The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Bleak House

>

Bleak House, Chp. 30-32

Chapter 31 is titled "Nurse and Patient" and the first thing that Esther tells us is that although Charley does practice, she is not making progress in her handwriting, telling us that writing was a trying business to Charley who seems to have no control over a pen. While Esther watches, Charley tells her that Jenny, the brickmaker's wife and her friend Liz have come back to their town with their families. Jenny had been at the doctor's shop where she met Charley, and Charley tells Esther that she is taking care of a poor, sick boy who had once done the same for her. Esther and Charley decide to go and see if they can be any help and we find that the poor boy is Jo. At the cottage, Esther, with her veil still down, greets Jenny and looks at the boy on the floor. The boy, Jo that is, instantly jumps up and stares at Esther with a look of surprise and terror. Jo says immediately that he "won't go no more to the berryin ground". Jenny asks him what’s the matter and Jo says:

"The lady there. She's come to get me to go along with her to the berryin ground. I won't go to the berryin ground. I don't like the name on it. She might go a-berryin ME."

When Esther lifts her veil Jo says that it isn't the same bonnet or gown, but she still looks like the "other one". He tells Esther and Charley about his sickness.

"I'm a-being froze," returned the boy hoarsely, with his haggard gaze wandering about me, "and then burnt up, and then froze, and then burnt up, ever so many times in a hour. And my head's all sleepy, and all a-going mad-like—and I'm so dry—and my bones isn't half so much bones as pain."

Jenny tells Esther that Jo must leave before her husband gets home. Esther and Charley decide to take Jo home with them and ask the advice of Mr. Jarndyce. When they get home they find Mr. Skimpole has arrived for another one of his visits of three weeks probably, and he tells Mr. Jarndyce to send Jo away. He says Jo’s illness makes him unsafe to be around. He continues his argument for sending Jo away for some time, which would certainly have made me dislike him if I could stand him in the first place, which I can't. But Mr. Jarndyce tells Esther to settle him on the bed in the loft room of the stable. While I was glad that Mr. Jarndyce gave Jo a place to sleep I was very disappointed when, instead of sending Skimpole away after the things he said merely says:

"I believe," returned my guardian, resuming his uneasy walk, "that there is not such another child on earth as yourself."

I believe that too, at least I hope so. In the morning, Jo is gone, no one knows where he could have gone or why he would have left. They look for him everywhere, but to no avail. After five days of searching there is still no sign of him. Meanwhile, Esther notices Charley shivering in her room one night, and in a few hours she is sick and becomes much sicker very quickly. Esther has her moved into her own room and nurses her, forbidding anyone else to come into the room, including Ada. Charley nearly dies, but she slowly recovers. And although Esther had been worried that Charley's pretty looks would become disfigured that doesn't happen and Charley becomes the same cheerful girl she had always been. Esther, however, contracts the disease and becomes very sick too. She confides in Charley, telling her not to let Ada into the room. The chapter ends with:

"Now, Charley, when she knows I am ill, she will try to make her way into the room. Keep her out, Charley, if you love me truly, to the last! Charley, if you let her in but once, only to look upon me for one moment as I lie here, I shall die."

"I never will! I never will!" she promised me.

"I believe it, my dear Charley. And now come and sit beside me for a little while, and touch me with your hand. For I cannot see you, Charley; I am blind."

And now that I'm thinking of it, she is much more calm at suddenly being blind than I would be.

"The lady there. She's come to get me to go along with her to the berryin ground. I won't go to the berryin ground. I don't like the name on it. She might go a-berryin ME."

When Esther lifts her veil Jo says that it isn't the same bonnet or gown, but she still looks like the "other one". He tells Esther and Charley about his sickness.

"I'm a-being froze," returned the boy hoarsely, with his haggard gaze wandering about me, "and then burnt up, and then froze, and then burnt up, ever so many times in a hour. And my head's all sleepy, and all a-going mad-like—and I'm so dry—and my bones isn't half so much bones as pain."

Jenny tells Esther that Jo must leave before her husband gets home. Esther and Charley decide to take Jo home with them and ask the advice of Mr. Jarndyce. When they get home they find Mr. Skimpole has arrived for another one of his visits of three weeks probably, and he tells Mr. Jarndyce to send Jo away. He says Jo’s illness makes him unsafe to be around. He continues his argument for sending Jo away for some time, which would certainly have made me dislike him if I could stand him in the first place, which I can't. But Mr. Jarndyce tells Esther to settle him on the bed in the loft room of the stable. While I was glad that Mr. Jarndyce gave Jo a place to sleep I was very disappointed when, instead of sending Skimpole away after the things he said merely says:

"I believe," returned my guardian, resuming his uneasy walk, "that there is not such another child on earth as yourself."

I believe that too, at least I hope so. In the morning, Jo is gone, no one knows where he could have gone or why he would have left. They look for him everywhere, but to no avail. After five days of searching there is still no sign of him. Meanwhile, Esther notices Charley shivering in her room one night, and in a few hours she is sick and becomes much sicker very quickly. Esther has her moved into her own room and nurses her, forbidding anyone else to come into the room, including Ada. Charley nearly dies, but she slowly recovers. And although Esther had been worried that Charley's pretty looks would become disfigured that doesn't happen and Charley becomes the same cheerful girl she had always been. Esther, however, contracts the disease and becomes very sick too. She confides in Charley, telling her not to let Ada into the room. The chapter ends with:

"Now, Charley, when she knows I am ill, she will try to make her way into the room. Keep her out, Charley, if you love me truly, to the last! Charley, if you let her in but once, only to look upon me for one moment as I lie here, I shall die."

"I never will! I never will!" she promised me.

"I believe it, my dear Charley. And now come and sit beside me for a little while, and touch me with your hand. For I cannot see you, Charley; I am blind."

And now that I'm thinking of it, she is much more calm at suddenly being blind than I would be.

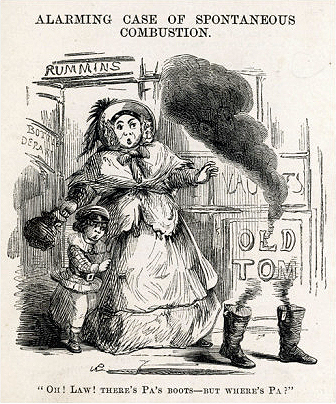

Chapter 32 is titled "The Appointed Time" and we have left Esther in bed and are back to our third person narrator. We are in Lincoln's Inn,"the troublous valley of the shadow of the law."

Even though it is a damp, misty night Mr. Weevle (Jobling) has been walking up and down the stairs from his room to the street over and over again. We are told he is very uneasy and on one of his walks to the street he meets Mr. Snagsby who is also uneasy and out for a ten minute walk after supper. While they talk Mr. Snagsby mentions that it seems a little "greasy" that night and Mr. Weevle agrees that there is "a queer kind of flavour in the place to-night". Mr. Weevle thinks it is chops cooking at the nearby restaurant and Mr. Snagsby says they smell burnt and not quite fresh. They talk of the lodger who died in the same room Mr. Weevle now rents and Mr. Snagsby says he could never have slept there, he then hurries home so his little woman won't be looking for him. She has followed him this entire time though. So far people who are married in this book should have given it some more thought before taking vows. There is Mr. and Mrs. Snagsby, they can't be happy with each other, Mrs Snagsby isn't happy with anyone, then there is Mr. and Mrs. Jellyby, poor Mr. Jellyby I wonder what his wife was like when they first got married. Jenny should have stayed away from the brickmaker, and while Lord Dedlock seems happy his wife certainly isn't. And poor Mrs. Smallweed!

Just as Mr. Snagsby leaves Mr. Guppy arrives and we learn that Mr. Weevle has been waiting for Guppy all evening. They go to Weevle's room and Mr. Guppy says he waited until Mr. Snagsby left to show himself. Weevle tells him he is depressed in the room he is renting saying it is a unbearably dull, suicidal room. They sit in the room whispering and Weevle says that he feels they are planning a murder with all the whispering and mystery. We now find that the reason Guppy is there is because Weevle has an appointment to meet Krook downstairs at midnight. Krook had taken a bundle of letters from the dead lodger's portmanteau, but because he can't read he has asked Weevle to bring the letters to his own room and read over them then telling Krook what the letters said and who they were from. Guppy notices soot on the arm of his coat and asks Weevle if a chimney is on fire, the soot won't wipe off his coat it "smears like black fat". They open the window to get some air and Guppy touches the window sill but pulls his hand away:

"What, in the devil's name," he says, "is this! Look at my fingers!"

A thick, yellow liquor defiles them, which is offensive to the touch and sight and more offensive to the smell. A stagnant, sickening oil with some natural repulsion in it that makes them both shudder.

"What have you been doing here? What have you been pouring out of window?"

"I pouring out of window! Nothing, I swear! Never, since I have been here!" cries the lodger

And yet look here—and look here! When he brings the candle here, from the corner of the window-sill, it slowly drips and creeps away down the bricks, here lies in a little thick nauseous pool."

Guppy washes his hands and has a glass of brandy to calm himself and by then it is midnight and here comes the part of the book you either seem to love or hate. Mr. Weevle goes downstairs to meet Krook, but runs back into the room again in no more than a minute or two. He tells Guppy that Krook isn't there but the soot and oil is there. They go back downstairs together where there is a smoldering, suffocating vapor in the room and a dark, greasy coating on the walls and ceiling. Everything else is in it's usual place. And then this happens which makes me smile no matter how many times I read it:

"Here is a small burnt patch of flooring; here is the tinder from a little bundle of burnt paper, but not so light as usual, seeming to be steeped in something; and here is—is it the cinder of a small charred and broken log of wood sprinkled with white ashes, or is it coal? Oh, horror, he IS here! And this from which we run away, striking out the light and overturning one another into the street, is all that represents him.

Help, help, help! Come into this house for heaven's sake! Plenty will come in, but none can help. The Lord Chancellor of that court, true to his title in his last act, has died the death of all lord chancellors in all courts and of all authorities in all places under all names soever, where false pretences are made, and where injustice is done. Call the death by any name your Highness will, attribute it to whom you will, or say it might have been prevented how you will, it is the same death eternally—inborn, inbred, engendered in the corrupted humours of the vicious body itself, and that only—spontaneous combustion, and none other of all the deaths that can be died."

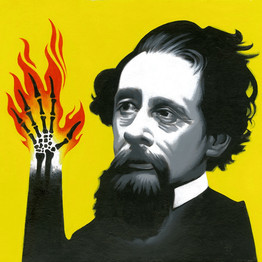

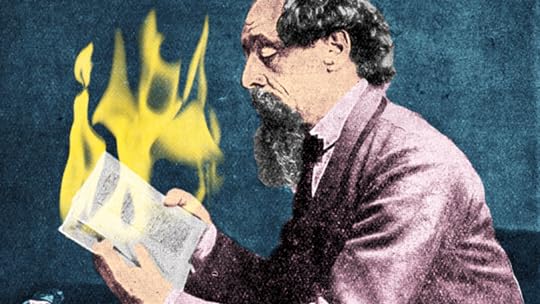

I'm not sure if I ever saw anything in Dickens more debated than Krook's spontaneous combustion. And I never saw a death more amusing than Krook's. As far as I can tell most of Dicken's readers had no trouble believing it and never even questioned Krook's unusual death. There were others however, that found it "nonsense". George Henry Lewes, a literature critic at the time writing for "The Leader" acknowledged that the authors have a license to stretch the truth, but said that novelists can’t just ignore the laws of physics. He went on to say that "these circumstances are beyond the limits of acceptable fiction,” He also accused Dickens “of giving currency to a vulgar error". And Dickens responded and he and Lewis argued back and forth in letters for quite some time. Dickens says this in a later preface to the novel:

"There is only one other point on which I offer a word of remark. The possibility of what is called spontaneous combustion has been denied since the death of Mr. Krook; and my good friend Mr. Lewes (quite mistaken, as he soon found, in supposing the thing to have been abandoned by all authorities) published some ingenious letters to me at the time when that event was chronicled, arguing that spontaneous combustion could not possibly be. I have no need to observe that I do not wilfully or negligently mislead my readers and that before I wrote that description I took pains to investigate the subject. There are about thirty cases on record, of which the most famous, that of the Countess Cornelia de Baudi Cesenate, was minutely investigated and described by Giuseppe Bianchini, a prebendary of Verona, otherwise distinguished in letters, who published an account of it at Verona in 1731, which he afterwards republished at Rome. The appearances, beyond all rational doubt, observed in that case are the appearances observed in Mr. Krook's case. The next most famous instance happened at Rheims six years earlier, and the historian in that case is Le Cat, one of the most renowned surgeons produced by France. The subject was a woman, whose husband was ignorantly convicted of having murdered her; but on solemn appeal to a higher court, he was acquitted because it was shown upon the evidence that she had died the death of which this name of spontaneous combustion is given. I do not think it necessary to add to these notable facts, and that general reference to the authorities which will be found at page 30, vol. ii., the recorded opinions and experiences of distinguished medical professors, French, English, and Scotch, in more modern days, contenting myself with observing that I shall not abandon the facts until there shall have been a considerable spontaneous combustion of the testimony on which human occurrences are usually received."

Here are some later cases for you:

"Henry Thomas, a 73-year-old man, was found burned to death in the living room of his council house on the Rassau council estate in Ebbw Vale, south Wales, in 1980. His entire body was incinerated, leaving only his skull and a portion of each leg below the knee. The feet and legs were still clothed in socks and trousers. Half of the chair in which he had been sitting was also destroyed. Police forensic officers decided that the incineration of Thomas was due to the wick effect. His death was ruled 'death by burning', as he had plainly inhaled the contents of his own combustion."

In December 2010, the death of Michael Faherty in County Galway, Ireland, was recorded as "spontaneous combustion" by the coroner. The doctor, Ciaran McLoughlin, made this statement at the inquiry into the death: "This fire was thoroughly investigated and I'm left with the conclusion that this fits into the category of spontaneous human combustion, for which there is no adequate explanation."

"Jack Angel, who had been hospitalized with severe burns, brought a court case against the manufacturer of his hot water heater for three million dollars. He said that he went to check the malfunctioning heater and it blew and scalded him. However, a doctor noted that his body had burned from the inside out, not the outside in. Shortly afterward, he changed his story and said he fell asleep only to wake up with terrible burns all over his body, and sold his story as a survivor of spontaneous human combustion. Was he one of the only people to survive spontaneously combusting?"

"A mentally disabled woman lived with her father, who cared for her. One day he saw a flash out of the corner of his eye, and turned to find her on fire. Despite the flames, she continued to quietly sit in a chair, not reacting and not giving any indication she was in pain. The man's attempts to put the fire out left him with burned hands. The woman lived through the combustion, but slipped into a coma and died shortly afterwards. This indicates one of the strangest parts of human combustion. It takes a very hot flame to reduce a human body to ash. Crematoriums have special chambers designed for it. However, in almost all combustions, there's no burns in the room around the body, indicating that the person simply stayed in one place."

Whether people spontaneously combust or not, it is certainly one of the oddest deaths I've ever read. I wonder why Dickens chose it. Oh, and it's up to you to decide whether to believe the above people burst into flames, I have no opinion on the matter except if Dickens said it it must be true. I'm off for the illustrations. :-)

Even though it is a damp, misty night Mr. Weevle (Jobling) has been walking up and down the stairs from his room to the street over and over again. We are told he is very uneasy and on one of his walks to the street he meets Mr. Snagsby who is also uneasy and out for a ten minute walk after supper. While they talk Mr. Snagsby mentions that it seems a little "greasy" that night and Mr. Weevle agrees that there is "a queer kind of flavour in the place to-night". Mr. Weevle thinks it is chops cooking at the nearby restaurant and Mr. Snagsby says they smell burnt and not quite fresh. They talk of the lodger who died in the same room Mr. Weevle now rents and Mr. Snagsby says he could never have slept there, he then hurries home so his little woman won't be looking for him. She has followed him this entire time though. So far people who are married in this book should have given it some more thought before taking vows. There is Mr. and Mrs. Snagsby, they can't be happy with each other, Mrs Snagsby isn't happy with anyone, then there is Mr. and Mrs. Jellyby, poor Mr. Jellyby I wonder what his wife was like when they first got married. Jenny should have stayed away from the brickmaker, and while Lord Dedlock seems happy his wife certainly isn't. And poor Mrs. Smallweed!

Just as Mr. Snagsby leaves Mr. Guppy arrives and we learn that Mr. Weevle has been waiting for Guppy all evening. They go to Weevle's room and Mr. Guppy says he waited until Mr. Snagsby left to show himself. Weevle tells him he is depressed in the room he is renting saying it is a unbearably dull, suicidal room. They sit in the room whispering and Weevle says that he feels they are planning a murder with all the whispering and mystery. We now find that the reason Guppy is there is because Weevle has an appointment to meet Krook downstairs at midnight. Krook had taken a bundle of letters from the dead lodger's portmanteau, but because he can't read he has asked Weevle to bring the letters to his own room and read over them then telling Krook what the letters said and who they were from. Guppy notices soot on the arm of his coat and asks Weevle if a chimney is on fire, the soot won't wipe off his coat it "smears like black fat". They open the window to get some air and Guppy touches the window sill but pulls his hand away:

"What, in the devil's name," he says, "is this! Look at my fingers!"

A thick, yellow liquor defiles them, which is offensive to the touch and sight and more offensive to the smell. A stagnant, sickening oil with some natural repulsion in it that makes them both shudder.

"What have you been doing here? What have you been pouring out of window?"

"I pouring out of window! Nothing, I swear! Never, since I have been here!" cries the lodger

And yet look here—and look here! When he brings the candle here, from the corner of the window-sill, it slowly drips and creeps away down the bricks, here lies in a little thick nauseous pool."

Guppy washes his hands and has a glass of brandy to calm himself and by then it is midnight and here comes the part of the book you either seem to love or hate. Mr. Weevle goes downstairs to meet Krook, but runs back into the room again in no more than a minute or two. He tells Guppy that Krook isn't there but the soot and oil is there. They go back downstairs together where there is a smoldering, suffocating vapor in the room and a dark, greasy coating on the walls and ceiling. Everything else is in it's usual place. And then this happens which makes me smile no matter how many times I read it:

"Here is a small burnt patch of flooring; here is the tinder from a little bundle of burnt paper, but not so light as usual, seeming to be steeped in something; and here is—is it the cinder of a small charred and broken log of wood sprinkled with white ashes, or is it coal? Oh, horror, he IS here! And this from which we run away, striking out the light and overturning one another into the street, is all that represents him.

Help, help, help! Come into this house for heaven's sake! Plenty will come in, but none can help. The Lord Chancellor of that court, true to his title in his last act, has died the death of all lord chancellors in all courts and of all authorities in all places under all names soever, where false pretences are made, and where injustice is done. Call the death by any name your Highness will, attribute it to whom you will, or say it might have been prevented how you will, it is the same death eternally—inborn, inbred, engendered in the corrupted humours of the vicious body itself, and that only—spontaneous combustion, and none other of all the deaths that can be died."

I'm not sure if I ever saw anything in Dickens more debated than Krook's spontaneous combustion. And I never saw a death more amusing than Krook's. As far as I can tell most of Dicken's readers had no trouble believing it and never even questioned Krook's unusual death. There were others however, that found it "nonsense". George Henry Lewes, a literature critic at the time writing for "The Leader" acknowledged that the authors have a license to stretch the truth, but said that novelists can’t just ignore the laws of physics. He went on to say that "these circumstances are beyond the limits of acceptable fiction,” He also accused Dickens “of giving currency to a vulgar error". And Dickens responded and he and Lewis argued back and forth in letters for quite some time. Dickens says this in a later preface to the novel:

"There is only one other point on which I offer a word of remark. The possibility of what is called spontaneous combustion has been denied since the death of Mr. Krook; and my good friend Mr. Lewes (quite mistaken, as he soon found, in supposing the thing to have been abandoned by all authorities) published some ingenious letters to me at the time when that event was chronicled, arguing that spontaneous combustion could not possibly be. I have no need to observe that I do not wilfully or negligently mislead my readers and that before I wrote that description I took pains to investigate the subject. There are about thirty cases on record, of which the most famous, that of the Countess Cornelia de Baudi Cesenate, was minutely investigated and described by Giuseppe Bianchini, a prebendary of Verona, otherwise distinguished in letters, who published an account of it at Verona in 1731, which he afterwards republished at Rome. The appearances, beyond all rational doubt, observed in that case are the appearances observed in Mr. Krook's case. The next most famous instance happened at Rheims six years earlier, and the historian in that case is Le Cat, one of the most renowned surgeons produced by France. The subject was a woman, whose husband was ignorantly convicted of having murdered her; but on solemn appeal to a higher court, he was acquitted because it was shown upon the evidence that she had died the death of which this name of spontaneous combustion is given. I do not think it necessary to add to these notable facts, and that general reference to the authorities which will be found at page 30, vol. ii., the recorded opinions and experiences of distinguished medical professors, French, English, and Scotch, in more modern days, contenting myself with observing that I shall not abandon the facts until there shall have been a considerable spontaneous combustion of the testimony on which human occurrences are usually received."

Here are some later cases for you:

"Henry Thomas, a 73-year-old man, was found burned to death in the living room of his council house on the Rassau council estate in Ebbw Vale, south Wales, in 1980. His entire body was incinerated, leaving only his skull and a portion of each leg below the knee. The feet and legs were still clothed in socks and trousers. Half of the chair in which he had been sitting was also destroyed. Police forensic officers decided that the incineration of Thomas was due to the wick effect. His death was ruled 'death by burning', as he had plainly inhaled the contents of his own combustion."

In December 2010, the death of Michael Faherty in County Galway, Ireland, was recorded as "spontaneous combustion" by the coroner. The doctor, Ciaran McLoughlin, made this statement at the inquiry into the death: "This fire was thoroughly investigated and I'm left with the conclusion that this fits into the category of spontaneous human combustion, for which there is no adequate explanation."

"Jack Angel, who had been hospitalized with severe burns, brought a court case against the manufacturer of his hot water heater for three million dollars. He said that he went to check the malfunctioning heater and it blew and scalded him. However, a doctor noted that his body had burned from the inside out, not the outside in. Shortly afterward, he changed his story and said he fell asleep only to wake up with terrible burns all over his body, and sold his story as a survivor of spontaneous human combustion. Was he one of the only people to survive spontaneously combusting?"

"A mentally disabled woman lived with her father, who cared for her. One day he saw a flash out of the corner of his eye, and turned to find her on fire. Despite the flames, she continued to quietly sit in a chair, not reacting and not giving any indication she was in pain. The man's attempts to put the fire out left him with burned hands. The woman lived through the combustion, but slipped into a coma and died shortly afterwards. This indicates one of the strangest parts of human combustion. It takes a very hot flame to reduce a human body to ash. Crematoriums have special chambers designed for it. However, in almost all combustions, there's no burns in the room around the body, indicating that the person simply stayed in one place."

Whether people spontaneously combust or not, it is certainly one of the oddest deaths I've ever read. I wonder why Dickens chose it. Oh, and it's up to you to decide whether to believe the above people burst into flames, I have no opinion on the matter except if Dickens said it it must be true. I'm off for the illustrations. :-)

While reading chapter 30 it suddenly struck me: those philantropic missions are basically no different than the Court of Chancery. Here Mrs. Jellyby is, diving deep into a world full of paperwork, copies of paperwork and copies of those copies, writing letters and affidavits or whatever, while the world goes to ruins around her. Same for those others: their missions make them enstranged to their families, there is no time, nor money left to care for their own, in the case of Mrs. Pardiggle she brings the family curse of the mission onto her kids' heads like so many people did in Jarndyce and Jarndyce ... Well, it suddenly hit me right in the face, this parallel, and I had to get it out of my system too xD

Kim wrote: "She was invited to make a visit and stayed three weeks! Who does that?"

I read somewhere, in a book about Victorian everyday life, that it was quite common in those days among people of a higher status to stay at each other's houses for a few weeks. Transport was a nuisance in those days, and so if you visited people you did it with a vengeance. You were also expected to bring your own servants with you, but also to tip the host's servants generously when you finally took leave - something that would put quite a strain on the purses of a rich man's poorer relations.

And yes, Kim, I did not fail to notice Esther's modesty at the end of the chapter. Such an amiable creature!

I read somewhere, in a book about Victorian everyday life, that it was quite common in those days among people of a higher status to stay at each other's houses for a few weeks. Transport was a nuisance in those days, and so if you visited people you did it with a vengeance. You were also expected to bring your own servants with you, but also to tip the host's servants generously when you finally took leave - something that would put quite a strain on the purses of a rich man's poorer relations.

And yes, Kim, I did not fail to notice Esther's modesty at the end of the chapter. Such an amiable creature!

Kim wrote: " This installment begins with Chapter 30 titled "Esther's Narrative" ..."

Kim wrote: " This installment begins with Chapter 30 titled "Esther's Narrative" ..."You're funny, Kim. I hadn't noticed the commonality (if that's even a word) of Jarndyce's guests each staying for 3 weeks. I've often thought about these long visits when I read Victorian novels. (And it seems as if the trend continues into the early part of the 20th century.) I'm sure Tristram's comment about travel is right on target. He also touches on something important when he talks about servants. The burden of having guests isn't quite so onerous when you have a house like Chatsworth with a staff of maids, butlers, footmen, cooks, etc. Even Jane Austen, who was a bit more middle class by our standards, did a lot of visiting, iirc. Her characters certainly did. I'm with Kim -- come for part of the day if you must, but then leave me to my solitude. (Jarndyce surely used the Growlery to escape from his houseguests, don't you think?)

Mrs. Woodcourt is about as subtle as a cinder block to the head, but Esther doesn't seem to realize how targeted her comments are.

Poor Caddy. What a burden her family is and, no doubt, will continue to be. This sentence - "poor Mr. Jellyby, being very humble and meek, had deferred to Mr. Turveydrop's deportment so submissively that they had become excellent friends" made me cringe. That's not a friendship. But, as they're minor characters, I don't imagine Dickens will explore their relationship too much.

And speaking of cringing... all those do-gooders gathered together in one room. What a pompous, self-righteous bunch!

Kim wrote: "Chapter 31 is titled "Nurse and Patient" ..."

Kim wrote: "Chapter 31 is titled "Nurse and Patient" ..."No one, at this point, should have any doubts as to who Lady Dedlock's stolen baby grew up to be. While Dickens hasn't been explicit, the narrative has certainly given us more than enough circumstantial evidence, now including Jo's mistaking the veiled Esther for the lady he took to the graveyard. Did women really wear veils over their faces so much? Seems like they pop up a lot in this story, and will continue to play a role as we go on.

Jarndyce's gentle and generous but firm guardianship of the trio and his other philanthropy make us love him, but his friendship with Skimpole really does just push me to the limits. Skimpole's wish to put Jo out should have been the last straw. Ass.

Dickens doesn't mention (as far as I know) what disease Jo and Esther get, but the consensus seems to be smallpox. According to the Mayo Clinic website:

Dickens doesn't mention (as far as I know) what disease Jo and Esther get, but the consensus seems to be smallpox. According to the Mayo Clinic website:Smallpox is caused by infection with the variola virus. The virus can be transmitted:

Directly from person to person. Direct transmission of the virus requires fairly prolonged face-to-face contact. The virus can be transmitted through the air by droplets that escape when an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks.

Indirectly from an infected person. In rare instances, airborne virus can spread farther, possibly through the ventilation system in a building, infecting people in other rooms or on other floors.

Via contaminated items. Smallpox can also spread through contact with contaminated clothing and bedding, although the risk of infection from these sources is less common.

As a terrorist weapon, potentially. A deliberate release of smallpox is a remote threat. However, because any release of the virus could spread the disease quickly, government officials have taken numerous precautions to protect against this possibility, such as stockpiling smallpox vaccine....

People who recover from smallpox usually have severe scars, especially on the face, arms and legs. In some cases, smallpox may cause blindness."

It also says that the disease was eradicated in 1980 due to the vaccine, but that some vials of the disease still exist in labs for research (hence the fear of its use as a terrorist weapon).

All this sounds too much like Coronavirus, and suddenly I'm not enjoying my escape into the 19th century nearly as much as I usually do. :-(

Kim wrote: "Chapter 32 is titled "The Appointed Time" ..."

Kim wrote: "Chapter 32 is titled "The Appointed Time" ..."Okay... I'm back to enjoying my mental time-travel. WOW. WOW. WOW. What a chapter!! (Two exclamation points!!)

Whether you buy into the idea of spontaneous combustion or not, this chapter is amazing. I'd love to hear from any Bleak House first-timers in the group. Did you know this was coming? What did you make of the descriptions of the smell and the soot as you were reading? Were you befuddled when you learned the source? Horrified?

I can't really remember, but I was probably a bit confused the first time I read this chapter. But when you know what's coming... Dickens' descriptions of the smell, feel, and even the taste is just, well, delicious. Can you imagine?? Yes, you can! Because Dickens puts us right there in Lincoln's Inn, checking our own sleeves to see if any of the greasy soot has come to rest on us.

Some other thoughts on this chapter....

Snagsby calls Jobling "Sir" over and over again. Yet Jobling works for Snagsby, and he's not gentility. Would this have been correct behaviour? Why does Snagsby seem deferential to someone in his employ?

Jobling says, "here have I been stewing and fuming in this jolly old crib, till I have had the horrors falling on me as thick as hail. Was Dickens the first to use the word "crib" as slang for an apartment? He's such a trendsetter. :-)

Like someone who's enjoying a road trip, I'm not entirely sure how we've gotten to this point - how Guppy, in particular, knows about Hawdon and his letters and has connected them to Lady Dedlock. But the ride has been so much fun that I'm not too concerned about going back and tracing our route on the map.

Yes, that chapter was a lot of fun. I remember that I was utterly confused the first time I read it too! So much confusion, but when you know it's so masterfully done! Especially when you realise that there were hints of the fire-alcohol-combination all throughout the chapters where Krook made an appearance. All so subtle that I cannot bring one in particular to mind at this point, but I have had a lot of fun thinking 'aaaaand another one!' while reading xD

Yes! The breadcrumbs throughout the book have been delightful to come across. Proof that Dickens had plotted this carefully before putting open to paper.

Yes! The breadcrumbs throughout the book have been delightful to come across. Proof that Dickens had plotted this carefully before putting open to paper.

Yes indeed. Chapter 32 is wonderful. The first time I read it I had to go back over it multiple times since I also had never heard of spontaneous combustion. As Jantine and Mary Lou say the breadcrumbs of alcohol, fire, and other bits and pieces have all been laid out by Dickens. The presentation of the smell, sight, and touch and such phrases as “a little thick nauseous pool” and “creeps away down the bricks” are brilliant bits of writing.

The shift from the end of chapter 29 with Lady Dedlock on her knees like “a wild figure” lamenting “O my child, O my child!” to chapter 30’s domestic setting is perfect. Here we have Esther with Woodcourt’s mother who frets about her child and worries about his life and future attachments.

Mrs Woodcourt tells Esther that her son “may not have money, but he always has what is much better - family my dear.” The focus on families, both functional and dysfunctional is becoming more and more important in the novel.

Later in the chapter we read that Caddy is planning to marry. We move through this chapter at a domestic pace. Esther attempts to teach Caddy how to sew only to have Caddy prick her fingers “as much as she had been used to ink them.”

Fingers. Have you noticed the attention that Dickens places on fingers? Each time we have been in Tulkinghorn’s residence Dickens has emphasized the pointing finger of Allegory on the ceiling. Now the renewed attention to Caddy's fingers. Why? Also in this week’s chapters under discussion we will read of Charley’s “nimble little figures” in chapter 31 and how Weevle “holds up his finger in chapter 32. Later in the chapter Mr Guppy runs his hand over Krook’s window-sill and then exclaims “look at my fingers.” For the macabre, of course, Guppy is actually running his fingers over Krook’s remains.

Is there a larger to meaning pointing of fingers, mention of fingers and repetition of a fingers action such as the case with Allegory? There will be much more pointing of fingers both literal and figurative coming soon in the novel. It might be interesting to keep an eye on the separate incidences to see whether Dickens has something greater in play than simple isolated and unconnected incidences.

Mrs Woodcourt tells Esther that her son “may not have money, but he always has what is much better - family my dear.” The focus on families, both functional and dysfunctional is becoming more and more important in the novel.

Later in the chapter we read that Caddy is planning to marry. We move through this chapter at a domestic pace. Esther attempts to teach Caddy how to sew only to have Caddy prick her fingers “as much as she had been used to ink them.”

Fingers. Have you noticed the attention that Dickens places on fingers? Each time we have been in Tulkinghorn’s residence Dickens has emphasized the pointing finger of Allegory on the ceiling. Now the renewed attention to Caddy's fingers. Why? Also in this week’s chapters under discussion we will read of Charley’s “nimble little figures” in chapter 31 and how Weevle “holds up his finger in chapter 32. Later in the chapter Mr Guppy runs his hand over Krook’s window-sill and then exclaims “look at my fingers.” For the macabre, of course, Guppy is actually running his fingers over Krook’s remains.

Is there a larger to meaning pointing of fingers, mention of fingers and repetition of a fingers action such as the case with Allegory? There will be much more pointing of fingers both literal and figurative coming soon in the novel. It might be interesting to keep an eye on the separate incidences to see whether Dickens has something greater in play than simple isolated and unconnected incidences.

Peter wrote: "Yes indeed. Chapter 32 is wonderful. The first time I read it I had to go back over it multiple times since I also had never heard of spontaneous combustion."

Peter wrote: "Yes indeed. Chapter 32 is wonderful. The first time I read it I had to go back over it multiple times since I also had never heard of spontaneous combustion."I came here right after finishing the chapter because I had to ask wait... what... really?

Although I read this book about 20 years ago, I didn't remember this at all, and it is--ahem--memorable enough that I can only assume it was too unbelievable for me to get it the first time around.

"Chops, do you think? Oh! Chops, eh?" Mr. Snagsby sniffs and tastes again. "Well, sir, I suppose it is. But I should say their cook at the Sol wanted a little looking after. She has been burning 'em, sir! And I don't think"—Mr. Snagsby sniffs and tastes again and then spits and wipes his mouth—"I don't think—not to put too fine a point upon it—that they were quite fresh when they were shown the gridiron."

Oh. My. Heavens.

Also out of all the people I would expect to self-combust from their own evil in the book, Krook isn't really the top of the list. He's awful and all, but too powerless?

Well, anyway.

Kim wrote: "Hello everyone,

Kim wrote: "Hello everyone,When Esther asks Caddy what Mr. Jellyby had to say when he found out that she was getting married Caddy says:

"Oh! Poor Pa," said Caddy, "only cried and said he hoped we might get on better than he and Ma had got on. He didn't say so before Prince, he only said so to me. And he said, 'My poor girl, you have not been very well taught how to make a home for your husband, but unless you mean with all your heart to strive to do it, you had better murder him than marry him—if you really love him.'

After that I would have felt sorry for him if I didn't already, it was so sad."

You know, I don't feel sorry for him at all. He seems as ineffective as his wife. You don't get to have it both ways: either we ignore the period gender roles and hierarchy in which case he should have stepped in and helped take care of the kids, or we acknowledge the period gender roles and hierarchy in which case he should have got his wife in order. To imply it's his wife's fault that his life is not worth living is the passive-aggressive icing on the passive cake. I realize nothing is ever that simple but I don't see why Mr. J gets off scot free with his daughter's and the reader's sympathy. Not this reader, sorry.

Julie wrote: "I don't feel sorry for him at all. He seems as ineffective as his wife...."

Julie wrote: "I don't feel sorry for him at all. He seems as ineffective as his wife...."I'm with you, Julie, at least to an extent. His wife is awful, but she's so wrapped up in herself that he could do anything and she wouldn't notice, let alone care. Nothing stopping him from tidying up, taking the children in hand, and, frankly, cutting Mrs. J off from some of the funds she is obviously using for stationery and postage and using that money to get things in order. Lots of feckless husbands in this story.

PS I did enjoy his marital advice to Caddy, though. Doubt she really needed to hear it.

Peter wrote: "Fingers. Have you noticed the attention that Dickens places on fingers? ..."

Peter wrote: "Fingers. Have you noticed the attention that Dickens places on fingers? ..."With the exception of pointing Allegory and one other example to which, I think, we've yet to have our attention drawn, I really hadn't noticed this. But you're right, of course. There's also the mention of "the lady's" fingers, with their rings. Something to point out as we go forward. (Yes, I said it and I'm not sorry. :-) )

Mary Lou wrote: "Mrs. Woodcourt is about as subtle as a cinder block to the head, but Esther doesn't seem to realize how targeted her comments are."

Of course, she wouldn't. She is far too honest, too naive and unscheming. And yet she describes them to us at such length that we cannot fail to notice them ;-)

Of course, she wouldn't. She is far too honest, too naive and unscheming. And yet she describes them to us at such length that we cannot fail to notice them ;-)

These last two instalments have left me speechless. Does Dickens get any better than this? I have enjoyed all your comments, everybody. They really do enhance the experience of reading this rich and complex book. Thanks!

These last two instalments have left me speechless. Does Dickens get any better than this? I have enjoyed all your comments, everybody. They really do enhance the experience of reading this rich and complex book. Thanks!

Ulysse wrote: "These last two installments have left me speechless. Does Dickens get any better than this? ..."

Ulysse wrote: "These last two installments have left me speechless. Does Dickens get any better than this? ..."No. No, he doesn't.

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "Hello everyone,

When Esther asks Caddy what Mr. Jellyby had to say when he found out that she was getting married Caddy says:

"Oh! Poor Pa," said Caddy, "only cried and said he hoped w..."

The more often I read Bleak House the less sympathy I can muster up for Mr. Jellyby, Julie. He is, indeed, one of those people who seem to wallow in their victimhood status because it is so much more comfortable than to actually stand up, beard Mrs. Jellyby in her study and lay it on the line for her that he is no longer going to take it. He might owe this to himself, but that is not saying a lot, and so I'll add that, above all, he owes it to his children because he cannot let his whole family go to seeds because he is unwilling to confront his wife.

Needless to say that I also despise the self-complacent do-gooders who assemble on the occasion of Caddy's wedding and who profess their contempt for anyone who actually minds their own business instead of interfering with that of others on the pretence of helping them. I must say that I see quite a lot of parallels between these hypocrites and modern day hypocrisy in the guise of environmentalism and FFF. There are people who do a lot more for the environment without making so much fuss and taking the moral high ground.

Still, for all my reservations with regard to Mrs. Jellyby, I also find it wrong in her husband to tell his daughter never to have a mission. What this implies is clear: Devote your whole life to your husband and your family. Stay at home. Sew, stitch, cook and look after the children, and don't you dare to try and make something out of your own life. I am afraid that here Dickens himself is speaking through Mr. Jellyby (and we heard similar ideas in Esther). Dickens has a very traditional view of gender roles, a view that was not necessarily shared by all his contemporaries any more, and this is also while he resorts to such blunt stereotypes as Mr. and Mrs. Jellyby, implying that when household matters go wrong, it is not the husband's mistake but that of the wife, if she does not devote her whole time and energy to the domestic circle. Quite clearly, such thinking no longer appeals to modern readers and that's why we regard Mr. Jellyby with more of contempt than of pity.

When Esther asks Caddy what Mr. Jellyby had to say when he found out that she was getting married Caddy says:

"Oh! Poor Pa," said Caddy, "only cried and said he hoped w..."

The more often I read Bleak House the less sympathy I can muster up for Mr. Jellyby, Julie. He is, indeed, one of those people who seem to wallow in their victimhood status because it is so much more comfortable than to actually stand up, beard Mrs. Jellyby in her study and lay it on the line for her that he is no longer going to take it. He might owe this to himself, but that is not saying a lot, and so I'll add that, above all, he owes it to his children because he cannot let his whole family go to seeds because he is unwilling to confront his wife.

Needless to say that I also despise the self-complacent do-gooders who assemble on the occasion of Caddy's wedding and who profess their contempt for anyone who actually minds their own business instead of interfering with that of others on the pretence of helping them. I must say that I see quite a lot of parallels between these hypocrites and modern day hypocrisy in the guise of environmentalism and FFF. There are people who do a lot more for the environment without making so much fuss and taking the moral high ground.

Still, for all my reservations with regard to Mrs. Jellyby, I also find it wrong in her husband to tell his daughter never to have a mission. What this implies is clear: Devote your whole life to your husband and your family. Stay at home. Sew, stitch, cook and look after the children, and don't you dare to try and make something out of your own life. I am afraid that here Dickens himself is speaking through Mr. Jellyby (and we heard similar ideas in Esther). Dickens has a very traditional view of gender roles, a view that was not necessarily shared by all his contemporaries any more, and this is also while he resorts to such blunt stereotypes as Mr. and Mrs. Jellyby, implying that when household matters go wrong, it is not the husband's mistake but that of the wife, if she does not devote her whole time and energy to the domestic circle. Quite clearly, such thinking no longer appeals to modern readers and that's why we regard Mr. Jellyby with more of contempt than of pity.

Mary Lou wrote: "It also says that the disease was eradicated in 1980 due to the vaccine, but that some vials of the disease still exist in labs for research (hence the fear of its use as a terrorist weapon).

All this sounds too much like Coronavirus, and suddenly I'm not enjoying my escape into the 19th century nearly as much as I usually do. :-("

I don't know for sure but I'd say that smallpox was a lot more dangerous, in its deadliness, than the Corona virus. Most people in Europe would have got infected, at one period of their lives, with smallpox, and those scars were a common feature in pre-Victorian faces. Its full scope of deadliness, however, was played out when the Europeans discovered America and went there: The Indian population did not know smallpox, and it is assumed that more than half of the population of America, more than three quarters even, was wiped out by smallpox after the first conquistadores set foot on American soil. De Soto still saw densely populated areas when he roamed Florida - later explorers found a landscape that was barely settled, and so there is good reason to assume that smallpox killed an unbelievably big proportion of the native American population. It is one of the least known catastrophes in history.

All this sounds too much like Coronavirus, and suddenly I'm not enjoying my escape into the 19th century nearly as much as I usually do. :-("

I don't know for sure but I'd say that smallpox was a lot more dangerous, in its deadliness, than the Corona virus. Most people in Europe would have got infected, at one period of their lives, with smallpox, and those scars were a common feature in pre-Victorian faces. Its full scope of deadliness, however, was played out when the Europeans discovered America and went there: The Indian population did not know smallpox, and it is assumed that more than half of the population of America, more than three quarters even, was wiped out by smallpox after the first conquistadores set foot on American soil. De Soto still saw densely populated areas when he roamed Florida - later explorers found a landscape that was barely settled, and so there is good reason to assume that smallpox killed an unbelievably big proportion of the native American population. It is one of the least known catastrophes in history.

Tristram wrote: "I also find it wrong in her husband to tell his daughter never to have a mission. What this implies is clear: Devote your whole life to your husband and your family...."

Tristram wrote: "I also find it wrong in her husband to tell his daughter never to have a mission. What this implies is clear: Devote your whole life to your husband and your family...."You took this bit much more seriously than I did, obviously. Or perhaps it's a difference in our view of the word "mission" in this context. I don't see not having a mission as not having outside interests, and devoting oneself solely to the house and kids. I read it as not having an all-consuming passion to the exclusion of everything else. My direct translation would be, "Don't be like your mother!" but that's, perhaps, too direct (and not theatrical enough) for Dickens.

Re: smallpox and COVID, I was speaking generally. Although had COVID hit 250 years ago, before as much was known about the transmission of diseases and before modern marvels like respirators (and Amazon delivery!), there's no question that it would have been much more devastating, especially in filthy, densely populated cities.

Ulysse wrote: "These last two instalments have left me speechless. Does Dickens get any better than this? I have enjoyed all your comments, everybody. They really do enhance the experience of reading this rich an..."

Ulysse

It is exciting reading the book with so many people contributing. There are always new revelations for all of us. ;-)

Ulysse

It is exciting reading the book with so many people contributing. There are always new revelations for all of us. ;-)

I get severely impatient by the mention of Mr. Jellyby. Can someone shake him up and tell him to man up and be the adult of the house please? Why doesn't he step in, why does Caddy have to do all the work? Even without gender roles - I'm pretty sure that if I'd been like Mrs. Jellyby, my husband would have told me to cut it way before it would cause bankruptcy. I can't imagine him going through that, and then meekly keeping up with paying for her stationery. Even as a stationery addict I say: there are limits. It are the Victorian times, so technically it's his money she keeps squandering, and he just looks on with his head against the wall! Come on!

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Fingers. Have you noticed the attention that Dickens places on fingers? ..."

With the exception of pointing Allegory and one other example to which, I think, we've yet to have our at..."

Yes indeed. Jo is very aware of fingers and the rings that are found on fingers and how, by looking at the hands of a person, you can learn the social position of a person.

It’s like a bit of Sherlock in Bleak House. He would notice the ink stains on Caddy’s finger and the finger that sews and does embroidery work. Fingers and hands speak volumes about a character.

With the exception of pointing Allegory and one other example to which, I think, we've yet to have our at..."

Yes indeed. Jo is very aware of fingers and the rings that are found on fingers and how, by looking at the hands of a person, you can learn the social position of a person.

It’s like a bit of Sherlock in Bleak House. He would notice the ink stains on Caddy’s finger and the finger that sews and does embroidery work. Fingers and hands speak volumes about a character.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I also find it wrong in her husband to tell his daughter never to have a mission. What this implies is clear: Devote your whole life to your husband and your family...."

You took ..."

You are right, Mary Lou: It is always questionable if a person has an all-consuming mission amounting to monomania. It just seemed to me that Dickens was still making a difference as to whether it was a man or a woman who is prey to that mission, but maybe I am reading more into this than Dickens actually intended.

You took ..."

You are right, Mary Lou: It is always questionable if a person has an all-consuming mission amounting to monomania. It just seemed to me that Dickens was still making a difference as to whether it was a man or a woman who is prey to that mission, but maybe I am reading more into this than Dickens actually intended.

Jantine wrote: "I get severely impatient by the mention of Mr. Jellyby. Can someone shake him up and tell him to man up and be the adult of the house please? Why doesn't he step in, why does Caddy have to do all t..."

I still think that Mr. Jellyby is actually quite comfortable with being the apparent victim of his busybody of a wife. It is so much more comfortable for him to think himself wronged than to right himself - and the kids. The only adult person in that household seems to be poor Caddy.

I still think that Mr. Jellyby is actually quite comfortable with being the apparent victim of his busybody of a wife. It is so much more comfortable for him to think himself wronged than to right himself - and the kids. The only adult person in that household seems to be poor Caddy.

Tristram wrote: "I still think that Mr. Jellyby is actually quite comfortable with being the apparent victim of his busybody of a wife. It is so much more comfortable for him to think himself wronged than to right himself - and the kids. The only adult person in that household seems to be poor Caddy. ..."

Tristram wrote: "I still think that Mr. Jellyby is actually quite comfortable with being the apparent victim of his busybody of a wife. It is so much more comfortable for him to think himself wronged than to right himself - and the kids. The only adult person in that household seems to be poor Caddy. ..."I agree with you here. I think he relishes the sympathy he gets for being the long-suffering husband. And as long as Caddy's taking up enough of the slack to get by, he'll probably never man up.

If poor Mr. Jellyby would have stood up for himself and his children and told his wife enough with the Booro whatever, everyone would be saying how awful he is for bossing his wife around making her stop her wonder mission work. Poor r. Jellyby.

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by one of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) certified the global eradication of the disease in 1980. The risk of death after contracting the disease was about 30%, with higher rates among babies. Often those who survived had extensive scarring of their skin, and some were left blind.

The initial symptoms of the disease included fever and vomiting. This was followed by formation of ulcers in the mouth and a skin rash. Over a number of days the skin rash turned into characteristic fluid-filled blisters with a dent in the center. The bumps then scabbed over and fell off, leaving scars. The disease was spread between people or via contaminated objects.

Prevention was achieved mainly through the smallpox vaccine. Once the disease had developed, certain antiviral medication may have helped. Smallpox is estimated to have killed up to 300 million people in the 20th century and around 500 million people in the last 100 years of its existence, including six monarchs. As recently as 1967, 15 million cases occurred a year.

The initial symptoms of the disease included fever and vomiting. This was followed by formation of ulcers in the mouth and a skin rash. Over a number of days the skin rash turned into characteristic fluid-filled blisters with a dent in the center. The bumps then scabbed over and fell off, leaving scars. The disease was spread between people or via contaminated objects.

Prevention was achieved mainly through the smallpox vaccine. Once the disease had developed, certain antiviral medication may have helped. Smallpox is estimated to have killed up to 300 million people in the 20th century and around 500 million people in the last 100 years of its existence, including six monarchs. As recently as 1967, 15 million cases occurred a year.

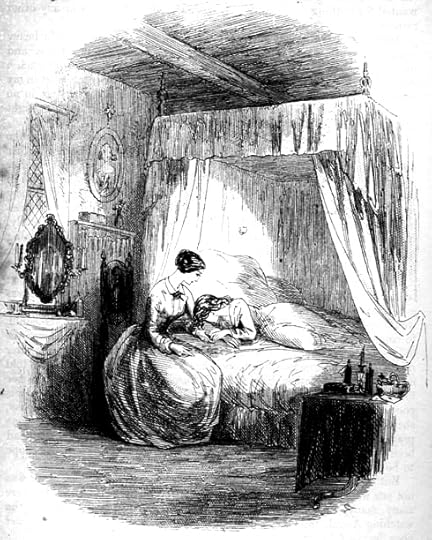

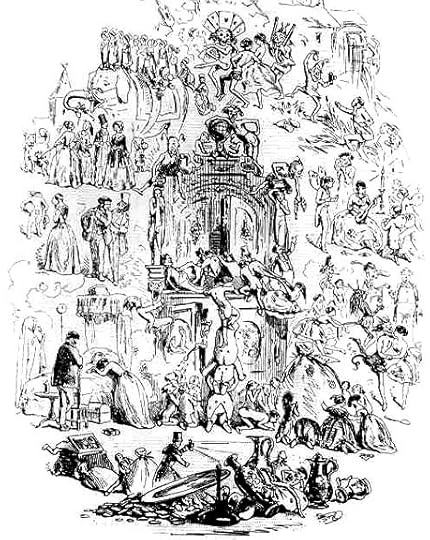

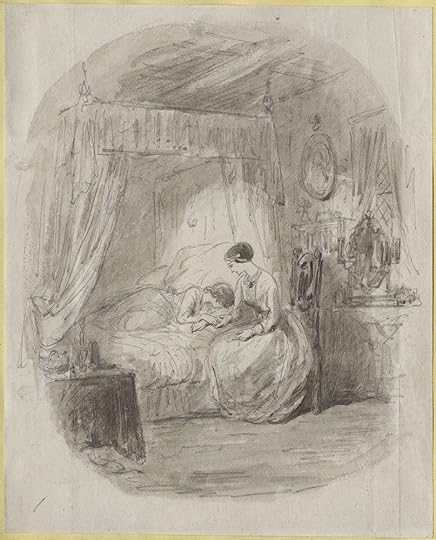

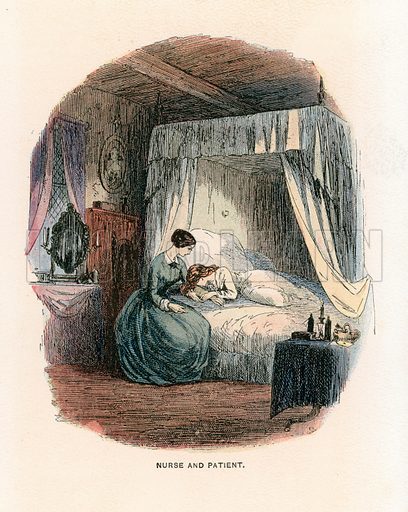

Nurse and Patient

Chapter 31

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

And thus poor Charley sickened and grew worse, and fell into heavy danger of death, and lay severely ill for many a long round of day and night. So patient she was, so uncomplaining, and inspired by such a gentle fortitude that very often as I sat by Charley holding her head in my arms — repose would come to her, so, when it would come to her in no other attitude — I silently prayed to our Father in heaven that I might not forget the lesson which this little sister taught me.

I was very sorrowful to think that Charley's pretty looks would change and be disfigured, even if she recovered — she was such a child with her dimpled face — but that thought was, for the greater part, lost in her greater peril. When she was at the worst, and her mind rambled again to the cares of her father's sick bed and the little children, she still knew me so far as that she would be quiet in my arms when she could lie quiet nowhere else, and murmur out the wanderings of her mind less restlessly. At those times I used to think, how should I ever tell the two remaining babies that the baby who had learned of her faithful heart to be a mother to them in their need was dead!

There were other times when Charley knew me well and talked to me, telling me that she sent her love to Tom and Emma and that she was sure Tom would grow up to be a good man. At those times Charley would speak to me of what she had read to her father as well as she could to comfort him, of that young man carried out to be buried who was the only son of his mother and she was a widow, of the ruler's daughter raised up by the gracious hand upon her bed of death. And Charley told me that when her father died she had kneeled down and prayed in her first sorrow that he likewise might be raised up and given back to his poor children, and that if she should never get better and should die too, she thought it likely that it might come into Tom's mind to offer the same prayer for her. Then would I show Tom how these people of old days had been brought back to life on earth, only that we might know our hope to be restored to heaven!

But of all the various times there were in Charley's illness, there was not one when she lost the gentle qualities I have spoken of. And there were many, many when I thought in the night of the last high belief in the watching angel, and the last higher trust in God, on the part of her poor despised father.

And Charley did not die. She flutteringly and slowly turned the dangerous point, after long lingering there, and then began to mend. The hope that never had been given, from the first, of Charley being in outward appearance Charley any more soon began to be encouraged; and even that prospered, and I saw her growing into her old childish likeness again.

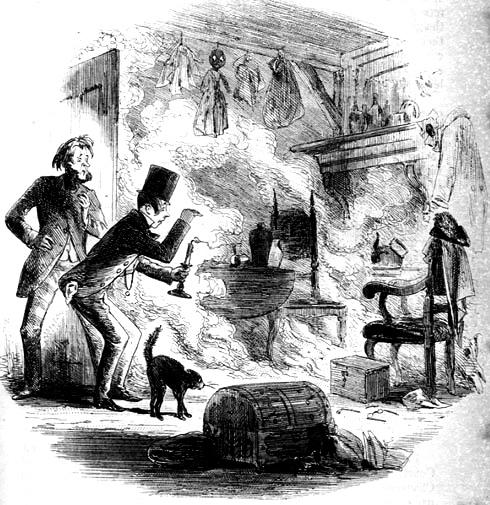

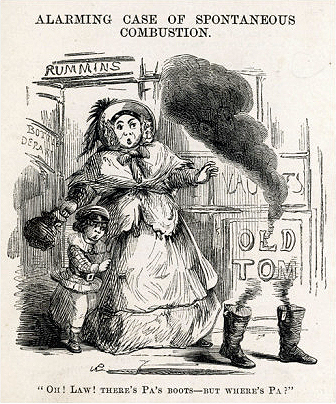

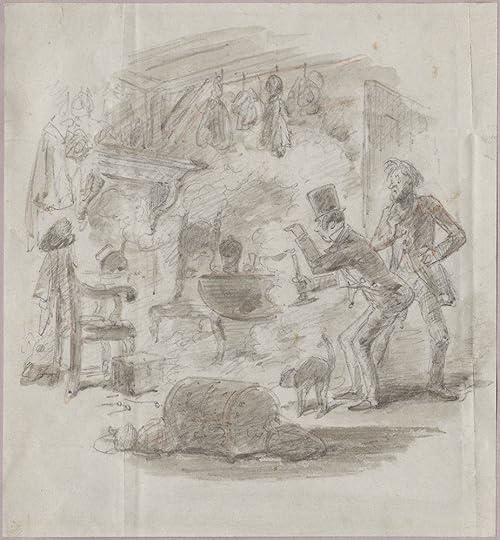

The Appointed Time

Chapter 32

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Guppy takes the light. They go down, more dead than alive, and holding one another, push open the door of the back shop. The cat has retreated close to it and stands snarling, not at them, at something on the ground before the fire. There is a very little fire left in the grate, but there is a smouldering, suffocating vapour in the room and a dark, greasy coating on the walls and ceiling. The chairs and table, and the bottle so rarely absent from the table, all stand as usual. On one chair-back hang the old man's hairy cap and coat.

"Look!" whispers the lodger, pointing his friend's attention to these objects with a trembling finger. "I told you so. When I saw him last, he took his cap off, took out the little bundle of old letters, hung his cap on the back of the chair — his coat was there already, for he had pulled that off before he went to put the shutters up — and I left him turning the letters over in his hand, standing just where that crumbled black thing is upon the floor." . . .

They advance slowly, looking at all these things. The cat remains where they found her, still snarling at the something on the ground before the fire and between the two chairs. What is it? Hold up the light.

Here is a small burnt patch of flooring; here is the tinder from a little bundle of burnt paper, but not so light as usual, seeming to be steeped in something; and here is — is it the cinder of a small charred and broken log of wood sprinkled with white ashes, or is it coal? Oh, horror, he IS here! And this from which we run away, striking out the light and overturning one another into the street, is all that represents him.

Help, help, help! Come into this house for heaven's sake! Plenty will come in, but none can help. The Lord Chancellor of that court, true to his title in his last act, has died the death of all lord chancellors in all courts and of all authorities in all places under all names soever, where false pretences are made, and where injustice is done. Call the death by any name your Highness will, attribute it to whom you will, or say it might have been prevented how you will, it is the same death eternally — inborn, inbred, engendered in the corrupted humours of the vicious body itself, and that only — spontaneous combustion, and none other of all the deaths that can be died.

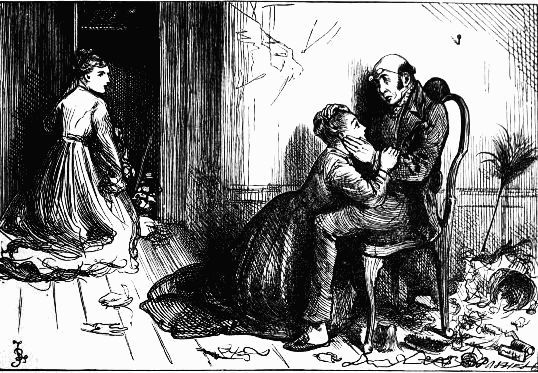

Never have a mission

Chapter 30

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"My dear Caddy!" said Mr. Jellyby, looking slowly round from the wail. It was the first time, I think, I ever heard him say three words together.

"Yes, Pa!" cried Caddy, going to him and embracing him affectionately.

"My dear Caddy," said Mr. Jellyby. "Never have—"

"Not Prince, Pa?" faltered Caddy. "Not have Prince?"

"Yes, my dear," said Mr. Jellyby. "Have him, certainly. But, never have—"

I mentioned in my account of our first visit in Thavies Inn that Richard described Mr. Jellyby as frequently opening his mouth after dinner without saying anything. It was a habit of his. He opened his mouth now a great many times and shook his head in a melancholy manner.

"What do you wish me not to have? Don't have what, dear Pa?" asked Caddy, coaxing him, with her arms round his neck.

"Never have a mission, my dear child."

Mr. Jellyby groaned and laid his head against the wall again, and this was the only time I ever heard him make any approach to expressing his sentiments on the Borrioboolan question. I suppose he had been more talkative and lively once, but he seemed to have been completely exhausted long before I knew him.

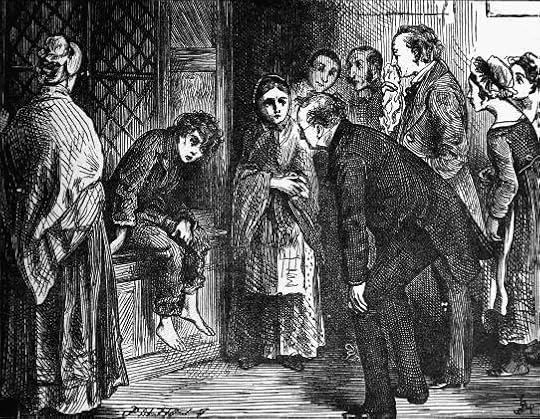

And he shivered in the window-seat with Charley standing by him, like some wounded animal that had been found in a ditch

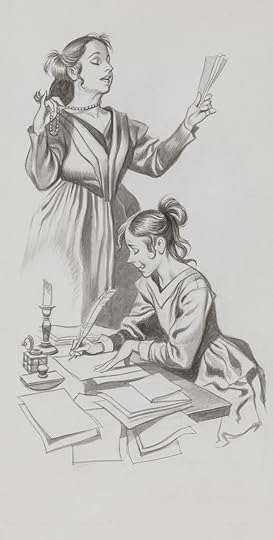

Chapter 31

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Leaving him in the hall for a moment, shrunk into the corner of the window-seat and staring with an indifference that scarcely could be called wonder at the comfort and brightness about him, I went into the drawing-room to speak to my guardian. There I found Mr. Skimpole, who had come down by the coach, as he frequently did without notice, and never bringing any clothes with him, but always borrowing everything he wanted.

They came out with me directly to look at the boy. The servants had gathered in the hall too, and he shivered in the window-seat with Charley standing by him, like some wounded animal that had been found in a ditch.

Peter, I thought you'd enjoy this Frontispiece by Phiz, as far as I can tell there are no spoilers.

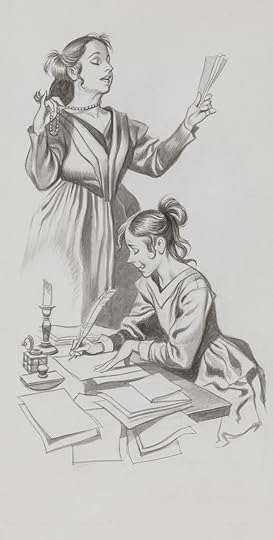

This illustration is by Ron Embleton and says it is of Esther and Ada. This doesn't look like either of them to me, at least I can't think of a situation where they look like this, I do think it may be Mrs. Jellby and Caddy though. What do you think?

Here is another by Ron Embleton. So far I have not found where this goes, if anyone figures it out I'll move it:

Here is another by Ron Embleton. So far I have not found where this goes, if anyone figures it out I'll move it:

Getting ready for the wedding

Chapter 30

Ed Gorey

Text Illustrated:

Caddy was not at all deficient in natural affection for her mother, but mentioned this with tears as an undeniable fact, which I am afraid it was. We were sorry for the poor dear girl and found so much to admire in the good disposition which had survived under such discouragement that we both at once (I mean Ada and I) proposed a little scheme that made her perfectly joyful. This was her staying with us for three weeks, my staying with her for one, and our all three contriving and cutting out, and repairing, and sewing, and saving, and doing the very best we could think of to make the most of her stock. My guardian being as pleased with the idea as Caddy was, we took her home next day to arrange the matter and brought her out again in triumph with her boxes and all the purchases that could be squeezed out of a ten-pound note, which Mr. Jellyby had found in the docks I suppose, but which he at all events gave her. What my guardian would not have given her if we had encouraged him, it would be difficult to say, but we thought it right to compound for no more than her wedding-dress and bonnet. He agreed to this compromise, and if Caddy had ever been happy in her life, she was happy when we sat down to work.

She was clumsy enough with her needle, poor girl, and pricked her fingers as much as she had been used to ink them. She could not help reddening a little now and then, partly with the smart and partly with vexation at being able to do no better, but she soon got over that and began to improve rapidly. So day after day she, and my darling, and my little maid Charley, and a milliner out of the town, and I, sat hard at work, as pleasantly as possible.

I wonder who is who.

As for a three week visit:

How guest Hans Christian Andersen destroyed his friendship with Dickens

The Danish writer’s behaviour on an extended visit killed the authors’ friendship, letters show.

It was not, to say the least, a successful visit. The burgeoning friendship between a pair of literary stars, Charles Dickens and Hans Christian Andersen, had looked set to last. But it could not survive an overlong stay by the Danish author at the British novelist’s family home in Kent. Just how bad things became, on one side at least, has been revealed by a surprisingly frank letter sold at auction on Saturday.

In March 1857, Andersen had announced he was coming over for a short summer stay of a fortnight at the most. Andersen wrote: “[M]y visit is intended for you alone,” and added, “Above all, always leave me a small corner in your heart.”

By the time Andersen’s visit had come to an end, after a full five weeks, Dickens felt compelled to confide to the former prime minister Lord John Russell that the creator of some of the world’s best-loved fairytales was a bad house guest.

“He spoke French like Peter the Wild Boy and English like the Deaf and Dumb School,” complained the great author, making a cruel reference to the well-known story of a feral German boy “Peter”, an ungainly court favourite in Georgian England.

And, according to the reluctant host, Andersen was no better in any other language. “He could not pronounce the name of his own book The Improvisatore, in Italian; and his translatress appears to make out that he can’t speak Danish,” Dickens wrote.

The remarkable letter, which fetched £4,600 and is to stay in London, is just one in an extraordinary trove of correspondence, images and autographs sold by the Suffolk auction house Lacy Scott & Knight on Saturday. The rare documents, including an album sold to an American telephone bidder for £16,000 that contains a scrap of Jane Austen’s handwriting, are all part of a Scottish family collection handed down the generations. There were also letters from Queen Victoria, William Gladstone, Charles Darwin and Sir Walter Scott.

“There is a huge range here, from political figures, to authors and royalty and the provenance of all the lots is excellent,” said Guy Pratt, a book expert and consultant for the auctioneers. “The original collector was well-connected.”

While staying with Charles Dickens he experienced mood swings and wept at unfavourable reviews of his work. Guests, it is sometimes said, like fish, go bad after three days. Andersen’s five weeks with Dickens was clearly pushing it. The famous writers first met in the summer of 1847 at an aristocratic soiree where Andersen had told Dickens he was a big fan, calling him “the greatest writer of our time”.

Some of the Danish tales had just been translated into English and so Andersen was on what might now be described as a promotional tour. In a letter back to friends, Andersen gushed that Dickens “quite answers to the best ideas I had formed of him”.

A couple of weeks later Dickens, one of the most celebrated names in London, left a package containing a note and presentation copies of a dozen of his books at Andersen’s lodgings.

On his return to Denmark, Andersen, noted for his social awkwardness, appears to have become a little obsessed with the dashing English author. For nine years he sent him regular fan letters, along with books for review. When the Dane came to stay in July 1857, it was not during a good time for Dickens, who was considering leaving his wife. His serialisation of Little Dorrit had not gone down well either and he was also feverishly rehearsing his acting role in Wilkie Collins’ The Frozen Deep.

For his part, Andersen found Gad’s Hill, in Higham, Dickens’s country home, too cold, a biographer has noted. And he was also upset that no one was available to shave him in the morning.

Soon his mood swings also became a problem. He lay down on the lawn and wept after receiving a bad review and then cried again when he finally left Gad’s Hill on 15 July.

Dickens was less glum on his guest’s departure, writing on the mirror in the guest room: “Hans Andersen slept in this room for five weeks — which seemed to the family AGES!” The author is already known to have written to his friend William Jerdan six days later complaining about Andersen’s oddness.

“Whenever he got to London, he got into wild entanglements of Cabs and Sherry, and never seemed to get out of them again until he came back here, and cut out paper into all sorts of patterns, and gathered the strangest little nosegays in the woods,” he wrote.

The correspondence between the pair died out soon afterwards. But the brief relationship may not have proved entirely fruitless. Some scholars have suggested that Andersen, later described by Dickens’s daughter Kate as “a bony bore”, could have inspired the character of the toadying Uriah Heep in David Copperfield.

How guest Hans Christian Andersen destroyed his friendship with Dickens

The Danish writer’s behaviour on an extended visit killed the authors’ friendship, letters show.

It was not, to say the least, a successful visit. The burgeoning friendship between a pair of literary stars, Charles Dickens and Hans Christian Andersen, had looked set to last. But it could not survive an overlong stay by the Danish author at the British novelist’s family home in Kent. Just how bad things became, on one side at least, has been revealed by a surprisingly frank letter sold at auction on Saturday.

In March 1857, Andersen had announced he was coming over for a short summer stay of a fortnight at the most. Andersen wrote: “[M]y visit is intended for you alone,” and added, “Above all, always leave me a small corner in your heart.”

By the time Andersen’s visit had come to an end, after a full five weeks, Dickens felt compelled to confide to the former prime minister Lord John Russell that the creator of some of the world’s best-loved fairytales was a bad house guest.

“He spoke French like Peter the Wild Boy and English like the Deaf and Dumb School,” complained the great author, making a cruel reference to the well-known story of a feral German boy “Peter”, an ungainly court favourite in Georgian England.

And, according to the reluctant host, Andersen was no better in any other language. “He could not pronounce the name of his own book The Improvisatore, in Italian; and his translatress appears to make out that he can’t speak Danish,” Dickens wrote.

The remarkable letter, which fetched £4,600 and is to stay in London, is just one in an extraordinary trove of correspondence, images and autographs sold by the Suffolk auction house Lacy Scott & Knight on Saturday. The rare documents, including an album sold to an American telephone bidder for £16,000 that contains a scrap of Jane Austen’s handwriting, are all part of a Scottish family collection handed down the generations. There were also letters from Queen Victoria, William Gladstone, Charles Darwin and Sir Walter Scott.

“There is a huge range here, from political figures, to authors and royalty and the provenance of all the lots is excellent,” said Guy Pratt, a book expert and consultant for the auctioneers. “The original collector was well-connected.”

While staying with Charles Dickens he experienced mood swings and wept at unfavourable reviews of his work. Guests, it is sometimes said, like fish, go bad after three days. Andersen’s five weeks with Dickens was clearly pushing it. The famous writers first met in the summer of 1847 at an aristocratic soiree where Andersen had told Dickens he was a big fan, calling him “the greatest writer of our time”.

Some of the Danish tales had just been translated into English and so Andersen was on what might now be described as a promotional tour. In a letter back to friends, Andersen gushed that Dickens “quite answers to the best ideas I had formed of him”.

A couple of weeks later Dickens, one of the most celebrated names in London, left a package containing a note and presentation copies of a dozen of his books at Andersen’s lodgings.

On his return to Denmark, Andersen, noted for his social awkwardness, appears to have become a little obsessed with the dashing English author. For nine years he sent him regular fan letters, along with books for review. When the Dane came to stay in July 1857, it was not during a good time for Dickens, who was considering leaving his wife. His serialisation of Little Dorrit had not gone down well either and he was also feverishly rehearsing his acting role in Wilkie Collins’ The Frozen Deep.

For his part, Andersen found Gad’s Hill, in Higham, Dickens’s country home, too cold, a biographer has noted. And he was also upset that no one was available to shave him in the morning.

Soon his mood swings also became a problem. He lay down on the lawn and wept after receiving a bad review and then cried again when he finally left Gad’s Hill on 15 July.

Dickens was less glum on his guest’s departure, writing on the mirror in the guest room: “Hans Andersen slept in this room for five weeks — which seemed to the family AGES!” The author is already known to have written to his friend William Jerdan six days later complaining about Andersen’s oddness.

“Whenever he got to London, he got into wild entanglements of Cabs and Sherry, and never seemed to get out of them again until he came back here, and cut out paper into all sorts of patterns, and gathered the strangest little nosegays in the woods,” he wrote.