The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Barnaby Rudge

>

BR, Chp. 11-15

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 12 takes us to the room upstairs, thus putting us into a better position than Willet and his entourage, who must keep on guessing but are at least allowed to smoke their pipes. We witness the conference between Haredale and Chester, two men who have not seen each other for a very long time because of some sort of enmity – was it a woman perhaps? – smouldering between them. Right at the beginning of this interview, our narrator makes us aware of the contrast between the two men:

Whose side are your sympathies on?

In the course of the conversation, Mr. Chester often tries to make his guest sit down and have a glass of wine with him at least if he does not want to partake in the meal, and his speech is witty and polite, but Mr. Haredale remains standing and refuses all offers of hospitality, keeping his speech curt and contemptuous. He also says that he has ”’lost no old likings and dislikings; [his] memory has not failed [him] by a hair’s-breadth. […]’”

In contrast to this rather sombre stubbornness (as one could call a fidelity to principle in others), Mr. Chester’s philosophy may strike one as rather opportunistic and Machiavellian, as when he says,

In the course of this delightful conversation, Mr. Haredale learns about the attachment between his niece Emma and young Edward Chester, and although both elders are moved by different motives, both agree on one thing. Namely, that this attachment should have no future. Mr. Chester’s motives for putting an obstacle into his son’s way with regard to Emma is purely mercenary as he frankly confesses to Haredale: He sees it as the chief duty of his son to run away with an heiress because he has run out of money and his son is therefore responsible for providing more money. Mr. Haredale’s motives are more passionate as the following outburst shows:

He even says,

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

It is obvious that there is no love lost between those two men but that, by a somersault of chance, they now have one common goal. Who do you think has the better motives? Who do you think has more interest in their niece or son?

Mr. Chester also talks about the bonds between father and son, and he introduces his musings on this topic like this: ”’[…] I like Ned too – or, as you say, love him – that’s the word among such near relations. […]’” What can be said about a father like Mr. Chester? In what way is he similar to or different from a father like Mr. Willet? Or even Gabriel Varden?

Taking his leave, Mr. Haredale states that Chester has ”the head and heart of an evil spirit in all matters of deception”, something that does not seem to put out the other man a lot. When Willet and Barnaby, after Mr. Haredale’s departure, enter the room, expecting to find the other man dead, Mr. Chester is as complacent as ever and he even admonishes Barnaby not to forget to say his prayers when he goes to bed. Surely, this shows what a pious character Mr. Chester is, doesn’t it?

”The one was soft-spoken, delicately made, precise, and elegant; the other, a burly square-built man, negligently dressed, rough and abrupt in manner, stern, and, in his present mood, forbidding both in look and speech.”

Whose side are your sympathies on?

In the course of the conversation, Mr. Chester often tries to make his guest sit down and have a glass of wine with him at least if he does not want to partake in the meal, and his speech is witty and polite, but Mr. Haredale remains standing and refuses all offers of hospitality, keeping his speech curt and contemptuous. He also says that he has ”’lost no old likings and dislikings; [his] memory has not failed [him] by a hair’s-breadth. […]’”

In contrast to this rather sombre stubbornness (as one could call a fidelity to principle in others), Mr. Chester’s philosophy may strike one as rather opportunistic and Machiavellian, as when he says,

”’[…] The world is a lively place enough, in which we must accommodate ourselves to circumstances, sail with the stream as glibly as we can, be content to take froth for substance, the surface for the depth, the counterfeit for the real coin. I wonder no philosopher has ever established that our globe itself is hollow. It should be, if Nature is consistent in her works.’”

In the course of this delightful conversation, Mr. Haredale learns about the attachment between his niece Emma and young Edward Chester, and although both elders are moved by different motives, both agree on one thing. Namely, that this attachment should have no future. Mr. Chester’s motives for putting an obstacle into his son’s way with regard to Emma is purely mercenary as he frankly confesses to Haredale: He sees it as the chief duty of his son to run away with an heiress because he has run out of money and his son is therefore responsible for providing more money. Mr. Haredale’s motives are more passionate as the following outburst shows:

”‘I have said I love my niece. Do you think that, loving her, I would have her fling her heart away on any man who had your blood in his veins?’”

He even says,

”‘While I would restrain her from all correspondence with your son, and sever their intercourse here, though it should cause her death,’ said Mr Haredale, who had been pacing to and fro, ‘I would do it kindly and tenderly if I can. […]’”

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

It is obvious that there is no love lost between those two men but that, by a somersault of chance, they now have one common goal. Who do you think has the better motives? Who do you think has more interest in their niece or son?

Mr. Chester also talks about the bonds between father and son, and he introduces his musings on this topic like this: ”’[…] I like Ned too – or, as you say, love him – that’s the word among such near relations. […]’” What can be said about a father like Mr. Chester? In what way is he similar to or different from a father like Mr. Willet? Or even Gabriel Varden?

Taking his leave, Mr. Haredale states that Chester has ”the head and heart of an evil spirit in all matters of deception”, something that does not seem to put out the other man a lot. When Willet and Barnaby, after Mr. Haredale’s departure, enter the room, expecting to find the other man dead, Mr. Chester is as complacent as ever and he even admonishes Barnaby not to forget to say his prayers when he goes to bed. Surely, this shows what a pious character Mr. Chester is, doesn’t it?

Chapter 13 goes back in time a little, telling us of the errand that young Joseph has to run for his father, which is to see to some bills being paid in London. Obviously, the young man does not have a lot of opportunities to absent himself from home and go into London on his own, and so this annual visit to London is something special for him, which may, of course, have something to do with the prospect of seeing Dolly Varden.

Be that as it may, his journey is considerably soured for him because of the old grey mare he has to undertake it on. Although the horse is old, slow and tired, old Willet has no doubt that it is one of the finest, most powerful and graceful steeds in the Kingdom, and so there is no question as to the young man’s having to mount that steed and make for London. Once there, Joe settles his business with the vintner his father has to pay and then proceeds to what he himself regards as the main business of the journey – a visit at the Vardens’ place. Unluckily, however, the visit does not prove as delightful as he anticipated: Surely, Mr. Varden himself is friendly enough, but his daughter Dolly hardly takes any time for him because she is going to a dance and is therefore in a hurry. Instead, Joe has the doubtful pleasure of spending some time with Mrs. Varden – who is also given the flowers that were intended for Dolly, on Gabriel’s advice – and with the gamut of her different humours. To round it all off, there is also Miggs throwing in her observations from time to time, and mistress and maid master the bulk of the conversation between them.

At the end of the day, Joe leaves the locksmith’s house, incredibly crestfallen and despondent to find Dolly so ready and eager to leave his company in order to go to a party. Becoming a soldier or a sailor, nothing short of either, seems the adequate answer to this stroke of fate.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

I don’t know about you, but for me this chapter was very painful to read because I was able to fully sympathize with our Joe here. Oh, how jealousy and the feeling of humiliation must rankle in his heart!

Let us look at how old Willet provides for Joe’s journey to get our minds off Joe’s lovesickness, though. He makes him ride the grey mare, which makes him look ridiculous and prevents him from travelling fast; he does not trust him with a lot of money but has bespoken a meal for him at the Black Lion, and he also keeps him on a very tight schedule. Hardly the way to treat an adolescent young man, is it? Joe remonstrates, “’[…] Why do you use me like this? It’s not right of you. You can’t expect me to be quiet under it.’”

Another interesting detail is that our narrator underlines that old Willet stares after the horse, but not so much at her rider, for whom he has no eyes.

On his way to London, Joe stops at the Warren in order to make sure whether or not Miss Emma has any message from her to be delivered to Edward Chester. Apparently, the whole village of Chigwell is in league with the young couple against Mr. Haredale and Mr. Chester. What business is it of theirs? In the description of the Warren, we find some instances of how in Dickens a building or place can reflect its general mood or history or the characters of the people inhabiting it: ”It was a dreary, silent building, with echoing courtyards, desolated turret-chambers, and whole suites of rooms shut up and mouldering to ruin.” Strange that such a building such harbour a beautiful young woman like Emma.

I could not help but notice the little side blow given by Dickens in what he perceived as Christian zealots or hypocrites when Miggs’s whole bearing seems to say, ”I hope I know my own unworthiness, and that I hate and despise myself and all my fellow-creatures as every practicable Christian should.” Are there other examples of hypocrisy in this novel? And are there examples of true faith?

Be that as it may, his journey is considerably soured for him because of the old grey mare he has to undertake it on. Although the horse is old, slow and tired, old Willet has no doubt that it is one of the finest, most powerful and graceful steeds in the Kingdom, and so there is no question as to the young man’s having to mount that steed and make for London. Once there, Joe settles his business with the vintner his father has to pay and then proceeds to what he himself regards as the main business of the journey – a visit at the Vardens’ place. Unluckily, however, the visit does not prove as delightful as he anticipated: Surely, Mr. Varden himself is friendly enough, but his daughter Dolly hardly takes any time for him because she is going to a dance and is therefore in a hurry. Instead, Joe has the doubtful pleasure of spending some time with Mrs. Varden – who is also given the flowers that were intended for Dolly, on Gabriel’s advice – and with the gamut of her different humours. To round it all off, there is also Miggs throwing in her observations from time to time, and mistress and maid master the bulk of the conversation between them.

At the end of the day, Joe leaves the locksmith’s house, incredibly crestfallen and despondent to find Dolly so ready and eager to leave his company in order to go to a party. Becoming a soldier or a sailor, nothing short of either, seems the adequate answer to this stroke of fate.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

I don’t know about you, but for me this chapter was very painful to read because I was able to fully sympathize with our Joe here. Oh, how jealousy and the feeling of humiliation must rankle in his heart!

Let us look at how old Willet provides for Joe’s journey to get our minds off Joe’s lovesickness, though. He makes him ride the grey mare, which makes him look ridiculous and prevents him from travelling fast; he does not trust him with a lot of money but has bespoken a meal for him at the Black Lion, and he also keeps him on a very tight schedule. Hardly the way to treat an adolescent young man, is it? Joe remonstrates, “’[…] Why do you use me like this? It’s not right of you. You can’t expect me to be quiet under it.’”

Another interesting detail is that our narrator underlines that old Willet stares after the horse, but not so much at her rider, for whom he has no eyes.

On his way to London, Joe stops at the Warren in order to make sure whether or not Miss Emma has any message from her to be delivered to Edward Chester. Apparently, the whole village of Chigwell is in league with the young couple against Mr. Haredale and Mr. Chester. What business is it of theirs? In the description of the Warren, we find some instances of how in Dickens a building or place can reflect its general mood or history or the characters of the people inhabiting it: ”It was a dreary, silent building, with echoing courtyards, desolated turret-chambers, and whole suites of rooms shut up and mouldering to ruin.” Strange that such a building such harbour a beautiful young woman like Emma.

I could not help but notice the little side blow given by Dickens in what he perceived as Christian zealots or hypocrites when Miggs’s whole bearing seems to say, ”I hope I know my own unworthiness, and that I hate and despise myself and all my fellow-creatures as every practicable Christian should.” Are there other examples of hypocrisy in this novel? And are there examples of true faith?

Since Joe Willet has every reason for being sad and riding his grey mare in a hang-dog fashion, we had better not leave him alone in that perturbed mood and that is why in Chapter 14 we find ourselves gently, or ploddingly ride next to him at the pace of the grey mare. Before long, his path crosses that of another young lover, Edward Chester, who is in a far better mood, anticipating a tryst with Miss Emma. The two men continue their journey together and Edward gives Joe the kind of advice that in nine cases out of ten is the upshot of the wisdom of those with whom everything seems to go well – namely never to say die and to be sure that all will end well.

However, young Edward will soon find himself in a similar position as Joe. Similar in the way that an insurmountable obstacle seems to have been put between himself and the object of his love because when he comes to the Warren and is let into the house by a conniving servant, he has scarcely been a minute together with Emma when her uncle bursts into the room and tells him that from now on there will be no more opportunity for him to see his niece. The two men exchange high words, but at the end, Edward is forced to go, pressing the ”cold hand” of Emma to his lips.

When Joe and Edward arrive at the Maypole, Willet tells the young man that Mr. Chester is sleeping upstairs and that he had a long conversation with Mr. Haredale. Of course, this information enables Edward to realize who put Mr. Haredale on the alert, and instead of sleeping at the Maypole, the thwarted lover turns around his horse in order to ride back to London.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

First things first: Did you notice who hardly said a word in the scene between Edward and Mr. Haredale? Who stood there listening two men discuss her future and her feelings? Hearing the uncle say things like ”’[…] Your presence here is offensive to me and distressful to my niece.’” How does Mr. Haredale know, by the way, that his niece is distressed by Edward’s presence? And Eddy answers back, saying, ”’[…] you arm encircles her on whom I have set my every hope and thought […]; this house is the casket that holds the precious jewel of my existence.’ […]” – What do words like these and a situation like the one we witness tell us about Emma? Is she a woman, a jewel, a dummy? How many words has she said so far?

Apart from that, Edward is quite impertinent and manipulative. Consider the possible effect of a sentence like ”’[…] I rely upon your niece’s truth and honour, and set your influence at nought. […]’”

I found it very funny, or rather embarrassing, when Edward greeted Joe with words like ”’What gay doings have been going on to-day, Joe? Is she as pretty as ever? Nay, don’t blush, man.’” Words like these I would have resented as a liberty – not only because obviously, Joe could never talk like that to Edward because of the social difference between them, and so Edward should have proved better taste in a matter so delicate, but also because I found it surprising that Joe’s private affairs should prove such a ready-made matter for everyone to talk about, amongst each other and to Joe. Am I alone with this feeling?

However, young Edward will soon find himself in a similar position as Joe. Similar in the way that an insurmountable obstacle seems to have been put between himself and the object of his love because when he comes to the Warren and is let into the house by a conniving servant, he has scarcely been a minute together with Emma when her uncle bursts into the room and tells him that from now on there will be no more opportunity for him to see his niece. The two men exchange high words, but at the end, Edward is forced to go, pressing the ”cold hand” of Emma to his lips.

When Joe and Edward arrive at the Maypole, Willet tells the young man that Mr. Chester is sleeping upstairs and that he had a long conversation with Mr. Haredale. Of course, this information enables Edward to realize who put Mr. Haredale on the alert, and instead of sleeping at the Maypole, the thwarted lover turns around his horse in order to ride back to London.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

First things first: Did you notice who hardly said a word in the scene between Edward and Mr. Haredale? Who stood there listening two men discuss her future and her feelings? Hearing the uncle say things like ”’[…] Your presence here is offensive to me and distressful to my niece.’” How does Mr. Haredale know, by the way, that his niece is distressed by Edward’s presence? And Eddy answers back, saying, ”’[…] you arm encircles her on whom I have set my every hope and thought […]; this house is the casket that holds the precious jewel of my existence.’ […]” – What do words like these and a situation like the one we witness tell us about Emma? Is she a woman, a jewel, a dummy? How many words has she said so far?

Apart from that, Edward is quite impertinent and manipulative. Consider the possible effect of a sentence like ”’[…] I rely upon your niece’s truth and honour, and set your influence at nought. […]’”

I found it very funny, or rather embarrassing, when Edward greeted Joe with words like ”’What gay doings have been going on to-day, Joe? Is she as pretty as ever? Nay, don’t blush, man.’” Words like these I would have resented as a liberty – not only because obviously, Joe could never talk like that to Edward because of the social difference between them, and so Edward should have proved better taste in a matter so delicate, but also because I found it surprising that Joe’s private affairs should prove such a ready-made matter for everyone to talk about, amongst each other and to Joe. Am I alone with this feeling?

Chapter 15 brings the first act of our love tragedy – I’m afraid there will might be a happy ending after all – to its end, preparing the way for a complication of the conflict. On the morning following the events described in the preceding chapter, Mr. Chester is sitting in his own chambers at the Temple. We later learn that this is the former apartment of his father-in-law, the only thing he still has from his wife’s family’s former fortune. For all his financial troubles, however, he is doing justice to his breakfast and applies the ubiquitous golden toothpick, when his son arrives.

The conversation soon centres on the topic that is really at both men’s heart, and the upshot of it all is that Mr. Chester makes it very clear to Edward that he is not going to marry Emme Haredale – mainly because the woman cannot expect any great fortune, and a great fortune is what is needed to pull Mr. Chester out of his present pecuniary difficulties. Apart from that, Mr. Chester also mentions religious reasons – she being a Catholic –, but he also adds that had she but a fortune, those religious reasons would not prove an obstacle any more. He also mentions another reason, which is so grotesque and tasteless that one might assume he does it to vex his son:

Edward tries to make the best of the situation, to dissuade his father from his inexorable view on that question, and one of the things he proposes is that he will not see Emma for five years and use this time to make his way in the world in order to gain pecuniary independence for himself, Emma, and his father. At this stage, it becomes clear that Edward has from the very start been carefully prepared by his father for the aim he had in mind: Instead of teaching him a profession, e.g. preparing him for the Bar, Mr. Chester let Edward grow up in the belief that there was money enough at hand and that he could lead the life of a gentleman. The result is that Edward is now at a loss as to what to do with his life and that he depends on his father as much as his father depends on him. An interesting situation and one that brings you to the question to what extent parents should provide their children for life, turn their paths into a certain direction or let them follow their own fancies.

For the time being, it seems as though Mr. Chester is going to have it all his own way because after having had his say, he simply withdraws, leaving his son ”in a kind of stupor.”

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

Mr. Chester once again talks quite a lot in this conversation, exactly like in the interview with Mr. Haredale, and he seems to relish in presenting his views on life, his callous cynicism and lack of principle. He sometimes sounds as though he were joking, but it seems that beneath the surface of easy-going shallowness there is a heart of flint and a will of stone. – What do you make of his behaviour? Just consider the following quotation: ”‘I believe you know how very much I dislike what are called family affairs, which are only fit for plebeian Christmas days, and have no manner of business with people of our condition. […]’” Somehow, Chester’s talk reminds me of Oscar Wilde, whose writings – I must confess – I don’t like too much. There is also a lot of Machiavelli about him: ”’[E]very man has a right to live in the best way he can; and to make himself as comfortable as he can […]’”.

Once again, Mr. Chester’s abode seems to whisper of his character. Just look at this passage: ”There is yet a drowsiness in its courts, and a dreamy dulness in its trees and gardens; those who pace its lanes and squares may yet hear the echoes of their footsteps on the sounding stones, and read upon its gates, in passing from the tumult of the Strand or Fleet Street, ‘Who enters here leaves noise behind.’” I think I am not mistaken when I say that the last is an allusion to a quotation from Dante’s Divine Comedy, and that therefore Mr. Chester could be … well, after all Mr. Haredale already defined him as the evil spirit of deception.

The conversation soon centres on the topic that is really at both men’s heart, and the upshot of it all is that Mr. Chester makes it very clear to Edward that he is not going to marry Emme Haredale – mainly because the woman cannot expect any great fortune, and a great fortune is what is needed to pull Mr. Chester out of his present pecuniary difficulties. Apart from that, Mr. Chester also mentions religious reasons – she being a Catholic –, but he also adds that had she but a fortune, those religious reasons would not prove an obstacle any more. He also mentions another reason, which is so grotesque and tasteless that one might assume he does it to vex his son:

”’[…] The very idea of marrying a girl whose father was killed, like meat! Good God, Ned, how disagreeable! Consider the impossibility of having any respect for your father-in-law under such unpleasant circumstances—think of his having been “viewed” by jurors, and “sat upon” by coroners, and of his very doubtful position in the family ever afterwards. It seems to me such an indelicate sort of thing that I really think the girl ought to have been put to death by the state to prevent its happening. But I tease you perhaps. […]’”

Edward tries to make the best of the situation, to dissuade his father from his inexorable view on that question, and one of the things he proposes is that he will not see Emma for five years and use this time to make his way in the world in order to gain pecuniary independence for himself, Emma, and his father. At this stage, it becomes clear that Edward has from the very start been carefully prepared by his father for the aim he had in mind: Instead of teaching him a profession, e.g. preparing him for the Bar, Mr. Chester let Edward grow up in the belief that there was money enough at hand and that he could lead the life of a gentleman. The result is that Edward is now at a loss as to what to do with his life and that he depends on his father as much as his father depends on him. An interesting situation and one that brings you to the question to what extent parents should provide their children for life, turn their paths into a certain direction or let them follow their own fancies.

For the time being, it seems as though Mr. Chester is going to have it all his own way because after having had his say, he simply withdraws, leaving his son ”in a kind of stupor.”

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

Mr. Chester once again talks quite a lot in this conversation, exactly like in the interview with Mr. Haredale, and he seems to relish in presenting his views on life, his callous cynicism and lack of principle. He sometimes sounds as though he were joking, but it seems that beneath the surface of easy-going shallowness there is a heart of flint and a will of stone. – What do you make of his behaviour? Just consider the following quotation: ”‘I believe you know how very much I dislike what are called family affairs, which are only fit for plebeian Christmas days, and have no manner of business with people of our condition. […]’” Somehow, Chester’s talk reminds me of Oscar Wilde, whose writings – I must confess – I don’t like too much. There is also a lot of Machiavelli about him: ”’[E]very man has a right to live in the best way he can; and to make himself as comfortable as he can […]’”.

Once again, Mr. Chester’s abode seems to whisper of his character. Just look at this passage: ”There is yet a drowsiness in its courts, and a dreamy dulness in its trees and gardens; those who pace its lanes and squares may yet hear the echoes of their footsteps on the sounding stones, and read upon its gates, in passing from the tumult of the Strand or Fleet Street, ‘Who enters here leaves noise behind.’” I think I am not mistaken when I say that the last is an allusion to a quotation from Dante’s Divine Comedy, and that therefore Mr. Chester could be … well, after all Mr. Haredale already defined him as the evil spirit of deception.

Chapter 11

Chapter 11Tristram wrote: "What part might Hugh play in the course of the story?..."

Based on his description, I think he's meant to have the same effect on female readers that Dolly has on Tristram! Has anyone seen my fan?

Seriously, though -- I'm reminded of Brontë's Heathcliff, but I really hated him. I'm hoping Hugh will be a more sympathetic character for me than Heathcliff was.

Tristram wrote: "...the place where Mr. Haredale was slaughtered is still marked by a stain of blood and that no matter what pains are taken to get rid of it, it will always reappear...."

Out, damned spot! Out, I say!

Tristram wrote: "Willet also talks about education in this chapter, saying, ”What would any of us have been, if our fathers hadn’t drawed our faculties out of us?”

Probably coming from my 21st century context, I didn't read this as being about education, per se - at least not any kind of formal education, but more about the importance of fathers in their sons' lives. I think this may become an important theme in the novel. We have already seen the father and son relationship between the Willets, and will shortly see another such relationship between the Chesters. Perhaps the male Curiosities can share some insight as we go along about fathers and sons - particularly that time when sons reach the age where they need to assert their independence, and that realization that the fathers they may have looked up to as heroes are flawed.

Chapter 13

Chapter 13Tristram wrote: "I could not help but notice the little side blow given by Dickens in what he perceived as Christian zealots or hypocrites when Miggs’s whole bearing seems to say, ”I hope I know my own unworthiness, and that I hate and despise myself and all my fellow-creatures as every practicable Christian should.”..."

Once again, Tristram has stolen my thunder by extracting the quote that nearly made me choke on my tea when I read it.

Poor Joe. Adding insult to injury, the nosegay he was forced to give to Mrs. Varden not only didn't score any points with Dolly's mother, but was disposed of as so much trash. Very rude, wasn't it? At that point, Mrs. V went from what I hoped would be a humorous character to one towards whom I feel acrimonious.

And that Miggs! What a toady. They certainly do feed off one another, don't they? Poor Gabriel. No wonder he frequents the Maypole.

Dolly and Emma need to step up and redeem womanhood! We aren't portrayed in a very positive light yet in this novel.

Chapter 14

Chapter 14Did you notice who hardly said a word in the scene between Edward and Mr. Haredale?..."

This was an interesting scene. It's hard to get into Emma's head when we know so little about her, but I would venture to make a few assumptions.

First, she's female and in the 1830s/40s when this was written, a young, dependent woman didn't have much power, let alone in 1780 when this was to have taken place.

Emma's an orphan, raised by her uncle. So he's not only male, not only an authority figure (and a father figure), not only her means of support, but she also probably feels both gratitude and maybe even a little guilt that he took her in. It's no wonder that she doesn't want to defy him. He might have abandoned her, or used her badly (let's remember Ralph Nickleby and Kate!), but as far as we know he's treated her with kindness and affection 'til now.

I hesitate to go here but ... Emma, like little Nell before her, is a crier. What is with these weepy women? She wasn't calmly listening to the argument, or trying to express her own opinion (whatever that may have been) - she was sobbing through the whole thing. The arts would have us believe that men are manipulated by such behavior, but I learned early on that it doesn't work with my husband! It didn't seem to have any effect on Ned or Haredale, either.

Emma aside, what are we to make of the men? They both made some good arguments but, without some background, it's hard to know if Haredale is being rude and heartless, or if Ned is the impudent pup he's accused of being. As is often the case, the truth is probably somewhere in the middle. But the beef isn't really between these two men, is it? It all comes back to whatever caused the falling out between Haredale and Edward all those years ago. Perhaps this is as important a mystery as the one surrounding the murder?

Chapter 15

Chapter 15 Tristram wrote: "I think I am not mistaken when I say that the last is an allusion to a quotation from Dante’s Divine Comedy, and that therefore Mr. Chester could be … well, after all Mr. Haredale already defined him as the evil spirit of deception...."

I haven't read Dante, but I did get strong associations as I read this chapter. Does anyone remember the Terrible Trivium from Norton Juster's wonderful children's book, The Phantom Tollbooth? He is an elegantly dressed, polite, nonchalant, but manipulative character who has no face. When his manipulations don't work he gets angry and we see his truly demonic nature. Scared the crap out of me when I was a kid.

I can't quite place other, similar associations, but I feel as if there were movies and/or TV shows growing up in which the devil was portrayed as dapper John Steed types (from "The Avengers" - Patrick McNee with a bowler, an umbrella, and a three-piece suit, always cool as a cucumber). Are these portrayals of the devil all taken from Dante?

Do you think the gold toothpick is representative of something, or just one of those quirky, memorable characteristics that Dickens uses so effectively?

Mary Lou wrote: "Do you think the gold toothpick is representative of something, or just one of those quirky, memorable characteristics that Dickens uses so effectively?"

It being golden might hint at Mr. Chester's luxurious and costly habits, and it being a toothpick might hint at his greed and voraciousness - not literally, for he is evidently slim, but more in the sense of the lifestyle he wants to maintain with the help of his son. All in all, applying a toothpick in the presence of other people is, in my eyes, in bad taste and it shows the lack of respect Mr. Chester has for other people, doesn't it?

It being golden might hint at Mr. Chester's luxurious and costly habits, and it being a toothpick might hint at his greed and voraciousness - not literally, for he is evidently slim, but more in the sense of the lifestyle he wants to maintain with the help of his son. All in all, applying a toothpick in the presence of other people is, in my eyes, in bad taste and it shows the lack of respect Mr. Chester has for other people, doesn't it?

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 12 takes us to the room upstairs, thus putting us into a better position than Willet and his entourage, who must keep on guessing but are at least allowed to smoke their pipes. We witness t..."

The Haredale-Chester conflict promises to keep us interested for some time. Such enmity generally smoulders a long time in a Dickens novel and tends to draw many others into the same situation. For me, I’m going to throw my hat in Haredale’s corner. Chester is too smooth, too cool, too self-absorbed for my liking. He reminds me of a snake. Haredale, on the other hand, may be more blustering and rural, but he is, to me at least to this point in the novel, the more honest of the two.

So if Chester is the urban smooth-talker and Haredale the more rural squire type, and Willet senior the man living in the past while his son is more contemporary, we see some interesting dynamics and potential conflicts being set up by Dickens.

Add in the ancient feel to the Maypole, the penchant to tell stories of the past in its common room and the past begins to become even more a subtle focus of the novel’s early chapters. When we add Willit’s condescending attitude to Hugh we get lots of potential sharp edges to our tale. I feel like I’m watching a kettle slowly beginning to steam. Sooner or later it will boil: city vs country; past versus present and future; emotional attachment versus estrangement; social and character divisions rubbing against each other. Dickens is setting up his narrative very slowly but deliberately.

The Haredale-Chester conflict promises to keep us interested for some time. Such enmity generally smoulders a long time in a Dickens novel and tends to draw many others into the same situation. For me, I’m going to throw my hat in Haredale’s corner. Chester is too smooth, too cool, too self-absorbed for my liking. He reminds me of a snake. Haredale, on the other hand, may be more blustering and rural, but he is, to me at least to this point in the novel, the more honest of the two.

So if Chester is the urban smooth-talker and Haredale the more rural squire type, and Willet senior the man living in the past while his son is more contemporary, we see some interesting dynamics and potential conflicts being set up by Dickens.

Add in the ancient feel to the Maypole, the penchant to tell stories of the past in its common room and the past begins to become even more a subtle focus of the novel’s early chapters. When we add Willit’s condescending attitude to Hugh we get lots of potential sharp edges to our tale. I feel like I’m watching a kettle slowly beginning to steam. Sooner or later it will boil: city vs country; past versus present and future; emotional attachment versus estrangement; social and character divisions rubbing against each other. Dickens is setting up his narrative very slowly but deliberately.

Tristram wrote: "Since Joe Willet has every reason for being sad and riding his grey mare in a hang-dog fashion, we had better not leave him alone in that perturbed mood and that is why in Chapter 14 we find oursel..."

Love is certainly in the air in these chapters, and, being so early in the novel, we must expect complications and confusion first before any hope of a happy ending. Still, as we look back at the earlier novels, I am sensing a surer hand in Dickens. He is unfolding the lovers’ stories with some degree of pace and subtlety rather than dashing us in the face with errant emotions. The relationship between the Marchioness and Dick Swiveller was, I hope, a turning point in presenting the development of couples’ emotions towards each other. We shall see.

Love is certainly in the air in these chapters, and, being so early in the novel, we must expect complications and confusion first before any hope of a happy ending. Still, as we look back at the earlier novels, I am sensing a surer hand in Dickens. He is unfolding the lovers’ stories with some degree of pace and subtlety rather than dashing us in the face with errant emotions. The relationship between the Marchioness and Dick Swiveller was, I hope, a turning point in presenting the development of couples’ emotions towards each other. We shall see.

Tristram, when I was reading these chapters I was reminded of our first reading this book, together that is. You and Everyman disagreed on Gabriel Varden, you liked him I believe and Everyman could think of nothing good to say about him. It was so exciting because it meant for the first time one of you actually agreed with me. :-)

I feel sorry for so many characters in these chapters. Poor Gabriel for having to live with his crazy wife and Miggs. Poor Joe, because Dolly is not interested in him and his flowers went to waste. Not to mention Sim Tappertit vowed revenge on him earlier! Poor Edward, because his creepy, artificially smiling father broke him up from his sweetheart. His father is materialistic and emotionally stiff, similar to Ralph Nickleby. The devil analogy is interesting.

I feel sorry for so many characters in these chapters. Poor Gabriel for having to live with his crazy wife and Miggs. Poor Joe, because Dolly is not interested in him and his flowers went to waste. Not to mention Sim Tappertit vowed revenge on him earlier! Poor Edward, because his creepy, artificially smiling father broke him up from his sweetheart. His father is materialistic and emotionally stiff, similar to Ralph Nickleby. The devil analogy is interesting.

John Willet is the funniest character. I like how he tries hard to figure things out and apply logic, yet still comes to the wrong conclusion. It's funny too how confident he is in his wrong answers! When he said Hugh has been around animals his whole life, is more comfortable with animals than people, therefore, he *is* an animal and should be treated like one, I burst out laughing. I don't think he's a hateful man, just a bafoon trying his best to reason with limited reasoning skills.

John Willet is the funniest character. I like how he tries hard to figure things out and apply logic, yet still comes to the wrong conclusion. It's funny too how confident he is in his wrong answers! When he said Hugh has been around animals his whole life, is more comfortable with animals than people, therefore, he *is* an animal and should be treated like one, I burst out laughing. I don't think he's a hateful man, just a bafoon trying his best to reason with limited reasoning skills.Ironically, John Willet is animal-like, because he doesn't have the higher reasoning skills that we consider human. The quote about him looking at his son on a horse, but only having "eyes" for the horse is a statement of his limited animal viewpoint, I believe. He identifies more with the horse than the human! Also, he and his friends at the Maypole have herd-like behavior, because they turn their heads in unison to look at the mysterious stranger who threatens the herd.

Alissa wrote: "John Willet is the funniest character. I like how he tries hard to figure things out and apply logic, yet still comes to the wrong conclusion. It's funny too how confident he is in his wrong answer..."

Alissa

Very interesting. I never thought about the concept of herd-like behaviour and the Maypole but it does make sense. Would John be the alpha male? Now, there’s a thought. The link between characters and animals will get even more intriguing in the next weeks.

Alissa

Very interesting. I never thought about the concept of herd-like behaviour and the Maypole but it does make sense. Would John be the alpha male? Now, there’s a thought. The link between characters and animals will get even more intriguing in the next weeks.

Peter wrote: "Would John be the alpha male?"

Peter wrote: "Would John be the alpha male?"Good question. I like this line of thinking. I'd say John is alpha, since he is the owner of the Maypole, and his friends follow his lead. That makes his relationship with his son all the more interesting, because they have a power struggle going on. They clash heads, and John silences Joe to keep him in his place.

Hugh

Chapter 11

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

There were present two, however, who showed but little interest in the general contentment. Of these, one was Barnaby himself, who slept, or, to avoid being beset with questions, feigned to sleep, in the chimney-corner; the other, Hugh, who, sleeping too, lay stretched upon the bench on the opposite side, in the full glare of the blazing fire.

The light that fell upon this slumbering form, showed it in all its muscular and handsome proportions. It was that of a young man, of a hale athletic figure, and a giant’s strength, whose sunburnt face and swarthy throat, overgrown with jet black hair, might have served a painter for a model. Loosely attired, in the coarsest and roughest garb, with scraps of straw and hay—his usual bed—clinging here and there, and mingling with his uncombed locks, he had fallen asleep in a posture as careless as his dress. The negligence and disorder of the whole man, with something fierce and sullen in his features, gave him a picturesque appearance, that attracted the regards even of the Maypole customers who knew him well, and caused Long Parkes to say that Hugh looked more like a poaching rascal to-night than ever he had seen him yet.

‘He’s waiting here, I suppose,’ said Solomon, ‘to take Mr Haredale’s horse.’

‘That’s it, sir,’ replied John Willet. ‘He’s not often in the house, you know. He’s more at his ease among horses than men. I look upon him as a animal himself.’

Following up this opinion with a shrug that seemed meant to say, ‘we can’t expect everybody to be like us,’ John put his pipe into his mouth again, and smoked like one who felt his superiority over the general run of mankind.

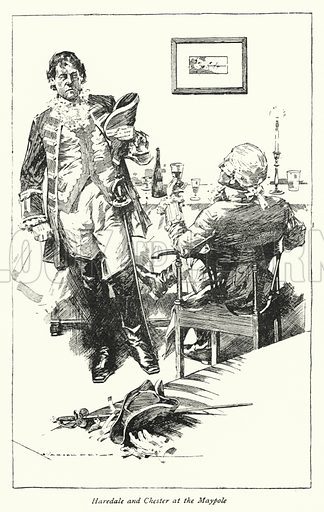

Haredale and Chester at the Maypole

Chapter 12

Max Cowper

Text Illustrated:

There was a brief pause in the state-room of the Maypole, as Mr Haredale tried the lock to satisfy himself that he had shut the door securely, and, striding up the dark chamber to where the screen inclosed a little patch of light and warmth, presented himself, abruptly and in silence, before the smiling guest.

If the two had no greater sympathy in their inward thoughts than in their outward bearing and appearance, the meeting did not seem likely to prove a very calm or pleasant one. With no great disparity between them in point of years, they were, in every other respect, as unlike and far removed from each other as two men could well be. The one was soft-spoken, delicately made, precise, and elegant; the other, a burly square-built man, negligently dressed, rough and abrupt in manner, stern, and, in his present mood, forbidding both in look and speech. The one preserved a calm and placid smile; the other, a distrustful frown. The new-comer, indeed, appeared bent on showing by his every tone and gesture his determined opposition and hostility to the man he had come to meet. The guest who received him, on the other hand, seemed to feel that the contrast between them was all in his favour, and to derive a quiet exultation from it which put him more at his ease than ever.

‘Haredale,’ said this gentleman, without the least appearance of embarrassment or reserve, ‘I am very glad to see you.’

‘Let us dispense with compliments. They are misplaced between us,’ returned the other, waving his hand, ‘and say plainly what we have to say. You have asked me to meet you. I am here. Why do we stand face to face again?’

‘Still the same frank and sturdy character, I see!’

‘Good or bad, sir, I am,’ returned the other, leaning his arm upon the chimney-piece, and turning a haughty look upon the occupant of the easy-chair, ‘the man I used to be. I have lost no old likings or dislikings; my memory has not failed me by a hair’s-breadth. You ask me to give you a meeting. I say, I am here.’

‘Our meeting, Haredale,’ said Mr Chester, tapping his snuff-box, and following with a smile the impatient gesture he had made—perhaps unconsciously—towards his sword, ‘is one of conference and peace, I hope?’

‘I have come here,’ returned the other, ‘at your desire, holding myself bound to meet you, when and where you would. I have not come to bandy pleasant speeches, or hollow professions. You are a smooth man of the world, sir, and at such play have me at a disadvantage. The very last man on this earth with whom I would enter the lists to combat with gentle compliments and masked faces, is Mr Chester, I do assure you. I am not his match at such weapons, and have reason to believe that few men are.’

‘You do me a great deal of honour Haredale,’ returned the other, most composedly, ‘and I thank you. I will be frank with you—’

‘I beg your pardon—will be what?’

‘Frank—open—perfectly candid.’

‘Hah!’ cried Mr Haredale, drawing his breath. ‘But don’t let me interrupt you.’

‘So resolved am I to hold this course,’ returned the other, tasting his wine with great deliberation; ‘that I have determined not to quarrel with you, and not to be betrayed into a warm expression or a hasty word.’

‘There again,’ said Mr Haredale, ‘you have me at a great advantage. Your self-command—’

‘Is not to be disturbed, when it will serve my purpose, you would say’—rejoined the other, interrupting him with the same complacency. ‘Granted. I allow it. And I have a purpose to serve now. So have you. I am sure our object is the same. Let us attain it like sensible men, who have ceased to be boys some time.—Do you drink?’

‘With my friends,’ returned the other.

‘At least,’ said Mr Chester, ‘you will be seated?’

‘I will stand,’ returned Mr Haredale impatiently, ‘on this dismantled, beggared hearth, and not pollute it, fallen as it is, with mockeries. Go on.’

I can find almost nothing about the artist, but what I do know is that he was born in 1860 in Dundee who was employed as an illustrator for the Dundee Courier before moving to London in 1901 to join the staff of the Illustrated London News. He died in 1911, what he did besides making beautiful paintings I don't know. Also, if the caption to the illustration didn't say Haredale and Chester I never would have thought it was them, the person I assume is supposed to be Mr. Haredale looks to me like he is wearing some sort of uniform, I don't know why he would. The person I think it is in the illustration I can't mention yet, it hasn't happened yet.

The Warren

Chapter 13

George Cattermole

Text Illustrated:

The unfortunate grey mare, who was the agony of Joe’s life, floundered along at her own will and pleasure until the Maypole was no longer visible, and then, contracting her legs into what in a puppet would have been looked upon as a clumsy and awkward imitation of a canter, mended her pace all at once, and did it of her own accord. The acquaintance with her rider’s usual mode of proceeding, which suggested this improvement in hers, impelled her likewise to turn up a bye-way, leading—not to London, but through lanes running parallel with the road they had come, and passing within a few hundred yards of the Maypole, which led finally to an inclosure surrounding a large, old, red-brick mansion—the same of which mention was made as the Warren in the first chapter of this history. Coming to a dead stop in a little copse thereabout, she suffered her rider to dismount with right goodwill, and to tie her to the trunk of a tree.

‘Stay there, old girl,’ said Joe, ‘and let us see whether there’s any little commission for me to-day.’ So saying, he left her to browze upon such stunted grass and weeds as happened to grow within the length of her tether, and passing through a wicket gate, entered the grounds on foot.

The pathway, after a very few minutes’ walking, brought him close to the house, towards which, and especially towards one particular window, he directed many covert glances. It was a dreary, silent building, with echoing courtyards, desolated turret-chambers, and whole suites of rooms shut up and mouldering to ruin.

The terrace-garden, dark with the shade of overhanging trees, had an air of melancholy that was quite oppressive. Great iron gates, disused for many years, and red with rust, drooping on their hinges and overgrown with long rank grass, seemed as though they tried to sink into the ground, and hide their fallen state among the friendly weeds. The fantastic monsters on the walls, green with age and damp, and covered here and there with moss, looked grim and desolate. There was a sombre aspect even on that part of the mansion which was inhabited and kept in good repair, that struck the beholder with a sense of sadness; of something forlorn and failing, whence cheerfulness was banished. It would have been difficult to imagine a bright fire blazing in the dull and darkened rooms, or to picture any gaiety of heart or revelry that the frowning walls shut in. It seemed a place where such things had been, but could be no more—the very ghost of a house, haunting the old spot in its old outward form, and that was all.

Much of this decayed and sombre look was attributable, no doubt, to the death of its former master, and the temper of its present occupant; but remembering the tale connected with the mansion, it seemed the very place for such a deed, and one that might have been its predestined theatre years upon years ago. Viewed with reference to this legend, the sheet of water where the steward’s body had been found appeared to wear a black and sullen character, such as no other pool might own; the bell upon the roof that had told the tale of murder to the midnight wind, became a very phantom whose voice would raise the listener’s hair on end; and every leafless bough that nodded to another, had its stealthy whispering of the crime.

Dolly Varden

Chapter 13

Leonard Raven Hill

Text Illustrated:

But he had no opportunity to say anything in his own defence, for at that moment Dolly herself appeared, and struck him quite dumb with her beauty. Never had Dolly looked so handsome as she did then, in all the glow and grace of youth, with all her charms increased a hundredfold by a most becoming dress, by a thousand little coquettish ways which nobody could assume with a better grace, and all the sparkling expectation of that accursed party. It is impossible to tell how Joe hated that party wherever it was, and all the other people who were going to it, whoever they were.

And she hardly looked at him—no, hardly looked at him. And when the chair was seen through the open door coming blundering into the workshop, she actually clapped her hands and seemed glad to go. But Joe gave her his arm—there was some comfort in that—and handed her into it. To see her seat herself inside, with her laughing eyes brighter than diamonds, and her hand—surely she had the prettiest hand in the world—on the ledge of the open window, and her little finger provokingly and pertly tilted up, as if it wondered why Joe didn’t squeeze or kiss it! To think how well one or two of the modest snowdrops would have become that delicate bodice, and how they were lying neglected outside the parlour window!

Mr. Haredale interrupts the lovers

Chapter 14

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It was a fine dry night, and the light of a young moon, which was then just rising, shed around that peace and tranquillity which gives to evening time its most delicious charm. The lengthened shadows of the trees, softened as if reflected in still water, threw their carpet on the path the travellers pursued, and the light wind stirred yet more softly than before, as though it were soothing Nature in her sleep. By little and little they ceased talking, and rode on side by side in a pleasant silence.

‘The Maypole lights are brilliant to-night,’ said Edward, as they rode along the lane from which, while the intervening trees were bare of leaves, that hostelry was visible.

‘Brilliant indeed, sir,’ returned Joe, rising in his stirrups to get a better view. ‘Lights in the large room, and a fire glimmering in the best bedchamber? Why, what company can this be for, I wonder!’

‘Some benighted horseman wending towards London, and deterred from going on to-night by the marvellous tales of my friend the highwayman, I suppose,’ said Edward.

‘He must be a horseman of good quality to have such accommodations. Your bed too, sir—!’

‘No matter, Joe. Any other room will do for me. But come—there’s nine striking. We may push on.’

They cantered forward at as brisk a pace as Joe’s charger could attain, and presently stopped in the little copse where he had left her in the morning. Edward dismounted, gave his bridle to his companion, and walked with a light step towards the house.

A female servant was waiting at a side gate in the garden-wall, and admitted him without delay. He hurried along the terrace-walk, and darted up a flight of broad steps leading into an old and gloomy hall, whose walls were ornamented with rusty suits of armour, antlers, weapons of the chase, and suchlike garniture. Here he paused, but not long; for as he looked round, as if expecting the attendant to have followed, and wondering she had not done so, a lovely girl appeared, whose dark hair next moment rested on his breast. Almost at the same instant a heavy hand was laid upon her arm, Edward felt himself thrust away, and Mr Haredale stood between them.

He regarded the young man sternly without removing his hat; with one hand clasped his niece, and with the other, in which he held his riding-whip, motioned him towards the door. The young man drew himself up, and returned his gaze.

‘This is well done of you, sir, to corrupt my servants, and enter my house unbidden and in secret, like a thief!’ said Mr Haredale. ‘Leave it, sir, and return no more.’

‘Miss Haredale’s presence,’ returned the young man, ‘and your relationship to her, give you a licence which, if you are a brave man, you will not abuse. You have compelled me to this course, and the fault is yours—not mine.’

‘It is neither generous, nor honourable, nor the act of a true man, sir,’ retorted the other, ‘to tamper with the affections of a weak, trusting girl, while you shrink, in your unworthiness, from her guardian and protector, and dare not meet the light of day. More than this I will not say to you, save that I forbid you this house, and require you to be gone.’

‘It is neither generous, nor honourable, nor the act of a true man to play the spy,’ said Edward. ‘Your words imply dishonour, and I reject them with the scorn they merit.’

‘You will find,’ said Mr Haredale, calmly, ‘your trusty go-between in waiting at the gate by which you entered. I have played no spy’s part, sir. I chanced to see you pass the gate, and followed. You might have heard me knocking for admission, had you been less swift of foot, or lingered in the garden. Please to withdraw. Your presence here is offensive to me and distressful to my niece.’ As he said these words, he passed his arm about the waist of the terrified and weeping girl, and drew her closer to him; and though the habitual severity of his manner was scarcely changed, there was yet apparent in the action an air of kindness and sympathy for her distress.

‘Mr Haredale,’ said Edward, ‘your arm encircles her on whom I have set my every hope and thought, and to purchase one minute’s happiness for whom I would gladly lay down my life; this house is the casket that holds the precious jewel of my existence. Your niece has plighted her faith to me, and I have plighted mine to her. What have I done that you should hold me in this light esteem, and give me these discourteous words?’

‘You have done that, sir,’ answered Mr Haredale, ‘which must be undone. You have tied a lover’s-knot here which must be cut asunder. Take good heed of what I say. Must. I cancel the bond between ye. I reject you, and all of your kith and kin—all the false, hollow, heartless stock.’

‘High words, sir,’ said Edward, scornfully.

‘Words of purpose and meaning, as you will find,’ replied the other. ‘Lay them to heart.’

‘Lay you then, these,’ said Edward. ‘Your cold and sullen temper, which chills every breast about you, which turns affection into fear, and changes duty into dread, has forced us on this secret course, repugnant to our nature and our wish, and far more foreign, sir, to us than you. I am not a false, a hollow, or a heartless man; the character is yours, who poorly venture on these injurious terms, against the truth, and under the shelter whereof I reminded you just now. You shall not cancel the bond between us. I will not abandon this pursuit. I rely upon your niece’s truth and honour, and set your influence at nought. I leave her with a confidence in her pure faith, which you will never weaken, and with no concern but that I do not leave her in some gentler care.’

With that, he pressed her cold hand to his lips, and once more encountering and returning Mr Haredale’s steady look, withdrew.

Mr. Haredale surprises the lovers

Chapter 14

Dudley Tennant

From Barnaby Rudge: Told to Children, by Ethel Lindsay. S.W. Partridge & Co., [1921]

Text Illustrated:

A female servant was waiting at a side gate in the garden-wall, and admitted him without delay. He hurried along the terrace-walk, and darted up a flight of broad steps leading into an old and gloomy hall, whose walls were ornamented with rusty suits of armour, antlers, weapons of the chase, and suchlike garniture. Here he paused, but not long; for as he looked round, as if expecting the attendant to have followed, and wondering she had not done so, a lovely girl appeared, whose dark hair next moment rested on his breast. Almost at the same instant a heavy hand was laid upon her arm, Edward felt himself thrust away, and Mr Haredale stood between them.

About the artist:

Charles Dudley Tennant was born in Hanley, Staffordshire, was the son of Alfred Tennant (an attorney at law) and Sarah Frances (nee Cardwell). He was Christened at Northwood, Staffordshire, on 10 January 1867. His father died in 1880 and he was later raised in Everton, Lancashire, by his widowed mother, along with his five siblings, and with whom he was still living in the early 1890s, already working as an artist and landscape painter. Later in that decade he moved to London where he met his future wife, Sarah, they were married in 1899.

Tennant became a regular illustrator for magazines, including The Girls’ Friend, The Girls’ Realm, The Graphic, The Idler, Penny Pictorial Magazine, The Royal Magazine and The Windsor Magazine. He was also a book illustrator and produced a multitude of book illustrations in colour, halftone and black and white. Many of his illustrations were for Cassell's Book of Knowledge and various encyclopedias.

On 19 July 1899, after he and Sarah Louisa Copnall were married, they moved from 30 Gloucester Road , Regents Park, to Aberdeen Villas, Chase Road, Southgate in the period 1900-03. He later moved to Surrey where he died in 1952, aged 86.

He exhibited at the Royal Academy and the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool between 1898 and 1918. He is listed in The Dictionary of British Artists. His son, Dudley Trevor Tennant (1900-1980), was a sculptor and teacher.

From about 1913 he lived in Purley, Surrey, where he died in 1952 at the age of 86.

Mr. Chester takes his ease at the inn

Chapter 15

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It was in a room in Paper Buildings—a row of goodly tenements, shaded in front by ancient trees, and looking, at the back, upon the Temple Gardens—that this, our idler, lounged; now taking up again the paper he had laid down a hundred times; now trifling with the fragments of his meal; now pulling forth his golden toothpick, and glancing leisurely about the room, or out at window into the trim garden walks, where a few early loiterers were already pacing to and fro. Here a pair of lovers met to quarrel and make up; there a dark-eyed nursery-maid had better eyes for Templars than her charge; on this hand an ancient spinster, with her lapdog in a string, regarded both enormities with scornful sidelong looks; on that a weazen old gentleman, ogling the nursery-maid, looked with like scorn upon the spinster, and wondered she didn’t know she was no longer young. Apart from all these, on the river’s margin two or three couple of business-talkers walked slowly up and down in earnest conversation; and one young man sat thoughtfully on a bench, alone.

‘Ned is amazingly patient!’ said Mr Chester, glancing at this last-named person as he set down his teacup and plied the golden toothpick, ‘immensely patient! He was sitting yonder when I began to dress, and has scarcely changed his posture since. A most eccentric dog!’

I loved this line from Chapter 11, it is so true:

For a little knot of smokers and solemn gossips, who had seldom any new topics of discussion, this was a perfect Godsend.

Yes, having Haredale come and visit Mr. Chester will give them plenty to talk about. We have a small group of senior citizens who seem to meet at our local McDonald's - - they meet there every day of every week. That's how it seems, no matter what time you go by the place there they sit, and for a long, long time I've been wondering what they find to talk about for hours day after day. So I can see how a duel would be a pleasant change from the usual talk. But in the Maypole's case what does their gossiping come up with?

‘Willet,’ said Solomon Daisy, who had exhibited some impatience at the intrusion of so unworthy a subject on their more interesting theme, ‘when Mr Chester come this morning, did he order the large room?’

‘He signified, sir,’ said John, ‘that he wanted a large apartment. Yes. Certainly.’

‘Why then, I’ll tell you what,’ said Solomon, speaking softly and with an earnest look. ‘He and Mr Haredale are going to fight a duel in it.’

Everybody looked at Mr Willet, after this alarming suggestion. Mr Willet looked at the fire, weighing in his own mind the effect which such an occurrence would be likely to have on the establishment.

‘Well,’ said John, ‘I don’t know—I am sure—I remember that when I went up last, he HAD put the lights upon the mantel-shelf.’

‘It’s as plain,’ returned Solomon, ‘as the nose on Parkes’s face’—Mr Parkes, who had a large nose, rubbed it, and looked as if he considered this a personal allusion—‘they’ll fight in that room. You know by the newspapers what a common thing it is for gentlemen to fight in coffee-houses without seconds. One of ‘em will be wounded or perhaps killed in this house.’

‘That was a challenge that Barnaby took then, eh?’ said John.

‘—Inclosing a slip of paper with the measure of his sword upon it, I’ll bet a guinea,’ answered the little man. ‘We know what sort of gentleman Mr Haredale is. You have told us what Barnaby said about his looks, when he came back. Depend upon it, I’m right. Now, mind.’

The flip had had no flavour till now. The tobacco had been of mere English growth, compared with its present taste. A duel in that great old rambling room upstairs, and the best bed ordered already for the wounded man!

And then after having discussed the event so much, coming up with plans as to what will happen, and they are quite disappointed to find that no one has been murdered after all. Gossip isn't as fun if nothing comes of it.

John Willet and his friends, who had been listening intently for the clash of swords, or firing of pistols in the great room, and had indeed settled the order in which they should rush in when summoned—in which procession old John had carefully arranged that he should bring up the rear—were very much astonished to see Mr Haredale come down without a scratch, call for his horse, and ride away thoughtfully at a footpace. After some consideration, it was decided that he had left the gentleman above, for dead, and had adopted this stratagem to divert suspicion or pursuit.

I wonder if sitting in the Maypole all day was as interesting as sitting at McDonald's seems to be now.

For a little knot of smokers and solemn gossips, who had seldom any new topics of discussion, this was a perfect Godsend.

Yes, having Haredale come and visit Mr. Chester will give them plenty to talk about. We have a small group of senior citizens who seem to meet at our local McDonald's - - they meet there every day of every week. That's how it seems, no matter what time you go by the place there they sit, and for a long, long time I've been wondering what they find to talk about for hours day after day. So I can see how a duel would be a pleasant change from the usual talk. But in the Maypole's case what does their gossiping come up with?

‘Willet,’ said Solomon Daisy, who had exhibited some impatience at the intrusion of so unworthy a subject on their more interesting theme, ‘when Mr Chester come this morning, did he order the large room?’

‘He signified, sir,’ said John, ‘that he wanted a large apartment. Yes. Certainly.’

‘Why then, I’ll tell you what,’ said Solomon, speaking softly and with an earnest look. ‘He and Mr Haredale are going to fight a duel in it.’

Everybody looked at Mr Willet, after this alarming suggestion. Mr Willet looked at the fire, weighing in his own mind the effect which such an occurrence would be likely to have on the establishment.

‘Well,’ said John, ‘I don’t know—I am sure—I remember that when I went up last, he HAD put the lights upon the mantel-shelf.’

‘It’s as plain,’ returned Solomon, ‘as the nose on Parkes’s face’—Mr Parkes, who had a large nose, rubbed it, and looked as if he considered this a personal allusion—‘they’ll fight in that room. You know by the newspapers what a common thing it is for gentlemen to fight in coffee-houses without seconds. One of ‘em will be wounded or perhaps killed in this house.’

‘That was a challenge that Barnaby took then, eh?’ said John.

‘—Inclosing a slip of paper with the measure of his sword upon it, I’ll bet a guinea,’ answered the little man. ‘We know what sort of gentleman Mr Haredale is. You have told us what Barnaby said about his looks, when he came back. Depend upon it, I’m right. Now, mind.’

The flip had had no flavour till now. The tobacco had been of mere English growth, compared with its present taste. A duel in that great old rambling room upstairs, and the best bed ordered already for the wounded man!

And then after having discussed the event so much, coming up with plans as to what will happen, and they are quite disappointed to find that no one has been murdered after all. Gossip isn't as fun if nothing comes of it.

John Willet and his friends, who had been listening intently for the clash of swords, or firing of pistols in the great room, and had indeed settled the order in which they should rush in when summoned—in which procession old John had carefully arranged that he should bring up the rear—were very much astonished to see Mr Haredale come down without a scratch, call for his horse, and ride away thoughtfully at a footpace. After some consideration, it was decided that he had left the gentleman above, for dead, and had adopted this stratagem to divert suspicion or pursuit.

I wonder if sitting in the Maypole all day was as interesting as sitting at McDonald's seems to be now.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 15 brings the first act of our love tragedy – I’m afraid there will might be a happy ending after all – to its end, preparing the way for a complication of the conflict. On the morning foll..."

Tristram

I agree with you about Chester. He is like Oscar Wilde. Chester is so smooth, so cynical, so removed from the common rhythm of social interactions it makes me shiver. We have not met his match in any Dickens novel so far. Perhaps Ralph Nickleby has a similar lack of moral compass, but Chester is so much more unattached to society and its morals. Chilling.

Tristram

I agree with you about Chester. He is like Oscar Wilde. Chester is so smooth, so cynical, so removed from the common rhythm of social interactions it makes me shiver. We have not met his match in any Dickens novel so far. Perhaps Ralph Nickleby has a similar lack of moral compass, but Chester is so much more unattached to society and its morals. Chilling.

Kim wrote: "...after having discussed the event so much, coming up with plans as to what will happen, and they are quite disappointed to find that no one has been murdered after all. Gossip isn't as fun if nothing comes of it...."

Kim wrote: "...after having discussed the event so much, coming up with plans as to what will happen, and they are quite disappointed to find that no one has been murdered after all. Gossip isn't as fun if nothing comes of it...."But not knowing exactly what transpired will give them fodder for speculation that will serve them for some time to come. :-)

Kim wrote: "And here is Kyd's idea of Dolly"

Kim wrote: "And here is Kyd's idea of Dolly"I guess she's just smiling, but for several moments I could have sworn she had a mustache.

THAT would surely show through Tristram's rose-colored glasses!

Kim wrote: "Tristram, when I was reading these chapters I was reminded of our first reading this book, together that is. You and Everyman disagreed on Gabriel Varden, you liked him I believe and Everyman could..."

And which one of us was it? I also think that E-man and I held different views on Dolly - can you believe it?

And which one of us was it? I also think that E-man and I held different views on Dolly - can you believe it?

Kim wrote: "And here is Kyd's idea of Dolly

"

Kyd's idea on Dolly and mine are oddly at variance, I must say ;-)

"

Kyd's idea on Dolly and mine are oddly at variance, I must say ;-)

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 15 brings the first act of our love tragedy – I’m afraid there will might be a happy ending after all – to its end, preparing the way for a complication of the conflict. On..."

If there is another villain in the Dickens universe, I'd see as similar to Chester, it would be Carker, from Dombey and Son, but Carker is far less prominent in the course of the novel. He acts in the background and is more humble on the outside. Then there is Eugene Wrayburn, who is quite as much of a dandy as Mr. Chester, but probably has more moral substance - it's only a matter of rising it into life.

If there is another villain in the Dickens universe, I'd see as similar to Chester, it would be Carker, from Dombey and Son, but Carker is far less prominent in the course of the novel. He acts in the background and is more humble on the outside. Then there is Eugene Wrayburn, who is quite as much of a dandy as Mr. Chester, but probably has more moral substance - it's only a matter of rising it into life.

Kim wrote: "I loved this line from Chapter 11, it is so true:

For a little knot of smokers and solemn gossips, who had seldom any new topics of discussion, this was a perfect Godsend.

Yes, having Haredale co..."

Kim,

I must say that the old men talking at MacDonald's all day long are quite a rare sight nowadays. In our day and age, it's usually people sitting at the same table with each other but not interacting; instead everyone is busy manipulated, or being manipulated by, their smartphone ;-) So, a cheer to those old men!

At an age where there were no digital gadgets to keep people entertained, and when there was no TV, sitting at the chimney in an inn and waiting for a duel to occur must have been one of the few ways of preserving one's sanity ;-)

For a little knot of smokers and solemn gossips, who had seldom any new topics of discussion, this was a perfect Godsend.

Yes, having Haredale co..."

Kim,

I must say that the old men talking at MacDonald's all day long are quite a rare sight nowadays. In our day and age, it's usually people sitting at the same table with each other but not interacting; instead everyone is busy manipulated, or being manipulated by, their smartphone ;-) So, a cheer to those old men!

At an age where there were no digital gadgets to keep people entertained, and when there was no TV, sitting at the chimney in an inn and waiting for a duel to occur must have been one of the few ways of preserving one's sanity ;-)

Alissa wrote: "I feel sorry for so many characters in these chapters. Poor Gabriel for having to live with his crazy wife and Miggs. Poor Joe, because Dolly is not interested in him and his flowers went to waste...."

Alissa wrote: "I feel sorry for so many characters in these chapters. Poor Gabriel for having to live with his crazy wife and Miggs. Poor Joe, because Dolly is not interested in him and his flowers went to waste...."I am wondering if Dolly is truly not interested in Joe or just pretending not to be. I got the impression that she was very interested when Joe entered into that first breakfast conversation between her father and Sim and herself. Even Sim was jealous of Joe after that conversation. So, why she appeared to be so disinterested at this point, I don't know.

Tristram wrote: "Kim wrote: "I loved this line from Chapter 11, it is so true:

Tristram wrote: "Kim wrote: "I loved this line from Chapter 11, it is so true:For a little knot of smokers and solemn gossips, who had seldom any new topics of discussion, this was a perfect Godsend.

Yes, having..."

This reminds me of the men sitting on the front porch of my grandfather's little country store in Mississippi chatting and playing checkers with bottle caps. What a fun memory, so glad to have thought of that again.

Kim wrote: "The Warren

Chapter 13

George Cattermole

Text Illustrated:

The unfortunate grey mare, who was the agony of Joe’s life, floundered along at her own will and pleasure until the Maypole was no long..."

The description of the Warren and the illustration of it so hidden by trees and vegetation certainly create the feeling of a musty, old, forgotten and neglected place, one suspended in time, or worse, one almost forgotten by time.

Dickens often constructs his narratives around opposites, contradictory feelings, and binary relationships. In the rural settings of this novel the Maypole Inn and the Warren seem held in the past. In contrast, there is much bustle, activity, and energy swirling in the urban setting of London.

Are there storm clouds on the horizon?

Chapter 13

George Cattermole

Text Illustrated:

The unfortunate grey mare, who was the agony of Joe’s life, floundered along at her own will and pleasure until the Maypole was no long..."

The description of the Warren and the illustration of it so hidden by trees and vegetation certainly create the feeling of a musty, old, forgotten and neglected place, one suspended in time, or worse, one almost forgotten by time.

Dickens often constructs his narratives around opposites, contradictory feelings, and binary relationships. In the rural settings of this novel the Maypole Inn and the Warren seem held in the past. In contrast, there is much bustle, activity, and energy swirling in the urban setting of London.

Are there storm clouds on the horizon?

Bobbie wrote: "Alissa wrote: "I feel sorry for so many characters in these chapters. Poor Gabriel for having to live with his crazy wife and Miggs. Poor Joe, because Dolly is not interested in him and his flowers..."

Maybe, Dolly is a little bit, just a tiny little bit, subject to moods and changes of opinion. Just look at her mother, who can run through all sorts of temper in half an hour :-)

Maybe, Dolly is a little bit, just a tiny little bit, subject to moods and changes of opinion. Just look at her mother, who can run through all sorts of temper in half an hour :-)

Tristram wrote: "Maybe, Dolly is a little bit, just a tiny little bit, subject to moods and changes of opinion. Just look at her mother, who can run through all sorts of temper in half an hour :-)"

Tristram wrote: "Maybe, Dolly is a little bit, just a tiny little bit, subject to moods and changes of opinion. Just look at her mother, who can run through all sorts of temper in half an hour :-)"For Joe's sake, and the reader's, I hope not.

I couldn't tell whether she was distracted or playing hard to get, maybe because the chapter was from Joe's perspective and he can't sort out anything about her at all, except that he likes her.