Art Lovers discussion

Open for Debate

>

Money, Ethics, Art

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Heather

(new)

May 15, 2019 09:05AM

I hope we can get some good discussion here. There are quite a few topics brought up worth noting and even about which you can state your opinion. I will post the article along with some questions, feel free to comment on my questions, or bring up a subject of your own. Let's see what kind of reaction and thoughts we have about this! This article really is fascinating!

I hope we can get some good discussion here. There are quite a few topics brought up worth noting and even about which you can state your opinion. I will post the article along with some questions, feel free to comment on my questions, or bring up a subject of your own. Let's see what kind of reaction and thoughts we have about this! This article really is fascinating!

reply

|

flag

Money, Ethics, Art: Can Museums Police Themselves?

Money, Ethics, Art: Can Museums Police Themselves?

by Holland Cotter

nytimes.com

For generations Americans tended to see art museums as alternatives to crass everyday life. Like libraries, they were for learning; like churches, for reflection. You went to them for a hit of Beauty and a lesson in “eternal values,” embodied in relics of the past donated by civic-minded angels.

You probably didn’t know — and most museums weren’t going to tell you — that many of those relics were stolen goods. Or that more than a few donor-angels were plutocrats trying to scrub their cash clean with art. Or that the values embodied in beautiful things were often, if closely examined, abhorrent.

What do you know about different art or museums or both, that have exhibited and even own art that has been stolen? Or that which was 'dirty money/art' to come clean? Does anyone have an example of something like this?

Today, we’re more alert to these ethical flaws, as several recent protests against museums show, though we still have a habit of trusting our cultural institutions, museums and universities among them, to be basically right-thinking. At moments of political crisis and moral confusion we look to them to justify our trust.

Today, we’re more alert to these ethical flaws, as several recent protests against museums show, though we still have a habit of trusting our cultural institutions, museums and universities among them, to be basically right-thinking. At moments of political crisis and moral confusion we look to them to justify our trust.How much do you 'trust' art museums? Or is this even something you would consider at all?

The 1960s was such a moment. At least early in that decade we had hopes that universities would take a principled stand on evils — war, racism — that were burning the country up. But when it became clear that our figurehead schools were, in fact, hard-wired into the machinery that fueled the conflict in Vietnam and perpetuated global apartheid, faith was shattered and has never really been restored.

The 1960s was such a moment. At least early in that decade we had hopes that universities would take a principled stand on evils — war, racism — that were burning the country up. But when it became clear that our figurehead schools were, in fact, hard-wired into the machinery that fueled the conflict in Vietnam and perpetuated global apartheid, faith was shattered and has never really been restored.At present, we’re locked in another crisis, what might be called an internal American war — on the environment, on the poor, on difference, on truth. And it’s the turn of another cultural institution, the art museum, now popular in a way it has never been, to be the object of critical scrutiny.

Example:

Example:Since early March, an activist collective called Decolonize This Place (D.T.P.) has been bringing weekly protests to the Whitney Museum of American Art. Their immediate demand is the removal of a museum trustee, Warren B. Kanders, the owner of a company, Safariland, that produces military supplies, including a brand of tear gas that has reportedly been used at the United States-Mexico border.

Reading thus far and of what you know (if anything) of Warren B Kanders, What do YOU think should be the solution? Should he step down? Should he be let go?

How do you think this current controversy will affect the attendance at the Whitney Museum of American Art?

Another example:

Another example:Another group, Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (P.A.I.N.), has, over the past year, staged disruptive events at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, protesting the acceptance of gifts of art and money from branches of the Sackler family, longtime patrons who have been identified as producers of the addictive opioid OxyContin.

Do you think they have any credence in doing this? Do they have a point? Do you think they actually value art, or just making a statement? Again, what would this protest do to the public attending these museums?

Yet another example:

Yet another example:Finally, long-existing art museum collections have been under a heightened ethical searchlight since the French president, Emmanuel Macron, proposed in 2018 that objects looted from Africa during an earlier colonial era be returned, on demand, to their places of origin — a project which, if ratified, could easily apply to a wide spectrum of Western and non-Western art.

In short, in the space of barely a year, the very foundations of museums — the money that sustains them, the art that fills them, the decision makers that run them — have been called into question. And there’s no end to questioning in sight.

In your opinion, should all art that has come into custody through unethical means be returned? This would amount to a LOT! What would this do to the art world and appreciation in general?

Recently, the American Museum of Natural History came under fire for renting out space for a dinner honoring Jair Bolsonaro, the outspokenly racist, homophobic, anti-environment president of Brazil. (The rental arrangement abruptly ended.) In late April, the Art Institute of Chicago took heat for planning a major show of culturally sensitive Native American pottery by the ancient Mimbres people — including sacred objects — without consulting indigenous communities with ties to the Mimbres people. (The show has been postponed while the museum seeks counsel from Native American nations.)

Recently, the American Museum of Natural History came under fire for renting out space for a dinner honoring Jair Bolsonaro, the outspokenly racist, homophobic, anti-environment president of Brazil. (The rental arrangement abruptly ended.) In late April, the Art Institute of Chicago took heat for planning a major show of culturally sensitive Native American pottery by the ancient Mimbres people — including sacred objects — without consulting indigenous communities with ties to the Mimbres people. (The show has been postponed while the museum seeks counsel from Native American nations.)Do you think it's fair to display "sacred objects" even as art? I agree that they would need to contact the community and get consent, first.

Politically driven museum protests are not new. In 1969, members of a collective called the Guerrilla Art Action Group gathered in the Museum of Modern Art’s lobby, drenched themselves in cow’s blood and scattered copies of a scathing manifesto titled: “A Call for the Immediate Resignation of All the Rockefellers from the Board of Trustees of the Museum of Modern Art.” It accused the brothers David Rockefeller and Nelson Rockefeller (then governor of New York) of “brutal involvement in all spheres” of the Vietnam War.

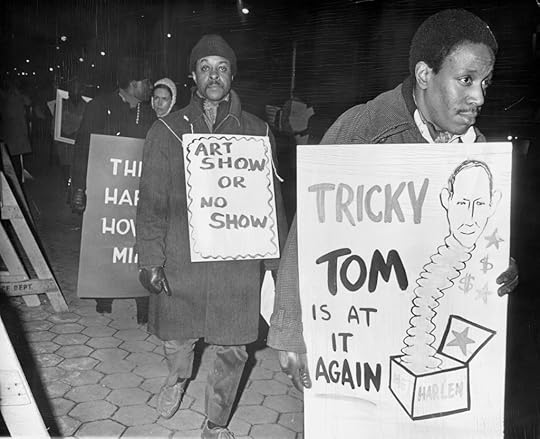

Politically driven museum protests are not new. In 1969, members of a collective called the Guerrilla Art Action Group gathered in the Museum of Modern Art’s lobby, drenched themselves in cow’s blood and scattered copies of a scathing manifesto titled: “A Call for the Immediate Resignation of All the Rockefellers from the Board of Trustees of the Museum of Modern Art.” It accused the brothers David Rockefeller and Nelson Rockefeller (then governor of New York) of “brutal involvement in all spheres” of the Vietnam War.In the same year, African-American artists, under the name Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), boycotted the Met exhibition “Harlem on My Mind.” The show was advertised as bringing African-American culture, for the first time, into the museum’s august precincts. But it included no black art or curatorial participation, and served to confirm race-based exclusion as an institutional norm.

The controversial 1969 exhibition “Harlem on My Mind” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A protest at the “Harlem on My Mind” exhibition in 1969.

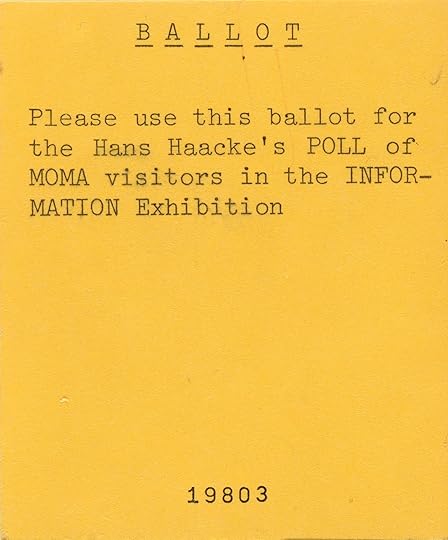

A ballot used for Hans Haacke’s “MoMA Poll.”

There’s a parallel history of protest generated from within museums, a pioneering example being Hans Haacke’s 1970 conceptual piece, “MoMA Poll.” As part of a large MoMA group exhibition, Mr. Haacke set up in a gallery two clear plastic bins, a ballot dispenser and a sign reading: “Question: Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller has not denounced President Nixon’s Indochina policy be a reason for you not to vote for him in November? Answer: “If ‘yes’ please cast your ballot into the left box. If ‘no’ into the right box.” To the museum’s consternation, and Rockefeller’s displeasure, the “yes” bin filled up fast.

Such museum-targeted work has since earned a genre name, “institutional critique,” which, problematically, has served as a marketing handle. Once critique became collectible, as it almost inevitably did, it was absorbed into, and neutralized by, the institutions it was meant to correct. (Groups like D.T.P., which call their protest work art, naturally have to be alert for such co-option.)

Such museum-targeted work has since earned a genre name, “institutional critique,” which, problematically, has served as a marketing handle. Once critique became collectible, as it almost inevitably did, it was absorbed into, and neutralized by, the institutions it was meant to correct. (Groups like D.T.P., which call their protest work art, naturally have to be alert for such co-option.)An omnivorous, sleepless market is the defining feature of the 21st-century art landscape. Money is the universal solvent. It converts everything into itself. Aesthetic value measured in dollars has, of course, always been part of the talk about art. Now it’s pretty much the whole conversation, amplified by auctions and art fairs, and directed at a population of new big-budget buyers.

Consumption is contagious, competitive, circular. Private collectors buy contemporary work of a kind museums can no longer afford. Museums, trying to attract gifts of such work, go on expansion sprees. To pay for expansions, they have to beef up their boards with rich recruits (often collectors), the source of whose fortunes are sometimes, as in the case of the Sacklers and Mr. Kanders, of a kind best left unadvertised.

With this further information about how museums may have to acquire certain high-priced pieces by having wealthy people in the board of directors, did this change your opinion about the question above whether to keep Mr. Kanders or the Sackler family on the board?

What to do about Sackler patronage became easy to decide after evidence surfaced that certain family members associated with OxyContin production had known of its addictive properties, but suppressed the information. When this news broke several museums, including the Guggenheim, quickly cut ties. (The Met, more cautious, said it was “engaging in further review of our detailed gift acceptance policies.” Its report is due later this month.) Meanwhile, the Sackler Foundation finessed the need for further debate by calling a temporary halt to new art philanthropy.

What to do about Sackler patronage became easy to decide after evidence surfaced that certain family members associated with OxyContin production had known of its addictive properties, but suppressed the information. When this news broke several museums, including the Guggenheim, quickly cut ties. (The Met, more cautious, said it was “engaging in further review of our detailed gift acceptance policies.” Its report is due later this month.) Meanwhile, the Sackler Foundation finessed the need for further debate by calling a temporary halt to new art philanthropy.

By contrast, the reaction to Mr. Macron’s proposal to restore art pilfered from Africa has varied widely, and no consensus on action has been reached. Here Western institutions are on quaking ground with, it must seem, everything but good karma to lose. No doubt many are reluctant to even consider the idea of restitution. But if justice prevails, they’ll have to. Otherwise, colonialism rolls on and on.

By contrast, the reaction to Mr. Macron’s proposal to restore art pilfered from Africa has varied widely, and no consensus on action has been reached. Here Western institutions are on quaking ground with, it must seem, everything but good karma to lose. No doubt many are reluctant to even consider the idea of restitution. But if justice prevails, they’ll have to. Otherwise, colonialism rolls on and on.

In any case, at this point, generally applicable algorithms for restitution are still unformed, though one guideline seems indisputable: that the first responsibility on the part of all concerned is to insure the safety of the fragile objects and materials under negotiation.

In any case, at this point, generally applicable algorithms for restitution are still unformed, though one guideline seems indisputable: that the first responsibility on the part of all concerned is to insure the safety of the fragile objects and materials under negotiation.Where ethical debate is in full, heated progress right now is at the Whitney. The museum’s administration has stonewalled on the issue of Mr. Kanders leaving the board, even though nearly 100 Whitney staff members, and more than half of the artists in the 2019 Biennial, which opens on May 17, have signed petitions demanding it. One Biennial artist, Michael Rakowitz, made a principled withdrawal from the show. Another participant, the artist collective called Forensic Architecture, plans to respond to the controversy with its contribution to the exhibition.

Early on, Mr. Kanders himself issued a statement of self-defense, arguing that he’s not responsible for what purchasers do with Safariland defense gear; he only makes the stuff. And the Whitney’s director, Adam Weinberg, has sent a fuzzy hug of a letter to staff. (“I write to you now as one community, one family — the Whitney.”) In the middle of which he lets himself off the executive hook: “As members of the Whitney community, we each have our critical and complementary roles: trustees do not hire staff, select exhibitions, organize programs or make acquisitions, and staff does not appoint or remove board members.” (This church-and-state separation is hardly a firm one, but never mind.)

Early on, Mr. Kanders himself issued a statement of self-defense, arguing that he’s not responsible for what purchasers do with Safariland defense gear; he only makes the stuff. And the Whitney’s director, Adam Weinberg, has sent a fuzzy hug of a letter to staff. (“I write to you now as one community, one family — the Whitney.”) In the middle of which he lets himself off the executive hook: “As members of the Whitney community, we each have our critical and complementary roles: trustees do not hire staff, select exhibitions, organize programs or make acquisitions, and staff does not appoint or remove board members.” (This church-and-state separation is hardly a firm one, but never mind.)The letter ends up being a very long way of saying “Sorry, we need Mr. Kanders’s money.”

In his letter Mr. Weinberg walks a calculated line between boosterism and selective silence. He’s right in saying that the Whitney has championed some “progressive and challenging” exhibitions, pointing to recent Zoe Leonard and David Wojnarowicz retrospectives and the Latinx group show “Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay.”

But he’s wrong in refusing to acknowledge the moral issues raised by Mr. Kanders’s résumé, and those raised by his own decision, as Whitney director, to clear the subject from the communal table, which his letter effectively does.

Mr. Kanders, for different but comparably expedient reasons, asserts a similar position of no-fault neutrality. Yet if you are in a position to support the arts, and you accept a position on the board of a museum, and it develops that your presence is disapproved of by the staff and detrimental to the reputation of the institution, isn’t it your duty to step aside until the issues in question have been, one way or another, resolved? The answer is yes. Mr. Kanders should remove himself from the board.

In the present American political climate, with nationalism and racist, ethnic, and xenophobic violence at high tide, neutrality is not an option for institutions that have ethical imperatives, represented by art, built into their DNA.

In the present American political climate, with nationalism and racist, ethnic, and xenophobic violence at high tide, neutrality is not an option for institutions that have ethical imperatives, represented by art, built into their DNA.We need these institutions, which include our art museums, to be proactive alternative environments, in which standardized power hierarchies are dissolved, a poly-cultural range of voices speak, the history of art is truthfully told, and truth itself is understood as an always-developing story.

All museums have ethical practice guidelines in place, but these can’t cover the full range of potential objections to trustee appointments (which at present include issues involving arms manufacture, corporate drug production and climate change). Surely the moral intelligence of the entire institution should be brought to bear on judging, case by case, the nature of the support being offered, with the trust that a balance of idealism and pragmatism will prevail in decision-making. And that method of assessment will succeed only when an upstairs/downstairs structuring is eliminated within the museum.

In the end, the question of Mr. Kanders’s staying or going may be less important than the discussion and protest his presence has raised, which should lead to further discussions about institutional ethics, and more protest. I believe it will.

Correction: May 12, 2019

An earlier version of this article misquoted part of a letter that the Whitney’s director, Adam Weinberg, sent to the museum’s staff. He wrote that “trustees do not hire staff, select exhibitions, organize programs or make acquisitions,” not that trustees do not “remove board members.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/09/ar...

Overall, my reaction is that these institutions must be held morally and legally responsible for the people with whom they associate. As for David Rockefeller, he was responsible for the overthrow of the democratically elected government in Indonesia in 1966. The movie THE YEAR OF LIVING DANGEROUSLY chronicles that event.

Overall, my reaction is that these institutions must be held morally and legally responsible for the people with whom they associate. As for David Rockefeller, he was responsible for the overthrow of the democratically elected government in Indonesia in 1966. The movie THE YEAR OF LIVING DANGEROUSLY chronicles that event.

Well, I agree with that to a point. I don’t know anything about the democratic overthrow in Indonesia. Did that have something to do with art? I guess I don’t see your correlation there.

Well, I agree with that to a point. I don’t know anything about the democratic overthrow in Indonesia. Did that have something to do with art? I guess I don’t see your correlation there. I don’t know how the family who produced the pharmaceutical medication OxyContin is responsible to the public who attends museums to appreciate art. How is that relevant? Is that money ‘dirty’? No, because it is prescribed by medical professionals. The problem lies with the PUBLIC abusing it to the point that it can be an ethical issue. But even then, what does that have to do with art? IMO, if the money isn’t ‘dirty’ or contrived illegally using art to ‘clean it’, I don’t see why museums can’t accept donations and financial help from wealthy patrons or members of the board of trustees.

There are reports that the OxyContin family knew full well the high risk of addiction that went with this drug, yet misrepresented it as less addictive than other painkillers. If that’s true, that is illegal.

There are reports that the OxyContin family knew full well the high risk of addiction that went with this drug, yet misrepresented it as less addictive than other painkillers. If that’s true, that is illegal.

The crimes against humanity do not stop at the US border Heather. You mentioned David Rockefeller's involvement with the Vietnam War in post #9. I am adding to that.

The crimes against humanity do not stop at the US border Heather. You mentioned David Rockefeller's involvement with the Vietnam War in post #9. I am adding to that.

Well, since I’m not familiar with Rockefeller’s involvement, I’m asking out of ignorance and curiosity. So are you saying he benefited from his involvement financially then donated that money to art museums? Is that how this is related? I know crimes don’t stop just in the US, but I’m thinking they should at least have some involvement with art, or museums, not just what they are doing in general since this whole drama is involving the museums.

Well, since I’m not familiar with Rockefeller’s involvement, I’m asking out of ignorance and curiosity. So are you saying he benefited from his involvement financially then donated that money to art museums? Is that how this is related? I know crimes don’t stop just in the US, but I’m thinking they should at least have some involvement with art, or museums, not just what they are doing in general since this whole drama is involving the museums. Now, I see Ruth’s point. That is illegal and no that money should not be accepted as donation to museums, IMO.

This is all just my opinion based on what I know only from reading articles and the news. The Vietnam war happened before I was born and I’m not as much educated in history to know all the particulars. Even Rockefeller’s involvement at all is news to me. I just don’t see the correlation with that and art or art museums UNLESS he financially benefited and took that money to donate to the museums. Maybe this is the case? I don’t know...

And I only mentioned Rockefeller’s involvement because you brought up the democratic Overthrow In Indonesia. I know absolutely nothing about that. I’d love to be enlightened! I’ll do some research on my own to try to add more educated comments here.

And I only mentioned Rockefeller’s involvement because you brought up the democratic Overthrow In Indonesia. I know absolutely nothing about that. I’d love to be enlightened! I’ll do some research on my own to try to add more educated comments here.

Does anyone have an opinion or further knowledge about Mr. Kanders’ position as a member of the board but also his involvement in creating weapons of war, particularly the tear gas that was reportedly used by the United States?

Does anyone have an opinion or further knowledge about Mr. Kanders’ position as a member of the board but also his involvement in creating weapons of war, particularly the tear gas that was reportedly used by the United States? Again, I don’t know much about the weapons that he created and that were used, and again, did the US pay him to acquire the weapons and with that money he became a prominent donor? In that way I see it directly related to museums that accepted that money and I think he should be a man and step down on his own. He is defending himself like a coward at present (unless something has changed in the last few days). Does he have other means to acquire money? Ones that do Not bring up ethical issues? Maybe a property investment or something safe from crime or ethical accusations? Does anyone know more about this? I don’t...

Regardless of whether the donor made money from an unethical enterprise and then donated the proceeds to a museum, if the person himself is involved with criminal acts then the museum should have no dealings with him.I am sure you wouldn't approve

Regardless of whether the donor made money from an unethical enterprise and then donated the proceeds to a museum, if the person himself is involved with criminal acts then the museum should have no dealings with him.I am sure you wouldn't approve of a museum accepting a contribution from Stalin

Hmmm, you have a point because no I wouldn’t approve of a donation from Stalin but I’m divided on this subject. I haven’t taken a firm stand either way. I’m learning from you and others who bring up the other side of the debate. I really don’t know how to answer that.

Hmmm, you have a point because no I wouldn’t approve of a donation from Stalin but I’m divided on this subject. I haven’t taken a firm stand either way. I’m learning from you and others who bring up the other side of the debate. I really don’t know how to answer that. I do know that the government funding to the arts is very little and they rely a lot on private donors. I am thinking of the museums as being available to the public to enjoy art! Personally, I don’t like that museums are attacked at all. But it is what it is. My opinion doesn’t make a different either way. I enjoy this commentary, though!

I don’t think there’s a one-size-fits-all answer to this. After all money is money and there’s some justification to letting ill-gotten gains do some good in the end.

I don’t think there’s a one-size-fits-all answer to this. After all money is money and there’s some justification to letting ill-gotten gains do some good in the end. But that argument can be weakened if the donor tries to exert undue influence on the receiver.

I am a strong believer in making unscrupulous super wealthys uncomfortable in life. If a person is involved in money laundering, the white salve trade, unscrupulous business practices, they should be shouldered out of the mainstream even of their uppercrest stratified society. Bar them from restaurants, civic associations, polite public. Demonstrate against their places of business and homes. Ostracize them in public. The super wealthy have had a carte blanche to the pleasures of life for too long. Kick them in the butt.s

I am a strong believer in making unscrupulous super wealthys uncomfortable in life. If a person is involved in money laundering, the white salve trade, unscrupulous business practices, they should be shouldered out of the mainstream even of their uppercrest stratified society. Bar them from restaurants, civic associations, polite public. Demonstrate against their places of business and homes. Ostracize them in public. The super wealthy have had a carte blanche to the pleasures of life for too long. Kick them in the butt.s

I agree with you there, Geoffrey...completely. I guess my thoughts and feelings don’t have a strong backing, only that I love art! I support museums because I value what they make available for us to enjoy. I feel for their lack of funding from the government but on the other hand, I don’t believe all museums are guiltless of something or another. Therefore, I understand all arguments, and I’m still undecided!

I agree with you there, Geoffrey...completely. I guess my thoughts and feelings don’t have a strong backing, only that I love art! I support museums because I value what they make available for us to enjoy. I feel for their lack of funding from the government but on the other hand, I don’t believe all museums are guiltless of something or another. Therefore, I understand all arguments, and I’m still undecided!