The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

MC, Chp. 21-23

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 22

It’s one of those chapters, you know. Back at the hotel, Martin soon becomes the centre of public attention, apparently because of his new status as a landowner in Eden, and his new popularity first shows itself in the form of letters arriving, begging him to deliver lections on things like the Tower of London or asking him for support in getting a Member of Parliament to pay the letter-writer’s expenses in travelling to and staying in England for a couple of months. Apart from that, his landlord, Captain Kedgick, has adjourned a meeting ot the Watertoasters in the bar of his house with the sole aim of allowing them to get to know Martin Chuzzlewit. Maybe, for Captain Kedgick, there was also another aim in the background as we find that he sells tickets at so-and-so many dollars for this occasion. The Captain informs Martin that he has no choice but to receive these guests for otherwise the Watertoast Gazette would “‘flay [him] like a wild cat.‘“ Upon his question why the townspeople have so much interest in him, whom they don’t know, the landlord does not give any definite answer – in fact, he doesn’t give any answer at all.

Martin’s first reception consists in his sitting in the middle of the state room and lots and lots and lots of people flocking in and gathering around him, shaking hands but hardly ever engaging into meaningful conversation with him. Although the Captain admonishes them to leave the room after their introduction to make room for the visitors in their wake – the Captain must have sold a lot of tickets – they pay no heed to this but stay where they are, the room thus becoming fuller and fuller. Some of these people even touch the back of Martin’s head, and two journalists have divided their task of observing him by one taking care of Martin’s upper half, the other of the lower. All in all, our protagonist gets the impression of being some kind of exhibit which paying visitors have the right to scrutinize in whatever way they want:

QUESTION

All in all, the description of this public reception does not move the action any forward and seems motivated by Dickens’s wish to accuse Americans of sensationalism and bad manners. Can it be based on experiences he made himself when visiting the U.S.? And is it a fair representation, considering that Dickens lived on the fame he and his books had won in England and in the U.S.? Is this not a bit like a celebrity complaining about a celebrity status without which they would be worse off financially and socially?

Later in the day, an elderly gentleman enters Martin’s room and leaves him with a bony and very talkative woman, who is Mrs. Hominy, the “Mother of the Modern Gracchi“, whom he is supposed to accompany on her journey to New Thermopylae, which is on the way to Eden. Mrs. Hominy talks a lot about the fine arts and culture, using a great number of expressions that make no sense to Martin, who, by the way, is very tired anyway. She seems rather shocked when at one point of the conversation he uses the phrase “the naked eye“, but that does not keep her from lecturing and pontificating.

The next morning, Martin and Mark load their equipment on board the ship that is going to take them to Eden, but there is some delay and so they all have to wait aboard, and this is the picture of the people that are travelling west:

Mark, seeing there is still some time before the steamer starts, runs back to Captain Kedgick’s house and asks him the question he has always wanted to be answered, namely why people were so very interested in Martin Chuzzlewit. The Captain tells him that people in the U.S. like excitement and that Martin provides them with a good quantity of it – because “‘nobody as goes to Eden ever comes back alive!‘“

In the light of this information Mark, when hailed by his partner Martin, as soon as he has made it back on the steamer – and high time it was because the ship is weighing anchor already – tells him that he has never been half so jolly as now.

QUESTIONS

What do you think of this chapter in general? What is its function?

Mrs. Hominy seems to be a character the author particularly dislikes, and as she does not fulfil any function with regard to the plot, the author must have wanted some other point by introducing her. What point could it have been?

The sketch the narrator draws of the settlers is anything but heroic. How might contemporary American readers have reacted to it?

It’s one of those chapters, you know. Back at the hotel, Martin soon becomes the centre of public attention, apparently because of his new status as a landowner in Eden, and his new popularity first shows itself in the form of letters arriving, begging him to deliver lections on things like the Tower of London or asking him for support in getting a Member of Parliament to pay the letter-writer’s expenses in travelling to and staying in England for a couple of months. Apart from that, his landlord, Captain Kedgick, has adjourned a meeting ot the Watertoasters in the bar of his house with the sole aim of allowing them to get to know Martin Chuzzlewit. Maybe, for Captain Kedgick, there was also another aim in the background as we find that he sells tickets at so-and-so many dollars for this occasion. The Captain informs Martin that he has no choice but to receive these guests for otherwise the Watertoast Gazette would “‘flay [him] like a wild cat.‘“ Upon his question why the townspeople have so much interest in him, whom they don’t know, the landlord does not give any definite answer – in fact, he doesn’t give any answer at all.

Martin’s first reception consists in his sitting in the middle of the state room and lots and lots and lots of people flocking in and gathering around him, shaking hands but hardly ever engaging into meaningful conversation with him. Although the Captain admonishes them to leave the room after their introduction to make room for the visitors in their wake – the Captain must have sold a lot of tickets – they pay no heed to this but stay where they are, the room thus becoming fuller and fuller. Some of these people even touch the back of Martin’s head, and two journalists have divided their task of observing him by one taking care of Martin’s upper half, the other of the lower. All in all, our protagonist gets the impression of being some kind of exhibit which paying visitors have the right to scrutinize in whatever way they want:

“If they spoke to him, which was not often, they invariably asked the same questions, in the same tone; with no more remorse, or delicacy, or consideration, than if he had been a figure of stone, purchased and paid for, and set up there for their delight.“

QUESTION

All in all, the description of this public reception does not move the action any forward and seems motivated by Dickens’s wish to accuse Americans of sensationalism and bad manners. Can it be based on experiences he made himself when visiting the U.S.? And is it a fair representation, considering that Dickens lived on the fame he and his books had won in England and in the U.S.? Is this not a bit like a celebrity complaining about a celebrity status without which they would be worse off financially and socially?

Later in the day, an elderly gentleman enters Martin’s room and leaves him with a bony and very talkative woman, who is Mrs. Hominy, the “Mother of the Modern Gracchi“, whom he is supposed to accompany on her journey to New Thermopylae, which is on the way to Eden. Mrs. Hominy talks a lot about the fine arts and culture, using a great number of expressions that make no sense to Martin, who, by the way, is very tired anyway. She seems rather shocked when at one point of the conversation he uses the phrase “the naked eye“, but that does not keep her from lecturing and pontificating.

The next morning, Martin and Mark load their equipment on board the ship that is going to take them to Eden, but there is some delay and so they all have to wait aboard, and this is the picture of the people that are travelling west:

“There they were, all huddled together with the engine and the fires. Farmers who had never seen a plough; woodmen who had never used an axe; builders who couldn’t make a box; cast out of their own land, with not a hand to aid them: newly come into an unknown world, children in helplessness, but men in wants — with younger children at their backs, to live or die as it might happen!“

Mark, seeing there is still some time before the steamer starts, runs back to Captain Kedgick’s house and asks him the question he has always wanted to be answered, namely why people were so very interested in Martin Chuzzlewit. The Captain tells him that people in the U.S. like excitement and that Martin provides them with a good quantity of it – because “‘nobody as goes to Eden ever comes back alive!‘“

In the light of this information Mark, when hailed by his partner Martin, as soon as he has made it back on the steamer – and high time it was because the ship is weighing anchor already – tells him that he has never been half so jolly as now.

QUESTIONS

What do you think of this chapter in general? What is its function?

Mrs. Hominy seems to be a character the author particularly dislikes, and as she does not fulfil any function with regard to the plot, the author must have wanted some other point by introducing her. What point could it have been?

The sketch the narrator draws of the settlers is anything but heroic. How might contemporary American readers have reacted to it?

Chapter 23

Martin and Mark are nearing their journey’s end, and finally we, the readers, are invited to a glimpse of Eden. Of the one Zephaniah Scadder stands for, that is. The first signs of evil become visible to Martin when they arrive at New Thermopylae, which is just a puny collection of roughly-built shacks with nothing much to boast of, and when Mrs. Hominy, disembarking, says that ”’[…] work it which way you will, it whips Eden’”. Martin now seems to realize that he is not necessarily heading towards wealth and architectural fame and that maybe, it was a bit rash to trust Mr. Scadder, although he still flies off the handle when Mark mentions New Thermopylae and Eden in one and the same breath. The nearer they come Eden, the emptier the boat becomes and it is resembling more and more ”old Charon’s boat” save for the mealtimes when – the narrator never tires of mentioning it – the citizens of the Republic devour their victuals with speed and determination. Nevertheless, the landscape is becoming more and more grim and hopeless:

QUESTIONS

Once again, Dickens uses the appearance of places, this time of landscape, to prepare his readers for a certain plot element, and interestingly, the change of scenery also corresponds with Martin’s change of mood. Do you think it is the landscape that effects the mood, or are there other things at work within Martin?

When they arrive at Eden, they find it even more dreary and God-forsaken than New Thermopylae, and they learn that most of its inhabitants have long left this place and that only those stayed behind who lacked the means or the health – the ague is a frequent visitor to the settlers living in this swampy and insalubrious place – to go away. Some very emaciated men help Martin and Mark find the place they have become owners of, a place which is bare of furniture and does not even have a proper door, and there, Martin soon falls prey to despondency and inactivity, because he finds that all his hopes and expectations are crushed. Mark, however, who must have been prepared for this outcome in some measure by Captain Kedgwick’s insinuations, does not show any signs of depression or resignation but he bears up, looking after their provisions and making sure that they get a new door, for instance, and he even starts clearing away an ugly old tree from their plot of land. He might be doing this with a view of cheering Martin up, but he also tells himself that he now has a first-class opportunity of showing a jolly disposition in the face of adversity.

QUESTIONS

What could Mark’s motives for being so optimistic be? Obviously, there is hardly any sense in chopping away at the trees and improving the hut by adding a door – apart, of course, with a view to keeping the damp and fever-inducing air outside.

What can be said about Martin’s development. At first, he is moody and peevish when they are at New Thermopylae, but when they come to Eden, he even apologizes to Mark for having put him (and his savings) into such a situation as that. Will misery succeed in making Martin a less egocentric person?

Martin and Mark are nearing their journey’s end, and finally we, the readers, are invited to a glimpse of Eden. Of the one Zephaniah Scadder stands for, that is. The first signs of evil become visible to Martin when they arrive at New Thermopylae, which is just a puny collection of roughly-built shacks with nothing much to boast of, and when Mrs. Hominy, disembarking, says that ”’[…] work it which way you will, it whips Eden’”. Martin now seems to realize that he is not necessarily heading towards wealth and architectural fame and that maybe, it was a bit rash to trust Mr. Scadder, although he still flies off the handle when Mark mentions New Thermopylae and Eden in one and the same breath. The nearer they come Eden, the emptier the boat becomes and it is resembling more and more ”old Charon’s boat” save for the mealtimes when – the narrator never tires of mentioning it – the citizens of the Republic devour their victuals with speed and determination. Nevertheless, the landscape is becoming more and more grim and hopeless:

”As they proceeded further on their track, and came more and more towards their journey’s end, the monotonous desolation of the scene increased to that degree, that for any redeeming feature it presented to their eyes, they might have entered, in the body, on the grim domains of Giant Despair. A flat morass, bestrewn with fallen timber; a marsh on which the good growth of the earth seemed to have been wrecked and cast away, that from its decomposing ashes vile and ugly things might rise; where the very trees took the aspect of huge weeds, begotten of the slime from which they sprung, by the hot sun that burnt them up; where fatal maladies, seeking whom they might infect, came forth at night in misty shapes, and creeping out upon the water, hunted them like spectres until day; where even the blessed sun, shining down on festering elements of corruption and disease, became a horror; this was the realm of Hope through which they moved.”

QUESTIONS

Once again, Dickens uses the appearance of places, this time of landscape, to prepare his readers for a certain plot element, and interestingly, the change of scenery also corresponds with Martin’s change of mood. Do you think it is the landscape that effects the mood, or are there other things at work within Martin?

When they arrive at Eden, they find it even more dreary and God-forsaken than New Thermopylae, and they learn that most of its inhabitants have long left this place and that only those stayed behind who lacked the means or the health – the ague is a frequent visitor to the settlers living in this swampy and insalubrious place – to go away. Some very emaciated men help Martin and Mark find the place they have become owners of, a place which is bare of furniture and does not even have a proper door, and there, Martin soon falls prey to despondency and inactivity, because he finds that all his hopes and expectations are crushed. Mark, however, who must have been prepared for this outcome in some measure by Captain Kedgwick’s insinuations, does not show any signs of depression or resignation but he bears up, looking after their provisions and making sure that they get a new door, for instance, and he even starts clearing away an ugly old tree from their plot of land. He might be doing this with a view of cheering Martin up, but he also tells himself that he now has a first-class opportunity of showing a jolly disposition in the face of adversity.

QUESTIONS

What could Mark’s motives for being so optimistic be? Obviously, there is hardly any sense in chopping away at the trees and improving the hut by adding a door – apart, of course, with a view to keeping the damp and fever-inducing air outside.

What can be said about Martin’s development. At first, he is moody and peevish when they are at New Thermopylae, but when they come to Eden, he even apologizes to Mark for having put him (and his savings) into such a situation as that. Will misery succeed in making Martin a less egocentric person?

Chapter 21

Chapter 21Tristram wrote: "Mark cannot help telling his friend that an army officer told him about the abundance of snakes in that place Eden, and that he should be careful when he is going to bed."

I love the double meaning of snakes in Eden.

-- Queen Victoria lives at the mint. Hahahaha Good one, Mark.

-- The general to Scadder: "These are my particular friends." This sounds like a practiced con to me. Tomorrow Eden won't be there.

Yes, I liked how Mark was all sarcastic with those people! Only Scadder seemed to realize what he did in the end, and he turned it around and used it on Martin. I really do not understand why Mark goes into this willingly, with his eyes open. It even made me a bit angry during those chapters, I noticed. Would the urge to find dreariness to be jolly in really be so big, that he also willingly lets Martin go down with him to find it? I mean, Mark obviously cannot stand the scammers, and couldn't let himself be scammed by them if he had been alone, he could only achieve his so sought after hell by throwing someone else under the bus. Even as unlikeable as Martin is, and as likeable as Mark usually is, I think that's what makes me a bit upset about the situation. Mark probably knows by now that Martin is a product of his upbringing, just as much as Jonas is, and is still wired towards the whole social being so polite you have to go with certain schemes. It is exactly why the scammers bait him. Mark is willing to let this happen for ... something vague to me. Because of his wanting to prove himself. I ... Grrr, I could bite him!

Jantine,

Jantine,I wonder if Mark is testing himself. He has previously said the true test of jollity is to be Jolly when things are not going well. I'm wondering if he knows he and Martin are being conned and is letting it happen so he can be tested. He'll be broke in a different country, 3 or 4 thousand miles from home, with an ocean between him and home, and he'll have Martin to take care of. Will he be jolly? Is so, success.

Tristram wrote: "the Captain must have sold a lot of tickets – they pay no heed to this but stay where they are, the room thus becoming fuller and fuller."

Tristram wrote: "the Captain must have sold a lot of tickets – they pay no heed to this but stay where they are, the room thus becoming fuller and fuller."This reminds me of the Marx Brothers's movie, Monkey Business, I think. On a transatlantic voyage their cabin is crammed with people who have come to see the brothers for various reasons. They make use of the bedlam to escape. I love that scene. (I'm a huge Marx Borthers fan.)

As to the why of this chapter, there are probably two reasons. One is simply filler, which I can see the need for given that you have to publish a certain number of words or pages each month. I suspect Dickens had at his ready all sorts of vignettes he could stuff in a chapter when the need arose.

The other is probably Dickens making fun of Americans. I have no problem with this. He does it to his own country, institutions and people, and I enjoy it, so I'm going to enjoy it here too. And we all know there is (exaggerated) truth in his satire.

So no one returns alive from Eden? Makes it sound like Tombstone or Dodge City. How far west is this Eden? Is Dickens going to make fun of mythical westerns that were so much favored by Eastern publications. I hope so. Or is it a tad bit early for the Western?

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Jantine,

I wonder if Mark is testing himself. He has previously said the true test of jollity is to be Jolly when things are not going well. I'm wondering if he knows he and Martin are being conne..."

That's what I was implying, and thought he was doing. And it's what makes me like him a bit less. Like I said, it looks like he's using Martin as leverage to create his test, instead of helping him staying out of this kind of trouble.

I wonder if Mark is testing himself. He has previously said the true test of jollity is to be Jolly when things are not going well. I'm wondering if he knows he and Martin are being conne..."

That's what I was implying, and thought he was doing. And it's what makes me like him a bit less. Like I said, it looks like he's using Martin as leverage to create his test, instead of helping him staying out of this kind of trouble.

Me too. But still, it felt a bit like he was enabling Martin's destructive behavior. Especially since Martin couldn't have not listened in the practical sense, since it was Mark's money that was thrown into the pit to begin with. It's Mark who buys the piece of land in Eden, even when it's Martin who signs.

Yes, Mark's money. Until that happened I was wondering just how far 20 pounds could go. A transatlantic voyage for two, a train ride, hotels, dinners, and the purchase of property, I had thought. I was about to call it the mythical, magical 20 pounds. The more you spend of it, the more there is of it. But if it is almost all Mark's money, then it is mostly Mark who will suffer the financial loss if the property fails, and not Martin. But i don't always understand Mark. He's a strange bird to me.

Yes, Mark's money. Until that happened I was wondering just how far 20 pounds could go. A transatlantic voyage for two, a train ride, hotels, dinners, and the purchase of property, I had thought. I was about to call it the mythical, magical 20 pounds. The more you spend of it, the more there is of it. But if it is almost all Mark's money, then it is mostly Mark who will suffer the financial loss if the property fails, and not Martin. But i don't always understand Mark. He's a strange bird to me. To me this is a hero's quest. Martin needs to experience a few hard knocks in life, earn a few bruises, if he is ever to lose his unearned self-infatuation. Mark must return reborn into someone Mary deserves. And perhaps Mark is there to make sure Martin earns his bruises without dying. I say this because it's looking like Martin is the best bet for hero up to this point. And someone has to win Mary.

But I'm just ranting. Don't mind me. I like your thoughts on this, Jantine. Let's see what Mark is up too. I have a feeling his mind is always up to something.

Tristram wrote: "The two Americans are so knowledgeable that they even correct Martin on his notions as to where the Queen resides and what English expressions are known in the old country or not, because they have been to England quite often … in print, which is just as good as in real. – I wonder if Dickens ever met lots of people in America who claimed this kind of superior knowledge or whether he just made that up..."

Tristram wrote: "The two Americans are so knowledgeable that they even correct Martin on his notions as to where the Queen resides and what English expressions are known in the old country or not, because they have been to England quite often … in print, which is just as good as in real. – I wonder if Dickens ever met lots of people in America who claimed this kind of superior knowledge or whether he just made that up..."I can't speak to Dickens, but I know I had the pleasure of traveling as an American in Spain about three weeks after the Oliver Stone movie JFK was released there, and I lost track of the number of Spanish people who made it their business to inform me that Kennedy's assassination was a cover-up (which was of course the plot of the movie).

Tristram wrote: "This left me asking myself if Americans were really so averse to Abolitionists at that time, or whether Dickens was exaggerating for the sake of satire here..."

Tristram wrote: "This left me asking myself if Americans were really so averse to Abolitionists at that time, or whether Dickens was exaggerating for the sake of satire here..."I've done some research on this one in the past, so short answer: he isn't exaggerating all that much, particularly when it came to Irish Americans.

Longer answer: Noel Ignatiev (who died earlier this month) made a good case in his book How the Irish Became White that Irish Americans lifted themselves socially partly by aligning themselves with white people against black people, and as a result putting to rest an earlier social distinction between Protestants and Catholics that kept the Irish, mostly Catholics, down. He documents that Irish American organizations split with O'Connell on the question of slavery, and were angry with O'Connell for in effect making Irish people seem less "white" by aligning them politically with enslaved blacks in the cause of abolition.

Jantine wrote: "I really do not understand why Mark goes into this willingly, with his eyes open. It even made me a bit angry during those chapters, I noticed. Would the urge to find dreariness to be jolly in really be so big, that he also willingly lets Martin go down with him to find it?"

Jantine wrote: "I really do not understand why Mark goes into this willingly, with his eyes open. It even made me a bit angry during those chapters, I noticed. Would the urge to find dreariness to be jolly in really be so big, that he also willingly lets Martin go down with him to find it?"I don't really think of Mark as a character so much anymore--more as a concept and a Greek chorus. But an entertaining one. I'm glad he's there.

Xan wrote "To me this is a hero's quest. Martin needs to experience a few hard knocks in life, earn a few bruises, if he is ever to lose his unearned self-infatuation. Mark must return reborn into someone Mary deserves. And perhaps Mark is there to make sure Martin earns his bruises without dying. I say this because it's looking like Martin is the best bet for hero up to this point. And someone has to win Mary."

Exactly. Mark's not in it for himself or his own purposes. He's Martin's commentator and guardian angel--and his job is also to give the reader someone to identify with, which we are pretty short on in these chapters I think.

I am wondering whether Mark would really have stood a chance of making Martin desist from buying himself into the Eden project, no matter whose money was used. We have seen how full Martin is of himself and how much expertise he gives himself credit for. How likely is it he would have listened to Mark's cautions - cautions, by the way, which Mark voiced as ironical asides in the conversation with Scadder. Had Mark demanded his money back and thus dissolved the partnership, I think that Martin would have taken such a step very ill and broken off any contact with Mark at all. Therefore, humouring Martin can also be seen as a way for Mark to accompany him and make sure he does not get himself into even worse scrapes. That's how I interpreted Mark's behaviour and the motives for it.

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "This left me asking myself if Americans were really so averse to Abolitionists at that time, or whether Dickens was exaggerating for the sake of satire here..."

I've done some res..."

An interesting observation, Julie! And an example of how identity politics can be used to keep different groups of people apart from each other in order to exploit one (or maybe even both) of them.

I've done some res..."

An interesting observation, Julie! And an example of how identity politics can be used to keep different groups of people apart from each other in order to exploit one (or maybe even both) of them.

Chapter 23

Chapter 23Paraphrasing "The trees look like large weeds." What a great way to describe certain places in the southwest, the trees are so distressed. But is it the southwest? I don't believe it's been mentioned where they are, state or region?

A walking stick seems to be a popular dress accessory in the U.K. and U.S.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "the Captain must have sold a lot of tickets – they pay no heed to this but stay where they are, the room thus becoming fuller and fuller."

This reminds me of the Marx Brothers's m..."

Xan

I agree with you that since Dickens does make fun of a British institutions, social classes, and individual people in every novel Americans should not be overly offended by the sections in MC that are set there.

I have not read American Notes in decades, but increasingly feel I should just to orientate myself better.

With the location of Martin Chuzzlewit’s new venture being called Eden and the warning about the snakes found in Eden there should be little surprise for the reader once he and Mark arrive. No spoilers, but in future chapters set in England it might be an idea to be on the lookout for snakes as well.

Like yourself and Julie, I also see much of the hero’s quest in this novel. The hero-sidekick is a recurring trope and has many methods of expression.

This reminds me of the Marx Brothers's m..."

Xan

I agree with you that since Dickens does make fun of a British institutions, social classes, and individual people in every novel Americans should not be overly offended by the sections in MC that are set there.

I have not read American Notes in decades, but increasingly feel I should just to orientate myself better.

With the location of Martin Chuzzlewit’s new venture being called Eden and the warning about the snakes found in Eden there should be little surprise for the reader once he and Mark arrive. No spoilers, but in future chapters set in England it might be an idea to be on the lookout for snakes as well.

Like yourself and Julie, I also see much of the hero’s quest in this novel. The hero-sidekick is a recurring trope and has many methods of expression.

I don't have much to add about these chapters that has not been said. It was so obvious from the way Eden was "sold" to Martin and the comment to Mark about no one returning alive what they would find there. As to why Martin was that gullible or Mark so agreeable to go on, I have few ideas.

I don't have much to add about these chapters that has not been said. It was so obvious from the way Eden was "sold" to Martin and the comment to Mark about no one returning alive what they would find there. As to why Martin was that gullible or Mark so agreeable to go on, I have few ideas. As to chapter 22 and the people that flocked to see Martin, I do see that as the way Dickens may have felt in America. I thought that was a good observation Tristram that he was in a way complaining about his own celebrity status.

"I was merely remarking, gentlemen — though it's a point of very little import — that the Queen of England does not happen to live in the Tower of London."

Chapter 21

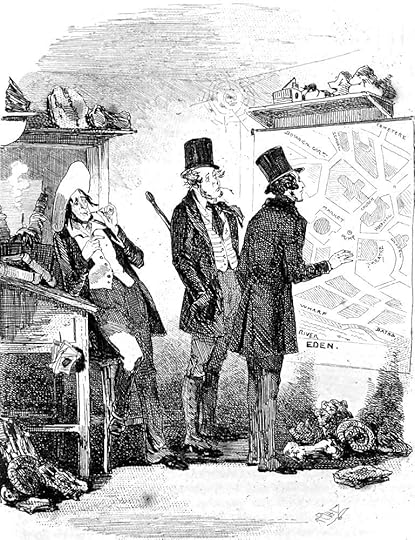

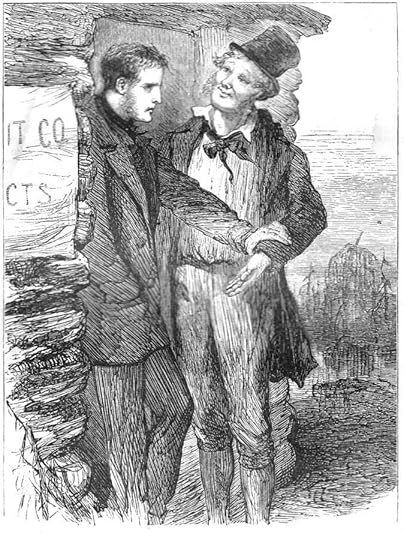

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Kettle bowed.

"In the name of this company, sir, and in the name of our common country, and in the name of that righteous cause of holy sympathy in which we are engaged, I thank you. I thank you, sir, in the name of the Watertoast Sympathisers; and I thank you, sir, in the name of the Watertoast Gazette; and I thank you, sir, in the name of the starspangled banner of the Great United States, for your eloquent and categorical exposition. And if, sir," said the speaker, poking Martin with the handle of his umbrella to bespeak his attention, for he was listening to a whisper from Mark; "if, sir, in such a place, and at such a time, I might venture to con-clude with a sentiment, glancing — however slantin'dicularly — at the subject in hand, I would say, sir may the British Lion have his talons eradicated by the noble bill of the American Eagle, and be taught to play upon the Irish Harp and the Scotch Fiddle that music which is breathed in every empty shell that lies upon the shores of green Co-lumbia!"

Here the lank gentleman sat down again, amidst a great sensation; and every one looked very grave.

"General Choke," said Mr. La Fayette Kettle, "you warm my heart; sir, you warm my heart. But the British Lion is not unrepresented here, sir; and I should be glad to hear his answer to those remarks."

"Upon my word," cried Martin, laughing, "since you do me the honour to consider me his representative, I have only to say that I never heard of Queen Victoria reading the What's-his-name Gazette and that I should scarcely think it probable."

General Choke smiled upon the rest, and said, in patient and benignant explanation:

"It is sent to her, sir. It is sent to her. Per mail."

But if it is addressed to the Tower of London, it would hardly come to hand, I fear," returned Martin, "for she don't live there."

"The Queen of England, gentlemen," observed Mr. Tapley, affecting the greatest politeness, and regarding them with an immovable face, "usually lives in the Mint to take care of the money. She has lodgings, in virtue of her office, with the Lord Mayor at the Mansion House; but don't often occupy them, in consequence of the parlour chimney smoking."

Commentary:

The scene on the railway car as Martin and Mark make their way to the absurdly-named Eden on the banks of the Mississippi (which becomes in Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in 1886 the town of Cairo, a possible destination for the runaways that constitutes freedom from slavery) sets up the satire on American "learned" and patriotic societies of amateurs such as the Watertoast Association of United Sympathisers, Anglophobic and pro-Irish (as the reference to the Irish Harp would suggest).

While several travellers sleep on the hard, wooden seats with their feet indecorously displayed (left), Barnard's American gentlemen crowd around Martin (top-hat) and Mark (soft hat) to query the young Englishmen about Queen Victoria's residences. Barnard makes Martin look perfectly serious in stylish topcoat, while Mark has a bemused smile that communicates the artist's attitude towards his material. Refreshingly, Americans in these episodes feel no reticence in engaging perfect strangers in conversation if they are seeking information about foreign places and persons. Here, however, Dickens makes them thoroughly gullible as he has Mark pass off spurious observations about the Mint and Mansion House, much to the delight of contemporary English readers.

The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared on Paper

Chapter 21

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Scadder was so satisfied by this explanation, that he shook the General warmly by the hand, and got out of the rocking-chair to do it. He then invited the General’s particular friends to accompany him into the office. As to the General, he observed, with his usual benevolence, that being one of the company, he wouldn’t interfere in the transaction on any account; so he appropriated the rocking-chair to himself, and looked at the prospect, like a good Samaritan waiting for a traveller.

"Heyday!" cried Martin, as his eye rested on a great plan which occupied one whole side of the office. Indeed, the office had little else in it, but some geological and botanical specimens, one or two rusty ledgers, a homely desk, and a stool. "Heyday! what’s that?"

"That’s Eden," said Scadder, picking his teeth with a sort of young bayonet that flew out of his knife when he touched a spring.

"Why, I had no idea it was a city."

"Hadn’t you? Oh, it’s a city."

“A flourishing ciy, too! An architectural city! There were banks, churches, cathedrals, market-places, factories, hotels, stores, mansions, wharves; an exchange, a theatre; public buildings of all kinds, down to the office of the Eden Stinger, a daily journal; all faithfully depicted in the view before them.

“Dear me! It’s really a most important place!" cried Martin turning round.

“Oh! it’s very important," observed the agent.

“But, I am afraid," said Martin, glancing again at the Public Buildings, "that there’s nothing left for me to do."

“Well! it ain’t all built," replied the agent. "Not quite."

Commentary: The Trouble with Eden:

The ninth number's companion pieces, both captioned in parallel and contrast by Dickens himself rather than by the illustrator, "The thriving City of Eden as it appeared on paper" and "The thriving City of Eden as it appeared in fact", invite readers to compare Martin's response to the concept of the model town versus its actuality. The ideal in Martin's mind is a place on the American frontier where, even as an untried architect, he can make his fortune and then return to England to claim the hand of Mary Graham. Whereas in the former scene, Mark is aloof and disinterested, in the latter he is actively engaged in the "jolly" labour of subduing the wilderness — and of cheering up a dejected companion. Whereas Martin is entranced by the town plan and delighted to learn from Scadder that the new metropolis contains not a single architect, in the latter he seems to have abandoned all hope, and to be contemplating (like one of the toads that Phiz has supplied) jumping into the murky river's waters. The careful viewer will notice some telling details about the real estate office: the torn plaster, a mouse, and "the spider web where trapped flies suggest the fate of the naïve buyers". Although Phiz has been unable to convey a sense of the land-office's tiny dimensions, he has realized well the land-agent himself. Dickens's letter of 15-18 August 1843 may have specified the rocking chair and the spring-loaded knife with steel toothpick; however, since these details do not appear in the finished illustration, it is just as likely that they were after-thoughts which Dickens incorporated in the letterpress. The second part of this letter, however, dealing with the ninth installment's second subject, indicates clearly which aspects of the composition are Boz's and which Phiz's. Since Dickens had actually visited Cairo, Illinois, on the Mississippi, he must have had some very specific notions as to how Phiz was to depict the dismal swamp of Eden. Ironically, Dickens was not aware of how quickly America was developing, and so completely underestimated the potential of the townsite: as critic R. C. Churchill remarked in the Birmingham Post, "Thee would have been plenty of work for Chuzzlewit & Co., Architects, if only they had stuck it out".

In the pages of Martin Chuzzlewit Dickens created four memorable characters: the hypocritical Seth Pecksniff, the virtuous and self-effacing Tom Pinch; the self-serving mid-wife, Sairey Gamp; and the inveterately optimistic Mark Tapley. Each episode and each illustration advances our understanding and appreciation of at least one of these brilliant comic creations. And, as the program of illustration makes clear, Phiz thoroughly enjoyed depicting the adventures and misadventures of these characters. However, he was not entirely at liberty to create these memorable illustrations as Dickens issued nuanced instructions about poses and situations in highly precise terms. After reading Dickens's verbal design for The thriving City of Eden as it appeared in fact, Phiz sardonically replied, "I can't get all the perspective in — unless you allow of a long subject — something less than a mile" (cited in Buchanan-Brown). The plates serve as more than visual adjuncts to the letterpress in the ninth monthly number; rather, they are companion pieces, so that, for example, an optimistic and self-confident Martin dreams of lucrative contracts as he studies to townsite plan in Scadder's office, whereas Mark views the whole operation with healthy skepticism. In the next illustration, they entirely exchange perspectives, so that Martin, ill and dejected, sees their situation as hopeless, whereas Mark throws himself into the business of taming the wilderness. Michael Steig has pointed out how Phiz embeds significant details in these designs in order to comment parenthetically on his materials: "The empty spider web in the Journal office [in Jefferson Brick proposes a toast] becomes a web full of flies next to a mousetrap about to snare a victim' (Steig, Ch. 3). Above the architectural map of Eden as it might be Phiz has placed duck decoys and a toy guillotine as warnings to the unwary about the Eden Land Corporation as a confidence scheme. As he casually studies both young Englishmen, Scadder picks his teeth, as if preparing to devour his next victim.

Here is Phiz's first drawing for this chapter:

The thriving city of Eden, as it appeared on paper

Phiz

1843

Preparatory drawing

Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit

The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

The thriving city of Eden, as it appeared on paper

Phiz

1843

Preparatory drawing

Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit

The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

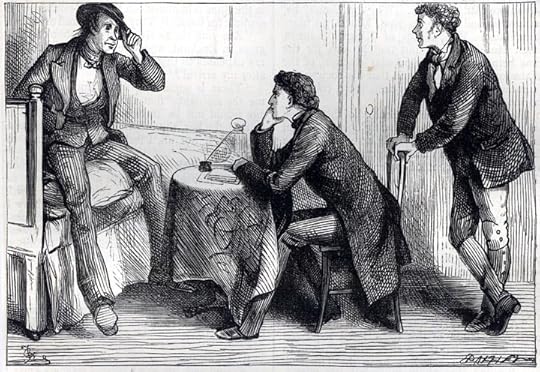

General Choke and Mr. Scadder

Chapter 21

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Commentary:

On the wall of land-agent's ramshackle hut Eytinge has positioned a map, but has not indicated its precise nature (as opposed to Phiz's having included a detailed town plan in "The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared on Paper" for the September 1843, ninth monthly part). However, to add to the verisimilitude of the illustration Eytinge has included Scadder's rocking chair and office desk (left). The scene realised occurs just after Mark and Martin, accompanied by Choke, arrive at the office of the Eden Land Corporation on the banks of the Mississippi River:

They, desiring nothing more, agreed; so off they all four started for the office of the Eden Settlement, which was almost within rifle-shot of the National Hotel.

It was a small place — something like a turnpike. But a great deal of land may be got into a dice-box, and why may not a whole territory be bargained for in a shed? It was but a temporary office too; for the Edeners were 'going' to build a superb establishment for the transaction of their business, and had already got so far as to mark out the site. Which is a great way in America. The office-door was wide open, and in the doorway was the agent; no doubt a tremendous fellow to get through his work, for he seemed to have no arrears, but was swinging backwards and forwards in a rocking-chair, with one of his legs planted high up against the door-post, and the other doubled up under him, as if he were hatching his foot.

He was a gaunt man in a huge straw hat, and a coat of green stuff. The weather being hot, he had no cravat, and wore his shirt collar wide open; so that every time he spoke something was seen to twitch and jerk up in his throat, like the little hammers in a harpsichord when the notes are struck. Perhaps it was the Truth feebly endeavouring to leap to his lips. If so, it never reached them.

Two gray eyes lurked deep within this agent's head, but one of them had no sight in it, and stood stock still. With that side of his face he seemed to listen to what the other side was doing. Thus each profile had a distinct expression; and when the movable side was most in action, the rigid one was in its coldest state of watchfulness. It was like turning the man inside out, to pass to that view of his features in his liveliest mood, and see how calculating and intent they were.

Each long black hair upon his head hung down as straight as any plummet line; but rumpled tufts were on the arches of his eyes, as if the crow whose foot was deeply printed in the corners had pecked and torn them in a savage recognition of his kindred nature as a bird of prey.

Such was the man whom they now approached, and whom the General saluted by the name of Scadder.

"Well, Gen'ral," he returned, "and how are you?"

"Ac-tive and spry, sir, in my country's service and the sympathetic cause. Two gentlemen on business, Mr. Scadder."

He shook hands with each of them, — nothing is done in America without shaking hands, — then went on rocking.

"I think I know what bis'ness you have brought these strangers here upon, then, Gen'ral?"

"Well, sir. I expect you may."

"You air a tongue-y person, Gen'ral. For you talk too much, and that's fact," said Scadder. "You speak a-larming well in public, but you didn't ought to go ahead so fast in private. Now!"

"If I can realise your meaning, ride me on a rail!" returned the General, after pausing for consideration.

"You know we didn't wish to sell the lots off right away to any loafer as might bid," said Scadder; "but had con-cluded to reserve 'em for Aristocrats of Natur'. Yes!"

"And they are here, sir!" cried the General with warmth. "They are here, sir!"

"If they air here," returned the agent, in reproachful accents, "that's enough. But you didn't ought to have your dander ris with me, Gen'ral."

The General whispered Martin that Scadder was the honestest fellow in the world, and that he wouldn't have given him offence designedly, for ten thousand dollars.

"I do my duty; and I raise the dander of my feller critters, as I wish to serve," said Scadder in a low voice, looking down the road and rocking still. "They rile up rough, along of my objecting to their selling Eden off too cheap. That's human natur'! Well!"

Exactly as in the passage realised, Zaphaniah Scadder, the Eden Company's land-agent, is "swinging backwards and forwards in a rocking-chair, with one of his legs planted high up against the door-post, and the other doubled up under him, as if he were hatching his foot" — Eytinge has even depicted the nails in the sole of his boot, but has not attempted to depict the two very different sides of his face; rather, Eytinge shows him in profile. Despite his casual posture and less formal attire, Scadder is as much a humbug as Colonel Cyrus Coke, U. S. — or Seth Pecksniff, for that matter. The General, like Pecksniff, is merely an American swindler of a higher order: better dressed, more subtle, and more verbally persuasive. Their underlying similarity Eytinge emphasizes by equipping each of them with a similar case-knife. In Phiz's celebrated engraving "The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared on Paper" (September 1843, Chapter 21) the land-agent circumspectly studies the two English "greenhorns," who in turn study the town site plans for Eden with considerable enthusiasm. Sol Eytinge, on the other hand, studies the swindlers without reference to their latest victims. In both illustrations, Scadder wears a less formal straw hat, doubtless to combat the heat. The wonderful textures of their faces and clothing in Eytinge's woodcut make the pair seem outgrowths of nature and extensions of the natural environment, although General Choke's visage more nearly approaches that of a bird of prey than the phlegmatic Scadder's. To Eytinge, they are typical carpet-baggers, and hardly "two of the most remarkable men in the country," or "Aristocrats of Natur'." A telling detail which Eytinge has invented is Scadder's picking his teeth with his case-knife.

"Well, sir!" said the Captain, putting his hat a little more on one side, for it was rather tight in the crown: "You're quite a public man I calc'late."

Chapter 22

Fred Barnard

In Chapter 22, in their room at the National Hotel in Watertoast, Martin Chuzzlewit and Mark Tapley are visited at The National Hotel by their landlord, the affable Captain Kedgick, who is vastly amused that Martin has been asked by the Watertoast Society's Secretary, the oxymoronic La Fayette Kettle, to deliver a lecture on the Tower of London, and that the leading citizens insist upon attending a "le—vee" for him. This whole episode reflects young writer Charles Dickens's own reception in America as a literary lion.

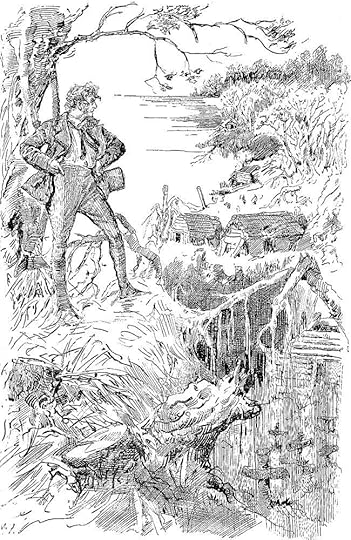

The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared in Fact

Chapter 23

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

And lastly, he brought forth a great placard (which Martin in the exultation of his heart had prepared with his own hands at the National Hotel) bearing the inscription, CHUZZLEWIT & CO., ARCHITECTS AND SURVEYORS, which he displayed upon the most conspicuous part of the premises, with as much gravity as if the thriving city of Eden had a real existence, and they expected to be overwhelmed with business.

"These here tools," said Mark, bringing forward Martin's case of instruments and sticking the compasses upright in a stump before the door, "shall be set out in the open air to show that we come provided. And now, if any gentleman wants a house built, he'd better give his orders, afore we're other ways bespoke."

Considering the intense heat of the weather, this was not a bad morning's work; but without pausing for a moment, though he was streaming at every pore, Mark vanished into the house again, and presently reappeared with a hatchet; intent on performing some impossibilities with that implement.

"Here's ugly old tree in the way, sir," he observed, "which'll be all the better down. We can build the oven in the afternoon. There never was such a handy spot for clay as Eden is. That's convenient, anyhow."

But Martin gave him no answer. He had sat the whole time with his head upon his hands, gazing at the current as it rolled swiftly by; thinking, perhaps, how fast it moved towards the open sea, the high road to the home he never would behold again.

Not even the vigorous strokes which Mark dealt at the tree awoke him from his mournful meditation. Finding all his endeavours to rouse him of no use, Mark stopped in his work and came towards him.

"Don't give in, sir," said Mr. Tapley.

"Oh, Mark," returned his friend, "what have I done in all my life that has deserved this heavy fate?"

Commentary:

New Forces at Work in Browne's Illustrations:

In Victorian Novelists and Their Illustrators (1970), John Harvey has detected influences other than the illustrations of George Cruikshank in Browne's work for Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit — in particular, the emblematic style of eighteenth-century print-maker William Hogarth and the social criticism and whimsy of French cartoonist and lithographer Honoré Daumier (1808-79), whose La Garde-Malade (22 May 1842) in caricaturist Charles Philipon's Paris magazine of satire and social commentary Le Charivari may well have inspired Browne's iconic images of Sairey Gamp.

Partly inspired by Daumier, the new sharpness and energy of Browne's drawing is a fit accompaniment to the new 'suggestiveness, compact and sure of stroke' in Dickens's prose, and the Dickens's new sense of the way in which each visual detail can tell a story. In the following instructions for the plate 'The Thriving City of Eden as it appeared in Fact' . . . , Dickens is virtually moving the pencil himself; he imagines the plate in detail, and except for remembering that the river flows towards home, his details are not the psychic [i. e., psychological] details one expects of a novelist, but the telling visual particulars of an artist like Hogarth. The picture he describes is a typical Hogarthian scene of tumbledown confusion, with its ironic written placards, with characterizing utensils that are not being used; the tools of men's trades, in and out of use, are always significant in Hogarth . . . .

The placards in the Eden scene, as Harvey has noted, constitute Dickens's embedded commentary on the plight of the bedraggled representatives of European civilisation who are confronting the primeval wilderness of the Mississippi Valley. Martin "& Co." grandiously implies a firm of architects and surveyors, but in fact designates only Mark. And, pointing towards the unscrupulous land-speculators who are taking advantage of unknowing immigrants, Dickens has specified in his instructions to Phiz the sign "BANK and National Credit Office," an imposing title which the ramshackle appearance of the doorless, windowless log-cabin ironically undercuts. In fact, in his detailed instructions to Browne a month earlier Dickens seems to have thought out in advance how to juxtapose the puny civilising efforts of the colonists and the resilient, oppositional life-force of the American wilderness.

Dickens's Specific Instructions to Phiz for this Illustration:

The part of Dickens's 15-18 April 1843 letter on this "second subject" (the first being the envisioned "City" of Eden outlined in the town plan posted on the wall of the land office) has survived probably because it was neither returned to Dickens nor retained by Browne, both of whom burned much of their early correspondence. It is one of the few letters of instruction that survived the artist's and author's bonfires, possibly because it was retained by Chapman and Hall as instructions to the compositor. Valerie Lester mentions John Forster, Dickens's literary agent who sometimes acted on Dickens's behalf when the author was out of London, as another possible source of these letters of instruction for Martin Chuzzlewit since he may have "saved them, having given Phiz the instructions verbally or in another letter" (personal communication 16 May 2007). The contents of the letter do not furnish a clue to its survival, but the marginal notes, written in another hand but clearly dictated by Dickens, and Browne's penciled in rejoinder at the bottom of the page imply that the letter was initially sent to Browne, who then replied as to what he could and could not "shew" before Dickens dictated a few final thoughts about the composition of "The thriving City of Eden as it appeared in fact" (the second illustration for the ninth monthly part).

The First Subject having shewn the settlement of Eden on paper, the second shews it in reality. Martin and Mark are displayed as the tenants of a wretched log hut (for a pattern whereof, see a Vignette brought by Chapman and Hall) in perfectly flat swampy, wretched forest of stunted timber in every stage of decay with a filthy river running before the door, and some other miserable loghouse indicated among the trees, whereof the most ruinous and tumbledown of all, is labelled BANK And National Credit Office. Outside their door, as the custom is, is a rough sort of form or dresser, on which are set forth their pot and kettle and so forth: all of the commonest kind. On the outside of the house at one side of the door, is a written placard CHUZZLEWIT AND Co. ARCHITECTS AND SURVEYORS; and upon a stump of tree, like a butcher's block, before the cabin, are Martin's instruments — a pair of rusty compasses &c On a three legged stool beside this block, sits Martin in his shirt sleeves, with long dishevelled hair, resting his head upon his hands: the picture of hopeless misery — watching the river, as sadly remembering that it flows towards home. But Mr. Tapley, up to his knees in filth and brushwood, and in the act of endeavouring to perform some impossibilities with a hatchet, looks towards him with a face of unimpaired good humor, and declares himself perfectly jolly. Mark the only redeeming feature. Everything else dull, miserable, squalid, unhealthy, and utterly devoid of hope: diseased, starved, and abject. The weather is intensely hot, and they are but partially clothed.

According to the note in the relevant volume of the Pilgrim Edition of Dickens's Letters, Browne modestly asserted his own interpretation:

At the foot of the page another hand has written: "With 2 Sketches" and Browne has written in pencil "I can't get all this perspective in — unless you will allow of a long subject — something less than a mile." Browne's sketch resembles the illustration except that the stump is larger and not growing in the ground, the Chuzzlewit placard is differently placed, and the other reads only "BANK". Beneath it is written (with two vertical lines indicating the width of the block) "too wide — cannot it be compressed by putting Martin's label on the other side of the door and bringing Mark with his tree forwarder [.] qy is that a hat on his head", and "the stump of the tree should be in the ground in fact a tree cut off two up [rough sketch]". The hand is neither CD's nor Browne's, but the substance of the comment suggests that they are CD's, perhaps dictated at the printing office to a member of the staff when CD was in London again 24-26 Aug. The required changes were made, but the hat looks exactly the same on the plate.

Steig in his 1972 Dickens Studies Annual article notes that, although the degree of correspondence between the detailed instructions and the eighteenth plate is great, Phiz has added from his own imagination two small toads, one regarding Martin and the other caught in the act of jumping into the water, "conceivably as an allusion to Martin's thoughts of suicide". Jane Rabb Cohen in Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators (1980) has positioned the seventeenth and eighteenth plates side by side on page 89 to invite her reader to compare these as expectation and fulfillment: the web-like plan (so unlike real American town plans, which customarily involved a rational grid) with the pump at its center being the triumphant imposition of civilization upon the wilderness, and then the trees and unruly grasses, suggestive of the power of nature, surrounding the settlers. Cohen concludes that the extreme number of details that Dickens specified (including the lines indicating the desired width) so curtailed Phiz's authority as an artist that he was able to respond with merely "a dutiful but uninspired picture".

However, whereas Dickens had specified that there be in the background a "wretched forest of stunted timber in every stage of decay," Browne has provided robust and stately trees of some height and possessing straight trunks, implying that the town-site possesses a potential for construction and habitation that Mark can see and Martin, filled with self-pity, cannot. Phiz, then, explodes the pathetic fallacy: whereas Mark revels in the challenge posed by the natural scene, Martin is immobilized by the apparent lack of opportunity for a young man who is trying to pass himself off as an architect. . . . . The placards and general confusion which Dickens envisages are especially reminiscent of Hogarth, and the rusty compasses are a detail reminiscent of such graphic artists as Dürer. Browne has asserted himself against Dickens the visualizer, the would-be illustrator, by rejecting aspects of these instructions impossible to realize visually (such as the intense heat) and by including the toads, changing the author's conception of the surrounding wilderness, and particularly through the hat with which he has persisted in providing Mark Tapley even as Dickens has queried it.

Martin Chuzzlewit and Mark Tapley

Chapter 23

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Commentary:

Having made their way by steamboat to the Mississippi Valley settlement of Eden, Mark Tapley and young Martin Chuzzlewit set up an architectural business on the strength of Martin's limited apprenticeship with Seth Pecksniff in the little Wiltshire village. Quickly the naieve Englishmen discover that the hyperbolically named Eden is nothing but a collection of ramshackle log cabins surrounded by a pestilential swamp. When Martin falls deathly ill, likely from malarial swamp fever, Mark tends him. Eytinge has chosen this critical moment in their relationship as the vehicle for his depiction of them, undoubtedly aware of Phiz's depiction of the young settlers and their log cabin in "The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared in Fact", the second illustration for the September 1843 (ninth monthly) part. However, Eytinge only suggests the physical setting through the partially visible business sign, the letters "IT" and "CO" representing Martin (left) and Mark (right) respectively; the intention of the illustrator is to contrast the characters: the dark-clad, infirm, and severely depressed Martin, who reaches out for Mark's support; and the cheerful but deeply solicitous (and obviously more robust) Mark, who is so different from the ebullient, wise-cracking Cockney holding aloft an axe in Phiz's original illustration for chapter 23. The passage which Phiz had realised earlier, and which Eytinge has reinterpreted with an emphasis on character rather than setting or narrative is this:

Martin was by this time stirring; but he had greatly changed, even in one night. He was very pale and languid; he spoke of pains and weakness in his limbs, and complained that his sight was dim, and his voice feeble. Increasing in his own briskness as the prospect grew more and more dismal, Mark brought away a door from one of the deserted houses, and fitted it to their own habitation; then went back again for a rude bench he had observed, with which he presently returned in triumph; and having put this piece of furniture outside the house, arranged the notable tin pot and other such movables upon it, that it might represent a dresser or a sideboard. Greatly satisfied with this arrangement, he next rolled their cask of flour into the house and set it up on end in one corner, where it served for a side-table. No better dining-table could be required than the chest, which he solemnly devoted to that useful service thenceforth. Their blankets, clothes, and the like, he hung on pegs and nails. And lastly, he brought forth a great placard (which Martin in the exultation of his heart had prepared with his own hands at the National Hotel) bearing the inscription, CHUZZLEWIT & CO., ARCHITECTS AND SURVEYORS, which he displayed upon the most conspicuous part of the premises, with as much gravity as if the thriving city of Eden had a real existence, and they expected to be overwhelmed with business.

Certainly the tribulations of the dubiously named "Eden" have given Mark Tapley plenty of scope for self-denial, testing his determination to remain jolly under the most trying of circumstances rather than settling into the comfortable role of publican with the comely hostess of the Blue Dragon in the little Wiltshire village where he met the egocentric Martin Chuzzlewit. Eytinge effectively dramatises Mark's selfless concern for his business partner by Mark's interrogative gaze mingled with his eternal optimism and determination to win through. Eytinge has distinguished the young men not merely by their dress, but by their facial expressions, postures, and underlying attitudes. The American illustrator also deftly represents the savage environment by the stunted, rotting trees to the right. Stepping out of the highly-realistic log cabin, Martin is pallid and disoriented, barely registering the presence of the friend upon whose arm he endeavours to support himself and regain his balance as he attempts to walk out of the cabin. Mark, too, receives some psychological examination in Eytinge's dual portrait as he steadies Martin and by his solicitous look enquiries as to what more he may do to support his friend in illness and despair. Striving to maintain his sense of his civilised, "English" self, Mark still wears a top hat, tie, and clean shirt, whereas Martin's dark pea coat and neckerchief suggest his present psychological state, and suggest his impending encounter with death.

Eden!

Chapter 23

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

As they proceeded further on their track, and came more and more towards their journey's end, the monotonous desolation of the scene increased to that degree, that for any redeeming feature it presented to their eyes, they might have entered, in the body, on the grim domains of Giant Despair. A flat morass, bestrewn with fallen timber; a marsh on which the good growth of the earth seemed to have been wrecked and cast away, that from its decomposing ashes vile and ugly things might rise; where the very trees took the aspect of huge weeds, begotten of the slime from which they sprung, by the hot sun that burnt them up; where fatal maladies, seeking whom they might infect, came forth at night in misty shapes, and creeping out upon the water, hunted them like spectres until day; where even the blessed sun, shining down on festering elements of corruption and disease, became a horror; this was the realm of Hope through which they moved.

At last they stopped. At Eden too. The waters of the Deluge might have left it but a week before; so choked with slime and matted growth was the hideous swamp which bore that name.

There being no depth of water close in shore, they landed from the vessel's boat, with all their goods beside them. There were a few log-houses visible

"Here comes an Edener," said Mark. "He'll get us help to carry these things up. Keep a good heart, sir. Hallo there!"

The man advanced toward them through the thickening gloom, very slowly; leaning on a stick. As he drew nearer, they observed that he was pale and worn, and that his anxious eyes were deeply sunken in his head. His dress of homespun blue hung about him in rags; his feet and head were bare. He sat down on a stump half-way, and beckoned them to come to him. When they complied, he put his hand upon his side as if in pain, and while he fetched his breath stared at them, wondering.

Commentary:

In graphing the jungle desolation of the Mississippi wilderness, Furniss was responding to a pair of Phiz illustrations in the original serial, the land and settlement as advertised in The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared on Paper (September 1843, Chapter 21) and the disgusting actuality of the malarial swamp, The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared in Fact (September 1843, Chapter 23). Whereas Fred Barnard in the Household Edition dwelt upon the humorous misconceptions of Martin's American acquaintances about England and the English, Furniss reverts to the land-swindling scheme. Martin nearly succumbs to both disease and self-pity, but Mark proves himself more than a match for the American wilderness; thus, in Furniss's Eden illustration he stands above it, like a Miltonic angel surveying lower creation in Paradise Lost. Bestriding the hillside like a colossus, Mark dwarfs the city's crumbling log-cabins. The perilous nature of the unhealthy location is exemplified by the six grave-markers in the bottom right-hand corner — and, whereas Dickens immediately introduces Mark to a wasted "Edener," Furniss shows no other living beings in this North American jungle. Also missing from the 1910 illustration but foregrounded in the 1843 engraving is the despondent Martin, sitting in front of his architectural "business" while Mark goes to work to tame the wilderness and make the best of an unpleasant situation. What dominates the Furniss illustration, being at the same level as Mark himself, is the mighty Mississippi at the top of the illustration, suggestive of the Old Testament Deluge in retreat. The rest of the picture is hardly "Eden," but a post-lapsarian world of weed-like trees growing out of the primordial ooze.

I don't know if Dickens was complaining about celebrity status so much as he was peeved that others were benefiting from his works without giving him a percentage. Or even recognizing he had rights to his own work. He probably had some cause. Certainly copyright laws grew indignantly important as soon as corporate-owned property was on the block.

I don't know if Dickens was complaining about celebrity status so much as he was peeved that others were benefiting from his works without giving him a percentage. Or even recognizing he had rights to his own work. He probably had some cause. Certainly copyright laws grew indignantly important as soon as corporate-owned property was on the block. I don't think that was the biggest reason for Dicken's angst with America though. The nation's hypocrisy seemed to get to him most.

To ask if "Americans" were then so averse to Abolitionists is an impossible question because Amercians weren't of one mind. Obviously. This comes only two decades before the Civil War, and sentiment wasn't uniform in either the North or South. Of course the writer was himself an Abolitionist. He was surely called some names.

BTW, the factual recounting of his travels in American Notes is interesting in light of these American sections of MC, because it's like seeing the raw materials for his story that he built upon. Dickens' capacity for descriptive language is really amazing. He repeats scenes without repeating words or even concepts--and both are pretty great.

Another thing I find interesting is how prescient and on-target Dickens' criticism are. Our country is still under the sway of commercial confidence trickery and being psychologically compartmentalized to the point of imagining ourselves to be something quite different than we really are.

The author's bitterness for a certain kind of "ugly American"--a century before the actual concept was popularized--shows through in his passage about Mrs. Hominy:

"... a large class, of her fellow countrymen, who in their every word, avow themselves to be as senseless to the high principles on which America sprang, a nation, into life, as any Orson in her legislative halls. Who are no more capable of feeling, or of caring if they did feel, that by reducing their own country to the ebb of honest men’s contempt, they put in hazard the rights of nations yet unborn, and very progress of the human race, than are the swine who wallow in their streets."

Yes, Dickens just called a lot of Americans "swine" to their faces ... he wasn't sanguine about his disappointment in the land of the free. He has Martin echo this sentiment more briskly in the next chapter:

"As if their work were infinitely above their powers and purpose, Mark; and they botched it in consequence."

Bobbie wrote: "I thought that was a good observation Tristram that he was in a way complaining about his own celebrity status."

Thanks, Bobbie :-)

Thanks, Bobbie :-)

Thanks, Kim, for providing those illustrations and the accompanying comments. I learnt a lot, and I found it especially interesting that Dickens failed to see how quickly places could change in the U.S. and that, had Martin and Mark persevered, they could have made a fortune as architects of Eden.

Julie wrote: "I don't really think of Mark as a character so much anymore--more as a concept and a Greek chorus. But an entertaining one. I'm glad he's there...."

Julie wrote: "I don't really think of Mark as a character so much anymore--more as a concept and a Greek chorus. But an entertaining one. I'm glad he's there...."Julie,

I really like your analysis of Mark as a “concept.” I agree. As entertaining as he is (and he does make me actually laugh out loud at points), it feels like he’s still unsketched compared to some of Dickens other character’s in similar roles (for example, I’m thinking of Sam Weller who feels much more dynamic).

I feel that Mark has to be a somewhat unbelievable character in order for the novel to function. Otherwise, what reasonably sane person would knowingly allow themselves to fall into Scadder’s trick for the sake of “testing” themselves?

Emma wrote: "Julie wrote: "I don't really think of Mark as a character so much anymore--more as a concept and a Greek chorus. But an entertaining one. I'm glad he's there...."

Emma wrote: "Julie wrote: "I don't really think of Mark as a character so much anymore--more as a concept and a Greek chorus. But an entertaining one. I'm glad he's there...."Julie,

I really like your analy..."

He does seem very Weller-esque! I remember reading that Pickwick Papers took off after Sam Weller was introduced and I wonder if--in addition to his chorus role--Mark's increasing presence in the book is an attempt to try that successful Weller move again in response to the low MC sales we've discussed here?

Julie wrote: "Emma wrote: "Julie wrote: "I don't really think of Mark as a character so much anymore--more as a concept and a Greek chorus. But an entertaining one. I'm glad he's there...."

Julie,

I really li..."

Julie. Your comment that Mark might have been used by Dickens in a similar fashion to Sam Weller in order to boost sales makes sense. If so, I think Dickens has been much less successful this time. Sam Weller was a brilliant creation and his relationship to Mr Pickwick worked exceedingly well. For me, however, while Mark is an engaging person, he is somewhat stilted and wooden.

I also like your idea that Mark is somewhat like a Greek Chorus. He certainly functions as a recorder and commentator for the time spent in America.

Julie,

I really li..."

Julie. Your comment that Mark might have been used by Dickens in a similar fashion to Sam Weller in order to boost sales makes sense. If so, I think Dickens has been much less successful this time. Sam Weller was a brilliant creation and his relationship to Mr Pickwick worked exceedingly well. For me, however, while Mark is an engaging person, he is somewhat stilted and wooden.

I also like your idea that Mark is somewhat like a Greek Chorus. He certainly functions as a recorder and commentator for the time spent in America.

Kim

This week’s illustrations and their commentaries certainly broaden and deepen our understanding of the chapters. For me, the two Phiz illustrations of “The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared on Paper” and “The Thriving City of Eden as it appeared in fact” offer the reader an excellent visual extention to the letterpress. The first illustration shows us Martin and Mark inside. They are well-dressed and engaged in the possibilities that await them in Eden. The second illustration is an exterior depiction of Eden. The clothes, the postures, and the presence of Mark and Martin have changed significantly. In the second illustration we see quite clearly how Mark has assumed the role of master.

The commentaries to the illustrations also give us an insight into how Hablot Browne has taken Dickens’s directions for the illustrations and enhanced them with such emblematic details as a mousetrap to a spider’s web to suggest what will be coming next in the narrative,

This week’s illustrations and their commentaries certainly broaden and deepen our understanding of the chapters. For me, the two Phiz illustrations of “The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared on Paper” and “The Thriving City of Eden as it appeared in fact” offer the reader an excellent visual extention to the letterpress. The first illustration shows us Martin and Mark inside. They are well-dressed and engaged in the possibilities that await them in Eden. The second illustration is an exterior depiction of Eden. The clothes, the postures, and the presence of Mark and Martin have changed significantly. In the second illustration we see quite clearly how Mark has assumed the role of master.

The commentaries to the illustrations also give us an insight into how Hablot Browne has taken Dickens’s directions for the illustrations and enhanced them with such emblematic details as a mousetrap to a spider’s web to suggest what will be coming next in the narrative,

One distinct advantage that later illustrators of Dickens’s works had was that they had seen the original illustrations of Phiz that came before their own attempt. Later illustrators also had the luxury of having the opportunity to read the completed text, sometimes multiple times before they commenced their illustrations.

The Harry Furniss illustration is striking. As Mark surveys the landscape of Eden “like a Miltonic angel surveying Eden” we see the advantage of having read the novel and viewed the Phiz illustrations. What came to the original readers in separate parts with Phiz can now be reimagined by Furniss in a much more dramatic form.

The Harry Furniss illustration is striking. As Mark surveys the landscape of Eden “like a Miltonic angel surveying Eden” we see the advantage of having read the novel and viewed the Phiz illustrations. What came to the original readers in separate parts with Phiz can now be reimagined by Furniss in a much more dramatic form.

I came across a letter Dickens sent to John Forster during his trip to America. I find it fascinating, the part I'm going to show you that is, because according to what he writes he must have gone almost right past my house! The letter starts in York, Pennsylvania, travels to Harrisburg, which is where I was today looking at Christmas decorations, then travels up the Susquehanna river where in about an hour he would have passed the road to my house about twenty minutes away. I have even kayaked on part of the canal he writes about. However, if I had been with him on his trip I think I'd be ready to leave America and head to England myself. Here it is, it's long so it may take a few posts:

. . . "We left Baltimore last Thursday, the twenty-fourth, at half-past eight in the morning, by railroad; and got to a place called York, about twelve. There we dined, and took a stage-coach for Harrisburg; twenty-five miles further. This stage-coach was like nothing so much as the body of one of the swings you see at a fair set upon four wheels and roofed and covered at the sides with painted canvas. There were twelve inside! I, thank my stars, was on the box. The luggage was on the roof; among it, a good-sized dining-table, and a big rocking-chair. We also took up an intoxicated gentleman, who sat for ten miles between me and the coachman; and another intoxicated gentleman who got up behind, but in the course of a mile or two fell off without hurting himself, and was seen in the distant perspective reeling back to the grog-shop where we had found him. There were four horses to this land-ark, of course; but we did not perform the journey until after half-past six o'clock that night. . . . The first half of the journey was tame enough, but the second lay through the valley of the Susquehanah (I think I spell it right, but I haven't that American Geography at hand), which is very beautiful. . . .