The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Barnaby Rudge

>

BR chapters 26-30

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 27

This chapter continues the meeting of Haredale and Chester. Chester inquires if either Haredale or Varden are going his way. Finding he will be leaving alone, Chester “with inconceivable politeness” leaves the tenement. As Chester walks down the street he compliments himself on how he once again handled Haredale with such ease and how he has “wound[ed] [Haredale] deeper and more keenly than if I were the best swordsman in all Europe.” Chester tells himself that swordplay is “a barbarian mode of warfare.” These two men are enemies. Dickens has introduced the idea of swordplay. Could this be foreshadowing?

Thoughts

There is a palatable evil in Chester’s mind and actions. Why do you think Dickens is evolving the animosity between Haredale and Chester so strongly?

The next thing we know Chester is outside the Golden Key of Varden’s shop. What is he doing there? Why didn’t he come with Varden back to this house? We next see that Sim Tappertit and Chester acquainted. Tappertit whispers the name Joseph Willet in Chester’s ear. With that Sim then escorts Chester into Varden’s parlour and announces Chester to Mrs Varden. Miggs is thrilled and Chester reveals how his turn of phrase can render a woman into a swoon-like state. It is interesting to note that Dolly is not as taken in by Chester's smooth talking. Dolly is distressed by the way Chester looks at her. Do you recall when Dolly could not help but take a couple of peeks at herself in a mirror earlier in the novel? Well, here we see Dolly look away from Chester's glances. I believe there is much more to Dolly than we may think. While she may be mildly interested by Chester's manner, Dolly is not completely smitten by his charms as Miggs and Mrs Varden are.

Chester introduces Ned into the conversation and notes that Dolly is attending very closely to what he is saying. I love the way Chester constantly comments on the importance of being sincere. As reader’s we know that Chester is a very insincere person. The dramatic irony of his conversation is delightful, but somewhat unsettling. Mrs Varden is completely taken in. All she can think about is the importance of being sincere and Protestant. For Dolly, she hears that, according to Mr Chester, Ned has a “roving nature.” Slowly but surely Chester continues to poison Ned and his character to the Varden’s and Miggs. He tells them that “there are grave and weighty reasons, pressing family considerations and ... points of religious difference” that combine to make the union of Emma and Ned “impossible.” Next, in a very insincere manner, Chester comments that Dolly and Mr Varden have been encouraging the union of Emma and Ned. The climax of Chester’s comments comes when he says that Ned is bound by duty and “every solemn tie and obligation to marry some one else.”

We learn that Emma is of “a Catholic family.” As if that was not enough, Chester claims that Ned has “ruinously expensive habits” and if Ned were to marry Emma, then Chester tells Mrs Varden that he would disown his own son that, no doubt, Chester suggests would lead to Emma and Ned’s marriage not lasting a year. At the end of this conversation Mrs Varden “entered into a secret treaty of alliance, offensive and defensive, with her insinuating visitor.” On the other hand, Dolly has little interest in Chester’s words. Three cheers for Dolly!

As the chapter ends we return to Dolly who comments that “Mr Chester is something like Miggs ... For all his politeness and pleasant speaking, I am pretty sure he was making game of us, more than once.” Dolly knows how insincere Miggs is towards her mother. We also learn that Dolly does not believe Chester’s suave conversation and his accusations about Ned. By the end of this chapter it is to Dolly the reader must turn to for clarity and insight.

Thoughts

There are many ways readers could respond to this chapter. Were you amused by the Chester - Mrs Varden conversation, horrified by Mrs Varden’s naiveté, shocked by Chester’s despicable character, encouraged by Dolly’s insightful nature or ... ? Tell us your thoughts.

In this chapter we have a clear reference to the Protestant-Catholic conflict that will become more intense as the novel proceeds. To what extent do you think it was effective that Dickens would introduce the issue through the lens of two young lovers?

The conversation between Chester and Mrs Varden was what I imagine the one between Satan and Eve in the Garden of Eden could have been like. What is your opinion of how Chester conducted himself in their meeting? What weaknesses of Mrs Varden’s character did he exploit?

What is your opinion of Dolly at the end of this chapter? Has it changed from the earlier chapters of the novel?

I have struggled to find the best word or phrase to describe Chester’s character. How would you describe him? What are your reasons for your choice?

This chapter continues the meeting of Haredale and Chester. Chester inquires if either Haredale or Varden are going his way. Finding he will be leaving alone, Chester “with inconceivable politeness” leaves the tenement. As Chester walks down the street he compliments himself on how he once again handled Haredale with such ease and how he has “wound[ed] [Haredale] deeper and more keenly than if I were the best swordsman in all Europe.” Chester tells himself that swordplay is “a barbarian mode of warfare.” These two men are enemies. Dickens has introduced the idea of swordplay. Could this be foreshadowing?

Thoughts

There is a palatable evil in Chester’s mind and actions. Why do you think Dickens is evolving the animosity between Haredale and Chester so strongly?

The next thing we know Chester is outside the Golden Key of Varden’s shop. What is he doing there? Why didn’t he come with Varden back to this house? We next see that Sim Tappertit and Chester acquainted. Tappertit whispers the name Joseph Willet in Chester’s ear. With that Sim then escorts Chester into Varden’s parlour and announces Chester to Mrs Varden. Miggs is thrilled and Chester reveals how his turn of phrase can render a woman into a swoon-like state. It is interesting to note that Dolly is not as taken in by Chester's smooth talking. Dolly is distressed by the way Chester looks at her. Do you recall when Dolly could not help but take a couple of peeks at herself in a mirror earlier in the novel? Well, here we see Dolly look away from Chester's glances. I believe there is much more to Dolly than we may think. While she may be mildly interested by Chester's manner, Dolly is not completely smitten by his charms as Miggs and Mrs Varden are.

Chester introduces Ned into the conversation and notes that Dolly is attending very closely to what he is saying. I love the way Chester constantly comments on the importance of being sincere. As reader’s we know that Chester is a very insincere person. The dramatic irony of his conversation is delightful, but somewhat unsettling. Mrs Varden is completely taken in. All she can think about is the importance of being sincere and Protestant. For Dolly, she hears that, according to Mr Chester, Ned has a “roving nature.” Slowly but surely Chester continues to poison Ned and his character to the Varden’s and Miggs. He tells them that “there are grave and weighty reasons, pressing family considerations and ... points of religious difference” that combine to make the union of Emma and Ned “impossible.” Next, in a very insincere manner, Chester comments that Dolly and Mr Varden have been encouraging the union of Emma and Ned. The climax of Chester’s comments comes when he says that Ned is bound by duty and “every solemn tie and obligation to marry some one else.”

We learn that Emma is of “a Catholic family.” As if that was not enough, Chester claims that Ned has “ruinously expensive habits” and if Ned were to marry Emma, then Chester tells Mrs Varden that he would disown his own son that, no doubt, Chester suggests would lead to Emma and Ned’s marriage not lasting a year. At the end of this conversation Mrs Varden “entered into a secret treaty of alliance, offensive and defensive, with her insinuating visitor.” On the other hand, Dolly has little interest in Chester’s words. Three cheers for Dolly!

As the chapter ends we return to Dolly who comments that “Mr Chester is something like Miggs ... For all his politeness and pleasant speaking, I am pretty sure he was making game of us, more than once.” Dolly knows how insincere Miggs is towards her mother. We also learn that Dolly does not believe Chester’s suave conversation and his accusations about Ned. By the end of this chapter it is to Dolly the reader must turn to for clarity and insight.

Thoughts

There are many ways readers could respond to this chapter. Were you amused by the Chester - Mrs Varden conversation, horrified by Mrs Varden’s naiveté, shocked by Chester’s despicable character, encouraged by Dolly’s insightful nature or ... ? Tell us your thoughts.

In this chapter we have a clear reference to the Protestant-Catholic conflict that will become more intense as the novel proceeds. To what extent do you think it was effective that Dickens would introduce the issue through the lens of two young lovers?

The conversation between Chester and Mrs Varden was what I imagine the one between Satan and Eve in the Garden of Eden could have been like. What is your opinion of how Chester conducted himself in their meeting? What weaknesses of Mrs Varden’s character did he exploit?

What is your opinion of Dolly at the end of this chapter? Has it changed from the earlier chapters of the novel?

I have struggled to find the best word or phrase to describe Chester’s character. How would you describe him? What are your reasons for your choice?

Chapter 28

After leaving the locksmith’s house Chester goes to a coffee-house where he has a late dinner and congratulates himself “on his great cleverness.” We read that his waiter was greatly impressed with Chester’s appearance until the bill. The waiter then changed his impression of Chester. In the span of a few sentences Dickens has reinforced the beguiling, yet insincere nature of Chester. What you see is not what lies beneath the surface. Chester ends his evening with a visit to a gaming table. In this chapter we get a glimpse of why Chester’s wallet is not as expansive or impressive as his outward appearance. Upon arriving at his lodgings Chester discovers Hugh asleep on the stairs. Chester stoops down to examine Hugh’s features, and passes his light across his face and looks at Hugh “with a searching eye.”

What follows is very intriguing. It is apparent that Hugh and Chester are already acquainted. Hugh goes into Chester’s rooms and Chester tells Hugh to sit before the fire and take his boots off. How well does Chester know Hugh, and why? Well, let’s see. Chester comments that Hugh has “been drinking again” and Hugh “went down on one knee, and did what he was told.” Hugh calls Chester “master.” Chester calls Hugh a “dull dog” and tells Hugh to fetch his slippers and “tread softly.” Hugh obeys this command “in silence.” This tells me that Chester treats Hugh like a dog and Hugh is quite happy to assume that role for a drink or two. Now settled in, Chester demands “what do you want with me?”

Hugh then recounts that Edward Chester was at the Maypole but could not get to see Emma. He also recounts that Edward had “some letter or some message” for Joe but John Willet had prevented it. Chester is aware that Hugh stole the bracelet and letter. Hugh then gives Chester Dolly’s letter to Emma. Under further questioning of Hugh, Chester learns that Emma walks out alone in the mornings on the footpath before her house. Chester then tells Hugh that if they ever meet in public Hugh is to pretend that he does not to know him. After another drink Hugh leaves.

As our chapter draws to a close we learn the Chester thought he heard Hugh at his door again calling his name. Chester takes up his sword but finds no one in the staircase. After an uneasy hour, Chester falls asleep.

Thoughts

So Chester knows Hugh. What might the purpose and relationship be between Chester and Hugh? To this point in time, how valuable is Hugh to Chester?

How does this chapter further develop the plot?

In the previous chapter I compared Chester to Satan. In this chapter, I find Chester to be like Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello. To what other character from literature would you compare the character of Chester? Why?

Do you see Chester as being a more interesting and well-developed villain than in Dickens’s earlier novels? What are your reasons?

The ending of the chapter puzzles me. What might Dickens be suggesting with the last words that mention a sword in the chapter?

After leaving the locksmith’s house Chester goes to a coffee-house where he has a late dinner and congratulates himself “on his great cleverness.” We read that his waiter was greatly impressed with Chester’s appearance until the bill. The waiter then changed his impression of Chester. In the span of a few sentences Dickens has reinforced the beguiling, yet insincere nature of Chester. What you see is not what lies beneath the surface. Chester ends his evening with a visit to a gaming table. In this chapter we get a glimpse of why Chester’s wallet is not as expansive or impressive as his outward appearance. Upon arriving at his lodgings Chester discovers Hugh asleep on the stairs. Chester stoops down to examine Hugh’s features, and passes his light across his face and looks at Hugh “with a searching eye.”

What follows is very intriguing. It is apparent that Hugh and Chester are already acquainted. Hugh goes into Chester’s rooms and Chester tells Hugh to sit before the fire and take his boots off. How well does Chester know Hugh, and why? Well, let’s see. Chester comments that Hugh has “been drinking again” and Hugh “went down on one knee, and did what he was told.” Hugh calls Chester “master.” Chester calls Hugh a “dull dog” and tells Hugh to fetch his slippers and “tread softly.” Hugh obeys this command “in silence.” This tells me that Chester treats Hugh like a dog and Hugh is quite happy to assume that role for a drink or two. Now settled in, Chester demands “what do you want with me?”

Hugh then recounts that Edward Chester was at the Maypole but could not get to see Emma. He also recounts that Edward had “some letter or some message” for Joe but John Willet had prevented it. Chester is aware that Hugh stole the bracelet and letter. Hugh then gives Chester Dolly’s letter to Emma. Under further questioning of Hugh, Chester learns that Emma walks out alone in the mornings on the footpath before her house. Chester then tells Hugh that if they ever meet in public Hugh is to pretend that he does not to know him. After another drink Hugh leaves.

As our chapter draws to a close we learn the Chester thought he heard Hugh at his door again calling his name. Chester takes up his sword but finds no one in the staircase. After an uneasy hour, Chester falls asleep.

Thoughts

So Chester knows Hugh. What might the purpose and relationship be between Chester and Hugh? To this point in time, how valuable is Hugh to Chester?

How does this chapter further develop the plot?

In the previous chapter I compared Chester to Satan. In this chapter, I find Chester to be like Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello. To what other character from literature would you compare the character of Chester? Why?

Do you see Chester as being a more interesting and well-developed villain than in Dickens’s earlier novels? What are your reasons?

The ending of the chapter puzzles me. What might Dickens be suggesting with the last words that mention a sword in the chapter?

Chapter 29

This chapter begins with what I will term a Dickens Meditation. Have you noticed that Dickens occasionally begins a chapter with a commentary in broad strokes on an issue, feeling, social commentary or philosophical moment? In this chapter Dickens muses on people’s worldly thoughts, and how people often, when looking for the universal truths of life, neglect the commonplace. Dickens concludes this Meditation with the observation that often “our own desires stand between us and our better angels.” What do you think Dickens means in this Meditation? What would you suggest he might be referring to in this Meditation to the novel so far, or this chapter in particular?

After the Meditation Dickens presents us with Chester riding into the countryside. Dickens structures the next couple of paragraphs in idyllic tones of nature’s harmony and “richest melody.” Quite a contrast from our previous chapters of intrigue, hypocrisy, and manipulation. Chester’s destination is the Maypole. Quickly, the idyllic mood is shattered. John Willet bosses and insults Hugh and, for some strange reason, orders Hugh to climb “to the summit of the Maypole.” Willet then remarks on Hugh’s other abilities such as “flinging himself about and never hurting his bones.” What Hugh lacks, according to Willet, is “any imagination.” We then learn that Willet has “grounded” his son. Later, Dickens describes Willet as “a perfect desert in the broad map of his face; one changeless, dull, tremendous blank.” There is no faint praise in this description.

Thoughts

In the short space from the ending of the previous chapter to the beginning of this one Dickens has significantly altered the tone and mood of the novel. From Chester's disquieting night with a sword in his hand and struggling to find sleep in his rooms to this morning’s idyllic ride in the country to the Maypole Chester continues to serve as our focus. Hugh acts as if he does not know Chester; for his part, John Willet fawns over Chester, bullies Hugh, and is quite pleased with himself for grounding his son. Why would Dickens make such an abrupt transition?

Did you note the description of John Willet? What might be the broader and deeper symbolic suggestion be behind Willet’s physical description? How does Willet reflect the Maypole? (And the Maypole its owner?)

Chester takes himself to the path where he knows from Hugh that Emma Haredale will be found walking. He finds her and asks to speak with her. How can she say no when his voice has the “faint echo of one she knew so well.” Chester manoeuvres her to a quiet place and begins his deception. Emma, for her part, keeps her head lowered in a suggestive pose of both a lady who is with a gentleman and, more accurately perhaps, an attitude of deference and submission. All in all, with the nature of Chester well known to us and Emma the innocent, delicate person she is, and the isolated location of their meeting, I am again feeling an allusion to the Garden of Eden. Emma does defend Edward, but she is no match for Mr Chester. He detains her “with a gentle hand, and besought her in such persuasive accents ... that she was easily prevailed upon to comply, and so sat down again.” In a grand act of deception and deceit, Chester produces crocodile tears, brings anguish into his voice, and claims it is his duty to tell her she is deceived “by your unworthy lover, and my unworthy son.” Emma struggles to maintain her faith in Ned. Chester presses on. Emma cries. Chester tells her that Ned has broken his faith to her. Chester again bends “over her more affectionately.” Chester tells her that Ned has a letter that will explain his poverty, and that he can no longer “pursue his claim upon her hand.” At this point Haredale appears. Emma leaves in tears and the enemies confront each other.

Thoughts

Is there no end to the lies, deceit, and cruelty of Chester? Actually, should I turn the tables? To what extent could one see merit in any of Chester's claims and actions? Can his actions, in the timeframe of the historical setting, be accepted or understood at all?

Why is Chester going to all this trouble anyway?

Is it me, or was there, yet again, allusions to the Garden of Eden?

Did you notice the physical interplay between Chester and Emma? He is repeatedly seen as leaning over her, hovering. His voice is hypnotic, his interest in her seems to smoulder. To what extent do you think Dickens had the intent of introducing a sexually charged aura to the scene? I am wondering if there are are sexual undertones in Hugh’s actions towards Dolly and now Chester's towards Emma. What would be Dickens purpose, if indeed my suggestion has any validity?

Chester tells Haredale about the letter that is on his desk that will break Emma’s heart. Chester claims he was simply acting in good faith to mitigate the pain of their children breaking up. When Haredale leaves the area we learn a great deal about the past relationship between Haredale and Chester. They went to school together, and Haredale was unable to”keep his mistress when he had won her, and threw me in her way to carry off the prize ... fortune has always been with me.”

The chapter ends on an ominous note. There is the distinct hint that these two men are not finished with each other yet. Hester draws his sword as he leaves the area and in “absent humour ran his eye from hilt to point full twenty times.”

Thoughts

Ouch! Is this a chapter that ends on a note of suspense and foreshadowing or what? Given the various and important events that have occurred in this chapter tell us what you would expect might occur before the novel is complete.

This chapter begins with what I will term a Dickens Meditation. Have you noticed that Dickens occasionally begins a chapter with a commentary in broad strokes on an issue, feeling, social commentary or philosophical moment? In this chapter Dickens muses on people’s worldly thoughts, and how people often, when looking for the universal truths of life, neglect the commonplace. Dickens concludes this Meditation with the observation that often “our own desires stand between us and our better angels.” What do you think Dickens means in this Meditation? What would you suggest he might be referring to in this Meditation to the novel so far, or this chapter in particular?

After the Meditation Dickens presents us with Chester riding into the countryside. Dickens structures the next couple of paragraphs in idyllic tones of nature’s harmony and “richest melody.” Quite a contrast from our previous chapters of intrigue, hypocrisy, and manipulation. Chester’s destination is the Maypole. Quickly, the idyllic mood is shattered. John Willet bosses and insults Hugh and, for some strange reason, orders Hugh to climb “to the summit of the Maypole.” Willet then remarks on Hugh’s other abilities such as “flinging himself about and never hurting his bones.” What Hugh lacks, according to Willet, is “any imagination.” We then learn that Willet has “grounded” his son. Later, Dickens describes Willet as “a perfect desert in the broad map of his face; one changeless, dull, tremendous blank.” There is no faint praise in this description.

Thoughts

In the short space from the ending of the previous chapter to the beginning of this one Dickens has significantly altered the tone and mood of the novel. From Chester's disquieting night with a sword in his hand and struggling to find sleep in his rooms to this morning’s idyllic ride in the country to the Maypole Chester continues to serve as our focus. Hugh acts as if he does not know Chester; for his part, John Willet fawns over Chester, bullies Hugh, and is quite pleased with himself for grounding his son. Why would Dickens make such an abrupt transition?

Did you note the description of John Willet? What might be the broader and deeper symbolic suggestion be behind Willet’s physical description? How does Willet reflect the Maypole? (And the Maypole its owner?)

Chester takes himself to the path where he knows from Hugh that Emma Haredale will be found walking. He finds her and asks to speak with her. How can she say no when his voice has the “faint echo of one she knew so well.” Chester manoeuvres her to a quiet place and begins his deception. Emma, for her part, keeps her head lowered in a suggestive pose of both a lady who is with a gentleman and, more accurately perhaps, an attitude of deference and submission. All in all, with the nature of Chester well known to us and Emma the innocent, delicate person she is, and the isolated location of their meeting, I am again feeling an allusion to the Garden of Eden. Emma does defend Edward, but she is no match for Mr Chester. He detains her “with a gentle hand, and besought her in such persuasive accents ... that she was easily prevailed upon to comply, and so sat down again.” In a grand act of deception and deceit, Chester produces crocodile tears, brings anguish into his voice, and claims it is his duty to tell her she is deceived “by your unworthy lover, and my unworthy son.” Emma struggles to maintain her faith in Ned. Chester presses on. Emma cries. Chester tells her that Ned has broken his faith to her. Chester again bends “over her more affectionately.” Chester tells her that Ned has a letter that will explain his poverty, and that he can no longer “pursue his claim upon her hand.” At this point Haredale appears. Emma leaves in tears and the enemies confront each other.

Thoughts

Is there no end to the lies, deceit, and cruelty of Chester? Actually, should I turn the tables? To what extent could one see merit in any of Chester's claims and actions? Can his actions, in the timeframe of the historical setting, be accepted or understood at all?

Why is Chester going to all this trouble anyway?

Is it me, or was there, yet again, allusions to the Garden of Eden?

Did you notice the physical interplay between Chester and Emma? He is repeatedly seen as leaning over her, hovering. His voice is hypnotic, his interest in her seems to smoulder. To what extent do you think Dickens had the intent of introducing a sexually charged aura to the scene? I am wondering if there are are sexual undertones in Hugh’s actions towards Dolly and now Chester's towards Emma. What would be Dickens purpose, if indeed my suggestion has any validity?

Chester tells Haredale about the letter that is on his desk that will break Emma’s heart. Chester claims he was simply acting in good faith to mitigate the pain of their children breaking up. When Haredale leaves the area we learn a great deal about the past relationship between Haredale and Chester. They went to school together, and Haredale was unable to”keep his mistress when he had won her, and threw me in her way to carry off the prize ... fortune has always been with me.”

The chapter ends on an ominous note. There is the distinct hint that these two men are not finished with each other yet. Hester draws his sword as he leaves the area and in “absent humour ran his eye from hilt to point full twenty times.”

Thoughts

Ouch! Is this a chapter that ends on a note of suspense and foreshadowing or what? Given the various and important events that have occurred in this chapter tell us what you would expect might occur before the novel is complete.

Chapter 30

As we begin this chapter Dickens is musing on the relations between old John Willet and his son Joe. John Willet is both domineering and demeaning to his son. The more he denigrates his son the more John seems to enjoy it. John “was impelled to these exercises of authority by the applause and admiration of his Maypole cronies” who wished there were more people like father John.” One wonders what type of parent each of John’s cronies were. I imagine John and his friends all were the same. Collectively, they represent the rigidity of the past, those who saw the future not from a forward perspective, but from a backwards looking mirror. The presence of Chester further spurs John to humiliate his son Joe. Here we see how Dickens overlaps his focus on the relationships between fathers and sons. Chester has just left the Warren where he has also denigrated his son. While Chester's words were much smoother than Willet’s crude nature, the wounds made by both parents are equally deep and hurtful. This opening scene is very effective as it marries the tone and theme of the previous chapter to this one. Humiliated, Joe retreats to his room and reflects that if it were not for Dolly and the thought of how she would respond to his running away from the Maypole “I should part tonight.”

When Willet returns to the common room of the Maypole Solomon Daisy congratulates him on how he treated Joe. Still enervated by his own self-importance John tells Daisy to hold his tongue. This deflates the mood of the Maypole’s patrons. Willet, pleased with himself, enjoys his pipe. Joe Willet defends himself when Mr. Cobb also congratulates John Willet’s treatment of his son. At this point Joe has had enough abuse. After more taunts from Cobb which proved too much “for flesh and blood to bear” Joe overturns a table and pummels him soundly. Joe then leaves the room. The chapter ends with Joe saying “I have done it now ... . The Maypole and I must part company ... it’s all over.”

Thoughts

A short chapter in length, but, I feel, a major step forward in the story. First, we have the not so subtle pairing of fathers against sons again. While Ned is not fully aware that his father has been destroying his character while Joe is painfully aware that his father has, both father-son pairings are effectively presented. Can you suggest any redeeming qualities for John Willet? What might Dickens’s purpose be in creating such conflict?

In this chapter we see Joe finally take a stand on the treatment he is subjected to by both his father and the other regulars at the Maypole. What is your opinion of Joe at this point of the novel?

While Dolly does not appear in this chapter, she is, nevertheless, a focal point in Joe’s life. How mature and sincere do you think Joe’s feelings are towards Dolly?

Reflections

This week’s chapters have propelled the story forward in several ways. Chester’s character has been further developed. What an odious person, and yet so slick. To me, he is being presented as a Satanic figure. I keep feeling echoes of Satan and the Garden of Eden. His words, appearance, and manner all present him as one who knows human nature, the flaws of humans, and the way to seduce another human being to his own goals. On the other hand, John Willet is brash, bold, and verbally and physically aggressive. The pairing of these two fathers is stark in contrast. Still, they seem, at the moment, to have the upper hand over their sons. Different methods and motives perhaps, but this study in contrasts must be leading us somewhere. It will be interesting to see how Dickens develops these father-son pairings.

Dolly and Emma, while not present for large portions of this week’s chapters, are still important drivers of the story. How will they effect the natures and activities of Ned and Joe?

It seems every novel we read I stumble across a character or two I intensely dislike. In Barnaby Rudge they are John Willet and Chester. I wonder what Dickens has in store for them later in the novel. Time will tell.

As we begin this chapter Dickens is musing on the relations between old John Willet and his son Joe. John Willet is both domineering and demeaning to his son. The more he denigrates his son the more John seems to enjoy it. John “was impelled to these exercises of authority by the applause and admiration of his Maypole cronies” who wished there were more people like father John.” One wonders what type of parent each of John’s cronies were. I imagine John and his friends all were the same. Collectively, they represent the rigidity of the past, those who saw the future not from a forward perspective, but from a backwards looking mirror. The presence of Chester further spurs John to humiliate his son Joe. Here we see how Dickens overlaps his focus on the relationships between fathers and sons. Chester has just left the Warren where he has also denigrated his son. While Chester's words were much smoother than Willet’s crude nature, the wounds made by both parents are equally deep and hurtful. This opening scene is very effective as it marries the tone and theme of the previous chapter to this one. Humiliated, Joe retreats to his room and reflects that if it were not for Dolly and the thought of how she would respond to his running away from the Maypole “I should part tonight.”

When Willet returns to the common room of the Maypole Solomon Daisy congratulates him on how he treated Joe. Still enervated by his own self-importance John tells Daisy to hold his tongue. This deflates the mood of the Maypole’s patrons. Willet, pleased with himself, enjoys his pipe. Joe Willet defends himself when Mr. Cobb also congratulates John Willet’s treatment of his son. At this point Joe has had enough abuse. After more taunts from Cobb which proved too much “for flesh and blood to bear” Joe overturns a table and pummels him soundly. Joe then leaves the room. The chapter ends with Joe saying “I have done it now ... . The Maypole and I must part company ... it’s all over.”

Thoughts

A short chapter in length, but, I feel, a major step forward in the story. First, we have the not so subtle pairing of fathers against sons again. While Ned is not fully aware that his father has been destroying his character while Joe is painfully aware that his father has, both father-son pairings are effectively presented. Can you suggest any redeeming qualities for John Willet? What might Dickens’s purpose be in creating such conflict?

In this chapter we see Joe finally take a stand on the treatment he is subjected to by both his father and the other regulars at the Maypole. What is your opinion of Joe at this point of the novel?

While Dolly does not appear in this chapter, she is, nevertheless, a focal point in Joe’s life. How mature and sincere do you think Joe’s feelings are towards Dolly?

Reflections

This week’s chapters have propelled the story forward in several ways. Chester’s character has been further developed. What an odious person, and yet so slick. To me, he is being presented as a Satanic figure. I keep feeling echoes of Satan and the Garden of Eden. His words, appearance, and manner all present him as one who knows human nature, the flaws of humans, and the way to seduce another human being to his own goals. On the other hand, John Willet is brash, bold, and verbally and physically aggressive. The pairing of these two fathers is stark in contrast. Still, they seem, at the moment, to have the upper hand over their sons. Different methods and motives perhaps, but this study in contrasts must be leading us somewhere. It will be interesting to see how Dickens develops these father-son pairings.

Dolly and Emma, while not present for large portions of this week’s chapters, are still important drivers of the story. How will they effect the natures and activities of Ned and Joe?

It seems every novel we read I stumble across a character or two I intensely dislike. In Barnaby Rudge they are John Willet and Chester. I wonder what Dickens has in store for them later in the novel. Time will tell.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 26

Peter wrote: "Chapter 26The chapter ends with Chester presenting the key of the house to Haredale who it turns out is the owner of the tenement...."

We learned last week that Haredale was supporting the Rudges since the murder of Mary's husband. It's no surprise that Haredale would also provide her with modest housing. This is one connection that is completely plausible. More and more we're seeing that he is a good and decent man.

I was interested to see that Varden had courted Mary, and she'd rejected him for Barnaby's father. Surely we will hear more about this in the weeks to come. Varden and Haredale both have fond memories of Mary in her youth. Poor Gabriel's heart must have been quite broken for him to have landed in Martha's arms!

Peter wrote: "What purpose might Dickens have for repeatedly presenting these characters to the reader?

The deeper we get, the more I wonder how the story will play out in a way that Barnaby deserves to have the novel named for him. At this point everything focuses on Haredale, Varden, and especially Chester. When trying to figure out where Dickens will take us, I keep this in mind. Barnaby will surely be the hub in this wheel.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 27

Peter wrote: "Chapter 27Dolly is distressed by the way Chester looks at her. Do you recall when Dolly could not help but take a couple of peeks at herself in a mirror earlier in the novel? ... What is your opinion of Dolly at the end of this chapter?"

Envy them though we might, it' a double-edged sword to be a beautiful woman. Between Dolly and Kate Nickleby, my skin crawls at all the leering and lechery.

I've been pondering your question about my opinion of Dolly and how it's changing. I think my opinion of Dolly changes as she does. It's quite astonishing, really. Dickens is showing her growing and maturing before the readers' eyes, from a silly coquette to a savvy woman. For better or worse, events have taken away her innocence. I look forward to rereading Our Mutual Friend because I think Bella Wilfer transformed from girl to woman, also. It would be interesting to compare the two, but I know I'll have forgotten much about Dolly by the time we return to Bella!

Peter wrote: "Were you amused by the Chester - Mrs Varden conversation, horrified by Mrs Varden’s naiveté, shocked by Chester’s despicable character, encouraged by Dolly’s insightful nature or ... ?"

Fascinated! People are so easily manipulated, especially if one knows their soft spots, and even more especially if one has no conscience! With Hugh and Sim's help, Chester knows just what buttons to push. It's really quite masterful. Despicable, but masterful. Your comparison to the snake in Eden is, I'm afraid, right on target.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 29

Peter wrote: "Chapter 29...we learn a great deal about the past relationship between Haredale and Chester. ....Chester draws his sword as he leaves the area ..."

I believe this is the 3rd mention of Chester's sword, the other two being when he thought about using it as a last resort on Haredale, and then again when he thought Hugh was lurking on his steps. You all taught me about Chekhov's Gun (the literary principle that everything that is introduced in a story needs to have a function), and I think here we could refer to it as "Chester's Sword". That sword is going to be used before our story is over, and I wonder if it hasn't been used sometime in the past, as well.

I wonder if I'll see echoes of the Cheerybles (from Nicholas Nickleby) in the relationship between Ned and Haredale. Was Ned's mother the woman who came between Chester and Haredale? Will Haredale soften towards Ned when he realizes that Ned has his mother's character and is nothing like his sleezy father? (I just had a flash of speculation about how all of this might play out. I shan't share it, in case I'm actually correct.)

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 27

Dolly is distressed by the way Chester looks at her. Do you recall when Dolly could not help but take a couple of peeks at herself in a mirror earlier in the novel? ... Wh..."

Hi Mary Lou

Yes. Dolly is a very interesting character. She is maturing as we read through the novel. I too hope her character progression continues as it is always extra pleasant to see Dickens create a female character with some depth and interest. Still, I ask myself, why oh why did Dickens call her Dolly?

Your comments about Bella and her transformation have set me to thinking. Moving among the various novels and thinking about their connections, how Dickens evolves as a novelist, and how he introduces and incorporates symbolism and foreshadowing is fascinating.

Chester’s sword, as you note, has already made multiple appearances. I don’t think we have read the last of it either.

Dolly is distressed by the way Chester looks at her. Do you recall when Dolly could not help but take a couple of peeks at herself in a mirror earlier in the novel? ... Wh..."

Hi Mary Lou

Yes. Dolly is a very interesting character. She is maturing as we read through the novel. I too hope her character progression continues as it is always extra pleasant to see Dickens create a female character with some depth and interest. Still, I ask myself, why oh why did Dickens call her Dolly?

Your comments about Bella and her transformation have set me to thinking. Moving among the various novels and thinking about their connections, how Dickens evolves as a novelist, and how he introduces and incorporates symbolism and foreshadowing is fascinating.

Chester’s sword, as you note, has already made multiple appearances. I don’t think we have read the last of it either.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 30

Peter wrote: "Chapter 30It seems every novel we read I stumble across a character or two I intensely dislike. In Barnaby Rudge they John Willet and Chester..."

Chester is certainly to be loathed. John Willet, though, is more to be pitied, I think. Whether he's cognizant of it or not, I think he senses that he's a big fish in a tiny pond, and that Joe has the world and the future at his disposal. John may be feeling a bit of competition with his son, and realizes Joe is the better man. (Pop culture alert! ... ) I'm reminded of two real fathers and sons - Jack and David Cassidy, and Joe and Danny Bonoduce (yes - from the Partridge Family. Don't judge.) Jack was a famous actor but incredibly jealous of David's fame, as his own was fizzling. And Joe was a TV writer and producer, also jealous of his child's success, resulting in both physical and emotional abuse. Frankly, I see the same thing with Martha and Dolly -- Martha is definitely envious of Dolly's youth and beauty, and probably the close relationship she has with Gabriel, as well.

As for the Maypole gang, I think we're seeing a microcosm of the riots to come. There seems to be a mob mentality when John picks on poor Joe and his cronies all pile on. I bet they'd be kinder to Joe, and perhaps even take his side, if they were with him one on one.

Do you remember the first conversation between Haredale and Chester we witnessed? We learnt that they have been enemies for a long time although they used to be friends. Chester also talks about his wife as a woman whose family had some riches but no high social connections and were willing to marry her off to a man with high connections. I think he said that when he first acquainted his son Ned with his intentions of making him a fortune-hunter.

From these two details I guess that what Mary Lou suggests is probably true: Haredale lost his beloved one to Chester, because the family of the bride wanted to drive a bargain - a bit like all those bargains in Nicholas Nickleby.

Interestingly, this creates a parallel between Haredale and Varden, whom he calls his friend: They both loved, and lost.

From these two details I guess that what Mary Lou suggests is probably true: Haredale lost his beloved one to Chester, because the family of the bride wanted to drive a bargain - a bit like all those bargains in Nicholas Nickleby.

Interestingly, this creates a parallel between Haredale and Varden, whom he calls his friend: They both loved, and lost.

Mary Lou wrote: "As for the Maypole gang, I think we're seeing a microcosm of the riots to come. There seems to be a mob mentality when John picks on poor Joe and his cronies all pile on...."

Mary Lou wrote: "As for the Maypole gang, I think we're seeing a microcosm of the riots to come. There seems to be a mob mentality when John picks on poor Joe and his cronies all pile on...."Yes, and notice also that once John thinks he's getting away with bullying Joe, he then starts bullying Solomon Daisy as well. If you don't check a tyrant, he becomes more tyrannical. Even toward his cronies.

I also find Chester snakelike. He is so cold-blooded and slippery. He might be my favorite Dickens villain so far, and that's not without competition: Bill Sykes, Ralph Nickleby, Nell's horrible granddad. (I'm not counting Quilp. He was just a caricature.)

I also find Chester snakelike. He is so cold-blooded and slippery. He might be my favorite Dickens villain so far, and that's not without competition: Bill Sykes, Ralph Nickleby, Nell's horrible granddad. (I'm not counting Quilp. He was just a caricature.)Can I take a moment to say how much I like Gabriel's speech about Time?

Also it's interesting to me, with the riots coming, to see the way the Protestant Manual's being undermined by its association with Mrs. Varden.

That thing with John asking Hugh to hang his wig up on a pole was just bizarre. What a strange way to demonstrate your power. Especially when Hugh grabs it "in a manner so unceremonious and hasty that the action discomposed Mr Willet not a little." Tyrants need to be careful what they wish for.

Peter wrote: "The conversation between Chester and Mrs Varden was what I imagine the one between Satan and Eve in the Garden of Eden could have been like. What is your opinion of how Chester conducted himself in their meeting? What weaknesses of Mrs Varden’s character did he exploit?"

A couple of them, but I think they can be swept together as 'vanity' and false pride. He butters her up with telling her she looks so young - and, thereby, indirectly, telling Dolly she looks old, by comparing her to her mother in that way. I'd be ... a bit less inclined to like what he had to say as well ;-) He also implies that she is a good mother if she thinks like he does, and smart, and wise etc.

I'm not sure about the exact wording anymore, but didn't Barnaby say in an earlier chapter that he'd rather be a happy idiot than wise and in misery? I wonder if that points towards the misery that will come of Mrs. Varden thinking she is so wise and good listening to this snake of a man.

A couple of them, but I think they can be swept together as 'vanity' and false pride. He butters her up with telling her she looks so young - and, thereby, indirectly, telling Dolly she looks old, by comparing her to her mother in that way. I'd be ... a bit less inclined to like what he had to say as well ;-) He also implies that she is a good mother if she thinks like he does, and smart, and wise etc.

I'm not sure about the exact wording anymore, but didn't Barnaby say in an earlier chapter that he'd rather be a happy idiot than wise and in misery? I wonder if that points towards the misery that will come of Mrs. Varden thinking she is so wise and good listening to this snake of a man.

Tristram wrote: "Do you remember the first conversation between Haredale and Chester we witnessed? We learnt that they have been enemies for a long time although they used to be friends. Chester also talks about hi..."

Yes. There are many lovers, both past and present. While our focus is primarily on the unfolding relationships of Ned - Emma and Joe/Sim - Dolly there are the lovers and losers of the past including Chester, Haredale, Varden, and Mrs Rudge. Dickens has made the interconnections. Now we must wait and see how he unravels and reveals the consequences of these relationships.

Yes. There are many lovers, both past and present. While our focus is primarily on the unfolding relationships of Ned - Emma and Joe/Sim - Dolly there are the lovers and losers of the past including Chester, Haredale, Varden, and Mrs Rudge. Dickens has made the interconnections. Now we must wait and see how he unravels and reveals the consequences of these relationships.

Julie wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "As for the Maypole gang, I think we're seeing a microcosm of the riots to come. There seems to be a mob mentality when John picks on poor Joe and his cronies all pile on...."

Yes,..."

Julie and Mary Lou

We are waiting for the Gordon Riots. Your comments are very helpful and suggestive. Tyrants and Riots evolve from many reasons and in many situations. The actions and tussles in the Maypole are very suggestive of what is to come on a much larger scale.

Yes,..."

Julie and Mary Lou

We are waiting for the Gordon Riots. Your comments are very helpful and suggestive. Tyrants and Riots evolve from many reasons and in many situations. The actions and tussles in the Maypole are very suggestive of what is to come on a much larger scale.

Peter wrote: "Now we must wait and see how he unravels and reveals the consequences of these relationships."

Peter wrote: "Now we must wait and see how he unravels and reveals the consequences of these relationships."The connections are all very beautifully complicated in this novel, I think.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "Now we must wait and see how he unravels and reveals the consequences of these relationships."

The connections are all very beautifully complicated in this novel, I think."

Absolutely. It makes me glad I decided to pick it up anyway, although I started late. I must admit I would probably have missed a lot of interesting connections, symbols and foreshadowing on my own.

The connections are all very beautifully complicated in this novel, I think."

Absolutely. It makes me glad I decided to pick it up anyway, although I started late. I must admit I would probably have missed a lot of interesting connections, symbols and foreshadowing on my own.

Mr. Chester making an impression

Chapter 27

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

As Mrs Varden distinctly heard, and was intended to hear, all that Miggs said, and as these words appeared to convey in metaphorical terms a presage or foreboding that she would at some early period droop beneath her trials and take an easy flight towards the stars, she immediately began to languish, and taking a volume of the Manual from a neighbouring table, leant her arm upon it as though she were Hope and that her Anchor. Mr Chester perceiving this, and seeing how the volume was lettered on the back, took it gently from her hand, and turned the fluttering leaves.

‘My favourite book, dear madam. How often, how very often in his early life—before he can remember’—(this clause was strictly true) ‘have I deduced little easy moral lessons from its pages, for my dear son Ned! You know Ned?’

Mrs Varden had that honour, and a fine affable young gentleman he was.

‘You’re a mother, Mrs Varden,’ said Mr Chester, taking a pinch of snuff, ‘and you know what I, as a father, feel, when he is praised. He gives me some uneasiness—much uneasiness—he’s of a roving nature, ma’am—from flower to flower—from sweet to sweet—but his is the butterfly time of life, and we must not be hard upon such trifling.’

He glanced at Dolly. She was attending evidently to what he said. Just what he desired!

‘The only thing I object to in this little trait of Ned’s, is,’ said Mr Chester, ‘—and the mention of his name reminds me, by the way, that I am about to beg the favour of a minute’s talk with you alone—the only thing I object to in it, is, that it DOES partake of insincerity. Now, however I may attempt to disguise the fact from myself in my affection for Ned, still I always revert to this—that if we are not sincere, we are nothing. Nothing upon earth. Let us be sincere, my dear madam—’

‘—and Protestant,’ murmured Mrs Varden.

‘—and Protestant above all things. Let us be sincere and Protestant, strictly moral, strictly just (though always with a leaning towards mercy), strictly honest, and strictly true, and we gain—it is a slight point, certainly, but still it is something tangible; we throw up a groundwork and foundation, so to speak, of goodness, on which we may afterwards erect some worthy superstructure.’

Now, to be sure, Mrs Varden thought, here is a perfect character. Here is a meek, righteous, thoroughgoing Christian, who, having mastered all these qualities, so difficult of attainment; who, having dropped a pinch of salt on the tails of all the cardinal virtues, and caught them every one; makes light of their possession, and pants for more morality. For the good woman never doubted (as many good men and women never do), that this slighting kind of profession, this setting so little store by great matters, this seeming to say, ‘I am not proud, I am what you hear, but I consider myself no better than other people; let us change the subject, pray’—was perfectly genuine and true. He so contrived it, and said it in that way that it appeared to have been forced from him, and its effect was marvellous.

Aware of the impression he had made—few men were quicker than he at such discoveries—Mr Chester followed up the blow by propounding certain virtuous maxims, somewhat vague and general in their nature, doubtless, and occasionally partaking of the character of truisms, worn a little out at elbow, but delivered in so charming a voice and with such uncommon serenity and peace of mind, that they answered as well as the best. Nor is this to be wondered at; for as hollow vessels produce a far more musical sound in falling than those which are substantial, so it will oftentimes be found that sentiments which have nothing in them make the loudest ringing in the world, and are the most relished.

Mr Chester, with the volume gently extended in one hand, and with the other planted lightly on his breast, talked to them in the most delicious manner possible; and quite enchanted all his hearers, notwithstanding their conflicting interests and thoughts. Even Dolly, who, between his keen regards and her eyeing over by Mr Tappertit, was put quite out of countenance, could not help owning within herself that he was the sweetest-spoken gentleman she had ever seen. Even Miss Miggs, who was divided between admiration of Mr Chester and a mortal jealousy of her young mistress, had sufficient leisure to be propitiated. Even Mr Tappertit, though occupied as we have seen in gazing at his heart’s delight, could not wholly divert his thoughts from the voice of the other charmer. Mrs Varden, to her own private thinking, had never been so improved in all her life; and when Mr Chester, rising and craving permission to speak with her apart, took her by the hand and led her at arm’s length upstairs to the best sitting-room, she almost deemed him something more than human.

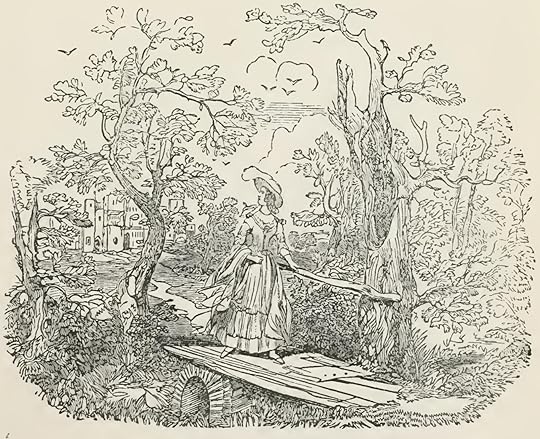

Miss Haredale on the bridge

Chapter 29

George Cattermole

Text Illustrated:

Lest it should be matter of surprise to any, that Mr Willet adopted this bold course in opposition to one whom he had often entertained, and who had always paid his way at the Maypole gallantly, it may be remarked that it was his very penetration and sagacity in this respect, which occasioned him to indulge in those unusual demonstrations of jocularity, just now recorded. For Mr Willet, after carefully balancing father and son in his mental scales, had arrived at the distinct conclusion that the old gentleman was a better sort of a customer than the young one. Throwing his landlord into the same scale, which was already turned by this consideration, and heaping upon him, again, his strong desires to run counter to the unfortunate Joe, and his opposition as a general principle to all matters of love and matrimony, it went down to the very ground straightway, and sent the light cause of the younger gentleman flying upwards to the ceiling. Mr Chester was not the kind of man to be by any means dim-sighted to Mr Willet’s motives, but he thanked him as graciously as if he had been one of the most disinterested martyrs that ever shone on earth; and leaving him, with many complimentary reliances on his great taste and judgment, to prepare whatever dinner he might deem most fitting the occasion, bent his steps towards the Warren.

Dressed with more than his usual elegance; assuming a gracefulness of manner, which, though it was the result of long study, sat easily upon him and became him well; composing his features into their most serene and prepossessing expression; and setting in short that guard upon himself, at every point, which denoted that he attached no slight importance to the impression he was about to make; he entered the bounds of Miss Haredale’s usual walk. He had not gone far, or looked about him long, when he descried coming towards him, a female figure. A glimpse of the form and dress as she crossed a little wooden bridge which lay between them, satisfied him that he had found her whom he desired to see. He threw himself in her way, and a very few paces brought them close together.

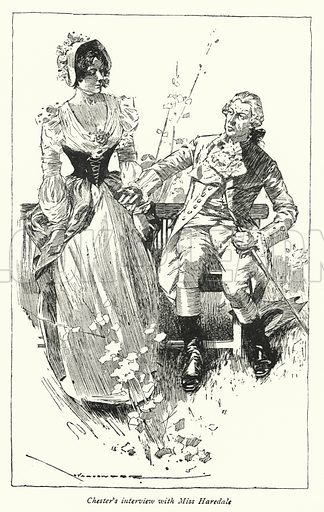

Mr. Chester's interview with Miss Haredale

Chapter 29

Max Cowper

Text Ilustrated:

He raised his hat from his head, and yielding the path, suffered her to pass him. Then, as if the idea had but that moment occurred to him, he turned hastily back and said in an agitated voice:

‘I beg pardon—do I address Miss Haredale?’

She stopped in some confusion at being so unexpectedly accosted by a stranger; and answered ‘Yes.’

‘Something told me,’ he said, LOOKING a compliment to her beauty, ‘that it could be no other. Miss Haredale, I bear a name which is not unknown to you—which it is a pride, and yet a pain to me to know, sounds pleasantly in your ears. I am a man advanced in life, as you see. I am the father of him whom you honour and distinguish above all other men. May I for weighty reasons which fill me with distress, beg but a minute’s conversation with you here?’

Who that was inexperienced in deceit, and had a frank and youthful heart, could doubt the speaker’s truth—could doubt it too, when the voice that spoke, was like the faint echo of one she knew so well, and so much loved to hear? She inclined her head, and stopping, cast her eyes upon the ground.

‘A little more apart—among these trees. It is an old man’s hand, Miss Haredale; an honest one, believe me.’

She put hers in it as he said these words, and suffered him to lead her to a neighbouring seat.

Max Cowper (1860-1911) was a British illustrator who worked for magazines such as Black & White and The Strand Magazine.

In 1898, he did 7 illustrations for Arthur Conan Doyle's short story The Story of the Lost Special.

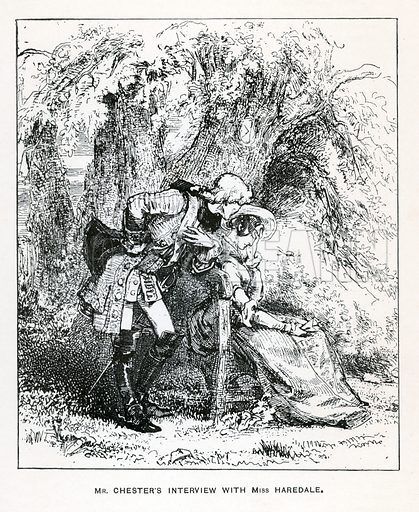

Mr. Chester's Interview With Miss Haredale

Chapter 29

It says this illustration is by Phiz, but I have my doubts. It doesn't look like Phiz to me, and perhaps more importantly it says it is from Caxton Publishing c. 1900, which would mean Phiz would have made this illustration about twenty years after he died.

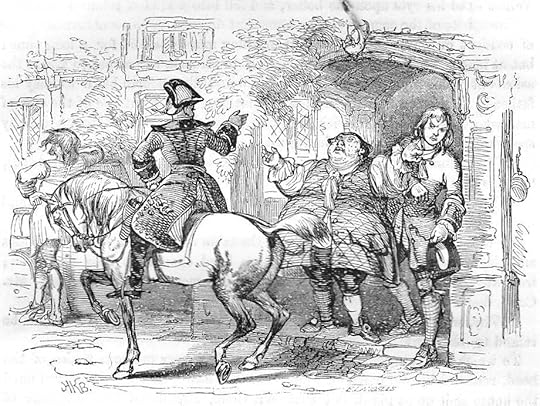

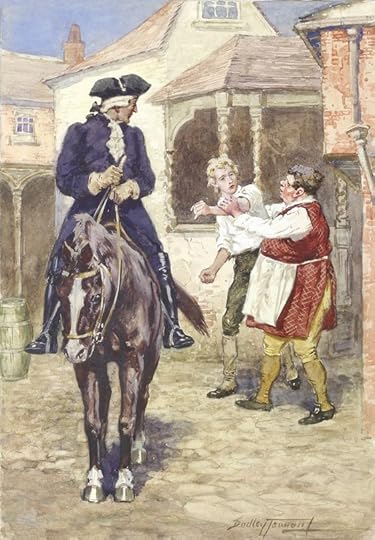

Old John restrains his son

Chapter 30

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

This had come to be the recognised and established state of things; but as John was very anxious to flourish his supremacy before the eyes of Mr Chester, he did that day exceed himself, and did so goad and chafe his son and heir, that but for Joe’s having made a solemn vow to keep his hands in his pockets when they were not otherwise engaged, it is impossible to say what he might have done with them. But the longest day has an end, and at length Mr Chester came downstairs to mount his horse, which was ready at the door.

As old John was not in the way at the moment, Joe, who was sitting in the bar ruminating on his dismal fate and the manifold perfections of Dolly Varden, ran out to hold the guest’s stirrup and assist him to mount. Mr Chester was scarcely in the saddle, and Joe was in the very act of making him a graceful bow, when old John came diving out of the porch, and collared him.

‘None of that, sir,’ said John, ‘none of that, sir. No breaking of patroles. How dare you come out of the door, sir, without leave? You’re trying to get away, sir, are you, and to make a traitor of yourself again? What do you mean, sir?’

‘Let me go, father,’ said Joe, imploringly, as he marked the smile upon their visitor’s face, and observed the pleasure his disgrace afforded him. ‘This is too bad. Who wants to get away?’

‘Who wants to get away!’ cried John, shaking him. ‘Why you do, sir, you do. You’re the boy, sir,’ added John, collaring with one hand, and aiding the effect of a farewell bow to the visitor with the other, ‘that wants to sneak into houses, and stir up differences between noble gentlemen and their sons, are you, eh? Hold your tongue, sir.’

Joe made no effort to reply. It was the crowning circumstance of his degradation. He extricated himself from his father’s grasp, darted an angry look at the departing guest, and returned into the house.

‘But for her,’ thought Joe, as he threw his arms upon a table in the common room, and laid his head upon them, ‘but for Dolly, who I couldn’t bear should think me the rascal they would make me out to be if I ran away, this house and I should part to-night.’

Joe Willet and his father, with Sir John Chester looking on.

From Barnaby Rudge: Told to Children, by Ethel Lindsay. S.W. Partridge & Co., 1921

Artist Dudley Tennant

Devonshire Terrace.

Twenty Third February.

My Dear Macready.

If I am to see anything of you in your coming holidays, I must be a Spartan now.

My labours press so heavily upon me at this time – the end of the Second Volume bringing with it a necessity for speed – that tomorrow morning I shall be on the box of a Brighton coach, and for a week afterwards shut up alone in the Old Ship Hotel, working with the energy of fourteen Dragons.

Drink my health in my absence – wish well to Barnaby, though he does drive me away – and oh do not – do not – curse me.

With that cue for slow music and closing in with a picture, bring down the envelope.

Always My Dear Macready

Faithfully Yours

Charles Dickens

Best regards at home. We have a clean bill of health here.

Twenty Third February.

My Dear Macready.

If I am to see anything of you in your coming holidays, I must be a Spartan now.

My labours press so heavily upon me at this time – the end of the Second Volume bringing with it a necessity for speed – that tomorrow morning I shall be on the box of a Brighton coach, and for a week afterwards shut up alone in the Old Ship Hotel, working with the energy of fourteen Dragons.

Drink my health in my absence – wish well to Barnaby, though he does drive me away – and oh do not – do not – curse me.

With that cue for slow music and closing in with a picture, bring down the envelope.

Always My Dear Macready

Faithfully Yours

Charles Dickens

Best regards at home. We have a clean bill of health here.

Jantine wrote: "I'm not sure about the exact wording anymore, but didn't Barnaby say in an earlier chapter that he'd rather be a happy idiot than wise and in misery? I wonder if that points towards the misery that will come of Mrs. Varden thinking she is so wise and good listening to this snake of a man."

Jantine,

I really like that connection, and it is one I would have missed if you had not pointed it out. And fancy Barnaby's making this Erasmian praise of folly in the face of someone who is cunning personified!

Jantine,

I really like that connection, and it is one I would have missed if you had not pointed it out. And fancy Barnaby's making this Erasmian praise of folly in the face of someone who is cunning personified!

Julie wrote: "That thing with John asking Hugh to hang his wig up on a pole was just bizarre. "

It was quite like a western movie thing, in a way. And maybe, it forebodes evil ...

It was quite like a western movie thing, in a way. And maybe, it forebodes evil ...

Kim wrote: "

Mr. Chester's interview with Miss Haredale

Chapter 29

Max Cowper

Text Ilustrated:

He raised his hat from his head, and yielding the path, suffered her to pass him. Then, as if the idea had bu..."

Kim

Thanks for the illustrations. This one gives us another cross-over of an illustrator who did both Dickens and Doyle. Cowper (1860-1911) feels more modern in this illustration. I’m always happy when you give us the evolution of the Dickens illustrators for we see the novel through differing illustrators’ eyes.

Mr. Chester's interview with Miss Haredale

Chapter 29

Max Cowper

Text Ilustrated:

He raised his hat from his head, and yielding the path, suffered her to pass him. Then, as if the idea had bu..."

Kim

Thanks for the illustrations. This one gives us another cross-over of an illustrator who did both Dickens and Doyle. Cowper (1860-1911) feels more modern in this illustration. I’m always happy when you give us the evolution of the Dickens illustrators for we see the novel through differing illustrators’ eyes.

Kim wrote: " Devonshire Terrace.

Twenty Third February.

My Dear Macready.

If I am to see anything of you in your coming holidays, I must be a Spartan now.

My labours press so heavily upon me at this time..."

What a great letter. The sentence “”With that cue for slow music and closing in with a picture, bring down the envelope” gives us a clear indication of how much Dickens thinks about, relies on, and incorporates the elements of the theatre in his writing. Both in his novels and this letter the theatre’s presence is clear. “Bring down the envelope” is so great. Not the curtain to end a letter but an envelope. Perfect.

Twenty Third February.

My Dear Macready.

If I am to see anything of you in your coming holidays, I must be a Spartan now.

My labours press so heavily upon me at this time..."

What a great letter. The sentence “”With that cue for slow music and closing in with a picture, bring down the envelope” gives us a clear indication of how much Dickens thinks about, relies on, and incorporates the elements of the theatre in his writing. Both in his novels and this letter the theatre’s presence is clear. “Bring down the envelope” is so great. Not the curtain to end a letter but an envelope. Perfect.

Tennant's illustration in message 24 makes Joe look quite young - 14 or so. I don't know if we were given his age, but I think of him being around 20. I notice that it's from an adaptation for children, so I suppose a younger looking Joe would have more appeal for that audience.

Tennant's illustration in message 24 makes Joe look quite young - 14 or so. I don't know if we were given his age, but I think of him being around 20. I notice that it's from an adaptation for children, so I suppose a younger looking Joe would have more appeal for that audience. Miggs and Sim look incredibly haughty in Phiz's illustration (message 19)! Did anyone else wonder while reading that scene, about Sim announcing Chester and then remaining there in the room through the whole of his visit? Would that have been appropriate? Same with Miggs, but Sim, especially, seems out of place in this setting.

PS I love that there's a toby jug on the mantel in the Phiz picture. This is the first book I can remember toby jugs/mugs being mentioned by Dickens. If I thought it was safe to put my Sam Weller toby in the dishwasher, I'd have a drink out of him right now. As it is, he'll have to remain a quirky objet d'art. :-)

PS I love that there's a toby jug on the mantel in the Phiz picture. This is the first book I can remember toby jugs/mugs being mentioned by Dickens. If I thought it was safe to put my Sam Weller toby in the dishwasher, I'd have a drink out of him right now. As it is, he'll have to remain a quirky objet d'art. :-)

Mary Lou wrote: "Miggs and Sim look incredibly haughty in Phiz's illustration (message 19)! Did anyone else wonder while reading that scene, about Sim announcing Chester and then remaining there in the room through the whole of his visit? Would that have been appropriate? Same with Miggs, but Sim, especially, seems out of place in this setting. "

Yes, it struck me as odd too. However, in that household everything seems to be topsy turvy anyway, with Miggs and Sim getting way too much freedom and power for people of their station in that period.

Yes, it struck me as odd too. However, in that household everything seems to be topsy turvy anyway, with Miggs and Sim getting way too much freedom and power for people of their station in that period.

Hello Curiosities

We are progressing deeper into the novel and some of you may be wondering where the Gordon Riots are. Well, hang on just a bit longer and they will be upon us. In the meantime, let’s see what is up with Varden and Haredale.

The chapter begins with Haredale asking his opinion of Mrs Rudge to which The locksmith replies that he would not presume to know anything about any woman. Given the character of Mrs Varden I can understand his reluctance. While we know that Mr Haredale is of a higher social class than Varden did you note that Haredale referred to Gabriel as “my good friend”? For all his flaws, I like Haredale much more than Chester. While Haredale does treat Emma rather dismissively at times, I feel his heart is in the right place. Haredale, like his home the Warren, represents the past. Varden tells Haredale about seeing Mrs Rudge with “the robber and cut-throat” and how Mrs Rudge prevented Varden from confronting the criminal. He then tells Haredale that since that time Mrs Rudge always gives him a look that distinctly says “[d]’ont ask me anything.” Haredale then wonders if they both might have always been deceived about the true nature of Mrs Rudge. Varden totally rejects this suggestion. We learn that Varden had courted Mrs Rudge before she married someone else.

Thoughts

In the opening paragraphs of this chapter we learn more about the relationship between Haredale and Varden. What new information did you find most interesting?

Why might Dickens be building the relationship between these two men?

Varden and Haredale get a huge surprise when they knock on Mrs Rudge’s door and Chester answers it. Chester is as slippery and verbally slimy as ever and tells the two visitors that Mrs Rudge is no longer at the house. Chester gleefully tells Haredale that he has “bought off” Ned and Emma’s go-betweens by explaining that most people will do anything for money. Chester won’t tell Haredale any more information. As we progress through the novel this scene may be replayed many times. What is it that motivates an individual? Is it money above all else? Or political desire? Or loyalty to one’s friends and family? Or to be one of a crowd? Perhaps other factors or a combination of several? I think it will be important to see what it is that makes them act as they do.

The chapter ends with Chester presenting the key of the house to Haredale who it turns out is the owner of the tenement. Do you notice how the spider web of interconnecting events, people, and even properties is being continually spun larger by Dickens? I am always intrigued by how Dickens manages to create such intricate connections within his novels. Sometimes such connections and coincidences do test my patience, but most of the time I happy accept and enjoy his intriguing style.

Thoughts

Chester seems to appear at will in the narrative and it is never a pleasant occurrence. His manner of speech continues to be laconic, ironic, and sarcastic. This chapter gives the reader yet another opportunity to see Chester and Haredale together. So far, it seems that Chester is always one step ahead of Haredale. What purpose might Dickens have for repeatedly presenting these characters to the reader?