The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Dombey and Son

>

D & S Chapters 5-7

In Chapter Six, with the title "Paul’s Second Deprivation", definitely not a good sign, we are on our way with Richards, Susan Nipper, Florence and little Paul on our way to the home of the Toodle's. We start with rather alarming description of where they are going:

The first shock of a great earthquake had, just at that period, rent the whole neighbourhood to its centre. Traces of its course were visible on every side. Houses were knocked down; streets broken through and stopped; deep pits and trenches dug in the ground; enormous heaps of earth and clay thrown up; buildings that were undermined and shaking, propped by great beams of wood. Here, a chaos of carts, overthrown and jumbled together, lay topsy-turvy at the bottom of a steep unnatural hill; there, confused treasures of iron soaked and rusted in something that had accidentally become a pond. Everywhere were bridges that led nowhere; thoroughfares that were wholly impassable; Babel towers of chimneys, wanting half their height; temporary wooden houses and enclosures, in the most unlikely situations; carcases of ragged tenements, and fragments of unfinished walls and arches, and piles of scaffolding, and wildernesses of bricks, and giant forms of cranes, and tripods straddling above nothing. There were a hundred thousand shapes and substances of incompleteness, wildly mingled out of their places, upside down, burrowing in the earth, aspiring in the air, mouldering in the water, and unintelligible as any dream. Hot springs and fiery eruptions, the usual attendants upon earthquakes, lent their contributions of confusion to the scene. Boiling water hissed and heaved within dilapidated walls; whence, also, the glare and roar of flames came issuing forth; and mounds of ashes blocked up rights of way, and wholly changed the law and custom of the neighbourhood.

In short, the yet unfinished and unopened Railroad was in progress; and, from the very core of all this dire disorder, trailed smoothly away, upon its mighty course of civilisation and improvement.

It doesn't sound like Dickens was a fan of the railroad, I wouldn't be either from that description, and that was before he was in a train wreck. But this is the direction of the Toodle's home, so it is this direction we go. Arriving at the house, they spend the afternoon visiting with Richard's sister and the smaller children, but her oldest son is still in school, and her husband is working, and won't be back to the evening. So, when the visit is over, they walk another way back, hoping to see her son, which they do. But things aren't going very well for the boy. It seems that since he started wearing the Charitable Grinders costume, the youth of the streets harassed him constantly. We're told he had been stoned in the street, overthrown in gutters, bespattered with mud, flattened against posts, handled and pinched. It so happened that at this moment a small party of boys had just rushed upon him, when Polly seeing this, handed little Paul to Susan and ran to the rescue. Things were confusing with boys yelling, Richards running, carriages passing, people running, it all scared Florence and she screamed and ran. When she finally stopped running she was all alone, all alone except for an old woman who told Florence her name was "good Mrs. Brown" leaving Florence wondering what bad Mrs. Brown would be like, and could take her to Susan. Of course she doesn't, she takes her down one street and up another of the worst streets in the city of course, to her own home and having her take off her dress, bonnet, and shoes, puts rags on her, tells her she could have killed her at any time, takes her out to a busy street, and leaves her there. She's mean Mrs. Brown, that's what I'm calling her.

And now Walter once again enters the story, for after wandering the street for hours, she comes upon Walter who takes her to his uncle's house. On their way there we meet Mr. Carker, one of them anyway, for the first time:

‘Why, I think it’s Mr Carker,’ said Walter. ‘Carker in our House. Not Carker our Manager, Miss Dombey—the other Carker; the Junior—Halloa! Mr Carker!’

‘Is that Walter Gay?’ said the other, stopping and returning. ‘I couldn’t believe it, with such a strange companion.’

As he stood near a lamp, listening with surprise to Walter’s hurried explanation, he presented a remarkable contrast to the two youthful figures arm-in-arm before him. He was not old, but his hair was white; his body was bent, or bowed as if by the weight of some great trouble: and there were deep lines in his worn and melancholy face. The fire of his eyes, the expression of his features, the very voice in which he spoke, were all subdued and quenched, as if the spirit within him lay in ashes. He was respectably, though very plainly dressed, in black; but his clothes, moulded to the general character of his figure, seemed to shrink and abase themselves upon him, and to join in the sorrowful solicitation which the whole man from head to foot expressed, to be left unnoticed, and alone in his humility.

And yet his interest in youth and hopefulness was not extinguished with the other embers of his soul, for he watched the boy’s earnest countenance as he spoke with unusual sympathy, though with an inexplicable show of trouble and compassion, which escaped into his looks, however hard he strove to hold it prisoner. When Walter, in conclusion, put to him the question he had put to Florence, he still stood glancing at him with the same expression, as if he had read some fate upon his face, mournfully at variance with its present brightness.

‘What do you advise, Mr Carker?’ said Walter, smiling. ‘You always give me good advice, you know, when you do speak to me. That’s not often, though.’

‘I think your own idea is the best,’ he answered: looking from Florence to Walter, and back again.

‘Mr Carker,’ said Walter, brightening with a generous thought, ‘Come! Here’s a chance for you. Go you to Mr Dombey’s, and be the messenger of good news. It may do you some good, Sir. I’ll remain at home. You shall go.’

‘I!’ returned the other.

‘Yes. Why not, Mr Carker?’ said the boy.

He merely shook him by the hand in answer; he seemed in a manner ashamed and afraid even to do that; and bidding him good-night, and advising him to make haste, turned away.

‘Come, Miss Dombey,’ said Walter, looking after him as they turned away also, ‘we’ll go to my Uncle’s as quick as we can. Did you ever hear Mr Dombey speak of Mr Carker the Junior, Miss Florence?’

‘No,’ returned the child, mildly, ‘I don’t often hear Papa speak.’

‘Ah! true! more shame for him,’ thought Walter. After a minute’s pause, during which he had been looking down upon the gentle patient little face moving on at his side, he said, ‘The strangest man, Mr Carker the Junior is, Miss Florence, that ever you heard of. If you could understand what an extraordinary interest he takes in me, and yet how he shuns me and avoids me; and what a low place he holds in our office, and how he is never advanced, and never complains, though year after year he sees young men passed over his head, and though his brother (younger than he is), is our head Manager, you would be as much puzzled about him as I am.’

I copied that because I want to remember our first glimpse of Mr. Carker the Junior, although why he is called the Junior if he is the older brother I don't yet know. I also want to remember that Florence told Walter that she doesn't often hear her father speak. I wonder if he'll regret that someday. Anyway, once Florence is with Solomon Gills, who gets her something to eat, and drink, sits her by the fire to get warm, rubs her feet, and other kind things, Walter goes to Mr. Dombey's house to let them know where she is. And soon Susan is there bringing Florence new clothing, and before long they are ready to leave:

‘Good-night!’ said Florence, running up to Solomon. ‘You have been very good to me.’

Old Sol was quite delighted, and kissed her like her grand-father.

‘Good-night, Walter! Good-bye!’ said Florence.

‘Good-bye!’ said Walter, giving both his hands.

‘I’ll never forget you,’ pursued Florence. ‘No! indeed I never will. Good-bye, Walter!’

In the innocence of her grateful heart, the child lifted up her face to his. Walter, bending down his own, raised it again, all red and burning; and looked at Uncle Sol, quite sheepishly.

‘Where’s Walter?’ ‘Good-night, Walter!’ ‘Good-bye, Walter!’ ‘Shake hands once more, Walter!’ This was still Florence’s cry, after she was shut up with her little maid, in the coach. And when the coach at length moved off, Walter on the door-step gaily returned the waving of her handkerchief, while the wooden Midshipman behind him seemed, like himself, intent upon that coach alone, excluding all the other passing coaches from his observation.

So, is there hope for Walter and Florence somewhere down the line? I don't know, but there is no hope for Richards.

‘Louisa!’ said Mr Dombey. ‘It is not necessary to prolong these observations. The woman is discharged and paid. You leave this house, Richards, for taking my son—my son,’ said Mr Dombey, emphatically repeating these two words, ‘into haunts and into society which are not to be thought of without a shudder. As to the accident which befell Miss Florence this morning, I regard that as, in one great sense, a happy and fortunate circumstance; inasmuch as, but for that occurrence, I never could have known—and from your own lips too—of what you had been guilty. I think, Louisa, the other nurse, the young person,’ here Miss Nipper sobbed aloud, ‘being so much younger, and necessarily influenced by Paul’s nurse, may remain. Have the goodness to direct that this woman’s coach is paid to’—Mr Dombey stopped and winced—‘to Staggs’s Gardens.’

Polly moved towards the door, with Florence holding to her dress, and crying to her in the most pathetic manner not to go away. It was a dagger in the haughty father’s heart, an arrow in his brain, to see how the flesh and blood he could not disown clung to this obscure stranger, and he sitting by. Not that he cared to whom his daughter turned, or from whom turned away. The swift sharp agony struck through him, as he thought of what his son might do.

His son cried lustily that night, at all events. Sooth to say, poor Paul had better reason for his tears than sons of that age often have, for he had lost his second mother—his first, so far as he knew—by a stroke as sudden as that natural affliction which had darkened the beginning of his life. At the same blow, his sister too, who cried herself to sleep so mournfully, had lost as good and true a friend. But that is quite beside the question. Let us waste no words about it.

The first shock of a great earthquake had, just at that period, rent the whole neighbourhood to its centre. Traces of its course were visible on every side. Houses were knocked down; streets broken through and stopped; deep pits and trenches dug in the ground; enormous heaps of earth and clay thrown up; buildings that were undermined and shaking, propped by great beams of wood. Here, a chaos of carts, overthrown and jumbled together, lay topsy-turvy at the bottom of a steep unnatural hill; there, confused treasures of iron soaked and rusted in something that had accidentally become a pond. Everywhere were bridges that led nowhere; thoroughfares that were wholly impassable; Babel towers of chimneys, wanting half their height; temporary wooden houses and enclosures, in the most unlikely situations; carcases of ragged tenements, and fragments of unfinished walls and arches, and piles of scaffolding, and wildernesses of bricks, and giant forms of cranes, and tripods straddling above nothing. There were a hundred thousand shapes and substances of incompleteness, wildly mingled out of their places, upside down, burrowing in the earth, aspiring in the air, mouldering in the water, and unintelligible as any dream. Hot springs and fiery eruptions, the usual attendants upon earthquakes, lent their contributions of confusion to the scene. Boiling water hissed and heaved within dilapidated walls; whence, also, the glare and roar of flames came issuing forth; and mounds of ashes blocked up rights of way, and wholly changed the law and custom of the neighbourhood.

In short, the yet unfinished and unopened Railroad was in progress; and, from the very core of all this dire disorder, trailed smoothly away, upon its mighty course of civilisation and improvement.

It doesn't sound like Dickens was a fan of the railroad, I wouldn't be either from that description, and that was before he was in a train wreck. But this is the direction of the Toodle's home, so it is this direction we go. Arriving at the house, they spend the afternoon visiting with Richard's sister and the smaller children, but her oldest son is still in school, and her husband is working, and won't be back to the evening. So, when the visit is over, they walk another way back, hoping to see her son, which they do. But things aren't going very well for the boy. It seems that since he started wearing the Charitable Grinders costume, the youth of the streets harassed him constantly. We're told he had been stoned in the street, overthrown in gutters, bespattered with mud, flattened against posts, handled and pinched. It so happened that at this moment a small party of boys had just rushed upon him, when Polly seeing this, handed little Paul to Susan and ran to the rescue. Things were confusing with boys yelling, Richards running, carriages passing, people running, it all scared Florence and she screamed and ran. When she finally stopped running she was all alone, all alone except for an old woman who told Florence her name was "good Mrs. Brown" leaving Florence wondering what bad Mrs. Brown would be like, and could take her to Susan. Of course she doesn't, she takes her down one street and up another of the worst streets in the city of course, to her own home and having her take off her dress, bonnet, and shoes, puts rags on her, tells her she could have killed her at any time, takes her out to a busy street, and leaves her there. She's mean Mrs. Brown, that's what I'm calling her.

And now Walter once again enters the story, for after wandering the street for hours, she comes upon Walter who takes her to his uncle's house. On their way there we meet Mr. Carker, one of them anyway, for the first time:

‘Why, I think it’s Mr Carker,’ said Walter. ‘Carker in our House. Not Carker our Manager, Miss Dombey—the other Carker; the Junior—Halloa! Mr Carker!’

‘Is that Walter Gay?’ said the other, stopping and returning. ‘I couldn’t believe it, with such a strange companion.’

As he stood near a lamp, listening with surprise to Walter’s hurried explanation, he presented a remarkable contrast to the two youthful figures arm-in-arm before him. He was not old, but his hair was white; his body was bent, or bowed as if by the weight of some great trouble: and there were deep lines in his worn and melancholy face. The fire of his eyes, the expression of his features, the very voice in which he spoke, were all subdued and quenched, as if the spirit within him lay in ashes. He was respectably, though very plainly dressed, in black; but his clothes, moulded to the general character of his figure, seemed to shrink and abase themselves upon him, and to join in the sorrowful solicitation which the whole man from head to foot expressed, to be left unnoticed, and alone in his humility.

And yet his interest in youth and hopefulness was not extinguished with the other embers of his soul, for he watched the boy’s earnest countenance as he spoke with unusual sympathy, though with an inexplicable show of trouble and compassion, which escaped into his looks, however hard he strove to hold it prisoner. When Walter, in conclusion, put to him the question he had put to Florence, he still stood glancing at him with the same expression, as if he had read some fate upon his face, mournfully at variance with its present brightness.

‘What do you advise, Mr Carker?’ said Walter, smiling. ‘You always give me good advice, you know, when you do speak to me. That’s not often, though.’

‘I think your own idea is the best,’ he answered: looking from Florence to Walter, and back again.

‘Mr Carker,’ said Walter, brightening with a generous thought, ‘Come! Here’s a chance for you. Go you to Mr Dombey’s, and be the messenger of good news. It may do you some good, Sir. I’ll remain at home. You shall go.’

‘I!’ returned the other.

‘Yes. Why not, Mr Carker?’ said the boy.

He merely shook him by the hand in answer; he seemed in a manner ashamed and afraid even to do that; and bidding him good-night, and advising him to make haste, turned away.

‘Come, Miss Dombey,’ said Walter, looking after him as they turned away also, ‘we’ll go to my Uncle’s as quick as we can. Did you ever hear Mr Dombey speak of Mr Carker the Junior, Miss Florence?’

‘No,’ returned the child, mildly, ‘I don’t often hear Papa speak.’

‘Ah! true! more shame for him,’ thought Walter. After a minute’s pause, during which he had been looking down upon the gentle patient little face moving on at his side, he said, ‘The strangest man, Mr Carker the Junior is, Miss Florence, that ever you heard of. If you could understand what an extraordinary interest he takes in me, and yet how he shuns me and avoids me; and what a low place he holds in our office, and how he is never advanced, and never complains, though year after year he sees young men passed over his head, and though his brother (younger than he is), is our head Manager, you would be as much puzzled about him as I am.’

I copied that because I want to remember our first glimpse of Mr. Carker the Junior, although why he is called the Junior if he is the older brother I don't yet know. I also want to remember that Florence told Walter that she doesn't often hear her father speak. I wonder if he'll regret that someday. Anyway, once Florence is with Solomon Gills, who gets her something to eat, and drink, sits her by the fire to get warm, rubs her feet, and other kind things, Walter goes to Mr. Dombey's house to let them know where she is. And soon Susan is there bringing Florence new clothing, and before long they are ready to leave:

‘Good-night!’ said Florence, running up to Solomon. ‘You have been very good to me.’

Old Sol was quite delighted, and kissed her like her grand-father.

‘Good-night, Walter! Good-bye!’ said Florence.

‘Good-bye!’ said Walter, giving both his hands.

‘I’ll never forget you,’ pursued Florence. ‘No! indeed I never will. Good-bye, Walter!’

In the innocence of her grateful heart, the child lifted up her face to his. Walter, bending down his own, raised it again, all red and burning; and looked at Uncle Sol, quite sheepishly.

‘Where’s Walter?’ ‘Good-night, Walter!’ ‘Good-bye, Walter!’ ‘Shake hands once more, Walter!’ This was still Florence’s cry, after she was shut up with her little maid, in the coach. And when the coach at length moved off, Walter on the door-step gaily returned the waving of her handkerchief, while the wooden Midshipman behind him seemed, like himself, intent upon that coach alone, excluding all the other passing coaches from his observation.

So, is there hope for Walter and Florence somewhere down the line? I don't know, but there is no hope for Richards.

‘Louisa!’ said Mr Dombey. ‘It is not necessary to prolong these observations. The woman is discharged and paid. You leave this house, Richards, for taking my son—my son,’ said Mr Dombey, emphatically repeating these two words, ‘into haunts and into society which are not to be thought of without a shudder. As to the accident which befell Miss Florence this morning, I regard that as, in one great sense, a happy and fortunate circumstance; inasmuch as, but for that occurrence, I never could have known—and from your own lips too—of what you had been guilty. I think, Louisa, the other nurse, the young person,’ here Miss Nipper sobbed aloud, ‘being so much younger, and necessarily influenced by Paul’s nurse, may remain. Have the goodness to direct that this woman’s coach is paid to’—Mr Dombey stopped and winced—‘to Staggs’s Gardens.’

Polly moved towards the door, with Florence holding to her dress, and crying to her in the most pathetic manner not to go away. It was a dagger in the haughty father’s heart, an arrow in his brain, to see how the flesh and blood he could not disown clung to this obscure stranger, and he sitting by. Not that he cared to whom his daughter turned, or from whom turned away. The swift sharp agony struck through him, as he thought of what his son might do.

His son cried lustily that night, at all events. Sooth to say, poor Paul had better reason for his tears than sons of that age often have, for he had lost his second mother—his first, so far as he knew—by a stroke as sudden as that natural affliction which had darkened the beginning of his life. At the same blow, his sister too, who cried herself to sleep so mournfully, had lost as good and true a friend. But that is quite beside the question. Let us waste no words about it.

Well this is interesting, it seems Miss Tox is so important to our story that in chapter 7 we even get to go see where she lives, and meet another character who seems to have his own ideas about Miss Tox. We're told that Miss Tox inhabited a dark little house that was squeezed into a fashionable neighborhood at the west end of town where it stood in the shade like a poor relation of the great street round the corner. The name of this place is Princess's Place, in which was Princess Chapel, and The Princess Arms. In another private house lived a blue-face Major, who could see Miss Tox's rooms from his window, and between them an occasional interchange of newspapers and pamphlets would take place. As for Miss Tox's home we're told this:

The dingy tenement inhabited by Miss Tox was her own; having been devised and bequeathed to her by the deceased owner of the fishy eye in the locket, of whom a miniature portrait, with a powdered head and a pigtail, balanced the kettle-holder on opposite sides of the parlour fireplace. The greater part of the furniture was of the powdered-head and pig-tail period: comprising a plate-warmer, always languishing and sprawling its four attenuated bow legs in somebody’s way; and an obsolete harpsichord, illuminated round the maker’s name with a painted garland of sweet peas.

Who's the guy in the locket who left her the house? Her father, someone else, am I supposed to know? If I am, I'm sorry but I don't. As for the Major:

Although Major Bagstock had arrived at what is called in polite literature, the grand meridian of life, and was proceeding on his journey downhill with hardly any throat, and a very rigid pair of jaw-bones, and long-flapped elephantine ears, and his eyes and complexion in the state of artificial excitement already mentioned, he was mightily proud of awakening an interest in Miss Tox, and tickled his vanity with the fiction that she was a splendid woman who had her eye on him. This he had several times hinted at the club: in connexion with little jocularities, of which old Joe Bagstock, old Joey Bagstock, old J. Bagstock, old Josh Bagstock, or so forth, was the perpetual theme: it being, as it were, the Major’s stronghold and donjon-keep of light humour, to be on the most familiar terms with his own name.

But now he found that Miss Tox seems to have forgotten him. She began to forget him soon after she discovered the Toodle family, she forgot him even more after the christening, something or somebody had superseded him. Sometime after he began to notice this change in her, he came upon her in the street and mentioned he hadn't seen her at her window lately and asked if she had been out of town. Her reply was that no, she hadn't been out of town, but her time is nearly all devoted to some very intimate friends and she has no time to spare. The Major decides that she is acting this way as a means of trapping him, she is plotting and snaring, digging pitfalls. But he says, she won't catch him and chuckles for the rest of the day. And yet the days go by and still he sees nothing of Miss Tox. Then one days while looking out his window he sees Miss Tox with a baby. And not only once, but day after day this baby returns, two, three, or four times a week. We're told:

The perseverance with which she walked out of Princess’s Place to fetch this baby and its nurse, and walked back with them, and walked home with them again, and continually mounted guard over them; and the perseverance with which she nursed it herself, and fed it, and played with it, and froze its young blood with airs upon the harpsichord, was extraordinary. At about this same period too, she was seized with a passion for looking at a certain bracelet; also with a passion for looking at the moon, of which she would take long observations from her chamber window. But whatever she looked at; sun, moon, stars, or bracelet; she looked no more at the Major. And the Major whistled, and stared, and wondered, and dodged about his room, and could make nothing of it.

So what will happen with our Major? I don't know, but I'm off to look for illustrations, and will end with the end of the chapter:

If the Major could have known how many hopes and ventures, what a multitude of plans and speculations, rested on that baby head; and could have seen them hovering, in all their heterogeneous confusion and disorder, round the puckered cap of the unconscious little Paul; he might have stared indeed. Then would he have recognised, among the crowd, some few ambitious motes and beams belonging to Miss Tox; then would he perhaps have understood the nature of that lady’s faltering investment in the Dombey Firm.

If the child himself could have awakened in the night, and seen, gathered about his cradle-curtains, faint reflections of the dreams that other people had of him, they might have scared him, with good reason. But he slumbered on, alike unconscious of the kind intentions of Miss Tox, the wonder of the Major, the early sorrows of his sister, and the stern visions of his father; and innocent that any spot of earth contained a Dombey or a Son.

The dingy tenement inhabited by Miss Tox was her own; having been devised and bequeathed to her by the deceased owner of the fishy eye in the locket, of whom a miniature portrait, with a powdered head and a pigtail, balanced the kettle-holder on opposite sides of the parlour fireplace. The greater part of the furniture was of the powdered-head and pig-tail period: comprising a plate-warmer, always languishing and sprawling its four attenuated bow legs in somebody’s way; and an obsolete harpsichord, illuminated round the maker’s name with a painted garland of sweet peas.

Who's the guy in the locket who left her the house? Her father, someone else, am I supposed to know? If I am, I'm sorry but I don't. As for the Major:

Although Major Bagstock had arrived at what is called in polite literature, the grand meridian of life, and was proceeding on his journey downhill with hardly any throat, and a very rigid pair of jaw-bones, and long-flapped elephantine ears, and his eyes and complexion in the state of artificial excitement already mentioned, he was mightily proud of awakening an interest in Miss Tox, and tickled his vanity with the fiction that she was a splendid woman who had her eye on him. This he had several times hinted at the club: in connexion with little jocularities, of which old Joe Bagstock, old Joey Bagstock, old J. Bagstock, old Josh Bagstock, or so forth, was the perpetual theme: it being, as it were, the Major’s stronghold and donjon-keep of light humour, to be on the most familiar terms with his own name.

But now he found that Miss Tox seems to have forgotten him. She began to forget him soon after she discovered the Toodle family, she forgot him even more after the christening, something or somebody had superseded him. Sometime after he began to notice this change in her, he came upon her in the street and mentioned he hadn't seen her at her window lately and asked if she had been out of town. Her reply was that no, she hadn't been out of town, but her time is nearly all devoted to some very intimate friends and she has no time to spare. The Major decides that she is acting this way as a means of trapping him, she is plotting and snaring, digging pitfalls. But he says, she won't catch him and chuckles for the rest of the day. And yet the days go by and still he sees nothing of Miss Tox. Then one days while looking out his window he sees Miss Tox with a baby. And not only once, but day after day this baby returns, two, three, or four times a week. We're told:

The perseverance with which she walked out of Princess’s Place to fetch this baby and its nurse, and walked back with them, and walked home with them again, and continually mounted guard over them; and the perseverance with which she nursed it herself, and fed it, and played with it, and froze its young blood with airs upon the harpsichord, was extraordinary. At about this same period too, she was seized with a passion for looking at a certain bracelet; also with a passion for looking at the moon, of which she would take long observations from her chamber window. But whatever she looked at; sun, moon, stars, or bracelet; she looked no more at the Major. And the Major whistled, and stared, and wondered, and dodged about his room, and could make nothing of it.

So what will happen with our Major? I don't know, but I'm off to look for illustrations, and will end with the end of the chapter:

If the Major could have known how many hopes and ventures, what a multitude of plans and speculations, rested on that baby head; and could have seen them hovering, in all their heterogeneous confusion and disorder, round the puckered cap of the unconscious little Paul; he might have stared indeed. Then would he have recognised, among the crowd, some few ambitious motes and beams belonging to Miss Tox; then would he perhaps have understood the nature of that lady’s faltering investment in the Dombey Firm.

If the child himself could have awakened in the night, and seen, gathered about his cradle-curtains, faint reflections of the dreams that other people had of him, they might have scared him, with good reason. But he slumbered on, alike unconscious of the kind intentions of Miss Tox, the wonder of the Major, the early sorrows of his sister, and the stern visions of his father; and innocent that any spot of earth contained a Dombey or a Son.

Paul's christening is a very chilling affair indeed, Kim, and the fact that Mr. Dombey chooses Miss Tox (and the Chicks), probably because their - in the eyes of Mr. Dombey - insignificance shows the haughtiness of our man. He thinks that the choice of godfather and godmother is often a strategical one in the sense of establishing or strengthening connections between families - like the Habsburg dynasty used to do - and he says,

"'[...]The Kind of foreign help which people usually seek for their children, I can afford to despise; being above it, I hope. [...]'"

A little bit later, in his monologue, he says,

"'[...] Until then, I am enough for him, perhaps, and all in all. I have no wish that people should step in between us. [...]'"

The first quotation shows a very high degree of hubris, and we all know where hubris leads - in books at least. The second quotation marks out Mr. Dombey as rather jealous or possessive with respect to little Paul. When he says that he does not like anyone to step between him and his son, does this also go for his daughter? Is she, neither, supposed to "step in between him and his son"? Apart from that, it is a very tragical detail, seeing how little affection, warmth and love Mr. Dombey has to give for fear of, as we say in German, sich einen Zacken aus der Krone zu brechen, i.e. breaking a spike out of his crown.

"'[...]The Kind of foreign help which people usually seek for their children, I can afford to despise; being above it, I hope. [...]'"

A little bit later, in his monologue, he says,

"'[...] Until then, I am enough for him, perhaps, and all in all. I have no wish that people should step in between us. [...]'"

The first quotation shows a very high degree of hubris, and we all know where hubris leads - in books at least. The second quotation marks out Mr. Dombey as rather jealous or possessive with respect to little Paul. When he says that he does not like anyone to step between him and his son, does this also go for his daughter? Is she, neither, supposed to "step in between him and his son"? Apart from that, it is a very tragical detail, seeing how little affection, warmth and love Mr. Dombey has to give for fear of, as we say in German, sich einen Zacken aus der Krone zu brechen, i.e. breaking a spike out of his crown.

There is a mystery described in Chapter 5 which I cannot yet explain to myself: After discussing Miss Tox with his sister Louisa, Mr. Dombey chances to look at his late wife's writing-desk, and he unlocks it with a key he carries in his pocket - after carefully securing the doors to the room. He then takes a letter out of the desk and reads it with something less than his usual arrogant demeanour. After the perusal of the letter, he tears it into little pieces which he stuffs into his pocket lest they should be reassembled by anyone.

This letter upsets him so much that this evening he refrains from having little Paul taken to him, but he spends the whole evening on his own, lost in gloomy thought.

Now - what kind of letter might this have been? Did Mrs. Dombey have a lover before marrying Dombey?

This letter upsets him so much that this evening he refrains from having little Paul taken to him, but he spends the whole evening on his own, lost in gloomy thought.

Now - what kind of letter might this have been? Did Mrs. Dombey have a lover before marrying Dombey?

Did you notice what good things Mrs. Chicks says of her niece? She goes like this, "Florence will never, never, never be a Dombey [...], not if she lives to be a thousand years old."

Let's hope she will be right.

Let's hope she will be right.

Poor kids, it is all so gloomy.

At least something interesting happened again, it feels like Dickens wants to keep up a fast pace! It was bad for little Florence to be lost, but it turns out even worse, one of the few kind people in her life is send away because of it. However, she at least got new friends in return, when Paul now has to make do with Tox. For who else woukd the baby in chapter 7 be, when she's his godmother?

At least something interesting happened again, it feels like Dickens wants to keep up a fast pace! It was bad for little Florence to be lost, but it turns out even worse, one of the few kind people in her life is send away because of it. However, she at least got new friends in return, when Paul now has to make do with Tox. For who else woukd the baby in chapter 7 be, when she's his godmother?

Tristram wrote: "There is a mystery described in Chapter 5 which I cannot yet explain to myself: After discussing Miss Tox with his sister Louisa, Mr. Dombey chances to look at his late wife's writing-desk, and he ..."

Hi Tristram

Before the part where Dombey tears his late wife’s letter we read of Dombey’s “majesty and grandeur” and of Dombey’s secret feelings and “indescribable distrust of anybody stepping in between himself and his son.”

We read that Dombey had looked upon the cabinet before this day. We know that Dombey has the key to unlock it. We learn that as he read the contents of the letter he held his breath, he sat down, and he rested his head upon one hand. Whatever the contents of the letter, it took a great effort on Dombey’s part not to reveal any emotions during its reading. He then tears the letter up, carefully, but certainly into little bits and ensures that no one else would ever read it.

A great mystery. So, here’s a suggestion from Sherlock Peter. In the letter to her husband Mrs Dombey has told him that should she not live after giving birth, and the child was female, that it is her wish that he mend his ways and emotions towards their two female children. On the other hand, if the baby is a boy, that Dombey would not neglect or ignore Florence as he presently does and give all his love to their new baby son.

I hypothesize this because in the next paragraphs Miss Tox and Louisa discuss Florence. Louisa says Florence “will never, never, never be a Dombey.”

Whatever the contents of the letter, it is clear that Dombey has no interest in any of his wife’s words from beyond the grave.

Hi Tristram

Before the part where Dombey tears his late wife’s letter we read of Dombey’s “majesty and grandeur” and of Dombey’s secret feelings and “indescribable distrust of anybody stepping in between himself and his son.”

We read that Dombey had looked upon the cabinet before this day. We know that Dombey has the key to unlock it. We learn that as he read the contents of the letter he held his breath, he sat down, and he rested his head upon one hand. Whatever the contents of the letter, it took a great effort on Dombey’s part not to reveal any emotions during its reading. He then tears the letter up, carefully, but certainly into little bits and ensures that no one else would ever read it.

A great mystery. So, here’s a suggestion from Sherlock Peter. In the letter to her husband Mrs Dombey has told him that should she not live after giving birth, and the child was female, that it is her wish that he mend his ways and emotions towards their two female children. On the other hand, if the baby is a boy, that Dombey would not neglect or ignore Florence as he presently does and give all his love to their new baby son.

I hypothesize this because in the next paragraphs Miss Tox and Louisa discuss Florence. Louisa says Florence “will never, never, never be a Dombey.”

Whatever the contents of the letter, it is clear that Dombey has no interest in any of his wife’s words from beyond the grave.

In Chapter 6 Florence becomes lost on her way home and runs into Good Mrs Brown - who is not so good. Mrs Brown forces Florence to take her good clothes off and is given “wretched substitutes in their place.” Florence was moments from having her hair cut, but Mrs Brown remembers her own daughter’s hair and relents. Florence is released by Mrs Brown and resumes her search for her home. She runs into Walter who assures her she is “as safe as if you were guarded by a whole boat’s crew of picked men from a man-of-war.” Walter then places a shoe much like, Dickens recounts, “as the Prince in the story might have fitted Cinderella’s slipper on.” Walter takes her to the wooden Midshipman.

What a great packed scene of events. Florence is dressed in rags because an evil person has stripped her of her outward identity which is symbolized by her clothes. The rags she now wears is an outer representation of her impoverished state living with a father who does not love her.

A handsome young man comes to her rescue, fits a shoe onto to tiny foot, and leads her to a safe haven while assuring her that his protection is as great as a crew of sailors. Here we have a conflation of the fairytale of Cinderella, the rescue by a young protector, and the discovery of a safe haven. The reference to sailors and the sea echoes the maritime business of Dombey and Son.

Florence has found another home, a place of safety. While she will not live there at this point in time, the wooden Midshipman is a beacon for her. It is a place with people who will take care of her regardless of her situation. What has been lost in Dombey’s mansion has been found in the humble wooden Midshipman.

What a great packed scene of events. Florence is dressed in rags because an evil person has stripped her of her outward identity which is symbolized by her clothes. The rags she now wears is an outer representation of her impoverished state living with a father who does not love her.

A handsome young man comes to her rescue, fits a shoe onto to tiny foot, and leads her to a safe haven while assuring her that his protection is as great as a crew of sailors. Here we have a conflation of the fairytale of Cinderella, the rescue by a young protector, and the discovery of a safe haven. The reference to sailors and the sea echoes the maritime business of Dombey and Son.

Florence has found another home, a place of safety. While she will not live there at this point in time, the wooden Midshipman is a beacon for her. It is a place with people who will take care of her regardless of her situation. What has been lost in Dombey’s mansion has been found in the humble wooden Midshipman.

I Just started chapter 5, but before I go on I just want to say Dumby is so insufferable that I don't know how he doesn't run away from himself. It's getting really ripe anywhere near him.

I Just started chapter 5, but before I go on I just want to say Dumby is so insufferable that I don't know how he doesn't run away from himself. It's getting really ripe anywhere near him. Right now I'm thinking of Dumby locked in the wedding room with Mish Haversham or maybe he's drop kicked into the sea by Miss Wade of Little Dorrit fame. Or, better yet, he explodes into nothingness like the collector old guy in Bleak House.

Chapter 5

Chapter 5What an ominous christening! It was cold and gloomy, and Paul cried like he sensed a bad omen. A christening is supposed to be a blessing, but this was a curse.

I don't blame Richards for having mixed feelings about the Charitable Grinders. The name itself doesn't sound friendly. Plus, Dombey never asked Richards' permission to send her son there. He just signed the boy up and sprung the news on the mother, thinking she'd be grateful. Dombey gave what I call "condescending charity," a form of charity not from the heart, but from thinking a person is inferior and needs reform.

Chapter 6

Chapter 6Mrs. Brown shocked me with her creepiness, especially when she made Florence de-robe and put on rags. I wondered if this was "fall from grace" imagery. I noticed the fairy tale motif, with Mrs. Brown as the "ogress," and Walter as the prince/rescuer of Florence.

The end of the chapter was so sad. Poor Paul and poor Florence for losing their beloved nanny!

Interesting how hurt Dombey was, seeing his kids love someone else. Dombey seems like damaged goods. He suffers inwardly but doesn't know how to act different. I don't like Dombey, but I give him credit for being a complex character.

I agree, the scene where Dombey tore up the letter was mysterious. I have a feeling the letter is important, but we won't know what it means until later.

I agree, the scene where Dombey tore up the letter was mysterious. I have a feeling the letter is important, but we won't know what it means until later.

I wonder too what the letter contained. My mind creates all kinds of links, also with other books, like Bleak House (view spoiler). The chapter repeats a couple of times that no one will get between Dombey and his son. What if little Paul is not actually Dombey's son? What if he was infertile, and little Florence isn't actually his daughter either? If that turns out to be the case, Chick's mean words about how Florence will never be a Dombey would mean extra foreshadowing; where a boy could be raised as a Dombey to maintain Dombey and Son, and so has some worth even if he technically is not a Dombey, a girl by default is really worthless in that case. Or if she is Dombey's real daughter, it would be an extra stark contrast: the child that is his will never really be part of the family because she is a girl, while the one that I now assume isn't his is doted upon and will inherit the whole shebang.

Tristram wrote: "Now - what kind of letter might this have been? Did Mrs. Dombey have a lover before marrying Dombey? "

Tristram wrote: "Now - what kind of letter might this have been? Did Mrs. Dombey have a lover before marrying Dombey? "My guesses would be

1) An unsent letter to a lover (or almost lover) while married to Dombey.

2) A love letter Dombey wrote to his wife before they were married that shows a side of himself that he would prefer no one else know about -- vulnerability, perhaps.

3) An unsent letter from herself to him informing him of her intention to leave.

My guess is 2 then 1 then 3.

Chapter 5

Chapter 5I had a good laugh at the handshake between Dombey and Mr. Chick, limp fish and all.

I wonder what it was like for Dombey's sister when growing up with Dombey? I'm trying to see what differences there might have been between how they were raised and how Flo and Paul are being raised. The way the Mrs. Chick defers to and fears the brother, I have to believe she was taught from day one her brother was a king and she his chamber maid. One difference, perhaps, between her plight and Flo's, and possibly a determining one, is the presence of Mrs. Richards. (Nothing like a Toodle to add a little light to a dark room.)

Susan Nipper is becoming one of those secondary Dickens characters that you never forget. 'There's a giving orders and there's a taking orders. And the two ain't the same.' (Me paraphrasing).

There may be some hope in Mr. Chick yet.

I think Dickens is shellacking Dombey to the point where he isn't a character anymore but a caricature. He's laying it on too thick, and he's relentless in doing it. Dombey is hard to dislike anymore because he's become unreal.

I like how Mr. Chick keeps being referred to as residing at the BOTTOM of the table.

Tristram wrote: "Paul's christening is a very chilling affair indeed, Kim, and the fact that Mr. Dombey chooses Miss Tox (and the Chicks), probably because their - in the eyes of Mr. Dombey - insignificance shows t..."

But if he is that determined not to have anyone come between him and his son why have godparents at all? Is it something you had to do? Do you have godparents? As to hubris, you have once again managed to use a word I have no clue what it means, and that sentence of yours should really have no breaks in it so it's all one word.

But if he is that determined not to have anyone come between him and his son why have godparents at all? Is it something you had to do? Do you have godparents? As to hubris, you have once again managed to use a word I have no clue what it means, and that sentence of yours should really have no breaks in it so it's all one word.

Tristram wrote: "Did you notice what good things Mrs. Chicks says of her niece? She goes like this, "Florence will never, never, never be a Dombey [...], not if she lives to be a thousand years old."

Let's hope sh..."

Why does Mrs. Chick act this way? She is a woman, why does she think so little of other Dombey girls? I wonder if she was treated the same way when she was a small girl growing up with a Dombey brother, the greatest thing on earth.

Let's hope sh..."

Why does Mrs. Chick act this way? She is a woman, why does she think so little of other Dombey girls? I wonder if she was treated the same way when she was a small girl growing up with a Dombey brother, the greatest thing on earth.

Jantine wrote: "Poor kids, it is all so gloomy.

At least something interesting happened again, it feels like Dickens wants to keep up a fast pace! It was bad for little Florence to be lost, but it turns out even w..."

I wonder how bad it was. Imagine being six or seven years old, I'm not sure how old she is, and being lost having no idea where you are, and then picked up by a horrible old woman. I wonder if she will have nightmares about that for the rest of her life. It wasn't as bad as it could have been though, at least Dickens managed to not cut off her hair, and in a short period of time she was away from "good Mrs. Brown".

At least something interesting happened again, it feels like Dickens wants to keep up a fast pace! It was bad for little Florence to be lost, but it turns out even w..."

I wonder how bad it was. Imagine being six or seven years old, I'm not sure how old she is, and being lost having no idea where you are, and then picked up by a horrible old woman. I wonder if she will have nightmares about that for the rest of her life. It wasn't as bad as it could have been though, at least Dickens managed to not cut off her hair, and in a short period of time she was away from "good Mrs. Brown".

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I Just started chapter 5, but before I go on I just want to say Dumby is so insufferable that I don't know how he doesn't run away from himself. It's getting really ripe anywhere near him.

Right ..."

Right now I have an image of Dombey being married to Miss Haversham for the rest of his life. I don't know which one I feel more sorry for.

Right ..."

Right now I have an image of Dombey being married to Miss Haversham for the rest of his life. I don't know which one I feel more sorry for.

I love these letter ideas, but which one is right? I'm keeping a list:

1. Mrs Dombey has told him that should she not live after giving birth, and the child was female, that it is her wish that he mend his ways and emotions towards their two female children.

2. If the baby is a boy, that Dombey would not neglect or ignore Florence as he presently does and give all his love to their new baby son.

3. Little Paul is not actually Dombey's son.

4. Little Florence isn't actually his daughter either.

5. An unsent letter to a lover (or almost lover) while married to Dombey.

6. A love letter Dombey wrote to his wife before they were married.

7. An unsent letter from herself to him informing him of her intention to leave.

8. A letter from an old lover.

1. Mrs Dombey has told him that should she not live after giving birth, and the child was female, that it is her wish that he mend his ways and emotions towards their two female children.

2. If the baby is a boy, that Dombey would not neglect or ignore Florence as he presently does and give all his love to their new baby son.

3. Little Paul is not actually Dombey's son.

4. Little Florence isn't actually his daughter either.

5. An unsent letter to a lover (or almost lover) while married to Dombey.

6. A love letter Dombey wrote to his wife before they were married.

7. An unsent letter from herself to him informing him of her intention to leave.

8. A letter from an old lover.

It seems that Florence has only had one person to love her at a time her entire life, first her mother, then Mrs. Toodle, hopefully little Paul will soon be old enough to love his sister the way a sister should be loved and not the way I imagine Dombey loved his sister. Right now she's left alone again with her father. Was he even worried about her when she was lost? All he seemed bothered by was that Richards took his son to a bad part of the city. Hopefully he's just not good at showing his feelings.

And I'm glad she got lost because I'm glad she found Uncle Sol and Walter, if they stay in her life she will have people who care about her, finally.

Thinking more about Mrs. Chick, is she older or younger than her brother? Is she the way she is because of how she was treated or did she help make him the man he is today? She seems to have an influence on him at times.

And I'm glad she got lost because I'm glad she found Uncle Sol and Walter, if they stay in her life she will have people who care about her, finally.

Thinking more about Mrs. Chick, is she older or younger than her brother? Is she the way she is because of how she was treated or did she help make him the man he is today? She seems to have an influence on him at times.

As to Mrs. Chick, I think I agree with Kim - even if this might make her feel she was wrong - and say that Mrs. Chick does have an influence on Dombey. She really knows how to press buttons and pull levers with her brother and make him follow her advice. I think this shows Dombey's weakness, his pride and vanity: He is sensitive to flattery and therefore easy to manipulate, at least for certain people.

It remains to be seen whether Miss Tox is not also one of the manipulative flatterers.

It remains to be seen whether Miss Tox is not also one of the manipulative flatterers.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Now - what kind of letter might this have been? Did Mrs. Dombey have a lover before marrying Dombey? "

My guesses would be

1) An unsent letter to a lover (or almost lover) while ..."

I like the second of your assumptions, Xan, because it would show that there is, or used to be, a human side even to Dombey. In a way, it would be a good counterweight to what you called the shellacking of Dombey by Dickens (a nice word, by the way, which I did not know before in such a context). Maybe, in the course of the novel we will find out more about that letter.

I don't really think that Mrs. Dombey would have had a lover while she was married. Would this not run counter to the picture Dickens has drawn of Florence's mother - sketchy as the picture is?

My guesses would be

1) An unsent letter to a lover (or almost lover) while ..."

I like the second of your assumptions, Xan, because it would show that there is, or used to be, a human side even to Dombey. In a way, it would be a good counterweight to what you called the shellacking of Dombey by Dickens (a nice word, by the way, which I did not know before in such a context). Maybe, in the course of the novel we will find out more about that letter.

I don't really think that Mrs. Dombey would have had a lover while she was married. Would this not run counter to the picture Dickens has drawn of Florence's mother - sketchy as the picture is?

Kim wrote: "But if he is that determined not to have anyone come between him and his son why have godparents at all? Is it something you had to do? Do you have godparents?"

I don't really know if you have to have godparents when you are baptized but I have never known anyone who did not have a godfather or a godmother. I had my two grandfathers and one of my uncles as godfathers. But maybe, it's entirely a question of a person's creed: I am a Lutheran, and I don't know whether Calvinists, for instance, need godparents.

I don't really know if you have to have godparents when you are baptized but I have never known anyone who did not have a godfather or a godmother. I had my two grandfathers and one of my uncles as godfathers. But maybe, it's entirely a question of a person's creed: I am a Lutheran, and I don't know whether Calvinists, for instance, need godparents.

I'm a Protestant, which here in the Netherlands nowadays is a combination of a couple of denominations. Lutherans, and the other two - to which the church I feel at home in the most belonged - are two Dutch words to say 'reformed' ... In our family everyone except my youngest cousin is babtised, none of us has godparents, So it's totally depending on both country and denomination as far as I know. We always learned godparents are very much a Roman Catholic thing. So it would be logical that godparents are more usual in Germany, or in England, where they tried to copy the Roman Catholic church sans pope for a long time ;-)

Godparents are also a very good thing as a child because they are usually expected to make you generous birthday gifts and to spend quality time with you. ;-)

Oh, I know, I used to ask my mother 'But why don't we have them????' The standard answers always were euther 'Because we're not Roman Catholic', or 'because baptism is not for presents'. She had a point of course, but me in my childhood thought it was mean, just like my parents not buying a big, expensive present on top of what Sinterklaas gave us. This was around the time I learned dad was dressed like Sinterklaas because the guy didn't exist, so in my childish mind it was all about presents, what do you mean it's not? lol

I always knew Sinterklaas was either dad, or the mayor's wife btw. When 2 years old, I recognized dad immediately, and a week later I asked my gran when she would become Sinterklaas, because Mrs Hulst did. The presents came from the real guy though, until I was about 4, still very young. And still, it was all about the presents

Kim wrote: "I love these letter ideas, but which one is right? I'm keeping a list:

Kim wrote: "I love these letter ideas, but which one is right? I'm keeping a list:1. Mrs Dombey has told him that should she not live after giving birth, and the child was female, that it is her wish that he..."

Mrs. D did have a previous lover. Before she dies, Mr. D is described as "married, as some said, to a lady with no heart to give him; whose happiness was in the past, and who was content to bind her broken spirit to the dutiful and meek endurance of the present." If that's not a lost-love story I don't know what is. I thought it was odd it was just dropped in there like that and left alone (I find the whole beginning of this story strange, and all the more intriguing for it), but now here it is back again.

I don't think she had a lover while married to Dombey. That's Against The Victorian Lady Rules and would doom her two children to irredeemable corruption, but obviously we're supposed to be on their side, so I'm sure she was faultless in her disappointed marriage.

Alissa wrote: "I don't blame Richards for having mixed feelings about the Charitable Grinders. The name itself doesn't sound friendly..."

Alissa wrote: "I don't blame Richards for having mixed feelings about the Charitable Grinders. The name itself doesn't sound friendly..."Lousy education is a real theme for Dickens, isn't it? There's Noah the charity boy in Oliver Twist and I can't remember his name in Nicholas Nickleby and the McChokumchild school in Hard Times. And here we are again.

Kim wrote: "Why does Mrs. Chick act this way? She is a woman, why does she think so little of other Dombey girls?..."

Kim wrote: "Why does Mrs. Chick act this way? She is a woman, why does she think so little of other Dombey girls?..."Mrs. Chick is awful.

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "I love these letter ideas, but which one is right? I'm keeping a list:

1. Mrs Dombey has told him that should she not live after giving birth, and the child was female, that it is her ..."

Julie

In my previous readings of D&S I have always missed the distinct and logical idea that Mrs Dombey had a precious lover. Thank you for highlighting the lines that lead to your conclusion.

I always wonder how much I miss in my readings of Dickens. The answer is obvious. Way too much.

1. Mrs Dombey has told him that should she not live after giving birth, and the child was female, that it is her ..."

Julie

In my previous readings of D&S I have always missed the distinct and logical idea that Mrs Dombey had a precious lover. Thank you for highlighting the lines that lead to your conclusion.

I always wonder how much I miss in my readings of Dickens. The answer is obvious. Way too much.

Julie wrote: "Mrs. D did have a previous lover. Before she dies, Mr. D is described as "married, as some said, to a lady with no heart to give him; whose happiness was in the past, and who was content to bind her broken spirit to the dutiful and meek endurance of the present." If that's not a lost-love story I don't know what is. I thought it was odd it was just dropped in there like that and left alone (I find the whole beginning of this story strange, and all the more intriguing for it), but now here it is back again."

Thank you for pointing this interesting detail out, Julie! But that's also quite bitter for Mr. Dombey, isn't it? Marrying a woman who does not love you but who has resigned herself to her fate so that she just sees her marriage as an exercise in meekness and self-denial. - Or let's say, it could be bitter for Dombey - provided he noticed, which I'm pretty sure he never ever did.

Thank you for pointing this interesting detail out, Julie! But that's also quite bitter for Mr. Dombey, isn't it? Marrying a woman who does not love you but who has resigned herself to her fate so that she just sees her marriage as an exercise in meekness and self-denial. - Or let's say, it could be bitter for Dombey - provided he noticed, which I'm pretty sure he never ever did.

Peter wrote: "I always wonder how much I miss in my readings of Dickens. The answer is obvious. Way too much."

And that's why it is so much fun and so interesting to read the novels again and in a group of observing fellow-readers.

And that's why it is so much fun and so interesting to read the novels again and in a group of observing fellow-readers.

Did you two really never notice that before? I thought the part Julie pointed out made it obvious, that's why I included it in my reasons for the letter list. Good job Julie, obviously there's more wrong with the men here than just grumpiness. :-)

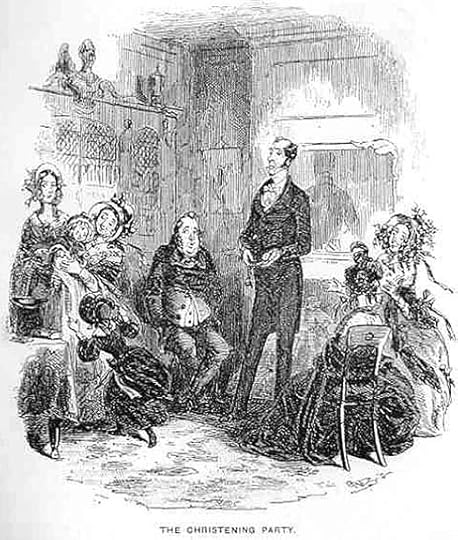

The Christening Party

Chapter 5

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It happened to be an iron-grey autumnal day, with a shrewd east wind blowing—a day in keeping with the proceedings. Mr Dombey represented in himself the wind, the shade, and the autumn of the christening. He stood in his library to receive the company, as hard and cold as the weather; and when he looked out through the glass room, at the trees in the little garden, their brown and yellow leaves came fluttering down, as if he blighted them.

Ugh! They were black, cold rooms; and seemed to be in mourning, like the inmates of the house. The books precisely matched as to size, and drawn up in line, like soldiers, looked in their cold, hard, slippery uniforms, as if they had but one idea among them, and that was a freezer. The bookcase, glazed and locked, repudiated all familiarities. Mr Pitt, in bronze, on the top, with no trace of his celestial origin about him, guarded the unattainable treasure like an enchanted Moor. A dusty urn at each high corner, dug up from an ancient tomb, preached desolation and decay, as from two pulpits; and the chimney-glass, reflecting Mr Dombey and his portrait at one blow, seemed fraught with melancholy meditations.

The stiff and stark fire-irons appeared to claim a nearer relationship than anything else there to Mr Dombey, with his buttoned coat, his white cravat, his heavy gold watch-chain, and his creaking boots. But this was before the arrival of Mr and Mrs Chick, his lawful relatives, who soon presented themselves.

‘My dear Paul,’ Mrs Chick murmured, as she embraced him, ‘the beginning, I hope, of many joyful days!’

‘Thank you, Louisa,’ said Mr Dombey, grimly. ‘How do you do, Mr John?’

‘How do you do, Sir?’ said Chick.

He gave Mr Dombey his hand, as if he feared it might electrify him. Mr Dombey took it as if it were a fish, or seaweed, or some such clammy substance, and immediately returned it to him with exalted politeness.

‘Perhaps, Louisa,’ said Mr Dombey, slightly turning his head in his cravat, as if it were a socket, ‘you would have preferred a fire?’

‘Oh, my dear Paul, no,’ said Mrs Chick, who had much ado to keep her teeth from chattering; ‘not for me.’

‘Mr John,’ said Mr Dombey, ‘you are not sensible of any chill?’

Mr John, who had already got both his hands in his pockets over the wrists, and was on the very threshold of that same canine chorus which had given Mrs Chick so much offence on a former occasion, protested that he was perfectly comfortable.

He added in a low voice, ‘With my tiddle tol toor rul’—when he was providentially stopped by Towlinson, who announced:

‘Miss Tox!’

And enter that fair enslaver, with a blue nose and indescribably frosty face, referable to her being very thinly clad in a maze of fluttering odds and ends, to do honour to the ceremony.

‘How do you do, Miss Tox?’ said Mr Dombey.

Miss Tox, in the midst of her spreading gauzes, went down altogether like an opera-glass shutting-up; she curtseyed so low, in acknowledgment of Mr Dombey’s advancing a step or two to meet her.

‘I can never forget this occasion, Sir,’ said Miss Tox, softly. ‘’Tis impossible. My dear Louisa, I can hardly believe the evidence of my senses.’

If Miss Tox could believe the evidence of one of her senses, it was a very cold day. That was quite clear. She took an early opportunity of promoting the circulation in the tip of her nose by secretly chafing it with her pocket handkerchief, lest, by its very low temperature, it should disagreeably astonish the baby when she came to kiss it.

Mr. Dombey dismounting first to help the ladies out

Chapter 5

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

It was a dull, grey, autumn day indeed, and in a minute’s pause and silence that took place, the leaves fell sorrowfully.

‘Mr John,’ said Mr Dombey, referring to his watch, and assuming his hat and gloves. ‘Take my sister, if you please: my arm today is Miss Tox’s. You had better go first with Master Paul, Richards. Be very careful.’

In Mr Dombey’s carriage, Dombey and Son, Miss Tox, Mrs Chick, Richards, and Florence. In a little carriage following it, Susan Nipper and the owner Mr Chick. Susan looking out of window, without intermission, as a relief from the embarrassment of confronting the large face of that gentleman, and thinking whenever anything rattled that he was putting up in paper an appropriate pecuniary compliment for herself.

Once upon the road to church, Mr Dombey clapped his hands for the amusement of his son. At which instance of parental enthusiasm Miss Tox was enchanted. But exclusive of this incident, the chief difference between the christening party and a party in a mourning coach consisted in the colours of the carriage and horses.

Arrived at the church steps, they were received by a portentous beadle. Mr Dombey dismounting first to help the ladies out, and standing near him at the church door, looked like another beadle. A beadle less gorgeous but more dreadful; the beadle of private life; the beadle of our business and our bosoms.

Miss Tox’s hand trembled as she slipped it through Mr Dombey’s arm, and felt herself escorted up the steps, preceded by a cocked hat and a Babylonian collar. It seemed for a moment like that other solemn institution, ‘Wilt thou have this man, Lucretia?’ ‘Yes, I will.’

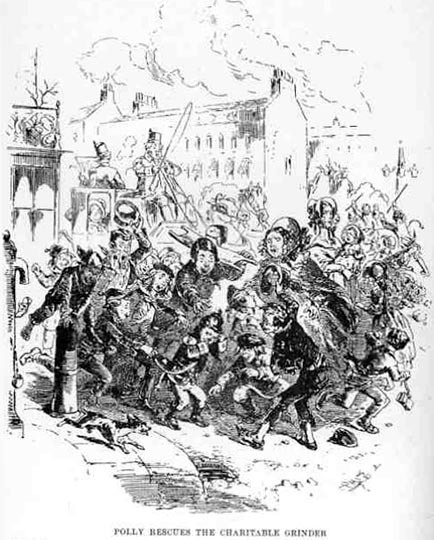

Polly rescues the Charitable Grinder

Chapter 6

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Do you think that we might make time to go a little round in that direction, Susan?’ inquired Polly, when they halted to take breath.

‘Why not, Mrs Richards?’ returned Susan.

‘It’s getting on towards our dinner time you know,’ said Polly.

But lunch had rendered her companion more than indifferent to this grave consideration, so she allowed no weight to it, and they resolved to go ‘a little round.’

Now, it happened that poor Biler’s life had been, since yesterday morning, rendered weary by the costume of the Charitable Grinders. The youth of the streets could not endure it. No young vagabond could be brought to bear its contemplation for a moment, without throwing himself upon the unoffending wearer, and doing him a mischief. His social existence had been more like that of an early Christian, than an innocent child of the nineteenth century. He had been stoned in the streets. He had been overthrown into gutters; bespattered with mud; violently flattened against posts. Entire strangers to his person had lifted his yellow cap off his head, and cast it to the winds. His legs had not only undergone verbal criticisms and revilings, but had been handled and pinched. That very morning, he had received a perfectly unsolicited black eye on his way to the Grinders’ establishment, and had been punished for it by the master: a superannuated old Grinder of savage disposition, who had been appointed schoolmaster because he didn’t know anything, and wasn’t fit for anything, and for whose cruel cane all chubby little boys had a perfect fascination.

Thus it fell out that Biler, on his way home, sought unfrequented paths; and slunk along by narrow passages and back streets, to avoid his tormentors. Being compelled to emerge into the main road, his ill fortune brought him at last where a small party of boys, headed by a ferocious young butcher, were lying in wait for any means of pleasurable excitement that might happen. These, finding a Charitable Grinder in the midst of them—unaccountably delivered over, as it were, into their hands—set up a general yell and rushed upon him.

But it so fell out likewise, that, at the same time, Polly, looking hopelessly along the road before her, after a good hour’s walk, had said it was no use going any further, when suddenly she saw this sight. She no sooner saw it than, uttering a hasty exclamation, and giving Master Dombey to the black-eyed, she started to the rescue of her unhappy little son.

Commentary:

A single theme dominates the early plates, while those in the second offer thematic counterpoint. Paul is naturally the central figure in the early plates, but Browne attempts more than merely to record his development: in Part I the illustrations contrast the Toodles and Dombey families at the same time as they show the relationships which grow up between them. Without its companion, "Miss Tox introduces 'the Party'" (ch. 2) would seem no more than a stilted lineup of the Toodles, Miss Tox, and Mrs. Chick; but as soon as we look at "The Dombey Family" (ch. 3), the importance of the first plate becomes apparent. In both plates Polly stands left of center holding a baby in the same position, and in both the muffled chandelier, a "monstrous tear depending from the ceiling's eye", is present. But the first plate characterizes the Toodles by their physical closeness and contact; in the second plate the Dombeys are epitomized by the spaces between them. Paul is close only to his nurse, who stands at a respectful distance from her employer. Florence is separated from Paul by her father, and from her father by a wide space; she is even outside the door frame.

The thematic contrast of the first two plates is carried farther in the illustrations for Part II, "The Christening Party" (ch. 5) and "Polly rescues the Charitable Grinder" (ch. 6). While the first pair compares the newest Toodle and the newest Dombey, in the second the infant Paul is juxtaposed to Polly's oldest son, Biler, who is about to be saved by his mother from a hostile mob of children. Since both boys are under the aegis of Mr. Dombey (who has arranged for Biler's education and thus for his consequent humiliation), perhaps the point is as much an ironic parallel as a contrast: on the surface the difference between the loved and pampered child of a rich man and a coldly patronized poor man's child is shown, but on another level we see in both the tendency of the Dombey influence to blight and wither.

Florence obeyed as fast as her trembling hands would allow

Chapter 6

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

They had not gone far, but had gone by some very uncomfortable places, such as brick-fields and tile-yards, when the old woman turned down a dirty lane, where the mud lay in deep black ruts in the middle of the road. She stopped before a shabby little house, as closely shut up as a house that was full of cracks and crevices could be. Opening the door with a key she took out of her bonnet, she pushed the child before her into a back room, where there was a great heap of rags of different colours lying on the floor; a heap of bones, and a heap of sifted dust or cinders; but there was no furniture at all, and the walls and ceiling were quite black.

The child became so terrified the she was stricken speechless, and looked as though about to swoon.

‘Now don’t be a young mule,’ said Good Mrs Brown, reviving her with a shake. ‘I’m not a going to hurt you. Sit upon the rags.’

Florence obeyed her, holding out her folded hands, in mute supplication.

‘I’m not a going to keep you, even, above an hour,’ said Mrs Brown. ‘D’ye understand what I say?’

The child answered with great difficulty, ‘Yes.’

‘Then,’ said Good Mrs Brown, taking her own seat on the bones, ‘don’t vex me. If you don’t, I tell you I won’t hurt you. But if you do, I’ll kill you. I could have you killed at any time—even if you was in your own bed at home. Now let’s know who you are, and what you are, and all about it.’

The old woman’s threats and promises; the dread of giving her offence; and the habit, unusual to a child, but almost natural to Florence now, of being quiet, and repressing what she felt, and feared, and hoped; enabled her to do this bidding, and to tell her little history, or what she knew of it. Mrs Brown listened attentively, until she had finished.

‘So your name’s Dombey, eh?’ said Mrs Brown.

‘I want that pretty frock, Miss Dombey,’ said Good Mrs Brown, ‘and that little bonnet, and a petticoat or two, and anything else you can spare. Come! Take ‘em off.’

Florence obeyed, as fast as her trembling hands would allow; keeping, all the while, a frightened eye on Mrs Brown. When she had divested herself of all the articles of apparel mentioned by that lady, Mrs B. examined them at leisure, and seemed tolerably well satisfied with their quality and value.

‘Humph!’ she said, running her eyes over the child’s slight figure, ‘I don’t see anything else—except the shoes. I must have the shoes, Miss Dombey.’

Poor little Florence took them off with equal alacrity, only too glad to have any more means of conciliation about her. The old woman then produced some wretched substitutes from the bottom of the heap of rags, which she turned up for that purpose; together with a girl’s cloak, quite worn out and very old; and the crushed remains of a bonnet that had probably been picked up from some ditch or dunghill. In this dainty raiment, she instructed Florence to dress herself; and as such preparation seemed a prelude to her release, the child complied with increased readiness, if possible.

"Why, what can you want with Dombey and Son's!"

Chapter 6

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

It was full two hours later in the afternoon than when she had started on this strange adventure, when, escaping from the clash and clangour of a narrow street full of carts and waggons, she peeped into a kind of wharf or landing-place upon the river-side, where there were a great many packages, casks, and boxes, strewn about; a large pair of wooden scales; and a little wooden house on wheels, outside of which, looking at the neighbouring masts and boats, a stout man stood whistling, with his pen behind his ear, and his hands in his pockets, as if his day’s work were nearly done.

‘Now then!’ said this man, happening to turn round. ‘We haven’t got anything for you, little girl. Be off!’

‘If you please, is this the City?’ asked the trembling daughter of the Dombeys.

‘Ah! It’s the City. You know that well enough, I daresay. Be off! We haven’t got anything for you.’

‘I don’t want anything, thank you,’ was the timid answer. ‘Except to know the way to Dombey and Son’s.’

The man who had been strolling carelessly towards her, seemed surprised by this reply, and looking attentively in her face, rejoined:

‘Why, what can you want with Dombey and Son’s?’

‘To know the way there, if you please.’

Kim wrote: "

The Christening Party

Chapter 5

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It happened to be an iron-grey autumnal day, with a shrewd east wind blowing—a day in keeping with the proceedings. Mr Dombey represente..."

Kim, as always thanks for the illustrations. I’m sure you enjoyed the fact that this one talks about cold weather.

A very cold day indeed. One thinks of the joy and warmth that should exist when a child is baptized. The coldness in the baptism celebration is more from the lack of human warmth than any climate related reasons.

The Christening Party

Chapter 5

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It happened to be an iron-grey autumnal day, with a shrewd east wind blowing—a day in keeping with the proceedings. Mr Dombey represente..."

Kim, as always thanks for the illustrations. I’m sure you enjoyed the fact that this one talks about cold weather.

A very cold day indeed. One thinks of the joy and warmth that should exist when a child is baptized. The coldness in the baptism celebration is more from the lack of human warmth than any climate related reasons.

Kim wrote: "

Mr. Dombey dismounting first to help the ladies out

Chapter 5

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

It was a dull, grey, autumn day indeed, and in a minute’s pause and silence that took place, the l..."

“The other solemn institution”

Poor Miss Tox. Here imagination is such that she wonders if Mr Dombey will one day lead her to the marriage altar.

Mr. Dombey dismounting first to help the ladies out

Chapter 5

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

It was a dull, grey, autumn day indeed, and in a minute’s pause and silence that took place, the l..."

“The other solemn institution”

Poor Miss Tox. Here imagination is such that she wonders if Mr Dombey will one day lead her to the marriage altar.

Kim wrote: "

Polly rescues the Charitable Grinder

Chapter 6

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Do you think that we might make time to go a little round in that direction, Susan?’ inquired Polly, when they halted to..."

This commentary/analysis of the plates is very insightful and interesting. Clearly Phiz was more than just dashing off a commission. His plates are narratives as well, and a study/reading of them greatly broadens and enhances our appreciation of the novel.

Polly rescues the Charitable Grinder

Chapter 6

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Do you think that we might make time to go a little round in that direction, Susan?’ inquired Polly, when they halted to..."

This commentary/analysis of the plates is very insightful and interesting. Clearly Phiz was more than just dashing off a commission. His plates are narratives as well, and a study/reading of them greatly broadens and enhances our appreciation of the novel.

How do you think the Midshipman situation fits into the theme of railroads in this story. Is Dickens in the state of the shop describing the demise of the shipping industry?