The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

MC Chapters 9-10

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 9

Hello Curiosities

This is a long chapter, a very long chapter. At times, the description of Todgers’s seemed excessive to me. It read almost like it came from Sketches of Boz. Let’s get to it, shall we?

Dickens begins the chapter by telling us that in all the world there was not another place like Todgers’s. We learn that you cannot simply walk about in Todgers’s neighbourhood but must grope your way “for an hour through lanes and bye-ways, and courtyards, and passages.” We are told that more than once people who tried to navigate their way through Todgers’s simply gave up and returned to their own homes. There are many inhabitants of the area who were born, live, and will die in the region. Todgers’s itself is a commercial boarding house in the neighbourhood. It is a place with one window that has not been opened for at least 100 years. Its cellar is mysterious and the top of the house is worthy of notice if for no other reason than you could see the shadow of the Monument and a great variety of belfries, steeples, masts of ships and the like.

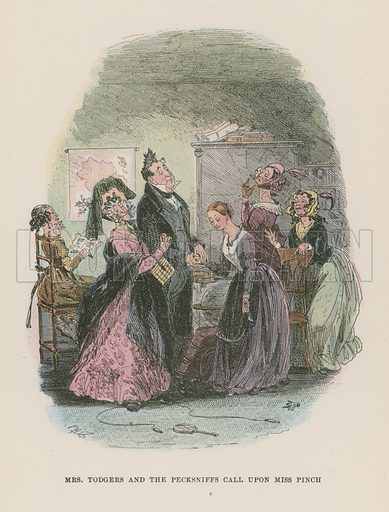

We learn that Mrs Todgers had once received the attentions of Mr Pecksniff. Mrs Todgers tells Mercy and Grace Pecksniff how difficult her life has been and the young ladies form the conclusion that Mrs Todgers struggles in life are similar to their father’s trials with Tom Pinch. This leap of logic was astonishing to me, but I’m learning to deal with the Pecksniffian surprises as best I can. The daughters launch into a condemnation of Tom Pinch and extend their condemnation to Tom’s sister who by her “presuming to exist at all is sufficient to kill one, but to see her - oh my stars!” Nothing like a healthy dose of pre-judgement. Pecksniff himself enters the room and we learn that he and his daughters are going to see Tom Pinch's sister. During this meeting, Mr Pecksniff’s arm manages to make it around Mrs Todgers’s waist. Hmmm?

Thoughts

Did you, like me, find the description of Todgers’s and the surrounding area excessive, or did you find it folded into the chapter effectively?

How might this description suggest or foreshadow events that might occur?

What is your impression of Mrs Todgers? What lead you to that decision?

We learn that Tom Pinch’s sister is a governess in a “lofty family; perhaps the wealthiest brass and copper founders’ family known to mankind.” Along with one “big” and one “giant’s” Dickens uses the word “great” eight times in one paragraph to describe the house. Mr Pecksniff, Mrs Todgers, Mercy and Charity make their way to this mansion and meet with Miss Pinch who turns out to be nothing like the Pecksniff’s assumed. Ruth Pinch has a pleasant face, a little figure, and is neat. Like her brother, Ruth has a gentle manner and is far from being the fright predicted by the Pecksniff sisters. Pecksniff introduces himself to Miss Pinch with his usual pompous fake humility and we learn from Miss Pinch’s speech to him that her brother speaks well of Pecksniff and his daughters and she thanks them for their kindness to her brother. Ruth Pinch, like her brother Tom, seem to share a common trait of always looking on the best side of everything. Pecksniff, his daughters, and Mrs Todgers cannot help but lavish praise on Ruth’s student and Pecksniff makes sure he gives a footman one of his cards. Mrs Todgers, not to be outdone, hands one of her cards to the footman as well. As Pecksniff and his entourage leave the mansion he comments on its architecture. Pecksniff is, of course, because of his students, an expert in his own mind on architecture. Outside Pecksniff spots a man looking out a window, assumes it is the proprietor of the house, only to be told to “come off the grass.”

Thoughts

What are your first impressions of Ruth Pinch? Do you think Dickens might continue to develop her character as the novel progresses? Why?

Do we learn anything more about Pecksniff and Todgers from this short visit to Ruth?

How could this visit be important later in the novel?

Sadly, this visit has created some problems for Ruth as her pupil has complained to “headquarters” about the visit. It is evident that Ruth Pinch may have a job in this wealthy home, but she is nevertheless in a very strict home where she is not appreciated. She, like her brother, share two common traits. First, they are both cheerful, albeit perhaps naive people, and second, their place of work or education is horrid.

Back at Todgers’s, it’s Saturday evening, a time it seems for people to expend energy and seek enjoyment. Key among the people was the boy Bailey who worked at Todgers’s. It seems that his purpose in the chapter is to create some humour. It will be interesting to see if Dickens brings Bailey back into our plot as he did Trabb’s boy or Joe the fat boy. We shall see.

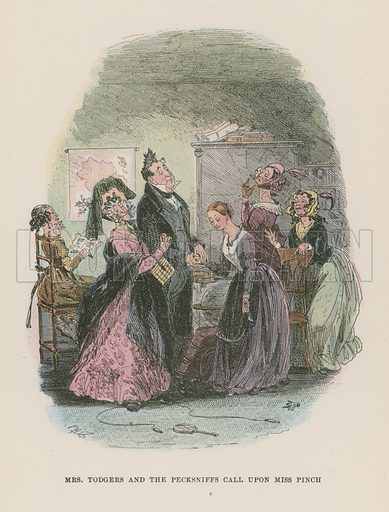

Sunday dinner at Todgers’s is exciting as well. Pecksniff’s two daughters are to be in attendance with the gentleman borders. Mercy and Charity are introduced and it becomes a splendid occasion. Mr Jenkins as the senior and highly respected border gets to play the role of senior inhabitant and escort. The remainder of the residents at Todgers’s get into the spirit and we have quite the parade of people in the banquet hall of Todgers’s. What follows next is a lengthy dinner where each of the characters seem to parody the rich. To sum up, Dickens, with gentle but still a mocking tone, comments “Oh, Todgers’s could do it when it chose! Mind that.” At this point, I think Dickens for the second time slips into a Sketches by Boz mode and we have an extended description of the residents of Todgers’s drinking, making speeches, breaking glasses and the like. Slightly inebriated, the men bumble around the women. As for Pecksniff, he finds himself with Mrs Todgers and explains that he is rather somber since he is thinking of his beautiful departed wife who had “a small property” and his daughters and reveals to Mrs Todgers that he has a chronic medical issue. The issue seems to be that Mrs Todgers reminds Pecksniff of his former wife. He begins to squeeze her very tightly, and she asks him to stop. To that, Pecksniff replies that Mrs Todgers is very much like his wife. At this point it seems that Dickens has slipped into a rather theatrical mode of comedy or even farce. Pecksniff says he is lonely and Todgers says he is a gentleman. Again, hmmm. Is anything brewing here?

Overcome with emotion, Pecksniff gives his pitch for more architecture students to Mrs Todgers. Can he be that drunk? Well, after this speech he does fall into the fire-place only to be immediately rescued by a young border. Pecksniff is carried upstairs to bed but he reappears to talk some more. He is put to bed once more and gets up once more. Funny I imagine in a theatrical farce, but annoying to me in prose. The chapter ends with Pecksniff being locked in his room.

Thoughts

Oh my, but I found this chapter annoying. True, there were elements of humour concerning the Sunday supper but its aftermath seemed to spin out of control. What are your thoughts about the last few pages of this chapter?

Hello Curiosities

This is a long chapter, a very long chapter. At times, the description of Todgers’s seemed excessive to me. It read almost like it came from Sketches of Boz. Let’s get to it, shall we?

Dickens begins the chapter by telling us that in all the world there was not another place like Todgers’s. We learn that you cannot simply walk about in Todgers’s neighbourhood but must grope your way “for an hour through lanes and bye-ways, and courtyards, and passages.” We are told that more than once people who tried to navigate their way through Todgers’s simply gave up and returned to their own homes. There are many inhabitants of the area who were born, live, and will die in the region. Todgers’s itself is a commercial boarding house in the neighbourhood. It is a place with one window that has not been opened for at least 100 years. Its cellar is mysterious and the top of the house is worthy of notice if for no other reason than you could see the shadow of the Monument and a great variety of belfries, steeples, masts of ships and the like.

We learn that Mrs Todgers had once received the attentions of Mr Pecksniff. Mrs Todgers tells Mercy and Grace Pecksniff how difficult her life has been and the young ladies form the conclusion that Mrs Todgers struggles in life are similar to their father’s trials with Tom Pinch. This leap of logic was astonishing to me, but I’m learning to deal with the Pecksniffian surprises as best I can. The daughters launch into a condemnation of Tom Pinch and extend their condemnation to Tom’s sister who by her “presuming to exist at all is sufficient to kill one, but to see her - oh my stars!” Nothing like a healthy dose of pre-judgement. Pecksniff himself enters the room and we learn that he and his daughters are going to see Tom Pinch's sister. During this meeting, Mr Pecksniff’s arm manages to make it around Mrs Todgers’s waist. Hmmm?

Thoughts

Did you, like me, find the description of Todgers’s and the surrounding area excessive, or did you find it folded into the chapter effectively?

How might this description suggest or foreshadow events that might occur?

What is your impression of Mrs Todgers? What lead you to that decision?

We learn that Tom Pinch’s sister is a governess in a “lofty family; perhaps the wealthiest brass and copper founders’ family known to mankind.” Along with one “big” and one “giant’s” Dickens uses the word “great” eight times in one paragraph to describe the house. Mr Pecksniff, Mrs Todgers, Mercy and Charity make their way to this mansion and meet with Miss Pinch who turns out to be nothing like the Pecksniff’s assumed. Ruth Pinch has a pleasant face, a little figure, and is neat. Like her brother, Ruth has a gentle manner and is far from being the fright predicted by the Pecksniff sisters. Pecksniff introduces himself to Miss Pinch with his usual pompous fake humility and we learn from Miss Pinch’s speech to him that her brother speaks well of Pecksniff and his daughters and she thanks them for their kindness to her brother. Ruth Pinch, like her brother Tom, seem to share a common trait of always looking on the best side of everything. Pecksniff, his daughters, and Mrs Todgers cannot help but lavish praise on Ruth’s student and Pecksniff makes sure he gives a footman one of his cards. Mrs Todgers, not to be outdone, hands one of her cards to the footman as well. As Pecksniff and his entourage leave the mansion he comments on its architecture. Pecksniff is, of course, because of his students, an expert in his own mind on architecture. Outside Pecksniff spots a man looking out a window, assumes it is the proprietor of the house, only to be told to “come off the grass.”

Thoughts

What are your first impressions of Ruth Pinch? Do you think Dickens might continue to develop her character as the novel progresses? Why?

Do we learn anything more about Pecksniff and Todgers from this short visit to Ruth?

How could this visit be important later in the novel?

Sadly, this visit has created some problems for Ruth as her pupil has complained to “headquarters” about the visit. It is evident that Ruth Pinch may have a job in this wealthy home, but she is nevertheless in a very strict home where she is not appreciated. She, like her brother, share two common traits. First, they are both cheerful, albeit perhaps naive people, and second, their place of work or education is horrid.

Back at Todgers’s, it’s Saturday evening, a time it seems for people to expend energy and seek enjoyment. Key among the people was the boy Bailey who worked at Todgers’s. It seems that his purpose in the chapter is to create some humour. It will be interesting to see if Dickens brings Bailey back into our plot as he did Trabb’s boy or Joe the fat boy. We shall see.

Sunday dinner at Todgers’s is exciting as well. Pecksniff’s two daughters are to be in attendance with the gentleman borders. Mercy and Charity are introduced and it becomes a splendid occasion. Mr Jenkins as the senior and highly respected border gets to play the role of senior inhabitant and escort. The remainder of the residents at Todgers’s get into the spirit and we have quite the parade of people in the banquet hall of Todgers’s. What follows next is a lengthy dinner where each of the characters seem to parody the rich. To sum up, Dickens, with gentle but still a mocking tone, comments “Oh, Todgers’s could do it when it chose! Mind that.” At this point, I think Dickens for the second time slips into a Sketches by Boz mode and we have an extended description of the residents of Todgers’s drinking, making speeches, breaking glasses and the like. Slightly inebriated, the men bumble around the women. As for Pecksniff, he finds himself with Mrs Todgers and explains that he is rather somber since he is thinking of his beautiful departed wife who had “a small property” and his daughters and reveals to Mrs Todgers that he has a chronic medical issue. The issue seems to be that Mrs Todgers reminds Pecksniff of his former wife. He begins to squeeze her very tightly, and she asks him to stop. To that, Pecksniff replies that Mrs Todgers is very much like his wife. At this point it seems that Dickens has slipped into a rather theatrical mode of comedy or even farce. Pecksniff says he is lonely and Todgers says he is a gentleman. Again, hmmm. Is anything brewing here?

Overcome with emotion, Pecksniff gives his pitch for more architecture students to Mrs Todgers. Can he be that drunk? Well, after this speech he does fall into the fire-place only to be immediately rescued by a young border. Pecksniff is carried upstairs to bed but he reappears to talk some more. He is put to bed once more and gets up once more. Funny I imagine in a theatrical farce, but annoying to me in prose. The chapter ends with Pecksniff being locked in his room.

Thoughts

Oh my, but I found this chapter annoying. True, there were elements of humour concerning the Sunday supper but its aftermath seemed to spin out of control. What are your thoughts about the last few pages of this chapter?

I really liked chapter 9, but it became too long after a while. I did like how it gave a setting, some background, and fleshed out the Pecksniffs. Bummer, yesterday evening while reading I came across something and thought 'oh hey, here's a motif starting to happen', and I don't remember what it was!

I found these chapters particularly interesting as it feels like we’re getting small peaks at the multiple layers of Pecksniff-at times his actions are portrayed as genuine, and at others the mask slips a little. This can on first impressions come across as confusing-in particular the end to chapter 9 (merely the acts of a drunken man, mixed with genuine emotions-or is some of this scene an act?), and I was surprised he admonished his daughters giddiness after Martin senior had left the room in chapter 10-but I think ultimately he’s going to be an interesting character to unpeel the layers of.

I found these chapters particularly interesting as it feels like we’re getting small peaks at the multiple layers of Pecksniff-at times his actions are portrayed as genuine, and at others the mask slips a little. This can on first impressions come across as confusing-in particular the end to chapter 9 (merely the acts of a drunken man, mixed with genuine emotions-or is some of this scene an act?), and I was surprised he admonished his daughters giddiness after Martin senior had left the room in chapter 10-but I think ultimately he’s going to be an interesting character to unpeel the layers of.I found the last paragraph of chapter 10 enlightening on this topic-whilst eager to take Mrs Todgers to task for picking money over the moral high ground, the last paragraph was effectively saying that Pecksniff does have his price.

Finally I couldn’t not mention my favourite comedy moment so far-Pecksniffs attempt to make friends with Ruth’s employer was priceless!

Chris wrote: "I found these chapters particularly interesting as it feels like we’re getting small peaks at the multiple layers of Pecksniff-at times his actions are portrayed as genuine, and at others the mask ..."

Yes. I think your comment about choosing “money over the moral high ground” may well turn out to be very important in this novel. It will also be interesting to see what the moral high ground could be in the novel and who it ultimately favours.

Yes. I think your comment about choosing “money over the moral high ground” may well turn out to be very important in this novel. It will also be interesting to see what the moral high ground could be in the novel and who it ultimately favours.

Peter wrote: "In your mind, what exactly is it that old Chuzzlewit wants from Pecksniff? Does this further reveal anything about old Chuzzlewit’s character?"

Peter wrote: "In your mind, what exactly is it that old Chuzzlewit wants from Pecksniff? Does this further reveal anything about old Chuzzlewit’s character?"I have some hopes here. I think Old Martin is paranoid and unpleasant but not necessarily stupid, so I am not convinced he's taken in by Pecksniff (I mean, how could anybody but a Pinch be taken in by him?), and I'm wondering if Martin means to double-cross him, which would be the paranoid and unpleasant thing to do.

But I confess I skimmed the second half of this number. Two chapters of Pecksniff in a row is too many. I really feel Dickens is beating a dead horse with this character and his daughters. No wonder his sales were in trouble on this book, if he was turning out numbers of unmitigated Pecksniff.

But I also did enjoy the get-off-the-grass sequence, and I was touched by the eighteen shillings scene. Yes, please do imagine, Mr. Pecksniff, what it would take for a person to be willing to compromise their integrity for eighteen shillings. Desperation is what it would take. Mrs. Todgers is a hard worker who's barely able to stay afloat in her greasy, depressing, lightless little establishment: she needs every eighteen shillings she can scrape together. I know she's grasping and greedy herself (she'd marry Pecksniff given the chance), but I prefer her so much to the Nells and Mrs. Rudges with all their fine scruples. Mrs. Todgers is a survivor.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "In your mind, what exactly is it that old Chuzzlewit wants from Pecksniff? Does this further reveal anything about old Chuzzlewit’s character?"

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "In your mind, what exactly is it that old Chuzzlewit wants from Pecksniff? Does this further reveal anything about old Chuzzlewit’s character?"I have some hopes here. I think Old Ma..."

I absolutely agree, Julie! These two chapters were the first two that I’ve really struggled through. Dickens is spending quite a bit of time on the Pecksniffs, and I’m not sure what the pay off of that is. He’s already convinced me that they’re terrible people. For that reason, of the two, chapter 10 felt more important to the development of the plot after showing us the alliance between Chuzzlewit and Mr. Pecksniff. Interesting idea, Julie, that maybe Chuzzlewit is plotting something?

I also have to say, I’m actually shocked the Pecksniffs went to visit Ruth in chapter 9. I thought for sure they were just going to throw Tom’s letter out of the window of the carriage and carry on. I really liked Ruth. I hope we see more of her, and I'm curious to see how she fits into the novel at large. I wonder if maybe she’ll serve as an actual moral example (as opposed to the Pecksniffs) for the less scrupulous characters we’ve met so far?

I thought the party at Todger’s was very surreal. Perhaps it was seeing the Pecksniffs “let their hair down,” so to speak, that was particularly bizarre. I also felt like Mercy and Charity were being showcased in an odd way. Something about the fact that they’re two (relatively) young women entertaining a room of middle aged men was. . . uncomfortable.

I love this illustration, the looks on the faces of them all, especially the sisters and Mrs. Todgers is perfect. Perfect for making me laugh anyway.

Mrs. Todgers and The Pecksniffs Call Upon Miss Pinch

Chapter 9

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Visitors for Miss Pinch!" said the footman. He must have been an ingenious young man, for he said it very cleverly; with a nice discrimination between the cold respect with which he would have announced visitors to the family, and the warm personal interest with which he would have announced visitors to the cook.

"Visitors for Miss Pinch!"

Miss Pinch rose hastily; with such tokens of agitation as plainly declared that her list of callers was not numerous. At the same time, the little pupil became alarmingly upright, and prepared herself to take mental notes of all that might be said and done. For the lady of the establishment was curious in the natural history and habits of the animal called Governess, and encouraged her daughters to report thereon whenever occasion served; which was, in reference to all parties concerned, very laudable, improving, and pleasant.

It is a melancholy fact; but it must be related, that Mr Pinch's sister was not at all ugly. On the contrary, she had a good face; a very mild and prepossessing face; and a pretty little figure — slight and short, but remarkable for its neatness. There was something of her brother, much of him indeed, in a certain gentleness of manner, and in her look of timid trustfulness; but she was so far from being a fright, or a dowdy, or a horror, or anything else, predicted by the two Miss Pecksniffs, that those young ladies naturally regarded her with great indignation, feeling that this was by no means what they had come to see.

Miss Mercy, as having the larger share of gaiety, bore up the best against this disappointment, and carried it off, in outward show at least, with a titter; but her sister, not caring to hide her disdain, expressed it pretty openly in her looks. As to Mrs Todgers, she leaned on Mr Pecksniff's arm and preserved a kind of genteel grimness, suitable to any state of mind, and involving any shade of opinion.

"Don't be alarmed, Miss Pinch," said Mr Pecksniff, taking her hand condescendingly in one of his, and patting it with the other. "I have called to see you, in pursuance of a promise given to your brother, Thomas Pinch. My name — compose yourself, Miss Pinch — is Pecksniff." [Chapter 9, "Town and Todgers's,"]

Mrs. Todgers and The Pecksniffs Call Upon Miss Pinch

Chapter 9

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Visitors for Miss Pinch!" said the footman. He must have been an ingenious young man, for he said it very cleverly; with a nice discrimination between the cold respect with which he would have announced visitors to the family, and the warm personal interest with which he would have announced visitors to the cook.

"Visitors for Miss Pinch!"

Miss Pinch rose hastily; with such tokens of agitation as plainly declared that her list of callers was not numerous. At the same time, the little pupil became alarmingly upright, and prepared herself to take mental notes of all that might be said and done. For the lady of the establishment was curious in the natural history and habits of the animal called Governess, and encouraged her daughters to report thereon whenever occasion served; which was, in reference to all parties concerned, very laudable, improving, and pleasant.

It is a melancholy fact; but it must be related, that Mr Pinch's sister was not at all ugly. On the contrary, she had a good face; a very mild and prepossessing face; and a pretty little figure — slight and short, but remarkable for its neatness. There was something of her brother, much of him indeed, in a certain gentleness of manner, and in her look of timid trustfulness; but she was so far from being a fright, or a dowdy, or a horror, or anything else, predicted by the two Miss Pecksniffs, that those young ladies naturally regarded her with great indignation, feeling that this was by no means what they had come to see.

Miss Mercy, as having the larger share of gaiety, bore up the best against this disappointment, and carried it off, in outward show at least, with a titter; but her sister, not caring to hide her disdain, expressed it pretty openly in her looks. As to Mrs Todgers, she leaned on Mr Pecksniff's arm and preserved a kind of genteel grimness, suitable to any state of mind, and involving any shade of opinion.

"Don't be alarmed, Miss Pinch," said Mr Pecksniff, taking her hand condescendingly in one of his, and patting it with the other. "I have called to see you, in pursuance of a promise given to your brother, Thomas Pinch. My name — compose yourself, Miss Pinch — is Pecksniff." [Chapter 9, "Town and Todgers's,"]

"Do not repine, my friends," said Mr. Pecksniff, tenderly. "Do not weep for me. It is chronic."

Chapter 9

Fred Barnard

At Mrs. Todgers's rooming-house, under the influence of a little too much alcohol, Mr. Pecksniff becomes maudlin as he recalls his dead wife, and thereby reaffirms his own status as a widower.

Text Illustrated:

"Bless my life, Miss Pecksniffs!" cried Mrs. Todgers, aloud, "your dear pa's took very poorly!"

Mr. Pecksniff straightened himself by a surprising effort, as every one turned hastily towards him; and standing on his feet, regarded the assembly with a look of ineffable wisdom. Gradually it gave place to a smile; a feeble, helpless, melancholy smile; bland, almost to sickliness. "Do not repine, my friends," said Mr. Pecksniff, tenderly. "Do not weep for me. It is chronic." And with these words, after making a futile attempt to pull off his shoes, he fell into the fire-place.

The youngest gentleman in company had him out in a second. Yes, before a hair upon his head was singed, he had him on the hearth-rug. — Her father!

They gathered round, and agreed to carry him upstairs to bed.

Chapter 9

Charles Edmund Brock

Text Illustration:

‘To Parents and Guardians,’ repeated Mr Pecksniff. ‘An eligible opportunity now offers, which unites the advantages of the best practical architectural education with the comforts of a home, and the constant association with some, who, however humble their sphere and limited their capacity—observe!—are not unmindful of their moral responsibilities.’

Mrs Todgers looked a little puzzled to know what this might mean, as well she might; for it was, as the reader may perchance remember, Mr Pecksniff’s usual form of advertisement when he wanted a pupil; and seemed to have no particular reference, at present, to anything. But Mr Pecksniff held up his finger as a caution to her not to interrupt him.

‘Do you know any parent or guardian, Mrs Todgers,’ said Mr Pecksniff, ‘who desires to avail himself of such an opportunity for a young gentleman? An orphan would be preferred. Do you know of any orphan with three or four hundred pound?’

Mrs Todgers reflected, and shook her head.

‘When you hear of an orphan with three or four hundred pound,’ said Mr Pecksniff, ‘let that dear orphan’s friends apply, by letter post-paid, to S. P., Post Office, Salisbury. I don’t know who he is exactly. Don’t be alarmed, Mrs Todgers,’ said Mr Pecksniff, falling heavily against her; ‘Chronic—chronic! Let’s have a little drop of something to drink.’

‘Bless my life, Miss Pecksniffs!’ cried Mrs Todgers, aloud, ‘your dear pa’s took very poorly!’

Mr Pecksniff straightened himself by a surprising effort, as every one turned hastily towards him; and standing on his feet, regarded the assembly with a look of ineffable wisdom. Gradually it gave place to a smile; a feeble, helpless, melancholy smile; bland, almost to sickliness. ‘Do not repine, my friends,’ said Mr Pecksniff, tenderly. ‘Do not weep for me. It is chronic.’ And with these words, after making a futile attempt to pull off his shoes, he fell into the fireplace.

The youngest gentleman in company had him out in a second. Yes, before a hair upon his head was singed, he had him on the hearth-rug—her father!

She was almost beside herself. So was her sister. Jinkins consoled them both. They all consoled them. Everybody had something to say, except the youngest gentleman in company, who with a noble self-devotion did the heavy work, and held up Mr Pecksniff’s head without being taken notice of by anybody. At last they gathered round, and agreed to carry him upstairs to bed. The youngest gentleman in company was rebuked by Jinkins for tearing Mr Pecksniff’s coat! Ha, ha! But no matter.

They carried him upstairs, and crushed the youngest gentleman at every step. His bedroom was at the top of the house, and it was a long way; but they got him there in course of time. He asked them frequently on the road for a little drop of something to drink. It seemed an idiosyncrasy. The youngest gentleman in company proposed a draught of water. Mr Pecksniff called him opprobious names for the suggestion.

About the artist:

The brother of well-known fin de siècle illustrator Henry Matthew Brock (illustrator of the Gresham Imperial edition volume of Great Expectations, 1901-3), Charles Edmund Brock was a widely published English line artist and book illustrator, who signed his work "C. E. Brock."Noted for the quality of his line drawings in the manner of the early Victorian illustrators, he was the eldest of four artist brothers, sons of a specialist reader in oriental languages for Cambridge University Press. With his better known brother, H. M., Charles Edward, and Richard Brock shared a studio, in which they gathered eighteenth- and nineteenth-century artefacts and curios to use in their drawings,paintings, and book illustrations. Having trained in the studio of Henry Wiles, their careers began in the early 1890s at Macmillan. Like his brother, E. C. Brock contributed to Punch, but Charles Edmund was also a recognized painter in oils. Moreover, he illustrated Dickens's Christmas Books — A Christmas Carol, The Cricket on the Hearth, The Haunted Man, and The Battle of Life, as well as The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, Martin Chuzzlewit, various novels by Jane Austen, Swift's Gulliver's Travels, Goldsmith's Vicar of Wakefield, Thomas Hood's poems, Lamb's essays, volumes of Greek and Norse myths, and the Bible.

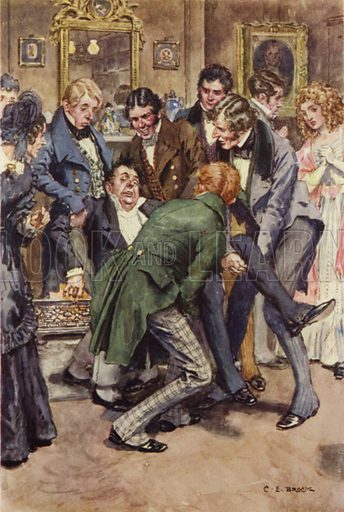

Truth prevails, and Virtue is triumphant

Chapter 10

Phiz

April 1843

Text Illustrated:

Nothing could exceed the astonishment of the two Miss Pecksniffs when they found a stranger with their dear papa. Nothing could surpass their mute amazement when he said, "My children, Mr. Chuzzlewit!" But when he told them that Mr. Chuzzlewit and he were friends, and that Mr. Chuzzlewit had said such kind and tender words as pierced his very heart, the two Miss Pecksniffs cried with one accord, "Thank Heaven for this!" and fell upon the old man’s neck. And when they had embraced him with such fervour of affection that no words can describe it, they grouped themselves about his chair, and hung over him, as figuring to themselves no earthly joy like that of ministering to his wants, and crowding into the remainder of his life, the love they would have diffused over their whole existence, from infancy, if he — dear obdurate! — had but consented to receive the precious offering.

"And when I saw you," resumed Mr Pecksniff, with still greater deference, "in the little, unassuming village where we take the liberty of dwelling, I said you were mistaken in me, my dear sir; that was all, I think?"

"No — not all," said Martin, who had been sitting with his hand upon his brow for some time past, and now looked up again; "you said much more, which, added to other circumstances that have come to my knowledge, opened my eyes. You spoke to me, disinterestedly, on behalf of — I needn’t name him. You know whom I mean."

Trouble was expressed in Mr Pecksniff's visage, as he pressed his hot hands together, and replied, with humility, "Quite disinterestedly, sir, I assure you."

"I know it," said old Martin, in his quiet way. "I am sure of it. I said so. It was disinterested, too, in you, to draw that herd of harpies off from me, and be their victim yourself; most other men would have suffered them to display themselves in all their rapacity, and would have striven to rise, by contrast, in my estimation. You felt for me, and drew them off, for which I owe you many thanks. Although I left the place, I know what passed behind my back, you see!"

"You amaze me, sir!" cried Mr Pecksniff; which was true enough.

"My knowledge of your proceedings," said the old man, does not stop at this. You have a new inmate in your house."

"Yes, sir," rejoined the architect, "I have."

"He must quit it," said Martin. [Chapter X, "Containing strange matter; on which many events in this history may, for their good or evil influence, chiefly depend,"]

Michael Steig's Commentary (1978):

In both "M. Todgers and the Pecksniffs call upon Miss Pinch" (ch. 9) and "Truth prevails and Virtue is triumphant" (ch. 10), Browne captures Pecksniff's impenetrable complacency, and in the second he also makes what is to my eyes a curious external allusion: with his hand inside his waistcoat, Pecksniff strikes a Napoleonic pose. His particular stance here, the shape of his body and head, and the hat on the table, bear a remarkable resemblance to Louis Philippe's pose in a contemporary lithograph of the king and his family (See the illustration in Asa Briggs, p. 51). The posture of self-assumed kingliness may be enough to explain the similarity, but it seems possible that Phiz's basic conception of Pecksniff was influenced by graphic representation of the French king, both in portrait and in caricature. In particular, the famous pear shape of Louis Philippe's head, often caricatured with emphasis on the jowls at the bottom and the hair coming to a point at the top, resembles Pecksniff's head; and the various distortions to which Pecksniff's face is subjected recall Philipon's and Daumier's malicious fun with the Citizen-King's face. Apart from the obviously exaggerated expressions on the three Pecksniffs' faces as they crowd around old Martin, the only hint of an undercutting of their "virtue" is the vivified coal scuttle, which grins maliciously........

Commentaries often puzzle me because there is often no way to give you the rest of the commentary without giving away a very important part of the story, this is one of those times. Why they seem to think we all have read the book before we saw the illustrations is beyond me, but the rest of the commentary I'll save for later. And I am always very glad that I've already read each and every Dickens book before reading each and every commentary. Here is Louis Phillippe:

"We sometimes venture to consider her rather a fine figure, sir. Speaking as an artist, I may perhaps be permitted to suggest, that its outline is graceful and correct."

Chapter 10

Fred Barnard

Mr. Pecksniff unctuously extols the beauty of his younger daughter, Mercy, as he introduces Old Martin to his daughters.

Text Illustrated:

‘Poor girls!’ said Mr Pecksniff. ‘You will excuse their agitation, my dear sir. They are made up of feeling. A bad commodity to go through the world with, Mr Chuzzlewit! My youngest daughter is almost as much of a woman as my eldest, is she not, sir?’

‘Which is the youngest?’ asked the old man.

‘Mercy, by five years,’ said Mr Pecksniff. ‘We sometimes venture to consider her rather a fine figure, sir. Speaking as an artist, I may perhaps be permitted to suggest that its outline is graceful and correct. I am naturally,’ said Mr Pecksniff, drying his hands upon his handkerchief, and looking anxiously in his cousin’s face at almost every word, ‘proud, if I may use the expression, to have a daughter who is constructed on the best models.’

‘She seems to have a lively disposition,’ observed Martin.

‘Dear me!’ said Mr Pecksniff. ‘That is quite remarkable. You have defined her character, my dear sir, as correctly as if you had known her from her birth. She has a lively disposition. I assure you, my dear sir, that in our unpretending home her gaiety is delightful.’

‘No doubt,’ returned the old man.

‘Charity, upon the other hand,’ said Mr Pecksniff, ‘is remarkable for strong sense, and for rather a deep tone of sentiment, if the partiality of a father may be excused in saying so. A wonderful affection between them, my dear sir! Allow me to drink your health. Bless you!’

Old Martin Chuzzlewit

Ron Embleton

Commentary:

A charming book illustration for an edition of The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (commonly known as Martin Chuzzlewit), the novel by Charles Dickens. It was originally serialised between 1842 and 1844. It is an original pencil drawing by the artist, Ronald Sydney Embleton. Born in Limehouse, London in 1930, Embleton began drawing as a young boy, submitting a cartoon to the News of the World at the age of 9 and, at 12, winning a national poster competition.

In 1946 Embleton went to the South-East Essex Technical College and School of Art. There he had the incredible good fortune to be taught by David Bomberg, one of the greatest – though at that time sadly under-appreciated – British artists of the twentieth century.

At 17 he earned himself a place in a commercial studio but soon left to work freelance, drawing comic strips for many of the small publishers who sprang up shortly after the war.

He was soon drawing for the major publishers. His most fondly remembered strips include Strongbow the Mighty in Mickey Mouse Weekly, Wulf the Briton in Express Weekly, Wrath of the Gods in Boys' World, Tales of the Trigan Empire and Johnny Frog in Eagle and Stingray in TV Century 21.

Embleton also provided the illustrations that appeared in the title credits for the Captain Scarlet TV series, and dozens of paintings for prints and newspaper strips. A meticulous artist, his illustrations appeared in Look and Learn for many years, amongst them the historical series Roger’s Rangers.

During the late 1970s, Embleton was commissioned by This England magazine to draw what became a total of forty-three characters from Dickens and the Classics which were published quarterly throughout the 1980s. All these coloured illustrations in large A2 format are now in private ownership.

Oh, Wicked Wanda! was a British full-colour satirical and saucy adult comic strip, written by Frederic Mullally and drawn by Ron Embleton. The strip regularly appeared in Penthouse magazine from 1973 to 1980 and was followed by Embleton's equally saucy dark humoured Merry Widow strip, written by Penthouse founder Bob Guccione.

Less well known, however, was his equally energetic career as an oil painter. In fact, being a painter had been his life's ambition – his 'driving force', according to his daughter Gillian. It was only his remarkable success as an illustrator that in the end permanently diverted him from the painter's path.

Embleton died on 13 February 1988 at the relatively young age of 57 after a lifetime of truly prodigious artistic output of remarkable quality and astounding quantity. Following his sudden death aged only 57, his obituary in The Times described him as 'responsible for some of the finest full-colour adventure series in modern British comics ... a grand master of his art'.

Old Martin and Mr. Pecksniff

Chapter 10

Harold Copping

1924 Character Sketches from Dickens

Text Illustrated:

‘I very much regret,’ Martin resumed, looking steadily at him, and speaking in a slow and measured tone; ‘I very much regret that you and I held such a conversation together, as that which passed between us at our last meeting. I very much regret that I laid open to you what were then my thoughts of you, so freely as I did. The intentions that I bear towards you now are of another kind; deserted by all in whom I have ever trusted; hoodwinked and beset by all who should help and sustain me; I fly to you for refuge. I confide in you to be my ally; to attach yourself to me by ties of Interest and Expectation’—he laid great stress upon these words, though Mr Pecksniff particularly begged him not to mention it; ‘and to help me to visit the consequences of the very worst species of meanness, dissimulation, and subtlety, on the right heads.’

‘My noble sir!’ cried Mr Pecksniff, catching at his outstretched hand. ‘And you regret the having harboured unjust thoughts of me! you with those grey hairs!’

‘Regrets,’ said Martin, ‘are the natural property of grey hairs; and I enjoy, in common with all other men, at least my share of such inheritance. And so enough of that. I regret having been severed from you so long. If I had known you sooner, and sooner used you as you well deserve, I might have been a happier man.’

Mr Pecksniff looked up to the ceiling, and clasped his hands in rapture.

Commentary:

In one of his prefaces to Martin Chuzzlewit, Dickens declares that his main object was "to exhibit in a variety of aspects the commonest of all vices; to show how selfishness propagates itself; and to what a grim giant it may grow, from small beginnings." In the person of Pecksniff he created a character that has become a by-word for hypocrisy, whilst other characters, such as Sairey Gamp and old Martin Chuzzlewit, have taken their place in the gallery of immortals. On the reverse side, equally inimitable, are to be found Tom Pinch, Mark Tapley, Ruth Pinch, John Westlock, and scores of others. The selections made from the book represent these phases. Old Martin is introduced in the first excerpt, delightful Ruth Pinch and her brother in the next, whilst the immortal tea party of Sairey Gamp and Betsy Prig forms the third.

Thanks for the illustrations, Kim. They are great.

Thanks for the illustrations, Kim. They are great. I agree with Emma about Ruth Pinch, I really like her as well and hope she will continue to play in the story.

I did like the suggestion by someone that Mr. Martin is using Pecksniff in some way rather than being taken in by him, but I had not thought of that. I hope that Mr. Martin has the ability to see through the Pecksniffs' act. He certainly did not at the beginning of the book seem to be one easily taken in by others.

From "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:

The first number, which appeared in January 1843, had not been quite finished when he wrote to me on the 8th of December:

"The Chuzzlewit copy makes so much more than I supposed, that the number is nearly done. Thank God!"

Beginning so hurriedly as at last he did, altering his course at the opening and seeing little as yet of the main track of his design, perhaps no story was ever begun by him with stronger heart or confidence. Illness kept me to my rooms for some days, and he was so eager to try the effect of Pecksniff and Pinch that he came down with the ink hardly dry on the last slip to read the manuscript to me. Well did Sydney Smith, in writing to say how very much the number had pleased him, foresee the promise there was in those characters. "Pecksniff and his daughters, and Pinch, are admirable—quite first-rate painting, such as no one but yourself can execute!" And let me here at once remark that the notion of taking Pecksniff for a type of character was really the origin of the book; the design being to show, more or less by every person introduced, the number and variety of humours and vices that have their root in selfishness.

The first number, which appeared in January 1843, had not been quite finished when he wrote to me on the 8th of December:

"The Chuzzlewit copy makes so much more than I supposed, that the number is nearly done. Thank God!"

Beginning so hurriedly as at last he did, altering his course at the opening and seeing little as yet of the main track of his design, perhaps no story was ever begun by him with stronger heart or confidence. Illness kept me to my rooms for some days, and he was so eager to try the effect of Pecksniff and Pinch that he came down with the ink hardly dry on the last slip to read the manuscript to me. Well did Sydney Smith, in writing to say how very much the number had pleased him, foresee the promise there was in those characters. "Pecksniff and his daughters, and Pinch, are admirable—quite first-rate painting, such as no one but yourself can execute!" And let me here at once remark that the notion of taking Pecksniff for a type of character was really the origin of the book; the design being to show, more or less by every person introduced, the number and variety of humours and vices that have their root in selfishness.

Thank you, Peter, for what seems to be a thorough summary. As I mentioned re: chapter 9, I zoned out while listening this week, and barely recognized what actually penetrated from this week's recap. I'm in no position to offer any observations on the text of chapter 10, but don't Mercy and Charity look haughty in all of the illustrations! The mean girls of 1840s London.

Thank you, Peter, for what seems to be a thorough summary. As I mentioned re: chapter 9, I zoned out while listening this week, and barely recognized what actually penetrated from this week's recap. I'm in no position to offer any observations on the text of chapter 10, but don't Mercy and Charity look haughty in all of the illustrations! The mean girls of 1840s London.

Kim wrote: "

Kim wrote: "Truth prevails, and Virtue is triumphant

Chapter 10

Phiz

April 1843

Text Illustrated:

Nothing could exceed the astonishment of the two Miss Pecksniffs when they found a stranger with their d..."

He really does look like a Louis Phillippe! Thanks for the context.

Chapter 10

Chapter 10The young Pecksniffs act in unison like a choir.

Given the previous meeting between Old Martin and Pecksniff, I find this meeting to be incredible without sufficient explanation.

The Pecksniffs are hypocrites and experienced practitioners of the fine art of haughtiness. Maybe this is why Pecksniff stumbled that first time we met him. It's hard to see what's in front of you while reaching for new heights with your nose. His daily constitutionals must be fraught with unseen obstacles in his path.

So what's with Old Martin and Pecksniff? What does the Old Martin need of Pecksniff?

.

Peter wrote: "Old Chuzzlewit then tells Pecksniff that young Martin Chuzzlewit must leave Pecksniff for he has deceived Pecksniff."

Peter wrote: "Old Chuzzlewit then tells Pecksniff that young Martin Chuzzlewit must leave Pecksniff for he has deceived Pecksniff."How would Old Martin know that?

Regarding the last paragraphs . . . not superfluous.

Mr. Pecksniff's scolding Mrs. Todgers for caring about 18 shillings highlights his hypocrisy. She is trying to survive, and every shilling counts. Meanwhile Pecksniff asks Mrs. Todgers for a special rate for him and his daughters (previous chapter) which he won't even be paying. Old Martin will, and I'm sure Pecksniff will collect full rate from him.

Julie wrote: "Yes, please do imagine, Mr. Pecksniff, what it would take for a person to be willing to compromise their integrity for eighteen shillings. Desperation is what it would take. Mrs. Todgers is a hard worker who's barely able to stay afloat in her greasy, depressing, lightless little establishment: she needs every eighteen shillings she can scrape together. I know she's grasping and greedy herself (she'd marry Pecksniff given the chance), but I prefer her so much to the Nells and Mrs. Rudges with all their fine scruples. Mrs. Todgers is a survivor."

Julie,

That's exactly how I feel about Mrs. Todgers! It becomes clear in so many ways that the landlady has to use all her wits and diplomacy to make ends meet and to get a living out of letting rooms to those single gentlemen. She talks to the Miss Pecksniffs about all the efforts she goes through in order to keep her boarders satisfied with the establishment, and this shows that she has to fight for her economic survival day and night:

2‘The anxiety of that one item, my dears,’ said Mrs Todgers, ‘keeps the mind continually upon the stretch. There is no such passion in human nature, as the passion for gravy among commercial gentlemen. It’s nothing to say a joint won’t yield — a whole animal wouldn’t yield — the amount of gravy they expect each day at dinner. And what I have undergone in consequence,’ cried Mrs Todgers, raising her eyes and shaking her head, ‘no one would believe!’"

And then:

"‘You, my dears, having to deal with your pa’s pupils who can’t help themselves, are able to take your own way,’ said Mrs Todgers; ‘but in a commercial establishment, where any gentleman may say any Saturday evening, “Mrs Todgers, this day week we part, in consequence of the cheese,” it is not so easy to preserve a pleasant understanding. [...]'"

The difference between Mrs. Todgers's hypocrisy and Mr. Pecksniff's is that the first one isn't really hypocrisy born out of greed and moral falseness but a businesswoman's key skill to run her establishment, and to run it meagrely enough, as it seems.

All in all, the scenes at Todgers's reminded me of the Sketches, too, but I actually enjoyed them a lot, as well as I did Mr. Pecksniff's failure to ingratiate his unworty self upon Miss Pinch's employers. I would probably also not have been among those contemporary readers who got tired of reading Martin Chuzzlewit the way I got tired about reading of Little Nell.

Mr. Pecksniff's behaviour at Mrs. Todgers's shows him in a very uncanny light: Is it not downright detestable and revolting when he tries to press himself upon Mrs. Todgers, with unctuously amorous intentions, by referring to his dead wife, actually using her as a moral sanction of his lecherous desires?

"‘I’m afraid it is a vain and thoughtless world,’ said Mr Pecksniff, overflowing with despondency. ‘These young people about us. Oh! what sense have they of their responsibilities? None. Give me your other hand, Mrs Todgers.’

The lady hesitated, and said ‘she didn’t like.’

‘Has a voice from the grave no influence?’ said Mr Pecksniff, with, dismal tenderness. ‘This is irreligious! My dear creature.’

‘Hush!’ urged Mrs Todgers. ‘Really you mustn’t.’

‘It’s not me,’ said Mr Pecksniff. ‘Don’t suppose it’s me; it’s the voice; it’s her voice.’

Mrs Pecksniff deceased, must have had an unusually thick and husky voice for a lady, and rather a stuttering voice, and to say the truth somewhat of a drunken voice, if it had ever borne much resemblance to that in which Mr Pecksniff spoke just then. But perhaps this was delusion on his part."

This is really creepy and disgusting, and I would not trust Mr. Pecksniff with any defenseless woman placed into his house. There is great depravity in this man!

Julie,

That's exactly how I feel about Mrs. Todgers! It becomes clear in so many ways that the landlady has to use all her wits and diplomacy to make ends meet and to get a living out of letting rooms to those single gentlemen. She talks to the Miss Pecksniffs about all the efforts she goes through in order to keep her boarders satisfied with the establishment, and this shows that she has to fight for her economic survival day and night:

2‘The anxiety of that one item, my dears,’ said Mrs Todgers, ‘keeps the mind continually upon the stretch. There is no such passion in human nature, as the passion for gravy among commercial gentlemen. It’s nothing to say a joint won’t yield — a whole animal wouldn’t yield — the amount of gravy they expect each day at dinner. And what I have undergone in consequence,’ cried Mrs Todgers, raising her eyes and shaking her head, ‘no one would believe!’"

And then:

"‘You, my dears, having to deal with your pa’s pupils who can’t help themselves, are able to take your own way,’ said Mrs Todgers; ‘but in a commercial establishment, where any gentleman may say any Saturday evening, “Mrs Todgers, this day week we part, in consequence of the cheese,” it is not so easy to preserve a pleasant understanding. [...]'"

The difference between Mrs. Todgers's hypocrisy and Mr. Pecksniff's is that the first one isn't really hypocrisy born out of greed and moral falseness but a businesswoman's key skill to run her establishment, and to run it meagrely enough, as it seems.

All in all, the scenes at Todgers's reminded me of the Sketches, too, but I actually enjoyed them a lot, as well as I did Mr. Pecksniff's failure to ingratiate his unworty self upon Miss Pinch's employers. I would probably also not have been among those contemporary readers who got tired of reading Martin Chuzzlewit the way I got tired about reading of Little Nell.

Mr. Pecksniff's behaviour at Mrs. Todgers's shows him in a very uncanny light: Is it not downright detestable and revolting when he tries to press himself upon Mrs. Todgers, with unctuously amorous intentions, by referring to his dead wife, actually using her as a moral sanction of his lecherous desires?

"‘I’m afraid it is a vain and thoughtless world,’ said Mr Pecksniff, overflowing with despondency. ‘These young people about us. Oh! what sense have they of their responsibilities? None. Give me your other hand, Mrs Todgers.’

The lady hesitated, and said ‘she didn’t like.’

‘Has a voice from the grave no influence?’ said Mr Pecksniff, with, dismal tenderness. ‘This is irreligious! My dear creature.’

‘Hush!’ urged Mrs Todgers. ‘Really you mustn’t.’

‘It’s not me,’ said Mr Pecksniff. ‘Don’t suppose it’s me; it’s the voice; it’s her voice.’

Mrs Pecksniff deceased, must have had an unusually thick and husky voice for a lady, and rather a stuttering voice, and to say the truth somewhat of a drunken voice, if it had ever borne much resemblance to that in which Mr Pecksniff spoke just then. But perhaps this was delusion on his part."

This is really creepy and disgusting, and I would not trust Mr. Pecksniff with any defenseless woman placed into his house. There is great depravity in this man!

Kim wrote: "

Truth prevails, and Virtue is triumphant

Chapter 10

Phiz

April 1843

Text Illustrated:

Nothing could exceed the astonishment of the two Miss Pecksniffs when they found a stranger with their d..."

I just noticed how Charity's facial expression makes her the spitting image of her worthy father.

Truth prevails, and Virtue is triumphant

Chapter 10

Phiz

April 1843

Text Illustrated:

Nothing could exceed the astonishment of the two Miss Pecksniffs when they found a stranger with their d..."

I just noticed how Charity's facial expression makes her the spitting image of her worthy father.

Kim wrote: "

Truth prevails, and Virtue is triumphant

Chapter 10

Phiz

April 1843

Text Illustrated:

Nothing could exceed the astonishment of the two Miss Pecksniffs when they found a stranger with their d..."

Oh, Kim

I have just settled back into my Toronto life and come around to enjoying the illustrations. Thank you for them all, as always, but especially for the ones that link Pecksniff to Napoleon and Louis Philippe. In seems with each successive novel Phiz becomes more comfortable in his own style and relies less on what Dickens directs him to do. It could also be the case that Dickens simply gives Phiz more latitude to be creative. In any case, the quality, depth, and iconography of Phiz’s work is constantly improving.

Truth prevails, and Virtue is triumphant

Chapter 10

Phiz

April 1843

Text Illustrated:

Nothing could exceed the astonishment of the two Miss Pecksniffs when they found a stranger with their d..."

Oh, Kim

I have just settled back into my Toronto life and come around to enjoying the illustrations. Thank you for them all, as always, but especially for the ones that link Pecksniff to Napoleon and Louis Philippe. In seems with each successive novel Phiz becomes more comfortable in his own style and relies less on what Dickens directs him to do. It could also be the case that Dickens simply gives Phiz more latitude to be creative. In any case, the quality, depth, and iconography of Phiz’s work is constantly improving.

Kim wrote: "From "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:

The first number, which appeared in January 1843, had not been quite finished when he wrote to me on the 8th of December:

"The Chuzzlewit copy..."

Just imagine what it would be like to have Charles Dickens appear at your door when you are ill with the next chapters of his latest novel freshly completed and wanting to share it with you.

The first number, which appeared in January 1843, had not been quite finished when he wrote to me on the 8th of December:

"The Chuzzlewit copy..."

Just imagine what it would be like to have Charles Dickens appear at your door when you are ill with the next chapters of his latest novel freshly completed and wanting to share it with you.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 10

The young Pecksniffs act in unison like a choir.

Given the previous meeting between Old Martin and Pecksniff, I find this meeting to be incredible without sufficient explanation.

The..."

Xan

There must be something afoot with the new-found friendship of old Chuzzlewit and Pecksniff. What does Dickens have up his sleeve?

The young Pecksniffs act in unison like a choir.

Given the previous meeting between Old Martin and Pecksniff, I find this meeting to be incredible without sufficient explanation.

The..."

Xan

There must be something afoot with the new-found friendship of old Chuzzlewit and Pecksniff. What does Dickens have up his sleeve?

I'm wondering too Peter. And while I wonder about what Dickens has up his sleeve, I marvel at Young Bailey, a great example of how easily Dickens can sketch out a character that readers quickly become fond of? While residing at the Todger's I await impatiently Master Young Bailey's next antic.

I'm wondering too Peter. And while I wonder about what Dickens has up his sleeve, I marvel at Young Bailey, a great example of how easily Dickens can sketch out a character that readers quickly become fond of? While residing at the Todger's I await impatiently Master Young Bailey's next antic.

I'm enjoying MC -- all of it -- but the chapters annoy me. They are very much like run-on sentences. Is there such a thing as a run-on chapter? If so, I'm sure Dickens was its inventor. This could be organized better. Like false starts that have confused the ending with the beginning, every time I think Dickens is winding it up, I turn the page to another false ending.

I'm enjoying MC -- all of it -- but the chapters annoy me. They are very much like run-on sentences. Is there such a thing as a run-on chapter? If so, I'm sure Dickens was its inventor. This could be organized better. Like false starts that have confused the ending with the beginning, every time I think Dickens is winding it up, I turn the page to another false ending.

Pecksniff reminds me of a neighbor of my sister's. I guess he's still there she hasn't mentioned him in awhile. They aren't exactly the same but still remind me of each other and when Pecksniff is talking about his wife I was wondering if the same thing had happened to her as it did to my sister's neighbor. It seems they were very religious, religious enough to know that the rest of us were all going to burn in hell and he would take the time to tell you that whenever he could catch you. Everyone but him was such a sinner that they wouldn't even go to church they had their own service at their house. They had a bunch of kids because God would let them know when they should stop having them, something like that. I thought it was interesting that whenever the business my husband and son work at would have a customer appreciation day and have free food he and his family would show up and fill their pockets with hot dogs and cookies and anything else that would fit. Their kids names were Theology (called Theo), Christianity (Chris), (Obedience) ( don't know what he was called), Thankful, I guess just called thankful, and I can't remember the rest. My sister could here him screaming (as she called it) their daily prayers and sermons. Well one day his wife finished cooking the meal for the day, cleaned up the kitchen, sent the kids into the next room to do whatever they were allowed to do and walked out the door. After searching for her for hours and hours I can't remember how long, she was found on one of the country roads just walking, they brought her home and the next day she was gone again. When they found her she wouldn't speak to anyone and ended up in a mental hospital, she's still there as far as I know. Maybe she has Mrs. Pecksniff as a roommate.

Here are my favorite lines in the book so far:

‘Don’t be alarmed, Miss Pinch,’ said Mr Pecksniff, taking her hand condescendingly in one of his, and patting it with the other. ‘I have called to see you, in pursuance of a promise given to your brother, Thomas Pinch. My name—compose yourself, Miss Pinch—is Pecksniff.’

The good man emphasised these words as though he would have said, ‘You see in me, young person, the benefactor of your race; the patron of your house; the preserver of your brother, who is fed with manna daily from my table; and in right of whom there is a considerable balance in my favour at present standing in the books beyond the sky. But I have no pride, for I can afford to do without it!

‘Don’t be alarmed, Miss Pinch,’ said Mr Pecksniff, taking her hand condescendingly in one of his, and patting it with the other. ‘I have called to see you, in pursuance of a promise given to your brother, Thomas Pinch. My name—compose yourself, Miss Pinch—is Pecksniff.’

The good man emphasised these words as though he would have said, ‘You see in me, young person, the benefactor of your race; the patron of your house; the preserver of your brother, who is fed with manna daily from my table; and in right of whom there is a considerable balance in my favour at present standing in the books beyond the sky. But I have no pride, for I can afford to do without it!

Great idea, Kim. I think we should all post our favorite lines going forward. I know I will.

Great idea, Kim. I think we should all post our favorite lines going forward. I know I will.I remember those lines. Too funny. "Compose yourself." HaHaHa.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I'm wondering too Peter. And while I wonder about what Dickens has up his sleeve, I marvel at Young Bailey, a great example of how easily Dickens can sketch out a character that readers quickly bec..."

Yes, Young Bailey is one of my favourites in this novel, too!

Yes, Young Bailey is one of my favourites in this novel, too!

Kim wrote: "Here are my favorite lines in the book so far:

‘Don’t be alarmed, Miss Pinch,’ said Mr Pecksniff, taking her hand condescendingly in one of his, and patting it with the other. ‘I have called to se..."

"My name - compose yourself, Miss Pinch - is Pecksniff." - That's a side-splitter, really, isn't it? Imagine introducing yourself this way, and looking at people's faces ;-)

‘Don’t be alarmed, Miss Pinch,’ said Mr Pecksniff, taking her hand condescendingly in one of his, and patting it with the other. ‘I have called to se..."

"My name - compose yourself, Miss Pinch - is Pecksniff." - That's a side-splitter, really, isn't it? Imagine introducing yourself this way, and looking at people's faces ;-)

Kim wrote: "Pecksniff reminds me of a neighbor of my sister's. I guess he's still there she hasn't mentioned him in awhile. They aren't exactly the same but still remind me of each other and when Pecksniff is ..."

Wow, it's incredible that there really are people like that, but also a bit sad for the wife, who must have been suffering quite a lot in that household. As to the neighbour telling you that you'd all go to hell whereas he would go to heaven, you might reply, at least that was my first idea, that knowing he was not going to hell along with me, hell would definitely lose its sting, or at least become a lot more bearable.

Wow, it's incredible that there really are people like that, but also a bit sad for the wife, who must have been suffering quite a lot in that household. As to the neighbour telling you that you'd all go to hell whereas he would go to heaven, you might reply, at least that was my first idea, that knowing he was not going to hell along with me, hell would definitely lose its sting, or at least become a lot more bearable.

Kim wrote: "Their kids names were Theology (called Theo), Christianity (Chris), (Obedience) ( don't know what he was called)..."

Kim wrote: "Their kids names were Theology (called Theo), Christianity (Chris), (Obedience) ( don't know what he was called)..."Obie, of course!

I'm at a total loss for nicknaming Thankful, though.

Kim wrote: "Here are my favorite lines in the book so far:

Kim wrote: "Here are my favorite lines in the book so far:‘Don’t be alarmed, Miss Pinch,’ said Mr Pecksniff, taking her hand condescendingly in one of his, and patting it with the other. ‘I have called to se..."

That line is absolutely hilarious! Thank you, Kim, for reminding me of it. I have to confess that I'm having a somewhat hard time getting into MC, (and we're almost 200 pages in, at this point!) but lines like this really sustain me and keep me invested in the story. I do find the subtle humor in this novel to be really great, even if I'm not in love with the characters or themes. I haven't completely written off the book yet, but I feel like I'm waiting for it to really get to the meat of the story. I absolutely agree with Xan about the chapters. Something about the organization or length is off? I can't put my finger on it.

Peter wrote: “There must be something afoot with the new-found friendship of old Chuzzlewit and Pecksniff. What does Dickens have up his sleeve?“

Peter wrote: “There must be something afoot with the new-found friendship of old Chuzzlewit and Pecksniff. What does Dickens have up his sleeve?“I 100% agree, this has been playing on my mind the past few days-particularly given Pecksniffs use of the younger Martin. From what I recall of the earlier chapters Pinch had been made fully aware of who he was picking up, and had been told not to mention anything that had passed-presumably Pecksniffs plans for him lie beyond this initial offering of sacrifice we see in this chapter? And was it making the most of the situation when Martin junior applied-or did he seek out to tempt Martins application as part of his wider plan? I’m leaning towards the latter

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I'm enjoying MC -- all of it -- but the chapters annoy me. They are very much like run-on sentences. Is there such a thing as a run-on chapter? If so, I'm sure Dickens was its inventor. This could ..."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I'm enjoying MC -- all of it -- but the chapters annoy me. They are very much like run-on sentences. Is there such a thing as a run-on chapter? If so, I'm sure Dickens was its inventor. This could ..."I've just reread these chapters in an attempt to catch back up, and have to agree with you, Xan. It seems as if the chapters contain multiple settings and scenes, and could have been portioned up into shorter and more coherent chunks. Even though I'm enjoying the story, it seems much more tedious with these run-on chapters.

I have gained the impression that one instalment either consists of two overly long chapters or of one rather long chapter and two shortish ones. Why this is so, is beyond me!

Now what did Pecksniff really come to London for, I asked myself. Surely not just to meet Tom Pinch’s sister. Problem solved in the first sentence. Pecksniff is in “town on business.” What business? That question will be answered.

Whatever the business was his daughters felt he had “his purpose straight and full before him” although they had no knowledge of his real designs. All they know is that every morning he goes to the post office to see if he has received any letters. Then one day and old man comes to the post office, obtains directions to Todgers’s, and finds Pecksniff at his leisure reading a book and preparing to have some cake and wine. The old stranger turns out to be Martin Chuzzlewit senior. Problem solved. Pecksniff had come to London on Chuzzlewit’s request. Chuzzlewit says that he sought out Pecksniff for refuge, and to “confide in [Pecksniff] to be my ally;” with hopes that Pecksniff will join with Chuzzlewit. Chuzzlewit tells Pecksniff that “if I had known you sooner, and sooner used you well deserve, I might have been a happier man.” Pecksniff calls for his daughters, who had been listening at the door the entire time, and Charity and Mercy appear and embrace Old Chuzzlewit. Chuzzlewit thanks Pecksniff for drawing off the “herd of harpies” at the Blue Dragon and becoming their victim himself.”

Thoughts

These first few paragraphs are quite a shock and very revealing. For his part, Old Chuzzlewit seems contrite and thankful for Pecksniff’s help and support at the Blue Dragon. For his part, Pecksniff seems pleased, surprised, and curious about old Martin's words and praise. I think it fair to say that both men have an agenda. What do you think their agenda’s are? Is it possible that either man is totally contrite and sincere in this discussion?

Which man would you trust more if he was your neighbour (or relative)? Why?

Old Chuzzlewit then tells Pecksniff that young Martin Chuzzlewit must leave Pecksniff for he has deceived Pecksniff. Chuzzlewit stares at Mercy and then announces that young Martin “has made his matrimonial choice.” What! The daughters of Pecksniff have been in the presence of such a snake and deceiver as young Martin. Pecksniff says he will not rest until he has “purged my house of this pollution.” But there is more. It turns out that Mary, Old Martin’s assistant, is important to him and he wants Mary to be favourably regarded by Pecksniff and his daughters for his sake. Old Chuzzlewit then questions whether Pecksniff is prepared for the criticism and scorn he may receive from others as their pact becomes public knowledge. Pecksniff tells old Chuzzlewit that he “would bear anything whatever” for Chuzzlewit’s happiness and contentment.

We then learn that Chuzzlewit had made arrangements to pay for Pecksniff and his daughter’s stay in London, but he will not tell Pecksniff where he lives as he has “no fixed abode.” Chuzzlewit never wants to discuss what has occurred between them again.

Chuzzlewit then asks Pecksniff about Mercy and Charity, and seems to take an interest in Mercy. Chuzzlewit seems somewhat hypnotized by the Pecksniff’s and says “I Little thought ... but a month ago that I should be breaking bread and pouring wine with you. I drink to you.”

What do we make of all this? Well, I think the answer lies in a short phrase that Dickens slips into the narrative. He says that Pecksniff’s daughters “embraced [Chuzzlewit] with all their hearts - with all their arms at any rate.” After Chuzzlewit leaves the daughters rejoice and we are told Pecksniff gently reminded them not to yield to “such light emotions.”

A change in tone now appears at Todgers’s as the Pecksniff’s hear a sound of voices in dispute. The youngest gentleman at Todgers’s dislikes Jinkins. It appears the young gentleman is even willing to have a duel with Jinkins. It seems that Jinkins is in the habit of being domineering, demanding, and degrading towards the young gentleman. It appears that either Jinkins must go or the young gentleman must with the week. It is made very clear that Mrs Todgers will accept criticism of herself, her boarders, but she will never accept criticism of Todgers’s, the establishment. To the Pecksniff’s, MrsTodgers confesses she likes Jinkins more.

When Pecksniff asks how much she charges the young gentleman per week he is shocked and marvels at how much a “female of your understanding can so far demean herself as to wear a double face, even for an instant.” For the remainder of the chapter Pecksniff continues to criticize Mrs Todgers and says to her at one point “[t]o barter away that precious jewel, self-esteem, and cringe to any mortal creature - for eighteen shillings a week!” Well, isn’t that a hypocritical thing for Pecksniff to say, especially given what has occurred earlier in the chapter between himself and old Chuzzlewit?

Thoughts

To what degree were you surprised to learn that the main reason for Pecksniff’s trip to London was to meet with old Chuzzlewit?

In your mind, what exactly is it that old Chuzzlewit wants from Pecksniff? Does this further reveal anything about old Chuzzlewit’s character?

How does this chapter help further your understanding of Pecksniff?

Has your early opinion of young Martin Chuzzlewit changed because of the revelations in this chapter?

Reflections

These early chapters continue to introduce us to some of the novel’s major characters and takes us to Todgers’s. I find Pecksniff increasing unlikable, Mercy and Charity anything but what their names suggest, and I continue to puzzle about what to think about old Chuzzlewit. There must be some reason why Dickens has two characters by the name of Martin Chuzzlewit but I am still puzzled and intrigued by how Dickens will unwrap their full characters and function in the novel.

The last part of Chapter 10 found Mrs Todgers receiving a small lecture from Pecksniff. This section helped further reveal Pecksniff’s character but I wonder if it was really necessary for the development of plot. Were the last few paragraphs anything more than stuffing? I realize that Dickens is still setting up this novel but am getting a touch impatient for more action. I am hopeful that Tom Pinch will develop into an important character in the novel and confess I am already curious how Pecksniff and his daughters will meet their end ... surely they are destined for a fall don’t you think?