The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Hard Times

>

Book One Chapters 11-12

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Hard Times 1-12

The Old Woman

“The bell was ringing, and the Serpent was a Serpent of many coils, and the Elephant was getting ready. The strange old woman was delighted with the very bell.”

Stephen leaves Bounderby’s house. Surely he must be discouraged, perhaps even depressed. As he begins his walk back to work he “felt a touch upon his arm.” Could it be Rachael? Is it his imagination? No. The hand touching him belongs to “an old woman, tall and shapely still, though withered by Time.” She has mud upon her shoes and “was newly come from a journey.” This mysterious lady asks if Stephen has just come from Bounderby’s house. She then asks if Stephen had seen Bounderby. There are further questions from the elderly woman but perhaps the biggest question of all is who is this old lady? Since Dickens has designated both a chapter and a chapter title to her, she must fit into the novel in some major way, but how?

We know she is poor. We know she lives some distance from Coketown, we know she has walked a great distance to the train station and come by a Parliamentary train. Such trains were very uncomfortable and meant for the poor traveller. Learning that Stephen was returning to work, the unknown lady asks if Stephen is happy at work and seems delighted to hear the bells of the factory. The bell was, the lady tells Stephen, “the beautifullist bell she had ever heard.” She wants to shake Stephen’s hand, she wants to kiss his hand.

At work, Stephen looks out the window and sees this lady still waits in front of the factory. “She was gone by and by” recounts Dickens, who again calls the factory the “Fairy Palace.” To signal the end of Stephen’s shift a bell rings and the Fairy Palace’s tall chimneys are transformed into “competing Towers of Babel.”

I find it very interesting how Dickens incorporates contrast in the novel. Sometimes the factories are fairy palaces all aglow in light. Then, their smokestacks are compared to Towers of Babel. How are we as readers meant to reconcile these two conflicting descriptions? Added to this is the repeated mention of the bells of churches and the factories. A major function of a bell is to call people to an assembly. It could be a church service, or to a work place, or even to a classroom. Does Dickens suggest that there is a similarity between churches and factories? Is Dickens being ironic, incorporating black humour, perhaps even foreshadowing what might be yet to come in the novel? What do you think?

The remainder of the chapter follows Stephen’s thoughts and reflections on his life. Clearly, he regrets his marriage. Obviously, he and Rachael have a deep and long-standing affection and love for each other. As the chapter ends Stephen makes his weary way home and back into the chains of his dissipated wife. There are many questions to this point in the novel, but the three most pressing (at least to me) are will Stephen and Rachael ever be together, who is the mysterious old woman that Stephen encountered in the street outside Bounderby’s house, and what the backstory of Rachael is?

We must wait for the answer to the first two of these questions. As for Rachael, well, we will meet her in more detail in the next chapter.

The Old Woman

“The bell was ringing, and the Serpent was a Serpent of many coils, and the Elephant was getting ready. The strange old woman was delighted with the very bell.”

Stephen leaves Bounderby’s house. Surely he must be discouraged, perhaps even depressed. As he begins his walk back to work he “felt a touch upon his arm.” Could it be Rachael? Is it his imagination? No. The hand touching him belongs to “an old woman, tall and shapely still, though withered by Time.” She has mud upon her shoes and “was newly come from a journey.” This mysterious lady asks if Stephen has just come from Bounderby’s house. She then asks if Stephen had seen Bounderby. There are further questions from the elderly woman but perhaps the biggest question of all is who is this old lady? Since Dickens has designated both a chapter and a chapter title to her, she must fit into the novel in some major way, but how?

We know she is poor. We know she lives some distance from Coketown, we know she has walked a great distance to the train station and come by a Parliamentary train. Such trains were very uncomfortable and meant for the poor traveller. Learning that Stephen was returning to work, the unknown lady asks if Stephen is happy at work and seems delighted to hear the bells of the factory. The bell was, the lady tells Stephen, “the beautifullist bell she had ever heard.” She wants to shake Stephen’s hand, she wants to kiss his hand.

At work, Stephen looks out the window and sees this lady still waits in front of the factory. “She was gone by and by” recounts Dickens, who again calls the factory the “Fairy Palace.” To signal the end of Stephen’s shift a bell rings and the Fairy Palace’s tall chimneys are transformed into “competing Towers of Babel.”

I find it very interesting how Dickens incorporates contrast in the novel. Sometimes the factories are fairy palaces all aglow in light. Then, their smokestacks are compared to Towers of Babel. How are we as readers meant to reconcile these two conflicting descriptions? Added to this is the repeated mention of the bells of churches and the factories. A major function of a bell is to call people to an assembly. It could be a church service, or to a work place, or even to a classroom. Does Dickens suggest that there is a similarity between churches and factories? Is Dickens being ironic, incorporating black humour, perhaps even foreshadowing what might be yet to come in the novel? What do you think?

The remainder of the chapter follows Stephen’s thoughts and reflections on his life. Clearly, he regrets his marriage. Obviously, he and Rachael have a deep and long-standing affection and love for each other. As the chapter ends Stephen makes his weary way home and back into the chains of his dissipated wife. There are many questions to this point in the novel, but the three most pressing (at least to me) are will Stephen and Rachael ever be together, who is the mysterious old woman that Stephen encountered in the street outside Bounderby’s house, and what the backstory of Rachael is?

We must wait for the answer to the first two of these questions. As for Rachael, well, we will meet her in more detail in the next chapter.

Since I never believed Bounderby's stories about his background in the first place, I am certain we just met his mother. It would be typically Bounderby to just abandon his own mother because it was more convenient, and then pretend it was the other way around because that was more convenient too, wouldn't it? Also, it would fit the way Dickens' stories work. We then would have extra contrast for emphasis: Bounderby who just like that abandons the women in his life and thinks nothing of it, while Stephen has tried so hard and so long to stay with his wife and make something of them being together, even if she drinks away all his money and belongings over and over again, and even when he then wants a legal divorce because he can't keep up with it any longer Bounderby tells him off that it's immoral. Just because he's not rich, and not Bounderby.

Jantine wrote: "Since I never believed Bounderby's stories about his background in the first place, I am certain we just met his mother. It would be typically Bounderby to just abandon his own mother because it wa..."

Hi Jantine

You are thinking like Dickens. I especially like how you give us evidence of how despicable and two-faced Bounderby is. By demonstrating how Bounderby treats women, Stephen’s situation is indeed intensified.

The plot of HT is becoming more interesting and intriguing. How Dickens managed to do so week after week always amazes me.

Hi Jantine

You are thinking like Dickens. I especially like how you give us evidence of how despicable and two-faced Bounderby is. By demonstrating how Bounderby treats women, Stephen’s situation is indeed intensified.

The plot of HT is becoming more interesting and intriguing. How Dickens managed to do so week after week always amazes me.

Jantine, I think you may be right - because that is exactly how Dickens's stories normally turn out and it would also expose the whole tale of Bounderby as a selfmade man as a fantasy.

Peter wrote: "As this chapter opens Dickens shows how an illusion becomes a reality by telling the reader that “The Fairy palaces burst into illumination, before pale morning showed the monstrous serpents of smoke trailing themselves over Coketown.” Appearance and reality. This trope will follow us throughout the novel. What appears on the surface of life, people, and places can quickly disappear to reveal something that lies just below the surface that is much different.”

What an interesting idea, Peter! If appearances are deceiving and if factories that look from afar like fairies' palaces reveal themselves as places of drudgery and toil and mindlessness, I could, playing the devil's advocate, argue strongly for Gradgrind's philosophy of Facts, Facts, Facts - saying that you should not cling to nice outward appearances but ought to go to the bottom of things instead of relying on your imagination.

There seems to be an interesting contradiction in Dickens's novel here - because for the travelling actors who only look at the outside of the factories and make up their stories, these factories might look romantic.

What an interesting idea, Peter! If appearances are deceiving and if factories that look from afar like fairies' palaces reveal themselves as places of drudgery and toil and mindlessness, I could, playing the devil's advocate, argue strongly for Gradgrind's philosophy of Facts, Facts, Facts - saying that you should not cling to nice outward appearances but ought to go to the bottom of things instead of relying on your imagination.

There seems to be an interesting contradiction in Dickens's novel here - because for the travelling actors who only look at the outside of the factories and make up their stories, these factories might look romantic.

Peter wrote: "Curiously, Mrs Sparsit asks Stephen if there was a significant different in their ages. Well, is it a curious question? We know that Mrs Sparsit and Bounderby have a rather interesting relationship and we know that Bounderby has a keen interest in the much younger Louisa Gradgrind. What might Mrs Sparsit be up to?"

Another interesting point! When I read this passage, I thought that Mrs. Sparsit's mind was reverting to her own unhappy marriage with a man who was many years her junior and that this is a sign of her self-centredness. Now, I see what you mean: Has Mrs. Sparsit set her cap on Mr. Bounderby after all and resents the young chit Louisa as a potential rival? It may well be so.

As to Stephen's language, Peter: I do find it very hard to understand what he is talking about and often find myself skimming over his talk. All the more so since I don't like him particularly.

Another interesting point! When I read this passage, I thought that Mrs. Sparsit's mind was reverting to her own unhappy marriage with a man who was many years her junior and that this is a sign of her self-centredness. Now, I see what you mean: Has Mrs. Sparsit set her cap on Mr. Bounderby after all and resents the young chit Louisa as a potential rival? It may well be so.

As to Stephen's language, Peter: I do find it very hard to understand what he is talking about and often find myself skimming over his talk. All the more so since I don't like him particularly.

I posted this in last week's discussion by mistake. Here it is in its correct place:

I posted this in last week's discussion by mistake. Here it is in its correct place:My question is, why on Earth would Stephen go to Bounderby for advice, rather than, say, a vicar or even a more direct supervisor (though I think even that would be inappropriate)? Imagine somebody in Amazon packaging knocking of Bezos's office door and asking for marital advice.

Bounderby had no idea who Stephen was, but now Stephen is on his radar as some sort of rabble-rouser, though that's obviously unfair. The decision to consult Bounderby may well come back to haunt Stephen and be another negative turning point in his life, I'm afraid.

Peter wrote: "their smokestacks are compared to Towers of Babel..."

Peter wrote: "their smokestacks are compared to Towers of Babel..."The Tower of Babel story has to do with the people getting too big for their britches and building a tall tower to show their hubris. God decided to use the divide and conquer strategy, separating them into weaker groups by giving them different languages so they can't effectively communicate.

Will this reference be significant?

Peter wrote: "Are you encountering any difficulty with Stephen’s speech pattern?

Yes.

Mary Lou wrote: "I posted this in last week's discussion by mistake. Here it is in its correct place:

My question is, why on Earth would Stephen go to Bounderby for advice, rather than, say, a vicar or even a more..."

It makes no sense. At least if I ever wanted advice on my marriage, going to the owner of the company I worked for wouldn't even enter my mind. Until now that is.

My question is, why on Earth would Stephen go to Bounderby for advice, rather than, say, a vicar or even a more..."

It makes no sense. At least if I ever wanted advice on my marriage, going to the owner of the company I worked for wouldn't even enter my mind. Until now that is.

Tristram wrote: "I do find it very hard to understand what he is talking about and often find myself skimming over his talk. All the more so since I don't like him particularly.."

I don't like him much either and I can't figure out why. All I know is that every time he is in a "muddle" I roll my eyes. And I'm certainly glad I'm not the perfect Rachael either.

I don't like him much either and I can't figure out why. All I know is that every time he is in a "muddle" I roll my eyes. And I'm certainly glad I'm not the perfect Rachael either.

Jantine wrote: "Since I never believed Bounderby's stories about his background in the first place, I am certain we just met his mother. It would be typically Bounderby to just abandon his own mother because it wa..."

I was just sitting here thinking it's good Bounderby wasn't born in a palace or even in a nice home with parents who loved him. If he hadn't been born in a gutter in an egg box I'd think he would have committed suicide by now. And to think, it may all be a lie. :-)

I was just sitting here thinking it's good Bounderby wasn't born in a palace or even in a nice home with parents who loved him. If he hadn't been born in a gutter in an egg box I'd think he would have committed suicide by now. And to think, it may all be a lie. :-)

Mary Lou wrote: "I posted this in last week's discussion by mistake. Here it is in its correct place:

My question is, why on Earth would Stephen go to Bounderby for advice, rather than, say, a vicar or even a more..."

Maybe, Stephen went to get Bounderby's advice - something that the Amazon package guy would not do - because in the earlier days of industrialization, the mill owners stylized themselves as patriarchs, as some sort of father to all their workers. The relationship was probably still more direct in those days than in ours, which are characterized by large anonymous concerns. I think that Bounderby could still know most of his workers from sight and even by name, and they certainly knew him.

My question is, why on Earth would Stephen go to Bounderby for advice, rather than, say, a vicar or even a more..."

Maybe, Stephen went to get Bounderby's advice - something that the Amazon package guy would not do - because in the earlier days of industrialization, the mill owners stylized themselves as patriarchs, as some sort of father to all their workers. The relationship was probably still more direct in those days than in ours, which are characterized by large anonymous concerns. I think that Bounderby could still know most of his workers from sight and even by name, and they certainly knew him.

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I do find it very hard to understand what he is talking about and often find myself skimming over his talk. All the more so since I don't like him particularly.."

I don't like him..."

What a remarkable coincidence, Kim! We dislike the same characters in this book!

I don't like him..."

What a remarkable coincidence, Kim! We dislike the same characters in this book!

I got to thinking after Catherine was mentioned, and looked it up. Dickens himself divorced Catherine in 1958, only four years after Hard Times was first published. Around the time he wrote this, they already had quite some marital problems. Perhaps Dickens projected something of (how he perceived) himself and his own marriage in Blackpool. We all know he treated Catherine horribly, but he must have seen himself as a man of integrity too, and as we probably all know it's very easy to see the other party in marital problems as the 'ogress'.

That would be rather off-putting, Dickens building himself up in the Stephen Blackpool character, but there might be something to it, Jantine. Up to now, we have not been given any information why Stephen's wife turned to alcohol - the only thing we know, accidentally from Stephen, was that he was always a good husband to her. Maybe, even Dickens felt the same with regard to his wife - or at least wanted to persuade himself he did.

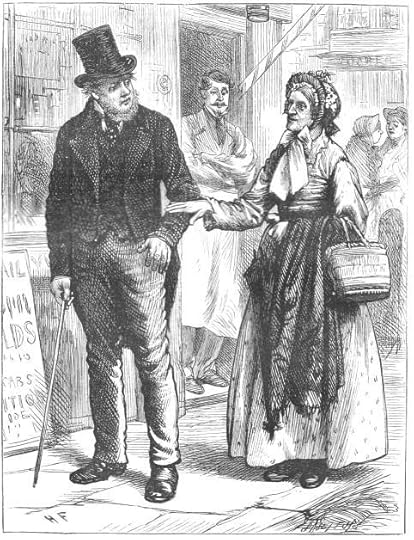

"He Felt A Touch Upon His Arm"

Chapter 12

Harry French

Text Illustrated:

"Old Stephen descended the two white steps, shutting the black door with the brazen door-plate, by the aid of the brazen full-stop, to which he gave a parting polish with the sleeve of his coat, observing that his hot hand clouded it. He crossed the street with his eyes bent upon the ground, and thus was walking sorrowfully away, when he felt a touch upon his arm.

It was not the touch he needed most at such a moment—the touch that could calm the wild waters of his soul, as the uplifted hand of the sublimest love and patience could abate the raging of the sea—yet it was a woman’s hand too. It was an old woman, tall and shapely still, though withered by time, on whom his eyes fell when he stopped and turned. She was very cleanly and plainly dressed, had country mud upon her shoes, and was newly come from a journey. The flutter of her manner, in the unwonted noise of the streets; the spare shawl, carried unfolded on her arm; the heavy umbrella, and little basket; the loose long-fingered gloves, to which her hands were unused; all bespoke an old woman from the country, in her plain holiday clothes, come into Coketown on an expedition of rare occurrence. Remarking this at a glance, with the quick observation of his class, Stephen Blackpool bent his attentive face—his face, which, like the faces of many of his order, by dint of long working with eyes and hands in the midst of a prodigious noise, had acquired the concentrated look with which we are familiar in the countenances of the deaf—the better to hear what she asked him."

Well I never thought I'd come across an illustration of Bounderby that looks like this, but I did. I don't know who the artist is:

Commentary:

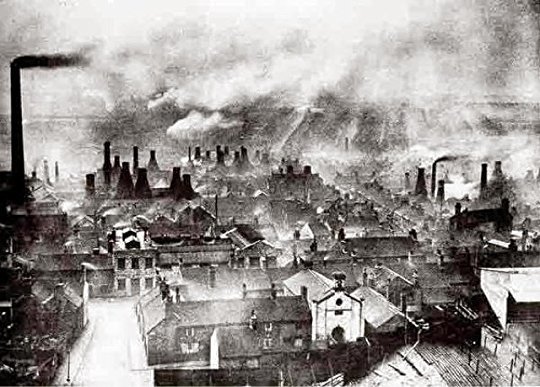

In Hard Times, Dickens is forthright in opposing the fact-based state of education and dehumanizing industrialization of city life in Victorian England. He is convinced that the societal systems he sees in place are reductive to the complexity of human emotion and thought, and uses mechanistic imagery throughout the novel to imply that the harsh factory labor, urban industrialization, and policing of free thought in the educational system that pervades Coketown is responsible for the mechanical actions and thought processes of the characters. In his description of Coketown, his exposition on the passage of time, and his illustration of characters, Dickens delivers a negative perspective on industrialization that culminates to a dismal portrait of Victorian England and a call to readers to alter the bleak and destructive path humanity has taken to achieve modern progress.

In his rendering of Coketown, Dickens creates “a town of machinery” that is an “unnatural red and black like the painted face of a savage”. Smoke is never “uncoiled” in the air above, and there is “rattling and trembling” where a steam-engine piston “works monotonously up and down”. Dickens’ view of Coketown is clearly defined in his description of it as a “wilderness of smoke and brick” with “direful uniformity”, as it is “shrouded in a haze of its own”. Dickens is harsh in his portrayal of a hellish scene– the coiling, the rattling, the up and down of the piston that creates the “wilderness” and the shroud. The town is inorganic, inhumane and rusted. It is a “savage” like an uncivilized animal. While its “wilderness” implies a sense of life, the town is covered, hidden from enlightenment, a hazy corpse wrapped in smog. And it is through his dire, smogged filled imagery that we are able to picture such a noxious environment.

Kim wrote: "

"He Felt A Touch Upon His Arm"

Chapter 12

Harry French

Text Illustrated:

"Old Stephen descended the two white steps, shutting the black door with the brazen door-plate, by the aid of the braz..."

Kim

You present us with a puzzle, or at least me. First, it is good to be reminded of the multiple times that Rachael has touched Stephen on the arm. Now, the touch is from a crone-like woman. So often, Dickens presents us with opposites, contrasts, and contradictions in order to heighten and intensify his plot. Rachael and the old woman … how do they fit? Do they fit?

For the life of me I can’t understand French’s depiction of Stephen. Top hat, walking cane, a cravat/tie. Stephen must be the best dressed factory hand in Coketown.

"He Felt A Touch Upon His Arm"

Chapter 12

Harry French

Text Illustrated:

"Old Stephen descended the two white steps, shutting the black door with the brazen door-plate, by the aid of the braz..."

Kim

You present us with a puzzle, or at least me. First, it is good to be reminded of the multiple times that Rachael has touched Stephen on the arm. Now, the touch is from a crone-like woman. So often, Dickens presents us with opposites, contrasts, and contradictions in order to heighten and intensify his plot. Rachael and the old woman … how do they fit? Do they fit?

For the life of me I can’t understand French’s depiction of Stephen. Top hat, walking cane, a cravat/tie. Stephen must be the best dressed factory hand in Coketown.

Kim wrote: "Here is Mr. Bounderby by Ron Embleton. I wish we could see it better:

"

I already like what I see, Kim!

"

I already like what I see, Kim!

Tristram wrote: "Maybe, Stephen went to get Bounderby's advice - something that the Amazon package guy would not do - because in the earlier days of industrialization, the mill owners stylized themselves as patriarchs, as some sort of father to all their workers.."

Tristram wrote: "Maybe, Stephen went to get Bounderby's advice - something that the Amazon package guy would not do - because in the earlier days of industrialization, the mill owners stylized themselves as patriarchs, as some sort of father to all their workers.."Yes, I think that's right--and even more than patriarchs, feudal overlords with a responsibility to their serfs. Hard Times is dedicated to Thomas Carlyle, the author of Past and Present, a book that compares the industrial present to the feudal past as exemplified by a benevolently-ruled monastery (Bury St. Edmund's Abbey). Guess which emerges as better in the comparison?

There was a real current in mid-19th c thought, a lot of it touched off by Sir Walter Scott novels, theorizing that the poor were better off under medieval rule than capitalist industrial rule. At its best, this line of thought advocated for better working conditions for the poor. At its worst, it theorized that a slave economy was better than a capitalist economy.

Hi Tristram and Julie

Harold Perkin in “The Origins of Modern English Society” outlines how the English moved from a vertical to a horizontal society. Like you both point out the vertical society had the landowner, or titled person, on top. He would have all the power, but for the system to work efficiently, the aristocrat would also have to take care of and be responsible for those who worked the land. Thus each rural town would have a church, a pub, and other “amenities.” When an individual connected to the land owner fell ill, or was injured or otherwise incapacitated, the aristocrat would be the person on whom the responsibility of care would fall. This, in turn, would create a bond and trust between worker and landowner.

When industrialization came about, the axis tilted. Now, masses of people, often unconnected by former location or history, flooded into towns and cities. Most worked without any direct connection or history for a manufacturer. He in turn, wanted profit without any social responsibility. In time, skilled workers or entrepreneurs became more valuable. They rose out of their positions and were able to create their own value. In the 19C the entrepreneurial spirit flourished.

With Stephen, I would suggest Dickens was portraying him as “old school.” He felt an obligation to his employer. When Bounderby can offer no help except to say the world runs on money, it may be that Dickens is harkening back to the past when a man’s worth was both the work he was capable of and the connection he had to a specific world of rural obligations. By the mid 1850’s the only true master was money, not morality or sense of obligation to anyone else.

Harold Perkin in “The Origins of Modern English Society” outlines how the English moved from a vertical to a horizontal society. Like you both point out the vertical society had the landowner, or titled person, on top. He would have all the power, but for the system to work efficiently, the aristocrat would also have to take care of and be responsible for those who worked the land. Thus each rural town would have a church, a pub, and other “amenities.” When an individual connected to the land owner fell ill, or was injured or otherwise incapacitated, the aristocrat would be the person on whom the responsibility of care would fall. This, in turn, would create a bond and trust between worker and landowner.

When industrialization came about, the axis tilted. Now, masses of people, often unconnected by former location or history, flooded into towns and cities. Most worked without any direct connection or history for a manufacturer. He in turn, wanted profit without any social responsibility. In time, skilled workers or entrepreneurs became more valuable. They rose out of their positions and were able to create their own value. In the 19C the entrepreneurial spirit flourished.

With Stephen, I would suggest Dickens was portraying him as “old school.” He felt an obligation to his employer. When Bounderby can offer no help except to say the world runs on money, it may be that Dickens is harkening back to the past when a man’s worth was both the work he was capable of and the connection he had to a specific world of rural obligations. By the mid 1850’s the only true master was money, not morality or sense of obligation to anyone else.

Peter wrote: “By the mid 1850’s the only true master was money, not morality or sense of obligation to anyone else.."

Peter wrote: “By the mid 1850’s the only true master was money, not morality or sense of obligation to anyone else.."Yes, Carlyle's quote was that under industrialism, "Cash payment is the sole nexus between man and man."

I haven't read Perkins's Origins--thanks for pointing it out.

Now I'm going to go chuckle over Tristram's comment about the Amazon guy not going to Bezos. Maybe Bezos was attempting an old-school moment when he thanked all the Amazon workers for sending him to space.

If company workers really had the power to send their bosses to space, would they include a return ticket?

As a conservative, Carlyle would, no doubt, see the seigneurial relationship between lord and serf as far superior to the one between factory owner and labourer. His major reason seems to have been the assumption that in the Middle Ages, relationships between the high and the low were not only defined through materialistic aims (getting the most out of the workers and paying them only so much as to keep them barely satisfied) but also through personal responsibility. Some of you may have noticed that I, too, have strong conservative leanings, and I also see the big problem of our times in the reification of people as objects of administration by the government. People turn into consumer-atoms and they look to the state in cases of emergency and hardship whereas in former times they tended to help each other. These consumer-atoms are easy to govern, though. I've read my fair share of Hannah Arendt, Kenneth Minogue and Roger Scruton, as you may guess.

What I want to say by all this is that I'd define conservatism as thinking that is based on the dignity and value of the individual but also on their responsibility for themselves. I think that Carlyle's conservatism was different in that he propagated the responsibility of the lord for the serf - and that the serf's lack of freedom was the price he had to pay for it and would pay willingly. In these points, I think that Carlyle idealized the past because in reality, seigneurs had but little regard for their serfs and the serfs' duties were often far-reaching. Generally, even I as a conservative am aware of the Chinese saying according to which the past paints with a golden brush.

What I want to say by all this is that I'd define conservatism as thinking that is based on the dignity and value of the individual but also on their responsibility for themselves. I think that Carlyle's conservatism was different in that he propagated the responsibility of the lord for the serf - and that the serf's lack of freedom was the price he had to pay for it and would pay willingly. In these points, I think that Carlyle idealized the past because in reality, seigneurs had but little regard for their serfs and the serfs' duties were often far-reaching. Generally, even I as a conservative am aware of the Chinese saying according to which the past paints with a golden brush.

Tristram wrote: "If company workers really had the power to send their bosses to space, would they include a return ticket?"

Tristram wrote: "If company workers really had the power to send their bosses to space, would they include a return ticket?"My immediate supervisor is also one of my closest friends. She often talks about the idyllic life she plans to have on her planet someday, and as a like-minded thinker, I've been invited to come live on her planet when the time comes. But it would be so much better if we could just send everyone else to another planet, and keep this one to ourselves. :-)

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "If company workers really had the power to send their bosses to space, would they include a return ticket?"

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "If company workers really had the power to send their bosses to space, would they include a return ticket?"My immediate supervisor is also one of my closest friends. She often ta..."

I agree--I am kind of attached to this planet. I guess my getaway fantasies are less about leaving it than going off the grid, which I would probably not like as much as I imagine, especially if it meant no libraries and limited hot water.

No Way Out

Bounderby: “But it’s not for you at all. It costs money. It costs a mint of money.”

Stephen: “There’s no other law?”

Bounderby: “Certainly not.”

As this chapter opens Dickens shows how an illusion becomes a reality by telling the reader that “The Fairy palaces burst into illumination, before pale morning showed the monstrous serpents of smoke trailing themselves over Coketown.” Appearance and reality. This trope will follow us throughout the novel. What appears on the surface of life, people, and places can quickly disappear to reveal something that lies just below the surface that is much different.

Early in the chapter Dickens focusses on the reality of Coketown. Twice he repeats the phrase “the work went on.” Work is the relentless reality of the hundreds of men and women who work in Coketown’s mills and factories. The word “coke” is important to look at in context. Coke is the word used to describe what is left after the imperfect combustion of coal in a fire. Like the coke of the factory fires, the workers in those factories are reduced, diminished, and broken down. The character of Stephen Blackpool is one of those men.

In this chapter we see Stephen going cap-in-hand to see Bounderby. Stephen wants to know if it is possible for him to divorce his wife. We learn that he and his wife were married 19 years ago, that his wife took to drinking and caused general panic and that Stephen tried to be a good husband but had no success. Curiously, Mrs Sparsit asks Stephen if there was a significant different in their ages. Well, is it a curious question? We know that Mrs Sparsit and Bounderby have a rather interesting relationship and we know that Bounderby has a keen interest in the much younger Louisa Gradgrind. What might Mrs Sparsit be up to?

Stephen tells Bounderby that “I mun’ be ridden o’ her.” Stephen says he has heard how the rich can make arrangements for separation or divorce, or separate themselves within a grand house into separate rooms. People like Stephen, however, who live in only one room are trapped. Stephen goes through a list of ways in which he is trapped within his marriage. Bounderby agrees that Stephen is trapped, but has no sympathy for him.

Stephen reflects on what he has learned and sums up both his life and the world around him as being a muddle. As the chapter ends Stephen leaves Bounderby and heads back into his dreary life with a drunken wife and no hope for any redemption or happiness. Much as how the description of the Fairy palaces of Coketown change in the light to reveal the horrors and ugliness of the town, we now witness how any hope that Stephen could find happiness have been shredded by the reality of his position as an impoverished worker in Coketown.

As I look back upon the first chapters of this novel I am struck with how, on the one hand, we see how a loving family functions and, on the other hand, how business, commerce, and the power of the almighty dollar weaken, if not pervert, the family. I see Sleary’s circus as being a family, a big, boiling, rambunctious gathering of individuals who may not be bonded by blood, but are bonded to one another in purpose, co-operation, and dependence upon each other for success and community. The world of Bounderby, on the other hand, measures power and success in terms of cold facts, cold emotions, and a disregard for the emotions of others.

Dickens gives the reader a look at Stephen Blackpool, a man of integrity and skill who lives in a real world of pain and sorrow. Bounderby lives in a self-made world of bluster. These two individual live in separate psychological worlds but the same physical place. Stephen’s world is one of callous reality; Bounderby’s world is one of egocentric power and disregard for others.

Thoughts

Are you encountering any difficulty with Stephen’s speech pattern?

How would you define a family? Which family do you see as more functional? Would it be the Gradgrind’s or Sleary’s circus?