The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Barnaby Rudge

Barnaby Rudge

>

BR, Chp. 21-25

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 22 sees the Vardens off the Maypole, with Joe riding next to the coach, in a state of bliss despite the disturbing events that have taken place.

What does this show about Dolly? In the morning of that day, her mind – or heart? – was still quite preoccupied by that coach-builder she met at the dance, and now all this seems to be forgotten over Joe. A consequence of all the excitement she went through, or were there signs before that implied that Joe, after all, is not a person she feels completely indifferent to? While we are still talking and musing about Dolly, let me ask you a question: Which of the two do you find more realistic, life-like and three-dimensional as a character – Dolly or Emma?

Okay, it seems that Joe is never granted any longer spell of satisfaction and happiness, and therefore, it’s high time for Hugh to appear in order to spoil it all, which he does, saying that John Willet sent him to see his son home – another humiliation for Joe, who must now look like a young boy unable to look after himself. Be that as it may, Mrs. Varden eventually makes an end of it by insisting, in her own charming manner, that Joe return to the Maypole and leave them pursue their journey alone.

Back at home, the Vardens are already eagerly awaited, by Miggs, and, maybe less eagerly, by Mr. Tappertit. As usual, Mrs. Varden uses their return home in order to create a scene and to prove to herself and her lickspittle Miggs that among all people she is the main sufferer and consequently the one to be pitied and admired most. Even though Dolly may have been the victim of a highwayman disguised as a beggar, it is, of course, Mrs. Varden who suffers most from that situation, let her daughter swoon as much as she wants.

Later, Miggs treats herself to a special little jibe when she pretends to bring Simon his meal only to fuel his jealousy with regard to Joe, which she does by telling him about Dolly’s adventure and harping on Joe’s part in it. Interestingly, she talks, not of one highwayman, but of ”’three or four tall men, who would have certainly borne her away and perhaps murdered her, but for the timely arrival of Joseph Willet, who with his own single hand put them all to flight, and rescued her; to the lasting admiration of his fellow-creatures generally, and to the eternal love and gratitude of Dolly Varden.’” Who made four men out of one? Was it Miggs, in order to increase the apprentice’s rancour? Or was it the person who told Miggs? – Be that as it may, the result is exactly as the maid might have predicted: Simon does not receive the news in too good spirits, and he does not exactly warm up towards Joe, but rather flare up.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

What might Dickens’s reason have been for allowing us another glimpse into the domestic scene of the Vardens? Do you still enjoy Mrs. Varden’s hysterics, or are they staring to tire you out? – Can we assume that the rivalry between Simon Tappertit and Joe Willet will play a special part in the course of this novel? If so, let’s not forget that there is another man who shows interest – to put it neutrally – in Dolly. How is it all going to end?

Can you imagine how worried Dolly must feel with regard to Joe, her last view of the young man being ”as he […] lingered on the spot where they had parted, with the tall dark figure of Hugh beside him.” That would be a marvellous scene in a movie, I’d say but it also implies that from now on, Hugh will be “a tall dark figure” overshadowing the unsuspecting Joe. What could Dolly do to prevent more harm from happening?

”The road was a very good one; not at all a jolting road, or an uneven one; and yet Dolly held the side of the chaise with one little hand, all the way. If there had been an executioner behind him with an uplifted axe ready to chop off his head if he touched that hand, Joe couldn’t have helped doing it. From putting his own hand upon it as if by chance, and taking it away again after a minute or so, he got to riding along without taking it off at all; as if he, the escort, were bound to do that as an important part of his duty, and had come out for the purpose. The most curious circumstance about this little incident was, that Dolly didn’t seem to know of it. She looked so innocent and unconscious when she turned her eyes on Joe, that it was quite provoking.”

What does this show about Dolly? In the morning of that day, her mind – or heart? – was still quite preoccupied by that coach-builder she met at the dance, and now all this seems to be forgotten over Joe. A consequence of all the excitement she went through, or were there signs before that implied that Joe, after all, is not a person she feels completely indifferent to? While we are still talking and musing about Dolly, let me ask you a question: Which of the two do you find more realistic, life-like and three-dimensional as a character – Dolly or Emma?

Okay, it seems that Joe is never granted any longer spell of satisfaction and happiness, and therefore, it’s high time for Hugh to appear in order to spoil it all, which he does, saying that John Willet sent him to see his son home – another humiliation for Joe, who must now look like a young boy unable to look after himself. Be that as it may, Mrs. Varden eventually makes an end of it by insisting, in her own charming manner, that Joe return to the Maypole and leave them pursue their journey alone.

Back at home, the Vardens are already eagerly awaited, by Miggs, and, maybe less eagerly, by Mr. Tappertit. As usual, Mrs. Varden uses their return home in order to create a scene and to prove to herself and her lickspittle Miggs that among all people she is the main sufferer and consequently the one to be pitied and admired most. Even though Dolly may have been the victim of a highwayman disguised as a beggar, it is, of course, Mrs. Varden who suffers most from that situation, let her daughter swoon as much as she wants.

Later, Miggs treats herself to a special little jibe when she pretends to bring Simon his meal only to fuel his jealousy with regard to Joe, which she does by telling him about Dolly’s adventure and harping on Joe’s part in it. Interestingly, she talks, not of one highwayman, but of ”’three or four tall men, who would have certainly borne her away and perhaps murdered her, but for the timely arrival of Joseph Willet, who with his own single hand put them all to flight, and rescued her; to the lasting admiration of his fellow-creatures generally, and to the eternal love and gratitude of Dolly Varden.’” Who made four men out of one? Was it Miggs, in order to increase the apprentice’s rancour? Or was it the person who told Miggs? – Be that as it may, the result is exactly as the maid might have predicted: Simon does not receive the news in too good spirits, and he does not exactly warm up towards Joe, but rather flare up.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

What might Dickens’s reason have been for allowing us another glimpse into the domestic scene of the Vardens? Do you still enjoy Mrs. Varden’s hysterics, or are they staring to tire you out? – Can we assume that the rivalry between Simon Tappertit and Joe Willet will play a special part in the course of this novel? If so, let’s not forget that there is another man who shows interest – to put it neutrally – in Dolly. How is it all going to end?

Can you imagine how worried Dolly must feel with regard to Joe, her last view of the young man being ”as he […] lingered on the spot where they had parted, with the tall dark figure of Hugh beside him.” That would be a marvellous scene in a movie, I’d say but it also implies that from now on, Hugh will be “a tall dark figure” overshadowing the unsuspecting Joe. What could Dolly do to prevent more harm from happening?

Leaving the comparatively peaceful and harmonious household of the Vardens, we are going to fling ourselves on the back of Chapter 23 and are led once more into the presence of Mr. Chester. The chapter already starts on not too promising a note:

Clearly, Mr. Chester, as a representative of a class of people our narrator does not feel too partial to, is associated with night and darkness, but also with narrowness. What do you make of all this?

Let’s see what is going to happen, though! Mr. Chester is preparing to go out, but is doing so in his own leisurely way, reading a book from which he derives uncommon enjoyment. Before long, though, a visitor is announced, and although at first, the host shows no great inclination to receive anyone, this changes when the newcomer sends in Mr. Chester’s riding crop, which he has forgotten at the Maypole. It is clear that the riding crop is a code with the help of which the visitor – none other but Hugh – can ensure access to Mr. Chester. As Mr. Chester is the inventor of this code, he has probably seen fit to make Hugh his ally, or rather tool, and in a few minutes we will learn for what reason. At first, Hugh seems to dominate the scene with his wildness, his bravado and his loud speech, drinking freely from the host’s alcohol, but by and by, it becomes more and more obvious that Mr. Chester has the rough ostler under his thumb. Hugh hands Chester the letter from Emma, which he has taken from Dolly, and Mr. Chester, after reading the letter, burns it. Chester also knows that Hugh has taken the bracelet, and not only the letter, and with the help of this knowledge, he cows Hugh completely – all the more so, since Hugh has the bracelet in his pocket – by implying that he could easily turn Hugh in for a thief to the authorities. When he has established his ascendancy over Hugh, he states that as long as Hugh proves useful to Chester, he will always remain his friend and patron. This may be seen and understood as a promise but implicitly, it is, of course, also a deadly threat. Hugh may treat himself to one more glass or two but he finally has to see that he is but a tool in the hands of Mr. Chester.

QUESTIONS AND THOUGHTS

At the beginning of the chapter, Mr. Chester is reading a book by Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Lord of Chesterfield, called Letters to His Son on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman (1774). This collection of letters gives political and diplomatic advice on how to get on in a world of courtiers, and it is therefore quite Machiavellian in tone. Samuel Johnson wrote about these letters that they “teach the morals of a whore, and the manners of a dancing-master”. Mr. Chester, however, is more delighted with these letters and with Lord Chesterfield as such, than stuffy old Johnson. He openly praises the book to himself in words like:

What does this show about his person, and does this maybe refer to something beyond his person, something he is a representative of? What is your impression of Mr. Chester so frankly extolling his own crookedness?

Although he lives in a completely different world from Hugh, Mr. Chester instinctively knows how to impress and get the better of that rough customer. Being used to hard words from Willet and the like, ”this cool, complacent, contemptuous, self-possessed reception, caused him [i.e. Hugh] to feel his inferiority more completely than the most elaborate arguments.” What other ways and tricks does Mr. Chester have at his disposal in order to gain mastery over Hugh? And what could be his ulterior motive in doing so? Does this simply happen with a view of hindering any correspondence between his son and Emma?

Some more thoughts about Hugh: When he is offered some spirits, Hugh says,

About the dog he has with him:

About his mother:

Those three quotations tell us a lot about Hugh, and maybe also about the narrator’s intentions connected with this character. What are your ideas?

”Twilight had given place to night some hours, and it was high noon in those quarters of the town in which ‘the world’ condescended to dwell—the world being then, as now, of very limited dimensions and easily lodged—when Mr Chester reclined upon a sofa in his dressing-room in the Temple, entertaining himself with a book.”

Clearly, Mr. Chester, as a representative of a class of people our narrator does not feel too partial to, is associated with night and darkness, but also with narrowness. What do you make of all this?

Let’s see what is going to happen, though! Mr. Chester is preparing to go out, but is doing so in his own leisurely way, reading a book from which he derives uncommon enjoyment. Before long, though, a visitor is announced, and although at first, the host shows no great inclination to receive anyone, this changes when the newcomer sends in Mr. Chester’s riding crop, which he has forgotten at the Maypole. It is clear that the riding crop is a code with the help of which the visitor – none other but Hugh – can ensure access to Mr. Chester. As Mr. Chester is the inventor of this code, he has probably seen fit to make Hugh his ally, or rather tool, and in a few minutes we will learn for what reason. At first, Hugh seems to dominate the scene with his wildness, his bravado and his loud speech, drinking freely from the host’s alcohol, but by and by, it becomes more and more obvious that Mr. Chester has the rough ostler under his thumb. Hugh hands Chester the letter from Emma, which he has taken from Dolly, and Mr. Chester, after reading the letter, burns it. Chester also knows that Hugh has taken the bracelet, and not only the letter, and with the help of this knowledge, he cows Hugh completely – all the more so, since Hugh has the bracelet in his pocket – by implying that he could easily turn Hugh in for a thief to the authorities. When he has established his ascendancy over Hugh, he states that as long as Hugh proves useful to Chester, he will always remain his friend and patron. This may be seen and understood as a promise but implicitly, it is, of course, also a deadly threat. Hugh may treat himself to one more glass or two but he finally has to see that he is but a tool in the hands of Mr. Chester.

QUESTIONS AND THOUGHTS

At the beginning of the chapter, Mr. Chester is reading a book by Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Lord of Chesterfield, called Letters to His Son on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman (1774). This collection of letters gives political and diplomatic advice on how to get on in a world of courtiers, and it is therefore quite Machiavellian in tone. Samuel Johnson wrote about these letters that they “teach the morals of a whore, and the manners of a dancing-master”. Mr. Chester, however, is more delighted with these letters and with Lord Chesterfield as such, than stuffy old Johnson. He openly praises the book to himself in words like:

”’[…] Still, in every page of this enlightened writer, I find some captivating hypocrisy which has never occurred to me before, or some superlative piece of selfishness to which I was utterly a stranger. I should quite blush for myself before this stupendous creature, if remembering his precepts, one might blush at anything. An amazing man! a nobleman indeed! any King or Queen may make a Lord, but only the Devil himself—and the Graces—can make a Chesterfield.’”

What does this show about his person, and does this maybe refer to something beyond his person, something he is a representative of? What is your impression of Mr. Chester so frankly extolling his own crookedness?

Although he lives in a completely different world from Hugh, Mr. Chester instinctively knows how to impress and get the better of that rough customer. Being used to hard words from Willet and the like, ”this cool, complacent, contemptuous, self-possessed reception, caused him [i.e. Hugh] to feel his inferiority more completely than the most elaborate arguments.” What other ways and tricks does Mr. Chester have at his disposal in order to gain mastery over Hugh? And what could be his ulterior motive in doing so? Does this simply happen with a view of hindering any correspondence between his son and Emma?

Some more thoughts about Hugh: When he is offered some spirits, Hugh says,

”’[…] What’s so good to me as this? What ever has been? What else has kept away the cold on bitter nights, and driven hunger off in starving times? What else has given me the strength and courage of a man, when men would have left me to die, a puny child? I should never have had a man’s heart but for this. I should have died in a ditch. Where’s he who when I was a weak and sickly wretch, with trembling legs and fading sight, bade me cheer up, as this did? I never knew him; not I. I drink to the drink, master. Ha ha ha!’”

About the dog he has with him:

”’Such a dog as that, and one of the same breed, was the only living thing except me that howled that day [i.e. the day his mother was hanged],’ said Hugh. ‘Out of the two thousand odd—there was a larger crowd for its being a woman—the dog and I alone had any pity. If he’d have been a man, he’d have been glad to be quit of her, for she had been forced to keep him lean and half-starved; but being a dog, and not having a man’s sense, he was sorry.’”

About his mother:

”’[…] I never knew, nor saw, nor thought about a father; and I was a boy of six—that’s not very old—when they hung my mother up at Tyburn for a couple of thousand men to stare at. They might have let her live. She was poor enough.’”

Those three quotations tell us a lot about Hugh, and maybe also about the narrator’s intentions connected with this character. What are your ideas?

Chapter 24 starts with a summary of how Mr. Chester spent the evening ”in the midst of a dazzling and brilliant circle” after he had finished his conspiratorial business with Hugh of the Maypole. In that circle, Mr. Chester was generally admired for his conversation, his manners, yea even ”the sweetness of his voice”, and how it was said ”that he was one on whom the world’s cares and errors sat lightly as his dress”. It is particularly this last detail that caught my attention for we know which how much care Mr. Chester dresses himself, and if you read this statement carefully and take it literally, hmmm what kind of thing does this then say of Mr. Chester?

The narrator goes even further by pointing out

Then, our narrator describes the effect of that collective adulation on Mr. Chester by saying that it makes him even more cynical:

Why might our narrator slow down the pace of his story a little in order to share these moral observations with us? I was struck with what he says about people deferring to Chester against their better judgment and instinct just because they find everyone else around them doing so and want to keep in tune with the voice of society. This seems to be die-hard feature of human beings, accompanying them through all ages and societies. What particular role could it play on the pages of our novel here?

Now, however, there is no more time for musings because Mr. Tappertit makes his appearance in Mr. Chester’s bedroom, and the way he has himself be announced by the servant makes sure that it is a very dramatic entrée en scène, called ”cloak and dagger” by Mr. Chester. Nevertheless, it is slightly impaired in its effect, maybe, by a gigantic lock that Mr. Tappertit carries with him and puts down in the middle of the room, where the smell of oil exuding from it soon moves Mr. Chester to request him depose it outside. Mr. Tappertit’s initial words speak volumes about him:

A very good statement, indeed! And quite a wise one for the times in which Mr. Tappertit utters it, because it implies that it is not always fair to judge a book by its cover: Why should Mr. Tappertit, being “merely” a locksmith’s apprentice not have in himself the same vastness of soul and grandness of mind than any other man dressed in purple and ermine?

As to the lock, it is probably not just a absurd detail intended to enhance the ludicrous effect of Simon’s appearance. Maybe, it could also be seen as a symbol or means of foreshadowing something. Any ideas?

Mr. Tappertit then comes to the purpose of the interview he is seeking with Mr. Chester by telling him that he knows that his son Edward entertains a relationship with a lady against his father’s wishes. Sim also mentions that Edward, in the past, has behaved towards him with rather a lack of respect and acknowledgement, which he, Sim, cannot but resent. The apprentice also names Barnaby and his mother as among those who aid and abet the two lovers. He then informs Mr. Chester that it would serve his purpose to hinder the locksmith’s daughter to serve as a go-between for the two lovers. He also adds that above all, there is a monster in human shape, a fiend, an inveterate enemy of Mr. Chester at the Maypole, a certain Joe Willet, whom Mr. Chester must by all means get rid of, for example by having him kidnapped.

Being a man of the world, Mr. Chester immediately notices that there is a ”’[…] little private vengeance in this […]’”, and he tells Mr. Tappertit that he knows. Simon then disappears in the manner of some mysterious warner he has read about in a cheap story-book. Mr. Chester congratulates himself on the power he has over his features and voice – by the way, a recurring motif – and says that after all, he will not be spared the necessity of creating some havoc among the worthy Vardens, however sorry he might feel for them. Then he falls into peaceful slumber again.

QUESTIONS AND THOUGHTS

Like Hugh, Simon has joined forces with Mr. Chester, and his two reasons for doing so are quite obvious. In what ways is Mr. Chester’s treatment of Hugh different than that of Simon? What does this tell us about Mr. Chester? Has Mr. Tappertit’s role in the novel changed for you now?

The narrator goes even further by pointing out

”how honest men, who by instinct knew him better, bowed down before him nevertheless, […] and despised themselves why they did so, and yet had not the courage to resist; how, in short, he was one of those who are received and cherished in society (as the phrase is) by scores who individually would shrink from and be repelled by the object of their lavish regard”.

Then, our narrator describes the effect of that collective adulation on Mr. Chester by saying that it makes him even more cynical:

”The despisers of mankind—apart from the mere fools and mimics, of that creed—are of two sorts. They who believe their merit neglected and unappreciated, make up one class; they who receive adulation and flattery, knowing their own worthlessness, compose the other. Be sure that the coldest-hearted misanthropes are ever of this last order.”

Why might our narrator slow down the pace of his story a little in order to share these moral observations with us? I was struck with what he says about people deferring to Chester against their better judgment and instinct just because they find everyone else around them doing so and want to keep in tune with the voice of society. This seems to be die-hard feature of human beings, accompanying them through all ages and societies. What particular role could it play on the pages of our novel here?

Now, however, there is no more time for musings because Mr. Tappertit makes his appearance in Mr. Chester’s bedroom, and the way he has himself be announced by the servant makes sure that it is a very dramatic entrée en scène, called ”cloak and dagger” by Mr. Chester. Nevertheless, it is slightly impaired in its effect, maybe, by a gigantic lock that Mr. Tappertit carries with him and puts down in the middle of the room, where the smell of oil exuding from it soon moves Mr. Chester to request him depose it outside. Mr. Tappertit’s initial words speak volumes about him:

”’[…] Pardon the menial office in which I am engaged, sir, and extend your sympathies to one, who, humble as his appearance is, has inn’ard workings far above his station.’”

A very good statement, indeed! And quite a wise one for the times in which Mr. Tappertit utters it, because it implies that it is not always fair to judge a book by its cover: Why should Mr. Tappertit, being “merely” a locksmith’s apprentice not have in himself the same vastness of soul and grandness of mind than any other man dressed in purple and ermine?

As to the lock, it is probably not just a absurd detail intended to enhance the ludicrous effect of Simon’s appearance. Maybe, it could also be seen as a symbol or means of foreshadowing something. Any ideas?

Mr. Tappertit then comes to the purpose of the interview he is seeking with Mr. Chester by telling him that he knows that his son Edward entertains a relationship with a lady against his father’s wishes. Sim also mentions that Edward, in the past, has behaved towards him with rather a lack of respect and acknowledgement, which he, Sim, cannot but resent. The apprentice also names Barnaby and his mother as among those who aid and abet the two lovers. He then informs Mr. Chester that it would serve his purpose to hinder the locksmith’s daughter to serve as a go-between for the two lovers. He also adds that above all, there is a monster in human shape, a fiend, an inveterate enemy of Mr. Chester at the Maypole, a certain Joe Willet, whom Mr. Chester must by all means get rid of, for example by having him kidnapped.

Being a man of the world, Mr. Chester immediately notices that there is a ”’[…] little private vengeance in this […]’”, and he tells Mr. Tappertit that he knows. Simon then disappears in the manner of some mysterious warner he has read about in a cheap story-book. Mr. Chester congratulates himself on the power he has over his features and voice – by the way, a recurring motif – and says that after all, he will not be spared the necessity of creating some havoc among the worthy Vardens, however sorry he might feel for them. Then he falls into peaceful slumber again.

QUESTIONS AND THOUGHTS

Like Hugh, Simon has joined forces with Mr. Chester, and his two reasons for doing so are quite obvious. In what ways is Mr. Chester’s treatment of Hugh different than that of Simon? What does this tell us about Mr. Chester? Has Mr. Tappertit’s role in the novel changed for you now?

Chapter 25 takes us out of Mr. Chester’s presence – although the narrator still cannot forbear commenting on Mr. Chester’s ”dissembling face”, which is even under Chester’s control when he is asleep – and puts us with Barnaby and his mother. They are making their way to Chigwell, on foot, and while the mother is in an earnest and sombre mood, her son still pursues his way in the erratic and vagrant manner we are used of him. Once again, the narrator starts commenting on life and creation as such, saying things like

Admittedly, the tone of condescension shimmering through some of the words, may go against the grain with modern readers.

We also get to know how Barnaby grew up with his mother and get an impression of the mother’s anguish when she realized that her son’s mental capacities are impaired, but there is no doubt that Mrs. Rudge is a loving and caring mother who would do anything for her child:

When they walk through the village of Chigwell, where she and especially her son are so well-known, she feels that there is a change in everything, that things wear a different air – but she does not realize that the change is not in her surroundings but in herself.

What kind of change might be alluded to here?

Arriving at the Warren, where she had lived and worked for so many years, the widow is immediately and heartily welcomed by Mr. Haredale himself, who is glad that Mrs. Rudge has visited the old place for the first time after so many years. The widow immediately tells him that it will also be the last time she has made this visit. Her former employer does not like to hear her speak this way, pointing out that she would be very welcome to take her abode at the Warren, particularly since it has become quite a home for Barnaby already. Interestingly, Grip, at that juncture, perseveres in rehearsing a sentence he picked up not long ago, namely the one that tells Polly to put the kettle on since they’ll all have tea. Is the raven an evil spirit mocking the two human speakers, or does Grip want to support Mr. Haredale’s suggestion?

Be that as it may, Mrs. Rudge remains firm, for all entreaties and references to the olden days, in her determination no longer to accept any financial and other help from Mr. Haredale – which also means that they have to leave the house in London, since it belongs to Mr. Haredale. The reason she gives is both telltale and obscure at the same time:

When Mr. Haredale, at these words, understandably wonders among what associates she has fallen and under what guilt she labours, she gives the following dark response:

There not being a lot to add on both sides, the interview is soon at an end, and mother and son leave the Warren in order to wait for their coach. Wanting to keep herself and her son as inconspicuous as possible, Mrs. Rudge suggests they should spend the two hours until the coach arrives on the churchyard, where there are also the graves of Mr. Haredale’s slain brother and her own husband. While they are waiting, Grip whiles away the time in the following way:

What do you make of Grip’s behaviour here? Is this just a mindless animal speaking, or can we suspect a dark message behind his words? And what made Mrs. Rudge choose the churchyard as a sequestered place when there might have been other spots to retire to?

When they finally leave, John Willet does not take any notice of him because he thinks coaches a new-fangled idea which he prefers to have as little to do with as possible. Hugh, however, sees the coach of, whispering something to Barnaby.

What might those two be whispering about? This is certainly a mystery, but the darkest mystery is undoubtedly Mrs. Rudge’s behaviour? Why is she so anxious to evade the spectre man and at the same time shies from asking Mr. Haredale’s support in keeping that man at bay? Could she not simply have asked her former employer’s help in turning that spectre man in to justice?

”It is something to look upon enjoyment, so that it be free and wild and in the face of nature, though it is but the enjoyment of an idiot. It is something to know that Heaven has left the capacity of gladness in such a creature’s breast; it is something to be assured that, however lightly men may crush that faculty in their fellows, the Great Creator of mankind imparts it even to his despised and slighted work. Who would not rather see a poor idiot happy in the sunlight, than a wise man pining in a darkened jail!”

Admittedly, the tone of condescension shimmering through some of the words, may go against the grain with modern readers.

We also get to know how Barnaby grew up with his mother and get an impression of the mother’s anguish when she realized that her son’s mental capacities are impaired, but there is no doubt that Mrs. Rudge is a loving and caring mother who would do anything for her child:

”Two-and-twenty years. Her boy’s whole life and history. The last time she looked back upon those roofs among the trees, she carried him in her arms, an infant. How often since that time had she sat beside him night and day, watching for the dawn of mind that never came; how had she feared, and doubted, and yet hoped, long after conviction forced itself upon her! The little stratagems she had devised to try him, the little tokens he had given in his childish way—not of dulness but of something infinitely worse, so ghastly and unchildlike in its cunning—came back as vividly as if but yesterday had intervened. The room in which they used to be; the spot in which his cradle stood; he, old and elfin-like in face, but ever dear to her, gazing at her with a wild and vacant eye, and crooning some uncouth song as she sat by and rocked him; every circumstance of his infancy came thronging back, and the most trivial, perhaps, the most distinctly.”

When they walk through the village of Chigwell, where she and especially her son are so well-known, she feels that there is a change in everything, that things wear a different air – but she does not realize that the change is not in her surroundings but in herself.

What kind of change might be alluded to here?

Arriving at the Warren, where she had lived and worked for so many years, the widow is immediately and heartily welcomed by Mr. Haredale himself, who is glad that Mrs. Rudge has visited the old place for the first time after so many years. The widow immediately tells him that it will also be the last time she has made this visit. Her former employer does not like to hear her speak this way, pointing out that she would be very welcome to take her abode at the Warren, particularly since it has become quite a home for Barnaby already. Interestingly, Grip, at that juncture, perseveres in rehearsing a sentence he picked up not long ago, namely the one that tells Polly to put the kettle on since they’ll all have tea. Is the raven an evil spirit mocking the two human speakers, or does Grip want to support Mr. Haredale’s suggestion?

Be that as it may, Mrs. Rudge remains firm, for all entreaties and references to the olden days, in her determination no longer to accept any financial and other help from Mr. Haredale – which also means that they have to leave the house in London, since it belongs to Mr. Haredale. The reason she gives is both telltale and obscure at the same time:

”‘As I am deeply thankful,’ she made answer, ‘for the kindness of those, alive and dead, who have owned this house; and as I would not have its roof fall down and crush me, or its very walls drip blood, my name being spoken in their hearing; I never will again subsist upon their bounty, or let it help me to subsistence. You do not know,’ she added, suddenly, ‘to what uses it may be applied; into what hands it may pass. I do, and I renounce it.’”

When Mr. Haredale, at these words, understandably wonders among what associates she has fallen and under what guilt she labours, she gives the following dark response:

”‘I am guilty, and yet innocent; wrong, yet right; good in intention, though constrained to shield and aid the bad. Ask me no more questions, sir; but believe that I am rather to be pitied than condemned. I must leave my house to-morrow, for while I stay there, it is haunted. My future dwelling, if I am to live in peace, must be a secret. If my poor boy should ever stray this way, do not tempt him to disclose it or have him watched when he returns; for if we are hunted, we must fly again. And now this load is off my mind, I beseech you—and you, dear Miss Haredale, too—to trust me if you can, and think of me kindly as you have been used to do. If I die and cannot tell my secret even then (for that may come to pass), it will sit the lighter on my breast in that hour for this day’s work; and on that day, and every day until it comes, I will pray for and thank you both, and trouble you no more.’”

There not being a lot to add on both sides, the interview is soon at an end, and mother and son leave the Warren in order to wait for their coach. Wanting to keep herself and her son as inconspicuous as possible, Mrs. Rudge suggests they should spend the two hours until the coach arrives on the churchyard, where there are also the graves of Mr. Haredale’s slain brother and her own husband. While they are waiting, Grip whiles away the time in the following way:

”[…] the raven was in a highly reflective state; walking up and down when he had dined, with an air of elderly complacency which was strongly suggestive of his having his hands under his coat-tails; and appearing to read the tombstones with a very critical taste. Sometimes, after a long inspection of an epitaph, he would strop his beak upon the grave to which it referred, and cry in his hoarse tones, ‘I’m a devil, I’m a devil, I’m a devil!’ but whether he addressed his observations to any supposed person below, or merely threw them off as a general remark, is matter of uncertainty.”

What do you make of Grip’s behaviour here? Is this just a mindless animal speaking, or can we suspect a dark message behind his words? And what made Mrs. Rudge choose the churchyard as a sequestered place when there might have been other spots to retire to?

When they finally leave, John Willet does not take any notice of him because he thinks coaches a new-fangled idea which he prefers to have as little to do with as possible. Hugh, however, sees the coach of, whispering something to Barnaby.

What might those two be whispering about? This is certainly a mystery, but the darkest mystery is undoubtedly Mrs. Rudge’s behaviour? Why is she so anxious to evade the spectre man and at the same time shies from asking Mr. Haredale’s support in keeping that man at bay? Could she not simply have asked her former employer’s help in turning that spectre man in to justice?

Tristram wrote: "Which of the two do you find more realistic, life-like and three-dimensional as a character – Dolly or Emma?..."

Tristram wrote: "Which of the two do you find more realistic, life-like and three-dimensional as a character – Dolly or Emma?..."In fairness, I don't feel as if we've really spent much time with Emma. Two scenes to this point - the confrontation between Ned and her father, in which she pretty much just cried, and with Dolly, in which - to my mind - there was more focus on Dolly and her rather immature observations and advice on love and romance. Emma is, for better or worse, solely focused on her relationship troubles, making her seem sympathetic but somewhat vapid. (A Dickens heroine, vapid?! Shocking!) Dolly has been a rather shallow and silly girl. If it were the 1950s, she'd be swooning over pictures of Ricky Nelson, and vying for the attention of the BMOC. In fact, I picture her a little bit as a tamer version of Ann-Margret's character in Bye Bye Birdie. Despite her immaturity, she's got a little more steel in her spine than Emma, and is much more interesting to read about.

As to her view towards Joe, I think it's two-fold. First, it's hard not to have affection towards someone who heroically comes to one's rescue, especially if they were already fondly thought of. Second, Hugh has unwittingly put Dolly in the position of being Joe's guardian, so to speak, and that, too, may heighten feelings that were, before, not as strong.

Hugh. Oh, Hugh! I had high hopes that you would be a diamond in the rough, but your behavior in this chapter certainly indicates that you're naught but a ruffian and a scoundrel. I'm quite distraught by this turn of events.

Tristram wrote: "Some more thoughts about Hugh..."

Tristram wrote: "Some more thoughts about Hugh...""Like Hugh, Simon has joined forces with Mr. Chester...What does this tell us about Mr. Chester? Has Mr. Tappertit’s role in the novel changed for you now?"

Hugh certainly hasn't redeemed himself now that we've seen his association with Chester, but I do have a bit of sympathy for him now. And he's good to his dog, so he can't be all bad.

I'm fascinated (though appalled) at Chester's ability to charm and manipulate everyone around him. I haven't studied sociopaths much, but Chester must surely be one.

Tappertit was amusing in this interaction, but rather than provide an escape from the drama, his scene with Chester added to my growing feeling of trepidation. To use a term attributed to Lenin, Tappertit is a useful idiot, and I fear his enlightenment might come too late. Unlike Hugh, he has no idea that he's struck a deal with the devil.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 25... "I am guilty, and yet innocent; wrong, yet right; good in intention, though constrained to shield and aid the bad...."

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 25... "I am guilty, and yet innocent; wrong, yet right; good in intention, though constrained to shield and aid the bad....""It was the best of times, it was the worst of times..."

Tristram wrote: "Arriving at the Warren, where she had lived and worked for so many years..."

A minor point, perhaps, but did Mary work there? Her husband did, of course. The story Solomon Daisy tells mentions that Haredale brought Emma and four servants back from London: Rudge, the gardener (why did he need a gardener in London?), and two unnamed female servants. Mary was not named specifically. Was she in residence when the murder took place? Did she and Rudge have their own rooms somewhere in Chigswell? I can't remember if it mentions any of this anywhere. My impression was that Haredale gave her a bit of a stipend because her husband was murdered while serving the family, but not necessarily a pension for her own service. It may not matter at all.

Tristram wrote: What do you make of Grip’s behaviour here?

This was something I wondered about. If a raven is like other talking birds in that the words he says are repetitions of things he's heard, from whom, and under what circumstances, did he learn the phrase, "I'm a devil"? I can't think this phrase was chosen randomly.

Mary Lou wrote: "Hugh certainly hasn't redeemed himself now that we've seen his association with Chester, but I do have a bit of sympathy for him now. And he's good to his dog, so he can't be all bad."

Mary Lou wrote: "Hugh certainly hasn't redeemed himself now that we've seen his association with Chester, but I do have a bit of sympathy for him now. And he's good to his dog, so he can't be all bad."Hugh isn't redeemed in my eyes either, but one of the things Tristram's commentary brought out to me is the paralleling of the Hugh and Dolly and Hugh and Chester chapters. In both cases we have someone in power successfully manipulating someone without it, playing on their fears, and taking a cold pleasure in the process. It's ugly and sad how what's done to Hugh is what Hugh does to others. Although it does surprise me that if this is the message, Dickens reverses the chapter order. He could have shown, food-chain, Chester manipulating Hugh and Hugh then manipulating Dolly. Instead, Hugh seems to be an autonomous agent in the Dolly chapter (true, later we learn he's working for Chester, but since Chester hasn't yet taken out the gallows threat, Hugh seems at that point to be choosing to work for him freely), so that we dislike him as a bully before we see him bullied. Doesn't seem to be the optimal way to stir our sympathy.

Then again, it's also clear that even before Chester, Hugh has received the short end of a lot of sticks. Still, I find the order of the storytelling here a little odd.

Does Hugh's dog remind anyone else of Sykes's dog?

Tristram wrote: "Dolly notices that both the letter she was entrusted with by Emma and the bracelet have disappeared..."

Tristram wrote: "Dolly notices that both the letter she was entrusted with by Emma and the bracelet have disappeared..."Well, so much for clear communication between lovers.

Could be worse though, since it sounds like it will be duly communicated to Ned that Emma wrote him a soulful response.

As an aside, Mr. Haredale, judging from his treatment of Mrs. Rudge, seems like a decent guy after all.

Mrs. Rudge's virtuous evasions annoy me every bit as much as Mrs. Varden's contrarianism. Really if Mrs. R was Mrs. V's pre-marriage rival, Gabriel Varden didn't have much to choose from.

Julie wrote: "...one of the things Tristram's commentary brought out to me is the paralleling of the Hugh and Dolly and Hugh and Chester chapters. In both cases we have someone in power successfully manipulating someone without it, playing on their fears, and taking a cold pleasure in the process...."

Julie wrote: "...one of the things Tristram's commentary brought out to me is the paralleling of the Hugh and Dolly and Hugh and Chester chapters. In both cases we have someone in power successfully manipulating someone without it, playing on their fears, and taking a cold pleasure in the process...."Nice! That wasn't apparent to me, perhaps because of the order of the chapters, as you said. Or perhaps because I just missed it, which is more likely. :-)

Mary Lou wrote: "Despite her immaturity, she's got a little more steel in her spine than Emma, and is much more interesting to read about. "

Those are exactly my sentiments! Reading about Dickens heroines is rarely very interesting to me because those ethereal women have hardly any real life in them. They are just too perfect, too much given to self-denial and displaying passive virtues. Now, Dolly is quite another case: She has her faults but there is also much good in her.

Those are exactly my sentiments! Reading about Dickens heroines is rarely very interesting to me because those ethereal women have hardly any real life in them. They are just too perfect, too much given to self-denial and displaying passive virtues. Now, Dolly is quite another case: She has her faults but there is also much good in her.

Mary Lou wrote: "and under what circumstances, did he learn the phrase, "I'm a devil"? I can't think this phrase was chosen randomly."

Let's hope it was just somebody with a particularly sinister sense of humour who taught Grip that phrase, and not somebody who used it for himself, giving Grip the opportunity to pick it up.

Nevertheless, this sentence begs the question as to Grip's role in this novel: Is he Barnaby's evil spirit, tempting him into all sorts of trouble and mischief, or is he as wise as the ravens in Norse mythology, providing some sort of dramatic irony by viewing the events from above?

Let's hope it was just somebody with a particularly sinister sense of humour who taught Grip that phrase, and not somebody who used it for himself, giving Grip the opportunity to pick it up.

Nevertheless, this sentence begs the question as to Grip's role in this novel: Is he Barnaby's evil spirit, tempting him into all sorts of trouble and mischief, or is he as wise as the ravens in Norse mythology, providing some sort of dramatic irony by viewing the events from above?

Well, a very interesting and informative group of chapters. My first observation is how much this changes my opinion of Mr. Haredale. Although he is still controlling toward his niece, he certainly is showing fairness toward her in not taking her letter and now kindness toward Mrs. Rudge.

Well, a very interesting and informative group of chapters. My first observation is how much this changes my opinion of Mr. Haredale. Although he is still controlling toward his niece, he certainly is showing fairness toward her in not taking her letter and now kindness toward Mrs. Rudge. As for Mrs. Rudge, I am concerned about how she will maintain a livelihood for herself and Barnaby on her own. These actions seem to be very dangerous and unwise. It is very worrisome as to what will happen to her and reminds me of the worry I felt regarding the women in NN. I do not like to see women in that day and age on their own with little or no protection.

The plot thickens and I am drawn into it.

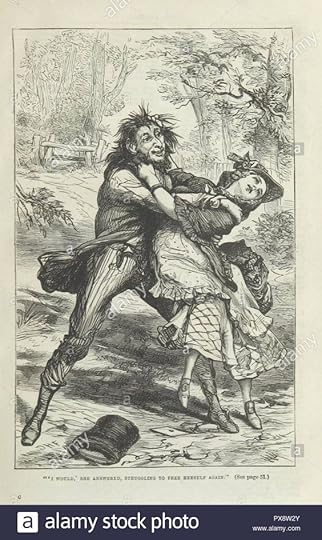

Hugh is a satyr. We see him emerging from the depths of the woods to harass, threaten, and make unwanted advances towards Dolly. What a suggestive scene. Dickens describes Hugh in very unfavourable terms, from him being unable to read to him being described as animal-like in nature. He sleeps in the Maypole’s outbuildings. When Joe comes to the rescue we see a love triangle being clearly established. Dolly, for her part, apparently has no interest in either suitor. For the reader, however, we have tension created in how these three characters will be shuffled by Dickens in the story.

Also, I found in the confrontation of Hugh and Dolly there is some sexual suggestion. Hugh, like a satyr, emerges from an enclosed private place, he hunts her down when she attempts to run and encircles his arms around her. Hugh “passes his arm about his waist, [and] held her in his strong grasp” and he enjoys it when Dolly strikes him. Hugh calls Dolly “Sweetlips” and there is a clear indication that Hugh forces a kiss upon her. “A fine for calling out” Hugh says, “... a fine, pretty one from your lips. I pay myself! Ha ha ha!”

This unsettling chapter included Hugh’s theft of a letter and a bracelet. Symbolically, Hugh has stolen both the words of a true lover and a gift of value freely offered as a gesture of love.

Dickens is clearly setting up the contrary natures of lust and love. On the one hand we have the likes of Simon Tappertit and Hugh, on the other Joe and Ned.

Also, I found in the confrontation of Hugh and Dolly there is some sexual suggestion. Hugh, like a satyr, emerges from an enclosed private place, he hunts her down when she attempts to run and encircles his arms around her. Hugh “passes his arm about his waist, [and] held her in his strong grasp” and he enjoys it when Dolly strikes him. Hugh calls Dolly “Sweetlips” and there is a clear indication that Hugh forces a kiss upon her. “A fine for calling out” Hugh says, “... a fine, pretty one from your lips. I pay myself! Ha ha ha!”

This unsettling chapter included Hugh’s theft of a letter and a bracelet. Symbolically, Hugh has stolen both the words of a true lover and a gift of value freely offered as a gesture of love.

Dickens is clearly setting up the contrary natures of lust and love. On the one hand we have the likes of Simon Tappertit and Hugh, on the other Joe and Ned.

When Mr Chester has his riding crop returned while he was reading Chesterfield’s book on how to get along in a world of courtiers we find two contrasting, but very revealing symbols introduced into the narrative. Hugh’s returning of the riding crop suggests that he is under the power of Chester, just as a horse is controlled by a crop. The theme of Chesterfield’s book reflects Chester’s attitude and treatment of his son. Combined, however, the riding crop and the book serve as symbols to what Tristram has noted. Mr Chester is a Machiavellian character. He is willing to use the subversive suggestions of Chesterfield’s book or the more direct and potentially physically painful method of a riding crop.

Pain or pleasure, Mr Chester intends to have power over those who surround him.

Pain or pleasure, Mr Chester intends to have power over those who surround him.

Yes, Peter, Chester is a true Machiavelli. He also uses the carrot and the stick in conjunction. The stick could be the riding crop, and the carrot could be the alcohol Hugh is allowed to serve himself to in Chester's room. As also the promise of something more - what may be the reward for Hugh's service? Money? Or Dolly? - as long as he proves useful to Chester.

In fact, the bracelet combines both sides: The carrot in that it is an object of value Hugh could sell, or it can serve as a stand-in for Dolly. The stick in that Hugh's being in possession of this bracelet gives Chester power over him because he can now have him arrested as a highwayman whenever he pleases.

A very cold-hearted strategist, is Mr. Chester.

In fact, the bracelet combines both sides: The carrot in that it is an object of value Hugh could sell, or it can serve as a stand-in for Dolly. The stick in that Hugh's being in possession of this bracelet gives Chester power over him because he can now have him arrested as a highwayman whenever he pleases.

A very cold-hearted strategist, is Mr. Chester.

Bobbie wrote: "Well, a very interesting and informative group of chapters. My first observation is how much this changes my opinion of Mr. Haredale. Although he is still controlling toward his niece, he certainly..."

Yes, Haredale is indeed the nicer person compared to Chester, although one might have thought differently in their first encounter, maybe. Just as many people who have to deal with Chester might feel called upon by circumstances to reconsider their initial impression.

Yes, Haredale is indeed the nicer person compared to Chester, although one might have thought differently in their first encounter, maybe. Just as many people who have to deal with Chester might feel called upon by circumstances to reconsider their initial impression.

Regarding Hugh's attacking Dolly and him admonishing her for looking down on him, is it possible that Hugh has watched Dolly grow up and now turn into a woman? So Hugh is expecting her to think the better of him?

Regarding Hugh's attacking Dolly and him admonishing her for looking down on him, is it possible that Hugh has watched Dolly grow up and now turn into a woman? So Hugh is expecting her to think the better of him?

Tristram wrote: "Yes, Peter, Chester is a true Machiavelli. He also uses the carrot and the stick in conjunction. The stick could be the riding crop, and the carrot could be the alcohol Hugh is allowed to serve him..."

Tristram

Ah, yes. I forgot about the use that Chester uses alcohol in his dealings with others. The bracelet may well find its way back into the story later on as well.

As I look back on the villains in Dickens’s earlier novels such as Bumble, Ralph Nickleby, and Quilp it is evident that with Mr Chester we have reached new depths of depravity. I confess that before this reading of Barnaby Rudge I thought it was a lightweight novel. I am rapidly changing my opinion.

Tristram

Ah, yes. I forgot about the use that Chester uses alcohol in his dealings with others. The bracelet may well find its way back into the story later on as well.

As I look back on the villains in Dickens’s earlier novels such as Bumble, Ralph Nickleby, and Quilp it is evident that with Mr Chester we have reached new depths of depravity. I confess that before this reading of Barnaby Rudge I thought it was a lightweight novel. I am rapidly changing my opinion.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 25 takes us out of Mr. Chester’s presence – although the narrator still cannot forbear commenting on Mr. Chester’s ”dissembling face”, which is even under Chester’s control when he is aslee..."

This is a very important and yet confusing chapter for, once again, it is a chapter that both gives the reader further insight and understanding into the characters involved but, at the same time, raises more questions than it answers.

Mrs Rudge has been a conundrum so farrow the reader. On the one hand, she has been mysterious, contrary, and secretive. Both Mr Haredale and Varden have been her friends for years and yet she refuses to let them help her. Indeed, she shuns their attempts to help. Nevertheless, Dickens makes it quite clear that she loves her son Barnaby very much. Regardless of her struggles, disappointments, and sorrow in life she has done her best for Barnaby. And yet from Barnaby too she hides the interplay between her and the spectre. Mrs Rudge is a fascinating creation of Dickens.

This chapter also serves to further demonstrate the character of Mr Haredale. His social position is such that he could enjoy and demand a social difference from Varden, Mrs Rudge and the cabal of men at the Maypole. Haredale chooses, however, to be kind to those around him. This creates a strong contrast between him and Mr Chester. While both have social rank, only Haredale is seen as being open, honest, and supportive of others rather than the egocentric Mr Chester.

Ah, the long wait in the graveyard for the coach. It would certainly be a place of more quiet and contemplation than being at the Maypole. Still, Dickens does little without meaning, and physical places serve as clear symbols in his novels. It is interesting that Grip seems more interested in the graves than Mrs Rudge, even though both her husband and Mr Haredale’s slain brother are buried there. Grip keeps repeating “I’m a devil.” Who is he referring to? Himself? A person buried in the churchyard? Mrs Rudge? Barnaby? The words may seem to be nonsensical but I think we need to consider them as more important than that.

This is a very important and yet confusing chapter for, once again, it is a chapter that both gives the reader further insight and understanding into the characters involved but, at the same time, raises more questions than it answers.

Mrs Rudge has been a conundrum so farrow the reader. On the one hand, she has been mysterious, contrary, and secretive. Both Mr Haredale and Varden have been her friends for years and yet she refuses to let them help her. Indeed, she shuns their attempts to help. Nevertheless, Dickens makes it quite clear that she loves her son Barnaby very much. Regardless of her struggles, disappointments, and sorrow in life she has done her best for Barnaby. And yet from Barnaby too she hides the interplay between her and the spectre. Mrs Rudge is a fascinating creation of Dickens.

This chapter also serves to further demonstrate the character of Mr Haredale. His social position is such that he could enjoy and demand a social difference from Varden, Mrs Rudge and the cabal of men at the Maypole. Haredale chooses, however, to be kind to those around him. This creates a strong contrast between him and Mr Chester. While both have social rank, only Haredale is seen as being open, honest, and supportive of others rather than the egocentric Mr Chester.

Ah, the long wait in the graveyard for the coach. It would certainly be a place of more quiet and contemplation than being at the Maypole. Still, Dickens does little without meaning, and physical places serve as clear symbols in his novels. It is interesting that Grip seems more interested in the graves than Mrs Rudge, even though both her husband and Mr Haredale’s slain brother are buried there. Grip keeps repeating “I’m a devil.” Who is he referring to? Himself? A person buried in the churchyard? Mrs Rudge? Barnaby? The words may seem to be nonsensical but I think we need to consider them as more important than that.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Yes, Peter, Chester is a true Machiavelli. He also uses the carrot and the stick in conjunction. The stick could be the riding crop, and the carrot could be the alcohol Hugh is all..."

Peter,

You are right. This is anything but a lightweight novel but very easily underestimated. My present rereading of the novel convinces me more and more that I should upgrade my present rating to five stars.

Peter,

You are right. This is anything but a lightweight novel but very easily underestimated. My present rereading of the novel convinces me more and more that I should upgrade my present rating to five stars.

Tristram wrote: "Let's hope it was just somebody with a particularly sinister sense of humour who taught Grip that phrase, and not somebody who used it for himself, giving Grip the opportunity to pick it up."

Somehow I don't believe it was not just someone with a sinister sense of humour. There must be a reason Grip keeps saying 'I'm a devil'. We will see what it means at some point, I guess.

Julie wrote: "Then again, it's also clear that even before Chester, Hugh has received the short end of a lot of sticks. Still, I find the order of the storytelling here a little odd.

Does Hugh's dog remind anyone else of Sykes's dog? "

Yes, and in these chapters Hugh reminds me of Sykes anyway. Might be because they're both a ruffian with a dog though.

Somehow I don't believe it was not just someone with a sinister sense of humour. There must be a reason Grip keeps saying 'I'm a devil'. We will see what it means at some point, I guess.

Julie wrote: "Then again, it's also clear that even before Chester, Hugh has received the short end of a lot of sticks. Still, I find the order of the storytelling here a little odd.

Does Hugh's dog remind anyone else of Sykes's dog? "

Yes, and in these chapters Hugh reminds me of Sykes anyway. Might be because they're both a ruffian with a dog though.

Hugh accosts Dolly Varden

Chapter 21

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It was for the moment an inexpressible relief to Dolly, to recognise in the person who forced himself into the path so abruptly, and now stood directly in her way, Hugh of the Maypole, whose name she uttered in a tone of delighted surprise that came from her heart.

‘Was it you?’ she said, ‘how glad I am to see you! and how could you terrify me so!’

In answer to which, he said nothing at all, but stood quite still, looking at her.

‘Did you come to meet me?’ asked Dolly.

Hugh nodded, and muttered something to the effect that he had been waiting for her, and had expected her sooner.

‘I thought it likely they would send,’ said Dolly, greatly reassured by this.

‘Nobody sent me,’ was his sullen answer. ‘I came of my own accord.’

The rough bearing of this fellow, and his wild, uncouth appearance, had often filled the girl with a vague apprehension even when other people were by, and had occasioned her to shrink from him involuntarily. The having him for an unbidden companion in so solitary a place, with the darkness fast gathering about them, renewed and even increased the alarm she had felt at first.

If his manner had been merely dogged and passively fierce, as usual, she would have had no greater dislike to his company than she always felt—perhaps, indeed, would have been rather glad to have had him at hand. But there was something of coarse bold admiration in his look, which terrified her very much. She glanced timidly towards him, uncertain whether to go forward or retreat, and he stood gazing at her like a handsome satyr; and so they remained for some short time without stirring or breaking silence. At length Dolly took courage, shot past him, and hurried on.

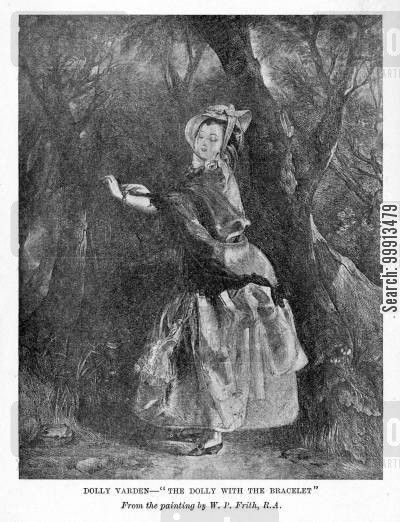

Hugh and Dolly Varden

Chapter 21

Felix O. C. Darley

1888

Text Illustrated:

The rough bearing of this fellow, and his wild, uncouth appearance, had often filled the girl with a vague apprehension even when other people were by, and had occasioned her to shrink from him involuntarily. The having him for an unbidden companion in so solitary a place, with the darkness fast gathering about them, renewed and even increased the alarm she had felt at first.

If his manner had been merely dogged and passively fierce, as usual, she would have had no greater dislike to his company than she always felt — perhaps, indeed, would have been rather glad to have had him at hand. But there was something of coarse bold admiration in his look, which terrified her very much. She glanced timidly towards him, uncertain whether to go forward or retreat, and he stood gazing at her like a handsome satyr; and so they remained for some short time without stirring or breaking silence. At length Dolly took courage, shot past him, and hurried on.

"Why do you spend so much breath in avoiding me?" said Hugh, accommodating his pace to hers, and keeping close at her side.

"I wish to get back as quickly as I can, and you walk too near me, answered Dolly."

"Too near!" said Hugh, stooping over her so that she could feel his breath upon her forehead. "Why too near? You're always proud to me, mistress."

"I am proud to no one. You mistake me," answered Dolly. "Fall back, if you please, or go on."

"Nay, mistress," he rejoined, endeavouring to draw her arm through his, "I'll walk with you." — Chapter XXI.

Commentary:

Dickens's official illustrators for Barnaby Rudge, George Cattermole and Hablot Knight Browne depict the charming heroine of the novel, Dolly Varden, some nine times in their seventy-six illustrations, which initially appeared in Master Humphrey's Clock 13 February through 27 November 1841. Likewise, they depict the loutish Hugh, outlet at the Maypole, ten times, including by himself in the Phiz portrait of an inebriated Hugh in chapter 11 (12 March 1841. Although Dickens introduces Dolly in the fourth chapter simultaneously with Phiz's illustration It's a Poor Heart That Never Rejoices, Dickens offers no description of her, other than that she is the locksmith's "handsome" daughter. For Hugh, on the other hand, Dickens offers a verbal portrait to complement Hablot Knight Browne's full-page portrait of the muscular but inebriated ostler:

There were present two, however, who showed but little interest in the general contentment. Of these, one was Barnaby himself, who slept, or, to avoid being beset with questions, feigned to sleep, in the chimney-corner; the other, Hugh, who, sleeping too, lay stretched upon the bench on the opposite side, in the full glare of the blazing fire.

The light that fell upon this slumbering form, showed it in all its muscular and handsome proportions. It was that of a young man, of a hale athletic figure, and a giant's strength, whose sunburnt face and swarthy throat, overgrown with jet black hair, might have served a painter for a model. Loosely attired, in the coarsest and roughest garb, with scraps of straw and hay — his usual bed — clinging here and there, and mingling with his uncombed locks, he had fallen asleep in a posture as careless as his dress. The negligence and disorder of the whole man, with something fierce and sullen in his features, gave him a picturesque appearance, that attracted the regards even of the Maypole customers who knew him well, and caused Long Parkes to say that Hugh looked more like a poaching rascal to-night than ever he had seen him yet. — Chapter XI.

On the other hand, Dickens offers no detailed description of the coquettish, fashionably dressed heroine until chapter 19, a description that is more concerned with her mode of dress than he face, form, and character:

As to Dolly, there she was again, the very pink and pattern of good looks, in a smart little cherry-coloured mantle, with a hood of the same drawn over her head, and upon the top of that hood, a little straw hat trimmed with cherry-coloured ribbons, and worn the merest trifle on one side-just enough in short to make it the wickedest and most provoking head-dress that ever malicious milliner devised.

Curiously, Dickens transfers her coquettish nature to her garments, including "a cruel little muff, and such a heart-rending pair of shoes", the whole ensemble inspiring the portrait painter William Powell Frith in his 1842 visualization of her, the oil painting now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, a study more fashion plate than literary character. Not interested in mere portraiture, here, however, Darley has made hismodel Hugh Accosts Dolly Varden in chapter 21 (1 May 1841), although Darley has positioned the assailant so that the viewer must imagine Hugh's aggressive expression and is not aware of his mane of jet black hair.

Whereas ludicrous Hugh in the original was a static, hairy caricature, in Darley's dual character study he is caught in motion and clearly means to harm Dolly. Moreover, Darley has reversed the order of the figures, placing Hugh in the left foreground and Dolly, right rear, and thereby disposing of the figures more dramatically than the original. Dolly's gesture of defence and her posture, leaning back, complement the forward movement of Hugh's right leg, and Hugh's legs are balanced by the wicket in the right foreground, as if he, too, represents a barrier in her path. Small-framed Darley makes the figures binary opposites, with small, feminine Dolly's precise and fashionable attire, including a hat, contrasting the giant in everyday working clothes, lacking both jacket and hat. Whereas the woods in the background frame the figures in Phiz's original steel engraving, in Darley's photogravure plate the woods recede into the distance, forcing the eye well forward.

As was the case with his portrait of Barnaby, Darley had a model in mind from among the original illustrations, but has reshaped it to sharpen the effect and heighten our appreciation of the character. Darley utilizes the natural setting both to heighten the sense of Dolly's isolation and vulnerability and to connect the savage ostler with the power of nature, and perhaps even its insentience. As opposed to those of the clownish figure in Phiz's plate, Hugh's malevolent intentions are much clearer in the realistic Darley study, as are Dolly's apprehensions, and the period treatment of Hugh's clothing underscores the realistic nature of the rape scene — he is no mere cartoon character. If one may guibble with a scene so dramatically realised, one might challenge Darley's conception of feminine beauty as not matching Frith's, for Dolly's coquettish charm sufficiently impressed her image on the minds of readers on both sides of the Atlantic and, after her capture during the Gordon Riots, elicited their sympathy, that she leant her name to a gaily speckled species of North American trout, an elegantly decorated early sewing machine, an 1872 style of eighteenth-century-inspired dress that included a parasol and beribboned straw hat, and ultimately a British Columbia silver mine (circa 1910). "Dolly Varden" remains London Cockney rhyming slang for "garden."

The Maypole's Stately Couch

Chapter 22

George Cattermole

Text Illustrated:

Notwithstanding this uncivil exhortation, Miggs gladly did as she was required; and told him how that their young mistress, being alone in the meadows after dark, had been attacked by three or four tall men, who would have certainly borne her away and perhaps murdered her, but for the timely arrival of Joseph Willet, who with his own single hand put them all to flight, and rescued her; to the lasting admiration of his fellow-creatures generally, and to the eternal love and gratitude of Dolly Varden.

‘Very good,’ said Mr Tappertit, fetching a long breath when the tale was told, and rubbing his hair up till it stood stiff and straight on end all over his head. ‘His days are numbered.’

‘Oh, Simmun!’

‘I tell you,’ said the ‘prentice, ‘his days are numbered. Leave me. Get along with you.’

Miggs departed at his bidding, but less because of his bidding than because she desired to chuckle in secret. When she had given vent to her satisfaction, she returned to the parlour; where the locksmith, stimulated by quietness and Toby, had become talkative, and was disposed to take a cheerful review of the occurrences of the day. But Mrs Varden, whose practical religion (as is not uncommon) was usually of the retrospective order, cut him short by declaiming on the sinfulness of such junketings, and holding that it was high time to go to bed. To bed therefore she withdrew, with an aspect as grim and gloomy as that of the Maypole’s own state couch; and to bed the rest of the establishment soon afterwards repaired.

This seems like an odd place for an illustration of a room in the Maypole, but there it is and so here it is.

Hugh calls on his patron

Chapter 23

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘How many can you bear?’ he said, filling the glass again.

‘As many as you like to give me. Pour on. Fill high. A bumper with a bead in the middle! Give me enough of this,’ he added, as he tossed it down his hairy throat, ‘and I’ll do murder if you ask me!’

‘As I don’t mean to ask you, and you might possibly do it without being invited if you went on much further,’ said Mr Chester with great composure, ‘we will stop, if agreeable to you, my good friend, at the next glass. You were drinking before you came here.’

‘I always am when I can get it,’ cried Hugh boisterously, waving the empty glass above his head, and throwing himself into a rude dancing attitude. ‘I always am. Why not? Ha ha ha! What’s so good to me as this? What ever has been? What else has kept away the cold on bitter nights, and driven hunger off in starving times? What else has given me the strength and courage of a man, when men would have left me to die, a puny child? I should never have had a man’s heart but for this. I should have died in a ditch. Where’s he who when I was a weak and sickly wretch, with trembling legs and fading sight, bade me cheer up, as this did? I never knew him; not I. I drink to the drink, master. Ha ha ha!’

‘You are an exceedingly cheerful young man,’ said Mr Chester, putting on his cravat with great deliberation, and slightly moving his head from side to side to settle his chin in its proper place. ‘Quite a boon companion.’

‘Do you see this hand, master,’ said Hugh, ‘and this arm?’ baring the brawny limb to the elbow. ‘It was once mere skin and bone, and would have been dust in some poor churchyard by this time, but for the drink.’

‘You may cover it,’ said Mr Chester, ‘it’s sufficiently real in your sleeve.’

‘I should never have been spirited up to take a kiss from the proud little beauty, master, but for the drink,’ cried Hugh. ‘Ha ha ha! It was a good one. As sweet as honeysuckle, I warrant you. I thank the drink for it. I’ll drink to the drink again, master. Fill me one more. Come. One more!’

Purifying the atmosphere

Chapter 23

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Good night,’ he returned. ‘Remember; you’re safe with me—quite safe. So long as you deserve it, my good fellow, as I hope you always will, you have a friend in me, on whose silence you may rely. Now do be careful of yourself, pray do, and consider what jeopardy you might have stood in. Good night! bless you!’

Hugh truckled before the hidden meaning of these words as much as such a being could, and crept out of the door so submissively and subserviently—with an air, in short, so different from that with which he had entered—that his patron on being left alone, smiled more than ever.

‘And yet,’ he said, as he took a pinch of snuff, ‘I do not like their having hanged his mother. The fellow has a fine eye, and I am sure she was handsome. But very probably she was coarse—red-nosed perhaps, and had clumsy feet. Aye, it was all for the best, no doubt.’

With this comforting reflection, he put on his coat, took a farewell glance at the glass, and summoned his man, who promptly attended, followed by a chair and its two bearers.

‘Foh!’ said Mr Chester. ‘The very atmosphere that centaur has breathed, seems tainted with the cart and ladder. Here, Peak. Bring some scent and sprinkle the floor; and take away the chair he sat upon, and air it; and dash a little of that mixture upon me. I am stifled!’

The man obeyed; and the room and its master being both purified, nothing remained for Mr Chester but to demand his hat, to fold it jauntily under his arm, to take his seat in the chair and be carried off; humming a fashionable tune.

A painful interview

Chapter 25

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The tale connected with the mansion borne in mind, it seemed, as has been already said, the chosen theatre for such a deed as it had known. The room in which this group were now assembled—hard by the very chamber where the act was done—dull, dark, and sombre; heavy with worm-eaten books; deadened and shut in by faded hangings, muffling every sound; shadowed mournfully by trees whose rustling boughs gave ever and anon a spectral knocking at the glass; wore, beyond all others in the house, a ghostly, gloomy air. Nor were the group assembled there, unfitting tenants of the spot. The widow, with her marked and startling face and downcast eyes; Mr Haredale stern and despondent ever; his niece beside him, like, yet most unlike, the picture of her father, which gazed reproachfully down upon them from the blackened wall; Barnaby, with his vacant look and restless eye; were all in keeping with the place, and actors in the legend. Nay, the very raven, who had hopped upon the table and with the air of some old necromancer appeared to be profoundly studying a great folio volume that lay open on a desk, was strictly in unison with the rest, and looked like the embodied spirit of evil biding his time of mischief.

‘I scarcely know,’ said the widow, breaking silence, ‘how to begin. You will think my mind disordered.’

‘The whole tenor of your quiet and reproachless life since you were last here,’ returned Mr Haredale, mildly, ‘shall bear witness for you. Why do you fear to awaken such a suspicion? You do not speak to strangers. You have not to claim our interest or consideration for the first time. Be more yourself. Take heart. Any advice or assistance that I can give you, you know is yours of right, and freely yours.’

‘What if I came, sir,’ she rejoined, ‘I who have but one other friend on earth, to reject your aid from this moment, and to say that henceforth I launch myself upon the world, alone and unassisted, to sink or swim as Heaven may decree!’

‘You would have, if you came to me for such a purpose,’ said Mr Haredale calmly, ‘some reason to assign for conduct so extraordinary, which—if one may entertain the possibility of anything so wild and strange—would have its weight, of course.’

‘That, sir,’ she answered, ‘is the misery of my distress. I can give no reason whatever. My own bare word is all that I can offer. It is my duty, my imperative and bounden duty. If I did not discharge it, I should be a base and guilty wretch. Having said that, my lips are sealed, and I can say no more.’

Old John asleep in his cosy bar

Chapter 25

George Cattermole

Text Illustrated:

It was a quiet pretty spot, but a sad one for Barnaby’s mother; for Mr Reuben Haredale lay there, and near the vault in which his ashes rested, was a stone to the memory of her own husband, with a brief inscription recording how and when he had lost his life. She sat here, thoughtful and apart, until their time was out, and the distant horn told that the coach was coming.

Barnaby, who had been sleeping on the grass, sprung up quickly at the sound; and Grip, who appeared to understand it equally well, walked into his basket straightway, entreating society in general (as though he intended a kind of satire upon them in connection with churchyards) never to say die on any terms. They were soon on the coach-top and rolling along the road.

It went round by the Maypole, and stopped at the door. Joe was from home, and Hugh came sluggishly out to hand up the parcel that it called for. There was no fear of old John coming out. They could see him from the coach-roof fast asleep in his cosy bar. It was a part of John’s character. He made a point of going to sleep at the coach’s time. He despised gadding about; he looked upon coaches as things that ought to be indicted; as disturbers of the peace of mankind; as restless, bustling, busy, horn-blowing contrivances, quite beneath the dignity of men, and only suited to giddy girls that did nothing but chatter and go a-shopping. ‘We know nothing about coaches here, sir,’ John would say, if any unlucky stranger made inquiry touching the offensive vehicles; ‘we don’t book for ‘em; we’d rather not; they’re more trouble than they’re worth, with their noise and rattle. If you like to wait for ‘em you can; but we don’t know anything about ‘em; they may call and they may not—there’s a carrier—he was looked upon as quite good enough for us, when I was a boy.’