The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

MC Chapters 51-54

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 52

Following my last question of the previous chapter we find Dickens discussing the “cherished projects, so long hidden” at the beginning of this chapter. Does the first paragraph of this chapter settle easily in your mind?

We learn that old Martin had marshalled the aid of John Westlake, Mark Tapley, and Tom Pinch. Here we see the agents and forces of good become aligned. Old Martin did not reveal to these men his full plans, but did make them aware that they were gathering to be a force against Pecksniff. Old Chuzzlewit has summoned young Martin who was surprised to receive the news. Both Chuzzlewit’s have changed for the better as we have proceeded through the novel. The total reconciliation is upon us. In time, it seems that all the good characters in the novel come to old Martin’s place - Westlake, Tom Pinch and his sister, young Martin, Mary Graham, and Mrs Lupin.

Another set of footsteps is heard upon the stairs. It is Mr Pecksniff. Pecksniff looks around the room and immediately launches into an attack on one and all (with the exception of old Martin). As Pecksniff approaches old Martin to give him yet another snake-like embrace Martin Chuzzlewit stands and grasps a stick and beats Pecksniff to the ground. Next, Martin orders that Pecksniff be dragged away and taken out of his reach. Mark Tapley then physically drags Pecksniff to the corner of the room. Old Martin then passionately embraces his grandson. Old Martin then says that the deep curse of the family has been “the love of self.” He says he regards Mary as his daughter and is aware that Pecksniff had designed one of his daughters to be the future wife of young Martin. Meanwhile, Pecksniff listens to all this and snivels in the corner of the room.

We learn that the money young Martin received in town came from his grandfather. Old Martin confesses that money is a means of control and power, and that he was responsible for using money to such improper ends. Mark Tapley makes the astute observation that money does indeed change the character of many people and offers the example of Tigg Montague. With this comment we see how Dickens has indicated a character’s change in nature can often be seen with a change in their name and appearance.

Thoughts

Changes in a character form a large part of the format of this novel. We have the Montague-Tigg/Tigg-Montague example as well as Jonas Chuzzlewit’s change of clothes, Mrs Gamp and her imaginary friend Mrs Harris, and the twin Chuzzlewit names. Can you think of others? How effective a technique do you find this style and format of plot and character?

Were you at all surprised at the fact that with the assembled good characters we see Pecksniff being hit by old Martin Chuzzlewit? Was it an appropriate punishment?

We learn that on the evening of old Martin’s illness at the Dragon he wrote a letter to young Martin and made him his heir and sanctioned the marriage with Mary. Old Martin recounts how good Tom Pinch was to him. We learn how old Martin on learning that Tom was sent packing by Pecksniff contacted John Westlock and set up the job for Tom in London. Old Martin tells the group that Tom was always honourable in his attentions towards Mary and that Mrs Lupin acted as a duenna for Mary. With this, young Martin apologizes to Tom for mistrusting him. Tom graciously accepts Martin’s words.

Thoughts

Many bits of the puzzle are beginning to be fit into place. It is apparent that old Martin Chuzzlewit has been a puppet master throughout most of the novel. What is your response to his comments?

Ah, the name changes continue. We learn that Mrs Tapley and Mark are to be married but she will not change her name. What will change will be the name of the Inn which will from this point forward be called the Jolly Tapley. Amazing, or not, Pecksniff maintains his gentlemanly hypocrisy and, as he surveys the room, claims that there is no one in the room who has not deceived him. He admits that he has through an “unfortunate speculation, combined with treachery” now finds himself in poverty. Pecksniff then departs the room. As he departs, Sweedlepipe and Mrs Gamp enter the crowded room. A busy place, this room. Sweedlepipe cries out “Is there anybody here that knows him?” This question is followed by “something in top-boots, with its head bandaged up [ who] staggered into the room.” It’s Bailey! He is alive and Sweedlepipe intends to go into business with Bailey. As for Mrs Gamp, she is to remain a lodger with Sweedlepipe. Old Martin suggests that Mrs Gamp be a bit more honest and a bit less thirsty in the future. As our chapter comes to an end old Martin walks arm-in-arm with Tom as do John Westlake and Ruth to an unnamed engagement.

Thoughts

Dickens is rapidly wrapping up our novel. Bailey is alive. Sweedlepipe now has a new business partner. Tom and young Martin are fully reconciled. Mrs Gamp will always be Mrs Gamp, I imagine, regardless of old Martin's comments. Mark and Mrs Lupin are happily in love as are Ruth and John and Martin and Ruth. And Pecksniff, I fear he will always be in love with himself. What is your response to this chapter of revelation and recognition?

Following my last question of the previous chapter we find Dickens discussing the “cherished projects, so long hidden” at the beginning of this chapter. Does the first paragraph of this chapter settle easily in your mind?

We learn that old Martin had marshalled the aid of John Westlake, Mark Tapley, and Tom Pinch. Here we see the agents and forces of good become aligned. Old Martin did not reveal to these men his full plans, but did make them aware that they were gathering to be a force against Pecksniff. Old Chuzzlewit has summoned young Martin who was surprised to receive the news. Both Chuzzlewit’s have changed for the better as we have proceeded through the novel. The total reconciliation is upon us. In time, it seems that all the good characters in the novel come to old Martin’s place - Westlake, Tom Pinch and his sister, young Martin, Mary Graham, and Mrs Lupin.

Another set of footsteps is heard upon the stairs. It is Mr Pecksniff. Pecksniff looks around the room and immediately launches into an attack on one and all (with the exception of old Martin). As Pecksniff approaches old Martin to give him yet another snake-like embrace Martin Chuzzlewit stands and grasps a stick and beats Pecksniff to the ground. Next, Martin orders that Pecksniff be dragged away and taken out of his reach. Mark Tapley then physically drags Pecksniff to the corner of the room. Old Martin then passionately embraces his grandson. Old Martin then says that the deep curse of the family has been “the love of self.” He says he regards Mary as his daughter and is aware that Pecksniff had designed one of his daughters to be the future wife of young Martin. Meanwhile, Pecksniff listens to all this and snivels in the corner of the room.

We learn that the money young Martin received in town came from his grandfather. Old Martin confesses that money is a means of control and power, and that he was responsible for using money to such improper ends. Mark Tapley makes the astute observation that money does indeed change the character of many people and offers the example of Tigg Montague. With this comment we see how Dickens has indicated a character’s change in nature can often be seen with a change in their name and appearance.

Thoughts

Changes in a character form a large part of the format of this novel. We have the Montague-Tigg/Tigg-Montague example as well as Jonas Chuzzlewit’s change of clothes, Mrs Gamp and her imaginary friend Mrs Harris, and the twin Chuzzlewit names. Can you think of others? How effective a technique do you find this style and format of plot and character?

Were you at all surprised at the fact that with the assembled good characters we see Pecksniff being hit by old Martin Chuzzlewit? Was it an appropriate punishment?

We learn that on the evening of old Martin’s illness at the Dragon he wrote a letter to young Martin and made him his heir and sanctioned the marriage with Mary. Old Martin recounts how good Tom Pinch was to him. We learn how old Martin on learning that Tom was sent packing by Pecksniff contacted John Westlock and set up the job for Tom in London. Old Martin tells the group that Tom was always honourable in his attentions towards Mary and that Mrs Lupin acted as a duenna for Mary. With this, young Martin apologizes to Tom for mistrusting him. Tom graciously accepts Martin’s words.

Thoughts

Many bits of the puzzle are beginning to be fit into place. It is apparent that old Martin Chuzzlewit has been a puppet master throughout most of the novel. What is your response to his comments?

Ah, the name changes continue. We learn that Mrs Tapley and Mark are to be married but she will not change her name. What will change will be the name of the Inn which will from this point forward be called the Jolly Tapley. Amazing, or not, Pecksniff maintains his gentlemanly hypocrisy and, as he surveys the room, claims that there is no one in the room who has not deceived him. He admits that he has through an “unfortunate speculation, combined with treachery” now finds himself in poverty. Pecksniff then departs the room. As he departs, Sweedlepipe and Mrs Gamp enter the crowded room. A busy place, this room. Sweedlepipe cries out “Is there anybody here that knows him?” This question is followed by “something in top-boots, with its head bandaged up [ who] staggered into the room.” It’s Bailey! He is alive and Sweedlepipe intends to go into business with Bailey. As for Mrs Gamp, she is to remain a lodger with Sweedlepipe. Old Martin suggests that Mrs Gamp be a bit more honest and a bit less thirsty in the future. As our chapter comes to an end old Martin walks arm-in-arm with Tom as do John Westlake and Ruth to an unnamed engagement.

Thoughts

Dickens is rapidly wrapping up our novel. Bailey is alive. Sweedlepipe now has a new business partner. Tom and young Martin are fully reconciled. Mrs Gamp will always be Mrs Gamp, I imagine, regardless of old Martin's comments. Mark and Mrs Lupin are happily in love as are Ruth and John and Martin and Ruth. And Pecksniff, I fear he will always be in love with himself. What is your response to this chapter of revelation and recognition?

Chapter 53

As we wind down the novel we come to chapter 53. Only one event really happens, and that event is one we all know was coming. As so, my friends, I am going to present a very short summary, the shortest summary of this novel.

In this chapter we have the confirmation that John Westlake and Ruth Pinch will indeed become husband and wife. They both agree that Tom will live with them. Old Martin Chuzzlewit and Tom arrive and help celebrate the engagement of John and Ruth. Chuzzlewit presents Ruth with a beautiful necklace, earrings, bracelets and a zone for her waist, just as he had purchased for Mary. Chuzzlewit says he will assume the role of father for both Ruth and Mary.

A “prodigious banquet” follows with Mark Tapley playing host and thus Mark gets his first experience as the landlord of the Jolly Tapley. Tom is the central figure of this banquet. All is well and now we approach the final chapter.

Thoughts

What is your opinion of this chapter?

As we wind down the novel we come to chapter 53. Only one event really happens, and that event is one we all know was coming. As so, my friends, I am going to present a very short summary, the shortest summary of this novel.

In this chapter we have the confirmation that John Westlake and Ruth Pinch will indeed become husband and wife. They both agree that Tom will live with them. Old Martin Chuzzlewit and Tom arrive and help celebrate the engagement of John and Ruth. Chuzzlewit presents Ruth with a beautiful necklace, earrings, bracelets and a zone for her waist, just as he had purchased for Mary. Chuzzlewit says he will assume the role of father for both Ruth and Mary.

A “prodigious banquet” follows with Mark Tapley playing host and thus Mark gets his first experience as the landlord of the Jolly Tapley. Tom is the central figure of this banquet. All is well and now we approach the final chapter.

Thoughts

What is your opinion of this chapter?

Chapter 54

It’s the wedding day for Miss Pecksniff and Mr Moodle and preparations are afoot at Todgers’s. Cherry has taken the opportunity to invite quite a diverse gathering of people. Martin Chuzzlewit senior arrives at Todgers’s and learns that she does not look favourably on the impending wedding. He then goes to see Merry where he finds her in a darkened room still accompanied by the faithful Chuffey. Chuzzlewit asks Merry for her forgiveness for his earlier treatment of her. She kisses his hand and thanks him for his subsequent kindnesses. Chuzzlewit urges Merry to leave Todgers’s immediately and he will find a quiet place where she can continue to recover from her shock. He will be her benefactor. Chuzzlewit urges her to leave Todgers’s before Cherry’s wedding. Mrs Todgers completely agrees with Chuzzlewit.

Too late! Cherry comes into the room and an uncomfortable situation obviously arises. Chuzzlewit attempts to encourage a kind parting of the two sisters and tells Cherry that she may need a friend someday. Cherry says that Augustus is the only friend she needs, and is very happy to forsake all others. Chuzzlewit and Mrs Todgers then conduct Merry outside. Dickens tells us that Mrs Todgers has a “well-conditioned soul.”

Thoughts

How much were you surprised by Martin Chuzzlewit’s kindness and concern for Merry? Did you find it credible?

Why do you think Dickens thought it important to point out that Mrs Todgers is a good person?

Once outside, Chuzzlewit sees Mark who is extremely happy. It turns out he has just seen former neighbours from his time in a Eden back on British soil. Chuzzlewit is overjoyed with this news. So much for the good news. The wedding is eminent but Moodle has not yet arrived. He does not arrive, but a letter from him is presented to Cherry. Upon reading it she faints. From the letter we learn that Moodle has run away to Australia. He tells Cherry that he still loves Merry and wished Cherry had left him alone. He tells Cherry she can have the furniture.

Time passes. As the novel draws to its conclusion we hear the sounds of an organ, and the organist is Tom Pinch. His life is “tranquil, calm, and happy.” We learn that Pecksniff has become a poor drunk who writes letters of appeal to Tom for funds and claims that he is the architect of all Tom’s successes. We learn that Mary and Martin junior had a child and this child loves Tom. On one occasion Tom nursed the child back to health. We learn that Martin Chuzzlewit senior has passed, we learn that Ruth and Tom still share that special bond of deep love that transcends all earthy knowledge. And Tom’s music, ... well it is noble music that uplifts one to Heaven.

Thoughts

To what extend did you like the way Dickens completed the novel and set his characters off into their futures?

It’s the wedding day for Miss Pecksniff and Mr Moodle and preparations are afoot at Todgers’s. Cherry has taken the opportunity to invite quite a diverse gathering of people. Martin Chuzzlewit senior arrives at Todgers’s and learns that she does not look favourably on the impending wedding. He then goes to see Merry where he finds her in a darkened room still accompanied by the faithful Chuffey. Chuzzlewit asks Merry for her forgiveness for his earlier treatment of her. She kisses his hand and thanks him for his subsequent kindnesses. Chuzzlewit urges Merry to leave Todgers’s immediately and he will find a quiet place where she can continue to recover from her shock. He will be her benefactor. Chuzzlewit urges her to leave Todgers’s before Cherry’s wedding. Mrs Todgers completely agrees with Chuzzlewit.

Too late! Cherry comes into the room and an uncomfortable situation obviously arises. Chuzzlewit attempts to encourage a kind parting of the two sisters and tells Cherry that she may need a friend someday. Cherry says that Augustus is the only friend she needs, and is very happy to forsake all others. Chuzzlewit and Mrs Todgers then conduct Merry outside. Dickens tells us that Mrs Todgers has a “well-conditioned soul.”

Thoughts

How much were you surprised by Martin Chuzzlewit’s kindness and concern for Merry? Did you find it credible?

Why do you think Dickens thought it important to point out that Mrs Todgers is a good person?

Once outside, Chuzzlewit sees Mark who is extremely happy. It turns out he has just seen former neighbours from his time in a Eden back on British soil. Chuzzlewit is overjoyed with this news. So much for the good news. The wedding is eminent but Moodle has not yet arrived. He does not arrive, but a letter from him is presented to Cherry. Upon reading it she faints. From the letter we learn that Moodle has run away to Australia. He tells Cherry that he still loves Merry and wished Cherry had left him alone. He tells Cherry she can have the furniture.

Time passes. As the novel draws to its conclusion we hear the sounds of an organ, and the organist is Tom Pinch. His life is “tranquil, calm, and happy.” We learn that Pecksniff has become a poor drunk who writes letters of appeal to Tom for funds and claims that he is the architect of all Tom’s successes. We learn that Mary and Martin junior had a child and this child loves Tom. On one occasion Tom nursed the child back to health. We learn that Martin Chuzzlewit senior has passed, we learn that Ruth and Tom still share that special bond of deep love that transcends all earthy knowledge. And Tom’s music, ... well it is noble music that uplifts one to Heaven.

Thoughts

To what extend did you like the way Dickens completed the novel and set his characters off into their futures?

Final Discussion

Below you will find some end of novel questions to reflect upon and respond to as you think fit.

Please offer your own questions and comments as well. Together we can reflect upon our reading of Dickens’s Martin Chuzzlewit.

The title of the novel is Martin Chuzzlewit. Do you think this title refers to old Martin or young Martin. Why?

What alternate title would you give to the novel?

Who do you consider to be the focal/main character of the novel?

Having completed the novel what are your thoughts of Martin junior and Mark going to America?

What are some of the incidences of humour that you enjoyed in the novel?

Which character did you dislike most? Why?

If you could give Dickens some advice on wring his next novel what would it be?

Please, offer your own questions for us to consider.

Below you will find some end of novel questions to reflect upon and respond to as you think fit.

Please offer your own questions and comments as well. Together we can reflect upon our reading of Dickens’s Martin Chuzzlewit.

The title of the novel is Martin Chuzzlewit. Do you think this title refers to old Martin or young Martin. Why?

What alternate title would you give to the novel?

Who do you consider to be the focal/main character of the novel?

Having completed the novel what are your thoughts of Martin junior and Mark going to America?

What are some of the incidences of humour that you enjoyed in the novel?

Which character did you dislike most? Why?

If you could give Dickens some advice on wring his next novel what would it be?

Please, offer your own questions for us to consider.

Some observations, not yet on the novel as a whole but on the final chapters: I found it very funny to notice that Mrs. Gamp, now that she knew how the land was lying, treated Mr. Chuffey with much more tenderness and consideration, knowing which side her bread is buttered on. I also wondered why Jonas did not simply poison Chuffey as well. Was he afraid that two deaths of old men in his household in too short a spell of time would create suspicion? Or did he just abstain from killing Chuffey because otherwise he would have thwarted the author's solution to the murder mystery?

I did not find Martin senior's sudden change, or rather the revelation that he had never really changed at all, very convincing. It is a bit in the tradition of deus ex machina, and Dickens would do it again, even with more of dissatisfaction involved to me, in one of the later novels we have already read in this group: (view spoiler)

I did not find Martin senior's sudden change, or rather the revelation that he had never really changed at all, very convincing. It is a bit in the tradition of deus ex machina, and Dickens would do it again, even with more of dissatisfaction involved to me, in one of the later novels we have already read in this group: (view spoiler)

I also found Martin Sr's change a bit too convenient. However, it's all wrapped up nicely, isn't it?

Jonas couldn't end up differently than dead by suïcide I think. It was the only way to get him out of the way and give Merry her freedom back, allbeit a very much subdued one. And as for Moodle, it was clear all along that he never wanted to marry Cherry, wasn't it? It was only Cherry who pushed her wants on him and tricked him into being engaged somehow. Probably by telling people they were engaged, so that he couldn't get out of it honourably.

I must admit I did have a lot of fun about Pecksniff being rebuffed by Martin Sr. And about Slyme who now had to work for his money.

I think the novel was named after old Martin, since he in the end was this kind of spider in the web, wasn't he? I do think Tom is a good contender for being the main character though. If it had been a Jane Austen novel, it might have been called Lies and Madness. Somehow 'Deception' could've been a good word for in the title.

About which character I disliked the most ... I'm torn between Jonas (the creep who made this novel into a kind of horror novel), or Slyme (I really detest prigs like him, who think they are from too good a family to work).

I do wonder, where did Cherry go after she didn't get married?

Jonas couldn't end up differently than dead by suïcide I think. It was the only way to get him out of the way and give Merry her freedom back, allbeit a very much subdued one. And as for Moodle, it was clear all along that he never wanted to marry Cherry, wasn't it? It was only Cherry who pushed her wants on him and tricked him into being engaged somehow. Probably by telling people they were engaged, so that he couldn't get out of it honourably.

I must admit I did have a lot of fun about Pecksniff being rebuffed by Martin Sr. And about Slyme who now had to work for his money.

I think the novel was named after old Martin, since he in the end was this kind of spider in the web, wasn't he? I do think Tom is a good contender for being the main character though. If it had been a Jane Austen novel, it might have been called Lies and Madness. Somehow 'Deception' could've been a good word for in the title.

About which character I disliked the most ... I'm torn between Jonas (the creep who made this novel into a kind of horror novel), or Slyme (I really detest prigs like him, who think they are from too good a family to work).

I do wonder, where did Cherry go after she didn't get married?

Jantine wrote: "I also found Martin Sr's change a bit too convenient. However, it's all wrapped up nicely, isn't it?

Jonas couldn't end up differently than dead by suïcide I think. It was the only way to get him ..."

Yes. I can see your logic as to the novel’s title referring to Martin senior. Isn’t Slyme a perfectly Dickensian name? I smile each time I think about it.

As for Cherry? Could she have returned to Todgers? It would be humiliating for her, but Mrs Todgers does seem to have a soft heart under her more toughened exterior. Since her father is without money I wonder where she would have access to money. No husband, no father, dare we imagine her working in a low-paying occupation? Dare she go husband hunting again?

Jonas couldn't end up differently than dead by suïcide I think. It was the only way to get him ..."

Yes. I can see your logic as to the novel’s title referring to Martin senior. Isn’t Slyme a perfectly Dickensian name? I smile each time I think about it.

As for Cherry? Could she have returned to Todgers? It would be humiliating for her, but Mrs Todgers does seem to have a soft heart under her more toughened exterior. Since her father is without money I wonder where she would have access to money. No husband, no father, dare we imagine her working in a low-paying occupation? Dare she go husband hunting again?

I welcomed the return of Slyme, and I wondered that Martin senior seemed to despise him for working as a police officer. Was it considered a very lowly thing to do in those days? This was a little before the professionalization of the London police force, and so there might have been little public merit in working as a law enforcer.

I think that Jonas's suicide spared Merry the public humiliation of her husband being found guilty of murder and being convicted. In that case, his money - there must be very little now - would have been forfeited, wouldn't it?

I think Montague is the least likeable character in the whole novel because he brought misery on more people than Jonas: Think of all the families he ruined. - And here is a tricky question: Was it not through Martin senior's employing Montague as a spy on Martin junior and the payment he received that Montague had the means to start his fraudulent company? Does that not indirectly make Martin senior responsible for Montague's rise from a cadger to a major fraud?

What do you think of Slyme's behaviour towards Jonas?

I think that Jonas's suicide spared Merry the public humiliation of her husband being found guilty of murder and being convicted. In that case, his money - there must be very little now - would have been forfeited, wouldn't it?

I think Montague is the least likeable character in the whole novel because he brought misery on more people than Jonas: Think of all the families he ruined. - And here is a tricky question: Was it not through Martin senior's employing Montague as a spy on Martin junior and the payment he received that Montague had the means to start his fraudulent company? Does that not indirectly make Martin senior responsible for Montague's rise from a cadger to a major fraud?

What do you think of Slyme's behaviour towards Jonas?

Tristram, I think it was more that Slyme openly despised having to work for his money, and he tried to have Martin despise that as well and so give him enough money to live upon/making him at least a partial heir. And I think Martin did not frown upon Slyme working an honest job (remember, he also didn't frown upon Tom, and Martin Jr thought asking him to help with finding a job would work in his favour), but upon Slyme using that for gain, like it was something lowly he had to be saved from to save the family's good name.

Tristram and Jantine

Good question about what would happen to any residue money from the company. Whatever it was could well have been spirited away by the other directors who disappeared.

I see your logic of Montague being the most unlikeable person in the book. He and his co-conspirators did harm many. The victims of the illegal scheme thought they were insuring themselves in case of a disaster and loss. They ended up lining the pockets of crooks and becoming the object of a disaster.

Interesting question about the relationship between old Martin and Montague. That does make sense in a rather tragic and ironic way. As for Slyme and Jonas I wonder if the phrase “there is no honour among thieves” might sum up their behaviours and consequences?

Good question about what would happen to any residue money from the company. Whatever it was could well have been spirited away by the other directors who disappeared.

I see your logic of Montague being the most unlikeable person in the book. He and his co-conspirators did harm many. The victims of the illegal scheme thought they were insuring themselves in case of a disaster and loss. They ended up lining the pockets of crooks and becoming the object of a disaster.

Interesting question about the relationship between old Martin and Montague. That does make sense in a rather tragic and ironic way. As for Slyme and Jonas I wonder if the phrase “there is no honour among thieves” might sum up their behaviours and consequences?

Some responses to the previous comments:

Some responses to the previous comments:Peter wrote: "Chapter 51...The sound of the word “murder” rolled on from house to house. ..."

Isn't it amazing in Dickens' novels how many people are milling about in the streets, and how quickly the gossip travels? Every dramatic moment seemed to be on public display. Twitter and Facebook couldn't keep up. :-)

We learn that Anthony died not because of being poisoned but perhaps a broken heart; Jonas feels he is the clear.... Were you surprised by this part of the plot?

Yes! It was a fun but, I thought, unbelievable twist. I wish the actual cause of Anthony's death had been explained in a more rational way.

Were you surprised to see Chevy Slyme make another appearance in the novel?

It seemed likely that he'd show up again at some point. I was surprised at his new role, though, and how it (loosely) tied into the plot. Like Tristram, I saw Slyme as being resentful for having to "lower" himself by working for a living. But it allowed him the satisfaction of taking out his grievances with some of his family.

the closed fist of our earlier chapters was not only a suggestive trait of Jonas’s violent nature but also foreshadowing of Jonas taking his own life.

Nicely done. The fist was, I think, also representative of the beating I think Jonas must have given Tigg in the woods. Dickens used that physical trait well.

Tristram wrote: "I also wondered why Jonas did not simply poison Chuffey as well...."

YES. Jonas was obviously not averse to murder, and Chuffey was a huge threat to him. This, to me, was a weak point in the plot.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 52....Were you at all surprised at the fact that ...we see Pecksniff being hit by old Martin Chuzzlewit?..."

Peter wrote: "Chapter 52....Were you at all surprised at the fact that ...we see Pecksniff being hit by old Martin Chuzzlewit?..."I was taken aback by this, I admit. It seemed unnecessarily violent and out of character. I thought a bit about Pecksniff's propensity for stumbling throughout the story, and suppose that Dickens may have been foreshadowing his downfall. Martin's beating made it literal.

Pecksniff maintains his gentlemanly hypocrisy

You've gotta give the guy credit for consistency! His mask never cracked.

It’s Bailey! He is alive

WHY? Bailey was fun; I enjoyed his character and was saddened by his death. But what was the point of his resurrection? This bit took the "happy ending" a bit too far for me.

Old Martin suggests that Mrs Gamp be a bit more honest and a bit less thirsty in the future.

I enjoyed Martin Sr.'s admonitions to Sarah, via Sweedlepipe. Like Peter, I doubt they'll do much good. :-)

he has just seen former neighbours from his time in a Eden back on British soil.

Talk about wrapping things up in a pretty bow! But perhaps not too pretty. Apparently all of their children succumbed from the dangers and diseases in America. It's really quite sad. But I guess they're glad to be back on English soil, and now have a benefactor in a grateful Martin, Sr.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 54 Chuzzlewit attempts to encourage a kind parting of the two sisters and tells Cherry that she may need a friend someday...." AND Why do you think Dickens thought it important to point out that Mrs Todgers is a good person?

Peter wrote: "Chapter 54 Chuzzlewit attempts to encourage a kind parting of the two sisters and tells Cherry that she may need a friend someday...." AND Why do you think Dickens thought it important to point out that Mrs Todgers is a good person?That warning raised some flags, didn't it? But we didn't have to wait long for the payoff. Jantine wondered where Cherry went after being abandoned at the altar. I assumed she and her father lived together, destitute and bitter. But maybe Peter's question about Dickens emphasizing Mrs. Todger's goodness would imply that she took pity on Merry and allowed her to stay on at Todger's.

Peter wrote: "Final Discussion

Peter wrote: "Final DiscussionWhat alternate title would you give to the novel?

I think I may have just gone with Chuzzlewit. Martin, Sr. was the patriarch -- and the spider in the web, as Jantine so aptly described him. But the story was about a dysfunctional family, and I think leaving the Christian name off in the title would have been more appropriate.

Who do you consider to be the focal/main character of the novel?

Truly an ensemble cast, which was kind of nice.

Having completed the novel what are your thoughts of Martin junior and Mark going to America?

Unnecessary. Martin could have learned humility in any number of other ways. But it's okay for Dickens to have chosen this, and even to have been critical of the US. What's unforgivable is that much of the content of those chapters was entirely too long, tedious, and inconsequential to the plot.

What are some of the incidences of humour that you enjoyed in the novel?

My favorite in this novel, and among my favorites in all of Dickens' novels, is the scene in which Sarah and Betsey have their falling out. Makes me laugh just thinking about it. :-)

If you could give Dickens some advice on wring his next novel what would it be?..."

Need I say it? For the love of God, please bury dear little Mary Hogarth once and for all, and let her rest in peace!! (Notice not one, but two exclamation points, indicating just how strongly I feel on this subject.)

Final thoughts:

Final thoughts: Dickens is obviously maturing as an author. His coincidences, while still far-fetched, are now at least within the realm of possibility. His characters, while still extreme, are at least somewhat recognizable. His plots are becoming better crafted and well thought out. His mastery of literary devices like foreshadowing, allegory, imagery, etc. is on display.

Despite that, I still found Martin Chuzzlewit to be implausible in a fundamental way. Martin, Sr.'s machinations were over the top. The question I keep coming back to is, "Why?" What on Earth possessed Martin to feel as if he had to stage such an elaborate deception? It's the premise for the entire plot, and yet it's puzzling. Which, for me, means the whole novel is built on a foundation of sand. I wonder if the book had been written from Martin, Sr.'s perspective, and the reader had been able to see him pulling the strings and spinning his webs, how it may have been different.

Covetousness (is that a word?) might be another theme for the novel. Of course, there's a lot of coveting of money going on. But also in relationships: Tom covets Mary, and Cherry covets - for some unfathomable reason - Jonas, and later Moodle. Such different outcomes for them. Question: How do you feel about Tom's happiness for Martin and Mary? Is it believable for him to be disappointed in love, yet live surrounded by happy couples - including the woman he pined for - and not feel, as Cherry does, even a little bitterness, resentment or, at the very least, dismay at being alone?

Mary Lou wrote: "Like Tristram, I saw Slyme as being resentful for having to "lower" himself by working for a living. But it allowed him the satisfaction of taking out his grievances with some of his family."

I think we all did. What did you make of Martin Sr's reaction to that? Was he appalled by Slyme working as a police officer, or by Slyme trying to weasel money out of it like it was a bad thing to work? Or maybe both?

I absolutely agree about the American parts. They were too much, too long, and Martin could've befallen any kind of bad thing in England as well to turn him into a better man. The wrap-up with meeting the neighbours again was too much too.

I think we all did. What did you make of Martin Sr's reaction to that? Was he appalled by Slyme working as a police officer, or by Slyme trying to weasel money out of it like it was a bad thing to work? Or maybe both?

I absolutely agree about the American parts. They were too much, too long, and Martin could've befallen any kind of bad thing in England as well to turn him into a better man. The wrap-up with meeting the neighbours again was too much too.

Mary Lou wrote: "Final thoughts:

Dickens is obviously maturing as an author. His coincidences, while still far-fetched, are now at least within the realm of possibility. His characters, while still extreme, are a..."

Hi Mary Lou

Your thoughts are incisive and wide-ranging. Thank you for the insights.

I like your title for the novel. Just Chuzzlewit. So perfect and encompassing. We do see Dickens maturing as a novelist but, as you note, there still are major stumbles. I make no secret about how much I like Dombey. I think you will see a major improvement in the organization, control of material, and creation of character. To me, Dickens also has a much stronger control over symbolism and narrative technique.

Covetousness is certainly a word and a major theme of MC. A Christmas Carol was written concurrently during the serial publication of MC. To me, it seems that Dickens hit the mark exactly with ACC. With MC, I feel Dickens bumbled around far too much.

Dickens is obviously maturing as an author. His coincidences, while still far-fetched, are now at least within the realm of possibility. His characters, while still extreme, are a..."

Hi Mary Lou

Your thoughts are incisive and wide-ranging. Thank you for the insights.

I like your title for the novel. Just Chuzzlewit. So perfect and encompassing. We do see Dickens maturing as a novelist but, as you note, there still are major stumbles. I make no secret about how much I like Dombey. I think you will see a major improvement in the organization, control of material, and creation of character. To me, Dickens also has a much stronger control over symbolism and narrative technique.

Covetousness is certainly a word and a major theme of MC. A Christmas Carol was written concurrently during the serial publication of MC. To me, it seems that Dickens hit the mark exactly with ACC. With MC, I feel Dickens bumbled around far too much.

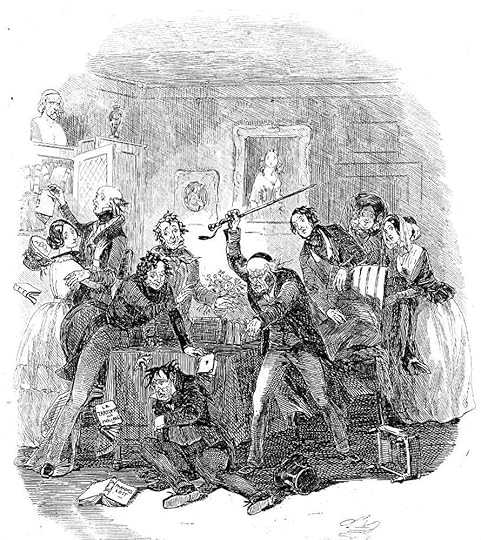

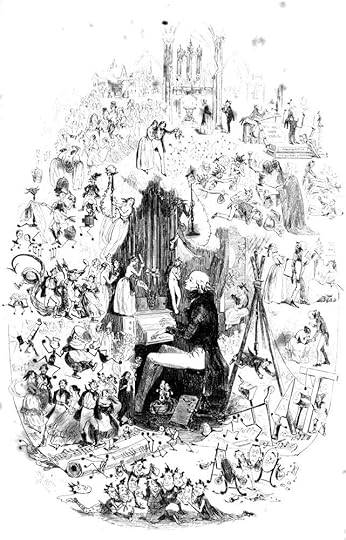

Warm reception of Mr. Pecksniff

Chapter 51

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Pecksniff advanced with outstretched arms to take the old man's hand. But he had not seen how the hand clasped and clutched the stick within its grasp. As he came smiling on, and got within his reach, old Martin, with his burning indignation crowded into one vehement burst, and flashing out of every line and wrinkle in his face, rose up, and struck him down upon the ground.

With such a well-directed nervous blow, that down he went, as heavily and true as if the charge of a Life-Guardsman had tumbled him out of a saddle. And whether he was stunned by the shock, or only confused by the wonder and novelty of this warm reception, he did not offer to get up again; but lay there, looking about him with a disconcerted meekness in his face so enormously ridiculous, that neither Mark Tapley nor John Westlock could repress a smile, though both were actively interposing to prevent a repetition of the blow; which the old man's gleaming eyes and vigorous attitude seemed to render one of the most probable events in the world. [Chapter LII, "In which the Tables are turned, completely Upside Down"]

Commentary:

With a kinetic energy reminiscent of that of Blake's God of the Old Testament, Old Martin reasserts his authority over the fractious Chuzzlewit clan by thrashing the hypocritical Pecksniff after denouncing him. Despite his persuasive, subtle speeches and postures betokening his abject humility (foreshadowing the equally hypocritical Uriah Heep in David Copperfield, 1849-50), Pecksniff seems to shrink under the glaring light of truth in old Martin's accusations and chastisement with his walking-stick. To complete the poetically just conclusion to the narrative, Young Martin and Old Martin are reconciled in the presence of John Westlock and Mark Tapley. In the climactic scene of Old Martin's revealing himself in his true colors, despite Tom's best efforts to keep them on their shelves and John Westlock's efforts to catch them, two books constituting embedded commentary have fallen: Moliere's Le Tartuffe and Milton's epic Paradise Lost have tumbled down beside Pecksniff. Regarding these embedded texts Monod remarks,

Steig further points to various possible sources of Phiz's inspiration, such as French artists like David, Fragonard and Daumier. On the other hand, he courteously and irrefutably corrects the conjecture of an earlier French critic that Dickens himself had initiated the reference to Tartuffe in one of the last plates, presenting the discomfiture of Mr. Pecksniff. This does not invalidate the notion that Dickens was influenced by Molière in the creation of Pecksniff. Phiz recognized and proclaimed it. By leaving the plate unmodified, Dickens fully sanctioned this recognition.

Phiz reminds us through their presence and the bust on the shelf that the room in which Pecksniff receives his comeuppance is the private library that Tom has taken six months to organize in The Temple. The book titles comment ironically on Pecksniff's reversal of fortune as a hypocrite and facsimile of transformed Satan. According to Steig, both titles underscore Pecksniff's fall and metamorphosis. Like Satan in his final appearance in Paradise Lost, a stunned and shrunken Pecksniff abjectly cowers at the blow he is about to receive. Old Martin's hand points outward, as if expelling the anarchic force, his hand like that of Urizen the Creator of the Material World in William Blake's celebrated 1794 watercolor. Old Martin's dramatic pose (combined with his Hebraic skullcap) implies that, like the Old Testament's Jehovah, he is about to visit his wrath upon the unrighteous. This, then, constitutes a comic Last Judgment. Like William Blake's deity, by the power of his shamanic rod the old man will define Pecksniff's future by excluding him from the extended Chuzzlewit family. His coat streams out behind him as if, like the Michelangelo figures on the Sistine Ceiling, he is inspired by a wind of prophecy. In anger and determination, he strides forward, a towering figure recalling the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah. Fred Barnard's Household Edition version of this scene is static rather than kinetic. In his realistic wood-engraving entitled The Fall of Pecksniff. Barnard communicates little of this sense of energy and this powerful connotation of divine wrath present in the original July 1844 steel-engraving.

Although Phiz's illustration reflects the general disposition of characters as described in Dickens's letter to the artist in June 1844 for the final installment, matters of costuming and setting, as well more subtle issues such as body language, he had left to Phiz's discretion. However, Phiz penciled in the following at the foot of Dickens's letter:

Mrs. Lupin & Mary — behind Martin's chair.

Yg. Martin on the other side.

Tom & his sister.

Old Man — Pecksniff.

John Westlock & Mark

And, indeed, Phiz has disposed the figures as instructed, but some forward and other back in order (in contrast to Fred Barnard's The Fall of Pecksniff. to create the illusion of depth. Mark Tapley is recognizable by his unkempt hair, jacket with large lapels, and waistcoat — he is not wearing a hat, however. Old Martin's raised cane points toward Young Martin, perhaps implying that the penitent youth has now displaced the hapless architect as the principal Chuzzlewit heir and the old man's favorite. the overturned inkwell about to fall on Pecksniff will only add to his sense of degradation, but it also reminds us that Old Martin will have no further need of ink once he has changed his will in favor of Martin Junior and Mary. Phiz has avoided he static aspect of a typical Cruikshankian tableau by catching his figures in the midst of movement, like the Daphne and Apollo of the Baroque sculptor Bernini. Although Dickens specifies that Old Martin will strike Pecksniff down "with a well-directed blow" (Chapter LII), but Phiz creates a sense of expectation in the reader, who in the serial encounters the illustration at the beginning of the installment, long before the textual moment realized.

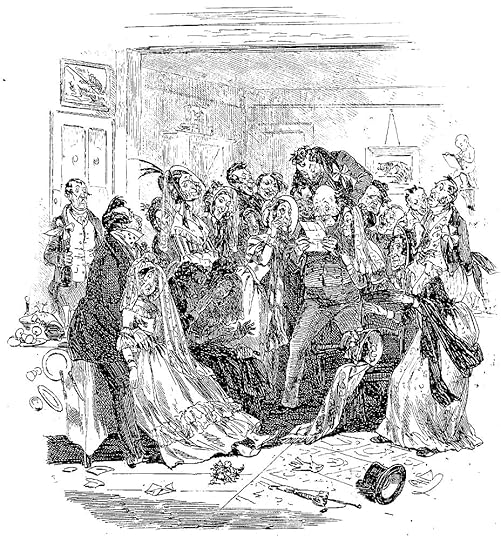

The nuptials of MIss Pecksniff

Chapter 54

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The bride was now alarmed; seriously alarmed. Good Heavens, what could have happened! Augustus! Dear Augustus!

Mr. Jinkins volunteered to take a cab, and seek him at the newly-furnished house. The strong-minded woman administered comfort to Miss Pecksniff. "It was a specimen of what she had to expect. It would do her good. It would dispel the romance of the affair." The red-nosed daughters also administered the kindest comfort. "Perhaps he'd come," they said. The sketchy nephew hinted that he might have fallen off a bridge. The wrath of Mr. Spottletoe resisted all the entreaties of his wife. Everybody spoke at once, and Miss Pecksniff, with clasped hands, sought consolation everywhere and found it nowhere, when Jinkins, having met the postman at the door, came back with a letter, which he put into her hand.

Miss Pecksniff opened it, uttered a piercing shriek, threw it down upon the ground, and fainted away.

They picked it up; and crowding round, and looking over one another's shoulders, read, in the words and dashes following, this communication:

"Off Gravesend.

"Clipper Schooner, Cupid

"Wednesday night.

"Ever Injured Miss Pecksniff

"Ere this reaches you, the undersigned will be — if not a corpse — on the way to Van Dieman's Land. Send not in pursuit. I never will be taken alive!

"The burden — 300 tons per register — forgive, if in my distraction, I allude to the ship — on my mind — has been truly dreadful. Frequently — when you have sought to soothe my brow with kisses — has self-destruction flashed across me. Frequently — incredible as it may seem — have I abandoned the idea.

"I love another. She is Another's. Everything appears to be somebody else's. Nothing in the world is mine — not even my Situation — which I have forfeited — by my rash conduct — in running away.

Commentary: Charity Jilted on Her Wedding Day:

The guests read Mr. Moddle's farewell letter greedily, while in the bitterness of her mortification, Miss Pecksniff fainted away.

In the plate facing the passage illustrated, the wedding guests greedily devour Mr. Moddle's farewell letter, while in the bitterness of her mortification before the assembled wives, mothers, and daughters of the extended clan, Miss Pecksniff finally faints away "in earnest" (as opposed to a merely staged response). Having learned that her prospective bridegroom has sailed for the Antipodes — in fact, Van Diemen's Land (re-named "Tasmania" in 1856), Miss Pecksniff has thrown his farewell epistle to the ground before theatrically shrieking and fainting into her father's arms. The cause of her mortification is not so much the loss of Augustus Moddle as the loss of status and control that the marriage would have conferred upon her. As an old maid, she may not receive another such opportunity, placing her in the Ultima Thule of the Chuzzlewit clan. With a nice piece of irony, Dickens gives the return address as "Off Gravesend. Clipper Schooner, Cupid." As she awkwardly faints, Charity causes cutlery and china to tumble from the table, implying the utter disruption of her plans for connubial dominance.

Charity's reaction is largely contrived rather than genuine, for Dickens adds at the conclusion of the reading aloud of the letter:

They thought as little of Miss Pecksniff, while they greedily perused this letter, as if she were the very last person on earth whom it concerned. But Miss Pecksniff really had fainted away. The bitterness of her mortification; the bitterness of having summoned witnesses, and such witnesses, to behold it; the bitterness of knowing that the strong-minded women and the red-nosed daughters towered triumphant in this hour of their anticipated overthrow; was too much to be borne. Miss Pecksniff had fainted away in earnest.

But which male character, Chuzzlewit or hanger-on, reads the letter (in the absence of authorial identification of the letter-reader) is a subject for speculation as this figure does not resemble any of the males in the earlier family portrait, Pleasant Little Family Party at Mr. Pecksniff's in Chapter IV. Since Mr. Pecksniff, recognizable by his distinctive hair style, is supporting his elder daughter, the reader is probably Mr. Jinkins. Since the scene probably occurs in Todgers's, there is every likelihood that her eldest boarder, a forty-year-old book-keeper named Jinkins, has stepped forward to read the correspondence to the assembled wedding-guests. And which clan member is clambering above the reader for a better view? With a full head of hair, this cousin cannot be the splenetic Spottletoe, but may indeed be Chevy Slyme, who figures so prominently in Jonas's arrest and suicide.

Michael Steig in Dickens and Phiz gives a detailed exposition of this illustration in which he utilizes the instructions which Dickens posted to Phiz:

2nd Subject.

represents Miss Charity Pecksniff on the bridal morning. The bridal [table] breakfast is set out in Todgers's drawing-room. Miss Pecksniff has invited the strong-minded woman, and all that party who were present in Mr Pecksniff's parlor in the second number. We behold her triumph. She is not proud, but forgiving. Jinkins is also present and wears a white favor in his button hole. Merry is not there. Mrs. Todgers is decorated for the occasion. So are the rest of the company. The bride wears a bonnet with an orange flower. They have waited a long time for Moddle. Moddle has not appeared. The strong-minded woman has [frequently] expressed a hope that nothing has happened to him; the daughters of the strong-minded woman (who are bridesmaids) have offered consolation of an aggravating nature. A knock is heard at the door. It is not Moddle but a letter from him. The bride opens it, reads it, shrieks, and swoons. Some of the company catch it and crowd about each other, and read it over one another's shoulders. Moddle writes that he can't help it — that he loves another — that he is wretched for life — and has that morning sailed from Gravesend for Van Deimen's Land.

Lettering. The Nuptials of Miss Pecksniff receive a temporary check. ["Dickens to Phiz," June 1844; reproduced in Steig, page 78, and Cardwell]

The most remarkable thing about this communication is that it contains details (such as colors) and events which cannot possibly be shown in the illustration, some of which are not even in the novel's text, such as the hopes of the strong-minded woman and the consolations of her daughters. Phiz drew a vertical line in the margin next to the last four lines of the note which are extraneous to what an illustrator can depict. Perhaps this nondepictable material is not totally irrelevant, since by giving a sense of the drama behind the actual moment the author aided the artist in portraying characters' expressions and physical attitudes. However, Dickens clearly tended to get carried away: the note shows that he was going on still further and checked himself, as though suddenly aroused from his enthusiastic vision of the scene. [Steig, Chapter Three]

Although the design is necessarily cluttered by its having so many figures, Phiz manages to individualize through their postures and facial expressions, and organizes the design around the reading of Moddle's letter (right of centre) and the theatrical fainting of Charity Pecksniff, left of centre. Although the assembled Chuzzlewits (largely an undistinguished female audience, in contrast to the male-dominated Pleasant Little Family Party at Mr. Pecksniff's in Chapter IV) apparently all judge Charity severely; moreover, ironically the reader feels that Moddle has escaped a toxic relationship, and a lifetime of buying such things as rosewood chairs that he neither wants nor needs. As if to comment upon Moddle's fortunate escape, Phiz has embedded a fishing painting above the door in which the angler in reaching for his catch, wriggling on the line, is about to go off balance — an ironic reference, perhaps, to Franz Schubert's popular lyric Die Forelle, composed in early 1817. And the now-familiar cherub as an architectural elaboration (upper right) is busily writing a letter, although undoubtedly it is a letter of a rather different caste.

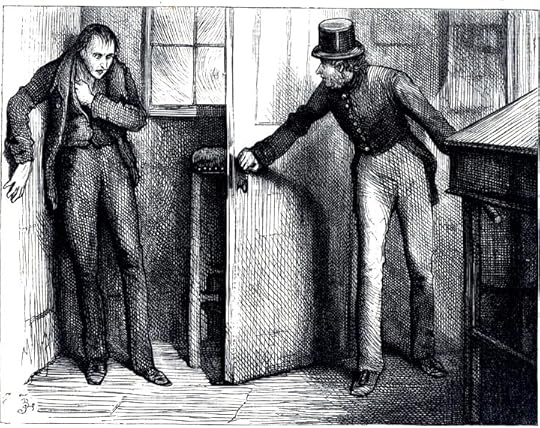

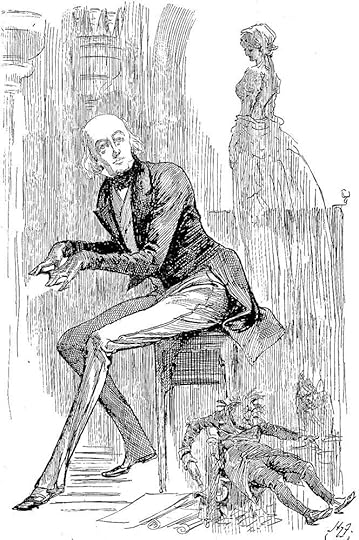

He started back as his eyes met those of Jonas

Chapter 51

Fred Barnard

"He started back as his eyes met those of Jonas, standing in an angle of the wall, and staring at him. His neckerchief was off; his face was ashy pale."

Illustration by Fred Barnard for Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit.

In a final effort to cheat the forces of justice for the two murders he committed, with a purse containing one hundred pounds in gold Jonas has bribed his cousin, Chevy Slyme, now a police officer, for five minutes by himself during which he attempts to commit suicide. In the moment depicted, the officer returns to the room expecting to find his prisoner dead; the picture already alerts the reader to the fact that Jonas has not been able to summon up enough courage, and is now trapped.

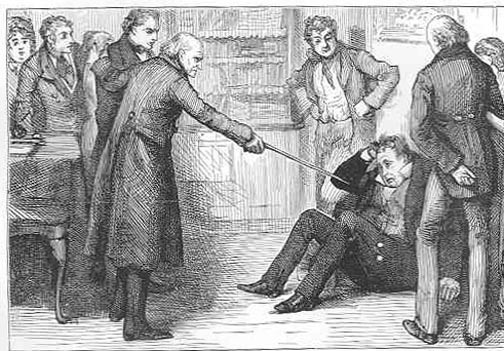

The fall of Pecksniff

Chapter 52

Fred Barnard

The Fall of Pecksniff. (1870s). Illustration by Fred Barnard for Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit.

Old Martin unmasks the conniving hypocrite who has attempted to alienate him from his grandson and marry his companion, Mary Graham.

"Yes, sir," returned Miss Pecksniff

Chapter 54

Fred Barnard

"Yes, sir," returned Miss Pecksniff, modestly. "I am—my dress is rather—really, Mrs. Todgers!"

Illustration by Fred Barnard for Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit.

Despite her brother-in-law's recent arrest and suicide, in ignorance of Augustus Moddle's sudden departure for Van Diemen's Land (Australia), Charity Pecksniff presses ahead with her wedding plans, if only to spite her sister, Mercy.

Tom's Reverie

Chapter 54

Fred Barnard

This is a melancholy and stark contrast to the lively baroque complexity of Phiz's final illustration thirty years earlier. As in the letter- press, Tom touches the notes of his organ lightly; however. Barnard departs from Dickens's text by including the shadowy figures of Martin and Mary in the background. According to Barnard's interpretation, Tom never recovers from his unrequited love for Mary, but enjoys the love and companionship of his friends' children.

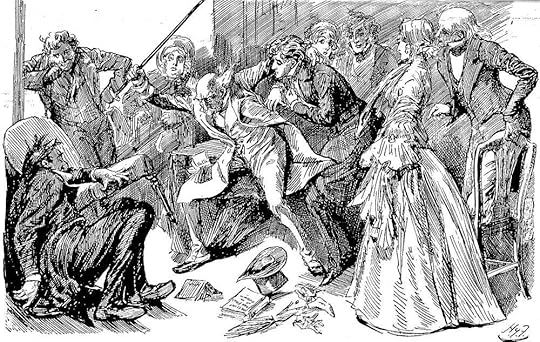

The fall of Mr. Pecksniff

Chapter 52

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

"Horde of unnatural plunderers and robbers!" he continued; "leave him! leave him, I say! Begone! Abscond! You had better be off! Wander over the face of the earth, young sirs, like vagabonds as you are, and do not presume to remain in a spot which is hallowed by the grey hairs of the patriarchal gentleman to whose tottering limbs I have the honour to act as an unworthy, but I hope an unassuming, prop and staff. And you, my tender sir," said Mr Pecksniff, addressing himself in a tone of gentle remonstrance to the old man, ‘how could you ever leave me, though even for this short period! You have absented yourself, I do not doubt, upon some act of kindness to me; bless you for it; but you must not do it; you must not be so venturesome. I should really be angry with you if I could, my friend!"

He advanced with outstretched arms to take the old man’s hand. But he had not seen how the hand clasped and clutched the stick within its grasp. As he came smiling on, and [as Pecksniff] got within his reach, old Martin, with his burning indignation crowded into one vehement burst, and flashing out of every line and wrinkle in his face, rose up, and struck him down upon the ground.

Commentary: Improving upon the Treatments of Phiz (1844) and Fred Barnard (1872)

The object of Old Martin's pent-up and now unmitigated fury is the cowering, barely recognizable Pecksniff crammed into the lower left-hand corner, as young Martin attempts to restrain the old man and Tom Pinch (right) looks on dispassionately. Other readily recognizable figures in the dramatic tableau are Mark Tapley (right, above Pecksniff), Mrs. Lupin (beside Mark), John Westlock and Ruth Pinch (beside young Martin), and Mary Graham (between Tom Pinch and Martin). As in Phiz's Warm Reception of Mr. Pecksniff by His Venerable Friend (see below), the illustrator has created a visual finalé in which we meet most of the principal characters for the last time, the glaring exceptions being Montague Tigg and Jonas Chuzzlewit (both now dead) and the boozy sick-room nurse, Sairey Gamp, who, in fact, will shortly appear in the text, accompanied by Bailey and Paul Sweedlepipes.

Over the course of a number of illustrated editions of The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (1844) a number of artists have assailed this climactic scene, so that Furniss had useful precedents in the original version, Phiz's Warm Reception of Mr. Pecksniff by His Venerable Friend (see below, and the Household Edition illustration by Barnard, The Fall of Pecksniff (see below). What Furniss seems to have been determined to attain was a balance between the chaotic and dynamic scene of the old patriarch in Phiz bringing the hypocrite to judgment and the more static, tableau vivant treatment of the same subject by Barnard. Although in the 1872 plate Barnard has brought together nine of the principals, the women are obscured entirely as Tom, the man whom Pecksniff unjustly vilified, stares down at the prostrate figure at the end of Old Martin's cane.

Furniss, then, seems to have striven to inject more action while revealing the faces of all nine characters, each in a unique pose and caught in the midst of the action, with the hat, books, and umbrella and the possessed old man as the vortex, and the cane raised to strike, as in Phiz, rather than merely prodding Pecksniff after the initial blow, as in Barnard. Furniss knew that he could improve upon Barnard's muted interpretation of his material, but faced a genuine challenge in excelling Dickens's original illustrator. In the final analysis, Furniss has equaled Phiz for sheer energy and clarity, but has lost some of the exquisite background detailing of the July 1844 illustration in order to focus the reader's attention on the left-hand register. A nice touch, however, is the fallen volume beside Pecksniff's respectable top-hat: the title of Gibbon's Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire, makes an embedded commentary on the crushing of Pecksniff's dreams of financial empire. The equivalent book in the Phiz illustration is Molière's comic masterpiece Tartuffe, in which the exploitative hypocrite is ultimately unmasked.

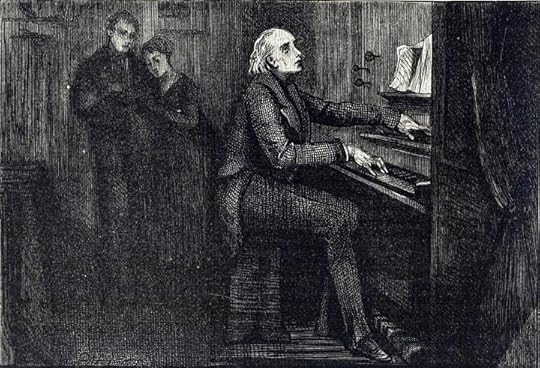

Touch the notes lightly, Tom

Chapter 54

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

What sounds are these that fall so grandly on the ear! What darkening room is this!

And that mild figure seated at an organ, who is he! Ah, Tom, dear Tom, old friend!

Thy head is prematurely grey, though Time has passed thee and our old association, Tom. But, in those sounds with which it is thy wont to bear the twilight company, the music of thy heart speaks out: the story of thy life relates itself.

Thy life is tranquil, calm, and happy, Tom. In the soft strain which ever and again comes stealing back upon the ear, the memory of thine old love may find a voice perhaps; but it is a pleasant, softened, whispering memory, like that in which we sometimes hold the dead, and does not pain or grieve thee, God be thanked.

Touch the notes lightly, Tom, as lightly as thou wilt, but never will thine hand fall half so lightly on that Instrument as on the head of thine old tyrant brought down very, very low; and never will it make as hollow a response to any touch of thine, as he does always.

Commentary: Melancholy Tom, Perpetual Bachelor

"I have a notion of finishing the book, with an apostrophe to Tom Pinch, playing the organ." — "Dickens to Phiz," June 1844.

The 1910 Furniss illustration of Tom Pinch at the organ, the book's last, is his re-interpretation of a similar illustration in the final monthly number of the Chapman and Hall serialization, Hablot Knight Browne's Frontispiece (see below) for Chapter 54 (Parts Nineteen-Twenty, July 1844 ). However, governing his much more complex composition according to the principles of Nemesis, Phiz focuses on Tom as the vortex's centre, surrounded by the other characters in the story. Furniss's approach is much closer to that of Fred Barnard in Tom's Reverie. For Dickens and Phiz, despite the fact that Tom's organ-playing has been purely incidental to the plot and his character up to this point, the central image of the frontispiece — one of the last illustrations executed but one of the first the reader of the volume edition would have seen on 16 July 1844, the central image, Tom at a church organ (indeed, all three chief interpretations concur on this setting), represents the inspired artist's contemplating his work, life, and relationships; it eventually will blend into illustrator R. W. Buss's memorial to Charles Dickens as a highly prolific author, Dickens' Dream which makes explicit the connection between the legion of characters that flowed from his pen and the man himself. The frontispiece brings closure to the story by supplying information as images rather than letterpress about the characters after the close of the novel, showing us, for example, that Mark Tapley marries the Blue Dragon and its proprietor, Mrs. Lupin (left of centre) in one of the many joyful "dance of life" scenes that crowd the left-hand margin (the right of the original steel engraving). Thus, the frontispiece continues the wrapper's program of contrasting figures and fortunes, but as a preview is rather more specific about the fates of the various characters.

The Furniss approach is less fanciful, but retains a certain sense of whimsy in its depiction of a suffering, self-pitying, disreputable Pecksniff (now an unkempt alcoholic) and of the contrasting, aetherial presence of Mary Graham, hovering above Tom's shoulder as his idealised woman and poetic muse. The actual Mary Graham, of course, has become Martin Chuzzlewit's wife and the object of Tom's unrequited devotion. Sadly, like Antonio at the conclusion of Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, he remains outside the enchanted marriage circle as he contemplates both what has been and what might have been. Furniss emphasizes Tom's bald pate, not merely to underscore his being middle-aged but single, but to endow him with a cerebral, philosophical disposition as in the accompanying text. Since the illustration occurs some five pages prior to the passage which Hammerton suggests through its title that it realizes, we read the composition proleptically, anticipating that the image means Tom never marries and finds fulfillment only in his art.

Whereas Ticknor-Fields mid-nineteenth-century American illustrator for the 1867 Diamond Edition, Sol Eytinge, Jr., has depicted Tom as an organ soloist in a series of illustrations in which the other characters consistently appear in groups or pairs, Fred Barnard in the 1872 Household Edition wood-engraving Tom's Reverie (see immediately below) places the emphasis on Tom's leaving behind his sister and brother-in-law (shadowy figures in the background) and entering another sphere as his hands assume very specific places on the twin keyboards. In other words, we might view Furniss's interpretation as an imaginative response to Barnard's atmospheric but realistic dark plate and Phiz's more fanciful invention.

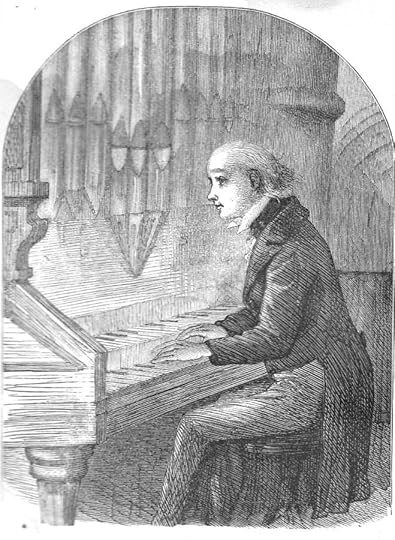

Tom Pinch

Chapter 54

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Commentary:

Dickens wrote to Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz") in June 1844, "I have a notion of finishing the book, with an apostrophe to Tom Pinch, playing the organ" (Pilgrim Letters 3). As Valerie Lester Browne points out in Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens (2004), the images embedded in the original frontispiece (and anticipating R. W. Buss's "Dickens Dream") suggest what will befall the various characters several years after the story's textual conclusion, as well as (to a lesser extent) their experiences and roles during the course of the narrative. Consequently, like many a modern preface, the original frontispiece, "Tom Pinch at the Organ", and Eytinge's scaled-down version (undoubtedly the medium of the woodcut did not permit the elaboration which Phiz was earlier able to effect in his 1844 steel engraving) are both better understood once the reader has completed the novel. However, Eytinge may have been targeting those mature readers who in 1867 would have recalled the novel as part of their youthful reading, and who would, therefore, have understood the significance of this musical portrait of the novel's "odd man out" in terms of the ultimate magic circle of romance. Sadly, unlike Phiz's, Eytinge's image fails to convey the prematurely balding Tom's sterling qualities or the fates of the various characters, and thereby regards merely Tom's exterior rather than his intense imaginative and emotional life.

Tom Pinch at the organ

Phiz

The Frontispiece for Martin Chuzzlewit: First Seen, But Last Created

"I have a notion of finishing the book, with an apostrophe to Tom Pinch, playing the organ." — "Dickens to Phiz," June 1844

Upon purchasing the last, "double" number of the novel the serial reader would have shortly have comprehended the precise relationship between the Frontispiece and the concluding chapter. However, for readers of the volume edition, whether a modern issue such as the Oxford World's Classics or a later nineteenth-century edition such as the Household Edition volume of 1872, the relationship between this initial picture and the final page of the novel would hardly be apparent. Although this frontispiece is one of the first images that the modern reader of The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit encounters, it was in fact one of the last engravings that Phiz produced over the nineteen-month run. Although the modern reader, then, would tend to regard the figures on the frontispiece as an overture or as the shades of things to come, in fact, as Valerie Lester Browne points out in Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens (2004), this image suggests what will befall the various characters several years after the story's textual conclusion, as well as (to a lesser extent) their experiences and roles during the course of the narrative. Consequently, like many a modern preface, this page is better understood once the reader has completed the novel.

Ornate and highly complicated, the frontispiece is the novel's first full-page illustration, but was published with the last "double" number. Hence, the engraving offers a highly informed "visual reading" of the entire novel and its trajectory into the near-future.

Knowing how the novel ends, Phiz now invites the reader to reflect on what has passed and to speculate on the fates of the principal characters, all of whom except Old Martin (whom Dickens mentions in the closing pages of the novel) make an appearance at least once. The central image, Tom Pinch at his organ, represents the artist contemplating his work, life, and relationships; it eventually will blend into illustrator R. W. Buss's memorial to the author, Dickens' Dream which makes explicit the connection between the legion of characters that flowed from his pen and the man himself. The frontispiece brings closure to the story by supplying information as images rather than letterpress about the characters after the close of the novel, showing us, for example, that Mark Tapley marries the Blue Dragon and its proprietor, Mrs. Lupin in one of the many joyful "dance of life" scenes that crowd the left-hand margin. Generally in a manner consistent with the governing principle of Nemesis or Poetic Justice, the bottom and right registers deal with scenes of punishment while the dancing figures in the left-hand register, including three married couples, enjoy the fruits of positive karma. In June 1844 Dickens outlined his vision of this final illustration for Phiz, who, as we shall see, provided most of the details and format from his own highly stimulated imagination:

And instead of saying what became of the people, as usual [in a novel], I shall suppose it to be all expressed in the sounds [of Tom Pinch's organ]; making the last swell of the Instrument a kind of expression of Tom's Heart. ["CD to Phiz," Pilgrim Letters ]

Tom's visions are at once hyperbolic, whimsical, and allegorical, providing a final complicated puzzle for the reader to solve. The reader must identify the figures from various visual clues (such as Pecksniff's hair and swelled head) and determine whether a given scene comes from within or beyond the frame of the narrative. Whether the condign punishments suffered by Pecksniff and Jonas are consistent with the gentle character and imagination of Dickens's "Abt Vogler" probably caused the Common Reader little concern.

In his extensive examination of Phiz's work on the Chuzzlewit illustration in his 1972 Dickens Studies Annual article that anticipated his chapter on the same subject in Dickens and Phiz (1978), Michael Steig explicates most of the scenes in Tom's toccata vision. Dickens has already provided us with a number of clues to decode the frontispiece. Whereas Tom, according to Dickens's letter of instruction to Phiz, has remained single, a slightly melancholy figure outside the charmed Shakespearean circle of young marrieds, John Westlock and Ruth Pinch, young Martin and Mary Graham, and Mark Tapley and the Widow Lupin are all happily married in a combined ceremony of royal rather than village proportions. in his will, old Martin has bequeathed Tom sufficient funds to fit his chamber with a magnificent organ worthy of a cathedral. Phiz has gone well beyond the scope of the "married happily ever after" ending summarized by Dickens in reiterating the narrative's chief themes and motifs, and commenting ironically on the fates of the less savoury characters. As Tom plays the two keyboards, miniature figures of his sister Ruth (holding a rolling pin suggestive of her having a purely domestic role) and brother-in-law John beat out the cadence for him. At the top of the organ pipes are Martin and Mary, dropping petals upon Tom's pensive head from a bridal wreath. Like Dickens with his half-closed eyes in Buss's "Dickens' Dream," Tom seems unaware of the figures that swirl about him, gazing inward.

The figures in the left-hand register move from top to bottom in the dance of life, suggested rather than articulated by Dickens in the closing pages of the novel. Immediately to the left of the miniature Ruth we see the Blue Dragon (animated as a fabulous creature rather depicted as a building) attended by two dancing flagons and joining hands with Mark and Mrs. Lupin. Below the dancing dragon is a portly female whose head is lost in a bandbox labelled "Gamp"; as she dances, she holds the hands of two dancing teapots, and is observed by three suffering patients and three crying infants. Thus, in spite of her being an exploitative deceiver, she has been accorded a spot among the blessed, perhaps because, as her collar suggests, she is blind to exterior reality and even her own condition, and is a figure of fun rather than of vice or crime. Self-deluded as well as abusing trust, she is to be ridiculed rather than subjected to more stringent punishment, a figure of Horatian satire.

Above the dancing dragon, another set of figures hardly suggestive of marital bliss — Poll Sweedlepipe and young Bailey — dance with birdcages and an animated dummy. At the lower left, Moddle is weeping and Merry teasing, contrasting the behaviors and attitudes of the three married couples to their right. in contrast to the general merriment of the dancers, at the bottom Phiz comments upon the destinies of the murderer, Jonas, and the plagiarist, Pecksniff. While smiling images of Pecksniff reminiscent of the smiling goblins in the Christmas story from The Pickwick Papers torment the hapless architect, to the right Jonas is surrounded by mirrors with moneybags tied to their frames. upbraiding him for his crime committed for the sake of money, the mirrors give back horrifying images of himself to Jonas. Appropriately, Pecksniff is suspended from the apex of a builder's tripod while a trowel scowls at him.

The most complicated exemplification of Nemesis is that of Jonas and his tormentors. Medusae, skeletons, and Fates threaten his prostrate figure with moneybags (alluding to his greed), daggers (signifying his murderous thoughts about his own father and Montague), and a pair of wineglasses (alluding to his earlier scheme to poison Anthony Chuzzlewit). Presumably, this scene of allegorical punishment transpires in a metaphysical space such as a Virgillian Tartarus (rather than in a Christian Hell). Immediately to the left of this group Jonas crosses a stile as his victim pleads for mercy, one of the few scenes that can be confidently located within the text (Ch. 47). Above this image of Jonas, Phiz deploys Latin mottos to comment upon Pecksniff's architectural and pedagogical swindling, compelling the viewer to reflect on the earliest incidents and illustrations in the novel. Perhaps, as Steig suggests, "Sic vos non vobis" (you labour, but not for yourselves) comments upon "Tom's condition of virtual slavery" when serving his apprenticeship, while "Si monumentum requiras [sic] circumspice" would seem to have multiple significance. First of all, the allusion to Sir Christopher Wren is surely meant as an ironic comment upon Pecksniff's architectural pretensions; and it may also echo Dickens' reference to the Latin inscription which appears upon the cornerstone of Pecksniff's plagiarized school building. But it also has a more specific meaning, related to the other Latin tag: Pecksniff is, in the picture, looking around at monuments of himself (a bust and a statue), but the real monument to Pecksniff is Tom Pinch, for whose virtues and talents Pecksniff receives the credit.

Thus, the frontispiece extends the disposition of rewards and punishments in the fifty-fourth chapter of the novel, and serves as a complement to rather than a realization of the final pages of the novel, a palpable demonstration of the pleasures that await the blessed (among whom the reader counts the amiable Tom) in this life and the torments that await the damned (specifically Jonas) in the next. The mild figure seated at the organ becomes a visual analogue for the young author seated at his writing desk, puzzling how to wind up this vast, sometimes unruly comic cavalcade, and recalling perhaps Milton's companion pastorals, "L'Allegro" and "il Penseroso."

Valerie Browne Lester singles out this frontispiece for particular praise as a collaborative effort of illustrator and author, although the initial conception was definitely Dickens's. In a letter to Phiz in June 1844, Dickens mused about the book's frontispiece, which would be one of Phiz's last plates for the book, although the first that purchasers of the volume edition would encounter:

'I shall break off the last chapter suddenly, and find Tom at his organ, a few years afterwards. And instead of saying what became of the people, as usual, I shall suppose it to be all expressed in the sounds; making the last swell of the Instrument a kind of expression of Tom's heart. . . . So the Frontispiece is Tom at his organ with a pensive face; and any little indications of his history rising out of it and floating about it, that you please; Tom as interesting and amiable as possible.

Lester decodes the swirling composition as a Cattermole-like fantasy or "abstraction" in which Phiz goes well beyond the fancy that Dickens suggested to make the organ-playing Tom a metaphor for the artist in any medium — "another image that presages" R. W. Buss's watercolor study Dickens's Dream (circa 1870). Among the myriad of characters floating about the musician are John Westlock, Ruth Pinch, Martin Chuzzlewit and Mary Graham, Mark Tapley and Mrs. Lupin, and "anthropomorphised musical notes drawn on manuscript pages". At the very bottom of the design half-a-dozen Pecksniffs play with masks, a suitable emblem for the constantly posing arch-hypocrite.

From "The Immortal Dickens" by George Gissing:

"I have endeavoured, in the progress of this tale" -- thus wrote Dickens in his original Preface to Martin Chuzzlewit -- "to resist the temptation of the current monthly number, and to keep a steadier eye upon the general purpose and design." The temptation of the current monthly number none the less disastrously prevailed. It could only be overcome in one way, by elaborating a scheme of the book in hand before sitting down to write it; and this was opposed to the method of Dickens's imagination. Oddly enough, his remark prefaced the one of all his novels in which this defect of artistic structure is most glaringly obvious; no great work of fiction is so ill put together as Martin Chuzzlewit. But for this imperfection, the book would perhaps rank as his finest. In it he displays the fullness of his presentative power, the ripeness of his humour, the richest flow of his satiric vivacity, and the culmination of his melodramatic vigour. Wrought into a shapely edifice of fiction, such qualities would have announced an incontestable masterpiece. As it is, we admire and enjoy with intervals of impatience. The novel is naught; the salient features of the book are priceless.