The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

David Copperfield

David Copperfield

>

DC, Chp. 35-37

Quite in the vein of yin and yan and perfect balance, Dickens chooses the title Enthusiasm for the next chapter because after all that Depression, Enthusiasm is the thing we all need. It all starts with Mr. Dick, whose anxiety is turned into positive energy with the help of good old Traddles, who is able to find adequate work for Mr. Dick – copying legal documents –, which imbues Mr. Dick with a sense of pride. Even Mr. Dick’s mannerism of introducing reflections on Charles I. into everything he writes is foreseen and taken care of. Good! Next, Aunt Betsey, with the help of Peggotty a.k.a. Barkis, improve David’s household matters quite a lot, and Aunt Betsey finally has it out with Mrs. Crupp – this finally happens in Chapter 37 –, cowing her impertinent spirit to such a degree that the venerable landlady dare not longer show herself. Fancy telling Mrs. Crupp that she is smelling of David’s brandy! Touché!

Although David tends to romanticize his new position, completely misinterpreting Dora’s character, he is also practically-minded enough to take up a secretaryship in Doctor Strong’s household, which takes up two hours before his work in Mr. Spenlow’s business and three more hours in the evening. Additionally, like the real Dickens – so there’s another autobiographical detail –, David is going to learn shorthand in order to be able to report on parliamentary debates. Doctor Strong has moved to Highgate – which gives David an opportunity to sneak a peek of Mrs. Steerforth’s house, where he witnesses Rosa Dartle walk the garden like an imprisoned beast –, in order to work on his dictionary. Not only his wife, but that feckless Jack Maldon, who has obtained a sinecure through the Doctor, are with him. It is quite interesting that Minnie seems to do her best in order to minimize her contact with Maldon, whereas the unsuspecting Doctor does his best (or worst) in order to encourage her to spend time with the young cadger. Well, wherever that might end?

And who else should suddenly appear like a bolt from the blue – or like a bad penny? Why, the Micawbers! Once again, Mr. Micawber is sure that something has turned up, and he invites Traddles and David to celebrate the occasion together with his family. In the course of the festivities he not only, generously, hands Traddles an I.O.U. for the money he has borrowed from him, but he also lets out that he has been employed by Uriah Heep, whom he calls his friend … I wonder if Uriah Heep has not found another dupe here. The Chapter ends with the following reflection by David:

” We parted with great heartiness on both sides; and when I had seen Traddles to his own door, and was going home alone, I thought, among the other odd and contradictory things I mused upon, that, slippery as Mr. Micawber was, I was probably indebted to some compassionate recollection he retained of me as his boy-lodger, for never having been asked by him for money. I certainly should not have had the moral courage to refuse it; and I have no doubt he knew that (to his credit be it written), quite as well as I did.”

Some of you distrust Micawber, and he certainly did not scruple too much about drawing money from Traddles. In my edition it says that Micawber was partly modeled on Dickens’s father – with regard to both his lack of financial prudence and his grandiloquence. I am afraid that Traddles will never see the money he advanced to Mr. Micawber again because the latter seems to think that writing an I.O.U. is as much of a final settlement of the money affair as paying the money back. By the way, is there anyone here who has started liking the Micawbers any better after this chapter?

Although David tends to romanticize his new position, completely misinterpreting Dora’s character, he is also practically-minded enough to take up a secretaryship in Doctor Strong’s household, which takes up two hours before his work in Mr. Spenlow’s business and three more hours in the evening. Additionally, like the real Dickens – so there’s another autobiographical detail –, David is going to learn shorthand in order to be able to report on parliamentary debates. Doctor Strong has moved to Highgate – which gives David an opportunity to sneak a peek of Mrs. Steerforth’s house, where he witnesses Rosa Dartle walk the garden like an imprisoned beast –, in order to work on his dictionary. Not only his wife, but that feckless Jack Maldon, who has obtained a sinecure through the Doctor, are with him. It is quite interesting that Minnie seems to do her best in order to minimize her contact with Maldon, whereas the unsuspecting Doctor does his best (or worst) in order to encourage her to spend time with the young cadger. Well, wherever that might end?

And who else should suddenly appear like a bolt from the blue – or like a bad penny? Why, the Micawbers! Once again, Mr. Micawber is sure that something has turned up, and he invites Traddles and David to celebrate the occasion together with his family. In the course of the festivities he not only, generously, hands Traddles an I.O.U. for the money he has borrowed from him, but he also lets out that he has been employed by Uriah Heep, whom he calls his friend … I wonder if Uriah Heep has not found another dupe here. The Chapter ends with the following reflection by David:

” We parted with great heartiness on both sides; and when I had seen Traddles to his own door, and was going home alone, I thought, among the other odd and contradictory things I mused upon, that, slippery as Mr. Micawber was, I was probably indebted to some compassionate recollection he retained of me as his boy-lodger, for never having been asked by him for money. I certainly should not have had the moral courage to refuse it; and I have no doubt he knew that (to his credit be it written), quite as well as I did.”

Some of you distrust Micawber, and he certainly did not scruple too much about drawing money from Traddles. In my edition it says that Micawber was partly modeled on Dickens’s father – with regard to both his lack of financial prudence and his grandiloquence. I am afraid that Traddles will never see the money he advanced to Mr. Micawber again because the latter seems to think that writing an I.O.U. is as much of a final settlement of the money affair as paying the money back. By the way, is there anyone here who has started liking the Micawbers any better after this chapter?

I have just made sure that the warfare between Aunt Betsey and Mrs. Crupp is actually part of Chapter 37, which is called A Little Cold Water and which is a rather short chapter – probably with regard to the quantifier “little” in its title. Still, it seems to be a very important chapter because it tells us a lot about Dora.

The little bit of cold water is, of course, meant metaphorically but it does not succeed in cooling off David’s raving enthusiasm about Dora. When he finally meets her – with the help of the untiring Miss Mills, who – by the way – seems a more likeable person to me than her childish friend – he tries to explain to her the turn that his fortunes have taken and to carefully make her realize that she, too, might have to take on certain responsibilities with regard to housekeeping. Urging her to read a cooking book, by the way, seems to show that David himself is not really aware of what life in poverty might mean to a young family. Dora cannot bear the thought of being practical-minded and of facing reality – and David … actually adores her for that. “Blind, blind, blind”, as Aunt Betsey said a little earlier.

The parting scene cleverly puts things in a nutshell and is therefore quoted here:

” 'Now don't get up at five o'clock, you naughty boy. It's so nonsensical!'

'My love,' said I, 'I have work to do.'

'But don't do it!' returned Dora. 'Why should you?'

It was impossible to say to that sweet little surprised face, otherwise than lightly and playfully, that we must work to live.

'Oh! How ridiculous!' cried Dora.

'How shall we live without, Dora?' said I.

'How? Any how!' said Dora.

She seemed to think she had quite settled the question, and gave me such a triumphant little kiss, direct from her innocent heart, that I would hardly have put her out of conceit with her answer, for a fortune.”

In a way, Dora Spenlow reminds me of the wife Dr. Lydgate in Middlemarch has taken, but I also wonder if she bears any resemblance to Dickens’s first love Mary Beadnell? If so, Dickens must by now have realized that it was perhaps for the better that that early infatuation of his came to nothing. One of my favourite quotations in this chapter is this,

”My new life had lasted for more than a week, and I was stronger than ever in those tremendous practical resolutions that I felt the crisis required. I continued to walk extremely fast, and to have a general idea that I was getting on. I made it a rule to take as much out of myself as I possibly could, in my way of doing everything to which I applied my energies. I made a perfect victim of myself. I even entertained some idea of putting myself on a vegetable diet, vaguely conceiving that, in becoming a graminivorous animal, I should sacrifice to Dora.”

This tells a lot about David in that on the one hand it shows that once he has an aim in mind, he is able to apply himself to pursuing his path, quite like Dickens himself, but on the other hand, it also shows how hopelessly naïve our hero is. I really do wonder what he likes about that pampered, childish doll Dora.

The little bit of cold water is, of course, meant metaphorically but it does not succeed in cooling off David’s raving enthusiasm about Dora. When he finally meets her – with the help of the untiring Miss Mills, who – by the way – seems a more likeable person to me than her childish friend – he tries to explain to her the turn that his fortunes have taken and to carefully make her realize that she, too, might have to take on certain responsibilities with regard to housekeeping. Urging her to read a cooking book, by the way, seems to show that David himself is not really aware of what life in poverty might mean to a young family. Dora cannot bear the thought of being practical-minded and of facing reality – and David … actually adores her for that. “Blind, blind, blind”, as Aunt Betsey said a little earlier.

The parting scene cleverly puts things in a nutshell and is therefore quoted here:

” 'Now don't get up at five o'clock, you naughty boy. It's so nonsensical!'

'My love,' said I, 'I have work to do.'

'But don't do it!' returned Dora. 'Why should you?'

It was impossible to say to that sweet little surprised face, otherwise than lightly and playfully, that we must work to live.

'Oh! How ridiculous!' cried Dora.

'How shall we live without, Dora?' said I.

'How? Any how!' said Dora.

She seemed to think she had quite settled the question, and gave me such a triumphant little kiss, direct from her innocent heart, that I would hardly have put her out of conceit with her answer, for a fortune.”

In a way, Dora Spenlow reminds me of the wife Dr. Lydgate in Middlemarch has taken, but I also wonder if she bears any resemblance to Dickens’s first love Mary Beadnell? If so, Dickens must by now have realized that it was perhaps for the better that that early infatuation of his came to nothing. One of my favourite quotations in this chapter is this,

”My new life had lasted for more than a week, and I was stronger than ever in those tremendous practical resolutions that I felt the crisis required. I continued to walk extremely fast, and to have a general idea that I was getting on. I made it a rule to take as much out of myself as I possibly could, in my way of doing everything to which I applied my energies. I made a perfect victim of myself. I even entertained some idea of putting myself on a vegetable diet, vaguely conceiving that, in becoming a graminivorous animal, I should sacrifice to Dora.”

This tells a lot about David in that on the one hand it shows that once he has an aim in mind, he is able to apply himself to pursuing his path, quite like Dickens himself, but on the other hand, it also shows how hopelessly naïve our hero is. I really do wonder what he likes about that pampered, childish doll Dora.

Chapter 35:

I honestly laughed out loud at Aunt Betsey's words she threw at Uriah. You are tight though, he is a vengeful little lickspittle, and I hope so much he will leave Aunt Betsey well alone! I don't expect him to though. I dare say it is Uriah's influence that made her stop going to Mr. Wickfield with her money. I dare say that if she had, she wouldn't just be out of money apart from 70 pounds a year from renting out her cottage - Uriah would probably have milked her into debt, losing her cottage, and now being indebted without a source of income at all. So she would have been worse off, I am sure of it!

I think David is clearly young and impulsive in this chapter. I mean, we all have had the time when we really wanted to make a good impression on someone. And I know I have had a time I had to stop going to university when I was David's age, I didn't have money, and I came up with the biggest ideas to keep me going until I had a job. It kind of worked by the way, although I'm glad I got a proper job not too long after. Anyway, he clearly wants to help, and blunders through that, while in the end it turns out not too shabby.

Oh and my first thought about the whole Mr. Jorkis-thing was 'Oh, wow, he does exist!' I already had my mind set on him being a figment of Spenlow's imagination - someone who does not come into the office because 'he's busy' etc. and that ends up not existing, but imagined by Spenlow to shove his unpopular opinions off to.

I honestly laughed out loud at Aunt Betsey's words she threw at Uriah. You are tight though, he is a vengeful little lickspittle, and I hope so much he will leave Aunt Betsey well alone! I don't expect him to though. I dare say it is Uriah's influence that made her stop going to Mr. Wickfield with her money. I dare say that if she had, she wouldn't just be out of money apart from 70 pounds a year from renting out her cottage - Uriah would probably have milked her into debt, losing her cottage, and now being indebted without a source of income at all. So she would have been worse off, I am sure of it!

I think David is clearly young and impulsive in this chapter. I mean, we all have had the time when we really wanted to make a good impression on someone. And I know I have had a time I had to stop going to university when I was David's age, I didn't have money, and I came up with the biggest ideas to keep me going until I had a job. It kind of worked by the way, although I'm glad I got a proper job not too long after. Anyway, he clearly wants to help, and blunders through that, while in the end it turns out not too shabby.

Oh and my first thought about the whole Mr. Jorkis-thing was 'Oh, wow, he does exist!' I already had my mind set on him being a figment of Spenlow's imagination - someone who does not come into the office because 'he's busy' etc. and that ends up not existing, but imagined by Spenlow to shove his unpopular opinions off to.

Chapter 36:

Well, I certainly don't like the Micawbers any better. I had to chuckle though, when Mr. Micawber seemed as wary of Mrs. Micawber's talk about never leaving him.

Also, is there anyone (except Traddles probably) surprised that Mr. Micawber leaves without paying for that second bill, while he would provide for that?

Well, I certainly don't like the Micawbers any better. I had to chuckle though, when Mr. Micawber seemed as wary of Mrs. Micawber's talk about never leaving him.

'I read the service over with a flat-candle on the previous night, and the conclusion I derived from it was, that I never could desert Mr. Micawber. And,' said Mrs. Micawber, 'though it is possible I may be mistaken in my view of the ceremony, I never will!'

'My dear,' said Mr. Micawber, a little impatiently, 'I am not conscious that you are expected to do anything of the sort.'

Also, is there anyone (except Traddles probably) surprised that Mr. Micawber leaves without paying for that second bill, while he would provide for that?

Jantine wrote: "Chapter 35:

Oh and my first thought about the whole Mr. Jorkis-thing was 'Oh, wow, he does exist!' I already had my mind set on him being a figment of Spenlow's imagination - someone who does not come into the office because 'he's busy' etc. and that ends up not existing, but imagined by Spenlow to shove his unpopular opinions off to."

Yes, Mr. Jorkins has a lot of Mrs. Harris about him, doesn't he? Apart from that, the business relation between him and Mr. Spenlow also foreshadows a similar relation (view spoiler)

Oh and my first thought about the whole Mr. Jorkis-thing was 'Oh, wow, he does exist!' I already had my mind set on him being a figment of Spenlow's imagination - someone who does not come into the office because 'he's busy' etc. and that ends up not existing, but imagined by Spenlow to shove his unpopular opinions off to."

Yes, Mr. Jorkins has a lot of Mrs. Harris about him, doesn't he? Apart from that, the business relation between him and Mr. Spenlow also foreshadows a similar relation (view spoiler)

Tristram wrote: "Urging her to read a cooking book, by the way, seems to show that David himself is not really aware of what life in poverty might mean to a young family."

Perhaps you are right. However, I thought it was more that he tried to ease Dora into realising they would not be able to afford a cook. Seeing how she took even this, imagine how she would have reacted to 'learn how to cook decent but cheap meals, learn how to sew your own clothes, economically, instead of having them tailored for you, learn how to clean your own house instead of adding more knick-knacks to clean, and learn how to garden your own vegetables instead of looking at pretty flowers grown by a gardener'. It would have killed her, I think, the idea of learning a bit of numbers and balancing them, and reading a cook book, already almost did. My bet is that David unconsciously knew she was not up to it.

And yes, just like Agnes, Miss Mills is way more down to earth than Dora. She too would make a way better wife to David than Dora ever could. I simply want to give her a kick under the ass and tell her to get of it and get some sense of independence and reality.

Perhaps you are right. However, I thought it was more that he tried to ease Dora into realising they would not be able to afford a cook. Seeing how she took even this, imagine how she would have reacted to 'learn how to cook decent but cheap meals, learn how to sew your own clothes, economically, instead of having them tailored for you, learn how to clean your own house instead of adding more knick-knacks to clean, and learn how to garden your own vegetables instead of looking at pretty flowers grown by a gardener'. It would have killed her, I think, the idea of learning a bit of numbers and balancing them, and reading a cook book, already almost did. My bet is that David unconsciously knew she was not up to it.

And yes, just like Agnes, Miss Mills is way more down to earth than Dora. She too would make a way better wife to David than Dora ever could. I simply want to give her a kick under the ass and tell her to get of it and get some sense of independence and reality.

What’s in a name? This book must set the record for the number of different names and nicknames a single character has. I have not been keeping an exact tally of how many names David gets during the novel but am curious about what others think about the “Master Copperfield” and “Mr Copperfield” by which Uriah Heep calls David. Is it as simple as by using Master Copperfield Heep is diminishing the stature of David?

And more on names ... who knew a ship destined to be part of the navy in WW1 was named the Tommy Traddles? Julie has told us during our reading of BR that there is both a type of apple and a fish called the Dolly Varden. In England there are multiple pubs and other properties that bear Dickensian names and we have just learned that a guitar of Keith Richards is named Micawber.

What else is out there that can be linked by name to Dickensian characters?

And more on names ... who knew a ship destined to be part of the navy in WW1 was named the Tommy Traddles? Julie has told us during our reading of BR that there is both a type of apple and a fish called the Dolly Varden. In England there are multiple pubs and other properties that bear Dickensian names and we have just learned that a guitar of Keith Richards is named Micawber.

What else is out there that can be linked by name to Dickensian characters?

As far as I know, young boys would be called 'Master'. So with calling David that, Uriah basically tells David he's still a kid in Uriah's eyes every time. So yes, it is quite diminishing.

No, I didn't find the Micawbers any more likable in this segment.

No, I didn't find the Micawbers any more likable in this segment. Through chapter 36, I thought to myself that no minor character has been named in any book while hardly being seen more than Dora. I was getting a bit fed up with all of David's talk of her when we've barely seen her in these pages. Ah! But there she is in chapter 37! And, just like THAT, I was longing for the reams of pages that only mentioned her name. What a dolt. And this time she's threatening to burn Jip's nose on a hot teapot. I looked it up -- the RSPCA was founded 25 years prior to David Copperfield's publication. Hopefully, someone will report Dora and they'll lock her up. Both Dora and Flora Finching may be based on Maria Beadnell, but Dora is not Flora. I won't have it. Flora is a nervous chatterer, but she has both a brain and a heart. Dora is nothing but a shiny ornament.

I'm impressed that David is putting his nose to the grindstone and working 3 jobs in order to make ends meet.

I'm impressed that David is putting his nose to the grindstone and working 3 jobs in order to make ends meet. By the way, I've been a vegetarian since 1986, and for over a year now I've been a whole-food, plant-based vegan. And I've never heard the word "graminivorous" before. I guess I still haven't reached the point where I'm just grazing yet.

Re: Jack Maldon -- maybe the name Jack was so common that Jacks often used both names for specificity. It's a theory. Or there are a few names out there that just beg to be said together. My brother had a friend once by the name of Stuart Bean. He didn't go by Stuart or Stu. He was called Stu Bean, all together like one word - stuBEAN. JackMaldon flows nicely.

Peter wrote: "What else is out there that can be linked by name to Dickensian characters?..."

Peter wrote: "What else is out there that can be linked by name to Dickensian characters?..."Pickwick Tea - https://www.pickwicktea.com/

Noddy Boffin furniture - https://www.noddyboffin.com/

And, of course, Gamp became another name for an umbrella, though I think that's considered archaic now. By rights, someone should have probably named a brand of gin after her.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "What else is out there that can be linked by name to Dickensian characters?..."

Pickwick Tea - https://www.pickwicktea.com/

Noddy Boffin furniture - https://www.noddyboffin.com/

And..."

Mary Lou

Thanks for this. There is clearly an industry churning away at naming all things after Dickens in some way.

I agree with your comments about Dora. Let’s say it. Poor David. While he is busy working at multiple jobs Dora is fretting and frittering away her life. What a wonderful bit of research about the RSPCA!

Pickwick Tea - https://www.pickwicktea.com/

Noddy Boffin furniture - https://www.noddyboffin.com/

And..."

Mary Lou

Thanks for this. There is clearly an industry churning away at naming all things after Dickens in some way.

I agree with your comments about Dora. Let’s say it. Poor David. While he is busy working at multiple jobs Dora is fretting and frittering away her life. What a wonderful bit of research about the RSPCA!

Jantine wrote: "As far as I know, young boys would be called 'Master'. So with calling David that, Uriah basically tells David he's still a kid in Uriah's eyes every time. So yes, it is quite diminishing."

I agree: Calling David "Master Copperfield" is a very insidious way of Uriah's to express his contempt for his rival, or the person he must have seen as his rival for a while. What I also noticed is that the first few times Uriah calls David "Master Copperfield" he corrects himself, probably to draw more attention to this belittlement, but in the course of a conversation the Master completely replaces the Mister.

I agree: Calling David "Master Copperfield" is a very insidious way of Uriah's to express his contempt for his rival, or the person he must have seen as his rival for a while. What I also noticed is that the first few times Uriah calls David "Master Copperfield" he corrects himself, probably to draw more attention to this belittlement, but in the course of a conversation the Master completely replaces the Mister.

Mary Lou wrote: "No, I didn't find the Micawbers any more likable in this segment.

Through chapter 36, I thought to myself that no minor character has been named in any book while hardly being seen more than Dora..."

There must be a connection between Dora and Flora because after all, both names rhyme - and the connection is undoubtedly Maria Beadnell. Like you, Mary Lou, I find Dora absolutely annoying and exhausting, but as the old saying goes, Love does make a person blind. David's blindness, however, amount to stupidity.

Through chapter 36, I thought to myself that no minor character has been named in any book while hardly being seen more than Dora..."

There must be a connection between Dora and Flora because after all, both names rhyme - and the connection is undoubtedly Maria Beadnell. Like you, Mary Lou, I find Dora absolutely annoying and exhausting, but as the old saying goes, Love does make a person blind. David's blindness, however, amount to stupidity.

I don't know, I find Dora kinda cute. She's spoiled and hasn't had a lot of experience in life, poor girl, but she has a good heart, like our silly David. And unlike the two other spoiled brats of the novel: Little Emily and Steerforth, who as spoiled brats go really take the cake. Oddly I find Steerforth and Emily quite suited to one another. They've both had the same up-bringing, barring their social class: a blind fawning parent who is convinced that his/her child is perfection incarnate. No wonder they become such monsters of egotism, these children.

I don't know, I find Dora kinda cute. She's spoiled and hasn't had a lot of experience in life, poor girl, but she has a good heart, like our silly David. And unlike the two other spoiled brats of the novel: Little Emily and Steerforth, who as spoiled brats go really take the cake. Oddly I find Steerforth and Emily quite suited to one another. They've both had the same up-bringing, barring their social class: a blind fawning parent who is convinced that his/her child is perfection incarnate. No wonder they become such monsters of egotism, these children.

There's a fish & chips restaurant chain in Vancouver called Pickwick's.

There's a fish & chips restaurant chain in Vancouver called Pickwick's.https://foursquare.com/v/mr-pickwicks...

Ulysse wrote: "There's a fish & chips restaurant chain in Vancouver called Pickwick's."

Ulysse wrote: "There's a fish & chips restaurant chain in Vancouver called Pickwick's."I don't even eat fish, but I'd find something there so I could give them my business. :-)

Ulysse wrote: "I don't know, I find Dora kinda cute. She's spoiled and hasn't had a lot of experience in life, poor girl, but she has a good heart, like our silly David. And unlike the two other spoiled brats of ..."

The female character in Dickens I really fell in love with was Dolly Varden, and Kim always tried to talk me out of it ;-) In this novel, I must say that I look at Miss Dartle with a certain amount of fascination, and she could be a woman I would be able to have an interesting conversation with.

The female character in Dickens I really fell in love with was Dolly Varden, and Kim always tried to talk me out of it ;-) In this novel, I must say that I look at Miss Dartle with a certain amount of fascination, and she could be a woman I would be able to have an interesting conversation with.

Tristram wrote: "The female character in Dickens I really fell in love with was Dolly Varden, and Kim always tried to talk me out of it ;-)

Yuk. I rolled my eyes just seeing her name mentioned by you once again. How you can like that spoiled brat but dislike the angelic Little Nell I'll never understand. :-)

Yuk. I rolled my eyes just seeing her name mentioned by you once again. How you can like that spoiled brat but dislike the angelic Little Nell I'll never understand. :-)

Tristram wrote: "I am beginning to wonder whether those writhing movements of Uriah’s are not a symptom of some kind of nervous disease that Dickens might have observed in one of his contemporaries. Or are they just a mannerism?"

I looked it up (of course) and found this:

Uriah Heep also shakes a lot (wiggles), which modern psychologists feel could be due to neurological disorder called dystonia. Dystonia is a movement disorder in which a person's muscles contract uncontrollably. The contraction causes the affected body part to twist involuntarily, resulting in repetitive movements or abnormal postures. Dystonia can affect one muscle, a muscle group, or the entire body. Dystonia affects about 1% of the population, and women are more prone to it than men.

Symptoms of dystonia can range from very mild to severe. Dystonia can affect different body parts, and often the symptoms of dystonia progress through stages. Some early symptoms include:

A "dragging leg"

Cramping of the foot

Involuntary pulling of the neck

Uncontrollable blinking

Speech difficulties

Stress or fatigue may bring on the symptoms or cause them to worsen. People with dystonia often complain of pain and exhaustion because of the constant muscle contractions.

If dystonia symptoms occur in childhood, they generally appear first in the foot or hand. But then they quickly progress to the rest of the body. After adolescence, though, the progression rate tends to slow down.

When dystonia appears in early adulthood, it typically begins in the upper body. Then there is a slow progression of symptoms. Dystonias that start in early adulthood remain focal or segmental: They affect either one part of the body or two or more adjacent body parts.

Most cases of dystonia do not have a specific cause. Dystonia seems to be related to a problem in the basal ganglia. That's the area of the brain that is responsible for initiating muscle contractions. The problem involves the way the nerve cells communicate.

Idiopathic or primary dystonia is often inherited from a parent. Some carriers of the disorder may never develop a dystonia themselves. And the symptoms may vary widely among members of the same family.

Dystonias are classified by the body part they affect:

Generalized dystonia affects most of or all of the body.

Focal dystonia affects just a specific body part.

Multifocal dystonia affects more than one unrelated body part.

Segmental dystonia involves adjacent body parts.

Hemidystonia affects the arm and leg on the same side of the body.

Blepharospasm is a type of dystonia that affects the eyes. It usually begins with uncontrollable blinking. At first, typically, it affects just one eye. Eventually, though, both eyes are affected. The spasms cause the eyelids to involuntarily close. Sometimes they even cause them to remain closed. The person may have normal vision. But this permanent closing of the eyelids makes the person functionally blind.

Cervical dystonia, or torticollis, is the most common type. Cervical dystonia typically occurs in middle-aged individuals. It has, though, been reported in people of all ages. Cervical dystonia affects the neck muscles, causing the head to twist and turn or be pulled backward or forward.

Cranial dystonia affects the head, face, and neck muscles.

Oromandibular dystonia causes spasms of the jaw, lips, and tongue muscles. This dystonia can cause problems with speech and swallowing.

Spasmodic dystonia affects the throat muscles that are responsible for speech.

Torsion dystonia is a very rare disorder. It affects the entire body and seriously disables the person who has it. Symptoms generally appear in childhood and get worse as the person ages. Researchers have found that torsion dystonia is possibly inherited, caused by a mutation in the gene DYT1.

So does Uriah Heep have dystonia? I have no idea.

I looked it up (of course) and found this:

Uriah Heep also shakes a lot (wiggles), which modern psychologists feel could be due to neurological disorder called dystonia. Dystonia is a movement disorder in which a person's muscles contract uncontrollably. The contraction causes the affected body part to twist involuntarily, resulting in repetitive movements or abnormal postures. Dystonia can affect one muscle, a muscle group, or the entire body. Dystonia affects about 1% of the population, and women are more prone to it than men.

Symptoms of dystonia can range from very mild to severe. Dystonia can affect different body parts, and often the symptoms of dystonia progress through stages. Some early symptoms include:

A "dragging leg"

Cramping of the foot

Involuntary pulling of the neck

Uncontrollable blinking

Speech difficulties

Stress or fatigue may bring on the symptoms or cause them to worsen. People with dystonia often complain of pain and exhaustion because of the constant muscle contractions.

If dystonia symptoms occur in childhood, they generally appear first in the foot or hand. But then they quickly progress to the rest of the body. After adolescence, though, the progression rate tends to slow down.

When dystonia appears in early adulthood, it typically begins in the upper body. Then there is a slow progression of symptoms. Dystonias that start in early adulthood remain focal or segmental: They affect either one part of the body or two or more adjacent body parts.

Most cases of dystonia do not have a specific cause. Dystonia seems to be related to a problem in the basal ganglia. That's the area of the brain that is responsible for initiating muscle contractions. The problem involves the way the nerve cells communicate.

Idiopathic or primary dystonia is often inherited from a parent. Some carriers of the disorder may never develop a dystonia themselves. And the symptoms may vary widely among members of the same family.

Dystonias are classified by the body part they affect:

Generalized dystonia affects most of or all of the body.

Focal dystonia affects just a specific body part.

Multifocal dystonia affects more than one unrelated body part.

Segmental dystonia involves adjacent body parts.

Hemidystonia affects the arm and leg on the same side of the body.

Blepharospasm is a type of dystonia that affects the eyes. It usually begins with uncontrollable blinking. At first, typically, it affects just one eye. Eventually, though, both eyes are affected. The spasms cause the eyelids to involuntarily close. Sometimes they even cause them to remain closed. The person may have normal vision. But this permanent closing of the eyelids makes the person functionally blind.

Cervical dystonia, or torticollis, is the most common type. Cervical dystonia typically occurs in middle-aged individuals. It has, though, been reported in people of all ages. Cervical dystonia affects the neck muscles, causing the head to twist and turn or be pulled backward or forward.

Cranial dystonia affects the head, face, and neck muscles.

Oromandibular dystonia causes spasms of the jaw, lips, and tongue muscles. This dystonia can cause problems with speech and swallowing.

Spasmodic dystonia affects the throat muscles that are responsible for speech.

Torsion dystonia is a very rare disorder. It affects the entire body and seriously disables the person who has it. Symptoms generally appear in childhood and get worse as the person ages. Researchers have found that torsion dystonia is possibly inherited, caused by a mutation in the gene DYT1.

So does Uriah Heep have dystonia? I have no idea.

Tristram wrote: "There must be a connection between Dora and Flora because after all, both names rhyme - and the connection is undoubtedly Maria Beadnell."

I would like to know if Maria Beadnell knew she was Dora and later Flora. I don't think I would be pleased if it was me.

Maria Beadnell was the first love of Charles Dickens. They met in 1830 and he fell madly in love with her. For Charles it was love at first sight. His mind was quickly filled with thoughts of everlasting romance and marriage. However Maria’s parents did not approve of the relationship. Mr. Beadnell was a banker. He felt that Charles was too young and lacking in prospects to be considered a serious suitor.

During these years Dickens worked as a court stenographer and shorthand reporter. His own dissatisfaction with his career and a desire to make a more favorable impression with the Beadnells lead him to consider becoming an actor. He even went so far as to schedule an audition. However he was sick on that day and missed his appointment. The youthful Maria later inspired the character of Dora in David Copperfield. We’ll never know the nature of Maria’s feelings for Charles. She sometimes treated him with indifference and sometimes seemed to encourage his affections. Later in life she claimed that she truly cared for him.

In early 1833, when Charles became twenty one, he threw himself a coming-of-age party. The Beadnells were invited and accepted the invitation. During the evening Dickens was able to speak privately to Maria. He spoke of his feelings for her. She insulted him badly by referring to him as a “boy”. Their relationship ended later that year. Maria Beadnell went on to become Mrs. Henry Winter.

After a twenty-four year separation Maria contacted Dickens. They were both married and Dickens, while lacking in prospects in his youth, had become a famous author. Dickens was thrilled upon receiving her letter. It brought back the memories of his intense love for her and perhaps fantasies of what might have been. In 1855 they agreed to a secret meeting without their spouses. Maria warned Dickens that she was not the same young woman that he remembered. Despite her warnings he apparently was surprised at the changes he noticed in his first love.

Dickens’s feelings inspired him to base the character of of Flora Finching in Little Dorrit on Maria.

......Flora, always tall, had grown to be very broad too, and short of breath; but that was not much. Flora, whom he had left a lily, had become a peony; but that was not much. Flora, who had seemed enchanting in all she said and thought, was diffuse and silly. That was much. Flora, who had been spoiled and artless long ago, was determined to be spoiled and artless now. That was a fatal blow. – Little Dorrit

They met once more for a dinner with their spouses. However after that, despite Maria’s wishes for further contact, Dickens avoided her.

I would like to know if Maria Beadnell knew she was Dora and later Flora. I don't think I would be pleased if it was me.

Maria Beadnell was the first love of Charles Dickens. They met in 1830 and he fell madly in love with her. For Charles it was love at first sight. His mind was quickly filled with thoughts of everlasting romance and marriage. However Maria’s parents did not approve of the relationship. Mr. Beadnell was a banker. He felt that Charles was too young and lacking in prospects to be considered a serious suitor.

During these years Dickens worked as a court stenographer and shorthand reporter. His own dissatisfaction with his career and a desire to make a more favorable impression with the Beadnells lead him to consider becoming an actor. He even went so far as to schedule an audition. However he was sick on that day and missed his appointment. The youthful Maria later inspired the character of Dora in David Copperfield. We’ll never know the nature of Maria’s feelings for Charles. She sometimes treated him with indifference and sometimes seemed to encourage his affections. Later in life she claimed that she truly cared for him.

In early 1833, when Charles became twenty one, he threw himself a coming-of-age party. The Beadnells were invited and accepted the invitation. During the evening Dickens was able to speak privately to Maria. He spoke of his feelings for her. She insulted him badly by referring to him as a “boy”. Their relationship ended later that year. Maria Beadnell went on to become Mrs. Henry Winter.

After a twenty-four year separation Maria contacted Dickens. They were both married and Dickens, while lacking in prospects in his youth, had become a famous author. Dickens was thrilled upon receiving her letter. It brought back the memories of his intense love for her and perhaps fantasies of what might have been. In 1855 they agreed to a secret meeting without their spouses. Maria warned Dickens that she was not the same young woman that he remembered. Despite her warnings he apparently was surprised at the changes he noticed in his first love.

Dickens’s feelings inspired him to base the character of of Flora Finching in Little Dorrit on Maria.

......Flora, always tall, had grown to be very broad too, and short of breath; but that was not much. Flora, whom he had left a lily, had become a peony; but that was not much. Flora, who had seemed enchanting in all she said and thought, was diffuse and silly. That was much. Flora, who had been spoiled and artless long ago, was determined to be spoiled and artless now. That was a fatal blow. – Little Dorrit

They met once more for a dinner with their spouses. However after that, despite Maria’s wishes for further contact, Dickens avoided her.

Kim wrote: "Uriah Heep also shakes a lot (wiggles), which modern psychologists feel could be due to neurological disorder called dystonia. "

Kim wrote: "Uriah Heep also shakes a lot (wiggles), which modern psychologists feel could be due to neurological disorder called dystonia. "Well, shoot. Now I feel sorry for him. I realize disabled people can be jerks, too, but I feel as if some of that is a reaction to their physical pain or emotional anguish. It's so much easier to hate someone who is physically fit.

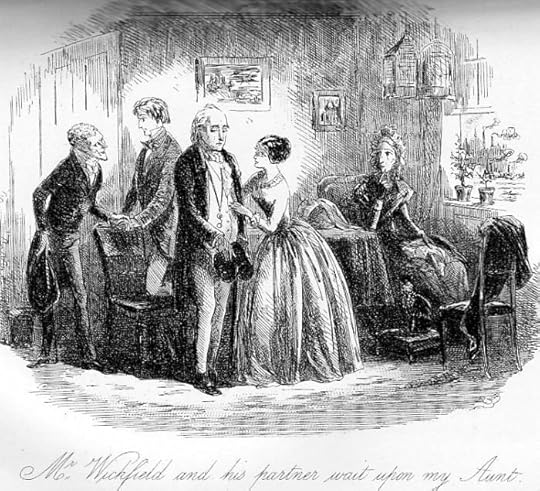

Mr. Wickfield and his partner wait upon my Aunt.

Chapter 35

Phiz

Commentary:

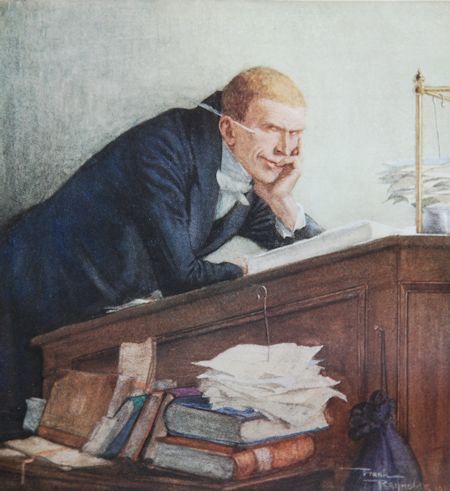

For the first illustration in the twelfth monthly number, which was issued in April 1850 and comprises chapters 35 through 37, Phiz elaborates upon the much altered outward condition of Betsey Trotwood, dramatizing the damaged psyche of her old friend and business agent, Mr. Wickfield, Phiz has realized the following moment:

I opened the door, and admitted, not only Mr. Wickfield, but Uriah Heep. I had not seen Mr. Wickfield for some time. I was prepared for a great change in him, after what I had heard from Agnes, but his appearance shocked me.

It was not that he looked many years older, though still dressed with the old scrupulous cleanliness; or that there was an unwholesome ruddiness upon his face; or that his eyes were full and bloodshot; or that there was a nervous trembling in his hand, the cause of which I knew, and had for some years seen at work. It was not that he had lost his good looks, or his old bearing of a gentleman—for that he had not—but the thing that struck me most, was, that with the evidences of his native superiority still upon him, he should submit himself to that crawling impersonation of meanness, Uriah Heep. The reversal of the two natures, in their relative positions, Uriah’s of power and Mr. Wickfield’s of dependence, was a sight more painful to me than I can express. If I had seen an Ape taking command of a Man, I should hardly have thought it a more degrading spectacle.

He appeared to be only too conscious of it himself. When he came in, he stood still; and with his head bowed, as if he felt it. This was only for a moment; for Agnes softly said to him, "Papa! Here is Miss Trotwood — and Trotwood, whom you have not seen for a long while!" and then he approached, and constrainedly gave my aunt his hand, and shook hands more cordially with me. In the moment’s pause I speak of, I saw Uriah’s countenance form itself into a most ill-favoured smile. Agnes saw it too, I think, for she shrank from him.

The picture, like the one preceding it, "My Aunt astonishes me" (the second illustration for March), is set in David's sitting-room and contains five figures: Uriah Heep (left), David Copperfield, Mr. Wickfield and his daughter, Agnes (centre) and slightly to the rear of the scene, Aunt Betsey, the only character seated, with her cat on her ottoman, again as in the previous plate. Significant background details include two paintings (upper centre), two birdcages (upper right),and two potted plants (centre right). Translated directly from Dickens's text are Uriah Heep's blue bag (left), Uriah's shaking hands with David, who has just admitted him and his legal partner, and Aunt Betsey's inscrutable (or, as the writer describes it, "imperturbable") countenance as she studies Mr. Wickfield, curiously abstracted, as if he is unaware of the presence of the others or even his surroundings.

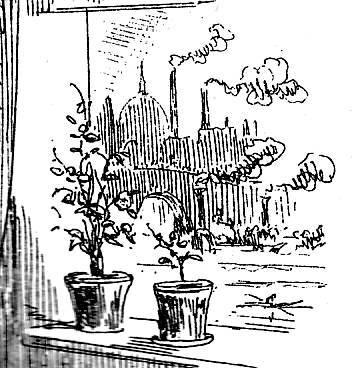

Much of the composition of the plate has been suggested to Phiz directly by the text, in particular, David's "easy chair imitating [his] aunt's much easier chair in its position at the open window" and the pair of bird-cages "hanging, just as they had hung so long in the parlour window of the cottage" near Dover. These details, then, are significant in showing Aunt Betsey's attempt to synthesize her former existence with David's London life-style. The green fan that the text mentions as "screwed on to the window-sill", however, Phiz has transposed to Aunt Betsey's lap. Phiz has also added the vista of smoking chimneys and the dome of St. Paul's Cathedral to contrast the plants on the window-sill, which recall her interrupted gardening in the earlier illustration "I make myself known to my Aunt"; these potted plants, which closely resemble those in the lower-right-hand register of that September plate, seem intended to emphasize the old, "green" life that her financial reversal has forced Betsey Trotwood to renounce.

Those familiar with the geography of London would recognize the improbability of the vista outside David's window at York House in the Adelphi block on Buckingham Street, adjacent to the north side of the Thames, including the dome of St. Paul's Cathedral. The "Dickens' London" map on David Perdue's website confirms that a window fronting the Thames in the Adelphi buildings, about a block from Warren's Blacking, would not have commanded a view of St. Paul's Cathedral, some half-mile away to the east (the Doctors' Commons, where David is articling as a Proctor, is in Old St. Paul's churchyard, and therefore was an easy walk from the Adelphi buildings). If the window were on the east rather than the south side of David's residence, the dome of St. Paul's would have been a significant aspect of the vista.

The physical situation of David's Adelphi rooms is a strongly autobiographical element in the quasi-autobiographical novel in several ways. First of all, David procures a bed for Mr. Dick around the corner from his apartments, in a chandler's shop in Hungerford Market, on the Thames. David recalls that the market was "a very different place in those days" (opening of ch. 35), because it was largely rebuilt in 1831; as a boy Dickens probably knew the market well because it was adjacent to Hungerford Stairs, where the imfamous blacking warehouse was located. In the second place, as a young shorthand reporter Dickens occupied rooms in York House on Buckingham Street, and this building most critics propose is the "model for Mrs. Crupp's residence".

The paintings, which Phiz juxtaposes to the heads of Mr. Wickfield, Agnes, and Aunt Betsey, are other conspicuous added details. The import of the smaller picture, a portrait of a woman, is unclear. However, through the larger picture Phiz further heightens the contrast between London and Dover, for this larger, central painting might be entitled "Sunrise at Dover," since it depicts a man-made and a natural landmark, Dover Castle (left) and the white cliffs (right), in sharp contrast to the polluted scene outside David's window. The placement of the painting also draws the eye forward to the contrasting heads of Mr. Wickfield and his devoted daughter. While he seems utterly detached from the scene, Agnes's expression suggests her solicitous concern for his health. She, like Betsey Trotwood, studies him, but David's aunt seems by comparison shocked at the profound changes she sees in her old friend, whose expression exemplifies the title of the chapter, "Depression."

Phiz's added vista of smoking chimneys and St. Paul's.

The painting of Dover castle

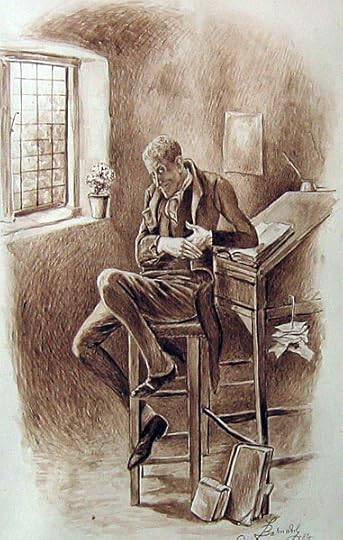

"I parted from him, poor fellow, at the corner of the street, with his great kite at his back"

Chapter 35

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘What can we do, Trotwood?’ said Mr. Dick. ‘There’s the Memorial-’

‘To be sure there is,’ said I. ‘But all we can do just now, Mr. Dick, is to keep a cheerful countenance, and not let my aunt see that we are thinking about it.’

He assented to this in the most earnest manner; and implored me, if I should see him wandering an inch out of the right course, to recall him by some of those superior methods which were always at my command. But I regret to state that the fright I had given him proved too much for his best attempts at concealment. All the evening his eyes wandered to my aunt’s face, with an expression of the most dismal apprehension, as if he saw her growing thin on the spot. He was conscious of this, and put a constraint upon his head; but his keeping that immovable, and sitting rolling his eyes like a piece of machinery, did not mend the matter at all. I saw him look at the loaf at supper (which happened to be a small one), as if nothing else stood between us and famine; and when my aunt insisted on his making his customary repast, I detected him in the act of pocketing fragments of his bread and cheese; I have no doubt for the purpose of reviving us with those savings, when we should have reached an advanced stage of attenuation.

My aunt, on the other hand, was in a composed frame of mind, which was a lesson to all of us—to me, I am sure. She was extremely gracious to Peggotty, except when I inadvertently called her by that name; and, strange as I knew she felt in London, appeared quite at home. She was to have my bed, and I was to lie in the sitting-room, to keep guard over her. She made a great point of being so near the river, in case of a conflagration; and I suppose really did find some satisfaction in that circumstance.

‘Trot, my dear,’ said my aunt, when she saw me making preparations for compounding her usual night-draught, ‘No!’

‘Nothing, aunt?’

‘Not wine, my dear. Ale.’

‘But there is wine here, aunt. And you always have it made of wine.’

‘Keep that, in case of sickness,’ said my aunt. ‘We mustn’t use it carelessly, Trot. Ale for me. Half a pint.’

I thought Mr. Dick would have fallen, insensible. My aunt being resolute, I went out and got the ale myself. As it was growing late, Peggotty and Mr. Dick took that opportunity of repairing to the chandler’s shop together. I parted from him, poor fellow, at the corner of the street, with his great kite at his back, a very monument of human misery.

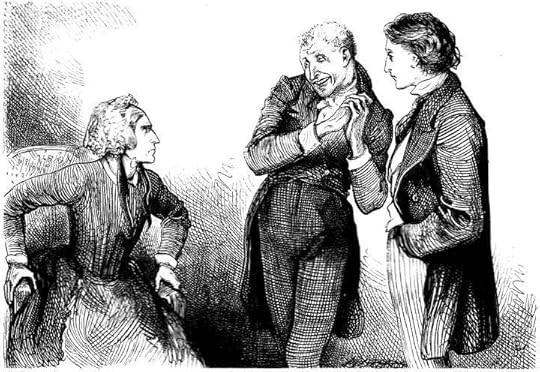

"Deuce take the man!" said my aunt, sternly, "What's he about? Don't be galvanic, Sir!"

Chapter 35

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘Well, Wickfield!’ said my aunt; and he looked up at her for the first time. ‘I have been telling your daughter how well I have been disposing of my money for myself, because I couldn’t trust it to you, as you were growing rusty in business matters. We have been taking counsel together, and getting on very well, all things considered. Agnes is worth the whole firm, in my opinion.’

‘If I may umbly make the remark,’ said Uriah Heep, with a writhe, ‘I fully agree with Miss Betsey Trotwood, and should be only too appy if Miss Agnes was a partner.’

‘You’re a partner yourself, you know,’ returned my aunt, ‘and that’s about enough for you, I expect. How do you find yourself, sir?’

In acknowledgement of this question, addressed to him with extraordinary curtness, Mr. Heep, uncomfortably clutching the blue bag he carried, replied that he was pretty well, he thanked my aunt, and hoped she was the same.

‘And you, Master—I should say, Mister Copperfield,’ pursued Uriah. ‘I hope I see you well! I am rejoiced to see you, Mister Copperfield, even under present circumstances.’ I believed that; for he seemed to relish them very much. ‘Present circumstances is not what your friends would wish for you, Mister Copperfield, but it isn’t money makes the man: it’s—I am really unequal with my umble powers to express what it is,’ said Uriah, with a fawning jerk, ‘but it isn’t money!’

Here he shook hands with me: not in the common way, but standing at a good distance from me, and lifting my hand up and down like a pump handle, that he was a little afraid of.

‘And how do you think we are looking, Master Copperfield,—I should say, Mister?’ fawned Uriah. ‘Don’t you find Mr. Wickfield blooming, sir? Years don’t tell much in our firm, Master Copperfield, except in raising up the umble, namely, mother and self—and in developing,’ he added, as an afterthought, ‘the beautiful, namely, Miss Agnes.’

He jerked himself about, after this compliment, in such an intolerable manner, that my aunt, who had sat looking straight at him, lost all patience.

‘Deuce take the man!’ said my aunt, sternly, ‘what’s he about? Don’t be galvanic, sir!’

‘I ask your pardon, Miss Trotwood,’ returned Uriah; ‘I’m aware you’re nervous.’

‘Go along with you, sir!’ said my aunt, anything but appeased. ‘Don’t presume to say so! I am nothing of the sort. If you’re an eel, sir, conduct yourself like one. If you’re a man, control your limbs, sir! Good God!’ said my aunt, with great indignation, ‘I am not going to be serpentined and corkscrewed out of my senses!’

Mr. Heep was rather abashed, as most people might have been, by this explosion; which derived great additional force from the indignant manner in which my aunt afterwards moved in her chair, and shook her head as if she were making snaps or bounces at him. But he said to me aside in a meek voice:

‘I am well aware, Master Copperfield, that Miss Trotwood, though an excellent lady, has a quick temper (indeed I think I had the pleasure of knowing her, when I was a numble clerk, before you did, Master Copperfield), and it’s only natural, I am sure, that it should be made quicker by present circumstances. The wonder is, that it isn’t much worse! I only called to say that if there was anything we could do, in present circumstances, mother or self, or Wickfield and Heep,—we should be really glad. I may go so far?’ said Uriah, with a sickly smile at his partner.

Kim wrote: "I would like to know if Maria Beadnell ..."

Kim wrote: "I would like to know if Maria Beadnell ..."Interesting. For some reason, I was under the impression that Charles and Maria were engaged, and her parents forced them to break up (maybe that was Flora and Arthur?). I didn't realize Maria was stringing him along. No wonder he was less than kind in his various literary portrayals of her.

Mr. Wickfield and Agnes

Chapter 35

Sol Eytinge Jr.

1867 Diamond Edition

Commentary:

The twelfth illustration — taking its cue from Dickens's text in Chapter 35, "Depression" — describes the relationship between Canterbury attorney Wickfield and his daughter of marriageable age. In essence, his daughter, Agnes, serves as a surrogate wife for the elderly widower in that, even from girlhood, she has managed the household and held all the keys to the house. In Eytinge's illustration she communicates her concern for her aging father's physical and mental deterioration through her facial expression and the physical support she offers him as he rises from his chair (left) in the evening in order to rest on the chesterfield after dinner. On the table, a very small glass of wine has been emptied, minimizing the reader's suspicion that the old lawyer has chosen to escape his sense of guilt in alcohol as he bends to the will of his devious and manipulative junior partner, Uriah Heep. Eytinge's Mr. Wickfield seems physically frail and mentally exhausted, as is suggested by his posture, bleary eyes, thinning hair, and balancing himself by putting his right hand on the table. The illustration is undoubtedly intended to complement the following passage on the facing page:

After dinner, Agnes sat beside him, as of old, and poured out his wine. He took what she gave him, and no more, — like a child, — and we all three sat together at a window as the evening gathered in. When it was almost dark, he lay down on a sofa, Agnes pillowing his head. . . .

Eytinge gives the pair a common facial bone structure, but distinguishes the the head of the daughter by placing it in the very centre of the composition to increase her prominence. Her father's tailcoat, waistcoat, and cravat are consistent with the fashions of the 1840s, but in contrast to the richly-textured cravat of the father Eytinge has dressed Agnes very plainly, in part to focus the reader's attention on her face. Compare the solid modelling of Eytinge's version of these characters to the lighter, more delicate lines of Phiz's in "Mr. Wickfield and his partner wait upon my Aunt" for the same chapter. Phiz's analyses of the characters of the father and daughter are somewhat superficial — the original Dickens illustrator achieves his effect (placing the concerned child and abstracted parent centre stage) in a markedly theatrical manner, setting the characters in a dramatic and narrative-pictorial context; in contrast, Eytinge studies the pair with deep conviction and psychological penetration, but offers only the empty wine glass as a contextual clue to define the moment realized. A "New Man of the Sixties," Eytinge offers an interesting commentary on the Wickfields; Phiz had dramatized their situation with reference to Uriah Heep and Betsey Trotwood to flesh out the scene that Dickens describes. One might argue that, while Eytinge's illustration is an interesting adjunct to the experience of reading the 1867 Diamond Edition of the novel, Phiz's is "indispensable to comprehensive understanding of [Dickens's] time and his texts", in this case David Copperfield, since the illustration must have profoundly shaped the serial reader's interpretation of the particular scene in the monthly instalment, in this case, the twelfth part, issued at the beginning of April, 1850.

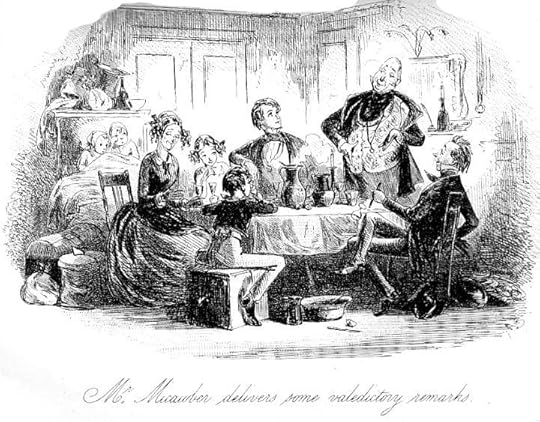

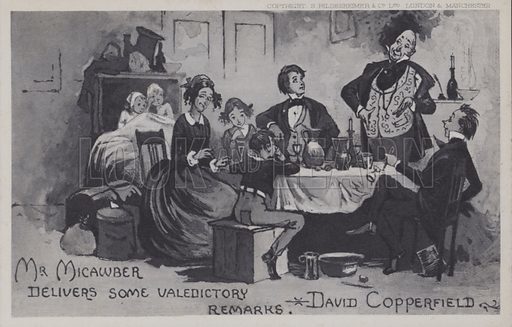

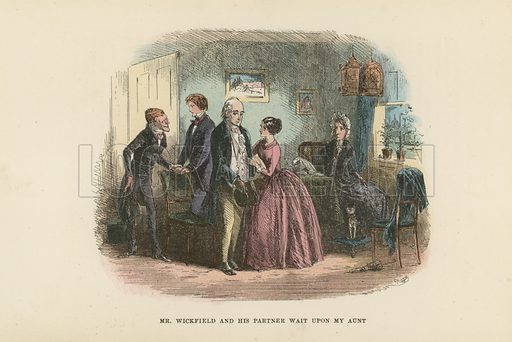

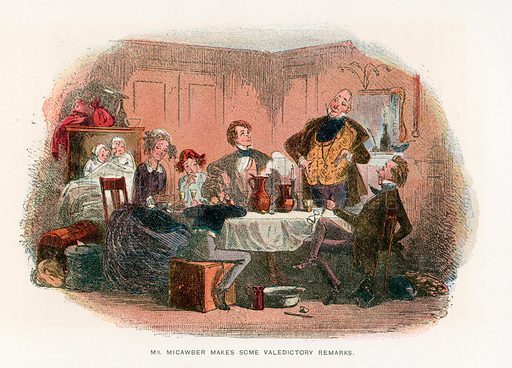

Mr. Micawber delivers some valedictory remarks

Chapter 36

Phiz

Commentary:

For the second illustration in the twelfth monthly number, which appeared in April 1850 and comprises chapters 35 through 37, Phiz prepares the reader for Micawber's joining the firm of Wickfield and Heep in Canterbury. From Micawber's posture and the empty wine glasses and tumblers, we may judge that that Phiz has realized the moment presented in the following:

"My dear Copperfield," said Mr. Micawber, rising with one of his thumbs in each of his waistcoat pockets, "the companion of youth: if I may be allowed the expression — and my esteemed friend Traddles: if I may be permitted to call him so — will allow me, on the part of Mrs. Micawber, myself, and our offspring, to thank them in the warmest and most uncompromising terms for their good wishes. It may be expected that on the eve of a migration which will consign us to a perfectly new existence," Mr. Micawber spoke as if they were going five hundred thousand miles, "I should offer a few valedictory remarks to two such friends as I see before me. But all that I have to say in this way, I have said. Whatever station in society I may attain, through the medium of the learned profession of which I am about to become an unworthy member, I shall endeavour not to disgrace, and Mrs. Micawber will be safe to adorn. Under the temporary pressure of pecuniary liabilities, contracted with a view to their immediate liquidation, but remaining unliquidated through a combination of circumstances, I have been under the necessity of assuming a garb from which my natural instincts recoil—I allude to spectacles—and possessing myself of a cognomen, to which I can establish no legitimate pretensions. All I have to say on that score is, that the cloud has passed from the dreary scene, and the God of Day is once more high upon the mountain tops. On Monday next, on the arrival of the four o’clock afternoon coach at Canterbury, my foot will be on my native heath—my name, Micawber!’"

The scene is in the sitting-room of Micawbers' temporary residence near the top of Gray's Inn Road as, under the pseudonym "Mortimer," they hide from their creditors. In preparation for their stage-coach journey on Monday, the Micawbers have packed up their meager belongings (evident in the clutter of a trunk and bags in the left-hand register of the plate). As in the text, the twins have been installed in a turn-up bedstead (left), and Micawber has prepared his signature beverage, a hot lemon punch, in a wash-hand-stand jug (there are, in fact, two of these receptacles on the table). The boy seated at the table, centre, is the twelve- or thirteen-year-old Master Micawber; his sister, looking like a miniature version of her mother in terms of her beribboned hair and physiognomy, is seated beside Mrs. Micawber, across from her brother. The focal points of the picture are the beaming Micawber, the only figure standing, and David Copperfield, centre, immediately above the larger of the two jugs. We may presume that the host had heated the alcohol, probably rum (which Micawber used to make his contribution top the "cookery" in chapter 28), in the pewter mug (down centre), and mixed it with the other ingredients in the bowl beside it. "Charles Dickens's Own Punch" in The Charles Dickens Cookbook uses the peel and the fruit of three lemons, a double handful of lump sugar, a pint of rum, and a large wine glass of brandy, set on fire in a silver spoon for three to four minutes, and added to a quart of boiling water.

The only detail in the illustration not actually described or implied in the text is Phiz's comic touch of having Traddles' empty glass fall off the table, the "bumper" already having been consumed. Uncharacteristic of this Phiz interior is the absence of paintings that support an interpretation of the scene, but then these are after all rooms rented for a short time rather than a long-term residence — and the Micawbers by now have already pawned or sold most belongings of any value, including, presumably, paintings.

Frederic G. Kitton, having inspected the original sketches that constitute the illustrator's working drawings in pencil with india-ink wash (in 1899 these were the property of the Duchess of St. Albans), notes that in the original study for this etching "certain faint lines are observable near the principal figure, indicating that he was originally delineated in a different attitude. Phiz may have originally have conceived of Micawber as proposing the toast "in due form", but chose to match his posture to his making his "valedictory remarks" in the succeeding paragraph. As in Phiz's previous images of the genial Micawber, "We are disturbed in our cookery" and "Somebody turns up" (illustrations for the tenth and sixth monthly parts respectively), the genial indigent has the familiar bald pate and alcoholic nose, but now seems more substantial a figure as he sports the sort of ostentatious, floral "D'Orsay" waistcoat favoured by young adult David Copperfield and young novelist Charles Dickens, who emulated the French aristocrat, "The Prince of Dandies," Count Alfred D'Orsay (1801-1852), whom Dickens met in 1840.

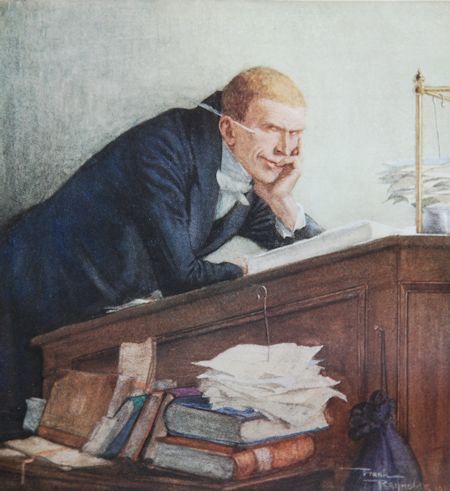

"I hardly ever take breakfast, sir," he replied, with his head thrown back in an easy chair. "I find it bores me."

Chapter 36

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

They had postponed their breakfast on my account, and we sat down to table together. We had not been seated long, when I saw an approaching arrival in Mrs. Strong’s face, before I heard any sound of it. A gentleman on horseback came to the gate, and leading his horse into the little court, with the bridle over his arm, as if he were quite at home, tied him to a ring in the empty coach-house wall, and came into the breakfast parlour, whip in hand. It was Mr. Jack Maldon; and Mr. Jack Maldon was not at all improved by India, I thought. I was in a state of ferocious virtue, however, as to young men who were not cutting down trees in the forest of difficulty; and my impression must be received with due allowance.

‘Mr. Jack!’ said the Doctor. ‘Copperfield!’

Mr. Jack Maldon shook hands with me; but not very warmly, I believed; and with an air of languid patronage, at which I secretly took great umbrage. But his languor altogether was quite a wonderful sight; except when he addressed himself to his cousin Annie. ‘Have you breakfasted this morning, Mr. Jack?’ said the Doctor.

‘I hardly ever take breakfast, sir,’ he replied, with his head thrown back in an easy-chair. ‘I find it bores me.’

‘Is there any news today?’ inquired the Doctor.

‘Nothing at all, sir,’ replied Mr. Maldon. ‘There’s an account about the people being hungry and discontented down in the North, but they are always being hungry and discontented somewhere.’

The Doctor looked grave, and said, as though he wished to change the subject, ‘Then there’s no news at all; and no news, they say, is good news.’

‘There’s a long statement in the papers, sir, about a murder,’ observed Mr. Maldon. ‘But somebody is always being murdered, and I didn’t read it.’

Here is that original drawing talked about above. I see nothing in it they are talking about, but that isn't surprising, Peter will know what they are talking about.

Mr Micawber delivers some valedictory remarks, David Copperfield. One of a set of postcards depicting scenes from the novels of Charles Dickens, early 20th century.

Jantine wrote: "Oh and my first thought about the whole Mr. Jorkis-thing was 'Oh, wow, he does exist!'

Me too! I was certain he was made up by Mr. Spenlow. I even read the book before and don't remember the guy. :-)

Me too! I was certain he was made up by Mr. Spenlow. I even read the book before and don't remember the guy. :-)

Jantine wrote: "Seeing how she took even this, imagine how she would have reacted to 'learn how to cook decent but cheap meals.."

That brings to mind a sister story. My sister can't cook. She couldn't cook when we were kids and she can't now when we are in our 50s. She hates it, and she is terrible at it. But once in a while she gives it a try, sort of. One of these times had her call me with this "Kim, I'm going to try to make some corn for supper, do I have to take it out of the can before I microwave it?" Yes, you do. Another time we were having a picnic and she says "Guess what, I made potato salad!", yes, now if only she would have called and asked me whether to cook the potatoes first, because raw potato salad is a strange thing to try to eat. Her daughter used to tell me my scrambled eggs were much better than her mom's because I take the shell out of mine, which led me to call her and tell her to break the egg into a bowl and throw away the shells before you even turn on the stove. I wonder if Dora's cookbook would have helped.

That brings to mind a sister story. My sister can't cook. She couldn't cook when we were kids and she can't now when we are in our 50s. She hates it, and she is terrible at it. But once in a while she gives it a try, sort of. One of these times had her call me with this "Kim, I'm going to try to make some corn for supper, do I have to take it out of the can before I microwave it?" Yes, you do. Another time we were having a picnic and she says "Guess what, I made potato salad!", yes, now if only she would have called and asked me whether to cook the potatoes first, because raw potato salad is a strange thing to try to eat. Her daughter used to tell me my scrambled eggs were much better than her mom's because I take the shell out of mine, which led me to call her and tell her to break the egg into a bowl and throw away the shells before you even turn on the stove. I wonder if Dora's cookbook would have helped.

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "The female character in Dickens I really fell in love with was Dolly Varden, and Kim always tried to talk me out of it ;-)

Yuk. I rolled my eyes just seeing her name mentioned by ..."

Kim,

Don't forget that Dolly changes a lot in the course of the novel. I like that development more than being faced with a complete saint at the beginning of a story and never seeing her change a bit.

Yuk. I rolled my eyes just seeing her name mentioned by ..."

Kim,

Don't forget that Dolly changes a lot in the course of the novel. I like that development more than being faced with a complete saint at the beginning of a story and never seeing her change a bit.

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I am beginning to wonder whether those writhing movements of Uriah’s are not a symptom of some kind of nervous disease that Dickens might have observed in one of his contemporaries..."

I am sure that Uriah Heep's mannerisms are pathological. By the way, in one of our earlier discussions of the novel someone found out that Heep was partly modelled on the Danish writer Hans Christian Anderson. Was that you, Kim?

I am sure that Uriah Heep's mannerisms are pathological. By the way, in one of our earlier discussions of the novel someone found out that Heep was partly modelled on the Danish writer Hans Christian Anderson. Was that you, Kim?

Kim wrote: "Jantine wrote: "Seeing how she took even this, imagine how she would have reacted to 'learn how to cook decent but cheap meals.."

That brings to mind a sister story. My sister can't cook. She coul..."

Oh dear, had Dickens known your sister, he would surely have put her into one of his stories, maybe as an old family cook?

That brings to mind a sister story. My sister can't cook. She coul..."

Oh dear, had Dickens known your sister, he would surely have put her into one of his stories, maybe as an old family cook?

Kim wrote: "

Mr. Wickfield and his partner wait upon my Aunt.

Chapter 35

Phiz

Commentary:

For the first illustration in the twelfth monthly number, which was issued in April 1850 and comprises chapters 3..."

Kim

Every week’s illustrations are a Christmas gift. I especially appreciate the zoom in detail of the picture on the wall and the view seen outside the window. We have discussed the nature of the pictures that appear on the walls of Browne’s illustrations before. Here we read an analysis of what Browne did in this illustration. From my point of view I do think that Browne very deliberately placed pictures and created little telling incidentals in his work. While not in the forefront of the work, these telling details significantly add to the narrative of each illustration.

I have teased before that we are coming up to a Phiz illustration for this novel that I hope will illustrate clearly the subtle but telling pictorial commentary of many Browne illustrations. It’s coming soon :-)

Mr. Wickfield and his partner wait upon my Aunt.

Chapter 35

Phiz

Commentary:

For the first illustration in the twelfth monthly number, which was issued in April 1850 and comprises chapters 3..."

Kim

Every week’s illustrations are a Christmas gift. I especially appreciate the zoom in detail of the picture on the wall and the view seen outside the window. We have discussed the nature of the pictures that appear on the walls of Browne’s illustrations before. Here we read an analysis of what Browne did in this illustration. From my point of view I do think that Browne very deliberately placed pictures and created little telling incidentals in his work. While not in the forefront of the work, these telling details significantly add to the narrative of each illustration.

I have teased before that we are coming up to a Phiz illustration for this novel that I hope will illustrate clearly the subtle but telling pictorial commentary of many Browne illustrations. It’s coming soon :-)

Kim wrote: "

Mr. Micawber delivers some valedictory remarks

Chapter 36

Phiz

Commentary:

For the second illustration in the twelfth monthly number, which appeared in April 1850 and comprises chapters 35 th..."

Lucky Kitton for having the opportunity to work with so many of the original illustrations.

In the two original illustrations that Kim has provided us we can see, perhaps even more clearly, the intention and the narrative that finally appeared in the novel. When the picture was etched and printed some of the subtle shading and differences in emphasis are often muted. The colourized versions also offer the viewer/reader a more distinct representation because of the colourization and shading that can be represented by many colours.

Still, the illustrations that appear in the novels are delightful. They speak of a time long gone where the illustrator and the writer collaborated in such a manner that the reader both read the letterpress and the illustration. Such a rich experience.

There is an awkwardness of the steel engraving’s method of placement in the parts, and subsequently the novel, because of the nature of the printing process. The ability to read both the letterpress and the illustration at the same time is compromised. Nevertheless, to me anyway, the Browne illustrations are wonderful.

Mr. Micawber delivers some valedictory remarks

Chapter 36

Phiz

Commentary:

For the second illustration in the twelfth monthly number, which appeared in April 1850 and comprises chapters 35 th..."

Lucky Kitton for having the opportunity to work with so many of the original illustrations.

In the two original illustrations that Kim has provided us we can see, perhaps even more clearly, the intention and the narrative that finally appeared in the novel. When the picture was etched and printed some of the subtle shading and differences in emphasis are often muted. The colourized versions also offer the viewer/reader a more distinct representation because of the colourization and shading that can be represented by many colours.

Still, the illustrations that appear in the novels are delightful. They speak of a time long gone where the illustrator and the writer collaborated in such a manner that the reader both read the letterpress and the illustration. Such a rich experience.

There is an awkwardness of the steel engraving’s method of placement in the parts, and subsequently the novel, because of the nature of the printing process. The ability to read both the letterpress and the illustration at the same time is compromised. Nevertheless, to me anyway, the Browne illustrations are wonderful.

Tristram wrote: "By the way, in one of our earlier discussions of the novel someone found out that Heep was partly modelled on the Danish writer Hans Christian Anderson. Was that you, Kim?

I don't know if it was me, but here it is:

Much of David Copperfield is autobiographical, and some scholars believe Heep's mannerisms and physical attributes to be based on Hans Christian Andersen, whom Dickens met shortly before writing the novel.

In June 1847, Andersen paid his first visit to England and he enjoyed a triumphal social success during this summer. The Countess of Blessington invited him to her parties where intellectual people would meet, and it was at one of such parties where he met Charles Dickens for the first time. They shook hands and walked to the veranda, which Andersen wrote about in his diary: "We were on the veranda, and I was so happy to see and speak to England's now-living writer whom I do love the most."

The two authors respected each other's work and as writers, they shared something important in common: depictions of the poor and the underclass who often had difficult lives affected both by the Industrial Revolution and by abject poverty. In the Victorian era there was a growing sympathy for children and an idealization of the innocence of childhood.

Ten years later, Andersen visited England again, primarily to meet Dickens. He extended the planned brief visit to Dickens' home at Gads Hill Place into a five-week stay, much to the distress of Dickens' family. After Andersen was told to leave, Dickens gradually stopped all correspondence between them, this to the great disappointment and confusion of Andersen, who had quite enjoyed the visit and could never understand why his letters went unanswered.

Uriah Heep's schemes and behaviour are more likely based on Thomas Powell, employee of Thomas Chapman, a friend of Dickens. Powell "ingratiated himself into the Dickens household" and was discovered to be a forger and a thief, having embezzled £10,000 from his employer. He later attacked Dickens in pamphlets, calling particular attention to Dickens' social class and background.