The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

MC Chapters 30-32

Chapter 31

We begin this chapter in the church where Tom Pinch is playing a small pump organ. Tom plays for nothing which I imagine was the wage of most rural church organists. As he plays inside the church we find Mr Pecksniff strolling in the churchyard. Pecksniff enters the church intent on finding a comfortable corner to rest. Soon, Pecksniff begins to doze off only to hear voices. Pecksniff, being Pecksniff, decides to eavesdrop on the speakers who turn out to be Tom and Mary Graham. From his vantage point, half-hidden in the recess of the church, Pecksniff peeks at the speakers.

Tom and Mary’s conversation concerns the lack of letters that have arrived from young Martin to Mary. In fact, she has received only one from New York. Mary is very concerned and Tom attempts to ease her mind with words of care and comfort. Mary gives Tom her hand and says “I cannot tell you how your kindness moves me ... . Without the silent care and friendship I have experienced from you my life here would have been unhappy.” Mary explains that she has been silent about young Martin so as to avoid any conflict with Pecksniff to which Tom replies “[h]e is not a spy.” Oh, Tom. If only you knew the truth, if only you knew who was listening this second in the church. Meanwhile, hearing these words from his hiding place, Pecksniff listens “more attentively than ever, and smiled.”

Poor Tom is somewhat befuddled. He tells Mary that like her, John Westlock and every other pupil of Pecksniff’s have shared an “inveterate hatred” of Pecksniff as well, including young Martin. Tom does not understand why. Again I say, poor Tom. Mary tells Tom about Pecksniff’s unwanted attentions towards her. Tom’s naïveté instantly dissolves. Mary then recounts how Pecksniff “with a smooth tongue and a smiling face, in the broad light of day: dragg[ed] me on, the while, in his embrace, and holding to his lips a hand ...” while Mary recounts the horror of her experience with Pecksniff, he continues to lurk within the church. A snake in a symbolic garden?

Thoughts

As Pecksniff listens in on the conversation of Tom and Mary I found Dickens portrays his actions of peeking above the pew and being self-satisfied in a clearly humourous manner. Did you find it humourous as well? Why would Dickens insert the element of humour into an otherwise serious conversation?

The early paragraphs of this chapter give us much to consider. Pecksniff’s wanderings in the churchyard, entering the church, and then listening to the private conversation between Mary and Tom further solidify our impression of him. How would you characterize Pecksniff’s character at this point in the novel? Do you have any sympathy towards him? What other Dickens characters does he remind you of in the novels we have read?

In these paragraphs Tom is finally able to see the true nature of Pecksniff. Did you find his rapid insight to be believable?

Mary gives an account of Pecksniff’s treatment of her in the woods. To what extent did the description of the physicality of Pecksniff towards Mary surprise you given the fact this is a 19C novel? Do you think Pecksniff is capable of the horrors of Sykes?

Dickens tells us that with his learning of Pecksniff’s true character Tom’s opinion of Pecksniff turned into a “putrid vapour.” What a great couple of words of description. What other phrases did you enjoy in this chapter?

In this and a recent chapter Tom has received the trust and friendship of both Cherry and Mary. Do you see this as a harbinger of something that may occur in future chapters? Why/why not?

Pecksniff takes his time leaving the church. In fact, he enjoys some port-wine and biscuits he finds in a church cupboard. He then slips out a church window and heads home where he finds old Martin. Pecksniff spins a series of lies about Tom, casts himself as a man deceived by Tom who he calls a “Fiery Serpent” and tells Chuzzlewit that he will deal with treacherous Tom Pinch. Pecksniff soon comes into contact with Tom and tells him he has overheard all that was said between Mary and himself. Pecksniff stages the confrontation between himself and Tom so that old Martin can be a witness. Pecksniff also insures that Mary is not in the room. Pecksniff the stage manager. Oh, he is an odious man. With lies and half-truths Pecksniff berates Tom’s lack of duty and honour but is clever enough to include the fact that Tom has feeling for Mary. No doubt, this would play well in old Martin’s ears.

Tom, for his part, has awakened to Pecksniff’s character and realizes that Pecksniff “had devised this fiction as the readiest means of getting rid of him at once.” For his part, old Martin was completely taken in by Pecksniff’s performance and says to Pecksniff “I am glad he has gone.” It takes Tom little time to pack his belongings and he leaves Pecksniff’s home. Tom is greeted by Mrs Lupin and others who do care for him, and so contrary to Pecksniff’s angry dismissal comes the love and care of others such as the toll gate keeper and his wife. Tom makes his way to Salisbury where he had once waited for young Martin. Tom says his prayers which made him feel better and he finally falls asleep as our chapter ends.

Thoughts

Pecksniff loves an audience and makes sure that old Martin is present when he dismisses Tom. To what extent does this scene suggest that old Martin has been completely taken in by Pecksniff?

Tom leaves quietly rather than arguing for his own position and dignity. Why do you think Tom did not counter Pecksniff’s comments?

Pecksniff has now cleared his home of Merry, Cherry, and Tom. This means only old Martin and Mary remain. What might be Pecksniff’s next plans?

Tom Pinch is now alone and without any confirmed prospects for the future. What do you think he will do?

We begin this chapter in the church where Tom Pinch is playing a small pump organ. Tom plays for nothing which I imagine was the wage of most rural church organists. As he plays inside the church we find Mr Pecksniff strolling in the churchyard. Pecksniff enters the church intent on finding a comfortable corner to rest. Soon, Pecksniff begins to doze off only to hear voices. Pecksniff, being Pecksniff, decides to eavesdrop on the speakers who turn out to be Tom and Mary Graham. From his vantage point, half-hidden in the recess of the church, Pecksniff peeks at the speakers.

Tom and Mary’s conversation concerns the lack of letters that have arrived from young Martin to Mary. In fact, she has received only one from New York. Mary is very concerned and Tom attempts to ease her mind with words of care and comfort. Mary gives Tom her hand and says “I cannot tell you how your kindness moves me ... . Without the silent care and friendship I have experienced from you my life here would have been unhappy.” Mary explains that she has been silent about young Martin so as to avoid any conflict with Pecksniff to which Tom replies “[h]e is not a spy.” Oh, Tom. If only you knew the truth, if only you knew who was listening this second in the church. Meanwhile, hearing these words from his hiding place, Pecksniff listens “more attentively than ever, and smiled.”

Poor Tom is somewhat befuddled. He tells Mary that like her, John Westlock and every other pupil of Pecksniff’s have shared an “inveterate hatred” of Pecksniff as well, including young Martin. Tom does not understand why. Again I say, poor Tom. Mary tells Tom about Pecksniff’s unwanted attentions towards her. Tom’s naïveté instantly dissolves. Mary then recounts how Pecksniff “with a smooth tongue and a smiling face, in the broad light of day: dragg[ed] me on, the while, in his embrace, and holding to his lips a hand ...” while Mary recounts the horror of her experience with Pecksniff, he continues to lurk within the church. A snake in a symbolic garden?

Thoughts

As Pecksniff listens in on the conversation of Tom and Mary I found Dickens portrays his actions of peeking above the pew and being self-satisfied in a clearly humourous manner. Did you find it humourous as well? Why would Dickens insert the element of humour into an otherwise serious conversation?

The early paragraphs of this chapter give us much to consider. Pecksniff’s wanderings in the churchyard, entering the church, and then listening to the private conversation between Mary and Tom further solidify our impression of him. How would you characterize Pecksniff’s character at this point in the novel? Do you have any sympathy towards him? What other Dickens characters does he remind you of in the novels we have read?

In these paragraphs Tom is finally able to see the true nature of Pecksniff. Did you find his rapid insight to be believable?

Mary gives an account of Pecksniff’s treatment of her in the woods. To what extent did the description of the physicality of Pecksniff towards Mary surprise you given the fact this is a 19C novel? Do you think Pecksniff is capable of the horrors of Sykes?

Dickens tells us that with his learning of Pecksniff’s true character Tom’s opinion of Pecksniff turned into a “putrid vapour.” What a great couple of words of description. What other phrases did you enjoy in this chapter?

In this and a recent chapter Tom has received the trust and friendship of both Cherry and Mary. Do you see this as a harbinger of something that may occur in future chapters? Why/why not?

Pecksniff takes his time leaving the church. In fact, he enjoys some port-wine and biscuits he finds in a church cupboard. He then slips out a church window and heads home where he finds old Martin. Pecksniff spins a series of lies about Tom, casts himself as a man deceived by Tom who he calls a “Fiery Serpent” and tells Chuzzlewit that he will deal with treacherous Tom Pinch. Pecksniff soon comes into contact with Tom and tells him he has overheard all that was said between Mary and himself. Pecksniff stages the confrontation between himself and Tom so that old Martin can be a witness. Pecksniff also insures that Mary is not in the room. Pecksniff the stage manager. Oh, he is an odious man. With lies and half-truths Pecksniff berates Tom’s lack of duty and honour but is clever enough to include the fact that Tom has feeling for Mary. No doubt, this would play well in old Martin’s ears.

Tom, for his part, has awakened to Pecksniff’s character and realizes that Pecksniff “had devised this fiction as the readiest means of getting rid of him at once.” For his part, old Martin was completely taken in by Pecksniff’s performance and says to Pecksniff “I am glad he has gone.” It takes Tom little time to pack his belongings and he leaves Pecksniff’s home. Tom is greeted by Mrs Lupin and others who do care for him, and so contrary to Pecksniff’s angry dismissal comes the love and care of others such as the toll gate keeper and his wife. Tom makes his way to Salisbury where he had once waited for young Martin. Tom says his prayers which made him feel better and he finally falls asleep as our chapter ends.

Thoughts

Pecksniff loves an audience and makes sure that old Martin is present when he dismisses Tom. To what extent does this scene suggest that old Martin has been completely taken in by Pecksniff?

Tom leaves quietly rather than arguing for his own position and dignity. Why do you think Tom did not counter Pecksniff’s comments?

Pecksniff has now cleared his home of Merry, Cherry, and Tom. This means only old Martin and Mary remain. What might be Pecksniff’s next plans?

Tom Pinch is now alone and without any confirmed prospects for the future. What do you think he will do?

Chapter 32

We leave Tom Pinch at the inn and pick up what’s happening to Cherry in this chapter. She has made her way to Todgers’s where Mrs Todgers offers Cherry much sympathy. She tells Cherry that she loved her like a sister “and felt her injuries as if they were her own.” Mrs Todgers tells Cherry that her sister Merry is looking poorly. There has evidently been much misery at Todgers’s as the youngest male border who goes by the name of Moodle has been in a deep depression since Merry’s wedding. Indeed, it appears for a time he may have taken leave of his senses. Moodle is the meekest of men and evidently can be brought to tears with a simple look. He can only find comfort in female society. Such comfort is not initially found with Cherry who treats him with “distant haughtiness.”

Evidently, Cherry’s nose, in fact all of Cherry’s profile, but especially her nose, reminds Moodle of Merry (who Moodle refers to as “who is Another”). Cherry finally asks Moodle to play a rubber of cribbage. This goes on for seven days, and then another seven days when, on the fourteenth day, Moodle kissed Cherry’s sniffers. Well, Moodle soon becomes impressed with the idea that it was Cherry’s mission to comfort him and our Cherry begins to speculate on the probability that it might be her mission to become Mrs Moodle. Moodle was certainly “better looking, better shaped, better spoken, better tempered and better tempered than Jonas.” Soon, Mrs Todgers predicts a coming proposal. Moodle, moved by Cherry’s patience and quiet persistence, asked Cherry if she could be contented with a “blighted heart; and it appearing on further examination that she could be, plighted his dismal troth, which was accepted and returned.” As the chapter ends we have the promise of a wedding in the future.

Thoughts

Will this be the first love connection in the novel to survive?

Were you as relieved as I was to encounter a chapter that has laughter as a foundation or do you see something sinister lurking under the surface of this relationship?

Reflections

This chapter serves a a humourous counterbalance to much courting and marital unpleasantness. The love of Mary and young Martin seems on hold, the marriage of Merry and Jonas has quickly soured, and the repulsive courting of Pecksniff towards Mary have left the reader with little in the way of love. Pecksniff now has cleared his house of all those who could interfere or disrupt his assault on old Martin’s pocket book and Mary’s heart. Tom Pinch is on his way to London and we have not heard about or from young Chuzzlewit or Mark Tapley.

It seems to me as if the pace of the narrative is starting to show signs of life and Pecksniff is both gaining in his domination over old Chuzzlewit and continuing to alienate himself from the other characters in the novel. Is there a breaking point coming soon where Pecksniff will be successful in his quest for money and Mary's hand or will he meet his match in all those he has alienated?

We shall see.

We leave Tom Pinch at the inn and pick up what’s happening to Cherry in this chapter. She has made her way to Todgers’s where Mrs Todgers offers Cherry much sympathy. She tells Cherry that she loved her like a sister “and felt her injuries as if they were her own.” Mrs Todgers tells Cherry that her sister Merry is looking poorly. There has evidently been much misery at Todgers’s as the youngest male border who goes by the name of Moodle has been in a deep depression since Merry’s wedding. Indeed, it appears for a time he may have taken leave of his senses. Moodle is the meekest of men and evidently can be brought to tears with a simple look. He can only find comfort in female society. Such comfort is not initially found with Cherry who treats him with “distant haughtiness.”

Evidently, Cherry’s nose, in fact all of Cherry’s profile, but especially her nose, reminds Moodle of Merry (who Moodle refers to as “who is Another”). Cherry finally asks Moodle to play a rubber of cribbage. This goes on for seven days, and then another seven days when, on the fourteenth day, Moodle kissed Cherry’s sniffers. Well, Moodle soon becomes impressed with the idea that it was Cherry’s mission to comfort him and our Cherry begins to speculate on the probability that it might be her mission to become Mrs Moodle. Moodle was certainly “better looking, better shaped, better spoken, better tempered and better tempered than Jonas.” Soon, Mrs Todgers predicts a coming proposal. Moodle, moved by Cherry’s patience and quiet persistence, asked Cherry if she could be contented with a “blighted heart; and it appearing on further examination that she could be, plighted his dismal troth, which was accepted and returned.” As the chapter ends we have the promise of a wedding in the future.

Thoughts

Will this be the first love connection in the novel to survive?

Were you as relieved as I was to encounter a chapter that has laughter as a foundation or do you see something sinister lurking under the surface of this relationship?

Reflections

This chapter serves a a humourous counterbalance to much courting and marital unpleasantness. The love of Mary and young Martin seems on hold, the marriage of Merry and Jonas has quickly soured, and the repulsive courting of Pecksniff towards Mary have left the reader with little in the way of love. Pecksniff now has cleared his house of all those who could interfere or disrupt his assault on old Martin’s pocket book and Mary’s heart. Tom Pinch is on his way to London and we have not heard about or from young Chuzzlewit or Mark Tapley.

It seems to me as if the pace of the narrative is starting to show signs of life and Pecksniff is both gaining in his domination over old Chuzzlewit and continuing to alienate himself from the other characters in the novel. Is there a breaking point coming soon where Pecksniff will be successful in his quest for money and Mary's hand or will he meet his match in all those he has alienated?

We shall see.

First of all, I'd like to say that I find myself relieved because that point about the organ - the necessity of someone pressing the bellows - has been settled admirably by the narrator. In Chapter 31, we learn why Tom can play the church organ without anyone being nearby. It would have been awkward, wouldn't it, because Mary could not have made her confession to Tom, that demasking of Pecksniff wouldn't have taken place, and Pecksniff would not have had any occasion to eavesdrop on an important conversation.

Never did I find Pecksniff as hideous and crooked as in Chapter 30 where he plainly harasses Mary Graham. His last question, "Shall I bite it?", reminded me of the Serpent in Paradise, even though this time there is no gullible victim to fall for Its snares. As the novel proceeds, we are getting more and more insight into the dark sides of Pecksniff and come to realize that he is not just an average hypocrite but a dyed-in-the-wool villain who will not even shirk from violence and coercion.

Never did I find Pecksniff as hideous and crooked as in Chapter 30 where he plainly harasses Mary Graham. His last question, "Shall I bite it?", reminded me of the Serpent in Paradise, even though this time there is no gullible victim to fall for Its snares. As the novel proceeds, we are getting more and more insight into the dark sides of Pecksniff and come to realize that he is not just an average hypocrite but a dyed-in-the-wool villain who will not even shirk from violence and coercion.

I still find Pecksniff funny in a way, but it's in a very, very creepy way. Imagine being so dependent on someone who is - or appears to be? I wouldn't put it past Martin Sr. to play this out to 'test' those around him - so under the influence of a man like Pecksniff.

That situation does remind me of Sense and Sensibility though. Where a woman was engaged to the man who'd inherit a fortune, and who, as soon as his mother discovered the engagement and wrote him out of her will, got herself married to his younger brother. (After which the mother changed the will again, off course.) I'd not be amazed if Martin Jr. - perhaps even with this novel in the back of his head, Austen was quite popular with the male audience too - watched how Mary would react now it appears to be Pecksniff who'd inherit, and now he proposed to her. She'd seem to be able to secure her future by marriage, would she take it, or would she remain constant? In onther words: did she get engaged with Martin Jr. for his future money, or for love? Her reaction might alter how everything will turn out in the end.

I'm glad Tom is free now, but I found the way it happened a bit quick and easy as well. Perhaps it is because Mary brought in a different point of view, one he couldn't set aside as banter of young men, a realization he couldn't combine her virtue and Pecksniff's, and she'd have nothing to gain by lies. Perhaps it is because he just told her how every single one person who lived in Pecksniff's house thought badly of Pecksniff, added to her story, and it made him realize these all weren't isolated cases? Still, the turn was very, very quick and oh so convenient.

That situation does remind me of Sense and Sensibility though. Where a woman was engaged to the man who'd inherit a fortune, and who, as soon as his mother discovered the engagement and wrote him out of her will, got herself married to his younger brother. (After which the mother changed the will again, off course.) I'd not be amazed if Martin Jr. - perhaps even with this novel in the back of his head, Austen was quite popular with the male audience too - watched how Mary would react now it appears to be Pecksniff who'd inherit, and now he proposed to her. She'd seem to be able to secure her future by marriage, would she take it, or would she remain constant? In onther words: did she get engaged with Martin Jr. for his future money, or for love? Her reaction might alter how everything will turn out in the end.

I'm glad Tom is free now, but I found the way it happened a bit quick and easy as well. Perhaps it is because Mary brought in a different point of view, one he couldn't set aside as banter of young men, a realization he couldn't combine her virtue and Pecksniff's, and she'd have nothing to gain by lies. Perhaps it is because he just told her how every single one person who lived in Pecksniff's house thought badly of Pecksniff, added to her story, and it made him realize these all weren't isolated cases? Still, the turn was very, very quick and oh so convenient.

Jantine wrote: "I still find Pecksniff funny in a way, but it's in a very, very creepy way. Imagine being so dependent on someone who is - or appears to be? I wouldn't put it past Martin Sr. to play this out to 't..."

Jantine wrote: "I still find Pecksniff funny in a way, but it's in a very, very creepy way. Imagine being so dependent on someone who is - or appears to be? I wouldn't put it past Martin Sr. to play this out to 't..."Jantine, I wrote in my notes that these chapters reminded me of Austen, too! In chapter 32 when Mr. Moodle realizes he wants to propose to Cherry, the language and situation reminded me of minor characters in an Austen novel:

"In short, Mr Moddle began to be impressed with the idea that Miss Pecksniff’s mission was to comfort him; and Miss Pecksniff began to speculate on the probability of its being her mission to become ultimately Mrs Moddle. He was a young gentleman (Miss Pecksniff was not a very young lady) with rising prospects, and ‘almost’ enough to live on. Really it looked very well."

To me, the humorous tone and the sarcasm of this passage was certainly influenced by Austen.

While reading chapter 30, I found myself wanting to return to an early conversation the group had regarding Mary and Martin Senior’s relationship. We discussed whether or not Marin actually owes Mary anything after his death, or if her wages are recompense enough. What are Martin Senior’s responsibilities towards Mary?

While reading chapter 30, I found myself wanting to return to an early conversation the group had regarding Mary and Martin Senior’s relationship. We discussed whether or not Marin actually owes Mary anything after his death, or if her wages are recompense enough. What are Martin Senior’s responsibilities towards Mary? This issue came up again in chapter 30. Martin Sr. admits that he may have inadvertently put Mary in a very precarious social position:

"‘True,’ he answered. ‘True. She need have some one interested in her. I did her wrong to train her as I did. Orphan though she was, she would have found some one to protect her whom she might have loved again. When she was a child, I pleased myself with the thought that in gratifying my whim of placing her between me and false-hearted knaves, I had done her a kindness. Now she is a woman, I have no such comfort. She has no protector but herself. I have put her at such odds with the world, that any dog may bark or fawn upon her at his pleasure. Indeed she stands in need of delicate consideration. Yes; indeed she does!’”

The truth of this is then emphasized in this same chapter when Pecksniff aggressively pursues Mary and she isn’t able to protect herself from his advances. Dickens seems to suggest that Chuzzlewit has done Mary a disservice, even if Chuzzlewit’s intentions were not malicious. Chuzzlewit will essentially leave Mary defenseless if he does not provide for her after his death (either with a small inheritance, or providing another situation for her).

Jantine wrote: "I still find Pecksniff funny in a way, but it's in a very, very creepy way. Imagine being so dependent on someone who is - or appears to be? I wouldn't put it past Martin Sr. to play this out to 't..."

Jantine

How right you are. Everyone who lived with or studied with Pecksniff has left or abandoned him or, like Mary, grown to dislike him intensely although she still lives in his home. Chuzzlewit senior is the lone exception. Has Dickens set up the readers for an epic battle between the two? Perhaps Dickens separated Pecksniff from everyone for another plot reason?

Jantine

How right you are. Everyone who lived with or studied with Pecksniff has left or abandoned him or, like Mary, grown to dislike him intensely although she still lives in his home. Chuzzlewit senior is the lone exception. Has Dickens set up the readers for an epic battle between the two? Perhaps Dickens separated Pecksniff from everyone for another plot reason?

Emma wrote: "Jantine wrote: "I still find Pecksniff funny in a way, but it's in a very, very creepy way. Imagine being so dependent on someone who is - or appears to be? I wouldn't put it past Martin Sr. to pla..."

Indeed, it reminded me of persuasion too! Benwick and Louisa *grins*

Indeed, it reminded me of persuasion too! Benwick and Louisa *grins*

Chapter 30

Chapter 30Pecksniff and Mary? Ickypoo!!!!

Someone draw a heart with a broken arrow through it. Check that. Have black bile ooze from it.

I love Victorian novels. Just walk up to someone you have only just met and declare your undying love, and the party of your affection will believe your every word, and possibly even swoon. Though I don't think Mary is the swooning type, I didn't think she was the crying type either. I thought she was made of stronger stuff.

"The architect was too much overcome to speak. He tried to drop a tear upon his patron's hand, but couldn't find the one in his dry distillery."

Another one of those classic Dickens' sentences. It can be said in a thousand different ways, but Dickens says it in this way, and it is both memorable and pleasing.

--------------------

PS: I think Charity is being honest in her confrontation with her father, who isn't being honest. I don't believe Charity was all that smitten with Jonas, although she may have enjoyed the attention. Her dignity more than her heart has been wounded, and she is far more furious about the former than the latter. And Charity shows good judgment in holding her father accountable for what happened to her. Charity may not have the best personality, but she isn't a fool, and it's good to see her defend her dignity to her father who we will soon see is a scoundrel of an especially dastardly kind.

PPS: Mary did not handle Pecksniff well at all. It shows she is used to taking orders. She should have refused to walk with him, and when he persisted threatened to tell everyone of his despicable behavior. Instead she gives him what he wants. 4 demertis for Mary. Many, many more for Pecksniff, although it doesn't really matter. He's already up to his cheeks in demerits.

I keep thinking what Natashya (The Idiot, Dostoevsky) would have done to Pecksniff. I have this image of Pecksniff running for dear life being chased by a furious woman with a horse whip raised over her head.

Jantine wrote: "I'm glad Tom is free now, but I found the way it happened a bit quick and easy as well."

Yes, Tom's awakening is definitely a very quick and sudden one, and I've been thinking about whether it is very likely for Tom to separate himself from all the illusions about his idol which he has held so dearly. Under normal circumstances, I'd say that Tom would cling more obstinately to his old beliefs, but there is one thing we should not forget: It is Mary, the woman Tom reveres, adores and loves, who incriminates Pecksniff - and Tom would hardly feel able to distrust her. Put Pecksniff in one scale, Mary in the other, and well ... the rest is physics ;-)

Yes, Tom's awakening is definitely a very quick and sudden one, and I've been thinking about whether it is very likely for Tom to separate himself from all the illusions about his idol which he has held so dearly. Under normal circumstances, I'd say that Tom would cling more obstinately to his old beliefs, but there is one thing we should not forget: It is Mary, the woman Tom reveres, adores and loves, who incriminates Pecksniff - and Tom would hardly feel able to distrust her. Put Pecksniff in one scale, Mary in the other, and well ... the rest is physics ;-)

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I keep thinking what Natashya (The Idiot, Dostoevsky) would have done to Pecksniff. I have this image of Pecksniff running for dear life being chased by a furious woman with a horse whip raised over her head."

A woman like Natashya would probably never find her way into one of Dickens's novels because the author himself would have been afraid of her. I think Dickens preferred those meek, saintly, serious women who are full of unambivalent virtue but lack everything else. I mean, take a look at Mary: She is hardly doing anything herself in that novel, and most of the time people do something to her: Martin the older (using her as a pawn in his game against his family), Martin the younger (having decided to marry her and to use her in order to show his independence from his grandfather), Pecksniff (pursuing her like a snake), Tom (adoring her). All she does is wait and endure, and when she opens her mouth (as in the scene with Tom), she sounds like a character on a melodrama stage rather than like a real woman. She is, all in all, another of Dickens's artistic failures in creating interesting female characters.

A woman like Natashya would probably never find her way into one of Dickens's novels because the author himself would have been afraid of her. I think Dickens preferred those meek, saintly, serious women who are full of unambivalent virtue but lack everything else. I mean, take a look at Mary: She is hardly doing anything herself in that novel, and most of the time people do something to her: Martin the older (using her as a pawn in his game against his family), Martin the younger (having decided to marry her and to use her in order to show his independence from his grandfather), Pecksniff (pursuing her like a snake), Tom (adoring her). All she does is wait and endure, and when she opens her mouth (as in the scene with Tom), she sounds like a character on a melodrama stage rather than like a real woman. She is, all in all, another of Dickens's artistic failures in creating interesting female characters.

Tristram,

Tristram,And what about Charity? She has taken a huge step towards independence, or at least that is how it looks. I'm now wondering how we will feel about her at the end of the novel. Could go either way.

Perhaps it is more the case that young women blessed with looks are poor little things in need of saving, like the Marys of the world, while women who are not so pleasing to the eye, like Mrs. Gamp and Charity, have more interesting personalities?

And what of Little Dorrit? What mold does she fit?

Chapter 31

Chapter 31Old Martin's change in attitude towards Pecksniff is unbelievable, and makes me think Dickens made an about turn early in this story like he did in the Curiosity Shop. There is no way the old Martin we met in the first chapters could become the Old Martin in this and the last chapter. That first Old Martin despised Pecksniff.

I'm very interested in what Charity does next and how she handles her newly demanded independence. Remember the first couple of chapters and how she worshipped her father? Things are happening. Things are changing? It's getting interesting.

Where, oh where, is Slime?

Chapter 32

Chapter 32This chapter was hilarious. Dickens can be so funny. Kissed her snuffers, indeed. But the courting was just sublime.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Tristram,

And what about Charity? She has taken a huge step towards independence, or at least that is how it looks. I'm now wondering how we will feel about her at the end of the novel. Could go e..."

Little Dorrit is definitely one of the countless passive heroines that Dickens seems to have adored so much. As to Charity, she seeks to be married but there's little doubt that for her, marriage will not mean the end to her independence and mastery, as it did for Merry. Setting her cap on that insignificant Mr. Moddle may be an emergency solution, there being no other prospective husband at hand, but it also shows that Charity wants to rule supreme as a wife.

Nevertheless, from a Victorian standpoint, the fact that she stays on her own at Mrs. Todgers's must have been more or less against social mores. The landlady is a chaperon, but still the entire house is full of single gentlemen.

And what about Charity? She has taken a huge step towards independence, or at least that is how it looks. I'm now wondering how we will feel about her at the end of the novel. Could go e..."

Little Dorrit is definitely one of the countless passive heroines that Dickens seems to have adored so much. As to Charity, she seeks to be married but there's little doubt that for her, marriage will not mean the end to her independence and mastery, as it did for Merry. Setting her cap on that insignificant Mr. Moddle may be an emergency solution, there being no other prospective husband at hand, but it also shows that Charity wants to rule supreme as a wife.

Nevertheless, from a Victorian standpoint, the fact that she stays on her own at Mrs. Todgers's must have been more or less against social mores. The landlady is a chaperon, but still the entire house is full of single gentlemen.

Hi guys, I'm going to try to post the illustrations as fast as I can. Sorry I haven't been able to read your comments, I haven't been able to read anything at all. I'll explain it all later (if I can) but right now I think I have about ten minutes to post what I need to before my computer dies once again. If you need to know more, Tristram can tell you. OK, here goes (I hope):

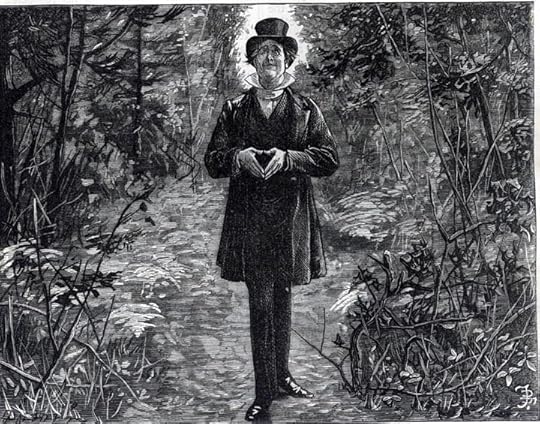

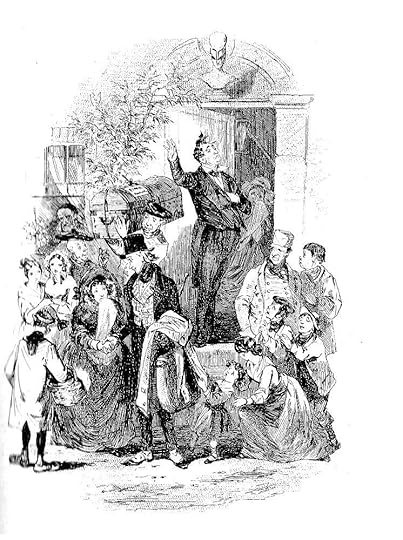

The Placid Pecksniff out for a stroll.

Chapter 30

Fred Barnard

Fred Barnard's thirty-fifth illustration for Martin Chuzzlewit in the Household Edition, the complacent and thoroughly self-assured Seth Pecksniff strolls as he determines to marry Old Martin's companion, Mary, and thereby become de facto heir to a vast estate.

Text Illustrated:

The summer weather in his bosom was reflected in the breast of Nature. Through deep green vistas where the boughs arched overhead, and showed the sunlight flashing in the beautiful perspective; through dewy fern from which the startled hares leaped up, and fled at his approach; by mantled pools, and fallen trees, and down in hollow places, rustling among last year’s leaves whose scent woke memory of the past; the placid Pecksniff strolled. By meadow gates and hedges fragrant with wild roses; and by thatched-roof cottages whose inmates humbly bowed before him as a man both good and wise; the worthy Pecksniff walked in tranquil meditation. The bee passed onward, humming of the work he had to do; the idle gnats for ever going round and round in one contracting and expanding ring, yet always going on as fast as he, danced merrily before him; the colour of the long grass came and went, as if the light clouds made it timid as they floated through the distant air. The birds, so many Pecksniff consciences, sang gayly upon every branch; and Mr Pecksniff paid his homage to the day by ruminating on his projects as he walked along.

The Placid Pecksniff out for a stroll.

Chapter 30

Fred Barnard

Fred Barnard's thirty-fifth illustration for Martin Chuzzlewit in the Household Edition, the complacent and thoroughly self-assured Seth Pecksniff strolls as he determines to marry Old Martin's companion, Mary, and thereby become de facto heir to a vast estate.

Text Illustrated:

The summer weather in his bosom was reflected in the breast of Nature. Through deep green vistas where the boughs arched overhead, and showed the sunlight flashing in the beautiful perspective; through dewy fern from which the startled hares leaped up, and fled at his approach; by mantled pools, and fallen trees, and down in hollow places, rustling among last year’s leaves whose scent woke memory of the past; the placid Pecksniff strolled. By meadow gates and hedges fragrant with wild roses; and by thatched-roof cottages whose inmates humbly bowed before him as a man both good and wise; the worthy Pecksniff walked in tranquil meditation. The bee passed onward, humming of the work he had to do; the idle gnats for ever going round and round in one contracting and expanding ring, yet always going on as fast as he, danced merrily before him; the colour of the long grass came and went, as if the light clouds made it timid as they floated through the distant air. The birds, so many Pecksniff consciences, sang gayly upon every branch; and Mr Pecksniff paid his homage to the day by ruminating on his projects as he walked along.

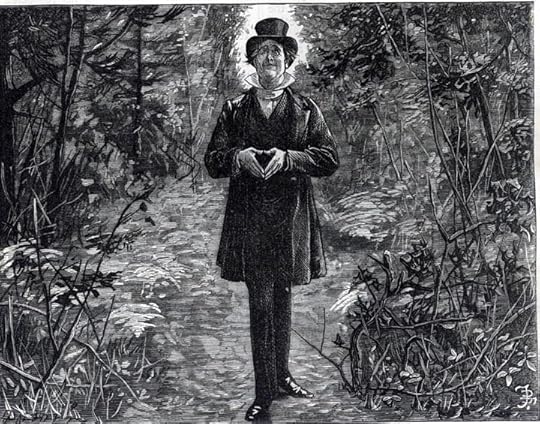

'Mr. Pecksniff's Courtship

Chapter 30

Sir John Gilbert

1863

Text Illustrated:

"I am glad we met. I am very glad we met. I am able now to ease my bosom of a heavy load, and speak to you in confidence. Mary," said Mr. Pecksniff in his tenderest tones, indeed they were so very tender that he almost squeaked: "My soul! I love you!"

A fantastic thing, that maiden affectation! She made believe to shudder.

"I love you," said Mr Pecksniff, "my gentle life, with a devotion which is quite surprising, even to myself. I did suppose that the sensation was buried in the silent tomb of a lady, only second to you in qualities of the mind and form; but I find I am mistaken."

She tried to disengage her hand, but might as well have tried to free herself from the embrace of an affectionate boa-constrictor; if anything so wily may be brought into comparison with Pecksniff.

"Although I am a widower," said Mr Pecksniff, examining the rings upon her fingers, and tracing the course of one delicate blue vein with his fat thumb, "a widower with two daughters, still I am not encumbered, my love. One of them, as you know, is married. The other, by her own desire, but with a view, I will confess — why not? — to my altering my condition, is about to leave her father's house. I have a character, I hope. People are pleased to speak well of me, I think. My person and manner are not absolutely those of a monster, I trust. Ah! naughty Hand!" said Mr Pecksniff, apostrophizing the reluctant prize, "why did you take me prisoner? Go, go!"

He slapped the hand to punish it; but relenting, folded it in his waistcoat to comfort it again.

Commentary:

In selecting his subjects for the four frontispieces for the four volumes in the American "Household Edition" of the early 1860s, Gilbert had merely to consider the original forty monthly illustrations by Dickens's graphic collaborator, Phiz, that is, Hablot Knight Browne. Among the incidents which occur within the scope of volume three (chapters 26 through 39), the farcical marriage proposal which the decidedly unromantic Seth Pecksniff makes to an obviously reluctant Mary Graham was an excellent choice for illustration because of its inherent physical conflict and ironic humour: that Pecksniff could ever love anybody but himself is patent nonsense, and that an intelligent young woman would find him desirable as a husband absurd. Moreover, the arboreal setting give the realist an opportunity to demonstrate his technical skill at depicting vegetation, the idyllic woodland setting serving to remind the reader of Mary's other lover, the devoted Martin, presently trapped in quite another sort of forest altogether.

However, Although he is successful at conveying both Mary's fashion sense, beauty, and reluctance, Gilbert does not rise to the comic possibilities that Dickens has offered him in Seth Pecksniff's sheer obtuseness. The persuasive voice and oily manner of the arch-hypocrite are inadequately presented in Gilbert's image of Pecksniff as a successful, well-dressed bourgeois of middle age. Although Gilbert's middle-aged professional man is self-assured, he is not funny, so that the reader delights more in the sheen of Mary's silk shawl than in Pecksniff's unconscious imitation of Satan accosting and attempting to seduce Eve in Paradise. Having achieved a satisfactory realisation of the glade in which Pecksniff encounters Mary, Gilbert has elaborated upon the text in terms of the figures' fashionable attire, but has almost entirely failed to realize the scene's verbal, physical, and character comedy. He does, however, set up expectations in the reader that Pecksniff's greed will induce him to pursue Mary romantically in hopes of ingratiating himself with Old Martin. The proleptic reading of the illustration does not include apprehensions about Mary's safety or the possibility of sexual violation, however, since to the reader already familiar with his character from volume one Pecksniff is hardly representative of the Victorian type known as the masher.

Whereas for chapter thirty-one, Phiz's twenty-fifth illustration (for the twelfth monthly instalment, December 1843), Mr. Pecksniff Discharges a Duty. . ., depicts the hypocritical Pecksniff discharging Tom Pinch with assumed hauteur and injured innocence, there is no plate in the original series which exploits the comic possibilities of showing Pecksniff in love — or, at least, his proposing to Mary. For such a scene, one must consult the Household Edition (1871-79) illustration for chapter thirty entitled (in an anticipation of French novel Marcel Proust, 1871-1922) Rustling among last year's leaves, whose scent woke memory of the past. . .; however, Fred Barnard does not specifically depict the meeting of Mary Graham and complacent, self-loving Pecksniff; rather, he satirically places a halo around the beaming, angelic countenance to expose his fatuousness. As is the case with Gilbert's 1863 illustration, Barnard frames the clerical-looking figure with copious shrubbery, but he does not suggest or imply Mary Graham's presence.

In the Diamond Edition of 1867, Sol Eytinge, Junior, depicts each character just once, so that Martin and Mark appear together as a team, and Pecksniff appears with his daughters Charity and Mercy rather than with Mary Graham, whom Eytinge pairs instead but quite plausibly with Old Martin, for whom she is both nurse and companion, in Old Martin and Mary. Appropriate to both the period and her social background, she wears more modest and less expensive clothing than Gilbert's harrassed heroine, but shares her intellectual gaze.

Since The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit was a nineteen-month serialisation, a sprawling narrative with a large cast of humorous characters, it was not especially well suited to Gilbert's sober and realistic style. However, with its caricatures directed at the exposure of hypocrisy on two continents and in two societies, it was the ideal vehicle for the comic genius and Expressionistic style of Dickens's last great Victorian illustrator, Harry Furniss. His studies of Seth Pecksniff in particular reveal the hyperbolic character's fatuous and self-aggrandizing nature, whether he is posturing before the crowd at the laying of the foundation stone in chapter thirty-five, asserting his leadership of the Chuzzlewits in chapter four, dismissing Tom Pinch in chapter thirty-one, or introducing his daughters to the recently arrived Young Martin in chapter five; in total, Furniss depicts the pious fraud seven times in twenty-nine illustrations in the Charles Dickens Library Edition. His most impressionistic and least detailed representation is Mr. Pecksniff Makes Love in chapter thirty. The sheer energy of Furniss's pen communicates a power beyond what mere detail alone can communicate, so that Mary's discomfort amounting distaste effectively complements the leering, jowled visage of Pecksniff, who gazes upon her diminutive figure like a boa-constrictor upon its prey. To reinforce Dickens's description of Pecksniff as such a snake, her agitated skirt and shawl and the tree branches above her, in their sinuous movements suggest her entrapment by just such a creature.

In Gilbert's third frontispiece for the 1863 American edition of the novel, one has less sense of the comic possibilities in the almost photographic image of Pecksniff improbably "making love" and proposing to Mary than one receives in Furniss's handling of precisely the same subject.

Mr. Pecksniff makes love

Chapter 30

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

"I am glad we met. I am very glad we met. I am able now to ease my bosom of a heavy load, and speak to you in confidence. Mary," said Mr. Pecksniff in his tenderest tones, indeed they were so very tender that he almost squeaked: "My soul! I love you!"

A fantastic thing, that maiden affectation! She made believe to shudder.

"I love you," said Mr Pecksniff, "my gentle life, with a devotion which is quite surprising, even to myself. I did suppose that the sensation was buried in the silent tomb of a lady, only second to you in qualities of the mind and form; but I find I am mistaken."

She tried to disengage her hand, but might as well have tried to free herself from the embrace of an affectionate boa-constrictor; if anything so wily may be brought into comparison with Pecksniff.

"Although I am a widower," said Mr Pecksniff, examining the rings upon her fingers, and tracing the course of one delicate blue vein with his fat thumb, "a widower with two daughters, still I am not encumbered, my love. One of them, as you know, is married. The other, by her own desire, but with a view, I will confess — why not? — to my altering my condition, is about to leave her father's house. I have a character, I hope. People are pleased to speak well of me, I think. My person and manner are not absolutely those of a monster, I trust. Ah! naughty Hand!" said Mr Pecksniff, apostrophizing the reluctant prize, "why did you take me prisoner? Go, go!"

He slapped the hand to punish it; but relenting, folded it in his waistcoat to comfort it again.

Commentary:

Although Dickens's original illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne, depicted the hypocritical Pecksniff in a number of situations in which he dons the robe of disinterested virtue, readers in America had to wait until the Sheldon and Company Household Edition to see a graphic representation of Pecksniff's ill-conceived courtship of Mary Graham. Comparable as an image of sublime fatuousness is the Fred Barnard illustration in the Household Edition Rustling among last year's leaves, whose scent woke memory of the past, the placid Pecksniff strolled (1872).

In selecting their subjects for the four frontispieces for the four volumes in the American "Household Edition" started in the early 1860s, Felix Darley and John Gilbert had merely to consider the original forty monthly illustrations by Dickens's graphic collaborator, Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne). An additional source of excellent comic material in a more realistic manner that Harry Furniss would have found useful for possible models occurs in Fred Barnard's fifty-nine large-scale wood-engravings for the Anglo-American Household Edition of the 1870s. Certainly, the hypocritical, egotistical Seth Pecksniff affords many opportunities for the illustrator; among the most suitable incidents for character and situational comedy is the farcical marriage proposal which the decidedly unromantic (but thoroughly materialistic) Pecksniff makes to an obviously reluctant Mary Graham was an excellent choice for John Gilbert in Sheldon and Company "Household" Edition of the 1860s. The scene is ideal for illustration because of its inherent physical conflict and ironic humour: that Pecksniff could ever love anybody but himself is patent nonsense, and that an intelligent young woman would find him desirable as a husband absurd. Moreover, the arboreal setting gives the realist an opportunity to demonstrate his technical skill at depicting vegetation, the idyllic woodland setting serving to remind the reader of Mary's other lover, the devoted Martin, presently trapped in quite another sort of forest altogether.

In the third frontispiece for the 1863 American edition of the novel, one has less sense of the comic possibilities in the almost photographic image of Pecksniff improbably "making love" and proposing to Mary than one receives in Furniss's handling of precisely the same subject. However, although he is successful at conveying both Mary's fashion sense, beauty, and reluctance in Mr. Pecksniff's Courtship (1863), Gilbert does not rise to the comic possibilities that Dickens has offered him in Seth Pecksniff's sheer obtuseness, whereas Phiz, Barnard, and Furniss convey his hypocrisy and realise his comic possibilities. Although Gilbert's middle-aged professional man is self-assured, he is not funny, so that the reader delights more in the sheen of Mary's silk shawl than in Pecksniff's unconscious imitation of Satan as he accosted and attempted to seduce Eve to evil in Paradise.

Since The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit was a nineteen-month serialisation, a sprawling, transAtlantic narrative with a large cast of humorous characters, it was not especially well suited to Gilbert's sober and realistic style. However, with its caricatures directed at the exposure of folly and hypocrisy on two continents and in two societies, it was the ideal vehicle for the comic genius and Expressionistic style of Dickens's last great Victorian illustrator, Harry Furniss. His studies of Seth Pecksniff in particular reveal the hyperbolic character's fatuous, unctuous, and self-aggrandizing nature, whether he is posturing before the crowd at the laying of the foundation stone in chapter thirty-five, asserting his leadership of the Chuzzlewits in the fourth chapter, dismissing Tom Pinch in chapter thirty-one, or introducing his daughters to the recently arrived Young Martin in chapter five — in total, Furniss depicts the pious fraud seven times in twenty-nine illustrations in the Charles Dickens Library Edition. His most impressionistic and least detailed representation is Mr. Pecksniff Makes Love in chapter thirty. The sheer energy of Furniss's pen communicates a power beyond what mere detail alone can communicate, so that Mary's discomfort amounting distaste effectively complements the leering, jowled visage of Pecksniff, who gazes upon her diminutive figure like a boa-constrictor upon its prey. To reinforce Dickens's description of Pecksniff as such a snake, her agitated skirt and shawl and the tree branches above her, in their sinuous movements suggest her entrapment by just such a creature.

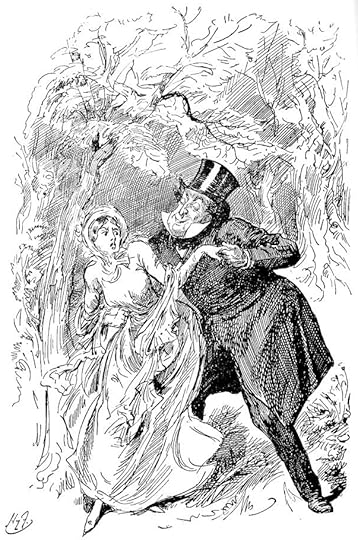

He is a scoundrel and a villain! I don't care who he is

Chapter 31

Fred Barnard

In the thirty-seventh illustration by Fred Barnard, Tom Pinch deounces the duplicity of his devious employer, who, unbeknownst to them, is overhearing everything from the church pews, having fallen asleep there. The dismissal of Tom precipitates his departure for London.

Text Illustrated:

‘Well, I don’t know how it is, but it always happens, whenever I express myself in this way to anybody almost, that I find they won’t do justice to Pecksniff. It is one of the most extraordinary circumstances that ever came within my knowledge, but it is so. There’s John Westlock, who used to be a pupil here, one of the best-hearted young men in the world, in all other matters—I really believe John would have Pecksniff flogged at the cart’s tail if he could. And John is not a solitary case, for every pupil we have had in my time has gone away with the same inveterate hatred of him. There was Mark Tapley, too, quite in another station of life,’ said Tom; ‘the mockery he used to make of Pecksniff when he was at the Dragon was shocking. Martin too: Martin was worse than any of ‘em. But I forgot. He prepared you to dislike Pecksniff, of course. So you came with a prejudice, you know, Miss Graham, and are not a fair witness.’

Tom triumphed very much in this discovery, and rubbed his hands with great satisfaction.

‘Mr Pinch,’ said Mary, ‘you mistake him.’

‘No, no!’ cried Tom. ‘You mistake him. But,’ he added, with a rapid change in his tone, ‘what is the matter? Miss Graham, what is the matter?’

Mr Pecksniff brought up to the top of the pew, by slow degrees, his hair, his forehead, his eyebrow, his eye. She was sitting on a bench beside the door with her hands before her face; and Tom was bending over her.

‘What is the matter?’ cried Tom. ‘Have I said anything to hurt you? Has any one said anything to hurt you? Don’t cry. Pray tell me what it is. I cannot bear to see you so distressed. Mercy on us, I never was so surprised and grieved in all my life!’

Mr Pecksniff kept his eye in the same place. He could have moved it now for nothing short of a gimlet or a red-hot wire.

‘I wouldn’t have told you, Mr Pinch,’ said Mary, ‘if I could have helped it; but your delusion is so absorbing, and it is so necessary that we should be upon our guard; that you should not be compromised; and to that end that you should know by whom I am beset; that no alternative is left me. I came here purposely to tell you, but I think I should have wanted courage if you had not chanced to lead me so directly to the object of my coming.’

Tom gazed at her steadfastly, and seemed to say, ‘What else?’ But he said not a word.

‘That person whom you think the best of men,’ said Mary, looking up, and speaking with a quivering lip and flashing eye.

‘Lord bless me!’ muttered Tom, staggering back. ‘Wait a moment. That person whom I think the best of men! You mean Pecksniff, of course. Yes, I see you mean Pecksniff. Good gracious me, don’t speak without authority. What has he done? If he is not the best of men, what is he?’

‘The worst. The falsest, craftiest, meanest, cruellest, most sordid, most shameless,’ said the trembling girl—trembling with her indignation.

Tom sat down on a seat, and clasped his hands.

‘What is he,’ said Mary, ‘who receiving me in his house as his guest; his unwilling guest; knowing my history, and how defenceless and alone I am, presumes before his daughters to affront me so, that if I had a brother but a child, who saw it, he would instinctively have helped me?’

‘He is a scoundrel!’ exclaimed Tom. ‘Whoever he may be, he is a scoundrel.’

Mr Pecksniff dived again.

‘What is he,’ said Mary, ‘who, when my only friend—a dear and kind one, too—was in full health of mind, humbled himself before him, but was spurned away (for he knew him then) like a dog. Who, in his forgiving spirit, now that that friend is sunk into a failing state, can crawl about him again, and use the influence he basely gains for every base and wicked purpose, and not for one—not one—that’s true or good?’

‘I say he is a scoundrel!’ answered Tom.

‘But what is he—oh, Mr Pinch, what is he—who, thinking he could compass these designs the better if I were his wife, assails me with the coward’s argument that if I marry him, Martin, on whom I have brought so much misfortune, shall be restored to something of his former hopes; and if I do not, shall be plunged in deeper ruin? What is he who makes my very constancy to one I love with all my heart a torture to myself and wrong to him; who makes me, do what I will, the instrument to hurt a head I would heap blessings on! What is he who, winding all these cruel snares about me, explains their purpose to me, with a smooth tongue and a smiling face, in the broad light of day; dragging me on, the while, in his embrace, and holding to his lips a hand,’ pursued the agitated girl, extending it, ‘which I would have struck off, if with it I could lose the shame and degradation of his touch?’

‘I say,’ cried Tom, in great excitement, ‘he is a scoundrel and a villain! I don’t care who he is, I say he is a double-dyed and most intolerable villain!’

Covering her face with her hands again, as if the passion which had sustained her through these disclosures lost itself in an overwhelming sense of shame and grief, she abandoned herself to tears.

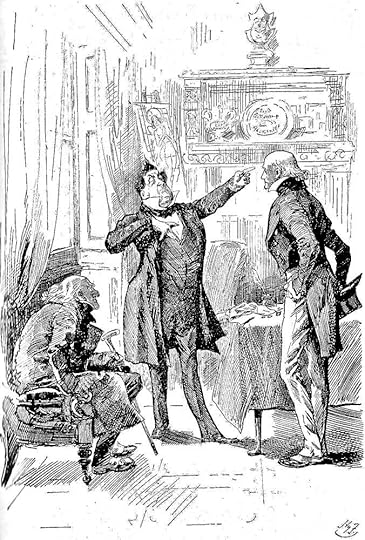

Mr. Pecksniff Discharges a Duty Which He Owes to Society

Chapter 31

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

There were several people, young and old, standing about the door, some of whom cried with Mrs Lupin; while others tried to keep up a stout heart, as Tom did; and others were absorbed in admiration of Mr. Pecksniff — a man who could build a church, as one may say, by squinting at a sheet of paper; and others were divided between that feeling and sympathy with Tom. Mr. Pecksniff had appeared on the top of the steps, simultaneously with his old pupil, and while Tom was talking with Mrs. Lupin kept his hand stretched out, as though he said "Go forth!" When Tom went forth, and had turned the corner Mr. Pecksniff shook his head, shut his eyes, and heaving a deep sigh, shut the door. On which, the best of Tom’s supporters said he must have done some dreadful deed, or such a man as Mr. Pecksniff never could have felt like that. If it had been a common quarrel (they observed), he would have said something, but when he didn’t, Mr. Pinch must have shocked him dreadfully. [Chapter XXXI]

Commentary:

This illustration’s composition and focus on Pecksniff recalls the architect's quest for Mrs. Gamp in Part VIII, ch. 19, "Mr. Pecksniff on his mission" (August, 1843). However, whereas the large chiefly female and largely unsympathetic crowd in the former scene put Pecksniff at a disadvantage, here he is firmly in control of the situation, as his commanding gesture of dismissal and Napoleonic pose suggest. In describing Tom Pinch's departure from Pecksniff's, Phiz combines two related moments from the text: in the first, Tom stands in the foreground, coat and carpet-bag in his left hand, at the bottom of the steps alongside the tearful Mrs. Lupin; in the second, further down the page, "Mr. Pecksniff had appeared on the top of the steps, simultaneously with his old pupil, and while Tom was talking with Mrs. Lupin kept his hand stretched out, as though he said 'Go forth!' (ch. 31).

The picture's subject, the departure of a community figure for the great world beyond the village, recalls that of the plate complementing ch. 7 in which Mark Tapley dressed as a countryman strikes off for Salisbury, and thence for London. Mark, unencumbered by trunks, feigns jollity, and likewise here Tom, respectably clad in middle-class fashion, tries "to keep up a stout heart." However, whereas the entire village seems sad to see Mark leave, Pecksniff (in sharp contrast to the sobbing Jane in the doorway) is unmoved by the general display of sentiment, and the villagers to the right seem inclined to take Pecksniff's part. Recalling the child who is upset by Mark's departure in the earlier illustration, here Phiz has inserted a child tugging at Tom's great-coat, as if forcibly trying to prevent him from leaving. Having at last discovered for himself what a humbug Pecksniff is, Tom ignores him in the plate as in the text rather than attempting to defend himself; his calm demeanour is as genuine as Pecksniff's self-righteous hauteur is contrived. Phiz communicates Pecksniff stagey attempt to take the moral high ground by his elevated position at the top of the steps. The removal man from The Dragon (who bears Tom's box out of the house as if it were a coffin containing his happy memories and erstwhile good opinions of his former employer) connects the two principals of the illustration. The flourishing tree above Tom and his trunk signifies not merely the time of year but Tom's fair promise of success in the great world beyond the little village on the Salisbury Plain. Tom's progress physically, emotionally, and morally has now begun.

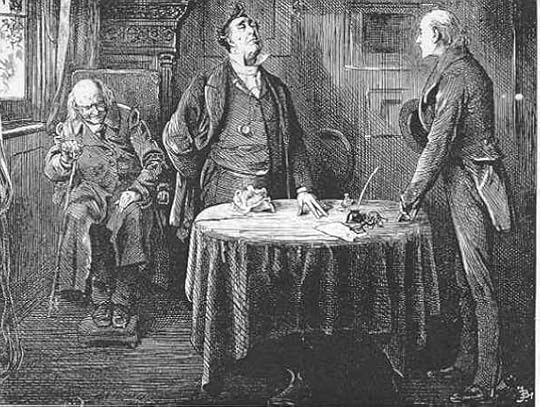

Tom Pinch fired

Chapter 31

Fred Barnard

In Barnard's illustration for Chapter 31 with Old Martin (left) and Seth Pecksniff (center), Tom Pinch is fired after years of devoted service. (Lucky him)

Text Illustrated:

When Tom came back, he found old Martin sitting by the window, and Mr Pecksniff in an imposing attitude at the table. On one side of him was his pocket-handkerchief; and on the other a little heap (a very little heap) of gold and silver, and odd pence. Tom saw, at a glance, that it was his own salary for the current quarter.

‘Have you fastened the vestry-window, Mr Pinch?’ said Pecksniff.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Thank you. Put down the keys if you please, Mr Pinch.’

Tom placed them on the table. He held the bunch by the key of the organ-loft (though it was one of the smallest), and looked hard at it as he laid it down. It had been an old, old friend of Tom’s; a kind companion to him, many and many a day.

‘Mr Pinch,’ said Pecksniff, shaking his head; ‘oh, Mr Pinch! I wonder you can look me in the face!’

Tom did it though; and notwithstanding that he has been described as stooping generally, he stood as upright then as man could stand.

‘Mr Pinch,’ said Pecksniff, taking up his handkerchief, as if he felt that he should want it soon, ‘I will not dwell upon the past. I will spare you, and I will spare myself, that pain at least.’

Tom’s was not a very bright eye, but it was a very expressive one when he looked at Mr Pecksniff, and said:

‘Thank you, sir. I am very glad you will not refer to the past.’

‘The present is enough,’ said Mr Pecksniff, dropping a penny, ‘and the sooner that is past, the better. Mr Pinch, I will not dismiss you without a word of explanation. Even such a course would be quite justifiable under the circumstances; but it might wear an appearance of hurry, and I will not do it; for I am,’ said Mr Pecksniff, knocking down another penny, ‘perfectly self-possessed. Therefore I will say to you, what I have already said to Mr Chuzzlewit.’

Tom glanced at the old gentleman, who nodded now and then as approving of Mr Pecksniff’s sentences and sentiments, but interposed between them in no other way.

‘From fragments of a conversation which I overheard in the church, just now, Mr Pinch,’ said Pecksniff, ‘between yourself and Miss Graham—I say fragments, because I was slumbering at a considerable distance from you, when I was roused by your voices—and from what I saw, I ascertained (I would have given a great deal not to have ascertained, Mr Pinch) that you, forgetful of all ties of duty and of honour, sir; regardless of the sacred laws of hospitality, to which you were pledged as an inmate of this house; have presumed to address Miss Graham with unreturned professions of attachment and proposals of love.’

Tom looked at him steadily.

‘Do you deny it, sir?’ asked Mr Pecksniff, dropping one pound two and fourpence, and making a great business of picking it up again.

‘No, sir,’ replied Tom. ‘I do not.’

‘You do not,’ said Mr Pecksniff, glancing at the old gentleman. ‘Oblige me by counting this money, Mr Pinch, and putting your name to this receipt. You do not?’

No, Tom did not. He scorned to deny it. He saw that Mr Pecksniff having overheard his own disgrace, cared not a jot for sinking lower yet in his contempt. He saw that he had devised this fiction as the readiest means of getting rid of him at once, but that it must end in that any way. He saw that Mr Pecksniff reckoned on his not denying it, because his doing so and explaining would incense the old man more than ever against Martin and against Mary; while Pecksniff himself would only have been mistaken in his ‘fragments.’ Deny it! No.

‘You find the amount correct, do you, Mr Pinch?’ said Pecksniff.

‘Quite correct, sir,’ answered Tom.

‘A person is waiting in the kitchen,’ said Mr Pecksniff, ‘to carry your luggage wherever you please. We part, Mr Pinch, at once, and are strangers from this time.’ (Tom Pinch should feel like it is Christmas day after that last comment, I would if I didn't already.)

The Dismissal of Tom Pinch

Harry Furniss

Chapter 31

"From fragments of a conversation which I overheard in the church, just now, Mr. Pinch," said Pecksniff, "between yourself and Miss Graham — I say fragments, because I was slumbering at a considerable distance from you, when I was roused by your voices — and from what I saw, I ascertained (I would have given a great deal not to have ascertained, Mr. Pinch) that you, forgetful of all ties of duty and of honour, sir; regardless of the sacred laws of hospitality, to which you were pledged as an inmate of this house; have presumed to address Miss Graham with un-returned professions of attachment and proposals of love."

Tom looked at him steadily.

"Do you deny it, sir?" asked Mr. Pecksniff, dropping one pound two and fourpence, and making a great business of picking it up again.

"No, sir," replied Tom. "I do not."

"You do not," said Mr. Pecksniff, glancing at the old gentleman. "Oblige me by counting this money, Mr. Pinch, and putting your name to this receipt. You do not?"

No, Tom did not. He scorned to deny it. He saw that Mr. Pecksniff having overheard his own disgrace, cared not a jot for sinking lower yet in his contempt. He saw that he had devised this fiction as the readiest means of getting rid of him at once, but that it must end in that any way. He saw that Mr. Pecksniff reckoned on his not denying it, because his doing so and explaining would incense the old man more than ever against Martin and against Mary: while Pecksniff himself would only have been mistaken in his "fragments." Deny it! No.

"You find the amount correct, do you, Mr. Pinch?" said Pecksniff. "Quite correct, sir," answered Tom.

"A person is waiting in the kitchen," said Mr. Pecksniff, "to carry your luggage wherever you please. We part, Mr. Pinch, at once, and are strangers from this time."

Something without a name; compassion, sorrow, old tenderness, mistaken gratitude, habit: none of these, and yet all of them; smote upon Tom's gentle heart at parting. There was no such soul as Pecksniff's in that carcase; and yet, though his speaking out had not involved the compromise of one he loved, he couldn't have denounced the very shape and figure of the man. Not even then.

"I will not say," cried Mr. Pecksniff, shedding tears, "what a blow this is. I will not say how much it tries me; how it works upon my nature; how it grates upon my feelings. I do not care for that. I can endure as well as another man. But what I have to hope, and what you have to hope, Mr. Pinch (otherwise a great responsibility rests upon you), is, that this deception may not alter my ideas of humanity; that it may not impair my freshness, or contract, if I may use the expression, my Pinions. I hope it will not; I don't think it will. It may be a comfort to you, if not now, at some future time, to know that I shall endeavour not to think the worse of my fellow-creatures in general, for what has passed between us. Farewell!"

Commentary:

In the Pecksniff parlour the architect denounces Tom in front of Old Martin, even as on the facing page Pecksniff, hiding in a church pew, overhears Mary Graham reveal his true character, much to Tom's shock and surprise. As in the text, Old Martin is sitting by the casement window, and Tom has returned from the church, where he has had to lock the casement window through which Pecksniff had exited the building after being locked in by Tom earlier. Adopting a pose of sorrowful indignation, Pecksniff pays him for his services with the coins on the table, accusing Tom of doing to Miss Graham what he himself had tried do, for he had "presumed to address Miss Graham with un-returned professions of attachment and proposals of love".

Furniss elects to realise the moment of Tom's dismissal in the parlour, rather than, as in the Phiz illustrations in the original serial, the apprentice's moment of departure on Pecksniff's steps in Mr. Pecksniff Discharges a Duty Which He Owes to Society (December 1843, Chapter 31). Whereas Fred Barnard in the Household Edition had dwelt upon the humorous aspects of Pecksniff's hypocritical behaviour here, Furniss treats the scene with grave solemnity as it presents the illustrator the opportunity to show Tom's stalwart and upright nature.

Pecksniff's theatricality and central position suggest that he dominates the scene, but Tom neither flinches nor retreats, standing his ground; meanwhile, Old Martin watches wordlessly, assessing the behaviour and character of each adversary. On a drawing-board behind the arch-hypocrite is a haloed angel or saint in a pious pose, underscoring Pecksniff's outward piety. The sideboard behind Tom and Pecksniff is surmounted by a bust of Pecksniff, implying his vanity and egotism. The substantial piece of furniture bears a loving-cup and rondel celebrating Pecksniff's character ("Good Fellowship, Pecksniff"), even as he reveals his true colours at last to Tom — and to Old Martin. In the plate, Tom's clenched left fist may imply his exercising restraint by not punching the humbug whom he has for years thought a good and decent employer. These are precisely the sorts of embedded details and commentary that Phiz was accustomed to employ in his illustrations, but that Fred Barnard and the other Seventies realists rejected.

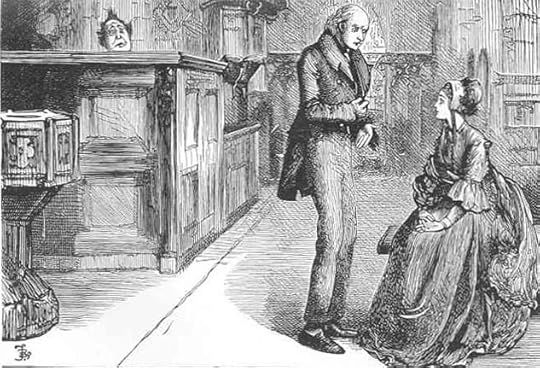

Mr. Moddle is Both Particular and Peculiar in his Attentions

Chapter 32

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Determining to regulate her conduct by this opinion, the young lady received Mr Moddle, on the earliest subsequent occasion, with an air of constraint; and gradually leading him to inquire, in a dejected manner, why she was so changed, confessed to him that she felt it necessary for their mutual peace and happiness to take a decided step. They had been much together lately, she observed, much together, and had tasted the sweets of a genuine reciprocity of sentiment. She never could forget him, nor could she ever cease to think of him with feelings of the liveliest friendship, but people had begun to talk, the thing had been observed, and it was necessary that they should be nothing more to each other, than any gentleman and lady in society usually are. She was glad she had had the resolution to say thus much before her feelings had been tried too far; they had been greatly tried, she would admit; but though she was weak and silly, she would soon get the better of it, she hoped.

Moddle, who had by this time become in the last degree maudlin, and wept abundantly, inferred from the foregoing avowal, that it was his mission to communicate to others the blight which had fallen on himself; and that, being a kind of unintentional Vampire, he had had Miss Pecksniff assigned to him by the Fates, as Victim Number One. Miss Pecksniff controverting this opinion as sinful, Moddle was goaded on to ask whether she could be contented with a blighted heart; and it appearing on further examination that she could be, plighted his dismal troth, which was accepted and returned. He bore his good fortune with the utmost moderation. Instead of being triumphant, he shed more tears than he had ever been known to shed before; and, sobbing, said:

‘Oh! what a day this has been! I can’t go back to the office this afternoon. Oh, what a trying day this has been! Good Gracious!’

Mrs. Todgers and Mr. Moddle

Chapter 32

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Commentary:

For his twelfth illustration of Martin Chuzzlewit, Eytinge depicted Mrs. Todgers, the owner of the London boarding-house where the Pecksniffs tend to stay when in town (e. g., in Part Four) and the youngest of her male lodgers, the disconsolate lover Augustus Moddle, who had fallen in love with Mercy ("Merry") Pecksniff and cannot completely permit her sister, Charity ("Cherry"), to displace the now Mrs. Chuzzlewit (Jonas's wife) in his affections. Introduced as early as chapter 9, Mr. Moddle, referred to only as "The youngest gentleman in company" (90) at that point, saves Pecksniff after the architect falls into the fireplace: Moddle "had him out in a second. Yes, before a hair upon his head was singed, he had him on the hearth-rug". Dickens's description of Mrs. Todgers in chapter 8 presumably influenced Eytinge's conception of her, especially with respect to her curls, although not her taste for finery implied in Phiz's April 1843 illustration, for Part Four (chapter 9):

M. Todgers was a lady — rather a bony and hard-featured lady — with a row of curls in front of her head, shaped like little barrels of beer; and on the top of it something made of net, — you couldn't call it a cap exactly, — which looked like a black cobweb. She had a little basket on her arm, and in it a bunch of keys that jingled as she came. [Chapter 8; Diamond Edition]

The kindly aspect of her disposition is not suggested in Eytinge's illustration, but her role as counsellor to the inmates of the boarding-house is well suggested by the illustration. The dialogue that Eytinge has in mind between Mrs. Todgers and Mr. Moddle occurs in the middle of the narrative, in chapter 32, when Charity has established herself at Mrs. Todgers's once again:

This was the only great change over and above the change which had fallen on the youngest gentleman. As for him, he more than corroborated the account of Mrs. Todgers; possessing greater sensibility than even she had given him credit for. He entertained some terrible notions of Destiny, among other matters, and talked much about people's 'Missions'; upon which he seemed to have some private information not generally attainable, as he knew it had been poor Merry's mission to crush him in the bud. He was very frail and tearful; for being aware that a shepherd's mission was to pipe to his flocks, and that a boatswain's mission was to pipe all hands, and that one man's mission was to be a paid piper, and another man's mission was to pay the piper, so he had got it into his head that his own peculiar mission was to pipe his eye. Which he did perpetually.

He often informed Mrs. Todgers that the sun had set upon him; that the billows had rolled over him; that the car of Juggernaut had crushed him, and also that the deadly Upas tree of Java had blighted him. His name was Moddle.

Towards this most unhappy Moddle, Miss Pecksniff conducted herself at first with distant haughtiness, being in no humour to be entertained with dirges in honour of her married sister. The poor young gentleman was additionally crushed by this, and remonstrated with Mrs. Todgers on the subject.

"Even she turns from me, Mrs. Todgers," said Moddle.

"Then why don't you try and be a little bit more cheerful, sir?" retorted Mrs Todgers.

"Cheerful, Mrs Todgers! cheerful!' cried the youngest gentleman; "when she reminds me of days for ever fled, Mrs. Todgers!"

"Then you had better avoid her for a short time, if she does,' said Mrs. Todgers, 'and come to know her again, by degrees. That's my advice."

"But I can't avoid her," replied Moddle, "I haven't strength of mind to do it. Oh, Mrs. Todgers, if you knew what a comfort her nose is to me!"

"Her nose, sir!" Mrs. Todgers cried.

"Her profile, in general," said the youngest gentleman, "but particularly her nose. It's so like," — here he yielded to a burst of grief, — "it's so like hers who is Another's, Mrs. Todgers!"

The observant matron did not fail to report this conversation to Charity, who laughed at the time, but treated Mr Moddle that very evening with increased consideration, and presented her side-face to him as much as possible. Mr. Moddle was not less sentimental than usual; was rather more so, if anything; but he sat and stared at her with glistening eyes, and seemed grateful.

"Well, sir!" said the lady of the boarding-house next day. 'You held up your head last night. You're coming round, I think."

"Only because she's so like her who is Another's, Mrs Todgers," rejoined the youth. "When she talks, and when she smiles, I think I'm looking on HER brow again, Mrs. Todgers."

Whereas Eytinge thought the proprietress of the commercial boarding-house worthy of visual comment, Barnard relegates her to a corner of a single illustration late in the narrative in the 1872 Household Edition. Phiz, on the other hand, seems to have been content to let the reader imagine his appearance and manner resulting from his suffering from "a blighted heart" until well into the story, when in the May 1844 number he shows a pallid youth in respectable, middle-class garb accompanying Charity on a shopping expedition to set them up in housekeeping. Certainly in his twelfth illustration Eytinge captures Moddle's depressive state.

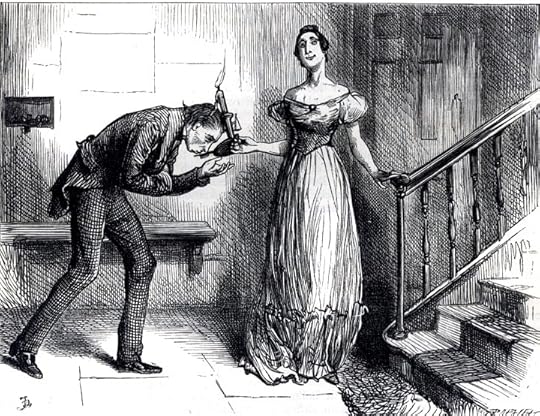

"On the fourteenth night, he kissed Miss Pecksniff's snuffers in the passage"

Chapter 32

Fred Barnard

In this illustration by Fred Barnard we see the physical comedy of the awkward courtship of Mr. Moddle and the elder, less comely Miss Pecksniff at Todger's boarding house.

Text Illustrated:

He often informed Mrs Todgers that the sun had set upon him; that the billows had rolled over him; that the car of Juggernaut had crushed him, and also that the deadly Upas tree of Java had blighted him. His name was Moddle.

Towards this most unhappy Moddle, Miss Pecksniff conducted herself at first with distant haughtiness, being in no humour to be entertained with dirges in honour of her married sister. The poor young gentleman was additionally crushed by this, and remonstrated with Mrs Todgers on the subject.

‘Even she turns from me, Mrs Todgers,’ said Moddle.

‘Then why don’t you try and be a little bit more cheerful, sir?’ retorted Mrs Todgers.