The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Bleak House

>

Bleak House chapters 5-7

Chapter 6

Quite at Home

Well, my friends, this is another very busy chapter. I am going to focus on the characters, new and old, and what I find interesting in structural details rather than simply follow the chronological narrative.

Setting

So far in the novel the weather and overall setting has been, well, bleak. In chapter six the first words are “The day had brightened very much, and still brightened as we went westward.” Take a look at the following paragraphs where words such as “many-coloured flowers,” clear-sounding bells,” beautiful,” “delightful” and others breath a new mood into the narrative. Ada, Richard, and Esther meet a man who delivers to each a short note from John Jarndyce which is warm and welcoming. As they approach Bleak House it reveals itself to be “beaming brightly.” The grit, dirt and somber greyness of London has been replaced with a totally new tone and mood. Will this be a harbinger of what is to be discovered within its walls?

John Jarndyce

He greets our travellers with “a bright, hospitable voice” and kisses each “in a fatherly way.” He sits them by his hearth and encourages Richard to warm himself by the fire. Esther notes that he is “nearer sixty than fifty” and was right, healthy, and robust.” Jarndyce is upset when he hears the state of the Jellyby house. Ada recounts to Jarndyce how kind and attentive Esther was to the Jellyby children. Dickens gives us a “tell” as to his character. Frequently, a Dickens character will exhibit a phrase, physical trait or action that will define their personality. For Jarndyce, it will be his feeling that the wind in the east. Whenever this happens, something is upsetting him. Jarndyce then invites Ada, Richard, and Esther to “see your home.” And so our three young characters learn that they finally have a place to call home.

Bleak House

It is a “delightfully irregular house” with many “little halls and passages” that has a “charming little sitting-room,” a “flower-garden” and even “a hollow window-seat.” The name Bleak House” clearly is not emblematic of its owner or its interior. Think, for comparison, the Jellyby house.

Harold Skimpole

In many novels by Dickens we find adult characters who are, in many different ways, portrayed as being very childlike. Some, like Mr Dick in DC are endearing. Others, like Mr Micawber, I find annoying. In this chapter we meet Mr Harold Skimpole. Skimpole is childish to the extreme. He has no idea of responsibility, duty, or fairness. Everything is about him and his own pleasures, his needs, and view of life. Dickens describes him as ”having in all respects, of [being] a damaged young man, [rather] than a well-preserved elderly one.” He has no idea of time or money. Skimpole defines himself as “a child” and “gay and innocent.” In this chapter Skimpole is arrested for debt and Richard and Esther pay the debt collector from Coavinses. Jarndyce, upon hearing of the Skimpole situation, tells Richard and Esther that Skimpole will simply fall into another scrape next week. Jarndyce again feels an east wind coming his way. Indeed, he says “It’ll blow a gale in the course of the night.” Jarndyce asks Ada, Richard, and Esther to never help Skimpole out financially again.

Richard and Ada

Slowly, and somewhat obviously, Dickens nudges us to note a blossoming love between Ada and Richard.

Esther

While Esther has recounted to us how she feels inadequate and somewhat unworthy, it seems to me that Dickens is portraying her in a more positive manner in this chapter. He has Ada and Richard praise her, we see John Jarndyce give her the keys to the household, and we see how the narrative is becoming focussed on her. What’s your opinion?

Thoughts

Once again, in a different manner, we see how money and debt invades this novel. Skimpole is unable to manage his finances, Richard and Esther drain their savings to help him, and the connection between Jellyby and Jarndyce and how money is allocated and spent is present. What other incidences of money and its constant presence can be found in this chapter?

This was a long, complicated chapter to read and unravel. As always, what were your thoughts and impressions?

The character of Skimpole dominates this chapter in many ways. To this point in time, do you think he is as innocent and naive as he presents himself or do you suspect something deeper and darker about his personality?

Quite at Home

Well, my friends, this is another very busy chapter. I am going to focus on the characters, new and old, and what I find interesting in structural details rather than simply follow the chronological narrative.

Setting

So far in the novel the weather and overall setting has been, well, bleak. In chapter six the first words are “The day had brightened very much, and still brightened as we went westward.” Take a look at the following paragraphs where words such as “many-coloured flowers,” clear-sounding bells,” beautiful,” “delightful” and others breath a new mood into the narrative. Ada, Richard, and Esther meet a man who delivers to each a short note from John Jarndyce which is warm and welcoming. As they approach Bleak House it reveals itself to be “beaming brightly.” The grit, dirt and somber greyness of London has been replaced with a totally new tone and mood. Will this be a harbinger of what is to be discovered within its walls?

John Jarndyce

He greets our travellers with “a bright, hospitable voice” and kisses each “in a fatherly way.” He sits them by his hearth and encourages Richard to warm himself by the fire. Esther notes that he is “nearer sixty than fifty” and was right, healthy, and robust.” Jarndyce is upset when he hears the state of the Jellyby house. Ada recounts to Jarndyce how kind and attentive Esther was to the Jellyby children. Dickens gives us a “tell” as to his character. Frequently, a Dickens character will exhibit a phrase, physical trait or action that will define their personality. For Jarndyce, it will be his feeling that the wind in the east. Whenever this happens, something is upsetting him. Jarndyce then invites Ada, Richard, and Esther to “see your home.” And so our three young characters learn that they finally have a place to call home.

Bleak House

It is a “delightfully irregular house” with many “little halls and passages” that has a “charming little sitting-room,” a “flower-garden” and even “a hollow window-seat.” The name Bleak House” clearly is not emblematic of its owner or its interior. Think, for comparison, the Jellyby house.

Harold Skimpole

In many novels by Dickens we find adult characters who are, in many different ways, portrayed as being very childlike. Some, like Mr Dick in DC are endearing. Others, like Mr Micawber, I find annoying. In this chapter we meet Mr Harold Skimpole. Skimpole is childish to the extreme. He has no idea of responsibility, duty, or fairness. Everything is about him and his own pleasures, his needs, and view of life. Dickens describes him as ”having in all respects, of [being] a damaged young man, [rather] than a well-preserved elderly one.” He has no idea of time or money. Skimpole defines himself as “a child” and “gay and innocent.” In this chapter Skimpole is arrested for debt and Richard and Esther pay the debt collector from Coavinses. Jarndyce, upon hearing of the Skimpole situation, tells Richard and Esther that Skimpole will simply fall into another scrape next week. Jarndyce again feels an east wind coming his way. Indeed, he says “It’ll blow a gale in the course of the night.” Jarndyce asks Ada, Richard, and Esther to never help Skimpole out financially again.

Richard and Ada

Slowly, and somewhat obviously, Dickens nudges us to note a blossoming love between Ada and Richard.

Esther

While Esther has recounted to us how she feels inadequate and somewhat unworthy, it seems to me that Dickens is portraying her in a more positive manner in this chapter. He has Ada and Richard praise her, we see John Jarndyce give her the keys to the household, and we see how the narrative is becoming focussed on her. What’s your opinion?

Thoughts

Once again, in a different manner, we see how money and debt invades this novel. Skimpole is unable to manage his finances, Richard and Esther drain their savings to help him, and the connection between Jellyby and Jarndyce and how money is allocated and spent is present. What other incidences of money and its constant presence can be found in this chapter?

This was a long, complicated chapter to read and unravel. As always, what were your thoughts and impressions?

The character of Skimpole dominates this chapter in many ways. To this point in time, do you think he is as innocent and naive as he presents himself or do you suspect something deeper and darker about his personality?

Chapter 7

The Ghost’s Walk

I love a good mystery story, and with Bleak House we have one. The epigraph sets the chapter up perfectly. Naturally, Dickens will just give us a peek into what will happen; nevertheless, it is a good peek so let’s have a look.

This chapter opens with a closer look at Chesney Wold which is the home of Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock. Chesney Wold is framed by Dickens as a clear contrast to Bleak House. While our first visit to Bleak House last chapter revealed that home to be one of warmth, friendship, and love, in contrast, Chesney Wold is portrayed as being more like London. It appears as a dreary place, one where there seems to be a constant rain. It is a place that has a feeling of discontent.

The old housekeeper of Chesney Wold is a lady by the name of Mrs Rouncewell. She appears to be a fixture of Chesney Wold, as firm, as steady, and as historical as the place itself. We learn that she has two children, the younger one named George who “ran wild” and became a soldier and never came back. Her second son showed early promise in mechanics. Sir Leicester saw this son as pursuing a needless occupation. Wrong! This son has made a successful career of embracing the future and is successful. Clearly, Dickens wants us to see that Sir Leicester and Mrs Rouncewell are rooted in the past. Mrs Rouncewell is entertaining the grandson of the more successful son who has followed in his father’s footsteps. Mrs Rouncewell admits that “there may be a world beyond Chesney Wold that I don’t understand.” Meanwhile, her grandson appears to be interested in a maid who works under Mrs Rouncewell. Let’s keep that idea in mind for the present time.

Thoughts

There is a clear contrast between Bleak House and Chesney Wold. It is always a good idea to pause and look at any residence in Dickens as the place and its inhabitants most often have a direct correlation. What about Chesney Wold was most remarkable to you?

What did you make of Mrs Rouncewell?

On this rainy day a carriage appears at Chesney Wold with two lawyers who, being in the neighbourhood, wondered if they could have a tour through Chesney Wold. One of the lawyer’s names is Guppy. We have met Guppy very briefly in an earlier chapter. It was not uncommon for many of the grand homes and estates to open their doors to the public for a tour. Remember Elizabeth Bennett’s tour of Darcy’s home in Pride and Prejudice? During this tour Guppy spots a portrait of Lady Dedlock, a perfect likeness we are told, and the portrait fascinated him. Guppy is absolutely certain he has seen the likeness of Lady Dedlock before. The touring group comes to the place called The Ghost’s Walk. Guppy wants to know if there is any link or relationship between the portrait of Lady Dedlock and the story of The Ghost’s Walk. Before we learn about The Ghost’s Walk, let's pause for a moment. Dickens, as we know, loves coincidences. If we recall where we briefly met Mr Guppy before and listen carefully to the story of The Ghost’s Walk, I wonder what your thoughts are?

Briefly, the story of The Ghost’s Walk is that in olden times at Chesney Wold the lady of Chesney Wold had a great difference in opinion about the politics of her husband Sir Morbury Dedlock, who was an ardent supporter of King Charles. This rift was so great that it is said she maimed the horses of her husband. One night her husband caught her in the act of maiming his horses, they fought, she was lamed, her health declined, and she began to pine away. She never complained and never again spoke to her husband until one night, as she was getting some exercise, she dropped to the pavement. She refused help and said that “she will die where I have walked. And I will walk here though I am in my grave. I will walk here, until the pride of this house is humbled. And when calamity, or when disgrace is coming to it, let the Dedlock’s listen for my step!” That is the origin of the name Ghost’s Walk and Mrs Rouncewell claims that on occasion the steps are still heard at night. Mrs Rouncewell then instructs her son to set the large grandfather clock in the room and asks her grandson if he can hear a sound upon the terrace. He says he can. And so the chapter ends, with the alleged sounds of a person walking along The Ghost Walk being marked by time.

Ghosts and time. We need to remember this image. Ghosts are from the past. What will happen if a ghost makes an appearance in the present? Perhaps we need only look to A Christmas Carol to recall how Dickens has used ghosts in a story before.

Thoughts

Wow! What a story of The Ghost’s Walk. Murder, revenge, the destruction of a family and its centuries old name. Dickens has written an entire chapter around this family’s ghost story. Did you enjoy the story? How might the story be linked to the novel?

One other mystery in the chapter revolves around Mr Guppy. Where have we seen him before? Why is he so fascinated with the portrait of Lady Dedlock? Do you think Dickens is creating a major mystery in this chapter or presenting us with red herrings?

Did you find any other mysteries in this chapter? This novel is packed with mysteries.

The Ghost’s Walk

I love a good mystery story, and with Bleak House we have one. The epigraph sets the chapter up perfectly. Naturally, Dickens will just give us a peek into what will happen; nevertheless, it is a good peek so let’s have a look.

This chapter opens with a closer look at Chesney Wold which is the home of Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock. Chesney Wold is framed by Dickens as a clear contrast to Bleak House. While our first visit to Bleak House last chapter revealed that home to be one of warmth, friendship, and love, in contrast, Chesney Wold is portrayed as being more like London. It appears as a dreary place, one where there seems to be a constant rain. It is a place that has a feeling of discontent.

The old housekeeper of Chesney Wold is a lady by the name of Mrs Rouncewell. She appears to be a fixture of Chesney Wold, as firm, as steady, and as historical as the place itself. We learn that she has two children, the younger one named George who “ran wild” and became a soldier and never came back. Her second son showed early promise in mechanics. Sir Leicester saw this son as pursuing a needless occupation. Wrong! This son has made a successful career of embracing the future and is successful. Clearly, Dickens wants us to see that Sir Leicester and Mrs Rouncewell are rooted in the past. Mrs Rouncewell is entertaining the grandson of the more successful son who has followed in his father’s footsteps. Mrs Rouncewell admits that “there may be a world beyond Chesney Wold that I don’t understand.” Meanwhile, her grandson appears to be interested in a maid who works under Mrs Rouncewell. Let’s keep that idea in mind for the present time.

Thoughts

There is a clear contrast between Bleak House and Chesney Wold. It is always a good idea to pause and look at any residence in Dickens as the place and its inhabitants most often have a direct correlation. What about Chesney Wold was most remarkable to you?

What did you make of Mrs Rouncewell?

On this rainy day a carriage appears at Chesney Wold with two lawyers who, being in the neighbourhood, wondered if they could have a tour through Chesney Wold. One of the lawyer’s names is Guppy. We have met Guppy very briefly in an earlier chapter. It was not uncommon for many of the grand homes and estates to open their doors to the public for a tour. Remember Elizabeth Bennett’s tour of Darcy’s home in Pride and Prejudice? During this tour Guppy spots a portrait of Lady Dedlock, a perfect likeness we are told, and the portrait fascinated him. Guppy is absolutely certain he has seen the likeness of Lady Dedlock before. The touring group comes to the place called The Ghost’s Walk. Guppy wants to know if there is any link or relationship between the portrait of Lady Dedlock and the story of The Ghost’s Walk. Before we learn about The Ghost’s Walk, let's pause for a moment. Dickens, as we know, loves coincidences. If we recall where we briefly met Mr Guppy before and listen carefully to the story of The Ghost’s Walk, I wonder what your thoughts are?

Briefly, the story of The Ghost’s Walk is that in olden times at Chesney Wold the lady of Chesney Wold had a great difference in opinion about the politics of her husband Sir Morbury Dedlock, who was an ardent supporter of King Charles. This rift was so great that it is said she maimed the horses of her husband. One night her husband caught her in the act of maiming his horses, they fought, she was lamed, her health declined, and she began to pine away. She never complained and never again spoke to her husband until one night, as she was getting some exercise, she dropped to the pavement. She refused help and said that “she will die where I have walked. And I will walk here though I am in my grave. I will walk here, until the pride of this house is humbled. And when calamity, or when disgrace is coming to it, let the Dedlock’s listen for my step!” That is the origin of the name Ghost’s Walk and Mrs Rouncewell claims that on occasion the steps are still heard at night. Mrs Rouncewell then instructs her son to set the large grandfather clock in the room and asks her grandson if he can hear a sound upon the terrace. He says he can. And so the chapter ends, with the alleged sounds of a person walking along The Ghost Walk being marked by time.

Ghosts and time. We need to remember this image. Ghosts are from the past. What will happen if a ghost makes an appearance in the present? Perhaps we need only look to A Christmas Carol to recall how Dickens has used ghosts in a story before.

Thoughts

Wow! What a story of The Ghost’s Walk. Murder, revenge, the destruction of a family and its centuries old name. Dickens has written an entire chapter around this family’s ghost story. Did you enjoy the story? How might the story be linked to the novel?

One other mystery in the chapter revolves around Mr Guppy. Where have we seen him before? Why is he so fascinated with the portrait of Lady Dedlock? Do you think Dickens is creating a major mystery in this chapter or presenting us with red herrings?

Did you find any other mysteries in this chapter? This novel is packed with mysteries.

Chapter 5

Chapter 5Peter wrote: "Do you often find yourself attached to a minor character in a novel? ..."

It's almost exclusively the minor characters in Dickens novels to whom I find myself attached. They're so much more interesting than the main characters.

Peter wrote: "What is similar between the Court of Chancery and Krook’s warehouse? What comparison do you think Dickens wanted his readers to make?..."

The word "quagmire" is what always comes to my mind. I think your comparison was right on target. Krook says,

"And I can't abear to part with anything I once lay hold of (or so my neighbours think, but what do they know?) or to alter anything, or to have any sweeping, nor scouring, nor cleaning, nor repairing going on about me. That's the way I've got the ill name of Chancery."

I think of those shows about hoarders. What a horrible place this must have been! That it's compared to Chancery really leaves no question about Dickens' opinion of the legal system.

Was anyone else creeped out to hear Krook say he had three sacks of women's hair tucked away? Anyone have an annotated version to give us some insight? I'd think women in need of money would go directly to a wig maker. Is he getting it from corpses?! Ew!

Would it be an unforgivable pun to say that Miss Flite is a hoot? I've looked up the life expectancy of songbirds. In the wild, it's only about 2 years. In 2021, birds in captivity can live up to 7 years, but I'm sure in Victorian London they didn't get the nutrition, vet care, and clean air that pet birds today enjoy. If the Jarndyce case is interminable, Miss Flite will continue to lose a lot of feathered friends. What an odd bird she is!

Peter wrote: "Does this chapter add anything to our understanding of [Esther]? ..."

I'd like to say it does, but based on our previous discussion about unreliable narrators, I'm no longer sure that we can trust it. :-( But she's representing herself as diplomatic, kind, and responsible. She handled Caddy's initial meltdown with great sensitivity, and stayed behind with Krook, despite probably wanting to run from the place.

Question: Krook mentioned the name Barbary in conjunction with the court case, yet there was no surprise or recognition from Esther to hear her Aunt's name mentioned. Did I miss something?

It is said that Dickens made a mistake there and it should have been another name, because before that there was also distinctly said that Esther had no relations/interest in the case. That wouldn't have been said if the name her aunt went by was connected to it, and yet it passes Krook's lips as a name connected to Jarndyce and Jarndyce. If it should have been another name, it would explain why Esther doesn't react - because she didn't know the name it would have been. I'm not sure if I believe that though, because it's not very Dickens to make a mistake like that.

Perhaps she never learned her aunt's name, having to always call her aunt? Perhaps the school wrote to 'the person in care of miss Summerson', Mrs. Racheal only called her ma'am, etc.? Then she only heard it once, years and years ago, in a situation where she was pulled from everything she knew etc.

Or she did recognize it and react to it, but conveniently left that out. Or the name was not mentioned, but she put it in for her story to point at something that might still come. Oh the joy of unreliable/first person characters ...

Perhaps she never learned her aunt's name, having to always call her aunt? Perhaps the school wrote to 'the person in care of miss Summerson', Mrs. Racheal only called her ma'am, etc.? Then she only heard it once, years and years ago, in a situation where she was pulled from everything she knew etc.

Or she did recognize it and react to it, but conveniently left that out. Or the name was not mentioned, but she put it in for her story to point at something that might still come. Oh the joy of unreliable/first person characters ...

Mary Lou wrote: "Chapter 5

Peter wrote: "Do you often find yourself attached to a minor character in a novel? ..."

It's almost exclusively the minor characters in Dickens novels to whom I find myself attached. Th..."

Hi Mary Lou

As always, I look forward to your comments, insights and wry humour. Also, you are most frequently an early -if not first- commentator. It is always good to know someone is out there ready to respond and to confirm that my posting did go out. I will live in fear of computers forever.

Yes, Krook’s place is rather disgusting. I’m not too sure about the hair in the sacks. Knowing what else is in his store my thought would be that the hair does not come from any reputable place (or head). A corpse of a poor person or from the head of a live but poor person would be my guess.

Ah, Miss Flite. Bring on the puns! I do know that in the 19C there was a rather large and active trade in caged birds in London. It seems that birds were the pet of choice for the poor or people who had small residences. While Esther buried her doll before she came to London, she did bring her pet bird. We will find a reference to the buried doll in an upcoming chapter. As for the birds, there may be flocks of them in our future reading.

As to narrators ... their reliability or unreliability will be something to keep our eyes on. I have recently listened to a lecture that concerned narrators. In a nutshell, it said that there are three people telling the story in a novel. They are the author, the narrator, and the character. Different weightings and emphasis naturally among novelists, and even with a single novel, or even a single chapter of course, but one needs to keep aware of what’s going on the page and whose voice it is telling the narrative.

Yes. The Barbary name did slip by quickly. Good catch! I’m finding in this novel other seemingly inconsequential comments or words that are very important. It helps, of course, if one has read the novel before, but for someone reading the novel for the first time some information may be missed. I’m trying to point out some of these seemingly glossed over words or phrases during the writing of the novel without doing too much of a spoiler.

Peter wrote: "Do you often find yourself attached to a minor character in a novel? ..."

It's almost exclusively the minor characters in Dickens novels to whom I find myself attached. Th..."

Hi Mary Lou

As always, I look forward to your comments, insights and wry humour. Also, you are most frequently an early -if not first- commentator. It is always good to know someone is out there ready to respond and to confirm that my posting did go out. I will live in fear of computers forever.

Yes, Krook’s place is rather disgusting. I’m not too sure about the hair in the sacks. Knowing what else is in his store my thought would be that the hair does not come from any reputable place (or head). A corpse of a poor person or from the head of a live but poor person would be my guess.

Ah, Miss Flite. Bring on the puns! I do know that in the 19C there was a rather large and active trade in caged birds in London. It seems that birds were the pet of choice for the poor or people who had small residences. While Esther buried her doll before she came to London, she did bring her pet bird. We will find a reference to the buried doll in an upcoming chapter. As for the birds, there may be flocks of them in our future reading.

As to narrators ... their reliability or unreliability will be something to keep our eyes on. I have recently listened to a lecture that concerned narrators. In a nutshell, it said that there are three people telling the story in a novel. They are the author, the narrator, and the character. Different weightings and emphasis naturally among novelists, and even with a single novel, or even a single chapter of course, but one needs to keep aware of what’s going on the page and whose voice it is telling the narrative.

Yes. The Barbary name did slip by quickly. Good catch! I’m finding in this novel other seemingly inconsequential comments or words that are very important. It helps, of course, if one has read the novel before, but for someone reading the novel for the first time some information may be missed. I’m trying to point out some of these seemingly glossed over words or phrases during the writing of the novel without doing too much of a spoiler.

Jantine wrote: "It is said that Dickens made a mistake there and it should have been another name, because before that there was also distinctly said that Esther had no relations/interest in the case. That wouldn'..."

Hi Jantine

Yes. There are several possible answers in regard to the mention of the word Barbary. There are several loose filaments floating around in these initial chapters, certainly more than any other novel we have read so far. I continue to see this novel as Dickens’s foremost mystery novel.

Hi Jantine

Yes. There are several possible answers in regard to the mention of the word Barbary. There are several loose filaments floating around in these initial chapters, certainly more than any other novel we have read so far. I continue to see this novel as Dickens’s foremost mystery novel.

Chapter 6

Chapter 6I just loved the first part of this chapter - finally meeting John Jarndyce and touring Bleak House. It was a delight. Too bad Dickens didn't end it there and give Skimpole his own chapter.

Jarndyce is a bit of a riddle, isn't he? So self-conscious about attention being drawn to his good deeds. One might wonder why he doesn't just remain anonymous to his beneficiaries. Hmm... But he seems like a good and kind man, if a bit gullible. Hopefully he has the income to stay afloat despite those around him who would take advantage. I've always enjoyed his metaphorical forecasts, and sometimes find myself thinking the wind is in the east on a challenging day.

I tried to imagine Bleak House as Esther described all the nooks and crannies and three stairs up and two stairs down.... I even went online to see if some Dickens loving architect had tried to map out the floor plan. Alas, no. But it sounds like just the sort of home I'd love. Open-concept floor plans? Bah!

Esther sees being given the housekeeper's keys an honor. This additional duty was not spelled out prior to her accepting the position as Ada's companion, and I daresay most people today would cry foul. But I suppose Esther is so grateful, having this responsibility seems like a small price to pay. It does, though, show Jarndyce's trust in her, which makes me think he's been following her quite closely for some time. The shared coach was not a coincidence, I think, but a way for Jarndyce to see for himself what type of girl he was sponsoring. Was having a companion for Ada in his plans all this time? Or does he help lots of children, and Esther just stuck out as the best one for this job?

Skimpole. He showed his hand for me when he said his purpose was to make Jarndyce (and then Richard and Esther) feel good about themselves by helping him. No child would have come up with that logic. Interesting that Richard called for Esther to help pay the debt and not John or Ada.

What do you think of Coavinses? And how is that pronounced - co-ah-VIN-sees? CO-vin-sehs?

Thanks for your kind words, Peter. When I'm on track with the reading schedule I like to respond promptly for two reasons. First, I just enjoy the discussion so much and really look forward to seeing what you, Kim, and Tristram found to pique your interest. And if I read ahead, the details of this week's chapters will start to fade, so it's helpful to get my thoughts put down quickly, and then I can get started on the next installment.

Chapter 7

Chapter 7Mrs. Rouncewell's telling of the tale of the Ghost Walk seems unlike so many other stories within stories that we see in Dickens novels. Pickwick comes to mind. I'm trying to work out why that is. First, I guess, is that it's being told about a home and family that seems to be prominent in this novel, and it's being told by a character that has been fleshed out and has deep connections. In other instances these tales seem to be told by and about characters who aren't so integral to the plot. When I hear Mrs. Rouncewell tell the story of the Ghost Walk, it feels like foreshadowing, whereas others feel more like filler. Enjoyable filler in many cases, but filler, nevertheless. There may be tenuous connections in the others, but already the story of the Ghost Walk has connections with our setting, this prominent family, and - if we pay heed to Peter's focus on the clock, as well as the curse uttered by the early Lady Dedlock - the Dedlock's future. I quite enjoyed it, and look forward to seeing how it fits in to the plot going forward.

Peter wrote, "...her husband caught her in the act of maiming his horses, they fought, she was lamed..."

Karma. Not sorry.

I like Mrs. Rouncewell. Here she is, enjoying a visit with her grandson, and some cocky law clerk comes knocking at the door, name-dropping, and wanting a tour. Poor woman can't even enjoy a cuppa without being interrupted. I've never understood the idea of expecting tours of someone's home just because you're in the neighborhood and want to snoop. Seems like a good way to case the joint. I was particularly surprised to see that they not only toured the main rooms of the house, but also Lady Dedlock's private quarters. How invasive! Even at Graceland they don't let you upstairs, and Elvis has been dead for decades.

By the way, I don't have the book in front of me, but I believe we first saw Guppy when Esther, Ada, and Richard originally met, and Guppy, as a representative of Kenge and Carboy's, was there to escort them to Chancery, wasn't he?

Mary Lou wrote: "Chapter 7

Mrs. Rouncewell's telling of the tale of the Ghost Walk seems unlike so many other stories within stories that we see in Dickens novels. Pickwick comes to mind. I'm trying to work out wh..."

Mary Lou

Good memory. Yes, that is the first time Guppy made an appearance.

It won’t be the last.:-)

By the way, I took an admittedly quick look through the biography of Catherine Dickens and then a quick Google search for poems by Dickens. He wrote more than I thought but I didn’t find any directed obviously or specifically to Catherine. They might exist, but my search did not find any.

Mrs. Rouncewell's telling of the tale of the Ghost Walk seems unlike so many other stories within stories that we see in Dickens novels. Pickwick comes to mind. I'm trying to work out wh..."

Mary Lou

Good memory. Yes, that is the first time Guppy made an appearance.

It won’t be the last.:-)

By the way, I took an admittedly quick look through the biography of Catherine Dickens and then a quick Google search for poems by Dickens. He wrote more than I thought but I didn’t find any directed obviously or specifically to Catherine. They might exist, but my search did not find any.

I have just finished Chapter 5 and will limit my comments to that: I do not think that the name Barbary is a slip made by Dickens but that he used it intentionally. My reason for thinking so is that Esther is taken care of by Mr. Jarndyce, and that he must have had some reason for singling her out. Can it not be the case that in some roundabout way, the Barbary family is also involved in the case, which seems to be a kraken of a case, dragging in many families? Mr. Jarndyce probably learned of Esther that way and wanted to do the Barbary family some good in that context. Still, it remains very strange that Esther did not give any sign of recognition when Krook uttered that name.

Mr. Krook is someone I am looking forward to meeting again, and as a symbol of Chancery - displaying its essence of a black hole that is sucking in whatever gets in its way - I am sure that he will be of importance to the novel. He does not really seem to know what good he is getting of all the things he collects, and he seems to be collecting just for the sake of collecting. In that context, I am asking myself how he can make a living when the only thing he does seems to be buying things and never selling any. Maybe, among the many documents he is hoarding there are some that he could sell dearly, or maybe it is his silence that also costs a lot of money. He is obviously not able to read but still he collects all those documents - this is like the Court: There seems to be no sense in its proceedings but somehow everyone connected with it makes a fine living.

Interestingly, in David Copperfield the topic of costly and yet obviously inefficient law proceedings has already been broached in Mr. Spenlow and his partner. Spenlow, as a proctor, also made a lot of money based on obsolete and overblown legal fineries.

Mr. Krook is someone I am looking forward to meeting again, and as a symbol of Chancery - displaying its essence of a black hole that is sucking in whatever gets in its way - I am sure that he will be of importance to the novel. He does not really seem to know what good he is getting of all the things he collects, and he seems to be collecting just for the sake of collecting. In that context, I am asking myself how he can make a living when the only thing he does seems to be buying things and never selling any. Maybe, among the many documents he is hoarding there are some that he could sell dearly, or maybe it is his silence that also costs a lot of money. He is obviously not able to read but still he collects all those documents - this is like the Court: There seems to be no sense in its proceedings but somehow everyone connected with it makes a fine living.

Interestingly, in David Copperfield the topic of costly and yet obviously inefficient law proceedings has already been broached in Mr. Spenlow and his partner. Spenlow, as a proctor, also made a lot of money based on obsolete and overblown legal fineries.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 6

Quite at Home

Well, my friends, this is another very busy chapter. I am going to focus on the characters, new and old, and what I find interesting in structural details rather than sim..."

I was looking forward to this chapter because it gave me the opportunity to get worked up about Skimpole. He is the man I love to hate ;-) As it happens, Dickens loses no time to acquaint us with the darker side of Skimpole, who has no qualms about making Richard and Esther sacrifice all their savings to help him out of a pecuniary difficulty, which is one in a thousand. In other words, the two young people spend all the money they have saved so far to get Skimpole out of a financial debt he has incurred in maybe a month, a fortnight, a week?

I don't know how much of Skimpole's naivity is genuine and how much is assumed, by the way. When he says that he likes to have variety in whom he is helped by and that he wants to give Richard and Esther the opportunity to develop generosity, this might be an excuse for not going to jarndyce, who has all too often helped him out of his difficulties. Probably, Skimpole is afraid of the wind blowing from the east for a while.

Let's also remember that Skimpole has children. We could ask ourselves what kind of childhood these children must have had with such an egocentric, irresponsible father. Is Mr. Jarndyce also looking after these children, or does he limit his attention and support to the unworthy Skimpole himself?

His lofty behaviour towards the man he calles Coavinses also speaks volumes. He tries to make him feel guilty for coming to the house and making him pay his debts, but after all the man is just doing his job, and he might be compelled to do it because he has children of his own to look after.

My final question is whether Mr. Jarndyce, by humouring Skimpole and making so much of him is not also responsible, to a certain degree, for the suffering Skimpole causes to other people, like his children and those people who may have lent him some money?

Quite at Home

Well, my friends, this is another very busy chapter. I am going to focus on the characters, new and old, and what I find interesting in structural details rather than sim..."

I was looking forward to this chapter because it gave me the opportunity to get worked up about Skimpole. He is the man I love to hate ;-) As it happens, Dickens loses no time to acquaint us with the darker side of Skimpole, who has no qualms about making Richard and Esther sacrifice all their savings to help him out of a pecuniary difficulty, which is one in a thousand. In other words, the two young people spend all the money they have saved so far to get Skimpole out of a financial debt he has incurred in maybe a month, a fortnight, a week?

I don't know how much of Skimpole's naivity is genuine and how much is assumed, by the way. When he says that he likes to have variety in whom he is helped by and that he wants to give Richard and Esther the opportunity to develop generosity, this might be an excuse for not going to jarndyce, who has all too often helped him out of his difficulties. Probably, Skimpole is afraid of the wind blowing from the east for a while.

Let's also remember that Skimpole has children. We could ask ourselves what kind of childhood these children must have had with such an egocentric, irresponsible father. Is Mr. Jarndyce also looking after these children, or does he limit his attention and support to the unworthy Skimpole himself?

His lofty behaviour towards the man he calles Coavinses also speaks volumes. He tries to make him feel guilty for coming to the house and making him pay his debts, but after all the man is just doing his job, and he might be compelled to do it because he has children of his own to look after.

My final question is whether Mr. Jarndyce, by humouring Skimpole and making so much of him is not also responsible, to a certain degree, for the suffering Skimpole causes to other people, like his children and those people who may have lent him some money?

Mary Lou wrote: "It's almost exclusively the minor characters in Dickens novels to whom I find myself attached. They're so much more interesting than the main characters.

Same here! I really adore Dickens's minor characters, and for this reason, and some others, BH will be a feast ;-)

Same here! I really adore Dickens's minor characters, and for this reason, and some others, BH will be a feast ;-)

Mary Lou wrote: "Chapter 7

Mrs. Rouncewell's telling of the tale of the Ghost Walk seems unlike so many other stories within stories that we see in Dickens novels. Pickwick comes to mind. I'm trying to work out wh..."

I also wonder why people are so keen on visiting the houses of the great, powerful and beautiful. Saying that, however, I must own that I also visited Dickens's places in Doughty Street and Gad's Hill and would do so again anytime, given the chance. It was particularly moving when I stood in the room where Dickens was supposed to have died, but it was more moving even to see his writing desk where so many great novels came into being :-)

Where might Mr. Guppy have seen Lady Dedlock before? Apparently, the impression that he had set eyes on the lady before is so vivid within him that he cannot think of anything else and is even unable to get his mind out of that groove when faced with the prospect of being told a ghost story, although I don't think Mrs. Rouncewell would have shared the story of the Ghost's Walk with any stranger, not even with someone flourishing the name of Tulkinghorn in order to get the privilege of seeing the house.

Is it foreshadowing when Mrs. Rouncewell says that disgrace will never make its way to Chesney Wold?

Mrs. Rouncewell's telling of the tale of the Ghost Walk seems unlike so many other stories within stories that we see in Dickens novels. Pickwick comes to mind. I'm trying to work out wh..."

I also wonder why people are so keen on visiting the houses of the great, powerful and beautiful. Saying that, however, I must own that I also visited Dickens's places in Doughty Street and Gad's Hill and would do so again anytime, given the chance. It was particularly moving when I stood in the room where Dickens was supposed to have died, but it was more moving even to see his writing desk where so many great novels came into being :-)

Where might Mr. Guppy have seen Lady Dedlock before? Apparently, the impression that he had set eyes on the lady before is so vivid within him that he cannot think of anything else and is even unable to get his mind out of that groove when faced with the prospect of being told a ghost story, although I don't think Mrs. Rouncewell would have shared the story of the Ghost's Walk with any stranger, not even with someone flourishing the name of Tulkinghorn in order to get the privilege of seeing the house.

Is it foreshadowing when Mrs. Rouncewell says that disgrace will never make its way to Chesney Wold?

I enjoyed Chapter 6 with the zig zagging tour of Bleak House. It reminded me of an old ride at Disney World called Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride.

I enjoyed Chapter 6 with the zig zagging tour of Bleak House. It reminded me of an old ride at Disney World called Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride.

Mary Lou wrote: "Chapter 6

I just loved the first part of this chapter - finally meeting John Jarndyce and touring Bleak House. It was a delight. Too bad Dickens didn't end it there and give Skimpole his own chapt..."

I saw it more like she was promised a temporary job/place, and when she came there it turned out she got a job for the long run with benefits. I don't think it's coincidence that in the next chapter we meet Mrs. Rouncewell, who is old and living the last bits of her life in the same position as a housekeeper, with the good standing that comes with it. I think the additional duty clearly comes with additional stability and security. No matter how soon or late Ada will spread her wings and fly out, she is in her late teens already after all, Esther will have a solid position.

I just loved the first part of this chapter - finally meeting John Jarndyce and touring Bleak House. It was a delight. Too bad Dickens didn't end it there and give Skimpole his own chapt..."

I saw it more like she was promised a temporary job/place, and when she came there it turned out she got a job for the long run with benefits. I don't think it's coincidence that in the next chapter we meet Mrs. Rouncewell, who is old and living the last bits of her life in the same position as a housekeeper, with the good standing that comes with it. I think the additional duty clearly comes with additional stability and security. No matter how soon or late Ada will spread her wings and fly out, she is in her late teens already after all, Esther will have a solid position.

I love Bleak House and it's description too. And John, funny is that Bleak House reminded me of The Wind in the Willows somehow, and of course The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad is a Disney-adaptation of that book.

Jantine wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Chapter 6

I just loved the first part of this chapter - finally meeting John Jarndyce and touring Bleak House. It was a delight. Too bad Dickens didn't end it there and give Skimp..."

Jantine

Thank you.

One of the constant delights of this group is how often an observation is made that I have completely missed or ignored in all my previous readings. I have never thought about the fact that Esther and Mrs Rouncewell fulfill reasonably similar roles. The fact that Dickens sets up two consecutive chapters to help highlight this fact is something I have always missed.

It will be interesting to track this fact throughout the novel.

I just loved the first part of this chapter - finally meeting John Jarndyce and touring Bleak House. It was a delight. Too bad Dickens didn't end it there and give Skimp..."

Jantine

Thank you.

One of the constant delights of this group is how often an observation is made that I have completely missed or ignored in all my previous readings. I have never thought about the fact that Esther and Mrs Rouncewell fulfill reasonably similar roles. The fact that Dickens sets up two consecutive chapters to help highlight this fact is something I have always missed.

It will be interesting to track this fact throughout the novel.

Oh and there was so much foreshadowing in the chapter of Chesney Wold! The minor annoying thing about reading a book I've read a lot of times before is that I sometimes really have to sit on my hands and not answer questions posed to ignite discussion with a 'well, of course... ' xD

For me too Skimpole is a person I love to hate. He is very charismatic, the way Esther describes him, and I do think she is truthful in how she describes others. It is very clear to me that in chapter 6 she already has misgivings about him too, she doesn't really seem to trust him or his childlikeness either. I think Skimpole is a mean, egoistic, lazy guy and I want to hit him over the head with a knitting needle. Pah. Go and work like everyone else who doesn't have money does, if you want stuff. Yes, he wants those things he wants, and others have them, but I don't believe for a bit that he is so stupid that he doesn't understand others would rather use those things themselves if they didn't need anything else more. And that there are others who also want it, who can offer something in return. On the other hand, I think we all know (of) people like this. I'm in a fundie snark subreddit, where these types are called 'grifters', letting others pay for the joy of giving them what they want.

For me too Skimpole is a person I love to hate. He is very charismatic, the way Esther describes him, and I do think she is truthful in how she describes others. It is very clear to me that in chapter 6 she already has misgivings about him too, she doesn't really seem to trust him or his childlikeness either. I think Skimpole is a mean, egoistic, lazy guy and I want to hit him over the head with a knitting needle. Pah. Go and work like everyone else who doesn't have money does, if you want stuff. Yes, he wants those things he wants, and others have them, but I don't believe for a bit that he is so stupid that he doesn't understand others would rather use those things themselves if they didn't need anything else more. And that there are others who also want it, who can offer something in return. On the other hand, I think we all know (of) people like this. I'm in a fundie snark subreddit, where these types are called 'grifters', letting others pay for the joy of giving them what they want.

Jantine wrote: "I love Bleak House and it's description too. And John, funny is that Bleak House reminded me of The Wind in the Willows somehow, and of course The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad is a Disney-ada..."

Jantine wrote: "I love Bleak House and it's description too. And John, funny is that Bleak House reminded me of The Wind in the Willows somehow, and of course The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad is a Disney-ada..."Jantine, the description of Jarndyce’s bedroom with only a bedstead, a window always open, and a cold bath reminded me, for some reason, of Thomas Jefferson’s routine of soaking his feet in cold water every morning. Brrrrr.

Jantine wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Chapter 6

I just loved the first part of this chapter - finally meeting John Jarndyce and touring Bleak House. It was a delight. Too bad Dickens didn't end it there and give Skimp..."

The position as a housekeeper - the emblem of which are those bunches of keys - was quite probably one of prestige and meant that Esther was fully trusted by Mr. Jarndyce. It is quite telling that in DC, one of the first things Miss Murdstone does in establishing her metallic self in the Rookery is divesting David's mother of the keys and of her housekeeper's duties. This was on the pretext of sparing her unnecessary trouble but it really meant that now Miss M. would be the one in charge. Being the housekeeper also included keeping tabs on a household's expenditure and keeping costly consumer goods like tea under lock and key.

I just loved the first part of this chapter - finally meeting John Jarndyce and touring Bleak House. It was a delight. Too bad Dickens didn't end it there and give Skimp..."

The position as a housekeeper - the emblem of which are those bunches of keys - was quite probably one of prestige and meant that Esther was fully trusted by Mr. Jarndyce. It is quite telling that in DC, one of the first things Miss Murdstone does in establishing her metallic self in the Rookery is divesting David's mother of the keys and of her housekeeper's duties. This was on the pretext of sparing her unnecessary trouble but it really meant that now Miss M. would be the one in charge. Being the housekeeper also included keeping tabs on a household's expenditure and keeping costly consumer goods like tea under lock and key.

Jantine wrote: "Oh and there was so much foreshadowing in the chapter of Chesney Wold! The minor annoying thing about reading a book I've read a lot of times before is that I sometimes really have to sit on my han..."

Hi Jantine

So true.

I often struggle with what to say, what not to say, and what I can hint at when I prepare a commentary. It’s an interesting conundrum because what I think is interesting and important may not be so for other Curiosities.

Hi Jantine

So true.

I often struggle with what to say, what not to say, and what I can hint at when I prepare a commentary. It’s an interesting conundrum because what I think is interesting and important may not be so for other Curiosities.

One thing I have noticed with the first six chapters is a prose style that seems more rapid than usual for Dickens. Although he was never truly a plodder, the pace of the prose seems to mirror a lot that has happened in these chapters. This may be due to the first person narration of Esther, but it is something that hit me while reading.

One thing I have noticed with the first six chapters is a prose style that seems more rapid than usual for Dickens. Although he was never truly a plodder, the pace of the prose seems to mirror a lot that has happened in these chapters. This may be due to the first person narration of Esther, but it is something that hit me while reading.

Jantine wrote: " I don't think it's coincidence that in the next chapter we meet Mrs. Rouncewell, who is old and living the last bits of her life in the same position as a housekeeper, with the good standing that comes with it. ..."

Jantine wrote: " I don't think it's coincidence that in the next chapter we meet Mrs. Rouncewell, who is old and living the last bits of her life in the same position as a housekeeper, with the good standing that comes with it. ..."I agree with Peter - this was an excellent observation, Jantine! A bit of clever writing from Dickens (too clever for some of us, perhaps), and a reminder to put my 21st century ideas

aside, and remember to view things as Victorians might have. I understood that having "the keys to the kingdom" was a position of trust, but never gave any thought to the stability and status it would have given an orphaned girl, and the security it would afford her once her role as companion was no longer necessary.

Mrs. Flite talks about the Great Seal of chancery a lot, and also starts mentioning it as the Sixth Seal being opened in chapter 3. So I decided to look up the part of Revelation about that seal. Here it is. There is a certain satisfaction in it being about the rich people running and hiding, when Flite is so focused on it.

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/...

Also, fun fact: in Dutch the bible book is called 'openbaringen', which would be 'revelationS' plural. I have learned that it was made into 'revelation' to not have the books of the bible end in the S of Satan. In that version of it was said that it is revelations the plural in practically all other languages too, and I just looked it up and it is revelation singular (Offenbarung) in German too. So as far as I know Dutch might as well be the odd one out. (And yes, the language nerd in me woke up again.)

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/...

Also, fun fact: in Dutch the bible book is called 'openbaringen', which would be 'revelationS' plural. I have learned that it was made into 'revelation' to not have the books of the bible end in the S of Satan. In that version of it was said that it is revelations the plural in practically all other languages too, and I just looked it up and it is revelation singular (Offenbarung) in German too. So as far as I know Dutch might as well be the odd one out. (And yes, the language nerd in me woke up again.)

Jantine wrote: "Mrs. Flite talks about the Great Seal of chancery a lot, and also starts mentioning it as the Sixth Seal being opened in chapter 3. So I decided to look up the part of Revelation about that seal. H..."

Jantine

Thanks for the research. Is it only me or does it seem that Dickens has taken yet another major leap forward in complexity and depth in this novel?

Jantine

Thanks for the research. Is it only me or does it seem that Dickens has taken yet another major leap forward in complexity and depth in this novel?

Mary Lou wrote: "Jantine wrote: " I don't think it's coincidence that in the next chapter we meet Mrs. Rouncewell, who is old and living the last bits of her life in the same position as a housekeeper, with the goo..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Jantine wrote: " I don't think it's coincidence that in the next chapter we meet Mrs. Rouncewell, who is old and living the last bits of her life in the same position as a housekeeper, with the goo..."Yes, thanks Jantine. That was very helpful. I have always wondered what the housekeeper thing is supposed to mean--Esther receives it very positively, but she's a look-on-the-bright side type so I wasn't sure whether that meant anything.

I have an edition this time with no illustrations, so I find myself really wondering whether Esther was portrayed as a stout Nancy-type or a slender Rose Maylie type. I could use some clues as to her class position. Is she the sort of orphan who turns out to be a princess, or the sort of orphan who will get to serve the princess if she's lucky? Ada's clearly a princess and being lined up for a prince (Richard), and Esther's been designated to serve her. But on the other hand, Esther's our narrator and seems to be setting up as a main character, not a supporting character.

Tristram wrote: "My final question is whether Mr. Jarndyce, by humouring Skimpole and making so much of him is not also responsible, to a certain degree, for the suffering Skimpole causes to other people, like his children and those people who may have lent him some money?"

Tristram wrote: "My final question is whether Mr. Jarndyce, by humouring Skimpole and making so much of him is not also responsible, to a certain degree, for the suffering Skimpole causes to other people, like his children and those people who may have lent him some money?"You know, I kind of think he is. Clearly he's enabling Skimpole, and there's so much denial in his insistence on calling S a child. I know I am supposed to love Mr. Jarndyce and certainly he's a generous delight to our trio of wards, but his refusal to notice when people are misbehaving is harmful, and I find I am wanting to shake some sense into him.

I'd venture it's Jarndyce rather than Skimpole who's the child.

Julie wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Jantine wrote: " I don't think it's coincidence that in the next chapter we meet Mrs. Rouncewell, who is old and living the last bits of her life in the same position as a housekee..."

In the pictures in the old paperback I once got from my Gramps, she was more the Rose Maylie type. I think she will turn out to be perhaps not the princess, for that is Ada, but certainly no servant either. Just, as I now realise, like she was taught in school to be a governess and now is a housekeeper, the two types of servant who were not a real servant like the others, but not part of The Family either. So not a servant, but she does serve the princess (Ada) like a dear friend, just like ladies in waiting did with the queen/princess, and high up enough to be at risk of falling in love like Jane Eyre did.

In the pictures in the old paperback I once got from my Gramps, she was more the Rose Maylie type. I think she will turn out to be perhaps not the princess, for that is Ada, but certainly no servant either. Just, as I now realise, like she was taught in school to be a governess and now is a housekeeper, the two types of servant who were not a real servant like the others, but not part of The Family either. So not a servant, but she does serve the princess (Ada) like a dear friend, just like ladies in waiting did with the queen/princess, and high up enough to be at risk of falling in love like Jane Eyre did.

Jantine wrote: "Julie wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Jantine wrote: " I don't think it's coincidence that in the next chapter we meet Mrs. Rouncewell, who is old and living the last bits of her life in the same position..."

Jantine wrote: "Julie wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Jantine wrote: " I don't think it's coincidence that in the next chapter we meet Mrs. Rouncewell, who is old and living the last bits of her life in the same position..."This is making me re-think all the categories. My knowledge of 19th c servant status is pretty much shaped by novels, so I had it in my head that the governess or companion is a gentlewoman fallen on hard times and the housekeeper is someone lower-class who's prospered--like Mrs. Rouncewell from the market-town who has worked her way up from the stillroom. But now that I'm thinking through it more, I can come up with examples of housekeepers in novels who take great pride in being related to the family, or related to somebody else of higher status, so I guess it was also an option for gentlewomen with few options.

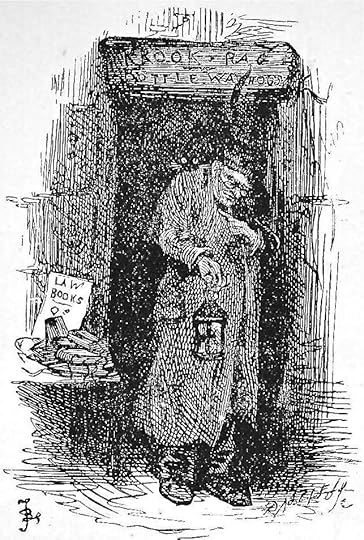

The Lord Chancellor Copies from Memory

Chapter 5

Phiz

Text illustrated:

"Passing through the shop on our way out, as we had passed through it on our way in, we found the old man storing a quantity of packets of waste-paper in a kind of well in the floor. He seemed to be working hard, with the perspiration standing on his forehead, and had a piece of chalk by him, with which, as he put each separate package or bundle down, he made a crooked mark on the panelling of the wall.

Richard and Ada, and Miss Jellyby, and the little old lady had gone by him, and I was going when he touched me on the arm to stay me, and chalked the letter J upon the wall — in a very curious manner, beginning with the end of the letter and shaping it backward. It was a capital letter, not a printed one, but just such a letter as any clerk in Messrs. Kenge and Carboy's office would have made.

"Can you read it?" he asked me with a keen glance.

"Surely," said I. "It's very plain."

"What is it?"

"J."

With another glance at me, and a glance at the door, he rubbed it out and turned an "a" in its place (not a capital letter this time), and said, "What's that?"

I told him. He then rubbed that out and turned the letter "r," and asked me the same question. He went on quickly until he had formed in the same curious manner, beginning at the ends and bottoms of the letters, the word Jarndyce, without once leaving two letters on the wall together.

"What does that spell?" he asked me.

When I told him, he laughed. In the same odd way, yet with the same rapidity, he then produced singly, and rubbed out singly, the letters forming the words Bleak House. These, in some astonishment, I also read; and he laughed again.

"Hi!" said the old man, laying aside the chalk. "I have a turn for copying from memory, you see, miss, though I can neither read nor write."

He looked so disagreeable and his cat looked so wickedly at me, as if I were a blood-relation of the birds upstairs, that I was quite relieved by Richard's appearing at the door and saying, "Miss Summerson, I hope you are not bargaining for the sale of your hair. Don't be tempted. Three sacks below are quite enough for Mr. Krook!"

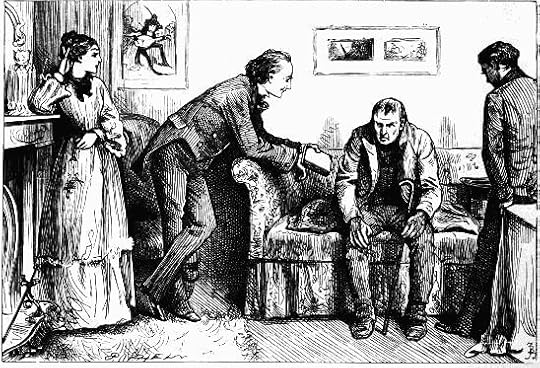

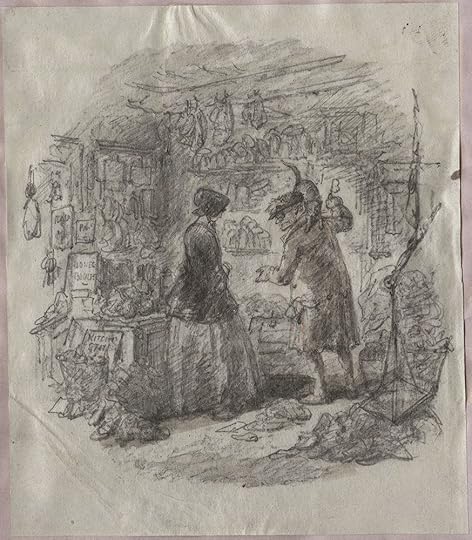

Coavinses

Chapter 6

Phiz

Text illustrated:

[Esther, who is narrating chapter 6, "Quite at Home," relates that an excited maid at Bleak House tells her "Oh, if you please, miss, Mr. Carstone says would you come upstairs to Mr. Skimpole's room. He has been took, miss!" Esther, assuming Skimpole has fallen serious ill, rushes up to his room to discover that he has been "arrested for debt."] (I can't stand this guy)

"And really, my dear Miss Summerson," said Mr. Skimpole with his agreeable candour, "I never was in a situation in which that excellent sense and quiet habit of method and usefulness, which anybody must observe in you who has the happiness of being a quarter of an hour in your society, was more needed."

The person on the sofa, who appeared to have a cold in his head, gave such a very loud snort that he startled me.

"Are you arrested for much, sir?" I inquired of Mr. Skimpole.

"My dear Miss Summerson," said he, shaking his head pleasantly, "I don't know. Some pounds, odd shillings, and halfpence, I think, were mentioned."

"It's twenty-four pound, sixteen, and sevenpence ha'penny," observed the stranger. "That's wot it is."

"And it sounds — somehow it sounds," said Mr. Skimpole, "like a small sum?"

The strange man said nothing but made another snort. It was such a powerful one that it seemed quite to lift him out of his seat.

"Mr. Skimpole," said Richard to me, "has a delicacy in applying to my cousin Jarndyce because he has lately — I think, sir, I understood you that you had lately — "

"Oh, yes!" returned Mr. Skimpole, smiling. "Though I forgot how much it was and when it was. Jarndyce would readily do it again, but I have the epicure-like feeling that I would prefer a novelty in help, that I would rather," and he looked at Richard and me, "develop generosity in a new soil and in a new form of flower."

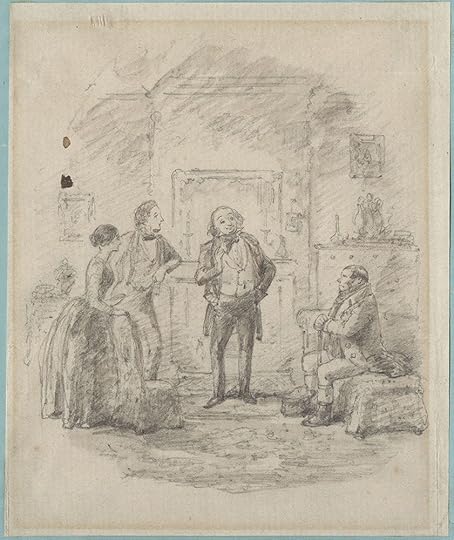

The Lord Chancellor relates the death of Tom Jarndyce

Chapter 5

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"Aye!" said the old man, coming slowly out of his abstraction. "Yes! Tom Jarndyce—you'll excuse me, being related; but he was never known about court by any other name, and was as well known there as—she is now," nodding slightly at his lodger. "Tom Jarndyce was often in here. He got into a restless habit of strolling about when the cause was on, or expected, talking to the little shopkeepers and telling 'em to keep out of Chancery, whatever they did. 'For,' says he, 'it's being ground to bits in a slow mill; it's being roasted at a slow fire; it's being stung to death by single bees; it's being drowned by drops; it's going mad by grains.' He was as near making away with himself, just where the young lady stands, as near could be."

We listened with horror.

"He come in at the door," said the old man, slowly pointing an imaginary track along the shop, "on the day he did it—the whole neighbourhood had said for months before that he would do it, of a certainty sooner or later—he come in at the door that day, and walked along there, and sat himself on a bench that stood there, and asked me (you'll judge I was a mortal sight younger then) to fetch him a pint of wine. 'For,' says he, 'Krook, I am much depressed; my cause is on again, and I think I'm nearer judgment than I ever was.' I hadn't a mind to leave him alone; and I persuaded him to go to the tavern over the way there, t'other side my lane (I mean Chancery Lane); and I followed and looked in at the window, and saw him, comfortable as I thought, in the arm-chair by the fire, and company with him. I hadn't hardly got back here when I heard a shot go echoing and rattling right away into the inn. I ran out—neighbours ran out—twenty of us cried at once, 'Tom Jarndyce!'"

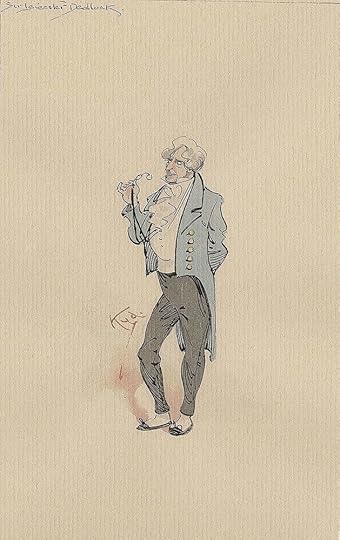

"We are not so prejudiced as to suppose that in private life you are otherwise than a very estimable man, with a great deal of poetry in your nature, of which you may not be conscious"

Chapter 6

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"Keep your temper, my good fellow, keep your temper!" Mr. Skimpole gently reasoned with him as he made a little drawing of his head on the fly-leaf of a book. "Don't be ruffled by your occupation. We can separate you from your office; we can separate the individual from the pursuit. We are not so prejudiced as to suppose that in private life you are otherwise than a very estimable man, with a great deal of poetry in your nature, of which you may not be conscious."

It doesn't matter what he says, when this guy opens his mouth I want to hit something.

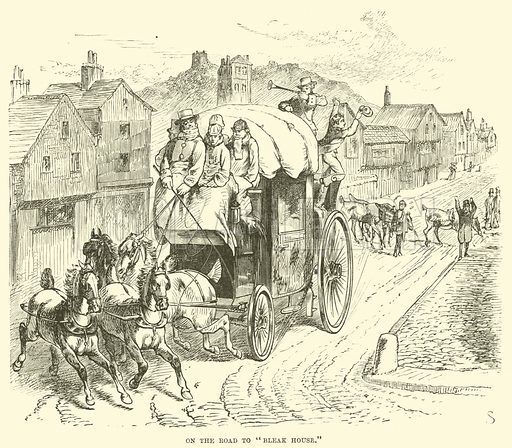

On the road to Bleak House

Chapter 5

Thomas Archer

1890

Text Illustrated:

She was by that time perseveringly dictating to Caddy, and Caddy was fast relapsing into the inky condition in which we had found her. At one o'clock an open carriage arrived for us, and a cart for our luggage. Mrs. Jellyby charged us with many remembrances to her good friend Mr. Jarndyce; Caddy left her desk to see us depart, kissed me in the passage, and stood biting her pen and sobbing on the steps; Peepy, I am happy to say, was asleep and spared the pain of separation (I was not without misgivings that he had gone to Newgate market in search of me); and all the other children got up behind the barouche and fell off, and we saw them, with great concern, scattered over the surface of Thavies Inn as we rolled out of its precincts.

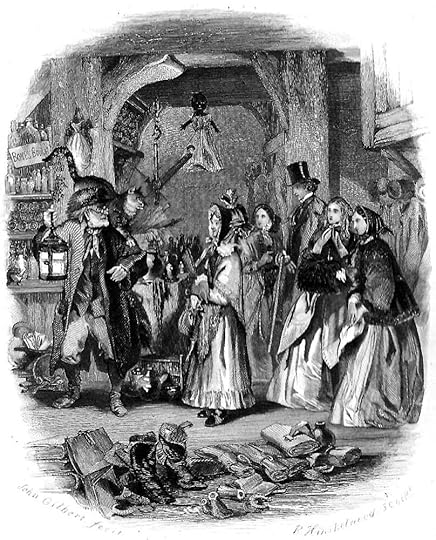

Mr. Krook and His Cat

Chapter 5

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

"You see, I have so many things here," he resumed, holding up the lantern, "of so many kinds, and all as the neighbours think (but they know nothing), wasting away and going to rack and ruin, that that's why they have given me and my place a christening. And I have so many old parchmentses and papers in my stock. And I have a liking for rust and must and cobwebs. And all's fish that comes to my net. And I can't abear to part with anything I once lay hold of (or so my neighbors think, but what do they know?) or to alter anything, or to have any sweeping, nor scouring, nor cleaning, nor repairing going on about me. That's the way I've got the ill name of Chancery. I don't mind. I go to see my noble and learned brother pretty well every day, when he sits in the Inn. He don't notice me, but I notice him. There's no great odds betwixt us. We both grub on in a muddle. Hi, Lady Jane!"

A large grey cat leaped from some neighboring shelf on [Mr. Krook's] shoulder and startled us all. "Hi! Show 'em how you scratch. Hi! Tear, my lady!" said her master. [Chapter 5, "A Morning Adventure,"]

Commentary:

Krook and his Recycling Establishment, 1856-1910

A number of nineteenth-century illustrators depicted the novel's eccentric rag-and-bone recycler who lets rooms to the demented Miss Flite. The most flattering interpretation of Krook is that by Sir John Gilbert, and the most critical that by Furniss. Generously, Gilbert dramatizes Krook as a Prospero-like guide for the young, middle-class visitors to his cavernous emporium; his odd manner of dress, suggesting eighteenth-century male fashion, contrasts the contemporary, "respectable" upper-middle class fashions of his visitors. Like Hablot Knight Browne and Gilbert, Furniss suggests the chaotic nature of Krook's shop by the books, boots, and portmanteaus in the foreground. Whereas Krook appears just as Dickens describes him, "an old man in spectacles and a hairy cap . . . carrying about" a lantern in the Phiz and Gilbert illustrations, Furniss focusses on his crooked figure without providing much background or any sense of whom Krook is directing as he glances nervously over his shoulder at us. His splayed fingers and angular legs support the interpretation that he is decidedly odd, if not insane, thereby supplementing Dickens's description: "he was short, cadaverous, and withered; with his head sideways between his shoulders, and the breath issuing in visible smoke from his mouth, as if he were on fire within. His throat, chin, and eyebrows were so frosted with white hairs, and so gnarled with veins and puckered skin, that he looked from his breast upward, like some old root in a fall of snow".

Furniss regards Krook as not merely eccentric, but demented, his goggle eyes imply a manic or disturbed personality. On the other hand, Fred Barnard in the Household Edition shows him as a relatively normal person in slightly peculiar clothing as he narrates the story oftheJarndyce Chancery suit. In all of these visual interpretations, Krook is an extension of his shop, but Furniss focusses upon his figure and places the cat in a prominent position, on his shoulder, rather than in a less conspicuous position, as in the Barnard half-page illustration.

Here is Kim to solve all our illustration questions about how Esther gets depicted except--wait, Kim! I checked this set and the first installment's, and in the original Phiz illustrations, do we NEVER SEE ESTHER'S FACE?

Here is Kim to solve all our illustration questions about how Esther gets depicted except--wait, Kim! I checked this set and the first installment's, and in the original Phiz illustrations, do we NEVER SEE ESTHER'S FACE?It looks like we get kind of a side-view of her cheek and nose in the "Coavinses" illustration, but otherwise she seems to be behind a bonnet or with her back turned.

This isn't normal Phiz, is it?

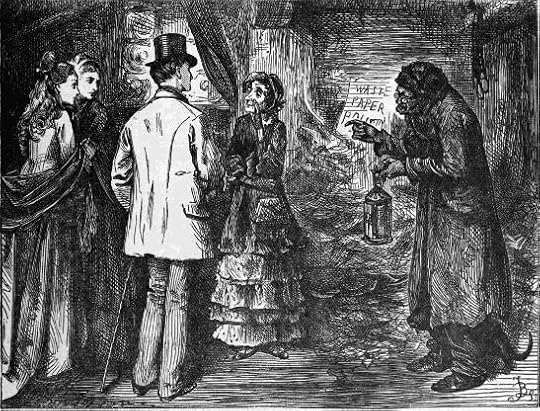

A large grey cap leaped from some neighbouring shelf

Chapter 5

Sir John Gilbert

Text Illustrated:

"You see, I have so many things here," he resumed, holding up the lantern, "of so many kinds, and all as the neighbours think (but they know nothing), wasting away and going to rack and ruin, that that's why they have given me and my place a christening. And I have so many old parchmentses and papers in my stock. And I have a liking for rust and must and cobwebs. And all's fish that comes to my net. And I can't abear to part with anything I once lay hold of (or so my neighbors think, but what do they know?) or to alter anything, or to have any sweeping, nor scouring, nor cleaning, nor repairing going on about me. That's the way I've got the ill name of Chancery. I don't mind. I go to see my noble and learned brother pretty well every day, when he sits in the Inn. He don't notice me, but I notice him. There's no great odds betwixt us. We both grub on in a muddle. Hi, Lady Jane!"

A large grey cat leaped from some neighboring shelf on his shoulder and startled us all. "Hi! Show 'em how you scratch. Hi! Tear, my lady!" said her master.

The cat leaped down and ripped at a bundle of rags with her tigerish claws, with a sound that it set my teeth on edge to hear. — Chapter 5, "A Morning Adventure,"

Commentary:

Sir John Gilbert provided sporadic relief for the series' principal illustrator, Felix Octavius Carr Darley, typically providing a frontispiece for the third volume in a four-volume set. Here, however, he had to provide the first in the series of four, and the British spellings in the caption — “A large grey cat leaped from some neighbouring shelf on his shoulder and startled us all” (emphasis added)— suggest that Gilbert was working from a British text (possibly the single volume of 1853, or the Cheap Edition of 1858) rather than a proof of the Sheldon and Company volume of 1863 — the American editors have consistently Americanized the spellings within the text, but probably could not alter the caption since it was already integrated into the plate by the New York engraver "R Hinshelwood" (born in England, but working inAmerica since 1835), whose signature appears at the bottom right of the composition, which it is not unreasonable to assume was mailed from England. (Hinshelwood, although chiefly remembered today as a landscape painter, was both an etcher and engraver who worked for New York publishing houses such as Harper's, and took commissions for bank note engraving for Continental Bank Note Company, which also employed the talents of Darley, the principal illustrator of the "Household" Edition of Dickens's works in fifty-five volumes, 1861-72.)

The other unusual aspect of the illustration is that it is by far Gilbert's most effectivecontribution to the series, with Krook, the Prospero-like proprietor of the rag-and-bone shop whose odd manner of dress contraststhe "respectable" upper-middle class fashions of his visitors, and with the chaotic nature of what we might term a "recycling" establishment admirably suggested by the books, boots, and portmanteaus in the foreground. Krook appears just as Dickens describes him, "an old man in spectacles and a hairy cap . . . carrying about" a lantern:

he was short, cadaverous, and withered; with his head sideways between his shoulders, and the breath issuing in visible smoke from his mouth, as if he were on fire within. His throat, chin, and eyebrows were so frosted with white hairs, and so gnarled with veins and puckered skin, that he looked from his breast upward, like some old root in a fall of snow.

Given the specificity of the author's description of the shop and its owner, Gilbert's task here was a little easier in that he did not have to provide much visual continuity with any of the Darley Bleak House frontispieces; however, like Darley in A female figure, closely veiled, stands in the middle of the room. . . (the frontispiece for the second volume), he had to take into account the Hablot Knight Browne depictions of the characters such as Krook in the original monthly parts. We, like the young, upper-middle-class visitors, see in the shop a riotous profusion of detail. The elderly lady in the large bonnet is Miss Flite, a slightly demented petitioner to the Court of Chancery; she is what the young petitioners may become, if they don't die or abandon their suits first: Richard Carstone, ward of John Jarndyce, is head and shoulders taller than the three young women. They look utterly alike, so that it is impossible to say which is the fair-tressed Ada Clare, which the sour Caddy Jellyby, and which Esther Summerson, the first-person narrator of this part of the story, even though Ada ought to be "remarkably beautiful".

As for Mrs. Rouncewell, the only illustration of her I found so far is from the mind of Kyd. Keep in mind Linda once said that every woman Kyd drew looked like a man in drag:

Julie wrote: "Here is Kim to solve all our illustration questions about how Esther gets depicted except--wait, Kim! I checked this set and the first installment's, and in the original Phiz illustrations, do we N..."

Well I'm not sure without looking through them all right now, but now that you mention it I can't think of many that Esther is even in, as the main subject anyway. She always seems like a background character. Peter will be able to tell us more though, he's a Phiz expert. I haven't found a Mrs. Rouncewell one either except Kyd and Kyd doesn't count. :-)

Well I'm not sure without looking through them all right now, but now that you mention it I can't think of many that Esther is even in, as the main subject anyway. She always seems like a background character. Peter will be able to tell us more though, he's a Phiz expert. I haven't found a Mrs. Rouncewell one either except Kyd and Kyd doesn't count. :-)