Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit - Group Read 2

>

Little Dorrit: Chapters 12 - 22

This is a list of all the chapters in this thread, beginning with Chapter 12, which is the first chapter in Charles Dickens's original monthly installment 4. Clicking on each chapter will automatically link you to the summary for that chapter:

This is a list of all the chapters in this thread, beginning with Chapter 12, which is the first chapter in Charles Dickens's original monthly installment 4. Clicking on each chapter will automatically link you to the summary for that chapter:LITTLE DORRIT

First Book: Poverty

IV– March 1856 (chapters 12–14)

Chapter 12 (Message 3)

Chapter 13 (Message 17)

Chapter 14 (Message 46)

V – April 1856 (chapters 15–18)

Chapter 15 (Message 74)

Chapter 16 (Message 103)

Chapter 17 (Message 126)

Chapter 18 (Message 145)

VI – May 1856 (chapters 19–22)

Chapter 19 (Message 166)

Chapter 20 (Message 186)

Chapter 21 (Message 215)

Chapter 22 (Message 240)

message 3:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 26, 2020 03:39AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Chapter 12:

The chapter begins with a long description of “Bleeding Heart Yard”, where Arthur, Mr. Meagles and Daniel Doyce have gone. The narrator says that there are two schools of thought about how it got its name. The more practical residents there say it refers to a murder, but the gentler, more romantic ones, (who, the narrator says, there are far more of, and hopes there always will be) say it is because of a doomed love affair in which the woman refused to marry the suitor her father chose for her, staying faithful to her “own true love” and was therefore locked behind bars in her bedchamber, singing a popular song, “Bleeding Heart, Bleeding Heart, bleeding away,” until she died.

Arthur is keen to find the home of Mr. Plornish, but no one seems to know where he lives. He eventually finds it as part of a large house, let off to various tenants, at the end of the courtyard as Amy had said.

Arthur knocks at the parlour door, which is the part of the building occupied by the Plornish family, and it is opened by Mrs. Plornish holding one of her children. She is:

“a young woman, made somewhat slatternly in herself and her belongings by poverty; and so dragged at by poverty and the children together, that their united forces had already dragged her face into wrinkles.”

Mrs. Plornish explains, saying “not to deceive you, sir,” at every opportunity, believing this to be courteous. She says that her husband is out, but is expected back soon. She hopes that Arthur is there about a job, and is disappointed when he replies that this is not the case. Arthur is disappointed not be able to help in this way too, as he would have liked to, and she seems so anxious and polite. Mrs. Plornish tells Arthur candidly that her husband has a hard time remaining employed, and that all the plastering jobs which Mr. Plornish knows about “seems to me to have gone underground”. He always works when he has the chance, she assures Arthur, and no one ever heard her husband complain about work:

Arthur Clennam and Mrs. Plornish - James Mahoney

As his wife is talking, Mr. Plornish himself enters. He is:

“A smooth-cheeked, fresh-coloured, sandy-whiskered man of thirty. Long in the legs, yielding at the knees, foolish in the face, flannel-jacketed, lime-whitened.”

At first Mr. Plornish is suspicious, and thinks that Arthur may be a creditor. However, when Arthur mentions his name, which Mr. Plornish knows, he is immediately all smiles, and asks Arthur to sit down. He says that he and his wife are well acquainted with both Little Dorrit and her father, because “I have been on the wrong side of the Lock myself,”. He relates how Mr. Dorrit used to exaggerate the amount he owed. Also, Mr. Plornish seems to be proud of his acquaintance with the Dorrit family, precisely because of the enormous amount of money they owe to their creditors! Arthur expresses doubt:

“‘Without admiring him for that,’ Clennam quietly observed, ‘I am very sorry for him.’”

and Mr. Plornish then begins to reflect, and wonder if this is not necessarily such a mark of a gentleman after all.

Arthur then asks how they came to introduce Little Dorrit to his mother and Mrs. Plornish tells him. Little Dorrit had written a few copies of an advert, seeking employment at needlework, after the Plornishes’ suggestion. One of these was taken to the landlord of the yard, Mr. Casby. It was through this that Mrs. Clennam first happened to employ Little Dorrit.

This makes Arthur very thoughtful:

“Mr Casby, too! An old acquaintance of mine, long ago!”

He then goes on to state the main purpose of his visit: to effect Tip’s release, through Mr. Plornish, and to make sure that Tip does not know who his benefactor is. The plaintiff is a horse seller and they go to a stable-yard in High Holborn. Mr. Plornish feels that ten shillings in the pound “would settle handsome,” and that any more would be a waste of money. After a bit of bargaining, this is done. Arthur duly asks Plornish:

“‘to tell him that you were employed to compound for the debt by some one whom you are not at liberty to name, you will not only do me a service, but may do him one, and his sister also.’

‘The last reason, sir,’ said Plornish, ‘would be quite sufficient. Your wishes shall be attended to.’“

Arthur asks asks the Plornishes to let him know if they ever think of how he can help the Dorrit family, because they have better knowledge of the family than he does. He wants to be “delicately and really useful to Little Dorrit”, if he can.

The chapter ends as Mr Plornish “in a prolix, gently-growling, foolish way”, delivers a long speech about the difficulty he has of finding work.

The chapter begins with a long description of “Bleeding Heart Yard”, where Arthur, Mr. Meagles and Daniel Doyce have gone. The narrator says that there are two schools of thought about how it got its name. The more practical residents there say it refers to a murder, but the gentler, more romantic ones, (who, the narrator says, there are far more of, and hopes there always will be) say it is because of a doomed love affair in which the woman refused to marry the suitor her father chose for her, staying faithful to her “own true love” and was therefore locked behind bars in her bedchamber, singing a popular song, “Bleeding Heart, Bleeding Heart, bleeding away,” until she died.

Arthur is keen to find the home of Mr. Plornish, but no one seems to know where he lives. He eventually finds it as part of a large house, let off to various tenants, at the end of the courtyard as Amy had said.

Arthur knocks at the parlour door, which is the part of the building occupied by the Plornish family, and it is opened by Mrs. Plornish holding one of her children. She is:

“a young woman, made somewhat slatternly in herself and her belongings by poverty; and so dragged at by poverty and the children together, that their united forces had already dragged her face into wrinkles.”

Mrs. Plornish explains, saying “not to deceive you, sir,” at every opportunity, believing this to be courteous. She says that her husband is out, but is expected back soon. She hopes that Arthur is there about a job, and is disappointed when he replies that this is not the case. Arthur is disappointed not be able to help in this way too, as he would have liked to, and she seems so anxious and polite. Mrs. Plornish tells Arthur candidly that her husband has a hard time remaining employed, and that all the plastering jobs which Mr. Plornish knows about “seems to me to have gone underground”. He always works when he has the chance, she assures Arthur, and no one ever heard her husband complain about work:

Arthur Clennam and Mrs. Plornish - James Mahoney

As his wife is talking, Mr. Plornish himself enters. He is:

“A smooth-cheeked, fresh-coloured, sandy-whiskered man of thirty. Long in the legs, yielding at the knees, foolish in the face, flannel-jacketed, lime-whitened.”

At first Mr. Plornish is suspicious, and thinks that Arthur may be a creditor. However, when Arthur mentions his name, which Mr. Plornish knows, he is immediately all smiles, and asks Arthur to sit down. He says that he and his wife are well acquainted with both Little Dorrit and her father, because “I have been on the wrong side of the Lock myself,”. He relates how Mr. Dorrit used to exaggerate the amount he owed. Also, Mr. Plornish seems to be proud of his acquaintance with the Dorrit family, precisely because of the enormous amount of money they owe to their creditors! Arthur expresses doubt:

“‘Without admiring him for that,’ Clennam quietly observed, ‘I am very sorry for him.’”

and Mr. Plornish then begins to reflect, and wonder if this is not necessarily such a mark of a gentleman after all.

Arthur then asks how they came to introduce Little Dorrit to his mother and Mrs. Plornish tells him. Little Dorrit had written a few copies of an advert, seeking employment at needlework, after the Plornishes’ suggestion. One of these was taken to the landlord of the yard, Mr. Casby. It was through this that Mrs. Clennam first happened to employ Little Dorrit.

This makes Arthur very thoughtful:

“Mr Casby, too! An old acquaintance of mine, long ago!”

He then goes on to state the main purpose of his visit: to effect Tip’s release, through Mr. Plornish, and to make sure that Tip does not know who his benefactor is. The plaintiff is a horse seller and they go to a stable-yard in High Holborn. Mr. Plornish feels that ten shillings in the pound “would settle handsome,” and that any more would be a waste of money. After a bit of bargaining, this is done. Arthur duly asks Plornish:

“‘to tell him that you were employed to compound for the debt by some one whom you are not at liberty to name, you will not only do me a service, but may do him one, and his sister also.’

‘The last reason, sir,’ said Plornish, ‘would be quite sufficient. Your wishes shall be attended to.’“

Arthur asks asks the Plornishes to let him know if they ever think of how he can help the Dorrit family, because they have better knowledge of the family than he does. He wants to be “delicately and really useful to Little Dorrit”, if he can.

The chapter ends as Mr Plornish “in a prolix, gently-growling, foolish way”, delivers a long speech about the difficulty he has of finding work.

message 4:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 26, 2020 03:41AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

A Little More:

About Bleeding Heart Yard

“Bleeding Heart Yard” is a cobbled courtyard off Greville Street, in the Farringdon area of the City of London. It is probably named after a 16th-century inn sign, dating back to the Reformation, as there was a pub called “The Bleeding Heart” in Charles Street, which is nearby. The sign showed the heart of the Virgin Mary pierced by five swords.

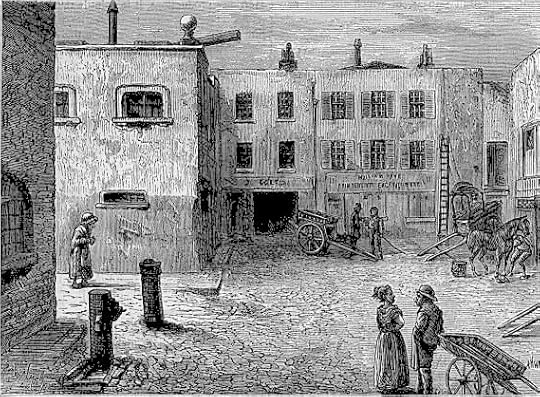

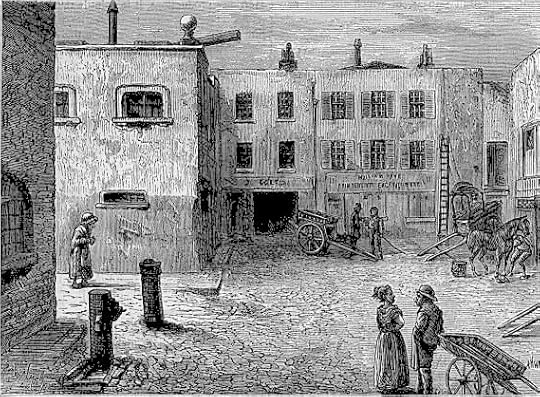

Bleeding Heart yard - Walter Thornbury - Old and New London 1873-8

There is a legend which says that the courtyard’s name commemorates the murder of Lady Elizabeth Hatton, the second wife of Sir. William Hatton, whose family formerly owned the area around the Hatton Garden (an area now famous for high-end jewellers). It is said that her body was found here on 27 January 1626, “torn limb from limb, but with her heart still pumping blood”.

About Bleeding Heart Yard

“Bleeding Heart Yard” is a cobbled courtyard off Greville Street, in the Farringdon area of the City of London. It is probably named after a 16th-century inn sign, dating back to the Reformation, as there was a pub called “The Bleeding Heart” in Charles Street, which is nearby. The sign showed the heart of the Virgin Mary pierced by five swords.

Bleeding Heart yard - Walter Thornbury - Old and New London 1873-8

There is a legend which says that the courtyard’s name commemorates the murder of Lady Elizabeth Hatton, the second wife of Sir. William Hatton, whose family formerly owned the area around the Hatton Garden (an area now famous for high-end jewellers). It is said that her body was found here on 27 January 1626, “torn limb from limb, but with her heart still pumping blood”.

message 5:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 24, 2020 03:36PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

More on this?

Well, before Charles Dickens’s novel, Little Dorrit, the courtyard was best known for its appearance in R.H. Barham’s book of “The Ingoldsby Legends”, a collection of poems and stories first published in “Bentley’s Miscellany” beginning in 1837. We now remember “Bentley’s Miscellany”, chiefly because Charles Dickens was its first editor, a year earlier in 1836. In fact “Oliver Twist”, his second novel, began as a serial in “Bentley’s Miscellany”. But Charles Dickens did not remain long as the editor, as he quarrelled with Bentley in 1839 over editorial control, calling him a “Burlington Street Brigand”!

But back to “The Ingoldsby Legends”, and in one of the stories, called “ The House-Warming: A Legend Of Bleeding-Heart Yard”, Lady Hatton, the wife of Sir. Christopher Hatton, makes a pact with the devil to secure wealth, position, and a mansion in Holborn. During the housewarming of the mansion, the devil dances with her, and then tears out her heart, which is found, still beating, in the courtyard the next morning:

“Of poor Lady Hatton, it’s needless to say,

No traces have ever been found to this day,

Or the terrible dancer who whisk’d her away;

But out in the court-yard — and just in that part

Where the pump stands — lay bleeding a LARGE HUMAN HEART!“

—The Ingoldsby Legends.

Bleeding Heart Yard now

Well, before Charles Dickens’s novel, Little Dorrit, the courtyard was best known for its appearance in R.H. Barham’s book of “The Ingoldsby Legends”, a collection of poems and stories first published in “Bentley’s Miscellany” beginning in 1837. We now remember “Bentley’s Miscellany”, chiefly because Charles Dickens was its first editor, a year earlier in 1836. In fact “Oliver Twist”, his second novel, began as a serial in “Bentley’s Miscellany”. But Charles Dickens did not remain long as the editor, as he quarrelled with Bentley in 1839 over editorial control, calling him a “Burlington Street Brigand”!

But back to “The Ingoldsby Legends”, and in one of the stories, called “ The House-Warming: A Legend Of Bleeding-Heart Yard”, Lady Hatton, the wife of Sir. Christopher Hatton, makes a pact with the devil to secure wealth, position, and a mansion in Holborn. During the housewarming of the mansion, the devil dances with her, and then tears out her heart, which is found, still beating, in the courtyard the next morning:

“Of poor Lady Hatton, it’s needless to say,

No traces have ever been found to this day,

Or the terrible dancer who whisk’d her away;

But out in the court-yard — and just in that part

Where the pump stands — lay bleeding a LARGE HUMAN HEART!“

—The Ingoldsby Legends.

Bleeding Heart Yard now

Jean, you found some fascinating history and legends about the origin of the name of Bleeding Heart Yard. Thanks for all your research.

Jean, you found some fascinating history and legends about the origin of the name of Bleeding Heart Yard. Thanks for all your research.

Jean, thanks for the Bleeding Heart Yard information and pictures!

Jean, thanks for the Bleeding Heart Yard information and pictures!Cannot say I cared much for this chapter, but I would like to more about Mr Casby.

message 8:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 26, 2020 11:56AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

When you investigate the stories behind some of these names, it can be quite startling!

And yes, we will meet Mr. Casby again. There's a treat in store, and hardly any time to wait at all :)

And yes, we will meet Mr. Casby again. There's a treat in store, and hardly any time to wait at all :)

Fascinating info on Bleeding Heart Yard, Jean.

Fascinating info on Bleeding Heart Yard, Jean.By the way, can anyone tell me the meaning of Wan in the following quote? Is it a type of carriage? Does Plornish mean “van”?

“For instance, if they see a man with his wife and children going to Hampton Court in a Wan, perhaps once in a year, they says, ‘Hallo! I thought you was poor, my improvident friend!”

message 11:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 26, 2020 11:14AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Yes, that's right. The character I most associate with using "W" instead of "V" is Sam Weller, in The Pickwick Papers, but Charles Dickens often uses it for East Londoners (cockneys) especially working folk.

This used to surprise me, as for years I worked in East London and knew it to be incorrect! Yet Charles Dickens knew London like the back of his hand, and all classes there too. I finally found the answer from reading something about London's history.

In the mid-late 19th century there was a local "fashion" for using a "W" instead of a "V", when spoken. A bit like dropping off the "G" at the end of any word ending in "ing" for upper classes in around the 1920s. It lasted for about 20 years, and this is why Charles Dickens uses it for some of his London characters :)

This used to surprise me, as for years I worked in East London and knew it to be incorrect! Yet Charles Dickens knew London like the back of his hand, and all classes there too. I finally found the answer from reading something about London's history.

In the mid-late 19th century there was a local "fashion" for using a "W" instead of a "V", when spoken. A bit like dropping off the "G" at the end of any word ending in "ing" for upper classes in around the 1920s. It lasted for about 20 years, and this is why Charles Dickens uses it for some of his London characters :)

Hi, Jean and Katy..Thanks for the info. I thought “wan” might man “van”. But I wasn’t sure. I wonder if a van in those days was a large wagon or carriage.

Hi, Jean and Katy..Thanks for the info. I thought “wan” might man “van”. But I wasn’t sure. I wonder if a van in those days was a large wagon or carriage.

Thanks for the info, Jean. The area still looks a little downtrodden.

Thanks for the info, Jean. The area still looks a little downtrodden.I wonder if Arthur just gave money for nothing, I don't think Tip will keep away from the Marshalsea too long and I'm pretty sure he wont be grateful (He's never been with his sister).

France-Andrée wrote: " (He's never been with his sister)...."

France-Andrée wrote: " (He's never been with his sister)...."I agree with all you say, France-Andree. Tip will not appreciate this effort made on his behalf.

As for Amy, it seems that no one is grateful for what she does for them. They all seem to think that it's her due or her lot to take care of them. Her hard work is their leisurely lifestyle. Tip isn't alone in this attitude, I find.

I enjoyed this chapter. It showed how difficult it is for hard working people, who are trying their best to just survive, have it.

I enjoyed this chapter. It showed how difficult it is for hard working people, who are trying their best to just survive, have it. The Plornishes are trying so hard to find a job and make ends meet just enough to keep their home and debtors at bay. They aren't even looking to save or gain in any way.

With so many others in the same boat, it becomes a matter of too many people and too few jobs to go around. It's all a matter of luck as to who gets the jobs.

Jean, the history of Bleeding Heart Court is really interesting. Thank you! I like the picture of how it looks today, too. I enjoy it when places in classical books still exist in today's world. Such continuity of Life.

message 16:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 27, 2020 03:43AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

"I enjoyed this chapter. It showed how difficult it is for hard working people, who are trying their best to just survive, have it."

It's a quietish sort of chapter, isn't it Petra. It provides a sort of relief between the scathing criticisms, and those where a lot happens. And you're absolutely right, it is nice to have this sensitive picture of ordinary folk.

But now, hold on to your hats, as today's chapter is wonderfully different :)

It's a quietish sort of chapter, isn't it Petra. It provides a sort of relief between the scathing criticisms, and those where a lot happens. And you're absolutely right, it is nice to have this sensitive picture of ordinary folk.

But now, hold on to your hats, as today's chapter is wonderfully different :)

message 17:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 27, 2020 03:59AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Chapter 13:

This is a very long chapter, in which we meet no less than FIVE new characters, plus a surprising return!

Arthur is beginning to think that there is no easy way to help the Dorrit family. However, he still has Affery’s words in his mind, about his old sweetheart Flora; how she had remarried, but had been widowed shortly afterwards. He decides to go Mr. Casby as his daughter Flora now lives with him again. Arthur convinces himself that this may even help Little Dorrit:

“that it might—for anything he knew—it might be serviceable to the poor child, if he renewed this acquaintance”

However, the narrator reminds us how easily we can persuade ourselves to do something we wish to do, but give other reasons for it.

As soon as Arthur arrives at the house, it seems as gloomy as his mother’s house, but the memories come flooding back about the interior, which is so different:

“The furniture was formal, grave, and quaker-like, but well-kept … There was a grave clock, ticking somewhere up the staircase; and there was a songless bird in the same direction, pecking at his cage, as if he were ticking too.”

And before he even smells it, Arthur remembers the smell of its jars of old rose-leaves and lavender. Arthur is shown in almost soundlessly, and sees Mr. Casby sitting by the fire, Although twenty years or more have passed, Mr. Casby seems unchanged in appearance:

“There was the same smooth face and forehead, the same calm blue eye, the same placid air. The shining bald head, which looked so very large because it shone so much; and the long grey hair at its sides and back, like floss silk or spun glass, which looked so very benevolent because it was never cut; were not, of course, to be seen in the boy as in the old man. Nevertheless, in the Seraphic creature with the haymaking rake, were clearly to be discerned the rudiments of the Patriarch with the list shoes.”

Arthur visits Christopher Casby - James Mahoney

Purely because of his appearance and his demeanour, he is known to many people as “the Patriarch”.

“His smooth face had a bloom upon it like ripe wall-fruit. What with his blooming face, and that head, and his blue eyes, he seemed to be delivering sentiments of rare wisdom and virtue. In like manner, his physiognomical expression seemed to teem with benignity. Nobody could have said where the wisdom was, or where the virtue was, or where the benignity was; but they all seemed to be somewhere about him.”

The two begin an inconsequential conversation, and when Mr. Casby asks Arthur how he has been since last they met:

“Arthur did not think it worth while to explain that in the course of some quarter of a century he had experienced occasional slight fluctuations in his health and spirits.”

By his hesitant replies, it is evident that even after all this time, Arthur still feels nervous in Mr. Casby's presence.

When the conversation allows, Arthur mentions Little Dorrit, but nothing comes of it. Mr. Casby then tells him about Flora, and goes to fetch her. In the meantime, a quick and eager short dark man bustles into the room:

“He was dressed in black and rusty iron grey; had jet black beads of eyes; a scrubby little black chin; wiry black hair striking out from his head in prongs, like forks or hair-pins; and a complexion that was very dingy by nature, or very dirty by art, or a compound of nature and art. He had dirty hands and dirty broken nails, and looked as if he had been in the coals; he was in a perspiration, and snorted and sniffed and puffed and blew, like a little labouring steam-engine.”

This is Pancks: “And so, with a snort and a puff, he worked out by another door.”

Arthur muses on Mr. Casby’s appearance. Mr Casby used to be town-agent to Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle. However, Arthur suspects that this might not be because he had a good head for business. It seems more likely to him, that Mr. Casby looked so kind, that nobody would expect him to squeeze or screw an unfair amount for the property. Now Mr. Casby has many tenants of his own, the same probably applies, He is:

“rich in weekly tenants, and to get a good quantity of blood out of the stones of several unpromising courts and alleys.”

Considering the relationship between Mr. Casby and Pancks, Arthur surmises that Pancks is like a coaly little steam-tug, and the slow, benignant Mr. Casby is like an unwieldy ship in the river Thames:

“similarly the cumbrous Patriarch had been taken in tow by the snorting Pancks, and was now following in the wake of that dingy little craft.”

Mr. Casby returns with Flora, but Arthur is in for a shock:

“Clennam’s eyes no sooner fell upon the subject of his old passion than it shivered and broke to pieces.”

All those years away from home, Flora had stayed in his mind as she once was, and her ideal image had become fixed in his mind. But the Flora of his memory, is no more:

“Flora, always tall, had grown to be very broad too, and short of breath; but that was not much. Flora, whom he had left a lily, had become a peony; but that was not much. Flora, who had seemed enchanting in all she said and thought, was diffuse and silly. That was much. Flora, who had been spoiled and artless long ago, was determined to be spoiled and artless now. That was a fatal blow.

He is aghast to observe that Flora still acts and talks in a girlish, flirtatious manner with him, behaving as if they are in a secret liaison. Arthur wonders if it was possible that Flora was always such a chatterer. Why was he ever so captivated by her? She seems to runs on with astonishing speed, leaving very little room for breath, talking ridiculous nonsense, which makes Arthur’s head whirl. Flora giggles and titters, and tosses her head in a caricature of her girlish manner, and Arthur remains gallant.

Yet for all this, Flora is astute enough to realise that Arthur find her much changed, and clearly did once have a great affection for him:

“when your Mama came and made a scene of it with my Papa and when I was called down into the little breakfast-room where they were looking at one another with your Mama’s parasol between them seated on two chairs like mad bulls what was I to do? … for five days I had a cold in the head from crying”

and she says, almost as an excuse, how she had married Mr. Finching after he had proposed to her seven times.

Despite feeling appalled, Arthur feels sorry for Flora, and agrees to stay for dinner.

Pancks observes:

“’Bleeding Heart Yard?’ said Pancks, with a puff and a snort. ‘It’s a troublesome property. Don’t pay you badly, but rents are very hard to get there. You have more trouble with that one place than with all the places belonging to you … You can’t say, you know,’ snorted Pancks, taking one of his dirty hands out of his rusty iron-grey pockets to bite his nails, if he could find any, and turning his beads of eyes upon his employer, ‘whether they’re poor or not. They say they are, but they all say that. When a man says he’s rich, you’re generally sure he isn’t. Besides, if they are poor, you can’t help it. You’d be poor yourself if you didn’t get your rents.’”

To add to Arthur’s general confusion and light-headedness, another person appears for dinner:

“This was an amazing little old woman, with a face like a staring wooden doll too cheap for expression, and a stiff yellow wig perched unevenly on the top of her head, as if the child who owned the doll had driven a tack through it anywhere, so that it only got fastened on.”

This is Mr. F.’s aunt. She behaves rather aggressively, and her remarks are so absurd and disconnected from the rest of the conversation, that Arthur hardly knows what to say. The narrator remarks that her words may be “ingenious, or even subtle: but the key to it was wanted.” Pancks gets around the problem by agreeing with her, whatever she says. When Mr F.’s aunt says, apparently directed at Arthur (although she never meets anyone’s eyes) “I hate a fool!”, Flora decides that discretion is needed, and escorts her out of the room:

Mr. F's aunt is conducted into retirement - Phiz

When dinner is over Arthur walks home with Pancks, who tells him about his business, and says that that is what his life is about. Work is what he is made for. When Arthur asks him if he has an inclination for anything else, Pancks replies that he has an inclination to get money, and then find this very funny. Does he read? No. And they go their separate ways.

Nearing Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Arthur comes across a crowd of people. They are gathered around a litter which is being carried on men’s shoulders, through the streets. There has been an accident and they are on their way to the hospital. The man was run down by the mailcoach, which people agree goes far too fast, at twelve or fourteen miles a hour.

No one seems to understand what the injured man is saying, but when Arthur gets close to him, he realises that he is asking for water in both Italian and French. Arthur gets him some water and stays with him until he gets to the hospital. The man is:

“A little, muscular, brown man, with black hair and white teeth. A lively face, apparently. Earrings in his ears” and he has just come to the city that evening, from Marseilles.

Arthur says he will stay with him until he is in Saint Bartholomew hospital (Bart’s):

“‘Ah! Altro, Altro!’ cried the poor little man, in a faintly incredulous tone; and as they took him up, hung out his right hand to give the forefinger a back-handed shake in the air.”

He is carefully examined by a surgeon, who relies to Arthur’s question that yes, it is a serious injury: a compound fracture above the knee, and a dislocation below, but that the stranger will recover.

“Now, let us see whether there’s anything else the matter, and how our ribs are?’

There was nothing else the matter, and our ribs were sound.“

When the man falls into a doze, Arthur leaves a card with his name on it, and a message that he will return the next day. He returns to Covent Garden, where he has hired lodgings for the present. Arthur is a dreamer, and this event has:

“rescued him to have a warm and sympathetic heart”.

Nevertheless, sitting before the dying fire, he thinks over his sad and sorry life, and broods over recent events. Through all this, Arthur Clennam asks himself:

“‘what have I found!’

His door was softly opened, and these spoken words startled him, and came as if they were an answer:

‘Little Dorrit.’“

This is a very long chapter, in which we meet no less than FIVE new characters, plus a surprising return!

Arthur is beginning to think that there is no easy way to help the Dorrit family. However, he still has Affery’s words in his mind, about his old sweetheart Flora; how she had remarried, but had been widowed shortly afterwards. He decides to go Mr. Casby as his daughter Flora now lives with him again. Arthur convinces himself that this may even help Little Dorrit:

“that it might—for anything he knew—it might be serviceable to the poor child, if he renewed this acquaintance”

However, the narrator reminds us how easily we can persuade ourselves to do something we wish to do, but give other reasons for it.

As soon as Arthur arrives at the house, it seems as gloomy as his mother’s house, but the memories come flooding back about the interior, which is so different:

“The furniture was formal, grave, and quaker-like, but well-kept … There was a grave clock, ticking somewhere up the staircase; and there was a songless bird in the same direction, pecking at his cage, as if he were ticking too.”

And before he even smells it, Arthur remembers the smell of its jars of old rose-leaves and lavender. Arthur is shown in almost soundlessly, and sees Mr. Casby sitting by the fire, Although twenty years or more have passed, Mr. Casby seems unchanged in appearance:

“There was the same smooth face and forehead, the same calm blue eye, the same placid air. The shining bald head, which looked so very large because it shone so much; and the long grey hair at its sides and back, like floss silk or spun glass, which looked so very benevolent because it was never cut; were not, of course, to be seen in the boy as in the old man. Nevertheless, in the Seraphic creature with the haymaking rake, were clearly to be discerned the rudiments of the Patriarch with the list shoes.”

Arthur visits Christopher Casby - James Mahoney

Purely because of his appearance and his demeanour, he is known to many people as “the Patriarch”.

“His smooth face had a bloom upon it like ripe wall-fruit. What with his blooming face, and that head, and his blue eyes, he seemed to be delivering sentiments of rare wisdom and virtue. In like manner, his physiognomical expression seemed to teem with benignity. Nobody could have said where the wisdom was, or where the virtue was, or where the benignity was; but they all seemed to be somewhere about him.”

The two begin an inconsequential conversation, and when Mr. Casby asks Arthur how he has been since last they met:

“Arthur did not think it worth while to explain that in the course of some quarter of a century he had experienced occasional slight fluctuations in his health and spirits.”

By his hesitant replies, it is evident that even after all this time, Arthur still feels nervous in Mr. Casby's presence.

When the conversation allows, Arthur mentions Little Dorrit, but nothing comes of it. Mr. Casby then tells him about Flora, and goes to fetch her. In the meantime, a quick and eager short dark man bustles into the room:

“He was dressed in black and rusty iron grey; had jet black beads of eyes; a scrubby little black chin; wiry black hair striking out from his head in prongs, like forks or hair-pins; and a complexion that was very dingy by nature, or very dirty by art, or a compound of nature and art. He had dirty hands and dirty broken nails, and looked as if he had been in the coals; he was in a perspiration, and snorted and sniffed and puffed and blew, like a little labouring steam-engine.”

This is Pancks: “And so, with a snort and a puff, he worked out by another door.”

Arthur muses on Mr. Casby’s appearance. Mr Casby used to be town-agent to Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle. However, Arthur suspects that this might not be because he had a good head for business. It seems more likely to him, that Mr. Casby looked so kind, that nobody would expect him to squeeze or screw an unfair amount for the property. Now Mr. Casby has many tenants of his own, the same probably applies, He is:

“rich in weekly tenants, and to get a good quantity of blood out of the stones of several unpromising courts and alleys.”

Considering the relationship between Mr. Casby and Pancks, Arthur surmises that Pancks is like a coaly little steam-tug, and the slow, benignant Mr. Casby is like an unwieldy ship in the river Thames:

“similarly the cumbrous Patriarch had been taken in tow by the snorting Pancks, and was now following in the wake of that dingy little craft.”

Mr. Casby returns with Flora, but Arthur is in for a shock:

“Clennam’s eyes no sooner fell upon the subject of his old passion than it shivered and broke to pieces.”

All those years away from home, Flora had stayed in his mind as she once was, and her ideal image had become fixed in his mind. But the Flora of his memory, is no more:

“Flora, always tall, had grown to be very broad too, and short of breath; but that was not much. Flora, whom he had left a lily, had become a peony; but that was not much. Flora, who had seemed enchanting in all she said and thought, was diffuse and silly. That was much. Flora, who had been spoiled and artless long ago, was determined to be spoiled and artless now. That was a fatal blow.

He is aghast to observe that Flora still acts and talks in a girlish, flirtatious manner with him, behaving as if they are in a secret liaison. Arthur wonders if it was possible that Flora was always such a chatterer. Why was he ever so captivated by her? She seems to runs on with astonishing speed, leaving very little room for breath, talking ridiculous nonsense, which makes Arthur’s head whirl. Flora giggles and titters, and tosses her head in a caricature of her girlish manner, and Arthur remains gallant.

Yet for all this, Flora is astute enough to realise that Arthur find her much changed, and clearly did once have a great affection for him:

“when your Mama came and made a scene of it with my Papa and when I was called down into the little breakfast-room where they were looking at one another with your Mama’s parasol between them seated on two chairs like mad bulls what was I to do? … for five days I had a cold in the head from crying”

and she says, almost as an excuse, how she had married Mr. Finching after he had proposed to her seven times.

Despite feeling appalled, Arthur feels sorry for Flora, and agrees to stay for dinner.

Pancks observes:

“’Bleeding Heart Yard?’ said Pancks, with a puff and a snort. ‘It’s a troublesome property. Don’t pay you badly, but rents are very hard to get there. You have more trouble with that one place than with all the places belonging to you … You can’t say, you know,’ snorted Pancks, taking one of his dirty hands out of his rusty iron-grey pockets to bite his nails, if he could find any, and turning his beads of eyes upon his employer, ‘whether they’re poor or not. They say they are, but they all say that. When a man says he’s rich, you’re generally sure he isn’t. Besides, if they are poor, you can’t help it. You’d be poor yourself if you didn’t get your rents.’”

To add to Arthur’s general confusion and light-headedness, another person appears for dinner:

“This was an amazing little old woman, with a face like a staring wooden doll too cheap for expression, and a stiff yellow wig perched unevenly on the top of her head, as if the child who owned the doll had driven a tack through it anywhere, so that it only got fastened on.”

This is Mr. F.’s aunt. She behaves rather aggressively, and her remarks are so absurd and disconnected from the rest of the conversation, that Arthur hardly knows what to say. The narrator remarks that her words may be “ingenious, or even subtle: but the key to it was wanted.” Pancks gets around the problem by agreeing with her, whatever she says. When Mr F.’s aunt says, apparently directed at Arthur (although she never meets anyone’s eyes) “I hate a fool!”, Flora decides that discretion is needed, and escorts her out of the room:

Mr. F's aunt is conducted into retirement - Phiz

When dinner is over Arthur walks home with Pancks, who tells him about his business, and says that that is what his life is about. Work is what he is made for. When Arthur asks him if he has an inclination for anything else, Pancks replies that he has an inclination to get money, and then find this very funny. Does he read? No. And they go their separate ways.

Nearing Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Arthur comes across a crowd of people. They are gathered around a litter which is being carried on men’s shoulders, through the streets. There has been an accident and they are on their way to the hospital. The man was run down by the mailcoach, which people agree goes far too fast, at twelve or fourteen miles a hour.

No one seems to understand what the injured man is saying, but when Arthur gets close to him, he realises that he is asking for water in both Italian and French. Arthur gets him some water and stays with him until he gets to the hospital. The man is:

“A little, muscular, brown man, with black hair and white teeth. A lively face, apparently. Earrings in his ears” and he has just come to the city that evening, from Marseilles.

Arthur says he will stay with him until he is in Saint Bartholomew hospital (Bart’s):

“‘Ah! Altro, Altro!’ cried the poor little man, in a faintly incredulous tone; and as they took him up, hung out his right hand to give the forefinger a back-handed shake in the air.”

He is carefully examined by a surgeon, who relies to Arthur’s question that yes, it is a serious injury: a compound fracture above the knee, and a dislocation below, but that the stranger will recover.

“Now, let us see whether there’s anything else the matter, and how our ribs are?’

There was nothing else the matter, and our ribs were sound.“

When the man falls into a doze, Arthur leaves a card with his name on it, and a message that he will return the next day. He returns to Covent Garden, where he has hired lodgings for the present. Arthur is a dreamer, and this event has:

“rescued him to have a warm and sympathetic heart”.

Nevertheless, sitting before the dying fire, he thinks over his sad and sorry life, and broods over recent events. Through all this, Arthur Clennam asks himself:

“‘what have I found!’

His door was softly opened, and these spoken words startled him, and came as if they were an answer:

‘Little Dorrit.’“

message 18:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 27, 2020 04:11AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

What an entertaining chapter—my favourite so far!

And what important new facts have we learned?

Mr. Casby is the landlord of the Bleeding Heart Yard properties, and Pancks is his agent.

Flora is his daughter, and also Arthur's old sweetheart. She is widowed, and is back living with her father.

It may be tricky to assimilate all this, as we have no less than four major characters introduced here, and two returning, and one squeezing in at the end. Charles Dickens could have made this into three chapters!

Plus we meet a surprise character—although Charles Dickens is telegraphing to us quite obviously as to who it is, with the man’s physical description, where he has just come from, and the fact that he is always saying “Altro!” We are left wondering … if this stranger is now in England, is his master here too? Or did this stranger manage to escape after all?

Although this chapter is so very long, it is screamingly funny in places. Poor Flora! Miriam Margolyes’ portrayal of her is seared into my brain—it is unforgettable :)

Not only the characters of Flora and Pancks had me giggling, but sentences like this remind me of why I love Charles Dickens’s writing so much:

“Mr Casby lived in a street in the Gray’s Inn Road, which had set off from that thoroughfare with the intention of running at one heat down into the valley, and up again to the top of Pentonville Hill; but which had run itself out of breath in twenty yards, and had stood still ever since.”

It really is a marvellously funny chapter. I love it!

And what important new facts have we learned?

Mr. Casby is the landlord of the Bleeding Heart Yard properties, and Pancks is his agent.

Flora is his daughter, and also Arthur's old sweetheart. She is widowed, and is back living with her father.

It may be tricky to assimilate all this, as we have no less than four major characters introduced here, and two returning, and one squeezing in at the end. Charles Dickens could have made this into three chapters!

Plus we meet a surprise character—although Charles Dickens is telegraphing to us quite obviously as to who it is, with the man’s physical description, where he has just come from, and the fact that he is always saying “Altro!” We are left wondering … if this stranger is now in England, is his master here too? Or did this stranger manage to escape after all?

Although this chapter is so very long, it is screamingly funny in places. Poor Flora! Miriam Margolyes’ portrayal of her is seared into my brain—it is unforgettable :)

Not only the characters of Flora and Pancks had me giggling, but sentences like this remind me of why I love Charles Dickens’s writing so much:

“Mr Casby lived in a street in the Gray’s Inn Road, which had set off from that thoroughfare with the intention of running at one heat down into the valley, and up again to the top of Pentonville Hill; but which had run itself out of breath in twenty yards, and had stood still ever since.”

It really is a marvellously funny chapter. I love it!

message 19:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 01, 2021 09:28AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

And a little more:

Flora Finching

Flora is the wonderful twittery, chattering, nonsense-babbling, almost ditzy (yet quite astute), good-hearted ex-amour of Arthur Clennam. I do love the way Charles Dickens can make her speech run on so. For me, she will always conjure up Miriam Margolyes in the part, and narrating it in her show too. She simply becomes Flora!

In the story, Arthur feels he is well out of marrying her as she has become a peony instead of a lily (I don't quite understand this bit - I love peonies!) And Charles Dickens has written her as a kind of spiteful "tribute" to an old flame.

Flora Finching is based on the real life Maria Beadnell, with whom Charles Dickens had fallen madly in love, in 1830, when he was 18. She like Flora, was pretty and flirtatious, and the daughter of a highly successful banker. (Note that Mr. Casby, Flora's father, owns lots of properties.) After three years, her parents objected to the relationship, because Charles Dickens's prospects did not look good as a struggling young court reporter and they sent Maria to Paris. How wrong time proved them to be!

Charles Dickens wrote to Maria Beadnell, "I never have loved and I never can love any human creature breathing but yourself." He was heartbroken over the break up. His portrayal of Dora Spenlow in David Copperfield was also based on his early memory of Maria, as we discussed then.

However, things changed. Although Maria had married, and was now Mrs. Henry Winter, Charles Dickens kept the flame alive, in retrospect telling his friend John Forster that his love for Maria,

"excluded every other idea from my mind for four years... I have positively stood amazed at myself ever since! The maddest romances that ever got into any boy's head and stayed there".

Of course by now Charles Dickens had begun to make quite a name as a writer, and Maria was flattered when they began to exchange letters. In 1855 Charles Dickens s wrote:

"Whatever of fancy, romance, energy, passion, aspiration and determination belong to me, I never have separated and never shall separate from the hard hearted little woman - you - whom it is nothing to say I would have died for.... that I began to fight my way out of poverty and obscurity, with one perpetual idea of you... I have never been so good a man since, as I was when you made me wretchedly happy."

Maria tried to warn him, describing herself as being “toothless, fat, old and ugly.” But Charles Dickens's own marriage was in trouble, and he did not want to believe her description. They agreed to a secret meeting without their spouses, whereupon Charles Dickens was extremely disappointed to find her, (as she had honestly described herself to be), in her forties, fat, and dull.

Charles Dickens then made sure he would only met Maria in company, and rebuffed her flirtatious attempts. His letters to her underwent a sea change, and became short and formal. Maria tried to renew the relationship, but Charles Dickens then broke it off for good.

Flora Finching

Flora is the wonderful twittery, chattering, nonsense-babbling, almost ditzy (yet quite astute), good-hearted ex-amour of Arthur Clennam. I do love the way Charles Dickens can make her speech run on so. For me, she will always conjure up Miriam Margolyes in the part, and narrating it in her show too. She simply becomes Flora!

In the story, Arthur feels he is well out of marrying her as she has become a peony instead of a lily (I don't quite understand this bit - I love peonies!) And Charles Dickens has written her as a kind of spiteful "tribute" to an old flame.

Flora Finching is based on the real life Maria Beadnell, with whom Charles Dickens had fallen madly in love, in 1830, when he was 18. She like Flora, was pretty and flirtatious, and the daughter of a highly successful banker. (Note that Mr. Casby, Flora's father, owns lots of properties.) After three years, her parents objected to the relationship, because Charles Dickens's prospects did not look good as a struggling young court reporter and they sent Maria to Paris. How wrong time proved them to be!

Charles Dickens wrote to Maria Beadnell, "I never have loved and I never can love any human creature breathing but yourself." He was heartbroken over the break up. His portrayal of Dora Spenlow in David Copperfield was also based on his early memory of Maria, as we discussed then.

However, things changed. Although Maria had married, and was now Mrs. Henry Winter, Charles Dickens kept the flame alive, in retrospect telling his friend John Forster that his love for Maria,

"excluded every other idea from my mind for four years... I have positively stood amazed at myself ever since! The maddest romances that ever got into any boy's head and stayed there".

Of course by now Charles Dickens had begun to make quite a name as a writer, and Maria was flattered when they began to exchange letters. In 1855 Charles Dickens s wrote:

"Whatever of fancy, romance, energy, passion, aspiration and determination belong to me, I never have separated and never shall separate from the hard hearted little woman - you - whom it is nothing to say I would have died for.... that I began to fight my way out of poverty and obscurity, with one perpetual idea of you... I have never been so good a man since, as I was when you made me wretchedly happy."

Maria tried to warn him, describing herself as being “toothless, fat, old and ugly.” But Charles Dickens's own marriage was in trouble, and he did not want to believe her description. They agreed to a secret meeting without their spouses, whereupon Charles Dickens was extremely disappointed to find her, (as she had honestly described herself to be), in her forties, fat, and dull.

Charles Dickens then made sure he would only met Maria in company, and rebuffed her flirtatious attempts. His letters to her underwent a sea change, and became short and formal. Maria tried to renew the relationship, but Charles Dickens then broke it off for good.

The "patriarch" is the 2nd one we have seen, with Mr. Dorrit as "Father of the Marshalsea" the other.

The "patriarch" is the 2nd one we have seen, with Mr. Dorrit as "Father of the Marshalsea" the other. Thank you for including the story on Dickens. I can't help wondering if he would have been disappointed even if Maria (also the inspiration for Dora in David Copperfield) had been more attractive, simply because she was over 40. He probably still had the picture in his mind of a young woman and it seems he always preferred young women, in his stories and his life. Almost certainly he would have gotten tired of her if he had married her, just as he did with his actual wife.

Robin...interesting points about Caseby being the 2nd patriarch in the story & Dickens’ penchant for very young women.

Robin...interesting points about Caseby being the 2nd patriarch in the story & Dickens’ penchant for very young women.Good summary, Jean.

Once again I am baffled by the language of the time.

Can anyone tell me what “screwed or jobbed” means referring to property? (see context below):

“It was said that his being town-agent to Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle was referable, not to his having the least business capacity, but to his looking so supremely benignant that nobody could suppose the property screwed or jobbed under such a man;”

I liked this chapter. It was hilariously funny, interesting and informative.

I liked this chapter. It was hilariously funny, interesting and informative. Yesterday's chapter showed how hard it was for the working class to scrape their rent together. Hard working, good people doing their best but not quite making ends meet.

In this chapter we meet the landlords of these people. The landlords don't see the hard work and difficulties. They just see rents that are hard to collect. The people behind those rents are invisible. Sad.

These last two chapters are polar opposites, showing the two sides of the one situation of poor neighbourhoods.

I also felt a bit sorry for Flora. The poor thing can't really develop and mature living in her father's home where even Arthur noticed that nothing has changed over the years. In that house, Flora also wouldn't change and would always remain girlish. There's no room for her to grow into a mature individual.

Robin, I hadn't thought of that but you are so correct. Caseby and Mr. Dorrit are much alike. They are two sides of the same coin. Patriarchs of the Rich and Poor.

Thank you for that insight.

Mona, I think that means that Caseby was such a pleasant and kind looking man that no on would believe the pressures and tensions he applied to the properties (the people renting them) that he was in control of.

He's a quiet man with a big amount of force behind him when it comes to collecting monies.

"Screwed or jobbed" would mean to be held down, unable to move and subject to whatever happens without choice or alternative.

At least, that is how I interpreted it.

Jean, thank you on the background of Flora's character. That story about Maria sounds like typical Charles Dickens. I agree with Robin in that Dickens liked young, beautiful women and didn't much like those outside a narrow parameter.

The picture at the top reminded me that my local PBS station will be rerunning the series "Dickensians" next month. It takes characters from multiple Dickens novels and puts them together - Little Nell, the Cratchits, Inspector Bucket, Miss Havisham, etc. It also has multi-racial casting, which is interesting. I don't think there are any characters from David Copperfield or Little Dorrit in it though.

The picture at the top reminded me that my local PBS station will be rerunning the series "Dickensians" next month. It takes characters from multiple Dickens novels and puts them together - Little Nell, the Cratchits, Inspector Bucket, Miss Havisham, etc. It also has multi-racial casting, which is interesting. I don't think there are any characters from David Copperfield or Little Dorrit in it though.

Loved this chapter. Loved the descriptions and new characters. In particular:

Loved this chapter. Loved the descriptions and new characters. In particular:- Mr F.'s Aunt. Funny that she doesn't have an actual name.

- Pancks. Described as dirty and loving money. But I cannot decide if that makes him a bad guy or not.

- Flora. I think I am going to like her so much better than Dora (David Copperfield). Not sure how much of a role she will have in the story. Love that Arthur has such a different view of her now.

Jean, great information on Flora and Dicken's real life.

Robin, I did not even think of Caseby and Mr. Dorrit being patriarchs of the rich and poor. Now, I see it!

And the ending. My gosh. I plan on reading the next chapter before bed.

message 25:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 27, 2020 10:54AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Robin P wrote: "The "patriarch" is the 2nd one we have seen, with Mr. Dorrit as "Father of the Marshalsea" the other... "

I like this very much. We have a variety of fathers, or father figures, in this story already.

I loved the "Dickensians!" serial. So clever :) Maybe when it starts broadcasting in the States, you could talk some more in our spin-offs thread LINK HERE, Robin.

Petra - "In that house, Flora also wouldn't change and would always remain girlish"

True, but since she had been married to Mr. Finching, it was her choice to return to her father's house when he died, and go back to her immature status.

Yes, I'd written quite a lot about Maria Beadnell for David Copperfield, so just expanded on it here, as it's even more relevant for poor Flora Finching.

I like this very much. We have a variety of fathers, or father figures, in this story already.

I loved the "Dickensians!" serial. So clever :) Maybe when it starts broadcasting in the States, you could talk some more in our spin-offs thread LINK HERE, Robin.

Petra - "In that house, Flora also wouldn't change and would always remain girlish"

True, but since she had been married to Mr. Finching, it was her choice to return to her father's house when he died, and go back to her immature status.

Yes, I'd written quite a lot about Maria Beadnell for David Copperfield, so just expanded on it here, as it's even more relevant for poor Flora Finching.

message 26:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 27, 2020 12:48PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

I often mull over the popular theme raised here, common to Victorian literature and favoured by Charles Dickens even in his personal life: the older man as protector of the younger woman

What does Arthur Clennam feel for Amy as the novel proceeds? At first he has an impulse of pity for (and interest in) Amy Dorrit. Why? Charles Dickens often chooses this viz. the difference in age between Dr. Strong and his wife, in David Copperfield or (view spoiler) in Dombey and Son, or between (view spoiler) in Bleak House.

Here, of Amy, Arthur thinks (ch 9):

"The little creature seemed so young in his eyes, that there were moments when he found himself thinking of her, if not speaking to her, as if she were a child. Perhaps he seemed as old in her eyes as she seemed young in his.”

But clearly Amy looks old facially (even if Arthur does seem to think she looks "ethereal") - as in tomorrow's chapter (14) a passing character, (view spoiler)

Amy - I still find her hard to suss - from my 21st Century viewpoint perhaps. But I'm wondering if Dickens had got some flack from his readers in Bleak House, a couple of novels earlier. Esther was a similar virtuous, hardworking and apparently modest young woman - the Victorian ideal woman. But was she really? Esther always let us know, in her parts of the narrative, how good she was. Amy never mentions it.

I have to say I do like Amy, but perhaps Charles Dickens was trying to satisfy his readers here, and presenting an ideal woman, rather than inventing a well-rounded, more believable character.

Thinking of docile, virtuous, young women - like Mary Hogarth and Ellen Ternan whom Dickens so admired in his own life. He certainly could create positive and spirited women, such as Edith Granger, Lady Dedlock and Miss Wade, without making caricatures of them. But in each case we get a strong sense that the author does not actually like or admire them.

What does Arthur Clennam feel for Amy as the novel proceeds? At first he has an impulse of pity for (and interest in) Amy Dorrit. Why? Charles Dickens often chooses this viz. the difference in age between Dr. Strong and his wife, in David Copperfield or (view spoiler) in Dombey and Son, or between (view spoiler) in Bleak House.

Here, of Amy, Arthur thinks (ch 9):

"The little creature seemed so young in his eyes, that there were moments when he found himself thinking of her, if not speaking to her, as if she were a child. Perhaps he seemed as old in her eyes as she seemed young in his.”

But clearly Amy looks old facially (even if Arthur does seem to think she looks "ethereal") - as in tomorrow's chapter (14) a passing character, (view spoiler)

Amy - I still find her hard to suss - from my 21st Century viewpoint perhaps. But I'm wondering if Dickens had got some flack from his readers in Bleak House, a couple of novels earlier. Esther was a similar virtuous, hardworking and apparently modest young woman - the Victorian ideal woman. But was she really? Esther always let us know, in her parts of the narrative, how good she was. Amy never mentions it.

I have to say I do like Amy, but perhaps Charles Dickens was trying to satisfy his readers here, and presenting an ideal woman, rather than inventing a well-rounded, more believable character.

Thinking of docile, virtuous, young women - like Mary Hogarth and Ellen Ternan whom Dickens so admired in his own life. He certainly could create positive and spirited women, such as Edith Granger, Lady Dedlock and Miss Wade, without making caricatures of them. But in each case we get a strong sense that the author does not actually like or admire them.

message 27:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 30, 2020 03:18AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

I am struck by all the contrasts - not just with Amy and Maggy, who are like chalk and cheese in every way, but also Maggie's behaviour. Dickens says she:

"took pains to improve herself, and to be very attentive and very industrious; and by degrees ... got enough to support herself, and does support herself."

How ironic that Maggie, who is at a disadvantage because of her mental ability, is independent but Amy's father, brother and sister have perfected the art of doing nothing.

We tend to give Dickens's novels convenient labels, ie. the one criticising the workhouse (Oliver Twist), the one criticising schools (Nicholas Nickleby), the one criticising the legal system (Bleak House), the one criticising unions (Hard Times) - and this one criticising government bureaucracy in the form of the Circumlocution Office.

I'm not sure he ever wrote one specifically dealing with how society treated those with deformities or mental health issues; those we now term "differently abled". Yet many of his characters in these novels fall into such a category - far more than in other classic Victorian novels, I would say.

"took pains to improve herself, and to be very attentive and very industrious; and by degrees ... got enough to support herself, and does support herself."

How ironic that Maggie, who is at a disadvantage because of her mental ability, is independent but Amy's father, brother and sister have perfected the art of doing nothing.

We tend to give Dickens's novels convenient labels, ie. the one criticising the workhouse (Oliver Twist), the one criticising schools (Nicholas Nickleby), the one criticising the legal system (Bleak House), the one criticising unions (Hard Times) - and this one criticising government bureaucracy in the form of the Circumlocution Office.

I'm not sure he ever wrote one specifically dealing with how society treated those with deformities or mental health issues; those we now term "differently abled". Yet many of his characters in these novels fall into such a category - far more than in other classic Victorian novels, I would say.

Reading the description of Mr. Casby and the comparison to his portrait when he was a child, I couldn’t quite see how he hadn’t really changed in my mind, but the picture by Phiz of the aunt leaving made it clear. The portrait is on the wall and seeing Mr. Casby at table, we can see the likeness.

Reading the description of Mr. Casby and the comparison to his portrait when he was a child, I couldn’t quite see how he hadn’t really changed in my mind, but the picture by Phiz of the aunt leaving made it clear. The portrait is on the wall and seeing Mr. Casby at table, we can see the likeness.I hadn’t thought either that we had two patriarches, but I agree.

Jean.,

Jean., I was also a bit flummoxed at first about the change of Flora from a Lily to a Peony. I also love peonies but as gorgeous as they, the regular ones which were probably prevalent in Dickens time, are multi-petalled, thereby fatter and buxom, while Lilies are thinner, being single-petaled.

I also loved the humor and the use of language in this chapter.

Petra, you might be right about the meaning of “screwed or jobbed” in this context. No one else has given me a more precise definition. I like to know how words are used in the lingo of their times.

Petra, you might be right about the meaning of “screwed or jobbed” in this context. No one else has given me a more precise definition. I like to know how words are used in the lingo of their times.

message 31:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 27, 2020 11:29AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Mona wrote: "No one else has given me a more precise definition."

Sorry Mona - I wasn't ignoring you, but I did think Petra had more or less explained it.

If you are "screwed over", then you are cheated out of some money. Perhaps it is just British slang, but it's used quite a lot here, even nowadays. And I think somewhere Charles Dickens refers to an "Old Screw" meaning an old skinflint.

Charles Dickens certainly talks about "jobbing" elsewhere. In Our Mutual Friend, he refers to:

"all the people alive who have made inventions that won't act, and all the jobbers who job in all the jobberies jobbed; though these may be regarded as the Alligators of the Dismal Swamp, and are always lying by to drag the Golden Dustman under."

So the jobbers are like alligators - not nice people!

It actually has two meanings: a "jobbing" builder indicates one who accepts casual work, so the term is a little negative. But in the quotation you ask about, it has an even more pejorative meaning. "Stock jobbing" is a term that means making quick profits on small moves of a stock. It comes again from a British slang term, for certain financial market participants. But this use is out of date now though, and perhaps only found in classic novels!

Sorry Mona - I wasn't ignoring you, but I did think Petra had more or less explained it.

If you are "screwed over", then you are cheated out of some money. Perhaps it is just British slang, but it's used quite a lot here, even nowadays. And I think somewhere Charles Dickens refers to an "Old Screw" meaning an old skinflint.

Charles Dickens certainly talks about "jobbing" elsewhere. In Our Mutual Friend, he refers to:

"all the people alive who have made inventions that won't act, and all the jobbers who job in all the jobberies jobbed; though these may be regarded as the Alligators of the Dismal Swamp, and are always lying by to drag the Golden Dustman under."

So the jobbers are like alligators - not nice people!

It actually has two meanings: a "jobbing" builder indicates one who accepts casual work, so the term is a little negative. But in the quotation you ask about, it has an even more pejorative meaning. "Stock jobbing" is a term that means making quick profits on small moves of a stock. It comes again from a British slang term, for certain financial market participants. But this use is out of date now though, and perhaps only found in classic novels!

Flora does not look as rotund in Phiz’s drawing as I expected.

Flora does not look as rotund in Phiz’s drawing as I expected.Um, aren’t most men above a certain age drawn to younger women rather than those their age?

I enjoyed all the action and characters in this chapter. It is so long that I checked the audio app on my phone twice to be sure I had not missed a chapter change.

Kathleen: Yes, apparently older men do not care for women their own age. But I’m an older woman myself, and the feeling is mutual...

Kathleen: Yes, apparently older men do not care for women their own age. But I’m an older woman myself, and the feeling is mutual...Jean: Yes, thanks.

“Screwed over” means something similar in the U.S. Except it can also have a sexual connotation.

Jobbers may be people we call contractors. I have worked for a number of them, and some of them have “screwed me over”.

But I’m still not entirely certain what jobbing a property might be...Subletting?

I have consulted an online “Dickens glossary” but it seems to be pretty sparse. These terms weren’t there.

message 34:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 27, 2020 12:31PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Mona - Your quotation again:

“It was said that his being town-agent to Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle was referable, not to his having the least business capacity, but to his looking so supremely benignant that nobody could suppose the property screwed or jobbed under such a man;”

As I said, screwed always means something bad, (except as you say in a sexual context) and Charles Dickens often uses "jobbing" in a negative way too. That's probably why he included both words, with "or" in between to make sure we understood the correct implication.

In the extra quotation I included, we might replace "alligators" nowadays with "sharks". We all know what sharks means, in a business sense.

There are various ways of screwing or jobbing a property, including subletting, or allowing more tenants in than his paperwork would show, replacing any fixtures with cheaper ones, stealing the lead from the roofs. etc.

“It was said that his being town-agent to Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle was referable, not to his having the least business capacity, but to his looking so supremely benignant that nobody could suppose the property screwed or jobbed under such a man;”

As I said, screwed always means something bad, (except as you say in a sexual context) and Charles Dickens often uses "jobbing" in a negative way too. That's probably why he included both words, with "or" in between to make sure we understood the correct implication.

In the extra quotation I included, we might replace "alligators" nowadays with "sharks". We all know what sharks means, in a business sense.

There are various ways of screwing or jobbing a property, including subletting, or allowing more tenants in than his paperwork would show, replacing any fixtures with cheaper ones, stealing the lead from the roofs. etc.

I too did not catch the patriarch of the rich and poor untill it was mentioned here! This is quite the insightful conversation, especially with how nuanced Dickens characters are. I have to wonder if Flora and Mr. F's Aunt are going to come back or not... And Miss.Wade, Tattycoram, Pet and her parents...

I too did not catch the patriarch of the rich and poor untill it was mentioned here! This is quite the insightful conversation, especially with how nuanced Dickens characters are. I have to wonder if Flora and Mr. F's Aunt are going to come back or not... And Miss.Wade, Tattycoram, Pet and her parents...

Poor Flora! I loved her, but feel so sorry for her. And am I to understand that Mr. Finching, upon his death, did not leave his wife a legacy of any sort -- just his "old Aunt"?! Is that right? I thought that was so funny -- and sad for Flora :'(

Poor Flora! I loved her, but feel so sorry for her. And am I to understand that Mr. Finching, upon his death, did not leave his wife a legacy of any sort -- just his "old Aunt"?! Is that right? I thought that was so funny -- and sad for Flora :'(

Hi Terris - I believe he did leave her rather well taken care of. She tells Arthur that "Mr. F had made a beautiful will" but that he left her the aunt in addition to that. At least that's the way I read it.

Hi Terris - I believe he did leave her rather well taken care of. She tells Arthur that "Mr. F had made a beautiful will" but that he left her the aunt in addition to that. At least that's the way I read it.

Katy wrote: "Hi Terris - I believe he did leave her rather well taken care of. She tells Arthur that "Mr. F had made a beautiful will" but that he left her the aunt in addition to that. At least that's the way ..."

Katy wrote: "Hi Terris - I believe he did leave her rather well taken care of. She tells Arthur that "Mr. F had made a beautiful will" but that he left her the aunt in addition to that. At least that's the way ..."This was my understanding too.

Which is why it's odd that Flora went back to live with her father! She positively chose to lose her independent status.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Petra - "In that house, Flora also wouldn't change and would always remain girlish"

Bionic Jean wrote: "Petra - "In that house, Flora also wouldn't change and would always remain girlish"True, but since she had been married to Mr. Finching, it was her choice to return to her father's house when he died, and go back to her immature status..."

I'd like to believe she had this choice but I'm not so sure.

One of the themes that seems to be in this story is the theme of responsibility and blame. Are we responsible for another's lives or can we help people or do we stand in their way, making it difficult for them.

Flora is childlike in her widowhood. That assumes that she was this way on her wedding day and that her husband did nothing to change this. Wasn't the husband's role to provide for his wife and keep her at home, sequestered from the cares of the World?

It seems in many novels of this time, a gentry's wife is safe, provided for, kept from the woes of the world. In other words, not given opportunities to mature, grow and gain confidence in the Self.

When Flora's husband passed away, she was as incapable of taking care of herself as on the day of her wedding. Did she have a choice but to move home and be cared for by another male, her father? I'm not sure.

Petra wrote: "When Flora's husband passed away, she was as incapable of taking care of herself as on the day of her wedding. Did she have a choice but to move home and be cared for by another male, her father? I'm not sure ..."

Good point!

Good point!

I hadn’t considered the idea of responsibility in terms of General life- like taking care of yourself and independence vs dependence. I like that. I’ve been focusing on those who have committed crimes or are accused of committing them and how their personal responsibility fits with societies influence. It’s a much broader picture to look at all the characters and their lives! Did society give her a choice as a woman? As a widow? And then all these people being shown with their different lives, some wealthy, some very poor. What have they done to deserve those lives? We’re they just born into them? A lot to consider here!

I hadn’t considered the idea of responsibility in terms of General life- like taking care of yourself and independence vs dependence. I like that. I’ve been focusing on those who have committed crimes or are accused of committing them and how their personal responsibility fits with societies influence. It’s a much broader picture to look at all the characters and their lives! Did society give her a choice as a woman? As a widow? And then all these people being shown with their different lives, some wealthy, some very poor. What have they done to deserve those lives? We’re they just born into them? A lot to consider here!Flora is quite spunky and also presumptuous to assume Arthur stayed single because of her! Her personality isn’t that of a woman who has to be taken care of by a man!

I know the clock was mentioned too, but I want to come back to that. I see it as a similar symbol as Miss Havishams clock. Only this one hasn’t stopped and it’s showing us how life has continued to go on, and things have really changed, even if one character hasn’t seemed to change much at all. I’m not sure why Mr C was said to look the same despite all the time passing, but Arthur and Flora have changed a lot and things have changed for them. I wonder if that idea will continue or if that’s all we get about that. But it’s interesting that this time Dickens focuses us on the moving of time, not the stopping. It makes me excited to see where both Arthur and Flora go from here.

I'm wondering if maybe Flora getting the money is somehow tied into "Mr. F's Aunt". Perhaps Flora has to take care of her in order to get the money? Or maybe the aunt was in charge of the money and squandered it? Flora only says she was left well off, not that she still is

I'm wondering if maybe Flora getting the money is somehow tied into "Mr. F's Aunt". Perhaps Flora has to take care of her in order to get the money? Or maybe the aunt was in charge of the money and squandered it? Flora only says she was left well off, not that she still is

message 45:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Sep 28, 2020 03:16AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Petra, Ashley and Jenny - Flora is a nicely complex character :) Although Charles Dickens made her silliness apparent, he didn't paint a vicious portrait of his erstwhile sweetheart in Flora. He remembered the good aspects of Maria Beadnell too: her quickness, acuity, kindness, and paid tribute to those - we will see much of this later.

Flora really loved Arthur, and says specifically that she did not expect Arthur to stay single because of her, Ashley, but rather that she expected he would have married someone on his travels. Yes, she is "spunky", but she is not presumptuous.

Yes, time, clocks and timepieces are always important throughout Charles Dickens's writing. There are examples in every novel :) Well spotted, Ashley. It's one of his motifs.

But it is time to move on.

Flora really loved Arthur, and says specifically that she did not expect Arthur to stay single because of her, Ashley, but rather that she expected he would have married someone on his travels. Yes, she is "spunky", but she is not presumptuous.