The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

David Copperfield

David Copperfield

>

DC, Chp. 16-18

At the beginning of Chapter 17 Peggotty writes to David and tells him that the furniture at his old house has been sold, the Murdstones have moved, and the house is for sale or let. I wonder where they've disappeared to. David says:

"God knows I had no part in it while they remained there, but it pained me to think of the dear old place as altogether abandoned; of the weeds growing tall in the garden, and the fallen leaves lying thick and wet upon the paths. I imagined how the winds of winter would howl round it, how the cold rain would beat upon the window-glass, how the moon would make ghosts on the walls of the empty rooms, watching their solitude all night. I thought afresh of the grave in the churchyard, underneath the tree: and it seemed as if the house were dead too, now, and all connected with my father and mother were faded away."

It reminds me of our parents home. It is about two blocks from where I now live and when Willow walk by it like we do every day it seems strange that I can't just go down through the yard and in the kitchen door without even knocking. It's been hard to get used to. Anyway, Aunt Betsey visits David every third or fourth Saturday, but Mr. Dick comes to visit every other Wednesday and becomes a favorite of Doctor Strong. Mr. Dick and the doctor spend many hours walking together in the courtyard while the doctor reads his dictionary to Mr. Dick. During one of his visits Mr. Dick tells David that Miss Betsey recently had a strange nighttime encounter with a man who frightened her so badly that she fainted.

'Well, he wasn't there at all,' said Mr. Dick, 'until he came up behind her, and whispered. Then she turned round and fainted, and I stood still and looked at him, and he walked away; but that he should have been hiding ever since (in the ground or somewhere), is the most extraordinary thing!'

'HAS he been hiding ever since?' I asked.

'To be sure he has,' retorted Mr. Dick, nodding his head gravely. 'Never came out, till last night! We were walking last night, and he came up behind her again, and I knew him again.'

'And did he frighten my aunt again?'

'All of a shiver,' said Mr. Dick, counterfeiting that affection and making his teeth chatter. 'Held by the palings. Cried. But, Trotwood, come here,' getting me close to him, that he might whisper very softly; 'why did she give him money, boy, in the moonlight?'

'He was a beggar, perhaps.'

Mr. Dick shook his head, as utterly renouncing the suggestion; and having replied a great many times, and with great confidence, 'No beggar, no beggar, no beggar, sir!' went on to say, that from his window he had afterwards, and late at night, seen my aunt give this person money outside the garden rails in the moonlight, who then slunk away—into the ground again, as he thought probable—and was seen no more: while my aunt came hurriedly and secretly back into the house, and had, even that morning, been quite different from her usual self; which preyed on Mr. Dick's mind."

Neither Mr. Dick nor David understand the encounter but David finally decides that it must have been an attempt, or threat of an attempt, to take poor Mr. Dick from under his aunt's protection, and Aunt Betsey having kind feeling towards him had been persuaded to pay a price for his peace and quiet. I, however do not think this at all, I don't believe someone coming for Mr. Dick would make her faint, she may be frightened but I think she would be more angry then frightened. If I were guessing (which I am) I think it may be that long ago husband of hers who we were told in the first chapter used to beat her and tried to throw her out of a window, she finally paid him off and he went to India where:

"according to a wild legend in our family, he was once seen riding on an elephant, in company with a Baboon; but I think it must have been a Baboo—or a Begum. Anyhow, from India tidings of his death reached home, within ten years."

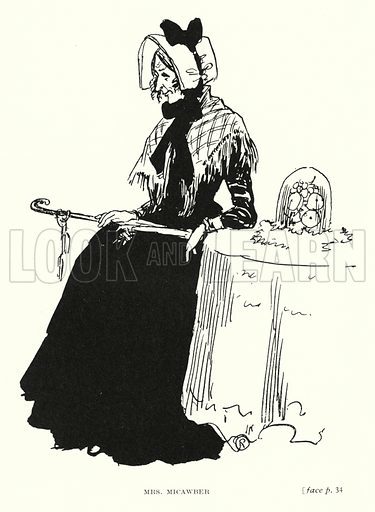

That's my guess as to who it may be, of course many of my guesses are wrong, in a mystery I was reading long ago I never guessed the murderer was a circus bear. Anyway, I think the rumors of his death were wrong, but we will find out sooner or later, at least I hope so. One Thursday morning after David sees Mr. Dick off at the coach he meets Uriah Heep who asks David to have tea with him and his mother, if their "umbleness" doesn't prevent him. Again with that word. David accepts the invitation, and that evening he meets Mrs. Heep, "the dead image of Uriah, only short." I didn't think she looked short in the illustration, but I'm not at the illustrations yet. Mrs. Heep joins her son in umble this and umble that then they proceed to "worm things out" of David about his past life, and then about Mr. Wickfleld and Agnes. David feels uncomfortable and wishes he could leave when Mr. Micawber suddenly appears. He has been walking down the street and through the open door, he spied David. David introduces Micawber to Uriah and his mother, then the two of them leave together and visit Mrs. Micawber, who is very glad to see David. The Micawbers are in terrible financial straits again, Mrs. Micawber explains that at Plymouth her family had been quite cool towards them, especially her husband and his abilities were not wanted there.

The next day, David is surprised to see Mr. Micawber and Uriah Heep "walk past, arm in arm." He learns when he dines with the Micawbers, that Mr. Micawber went home with Uriah and drank brandy and water. Micawber tells David that he is much impressed with Uriah. Although the next day David receives a note from Micawber saying all is over, as David rushes to the hotel worried about what the problem could be he happens to see "the London coach with Mr. and Mrs. Micawber up behind, Mr. Micawber the very picture of tranquil enjoyment.” Well I'm glad about that.

"God knows I had no part in it while they remained there, but it pained me to think of the dear old place as altogether abandoned; of the weeds growing tall in the garden, and the fallen leaves lying thick and wet upon the paths. I imagined how the winds of winter would howl round it, how the cold rain would beat upon the window-glass, how the moon would make ghosts on the walls of the empty rooms, watching their solitude all night. I thought afresh of the grave in the churchyard, underneath the tree: and it seemed as if the house were dead too, now, and all connected with my father and mother were faded away."

It reminds me of our parents home. It is about two blocks from where I now live and when Willow walk by it like we do every day it seems strange that I can't just go down through the yard and in the kitchen door without even knocking. It's been hard to get used to. Anyway, Aunt Betsey visits David every third or fourth Saturday, but Mr. Dick comes to visit every other Wednesday and becomes a favorite of Doctor Strong. Mr. Dick and the doctor spend many hours walking together in the courtyard while the doctor reads his dictionary to Mr. Dick. During one of his visits Mr. Dick tells David that Miss Betsey recently had a strange nighttime encounter with a man who frightened her so badly that she fainted.

'Well, he wasn't there at all,' said Mr. Dick, 'until he came up behind her, and whispered. Then she turned round and fainted, and I stood still and looked at him, and he walked away; but that he should have been hiding ever since (in the ground or somewhere), is the most extraordinary thing!'

'HAS he been hiding ever since?' I asked.

'To be sure he has,' retorted Mr. Dick, nodding his head gravely. 'Never came out, till last night! We were walking last night, and he came up behind her again, and I knew him again.'

'And did he frighten my aunt again?'

'All of a shiver,' said Mr. Dick, counterfeiting that affection and making his teeth chatter. 'Held by the palings. Cried. But, Trotwood, come here,' getting me close to him, that he might whisper very softly; 'why did she give him money, boy, in the moonlight?'

'He was a beggar, perhaps.'

Mr. Dick shook his head, as utterly renouncing the suggestion; and having replied a great many times, and with great confidence, 'No beggar, no beggar, no beggar, sir!' went on to say, that from his window he had afterwards, and late at night, seen my aunt give this person money outside the garden rails in the moonlight, who then slunk away—into the ground again, as he thought probable—and was seen no more: while my aunt came hurriedly and secretly back into the house, and had, even that morning, been quite different from her usual self; which preyed on Mr. Dick's mind."

Neither Mr. Dick nor David understand the encounter but David finally decides that it must have been an attempt, or threat of an attempt, to take poor Mr. Dick from under his aunt's protection, and Aunt Betsey having kind feeling towards him had been persuaded to pay a price for his peace and quiet. I, however do not think this at all, I don't believe someone coming for Mr. Dick would make her faint, she may be frightened but I think she would be more angry then frightened. If I were guessing (which I am) I think it may be that long ago husband of hers who we were told in the first chapter used to beat her and tried to throw her out of a window, she finally paid him off and he went to India where:

"according to a wild legend in our family, he was once seen riding on an elephant, in company with a Baboon; but I think it must have been a Baboo—or a Begum. Anyhow, from India tidings of his death reached home, within ten years."

That's my guess as to who it may be, of course many of my guesses are wrong, in a mystery I was reading long ago I never guessed the murderer was a circus bear. Anyway, I think the rumors of his death were wrong, but we will find out sooner or later, at least I hope so. One Thursday morning after David sees Mr. Dick off at the coach he meets Uriah Heep who asks David to have tea with him and his mother, if their "umbleness" doesn't prevent him. Again with that word. David accepts the invitation, and that evening he meets Mrs. Heep, "the dead image of Uriah, only short." I didn't think she looked short in the illustration, but I'm not at the illustrations yet. Mrs. Heep joins her son in umble this and umble that then they proceed to "worm things out" of David about his past life, and then about Mr. Wickfleld and Agnes. David feels uncomfortable and wishes he could leave when Mr. Micawber suddenly appears. He has been walking down the street and through the open door, he spied David. David introduces Micawber to Uriah and his mother, then the two of them leave together and visit Mrs. Micawber, who is very glad to see David. The Micawbers are in terrible financial straits again, Mrs. Micawber explains that at Plymouth her family had been quite cool towards them, especially her husband and his abilities were not wanted there.

The next day, David is surprised to see Mr. Micawber and Uriah Heep "walk past, arm in arm." He learns when he dines with the Micawbers, that Mr. Micawber went home with Uriah and drank brandy and water. Micawber tells David that he is much impressed with Uriah. Although the next day David receives a note from Micawber saying all is over, as David rushes to the hotel worried about what the problem could be he happens to see "the London coach with Mr. and Mrs. Micawber up behind, Mr. Micawber the very picture of tranquil enjoyment.” Well I'm glad about that.

The last chapter in this installment has the adult David recounting for us his years in Doctor Strong’s school:

"My school-days! The silent gliding on of my existence—the unseen, unfelt progress of my life—from childhood up to youth! Let me think, as I look back upon that flowing water, now a dry channel overgrown with leaves, whether there are any marks along its course, by which I can remember how it ran."

We learn of his love for Miss Shepherd, a boarder at the Misses Nettingalls' establishment. He never talks to her but says she understands him and they live to be united. I love this part:

"Why do I secretly give Miss Shepherd twelve Brazil nuts for a present, I wonder? They are not expressive of affection, they are difficult to pack into a parcel of any regular shape, they are hard to crack, even in room doors, and they are oily when cracked; yet I feel that they are appropriate to Miss Shepherd."

One day she makes a face as him and laughs as he walks by and all is over. Now David is higher in the school and no longer dotes on any of the young ladies at Misses Nettingalls' even, "they were twice as many and twenty times as beautiful." Eventually he fights a butcher who he describes as "a broad-faced, bull-necked, young butcher, with rough red cheeks, an ill-conditioned mind, and an injurious tongue. His main use of this tongue, is, to disparage Doctor Strong's young gentlemen." Unfortunately David loses this first fight. Soon he is the head-boy, as he says:

"I am the head-boy, now! I look down on the line of boys below me, with a condescending interest in such of them as bring to my mind the boy I was myself, when I first came there. That little fellow seems to be no part of me; I remember him as something left behind upon the road of life—as something I have passed, rather than have actually been—and almost think of him as of someone else."

David is now seventeen and once again is in love, this time with Miss Larkins, a woman of thirty. David dreams of winning her and when he dances with her at a ball he is lost "in rapturous reflections." David says much to my amusement:

"I regularly take walks outside Mr. Larkins's house in the evening, though it cuts me to the heart to see the officers go in, or to hear them up in the drawing-room, where the eldest Miss Larkins plays the harp. I even walk, on two or three occasions, in a sickly, spoony manner, round and round the house after the family are gone to bed, wondering which is the eldest Miss Larkins's chamber (and pitching, I dare say now, on Mr. Larkins's instead); wishing that a fire would burst out; that the assembled crowd would stand appalled; that I, dashing through them with a ladder, might rear it against her window, save her in my arms, go back for something she had left behind, and perish in the flames. For I am generally disinterested in my love, and think I could be content to make a figure before Miss Larkins, and expire."

One day Agnes tells him that Miss Larkins is to be married to an elderly hop-grower, Mr. Chestle. David is "terribly dejected for about a week or two". And that's it, it's your turn to talk, the illustrations are calling me.

"My school-days! The silent gliding on of my existence—the unseen, unfelt progress of my life—from childhood up to youth! Let me think, as I look back upon that flowing water, now a dry channel overgrown with leaves, whether there are any marks along its course, by which I can remember how it ran."

We learn of his love for Miss Shepherd, a boarder at the Misses Nettingalls' establishment. He never talks to her but says she understands him and they live to be united. I love this part:

"Why do I secretly give Miss Shepherd twelve Brazil nuts for a present, I wonder? They are not expressive of affection, they are difficult to pack into a parcel of any regular shape, they are hard to crack, even in room doors, and they are oily when cracked; yet I feel that they are appropriate to Miss Shepherd."

One day she makes a face as him and laughs as he walks by and all is over. Now David is higher in the school and no longer dotes on any of the young ladies at Misses Nettingalls' even, "they were twice as many and twenty times as beautiful." Eventually he fights a butcher who he describes as "a broad-faced, bull-necked, young butcher, with rough red cheeks, an ill-conditioned mind, and an injurious tongue. His main use of this tongue, is, to disparage Doctor Strong's young gentlemen." Unfortunately David loses this first fight. Soon he is the head-boy, as he says:

"I am the head-boy, now! I look down on the line of boys below me, with a condescending interest in such of them as bring to my mind the boy I was myself, when I first came there. That little fellow seems to be no part of me; I remember him as something left behind upon the road of life—as something I have passed, rather than have actually been—and almost think of him as of someone else."

David is now seventeen and once again is in love, this time with Miss Larkins, a woman of thirty. David dreams of winning her and when he dances with her at a ball he is lost "in rapturous reflections." David says much to my amusement:

"I regularly take walks outside Mr. Larkins's house in the evening, though it cuts me to the heart to see the officers go in, or to hear them up in the drawing-room, where the eldest Miss Larkins plays the harp. I even walk, on two or three occasions, in a sickly, spoony manner, round and round the house after the family are gone to bed, wondering which is the eldest Miss Larkins's chamber (and pitching, I dare say now, on Mr. Larkins's instead); wishing that a fire would burst out; that the assembled crowd would stand appalled; that I, dashing through them with a ladder, might rear it against her window, save her in my arms, go back for something she had left behind, and perish in the flames. For I am generally disinterested in my love, and think I could be content to make a figure before Miss Larkins, and expire."

One day Agnes tells him that Miss Larkins is to be married to an elderly hop-grower, Mr. Chestle. David is "terribly dejected for about a week or two". And that's it, it's your turn to talk, the illustrations are calling me.

Kim wrote: "This week in Chapter 16 ..."

Kim wrote: "This week in Chapter 16 ..."Oh, that Annie.... she seems to have affection for Dr. Strong, but it's obvious to me (if not to David) that she bestowed upon Jack the cherry-red bow from the bosom of her dress, which seems like it would be considered a rather intimate gift. I hope she's not stringing the doctor along for his money, but what's a girl to think? Whatever HER intentions, I'm still creeped out by the fact that she's the daughter of his friend, and he's known her since she was born. Obviously these relationships weren't unusual back then, but it's hard for me to get past that. No one could blame her for being attracted to a younger man. Hopefully Jack's a distant cousin.

David the adult makes a point of noticing the cherry red item in Jack's hand, and then the missing cherry red bow. David the boy helps to look for the missing frill and doesn't seem to make the connection. David the adult seems to make the connection but doesn't comment on it. A nifty bit of writing by Mr. Dickens, I think.

I don't think it's a spoiler to say that it's common knowledge that Uriah is considered to be one of Dickens' better known villains, but so far, if we take away David's physical descriptions, Uriah seems to be a nice enough guy. Annoying, perhaps, but he's been friendly with David and invited him into his home. For now, I feel a bit sorry for him. He has some odd physical characteristics, but that doesn't make him a bad person. Not yet, anyway.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 17 ..."

Kim wrote: "Chapter 17 ..."First, kudos to David for paying his debts.

The story of Aunt Betsey and the stranger is very reminiscent of Mary Rudge in Barnaby Rudge, so I agree with your hypothesis, Kim, and think the stranger must be her husband. Mean husbands have a way of showing up in Dickens novels, like bad pennies.

Poor David! Haven't we all been stuck in situations with gossips where we find ourselves saying more than intended and regretting it even as the words leave our mouths? There are some people, like Uriah and his mother, who just have a way of getting others to say things they regret. As I read this bit, I couldn't help but think of the Dick Van Dyke Show episode in which Laura went on a game show and the host had her spilling all kinds of confidences about Alan Brady. People like that host and the Heeps can stir up a lot of trouble.

I feel as if I need a tutorial on Charles I, and why he might be in Mr. Dick's head. Seems as if there must be some reason for it, but I don't know British history well and, frankly, can't make a lot of sense of what I've looked up. Seems he married a Catholic, which caused some fuss, and lost the monarchy to the parliamentarians in the English Civil War. He was beheaded and considered by some to be a martyr. (Interesting and gross note: after his decapitation, they sewed his head back on before burying him. How would you like THAT job?). Is any of this meaningful to our story? Am I missing a piece that might be? I don't know.

Kim wrote: "The last chapter in this installment has the adult David recounting for us his years in Doctor Strong’s school..."

Kim wrote: "The last chapter in this installment has the adult David recounting for us his years in Doctor Strong’s school..."A transitional chapter in which David quickly jumps from 10 to 17. David's narrative begins with

Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.

We've already talked about David's vision of a hero being that of a dragon slayer. In this chapter we have him imagining himself saving Miss Larkin from a fire and then perishing in it himself as she grieves for her hero. Later we have him defending himself and his classmates by taking on the Butcher, who we could all tell would easily defeat David in a physical contest.

This business of David playing the hero is obviously going to keep cropping up. I'll be interested to see when (or if, as he wonders in that opening sentence) he becomes a truly heroic, and what that will look like. Or will he end up the victim who needs saving by some other hero?

Kim wrote: "That's my guess as to who it may be, of course many of my guesses are wrong, in a mystery I was reading long ago I never guessed the murderer was a circus bear. "

Kim wrote: "That's my guess as to who it may be, of course many of my guesses are wrong, in a mystery I was reading long ago I never guessed the murderer was a circus bear. "I am very much enjoying these summaries.

Kim wrote: "We learn that Dr. Strong had not been married for a year yet and had married for love, and how Annie had a world of poor relations ready to swarm the Doctor out of house and home, persons like the annoying Jack Maldon. Annie's mother, Mrs. Markleham, certainly makes it clear she sees nothing wrong with all her relatives coming to the doctor for money, but I believe it bothers Annie and I think she married him for love also, or at least has come to love him."

I think the marrying for love part was the Doctor's. I do think Annie loves him but not in the romantic sense. I get the feeling she married more out of respect and duty. Here's her mother relaying Dr. Strong's proposal:

I said, “Now, Annie, tell me the truth this moment; is your heart free?” “Mama,” she said crying, “I am extremely young”—which was perfectly true—“and I hardly know if I have a heart at all.” “Then, my dear,” I said, “you may rely upon it, it’s free. At all events, my love,” said I, “Doctor Strong is in an agitated state of mind, and must be answered. He cannot be kept in his present state of suspense.” “Mama,” said Annie, still crying, “would he be unhappy without me? If he would, I honour and respect him so much, that I think I will have him.” So it was settled.

Notice it's Annie's mother who assumes and says her heart is free, not Annie. And notice Annie's focus is not on her own happiness, but on the doctor's: "would he be unhappy without me?"

Honor and respect is not a bad foundation for love, but I wonder if it will get there or fall short. I feel sorry for Annie, who seems to have good instincts and intentions, and yet her mother doesn't seem to care and her husband doesn't seem to notice what she really thinks.

I don't think her cousin cares about her well-being, either. He's just in it for what he can get.

Mary Lou wrote: "I feel as if I need a tutorial on Charles I, and why he might be in Mr. Dick's head. Seems as if there must be some reason for it"

Mary Lou wrote: "I feel as if I need a tutorial on Charles I, and why he might be in Mr. Dick's head. Seems as if there must be some reason for it"I don't know if this helps, but apparently there was a sort of Charles-cult in Victorian England, under which Charles as the King and the head of the official church was seen as a martyr who falls to religiously dissident Cromwell. Here's a quote from Charlotte Yonge's Heir of Redclyffe (published 3-4 years after Copperfield and if you like an idealistic domestic melodrama--and I do--you could do much worse), in which Guy, the hero of the story, explains why he lost his temper at an insult to King Charles:

‘I did not know you had such personal feelings about King Charles.’

‘If you would do me a kindness,’ proceeded Guy, ‘you would just say you did not mean it. I know you do not, but if you would only say so.’

‘I am glad you have the wit to see I have too much taste to be a roundhead.’ [note: that's a Cromwell dissident]

‘Thank you,’ said Guy; ‘I hope I shall know your jest from your earnest another time. Only if you would oblige me, you would never jest again about King Charles."....

‘I thought King Charles’s wrongs were rankling. I only spoke as taking liberties with a friend.’

‘Yes,’ said Guy, thoughtfully, ‘it may be foolish, but I do not feel as if one could do so with King Charles. He is too near home; he suffered to much from scoffs and railings; his heart was too tender, his repentance too deep for his friends to add one word even in jest to the heap of reproach. How one would have loved him!’ proceeded Guy, wrapped up in his own thoughts,—‘loved him for the gentleness so little accordant with the rude times and the part he had to act—served him with half like a knight’s devotion to his lady-love, half like devotion to a saint, as Montrose did...

Mary Lou wrote: "Kim wrote: "The last chapter in this installment has the adult David recounting for us his years in Doctor Strong’s school..."

A transitional chapter in which David quickly jumps from 10 to 17. Da..."

Mary Lou

I enjoyed your comment on David and the concept of hero. You are right. The novel begins with the question of whether David will be a hero or someone else will fill that space. There certainly is a rich vein of the fairy tale running through the novel-to this point anyway.

How does David define a hero? From this chapter it seems is a person who rescues and restores balance to one’s surroundings. I keep reflecting and wondering why there are so many references to Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. Is a hero one who can build his/her own world regardless of all obstacles?

Perhaps we will eventually find that David is in need of a hero and so the hero of the novel will indeed be someone else.

A transitional chapter in which David quickly jumps from 10 to 17. Da..."

Mary Lou

I enjoyed your comment on David and the concept of hero. You are right. The novel begins with the question of whether David will be a hero or someone else will fill that space. There certainly is a rich vein of the fairy tale running through the novel-to this point anyway.

How does David define a hero? From this chapter it seems is a person who rescues and restores balance to one’s surroundings. I keep reflecting and wondering why there are so many references to Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. Is a hero one who can build his/her own world regardless of all obstacles?

Perhaps we will eventually find that David is in need of a hero and so the hero of the novel will indeed be someone else.

Has anyone been keeping track of the number of girls/women David falls in love with or is attached to in some way? In chapter 17 we can add Miss Shepherd and Miss Larkins. All these female attachments and David has just turned seventeen. And talking about girlfriends or perhaps, more broadly, emotional attachments, we must count his mother and Peggotty. Do we put Miss Murdstone in the mix or his aunt Betsey? Of course there is Dora, and once was Little Em’ly and the ever-present but seemingly only called sister Agnes. There is at least one other I can’t recall at this moment.

Uriah Heep. He is my new favourite character to dislike greatly.

Uriah Heep. He is my new favourite character to dislike greatly.

Peter wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Kim wrote: "The last chapter in this installment has the adult David recounting for us his years in Doctor Strong’s school..."

Peter wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Kim wrote: "The last chapter in this installment has the adult David recounting for us his years in Doctor Strong’s school..."A transitional chapter in which David quickly jumps ..."

Let us not forget Steerforth, oh I forgot he's not a girl !

Of these three chapters I especially enjoyed the last one where we go through 10 years of our hero's life in less than the same number of pages. Call it Dickens' fast-forward technique. It begins with David's infatuation for a girl his own age and his losing in a fist fight to the butcher boy and ends with his heart being broken by an older woman and his gloriously defeating the same butcher boy. This chapter could stand on its own as a short story.

I agree with you all: Uriah Heep is a disturbingly fascinating creep. I can hardly wait to see what vile deeds he has up his clammy sleeve.

Ulysse wrote: "Of these three chapters I especially enjoyed the last one where we go through 10 years of our hero's life in less than the same number of pages. ..."

Ulysse wrote: "Of these three chapters I especially enjoyed the last one where we go through 10 years of our hero's life in less than the same number of pages. ..."That really was well done.

It almost seems like David is desperate to be attached to someone, so he will be attached to anyone who might do, but who is unobtainable. Steerforth because he is male (and being gay was firmly swept under the rug of course, so Dickens would never write that as a viable option). Emily because she was of a totally different class. Agnes was more sister-like. The Shepherd-girl used him for presents, but remained distant. Mrs. Strong was married. Miss Larkins is much older, so of course she'd never chose a school boy over a grown man. His mother ... well, was his mother, and married to Murdstone. One would almost think there was some Freudian jealousy thing about a boy wanting his mother at play here, because it all started with his mother ditching him at Peggotty's place (which it was in a way, however awesome Peggotty is) to marry another man.

Uriah does creep me out. Not because of how Dickens describes his features, but because he seems to be manipulating David with his self-proclaimed umbleness to come and drink tea (because of course it looks bad to be proud, especially after Uriah hinted at that we all know the next thing he'll say if David says know is 'he is too proud for our umble ways, as he should be'). Then they pull a lot of information out of him, and then they either use him to get at Micawber or the other way around, or both.

I even thought for a moment that it could have been Uriah who came to visit Miss Trotwood at night, but surely Mr. Dick would have recognized him, right? When he is in the situation to see Uriah every other week?

Uriah does creep me out. Not because of how Dickens describes his features, but because he seems to be manipulating David with his self-proclaimed umbleness to come and drink tea (because of course it looks bad to be proud, especially after Uriah hinted at that we all know the next thing he'll say if David says know is 'he is too proud for our umble ways, as he should be'). Then they pull a lot of information out of him, and then they either use him to get at Micawber or the other way around, or both.

I even thought for a moment that it could have been Uriah who came to visit Miss Trotwood at night, but surely Mr. Dick would have recognized him, right? When he is in the situation to see Uriah every other week?

Jantine wrote: "...surely Mr. Dick would have recognized him, right?..."

Jantine wrote: "...surely Mr. Dick would have recognized him, right?..."I think this is right. And even if he has somehow not seen Uriah, David makes sure we know that he's physically conspicuous, so I think - if Mr. Dick could see him clearly - he would have described the immediately recognizable writhing and red hair.

Mary Lou wrote: "David the adult makes a point of noticing the cherry red item in Jack's hand, and then the missing cherry red bow. David the boy helps to look for the missing frill and doesn't seem to make the connection. David the adult seems to make the connection but doesn't comment on it. A nifty bit of writing by Mr. Dickens, I think."

Yes, this is another example of how good Dickens is at mixing the two levels of consciousness, i.e. how David saw the world as a child and what experience the elder narrator-David can draw on.

As to Uriah, I'd guess that his invitation of David to his home served an ulterior motive, namely that of sounding David out. Were they not also talking about Mr. Wickfield and his habit of drinking port in the evening? This might be information that could play into Uriah's hands. Apart from that, young Master Heep might feel worried about David's presence in the household - both with regard to the business and his position in it and to Agnes. I think we'd better be wary of Uriah.

Yes, this is another example of how good Dickens is at mixing the two levels of consciousness, i.e. how David saw the world as a child and what experience the elder narrator-David can draw on.

As to Uriah, I'd guess that his invitation of David to his home served an ulterior motive, namely that of sounding David out. Were they not also talking about Mr. Wickfield and his habit of drinking port in the evening? This might be information that could play into Uriah's hands. Apart from that, young Master Heep might feel worried about David's presence in the household - both with regard to the business and his position in it and to Agnes. I think we'd better be wary of Uriah.

Mary Lou wrote: "Poor David! Haven't we all been stuck in situations with gossips where we find ourselves saying more than intended and regretting it even as the words leave our mouths?"

Friedrich Nietzsche once wrote that there are few of us who wouldn't, if short of topics of conversation, eventually blurt out the secrets of their friends.

Friedrich Nietzsche once wrote that there are few of us who wouldn't, if short of topics of conversation, eventually blurt out the secrets of their friends.

Mary Lou wrote: "Kim wrote: "The last chapter in this installment has the adult David recounting for us his years in Doctor Strong’s school..."

A transitional chapter in which David quickly jumps from 10 to 17. Da..."

By the way, Mary Lou, Miss Larkins is another example of a young woman getting married to an elderly man, probably with a view to furhtering her father's business. It seemed to be a common pattern back then. My wife tells me that in Latin America it was usual for the youngest daughter not to marry at all but to remain with her parents and look after them in their old age. Not very inspiring prospects.

A transitional chapter in which David quickly jumps from 10 to 17. Da..."

By the way, Mary Lou, Miss Larkins is another example of a young woman getting married to an elderly man, probably with a view to furhtering her father's business. It seemed to be a common pattern back then. My wife tells me that in Latin America it was usual for the youngest daughter not to marry at all but to remain with her parents and look after them in their old age. Not very inspiring prospects.

Isn't it interesting that David is both glad to see Mr. Micawber again and at the same time impatient to get rid of him because this worthy gentleman is, at the moment, the only link between himself and a past that he considers shameful? David tells us that it took him some time before he felt at ease among the boys at Dr. Strong's school and that at first he always felt like an impostor. What would those boys say if they knew about his working in a factory or about his being a student at Mr. Creakle's school? And now, this shameful past walks into the Heeps' house in the shape of Mr. Micawber, a man who is probably not too cautious and who would easily tell the clever Heep about David's past. While it is definitely not very nice in David to sort of feel ashamed of his association with a kind-hearted man like Mr. Micawber, it is understandable that he is afraid of what Mr. Micawber may tell about his past. It is ambiguities like this that make David a much more interesting protagonist to me than, for example, Florence, who is much more noble and without any dark shades in her character.

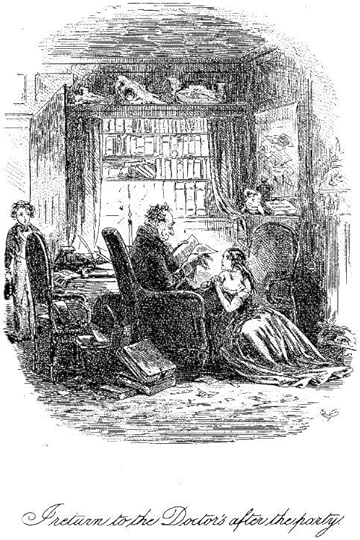

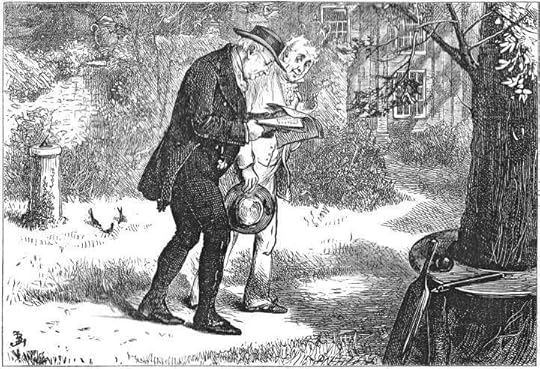

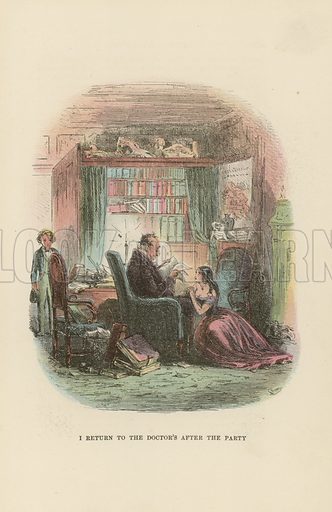

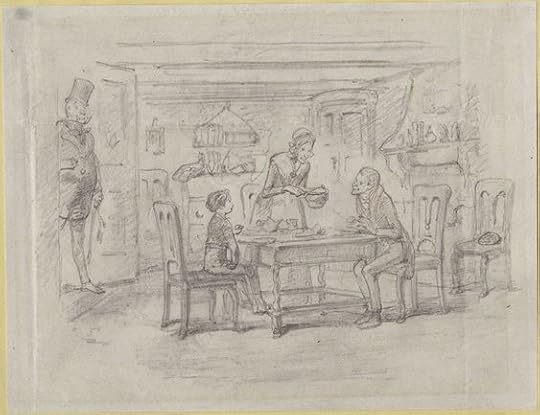

I return to the Doctor's after the party

Chapter 16

Phiz

Commentary:

"I return to the Doctor's after the party," the first illustration for the sixth monthly number, containing chapters 16, 17, and 18, illustrates the following textual passage from chapter 16, according to J. A. Hammerton (1910):

We walked very slowly home, Mr. Wickfield, Agnes, and I—Agnes and I admiring the moonlight, and Mr. Wickfield scarcely raising his eyes from the ground. When we, at last, reached our own door, Agnes discovered that she had left her little reticule behind. Delighted to be of any service to her, I ran back to fetch it.

I went into the supper-room where it had been left, which was deserted and dark. But a door of communication between that and the Doctor’s study, where there was a light, being open, I passed on there, to say what I wanted, and to get a candle.

The Doctor was sitting in his easy-chair by the fireside and his young wife was on a stool at his feet. The Doctor, with a complacent smile, was reading aloud some manuscript explanation or statement of a theory out of that interminable Dictionary, and she was looking up at him. But with such a face as I never saw. It was so beautiful in its form, it was so ashy pale, it was so fixed in its abstraction, it was so full of a wild, sleep-walking, dreamy horror of I don’t know what. The eyes were wide open, and her brown hair fell in two rich clusters on her shoulders, and on her white dress, disordered by the want of the lost ribbon. Distinctly as I recollect her look, I cannot say of what it was expressive, I cannot even say of what it is expressive to me now, rising again before my older judgement. Penitence, humiliation, shame, pride, love, and trustfulness—I see them all; and in them all, I see that horror of I don’t know what.

As in the text, David tentatively enters, unseen for the moment by the Strongs, as the elderly scholar reads aloud from a manuscript, and his young wife looks up at him in rapt attention. Were the viewer unfamiliar with the context, he or she might well conceive of the couple as father and daughter, as David did when he first met them. And, indeed, this unsuitability of the marriage of partners of such different ages is Dickens's salient point in these chapters. Whereas, however, Dickens's Dr. Strong is a benign mentor for the students in his charge, who admire him immensely, Phiz's aged scholar lacks the "complacent smile" that reflects his delight in his lifetime's philological labour, producing "that interminable Dictionary".

The silent observer of the couple in Phiz's illustration is very much a peripheral character here; the focus of the plate is the relationship between the old doctor and his young wife, whose anxious expression in the illustration realizes Dickens's description of her face as "so full of a wild, sleep-walking, dreamy horror of I don't know what". Although Phiz offers no suggestion as to the boy's appraisal of this relationship, as opposed to the narrator's seeing "Penitence,humiliation,shame, pride, love, and trustfulness", the artist provides background details that reflect the character of the study's chief occupant. One receives an overall impression of disorder as pieces of paper litter the floor, the waste-paper basket is full to overflowing, and large tomes balance precariously upon one another behind the doctor's chair. Like the doctor's thinning hair, everywhere in the room is disorder, with books occupying chairs and unrecognizable specimens of natural history occupying the space above the bookshelf. Underneath the map of Europe and Asia is the only readily decipherable piece of writing in the room, "Brick [from] Babylon." Phiz is presumably alluding to what must have seemed the impossible archaeological task of unearthing and reconstructing the ancient cities of Nineveh and Babylon by Sir Austen Henry Layard, whose second expedition to these Assyrian sites was reported in the British press in 1849 through 1851, although Strong is hardly the dashing adventurer that Layard must have seemed in late 1849 when he published Nineveh and Its Remains after his discovery of Sennacherib's Palace at Koujunjik in Mesopotamia.

As in "Changes at home", David is separated from the two central figures of the composition by chairbacks, suggesting the gulf of experience between the child-observer and the adult couple. Phiz intensifies the reader's sense that David lacks sufficient maturity to offer a thorough appraisal of this May/December marriage because he cannot understand the sexuality of the beautiful young wife, to whose charms (emphasized by her bare shoulders) her academically-obsessed, emotionally dessicated husband seems obvious. Thus the chairbacks are a physical representation of David's lack of relevant experience or lack of awareness, which Dickens fails to dramatize since his narrator combines the observational powers of the child with the insights of the adult who is narrating the story of his life. David in this illustration may be, as he describes himself at school in Canterbury, "a new boy in more senses than one," but, in his now-familiar schoolboy's uniform and in his accustomed pose as an observer of the adult world around him, he is David Copperfield, middle-class child, once more, receiving lessons in relationships and in life.

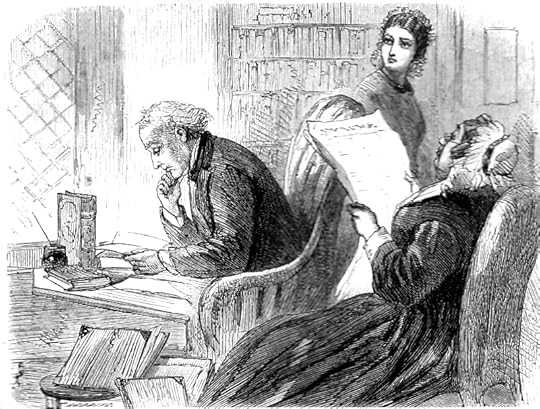

"Dr. and Mrs. Strong and the Old Soldier"

Chapter 16

Sol Eytinge Jr.

1867 Diamond Edition

Commentary:

Realizing well the book's "May/December" marriage partners, the eighth illustration offers yet another atypical model for a middle-class family structure: the elderly scholar, Dr. Strong, his beautiful young wife, Annie, and her interfering mother, whom the boys at Dr. Strong's school in Canterbury have scornfully dubbed "The Old Soldier" by virtue of her self-centred determination to dominate her daughter's household and put her own personal interests ahead of everyone else's. Eytinge has provided a number of contextual details for the setting in which the action occurs — including Dr. Strong, working on his notes for his book (left), the Old Soldier, reading her newspaper (right), and the young wife between the two, a position which exemplifies her divided loyalties and dramatizes her sense of alienation. As in Phiz's depiction of the Strongs in the original serial illustrations, the old scholar has a tumbled pile of books beside him, and seems oblivious to the presence of his wife and mother-in-law. The leaded-pane window (right), large, comfortable chairs, and the book-lined room suggest that the group are in Dr. Strong's library.

Dickens describes Mrs. Markleham and her relationship with her daughter and son-in-law in Chapter 16, "I Am a New Boy in More Senses than One," explaining that her nickname signifies "her generalship and the skill with which she marshalled great forces of relations against the Doctor". Whereas David specifies that Mrs. Markleham is small, Eytinge's seems large, but we see the same "unchangeable [French-style] cap, ornamented with some artificial flowers, and two artificial butterflies." In this earlier chapter, the Old Soldier had attempted to ask a favour of Dr. Strong upon the occasion of cousin Jack Maldon's sailing for India. In Chapter 19, "I Look About Me, and Make a Discovery," the Old Soldier makes explicit her favour, namely that the Doctor intervene so that Jack Maldon, suffering ill-health as a consequence of the climate, be allowed to return to England early, and given "some more suitable and fortunate" (158) position nearer Canterbury. However, since Mrs. Markleham in Eytinge's eighth full-page illustration is reading her newspaper rather than Jack Maldon's letter and since neither the Wickfields nor David is included (and tea is nowhere in sight), this illustration seems to combine elements of several scenes in which the three characters appear. Since Mrs. Markleham is also featured in other chapters, and since — unlike Phiz — Eytinge could select material for his character studies from across the full range of chapters.

Compared to Phiz's version of Annie and her elderly husband in "I Return to the Doctor's After the Party", Eytinge's figures are more realistic; one senses that the illustrator intends us to take them seriously, and regard them as individuals rather than types. Annie Strong's gaze is directed at neither her husband nor her mother, but out of the frame, at the viewers, dispassionately challenging us to understand her awkward position.

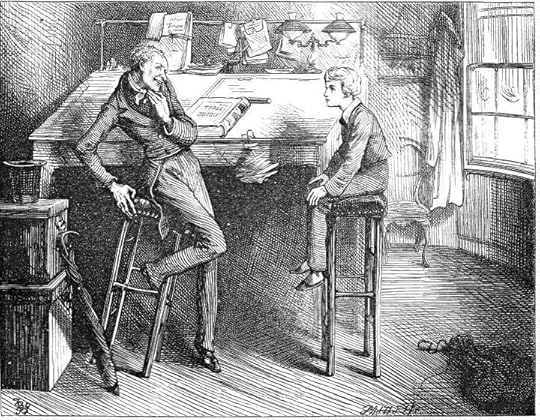

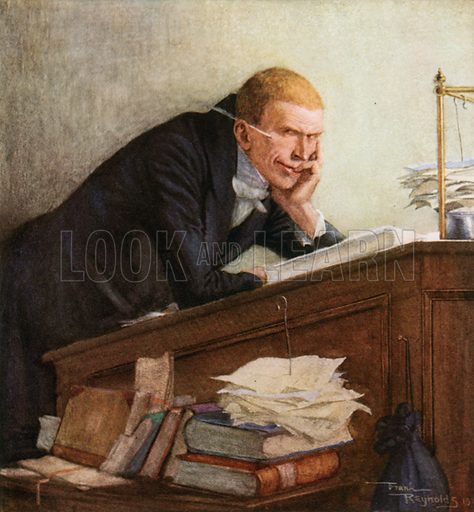

"Oh, thank you, Master Copperfield," said Uriah Heep, "for that remark! It is so true!"

Chapter 16

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘I am well aware that I am the umblest person going,’ said Uriah Heep, modestly; ‘let the other be where he may. My mother is likewise a very umble person. We live in a numble abode, Master Copperfield, but have much to be thankful for. My father’s former calling was umble. He was a sexton.’

‘What is he now?’ I asked.

‘He is a partaker of glory at present, Master Copperfield,’ said Uriah Heep. ‘But we have much to be thankful for. How much have I to be thankful for in living with Mr. Wickfield!’

I asked Uriah if he had been with Mr. Wickfield long?

‘I have been with him, going on four year, Master Copperfield,’ said Uriah; shutting up his book, after carefully marking the place where he had left off. ‘Since a year after my father’s death. How much have I to be thankful for, in that! How much have I to be thankful for, in Mr. Wickfield’s kind intention to give me my articles, which would otherwise not lay within the umble means of mother and self!’

‘Then, when your articled time is over, you’ll be a regular lawyer, I suppose?’ said I.

‘With the blessing of Providence, Master Copperfield,’ returned Uriah.

‘Perhaps you’ll be a partner in Mr. Wickfield’s business, one of these days,’ I said, to make myself agreeable; ‘and it will be Wickfield and Heep, or Heep late Wickfield.’

‘Oh no, Master Copperfield,’ returned Uriah, shaking his head, ‘I am much too umble for that!’

He certainly did look uncommonly like the carved face on the beam outside my window, as he sat, in his humility, eyeing me sideways, with his mouth widened, and the creases in his cheeks.

‘Mr. Wickfield is a most excellent man, Master Copperfield,’ said Uriah. ‘If you have known him long, you know it, I am sure, much better than I can inform you.’

I replied that I was certain he was; but that I had not known him long myself, though he was a friend of my aunt’s.

‘Oh, indeed, Master Copperfield,’ said Uriah. ‘Your aunt is a sweet lady, Master Copperfield!’

He had a way of writhing when he wanted to express enthusiasm, which was very ugly; and which diverted my attention from the compliment he had paid my relation, to the snaky twistings of his throat and body.

‘A sweet lady, Master Copperfield!’ said Uriah Heep. ‘She has a great admiration for Miss Agnes, Master Copperfield, I believe?’

I said, ‘Yes,’ boldly; not that I knew anything about it, Heaven forgive me!

‘I hope you have, too, Master Copperfield,’ said Uriah. ‘But I am sure you must have.’

‘Everybody must have,’ I returned.

‘Oh, thank you, Master Copperfield,’ said Uriah Heep, ‘for that remark! It is so true! Umble as I am, I know it is so true! Oh, thank you, Master Copperfield!’ He writhed himself quite off his stool in the excitement of his feelings, and, being off, began to make arrangements for going home.

‘Mother will be expecting me,’ he said, referring to a pale, inexpressive-faced watch in his pocket, ‘and getting uneasy; for though we are very umble, Master Copperfield, we are much attached to one another. If you would come and see us, any afternoon, and take a cup of tea at our lowly dwelling, mother would be as proud of your company as I should be.’

I said I should be glad to come.

‘Thank you, Master Copperfield,’ returned Uriah, putting his book away upon the shelf—‘I suppose you stop here, some time, Master Copperfield?’

I said I was going to be brought up there, I believed, as long as I remained at school.

‘Oh, indeed!’ exclaimed Uriah. ‘I should think YOU would come into the business at last, Master Copperfield!’

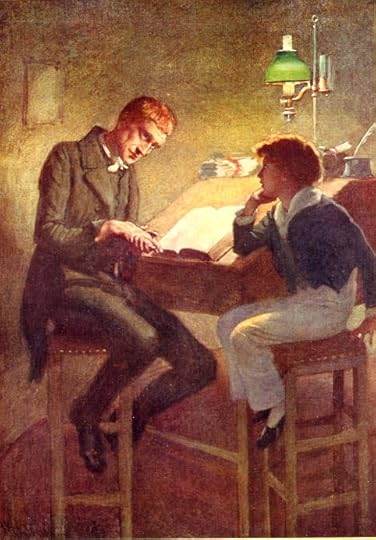

Uriah Heep and David

Chapter 16

Harold Copping

1924

Commentary:

This scene in Mr. Wickfield's counting-house occurs in installment six (chapter 16, "I Am a New Boy in More Senses Than One"), October 1849.

The actual childhood of Charles Dickens and the imagined childhood of his protagonist now part company somewhat as David lodges with the Wickfields while attending Doctor Strong's academy. Having been transported by Aunt Betsy to Canterbury, David meets the diabolical, 'writhing' Uriah Heep, "the umblest person going," who, although the son of a sexton and a mere scrivener, aspires in secret to be a lawyer. The picture seems to combine the boy's initially meeting Heep in chapter 15 with the more extensive interview of the following chapter, since Copping has drawn the background details from the former chapter:

Uriah . . . was at work at a desk in this room, which had a brass frame on the top to hang papers upon, and on which the writing he was making a copy of was then hanging. . . . every now and then, his sleepless eyes would come below the writing, like two red suns, and stealthily stare at me for I dare say a whole minute at a time, during which his pen went, or pretended to go, as cleverly as ever" (ch. 15). As the desk-lamp highlights Uriah's angular head, pale face, and shock of red hair, Copping's chiaroscuro throws the remainder of the room into shadow, so that the map on the wall is not in evidence.

The Doctor's Walk

Chapter 17

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

These Wednesdays were the happiest days of Mr. Dick’s life; they were far from being the least happy of mine. He soon became known to every boy in the school; and though he never took an active part in any game but kite-flying, was as deeply interested in all our sports as anyone among us. How often have I seen him, intent upon a match at marbles or pegtop, looking on with a face of unutterable interest, and hardly breathing at the critical times! How often, at hare and hounds, have I seen him mounted on a little knoll, cheering the whole field on to action, and waving his hat above his grey head, oblivious of King Charles the Martyr’s head, and all belonging to it! How many a summer hour have I known to be but blissful minutes to him in the cricket-field! How many winter days have I seen him, standing blue-nosed, in the snow and east wind, looking at the boys going down the long slide, and clapping his worsted gloves in rapture!

He was an universal favourite, and his ingenuity in little things was transcendent. He could cut oranges into such devices as none of us had an idea of. He could make a boat out of anything, from a skewer upwards. He could turn cramp-bones into chessmen; fashion Roman chariots from old court cards; make spoked wheels out of cotton reels, and bird-cages of old wire. But he was greatest of all, perhaps, in the articles of string and straw; with which we were all persuaded he could do anything that could be done by hands.

Mr. Dick’s renown was not long confined to us. After a few Wednesdays, Doctor Strong himself made some inquiries of me about him, and I told him all my aunt had told me; which interested the Doctor so much that he requested, on the occasion of his next visit, to be presented to him. This ceremony I performed; and the Doctor begging Mr. Dick, whensoever he should not find me at the coach office, to come on there, and rest himself until our morning’s work was over, it soon passed into a custom for Mr. Dick to come on as a matter of course, and, if we were a little late, as often happened on a Wednesday, to walk about the courtyard, waiting for me. Here he made the acquaintance of the Doctor’s beautiful young wife (paler than formerly, all this time; more rarely seen by me or anyone, I think; and not so gay, but not less beautiful), and so became more and more familiar by degrees, until, at last, he would come into the school and wait. He always sat in a particular corner, on a particular stool, which was called ‘Dick’, after him; here he would sit, with his grey head bent forward, attentively listening to whatever might be going on, with a profound veneration for the learning he had never been able to acquire.

This veneration Mr. Dick extended to the Doctor, whom he thought the most subtle and accomplished philosopher of any age. It was long before Mr. Dick ever spoke to him otherwise than bareheaded; and even when he and the Doctor had struck up quite a friendship, and would walk together by the hour, on that side of the courtyard which was known among us as The Doctor’s Walk, Mr. Dick would pull off his hat at intervals to show his respect for wisdom and knowledge. How it ever came about that the Doctor began to read out scraps of the famous Dictionary, in these walks, I never knew; perhaps he felt it all the same, at first, as reading to himself. However, it passed into a custom too; and Mr. Dick, listening with a face shining with pride and pleasure, in his heart of hearts believed the Dictionary to be the most delightful book in the world.

As I think of them going up and down before those schoolroom windows—the Doctor reading with his complacent smile, an occasional flourish of the manuscript, or grave motion of his head; and Mr. Dick listening, enchained by interest, with his poor wits calmly wandering God knows where, upon the wings of hard words—I think of it as one of the pleasantest things, in a quiet way, that I have ever seen. I feel as if they might go walking to and fro for ever, and the world might somehow be the better for it—as if a thousand things it makes a noise about, were not one half so good for it, or me.

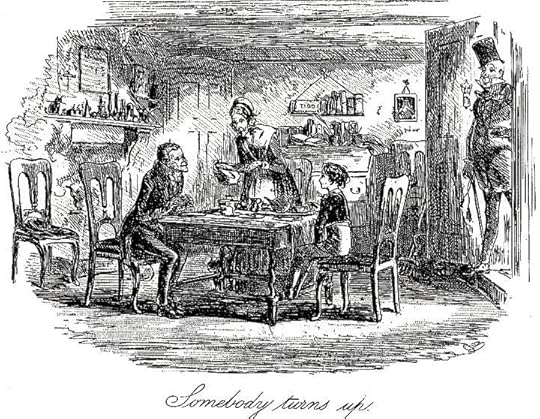

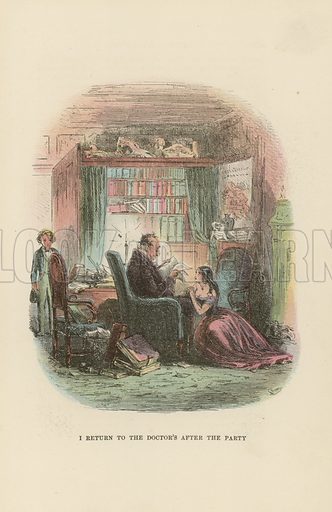

Somebody turns up

Chapter 17

Phiz

Commentary:

For the second illustration in the sixth monthly part, for October 1849, Phiz reintroduces Wilkins Micawber (right, in the doorway) somewhat improbably as David pays a visit to the "umble" cottage of Uriah Heep, Mr. Whitfield's legal clerk, and his mother. One can scarcely credit the coincidence of the Micawbers' abandoning London for a provincial capital in hopes that "something will turn up" and (not to put too fine a point upon it) that they can escape debts amassed in the capital. The illustration serves to introduce the obsequious clerk and his pious mother into the narrative-pictorial sequence. The textual passage realized is this:

I had begun to be a little uncomfortable, and to wish myself well out of the visit, when a figure coming down the street passed the door — it stood open to air the room, which was warm, the weather being close for the time of the year — came back again, looked in, and walked in, exclaiming loudly, "Copperfield! Is it possible?"

It was Mr. Micawber! It was Mr. Micawber, with his eye-glass, and his walking-stick, and his shirt-collar, and his genteel air, and the condescending roll in his voice, all complete!

‘My dear Copperfield,’ said Mr. Micawber, putting out his hand, ‘this is indeed a meeting which is calculated to impress the mind with a sense of the instability and uncertainty of all human—in short, it is a most extraordinary meeting. Walking along the street, reflecting upon the probability of something turning up (of which I am at present rather sanguine), I find a young but valued friend turn up, who is connected with the most eventful period of my life; I may say, with the turning-point of my existence. Copperfield, my dear fellow, how do you do?’

Steig's comment on this scene emphasizes Phiz's utilizing background details to reveal the true natures of Uriah and his mother, even though at this point in the narrative David does not really understand Uriah's hypocrisy, although it certainly makes him "a little uncomfortable":

"Somebody turns up" (ch. 17) finds David in his new, middle-class existence, now a young gentleman, someone to be deferred to by the Heeps, although actually as much a victim as ever. His pride at being "entertained, as an honoured guest" by the fawning Heeps is indicated in the pleasure with which his prissy little face and figure seem to be enjoying Uriah's obsequiousness; it is understandable why he is not glad of Micawber's interruption, but his annoyance is shown in the door knocker's grimace at that gentleman rather than in his own face. Yet the real nature of the event taking place, the corkscrewing of facts about himself out of David — the metaphor is Dickens' own — is indicated by the corkscrew hanging on the wall, the stuffed owl which implies the predatory watchfulness of the Heeps, the mousetrap, and even the ceramic cats, which, together with the real cat next to Mrs. Heep, could represent the Heeps' ability alternately to fawn and purr, and to hiss, spit, and scratch, or destroy a "mouse."

Cohen also notes the mousetrap as symbolic, and the juxtaposition of the legal almanac with it and the two ceramic cats; she does not, however, mention either the many legal documents and books on the sideboard and precarious shelf above it, or the portrait of magistrate in a wig in the right hand corner, all of which imply both Uriah's methods of advancement and his pretensions to power, status, and above all respectability. In the text, David "reads" none of these objects, but in such details "Browne's illustrations often bridge the gap between the the hero's naivete and the world's realities" (Cohen 105).

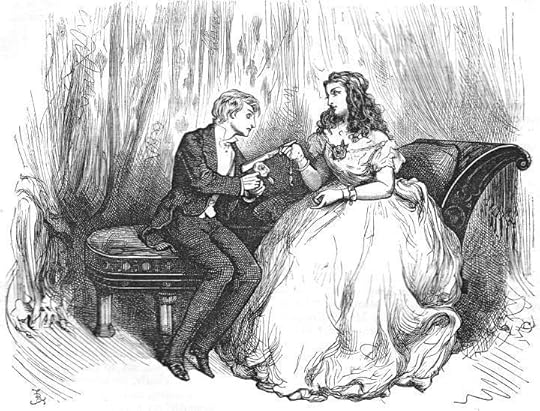

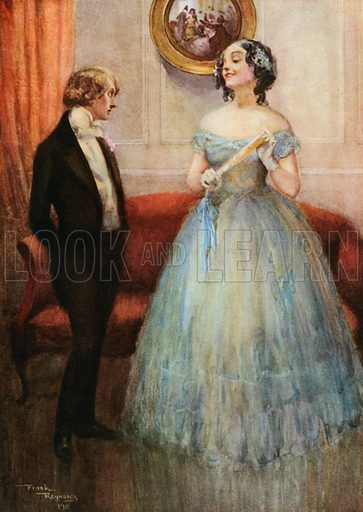

"I ask an instimable price for it, Miss Larkins."

Chapter 18

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

My passion takes away my appetite, and makes me wear my newest silk neckerchief continually. I have no relief but in putting on my best clothes, and having my boots cleaned over and over again. I seem, then, to be worthier of the eldest Miss Larkins. Everything that belongs to her, or is connected with her, is precious to me. Mr. Larkins (a gruff old gentleman with a double chin, and one of his eyes immovable in his head) is fraught with interest to me. When I can’t meet his daughter, I go where I am likely to meet him. To say ‘How do you do, Mr. Larkins? Are the young ladies and all the family quite well?’ seems so pointed, that I blush.

I think continually about my age. Say I am seventeen, and say that seventeen is young for the eldest Miss Larkins, what of that? Besides, I shall be one-and-twenty in no time almost. I regularly take walks outside Mr. Larkins’s house in the evening, though it cuts me to the heart to see the officers go in, or to hear them up in the drawing-room, where the eldest Miss Larkins plays the harp. I even walk, on two or three occasions, in a sickly, spoony manner, round and round the house after the family are gone to bed, wondering which is the eldest Miss Larkins’s chamber (and pitching, I dare say now, on Mr. Larkins’s instead); wishing that a fire would burst out; that the assembled crowd would stand appalled; that I, dashing through them with a ladder, might rear it against her window, save her in my arms, go back for something she had left behind, and perish in the flames. For I am generally disinterested in my love, and think I could be content to make a figure before Miss Larkins, and expire.

Generally, but not always. Sometimes brighter visions rise before me. When I dress (the occupation of two hours), for a great ball given at the Larkins’s (the anticipation of three weeks), I indulge my fancy with pleasing images. I picture myself taking courage to make a declaration to Miss Larkins. I picture Miss Larkins sinking her head upon my shoulder, and saying, ‘Oh, Mr. Copperfield, can I believe my ears!’ I picture Mr. Larkins waiting on me next morning, and saying, ‘My dear Copperfield, my daughter has told me all. Youth is no objection. Here are twenty thousand pounds. Be happy!’ I picture my aunt relenting, and blessing us; and Mr. Dick and Doctor Strong being present at the marriage ceremony. I am a sensible fellow, I believe—I believe, on looking back, I mean—and modest I am sure; but all this goes on notwithstanding. I repair to the enchanted house, where there are lights, chattering, music, flowers, officers (I am sorry to see), and the eldest Miss Larkins, a blaze of beauty. She is dressed in blue, with blue flowers in her hair—forget-me-nots—as if SHE had any need to wear forget-me-nots. It is the first really grown-up party that I have ever been invited to, and I am a little uncomfortable; for I appear not to belong to anybody, and nobody appears to have anything to say to me, except Mr. Larkins, who asks me how my schoolfellows are, which he needn’t do, as I have not come there to be insulted.

But after I have stood in the doorway for some time, and feasted my eyes upon the goddess of my heart, she approaches me—she, the eldest Miss Larkins!—and asks me pleasantly, if I dance?

I stammer, with a bow, ‘With you, Miss Larkins.’

‘With no one else?’ inquires Miss Larkins.

‘I should have no pleasure in dancing with anyone else.’

Miss Larkins laughs and blushes (or I think she blushes), and says, ‘Next time but one, I shall be very glad.’

The time arrives. ‘It is a waltz, I think,’ Miss Larkins doubtfully observes, when I present myself. ‘Do you waltz? If not, Captain Bailey—’

But I do waltz (pretty well, too, as it happens), and I take Miss Larkins out. I take her sternly from the side of Captain Bailey. He is wretched, I have no doubt; but he is nothing to me. I have been wretched, too. I waltz with the eldest Miss Larkins! I don’t know where, among whom, or how long. I only know that I swim about in space, with a blue angel, in a state of blissful delirium, until I find myself alone with her in a little room, resting on a sofa. She admires a flower (pink camellia japonica, price half-a-crown), in my button-hole. I give it her, and say:

‘I ask an inestimable price for it, Miss Larkins.’

‘Indeed! What is that?’ returns Miss Larkins.

‘A flower of yours, that I may treasure it as a miser does gold.’

‘You’re a bold boy,’ says Miss Larkins. ‘There.’

She gives it me, not displeased; and I put it to my lips, and then into my breast. Miss Larkins, laughing, draws her hand through my arm, and says, ‘Now take me back to Captain Bailey.’

Mr. Dick

‘Edward Handley-Read

About the artist:

Handley-Read – father of Charles Handley-Read, the dedicated enthusiast for Victorian art, architecture and design and knowledgeable scholar about the work of William Burges – was an artist with a varied, lively, engaging style and a life to match.

Born in 1870, Handley-Read had first studied at the Kensington School of Art (then, the National Art Training School, at South Kensington), which was distinguished, in the 1880s, by treating male and female students with a greater degree of equality than many other art schools of the day, concentrating, as it did, on studies of the human form, and allowing women to study the nude, as well as the draped, model. Handley-Read moved from here to the Westminster School of Art, which, from 1877 to 1893, was headed by Fred Brown and, by the late 1880s, was regarded as one of the most progressive art schools in London. Brown’s curriculum was, to a considerable extent, influenced by Alphonse Legros, then at the Slade, and by the Académie Julian, in Paris, where Brown himself had studied in the winter of 1883-4, and where he must have encountered the radical developments in France. He required that young artists should first concentrate on life drawing - but not just conventional, static, poses. Rather, they were to capture their sitters on the move, and thus acquire highly sophisticated skills of observation. Then, students were encouraged to sketch en plein air and to explore and express their individual perceptions and styles. There can be no doubt that Handley-Read’s swift, discerning draughtsmanship and his confident manipulation of colour was shaped by this training.

Handley-Read followed Westminster with the Royal Academy Schools, where he won the Creswick Prize for his landscape painting. In 1895 he became a member of the Royal Society of British Artists - that body which had become ‘Royal’ in 1887, in the Queen’s Jubilee, when it was under the presidency of James McNeill Whistler, who wished to transform the Society into an exciting, modern exhibition venue, with high standards and challenging ideas. Whistler’s ambitions stirred up some resentment - and it was not long before he and his admirers resigned, with the quip, ‘the Artists came out and the British remained’. But, even though his tenure had been brief, the R.B.A. had been altered by Whistler’s involvement and, for some years, continued to be regarded as a place for radical art.

Handley-Read quickly embarked on his career as an illustrator, with early commissions including three illustrations to Walter Wood’s 1912, Grant the Grenadier, His Adventures: A Novel. Full of tales of heroism and derring-do, this lavishly illustrated book was obviously aimed at boys and young men who were hoping to play a role in building and defending the British Empire. The frontispiece itself was a colour lithograph by Handley- Read, entitled, ‘ “Keep it up”, said the Chief, “I shall not forget it” ’ – an exhortation to a young man who, with the Union flag flying behind him, keeps on drumming, through the smoke and chaos of battle. This image, and the others produced by Handley-Read – ‘Grant Captures the Eagle’ and ‘Hurled him into the Dreadful Ditch’ – are fascinating, not only as a reflection of the imperial and militaristic ambitions and fears during this period of intense political confrontation, in Europe and beyond, but also as evidence of Handley-Read’s undoubted brilliance at conveying the vigour and energy of men in battle – their awkward movement, their expressive poses.

By the 1920s, Edward Handley-Read’s artistic output was very varied. He painted the green English countryside bathed in its soft light; the beaches and the sea; colourful parades and celebrations in town; elegant women and nudes. He was also called on to paint portraits of military men and local civic celebrities; even these are witness to Handley-Read’s mastery of bold composition, lively colour and ability to convey a strong sense of an individual life. His training – his artistic schooling and the more bitter training offered by war, as well as the warm family existence he seems to have enjoyed after the Great War – equipped him with a penetrating eye and brain, and enabled him to capture a busy scene or a single individual with vivacity and humanity.

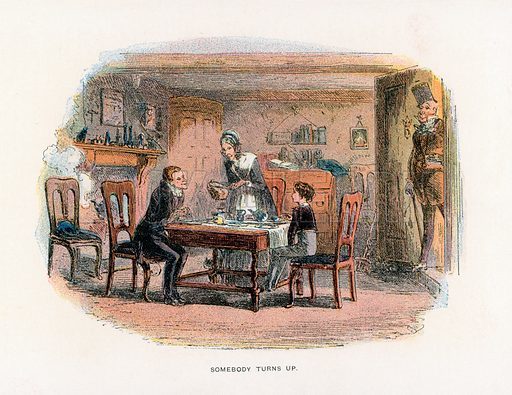

Mr. Micawber

C. L. Doughty

About the artist:

Born in Withernsea, East Riding of Yorkshire, Doughty trained at Battersea Polytechnic, his earliest work comic strip appearing in Knockout and The Children's Newspaper in 1948. Doughty went on to draw Terry Brent for School Friend before finding his metier drawing historical strips for Thriller Comics, his first story adapting William Harrison Ainsworth's novel Windsor Castle followed by many stories featuring Robin Hood and Dick Turpin. In the late 1950s he also drew for Express Weekly and the Eagle, taking over the "Jack O'Lantern" strip in colour for eight months.

In 1962, Doughty began producing illustrations in black & white and colour for Look and Learn. He proved to be one of the paper's most successful historical illustrators, his work appearing over the full twenty-year history of the magazine. When Look and Learn closed in 1982, Doughty retired from commercial artwork to concentrate on landscapes. Already in his late sixties, Doughty held an exhibition of his paintings at Carmarthen, where he was then living.

C. L. Doughty died at the age of 71.

Tristram wrote: "My wife tells me that in Latin America it was usual for the youngest daughter not to marry at all but to remain with her parents and look after them in their old age. Not very inspiring prospects."

When reading that it occurred to me that your wife had done the same thing, married an elderly man, not for your money though, as far as I know. What happened if there was only one daughter anyway? Could she get married then?

When reading that it occurred to me that your wife had done the same thing, married an elderly man, not for your money though, as far as I know. What happened if there was only one daughter anyway? Could she get married then?

Peter wrote: "Has anyone been keeping track of the number of girls/women David falls in love with or is attached to in some way? In chapter 17 we can add Miss Shepherd and Miss Larkins. All these female attachme..."

No, but I have been keeping track, sort of, of all the things David has become separated from as his life goes on. I have lived in the same town all my life. David has lived; with his mother, with Mr. Peggotty, with his mother and her husband, at school, once more at home with the jerk step father, with the Micawbers, with his aunt, with the Wickfields, he better keep his bags packed, it's about time to move on once again.

No, but I have been keeping track, sort of, of all the things David has become separated from as his life goes on. I have lived in the same town all my life. David has lived; with his mother, with Mr. Peggotty, with his mother and her husband, at school, once more at home with the jerk step father, with the Micawbers, with his aunt, with the Wickfields, he better keep his bags packed, it's about time to move on once again.

I'm sitting here thinking of the mystery man being the husband of Aunt Betsey, but as Mary Lou said this already happened in Barnaby Rudge, something like it anyway. So would Dickens do the same thing only a few novels later?

So Annie is missing a cherry red ribbon and her jerk of a cousin has something red in his hand. Did she give it to him or did he take it? And does it matter? I'm not sure yet.

Kim wrote: (from the illustration commentary) "this unsuitability of the marriage of partners of such different ages..."

Kim wrote: (from the illustration commentary) "this unsuitability of the marriage of partners of such different ages..."Oh, that's rich. But maybe it's just in marriage that it's unsuitable and not in affairs?

Kim wrote: "

Kim wrote: "Uriah Heep

Frank Reynolds"

Has anyone here seen "Monarch of the Glen"? This is Golly with red hair. I guess Reynolds never watched the show, though.

Regardless -- this isn't a 15-year-old, and I don't imagine Uriah as looking so very calculating. This guy doesn't look the least bit 'umble.

Kim wrote: "When reading that it occurred to me that your wife had done the same thing, married an elderly man, not for your money though, as far as I know. What happened if there was only one daughter anyway? Could she get married then?"

Married an elderly man? Why, I am in the prime of my life and glorious to behold!

Married an elderly man? Why, I am in the prime of my life and glorious to behold!

Mary Lou wrote: "Kim wrote: "

Uriah Heep

Frank Reynolds"

Has anyone here seen "Monarch of the Glen"? This is Golly with red hair. I guess Reynolds never watched the show, though.

Regardless -- this isn't a 15-..."

Oh, yes! I knew he looked familiar!

Golly is awesome though, and totally unlike Uriah already. I do concur, this picture totally is not one of a 15-going-on-16-year-old, more of a 50-going-on-60-year-old.

Uriah Heep

Frank Reynolds"

Has anyone here seen "Monarch of the Glen"? This is Golly with red hair. I guess Reynolds never watched the show, though.

Regardless -- this isn't a 15-..."

Oh, yes! I knew he looked familiar!

Golly is awesome though, and totally unlike Uriah already. I do concur, this picture totally is not one of a 15-going-on-16-year-old, more of a 50-going-on-60-year-old.

Kim wrote: "

I return to the Doctor's after the party

Chapter 16

Phiz

Commentary:

"I return to the Doctor's after the party," the first illustration for the sixth monthly number, containing chapters 16, 1..."

Kim

An illustration to remind us all that school is beginning again, although in a different way.

Near the end of the commentary for this illustration is mentioned how David is an observer. He certainly is, but the narrative form and style make an interesting frame. David, as an adult, is telling the story of his life. As an adult, David must cast his mind back to when he was much younger and an observer of life. And yet, as the narrator of the novel, David is always an observer whether he is young or old. I find that interesting and quirky.

In terms of writing I am also struck by others who are writers in this novel. We have Doctor Strong who is writing a dictionary and Mr Dick who is writing history. Then of course, we have David writing about himself.

Lots of writing. The dictionary is factual, Mr Dick is, in theory, history and David, well, is it fact or fiction?

I return to the Doctor's after the party

Chapter 16

Phiz

Commentary:

"I return to the Doctor's after the party," the first illustration for the sixth monthly number, containing chapters 16, 1..."

Kim

An illustration to remind us all that school is beginning again, although in a different way.

Near the end of the commentary for this illustration is mentioned how David is an observer. He certainly is, but the narrative form and style make an interesting frame. David, as an adult, is telling the story of his life. As an adult, David must cast his mind back to when he was much younger and an observer of life. And yet, as the narrator of the novel, David is always an observer whether he is young or old. I find that interesting and quirky.

In terms of writing I am also struck by others who are writers in this novel. We have Doctor Strong who is writing a dictionary and Mr Dick who is writing history. Then of course, we have David writing about himself.

Lots of writing. The dictionary is factual, Mr Dick is, in theory, history and David, well, is it fact or fiction?

Kim wrote: "Here's our Phiz illustration colored, enjoy Peter:

"

If I see enough of these I know I will start enjoying them. That will make me less grumpy.

"

If I see enough of these I know I will start enjoying them. That will make me less grumpy.

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "Here's our Phiz illustration colored, enjoy Peter:

"

If I see enough of these I know I will start enjoying them. That will make me less grumpy."

Well, ok then, here you go:

"

If I see enough of these I know I will start enjoying them. That will make me less grumpy."

Well, ok then, here you go:

I was thinking of Uriah Heep and Dickens habit of basing his characters on real people and found this:

Much of David Copperfield is autobiographical, and some scholars believe Heep's mannerisms and physical attributes to be based on Hans Christian Andersen, whom Dickens met shortly before writing the novel. Uriah Heep's schemes and behaviour are more likely based on Thomas Powell, employee of Thomas Chapman, a friend of Dickens. Powell "ingratiated himself into the Dickens household" and was discovered to be a forger and a thief, having embezzled £10,000 from his employer. He later attacked Dickens in pamphlets, calling particular attention to Dickens' social class and background. Powell was employed as a clerk in the shipping business of John Chapman & Co. of 2 Leadenhall Street in London. Charles Dickens was acquainted with the principal partners in the firm and asked them to find a position for his young brother Augustus Dickens. Powell acted as Augustus' mentor, earning the thanks and appreciation of Charles Dickens, who occasionally socialised and corresponded with Powell on friendly and informal terms.