The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit, Book 1, Chp. 15-18

Chapter 16, which deals with “Nobody’s Weakness“, leads us back to Arthur, who one fine Saturday morning in spring, decides that it would be a good occasion to renew his acquaintance with the Meagles family and to take a walk over to Twickenham, where Mr. Meagles has a cottage. As the narrator tells us,

”[i]t’s not easy to walk alone in the country without musing upon something”,

and so it’s little wonder that Arthur soon starts pondering on a variety of important issues, such as what he is going to do with the remainder of his life. This question seems urgent to him because he knows that he cannot live on his savings and inheritance without stretching them to their limits, but neither can he invest his money as he likes for he somehow feels that somebody might have some sort of claim on them. He also thinks about his relationship with his mother, which has become peaceful though not confidential. Another question that crops up in his mind is how to further the interests of Little Dorrit, how to help her fend for her thankless family, and he finally comes to think of her as ”his adopted daughter, his poor child of the Marshalsea hushed to rest.” Oh dear, oh dear – the question might rather be whether there is room on Little Dorrit’s pedestal for yet another father.

On his way to Twickenham, Arthur runs into Daniel Doyce, and the two continue their way together. We learn this of the engineer:

”It was at first difficult to lead him to speak about himself, and he put off Arthur's advances in that direction by admitting slightly, oh yes, he had done this, and he had done that, and such a thing was of his making, and such another thing was his discovery, but it was his trade, you see, his trade; until, as he gradually became assured that his companion had a real interest in his account of himself, he frankly yielded to it.“

When I read this, I thought that in some way there is a similarity between Daniel Doyce and Mr. Pancks in that they both love and live for their profession, and they both think that being alive and excelling at their profession is one and the same thing. Maybe Arthur could learn one or two things from these two people since his pensive and scrupulous attitude and his disenchantment with life are on the brink of leading him into idleness, or at least, into inaction and indecision. Luckily, it turns out that Daniel Doyce is thinking of having another business partner, whose task it would be to look after the Shop in terms of business. I have a feeling that Arthur is going to be this partner of Doyce’s, and that Doyce’s enterprising manner will help overcome certain doubts of Clennam’s as to whether man should toil or not just contemplate the unfair dealings of life’s Circumlocution Offices:

”’Hadn't he better let it go?’ said Clennam.

‘He can't do it,’ said Doyce, shaking his head with a thoughtful smile. ‘It's not put into his head to be buried. It's put into his head to be made useful. You hold your life on the condition that to the last you shall struggle hard for it. Every man holds a discovery on the same terms.’

‘That is to say,’ said Arthur, with a growing admiration of his quiet companion, ‘you are not finally discouraged even now?’

‘I have no right to be, if I am,’ returned the other. ‘The thing is as true as it ever was.’”

When they finally arrive at Mr. Clennam’s place, Arthur finds it very expressive of the Meagles household in terms of coziness and comfort. The narrator remarks:

”There was even the later addition of a conservatory sheltering itself against it, uncertain of hue in its deep-stained glass, and in its more transparent portions flashing to the sun's rays, now like fire and now like harmless water drops; which might have stood for Tattycoram.”

Speaking of Tattycoram, is it not interesting that Tattycoram is not sitting at the table with the Meagles and their guests when they are having their dinner, but that she has to run some errands in the house? She also calls Pet, whose name in fact is Minnie (not much better than Pet, if you ask me), “Miss”, which makes her rather a servant than an adopted sister. We also see more signs of Tattycoram’s so-called bad temper, which is often aroused when the Meagleses make a lot of their daughter, and which shows itself in ”an angry and contemptuous frown upon her face, that changed its beauty into ugliness.” The narrator, however, seems to take sides with Pet and the Meagleses, as is shown in this scene:

”’Oh, Tatty!’ murmured her mistress, ‘take your hands away. I feel as if some one else was touching me!’

She said it in a quick involuntary way, but half playfully, and not more petulantly or disagreeably than a favourite child might have done, who laughed next moment. Tattycoram set her full red lips together, and crossed her arms upon her bosom.”

This scene occurs when the company are sitting together, discussing their time in Marseilles and wondering what might have become of their fellow travellers. When the talk centres on Miss Wade, Tatty, who happens to be in the room, tells them all that Miss Wade has written to her offering her support and help whenever she feels herself hurt. She also lets out that she has once met Miss Wade near the church. Pet says that the thought of Miss Wade gives her a feeling of horror, and Mr. Meagles shows that he understands Tattycoram’s fits of anger and discontent, given that she has never experienced parental love. If he does, though, he has a wonderfully awkward way of treating Tattycoram, always advising her to count twenty-five when she finds herself in a bad mood. The Meagleses may not know it, but if you ask me, they have taken up Tattycoram not so much for her own sake but more to pander to the spoilt comforts of their insipid daughter. I have a feeling that we have not seen the last of Miss Wade.

We also learn that Mr. Meagles, when he was still active, was a successful and clear-sighted businessman, working for a bank – thus he may pass as a foil to Mrs. Clennam: While the latter has neglected more humane qualities in business life, the former has successfully managed to combine both efficiency and humaneness. Be that as it may, it is Mr. Meagles, who finally advises Clennam and Doyce to enter into a partnership.

We also learn that Arthur, in the course of his stay at the Meagleses’ house, considers the question whether it is advisable or not to allow himself to fall in love with Pet. He is not sure whether he may not be too old for Pet but on the other hand he thinks that Mr. Meagles has a high regard for him and that the Meagleses would therefore not feel too sorry at the thought of having to release their daughter into marriage.

”[i]t’s not easy to walk alone in the country without musing upon something”,

and so it’s little wonder that Arthur soon starts pondering on a variety of important issues, such as what he is going to do with the remainder of his life. This question seems urgent to him because he knows that he cannot live on his savings and inheritance without stretching them to their limits, but neither can he invest his money as he likes for he somehow feels that somebody might have some sort of claim on them. He also thinks about his relationship with his mother, which has become peaceful though not confidential. Another question that crops up in his mind is how to further the interests of Little Dorrit, how to help her fend for her thankless family, and he finally comes to think of her as ”his adopted daughter, his poor child of the Marshalsea hushed to rest.” Oh dear, oh dear – the question might rather be whether there is room on Little Dorrit’s pedestal for yet another father.

On his way to Twickenham, Arthur runs into Daniel Doyce, and the two continue their way together. We learn this of the engineer:

”It was at first difficult to lead him to speak about himself, and he put off Arthur's advances in that direction by admitting slightly, oh yes, he had done this, and he had done that, and such a thing was of his making, and such another thing was his discovery, but it was his trade, you see, his trade; until, as he gradually became assured that his companion had a real interest in his account of himself, he frankly yielded to it.“

When I read this, I thought that in some way there is a similarity between Daniel Doyce and Mr. Pancks in that they both love and live for their profession, and they both think that being alive and excelling at their profession is one and the same thing. Maybe Arthur could learn one or two things from these two people since his pensive and scrupulous attitude and his disenchantment with life are on the brink of leading him into idleness, or at least, into inaction and indecision. Luckily, it turns out that Daniel Doyce is thinking of having another business partner, whose task it would be to look after the Shop in terms of business. I have a feeling that Arthur is going to be this partner of Doyce’s, and that Doyce’s enterprising manner will help overcome certain doubts of Clennam’s as to whether man should toil or not just contemplate the unfair dealings of life’s Circumlocution Offices:

”’Hadn't he better let it go?’ said Clennam.

‘He can't do it,’ said Doyce, shaking his head with a thoughtful smile. ‘It's not put into his head to be buried. It's put into his head to be made useful. You hold your life on the condition that to the last you shall struggle hard for it. Every man holds a discovery on the same terms.’

‘That is to say,’ said Arthur, with a growing admiration of his quiet companion, ‘you are not finally discouraged even now?’

‘I have no right to be, if I am,’ returned the other. ‘The thing is as true as it ever was.’”

When they finally arrive at Mr. Clennam’s place, Arthur finds it very expressive of the Meagles household in terms of coziness and comfort. The narrator remarks:

”There was even the later addition of a conservatory sheltering itself against it, uncertain of hue in its deep-stained glass, and in its more transparent portions flashing to the sun's rays, now like fire and now like harmless water drops; which might have stood for Tattycoram.”

Speaking of Tattycoram, is it not interesting that Tattycoram is not sitting at the table with the Meagles and their guests when they are having their dinner, but that she has to run some errands in the house? She also calls Pet, whose name in fact is Minnie (not much better than Pet, if you ask me), “Miss”, which makes her rather a servant than an adopted sister. We also see more signs of Tattycoram’s so-called bad temper, which is often aroused when the Meagleses make a lot of their daughter, and which shows itself in ”an angry and contemptuous frown upon her face, that changed its beauty into ugliness.” The narrator, however, seems to take sides with Pet and the Meagleses, as is shown in this scene:

”’Oh, Tatty!’ murmured her mistress, ‘take your hands away. I feel as if some one else was touching me!’

She said it in a quick involuntary way, but half playfully, and not more petulantly or disagreeably than a favourite child might have done, who laughed next moment. Tattycoram set her full red lips together, and crossed her arms upon her bosom.”

This scene occurs when the company are sitting together, discussing their time in Marseilles and wondering what might have become of their fellow travellers. When the talk centres on Miss Wade, Tatty, who happens to be in the room, tells them all that Miss Wade has written to her offering her support and help whenever she feels herself hurt. She also lets out that she has once met Miss Wade near the church. Pet says that the thought of Miss Wade gives her a feeling of horror, and Mr. Meagles shows that he understands Tattycoram’s fits of anger and discontent, given that she has never experienced parental love. If he does, though, he has a wonderfully awkward way of treating Tattycoram, always advising her to count twenty-five when she finds herself in a bad mood. The Meagleses may not know it, but if you ask me, they have taken up Tattycoram not so much for her own sake but more to pander to the spoilt comforts of their insipid daughter. I have a feeling that we have not seen the last of Miss Wade.

We also learn that Mr. Meagles, when he was still active, was a successful and clear-sighted businessman, working for a bank – thus he may pass as a foil to Mrs. Clennam: While the latter has neglected more humane qualities in business life, the former has successfully managed to combine both efficiency and humaneness. Be that as it may, it is Mr. Meagles, who finally advises Clennam and Doyce to enter into a partnership.

We also learn that Arthur, in the course of his stay at the Meagleses’ house, considers the question whether it is advisable or not to allow himself to fall in love with Pet. He is not sure whether he may not be too old for Pet but on the other hand he thinks that Mr. Meagles has a high regard for him and that the Meagleses would therefore not feel too sorry at the thought of having to release their daughter into marriage.

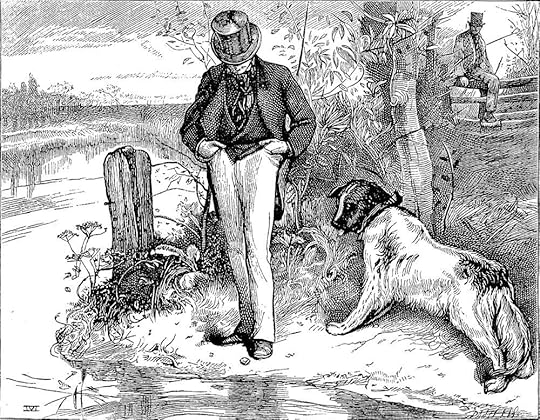

The following Chapter, “Nobody’s Rival”, tells us about the second day of Arthur’s weekend at the Meagleses’. Early next morning, Arthur goes for another walk, and on coming back home, he meets a young man and his Newfoundland dog, waiting for the ferry. This young man is called, as will become clear later, Henry Gowan, and he is an artist. He is described in the following way:

”This gentleman looked barely thirty. He was well dressed, of a sprightly and gay appearance, a well-knit figure, and a rich dark complexion. As Arthur came over the stile and down to the water's edge, the lounger glanced at him for a moment, and then resumed his occupation of idly tossing stones into the water with his foot. There was something in his way of spurning them out of their places with his heel, and getting them into the required position, that Clennam thought had an air of cruelty in it. Most of us have more or less frequently derived a similar impression from a man's manner of doing some very little thing: plucking a flower, clearing away an obstacle, or even destroying an insentient object.”

This does not forebode too well, and we may be sure that Mr. Gowan will cause some trouble, maybe for Arthur, maybe for somebody else. When Arthur arrives at the Meagleses’ place, he finds that this young man is already there, and although he is quite friendly with Arthur, the latter still has some reason to regard him with displeasure. Just look at this:

”’It's new to you, I believe?’ said this Gowan, when Arthur had extolled the place.

‘Quite new. I made acquaintance with it only yesterday afternoon.’

‘Ah! Of course this is not its best aspect. It used to look charming in the spring, before they went away last time. I should like you to have seen it then.‘“

Now you can call me paranoid but I think that Mr. Gowan’s stressing the fact that he has seen the cottage more often than Arthur is meant to show Clennam that he is a regular visitor to the Meagleses and is on more confidential and intimate terms with Pet than Clennam will ever be. In the course of the chapter, Clennam learns from Doyce that Mr. Meagles is indeed worried about Mr. Gowan’s interest in Pet, that, in fact, Mr. Gowan has made official advances with regard to the daughter of the house, but these have never been given an official answer up to now, and that one reason for Mr. Meagles’s taking Pet on long travels is his determination to keep Mr. Gowan away from her. Whether this is due to Mr. Gowan’s person in particular or whether Mr. Meagles is not willing to allow Pet any close relations with a possible suitor in general is a question that cannot be solved for Arthur right now. We also learn that Mr. Gowan is a remote relation of the Barnacles and that he was brought up in a spirit of idleness, his parents being granted sinecures by the government through the Barnacles’ intervention. One thing that might further discourage Arthur is that Pet makes a great show of Mr. Gowan’s dog Lion – when she cannot very well make a great show of Mr. Gowan.

All this makes Arthur more and more arrive at the conclusion that it might not be very wise to allow himself to fall in love with Pet, but such resolutions hardly have a way of being put into practice. Mr. Gowan also proves a damper on the little society in another way because he brings Clarence Barnacle for dinner, and although Mr. Meagles was very indignant at the Circumlocution Office as such, he feels highly flattered at having such an illustrious guest at his table. At the same time, Clarence Barnacle warns Mr. Gowan to beware of Arthur, whom he considers to be a Radical, on the grounds that he had the temerity of walking into the Circumlocution Office and wanting to know, you know.

It’s probably just a coincidence, but the chapter ends with rainfall.

By the way, what do you think of Clennam’s blossoming interest in Pet? It has never been mentioned in any of the preceding chapters – and now it is dwelled on by our narrator with a vengeance. Did this sudden love interest on Arthur’s side come as an afterthought to Dickens? And what do you think of Mr. Meagles, his treatment of Tatty and his fawning to young Barnacle?

”This gentleman looked barely thirty. He was well dressed, of a sprightly and gay appearance, a well-knit figure, and a rich dark complexion. As Arthur came over the stile and down to the water's edge, the lounger glanced at him for a moment, and then resumed his occupation of idly tossing stones into the water with his foot. There was something in his way of spurning them out of their places with his heel, and getting them into the required position, that Clennam thought had an air of cruelty in it. Most of us have more or less frequently derived a similar impression from a man's manner of doing some very little thing: plucking a flower, clearing away an obstacle, or even destroying an insentient object.”

This does not forebode too well, and we may be sure that Mr. Gowan will cause some trouble, maybe for Arthur, maybe for somebody else. When Arthur arrives at the Meagleses’ place, he finds that this young man is already there, and although he is quite friendly with Arthur, the latter still has some reason to regard him with displeasure. Just look at this:

”’It's new to you, I believe?’ said this Gowan, when Arthur had extolled the place.

‘Quite new. I made acquaintance with it only yesterday afternoon.’

‘Ah! Of course this is not its best aspect. It used to look charming in the spring, before they went away last time. I should like you to have seen it then.‘“

Now you can call me paranoid but I think that Mr. Gowan’s stressing the fact that he has seen the cottage more often than Arthur is meant to show Clennam that he is a regular visitor to the Meagleses and is on more confidential and intimate terms with Pet than Clennam will ever be. In the course of the chapter, Clennam learns from Doyce that Mr. Meagles is indeed worried about Mr. Gowan’s interest in Pet, that, in fact, Mr. Gowan has made official advances with regard to the daughter of the house, but these have never been given an official answer up to now, and that one reason for Mr. Meagles’s taking Pet on long travels is his determination to keep Mr. Gowan away from her. Whether this is due to Mr. Gowan’s person in particular or whether Mr. Meagles is not willing to allow Pet any close relations with a possible suitor in general is a question that cannot be solved for Arthur right now. We also learn that Mr. Gowan is a remote relation of the Barnacles and that he was brought up in a spirit of idleness, his parents being granted sinecures by the government through the Barnacles’ intervention. One thing that might further discourage Arthur is that Pet makes a great show of Mr. Gowan’s dog Lion – when she cannot very well make a great show of Mr. Gowan.

All this makes Arthur more and more arrive at the conclusion that it might not be very wise to allow himself to fall in love with Pet, but such resolutions hardly have a way of being put into practice. Mr. Gowan also proves a damper on the little society in another way because he brings Clarence Barnacle for dinner, and although Mr. Meagles was very indignant at the Circumlocution Office as such, he feels highly flattered at having such an illustrious guest at his table. At the same time, Clarence Barnacle warns Mr. Gowan to beware of Arthur, whom he considers to be a Radical, on the grounds that he had the temerity of walking into the Circumlocution Office and wanting to know, you know.

It’s probably just a coincidence, but the chapter ends with rainfall.

By the way, what do you think of Clennam’s blossoming interest in Pet? It has never been mentioned in any of the preceding chapters – and now it is dwelled on by our narrator with a vengeance. Did this sudden love interest on Arthur’s side come as an afterthought to Dickens? And what do you think of Mr. Meagles, his treatment of Tatty and his fawning to young Barnacle?

Chapter 18 introduces another lover, this time we are dealing with “Little Dorrit’s Lover”, and a rather melancholy and sorrowful suitor it is. His name is John Chivery, which is redolent of such different words as “chivalry” and “shivery” and leaves us wondering as to which direction this John Chivery, or Young John, is going to go.

John Chivery is the son of a turnkey, and his mother keeps a small tobacco shop, which enables him to present some cigars to the Father of the Marshalsea from time to time and bask in the presence of that worthy man. He has been in love with Amy for a long time already, already admiring her when she was sitting in her little armchair next to the benevolent turnkey. He is one year older than Amy, and used to be her playmate when they were both children. In the course of years, however, his admiration for Little Dorrit has turned into love and into some kind of oddly romanticized vision of their future life:

”Though too humble before the ruler of his heart to be sanguine, Young John had considered the object of his attachment in all its lights and shades. Following it out to blissful results, he had descried, without self-commendation, a fitness in it. Say things prospered, and they were united. She, the child of the Marshalsea; he, the lock-keeper. There was a fitness in that. Say he became a resident turnkey. She would officially succeed to the chamber she had rented so long. There was a beautiful propriety in that. It looked over the wall, if you stood on tip-toe; and, with a trellis-work of scarlet beans and a canary or so, would become a very Arbour. There was a charming idea in that.“

One wonders if Young John might also have fallen in love with Amy, had she not been the child of the Marshalsea, but later in the chapter, one notices that John’s love is genuine. In his dreams about their future life, there is also the strange kind of fear of the real world that seems to be typical of many inmates of the Marshalsea, and that must have been annoying to as enterprising a man as Charles Dickens:

”With the world shut out (except that part of it which would be shut in); with its troubles and disturbances only known to them by hearsay, as they would be described by the pilgrims tarrying with them on their way to the Insolvent Shrine; with the Arbour above, and the Lodge below; they would glide down the stream of time, in pastoral domestic happiness.”

This tendency to narrow one’s own scope of action and reflexion down to the prison also shows up again in the last sentence of the inscription John has composed for his gravestone:

”There she was born, There she lived, There she died.”

Linking her fate to John’s might not be the best decision Little Dorrit could make. Likewise Young John could probably do better than linking himself to the Dorrit family because they all – except Amy – take advantage of him knowing, and yet pretending not to know, about Young John’s infatuation. Mr. Dorrit even seems to encourage it in order to get his measly cigars. That’s why he also tells Young John – when the craven lover one day has finally made up his mind to reveal his feelings to Amy – that his daughter has taken a walk to the Iron Bridge, where – as he adds – she has taken a habit of going to very often lately.

When John arrives at the Iron Bridge and when he meets Little Dorrit, he immediately notices that he is the last person on earth she would have liked to see there, and this insight rather takes him aback and prevents him from having his say the way he intended to. Amy, however, uses this opportunity to break it gently to him that he should not found his hopes on her. She also adds, seeing that he is genuinely stricken by her words and that his affection for her is real, that she would rely on his never taking the opportunity to meet her at the Iron Bridge again, now that he knows (through her father) that she likes this place so much.

John Chivery sadly accepts his fate and on his way home is engaged in composing another inscription for his tomb, this time a very desperate one.

So next to Mr. Gowan (and Clennam?) we have another suitor in the novel, although in John’s case we have rather a comic figure than a possible threat. I don’t know about you but I did not particularly like the rather condescending way the narrator treats Young John. It becomes quite obvious in passages like this one:

”There really was a genuineness in the poor fellow, and a contrast between the hardness of his hat and the softness of his heart (albeit, perhaps, of his head, too), that was moving. Little Dorrit entreated him to disparage neither himself nor his station, and, above all things, to divest himself of any idea that she supposed hers to be superior. This gave him a little comfort.“

I was sorry both for John (for obvious reasons) but also for Little Dorrit, who had to realize that her own father would capitalize on John’s illusions for his cigars (the proverbial lentil dish). At the same time, I could not help noticing that Little Dorrit seems to have taken a liking to the Iron Bridge – a rather recent one, as is twice hinted in the text. Hmmmm …

John Chivery is the son of a turnkey, and his mother keeps a small tobacco shop, which enables him to present some cigars to the Father of the Marshalsea from time to time and bask in the presence of that worthy man. He has been in love with Amy for a long time already, already admiring her when she was sitting in her little armchair next to the benevolent turnkey. He is one year older than Amy, and used to be her playmate when they were both children. In the course of years, however, his admiration for Little Dorrit has turned into love and into some kind of oddly romanticized vision of their future life:

”Though too humble before the ruler of his heart to be sanguine, Young John had considered the object of his attachment in all its lights and shades. Following it out to blissful results, he had descried, without self-commendation, a fitness in it. Say things prospered, and they were united. She, the child of the Marshalsea; he, the lock-keeper. There was a fitness in that. Say he became a resident turnkey. She would officially succeed to the chamber she had rented so long. There was a beautiful propriety in that. It looked over the wall, if you stood on tip-toe; and, with a trellis-work of scarlet beans and a canary or so, would become a very Arbour. There was a charming idea in that.“

One wonders if Young John might also have fallen in love with Amy, had she not been the child of the Marshalsea, but later in the chapter, one notices that John’s love is genuine. In his dreams about their future life, there is also the strange kind of fear of the real world that seems to be typical of many inmates of the Marshalsea, and that must have been annoying to as enterprising a man as Charles Dickens:

”With the world shut out (except that part of it which would be shut in); with its troubles and disturbances only known to them by hearsay, as they would be described by the pilgrims tarrying with them on their way to the Insolvent Shrine; with the Arbour above, and the Lodge below; they would glide down the stream of time, in pastoral domestic happiness.”

This tendency to narrow one’s own scope of action and reflexion down to the prison also shows up again in the last sentence of the inscription John has composed for his gravestone:

”There she was born, There she lived, There she died.”

Linking her fate to John’s might not be the best decision Little Dorrit could make. Likewise Young John could probably do better than linking himself to the Dorrit family because they all – except Amy – take advantage of him knowing, and yet pretending not to know, about Young John’s infatuation. Mr. Dorrit even seems to encourage it in order to get his measly cigars. That’s why he also tells Young John – when the craven lover one day has finally made up his mind to reveal his feelings to Amy – that his daughter has taken a walk to the Iron Bridge, where – as he adds – she has taken a habit of going to very often lately.

When John arrives at the Iron Bridge and when he meets Little Dorrit, he immediately notices that he is the last person on earth she would have liked to see there, and this insight rather takes him aback and prevents him from having his say the way he intended to. Amy, however, uses this opportunity to break it gently to him that he should not found his hopes on her. She also adds, seeing that he is genuinely stricken by her words and that his affection for her is real, that she would rely on his never taking the opportunity to meet her at the Iron Bridge again, now that he knows (through her father) that she likes this place so much.

John Chivery sadly accepts his fate and on his way home is engaged in composing another inscription for his tomb, this time a very desperate one.

So next to Mr. Gowan (and Clennam?) we have another suitor in the novel, although in John’s case we have rather a comic figure than a possible threat. I don’t know about you but I did not particularly like the rather condescending way the narrator treats Young John. It becomes quite obvious in passages like this one:

”There really was a genuineness in the poor fellow, and a contrast between the hardness of his hat and the softness of his heart (albeit, perhaps, of his head, too), that was moving. Little Dorrit entreated him to disparage neither himself nor his station, and, above all things, to divest himself of any idea that she supposed hers to be superior. This gave him a little comfort.“

I was sorry both for John (for obvious reasons) but also for Little Dorrit, who had to realize that her own father would capitalize on John’s illusions for his cigars (the proverbial lentil dish). At the same time, I could not help noticing that Little Dorrit seems to have taken a liking to the Iron Bridge – a rather recent one, as is twice hinted in the text. Hmmmm …

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 15..."

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 15..."Poor Affery, always going about with her apron over her head, and still she can't get away from those two clever ones. It's a shame she isn't more practical, like the Meagles, and less superstitious, and she might face her fears in a bolder way. If she can't ever trust herself and her own senses, who can she trust? (Or should that be whom? ...)

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 16..."

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 16..."I loved the description of the Meagles' cottage (though it sounds as if it's more of a country house with lots of guest rooms, etc.). What a contrast Arthur's dinner there was to his dinner at the Casby home! Was Arthur enamored with Pet specifically, or more with the vision of a lovely home and loving family? Certainly the Meagles are happy together (Tattycoram aside, as she usually is), which is something Arthur seems to have never experienced.

Arthur is doing a lot of stock-taking. He seems to be going through a mid-life crisis, and the transition following his father's demise has put him at a cross-roads. It's interesting to watch him try to figure out his future, both romantically and in business.

Tristram wrote: "The following Chapter, “Nobody’s Rival”..."

Tristram wrote: "The following Chapter, “Nobody’s Rival”..."No one seems to like Gowan. He's done nothing malicious, and yet there's something about him that sits wrong with our established characters, and their suspicions of him cause the hair on my neck to stand up a bit, as well. Certainly, his relations to the Barnacles can't be a good thing. But he has a Newfie, so I feel like he can't be all bad. But then, in Oliver Twist, Bill Sikes had Bulls-eye, which ended up telling us more about the loyalty of a dog than the character of its master. Time will tell.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 18 ...“Little Dorrit’s Lover”..."

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 18 ...“Little Dorrit’s Lover”..."In the BBC production of Little Dorrit, John Chivery is one of my favorite characters. I was rather taken aback by Amy's rather shoddy treatment of him in this chapter. She had several moments when she was less than sensitive and thoughtful towards him. His updated eulogy was heartbreaking. So far, he's the only character whose deferential treatment towards Mr. Dorrit I can justify and forgive. But Mr. Dorrit's selfish manipulations of John's feelings for Amy made me dislike Dorrit all the more. Selling out your daughter for a steady supply of cigars... what a piece of work!

Mary Lou wrote: "Certainly the Meagles are happy together (Tattycoram aside, as she usually is)."

Mary Lou wrote: "Certainly the Meagles are happy together (Tattycoram aside, as she usually is)."Ha!

I enjoyed these chapters a lot, especially the first, with its eerie attention to the light of Mrs. Clennam's room as a beacon drawing in who knows what that she is waiting for, and the power game clearly afoot between Mrs. C and Flintwinch.

I enjoyed these chapters a lot, especially the first, with its eerie attention to the light of Mrs. Clennam's room as a beacon drawing in who knows what that she is waiting for, and the power game clearly afoot between Mrs. C and Flintwinch. While I think Dickens overdoes the protestations that Arthur has decided not to fall for Pet, I'm fine with this development, mostly because I really don't want an Arthur-Amy pairing. He may be twice the age of both of them, but Pet at least has people to look after her interests (if not very well, since Mr. M doesn't doesn't appear ready to take a direct stand against Gowan). Arthur's interest in Amy was feeling almost--not exactly predatory, but it was like he could pick her off a shelf and purchase her. I don't particularly care for Pet but despite the dead twin she still seems a lot less of a walking sentimental catastrophe than Amy is.

Also just yesterday I was thinking what happened to Miss Wade, anyway? And now here she is, apparently ready to wreak some havoc through Tattycoram. I wish I had some confidence that a little havoc in her life would improve Pet, but oh well. At least we are likely to get more Tattycoram.

I approve of the prospective Doyce-Clennam pairing. Finally Clennam has something to do! And also, for a business-inept savant, Doyce does at least seem to have Clennam's number. That dialogue they have about Gowan at the end of the chapter is very funny.

Tristram wrote: "‘He can't do it,’ said Doyce, shaking his head with a thoughtful smile. ‘It's not put into his head to be buried. It's put into his head to be made useful. You hold your life on the condition that to the last you shall struggle hard for it. Every man holds a discovery on the same terms.’

Tristram wrote: "‘He can't do it,’ said Doyce, shaking his head with a thoughtful smile. ‘It's not put into his head to be buried. It's put into his head to be made useful. You hold your life on the condition that to the last you shall struggle hard for it. Every man holds a discovery on the same terms.’‘That is to say,’ said Arthur, with a growing admiration of his quiet companion, ‘you are not finally discouraged even now?’

‘I have no right to be, if I am,’ returned the other. ‘The thing is as true as it ever was.’"

Doyce is very stalwart, isn't he? Good for him.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow Curiosities,

This week, we are going to have four Chapters and although we are already about one fifth into the novel, we are still getting new characters. In Chapter 15, however, we a..."

I continue to enjoy the Gothic feel of the Clennam house. We have sights and sounds and even touches on Mrs Flintwinch’s shoulder. The house is a character and to watch how it holds and reflects many of the characters is intriguing. With Affery holding her apron over her head as Mary Lou notes and the light in Mrs Clennam’s window acting as a beacon for something or someone as Julie notes we see in different ways how the house is a central feature of the story. Mrs Clennam is wheelchair bound and the house appears to stand and rely on beams to support it. House and character become more fully entwined.

The added touch of Amy, the innocent, yet somewhat mysterious visitor/employee who comes to the house further intensifies the Gothic touches. What are the secrets of this house and its inhabitants?

This week, we are going to have four Chapters and although we are already about one fifth into the novel, we are still getting new characters. In Chapter 15, however, we a..."

I continue to enjoy the Gothic feel of the Clennam house. We have sights and sounds and even touches on Mrs Flintwinch’s shoulder. The house is a character and to watch how it holds and reflects many of the characters is intriguing. With Affery holding her apron over her head as Mary Lou notes and the light in Mrs Clennam’s window acting as a beacon for something or someone as Julie notes we see in different ways how the house is a central feature of the story. Mrs Clennam is wheelchair bound and the house appears to stand and rely on beams to support it. House and character become more fully entwined.

The added touch of Amy, the innocent, yet somewhat mysterious visitor/employee who comes to the house further intensifies the Gothic touches. What are the secrets of this house and its inhabitants?

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 16, which deals with “Nobody’s Weakness“, leads us back to Arthur, who one fine Saturday morning in spring, decides that it would be a good occasion to renew his acquaintance with the Meagl..."

Tristram

I never thought about how one could see Pancks and Doyce as having any similarities. To me they were more opposites in terms of their motivations and their methods of conducting their lives. You are right to point out how their share a passion for their separate professions. That gives me more to consider and think about.

Arthur, while he presents as a rather meek chap so far, has surprised me with his emotional life. First, we learn that at one time he had a close relationship with Flora. In this chapter he seems to be self-denying a very keen interest in Pet. Hovering in the back of his mind and actions we have Amy who, I suspect, is more than his “adopted daughter.”

There is certainly a marked contrast between the Clennam home and the Meagles’s residence. Again, the home apparently can be seen as an indicator of its inhabitants.

We have a suitor for Pet and Arthur trying to convince himself that he has no interest in her and John Chivery eagerly pursuing Amy while Arthur dithers his way around her. Arthur needs to step up his game or get off the playing field. Of course, our hero needs a love interest so we must await further developments.

Tristram

I never thought about how one could see Pancks and Doyce as having any similarities. To me they were more opposites in terms of their motivations and their methods of conducting their lives. You are right to point out how their share a passion for their separate professions. That gives me more to consider and think about.

Arthur, while he presents as a rather meek chap so far, has surprised me with his emotional life. First, we learn that at one time he had a close relationship with Flora. In this chapter he seems to be self-denying a very keen interest in Pet. Hovering in the back of his mind and actions we have Amy who, I suspect, is more than his “adopted daughter.”

There is certainly a marked contrast between the Clennam home and the Meagles’s residence. Again, the home apparently can be seen as an indicator of its inhabitants.

We have a suitor for Pet and Arthur trying to convince himself that he has no interest in her and John Chivery eagerly pursuing Amy while Arthur dithers his way around her. Arthur needs to step up his game or get off the playing field. Of course, our hero needs a love interest so we must await further developments.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 18 introduces another lover, this time we are dealing with “Little Dorrit’s Lover”, and a rather melancholy and sorrowful suitor it is. His name is John Chivery, which is redolent of such d..."

Thank heavens for this chapter. While poor John apparently will never win the hand of Amy, his heart’s desire, there is some comic and light-hearted relief in this chapter. So far, this novel has been rather thin of humour. Affery holding her apron over her head is humourous, but in the wider context the chapter is one of gloom and intensity. Similarly, John Chivery is an earnest young man with emotions and dreams for a future with Amy. I believe he would be a good husband. To find only enjoyment and humour in Amy’s rejection of his attempted proposal is rather mean-spirited.

So where is the broad humour of the Pickwick Papers, or even a character like Skimpole or Boythorn or Miss Flite in Bleak House? To me, in this novel, Dickens is much darker, much bleaker, much more angry. What is with Miss Wade? She hovers in the fringes and yet infects the novel with her presence. If we go back to the first chapter of this novel we will realize it opened in a blaze of heat, in a jail, in a foreign country. How does this link to where we are in the novel right now? All we know is that someone evil is coming. The rickety Clennam house has a light that beckons into the night.

What great suspense is created by Dickens in these early chapters.

Thank heavens for this chapter. While poor John apparently will never win the hand of Amy, his heart’s desire, there is some comic and light-hearted relief in this chapter. So far, this novel has been rather thin of humour. Affery holding her apron over her head is humourous, but in the wider context the chapter is one of gloom and intensity. Similarly, John Chivery is an earnest young man with emotions and dreams for a future with Amy. I believe he would be a good husband. To find only enjoyment and humour in Amy’s rejection of his attempted proposal is rather mean-spirited.

So where is the broad humour of the Pickwick Papers, or even a character like Skimpole or Boythorn or Miss Flite in Bleak House? To me, in this novel, Dickens is much darker, much bleaker, much more angry. What is with Miss Wade? She hovers in the fringes and yet infects the novel with her presence. If we go back to the first chapter of this novel we will realize it opened in a blaze of heat, in a jail, in a foreign country. How does this link to where we are in the novel right now? All we know is that someone evil is coming. The rickety Clennam house has a light that beckons into the night.

What great suspense is created by Dickens in these early chapters.

Julie wrote: "I enjoyed these chapters a lot, especially the first, with its eerie attention to the light of Mrs. Clennam's room as a beacon drawing in who knows what that she is waiting for, and the power game ..."

Julie wrote: "I enjoyed these chapters a lot, especially the first, with its eerie attention to the light of Mrs. Clennam's room as a beacon drawing in who knows what that she is waiting for, and the power game ..."OH, why are you opposed to an Arthur-Amy wedding/friendship, ect. Whatever? He has said that he regards her somewhat as a father, did not he? I am ok with a firm relationship between the two. Arthur can become more responsible, and Amy can have someone to lean on. peace, janz

Peacejanz wrote: "Julie wrote: "I enjoyed these chapters a lot, especially the first, with its eerie attention to the light of Mrs. Clennam's room as a beacon drawing in who knows what that she is waiting for, and t..."

Peacejanz wrote: "Julie wrote: "I enjoyed these chapters a lot, especially the first, with its eerie attention to the light of Mrs. Clennam's room as a beacon drawing in who knows what that she is waiting for, and t..."Friendship, yes. But not romance. Especially if he sees her as a daughter.

He's kind of all over the place, isn't he? Flora? Amy? Minnie? Someone who pops up in the next chapter? Who's it going to be?

Yes, you are right. Arthur is not my idea of a good marriage candidate - but I would take him for a friend - if he goes to Walmart and buys some backbone and guts and keeps thinking carefully about himself and those around him. More long walks by himself. Ok - I get your point. No romance. Is Arthur to always be without romance? Just a solid friend. peace, janz

Yes, you are right. Arthur is not my idea of a good marriage candidate - but I would take him for a friend - if he goes to Walmart and buys some backbone and guts and keeps thinking carefully about himself and those around him. More long walks by himself. Ok - I get your point. No romance. Is Arthur to always be without romance? Just a solid friend. peace, janz

Peacejanz wrote: "No romance. Is Arthur to always be without romance?"

Peacejanz wrote: "No romance. Is Arthur to always be without romance?"Somebody should set him up with Miss Wade!

Oh, I do not think of Miss Wade as his mother. Rather his contemporary. She manages to travel alone, take care of herself and maybe take care of others. After all she contacted Tattycorn - not the Mangles (I know I have misspelled it), Miss Wade might help him grow up and become strong as a husband? peace, janz

Oh, I do not think of Miss Wade as his mother. Rather his contemporary. She manages to travel alone, take care of herself and maybe take care of others. After all she contacted Tattycorn - not the Mangles (I know I have misspelled it), Miss Wade might help him grow up and become strong as a husband? peace, janz

Peacejanz wrote: "Oh, I do not think of Miss Wade as his mother. Rather his contemporary. She manages to travel alone, take care of herself and maybe take care of others. After all she contacted Tattycorn - not the ..."

Peacejanz wrote: "Oh, I do not think of Miss Wade as his mother. Rather his contemporary. She manages to travel alone, take care of herself and maybe take care of others. After all she contacted Tattycorn - not the ..."I'd say you're both right. Miss Wade is far more independent than Mrs. C, but on the other hand she also appears to be the kind of dominant personality that Flintwinch said Mrs. C was in her marriage to Arthur's father.

But I don't really see Miss Wade as a serious candidate, as much as I would enjoy being surprised, and as much as Arthur seems predisposed to fall in love with whatever's in front of him.

How do you know Miss Wade is bitter and angry? She may be but I do not recall reading anything that told me that. I know she is independent - traveling alone and taking care of herself. Give me an example of her being bitter or angry. Of course, we have only seen her a couple of times. I think of her as an adult self-assured woman of the world. And I think she could help Arthur. She is trying to help Tattycorem. Help me out here. peace, janz

How do you know Miss Wade is bitter and angry? She may be but I do not recall reading anything that told me that. I know she is independent - traveling alone and taking care of herself. Give me an example of her being bitter or angry. Of course, we have only seen her a couple of times. I think of her as an adult self-assured woman of the world. And I think she could help Arthur. She is trying to help Tattycorem. Help me out here. peace, janz

Peacejanz wrote: "How do you know Miss Wade is bitter and angry? She may be but I do not recall reading anything that told me that. I know she is independent - traveling alone and taking care of herself. Give me an ..."

Peacejanz wrote: "How do you know Miss Wade is bitter and angry? She may be but I do not recall reading anything that told me that. I know she is independent - traveling alone and taking care of herself. Give me an ..."Here she is:

‘Oh!’ said he. ‘Dear me! But that’s a pity, isn’t it?’

‘That I am not credulous?’ said Miss Wade.

‘Not exactly that. Put it another way. That you can’t believe it easy to forgive.’

‘My experience,’ she quietly returned, ‘has been correcting my belief in many respects, for some years. It is our natural progress, I have heard.’

‘Well, well! But it’s not natural to bear malice, I hope?’ said Mr Meagles, cheerily.

‘If I had been shut up in any place to pine and suffer, I should always hate that place and wish to burn it down, or raze it to the ground. I know no more.’

Here she is again:

‘In our course through life we shall meet the people who are coming to meet us, from many strange places and by many strange roads,’ was the composed reply; ‘and what it is set to us to do to them, and what it is set to them to do to us, will all be done.’

There was something in the manner of these words that jarred upon Pet’s ear. It implied that what was to be done was necessarily evil, and it caused her to say in a whisper, ‘O Father!’ and to shrink childishly, in her spoilt way, a little closer to him. This was not lost on the speaker.

‘Your pretty daughter,’ she said, ‘starts to think of such things. Yet,’ looking full upon her, ‘you may be sure that there are men and women already on their road, who have their business to do with you, and who will do it. Of a certainty they will do it. They may be coming hundreds, thousands, of miles over the sea there; they may be close at hand now; they may be coming, for anything you know or anything you can do to prevent it, from the vilest sweepings of this very town.’

With the coldest of farewells, and with a certain worn expression on her beauty that gave it, though scarcely yet in its prime, a wasted look, she left the room.

Thanks, Julie, for saving me the time of looking up passages. It's interesting that I felt the bitterness coming off her in waves, while Janz saw her in a completely different light.

Thanks, Julie, for saving me the time of looking up passages. It's interesting that I felt the bitterness coming off her in waves, while Janz saw her in a completely different light. The passages you selected also echoed those we read about the Clennam house this week. It's very ominous, isn't it? A dark force seems to be coming towards our little group, and the narrator isn't being subtle about it. That Miss Wade says it may be coming from "the vilest sweepings of this very town," certainly indicates that it is Rigaud who will soon cross paths with these good people. Is Miss Wade in league with him somehow, or just prescient? Or is he the reason she's bitter? I can't wait to find out.

Mary Lou wrote: "certainly indicates that it is Rigaud who will soon cross paths with these good people. Is Miss Wade in league with him somehow, or just prescient? Or is he the reason she's bitter? I can't wait to find out."

Mary Lou wrote: "certainly indicates that it is Rigaud who will soon cross paths with these good people. Is Miss Wade in league with him somehow, or just prescient? Or is he the reason she's bitter? I can't wait to find out."Yes. Lots of stories in play. You know they're going to intersect because it's a novel and a Dickens novel at that--but how and why?

Thanks, Julie. I got it. I just slid over those passages (as I can do more and more as I age). Reading them now makes me realize that you are right. Maybe we only saw a little of her (my secret hoping for good to apprear??) I think Mama Clennam is a meaner bitch and I would be scared of her. Can't believe Little Amy puts up with her - except Amy is the martyr. Thanks for taking me back. peace, janz

Thanks, Julie. I got it. I just slid over those passages (as I can do more and more as I age). Reading them now makes me realize that you are right. Maybe we only saw a little of her (my secret hoping for good to apprear??) I think Mama Clennam is a meaner bitch and I would be scared of her. Can't believe Little Amy puts up with her - except Amy is the martyr. Thanks for taking me back. peace, janz

Mary Lou wrote: "I was rather taken aback by Amy's rather shoddy treatment of him in this chapter. She had several moments when she was less than sensitive and thoughtful towards him."

It's good to know that I was not the only one to feel that way about Amy's treatment of young Chivery. It seems to me that she has invested all her sensibililty in her father, who does not really fully deserve it, and has not much left of it for Chivery. Saying that, however, it is rather awkward a situation for her to tell Chivery that he should not set his hopes on her. How do you ever do such a thing the right way? Chivery, with his love for the melodramatic, as in his obession about his epitaph, and his weak eye, is clearly one of Dickens's "ridiculous swains", like Mr. Toots and Mr. Guppy - but at least he is not as mercenary and scheming as the latter, and maybe he will get a more grateful share in events that are to come?

About Arthur as a lover, I have this to add: Like Julie, I think that his interest in Amy has something like picking her off a shelf - because after all, she is unprotected and may be thankful for any support she is given once she has learnt to lower her drawbridge. Apart from that I wonder that in both cases, Amy and Pet, Arthur has developed interest in a woman that is not half as old as he is. Why is that? Can it only be a matter of looks? Or is it that Arthur somehow senses that in such a relationship he will always, in some way, be the more experienced, the more "powerful" partner, something that he certainly is not in his relationship with his own mother? It happens quite often in Dickens: Walter Gay is older than Florence, Dr. Strong is older than his wife - is this just a coincidence, or is this a pattern that is supposed to tell us something?

It's good to know that I was not the only one to feel that way about Amy's treatment of young Chivery. It seems to me that she has invested all her sensibililty in her father, who does not really fully deserve it, and has not much left of it for Chivery. Saying that, however, it is rather awkward a situation for her to tell Chivery that he should not set his hopes on her. How do you ever do such a thing the right way? Chivery, with his love for the melodramatic, as in his obession about his epitaph, and his weak eye, is clearly one of Dickens's "ridiculous swains", like Mr. Toots and Mr. Guppy - but at least he is not as mercenary and scheming as the latter, and maybe he will get a more grateful share in events that are to come?

About Arthur as a lover, I have this to add: Like Julie, I think that his interest in Amy has something like picking her off a shelf - because after all, she is unprotected and may be thankful for any support she is given once she has learnt to lower her drawbridge. Apart from that I wonder that in both cases, Amy and Pet, Arthur has developed interest in a woman that is not half as old as he is. Why is that? Can it only be a matter of looks? Or is it that Arthur somehow senses that in such a relationship he will always, in some way, be the more experienced, the more "powerful" partner, something that he certainly is not in his relationship with his own mother? It happens quite often in Dickens: Walter Gay is older than Florence, Dr. Strong is older than his wife - is this just a coincidence, or is this a pattern that is supposed to tell us something?

Mary Lou wrote: "No one seems to like Gowan. He's done nothing malicious, and yet there's something about him that sits wrong with our established characters, and their suspicions of him cause the hair on my neck to stand up a bit, as well."

There certainly is the Barnacle connection, but that alone does not really mean much, does it? And yet, from the very beginning, we are told that there is something cruel in the way that Gowan dislodges those stones before he kicks them into the river. Apart from that, he is very self-assured, e.g. when he gives Arthur to understand that he himself is a regular guest at the Meagleses' household and when he talks of other people - in this case Clarence Barnacle - with a mixture of condescension and careless good-will. He is also a man who does not really seem to be prepared to devote himself to a profession but wants to get on in life the simple way - not exactly the kind of husband that will prove responsible and reliable. All in all, the less we see of him, the better ...

There certainly is the Barnacle connection, but that alone does not really mean much, does it? And yet, from the very beginning, we are told that there is something cruel in the way that Gowan dislodges those stones before he kicks them into the river. Apart from that, he is very self-assured, e.g. when he gives Arthur to understand that he himself is a regular guest at the Meagleses' household and when he talks of other people - in this case Clarence Barnacle - with a mixture of condescension and careless good-will. He is also a man who does not really seem to be prepared to devote himself to a profession but wants to get on in life the simple way - not exactly the kind of husband that will prove responsible and reliable. All in all, the less we see of him, the better ...

Peter wrote: "I never thought about how one could see Pancks and Doyce as having any similarities. To me they were more opposites in terms of their motivations and their methods of conducting their lives. You are right to point out how their share a passion for their separate professions. That gives me more to consider and think about."

Maybe, men and their professions in life are another motif that is deeply entwined with the structure of Little Dorrit? We have both Daniel Doyce and Pancks as examples of men who are implicitly devoted to their profession and their line of business in life. One difference between them may be that Doyce is convinced that his invention is good in itself, is "the true thing" and that therefore he has to brave the insolence of office and see to it that his invention will be put to proper use one day. In doing that, he is not so much concerned about the profits he may reap from it but simply in thinking things up, in constructing and inventing. He is a bit like Mr. Rouncewell, with the difference that the latter was also an apt businessman. Pancks, however, is more concerned with doing his job well and does not give too many thoughts about the implications this has for others - like Mr. Casby's tenants, who may suffer from his readiness to look into his employer's interests. Therefore, Pancks may do good as well as bad, depending on whom he works for - but work he will like a clockwork.

Arthur, on the other hand, has still not found a profession to devote himself to. At the beginning of the novel, we saw him come to the decision that what he has been doing all his life was not what he wanted to do for the rest of it. Maybe that is because he thinks more like Doyce - in that he wants to do something worth doing. He is clearly more reflecting than Pancks.

Last, not least there is a bunch of men who don't do anything and are quite happy with it - Dorrit senior and Tip as well as Gowan. These are clearly the more despicable characters.

Maybe, men and their professions in life are another motif that is deeply entwined with the structure of Little Dorrit? We have both Daniel Doyce and Pancks as examples of men who are implicitly devoted to their profession and their line of business in life. One difference between them may be that Doyce is convinced that his invention is good in itself, is "the true thing" and that therefore he has to brave the insolence of office and see to it that his invention will be put to proper use one day. In doing that, he is not so much concerned about the profits he may reap from it but simply in thinking things up, in constructing and inventing. He is a bit like Mr. Rouncewell, with the difference that the latter was also an apt businessman. Pancks, however, is more concerned with doing his job well and does not give too many thoughts about the implications this has for others - like Mr. Casby's tenants, who may suffer from his readiness to look into his employer's interests. Therefore, Pancks may do good as well as bad, depending on whom he works for - but work he will like a clockwork.

Arthur, on the other hand, has still not found a profession to devote himself to. At the beginning of the novel, we saw him come to the decision that what he has been doing all his life was not what he wanted to do for the rest of it. Maybe that is because he thinks more like Doyce - in that he wants to do something worth doing. He is clearly more reflecting than Pancks.

Last, not least there is a bunch of men who don't do anything and are quite happy with it - Dorrit senior and Tip as well as Gowan. These are clearly the more despicable characters.

Peter wrote: "So where is the broad humour of the Pickwick Papers, or even a character like Skimpole or Boythorn or Miss Flite in Bleak House?"

You are right, Peter: Little Dorrit is even bleaker than Bleak House on the whole. The only other bit of humour that has been granted to the reader was the chapter about the Circumlocusts ... ahem Circumlocutionists, and that was more in the vein of scathing satire. Maybe, with age coming on, Dickens had just become more angry and disillusioned and on the whole, he lost his sense for innocent humour. The days of Pickwick have long passed - even though both novels give us glimpses into a debtor's prison.

You are right, Peter: Little Dorrit is even bleaker than Bleak House on the whole. The only other bit of humour that has been granted to the reader was the chapter about the Circumlocusts ... ahem Circumlocutionists, and that was more in the vein of scathing satire. Maybe, with age coming on, Dickens had just become more angry and disillusioned and on the whole, he lost his sense for innocent humour. The days of Pickwick have long passed - even though both novels give us glimpses into a debtor's prison.

Peacejanz wrote: "Oh, I do not think of Miss Wade as his mother. Rather his contemporary. She manages to travel alone, take care of herself and maybe take care of others. After all she contacted Tattycorn - not the ..."

Miss Wade would eat him alive - and have no great trouble, given that there are not many bones in him.

Miss Wade would eat him alive - and have no great trouble, given that there are not many bones in him.

Peacejanz wrote: "Thanks, Julie. I got it. I just slid over those passages (as I can do more and more as I age). Reading them now makes me realize that you are right. Maybe we only saw a little of her (my secret hop..."

I even see some similarities between Miss Wade and Mrs. Clennam - what Miss Wade says about the forces of Fate is mirrored to a certain extent in Mrs. Clennam's rigid and inhuman version of Christianity. Both women are ready to hate anyone that dares oppose them, but there is one difference: While Miss Wade says that she would hate a place she was confined in and wish to raze it to the ground, Mrs. Clennam seems to take a grim delight in being confined to her room and wheelchair and even derives a twisted pride from it.

I even see some similarities between Miss Wade and Mrs. Clennam - what Miss Wade says about the forces of Fate is mirrored to a certain extent in Mrs. Clennam's rigid and inhuman version of Christianity. Both women are ready to hate anyone that dares oppose them, but there is one difference: While Miss Wade says that she would hate a place she was confined in and wish to raze it to the ground, Mrs. Clennam seems to take a grim delight in being confined to her room and wheelchair and even derives a twisted pride from it.

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "I never thought about how one could see Pancks and Doyce as having any similarities. To me they were more opposites in terms of their motivations and their methods of conducting their..."

Yes. We see Pancks, Doyce and Chivery as men of work. Flintwinch is more mystery than engaged. If we step back from these men it is hard to find anyone who works. Arthur may be close to a job opportunity but who else actually works? Meagles is retired, the Barnacles have cultivated the art of inaction, Tip is little more than a con man, Plornish is willing but limited in his opportunities, and Gowan appears to be a flaneur. What can one say about Dorrit? Is he the worst of everyone?

The concept of work, work that has value is, so far in the novel, in short supply.

Yes. We see Pancks, Doyce and Chivery as men of work. Flintwinch is more mystery than engaged. If we step back from these men it is hard to find anyone who works. Arthur may be close to a job opportunity but who else actually works? Meagles is retired, the Barnacles have cultivated the art of inaction, Tip is little more than a con man, Plornish is willing but limited in his opportunities, and Gowan appears to be a flaneur. What can one say about Dorrit? Is he the worst of everyone?

The concept of work, work that has value is, so far in the novel, in short supply.

Flaneur -- lovely word. idler, dawdler, loafer. I had to look it up. Thanks to Peter. One learns all the time. peacejanz

Flaneur -- lovely word. idler, dawdler, loafer. I had to look it up. Thanks to Peter. One learns all the time. peacejanz

Haha! I confused "flaneur" with "sapeur" and wondered what passage I'd missed that had Peter thinking Gowan looked like a Congolese dandy. An interesting visual. :-)

Haha! I confused "flaneur" with "sapeur" and wondered what passage I'd missed that had Peter thinking Gowan looked like a Congolese dandy. An interesting visual. :-)

Peacejanz wrote: "Flaneur -- lovely word. idler, dawdler, loafer. I had to look it up. Thanks to Peter. One learns all the time. peacejanz"

Hi Peacejanz and Mary Lou

Yes, It is a neat word to describe a certain form or style of living. I first encountered it during a study of 19C French art. It seems many French males strove to make being a flaneur a way to travel through life.

Hi Peacejanz and Mary Lou

Yes, It is a neat word to describe a certain form or style of living. I first encountered it during a study of 19C French art. It seems many French males strove to make being a flaneur a way to travel through life.

I can't believe I got this far in life without owning an apron. I don't know how I got through a day without throwing one over my head.

Tristram wrote: "This made me wonder whether Mrs. Clennam may not be waiting for some unknown person .."

Maybe she has a lover.

Maybe she has a lover.

Tristram wrote: " And what do you think of Mr. Meagles, his treatment of Tatty and his fawning to young Barnacle?..."

Well thanks to you pointing out the names Tatty, Pet and Minnie - which I wouldn't mind if I didn't think of a mouse every time I saw it - I think he is terrible at naming people.

Well thanks to you pointing out the names Tatty, Pet and Minnie - which I wouldn't mind if I didn't think of a mouse every time I saw it - I think he is terrible at naming people.

Tristram wrote: "Maybe, men and their professions in life are another motif that is deeply entwined with the structure of Little Dorrit?..."

I have been thinking of the men and their professions, or at least Mr. Dorrit and his profession. What was it? What did he do that was so important that even now he is far above every one else he knows? John feels as if he is not good enough for Amy and she tells him she never thought of herself and her family to be superior to his. It seems if that is true she is the only member of the Dorrit clan to feel that way. I don't get it.

I have been thinking of the men and their professions, or at least Mr. Dorrit and his profession. What was it? What did he do that was so important that even now he is far above every one else he knows? John feels as if he is not good enough for Amy and she tells him she never thought of herself and her family to be superior to his. It seems if that is true she is the only member of the Dorrit clan to feel that way. I don't get it.

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "This made me wonder whether Mrs. Clennam may not be waiting for some unknown person .."

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "This made me wonder whether Mrs. Clennam may not be waiting for some unknown person .."Maybe she has a lover."

lol

Kim wrote: ""What did he do that was so important that even now he is far above every one else he knows?"

Kim wrote: ""What did he do that was so important that even now he is far above every one else he knows?"He was born a GENTLEMAN, that's what he did.

It doesn't even require work.

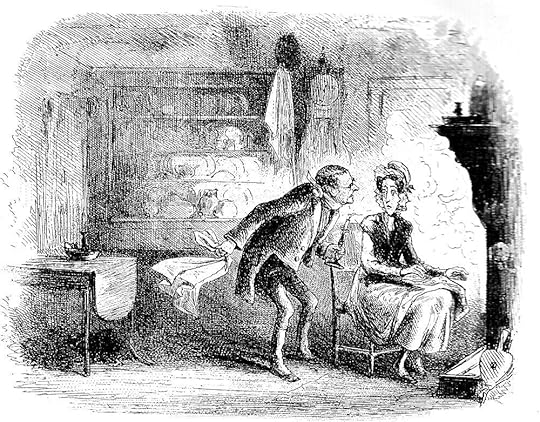

Mr. and Mrs. Flintwich

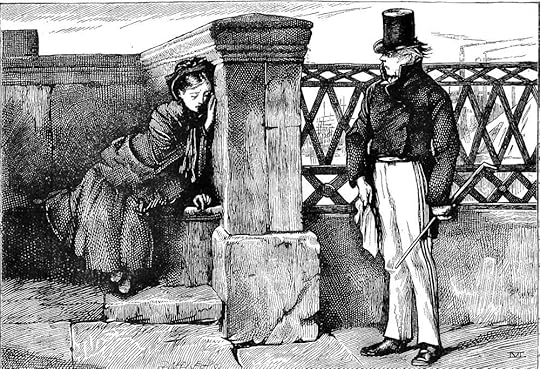

Chapter 15, Book 1

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Here the sound of the wheeled chair was heard upon the floor, and Affery's bell rang with a hasty jerk.

More afraid of her husband at the moment than of the mysterious sound in the kitchen, Affery crept away as lightly and as quickly as she could, descended the kitchen stairs almost as rapidly as she had ascended them, resumed her seat before the fire, tucked up her skirt again, and finally threw her apron over her head. Then the bell rang once more, and then once more, and then kept on ringing; in despite of which importunate summons, Affery still sat behind her apron, recovering her breath.

At last Mr Flintwinch came shuffling down the staircase into the hall, muttering and calling 'Affery woman!' all the way. Affery still remaining behind her apron, he came stumbling down the kitchen stairs, candle in hand, sidled up to her, twitched her apron off, and roused her.

"Oh Jeremiah!" cried Affery, waking. "What a start you gave me!"

"What have you been doing, woman?" inquired Jeremiah. "You've been rung for fifty times."

"Oh Jeremiah," said Mistress Affery, "I have been a-dreaming!" — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 15.

Commentary:

The picture offers an interesting juxtaposition of the aggressive, Punch-like husband, Jeremiah Flintwinch, and the startled Affery, from whom he had just removed the apron with which she covers her face when terrified, or sleeping. Dickens excels at depicting such contrary dispositions linked by domestic service — Benjamin Britain and Clemency Newcome in The Battle of Life, the Christmas Book for 1846, being just such another couple, although Britain's wooden nature does not approach the flamboyant, hectoring posture of Mr. Flintwinch, Mrs. Clennam's clerk, business partner, and confidant. Phiz has captured his essence here: "A short, bald old man, in a high-shouldered black coat and waistcoat, drab breeches, and long drab gaiters . . . There was nothing about him in the way of decoration". Phiz's Flintwinch may be "bent and dried", but his glance is decidedly keen and his manner "knowing," to the point of superciliousness, a dour variation on the tricky servant of classical comedy.

Jeremiah Flintwinch, Affery's irascible husband, harbors a secret from his wife, but in her sleep she apprehends his confidential conversations with their employer, the dour Mrs. Clennam, although the contents of these dialogues so confuse her that she is sure that she must have dreamed them, as well as the strange noises emanating from the walls of the house, quite unlike the "rats, cats, water, [and] drains" that her husband proposes as the cause. Affery is utterly bewildered how, in her fugue state, Jeremiah can be so assertive with Mrs. Clennam, and what secret the pair are keeping from her that concerns Little Dorrit.

....if my husband ever suggests there are rats in the house I'm leaving.

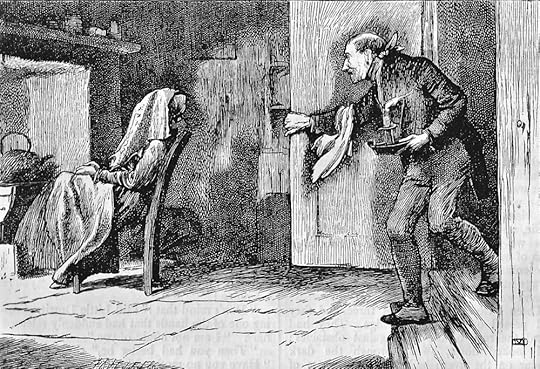

He came stumbling down the kitchen stairs, candle in hand.

Chapter 15, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

More afraid of her husband at the moment than of the mysterious sound in the kitchen, Affery crept away as lightly and as quickly as she could, descended the kitchen stairs almost as rapidly as she had ascended them, resumed her seat before the fire, tucked up her skirt again, and finally threw her apron over her head. Then the bell rang once more, and then once more, and then kept on ringing; in despite of which importunate summons, Affery still sat behind her apron, recovering her breath.

At last Mr. Flintwinch came shuffling down the staircase into the hall, muttering and calling 'Affery woman!' all the way. Affery still remaining behind her apron, he came stumbling down the kitchen stairs, candle in hand, sidled up to her, twitched her apron off, and roused her.

"Oh Jeremiah!" cried Affery, waking. "What a start you gave me!"

"What have you been doing, woman?" inquired Jeremiah. "You've been rung for fifty times."

"Oh Jeremiah," said Mistress Affery, "I have been a-dreaming!"

Reminded of her former achievement in that way, Mr. Flintwinch held the candle to her head, as if he had some idea of lighting her up for the illumination of the kitchen. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 15.

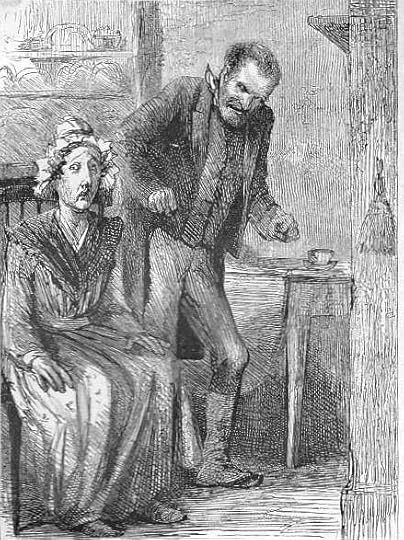

Mr. and Mrs. Flintwinch

Chapter 15, Book 1

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Commentary:

The sixth illustration again introduces its subjects — Mrs. Clennam's confidential clerk, Jeremiah, and her domestic servant, Affery — in a characteristic setting (the servants' kitchen parlor, as suggested by the crockery in the cupboard and the bell-pull to the right) in Chapter 16, "Nobody's Weakness," although neither character actually appears in that chapter. Rather, Eytinge is realizing a moment from the previous chapter, "Mrs. Flintwinch Has Another Dream," when Jeremiah, having argued with his mistress (and business partner) above stairs, returns to the kitchen below stairs to awaken his wife, for whom Mrs. Clennam has been ringing in order to receive her tea. Little does Jeremiah, his fists clenched in exasperation at his wife's supposed indolence, know that the anxious Affery has, in fact, overheard the argument, and has been puzzling over it — just as the reader has. Thus, the moment captured in the illustration is likely this:

At last Mr Flintwinch came shuffling down the staircase into the hall, muttering and calling "Affery woman!" all the way. Affery still remaining behind her apron, he came stumbling down the kitchen stairs, candle in hand, sidled up to her, twitched her apron off, and roused her.

"O Jeremiah!" cried Affery, waking. "What a start you gave me!"

"What have you been doing, woman?" inquired Jeremiah. "You've been rung for fifty times."

"O Jeremiah," said Mistress Affery, "I have been a dreaming!"

However, in order to realize this oddly matched couple, Eytinge has had to draw on Dickens's description of Jeremiah Flintwinch given much earlier in the novel:

He was a short, bald old man, in a high-shouldered black coat and waistcoat, drab breeches, and long drab gaiters. He might, from his dress, have been either clerk or servant, and in fact had long been both. There was nothing about him in the way of decoration but a watch, which was lowered into the depths of its proper pocket by an old black ribbon, and had a tarnished copper key moored above it, to show where it was sunk. His head was awry, and he had a one-sided, crab-like way with him, as if his foundations had yielded at about the same time as those of the house, and he ought to have been propped up in a similar manner. [Book One, Chapter 3]

Dickens has thus furnished the illustrator with plenty of raw material for realizing the idiosyncratic Flintwinch, with his "wry neck", habit of perpetually scraping his jaws, and "demon of anger" constantly breaking out despite the owner's attempts at self-possession. However, given only her confusion and anxiety — and her tendency to hide behind her apron — to go on, Eytinge has had to base his drawing of Mistress Affery on her dominant emotions — confusion and bewilderment at her irascible husband's enigmatic actions and utterances, and her dim apprehension of some deep mystery in the house betokened by strange noises and curious movements — rather than on any particular descriptive passage. Although she is thus seized by vague anxieties and "singular dreams", Affery is nonetheless a sympathetic and not unintelligent character. Eytinge therefore must convey her "haunted state of mind" and yet render her sympathetic, for she was Arthur Clennam's nurse and is the victim of an arranged marriage; she is hectored by her employer and bullied by her brutal husband. In her analysis of the long-suffering Affery, actress Sue Johnson (who brought the character to life in the 1999 BBC One television series) has provided Eytinge's viewer with the key to understanding the mid-Victorian illustrator's interpretation of the character: terror. The old servant mentally refers to her husband and her employer as 'the clever ones', as they're always scheming together. She is terrified of both of them.

In The Radio Times, Johnson provides an analysis of the character that is wholly consistent with the look of abject fear on the face of Eytinge's Affery:

"Affery [Mrs Clennam's maid] is a sweetheart really, one of life's lost souls. She's been bullied by Flintwinch and Mrs Clennam and she's a nervous wreck. Affery is like a little bird — she's always listening and watching. Flintwinch tells her she's insane, but by the time it all unravels, she has a lot of answers."

The Ferry

Chapter 17, Book 1

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Before breakfast in the morning, Arthur walked out to look about him. As the morning was fine and he had an hour on his hands, he crossed the river by the ferry, and strolled along a footpath through some meadows. When he came back to the towing-path, he found the ferry-boat on the opposite side, and a gentleman hailing it and waiting to be taken over.