The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Hard Times

>

Book 1 Chapters 9-10

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Hard Times 1-10

Stephen Blackpool

“He held no station among the Hands who could talk much better than he … He was a good power-loom weaver, and a man of perfect integrity.”

Another chapter and another character is introduced to the reader. Stephen works in Bounderby’s factory. Dickens calls Stephen a man “of perfect integrity.” High praise indeed. Let’s see how Stephen has earned this high praise.

First, however, let’s pause for a moment. We are told that “the lights of the Great factories … looked, when illuminated, like Fairy palaces.” Seeing anything from a distance is often deceiving, so perhaps we should be careful with our first look at Stephen. Will he pass the test of integrity? Also, why might Dickens compare the massive factories of Coketown to “Fairy palaces?” Surely there must be some reason for such a comparison.

We first meet Stephen as he stands in the rain waiting for someone named Rachael. We are told he knew her well. After some wait he sees her. She is described as a person with a “quiet oval face … gentle eyes [and] shiny black hair.” She is about 35 years old. Stephen, we are told, is 40. As we listen to their conversation it is evident that they have known each other for some time, and there is a clear tenderness in their manner towards each other. They talk about the law and it becomes evident that their attraction towards each other is being stifled in some way. To Stephen, the ways of the world are a “muddle” (a word which I love and have adopted into my own vocabulary). As for Rachael, did you notice that on three separate occasions in this chapter she gently touches Stephen?

Rachael’s room is described in a very powerful and yet subtle vignette. We read that the local undertaker “turned a handsome sum” from the neighbourhood. In fact, we read, he keeps a “black ladder” by which those who die in their rooms can be “slide out of this world by the windows.” What a ghastly anecdote to slip into the parting of Rachael and Stephen. First, I imagine such a set up did occur in some areas where there was a high mortality rate. Can you imagine walking down a street and seeing such a ladder propped up on a building? Or worse, seeing a dead person being lowered down from a window rather than carried down the stairs? Second, does this ladder in anyway foreshadow what may happen to either Rachael or Stephen? Finally, if we think back to our reading of the two articles written by Dickens in Household Words, we will recall how much of his writing in that journal was very raw and graphic. Here, in the novel, we see how Dickens has certainly geared back on the graphic details of a person’s death but still kept the indignity of the treatment towards the dead in focus to his readers.

Stephen enters his room which we are told was a room “not unacquainted with the black ladder under various tenants” and though “the atmosphere was tainted, the room was clean.” In his room Stephen discovers “a disabled, drunken creature… a creature so foul to look at, in her tatters, stains, and splashes … in her moral infamy, that it was a shameful thing ever to see her.” It is Stephen’s wife. He is horrified. As our chapter ends she commands the bed, falls asleep, and is soon snoring. Even with this grotesque character who has returned into his life, we see Stephen’s kindness. He covers her with a blanket.

For such a brief chapter we have encountered much to reflect upon. Did you note that our chapter began with a reference to the factories which are described as looking like “Fairy palaces.” The chapter ends in a room where many people in the past have died, and where there is, at present, a hag, an ogre, an evil presence in attendance. Fairy palaces and horrendous hovels. A brilliant balance and contrast. Another contrast is the gentle, quiet, mature beauty of Rachael to that of Stephen’s wife whose bonnet is described as “a dunghill-fragment.” In the middle of these extremes is Stephen Blackpool.

Thoughts

What is your opinion of how Dickens has presented this chapter?

In this chapter there is much conflict that may brew up in the future. What are some of the obvious and some of the subtle conflicts that are presented?

Stephen Blackpool

“He held no station among the Hands who could talk much better than he … He was a good power-loom weaver, and a man of perfect integrity.”

Another chapter and another character is introduced to the reader. Stephen works in Bounderby’s factory. Dickens calls Stephen a man “of perfect integrity.” High praise indeed. Let’s see how Stephen has earned this high praise.

First, however, let’s pause for a moment. We are told that “the lights of the Great factories … looked, when illuminated, like Fairy palaces.” Seeing anything from a distance is often deceiving, so perhaps we should be careful with our first look at Stephen. Will he pass the test of integrity? Also, why might Dickens compare the massive factories of Coketown to “Fairy palaces?” Surely there must be some reason for such a comparison.

We first meet Stephen as he stands in the rain waiting for someone named Rachael. We are told he knew her well. After some wait he sees her. She is described as a person with a “quiet oval face … gentle eyes [and] shiny black hair.” She is about 35 years old. Stephen, we are told, is 40. As we listen to their conversation it is evident that they have known each other for some time, and there is a clear tenderness in their manner towards each other. They talk about the law and it becomes evident that their attraction towards each other is being stifled in some way. To Stephen, the ways of the world are a “muddle” (a word which I love and have adopted into my own vocabulary). As for Rachael, did you notice that on three separate occasions in this chapter she gently touches Stephen?

Rachael’s room is described in a very powerful and yet subtle vignette. We read that the local undertaker “turned a handsome sum” from the neighbourhood. In fact, we read, he keeps a “black ladder” by which those who die in their rooms can be “slide out of this world by the windows.” What a ghastly anecdote to slip into the parting of Rachael and Stephen. First, I imagine such a set up did occur in some areas where there was a high mortality rate. Can you imagine walking down a street and seeing such a ladder propped up on a building? Or worse, seeing a dead person being lowered down from a window rather than carried down the stairs? Second, does this ladder in anyway foreshadow what may happen to either Rachael or Stephen? Finally, if we think back to our reading of the two articles written by Dickens in Household Words, we will recall how much of his writing in that journal was very raw and graphic. Here, in the novel, we see how Dickens has certainly geared back on the graphic details of a person’s death but still kept the indignity of the treatment towards the dead in focus to his readers.

Stephen enters his room which we are told was a room “not unacquainted with the black ladder under various tenants” and though “the atmosphere was tainted, the room was clean.” In his room Stephen discovers “a disabled, drunken creature… a creature so foul to look at, in her tatters, stains, and splashes … in her moral infamy, that it was a shameful thing ever to see her.” It is Stephen’s wife. He is horrified. As our chapter ends she commands the bed, falls asleep, and is soon snoring. Even with this grotesque character who has returned into his life, we see Stephen’s kindness. He covers her with a blanket.

For such a brief chapter we have encountered much to reflect upon. Did you note that our chapter began with a reference to the factories which are described as looking like “Fairy palaces.” The chapter ends in a room where many people in the past have died, and where there is, at present, a hag, an ogre, an evil presence in attendance. Fairy palaces and horrendous hovels. A brilliant balance and contrast. Another contrast is the gentle, quiet, mature beauty of Rachael to that of Stephen’s wife whose bonnet is described as “a dunghill-fragment.” In the middle of these extremes is Stephen Blackpool.

Thoughts

What is your opinion of how Dickens has presented this chapter?

In this chapter there is much conflict that may brew up in the future. What are some of the obvious and some of the subtle conflicts that are presented?

In this short while we also have come across quite some unhappy marriages. There are:

- Mr. and Mrs. Gradgrind, where she has been ground into chronic incapability (both physical and mental, she has been ground into being incapable to feel empathy it seems)

- Mrs. Sparsit, who has been brought down and into debt by her late husband, and who now is the often humiliated housekeeper of Bounderby. Which isn't exactly and legally a marriage, but close enough that it counts as another one in my opinion.

- And then there is Stephen Blackpool and his ogre of a wife.

I'm pretty sure there will be at least one more unhappy marriage, that has been foreshadowed quite a lot already. The only one where people loved each other this far was between Mr. Jupe and his late wife.

Tom gives his sister, the only one who loves him unconditionally, up for his own gain. Indeed, to me it felt like pimping too. I hope it will show that being that practical and selfish does not hold up in the end though.

- Mr. and Mrs. Gradgrind, where she has been ground into chronic incapability (both physical and mental, she has been ground into being incapable to feel empathy it seems)

- Mrs. Sparsit, who has been brought down and into debt by her late husband, and who now is the often humiliated housekeeper of Bounderby. Which isn't exactly and legally a marriage, but close enough that it counts as another one in my opinion.

- And then there is Stephen Blackpool and his ogre of a wife.

I'm pretty sure there will be at least one more unhappy marriage, that has been foreshadowed quite a lot already. The only one where people loved each other this far was between Mr. Jupe and his late wife.

Tom gives his sister, the only one who loves him unconditionally, up for his own gain. Indeed, to me it felt like pimping too. I hope it will show that being that practical and selfish does not hold up in the end though.

Jantine wrote: "In this short while we also have come across quite some unhappy marriages. There are:

- Mr. and Mrs. Gradgrind, where she has been ground into chronic incapability (both physical and mental, she ha..."

Hi Jantine

Absolutely. You have raised an important element in the plot structure of Hard Times. Marriage, personal relationships, and the concept of commitment and fidelity will all weave themselves throughout the novel.

- Mr. and Mrs. Gradgrind, where she has been ground into chronic incapability (both physical and mental, she ha..."

Hi Jantine

Absolutely. You have raised an important element in the plot structure of Hard Times. Marriage, personal relationships, and the concept of commitment and fidelity will all weave themselves throughout the novel.

The only comment I was left with after finishing chapter 9 was this: Tom is a jerk.

The only comment I was left with after finishing chapter 9 was this: Tom is a jerk. Of course, Peter gives us much more to consider than that obvious statement. The fairy lights of Coketown seem to me to be more of an acknowledgement by Dickens that one can find whimsy, beauty, wonder, etc. even in the worst of places if one looks hard enough - or uses one's imagination.

Nine oils = nine muses.... interesting idea. I'm keeping an open mind. :-)

As far as this being a female-centered novel, we have Sissy and Louisa who definitely seem to be central figures. Mrs. Sparsit and Mrs. Gradgrind seem to me to be more peripheral, not unlike Mrs. Varden and Miggs from Barnaby Rudge. Youth v. age could similarly be a theme, with the young ladies pitted against their elders.

But I think the most significant conflict will continue to be facts v. imagination, what is v. what could be. Without imagination and creativity we have no innovation. There must be - dare I say it? - a marriage between facts and fancy.

Re: Stephen -- Peter, you noted the one quote I highlighted as I read, that being

a man of perfect integrity.

Really, what more is there to say of a man? Does anything else really matter? I suppose there are other attributes such as kindness, but if someone is kind without integrity, can anything they say truly be trusted? This description of being a man of perfect integrity was very significant for me.

When Stephen covered his wife, I also thought it was a kindness...initially. But then Dickens says, "...as if his hands were not enough to hide her, even in the darkness. causing me to think that it was less an act of affection or kindness, and more than Stephen was repulsed by even her silhouette in the darkness.

If this was (were? I never get that right...) a fairy tale, Rachael would seem to be our downtrodden princess-in-waiting, and Mrs. Blackpool our wicked witch. And while Stephen doesn't match the description of your typical Prince Charming, he is a man of perfect integrity.

Peter, I like your take on the nine oils as an elixir for Coketown. Nine oils has a magical, symbolic sound to it.

Peter, I like your take on the nine oils as an elixir for Coketown. Nine oils has a magical, symbolic sound to it. "A man of perfect integrity." That phrase stood out to me too. I know from reading Dickens that whatever the narrator says is Fact. Therefore, I trust that Stephen is indeed a good man. He might even be the prince in the fairy tale.

The narrator also says that there was a "mistake" in Stephen's life where, "somebody else had become possessed of his roses, and he had become possessed of the same somebody else’s thorns in addition to his own." Who's thorns does he have, and what is the "mistake" that needs to be rectified?

Alissa, I didn't make the link to that other person being an actual person or the mistake being an actual mistake before. I think it might refer to his wife though? Through integer Stephen she is certain that she is entitled to a roof and a bed somewhere, even if she is not the one working to pay them, while he cannot pursue that fairy tale princess because of the ogre sleeping in his bed. It would be his own mistake though, no matter how integer he is.

Peter you got me to look up two things in one thread. First there is nine oils:

In the 19th century, the nine oils was a preparation, or liniment, which was rubbed into the skin to relieve aches, such as over bruises. The "nine oils" were apparently developed in veterinary medicine, for treating horses, but later was adopted for human medical use.

According to one 19th-century druggists' book, oils used in the preparation included:

train oil; that is, whale oil or the oil of the blubber of another marine mammal

oil of turpentine

oil of bricks, the oil obtained by the distillation of pieces of brick saturated with rapeseed oil or olive oil

oil of amber

spirit of camphor

Barbados tar, a kind of greenish petroleum found in Barbados

oil of vitriol; that is, sulfuric acid

However, it is certain that many "nine oils" preparations did not contain these ingredients, and in fact it is possible that the name "nine oils" never referred to any specific combination of compounds. The writer James Greenwood, in 1883, put these words in the mouth of the street-doctor "Dr. Quackinbosh", in his series of articles Toilers in London, by One of the Crowd, originally serialized in the Daily Telegraph:

When I first started I worked Woolwich with my "miraculous Nine Oils." Men who work at heavy lifting and hauling, and are likely to get strains and ricks of the back, have a superstitious belief in the "Nine Oils." It is the same wherever you go. What are they? what, the original Nine? Blessed if I know, nor they don't know either. But that don't make any difference. I used to give 'em one – sperm oil – and call it the Nines.

Then there was the word muddle:

1.

bring into a disordered or confusing state.

"I fear he may have muddled the message"

2.

mix (a drink) or stir (an ingredient) into a drink.

"muddle the kiwi slices with the sugar"

3.

an untidy and disorganized state or collection.

"the finances were in a muddle"

In the 19th century, the nine oils was a preparation, or liniment, which was rubbed into the skin to relieve aches, such as over bruises. The "nine oils" were apparently developed in veterinary medicine, for treating horses, but later was adopted for human medical use.

According to one 19th-century druggists' book, oils used in the preparation included:

train oil; that is, whale oil or the oil of the blubber of another marine mammal

oil of turpentine

oil of bricks, the oil obtained by the distillation of pieces of brick saturated with rapeseed oil or olive oil

oil of amber

spirit of camphor

Barbados tar, a kind of greenish petroleum found in Barbados

oil of vitriol; that is, sulfuric acid

However, it is certain that many "nine oils" preparations did not contain these ingredients, and in fact it is possible that the name "nine oils" never referred to any specific combination of compounds. The writer James Greenwood, in 1883, put these words in the mouth of the street-doctor "Dr. Quackinbosh", in his series of articles Toilers in London, by One of the Crowd, originally serialized in the Daily Telegraph:

When I first started I worked Woolwich with my "miraculous Nine Oils." Men who work at heavy lifting and hauling, and are likely to get strains and ricks of the back, have a superstitious belief in the "Nine Oils." It is the same wherever you go. What are they? what, the original Nine? Blessed if I know, nor they don't know either. But that don't make any difference. I used to give 'em one – sperm oil – and call it the Nines.

Then there was the word muddle:

1.

bring into a disordered or confusing state.

"I fear he may have muddled the message"

2.

mix (a drink) or stir (an ingredient) into a drink.

"muddle the kiwi slices with the sugar"

3.

an untidy and disorganized state or collection.

"the finances were in a muddle"

I wonder when Stephen's wife got so horrible. I would think she wasn't that way when they got married or he wouldn't have married her.

"It Would Be A Fine Thing To Be You, Miss Louisa!"

Chapter 9

Harry French

Illustration for Dickens's Hard Times for These Times in the British Household Edition 1875

I can't say I agree with her statement, by the way.

Text Illustrated:

‘It would be a fine thing to be you, Miss Louisa!’ she said, one night, when Louisa had endeavoured to make her perplexities for next day something clearer to her.

‘Do you think so?’

‘I should know so much, Miss Louisa. All that is difficult to me now, would be so easy then.’

‘You might not be the better for it, Sissy.’

Sissy submitted, after a little hesitation, ‘I should not be the worse, Miss Louisa.’ To which Miss Louisa answered, ‘I don’t know that.’

There had been so little communication between these two—both because life at Stone Lodge went monotonously round like a piece of machinery which discouraged human interference, and because of the prohibition relative to Sissy’s past career—that they were still almost strangers. Sissy, with her dark eyes wonderingly directed to Louisa’s face, was uncertain whether to say more or to remain silent.

‘You are more useful to my mother, and more pleasant with her than I can ever be,’ Louisa resumed. ‘You are pleasanter to yourself, than I am to myself.’

‘But, if you please, Miss Louisa,’ Sissy pleaded, ‘I am—O so stupid!’

Louisa, with a brighter laugh than usual, told her she would be wiser by-and-by.

‘You don’t know,’ said Sissy, half crying, ‘what a stupid girl I am. All through school hours I make mistakes. Mr. and Mrs. M’Choakumchild call me up, over and over again, regularly to make mistakes. I can’t help them. They seem to come natural to me.’

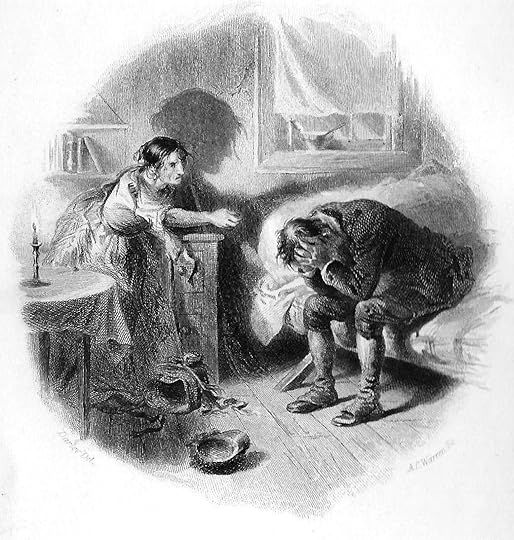

"'Heaven's Mercy, Woman!' He Cried, Falling Farther Off From The Figure. 'Has Thou Come Back Agen?'"

Chapter 10

Harry French

Illustration for Dicken's "Hard Times for These Times in the British Household Edition 1870's

Commentary:

"The high factory chimneys fed by the industrial furnaces of Dickens's Coketown cast no shadows throughout Harry French's programme of twenty illustrations for the British Household Edition of Hard Times. Even Stephen Blackpool's "disabled, drunken" wife seems to have been filtered by French's essentially middle-class pictorial imagination, so that her hair is scarcely "tangled" and her dress hardly the "tatters" that Dickens specifies in his description of a woman reduced to level of a "creature" through substance abuse and addiction. However, Stephen's beard, top hat, and tail-coat are plausible, given the historical context in which the artist drew them. Even the working class attempted to maintain a respectable appearance by shopping in second-hand clothing shops, acquiring what had been some seasons previous fashionable and what still had considerable wear left; we note that Stephen's coat seems somewhat out-of-date compared to the fuller frock-coats worn by Gradgrind and Bounderby.

Stephen's beard (purely the artist's invention) may reflect the style that came in after the Crimean War, when non-military gentlemen of fashion attempted to emulate the military beard: "As to whiskers, men were usually clean-shaven until the 1850s, when the soldiers returned from the Crimean War with beards. . . . . Soon, however, every respectable man sprouted one". With respect to both beards and clothing, the lower classes usually attempted to follow the fashions set by the upper and then the upper-middle classes."

I don't know, he looks like the captain of a ship to me.

Stephen and Rachael

Chapter 10

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Commentary:

Eytinge has chosen to realize that tender, initial meeting of the middle-aged factory-workers in the street outside the mill (left) just after late-afternoon shift-change. Eytinge appropriately shows Rachael as still attractive, despite the severity of factory work, and Stephen as prematurely grey, careworn, and almost numb, standing in the rain after hours of service to the implacable machine, driven by steam engines whose nine chimneys dominate the backdrop.

C. S. Reinhart would later introduce Stephen in the context of his marital difficulties in "Heaven's Mercy, Woman! . . . . Hast Thou Come Back Again!", shocking the reader with the animalistic woman who repeatedly despoils him; although his view of the same moment is less graphic, Harry French again references Stephen's unfortunate domestic circumstances and his victimization by his wife in "'Heaven's Mercy, Woman!' He Cried, Falling Farther Off From The Figure. 'Has Thou Come Back Agen?'" The passage of description that Eytinge is realizing in the cloth-capped figure of Stephen occurs much earlier, in chapter 10:

". . . in the last close nook of this great exhausted receiver, where the chimneys, for want of air to make a draught, were built in an immense variety of stunted and crooked shapes, as though every house put out a sign of the kind of people who might be expected to be born in it; among the multitude of Coketown, generically called "the Hands," — a race who would have found mere favour with some people, if Providence had seen fit to make them only hands, or, like the lower creatures of the seashore, only hands and stomachs — lived a certain Stephen Blackpool, forty years of age.

Stephen looked older, but he had had a hard life. It is said that every life has its roses and thorns; there seemed, however, to have been a misadventure or mistake in Stephen's case, whereby somebody else had become possessed of his roses, and he had become possessed of the same somebody else's thorns in addition to his own.

He had known, to use his words, a peck of trouble. He was usually called Old Stephen, in a kind of rough homage to the fact. A rather stooping man, with a knitted brow, a pondering expression of face, and a hard-looking head sufficiently capacious, on which his iron-grey hair lay long and thin, Old Stephen might have passed for a particularly intelligent man in his condition. Yet he was not. He took no place among those remarkable "Hands," who, piecing together their broken intervals of leisure through many years, had mastered difficult sciences, and acquired a knowledge of most unlikely things. He held no station among the Hands who could make speeches and carry on debates. Thousands of his compeers could talk much better than he, at any time. He was a good power-loom weaver, and a man of perfect integrity. What more he was, or what else he had in him, if anything, let him show for himself."

However, Eytinge has chosen not merely to realize Dickens's description of Old Stephen but also to capture the moment at which he is relieved to catch Rachael in the street:

"But, he had not gone the length of three streets, when he saw another of the shawled figures in advance of him, at which he looked so keenly that perhaps its mere shadow indistinctly reflected on the wet pavement, — if he could have seen it without the figure itself moving along from lamp to lamp, brightening and fading as it went, — would have been enough to tell him who was there. Making his pace at once much quicker and much softer, he darted on until he was very near this figure, then fell into his former walk, and called "Rachael!"

She turned, being then in the brightness of a lamp; and raising her hood a little, showed a quiet oval face, dark and rather delicate, irradiated by a pair of very gentle eyes, and further set off by the perfect order of her shining black hair. It was not a face in its first bloom; she was a woman five-and-thirty years of age."

"Stephen Blackpool"

Chapter 10

F.O.C. Darley

For Dickens's Hard Times, Household Edition (1862)

Text Illustrated:

"Heaven's mercy, woman!" he cried, falling farther off from the figure. "Hast thou come back again!"

Such a woman! A disabled, drunken creature, barely able to preserve her sitting posture by steadying herself with one begrimed hand on the floor, while the other was so purposeless in trying to push away her tangled hair from her face, that it only blinded her the more with the dirt upon it. A creature so foul to look at, in her tatters, stains and splashes, but so much fouler than that in her moral infamy, that it was a shameful thing even to see her.

After an impatient oath or two, and some stupid clawing of herself with the hand not necessary to her support, she got her hair away from her eyes sufficiently to obtain a sight of him. Then she sat swaying her body to and fro, and making gestures with her unnerved arm, which seemed intended as the accompaniment to a fit of laughter, though her face was stolid and drowsy.

"Eigh, lad? What, yo'r there?" Some hoarse sounds meant for this, came mockingly out of her at last; and her head dropped forward on her breast.

"Back agen?" she screeched, after some minutes, as if he had that moment said it. "Yes! And back agen. Back agen ever and ever so often. Back? Yes, back. Why not?"

Roused by the unmeaning violence with which she cried it out, she scrambled up, and stood supporting herself with her shoulders against the wall; dangling in one hand by the string, a dunghill-fragment of a bonnet, and trying to look scornfully at him.

"I'll sell thee off again, and I'll sell thee off again, and I'll sell thee off a score of times!" she cried, with something between a furious menace and an effort at a defiant dance. "Come awa' from th' bed!" He was sitting on the side of it, with his face hidden in his hands. "Come awa' from 't. 'Tis mine, and I've a right to 't!"

Commentary

The scenes of life in an industrial town in the original 1854 weekly serial are based on Dickens's observations during the Preston Strike in the North of England, a few days' experiences transformed into Hard Times For These Times. The fortunes of a secondary character in the novel, the archetypal working man saddled with an alcohol-and-laudanum addicted wife (left), as the subject for his initial illustration demonstrates Darley's understanding of the "industrial" nature of the story.

Darley's dramatic study of the long-suffering Stephen and his incubus is not based on earlier illustrations, since no illustrated edition of the 1854 novel, serialized in Household Words existed at the time that James G. Gregory, the New York publisher, commissioned Felix Octavius Carr Darley to provide the frontispieces for the majority of the fifty-five volumes in the so-called "Household Edition," which his firm began to publish in 1861, six years prior to the Ticknor-Fields Diamond Edition, illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr., and seven years prior to the Chapman and Hall Illustrated Library Edition, with its elegant but slight series of illustrations by Fred Walker. In fact, this Darley photogravure, with the ominous shadow of Mrs. Blackpool dominating the room, anticipates realizations of that same relationship by Fred Walker, C. S. Rinehart, and Harry French. The spartan, orderly room of the working-class hero of the novel, with the few books representing his attempts at self-education and self-help, contrasts the chaotic misery that the slatternly wife (left) without a Christian name inflicts upon the prostrate Stephen (right), whose despair Darley masterfully conveys through Stephen's posture.

The other properties — the "writings . . . on an old bureau in the corner," the candle on the three-legged table, the bare floorboards, and the few sticks of furniture — come directly from the text; to these Darley has significantly added the wife's bonnet and Stephen's cap on the floor. However, the effectiveness of the illustration depends upon the menacing shadow of Mrs. Blackpool's arm that extents her own reach right across the despairing Stephen and, as it were, into his future as she threatens to pawn his belongings again and again so that she can procure alcohol and opium.

Chapter 10

C. S. Reinhart

Illustration for Charles Dickens's Hard Times, which appeared in American Household Edition, 1870.

Commentary:

"Having bidden his friend Rachael goodnight after their day at the factory, Stephen, his cap still on, enters his room above a little shop and lights a candle to discover that his slatternly wife, an opium addict and alcoholic, has returned. Significantly, in the text he "stumbles" against her (presumably she is on the floor), for she is the stumbling block to his relationship with Rachael and to his having a normal family life. Normally, the eye first moves towards the principal figures in an illustration and then notes the background details, but here Reinhart has focused our attention on the bureau with its lion's-paw legs, to which we are introduced simultaneously through the letter-press at the top of the page and in the plate. In contrast to the room at The Pegusus's Arms in the previous illustration, this room has been personalised with books and papers on a desk in the corner of the room (right), ands is lit by a fireplace (left). "A few books and writings were on an old bureau in a corner, the furniture was decent and sufficient" (Ch. 10). These personal objects, however, Reinhart has but sketchily shown (and omitted entirely the three-legged table beside which Mrs. Blackpool has fallen) because his emphasis is on the figures of the honest mechanic, candle held in his upstage (left) hand, and his quasi-human wife, steadying herself with her left hand as she pushes the tangled hair from her face with her right (upstage) hand, as in the letter-press. Though her face in plate 4 is "stolid and drowsy" (Ch. 10) as Dickens remarks, we have no sense of her swaying to and fro, nor of her gesticulating. The moral infamy with which Dickens invests her we intuit from her general blackness, her cat-like face hidden behind a veil of uncombed hair, and the claw-like left hand which echoes the claw-like foot of the bureau.

Reinhart's own background is worth noting in connection with his sympathetic treatment of Stephen Blackpool, for as a young man in his native Pittsburgh he was employed in railway work and at a steel factory, before he left America to study art in Paris and Munich. "

When I first saw the illustration I thought for a minute he was holding a gun and was about to shoot her, or already had.

Kim wrote: "Peter you got me to look up two things in one thread. First there is nine oils:

In the 19th century, the nine oils was a preparation, or liniment, which was rubbed into the skin to relieve aches, ..."

Kim

As always, I really appreciate your research. There are days when I would like to use some nine oils myself. Like every time I do gardening, play with my grandchildren for an extended amount of time or re-arrange furniture. Come to think about it my left knee would like some right now. ;-)

In the 19th century, the nine oils was a preparation, or liniment, which was rubbed into the skin to relieve aches, ..."

Kim

As always, I really appreciate your research. There are days when I would like to use some nine oils myself. Like every time I do gardening, play with my grandchildren for an extended amount of time or re-arrange furniture. Come to think about it my left knee would like some right now. ;-)

Kim wrote: "

"'Heaven's Mercy, Woman!' He Cried, Falling Farther Off From The Figure. 'Has Thou Come Back Agen?'"

Chapter 10

Harry French

Illustration for Dicken's "Hard Times for These Times in the Britis..."

In this illustration it seems Stephen’s room is comfortable. The fireplace is well appointed, there are neat, framed pictures over the hearth, and on the table by the window rests a stove pipe hat. French’s depiction of the room seems at odds with Dickens’s description in the novel.

"'Heaven's Mercy, Woman!' He Cried, Falling Farther Off From The Figure. 'Has Thou Come Back Agen?'"

Chapter 10

Harry French

Illustration for Dicken's "Hard Times for These Times in the Britis..."

In this illustration it seems Stephen’s room is comfortable. The fireplace is well appointed, there are neat, framed pictures over the hearth, and on the table by the window rests a stove pipe hat. French’s depiction of the room seems at odds with Dickens’s description in the novel.

Kim wrote: "

"Stephen Blackpool"

Chapter 10

F.O.C. Darley

For Dickens's Hard Times, Household Edition (1862)

Text Illustrated:

"Heaven's mercy, woman!" he cried, falling farther off from the figure. "Has..."

Yes, indeed. Darley’s depiction of the ominous shadow on the wall is striking and depicts Mrs Blackpool much more effectively than French.

"Stephen Blackpool"

Chapter 10

F.O.C. Darley

For Dickens's Hard Times, Household Edition (1862)

Text Illustrated:

"Heaven's mercy, woman!" he cried, falling farther off from the figure. "Has..."

Yes, indeed. Darley’s depiction of the ominous shadow on the wall is striking and depicts Mrs Blackpool much more effectively than French.

This week's two chapters were like a curate's egg to me in that I was highly impressed by the first one and more or less bored by the second. At the same time, I'd like to thank Peter for his very insightful remarks on both chapters - details like the use of the number "nine", words like "wonder" in Louisa and Sissy's conversation, and the black ladder gave me a lot of new insight.

It was very touching to see how Louisa, in listening to Sissy's tale of her father and his story, and of the love that was the bedrock of the Jupes's family relations, was entering terra incognita, and how she kept asking and, yes, "wondering" about the father's devotion for his wife and his daughter and Sissy's trust in her father. While I find Sissy rather too one-dimensional in her naivity, I think that Dickens really succeeded in depicting Louisa as a multi-dimensional character, who is just on her way to seeing the world with different eyes due to the new acquaintance she made.

Clearly, this would not be in her father's interest, but so much more in her own, and it adds to the intensity of this talk that they are actually not supposed to have it.

Unlike his sister, Tom seems to be beyond any chance of widening his perspective, and he is an example of the bad side of utilitarianism, which of course also has good sides. I wondered that the girls carried on their conversation, knowing that Sissy is not supposed to talk about her former life, as they cannot be sure that Tom might give Sissy away if he had to gain something from it.

I said that Sissy was naive, but then I remembered the example of how she implicitly criticized M'Choakumchild's idea of national prosperity by asking exactly the right question: Little does it matter if a country regards itself as rich as long as large parts of the population do not get any share in these bounties. I'm sure that Dickens was not a Socialist, and neither am I, but this question is still a very legitimate one.

It was very touching to see how Louisa, in listening to Sissy's tale of her father and his story, and of the love that was the bedrock of the Jupes's family relations, was entering terra incognita, and how she kept asking and, yes, "wondering" about the father's devotion for his wife and his daughter and Sissy's trust in her father. While I find Sissy rather too one-dimensional in her naivity, I think that Dickens really succeeded in depicting Louisa as a multi-dimensional character, who is just on her way to seeing the world with different eyes due to the new acquaintance she made.

Clearly, this would not be in her father's interest, but so much more in her own, and it adds to the intensity of this talk that they are actually not supposed to have it.

Unlike his sister, Tom seems to be beyond any chance of widening his perspective, and he is an example of the bad side of utilitarianism, which of course also has good sides. I wondered that the girls carried on their conversation, knowing that Sissy is not supposed to talk about her former life, as they cannot be sure that Tom might give Sissy away if he had to gain something from it.

I said that Sissy was naive, but then I remembered the example of how she implicitly criticized M'Choakumchild's idea of national prosperity by asking exactly the right question: Little does it matter if a country regards itself as rich as long as large parts of the population do not get any share in these bounties. I'm sure that Dickens was not a Socialist, and neither am I, but this question is still a very legitimate one.

The second chapter I did not enjoy half as much because of Stephen and Rachael, whom I see as typically Dickensian caricatures of goodness. Having read the novel twice before, I don't really see any integrity in Stephen but just an inclination to wallow in self-pity and victimization. This "all thorns but no roses" talk did not convince me because as long as a person is healthy and capable, they can still do something with their lives and take decisions and thereby maintain their dignity. It may be hard but I see no such dignity in Stephen, and he does not strike me as a very realistically drawn character, either, but just as the object of paternalistic welfare fantasies - the way that "woke" people fancy those in whose behalf they speak up.

Like Mary Lou, I read Stephen's putting a blanket over his wife - whom he should have evicted, to start with - not so much as a token of pity but as an attempt to hide her from his own eyes. Just fancy that man sitting there all night instead of putting his foot down. No sympathy from me, I'm sorry.

Like Mary Lou, I read Stephen's putting a blanket over his wife - whom he should have evicted, to start with - not so much as a token of pity but as an attempt to hide her from his own eyes. Just fancy that man sitting there all night instead of putting his foot down. No sympathy from me, I'm sorry.

Tristram wrote: "This week's two chapters were like a curate's egg to me in that I was highly impressed by the first one and more or less bored by the second. At the same time, I'd like to thank Peter for his very ..."

Hi Tristram

By the end of this chapter we have before us two versions of relationships between a father and daughter. In the case of Gradgrind and Louisa we have a relationship where the father is intent on organizing and orchestrating every detail of his daughter’s life. In Sissy’s case, it is much the opposite. Mr Jupe chooses to leave his daughter to the care of others, to the care of fate, to her own devices? Those questions we will have to wait for the answer(s) yet to come.

As we proceed through the novel we may confront other forms of parenting as well. With M’Choakumchild’s school looming in the background, Hard Times may be an excellent novel to study the question of what is more important in a child’s life …Nature or Nurture.

Hi Tristram

By the end of this chapter we have before us two versions of relationships between a father and daughter. In the case of Gradgrind and Louisa we have a relationship where the father is intent on organizing and orchestrating every detail of his daughter’s life. In Sissy’s case, it is much the opposite. Mr Jupe chooses to leave his daughter to the care of others, to the care of fate, to her own devices? Those questions we will have to wait for the answer(s) yet to come.

As we proceed through the novel we may confront other forms of parenting as well. With M’Choakumchild’s school looming in the background, Hard Times may be an excellent novel to study the question of what is more important in a child’s life …Nature or Nurture.

Hi Peter,

The difference between Louisa and her brother Tom may help us discuss the question of Nature vs Nurture, I think. Both siblings grew up in the same conditions, were taught the same things - even Louisa, as a girl, seems to have been given a solid scientific education, which was more than most girls in her station of life usually got, since Victorians saw female requirements in needlework, singing, playing an instrument and so on. So, although she is a girl and Tom is a boy, their upbringing did not differ a lot, and yet they reacted to it in different ways. Both are repelled by Facts, Facts, Facts, but whereas Louisa takes the opportunity of looking at another person's childhood - Sissy's - and learning what other values there are in life, Tom just dreams of blowing the whole tower of learning up and does not care for anyone but Tom. Ironically, he remains indebted to the (negative sides of) the philosophy of utilitarianism, a philosophy he has good cause to resent for marring his childhood.

What made Louisa and Tom react in different ways to the same surroundings? Is it something innate in their characters? Is Louisa gifted with a deeper kind of intelligence or curiosity whereas Tom simply has no imagination? And if so, where do the origins of this gift lie?

The difference between Louisa and her brother Tom may help us discuss the question of Nature vs Nurture, I think. Both siblings grew up in the same conditions, were taught the same things - even Louisa, as a girl, seems to have been given a solid scientific education, which was more than most girls in her station of life usually got, since Victorians saw female requirements in needlework, singing, playing an instrument and so on. So, although she is a girl and Tom is a boy, their upbringing did not differ a lot, and yet they reacted to it in different ways. Both are repelled by Facts, Facts, Facts, but whereas Louisa takes the opportunity of looking at another person's childhood - Sissy's - and learning what other values there are in life, Tom just dreams of blowing the whole tower of learning up and does not care for anyone but Tom. Ironically, he remains indebted to the (negative sides of) the philosophy of utilitarianism, a philosophy he has good cause to resent for marring his childhood.

What made Louisa and Tom react in different ways to the same surroundings? Is it something innate in their characters? Is Louisa gifted with a deeper kind of intelligence or curiosity whereas Tom simply has no imagination? And if so, where do the origins of this gift lie?

I have got another question with regard to Stephen Blackpool: Our narrator describes him as a man of integrity, and this made me wonder. As a rule, integrity requieres a reference figure - you can show integrity to your family, your company, your country, or your own principles - but not simply show integrity without that kind of reference.

My quite predictible question now is: What or whom is Stephen's integrity directed at?

My quite predictible question now is: What or whom is Stephen's integrity directed at?

Kim wrote: "When I first saw the illustration I thought for a minute he was holding a gun and was about to shoot her, or already had...."

Kim wrote: "When I first saw the illustration I thought for a minute he was holding a gun and was about to shoot her, or already had...."That was my first thought, too, Kim!

Tristram wrote: "I don't really see any integrity in Stephen but just an inclination to wallow in self-pity and victimization...."

Tristram wrote: "I don't really see any integrity in Stephen but just an inclination to wallow in self-pity and victimization...."Wow, this was harsh, Tristram! My memories of the novel aren't that good, so perhaps there's something coming that will change my mind, but so far I find Stephen sympathetic - trying to do the right thing, but at the end of his rope. As Kim mentioned, whatever befell Mrs. Blackpool, we can assume it came about after Stephen married her, and now he's stuck. Did alcohol get her? Opium?

This is one of those situations where historic context would be helpful. Would a Victorian husband turn his addicted wife out, or be expected to show responsibility for her? A wealthier man would undoubtedly do what Dickens (the cad!) tried to do with Catherine, and have her committed to an asylum.

(EDIT: I had a comment here that was a bit of a spoiler, meant for the next installment. Sorry if anyone saw it prematurely!)

Kim wrote:

Kim wrote: "2.mix (a drink) or stir (an ingredient) into a drink.

"muddle the kiwi slices with the sugar"..."

I got a separate container with my blender that muddles things. I don't have a clue what to use it for, and it's taking up space in my pantry. Guess I need to drink more.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I don't really see any integrity in Stephen but just an inclination to wallow in self-pity and victimization...."

Wow, this was harsh, Tristram! My memories of the novel aren't th..."

Hi Mary Lou

The obligations of a man toward his wife were generally minimal. The higher the rank or social standing of a male might, in part, oblige the man to display some degree of responsibility, but that would be as much because of social grace than a legal requirement. Divorce in the Victorian Era was rare and expensive - and, to a great degree, political.

As we descend the ladder of society and financial resources the woman was in a very precarious position. The law would not really protect or compensate an abused woman of the lower classes. Sadly, the poor were rather expendable. Also, a very poor woman would not have the financial means to hire a lawyer. What compensation could be expected from a husband who, in all probability, had nothing anyway? Sad, but true.

I included the epigraph to the commentary in Chapter 11 to suggest the great division between those like Bounderby and those like Stephen. If we think of how Mrs Dickens was treated by Charles we get some idea of the male-female chasm that existed in a marriage in the 19 C.

Wow, this was harsh, Tristram! My memories of the novel aren't th..."

Hi Mary Lou

The obligations of a man toward his wife were generally minimal. The higher the rank or social standing of a male might, in part, oblige the man to display some degree of responsibility, but that would be as much because of social grace than a legal requirement. Divorce in the Victorian Era was rare and expensive - and, to a great degree, political.

As we descend the ladder of society and financial resources the woman was in a very precarious position. The law would not really protect or compensate an abused woman of the lower classes. Sadly, the poor were rather expendable. Also, a very poor woman would not have the financial means to hire a lawyer. What compensation could be expected from a husband who, in all probability, had nothing anyway? Sad, but true.

I included the epigraph to the commentary in Chapter 11 to suggest the great division between those like Bounderby and those like Stephen. If we think of how Mrs Dickens was treated by Charles we get some idea of the male-female chasm that existed in a marriage in the 19 C.

What I found very interesting about marriage in Victorian times was that passage in Oliver Twist where Bumble the Beadle was held accountable for his wife's embezzlements and fraudulent financial transactions on the grounds that the law regarded the husband as the wife's master, which made Bumble voice his timeless comment on the law. By the same token, Stephen might be regarded as responsible for his wife's behaviour. But that's just a guess.

As a wealthy woman I would never have married in Victorian England because with the marriage I would have forfeited my claim to my personal property and become wholly dependent on my husband.

As a wealthy woman I would never have married in Victorian England because with the marriage I would have forfeited my claim to my personal property and become wholly dependent on my husband.

Mary Lou wrote: "but so far I find Stephen sympathetic"

I don't and I think that the narrator's voice spoiled Stephen for me: All the talk of his being a man of integrity - I am still asking myself what that means really - and of his life being all thorns and no roses put me off the guy. And what the narrator and his story of sufferings did not achieve, Stephen's gruesome dialect completed. In my eyes, Stephen is a rather boring cardboard character, and so is Rachael. I must say that Mrs. Gaskell was much more successful in creating real-life working class characters.

I don't and I think that the narrator's voice spoiled Stephen for me: All the talk of his being a man of integrity - I am still asking myself what that means really - and of his life being all thorns and no roses put me off the guy. And what the narrator and his story of sufferings did not achieve, Stephen's gruesome dialect completed. In my eyes, Stephen is a rather boring cardboard character, and so is Rachael. I must say that Mrs. Gaskell was much more successful in creating real-life working class characters.

Alissa wrote: "The narrator also says that there was a "mistake" in Stephen's life where, "somebody else had become possessed of his roses, and he had become possessed of the same somebody else’s thorns in addition to his own." Who's thorns does he have, and what is the "mistake" that needs to be rectified?"

Alissa wrote: "The narrator also says that there was a "mistake" in Stephen's life where, "somebody else had become possessed of his roses, and he had become possessed of the same somebody else’s thorns in addition to his own." Who's thorns does he have, and what is the "mistake" that needs to be rectified?"I love this image.

Tristram wrote: This "all thorns but no roses" talk did not convince me because as long as a person is healthy and capable, they can still do something with their lives and take decisions and thereby maintain their dignity.

Stephen seems generally respected. I'm not sure where the lack of dignity would be except for his despair.

As for despair vs. doing something with his life, in the past I've researched the numbers for what exactly factory workers made and what you could buy with it. The chances of getting ahead on those numbers seem to be pretty darned slim but there were a few people who did, and also people who educated themselves and learned all kinds of things. So I suppose in a best-case scenario, "doing something with their lives" was possible for a few people of extraordinary talent and determination. But being legally shackled to a drunken addict would not appear to be the best-case scenario. I don't hold Stephen's lack of success in life--if that's what we can call it, when he's gainfully employed and has earned the affections of a stalwart soul like Rachel--against him.

You're right, Julie, Stephen's chances of doing something are actually very slim. But maybe, he could lay aside a little money every week and then, after a couple of years, go somewhere else, change his name and start a completely new life. I am not so sure they would have found him out in those days where neither actual or genetic fingerprints were known.

Tristram wrote: "his life being all thorns and no roses put me off the guy. And what the narrator and his story of sufferings did not achieve, Stephen's gruesome dialect completed..."

Tristram wrote: "his life being all thorns and no roses put me off the guy. And what the narrator and his story of sufferings did not achieve, Stephen's gruesome dialect completed..."I can't argue your point about the dialect. It's awful.

The narrator never tells us what Stephen's "thorns" are, other than his unfortunate marriage. Perhaps that's enough. He may be a bit two dimensional, but I can't help but think that Dickens is setting him up to be compared to Bounderby. How many times must we hear about Bounderby's misfortunes, which, if the woman Stephen encountered was Bounderby's mother as I suspect, were obvious lies? Whereas, presumably, Stephen has truly suffered hard times, but he carries on, not burdening EVERYONE HE MEETS with his hard luck stories. Unfortunately, we're only privy to his scenes with Rachael and Bounderby, but I imagine him as a good neighbor and friend who doesn't need the spotlight, but will lend a hand when he can. The narrow scope of the narrator does make him seem very self-pitying, though.

I only have the emotional strength to dislike so many characters, so I'm saving it up for Bounderby and Tom. :-)

Tristram wrote: "You're right, Julie, Stephen's chances of doing something are actually very slim. But maybe, he could lay aside a little money every week and then, after a couple of years, go somewhere else, change his name and start a completely new life. I am not so sure they would have found him out in those days where neither actual or genetic fingerprints were known...."

Tristram wrote: "You're right, Julie, Stephen's chances of doing something are actually very slim. But maybe, he could lay aside a little money every week and then, after a couple of years, go somewhere else, change his name and start a completely new life. I am not so sure they would have found him out in those days where neither actual or genetic fingerprints were known...."I bet a lot of people just skipped town like that. Especially when divorce was not an option.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "his life being all thorns and no roses put me off the guy. And what the narrator and his story of sufferings did not achieve, Stephen's gruesome dialect completed..."

I can't argu..."

That is indeed a very strong point, Mary Lou: Up to now, I have found Stephen a burden of boredom, but that was exactly because of the narrator's way of treating him, of showing him in that one situation sitting between Rachael and his wife, and because of the narrator's exulting praise of Stephen when there was little I found to be praised. Now, watching Stephen go through his everyday life, giving a hand to his neighbours and cracking the odd joke with them, might complete the picture. Unfortunately, the narrator leaves all this to our imagination and so it never occurred to me.

I can't argu..."

That is indeed a very strong point, Mary Lou: Up to now, I have found Stephen a burden of boredom, but that was exactly because of the narrator's way of treating him, of showing him in that one situation sitting between Rachael and his wife, and because of the narrator's exulting praise of Stephen when there was little I found to be praised. Now, watching Stephen go through his everyday life, giving a hand to his neighbours and cracking the odd joke with them, might complete the picture. Unfortunately, the narrator leaves all this to our imagination and so it never occurred to me.

Tristram wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "his life being all thorns and no roses put me off the guy. And what the narrator and his story of sufferings did not achieve, Stephen's gruesome dialect completed...."

Tristram wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "his life being all thorns and no roses put me off the guy. And what the narrator and his story of sufferings did not achieve, Stephen's gruesome dialect completed...."Agreed. We're told people think highly of him, but we don't see it much unless you count Rachel.

Sissy’s Progress

“There is no more to tell, Miss Louisa. I keep the nine oils ready for him, and I know he will come back.” Sissy

Little Nell, Florence Dombey, Agnes Wakefield, Esther Summerson. While Dickens’s novels are heavily populated by dominant male characters, there is always at least one female character who fits prominently into the cast of characters. In Hard Times will it be Sissy Jupe? Perhaps other females will have a major impact in the novel as well. If that is so, this novel would be a curious anomaly. Just imagine, in Coketown, a place of masculine industry that is dominated by the likes of males named Bounderby, Gradgrind, and M’Choakumchild, we might find a novel dominated by female characters. What a twist of plot and expectation that would be.

Other things are rattling around in my mind. It is evident that Coketown’s foundation is the Utilitarian philosophy of the maximum good for the most people. This philosophy is achieved through conformity. Contrasting that is the presence of fairy tales, circuses, and Dickens’s focus on people who wonder about the world around them. This is a friction that will need a resolution. Sissy has a bottle of nine oils which her father asked her to fetch. When Sissy came back to the Pegasus Arms her father had disappeared, but Sissy insists that her father will come back.

The number nine. How far off-base am I in wondering about about the number nine? Could it be a very subtle reference to the nine Muses? The nine Muses were Greek Goddesses who ruled over the Arts and Sciences and offered inspiration. In Sissy’s case, the bottle of nine oils is meant to help restore a person’s aching body. With this elixir, does Sissy symbolically hold the remedy for what ails the general population of Coketown? Time will tell.

This chapter focusses around a conversation between Sissy and Louisa. Sissy reveals that she feels out of place and inadequate in the school system. We learn that Louisa does have a curiosity about the world and its emotions beyond the front door of Stone Lodge. At one point Sissy tells Louisa that “I shall never learn.” Sissy is referring to learning from books and understanding facts. Louisa asks Sissy if her father loved her mother. Sissy assures her that he did. We learn that Sissy’s father often doubted himself and was sensitive to the times he could not entertain others. Did you notice how the words “wonder” and “laugh” and “kind” appear in Sissy’s description of her father?

When Sissy cries, Louisa goes to Sissy, kisses her, and takes her hand, and sits down beside her. Clearly, Louisa understands compassion even though she has not received much (or any) from her own parents. At this point, Tom enters the room and tells his sister that Bounderby has arrived, and Louisa should go to receive him. As readers, we already know that Tom’s only interest is his own self-interest. Tom has admitted that through his sister he will be able to gain concessions and advancement with Bounderby. How harsh is it to suggest that Tom is, in a sense, trying to pimp his sister to Bounderby for his own self-interest and advancement? As Tom says to Louisa, “ ‘Do look sharp for old Bounderby, Loo’ … with an impatient whistle ‘He’ll be off, if you don’t look sharp.’ ‘’

As the chapter ends, we are told that Tom “was becoming that not unprecedented triumph of calculation, which is usually the work on number one.” Tom has learned to take care of himself. His calculations are efficient. He will take care of himself, even if the price is his own sister.