The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Barnaby Rudge

Barnaby Rudge

>

BR Chapters 51-55

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

We begin Chapter 52 at the Boot with the rioters, those who haven't gone back to their own homes or don't have homes to go back to. At the Boot we still find Dennis, Hugh, and Barnaby but not many others, we're told there were only about a dozen people there, some slept in the stable and outhouses, some in the common room, some two or three in beds. Dennis and Hugh lay in the straw watching Barnaby who they both agree when it comes to the riots, he is worth a dozen other men. Dennis says his only complaint about him is that Barnaby is too clean:

And his cleanliness too!’ said Mr Dennis, who certainly had no reason to entertain a fellow feeling with anybody who was particular on that score; ‘what weaknesses he’s guilty of; with respect to his cleanliness! At five o’clock this morning, there he was at the pump, though any one would think he had gone through enough, the day before yesterday, to be pretty fast asleep at that time. But no—when I woke for a minute or two, there he was at the pump, and if you’d seen him sticking them peacock’s feathers into his hat when he’d done washing—ah! I’m sorry he’s such a imperfect character, but the best on us is incomplete in some pint of view or another.’

As they talk about him, Barnaby is outside the door leaning on the flagstaff, pacing slowly up and down, very erect and showing what great importance he put on this job they had given him and how happy and how proud it made him. Hugh has given him this job so the others can discuss the rioting without Barnaby hearing. Simon Tappertit returns, thoroughly drunk as usual and the three plan for that night's raids. Soon they rejoin the rioting taking Barnaby with them. They first vandalize the homes of Catholics, braking open the doors and windows; and removing and burning all the furnishings leaving only bare walls. They searched for tools of destruction, such as hammers, axes, saws and the like. Finding them, they wore them in belts of cord or handkerchiefs without the least concealment. Moving to the chapels they tore down and took away the altars, benches, pulpits, relics, and statues of Catholic churches, burning all in great fires that shed a glare on the whole country while they danced and roared around the fires. Gashford is not impressed and we end with this:

As the main body filed off from this scene of action, and passed down Welbeck Street, they came upon Gashford, who had been a witness of their proceedings, and was walking stealthily along the pavement. Keeping up with him, and yet not seeming to speak, Hugh muttered in his ear:

‘Is this better, master?’

‘No,’ said Gashford. ‘It is not.’

‘What would you have?’ said Hugh. ‘Fevers are never at their height at once. They must get on by degrees.’

‘I would have you,’ said Gashford, pinching his arm with such malevolence that his nails seemed to meet in the skin; ‘I would have you put some meaning into your work. Fools! Can you make no better bonfires than of rags and scraps? Can you burn nothing whole?’

‘A little patience, master,’ said Hugh. ‘Wait but a few hours, and you shall see. Look for a redness in the sky, to-morrow night.’

With that, he fell back into his place beside Barnaby; and when the secretary looked after him, both were lost in the crowd.

And his cleanliness too!’ said Mr Dennis, who certainly had no reason to entertain a fellow feeling with anybody who was particular on that score; ‘what weaknesses he’s guilty of; with respect to his cleanliness! At five o’clock this morning, there he was at the pump, though any one would think he had gone through enough, the day before yesterday, to be pretty fast asleep at that time. But no—when I woke for a minute or two, there he was at the pump, and if you’d seen him sticking them peacock’s feathers into his hat when he’d done washing—ah! I’m sorry he’s such a imperfect character, but the best on us is incomplete in some pint of view or another.’

As they talk about him, Barnaby is outside the door leaning on the flagstaff, pacing slowly up and down, very erect and showing what great importance he put on this job they had given him and how happy and how proud it made him. Hugh has given him this job so the others can discuss the rioting without Barnaby hearing. Simon Tappertit returns, thoroughly drunk as usual and the three plan for that night's raids. Soon they rejoin the rioting taking Barnaby with them. They first vandalize the homes of Catholics, braking open the doors and windows; and removing and burning all the furnishings leaving only bare walls. They searched for tools of destruction, such as hammers, axes, saws and the like. Finding them, they wore them in belts of cord or handkerchiefs without the least concealment. Moving to the chapels they tore down and took away the altars, benches, pulpits, relics, and statues of Catholic churches, burning all in great fires that shed a glare on the whole country while they danced and roared around the fires. Gashford is not impressed and we end with this:

As the main body filed off from this scene of action, and passed down Welbeck Street, they came upon Gashford, who had been a witness of their proceedings, and was walking stealthily along the pavement. Keeping up with him, and yet not seeming to speak, Hugh muttered in his ear:

‘Is this better, master?’

‘No,’ said Gashford. ‘It is not.’

‘What would you have?’ said Hugh. ‘Fevers are never at their height at once. They must get on by degrees.’

‘I would have you,’ said Gashford, pinching his arm with such malevolence that his nails seemed to meet in the skin; ‘I would have you put some meaning into your work. Fools! Can you make no better bonfires than of rags and scraps? Can you burn nothing whole?’

‘A little patience, master,’ said Hugh. ‘Wait but a few hours, and you shall see. Look for a redness in the sky, to-morrow night.’

With that, he fell back into his place beside Barnaby; and when the secretary looked after him, both were lost in the crowd.

In Chapter 53 it is the next day is the King’s birthday, just in case you're interested, and King's birthday or not, our riot leader's are still together and think only of getting the rest of the followers so deeply involved that no hope of a pardon or no offer of a reward might tempt them to betray the others. But they didn't need to worry because the others having a sense of having gone too far to be forgiven hold together anyway.

Many who would readily have pointed out the foremost rioters and given evidence against them, felt that escape by that means was hopeless, when their every act had been observed by scores of people who had taken no part in the disturbances; who had suffered in their persons, peace, or property, by the outrages of the mob; who would be most willing witnesses; and whom the government would, no doubt, prefer to any King’s evidence that might be offered. Many of this class had deserted their usual occupations on the Saturday morning; some had been seen by their employers active in the tumult; others knew they must be suspected, and that they would be discharged if they returned; others had been desperate from the beginning, and comforted themselves with the homely proverb, that, being hanged at all, they might as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb. They all hoped and believed, in a greater or less degree, that the government they seemed to have paralysed, would, in its terror, come to terms with them in the end, and suffer them to make their own conditions. The least sanguine among them reasoned with himself that, at the worst, they were too many to be all punished, and that he had as good a chance of escape as any other man.

And the ones who didn't fall into the first two groups - we're told they never reasoned or thought at all, but were stimulated by their own passions, either poverty, ignorance, love of mischief, or hope of plunder. One thing that struck me in this chapter was how much Barnaby cared for Hugh:

‘I hear him coming,’ he answered: ‘Hark! Do you mark that? That’s his foot! Bless you, I know his step, and his dog’s too. Tramp, tramp, pit-pat, on they come together, and, ha ha ha!—and here they are!’ he cried, joyfully welcoming Hugh with both hands, and then patting him fondly on the back, as if instead of being the rough companion he was, he had been one of the most prepossessing of men. ‘Here he is, and safe too! I am glad to see him back again, old Hugh!’

I was wondering why and when Barnaby got so close to Hugh. When Hugh worked at the Maypole he never seemed to pay any attention to Barnaby. He never seemed to pay any attention to anyone most of the time, then Barnaby and his mother left the area for five years during this time he never saw or heard of Hugh, so why is he so fond of him now? Whatever the reason, his love for Hugh seems like it may be making a difference in Hugh:

‘I’m a Turk if he don’t give me a warmer welcome always than any man of sense,’ said Hugh, shaking hands with him with a kind of ferocious friendship, strange enough to see. ‘How are you, boy?’

If Hugh spends enough time with Barnaby, who knows what may happen. Perhaps we'll see a new Hugh. But now Gashford comes to discuss the riots with them, when Hugh comes in Gashford says he knows Hugh has been to see his friend and asks Hugh if he should say his name, Hugh answers no. I'm assuming the "friend" is Sir Chester, but if it is I don't know why Hugh was there and I don't know why Gashford would know that or why he would care. I don't know why Gashford cares about any of this, what is he getting out of the whole thing?

Nevertheless, Gashford now informs them that the King in Council has offered a five-hundred-pound reward for information about anyone who has been involved in the destruction of the Catholic chapels. He tells them there are witnesses against them, one of them being Mr. Haredale, when Barnaby hears the name he looks in, but Hugh tells him to guard, and Barnaby goes off again with his flag. Hugh tells Gashford he could have ruined the whole thing, and Gashford answered he didn't know Barnaby would be so quick. I see no reason for Gashford to hate Mr. Haredale as much as he does, and I really don't see a reason for Hugh to hate him so much, as far as I can remember it was only one time Hugh could have been insulted by something Mr. Haredale had done. Wouldn't it make more sense for him to hate John Willet who treated him as an "animal" for years? Soon they go out to commence rioting once again. Gashford follows them, but he goes to Lord George’s house and watches the proceedings from the window, but not being satisfied with the view, he climbs to the rooftop. Here he waits to see the redness in the sky Hugh had promised him, but there was nothing when the chapter comes to an end.

Many who would readily have pointed out the foremost rioters and given evidence against them, felt that escape by that means was hopeless, when their every act had been observed by scores of people who had taken no part in the disturbances; who had suffered in their persons, peace, or property, by the outrages of the mob; who would be most willing witnesses; and whom the government would, no doubt, prefer to any King’s evidence that might be offered. Many of this class had deserted their usual occupations on the Saturday morning; some had been seen by their employers active in the tumult; others knew they must be suspected, and that they would be discharged if they returned; others had been desperate from the beginning, and comforted themselves with the homely proverb, that, being hanged at all, they might as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb. They all hoped and believed, in a greater or less degree, that the government they seemed to have paralysed, would, in its terror, come to terms with them in the end, and suffer them to make their own conditions. The least sanguine among them reasoned with himself that, at the worst, they were too many to be all punished, and that he had as good a chance of escape as any other man.

And the ones who didn't fall into the first two groups - we're told they never reasoned or thought at all, but were stimulated by their own passions, either poverty, ignorance, love of mischief, or hope of plunder. One thing that struck me in this chapter was how much Barnaby cared for Hugh:

‘I hear him coming,’ he answered: ‘Hark! Do you mark that? That’s his foot! Bless you, I know his step, and his dog’s too. Tramp, tramp, pit-pat, on they come together, and, ha ha ha!—and here they are!’ he cried, joyfully welcoming Hugh with both hands, and then patting him fondly on the back, as if instead of being the rough companion he was, he had been one of the most prepossessing of men. ‘Here he is, and safe too! I am glad to see him back again, old Hugh!’

I was wondering why and when Barnaby got so close to Hugh. When Hugh worked at the Maypole he never seemed to pay any attention to Barnaby. He never seemed to pay any attention to anyone most of the time, then Barnaby and his mother left the area for five years during this time he never saw or heard of Hugh, so why is he so fond of him now? Whatever the reason, his love for Hugh seems like it may be making a difference in Hugh:

‘I’m a Turk if he don’t give me a warmer welcome always than any man of sense,’ said Hugh, shaking hands with him with a kind of ferocious friendship, strange enough to see. ‘How are you, boy?’

If Hugh spends enough time with Barnaby, who knows what may happen. Perhaps we'll see a new Hugh. But now Gashford comes to discuss the riots with them, when Hugh comes in Gashford says he knows Hugh has been to see his friend and asks Hugh if he should say his name, Hugh answers no. I'm assuming the "friend" is Sir Chester, but if it is I don't know why Hugh was there and I don't know why Gashford would know that or why he would care. I don't know why Gashford cares about any of this, what is he getting out of the whole thing?

Nevertheless, Gashford now informs them that the King in Council has offered a five-hundred-pound reward for information about anyone who has been involved in the destruction of the Catholic chapels. He tells them there are witnesses against them, one of them being Mr. Haredale, when Barnaby hears the name he looks in, but Hugh tells him to guard, and Barnaby goes off again with his flag. Hugh tells Gashford he could have ruined the whole thing, and Gashford answered he didn't know Barnaby would be so quick. I see no reason for Gashford to hate Mr. Haredale as much as he does, and I really don't see a reason for Hugh to hate him so much, as far as I can remember it was only one time Hugh could have been insulted by something Mr. Haredale had done. Wouldn't it make more sense for him to hate John Willet who treated him as an "animal" for years? Soon they go out to commence rioting once again. Gashford follows them, but he goes to Lord George’s house and watches the proceedings from the window, but not being satisfied with the view, he climbs to the rooftop. Here he waits to see the redness in the sky Hugh had promised him, but there was nothing when the chapter comes to an end.

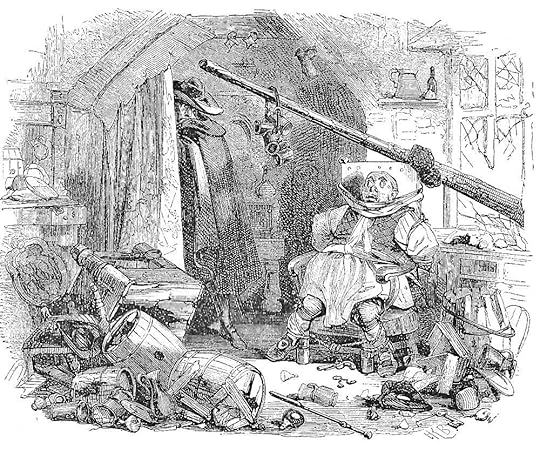

In Chapter 54 we find John Willet, disgusted with Parkes, Daisy, and Cobb, who plan to go to London to see the riots for themselves. We're told that rumors of the disturbances had begun to be generally circulated through the towns and villages, but the stories seemed so monstrous and improbable a great number of people living at a distance didn't believe it. John Willet was one of those he refuses to go with them and remains at home telling them the King would never allow these things to happen. After they leave, John sees a mass of people marching toward the Maypole. It is the No-Popery crowd, led by Hugh:

‘Halloa!’ cried a voice he knew, as the man who spoke came cleaving through the throng. ‘Where is he? Give him to me. Don’t hurt him. How now, old Jack! Ha ha ha!’

Mr Willet looked at him, and saw it was Hugh; but he said nothing, and thought nothing.

‘These lads are thirsty and must drink!’ cried Hugh, thrusting him back towards the house. ‘Bustle, Jack, bustle. Show us the best—the very best—the over-proof that you keep for your own drinking, Jack!’

John faintly articulated the words, ‘Who’s to pay?’

‘He says “Who’s to pay?”’ cried Hugh, with a roar of laughter which was loudly echoed by the crowd. Then turning to John, he added, ‘Pay! Why, nobody.’

John stared round at the mass of faces—some grinning, some fierce, some lighted up by torches, some indistinct, some dusky and shadowy: some looking at him, some at his house, some at each other—and while he was, as he thought, in the very act of doing so, found himself, without any consciousness of having moved, in the bar; sitting down in an arm-chair, and watching the destruction of his property, as if it were some queer play or entertainment, of an astonishing and stupefying nature, but having no reference to himself—that he could make out—at all.

Yes. Here was the bar—the bar that the boldest never entered without special invitation—the sanctuary, the mystery, the hallowed ground: here it was, crammed with men, clubs, sticks, torches, pistols; filled with a deafening noise, oaths, shouts, screams, hootings; changed all at once into a bear-garden, a madhouse, an infernal temple: men darting in and out, by door and window, smashing the glass, turning the taps, drinking liquor out of China punchbowls, sitting astride of casks, smoking private and personal pipes, cutting down the sacred grove of lemons, hacking and hewing at the celebrated cheese, breaking open inviolable drawers, putting things in their pockets which didn’t belong to them, dividing his own money before his own eyes, wantonly wasting, breaking, pulling down and tearing up: nothing quiet, nothing private: men everywhere—above, below, overhead, in the bedrooms, in the kitchen, in the yard, in the stables—clambering in at windows when there were doors wide open; dropping out of windows when the stairs were handy; leaping over the bannisters into chasms of passages: new faces and figures presenting themselves every instant—some yelling, some singing, some fighting, some breaking glass and crockery, some laying the dust with the liquor they couldn’t drink, some ringing the bells till they pulled them down, others beating them with pokers till they beat them into fragments: more men still—more, more, more—swarming on like insects: noise, smoke, light, darkness, frolic, anger, laughter, groans, plunder, fear, and ruin!

After they loot the Maypole of its liquor and they tie John Willet up, though Dennis would like to hang him and is disappointed Hugh won't allow him to do It seems that through all this, Hugh protected John Willet, while allowing the Maypole to be destroyed, he didn't allow anyone to hurt him. I wonder if he would protect Haredale if he found him at the Warren, I somehow doubt it. I'm not sure though, is Hugh really so bad that he would allow someone to be murdered? Someone who had done nothing to deserve it. So far he's been awful, but not that awful. What would he have done to Dolly when he found her alone earlier in the book, if Joe hadn't come along? I can't decide how I feel about Hugh, so I'll follow him because now they are done with the Maypole and march off toward the Warren, where Emma and Dolly are still living, though Mr. Haredale is absent. I wonder what Hugh will do when once again he has Dolly there alone with him, or she may as well be for there is no one to protect her. I guess we'll find out.

‘Halloa!’ cried a voice he knew, as the man who spoke came cleaving through the throng. ‘Where is he? Give him to me. Don’t hurt him. How now, old Jack! Ha ha ha!’

Mr Willet looked at him, and saw it was Hugh; but he said nothing, and thought nothing.

‘These lads are thirsty and must drink!’ cried Hugh, thrusting him back towards the house. ‘Bustle, Jack, bustle. Show us the best—the very best—the over-proof that you keep for your own drinking, Jack!’

John faintly articulated the words, ‘Who’s to pay?’

‘He says “Who’s to pay?”’ cried Hugh, with a roar of laughter which was loudly echoed by the crowd. Then turning to John, he added, ‘Pay! Why, nobody.’

John stared round at the mass of faces—some grinning, some fierce, some lighted up by torches, some indistinct, some dusky and shadowy: some looking at him, some at his house, some at each other—and while he was, as he thought, in the very act of doing so, found himself, without any consciousness of having moved, in the bar; sitting down in an arm-chair, and watching the destruction of his property, as if it were some queer play or entertainment, of an astonishing and stupefying nature, but having no reference to himself—that he could make out—at all.

Yes. Here was the bar—the bar that the boldest never entered without special invitation—the sanctuary, the mystery, the hallowed ground: here it was, crammed with men, clubs, sticks, torches, pistols; filled with a deafening noise, oaths, shouts, screams, hootings; changed all at once into a bear-garden, a madhouse, an infernal temple: men darting in and out, by door and window, smashing the glass, turning the taps, drinking liquor out of China punchbowls, sitting astride of casks, smoking private and personal pipes, cutting down the sacred grove of lemons, hacking and hewing at the celebrated cheese, breaking open inviolable drawers, putting things in their pockets which didn’t belong to them, dividing his own money before his own eyes, wantonly wasting, breaking, pulling down and tearing up: nothing quiet, nothing private: men everywhere—above, below, overhead, in the bedrooms, in the kitchen, in the yard, in the stables—clambering in at windows when there were doors wide open; dropping out of windows when the stairs were handy; leaping over the bannisters into chasms of passages: new faces and figures presenting themselves every instant—some yelling, some singing, some fighting, some breaking glass and crockery, some laying the dust with the liquor they couldn’t drink, some ringing the bells till they pulled them down, others beating them with pokers till they beat them into fragments: more men still—more, more, more—swarming on like insects: noise, smoke, light, darkness, frolic, anger, laughter, groans, plunder, fear, and ruin!

After they loot the Maypole of its liquor and they tie John Willet up, though Dennis would like to hang him and is disappointed Hugh won't allow him to do It seems that through all this, Hugh protected John Willet, while allowing the Maypole to be destroyed, he didn't allow anyone to hurt him. I wonder if he would protect Haredale if he found him at the Warren, I somehow doubt it. I'm not sure though, is Hugh really so bad that he would allow someone to be murdered? Someone who had done nothing to deserve it. So far he's been awful, but not that awful. What would he have done to Dolly when he found her alone earlier in the book, if Joe hadn't come along? I can't decide how I feel about Hugh, so I'll follow him because now they are done with the Maypole and march off toward the Warren, where Emma and Dolly are still living, though Mr. Haredale is absent. I wonder what Hugh will do when once again he has Dolly there alone with him, or she may as well be for there is no one to protect her. I guess we'll find out.

I just got back from walking Willow and it was an awful walk. We were so very hot, it is 90 degrees or so out there and I'm surprised we made it back without burning to cinders. So I came in, got both of us water, put in a Christmas DVD that shows a fireplace with a fire burning while playing Christmas music, and here I sit ready to take on this final chapter for this week. If only I had some hot chocolate it would be perfect. In Chapter 55 we find poor John Willet remains tied to a chair in the Maypole:

John Willet, left alone in his dismantled bar, continued to sit staring about him; awake as to his eyes, certainly, but with all his powers of reason and reflection in a sound and dreamless sleep. He looked round upon the room which had been for years, and was within an hour ago, the pride of his heart; and not a muscle of his face was moved. The night, without, looked black and cold through the dreary gaps in the casement; the precious liquids, now nearly leaked away, dripped with a hollow sound upon the floor; the Maypole peered ruefully in through the broken window, like the bowsprit of a wrecked ship; the ground might have been the bottom of the sea, it was so strewn with precious fragments. Currents of air rushed in, as the old doors jarred and creaked upon their hinges; the candles flickered and guttered down, and made long winding-sheets; the cheery deep-red curtains flapped and fluttered idly in the wind; even the stout Dutch kegs, overthrown and lying empty in dark corners, seemed the mere husks of good fellows whose jollity had departed, and who could kindle with a friendly glow no more. John saw this desolation, and yet saw it not. He was perfectly contented to sit there, staring at it, and felt no more indignation or discomfort in his bonds than if they had been robes of honour. So far as he was personally concerned, old Time lay snoring, and the world stood still.

I now feel sorry for John Willet, I never liked him, but now I feel sorry for him. His whole world has come crashing down around him, and who knows where Joe is, so now John Willet is really all alone, that's how it seems to me anyway, the thing he was proudest of in the world is in ruins. But, he is briefly joined by someone else, a man passes the window and climbs in. The man has a pale, worn, withered face; with eyes unnaturally large and bright, and is wearing a large, dark cloak, and a slouched hat. He looks at John and asks if he is alone, and how long he had been sitting tied up, but John doesn't seem to be able to answer either question being still in shock over what has happen. The stranger then asks where the others have gone; and John nods toward the direction opposite of the Warren, but the stranger knows better and becomes angry until he realizes that John doesn't seem to be aware of what he did. He eats and drinks from the scraps left by the looters before going out again into the night. So at this point I was wondering who this man was. I thought of Mr. Haredale because I could see him having a pale, worn, face because he would be worried about his niece and his home, and I could see him only caring where the rioters have gone and not what has happened at the Maypole. But this didn't last long because I couldn't imagine Mr. Haredale eating and drinking the food laying around and letting Mr. Willet tied up. Whoever it is for some reason he doesn't bother to leave the servants out or untie Mr. Willet before leaving and I was hoping he plans on coming back because who knows how long they will be there until another person comes along to untie them. But now a bell begins ringing and a strang thing happens:

The man was hurrying to the door, when suddenly there came towards them on the wind, the loud and rapid tolling of an alarm-bell, and then a bright and vivid glare streamed up, which illumined, not only the whole chamber, but all the country.

It was not the sudden change from darkness to this dreadful light, it was not the sound of distant shrieks and shouts of triumph, it was not this dread invasion of the serenity and peace of night, that drove the man back as though a thunderbolt had struck him. It was the Bell. If the ghastliest shape the human mind has ever pictured in its wildest dreams had risen up before him, he could not have staggered backward from its touch, as he did from the first sound of that loud iron voice. With eyes that started from his head, his limbs convulsed, his face most horrible to see, he raised one arm high up into the air, and holding something visionary back and down, with his other hand, drove at it as though he held a knife and stabbed it to the heart. He clutched his hair, and stopped his ears, and travelled madly round and round; then gave a frightful cry, and with it rushed away: still, still, the Bell tolled on and seemed to follow him—louder and louder, hotter and hotter yet. The glare grew brighter, the roar of voices deeper; the crash of heavy bodies falling, shook the air; bright streams of sparks rose up into the sky; but louder than them all—rising faster far, to Heaven—a million times more fierce and furious—pouring forth dreadful secrets after its long silence—speaking the language of the dead—the Bell—the Bell!

What hunt of spectres could surpass that dread pursuit and flight! Had there been a legion of them on his track, he could have better borne it. They would have had a beginning and an end, but here all space was full. The one pursuing voice was everywhere: it sounded in the earth, the air; shook the long grass, and howled among the trembling trees. The echoes caught it up, the owls hooted as it flew upon the breeze, the nightingale was silent and hid herself among the thickest boughs: it seemed to goad and urge the angry fire, and lash it into madness; everything was steeped in one prevailing red; the glow was everywhere; nature was drenched in blood: still the remorseless crying of that awful voice—the Bell, the Bell!

It ceased; but not in his ears. The knell was at his heart. No work of man had ever voice like that which sounded there, and warned him that it cried unceasingly to Heaven. Who could hear that bell, and not know what it said! There was murder in its every note—cruel, relentless, savage murder—the murder of a confiding man, by one who held his every trust. Its ringing summoned phantoms from their graves. What face was that, in which a friendly smile changed to a look of half incredulous horror, which stiffened for a moment into one of pain, then changed again into an imploring glance at Heaven, and so fell idly down with upturned eyes, like the dead stags’ he had often peeped at when a little child: shrinking and shuddering—there was a dreadful thing to think of now!—and clinging to an apron as he looked! He sank upon the ground, and grovelling down as if he would dig himself a place to hide in, covered his face and ears: but no, no, no,—a hundred walls and roofs of brass would not shut out that bell, for in it spoke the wrathful voice of God, and from that voice, the whole wide universe could not afford a refuge!

When I read that I finally knew. I knew who the man was, I knew who the mysterious stranger was, I knew why Mrs. Rudge either gave him money or ran away from him. I knew why Mr. Haredale spends his time sitting in an empty house waiting for who knows what and why Solomon Daisy saw a ghost. We'll all know if I'm right in the next chapter I think. But for now we follow the stranger and the rioters to the Warren where the mob is in the process of destroying everything. A few servants attempt to hold them off, but they are no match for the mob and soon the house is filled with the rioters. Now in possession of the house, they spread themselves out and destroy everything, some starting bonfires, others breaking up the furniture and casting it into the fires below, smashing all the windows, breaking up the floors and rafters, throwing all they could find on the blaze. But what about this bell, who is ringing it? This is what we're told:

And who were they? The alarm-bell rang—and it was pulled by no faint or hesitating hands—for a long time; but not a soul was seen. Some of the insurgents said that when it ceased, they heard the shrieks of women, and saw some garments fluttering in the air, as a party of men bore away no unresisting burdens. No one could say that this was true or false, in such an uproar; but where was Hugh? Who among them had seen him, since the forcing of the doors? The cry spread through the body. Where was Hugh!

Well, who were they, and where are they? That's another thing we'll learn in the next chapter, I'll see you there. But before I go, I'll tell you that I had great fun doing this, it had been so long I forgot how fun it could be. Tristram should go on holiday more often. Just not too often. :-)

John Willet, left alone in his dismantled bar, continued to sit staring about him; awake as to his eyes, certainly, but with all his powers of reason and reflection in a sound and dreamless sleep. He looked round upon the room which had been for years, and was within an hour ago, the pride of his heart; and not a muscle of his face was moved. The night, without, looked black and cold through the dreary gaps in the casement; the precious liquids, now nearly leaked away, dripped with a hollow sound upon the floor; the Maypole peered ruefully in through the broken window, like the bowsprit of a wrecked ship; the ground might have been the bottom of the sea, it was so strewn with precious fragments. Currents of air rushed in, as the old doors jarred and creaked upon their hinges; the candles flickered and guttered down, and made long winding-sheets; the cheery deep-red curtains flapped and fluttered idly in the wind; even the stout Dutch kegs, overthrown and lying empty in dark corners, seemed the mere husks of good fellows whose jollity had departed, and who could kindle with a friendly glow no more. John saw this desolation, and yet saw it not. He was perfectly contented to sit there, staring at it, and felt no more indignation or discomfort in his bonds than if they had been robes of honour. So far as he was personally concerned, old Time lay snoring, and the world stood still.

I now feel sorry for John Willet, I never liked him, but now I feel sorry for him. His whole world has come crashing down around him, and who knows where Joe is, so now John Willet is really all alone, that's how it seems to me anyway, the thing he was proudest of in the world is in ruins. But, he is briefly joined by someone else, a man passes the window and climbs in. The man has a pale, worn, withered face; with eyes unnaturally large and bright, and is wearing a large, dark cloak, and a slouched hat. He looks at John and asks if he is alone, and how long he had been sitting tied up, but John doesn't seem to be able to answer either question being still in shock over what has happen. The stranger then asks where the others have gone; and John nods toward the direction opposite of the Warren, but the stranger knows better and becomes angry until he realizes that John doesn't seem to be aware of what he did. He eats and drinks from the scraps left by the looters before going out again into the night. So at this point I was wondering who this man was. I thought of Mr. Haredale because I could see him having a pale, worn, face because he would be worried about his niece and his home, and I could see him only caring where the rioters have gone and not what has happened at the Maypole. But this didn't last long because I couldn't imagine Mr. Haredale eating and drinking the food laying around and letting Mr. Willet tied up. Whoever it is for some reason he doesn't bother to leave the servants out or untie Mr. Willet before leaving and I was hoping he plans on coming back because who knows how long they will be there until another person comes along to untie them. But now a bell begins ringing and a strang thing happens:

The man was hurrying to the door, when suddenly there came towards them on the wind, the loud and rapid tolling of an alarm-bell, and then a bright and vivid glare streamed up, which illumined, not only the whole chamber, but all the country.

It was not the sudden change from darkness to this dreadful light, it was not the sound of distant shrieks and shouts of triumph, it was not this dread invasion of the serenity and peace of night, that drove the man back as though a thunderbolt had struck him. It was the Bell. If the ghastliest shape the human mind has ever pictured in its wildest dreams had risen up before him, he could not have staggered backward from its touch, as he did from the first sound of that loud iron voice. With eyes that started from his head, his limbs convulsed, his face most horrible to see, he raised one arm high up into the air, and holding something visionary back and down, with his other hand, drove at it as though he held a knife and stabbed it to the heart. He clutched his hair, and stopped his ears, and travelled madly round and round; then gave a frightful cry, and with it rushed away: still, still, the Bell tolled on and seemed to follow him—louder and louder, hotter and hotter yet. The glare grew brighter, the roar of voices deeper; the crash of heavy bodies falling, shook the air; bright streams of sparks rose up into the sky; but louder than them all—rising faster far, to Heaven—a million times more fierce and furious—pouring forth dreadful secrets after its long silence—speaking the language of the dead—the Bell—the Bell!

What hunt of spectres could surpass that dread pursuit and flight! Had there been a legion of them on his track, he could have better borne it. They would have had a beginning and an end, but here all space was full. The one pursuing voice was everywhere: it sounded in the earth, the air; shook the long grass, and howled among the trembling trees. The echoes caught it up, the owls hooted as it flew upon the breeze, the nightingale was silent and hid herself among the thickest boughs: it seemed to goad and urge the angry fire, and lash it into madness; everything was steeped in one prevailing red; the glow was everywhere; nature was drenched in blood: still the remorseless crying of that awful voice—the Bell, the Bell!

It ceased; but not in his ears. The knell was at his heart. No work of man had ever voice like that which sounded there, and warned him that it cried unceasingly to Heaven. Who could hear that bell, and not know what it said! There was murder in its every note—cruel, relentless, savage murder—the murder of a confiding man, by one who held his every trust. Its ringing summoned phantoms from their graves. What face was that, in which a friendly smile changed to a look of half incredulous horror, which stiffened for a moment into one of pain, then changed again into an imploring glance at Heaven, and so fell idly down with upturned eyes, like the dead stags’ he had often peeped at when a little child: shrinking and shuddering—there was a dreadful thing to think of now!—and clinging to an apron as he looked! He sank upon the ground, and grovelling down as if he would dig himself a place to hide in, covered his face and ears: but no, no, no,—a hundred walls and roofs of brass would not shut out that bell, for in it spoke the wrathful voice of God, and from that voice, the whole wide universe could not afford a refuge!

When I read that I finally knew. I knew who the man was, I knew who the mysterious stranger was, I knew why Mrs. Rudge either gave him money or ran away from him. I knew why Mr. Haredale spends his time sitting in an empty house waiting for who knows what and why Solomon Daisy saw a ghost. We'll all know if I'm right in the next chapter I think. But for now we follow the stranger and the rioters to the Warren where the mob is in the process of destroying everything. A few servants attempt to hold them off, but they are no match for the mob and soon the house is filled with the rioters. Now in possession of the house, they spread themselves out and destroy everything, some starting bonfires, others breaking up the furniture and casting it into the fires below, smashing all the windows, breaking up the floors and rafters, throwing all they could find on the blaze. But what about this bell, who is ringing it? This is what we're told:

And who were they? The alarm-bell rang—and it was pulled by no faint or hesitating hands—for a long time; but not a soul was seen. Some of the insurgents said that when it ceased, they heard the shrieks of women, and saw some garments fluttering in the air, as a party of men bore away no unresisting burdens. No one could say that this was true or false, in such an uproar; but where was Hugh? Who among them had seen him, since the forcing of the doors? The cry spread through the body. Where was Hugh!

Well, who were they, and where are they? That's another thing we'll learn in the next chapter, I'll see you there. But before I go, I'll tell you that I had great fun doing this, it had been so long I forgot how fun it could be. Tristram should go on holiday more often. Just not too often. :-)

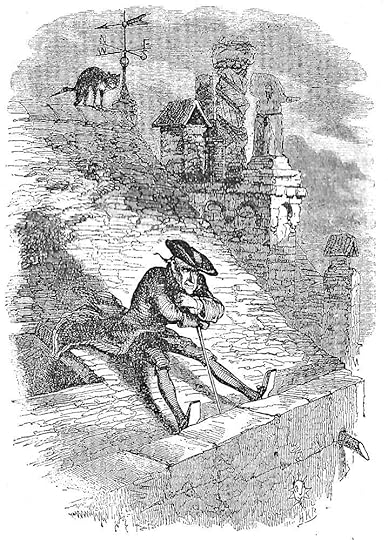

Kim wrote: "In Chapter 53 ... Soon they go out to commence rioting once again. Gashford follows them, but he goes to Lord George’s house and watches the proceedings from the window..."

Kim wrote: "In Chapter 53 ... Soon they go out to commence rioting once again. Gashford follows them, but he goes to Lord George’s house and watches the proceedings from the window..."As the rioters are passing Gashford at the window it says this:

Hugh merely raised his hat upon the bludgeon he carried, and glancing at a spectator on the opposite side of the way, was gone.

This reminded me of the scene in which Chester visited the Maypole, and Willet had Hugh toss his wig onto the weather vane, then climb up to retrieve it. Now here we have Hugh raise his hat up on top of his bludgeon, and who is it he looks to across the street? Mr. Chester. Coincidence? I don't know. But Dickens seems to give it some significance, so I thought it was worth mentioning.

Tangled webs!

Addendum: Do you think this is Hugh's way of signaling to Chester that the crowd is heading towards the Maypole? And if so, what strings is Chester pulling on his marionette, Hugh?

Kim wrote: "I had great fun doing this, it had been so long I forgot how fun it could be. Tristram should go on holiday more often. Just not too often. :-) ..."

Kim wrote: "I had great fun doing this, it had been so long I forgot how fun it could be. Tristram should go on holiday more often. Just not too often. :-) ..."And I had great fun reading your unique commentary! Like the boy in the fable, you have a way of pointing out that the emperor is strutting through the streets naked that makes me chuckle. (Why were the Vardens waiting up for Sim??). I miss Tristram, but enjoy getting your perspective. Thanks for filling in. :-)

On the section as a whole, what a mess. I'm appalled at the depths that humans can go to hurt one another, and it makes me angry. Varden's brave stance in chapter 51 is admirable (even if his charity towards Sim is misguided). But when we read about the debauchery at the Maypole and then the absolute barbarism at the Warren, we realize how truly brave Varden is.

On the section as a whole, what a mess. I'm appalled at the depths that humans can go to hurt one another, and it makes me angry. Varden's brave stance in chapter 51 is admirable (even if his charity towards Sim is misguided). But when we read about the debauchery at the Maypole and then the absolute barbarism at the Warren, we realize how truly brave Varden is. One wonders about the other divisions of the anti-Catholic protesters. Are they peaceful protesters who are carrying signs and doing sit-ins at Parliament, or are they, too, wreaking havoc in and around London? Is it just Hugh and his faction that are out of control and causing murder and mayhem?

What a way to end the week's reading:

Nothing left but a dull and dreary blank - a smouldering heap of dust and ashes - the silence and solitude of utter desolation.

Just kill me now.

Thank God this isn't the end of the book! I have high hopes that most of our acquaintances will reach a promised land once we walk through this barren wilderness.

SO MANY LOOSE THREADS!

SO MANY LOOSE THREADS!~ Where is Joe?

~ Where are Dolly and Emma?

~ Who is targeting Mrs. Rudge? And is that mysterious person the same as Soloman's ghost? And the man who left Willet tied up in the Maypole? Or have we several mystery men?

~ Will Barnaby, Dennis, Hugh, or Sim hang for their actions during the riots? (Okay - for Dennis there would be a certain satisfying karma.)

~ Where is Ned? Will he make his own way, and marry Emma?

~ What's the history of Chester, Haredale, and Gashford?

~ Grueby ... what's his deal?

~ Who IS Hugh, and what's brought him to this point?

I must say, I'm on the edge of my seat, and find this story mentally exhausting, but in a good way. I don't think I've ever read 500+ pages into a book, and still had no idea who the protagonist is. It must be Gabriel -- he's the most winsome character in the book, but he's certainly not the typical heroic central character, is he?

Kim wrote: "In Chapter 53 it is the next day is the King’s birthday, just in case you're interested, and King's birthday or not, our riot leader's are still together and think only of getting the rest of the f..."

Kim

As the novel progresses the characters of Barnaby and Hugh become more interesting as individuals. As you comment in the recaps their interrelationship also becomes more and more intriguing. What a great question you ask. What was the relationship between them before the riots when they were both at The Maypole? To what extent does Barnaby’s innocence lead him towards Hugh and the destructive nature of the Gordon Riots? Can we go so far as to say Hugh is exploiting Barnaby’s naïveté?

I found it very interesting that one way we can identify the difference between Hugh and Barnaby is through the cleanliness of Barnaby. By his act of washing in the morning we see his link with his mother, who no doubt encouraged his early habits. Now he washes in the presence of the rioters. How much of Barnaby’s cleanliness and innocence and other good habits will be perverted by Hugh and the rioters? And now a bit of a stretch perhaps. If we are considering the vein of suggested references to Christ and His story does Barnaby’s washing and cleanliness add to the allusion? Water, purity, innocence ...?

Generally Dickens’s minor characters are very flat in nature. As we move through this novel I am feeling more and more like characters such as Hugh and Barnaby are more developed psychologically than other flat characters.

Kim

As the novel progresses the characters of Barnaby and Hugh become more interesting as individuals. As you comment in the recaps their interrelationship also becomes more and more intriguing. What a great question you ask. What was the relationship between them before the riots when they were both at The Maypole? To what extent does Barnaby’s innocence lead him towards Hugh and the destructive nature of the Gordon Riots? Can we go so far as to say Hugh is exploiting Barnaby’s naïveté?

I found it very interesting that one way we can identify the difference between Hugh and Barnaby is through the cleanliness of Barnaby. By his act of washing in the morning we see his link with his mother, who no doubt encouraged his early habits. Now he washes in the presence of the rioters. How much of Barnaby’s cleanliness and innocence and other good habits will be perverted by Hugh and the rioters? And now a bit of a stretch perhaps. If we are considering the vein of suggested references to Christ and His story does Barnaby’s washing and cleanliness add to the allusion? Water, purity, innocence ...?

Generally Dickens’s minor characters are very flat in nature. As we move through this novel I am feeling more and more like characters such as Hugh and Barnaby are more developed psychologically than other flat characters.

Mary Lou wrote: "I don't think I've ever read 500+ pages into a book, and still had no idea who the protagonist is. It must be Gabriel -- he's the most winsome character in the book, but he's certainly not the typical heroic central character, is he?"

At least he's maybe the only character that seems to keep his wits together without being a mean, sly whatyamacallit like Chester or Gashford. And he is heroic in his own way; he's not one for big words or actions that get the most attention, but he stands for what's important to him. The way he keeps calm towards Sam and tries to help him, while he also stands his ground in not wanting to seem to support a cause he despises just to save his own skin, tells very much about his character.

I must admit, I was pretty appalled mostly by the last chapter. The rioters were violent before that, but somehow in this chapter it was so ... violent, with heads melting from roof lead and such. Dickens did a very good job showing the horrors of the riots in this chapter - and the way the individual rioters might have felt like they belonged for once, but were very unimportant to each other in the end.

At least he's maybe the only character that seems to keep his wits together without being a mean, sly whatyamacallit like Chester or Gashford. And he is heroic in his own way; he's not one for big words or actions that get the most attention, but he stands for what's important to him. The way he keeps calm towards Sam and tries to help him, while he also stands his ground in not wanting to seem to support a cause he despises just to save his own skin, tells very much about his character.

I must admit, I was pretty appalled mostly by the last chapter. The rioters were violent before that, but somehow in this chapter it was so ... violent, with heads melting from roof lead and such. Dickens did a very good job showing the horrors of the riots in this chapter - and the way the individual rioters might have felt like they belonged for once, but were very unimportant to each other in the end.

Kim wrote: "I just got back from walking Willow and it was an awful walk. We were so very hot, it is 90 degrees or so out there and I'm surprised we made it back without burning to cinders. So I came in, got b..."

Wow! The spectre arrives at The Maypole. What is he doing there?

“As though he held a knife and stabbed it in to the heart ... the Bell tolled on ... “.

The bell tolls on, then it ceases, and then we read that there were the shrieks of women and the fluttering of clothes. If the shrieks were those of Dolly and Emma and it was them who were ringing the bell, then we need to worry about their safety. If we reflect on the fact that the spectre is ... then how symbolic that the ringing of the bell makes him simulate a stabbing motion. That, added to the fact that one of the bell ringers was Emma Haredale, makes his responsive action of trying to stop the noise of the bell very dramatic and telling.

The section of the text highlighted by Kim is an example of Dickens at his most dramatic, most creative, most suggestive, most powerful.

Wow! The spectre arrives at The Maypole. What is he doing there?

“As though he held a knife and stabbed it in to the heart ... the Bell tolled on ... “.

The bell tolls on, then it ceases, and then we read that there were the shrieks of women and the fluttering of clothes. If the shrieks were those of Dolly and Emma and it was them who were ringing the bell, then we need to worry about their safety. If we reflect on the fact that the spectre is ... then how symbolic that the ringing of the bell makes him simulate a stabbing motion. That, added to the fact that one of the bell ringers was Emma Haredale, makes his responsive action of trying to stop the noise of the bell very dramatic and telling.

The section of the text highlighted by Kim is an example of Dickens at his most dramatic, most creative, most suggestive, most powerful.

I was so horrified by the possibility that Emma and Dolly were in that house. I thought some comment was made about them being present in the house during the invasion of the Maypole. Am I correct in that? I certainly hope they were either not there or did manage to escape. Also, the man who found John Willet in the Maypole, what happened to him? He did seem appalled in the circumstances as well. So many questions.

I was so horrified by the possibility that Emma and Dolly were in that house. I thought some comment was made about them being present in the house during the invasion of the Maypole. Am I correct in that? I certainly hope they were either not there or did manage to escape. Also, the man who found John Willet in the Maypole, what happened to him? He did seem appalled in the circumstances as well. So many questions.

Mary Lou wrote: "Varden's brave stance in chapter 51 is admirable (even if his charity towards Sim is misguided). But when we read about the debauchery at the Maypole and then the absolute barbarism at the Warren, we realize how truly brave Varden is."

Mary Lou wrote: "Varden's brave stance in chapter 51 is admirable (even if his charity towards Sim is misguided). But when we read about the debauchery at the Maypole and then the absolute barbarism at the Warren, we realize how truly brave Varden is."Varden's a case study in decency, isn't he? Maybe he overdoes it by taking too much abuse from his wife and servants, but on the whole he's a breath of fresh air in this book, and whenever he gets a little speech I am cheering along. I do wonder why the book wasn't named for him instead of Barnaby.

Mary Lou wrote: "SO MANY LOOSE THREADS!

~ Where is Joe?

~ Where are Dolly and Emma?

~ Who is targeting Mrs. Rudge? And is that mysterious person the same as Soloman's ghost? And the man who left Willet tied up in ..."

Hi Mary Lou

I too share your sense of exhaustion (in a good way) with the novel. It just keeps going full steam ahead, but as readers we are still not sure where it is headed, who and where many of the characters are, and what direction the Riots will take next.

I must admit that Barnaby Rudge was one of my least favourite Dickens novels before this most recent read. I was so wrong. As we move through the novel my opinion of it increases every week.

The “spectre” and the thread of what will happen to Barnaby are

uppermost in my mind.

~ Where is Joe?

~ Where are Dolly and Emma?

~ Who is targeting Mrs. Rudge? And is that mysterious person the same as Soloman's ghost? And the man who left Willet tied up in ..."

Hi Mary Lou

I too share your sense of exhaustion (in a good way) with the novel. It just keeps going full steam ahead, but as readers we are still not sure where it is headed, who and where many of the characters are, and what direction the Riots will take next.

I must admit that Barnaby Rudge was one of my least favourite Dickens novels before this most recent read. I was so wrong. As we move through the novel my opinion of it increases every week.

The “spectre” and the thread of what will happen to Barnaby are

uppermost in my mind.

Bobbie wrote: "I was so horrified by the possibility that Emma and Dolly were in that house. I thought some comment was made about them being present in the house during the invasion of the Maypole. Am I correct ..."

Bobbie wrote: "I was so horrified by the possibility that Emma and Dolly were in that house. I thought some comment was made about them being present in the house during the invasion of the Maypole. Am I correct ..."I was really confused by this, too. If Emma and Dolly are in the house, then why is there no mention of this when it's burning down? Unless Hugh went after them or something when he disappeared--which given his history with Dolly is not a happy thought.

Kim wrote: "Hello everyone,

Kim wrote: "Hello everyone,Tristram is away on his holiday for the next few weeks so you are stuck with me. While we are moving along with Barnaby and Hugh and smashing things and burning things, Tristram is..."

Thanks for subbing in, Kim! I really enjoyed reading these, including the questions of which you seem to have found more than you let on. :)

I hope Tristram's having a good vacation.

John Willet stunned in his chair is so very tragic. He's been one of my favorite characters and I just hate to see him come to this. I'm far more struck and saddened by this scene than by the shrieking mother from the last set of chapters. Dickens has done so much more to lay the ground for the destruction of John, who is a very, very flawed person but nonetheless a person, and who deserves better than to see his life's work treated like this.

John Willet stunned in his chair is so very tragic. He's been one of my favorite characters and I just hate to see him come to this. I'm far more struck and saddened by this scene than by the shrieking mother from the last set of chapters. Dickens has done so much more to lay the ground for the destruction of John, who is a very, very flawed person but nonetheless a person, and who deserves better than to see his life's work treated like this.It's also interesting to see how Dickens uses John's distress as a way to elicit the different characters of Hugh and Dennis. This is very good kill-two-birds-with-one-stone writing, or three birds: we get a further development of John's character, a deepening of our understanding of the riot and its destructive forces, and a clearer sense of how far different rioters might take things and what that says about them.

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

Upon his return he had to lament a domestic calamity, which, for its connection with that famous personage in Barnaby, must be mentioned here. The raven had for some days been ailing, and Topping had reported of him, as Shakspeare of Hamlet, that he had lost his mirth and foregone all customary exercises; but Dickens paid no great heed, remembering his recovery from an illness of the previous summer when he swallowed some white paint; so that the graver report which led him to send for the doctor came upon him unexpectedly, and nothing but his own language can worthily describe the result. Unable from the state of his feelings to write two letters, he sent the narrative to Maclise, under an enormous black seal, for transmission to me; and thus it befell that this fortunate bird receives a double passport to fame, so great a humorist having celebrated his farewell to the present world, and so great a painter his welcome to another.

"You will be greatly shocked" (the letter is dated Friday evening, March 12, 1841) "and grieved to hear that the Raven is no more. He expired to-day at a few minutes after twelve o'clock at noon. He had been ailing for a few days, but we anticipated no serious result, conjecturing that a portion of the white paint he swallowed last summer might be lingering about his vitals without having any serious effect upon his constitution. Yesterday afternoon he was taken so much worse that I sent an express for the medical gentleman (Mr. Herring), who promptly attended, and administered a powerful dose of castor oil. Under the influence of this medicine, he recovered so far as to be able at eight o'clock p.m. to bite Topping. His night was peaceful. This morning at daybreak he appeared better; received (agreeably to the doctor's directions) another dose of castor oil; and partook plentifully of some warm gruel, the flavor of which he appeared to relish. Towards eleven o'clock he was so much worse that it was found necessary to muffle the stable-knocker. At half-past, or thereabouts, he was heard talking to himself about the horse and Topping's family, and to add some incoherent expressions which are supposed to have been either a foreboding of his approaching dissolution, or some wishes relative to the disposal of his little property: consisting chiefly of half-pence which he had buried in different parts of the garden. On the clock striking twelve he appeared slightly agitated, but he soon recovered, walked twice or thrice along the coach-house, stopped to bark, staggered, exclaimed Halloa old girl! (his favorite expression), and died.

"He behaved throughout with a decent fortitude, equanimity, and self-possession, which cannot be too much admired. I deeply regret that being in ignorance of his danger I did not attend to receive his last instructions. Something remarkable about his eyes occasioned Topping to run for the doctor at twelve. When they returned together our friend was gone. It was the medical gentleman who informed me of his decease. He did it with great caution and delicacy, preparing me by the remark that 'a jolly queer start had taken place;' but the shock was very great notwithstanding. I am not wholly free from suspicions of poison. A malicious butcher has been heard to say that he would 'do' for him: his plea was that he would not be molested in taking orders down the mews, by any bird that wore a tail. Other persons have also been heard to threaten: among others, Charles Knight, who has just started a weekly publication price fourpence: Barnaby being, as you know, threepence. I have directed a post-mortem examination, and the body has been removed to Mr. Herring's school of anatomy for that purpose.

"I could wish, if you can take the trouble, that you could inclose this to Forster immediately after you have read it. I cannot discharge the painful task of communication more than once. Were they ravens who took manna to somebody in the wilderness? At times I hope they were, and at others I fear they were not, or they would certainly have stolen it by the way. In profound sorrow, I am ever your bereaved friend

C. D.

Kate is as well as can be expected, but terribly low, as you may suppose. The children seem rather glad of it. He bit their ankles. But that was play."

Upon his return he had to lament a domestic calamity, which, for its connection with that famous personage in Barnaby, must be mentioned here. The raven had for some days been ailing, and Topping had reported of him, as Shakspeare of Hamlet, that he had lost his mirth and foregone all customary exercises; but Dickens paid no great heed, remembering his recovery from an illness of the previous summer when he swallowed some white paint; so that the graver report which led him to send for the doctor came upon him unexpectedly, and nothing but his own language can worthily describe the result. Unable from the state of his feelings to write two letters, he sent the narrative to Maclise, under an enormous black seal, for transmission to me; and thus it befell that this fortunate bird receives a double passport to fame, so great a humorist having celebrated his farewell to the present world, and so great a painter his welcome to another.

"You will be greatly shocked" (the letter is dated Friday evening, March 12, 1841) "and grieved to hear that the Raven is no more. He expired to-day at a few minutes after twelve o'clock at noon. He had been ailing for a few days, but we anticipated no serious result, conjecturing that a portion of the white paint he swallowed last summer might be lingering about his vitals without having any serious effect upon his constitution. Yesterday afternoon he was taken so much worse that I sent an express for the medical gentleman (Mr. Herring), who promptly attended, and administered a powerful dose of castor oil. Under the influence of this medicine, he recovered so far as to be able at eight o'clock p.m. to bite Topping. His night was peaceful. This morning at daybreak he appeared better; received (agreeably to the doctor's directions) another dose of castor oil; and partook plentifully of some warm gruel, the flavor of which he appeared to relish. Towards eleven o'clock he was so much worse that it was found necessary to muffle the stable-knocker. At half-past, or thereabouts, he was heard talking to himself about the horse and Topping's family, and to add some incoherent expressions which are supposed to have been either a foreboding of his approaching dissolution, or some wishes relative to the disposal of his little property: consisting chiefly of half-pence which he had buried in different parts of the garden. On the clock striking twelve he appeared slightly agitated, but he soon recovered, walked twice or thrice along the coach-house, stopped to bark, staggered, exclaimed Halloa old girl! (his favorite expression), and died.

"He behaved throughout with a decent fortitude, equanimity, and self-possession, which cannot be too much admired. I deeply regret that being in ignorance of his danger I did not attend to receive his last instructions. Something remarkable about his eyes occasioned Topping to run for the doctor at twelve. When they returned together our friend was gone. It was the medical gentleman who informed me of his decease. He did it with great caution and delicacy, preparing me by the remark that 'a jolly queer start had taken place;' but the shock was very great notwithstanding. I am not wholly free from suspicions of poison. A malicious butcher has been heard to say that he would 'do' for him: his plea was that he would not be molested in taking orders down the mews, by any bird that wore a tail. Other persons have also been heard to threaten: among others, Charles Knight, who has just started a weekly publication price fourpence: Barnaby being, as you know, threepence. I have directed a post-mortem examination, and the body has been removed to Mr. Herring's school of anatomy for that purpose.

"I could wish, if you can take the trouble, that you could inclose this to Forster immediately after you have read it. I cannot discharge the painful task of communication more than once. Were they ravens who took manna to somebody in the wilderness? At times I hope they were, and at others I fear they were not, or they would certainly have stolen it by the way. In profound sorrow, I am ever your bereaved friend

C. D.

Kate is as well as can be expected, but terribly low, as you may suppose. The children seem rather glad of it. He bit their ankles. But that was play."

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

"I have shut myself up by myself to-day, and mean to try and 'go it' at the Clock; Kate being out, and the house peacefully dismal. I don't remember altering the exact part you object to, but if there be anything here you object to, knock it out ruthlessly." "Don't fail" (April the 5th) "to erase anything that seems to you too strong. It is difficult for me to judge what tells too much, and what does not. I am trying a very quiet number to set against this necessary one. I hope it will be good, but I am in very sad condition for work. Glad you think this powerful. What I have put in is more relief, from the raven."

Two days later: "I have done that number, and am now going to work on another. I am bent (please Heaven) on finishing the first chapter by Friday night. I hope to look in upon you to-night, when we'll dispose of the toasts for Saturday. Still bilious—but a good number, I hope, notwithstanding. Jeffrey has come to town, and was here yesterday."

The toasts to be disposed of were those to be given at the dinner on the 10th to celebrate the second volume of Master Humphrey: when Talfourd presided, when there was much jollity, and, according to the memorandum drawn up that Saturday night now lying before me, we all in the greatest good humor glorified each other: Talfourd proposing the Clock, Macready Mrs. Dickens, Dickens the publishers, and myself the artists; Macready giving Talfourd, Talfourd Macready, Dickens myself, and myself the comedian Mr. Harley, whose humorous songs had been the not least considerable element in the mirth of the evening. Five days later he writes:

"I am getting on very slowly. I want to stick to the story; and the fear of committing myself, because of the impossibility of trying back or altering a syllable, makes it much harder than it looks. It was too bad of me to give you the trouble of cutting the number, but I knew so well you would do it in the right places. For what Harley would call the 'onward work' I really think I have some famous thoughts."

There is an interval of a month before the next allusion:

"Solomon's expression" (3d of June) "I meant to be one of those strong ones to which strong circumstances give birth in the commonest minds. Deal with it as you like. . . . Say what you please of Gordon" (I had objected to some points in his view of this madman, stated much too favorably as I thought), "he must have been at heart a kind man, and a lover of the despised and rejected, after his own fashion. He lived upon a small income, and always within it; was known to relieve the necessities of many people; exposed in his place the corrupt attempt of a minister to buy him out of Parliament; and did great charities in Newgate. He always spoke on the people's side, and tried against his muddled brains to expose the profligacy of both parties. He never got anything by his madness, and never sought it. The wildest and most raging attacks of the time allow him these merits: and not to let him have 'em in their full extent, remembering in what a (politically) wicked time he lived, would lie upon my conscience heavily. The libel he was imprisoned for when he died, was on the Queen of France; and the French government interested themselves warmly to procure his release,—which I think they might have done, but for Lord Grenville."

I was more successful in the counsel I gave against a fancy he had at this part of the story, that he would introduce as actors in the Gordon riots three splendid fellows who should order, lead, control, and be obeyed as natural guides of the crowd in that delirious time, and who should turn out, when all was over, to have broken out from Bedlam; but, though he saw the unsoundness of this, he could not so readily see, in Gordon's case, the danger of taxing ingenuity to ascribe a reasonable motive to acts of sheer insanity. The feeblest parts of the book are those in which Lord George and his secretary appear.

"I have shut myself up by myself to-day, and mean to try and 'go it' at the Clock; Kate being out, and the house peacefully dismal. I don't remember altering the exact part you object to, but if there be anything here you object to, knock it out ruthlessly." "Don't fail" (April the 5th) "to erase anything that seems to you too strong. It is difficult for me to judge what tells too much, and what does not. I am trying a very quiet number to set against this necessary one. I hope it will be good, but I am in very sad condition for work. Glad you think this powerful. What I have put in is more relief, from the raven."

Two days later: "I have done that number, and am now going to work on another. I am bent (please Heaven) on finishing the first chapter by Friday night. I hope to look in upon you to-night, when we'll dispose of the toasts for Saturday. Still bilious—but a good number, I hope, notwithstanding. Jeffrey has come to town, and was here yesterday."

The toasts to be disposed of were those to be given at the dinner on the 10th to celebrate the second volume of Master Humphrey: when Talfourd presided, when there was much jollity, and, according to the memorandum drawn up that Saturday night now lying before me, we all in the greatest good humor glorified each other: Talfourd proposing the Clock, Macready Mrs. Dickens, Dickens the publishers, and myself the artists; Macready giving Talfourd, Talfourd Macready, Dickens myself, and myself the comedian Mr. Harley, whose humorous songs had been the not least considerable element in the mirth of the evening. Five days later he writes:

"I am getting on very slowly. I want to stick to the story; and the fear of committing myself, because of the impossibility of trying back or altering a syllable, makes it much harder than it looks. It was too bad of me to give you the trouble of cutting the number, but I knew so well you would do it in the right places. For what Harley would call the 'onward work' I really think I have some famous thoughts."

There is an interval of a month before the next allusion:

"Solomon's expression" (3d of June) "I meant to be one of those strong ones to which strong circumstances give birth in the commonest minds. Deal with it as you like. . . . Say what you please of Gordon" (I had objected to some points in his view of this madman, stated much too favorably as I thought), "he must have been at heart a kind man, and a lover of the despised and rejected, after his own fashion. He lived upon a small income, and always within it; was known to relieve the necessities of many people; exposed in his place the corrupt attempt of a minister to buy him out of Parliament; and did great charities in Newgate. He always spoke on the people's side, and tried against his muddled brains to expose the profligacy of both parties. He never got anything by his madness, and never sought it. The wildest and most raging attacks of the time allow him these merits: and not to let him have 'em in their full extent, remembering in what a (politically) wicked time he lived, would lie upon my conscience heavily. The libel he was imprisoned for when he died, was on the Queen of France; and the French government interested themselves warmly to procure his release,—which I think they might have done, but for Lord Grenville."

I was more successful in the counsel I gave against a fancy he had at this part of the story, that he would introduce as actors in the Gordon riots three splendid fellows who should order, lead, control, and be obeyed as natural guides of the crowd in that delirious time, and who should turn out, when all was over, to have broken out from Bedlam; but, though he saw the unsoundness of this, he could not so readily see, in Gordon's case, the danger of taxing ingenuity to ascribe a reasonable motive to acts of sheer insanity. The feeblest parts of the book are those in which Lord George and his secretary appear.

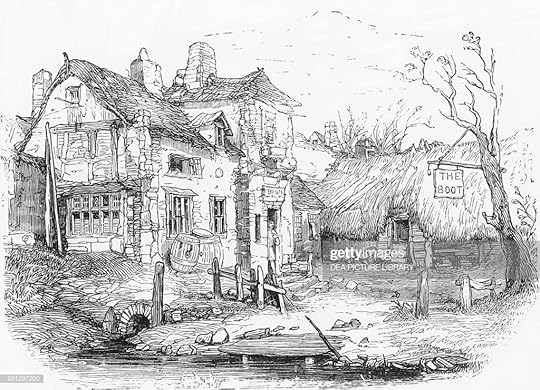

The rioter's headquarters

Chapter 51

George Cattermole

Text Illustrated:

A mob is usually a creature of very mysterious existence, particularly in a large city. Where it comes from or whither it goes, few men can tell. Assembling and dispersing with equal suddenness, it is as difficult to follow to its various sources as the sea itself; nor does the parallel stop here, for the ocean is not more fickle and uncertain, more terrible when roused, more unreasonable, or more cruel.

The people who were boisterous at Westminster upon the Friday morning, and were eagerly bent upon the work of devastation in Duke Street and Warwick Street at night, were, in the mass, the same. Allowing for the chance accessions of which any crowd is morally sure in a town where there must always be a large number of idle and profligate persons, one and the same mob was at both places. Yet they spread themselves in various directions when they dispersed in the afternoon, made no appointment for reassembling, had no definite purpose or design, and indeed, for anything they knew, were scattered beyond the hope of future union.

At The Boot, which, as has been shown, was in a manner the head-quarters of the rioters, there were not, upon this Friday night, a dozen people. Some slept in the stable and outhouses, some in the common room, some two or three in beds. The rest were in their usual homes or haunts. Perhaps not a score in all lay in the adjacent fields and lanes, and under haystacks, or near the warmth of brick-kilns, who had not their accustomed place of rest beneath the open sky. As to the public ways within the town, they had their ordinary nightly occupants, and no others; the usual amount of vice and wretchedness, but no more.

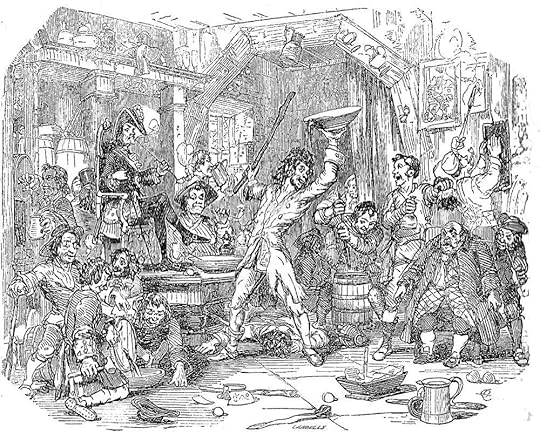

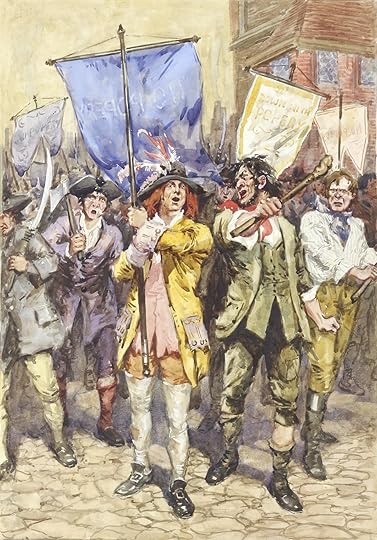

The rioters with their spoils

Chapter 52

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Without the slightest preparation, saving that they carried clubs and wore the blue cockade, they sallied out into the streets; and, with no more settled design than that of doing as much mischief as they could, paraded them at random. Their numbers rapidly increasing, they soon divided into parties; and agreeing to meet by-and-by, in the fields near Welbeck Street, scoured the town in various directions. The largest body, and that which augmented with the greatest rapidity, was the one to which Hugh and Barnaby belonged. This took its way towards Moorfields, where there was a rich chapel, and in which neighbourhood several Catholic families were known to reside.

Beginning with the private houses so occupied, they broke open the doors and windows; and while they destroyed the furniture and left but the bare walls, made a sharp search for tools and engines of destruction, such as hammers, pokers, axes, saws, and such like instruments. Many of the rioters made belts of cord, of handkerchiefs, or any material they found at hand, and wore these weapons as openly as pioneers upon a field-day. There was not the least disguise or concealment—indeed, on this night, very little excitement or hurry. From the chapels, they tore down and took away the very altars, benches, pulpits, pews, and flooring; from the dwelling-houses, the very wainscoting and stairs. This Sunday evening’s recreation they pursued like mere workmen who had a certain task to do, and did it. Fifty resolute men might have turned them at any moment; a single company of soldiers could have scattered them like dust; but no man interposed, no authority restrained them, and, except by the terrified persons who fled from their approach, they were as little heeded as if they were pursuing their lawful occupations with the utmost sobriety and good conduct.

In the same manner, they marched to the place of rendezvous agreed upon, made great fires in the fields, and reserving the most valuable of their spoils, burnt the rest. Priestly garments, images of saints, rich stuffs and ornaments, altar-furniture and household goods, were cast into the flames, and shed a glare on the whole country round; but they danced and howled, and roared about these fires till they were tired, and were never for an instant checked.

The secretary's watch

Chapter 53

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

There still remained the fourth body, and for that the secretary looked with a most intense eagerness. At last it came up. It was numerous, and composed of picked men; for as he gazed down among them, he recognised many upturned faces which he knew well—those of Simon Tappertit, Hugh, and Dennis in the front, of course. They halted and cheered, as the others had done; but when they moved again, they did not, like them, proclaim what design they had. Hugh merely raised his hat upon the bludgeon he carried, and glancing at a spectator on the opposite side of the way, was gone.