The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit, Book 1, Chp. 30-32

Chapter 31 is all about “Spirit” – and with a very remarkable specimen of spirit at that. First of all, we are introduced to yet another new character: Mr. Nandy, who is Mrs. Plornish’s father and who has been living in the workhouse ever since the Plornish family had been in financial difficulties. Dickens begins this chapter in the vein of his Sketches by Boz, i.e. by describing some typical sort of old man that can be seen in the streets of London in certain places, at certain times. We learn, among other things,

”Sometimes, on holidays towards evening, he will be seen to walk with a slightly increased infirmity, and his old eyes will glimmer with a moist and marshy light. Then the little old man is drunk. A very small measure will overset him; he may be bowled off his unsteady legs with a half-pint pot. Some pitying acquaintance—chance acquaintance very often—has warmed up his weakness with a treat of beer, and the consequence will be the lapse of a longer time than usual before he shall pass again. For the little old man is going home to the Workhouse; and on his good behaviour they do not let him out often (though methinks they might, considering the few years he has before him to go out in, under the sun); and on his bad behaviour they shut him up closer than ever in a grove of two score and nineteen more old men, every one of whom smells of all the others.“

And we, once again, realize how much Dickens hated workhouses. Then we learn that Mrs. Plornish’s father is one of these little old men and that he is “like a worn-out bird” – another of various bird and/or cage references in this novel. Old Mr. Nandy used to be a music-binder (whatever that is) with a passion for singing ditties, but life was not too kind with him, or as Dickens puts it:

He ”had seldom been able to make his way, or to see it or to pay it, or to do anything at all with it but find it no thoroughfare”.

And yet, he is a lucky man because both his daughter and his son-in-law love and admire him, show him around proudly in Bleeding Heart Yard and want to do their utmost to make it possible for him to leave the workhouse one day and start living with them again. In a way, Mr. Nandy is another old, improvident father who can rely on the love of his daughter, just like Mr. Dorrit – but there is one big difference, which makes Mr. Nandy much more endearing to the reader, namely his determination not to exploit the generosity of his family. At the beginning of the chapter, we learn that it is his birthday, and Mr. Plornish and Mr. Nandy are exchanging toasts the following way:

”’John Edward Nandy. Sir. While there's a ounce of wittles or drink of any sort in this present roof, you're fully welcome to your share on it. While there's a handful of fire or a mouthful of bed in this present roof, you're fully welcome to your share on it. If so be as there should be nothing in this present roof, you should be as welcome to your share on it as if it was something, much or little. And this is what I mean and so I don't deceive you, and consequently which is to stand out is to entreat of you, and therefore why not do it?’

To this lucid address, which Mr Plornish always delivered as if he had composed it (as no doubt he had) with enormous labour, Mrs Plornish's father pipingly replied:

‘I thank you kindly, Thomas, and I know your intentions well, which is the same I thank you kindly for. But no, Thomas. Until such times as it's not to take it out of your children's mouths, which take it is, and call it by what name you will it do remain and equally deprive, though may they come, and too soon they can not come, no Thomas, no!'’”

We may be sure that Mr. Dorrit would never have shown this greatness of spirit. But we learn that he considers himself a kind of patron to old Mr. Nandy, and so it seems natural that Amy Dorrit, on visiting the Plornishes, offers Mr. Nandy to take him to the Marshalsea so that he can meet his “patron” there. On their way, Amy meets her sister Fanny, who is absolutely indignant of seeing her walking down the streets arm in arm with a pauper, as she puts it. According to her, Amy proves that she has a penchant for low company and that she seems determined to dishonour the family name. Fanny makes sure to arrive at the prison before Amy and Mr. Nandy in order to prepare her father accordingly for their arrival, and the result is that Mr. Dorrit goes through one of his performances as a wronged father and does his utmost to make Amy feel guilty. Reading this scene made me furious indeed: Old Mr. Nandy, on his birthday, waiting outside in the yard while that feckless scrounger and impostor Dorrit is giving himself airs in his rooms, trampling on his daughter’s self-confidence, with Miss Fanny accompanying him second voice. I must say that I was also furious with Amy herself for taking it all without any sign of rebellion, and I believe that she would have given Mr. Nandy the cold shoulder from this moment on, had not her father suddenly remembered his sympathy with Mr. Nandy and asked him upstairs. Just having receiced a 10-Pound-note from Mr. Clennam, Dorrit happens to be in good spirits and orders some victuals to be brought to his place, and when Mr. Clennam arrives on the scene, they all enjoy a comfortable meal. Of course, Mr. Nandy is not allowed to sit at the table but he is prepared an extra place near the window, and in the course of the meal, Dorrit throws him the occasional condescending question to exercise his right of patron on a man, who – in my opinion – is worth a hundred Mr. Dorrits. He also takes care to make Mr. Nandy appear older, and more decrepit than himself. Eventually, old Mr. Nandy has to go back to the workhouse.

Another shadow is thrown on the party by the arrival of Mr. Tip, who chooses to cut Mr. Clennam in a very impolite way, on the grounds that this gentleman has refused to give him a loan and thus acted in a very ungentlemanly way. This triggers another histrionic fit of the Chief-Scrounger, who expatiates on Spirit and who says that Mr. Tip’s behaviour is not Christian since he should have tried Mr. Clennam’s generosity on another occasion instead of insulting him. Nevertheless, Tip and Fanny take their leave in an extremely haughty and ungracious way.

When Dorrit is required downstairs for a festive occasion, where he has to be the president or the master of ceremonies, Mr. Clennam finally has the chance of speaking with Amy in private.

”Sometimes, on holidays towards evening, he will be seen to walk with a slightly increased infirmity, and his old eyes will glimmer with a moist and marshy light. Then the little old man is drunk. A very small measure will overset him; he may be bowled off his unsteady legs with a half-pint pot. Some pitying acquaintance—chance acquaintance very often—has warmed up his weakness with a treat of beer, and the consequence will be the lapse of a longer time than usual before he shall pass again. For the little old man is going home to the Workhouse; and on his good behaviour they do not let him out often (though methinks they might, considering the few years he has before him to go out in, under the sun); and on his bad behaviour they shut him up closer than ever in a grove of two score and nineteen more old men, every one of whom smells of all the others.“

And we, once again, realize how much Dickens hated workhouses. Then we learn that Mrs. Plornish’s father is one of these little old men and that he is “like a worn-out bird” – another of various bird and/or cage references in this novel. Old Mr. Nandy used to be a music-binder (whatever that is) with a passion for singing ditties, but life was not too kind with him, or as Dickens puts it:

He ”had seldom been able to make his way, or to see it or to pay it, or to do anything at all with it but find it no thoroughfare”.

And yet, he is a lucky man because both his daughter and his son-in-law love and admire him, show him around proudly in Bleeding Heart Yard and want to do their utmost to make it possible for him to leave the workhouse one day and start living with them again. In a way, Mr. Nandy is another old, improvident father who can rely on the love of his daughter, just like Mr. Dorrit – but there is one big difference, which makes Mr. Nandy much more endearing to the reader, namely his determination not to exploit the generosity of his family. At the beginning of the chapter, we learn that it is his birthday, and Mr. Plornish and Mr. Nandy are exchanging toasts the following way:

”’John Edward Nandy. Sir. While there's a ounce of wittles or drink of any sort in this present roof, you're fully welcome to your share on it. While there's a handful of fire or a mouthful of bed in this present roof, you're fully welcome to your share on it. If so be as there should be nothing in this present roof, you should be as welcome to your share on it as if it was something, much or little. And this is what I mean and so I don't deceive you, and consequently which is to stand out is to entreat of you, and therefore why not do it?’

To this lucid address, which Mr Plornish always delivered as if he had composed it (as no doubt he had) with enormous labour, Mrs Plornish's father pipingly replied:

‘I thank you kindly, Thomas, and I know your intentions well, which is the same I thank you kindly for. But no, Thomas. Until such times as it's not to take it out of your children's mouths, which take it is, and call it by what name you will it do remain and equally deprive, though may they come, and too soon they can not come, no Thomas, no!'’”

We may be sure that Mr. Dorrit would never have shown this greatness of spirit. But we learn that he considers himself a kind of patron to old Mr. Nandy, and so it seems natural that Amy Dorrit, on visiting the Plornishes, offers Mr. Nandy to take him to the Marshalsea so that he can meet his “patron” there. On their way, Amy meets her sister Fanny, who is absolutely indignant of seeing her walking down the streets arm in arm with a pauper, as she puts it. According to her, Amy proves that she has a penchant for low company and that she seems determined to dishonour the family name. Fanny makes sure to arrive at the prison before Amy and Mr. Nandy in order to prepare her father accordingly for their arrival, and the result is that Mr. Dorrit goes through one of his performances as a wronged father and does his utmost to make Amy feel guilty. Reading this scene made me furious indeed: Old Mr. Nandy, on his birthday, waiting outside in the yard while that feckless scrounger and impostor Dorrit is giving himself airs in his rooms, trampling on his daughter’s self-confidence, with Miss Fanny accompanying him second voice. I must say that I was also furious with Amy herself for taking it all without any sign of rebellion, and I believe that she would have given Mr. Nandy the cold shoulder from this moment on, had not her father suddenly remembered his sympathy with Mr. Nandy and asked him upstairs. Just having receiced a 10-Pound-note from Mr. Clennam, Dorrit happens to be in good spirits and orders some victuals to be brought to his place, and when Mr. Clennam arrives on the scene, they all enjoy a comfortable meal. Of course, Mr. Nandy is not allowed to sit at the table but he is prepared an extra place near the window, and in the course of the meal, Dorrit throws him the occasional condescending question to exercise his right of patron on a man, who – in my opinion – is worth a hundred Mr. Dorrits. He also takes care to make Mr. Nandy appear older, and more decrepit than himself. Eventually, old Mr. Nandy has to go back to the workhouse.

Another shadow is thrown on the party by the arrival of Mr. Tip, who chooses to cut Mr. Clennam in a very impolite way, on the grounds that this gentleman has refused to give him a loan and thus acted in a very ungentlemanly way. This triggers another histrionic fit of the Chief-Scrounger, who expatiates on Spirit and who says that Mr. Tip’s behaviour is not Christian since he should have tried Mr. Clennam’s generosity on another occasion instead of insulting him. Nevertheless, Tip and Fanny take their leave in an extremely haughty and ungracious way.

When Dorrit is required downstairs for a festive occasion, where he has to be the president or the master of ceremonies, Mr. Clennam finally has the chance of speaking with Amy in private.

Chapter 32 promises us some “More Fortune-Telling” but before we get to that, we have to work ourselves through another conversation between Clennam and Amy (with poor Maggy sitting nearby). I will cut it short, though.

In the course of their conversation, Mr. Clennam says that he has noticed a more withdrawn attitude in Amy and that he would wish for her to remember that he is always there to help and support her. He presents himself in the capacity of someone much older than she, i.e. as a kind of surrogate father. This seems both to soothe and to pain Amy – the narrator makes much of an unseen dagger being stabbed into Amy, while belabouring the reader with the duller cudgel of boredom –, and unlike Mr. Clennam, the reader will have noticed by now that Amy is in love with him. Hence her question if he is Flora’s lover, which he, of course, denies.

Their conversation is brought to a close when the door opens and an exuberant – partly through spirits – Mr. Pancks pops in, smoking a cigar he is most obviously not used to. He says that he has been downstairs where the festivities are well under way but that he wanted to use this opportunity to pay his respects to Amy. His behaviour intimidates Amy, who does not know what to make of it, but Mr. Clennam seems not to feel any alarm, and so Amy soon calms down. Mr. Pancks begs Mr. Clennam for a word in private downstairs, where a hardly less exuberant (and slightly inebriated) Mr. Rugg is waiting for them. They produce some papers which seem to be of great moment for the Dorrit’s:

”’Stay!’ said Clennam in a whisper. ‘You have made a discovery.’

Mr Pancks answered, with an unction which there is no language to convey, ‘We rather think so.’

‘Does it implicate any one?’

‘How implicate, sir?’

‘In any suppression or wrong dealing of any kind?’

‘Not a bit of it.’

‘Thank God!’ said Clennam to himself. ‘Now show me.’

‘You are to understand’—snorted Pancks, feverishly unfolding papers, and speaking in short high-pressure blasts of sentences, ‘Where's the Pedigree? Where's Schedule number four, Mr Rugg? Oh! all right! Here we are.—You are to understand that we are this very day virtually complete. We shan't be legally for a day or two. Call it at the outside a week. We've been at it night and day for I don't know how long. Mr Rugg, you know how long? Never mind. Don't say. You'll only confuse me. You shall tell her, Mr Clennam. Not till we give you leave. Where's that rough total, Mr Rugg? Oh! Here we are! There sir! That's what you'll have to break to her. That man's your Father of the Marshalsea!‘“

So while we do not know as yet what these papers says and how they will influence the fortunes of the Dorrits, we might safely assume that there will be some major change soon. Unfortunately, in order to know more, we have to wait until the next instalment. Clever Mr. Dickens!

In the course of their conversation, Mr. Clennam says that he has noticed a more withdrawn attitude in Amy and that he would wish for her to remember that he is always there to help and support her. He presents himself in the capacity of someone much older than she, i.e. as a kind of surrogate father. This seems both to soothe and to pain Amy – the narrator makes much of an unseen dagger being stabbed into Amy, while belabouring the reader with the duller cudgel of boredom –, and unlike Mr. Clennam, the reader will have noticed by now that Amy is in love with him. Hence her question if he is Flora’s lover, which he, of course, denies.

Their conversation is brought to a close when the door opens and an exuberant – partly through spirits – Mr. Pancks pops in, smoking a cigar he is most obviously not used to. He says that he has been downstairs where the festivities are well under way but that he wanted to use this opportunity to pay his respects to Amy. His behaviour intimidates Amy, who does not know what to make of it, but Mr. Clennam seems not to feel any alarm, and so Amy soon calms down. Mr. Pancks begs Mr. Clennam for a word in private downstairs, where a hardly less exuberant (and slightly inebriated) Mr. Rugg is waiting for them. They produce some papers which seem to be of great moment for the Dorrit’s:

”’Stay!’ said Clennam in a whisper. ‘You have made a discovery.’

Mr Pancks answered, with an unction which there is no language to convey, ‘We rather think so.’

‘Does it implicate any one?’

‘How implicate, sir?’

‘In any suppression or wrong dealing of any kind?’

‘Not a bit of it.’

‘Thank God!’ said Clennam to himself. ‘Now show me.’

‘You are to understand’—snorted Pancks, feverishly unfolding papers, and speaking in short high-pressure blasts of sentences, ‘Where's the Pedigree? Where's Schedule number four, Mr Rugg? Oh! all right! Here we are.—You are to understand that we are this very day virtually complete. We shan't be legally for a day or two. Call it at the outside a week. We've been at it night and day for I don't know how long. Mr Rugg, you know how long? Never mind. Don't say. You'll only confuse me. You shall tell her, Mr Clennam. Not till we give you leave. Where's that rough total, Mr Rugg? Oh! Here we are! There sir! That's what you'll have to break to her. That man's your Father of the Marshalsea!‘“

So while we do not know as yet what these papers says and how they will influence the fortunes of the Dorrits, we might safely assume that there will be some major change soon. Unfortunately, in order to know more, we have to wait until the next instalment. Clever Mr. Dickens!

Chapter 30:

Chapter 30:What is the Clennam's business, and with whom do they associate in France who would vouch for Rigaud/Blandois to the extent that they would just loan him - what was it? £50 sterling? That's quite a bit of money in the mid 19th century. Rigaud's interest in the watch, the portrait, and the House of Clennam itself is not casual. I hearken back to this ominous quote of Miss Wade's:

...you may be sure that there are men and women already on their road, who have their business to do with you, and who will do it. Of a certainty they will do it. They may be coming hundreds, thousands, of miles over the sea there; they may be close at hand now; they may be coming, for anything you know or anything you can do to prevent it, from the vilest sweepings of this very town.

Was this a general sentiment, or does the charitable Miss Wade know something about Rigaud and his business with the House of Clennam?

Tristram wrote: "I quite liked the clever allusion to the stranger’s way of lolling on a window-seat with his drawn-up knees and think it would even have been cleverer, had the narrator foreborne to make the direct reference to Rigaud. ..."

I had this same thought, Tristram. The allusion was strong enough that Dickens didn't have to help us out with it, and it would have been more powerful if he'd let us savor it on our own.

Chapter 31:

Chapter 31:This chapter made me want to throw something or punch someone. What a horrible and ridiculous family the Dorrits are.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 32 promises us some “More Fortune-Telling” ..."

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 32 promises us some “More Fortune-Telling” ..."Looking back on our discussion about what Amy's fairy tale meant, it becomes obvious here that Tristram was correct. ("When I'm wrong, I say I'm wrong." Dr. Houseman) Obviously Flora's ramblings about her relationship with Arthur were misinterpreted by Amy. So, now she realizes that he isn't interested in Flora, and he's dismissed his non-relationship with some unknown person thinking that he's too old and the door to love and marriage has closed for him. What will Amy do with this new information?

Was anyone else kind of creeped out by the exchange between Arthur and Amy? It seemed entirely too intimate for a patron/father figure to be having with this young girl. Was it just the times, or does Arthur truly have a problem with boundaries? He seems completely obtuse when it comes to realizing how Amy might be interpreting this interest in her and her family. I don't remember feeling this way in past readings, but this time around Arthur is coming across as invasive. In fact, it seems to be a theme in this novel -- lots of people getting in other people's business.

Pancks... Being privy to his kitchen table conspiracy, I'm not completely befuddled, but Amy surely must be. He's an odd bird who likes to speak in riddles. I hope he'll sober up soon and give us a straightforward account of what he and his friends have discovered. He seems delighted. Clennam seems relieved. How will the Dorrits react to whatever news he will bring?

PS And what is Pancks interest in all of this? What suspicions did he have that led him to put so much time and energy into this project?

PS And what is Pancks interest in all of this? What suspicions did he have that led him to put so much time and energy into this project?

Mary Lou wrote: "PS And what is Pancks interest in all of this? What suspicions did he have that led him to put so much time and energy into this project?"

Mary Lou wrote: "PS And what is Pancks interest in all of this? What suspicions did he have that led him to put so much time and energy into this project?"I would also like to know this.

Tristram wrote: "This seems both to soothe and to pain Amy – the narrator makes much of an unseen dagger being stabbed into Amy, while belabouring the reader with the duller cudgel of boredom –, and unlike Mr. Clennam, the reader will have noticed by now that Amy is in love with him."

Tristram wrote: "This seems both to soothe and to pain Amy – the narrator makes much of an unseen dagger being stabbed into Amy, while belabouring the reader with the duller cudgel of boredom –, and unlike Mr. Clennam, the reader will have noticed by now that Amy is in love with him."As you all know, this is not the outcome I desired, but worse still is having it dragged out like this (cudgel cudgel cudgel). Just TALK to him, Amy.

I did find Arthur's ever-present nobility in proclaiming himself too aged to fall in love (*this* guy? who's thrown himself in the path of every thornless young woman in the book?)--to be comically entertaining. I'm not sure I'm supposed to feel that way about it, but then again I'm not sure I'm not.

Tristram wrote: "Unfortunately, in order to know more, we have to wait until the next instalment. Clever Mr. Dickens!"

Tristram wrote: "Unfortunately, in order to know more, we have to wait until the next instalment. Clever Mr. Dickens!"I do enjoy a good cliffhanger! It was difficult to stop this week.

Peacejanz wrote: ""thornless young woman" ??? What is this? Innocent? youthful?peace, janz"

Peacejanz wrote: ""thornless young woman" ??? What is this? Innocent? youthful?peace, janz"Not likely to disagree with him. ;)

I remember reading this book for the first time (aaaaaaages ago), and all through the first book I was just waiting for Arthur to swoop in, marry Amy, and rescue her from her horrible family. I didn't like her father even then (and I detest him more now, with his emotional manipulation here, there and everywhere).

This time I just find him ... weird, stalkery, stomping boundaries, and I really don't see what Amy likes about him. The turnkey would have rolled over in his grave, I am sure.

And indeed, what is Pancks' deal?

This time I just find him ... weird, stalkery, stomping boundaries, and I really don't see what Amy likes about him. The turnkey would have rolled over in his grave, I am sure.

And indeed, what is Pancks' deal?

The appearance of Blandois adds a very sinister tone and mood to this chapter. He seems like a shadow, or an evil ghost-like presence that hovers over the novel. He must have some important connection to the plot otherwise Dickens would not keep presenting him in chapters. He is like a cat, lounging in windows, entering homes on the sly, curious of objects such as watches and places and rooms. What can his endgame be? How is he able to extract money from Mrs Clennam with seeming ease? Is there a connection between Blandois and Flintwitch? So many questions but no answers.

And then he is gone. We have not heard the last of him.

And then he is gone. We have not heard the last of him.

Mary Lou wrote: "PS And what is Pancks interest in all of this? What suspicions did he have that led him to put so much time and energy into this project?"

This is the 1,000,000 dollar question! From all we know about Pancks, he seems to be a sober businessman who just does his duty because he is paid for it and wants to give back what his employer can expect for his money. He is not paid to meddle with Amy's business, and he hardly knows Amy in the first place. This is all very mysterious and threadbare to me.

This is the 1,000,000 dollar question! From all we know about Pancks, he seems to be a sober businessman who just does his duty because he is paid for it and wants to give back what his employer can expect for his money. He is not paid to meddle with Amy's business, and he hardly knows Amy in the first place. This is all very mysterious and threadbare to me.

Julie wrote: "Peacejanz wrote: ""thornless young woman" ??? What is this? Innocent? youthful?peace, janz"

Not likely to disagree with him. ;)"

How can you disagree with a person like Clennam who has so little to say? ;-)

Not likely to disagree with him. ;)"

How can you disagree with a person like Clennam who has so little to say? ;-)

Peter wrote: "We have not heard the last of him."

It would be quite a pity if we had because he brings a lot of suspense into the novel and relieves us from people like the Meagleses, Amy Dorrit and Arthur whom we are actually supposed to like but who - I am speaking for myself here - make me go up the wall with impatience.

It would be quite a pity if we had because he brings a lot of suspense into the novel and relieves us from people like the Meagleses, Amy Dorrit and Arthur whom we are actually supposed to like but who - I am speaking for myself here - make me go up the wall with impatience.

Likable people do not make for interesting reading, unless or until they find themselves in peril. I don't wish trouble on nice people in real life, but I relish it in fiction. ;-)

Likable people do not make for interesting reading, unless or until they find themselves in peril. I don't wish trouble on nice people in real life, but I relish it in fiction. ;-)

Mary Lou wrote: "Likable people do not make for interesting reading, unless or until they find themselves in peril. I don't wish trouble on nice people in real life, but I relish it in fiction. ;-)"

Mary Lou wrote: "Likable people do not make for interesting reading, unless or until they find themselves in peril. I don't wish trouble on nice people in real life, but I relish it in fiction. ;-)"See, right now I'm definitely craving a book with nice people who are kind to each other. I just don't find the Meagles very nice and Amy/Arthur very believable.

Actually I kind of like Arthur, who is such an odd combination of insight and blind haplessness. And I do think he's growing a bit as a character, moving out from under his complaints that his parents ruined his life and into making himself useful. Amy may not have asked for his help but Doyce did, if indirectly.

Sounds like you need a "Wind in the Willows" interlude, Julie. I daresay we could all use some kinder, gentler literary moments just now.

Sounds like you need a "Wind in the Willows" interlude, Julie. I daresay we could all use some kinder, gentler literary moments just now.

Mary Lou wrote: "Sounds like you need a "Wind in the Willows" interlude, Julie. I daresay we could all use some kinder, gentler literary moments just now."

Mary Lou wrote: "Sounds like you need a "Wind in the Willows" interlude, Julie. I daresay we could all use some kinder, gentler literary moments just now."That sounds just about right!

Interesting how in Chapter 32 Dickens slips in some not so subtle physical gestures between Arthur and Amy.

Clennam begins by moving “to sit by the side of Little Dorrit.” He then “Gently put his hand upon her work and said dear little Dorrit let me lay it down.“ As little Dorrit trembles Clennam says “my own little Dorrit … compassionately.“ Still later Clennam assures little Dorrit that he would do anything “to save you a moment’s heartache.“ Then we read Clennam smiles and touches Amy with his hand.

As the chapter continues we see Clennam call Little Dorrit “child“ Clennam tells Amy that he is aware of his age. I wonder what the purpose of that information is?

Arthur tells Amy that he hopes she trusts him. Why would he say this? Amy tells Arthur “that nothing can touch you without touching me; that nothing can make you happy or unhappy, but it but just make me, who I am so grateful to you the same” Arthur heard the thrill in her voice “he saw her ernest face, he saw her clear true eyes, he saw the quickened bosom that would have joyfully thrown its self before him to receive a mortal wound directed at his breast.“

Arthur sees Amy in a new light. “He saw the devoted little creature with her worn shoes, in her common dress, in her jailhouse home; a slender child in body a strong heroine in soul; And the light of her domestic story made all else dark to him.”

Maggie mentions the story of the princess and her secret. Clennam wants to know what princess. The truth is, at least to me, is simple. Amy is the princess, Clennam is her prince, and their lives are inextricably bound together from this point forward. Much of the novel remains to be read but I do not think there is much question about who will marry the princess. Perhaps the only question of their relationship will be can they live happily ever after. That remains to be seen.

As the chapter ends we learn from Pancks that Amy’s father is about to receive a king’s ransom in money. What part of the coming narrative will his daughter, the exiled princess, play in the new chapter in the story of the Dorrit’s?

Clennam begins by moving “to sit by the side of Little Dorrit.” He then “Gently put his hand upon her work and said dear little Dorrit let me lay it down.“ As little Dorrit trembles Clennam says “my own little Dorrit … compassionately.“ Still later Clennam assures little Dorrit that he would do anything “to save you a moment’s heartache.“ Then we read Clennam smiles and touches Amy with his hand.

As the chapter continues we see Clennam call Little Dorrit “child“ Clennam tells Amy that he is aware of his age. I wonder what the purpose of that information is?

Arthur tells Amy that he hopes she trusts him. Why would he say this? Amy tells Arthur “that nothing can touch you without touching me; that nothing can make you happy or unhappy, but it but just make me, who I am so grateful to you the same” Arthur heard the thrill in her voice “he saw her ernest face, he saw her clear true eyes, he saw the quickened bosom that would have joyfully thrown its self before him to receive a mortal wound directed at his breast.“

Arthur sees Amy in a new light. “He saw the devoted little creature with her worn shoes, in her common dress, in her jailhouse home; a slender child in body a strong heroine in soul; And the light of her domestic story made all else dark to him.”

Maggie mentions the story of the princess and her secret. Clennam wants to know what princess. The truth is, at least to me, is simple. Amy is the princess, Clennam is her prince, and their lives are inextricably bound together from this point forward. Much of the novel remains to be read but I do not think there is much question about who will marry the princess. Perhaps the only question of their relationship will be can they live happily ever after. That remains to be seen.

As the chapter ends we learn from Pancks that Amy’s father is about to receive a king’s ransom in money. What part of the coming narrative will his daughter, the exiled princess, play in the new chapter in the story of the Dorrit’s?

Tristram, I know we read this book before, I don't know how many of the group were with us then, but maybe you can tell me, did I hate the Dorrits as much as I do now back then? I can't stand any of them. I wish I could get a carriage, load anyone with the name of Dorrit into it, and send it far, far away from me. I think I just might do that, in a few days hopefully. :-)

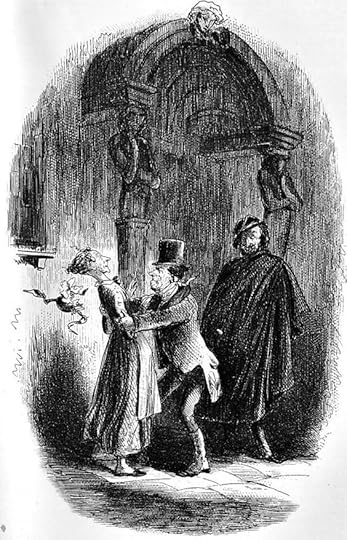

Mr. Flintwinch has a mild Attack of Irritability

Chapter 30, Book 1

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

When Mr. and Mrs. Flintwinch panted up to the door of the old house in the twilight, Jeremiah within a second of Affery, the stranger started back. "Death of my soul!" he exclaimed. "Why, how did you get here?"

Mr. Flintwinch, to whom these words were spoken, repaid the stranger's wonder in full. He gazed at him with blank astonishment; he looked over his own shoulder, as expecting to see some one he had not been aware of standing behind him; he gazed at the stranger again, speechlessly, at a loss to know what he meant; he looked to his wife for explanation; receiving none, he pounced upon her, and shook her with such heartiness that he shook her cap off her head, saying between his teeth, with grim raillery, as he did it, "Affery, my woman, you must have a dose, my woman! This is some of your tricks! You have been dreaming again, mistress. What's it about? Who is it? What does it mean! Speak out or be choked! It's the only choice I'll give you."

Supposing Mistress Affery to have any power of election at the moment, her choice was decidedly to be choked; for she answered not a syllable to this adjuration, but, with her bare head wagging violently backwards and forwards, resigned herself to her punishment. The stranger, however, picking up her cap with an air of gallantry, interposed. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 30, "The Word of a Gentleman".

Commentary:

The picture offers an interesting fusion of comic characters and a gloomy architectural setting that equates the Clennam mansion with the Marshalsea. The Punch-and-Judy husband knocks the slight hat off his wife's head while the faintly demonic Blandois, having arrived from France with a letter of credit on Clennam and Company, lurks in the shadows, waiting to be admitted.

Dickens' character seems to derive from the folk-fairytale and its later artistic versions (such as Hoffmann's) and thus in the text he gives the impression of representing a general, nontopical form of evil. Yet to this reader, at any rate, Rigaud is most successful as an artistic creation when he appears most clearly as a diminution of the devil-type, whose demonism is shown as merely a pose convenient to his philosophy of personal power and absolute self-interest. In most of Phiz's portrayals this complexity cannot emerge, and Rigaud is little more than a weakly drawn demon. But in two effective plates Phiz does complement and enhance Dickens' conception of the character. His first appearance in England as Blandois is illustrated in "Mr. Flintwinch has a mild attack of irritability" (Bk. 1, ch. 30). He has just emerged from the shadows, to give poor fearful Affery a terrible start; in this plate, Jeremiah is shaking his wife for her reaction while Blandois looks on. A preliminary drawing indicates that this was almost certainly intended first as a dark plate: it is drawn in charcoal with the kind of heavy tone that Browne rarely if ever employed for anything else; and rather than the close-up of the final version, it is a distant view of the same scene, with the figures very small but in similar positions. Perhaps the emphasis (though the sketch is too small and rough for this to be certain) was to be on the old Clennam house, which burgeons larger and larger in the novel until it comes forth as a symbol of the decay of society — reminiscent of buildings in Tom-All-Alone's. It is suggested that the next crash will likely "be a good one."

It is possible that Dickens originally intended the opening of Part IX to concentrate more upon the house, and gave Browne directions to this end, but upon having written the chapter found that the characters were more important, and correspondingly gave new directions. In the final version, the demonic aspect of Blandois is played up, both in his black cloak and in the gleam of his eyes and teeth, while the grotesque figures decorating the doorway look down upon the three characters with sinister anticipation. This illustration, even in its final form, could have been a dark plate, for it is literally dark enough; but the particular vein Dickens exploits seems better served by heavy manual shading than by the smoothness of a mechanical tint. The final version complements Dickens' text in the way it sets off against Blandois' gleaming eyes, upcurving moustache, and black cloak the rather horribly comic grotesqueness of Affery and Flintwinch — in other words, it is in a mixed vein which Phiz rarely brings off successfully in Little Dorrit. — Steig, Chapter 6, Bleak House and Little Dorrit: Iconography of Darkness".

The stranger, taking advantage of this fitful illumination of his visage, looked intently and wonderingly at him.

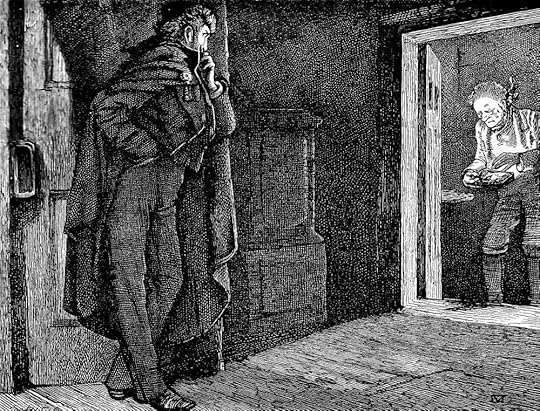

Chapter 30, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

"I am afraid," said the stranger, "I must be so troublesome as to propose a candle."

"True," assented Jeremiah. "I was going to do so. Please to stand where you are while I get one."

The visitor was standing in the doorway, but turned a little into the gloom of the house as Mr. Flintwinch turned, and pursued him with his eyes into the little room, where he groped about for a phosphorus box. When he found it, it was damp, or otherwise out of order; and match after match that he struck into it lighted sufficiently to throw a dull glare about his groping face, and to sprinkle his hands with pale little spots of fire, but not sufficiently to light the candle. The stranger, taking advantage of this fitful illumination of his visage, looked intently and wonderingly at him. Jeremiah, when he at last lighted the candle, knew he had been doing this, by seeing the last shade of a lowering watchfulness clear away from his face, as it broke into the doubtful smile that was a large ingredient in its expression.

"Be so good," said Jeremiah, closing the house door, and taking a pretty sharp survey of the smiling visitor in his turn, "as to step into my counting-house. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 30, "The Word of a Gentleman".

Commentary:

Rigaud-Blandois arrives at the Clennam mansion with letters of credit, and immediately arousing the suspicion of Jeremiah Flintwinch. In contrast to Phiz's more humorous treatment of Blandois as a comic Gallic villain in the ninth serial part, Mr. Flintwinch has a mild Attack of Irritability in the background, placing the emphasis on the comic, Punch-and-Judy husband and wife, Mahoney develops the scene from the Frenchman's point of view, thrusting Flintwinch into the lighted background, eliminating Affery entirely, and minimizing the ponderous architectural elements of the mansion's porch (particular the ornamental head in the archway and the pensive caryatids that support the arch) in the upper register of Phiz's original steel engraving. Whereas Phiz, in comic mood, had treated all three figures as mere caricatures, Mahoney treats the two men seriously, offering no suggestion of Flintwinch's splenetic outburst. Realistically, Flintwinch is not wearing his hat as he enters from the counting-house.

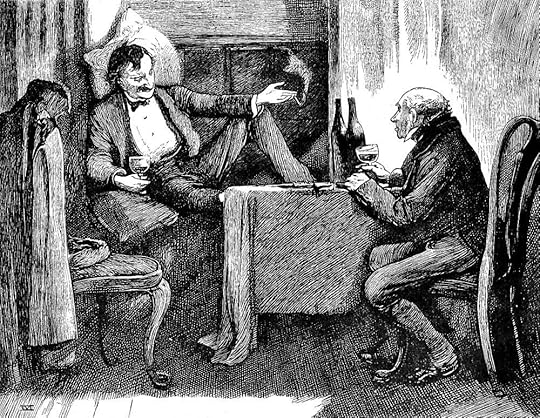

Mr. Flintwinch took a chair oppoite to him, with the table between them.

Chapter 30, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

"I have a strong presentiment that we shall become intimately acquainted. — You have no feeling of that sort yet?"

"Not yet," said Mr. Flintwinch.

Mr. Blandois, taking him by both shoulders again, rolled him about a little in his former merry way, then drew his arm through his own, and invited him to come off and drink a bottle of wine like a dear deep old dog as he was.

Without a moment's indecision, Mr. Flintwinch accepted the invitation, and they went out to the quarters where the traveller was lodged, through a heavy rain which had rattled on the windows, roofs, and pavements, ever since nightfall. The thunder and lightning had long ago passed over, but the rain was furious. On their arrival at Mr. Blandois' room, a bottle of port wine was ordered by that gallant gentleman; who (crushing every pretty thing he could collect, in the soft disposition of his dainty figure) coiled himself upon the window-seat, while Mr. Flintwinch took a chair opposite to him, with the table between them. Mr. Blandois proposed having the largest glasses in the house, to which Mr. Flintwinch assented. The bumpers filled, Mr. Blandois, with a roystering gaiety, clinked the top of his glass against the bottom of Mr. Flintwinch's, and the bottom of his glass against the top of Mr Flintwinch's, and drank to the intimate acquaintance he foresaw. Mr. Flintwinch gravely pledged him, and drank all the wine he could get, and said nothing. As often as Mr. Blandois clinked glasses (which was at every replenishment), Mr. Flintwinch stolidly did his part of the clinking, and would have stolidly done his companion's part of the wine as well as his own: being, except in the article of palate, a mere cask.

In short, Mr. Blandois found that to pour port wine into the reticent Flintwinch was, not to open him but to shut him up. Moreover, he had the appearance of a perfect ability to go on all night; or, if occasion were, all next day and all next night; whereas Mr Blandois soon grew indistinctly conscious of swaggering too fiercely and boastfully. He therefore terminated the entertainment at the end of the third bottle.

"You will draw upon us to-morrow, sir," said Mr. Flintwinch, with a business-like face at parting.

"My Cabbage," returned the other, taking him by the collar with both hands, "I'll draw upon you; have no fear. Adieu, my Flintwinch. Receive at parting;" here he gave him a southern embrace, and kissed him soundly on both cheeks; "the word of a gentleman! By a thousand Thunders, you shall see me again!"

He did not present himself next day, though the letter of advice came duly to hand. Inquiring after him at night, Mr. Flintwinch found, with surprise, that he had paid his bill and gone back to the Continent by way of Calais. Nevertheless, Jeremiah scraped out of his cogitating face a lively conviction that Mr. Blandois would keep his word on this occasion, and would be seen again. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 31, "The Word of a Gentleman".

Commentary:

Flintwinch, Mrs. Clennam's confidential clerk, is naturally suspicious of the flamboyant Frenchman with financial papers drawn on his mistress's house, and wants to gather further information about him. Having had a personal interview with the wily Mrs. Clennam, who has essentially turned his case over to her subordinate, Blandois (Rigaud's pseudonym for himself as his reputation had already preceded him to Challons when he arrived at that city in north-western France) has tea with the arch invalid, and then adjourns to his hotel-room to drink wine with Flintwinch, perhaps hoping to elicit more information about the secretive and obviously wealthy reclusive Mrs. Clennam. In spite of their drinking, Flintwinch yields no such information. Mahoney's handling of the scene is a study in contrasts with the dark, middle-aged, bearded Frenchman in evening dress but a casual posture seated opposite the older, balding English clerk in somewhat old-fashioned dress (including gaiters), a businessman straight-laced and taciturn in contrast to his voluble Gallic companion, smoking a small cigarette (as is usual in illustrations of him).

The Consumption of Port in Dickens's Works:

Curiously, the "wine" that Blandois orders is not a French vin ordinaire, but a fortified wine — port, an imported after-dinner alcoholic beverage from Portugal (Vinho do Porto) consumed by a number of other Dickens characters, including Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Corney, drinking the medicinal port in Oliver Twist, Mr. Bintrey and Mr. Walter Wilding drinking vintage port in No Thoroughfare, and The Sergeant and Uncle Pumblechook in Great Expectations. As these citations demonstrate, the imbibing of port tended to be a masculine taste, and often associated with some special occasion or toast, port being an expensive alcoholic beverage beyond the means of the working class. The imbibing of port is most common, along with the consumption of other sorts of alcoholic beverages, in Pickwick, with greatest toper of all, the dissenting minister Mr. Stiggins ("the red-nosed man") being addicted to mulled port, made with cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, mace and sugar to taste. According to The Charles Dickens Cookbook, "The final heating was usually achieved with the aid of a special 'sugar-loaf hat' described in the making of Purl", a specialty of The Six Jolly Fellowship-Porters in Our Mutual Friend, a less sophisticated mulled beverage made with spiced ale, nutmeg, ginger, sugar, and gin. Such plebeian alcoholic constituents suggest that Purl was a less costly and less sophisticated a beverage than mulled Port. Dick Swiveller in The Old Curiosity Shop is inordinately fond of purl, as Darley shows in "Marchioness, your health. You will excuse my wearing my hat. . . " (1861).

After the Treaty of Metheun in 1702, reduced tariffs on Portuguese wines gave preferential treatment to the Portuguese import in the British wine market over French wines, so that the popularity of port ("blackstrap" as it was popularly called because of its dark color and astringency), accelerated in early eighteenth century Britain, with the excise on a bottle of Port being a third less than that of a bottle of French wine. By 1717, Portuguese wines in general accounted for more than 66% of all wine imported into Great Britain, whereas French wines accounted for a mere 4%. During the Napoleonic Wars, the French even attempted to disrupt the trade by invading northern Portugal between 1807 and 1809, damaging the economy of the principal wine-growing region, Douro. After the British wine merchants of Porto fled, the trade with Great Britain was severely impaired. Although the population rebounded in Great Britain after the Congress of Vienna which ended the Anglo-French conflict, port sales in England did not rebound, leveling off to the totals of the previous century. The British had simply diversified their tastes, which included the other fortified wine, sherry, from Spain, and brandy and water — a favourite of Tony Weller, the stout coachman of The Pickwick Papers, a beverage that he, his fellows, his son Sam and the attorney Mr. Pell quaff in Hablot Knight Browne's Mr. Weller and his friends drinking to Mr. Pell (November 1837).In 1859, whereas Great Britain imported 22,546 gallons of sherry from Spain, it brought in just 2,227 gallons on wine from France, but 4,171 gallons of port from Portugal, attesting to port's continuing popularity at the time that Dickens was writing Little Dorrit.

Although in this passage from Little Dorrit Blandois orders a single bottle of port, and the pair consume two further bottles, in the Mahoney illustrationthe pair are in the process of consuming the second bottle of the fortified wine, apparently without much effect on Mr. Flintwinch, who seems bent on patiently bent on drinking the Frenchman under the table when Blandois calls a halt with the end of the third bottle. In the illustration, the expansive Blandois already seems to be succumbing, although he is hardly an inebriate of the rank of Bob Sawyer, the alcoholic medical student and pharmacist of Dickens's first novel so often shown with either a glass or bottle in his hand, as in Conviviality at Bob Sawyer's (May 1837) and Mr. Bob Sawyer's Mode of Travelling (October 1837). Ironically, Dickens himself was relatively abstemious.

...Well I now know a lot more about wine then I will ever put to use.

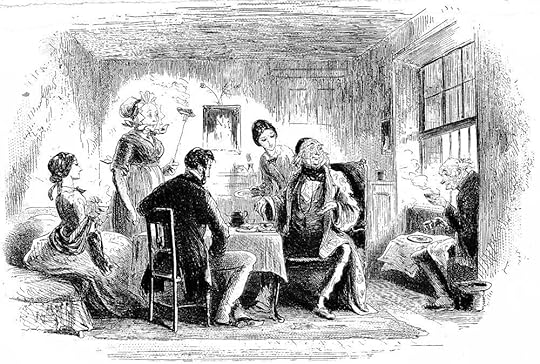

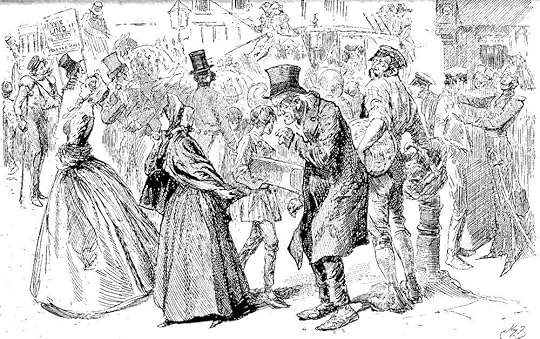

The Pensioner Entertainment

Chapter 31, Book 1

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Well, sir, this is Mrs. Plornish’s father."

"Indeed? I am glad to see him."

"You would be more glad if you knew his many good qualities, Mr. Clennam."

"I hope I shall come to know them through knowing him," said Arthur, secretly pitying the bowed and submissive figure.

"It is a holiday with him, and he comes to see his old friends, who are always glad to see him," observed the Father of the Marshalsea. Then he added behind his hand, ("Union, poor old fellow. Out for the day.")

By this time Maggy, quietly assisted by her Little Mother, had spread the board, and the repast was ready. It being hot weather and the prison very close, the window was as wide open as it could be pushed. "If Maggy will spread that newspaper on the window-sill, my dear,' remarked the Father complacently and in a half whisper to Little Dorrit, 'my old pensioner can have his tea there, while we are having ours."

So, with a gulf between him and the good company of about a foot in width, standard measure, Mrs Plornish's father was handsomely regaled. Clennam had never seen anything like his magnanimous protection by that other Father, he of the Marshalsea; and was lost in the contemplation of its many wonders.

The most striking of these was perhaps the relishing manner in which he remarked on the pensioner's infirmities and failings, as if he were a gracious Keeper making a running commentary on the decline of the harmless animal he exhibited.

"Not ready for more ham yet, Nandy? Why, how slow you are! (His last teeth," he explained to the company, "are going, poor old boy.")

At another time, he said, "No shrimps, Nandy?" and on his not instantly replying, observed, ("His hearing is becoming very defective. He'll be deaf directly.")

At another time he asked him, "Do you walk much, Nandy, about the yard within the walls of that place of yours?"

"No, sir; no. I haven't any great liking for that."

"No, to be sure," he assented. "Very natural." Then he privately informed the circle ("Legs going.")

Once he asked the pensioner, in that general clemency which asked him anything to keep him afloat, how old his younger grandchild was?

"John Edward," said the pensioner, slowly laying down his knife and fork to consider. "How old, sir? Let me think now."

The Father of the Marshalsea tapped his forehead ("Memory weak.") — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 31, "Spirit".

Commentary:

William Dorrit almost holds court with his retainers and the object his charity and patronage, Old Nandy, Mrs. Plornish's father (seated in the window, right). Phiz and Dickens thus pillory the class system, rendering it laughable by exposing the class-conscious William Dorrit's false sense of superiority with the aged music-binder who, like William, fell into debt years before, but chose to commit himself to the Union Workhouse rather than be arrested for debt. Phiz's realization of Old Nandy conveys well his perpetually cheerful nature, as opposed to William Dorrit's puffery and discontent:

Mrs. Plornish's father, — a poor little reedy piping old gentleman, like a worn-out bird; who had been in what he called the music- binding business, and met with great misfortunes, and who had seldom been able to make his way, or to see it or to pay it, or to do anything at all with it but find it no thoroughfare, — had retired of his own accord to the Workhouse which was appointed by law to be the Good Samaritan of his district (without the twopence, which was bad political economy), on the settlement of that execution which had carried Mr Plornish to the Marshalsea College. Previous to his son-in-law's difficulties coming to that head, Old Nandy (he was always so called in his legal Retreat, but he was Old Mr Nandy among the Bleeding Hearts) had sat in a corner of the Plornish fireside, and taken his bite and sup out of the Plornish cupboard. He still hoped to resume that domestic position when Fortune should smile upon his son-in-law; in the meantime, while she preserved an immovable countenance, he was, and resolved to remain, one of these little old men in a grove of little old men with a community of flavour.

But no poverty in him, and no coat on him that never was the mode, and no Old Men's Ward for his dwelling-place, could quench his daughter's admiration. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 31, "Spirit".

The other figures in the group study (organized in a three-two-one configuration that draws the eye of the viewer towards the little man in the window seat, right) should by now be familiar enough to the reader as the story reaches its mid-point: in profile, Fanny Dorrit, proud and stiff-backed, drinking tea from a small china cup and saucer (left); the mentally-challenged but good natured Maggy, holding aloft a toasting fork; the serious-minded, mutton-chopped young bachelor Arthur Clennam (centre, back to the viewer); to the right, Little Dorrit, dutifully attending to her father's needs; The magisterial Father of the Marshalsea, patronizing as ever; and in the cramped seat before the barred window, the balding, wizened little Mr. Nandy, with a newspaper spread as his tea-table. The Marshalsea chamber as furnished by the Dorrits has the middle-class touches of a regular parlor, including a high-backed, padded chair for the Pater Familias, a linen tablecloth, a carpet, a sideboard (rear), and several paintings. Thus does Phiz, probably at Dickens's direction, render a minor incident and a secondary character memorable while reinforcing the reader's notions about the principals.

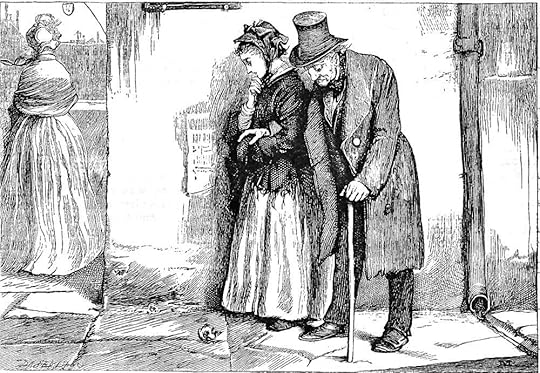

They were within five minutes of their destination.

Chapter 31, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

They walked at a slow pace, and Little Dorrit took him by the Iron Bridge and sat him down there for a rest, and they looked over at the water and talked about the shipping, and the old man mentioned what he would do if he had a ship full of gold coming home to him (his plan was to take a noble lodging for the Plornishes and himself at a Tea Gardens, and live there all the rest of their lives, attended on by the waiter), and it was a special birthday of the old man. They were within five minutes of their destination, when, at the corner of her own street, they came upon Fanny in her new bonnet bound for the same port.

"Why, good gracious me, Amy!" cried that young lady starting. "You never mean it!"

"Mean what, Fanny dear?"

"Well! I could have believed a great deal of you," returned the young lady with burning indignation, "but I don't think even I could have believed this, of even you!"

"Fanny!" cried Little Dorrit, wounded and astonished.

"Oh! Don't Fanny me, you mean little thing, don't! The idea of coming along the open streets, in the broad light of day, with a Pauper!" (firing off the last word as if it were a ball from an air-gun).

"O Fanny!"

I tell you not to Fanny me, for I'll not submit to it! I never knew such a thing. The way in which you are resolved and determined to disgrace us, on all occasions, is really infamous. You bad little thing!"

Does it disgrace anybody," said Little Dorrit, very gently, to take care of this poor old man?"

"Yes, miss," returned her sister, "and you ought to know it does. And you do know it does, and you do it because you know it does. The principal pleasure of your life is to remind your family of their misfortunes. And the next great pleasure of your existence is to keep low company. But, however, if you have no sense of decency, I have. You'll please to allow me to go on the other side of the way, unmolested."

With this, she bounced across to the opposite pavement. The old disgrace, who had been deferentially bowing a pace or two off (for Little Dorrit had let his arm go in her wonder, when Fanny began), and who had been hustled and cursed by impatient passengers for stopping the way, rejoined his companion, rather giddy, and said, "I hope nothing's wrong with your honoured father, Miss? I hope there's nothing the matter in the honoured family?"

"No, no," returned Little Dorrit. "No, thank you. Give me your arm again, Mr. Nandy. We shall soon be there now." — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 31, "Spirit," p. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 31.

Commentary:

The half-page illustration occurs within the thirtieth chapter of Book One, "Poverty," with the running head "Some Secrets in All Families" — here, somewhat ironic in that the Plornishes do not attempt to disguise the fact that Nandy is a resident of the Union Workhouse. This is a somewhat lackluster response to the more lively group study in the 1856-57 serial, The Pensioner Entertainment, in which the Father of the Marshalsea outrageously (and hilariously) patronizes Old Nandy as a decrepit "Pauper." Mahoney does not duplicate the work of Dickens's original illustrator, "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne), but rather complements Phiz's realization of the subsequent scene of pointless snobbery and foolish class-consciousness at the Marshalsea rooms of William Dorrit. The Household Edition illustration, proleptically situated four pages ahead of the passage realized, shows a downcast Amy, genuinely sorry to think that she has somehow offended her younger sister in her new bonnet (upper left, back to the reader and to Amy), round the corner rather than across the street, as in the text. Ever the model of Victorian middle-class femininity — charity, kindness, self-sacrifice, and dutifulness, Amy Dorrit supports the doddering Old Nandy, the aged music-binder who, like William Dorrit, fell into debt years before, but chose to commit himself to the Union Workhouse rather than be arrested for debt. Whereas Phiz's realization of Old Nandy conveys well his perpetually cheerful nature, as opposed to William Dorrit's puffery and discontent, Mahoney's shows him as well-dressed but pathetically frail:

Mrs. Plornish's father, — a poor little reedy piping old gentleman, like a worn-out bird; who had been in what he called the music- binding business, and met with great misfortunes, and who had seldom been able to make his way, or to see it or to pay it, or to do anything at all with it but find it no thoroughfare, — had retired of his own accord to the Workhouse which was appointed by law to be the Good Samaritan of his district (without the twopence, which was bad political economy), on the settlement of that execution which had carried Mr Plornish to the Marshalsea College. Previous to his son-in-law's difficulties coming to that head, Old Nandy (he was always so called in his legal Retreat, but he was Old Mr Nandy among the Bleeding Hearts) had sat in a corner of the Plornish fireside, and taken his bite and sup out of the Plornish cupboard. He still hoped to resume that domestic position when Fortune should smile upon his son-in-law; in the meantime, while she preserved an immovable countenance, he was, and resolved to remain, one of these little old men in a grove of little old men with a community of flavour.

But no poverty in him, and no coat on him that never was the mode, and no Old Men's Ward for his dwelling-place, could quench his daughter's admiration. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 31, "Spirit".

Little Dorrit disgraces her family

Chapter 31, Book 1

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

They walked at a slow pace, and Little Dorrit took him by the Iron Bridge and sat him down there for a rest, and they looked over at the water and talked about the shipping, and the old man mentioned what he would do if he had a ship full of gold coming home to him (his plan was to take a noble lodging for the Plornishes and himself at a Tea Gardens, and live there all the rest of their lives, attended on by the waiter), and it was a special birthday of the old man. They were within five minutes of their destination, when, at the corner of her own street, they came upon Fanny in her new bonnet bound for the same port.

"Why, good gracious me, Amy!" cried that young lady starting. "You never mean it!"

"Mean what, Fanny dear?"

"Well! I could have believed a great deal of you," returned the young lady with burning indignation, "but I don't think even I could have believed this, of even you!"

"Fanny!" cried Little Dorrit, wounded and astonished.

"Oh! Don't Fanny me, you mean little thing, don't! The idea of coming along the open streets, in the broad light of day, with a Pauper!" (firing off the last word as if it were a ball from an air-gun).

"O Fanny!

I tell you not to Fanny me, for I'll not submit to it! I never knew such a thing. The way in which you are resolved and determined to disgrace us, on all occasions, is really infamous. You bad little thing!"

Does it disgrace anybody," said Little Dorrit, very gently, to take care of this poor old man?"

Commentary:

Little Dorrit disgraces her Family is Harry Furniss's fin-de-siécle re-interpretation of the James Mahoney composite Household Edition woodblock engraving in which the pretentious, class-conscious Fanny Dorrit accuses her sister, Amy, of having "lowered" herself by having been seen in public with a mere "Pauper," Old Nandy, Mrs. Plornish's aged father. The lithograph occurs facing page 416, but the passage illustrated occurs fully thirty-four pages earlier, compelling the reader to return from Chapter 34 ("A Shoal of Barnacles") to the scene with Mrs. Plornish's father — "a poor little reedy piping old gentleman, like a worn-out bird", a failed music-binder who has voluntarily retreated to the Union Workhouse.

Furniss captures the hypocrisy of the younger Dorrit sister, whose character is reflected in the indignant glance of a tradesman immediately behind Old Nandy (centre). Furniss reinterprets in a highly animated fashion not one of the original Phiz serial steel-engravings, but James Mahoney's Household Edition composite woodblock engraving They were within five minutes of their destination. Furniss's focusing on the contrasting behaviors of the siblings effectively exemplifies the irony of the chapter title.

Although the decade of the story's action is usually given as the 1830s, since the scene in Marseilles with which the story begins is set "thirty years ago" (i. e., 1826), Furniss imbeds a sign advertising Jenny Lind's forthcoming concert at Exeter Hall in London, implying that this scene in Little Dorrit occurs when the Swedish opera-singer Jenny Lind made her long-delayed English debut in May of 1847, before the cream of Victorian society, and went on to sing before Queen Victoria herself. Everywhere Miss Lind went, crowds of people pressed inward, hoping to catch a glimpse of the famous 27-year-old operatic vocalist. The crowds in the London street in Furniss's illustration convey a sense of the vital energy of the world beyond the gates and walls of the Marshalsea. In the foreground, the snobbish Fanny hypocritically chastises her sister for being seen in the company of an occupant of a workhouse when her own father has long been incarcerated for debt in the Marshalsea.

The other imbedded clue as to the date of the scene is the presence of a London "Peeler" or "Bobby" in the background, just behind Little Dorrit. Sir Robert Peel's founding of the metropolitan police force in September 1829 is consistent (or nearly so) with Dickens's dating of the novel's action. Of the other artistic interpretations of Old Nandy, surely those of Phiz and Sol Eytinge, Junior, offer a more accurate assessment of the cheerful senior than Furniss's portrait of a sour curmudgeon.

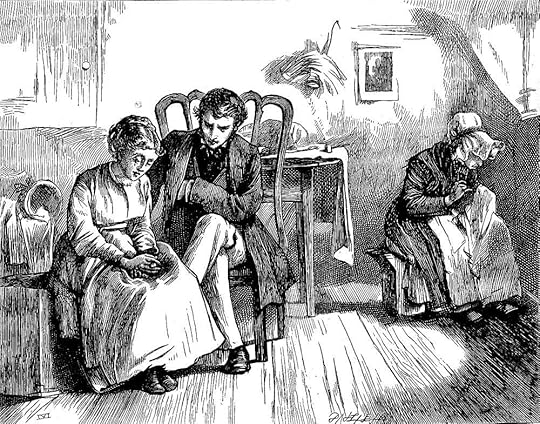

Her hands were then nervously clasping together.

Chapter 32, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

As Arthur Clennam moved to sit down by the side of Little Dorrit, she trembled so that she had much ado to hold her needle. Clennam gently put his hand upon her work, and said, "Dear Little Dorrit, let me lay it down."

She yielded it to him, and he put it aside. Her hands were then nervously clasping together, but he took one of them.

"How seldom I have seen you lately, Little Dorrit!"

"I have been busy, sir."

"But I heard only to-day," said Clennam, "by mere accident, of your having been with those good people close by me. Why not come to me, then?"

"I — I don't know. Or rather, I thought you might be busy too. You generally are now, are you not?"

He saw her trembling little form and her downcast face, and the eyes that drooped the moment they were raised to his — he saw them almost with as much concern as tenderness.

Commentary:

This study emphasizes Amy's modest, self-sacrificing nature as she pretends not to be interested romantically in the man who is endeavouring to effect her father's release from the Marshalsea. The setting was one which Phiz had depicted several times, the Dorrit family garret in the debtors' prison, and Little Dorrit is once again is engaged in that respectable middle-class feminine past-time, needle-work. Mahoney subtly suggests Clennam's superior social rank by placing him on a higher level than Amy's, in a large chair. In this, the last of what were originally the three chapters of the ninth serial number, Amy is embarrassed that her father and her brother, Tip, have insulted Arthur. He assures her that he understands her father's motivations, and does not regard his self-centred remarks and Tip's "showing the proper Spirit" as insults. In this illustration, the "spirited" brother and sister having left and Mr. Dorrit off to the Snuggery, "So, at last, Clennam's purpose in remaining was attained, and he could speak to Little Dorrit with nobody by. Maggy counted as nobody, and she was by", Amy begins to weep as Arthur asks her to rely on and confide in him.

Although Mahoney's illustration occurs towards the conclusion of Chapter 31, it must be read proleptically as the passage illustrated occurs early in the next chapter. The illustration alerts the reader to the fact that Clennam and Amy are about to have a private interview — although the presence of Maggy in the background as a sort of chaperone renders the scene with its intimate dialogue socially acceptable. Amy has rejected John Chivery's romantic overtures, and Arthur has just parted with Minnie (Pet Meagles), who has decided to accept Henry Gowan's proposal. Already, Arthur is beginning to appreciate Amy's sensitivity and seriousness, in contrast to the flighty females of his youth, Flora and Pet, who of course can afford to dwell on frivolous fashions and conspicuous consumption, unlike the poor but earnest Little Dorrit, here depicted as Dickens describes her: "He saw the devoted little creature with her worn shoes, in her common dress, in her gaol-home; a slender child in body, a strong heroine in soul; and the light of her domestic story made all else dark to him".

Kim wrote: "

Her hands were then nervously clasping together.

Chapter 32, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

As Arthur Clennam moved to sit down by the side of Little Dorrit, she trembled so that she ..."

Kim

As always, thanks for the illustrations. I liked the commentary regarding Mahoney’s illustration of Arthur and Amy. It offers a perfect domestic scene. This private interview reveals the depth of emotions of both Amy and Arthur.

What I find fascinating is the way Amy has been portrayed. Amy does not look little. We know she is in her early twenties and here she is portrayed as a woman, not a diminutive child.

The pose of Amy and Maggy are strikingly similar. They are both at their work. The difference is that Maggy is wearing the cap of a lower-class domestic. Amy, in contrast, is hatless. She is portrayed with her hair up and Arthur’s gaze is intent on her. Arthur’s right arm is placed behind Amy’s back to suggest both his willingness to support her and to hint that there is a growing intimacy between them.

If we think back to Browne’s illustration of Arthur, Maggy and Amy we will see the positions of the three characters almost in the exact same positions and facing the same direction. The difference is that in the Browne illustration Maggy is centre right and Amy is gazing out the window. Here, Mahoney has placed Maggy by the window for better light to work with and Arthur is now much closer to Amy.

I think the real “tell” is that in Browne’s illustration Amy’s outside clothes were on the bed. Amy was looking out the window as she recounted the story of the entrapped Princess. In this illustration, Mahoney does away with Amy’s outside clothes. Here, Amy's Prince has arrived. She no longer has to linger by a window in her prison room in a tower.

Her hands were then nervously clasping together.

Chapter 32, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

As Arthur Clennam moved to sit down by the side of Little Dorrit, she trembled so that she ..."

Kim

As always, thanks for the illustrations. I liked the commentary regarding Mahoney’s illustration of Arthur and Amy. It offers a perfect domestic scene. This private interview reveals the depth of emotions of both Amy and Arthur.

What I find fascinating is the way Amy has been portrayed. Amy does not look little. We know she is in her early twenties and here she is portrayed as a woman, not a diminutive child.

The pose of Amy and Maggy are strikingly similar. They are both at their work. The difference is that Maggy is wearing the cap of a lower-class domestic. Amy, in contrast, is hatless. She is portrayed with her hair up and Arthur’s gaze is intent on her. Arthur’s right arm is placed behind Amy’s back to suggest both his willingness to support her and to hint that there is a growing intimacy between them.

If we think back to Browne’s illustration of Arthur, Maggy and Amy we will see the positions of the three characters almost in the exact same positions and facing the same direction. The difference is that in the Browne illustration Maggy is centre right and Amy is gazing out the window. Here, Mahoney has placed Maggy by the window for better light to work with and Arthur is now much closer to Amy.

I think the real “tell” is that in Browne’s illustration Amy’s outside clothes were on the bed. Amy was looking out the window as she recounted the story of the entrapped Princess. In this illustration, Mahoney does away with Amy’s outside clothes. Here, Amy's Prince has arrived. She no longer has to linger by a window in her prison room in a tower.

Kim wrote: "Tristram, I know we read this book before, I don't know how many of the group were with us then, but maybe you can tell me, did I hate the Dorrits as much as I do now back then? I can't stand any o..."

Kim, I can't remember whether you hated the Dorrits the last time we read this, but as you are a very reasonable person you probably did. By the way, one of us has always found fault with Little Nell. Was it you, or me?

Kim, I can't remember whether you hated the Dorrits the last time we read this, but as you are a very reasonable person you probably did. By the way, one of us has always found fault with Little Nell. Was it you, or me?

Mary Lou wrote: "PS And what is Pancks interest in all of this? What suspicions did he have that led him to put so much time and energy into this project?"

Mary Lou wrote: "PS And what is Pancks interest in all of this? What suspicions did he have that led him to put so much time and energy into this project?"This is the thing that is killing me to know! I didn't like Panks at first, to up front with his business like ways, and that upfront-ness has not led me to believe that he is simply a good Samaritan.

At this point in the novel I'm just looking for a reason to care for a single character in this book. The Plornishes seem to be the only worthwhile people...perhaps Flora is redeemable, but honestly her hiring of Amy seems more likely an attempt at self serving than anything else. I'm quite sure that if I made a list of all the characters I could write at least a sentence on each why they are distasteful. I do hope that was Mr.Dickens intention.

At this point in the novel I'm just looking for a reason to care for a single character in this book. The Plornishes seem to be the only worthwhile people...perhaps Flora is redeemable, but honestly her hiring of Amy seems more likely an attempt at self serving than anything else. I'm quite sure that if I made a list of all the characters I could write at least a sentence on each why they are distasteful. I do hope that was Mr.Dickens intention.

Avery wrote: "At this point in the novel I'm just looking for a reason to care for a single character in this book. The Plornishes seem to be the only worthwhile people...perhaps Flora is redeemable, but honestl..."

Avery wrote: "At this point in the novel I'm just looking for a reason to care for a single character in this book. The Plornishes seem to be the only worthwhile people...perhaps Flora is redeemable, but honestl..."Oh, Avery--I have a list of worthwhile people in this book! Here:

1. Doyce

Julie wrote: "Avery wrote: "At this point in the novel I'm just looking for a reason to care for a single character in this book. The Plornishes seem to be the only worthwhile people...perhaps Flora is redeemabl..."

Julie wrote: "Avery wrote: "At this point in the novel I'm just looking for a reason to care for a single character in this book. The Plornishes seem to be the only worthwhile people...perhaps Flora is redeemabl..."Oh, wait, also I really really like the injured Italian guy who skipped town on the villain. He seems like a sweetheart with his wits about him.

And I do like Flora even if, as you point out, she's a bit self-serving in her vanity. It doesn't hurt anyone and she is great fun. And also there are a number of fascinating people I like to dislike, especially Mrs. Clennam.

Jantine wrote: "I remember reading this book for the first time (aaaaaaages ago), and all through the first book I was just waiting for Arthur to swoop in, marry Amy, and rescue her from her horrible family. I did..."

Jantine wrote: "I remember reading this book for the first time (aaaaaaages ago), and all through the first book I was just waiting for Arthur to swoop in, marry Amy, and rescue her from her horrible family. I did..."It seems horrid that our apparent hero is quite creepy, while I genuinely think that he is trying not to be creepy. He was trying to find out whether Ms. Amy returned, what's his name, the tobacconists' son's, affections. I want to justify Mr. Clemnams' actions through a desperation to make Ms. Amy happy, but really, its so not his business and just horridly invasive!

Mary Lou wrote: "Likable people do not make for interesting reading, unless or until they find themselves in peril. I don't wish trouble on nice people in real life, but I relish it in fiction. ;-)"

Mary Lou wrote: "Likable people do not make for interesting reading, unless or until they find themselves in peril. I don't wish trouble on nice people in real life, but I relish it in fiction. ;-)"While I can quite agree with this sentiment, I wish I had at least one of the apparent main cast to sympathize with of more focus on a "love to hate them" villain. As it is, most of the characters just annoy me. I'm reading for the prose now, rather than investment in the plot. I wonder if this is a disconnect between my modern sensibilities and the original intended audience? I have the feeling that I'm supposed to care about Ms. Amy and Mr. Clemnam. Are we not invested in this star-crossed lover scenario due to the Electra-esque nature of it not matching our modern standards of romantic?

Avery wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Likable people do not make for interesting reading, unless or until they find themselves in peril. I don't wish trouble on nice people in real life, but I relish it in fiction. ;-)..."

Hi Avery

Your point about the disconnect between our “modern sensibilities and the original intended audience” is one of my biggest stumbling points as well. I also often struggle with putting into my context and experience the living arrangements, social surroundings, and experiences of our Victorian predecessors.

Dickens was well aware of his intended audience and I believe gave them what they wanted while, at the same time, nudging into his narratives his own personal opinions and beliefs. I often find his minor characters to be much more enjoyable than the principle ones. Arthur is hard to stomach at times. Doyce and Pancks are great.

I fully agree that Dickens’s prose is wonderful.

Hi Avery

Your point about the disconnect between our “modern sensibilities and the original intended audience” is one of my biggest stumbling points as well. I also often struggle with putting into my context and experience the living arrangements, social surroundings, and experiences of our Victorian predecessors.

Dickens was well aware of his intended audience and I believe gave them what they wanted while, at the same time, nudging into his narratives his own personal opinions and beliefs. I often find his minor characters to be much more enjoyable than the principle ones. Arthur is hard to stomach at times. Doyce and Pancks are great.

I fully agree that Dickens’s prose is wonderful.

Julie wrote: "Julie wrote: "Avery wrote: "At this point in the novel I'm just looking for a reason to care for a single character in this book. The Plornishes seem to be the only worthwhile people...perhaps Flor..."

Julie wrote: "Julie wrote: "Avery wrote: "At this point in the novel I'm just looking for a reason to care for a single character in this book. The Plornishes seem to be the only worthwhile people...perhaps Flor..."Yes, thank you for reminding me of Jean-Baptiste! A lovable and clever fellow. Although the ability to forget characters in this book is amazing...the cast is so big!!!

Julie wrote: "Avery wrote: "At this point in the novel I'm just looking for a reason to care for a single character in this book. The Plornishes seem to be the only worthwhile people...perhaps Flora is redeemabl..."