Nature ... serene and still.” There continues to be an empathy between Nell and Nature. Between her grandfather and herself, however, “there had come a gradual separation, harder to bear than any former sorrow.” Old Trent has been absent every night and often in the day-time as well. Nell knows his absences are due to his gambling. He is still stealing from her; he looks haggard; he shuns her presence.

As Nell meditates on their situation one evening she spies an encampment of gypsies and as she crept closer she sees her grandfather. The vivid truth of her suspicions is present in the firelight. Old Trent is gambling, and to make it worse with the same men who took advantage of him earlier at the public-house. Nell witnesses these men deride Old Trent, cheat him, and encourage him to steal from Mrs Jarley. To emphasize their points they have the gypsy get his cash box, unlock it, and then let the money cascade from fingers into the cash box. To emphasize their point to Old Trent they tell him that “it’s better to lose other people’s money than one’s own.” The weak-minded Old Trent says “I’ll do it ... . I’ll have it, every penny.” Flummoxed by what she has witnessed, Nell wonders “[w]hat shall I do to save him!”

Thoughts

Well, I can’t delay facing the fact that Nell and her father may be grating on some of our Curiosities’ nerves and good nature. Old Trent is selfish and inconsiderate. Worse, he is a gambler, a thief, and a man who is willing to rob his employer and has already robbed his own granddaughter. Nell, for her part, performs the roll of an enabler. Added to that, Dickens has been casting hints, some not too subtle, that Nell may die before the end of the novel. Nell seems too good, too forgiving, too sweet. It seems that there is no middle road with Dickens in this novel.

First, to Old Trent. To what extent does Dickens accurately describe how a gambling addiction could effect a person? How accurate is Dickens in portraying the fact that a person with a gambling addiction might rob his own family to sustain his habit?

Second, Little Nell. We have established that she fulfills the role of the Innocent/Child archetype. We have seen many occasions where Dickens places Nell in plot situations that are nightmarish. Such examples are going to the docks to deliver a message to Quilp, creeping into her old bedroom to get a key to escape from her own house, seeing her grandfather sneak into her room to steal money from her dress, her encounters with various bizarre characters on their travels, and, in this chapter, creeping up to a gypsy fire to watch her grandfather first lose money and then be convinced to steal from Mrs Jarley. Have you noticed how Dickens constantly uses thresholds such as windows, doorways, arches, and sleeping areas to denote and demonstrate how there is trouble in social structures and people’s emotions when one passes in, through, or out of spaces. These recurring objects suggest the presence of turbulence and disorder. Can you see how the attributes of a child would make a person more capable of dealing with disturbing events than an adult? What special adaptive characteristics and coping mechanisms to turbulence and disorder has Nell used to this point in the novel? How successful has she been?

What follows is very powerful. Nell leaves the gypsy camp and “with slow and cautious steps, keeping in the shadow of the hedges, or forcing a path through them or the dry ditches” Nell finally is out of the vision of the gamblers. What follows is, I believe, key to the novel’s understanding: “Then she fled homewards as quickly as she could, torn and bleeding from the wounds of thorns and briars, but more lacerated in mind, and threw herself upon her bed ...”

Nell’s first thought is flight, but she also worries that Old Trent may steal from Mrs Jarley. This thought leads Nell to a “horrible fear.” Nell fears there may be “shrieks and cries piercing the silence of the night” if her father is caught in the middle of a theft. To assuage her worries of what her grandfather could cause, “[s]he stole to the room where the money was, opened the door, and looked in.”

Thoughts

Nell’s thoughts and actions are those of an adult, not a child, yet Dickens constantly reminds us that Nell is a child. How can we account for the different ways Nell is portrayed in the novel?

This is the second time Nell steals into a person’s room. What are the similarities and the differences between this evening’s activity and those when Nell stole the key from Quilp?

Nell’s escape from the gypsy camp to Mrs Jarley’s is a painful one. I think in this chapter there are elements of both the Monomyth and an allusion to the Bible. Nell’s body is “torn and bleeding” from the “wounds of thorns and briars.” I think this chapter is highly suggestive of Joseph Campbell’s theory of the Monomyth where the hero must survive a series of trials. This chapter demonstrates Nell, once again, surviving a trial. I also wonder to what extent Dickens was alluding to the Bible when he mentions “torn and bleeding” and “wounds of thorns.” In terms of Archetypes, Nell is the Child, the Innocent. As such, she represents all that is good. In this chapter her discovery of her grandfather gambling, her flight, and the pain she suffers with the knowledge she has attained that “lacerated her mind” all point (to me, at least) to the Monomyth. That she should be “torn and bleeding” as a result of “thorns” gives the scene a patina of of a Christ figure. She too, will forgive her grandfather his transgressions, as she takes on his sins.

What do you think about this possible interpretation?

Nell returns to the room and discovers her grandfather asleep. She rouses him from his rest and tells him “with an energy that nothing but such terrors could [inspire]” that she has had a horrid dream and they must flee, this very night, from the waxworks and Mrs Jarley. And so, once again, they flee in the middle of the night. As they move through the streets they approach an “old grey castle” where as they approach it’s ruined walls “the moon rose in all her gentle glory, and, from their venerable age, garlanded with ivy, moss, and waving grass, the child looked back upon the sleeping town ... and as she did so, she clasped the hand she held...”. And so this chapter ends, but brings with it many questions, observations, and even, perhaps, speculations.

Thoughts

I believe it is Mary Lou who may be keeping watch on the number of times we have references to hands in TOCS. At the end of this chapter we find another example. Why might there be so many references made to hands? In this particular incidence, what might be the sub-text of Nell and her father holding hands?

Once again Dickens evokes the idea of nightmares as being a part of a person or a settings experience. Why might Dickens be repeating and creating such a pastiche of nightmares, eerie soundscapes, and settings?

This is not the first time Nell has had to take her father by the hand and fled from an impending crisis. To what extent do you think Dickens is repeating the same story line? What might Dickens’s reason or reasons be for repeating such a plot device? Did you find the repeated style effective?

On an evening’s wanderings Nell had followed two sisters with whom she felt empathy. Dickens then links Nell to the evening’s mood and conflates her emotions with “a companionship in Nature ... serene and still.” There continues to be an empathy between Nell and Nature. Between her grandfather and herself, however, “there had come a gradual separation, harder to bear than any former sorrow.” Old Trent has been absent every night and often in the day-time as well. Nell knows his absences are due to his gambling. He is still stealing from her; he looks haggard; he shuns her presence.

As Nell meditates on their situation one evening she spies an encampment of gypsies and as she crept closer she sees her grandfather. The vivid truth of her suspicions is present in the firelight. Old Trent is gambling, and to make it worse with the same men who took advantage of him earlier at the public-house. Nell witnesses these men deride Old Trent, cheat him, and encourage him to steal from Mrs Jarley. To emphasize their points they have the gypsy get his cash box, unlock it, and then let the money cascade from fingers into the cash box. To emphasize their point to Old Trent they tell him that “it’s better to lose other people’s money than one’s own.” The weak-minded Old Trent says “I’ll do it ... . I’ll have it, every penny.” Flummoxed by what she has witnessed, Nell wonders “[w]hat shall I do to save him!”

Thoughts

Well, I can’t delay facing the fact that Nell and her father may be grating on some of our Curiosities’ nerves and good nature. Old Trent is selfish and inconsiderate. Worse, he is a gambler, a thief, and a man who is willing to rob his employer and has already robbed his own granddaughter. Nell, for her part, performs the roll of an enabler. Added to that, Dickens has been casting hints, some not too subtle, that Nell may die before the end of the novel. Nell seems too good, too forgiving, too sweet. It seems that there is no middle road with Dickens in this novel.

First, to Old Trent. To what extent does Dickens accurately describe how a gambling addiction could effect a person? How accurate is Dickens in portraying the fact that a person with a gambling addiction might rob his own family to sustain his habit?

Second, Little Nell. We have established that she fulfills the role of the Innocent/Child archetype. We have seen many occasions where Dickens places Nell in plot situations that are nightmarish. Such examples are going to the docks to deliver a message to Quilp, creeping into her old bedroom to get a key to escape from her own house, seeing her grandfather sneak into her room to steal money from her dress, her encounters with various bizarre characters on their travels, and, in this chapter, creeping up to a gypsy fire to watch her grandfather first lose money and then be convinced to steal from Mrs Jarley. Have you noticed how Dickens constantly uses thresholds such as windows, doorways, arches, and sleeping areas to denote and demonstrate how there is trouble in social structures and people’s emotions when one passes in, through, or out of spaces. These recurring objects suggest the presence of turbulence and disorder. Can you see how the attributes of a child would make a person more capable of dealing with disturbing events than an adult? What special adaptive characteristics and coping mechanisms to turbulence and disorder has Nell used to this point in the novel? How successful has she been?

What follows is very powerful. Nell leaves the gypsy camp and “with slow and cautious steps, keeping in the shadow of the hedges, or forcing a path through them or the dry ditches” Nell finally is out of the vision of the gamblers. What follows is, I believe, key to the novel’s understanding: “Then she fled homewards as quickly as she could, torn and bleeding from the wounds of thorns and briars, but more lacerated in mind, and threw herself upon her bed ...”

Nell’s first thought is flight, but she also worries that Old Trent may steal from Mrs Jarley. This thought leads Nell to a “horrible fear.” Nell fears there may be “shrieks and cries piercing the silence of the night” if her father is caught in the middle of a theft. To assuage her worries of what her grandfather could cause, “[s]he stole to the room where the money was, opened the door, and looked in.”

Thoughts

Nell’s thoughts and actions are those of an adult, not a child, yet Dickens constantly reminds us that Nell is a child. How can we account for the different ways Nell is portrayed in the novel?

This is the second time Nell steals into a person’s room. What are the similarities and the differences between this evening’s activity and those when Nell stole the key from Quilp?

Nell’s escape from the gypsy camp to Mrs Jarley’s is a painful one. I think in this chapter there are elements of both the Monomyth and an allusion to the Bible. Nell’s body is “torn and bleeding” from the “wounds of thorns and briars.” I think this chapter is highly suggestive of Joseph Campbell’s theory of the Monomyth where the hero must survive a series of trials. This chapter demonstrates Nell, once again, surviving a trial. I also wonder to what extent Dickens was alluding to the Bible when he mentions “torn and bleeding” and “wounds of thorns.” In terms of Archetypes, Nell is the Child, the Innocent. As such, she represents all that is good. In this chapter her discovery of her grandfather gambling, her flight, and the pain she suffers with the knowledge she has attained that “lacerated her mind” all point (to me, at least) to the Monomyth. That she should be “torn and bleeding” as a result of “thorns” gives the scene a patina of of a Christ figure. She too, will forgive her grandfather his transgressions, as she takes on his sins.

What do you think about this possible interpretation?

Nell returns to the room and discovers her grandfather asleep. She rouses him from his rest and tells him “with an energy that nothing but such terrors could [inspire]” that she has had a horrid dream and they must flee, this very night, from the waxworks and Mrs Jarley. And so, once again, they flee in the middle of the night. As they move through the streets they approach an “old grey castle” where as they approach it’s ruined walls “the moon rose in all her gentle glory, and, from their venerable age, garlanded with ivy, moss, and waving grass, the child looked back upon the sleeping town ... and as she did so, she clasped the hand she held...”. And so this chapter ends, but brings with it many questions, observations, and even, perhaps, speculations.

Thoughts

I believe it is Mary Lou who may be keeping watch on the number of times we have references to hands in TOCS. At the end of this chapter we find another example. Why might there be so many references made to hands? In this particular incidence, what might be the sub-text of Nell and her father holding hands?

Once again Dickens evokes the idea of nightmares as being a part of a person or a settings experience. Why might Dickens be repeating and creating such a pastiche of nightmares, eerie soundscapes, and settings?

This is not the first time Nell has had to take her father by the hand and fled from an impending crisis. To what extent do you think Dickens is repeating the same story line? What might Dickens’s reason or reasons be for repeating such a plot device? Did you find the repeated style effective?

Chapter the Forty-third

This chapter opens with Dickens asserting Nell’s heroic character. As her grandfather “seemed to crouch before her, and to shrink and cower down as if in the presence of some superior creature, the child herself was sensible of a new feeling within her, which elevated her nature, and inspired her with an energy and confidence she had never known.” Nell watched over her grandfather as he slept with “untiring eyes” until fatigue “stole over her at last ... and they slept side by side. Nell is awakened by “[a] confused sound of voices” that “mingled with her dreams” to find a rough man hovering over her. Behind him is a boat with “neither oar or sail, but was towed by a couple of horses.” She accepts the offer of the man to take them to the next town. And so the next stage of Nell’s odyssey begins.

The men “were in truth very rugged, noisy fellows, and quite brutal among themselves.” To Nell and old Trent, however, they were not unkind. Nell reluctantly joins in on a few songs during the night and in the morning arrives in an industrial town with “buildings trembling with the working of engines ... shrieks and throbbing; the tall chimneys vomiting forth a blue vapour, which hung ... above the housetops and filled the air with gloom.” In this place Nell and old Trent stood “in the pouring rain, as strange, bewildered, and confused, as if they had lived a thousand years before, and were raised from the dead and placed there by a miracle.”

Thoughts

This chapter has one central story line with some interesting suggestions and possibilities. Let’s have a look.

The weather has turned bad. It is raining and the town is a place where chimneys “vomit ... ill-favoured clouds” and “fill the air with gloom.” With this description what might we guess will follow in the next chapter?

The river men take Nell and her grandfather to a town that is hellish. They are confused and exhausted. Looking around, they feel they had lived a thousand years ago, and “were raised from the dead.” What do you think Dickens might be suggesting when he places Nell and her father in a temporal situation 1000 years before the present day? How is the present day portrayed? How has the world changed in these 1000 years?

This chapter opens with Dickens asserting Nell’s heroic character. As her grandfather “seemed to crouch before her, and to shrink and cower down as if in the presence of some superior creature, the child herself was sensible of a new feeling within her, which elevated her nature, and inspired her with an energy and confidence she had never known.” Nell watched over her grandfather as he slept with “untiring eyes” until fatigue “stole over her at last ... and they slept side by side. Nell is awakened by “[a] confused sound of voices” that “mingled with her dreams” to find a rough man hovering over her. Behind him is a boat with “neither oar or sail, but was towed by a couple of horses.” She accepts the offer of the man to take them to the next town. And so the next stage of Nell’s odyssey begins.

The men “were in truth very rugged, noisy fellows, and quite brutal among themselves.” To Nell and old Trent, however, they were not unkind. Nell reluctantly joins in on a few songs during the night and in the morning arrives in an industrial town with “buildings trembling with the working of engines ... shrieks and throbbing; the tall chimneys vomiting forth a blue vapour, which hung ... above the housetops and filled the air with gloom.” In this place Nell and old Trent stood “in the pouring rain, as strange, bewildered, and confused, as if they had lived a thousand years before, and were raised from the dead and placed there by a miracle.”

Thoughts

This chapter has one central story line with some interesting suggestions and possibilities. Let’s have a look.

The weather has turned bad. It is raining and the town is a place where chimneys “vomit ... ill-favoured clouds” and “fill the air with gloom.” With this description what might we guess will follow in the next chapter?

The river men take Nell and her grandfather to a town that is hellish. They are confused and exhausted. Looking around, they feel they had lived a thousand years ago, and “were raised from the dead.” What do you think Dickens might be suggesting when he places Nell and her father in a temporal situation 1000 years before the present day? How is the present day portrayed? How has the world changed in these 1000 years?

Chapter the Forty-fourth

The town is not only a visual Hell but an auditory one as well. The first paragraph places us within a cauldron of sound. As readers we confront sounds such as “the roar of carts and wagons laden with clashing wares, the slipping of horses’ feet upon the wet and greasy pavement, the rattling of the rain ... the jostling ... of passengers ... and all the noise and tumult of a crowded street.” To escape the rain and the cacophony of sound Nell seeks shelter in a low archway. Once again, Dickens evokes the trope of a nightmarish world, a world of disunity and mass confusion. Evening comes and Nell moves on. Her grandfather begins to grumble and complain. Nell tells him they had to leave where they were because of a dream she had. Nell does not tell her grandfather that she invented the nightmare in order to save him from his real addictive nightmare of gambling.

Thoughts

What is the purpose of Dickens creating yet another nightmarish place? How successful has he been in evoking the mood?

The next paragraph presents an analepsis which takes us back to the illustration for chapter 15 titled “A Rest by the Way.” There is an intrinsic link from the illustration to the letterpress of this chapter. In order to calm her grandfather, and no doubt herself, Little Nell tells him that “[i]f we were in the country now ... we should find some good old tree, stretching out his green arms as if he loved us, and nodding and rustling as if he would have us fall asleep, thinking of him while he watched. Please God, we shall be there soon.” From this wish, Dickens propels us to the opposite extreme of emotion when Nell seeks another “deep old doorway” and from it comes “a black figure” that was “[t]he form ... of a man, miserably clad and begrimed with smoke.” This figure turns out to be a man sympathetic to the plight of Nell and her grandfather who promises “I can give you warmth.” He takes Nell in his arms and carries her tenderly to what could well be likened to a Hell on earth. This mysterious man then announces “[t]his is the place” and then he “put[s] Nell down and take[s] her hand. Don’t be afraid [ he says] There’s nobody here will harm you.” And here, I think, we should pause. Nell and her grandfather have entered yet another dark, noisy, nightmare world. They have done so in a very symbolic manner. Nell has been carried across a threshold “tenderly ... as if she had been an infant.” There has been a transference of roles as well. Once, it was Nell who took care of her father, and guided him to places of safety. Now it is Nell who is being cared for and protected. This transference of roles is seen most clearly when the man puts “Nell down and take[s] her hand.” Before it was Nell who took her father’s hand to guide him and give him a feeling of security. At this new place Nell is assured that she should not be afraid and that “nobody here will harm you.” In terms of Campbell’s Monomyth, we have in this action the crossing of a threshold and arrival in a new place.

Thoughts

What was your initial thoughts when this unnamed man took Nell and her grandfather to this hellish place?

Mary Lou has been tracking the number of times the word hand/hands has been incorporated into the text. What do you make of the scene where a stranger with “hollow cheeks, sharp features, and sunken eyes” takes Nell’s hand, and assumes the role of her guide, just as earlier Nell has assumed the same role with her grandfather?

In terms of allegory and symbolism, we have had Nell and old Trent being conducted down a river to a new shore. This new place is one of darkness, confusion, cacophony, inclement weather, and fiery heat. There has been a transference of roles. Nell has been carried into a subterranean place where there is a constant fire. What could all of this suggest?

Specifically, the place they are now in is described as a “lofty building, supported by pillars of iron, with great black apertures ... with the beating of hammers and roar of furnaces” with “strange unearthly noises never heard elsewhere.” It is a place of “demons among the flame and smoke.” From the “white-hot furnace-doors” the flames lick the fuel. Surely Dickens has cast this place as a Hell on earth. Nell’s new friend spreads Nell’s cloak on the ground so she can rest. For him, his night is spent watching the flames “and the white ashes as they fell into their bright hot grave below.” Nell and the man talk about the fire and he tells Nell that “[i]t has been alive as long as I have ... . It is like a book to me ... the only book I have ever learned to read ... . It’s music, for I should know its voice among a thousand, and there are other voices in its roar. It has pictures too.” Here is a second example of analepsis. Earlier in the novel we saw a reference to Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and the novel’s pictures. Bunyon’s Pilgrim’s Progress functions as a synecdoche to the travels of Nell and her grandfather. Here, we see Dickens incorporating reiteration in a unique manner. He has transferred Pilgrim’s Progress into a fire which is being read by the unnamed rescuer of Nell and her grandfather. The man tells Nell he reads the fire as a book: “[y]ou don’t know how many strange faces and scenes I trace in the red-not coals. It’s my memory, that fire, and shows me all my life.”

Thoughts

What do you think was the intention of Dickens in portraying the building as he did? Does the place have any resemblance to any places in myth or the Bible? If so, what might Dickens’s larger motivation be in this chapter or the wider context of the novel?

What might the stranger that helps Nell and her father represent in terms of myth, the Bible, or Carl Jung’s archetypes? What has lead you to that conclusion?

Do you think Dickens meant for the reader to see how the fire in this chapter could be linked to the reference to Pilgrim’s Progress earlier in the novel? If so, for what reason(s)? If not, please feel free to comment as well.

In the morning their new friend shares his merger breakfast with Nell and old Trent. During the breakfast conversation he speaks of a road that will lead to a remote village that beyond the world of his furnace doors. The man shows them “by which road they must leave the town, and what coarse they should hold when they had gained it.” Thus, he performs the role of their guide. Before Nell and her grandfather are out of sight the man runs after them and “pressing her hand, left something in it - two old battered, smoke-encrusted penny pieces.” Dickens comments “[w]ho knows but they shone as brightly in the eyes of angels as golden gifts that have been chronicled on tombs?”

And thus they separated; the child to lead her sacred charge further from guilt and shame, and the labourer to attach a fresh interest to the spot where his guests had slept, and read new histories in his furnace fire.”

Thoughts

Why do you think Dickens did not name to the helpful labourer?

Why would Dickens call the grandfather Nell’s “sacred charge”?

What might be the meaning be of the labourer giving two worn pennies that shone as bright “in the eyes of angels”?

What might the road that Nell is now pursuing represent or symbolize?

To what extent do you think Dickens overdid the melodrama in this chapter?

Dickens has set this chapter in an industrial town which is described in very harsh terms. Why might Dickens have included this setting in a novel that has so many pastoral settings?

The town is not only a visual Hell but an auditory one as well. The first paragraph places us within a cauldron of sound. As readers we confront sounds such as “the roar of carts and wagons laden with clashing wares, the slipping of horses’ feet upon the wet and greasy pavement, the rattling of the rain ... the jostling ... of passengers ... and all the noise and tumult of a crowded street.” To escape the rain and the cacophony of sound Nell seeks shelter in a low archway. Once again, Dickens evokes the trope of a nightmarish world, a world of disunity and mass confusion. Evening comes and Nell moves on. Her grandfather begins to grumble and complain. Nell tells him they had to leave where they were because of a dream she had. Nell does not tell her grandfather that she invented the nightmare in order to save him from his real addictive nightmare of gambling.

Thoughts

What is the purpose of Dickens creating yet another nightmarish place? How successful has he been in evoking the mood?

The next paragraph presents an analepsis which takes us back to the illustration for chapter 15 titled “A Rest by the Way.” There is an intrinsic link from the illustration to the letterpress of this chapter. In order to calm her grandfather, and no doubt herself, Little Nell tells him that “[i]f we were in the country now ... we should find some good old tree, stretching out his green arms as if he loved us, and nodding and rustling as if he would have us fall asleep, thinking of him while he watched. Please God, we shall be there soon.” From this wish, Dickens propels us to the opposite extreme of emotion when Nell seeks another “deep old doorway” and from it comes “a black figure” that was “[t]he form ... of a man, miserably clad and begrimed with smoke.” This figure turns out to be a man sympathetic to the plight of Nell and her grandfather who promises “I can give you warmth.” He takes Nell in his arms and carries her tenderly to what could well be likened to a Hell on earth. This mysterious man then announces “[t]his is the place” and then he “put[s] Nell down and take[s] her hand. Don’t be afraid [ he says] There’s nobody here will harm you.” And here, I think, we should pause. Nell and her grandfather have entered yet another dark, noisy, nightmare world. They have done so in a very symbolic manner. Nell has been carried across a threshold “tenderly ... as if she had been an infant.” There has been a transference of roles as well. Once, it was Nell who took care of her father, and guided him to places of safety. Now it is Nell who is being cared for and protected. This transference of roles is seen most clearly when the man puts “Nell down and take[s] her hand.” Before it was Nell who took her father’s hand to guide him and give him a feeling of security. At this new place Nell is assured that she should not be afraid and that “nobody here will harm you.” In terms of Campbell’s Monomyth, we have in this action the crossing of a threshold and arrival in a new place.

Thoughts

What was your initial thoughts when this unnamed man took Nell and her grandfather to this hellish place?

Mary Lou has been tracking the number of times the word hand/hands has been incorporated into the text. What do you make of the scene where a stranger with “hollow cheeks, sharp features, and sunken eyes” takes Nell’s hand, and assumes the role of her guide, just as earlier Nell has assumed the same role with her grandfather?

In terms of allegory and symbolism, we have had Nell and old Trent being conducted down a river to a new shore. This new place is one of darkness, confusion, cacophony, inclement weather, and fiery heat. There has been a transference of roles. Nell has been carried into a subterranean place where there is a constant fire. What could all of this suggest?

Specifically, the place they are now in is described as a “lofty building, supported by pillars of iron, with great black apertures ... with the beating of hammers and roar of furnaces” with “strange unearthly noises never heard elsewhere.” It is a place of “demons among the flame and smoke.” From the “white-hot furnace-doors” the flames lick the fuel. Surely Dickens has cast this place as a Hell on earth. Nell’s new friend spreads Nell’s cloak on the ground so she can rest. For him, his night is spent watching the flames “and the white ashes as they fell into their bright hot grave below.” Nell and the man talk about the fire and he tells Nell that “[i]t has been alive as long as I have ... . It is like a book to me ... the only book I have ever learned to read ... . It’s music, for I should know its voice among a thousand, and there are other voices in its roar. It has pictures too.” Here is a second example of analepsis. Earlier in the novel we saw a reference to Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and the novel’s pictures. Bunyon’s Pilgrim’s Progress functions as a synecdoche to the travels of Nell and her grandfather. Here, we see Dickens incorporating reiteration in a unique manner. He has transferred Pilgrim’s Progress into a fire which is being read by the unnamed rescuer of Nell and her grandfather. The man tells Nell he reads the fire as a book: “[y]ou don’t know how many strange faces and scenes I trace in the red-not coals. It’s my memory, that fire, and shows me all my life.”

Thoughts

What do you think was the intention of Dickens in portraying the building as he did? Does the place have any resemblance to any places in myth or the Bible? If so, what might Dickens’s larger motivation be in this chapter or the wider context of the novel?

What might the stranger that helps Nell and her father represent in terms of myth, the Bible, or Carl Jung’s archetypes? What has lead you to that conclusion?

Do you think Dickens meant for the reader to see how the fire in this chapter could be linked to the reference to Pilgrim’s Progress earlier in the novel? If so, for what reason(s)? If not, please feel free to comment as well.

In the morning their new friend shares his merger breakfast with Nell and old Trent. During the breakfast conversation he speaks of a road that will lead to a remote village that beyond the world of his furnace doors. The man shows them “by which road they must leave the town, and what coarse they should hold when they had gained it.” Thus, he performs the role of their guide. Before Nell and her grandfather are out of sight the man runs after them and “pressing her hand, left something in it - two old battered, smoke-encrusted penny pieces.” Dickens comments “[w]ho knows but they shone as brightly in the eyes of angels as golden gifts that have been chronicled on tombs?”

And thus they separated; the child to lead her sacred charge further from guilt and shame, and the labourer to attach a fresh interest to the spot where his guests had slept, and read new histories in his furnace fire.”

Thoughts

Why do you think Dickens did not name to the helpful labourer?

Why would Dickens call the grandfather Nell’s “sacred charge”?

What might be the meaning be of the labourer giving two worn pennies that shone as bright “in the eyes of angels”?

What might the road that Nell is now pursuing represent or symbolize?

To what extent do you think Dickens overdid the melodrama in this chapter?

Dickens has set this chapter in an industrial town which is described in very harsh terms. Why might Dickens have included this setting in a novel that has so many pastoral settings?

Chapter the Forty-fifth

I’m getting a feeling of unease. As Nell leads her dependent father away from the grim city and into the country again she muses “if we get clear of these dreadful places though it is only to lie down and die, with what a grateful heart I shall thank God for such a mercy.” Nell’s feet are sore and she has pains in all [her] limbs from the wet of yesterday. Here we see Nell in discomfort and no longer hiding her emotions from old Trent. They walk on and Dickens tells us that “the pains that racked her joints were of no common variety.” They enter a town of dismal complexion where “nothing could live but on the surface of stagnant ponds.” This place is yet another in a long line of locations that strongly suggest nightmarish dreams. As you read this chapter look for the words that are used to describe the sounds and the revolting phrases such as “ black vomit.” Dickens layers image upon image, sound upon sound, whirling disorientation upon whirling disorientation. If we thought the last chapter presented a vision of Hell, this place rivals any hellish place Dante described. Into Nell’s vision comes figures seemingly spawned in Dante’s hell. Dickens writes that Nell had “no fear for herself, for she was past it now.” Still, Nell considers Old Trent. She falls into a slumber and had “pleasant dreams of the little scholar all night long.”

Thoughts

In the opening paragraphs of this chapter Dickens unequivocally tells the reader that Nell’s strength and health are failing rapidly. Why might Dickens pair Nell’s failing health with the horrid surrounding energy and images of this place? How successful was he? How did you respond to these first paragraphs?

What possible reason might there be for Dickens introducing the “little scholar” into the plot again?

We continue to get instances, places and events that are nightmarish. What might Dickens’s purpose be?

Morning comes and we read that Nell is much weaker in sight and hearing but still she does not complain. Nell has the “conviction that she was very ill, perhaps dying; but [had] no fear or anxiety.” She does not eat. Her grandfather “ate greedily, which she was glad to see.” When Nell asks for more food from a “wretched hovel” she is rejected. Soon after Nell encounters the pain of other parents whose children are dead and dumb and transported. It seems anywhere and everywhere Nell goes there is pain, misery and death. Soon Nell is very enfeebled, but they see a person ahead of them, on foot, leaning upon a stout stick and reading a book. They approach the man, and with “faint words” ask his help. He turns his head towards them and Nell utters “a wild shriek, and fell senseless at his feet.”

Thoughts

Nell’s trials and hardships seem unending, and her grandfather is both helpless and useless to her. Like many of you, I have developed a healthy dislike for Old Trent. Do you think that was Dickens’s intention for his reading audience?

Nell’s self-sacrifice is remarkable, and, to many, simply far too dramatic and overwritten. To what extent do you think Dickens was aware that his melodrama was far too excessive in TOCS? How do you think he would rationalize his over-writing of such chapters as this one? On the other hand, would Dickens’s original readers think he was, in fact, over-writing Nell’s character?

Nell has many earlier episodes of crying, but at the end of this chapter she faints. Do you find her fainting more aggravating than her crying? :-)

The elements of the Monomyth that pertain to the descent into the underworld are in clear evidence in these chapters. Looking at the Bible and literary texts such as The Odyssey, what similarities in pattern do you see?

Reflections

Nell and her grandfather have been thrust into a world that is no longer filled with various entertainers and carnival personalities. No longer is their journey one that offered some amusement and entertainment. Now, they are thrust into a dark world of fire, heat, noise, and filth. There are, however, constants. Regardless of the places Nell and old Trent go, the events that occur, the people they encounter, or the experiences they see all contain elements of a nightmare. Sounds swirl around them. Many people they encounter are disfigured or distorted. The characters of the waxworks remain representations of real humans, and the wax figures themselves can be mutated into other configurations. How can any young person, any elderly individual, maintain their focus, their goal with so much of the world distorted and hostile? Campbell’s Monomyth gives us a method or seeing a pattern to these events, but we need not use it to enjoy the novel.

In these chapters we also see Dickens referring to earlier events, situations and illustrations in the novel to draw the reader both back to what was and, in different spaces, propelling us forward to the ever-increasing possibility of Nell’s fate. To me, unlike in Dickens’s earlier novels, in TOCS we see a more tightly constructed plot, a more fully developed characters, and a stronger author’s vision.

I’m getting a feeling of unease. As Nell leads her dependent father away from the grim city and into the country again she muses “if we get clear of these dreadful places though it is only to lie down and die, with what a grateful heart I shall thank God for such a mercy.” Nell’s feet are sore and she has pains in all [her] limbs from the wet of yesterday. Here we see Nell in discomfort and no longer hiding her emotions from old Trent. They walk on and Dickens tells us that “the pains that racked her joints were of no common variety.” They enter a town of dismal complexion where “nothing could live but on the surface of stagnant ponds.” This place is yet another in a long line of locations that strongly suggest nightmarish dreams. As you read this chapter look for the words that are used to describe the sounds and the revolting phrases such as “ black vomit.” Dickens layers image upon image, sound upon sound, whirling disorientation upon whirling disorientation. If we thought the last chapter presented a vision of Hell, this place rivals any hellish place Dante described. Into Nell’s vision comes figures seemingly spawned in Dante’s hell. Dickens writes that Nell had “no fear for herself, for she was past it now.” Still, Nell considers Old Trent. She falls into a slumber and had “pleasant dreams of the little scholar all night long.”

Thoughts

In the opening paragraphs of this chapter Dickens unequivocally tells the reader that Nell’s strength and health are failing rapidly. Why might Dickens pair Nell’s failing health with the horrid surrounding energy and images of this place? How successful was he? How did you respond to these first paragraphs?

What possible reason might there be for Dickens introducing the “little scholar” into the plot again?

We continue to get instances, places and events that are nightmarish. What might Dickens’s purpose be?

Morning comes and we read that Nell is much weaker in sight and hearing but still she does not complain. Nell has the “conviction that she was very ill, perhaps dying; but [had] no fear or anxiety.” She does not eat. Her grandfather “ate greedily, which she was glad to see.” When Nell asks for more food from a “wretched hovel” she is rejected. Soon after Nell encounters the pain of other parents whose children are dead and dumb and transported. It seems anywhere and everywhere Nell goes there is pain, misery and death. Soon Nell is very enfeebled, but they see a person ahead of them, on foot, leaning upon a stout stick and reading a book. They approach the man, and with “faint words” ask his help. He turns his head towards them and Nell utters “a wild shriek, and fell senseless at his feet.”

Thoughts

Nell’s trials and hardships seem unending, and her grandfather is both helpless and useless to her. Like many of you, I have developed a healthy dislike for Old Trent. Do you think that was Dickens’s intention for his reading audience?

Nell’s self-sacrifice is remarkable, and, to many, simply far too dramatic and overwritten. To what extent do you think Dickens was aware that his melodrama was far too excessive in TOCS? How do you think he would rationalize his over-writing of such chapters as this one? On the other hand, would Dickens’s original readers think he was, in fact, over-writing Nell’s character?

Nell has many earlier episodes of crying, but at the end of this chapter she faints. Do you find her fainting more aggravating than her crying? :-)

The elements of the Monomyth that pertain to the descent into the underworld are in clear evidence in these chapters. Looking at the Bible and literary texts such as The Odyssey, what similarities in pattern do you see?

Reflections

Nell and her grandfather have been thrust into a world that is no longer filled with various entertainers and carnival personalities. No longer is their journey one that offered some amusement and entertainment. Now, they are thrust into a dark world of fire, heat, noise, and filth. There are, however, constants. Regardless of the places Nell and old Trent go, the events that occur, the people they encounter, or the experiences they see all contain elements of a nightmare. Sounds swirl around them. Many people they encounter are disfigured or distorted. The characters of the waxworks remain representations of real humans, and the wax figures themselves can be mutated into other configurations. How can any young person, any elderly individual, maintain their focus, their goal with so much of the world distorted and hostile? Campbell’s Monomyth gives us a method or seeing a pattern to these events, but we need not use it to enjoy the novel.

In these chapters we also see Dickens referring to earlier events, situations and illustrations in the novel to draw the reader both back to what was and, in different spaces, propelling us forward to the ever-increasing possibility of Nell’s fate. To me, unlike in Dickens’s earlier novels, in TOCS we see a more tightly constructed plot, a more fully developed characters, and a stronger author’s vision.

Peter, you give me too much credit, I'm afraid. I'm noticing the mention of hands, but not tracking them. I wish I had remembered to do so more meticulously. As for their symbolism, I've no idea. I keep coming back to the phrase, "the right hand of God." But I haven't seen a connection between that phrase and the use of hands in our story.

Peter, you give me too much credit, I'm afraid. I'm noticing the mention of hands, but not tracking them. I wish I had remembered to do so more meticulously. As for their symbolism, I've no idea. I keep coming back to the phrase, "the right hand of God." But I haven't seen a connection between that phrase and the use of hands in our story. Dickens certainly isn't being subtle in his symbolism of the filthy industrial city and furnace fire. If our Christ-figure has descended into Hell, can we assume that soon she'll ascend to Heaven? And will a judgment follow?

As a casual reader, I have to say that I'm getting a bit tired of the odyssey. I was pleased when Nell and Grandfather seemed to settle down in a comparatively comfortable life with Mrs. Jarley. But now they're on the move again, just when the Lodger and Kit's mum are setting out to find them. I guess the chase scene is coming up, so I can hop out to the lobby and replenish my popcorn.

As a casual reader, I have to say that I'm getting a bit tired of the odyssey. I was pleased when Nell and Grandfather seemed to settle down in a comparatively comfortable life with Mrs. Jarley. But now they're on the move again, just when the Lodger and Kit's mum are setting out to find them. I guess the chase scene is coming up, so I can hop out to the lobby and replenish my popcorn.

Peter wrote: "In terms of allegory and symbolism, we have had Nell and old Trent being conducted down a river to a new shore. This new place is one of darkness, confusion, cacophony, inclement weather, and fiery heat. There has been a transference of roles. Nell has been carried into a subterranean place where there is a constant fire. What could all of this suggest?..."

Peter wrote: "In terms of allegory and symbolism, we have had Nell and old Trent being conducted down a river to a new shore. This new place is one of darkness, confusion, cacophony, inclement weather, and fiery heat. There has been a transference of roles. Nell has been carried into a subterranean place where there is a constant fire. What could all of this suggest?..."Very reminiscent of Styx and Charon.

Hi Mary Lou

Just your noticing the repeated mention of hands gives us all something to consider and think about. Thank you. The Christian symbolism, the Monomyth, and the suggestive elements of Mythology do tend to fade in and out of focus as the novel progresses. To me, it seems that Dickens has many (perhaps too many) frameworks in this story. Still, he is a young author and he does tighten up his storylines in later novels ...

One weird comment. We are babysitting our grandson today and he is just beginning to walk unaided. A few steps, followed by a gentle tumble or fall to the ground. Perhaps there is an analogy here. Dickens stumbles in his plot construction in his earlier novels but we know what is to come with both Dickens’s plots and Ellis walking on his own.

By all means replenish the popcorn. There is much more to come.

Just your noticing the repeated mention of hands gives us all something to consider and think about. Thank you. The Christian symbolism, the Monomyth, and the suggestive elements of Mythology do tend to fade in and out of focus as the novel progresses. To me, it seems that Dickens has many (perhaps too many) frameworks in this story. Still, he is a young author and he does tighten up his storylines in later novels ...

One weird comment. We are babysitting our grandson today and he is just beginning to walk unaided. A few steps, followed by a gentle tumble or fall to the ground. Perhaps there is an analogy here. Dickens stumbles in his plot construction in his earlier novels but we know what is to come with both Dickens’s plots and Ellis walking on his own.

By all means replenish the popcorn. There is much more to come.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "In terms of allegory and symbolism, we have had Nell and old Trent being conducted down a river to a new shore. This new place is one of darkness, confusion, cacophony, inclement weat..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "In terms of allegory and symbolism, we have had Nell and old Trent being conducted down a river to a new shore. This new place is one of darkness, confusion, cacophony, inclement weat..."I thought so too, especially with the coins.

If Nell and her grandfather just went to hell, it seems odd to me that they met such a nice guy there. Granted he had obviously been in hell himself, but his time there seemed to leave him compassionate. It was because he was remembering his own terrible childhood that the fire-watching man offered to shelter Nell for the night.

If Nell and her grandfather just went to hell, it seems odd to me that they met such a nice guy there. Granted he had obviously been in hell himself, but his time there seemed to leave him compassionate. It was because he was remembering his own terrible childhood that the fire-watching man offered to shelter Nell for the night.

Wherever Nell and her grandfather went, I was wishing she would continue on the next day without him. No such luck though.

I am wondering if Nell was in perfect health when she started on this journey with her annoying grandfather, or if she was one of those Dickens characters who was already wasting away of some disease and having the grandfather she has is making her illness worse. Or did it all start with her being exhausted and worn out by all this walking.

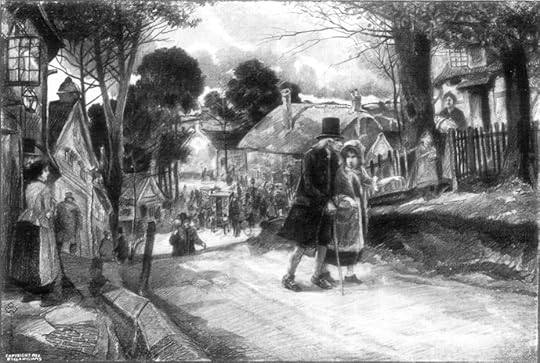

Kit's mother on a journey

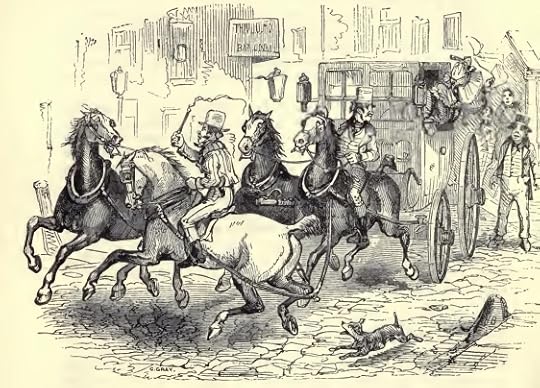

Chapter 41

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

To tell how Kit then hustled into the box all sorts of things which could, by no remote contingency, be wanted, and how he left out everything likely to be of the smallest use; how a neighbour was persuaded to come and stop with the children, and how the children at first cried dismally, and then laughed heartily on being promised all kinds of impossible and unheard-of toys; how Kit’s mother wouldn’t leave off kissing them, and how Kit couldn’t make up his mind to be vexed with her for doing it; would take more time and room than you and I can spare. So, passing over all such matters, it is sufficient to say that within a few minutes after the two hours had expired, Kit and his mother arrived at the Notary’s door, where a post-chaise was already waiting.

‘With four horses I declare!’ said Kit, quite aghast at the preparations. ‘Well you are going to do it, mother! Here she is, Sir. Here’s my mother. She’s quite ready, sir.’

‘That’s well,’ returned the gentleman. ‘Now, don’t be in a flutter, ma’am; you’ll be taken great care of. Where’s the box with the new clothing and necessaries for them?’

‘Here it is,’ said the Notary. ‘In with it, Christopher.’

‘All right, Sir,’ replied Kit. ‘Quite ready now, sir.’

‘Then come along,’ said the single gentleman. And thereupon he gave his arm to Kit’s mother, handed her into the carriage as politely as you please, and took his seat beside her.

Up went the steps, bang went the door, round whirled the wheels, and off they rattled, with Kit’s mother hanging out at one window waving a damp pocket-handkerchief and screaming out a great many messages to little Jacob and the baby, of which nobody heard a word.

Kit stood in the middle of the road, and looked after them with tears in his eyes—not brought there by the departure he witnessed, but by the return to which he looked forward. ‘They went away,’ he thought, ‘on foot with nobody to speak to them or say a kind word at parting, and they’ll come back, drawn by four horses, with this rich gentleman for their friend, and all their troubles over! She’ll forget that she taught me to write—’

Whatever Kit thought about after this, took some time to think of, for he stood gazing up the lines of shining lamps, long after the chaise had disappeared, and did not return into the house until the Notary and Mr Abel, who had themselves lingered outside till the sound of the wheels was no longer distinguishable, had several times wondered what could possibly detain him.

Commentary:

The visual immediacy of violence and low life in the novel is not limited to the appearances of Quilp. There are the slovenliness and drinking of Dick Swiveller; the monstrousness of Sally and Sampson Brass; the caricaturistic excesses of Mrs. Jarley, Codlin and Short, the gamblers, and even Kit and his mother; the weird vigor of the Marchioness; and the boisterous drinking of Nell's and her grandfather's companions on the raft. In The Old Curiosity Shop more than in any of the other novels, Phiz's illustrations — and the more noticeably so in their contrast with Cattermole's — emphasize the unruliness of the energies unleashed by Dickens' imagination. Thanks to Phiz to some extent the illustrated novel is dominated by those energies rather than by the idealizing and religious sentiments which Dickens himself evidently wished to consider the main thrust of the work.

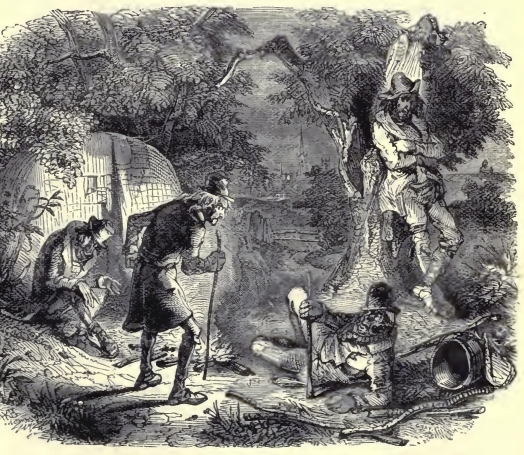

A Parley with the Cardsharpers

Chapter 42

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

But at that instant the conversation, whatever it was, which had been carrying on near this fire was resumed, and the tones of the voice that spoke—she could not distinguish words—sounded as familiar to her as her own.

She turned, and looked back. The person had been seated before, but was now in a standing posture, and leaning forward on a stick on which he rested both hands. The attitude was no less familiar to her than the tone of voice had been. It was her grandfather.

Her first impulse was to call to him; her next to wonder who his associates could be, and for what purpose they were together. Some vague apprehension succeeded, and, yielding to the strong inclination it awakened, she drew nearer to the place; not advancing across the open field, however, but creeping towards it by the hedge.

In this way she advanced within a few feet of the fire, and standing among a few young trees, could both see and hear, without much danger of being observed.

There were no women or children, as she had seen in other gipsy camps they had passed in their wayfaring, and but one gipsy—a tall athletic man, who stood with his arms folded, leaning against a tree at a little distance off, looking now at the fire, and now, under his black eyelashes, at three other men who were there, with a watchful but half-concealed interest in their conversation. Of these, her grandfather was one; the others she recognised as the first card-players at the public-house on the eventful night of the storm—the man whom they had called Isaac List, and his gruff companion. One of the low, arched gipsy-tents, common to that people, was pitched hard by, but it either was, or appeared to be, empty.

‘Well, are you going?’ said the stout man, looking up from the ground where he was lying at his ease, into her grandfather’s face. ‘You were in a mighty hurry a minute ago. Go, if you like. You’re your own master, I hope?’

‘Don’t vex him,’ returned Isaac List, who was squatting like a frog on the other side of the fire, and had so screwed himself up that he seemed to be squinting all over; ‘he didn’t mean any offence.’

‘You keep me poor, and plunder me, and make a sport and jest of me besides,’ said the old man, turning from one to the other. ‘Ye’ll drive me mad among ye.’

The utter irresolution and feebleness of the grey-haired child, contrasted with the keen and cunning looks of those in whose hands he was, smote upon the little listener’s heart. But she constrained herself to attend to all that passed, and to note each look and word.

‘Confound you, what do you mean?’ said the stout man rising a little, and supporting himself on his elbow. ‘Keep you poor! You’d keep us poor if you could, wouldn’t you? That’s the way with you whining, puny, pitiful players. When you lose, you’re martyrs; but I don’t find that when you win, you look upon the other losers in that light. As to plunder!’ cried the fellow, raising his voice—‘Damme, what do you mean by such ungentlemanly language as plunder, eh?’

Commentary:

The mode of publication — weekly instead of the usual monthly installments — with "woodcuts dropped into the text," as well as collaboration with two artists (Williams and Maclise also contributed one cut apiece to The Old Curiosity Shop.), led Dickens to new use of illustrations for the two novels which constitute the bulk of his periodical, Master Humphrey's Clock. Not only Dickens have in his service George Cattermole's Gothic, architectural talents in addition to Browne's comic, sentimental, ones, but the illustrations — more numerous and placed precisely where the novelist wanted them in the text serve to sustain certain moods and tones more extensively could two etchings per monthly part. In some respects the ones for The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge are truly integral parts of the text than any of the other illustrated Dickens' novels. The Old Curiosity Shop is about five-eighths the length of a novel like David Copperfield, while Barnaby Rudge is about three-fourths the length of such novels; but the Shop has seventy-five illustrations and Rudge seventy-six, compared with the usual forty. Thus proportionately there are two to three times as many illustrations in the weekly installments of Master Humphrey's Clock as in a monthly-parts novel. The Clock's full-size cuts are, with a few important exceptions, devoid of emblematic details. Further, in contrast to Browne's developing practice in the monthly-part novels (where he increasingly emphasizes parallels between etchings), the relation of his and Cattermole's individual cuts in the Clock is largely sequential rather than thematic.

After the necessarily halting start, given the change in plans regarding The Old Curiosity Shop, which was originally intended as a short story, the illustrations settle down into a fairly consistent pattern: two cuts per number, usually full size but sometimes one a small tailpiece, and occasionally an initial letter at the opening of a number. Early in the work the narrative and hence the graphic sequences are short, but by the fifteenth weekly number there is a six-cut sequence running through three numbers and five chapters; and from the second half of Number 19 through Number 23 a sequence of nine cuts, all by Browne, runs from chapter 24 through chapter 32. Considering that Browne was "never at home with the technique of wood cutting" because he could not envision "what changes an engraver might make in the appearance of his drawing", the frantic pace involved in illustrating a weekly rather than a monthly publication, the effect of employing various engravers, and the other work Phiz had in hand at the time, the results are of surprisingly high quality, although the engravers did seem to have trouble with facial expressions. Phiz frequently seemed to treat the medium as if he expected the results to equal those obtained by etching, but the engravers often obliged by providing as subtle shading as can be produced by the method. In this respect the results are generally more successful than those achieved by his co-illustrator. Phiz was notably more skillful than Cattermole in dealing with human figures close up, and even his worst engraver, C. Gray, could not always drag him down to his level of crudity.

Although many of Browne's early cuts for The Old Curiosity Shop are somewhat caricatured, comic portrayals of characters, his Quilp is a notable creation. Less has been said in favor of his Nell, but compared to Cattermole's, who is either a wax doll or barely visible, Browne makes us believe in the "cherry-cheeked, red-lipped" child Quilp describes so lecherously, and yet the artist never loses the pathos of Nell's situation — indeed, it could be argued that Phiz's Nell is more flesh and blood than Dickens'. Phiz seems to have transcended the rigidity of figure which characterized his virtuous females in Nicholas Nickleby.

The Old Man Stood Helplessly Among Them For A Little Time

Chapter 43

Charles Green

Text Illustrated:

‘Well, are you going?’ said the stout man, looking up from the ground where he was lying at his ease, into her grandfather’s face. ‘You were in a mighty hurry a minute ago. Go, if you like. You’re your own master, I hope?’

‘Don’t vex him,’ returned Isaac List, who was squatting like a frog on the other side of the fire, and had so screwed himself up that he seemed to be squinting all over; ‘he didn’t mean any offence.’

‘You keep me poor, and plunder me, and make a sport and jest of me besides,’ said the old man, turning from one to the other. ‘Ye’ll drive me mad among ye.’

The utter irresolution and feebleness of the grey-haired child, contrasted with the keen and cunning looks of those in whose hands he was, smote upon the little listener’s heart. But she constrained herself to attend to all that passed, and to note each look and word.

‘Confound you, what do you mean?’ said the stout man rising a little, and supporting himself on his elbow. ‘Keep you poor! You’d keep us poor if you could, wouldn’t you? That’s the way with you whining, puny, pitiful players. When you lose, you’re martyrs; but I don’t find that when you win, you look upon the other losers in that light. As to plunder!’ cried the fellow, raising his voice—‘Damme, what do you mean by such ungentlemanly language as plunder, eh?’

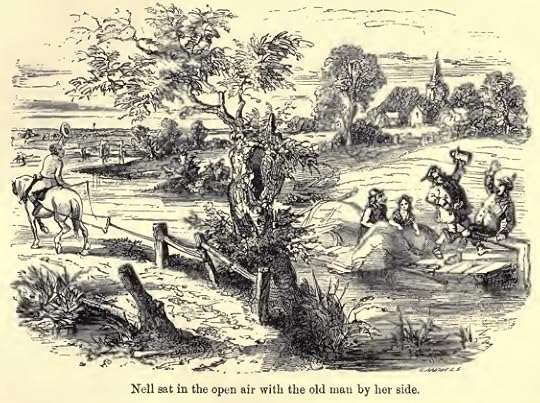

Nell sat in the open air with the old man by her side.

Chapter 43

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The sun shone pleasantly on the bright water, which was sometimes shaded by trees, and sometimes open to a wide extent of country, intersected by running streams, and rich with wooded hills, cultivated land, and sheltered farms. Now and then, a village with its modest spire, thatched roofs, and gable-ends, would peep out from among the trees; and, more than once, a distant town, with great church towers looming through its smoke, and high factories or workshops rising above the mass of houses, would come in view, and, by the length of time it lingered in the distance, show them how slowly they travelled. Their way lay, for the most part, through the low grounds, and open plains; and except these distant places, and occasionally some men working in the fields, or lounging on the bridges under which they passed, to see them creep along, nothing encroached on their monotonous and secluded track.

Nell was rather disheartened, when they stopped at a kind of wharf late in the afternoon, to learn from one of the men that they would not reach their place of destination until next day, and that, if she had no provision with her, she had better buy it there. She had but a few pence, having already bargained with them for some bread, but even of these it was necessary to be very careful, as they were on their way to an utterly strange place, with no resource whatever. A small loaf and a morsel of cheese, therefore, were all she could afford, and with these she took her place in the boat again, and, after half an hour’s delay during which the men were drinking at the public-house, proceeded on the journey.

They brought some beer and spirits into the boat with them, and what with drinking freely before, and again now, were soon in a fair way of being quarrelsome and intoxicated. Avoiding the small cabin, therefore, which was very dark and filthy, and to which they often invited both her and her grandfather, Nell sat in the open air with the old man by her side: listening to their boisterous hosts with a palpitating heart, and almost wishing herself safe on shore again though she should have to walk all night.

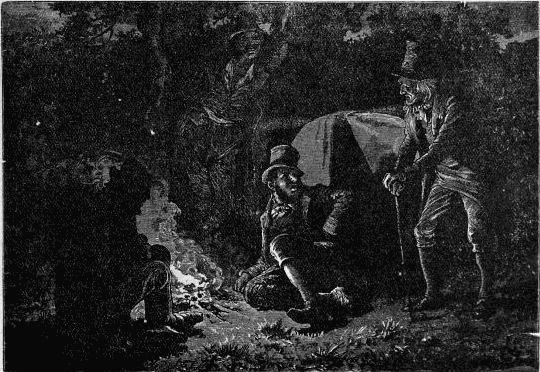

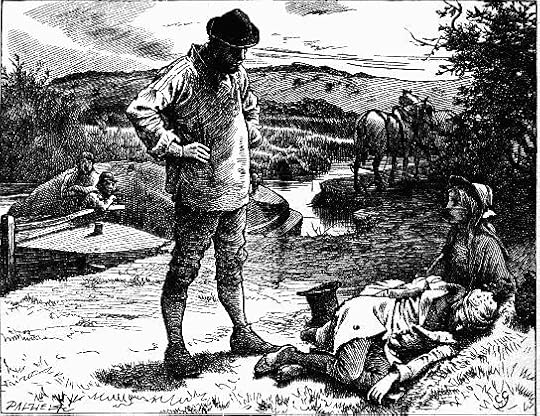

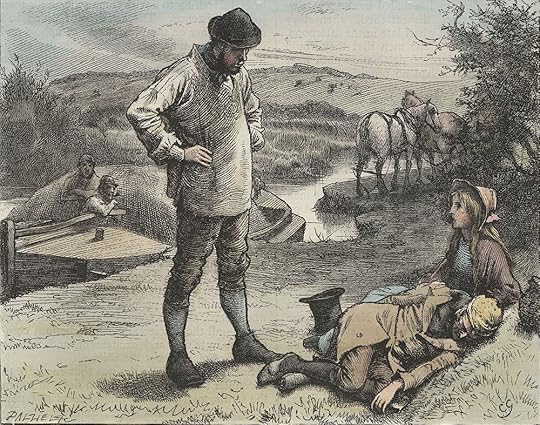

A man of very uncouth and rough appearance was standing over them.

Chapter 43

Charles Green

Text Illustrated:

The night crept on apace, the moon went down, the stars grew pale and dim, and morning, cold as they, slowly approached. Then, from behind a distant hill, the noble sun rose up, driving the mists in phantom shapes before it, and clearing the earth of their ghostly forms till darkness came again. When it had climbed higher into the sky, and there was warmth in its cheerful beams, they laid them down to sleep, upon a bank, hard by some water.

But Nell retained her grasp upon the old man’s arm, and long after he was slumbering soundly, watched him with untiring eyes. Fatigue stole over her at last; her grasp relaxed, tightened, relaxed again, and they slept side by side.

A confused sound of voices, mingling with her dreams, awoke her. A man of very uncouth and rough appearance was standing over them, and two of his companions were looking on, from a long heavy boat which had come close to the bank while they were sleeping. The boat had neither oar nor sail, but was towed by a couple of horses, who, with the rope to which they were harnessed slack and dripping in the water, were resting on the path.

‘Holloa!’ said the man roughly. ‘What’s the matter here?’

‘We were only asleep, Sir,’ said Nell. ‘We have been walking all night.’

‘A pair of queer travellers to be walking all night,’ observed the man who had first accosted them. ‘One of you is a trifle too old for that sort of work, and the other a trifle too young. Where are you going?’

Nell faltered, and pointed at hazard towards the West, upon which the man inquired if she meant a certain town which he named. Nell, to avoid more questioning, said ‘Yes, that was the place.’

‘Where have you come from?’ was the next question; and this being an easier one to answer, Nell mentioned the name of the village in which their friend the schoolmaster dwelt, as being less likely to be known to the men or to provoke further inquiry.

‘I thought somebody had been robbing and ill-using you, might be,’ said the man. ‘That’s all. Good day.’

Returning his salute and feeling greatly relieved by his departure, Nell looked after him as he mounted one of the horses, and the boat went on. It had not gone very far, when it stopped again, and she saw the men beckoning to her.

‘Did you call to me?’ said Nell, running up to them.

‘You may go with us if you like,’ replied one of those in the boat. ‘We’re going to the same place.’

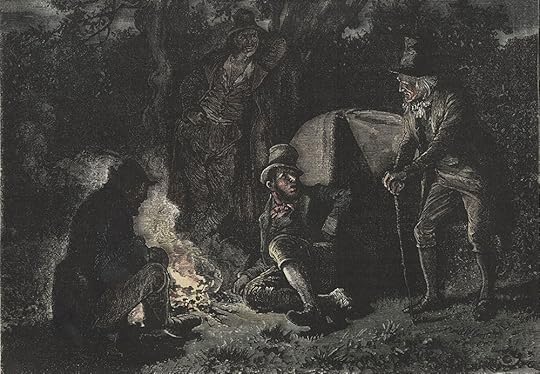

Watching the Furnace Fire

Chapter 44

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It was yet night when she awoke, nor did she know how long, or for how short a time, she had slept. But she found herself protected, both from any cold air that might find its way into the building, and from the scorching heat, by some of the workmen’s clothes; and glancing at their friend saw that he sat in exactly the same attitude, looking with a fixed earnestness of attention towards the fire, and keeping so very still that he did not even seem to breathe. She lay in the state between sleeping and waking, looking so long at his motionless figure that at length she almost feared he had died as he sat there; and softly rising and drawing close to him, ventured to whisper in his ear.

He moved, and glancing from her to the place she had lately occupied, as if to assure himself that it was really the child so near him, looked inquiringly into her face.

‘I feared you were ill,’ she said. ‘The other men are all in motion, and you are so very quiet.’

‘They leave me to myself,’ he replied. ‘They know my humour. They laugh at me, but don’t harm me in it. See yonder there—that’s my friend.’

‘The fire?’ said the child.

‘It has been alive as long as I have,’ the man made answer. ‘We talk and think together all night long.’

The child glanced quickly at him in her surprise, but he had turned his eyes in their former direction, and was musing as before.

‘It’s like a book to me,’ he said—‘the only book I ever learned to read; and many an old story it tells me. It’s music, for I should know its voice among a thousand, and there are other voices in its roar. It has its pictures too. You don’t know how many strange faces and different scenes I trace in the red-hot coals. It’s my memory, that fire, and shows me all my life.’

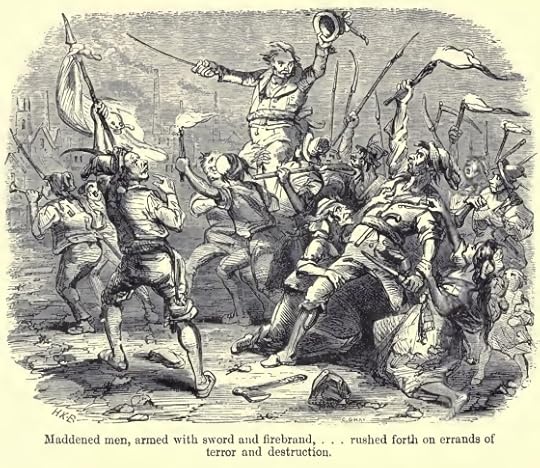

Maddened men, armed with sword and firebrand

Chapter 45

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

But night-time in this dreadful spot!—night, when the smoke was changed to fire; when every chimney spirited up its flame; and places, that had been dark vaults all day, now shone red-hot, with figures moving to and fro within their blazing jaws, and calling to one another with hoarse cries—night, when the noise of every strange machine was aggravated by the darkness; when the people near them looked wilder and more savage; when bands of unemployed labourers paraded the roads, or clustered by torch-light round their leaders, who told them, in stern language, of their wrongs, and urged them on to frightful cries and threats; when maddened men, armed with sword and firebrand, spurning the tears and prayers of women who would restrain them, rushed forth on errands of terror and destruction, to work no ruin half so surely as their own—night, when carts came rumbling by, filled with rude coffins (for contagious disease and death had been busy with the living crops); when orphans cried, and distracted women shrieked and followed in their wake—night, when some called for bread, and some for drink to drown their cares, and some with tears, and some with staggering feet, and some with bloodshot eyes, went brooding home—night, which, unlike the night that Heaven sends on earth, brought with it no peace, nor quiet, nor signs of blessed sleep—who shall tell the terrors of the night to the young wandering child!

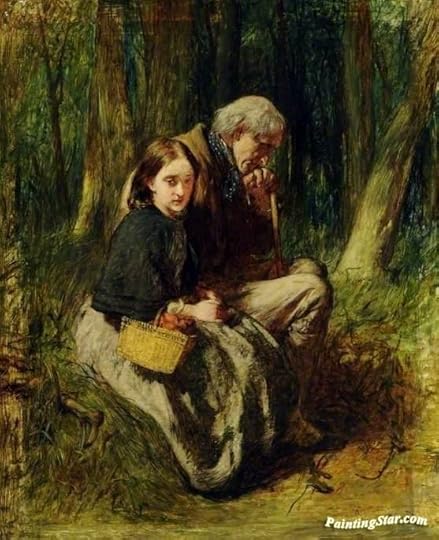

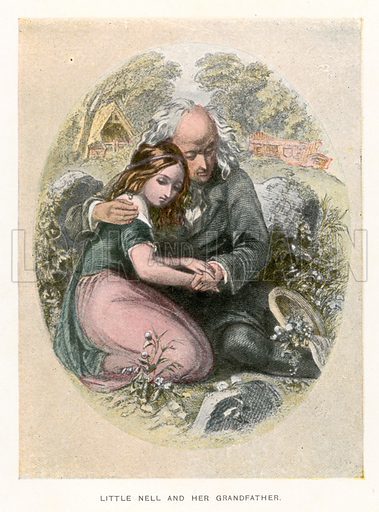

Little Nell and her grandfather

Sir William Quiller Orchardson

Commentary:

Sir William Quiller Orchardson RA was a noted Scottish portraitist and painter of domestic and historical subjects who was knighted in June 1907, at the age of 75. Orchardson was born in Edinburgh, where his father was engaged in business.

At the age of fifteen, Orchardson was sent to Edinburgh's renowned art school, the Trustees' Academy, then under the mastership of Robert Scott Lauder, where he had as fellow-students most of those who afterwards shed lustre on the Scottish school of the second half of the 19th century. As a student, he was not especially precocious or industrious, but his work was distinguished by a peculiar reserve and an unusual determination that his hand should be subdued to his eye, with the result that his early works reach their own ideal as surely as those of his maturity.

By the time he was twenty, Orchardson had mastered the essentials of his art, and had produced at least one picture which might be accepted as representative, a portrait of sculptor John Hutchison. For the seven subsequent years he worked in Edinburgh, some of his attention being given to a "black and white" style, his practice in which having been partly acquired at a sketch club, which, in addition to Hutchison, included among its members Hugh Cameron, Peter Graham, George Hay and William McTaggart.

In 1862, at the age of thirty, Orchardson moved to London, and established himself at 37 Fitzroy Square, where he was joined twelve months later by his friend John Pettie. The same house was afterwards inhabited by Ford Madox Brown. The English public was not immediately attracted to Orchardson's work. It was too quiet to compel attention at the Royal Academy, and Pettie, his junior by four years, stepped before him for a time and became the most readily accepted member of the school. Orchardson confined himself to the simplest themes and designs, to the most reticent schemes of colour. Among his most highly regarded pictures during the first eighteen years after his move to London were "The Challenge", "Christopher Sly", "Queen of the Swords", "Conditional Neutrality", "Hard Hit" - perhaps the best of all - and, within his own family, portraits of his wife and her father, Charles Moxon. In all these, good judgment and a refined imagination were united to a restrained but consummate technical dexterity. During these same years he made a few drawings on wood, turning to account his early facility in this mode.

The period between 1862 and 1880 was one of quiet ambitions, of a characteristic insouciance, of life accepted as a thing of many-balanced interests rather than as a matter of sturm und drang. In 1865 Pettie married, and the Fitzroy Square ménage was broken up. In 1868 Orchardson was elected A.R.A. (Associate of the Royal Academy). In 1870 he spent the summer in Venice, travelling home in the early autumn through a France overrun by the German armies. His marriage to Helen Moxon occurred on 6 April 1873, and in 1877 he was elected to the full membership of the Royal Academy. In this same year he finished building Ivyside, a house at Westgate-on-Sea with an open tennis-court and a studio in the garden. William Quiller Orchardson died in London two-and-a-half weeks after his 78th birthday, having been knighted less than three years previously.

Little Nell and her Grandfather

Ten Girls from Dickens, by Kate Dickinson Sweetser, Illustrated by George Alfred Williams

Little Nell Waltz - at least it's not called Little Nell and her Grandfather

English School (19th Century)

Kim wrote: "I am wondering if Nell was in perfect health when she started on this journey with her annoying grandfather, or if she was one of those Dickens characters who was already wasting away of some disea..."

Kim wrote: "I am wondering if Nell was in perfect health when she started on this journey with her annoying grandfather, or if she was one of those Dickens characters who was already wasting away of some disea..."There was a lot of emphasis on how cold and wet she got. Also I don't think she's slept well her entire life, poor kid.

Kim wrote: "Kit's mother on a journey

Chapter 41

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

To tell how Kit then hustled into the box all sorts of things which could, by no remote contingency, be wanted, and how he left out e..."

Thanks for the illustrations Kim.

This commentary summed up my feelings very well. When Phiz portrays Nell and her father there is no excessive sentimentalization. To me, the more recent illustrators turned Nell into a syrupy doll. Whose clothes would look that new, whose features would look so perfect after the ordeal she and her grandfather endured? There is no question that Dickens sentimentalized Nell more and more as the novel progresses, but Phiz is much more honest in the way her struggles have effected her.

Chapter 41

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

To tell how Kit then hustled into the box all sorts of things which could, by no remote contingency, be wanted, and how he left out e..."

Thanks for the illustrations Kim.

This commentary summed up my feelings very well. When Phiz portrays Nell and her father there is no excessive sentimentalization. To me, the more recent illustrators turned Nell into a syrupy doll. Whose clothes would look that new, whose features would look so perfect after the ordeal she and her grandfather endured? There is no question that Dickens sentimentalized Nell more and more as the novel progresses, but Phiz is much more honest in the way her struggles have effected her.

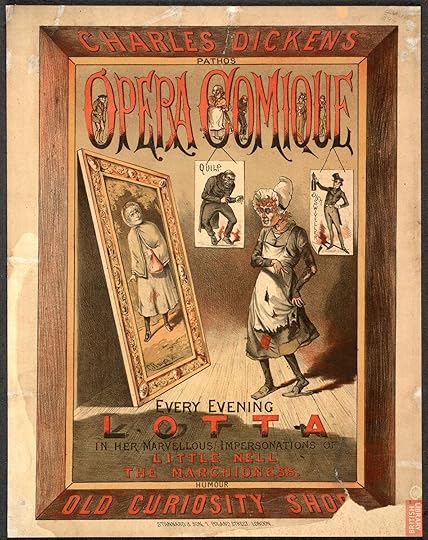

Peter wrote: "To me, the more recent illustrators turned Nell into a syrupy doll."

How's this one? I was confused when I first found it a few weeks ago, I still am.

It is on the top of an advertisement for The Old Curiosity Shop production featuring original folk music which leads me to believe it was a musical, played and sung by a "talented troupe of actor-musicians".

How's this one? I was confused when I first found it a few weeks ago, I still am.

It is on the top of an advertisement for The Old Curiosity Shop production featuring original folk music which leads me to believe it was a musical, played and sung by a "talented troupe of actor-musicians".

Kim wrote: "Peter wrote: "To me, the more recent illustrators turned Nell into a syrupy doll."

How's this one? I was confused when I first found it a few weeks ago, I still am.

It is on the top of an adver..."

Nell is so perfect in some of these illustrations she could model for Pears soap.

How's this one? I was confused when I first found it a few weeks ago, I still am.

It is on the top of an adver..."

Nell is so perfect in some of these illustrations she could model for Pears soap.

That's a good idea, I wish little Nell would have thought of it she could have supported her grandfather with her earnings.

It's really interesting how many different portrayals of Nell there are. In the one by Orchardson she almost looks middle-aged.

It's really interesting how many different portrayals of Nell there are. In the one by Orchardson she almost looks middle-aged.

Vicki wrote: "It's really interesting how many different portrayals of Nell there are. In the one by Orchardson she almost looks middle-aged."

Vicki wrote: "It's really interesting how many different portrayals of Nell there are. In the one by Orchardson she almost looks middle-aged."Yes, and in the production ad, she looks 4.

Kim wrote: "Maddened men, armed with sword and firebrand

Kim wrote: "Maddened men, armed with sword and firebrandChapter 45

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

But night-time in this dreadful spot!—night, when the smoke was changed to fire; when every chimney spirited up it..."

This one is so dramatic and so unlike the rest of OCS.

Peter wrote: "We are babysitting our grandson today and he is just beginning to walk unaided."

Peter,

That's so cool! I still remember when my two children started to walk, and how proud and excited I was when my son finally took his first steps. He was especially lazy at the time and we were already a bit worried about his reluctance to walk. A few days later, I found myself longing for the days when he would just sit around and not keep me breathless with following him about the house and the garden ;-)

Peter,