The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit, Book 2, Chp. 05-07

Chapter 6 is titled "Something Right Somewhere" and so I am looking forward to pleasant things happening in the chapter but of course I'm wrong. We start with Henry Gowan "loitering moodily about on neutral ground". Henry is in the habit "of seeking some sort of recompense in the discontented boast of being disappointed." Poor Henry, he declares that all art is "trash" and that he turns out nothing else. He makes it a practice to show he is poor and by that to show that he should be rich. He would publicly discuss the Barnacles so that everyone would be aware of his connection to them and makes it known that he had married against the wishes of his family and has married beneath his station.

"Monsieur Blandois of Paris" has accompanied them to Venice and spends much of his time with Mr. Gowan. Mr. Gowan didn't know at first whether he liked or disliked Blandois when they met him in Geneva, and couldn't decide whether to "kick him or encourage him." Minipet expressed a definite dislike of the man, and so Henry decided to befriend him. Figure that one out. He wanted to assert his independence after her father paid his debts, so he becomes friends with the guy his wife doesn't like. That makes no sense to me. He doesn't care for him and we're told if he had any reason to throw him out the window he would, but for now he is his almost constant companion.

When Amy makes her visit to Mrs. Gowan unfortunately Fanny insists on coming along. I mean unfortunately for Amy and Minipet that is. Fanny does the initial talking, mentioning how she heard that the Gowans knew the Merdles. Minipet says they are Henry’s friends whom she has not yet met. Fanny feels superior in having met Mrs. Merdle saying that she thinks Minipet will like Mrs. Merdle and that the Dorrits and Merdles are quite good friends. Minipet takes Amy and Fanny into Henry's studio where they find Henry at work painting a portrait and Blandois also present being the model for the painting. Blandois seems very uneasy when Henry describes the painting to the ladies:

'Let the ladies at least see the original of the daub, that they may know what it's meant for. There he stands, you see. A bravo waiting for his prey, a distinguished noble waiting to save his country, the common enemy waiting to do somebody a bad turn, an angelic messenger waiting to do somebody a good turn—whatever you think he looks most like!'

'Say, Professore Mio, a poor gentleman waiting to do homage to elegance and beauty,' remarked Blandois.

'Or say, Cattivo Soggetto Mio,' returned Gowan, touching the painted face with his brush in the part where the real face had moved, 'a murderer after the fact. Show that white hand of yours, Blandois. Put it outside the cloak. Keep it still.'

Blandois' hand was unsteady; but he laughed, and that would naturally shake it.

'He was formerly in some scuffle with another murderer, or with a victim, you observe,' said Gowan, putting in the markings of the hand with a quick, impatient, unskilful touch, 'and these are the tokens of it. Outside the cloak, man!—Corpo di San Marco, what are you thinking of?'

Blandois of Paris shook with a laugh again, so that his hand shook more; now he raised it to twist his moustache, which had a damp appearance; and now he stood in the required position, with a little new swagger."

I suppose he may be afraid that someday someone will realize who he really is. At this point Henry is very, very lucky I wasn't in the room. When his very sensible dog begins to growl at Blandois Henry tells Blandois to leave the room. However, once Blandois is out of the room and the dog is calm Henry proceeds to "fell him with a blow to the head, and kick him severely with the heel of his boot, so that his mouth was presently bloody". As I read this there is a black cocker spaniel curled up on my lap and Henry Gowan's life is in danger.

I'm skipping the rest of the dog torture to say that shortly after this the ladies take their departure. Fanny points out Mr. Sparkler, who is following them in another gondola. Amy wonders why he hasn’t called yet and Fanny thinks he is working up the courage and she wouldn't be surprised to see him that day. They do find Sparkler at the door and while trying to greet the ladies standing up in his gondola, falls down. Fanny inquires after him, pretending she doesn’t know him. He reminds her they met in Martigny, and says he has come to call on Edward and their father. Mr. Dorrit invites Sparkler to dinner and to the opera later. Mr. Dorrit says he wishes to hire Mr. Gowan and to do portraits of the family. This is how their evening at the opera ends:

Little Dorrit was in front with her brother and Mrs General (Mr Dorrit had remained at home), but on the brink of the quay they all came together. She started again to find Blandois close to her, handing Fanny into the boat.

'Gowan has had a loss,' he said, 'since he was made happy to-day by a visit from fair ladies.'

'A loss?' repeated Fanny, relinquished by the bereaved Sparkler, and taking her seat.

'A loss,' said Blandois. 'His dog Lion.'

Little Dorrit's hand was in his, as he spoke.

'He is dead,' said Blandois.

'Dead?' echoed Little Dorrit. 'That noble dog?'

'Faith, dear ladies!' said Blandois, smiling and shrugging his shoulders, 'somebody has poisoned that noble dog. He is as dead as the Doges!'

I hate these people.

"Monsieur Blandois of Paris" has accompanied them to Venice and spends much of his time with Mr. Gowan. Mr. Gowan didn't know at first whether he liked or disliked Blandois when they met him in Geneva, and couldn't decide whether to "kick him or encourage him." Minipet expressed a definite dislike of the man, and so Henry decided to befriend him. Figure that one out. He wanted to assert his independence after her father paid his debts, so he becomes friends with the guy his wife doesn't like. That makes no sense to me. He doesn't care for him and we're told if he had any reason to throw him out the window he would, but for now he is his almost constant companion.

When Amy makes her visit to Mrs. Gowan unfortunately Fanny insists on coming along. I mean unfortunately for Amy and Minipet that is. Fanny does the initial talking, mentioning how she heard that the Gowans knew the Merdles. Minipet says they are Henry’s friends whom she has not yet met. Fanny feels superior in having met Mrs. Merdle saying that she thinks Minipet will like Mrs. Merdle and that the Dorrits and Merdles are quite good friends. Minipet takes Amy and Fanny into Henry's studio where they find Henry at work painting a portrait and Blandois also present being the model for the painting. Blandois seems very uneasy when Henry describes the painting to the ladies:

'Let the ladies at least see the original of the daub, that they may know what it's meant for. There he stands, you see. A bravo waiting for his prey, a distinguished noble waiting to save his country, the common enemy waiting to do somebody a bad turn, an angelic messenger waiting to do somebody a good turn—whatever you think he looks most like!'

'Say, Professore Mio, a poor gentleman waiting to do homage to elegance and beauty,' remarked Blandois.

'Or say, Cattivo Soggetto Mio,' returned Gowan, touching the painted face with his brush in the part where the real face had moved, 'a murderer after the fact. Show that white hand of yours, Blandois. Put it outside the cloak. Keep it still.'

Blandois' hand was unsteady; but he laughed, and that would naturally shake it.

'He was formerly in some scuffle with another murderer, or with a victim, you observe,' said Gowan, putting in the markings of the hand with a quick, impatient, unskilful touch, 'and these are the tokens of it. Outside the cloak, man!—Corpo di San Marco, what are you thinking of?'

Blandois of Paris shook with a laugh again, so that his hand shook more; now he raised it to twist his moustache, which had a damp appearance; and now he stood in the required position, with a little new swagger."

I suppose he may be afraid that someday someone will realize who he really is. At this point Henry is very, very lucky I wasn't in the room. When his very sensible dog begins to growl at Blandois Henry tells Blandois to leave the room. However, once Blandois is out of the room and the dog is calm Henry proceeds to "fell him with a blow to the head, and kick him severely with the heel of his boot, so that his mouth was presently bloody". As I read this there is a black cocker spaniel curled up on my lap and Henry Gowan's life is in danger.

I'm skipping the rest of the dog torture to say that shortly after this the ladies take their departure. Fanny points out Mr. Sparkler, who is following them in another gondola. Amy wonders why he hasn’t called yet and Fanny thinks he is working up the courage and she wouldn't be surprised to see him that day. They do find Sparkler at the door and while trying to greet the ladies standing up in his gondola, falls down. Fanny inquires after him, pretending she doesn’t know him. He reminds her they met in Martigny, and says he has come to call on Edward and their father. Mr. Dorrit invites Sparkler to dinner and to the opera later. Mr. Dorrit says he wishes to hire Mr. Gowan and to do portraits of the family. This is how their evening at the opera ends:

Little Dorrit was in front with her brother and Mrs General (Mr Dorrit had remained at home), but on the brink of the quay they all came together. She started again to find Blandois close to her, handing Fanny into the boat.

'Gowan has had a loss,' he said, 'since he was made happy to-day by a visit from fair ladies.'

'A loss?' repeated Fanny, relinquished by the bereaved Sparkler, and taking her seat.

'A loss,' said Blandois. 'His dog Lion.'

Little Dorrit's hand was in his, as he spoke.

'He is dead,' said Blandois.

'Dead?' echoed Little Dorrit. 'That noble dog?'

'Faith, dear ladies!' said Blandois, smiling and shrugging his shoulders, 'somebody has poisoned that noble dog. He is as dead as the Doges!'

I hate these people.

The last chapter of this installment is Chapter 7 titled "Mostly, Prunes and Prism" and we begin with Mrs. General trying to make Little Dorrit's lips look pretty among other things I suppose but not making much progress. Try as she might however, and we're told she tries harder than ever to be shaped by Mrs. General Amy doesn't make much progress. Her one comfort during all this is that Fanny is finally being nice to her. Fanny tells Amy one night that she thinks their father is too polite to Mrs. General. She believes Mrs. General has designs on their father and hopes to ensnare him, and their father admires her so much, thinking of her as a wonder, and an acquisition to the family, that he admires her enough to become infatuated, . Fanny says she couldn’t bear such a union and would even marry Sparkler to escape it. Amy is alarmed and can’t believe her sister is serious, but Fanny says she is—especially if she could treat Mrs. Merdle in her own style. Fanny is very cruel to Mr. Sparkler who is very devoted to her:

"Sometimes she would prefer him to such distinction of notice, that he would chuckle aloud with joy; next day, or next hour, she would overlook him so completely, and drop him into such an abyss of obscurity, that he would groan under a weak pretence of coughing."

What he sees in her I don't know, perhaps she is beautiful but I would think that wouldn't make up for her personality. However, devoted he is and Edward finds Sparkler as his constant companion rather tiresome and often has to sneak away. I would have to sneak away too, but from everyone else in the book, not just Sparkler. Sparkler often follows Fanny’s gondola:

"he was so constantly being paddled up and down before the principal windows, that he might have been supposed to have made a wager for a large stake to be paddled a thousand miles in a thousand hours; though whenever the gondola of his mistress left the gate, the gondola of Mr Sparkler shot out from some watery ambush and gave chase, as if she were a fair smuggler and he a custom-house officer."

Blandois calls upon Mr. Dorrit, who requests him to tell Mr. Gowan that he wants him to do his portrait. On hearing this Henry becomes angry "for he resented patronage almost as much as he resented the want of it", thinking it over though, he changes his mind and goes to see Mr. Dorrit saying he has to take jobs where he can get them. Henry admits to Mr. Dorrit that he is new to the trade and a bad painter saying he had not been brought up to it and it was too late to learn, however, he is no worse than most. Mr. Dorrit still wants him to do it, and Henry suggests they do the portrait in Rome, where they all will be leaving for shortly.

Little Dorrit and Mrs. Gowan become friends and both women have an aversion to Blandois. When Mrs. Gowan bids goodbye to Amy before she leaves Venice, Blandois is there but Mrs. Gowan does manage to tell Amy that she is sure he killed the dog.

Now their time in Venice is over and they leave for Rome where Little Dorrit thinks Mrs. General gets the upper hand for when walking about St. Peter's and the Vatican nobody said what anything was, but everybody said what the Mrs General, Mr Eustace, or somebody else said it was. Now because of that line I had to go look up who Mr. Eustace was:

"John Chetwode Eustace was an Anglo-Irish Catholic priest and antiquary. In 1802 he travelled through Italy with three pupils. During these travels he wrote a journal which subsequently became celebrated in his "A Classical Tour Through Italy". In 1813 the publication of his "Classical Tour" obtained for him sudden celebrity, and he became a prominent figure in literary society. In 1815 he travelled again to Italy to collect fresh materials, but he was seized with malaria at Naples and died there."

Now that they've arrived in Rome Mrs. Merdle pays them a visit and talks about how pleased she is to resume an acquaintance that began at Martigny. Mr. Dorrit asks whether Mr. Merdle will be coming to Rome but Mrs. Merdle says her husband never travels now. This is how the chapter ends:

"Little Dorrit, still habitually thoughtful and solitary though no longer alone, at first supposed this to be mere Prunes and Prism. But as her father when they had been to a brilliant reception at Mrs Merdle's, harped at their own family breakfast-table on his wish to know Mr Merdle, with the contingent view of benefiting by the advice of that wonderful man in the disposal of his fortune, she began to think it had a real meaning, and to entertain a curiosity on her own part to see the shining light of the time."

"Sometimes she would prefer him to such distinction of notice, that he would chuckle aloud with joy; next day, or next hour, she would overlook him so completely, and drop him into such an abyss of obscurity, that he would groan under a weak pretence of coughing."

What he sees in her I don't know, perhaps she is beautiful but I would think that wouldn't make up for her personality. However, devoted he is and Edward finds Sparkler as his constant companion rather tiresome and often has to sneak away. I would have to sneak away too, but from everyone else in the book, not just Sparkler. Sparkler often follows Fanny’s gondola:

"he was so constantly being paddled up and down before the principal windows, that he might have been supposed to have made a wager for a large stake to be paddled a thousand miles in a thousand hours; though whenever the gondola of his mistress left the gate, the gondola of Mr Sparkler shot out from some watery ambush and gave chase, as if she were a fair smuggler and he a custom-house officer."

Blandois calls upon Mr. Dorrit, who requests him to tell Mr. Gowan that he wants him to do his portrait. On hearing this Henry becomes angry "for he resented patronage almost as much as he resented the want of it", thinking it over though, he changes his mind and goes to see Mr. Dorrit saying he has to take jobs where he can get them. Henry admits to Mr. Dorrit that he is new to the trade and a bad painter saying he had not been brought up to it and it was too late to learn, however, he is no worse than most. Mr. Dorrit still wants him to do it, and Henry suggests they do the portrait in Rome, where they all will be leaving for shortly.

Little Dorrit and Mrs. Gowan become friends and both women have an aversion to Blandois. When Mrs. Gowan bids goodbye to Amy before she leaves Venice, Blandois is there but Mrs. Gowan does manage to tell Amy that she is sure he killed the dog.

Now their time in Venice is over and they leave for Rome where Little Dorrit thinks Mrs. General gets the upper hand for when walking about St. Peter's and the Vatican nobody said what anything was, but everybody said what the Mrs General, Mr Eustace, or somebody else said it was. Now because of that line I had to go look up who Mr. Eustace was:

"John Chetwode Eustace was an Anglo-Irish Catholic priest and antiquary. In 1802 he travelled through Italy with three pupils. During these travels he wrote a journal which subsequently became celebrated in his "A Classical Tour Through Italy". In 1813 the publication of his "Classical Tour" obtained for him sudden celebrity, and he became a prominent figure in literary society. In 1815 he travelled again to Italy to collect fresh materials, but he was seized with malaria at Naples and died there."

Now that they've arrived in Rome Mrs. Merdle pays them a visit and talks about how pleased she is to resume an acquaintance that began at Martigny. Mr. Dorrit asks whether Mr. Merdle will be coming to Rome but Mrs. Merdle says her husband never travels now. This is how the chapter ends:

"Little Dorrit, still habitually thoughtful and solitary though no longer alone, at first supposed this to be mere Prunes and Prism. But as her father when they had been to a brilliant reception at Mrs Merdle's, harped at their own family breakfast-table on his wish to know Mr Merdle, with the contingent view of benefiting by the advice of that wonderful man in the disposal of his fortune, she began to think it had a real meaning, and to entertain a curiosity on her own part to see the shining light of the time."

Kim wrote: "Little Dorrit and Mrs. Gowan become friends and both women have an aversion to Blandois. When Mrs. Gowan bids goodbye to Amy before she leaves Venice, Blandois is there but Mrs. Gowan does manage to tell Amy that she is sure he killed the dog."

Kim wrote: "Little Dorrit and Mrs. Gowan become friends and both women have an aversion to Blandois. When Mrs. Gowan bids goodbye to Amy before she leaves Venice, Blandois is there but Mrs. Gowan does manage to tell Amy that she is sure he killed the dog."The scenes where Amy and Minipet are together and desperately trying to talk to each other but can't because there are other people around are so odd. I can't quite make out whether it's the usual thing where you want to have a private conversation with someone but can't manage to get them alone, or if it's a reflection of the two women's virtual imprisonment by their families that they can't talk to each other, especially about anything unpleasant--or (probably) a combination of both.

But Mr. Dorrit manages to get an audience with Mrs. General, so I expect it has more to do with Minipet and Amy being more supervised and less at liberty. Minipet especially. I'm not sure she's going to make it out of this book alive, given how her husband treats his dog. We've already seen dog abuse in another Dickens book and it didn't end well.

Did everyone like this passage as much as I did? It's not remotely subtle but it's well put.

Did everyone like this passage as much as I did? It's not remotely subtle but it's well put. It appeared on the whole, to Little Dorrit herself, that this same society in which they lived, greatly resembled a superior sort of Marshalsea. Numbers of people seemed to come abroad, pretty much as people had come into the prison; through debt, through idleness, relationship, curiosity, and general unfitness for getting on at home. They were brought into these foreign towns in the custody of couriers and local followers, just as the debtors had been brought into the prison. They prowled about the churches and picture-galleries, much in the old, dreary, prison-yard manner. They were usually going away again to-morrow or next week, and rarely knew their own minds, and seldom did what they said they would do, or went where they said they would go: in all this again, very like the prison debtors. They paid high for poor accommodation, and disparaged a place while they pretended to like it: which was exactly the Marshalsea custom. They were envied when they went away by people left behind, feigning not to want to go: and that again was the Marshalsea habit invariably. A certain set of words and phrases, as much belonging to tourists as the College and the Snuggery belonged to the jail, was always in their mouths. They had precisely the same incapacity for settling down to anything, as the prisoners used to have; they rather deteriorated one another, as the prisoners used to do; and they wore untidy dresses, and fell into a slouching way of life: still, always like the people in the Marshalsea.

I know a person whose job brings her into frequent contact with the wealthy and she mentioned to me once that she thought having a trust fund to live on was a kind of curse. There are exceptions, but notwithstanding those, too much liberty doesn't work any better for most people than too little.

Poor, poor Lion. :'-(

Poor, poor Lion. :'-(Blandois aside, if I ever saw my husband treat a dog as Gowan did, he would live to regret it.

Thanks, Kim, for saving me the trouble of looking up Mr. Eustace.

I, too, made a note of that passage, Julie. Thank goodness the rigid expectations of Society have loosened somewhat, though they're still some vestiges. A friend of mine is a corporate wife and goes to certain functions with her husband, all for the sake of business. She doesn't seem to mind, but having to dress up to schmooze a bunch of my husband's business associates/clients is worse than prison for me. I had to do it for a few years, early in our marriage, and I hated it. If his career had hinged on my ability to host fabulous parties and make sparkling conversation, we'd have been sponging off relatives long ago. Makes me feel a little more compassionate towards Amy.

Kim wrote: "The last chapter of this installment is Chapter 7 titled "Mostly, Prunes and Prism" and we begin with Mrs. General trying to make Little Dorrit's lips look pretty among other things I suppose but n..."

Kim wrote: "The last chapter of this installment is Chapter 7 titled "Mostly, Prunes and Prism" and we begin with Mrs. General trying to make Little Dorrit's lips look pretty among other things I suppose but n..."Thanks for explaining about Mr. Eustace. I had no idea. peace, janz

And I am tiring of these newly rich. They remind me of some politicians and people in the press. Perhaps because I am old and know that I have enough or do not need more friends - most of my friends are dying off, I just tire of this nonsense of showing off. Where I have gone - what I have done. Oh, and my jewelry which I will give away to you to be your friend.

And I am tiring of these newly rich. They remind me of some politicians and people in the press. Perhaps because I am old and know that I have enough or do not need more friends - most of my friends are dying off, I just tire of this nonsense of showing off. Where I have gone - what I have done. Oh, and my jewelry which I will give away to you to be your friend. This book better get better - Dickens can do better than this. We have had enough of the family and "prunes and prisms" and elegant stuff. We get it. They are silly now that they are no longer in the debtors prison. I think Dickens is beating a dead horse now. peace, janz

I am getting tired of the Dorrits mostly. We'll manage though.

Hang in there. Some surprises are on the horizon. While not my favourite Dickens novel, there are nuggets of joy and mystery and wonderful prose still to come.

Oh, I will. I am also weird, I am getting tired of the Dorrits, but that is one of the things I do enjoy somehow. Even the protagonist(s) are not all wonderful. Now I won't feel guilty if some delightfully horrible thing happens to them that makes me gleeful. Because I also know they will not be rewarded for being such proud, egocentrical people.

I am also very proud of Uncle Frederick. He is the one who realizes how horrible they all are to Little Dorramy, and who is not afraid to tell them off for it. If only anyone else had done the same ... and if only Little Dorramy would stand up for herself a bit more. Wouldn't that be great? I do agree with Mrs. General on that, Amy would be way less annoying if she'd be a bit less subservient.

I am also very proud of Uncle Frederick. He is the one who realizes how horrible they all are to Little Dorramy, and who is not afraid to tell them off for it. If only anyone else had done the same ... and if only Little Dorramy would stand up for herself a bit more. Wouldn't that be great? I do agree with Mrs. General on that, Amy would be way less annoying if she'd be a bit less subservient.

Oh, thank you for bringing up Frederick! He finally comes out of his shell, and it's to berate them for their shabby treatment of Amy. Go, Freddie! He's been too quiet a character 'til now, and I keep waiting to see how he's going to fit into this little tale. More to come from him, I'm sure.

Oh, thank you for bringing up Frederick! He finally comes out of his shell, and it's to berate them for their shabby treatment of Amy. Go, Freddie! He's been too quiet a character 'til now, and I keep waiting to see how he's going to fit into this little tale. More to come from him, I'm sure.

Kim wrote: "Hello everyone,

We begin this week's installment with Chapter 5 of Book 2, titled "Something Wrong Somewhere". I had such high hopes for book 2. At the end of the first book I was hoping the Dorri..."

It seems the only time in the novel so far when Mrs. General shows any noticeable emotion is when Dorrit mentions he knows Merdle. “The Great Merdle” she exclaims. Merdle is known both in England and on the continent. I enjoyed how Dickens points out how Dorrit, who once was the centre of attraction as the Father of the Marshalsea, has now staked his claim as a man to be reckoned with in Venice. So much acting and pretence. How long can one person live in a world when he must constantly - over years - project an imagined image of himself to the world?

As to Hablot Browne, sigh, it is evident that, in general, his illustrations are not as intricate as in earlier novels. The tide of what was enjoyed by most the readers in the late 50’s had begun to change. Dickens’s prose evolved into a more evocative and detailed format. Browne was falling behind the times. Sigh again.

We begin this week's installment with Chapter 5 of Book 2, titled "Something Wrong Somewhere". I had such high hopes for book 2. At the end of the first book I was hoping the Dorri..."

It seems the only time in the novel so far when Mrs. General shows any noticeable emotion is when Dorrit mentions he knows Merdle. “The Great Merdle” she exclaims. Merdle is known both in England and on the continent. I enjoyed how Dickens points out how Dorrit, who once was the centre of attraction as the Father of the Marshalsea, has now staked his claim as a man to be reckoned with in Venice. So much acting and pretence. How long can one person live in a world when he must constantly - over years - project an imagined image of himself to the world?

As to Hablot Browne, sigh, it is evident that, in general, his illustrations are not as intricate as in earlier novels. The tide of what was enjoyed by most the readers in the late 50’s had begun to change. Dickens’s prose evolved into a more evocative and detailed format. Browne was falling behind the times. Sigh again.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 6 is titled "Something Right Somewhere" and so I am looking forward to pleasant things happening in the chapter but of course I'm wrong. We start with Henry Gowan "loitering moodily about o..."

Kim

Mr Gowan, well, Gowan because he is not a gentleman of who deserves the word Mister. Gowan is a cruel and sadistic person. When we were first introduced to Gowan he was on his way to the Meagles, Arthur observed Gowan kicking a stone. Beneath Gowan’s languid and seemingly unaffected exterior rests a violent individual. That he attracts the attention of Blandois is not surprising.

To what extent can we assume he is physically abusive to Pet? I recall earlier that someone pointed out that Bill Sykes killed his dog. He also killed his partner Nancy. Could such a fate exist in the future for Pet?

Kim

Mr Gowan, well, Gowan because he is not a gentleman of who deserves the word Mister. Gowan is a cruel and sadistic person. When we were first introduced to Gowan he was on his way to the Meagles, Arthur observed Gowan kicking a stone. Beneath Gowan’s languid and seemingly unaffected exterior rests a violent individual. That he attracts the attention of Blandois is not surprising.

To what extent can we assume he is physically abusive to Pet? I recall earlier that someone pointed out that Bill Sykes killed his dog. He also killed his partner Nancy. Could such a fate exist in the future for Pet?

Oh, no. I had not even thought of this. Perhaps I should stop reading now. But, as you point out with Nancy, Dickens is capable of murder. Perhaps Little Dorrit can rescue her. peace, janz

Oh, no. I had not even thought of this. Perhaps I should stop reading now. But, as you point out with Nancy, Dickens is capable of murder. Perhaps Little Dorrit can rescue her. peace, janz

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "Little Dorrit and Mrs. Gowan become friends and both women have an aversion to Blandois. When Mrs. Gowan bids goodbye to Amy before she leaves Venice, Blandois is there but Mrs. Gowan d..."

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "Little Dorrit and Mrs. Gowan become friends and both women have an aversion to Blandois. When Mrs. Gowan bids goodbye to Amy before she leaves Venice, Blandois is there but Mrs. Gowan d..."I also read that that as foreshadowing for Pet and I also hope she has a short life. Because a long one with that scoundrel would be torture. The way he speaks of her! It won't be long till he turns his hand on her.

For people who are so concerned with their previous position in society and apparently well to do birth, they very much seem to characterize nouveau riche.

For people who are so concerned with their previous position in society and apparently well to do birth, they very much seem to characterize nouveau riche. But I'm much more concerned with the nature of Mr. Dorrit's castigation of Ms. Amy. She does not mention the Marshalsea, but apparently just seeing her is enough to make the others think of it. I have not heard one complaint about Amy that is actually actionalble on her part.

It just seems so unfair that Mr. Dorrit goes on such a rampage about how he hates even the though of the prison and anything to to do with it, when it was quite literally Ms. Amy's whole life. Everything about her, her whole history and experience was life in the Marshalsea. Expecting her to overcome that in a matter of a few months is ridiculous. At least the other children had some time before the prison to compare to, even if they would only be hazy infant memories.

It almost feels as if Mr. Dorrit isn't repudiating just the prison, but Ms. Amy herself. What she is, is part of this wretched experience that he wishes to purge. But if Ms. Amy purges the Marshalsea from herself, what would be left?

If Ms. Amy hadn't kept up her forbidden correspondence with Mr. Clenmam, showing at least some amount of self interest, I may have consigned this one to the DNF and waited for out next read. But that one rebellious act of keeping in communication with him, has me intrigued.

Hooray for Avery. I agree, her letter will keep me dragging through the Dorrits and their fixation on class and money. Amy is showing a little spunk by writing the letter to Clennam and I am staying with it, too. Although, truth be told, I don't think I have ever put DNF on a Dickens book. peace, janz

Hooray for Avery. I agree, her letter will keep me dragging through the Dorrits and their fixation on class and money. Amy is showing a little spunk by writing the letter to Clennam and I am staying with it, too. Although, truth be told, I don't think I have ever put DNF on a Dickens book. peace, janz

I'm getting mightily fed up with the way the Dorrits are treating their servants. I hate the idea that people who have experience of living life as paupers can so quickly turn on the people in the station of life they were in.

I'm getting mightily fed up with the way the Dorrits are treating their servants. I hate the idea that people who have experience of living life as paupers can so quickly turn on the people in the station of life they were in.I do hope they get their comeuppance.

I'm looking forward to seeing how some of the characters back in London might tackle them. I hope that Mr Pancks regrets what he did for Mr Dorrit now. I certainly don't think Mr Dorrit is any happier than he was in the Marshalsea.

Peter wrote: "I recall earlier that someone pointed out that Bill Sykes killed his dog. He also killed his partner Nancy. Could such a fate exist in the future for Pet?"

Peter wrote: "I recall earlier that someone pointed out that Bill Sykes killed his dog. He also killed his partner Nancy. Could such a fate exist in the future for Pet?"Yes, that was what I was thinking of regarding the bad end with the dog in Oliver Twist. Now that it's in my head I really can't see things ending for Pet any other way--unless Gowan dies?

If Gowan dies, Minipet can return to her parents and serve them in remorse for the rest of her life (again, limited options for a girl who makes a bad choice in these books). I guess I'm rooting for that so she survives. And also because it would be awful for the Meagles to lose two daughters, plus a Tattycoram. I'm not crazy about the Meagleses, but that's a lot even for them.

David wrote: "I'm getting mightily fed up with the way the Dorrits are treating their servants. I hate the idea that people who have experience of living life as paupers can so quickly turn on the people in the ..."

David

You raise an interesting point.

I think that Mr Dorrit is actually a very unhappy person. Whether he is poor or rich he spends an great deal of energy trying to live up to a role, a false narrative of himself and who he is. In doing so he must constantly project an image of himself. Jung, in psychological terms would term it the persona/mask.

The more energy he spends projecting his image to society the more effort is required to maintain the pretence. In the end, this projection of the self generally does not turn out well.

We shall see.

David

You raise an interesting point.

I think that Mr Dorrit is actually a very unhappy person. Whether he is poor or rich he spends an great deal of energy trying to live up to a role, a false narrative of himself and who he is. In doing so he must constantly project an image of himself. Jung, in psychological terms would term it the persona/mask.

The more energy he spends projecting his image to society the more effort is required to maintain the pretence. In the end, this projection of the self generally does not turn out well.

We shall see.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "I recall earlier that someone pointed out that Bill Sykes killed his dog. He also killed his partner Nancy. Could such a fate exist in the future for Pet?"

Yes, that was what I was t..."

Hi Julie

We are getting close to the end of the novel. Dickens needs to resolve a few threads and one is certainly the fate of the Meagle family.

You are right. Three lost Meagles would be rather excessive.

Yes, that was what I was t..."

Hi Julie

We are getting close to the end of the novel. Dickens needs to resolve a few threads and one is certainly the fate of the Meagle family.

You are right. Three lost Meagles would be rather excessive.

Old Dorrit is an interesting psychological study, and it's important to remember how broken he is. A wrecked man -- discarded and tossed into debtor's prison, ashamed and embarrassed because of how far he has fallen -- starts lying and boasting in an attempt to escape himself. Imagine his surprise when he realizes it works and people start believing him. He is reinventing himself.

Old Dorrit is an interesting psychological study, and it's important to remember how broken he is. A wrecked man -- discarded and tossed into debtor's prison, ashamed and embarrassed because of how far he has fallen -- starts lying and boasting in an attempt to escape himself. Imagine his surprise when he realizes it works and people start believing him. He is reinventing himself. He has the perfect audience, all younger versions of himself. They all want to escape themselves. He is the king of the wretched, a man of great wisdom prone to giving worthless advice. He has found his calling.

Given all the positive feedback and respect he gets, it isn't long before he believes his own BS. He has found happiness and respect in delusion. And once that happens he becomes a pompous ass. Kings don't treat their servants well. Old Dorrit belongs back in prison; that's where he's safe. That's where his kingdom is.

Amy's life-arc, bless her heart, is entirely different. She finds meaning and value in helping others. When she can help, she is a force with purpose. When she can't, she is without purpose and shrinks into the background, reduced to a tagalong.

The worst thing that happened to Amy, and her dad, is riches.

PS: I also think Amy is the female character Dickens has been trying to create all along but kept failing at. He's finally perfected her. She is not the helpless heroine of past books. No, Amy rolls up her sleeves and works in the dirt. If she doesn't do it, no one will. And she soars.

Hi Xan

Great to hear from you. I think your assessment of both Amy and her father have much merit.

I never thought about Amy as being the female character that Dickens has been striving to create but I see your point. I think one thing that is so off-putting about her is the name Little Dorrit. The word little has many connotations, and when applied to a human, not many of those connotations are inspiring or remarkable descriptive words for a person.

I certainly agree with your observation that Amy rolls up her sleeves and works in the dirt. We don’t see such female characteristics in Esther of BH, or Dora or Agnes from DC, or Florence from D&S. I would suggest that Little Nell (ah, there’s the word little again) rolls up her sleeves, but she is never portrayed as an adult female who attracts the interest of respectable mature males. I don’t count Quilt as an earnest suitor.

It will be interesting to see how the remaining chapters bring her story to a conclusion.

Great to hear from you. I think your assessment of both Amy and her father have much merit.

I never thought about Amy as being the female character that Dickens has been striving to create but I see your point. I think one thing that is so off-putting about her is the name Little Dorrit. The word little has many connotations, and when applied to a human, not many of those connotations are inspiring or remarkable descriptive words for a person.

I certainly agree with your observation that Amy rolls up her sleeves and works in the dirt. We don’t see such female characteristics in Esther of BH, or Dora or Agnes from DC, or Florence from D&S. I would suggest that Little Nell (ah, there’s the word little again) rolls up her sleeves, but she is never portrayed as an adult female who attracts the interest of respectable mature males. I don’t count Quilt as an earnest suitor.

It will be interesting to see how the remaining chapters bring her story to a conclusion.

How did these people get married to each other? We have Gowen who seems to be on his way to hating his wife, and since he beat the dog I expect the same for his wife. The two "clever ones" forced Affery into marrying Flintwinch, how or why I have no idea. Arthur's parents certainly didn't seem to have anywhere near a perfect marriage, and Rigaud seemed to skip all the fighting in his marriage and just killed his wife.

"As his hand went up above his head and came down upon the table, it might have been a blacksmith's"

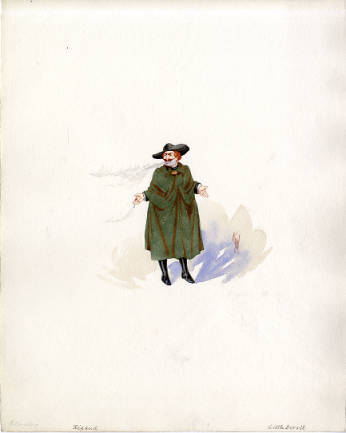

Book 2, Chapter 5

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"Uncle?" cried Fanny, affrighted and bursting into tears, "why do you attack me in this cruel manner? What have I done?"

"Done?" returned the old man, pointing to her sister's place, "where's your affectionate invaluable friend? Where's your devoted guardian? Where's your more than mother? How dare you set up superiorities against all these characters combined in your sister? For shame, you false girl, for shame!"

"I love Amy," cried Miss Fanny, sobbing and weeping, "as well as I love my life — better than I love my life. I don't deserve to be so treated. I am as grateful to Amy, and as fond of Amy, as it's possible for any human being to be. I wish I was dead. I never was so wickedly wronged. And only because I am anxious for the family credit."

"To the winds with the family credit!" cried the old man, with great scorn and indignation. "Brother, I protest against pride. I protest against ingratitude. I protest against any one of us here who have known what we have known, and have seen what we have seen, setting up any pretension that puts Amy at a moment's disadvantage, or to the cost of a moment's pain. We may know that it's a base pretension by its having that effect. It ought to bring a judgment on us. Brother, I protest against it in the sight of God!"

As his hand went up above his head and came down on the table, it might have been a blacksmith's. After a few moments' silence, it had relaxed into its usual weak condition. He went round to his brother with his ordinary shuffling step, put the hand on his shoulder, and said, in a softened voice, "William, my dear, I felt obliged to say it; forgive me, for I felt obliged to say it!" and then went, in his bowed way, out of the palace hall, just as he might have gone out of the Marshalsea room.

Commentary:

In the original serial illustrations that Phiz provided, this fifth chapter in the second book had no illustration, there being steel-engravings for both Chapters 3 and 6: "The Family Dignity is Affronted" (Part 11: October 1856) and "Instinct Stronger than Training" (Part 12: November 1856) respectively, the former illustration involving Fanny Dorrit, her aristocratic-looking father, and the Swiss innkeeper, and the latter the Dorrit sisters, Pet Gowan, Henry Gowan, and Blandois. The present Mahoney illustration realizes the normally timid Frederick Dorrit's indignation at Fanny's supercilious attitude towards her modest, self-sacrificing sister.

Wealth and their new social standing impose certain behavioral constraints upon the Dorrits, including the proper demeanor and attitudes for the young ladies. Consequently, Mr. Dorrit hires a governess of impeccable credentials, Mrs. General, an officer's widow, to inculcate the appropriate upper-middle-class manners, skills, etiquette, and biases in his daughters. Mrs. General's account of Miss Amy to her new employer is not entirely positive as she feels that Amy is not sufficiently assertive — and not sufficiently class-conscious. William Dorrit fears that her demeanor is suggestive of the taint of prison. In the present illustration, the normally retiring, elderly musician Frederick Dorrit stands up for Amy, expressing nothing less than indignation about Tip and Fanny's treatment of their good-hearted, serviceable sister. The other Dorrits think Frederick demented. Thus, Dickens shows the Dorrits are prisoners of their own biases and prejudices, and that, in ignoring questions of degree in favor of human sympathy, Amy is a true Dickensian heroine.

Supporting himself by gripping the chair-back, Frederick rebukes Fanny (right), who breaks down under her uncle's criticism of her recent conduct. William in glasses (left) and Tip with his monocle are astounded, failing to appreciate the truth of Frederick's accusations. Large, ornate oil-paintings in the hotel dining-room imply the opulence of the family's new surroundings, in Italy, as they take breakfast. Amy, of course, cannot be embarrassed by her uncle's spirited defense of her because she has just left the table, accompanied by Mrs. General. Mr. Dorrit (upper left) has just dropped his French newspaper in amazement at his normally shy brother's anguish, suggested by his hair standing up. Miss Fanny is "sobbing and weeping", as in the text, about to protest that she loves and is grateful to Amy: "And only because I am anxious for the family credit" — an interesting phrasing in light of the family's tight finances only recently being relieved.

Travelers of the early nineteenth century included not only learned or leisured aristocrats but also the new wealthy middle classes eager to take their families on a fashionable tour.

Already in the 1850s, however, the true cognoscenti were venturing further abroad, and the growth of railways and the availability of guidebooks made such continental travel far less exclusive than it would have been in the 1830s, when the action of the novel occurs. William Dorrit does not merely wish his daughters and vacuous son to acquire some sophistication and polish from a trip through Switzerland into Italy; he is attempting to re-invent his family as aristocracy, so that later he can introduce himself in London as having come from the Continent, rather than the Marshalsea.

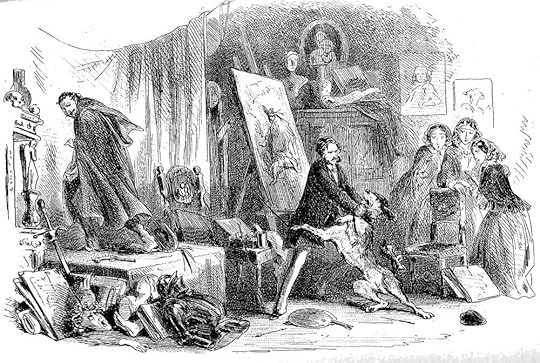

Instinct Stronger than Training

Chapter 6, Book 2

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

His face was so directed in reference to the spot where Little Dorrit stood by the easel, that throughout he looked at her. Once attracted by his peculiar eyes, she could not remove her own, and they had looked at each other all the time. She trembled now; Gowan, feeling it, and supposing her to be alarmed by the large dog beside him, whose head she caressed in her hand, and who had just uttered a low growl, glanced at her to say, "He won't hurt you, Miss Dorrit."

"I am not afraid of him," she returned in the same breath; "but will you look at him?"

In a moment Gowan had thrown down his brush, and seized the dog with both hands by the collar.

"Blandois! How can you be such a fool as to provoke him! By Heaven, and the other place too, he'll tear you to bits! Lie down! Lion! Do you hear my voice, you rebel!"

The great dog, regardless of being half-choked by his collar, was obdurately pulling with his dead weight against his master, resolved to get across the room. He had been crouching for a spring at the moment when his master caught him.

"Lion! Lion!" He was up on his hind legs, and it was a wrestle between master and dog. "Get back! Down, Lion! Get out of his sight, Blandois! What devil have you conjured into the dog?"

"I have done nothing to him."

"Get out of his sight or I can't hold the wild beast! Get out of the room! By my soul, he'll kill you!" — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 6.

Commentary:

Although Gowan secretly detests his new-found, foreign friend Monsieur Blandois of Paris, he finds him useful in deliberately upsetting his young wife to keep her in her place. But Gowan's great dog, recognizing Blandois for the villain he is, menaces the sinister Frenchman. In the illustration, Blandois is in the position of Henry Gowan's model, left, while the artist wrestles with the dog, center; to the right, the three young woman (Little Dorrit, Fanny, and Minnie Gowan) are alarmed by Gowan's brutal treatment of the heretofore gentle animal.

The scene is the romantic and rapidly decaying city of Venice, another instance in the novel of physical decadence. However, whereas Phiz here has illustrated the chapter set in Venice by portraying the studio of Henry Gowan above a bank on an islet, providing little local color but describing well the characters of the artist and the murderer, Blandois, the other illustrators of the novel at this point have been sure to include a gondola to underscore the exotic Italian setting. However, Mahoney's using the text of the closing of the chapter as his subject allows him to complement the original serial illustration by focusing on Blandois' comment that somebody (undoubtedly himself) has poisoned Lion, Gowan's great-hearted dog.

The reader experiences the scene in Phiz's steel-engraving from the perspective of the outsider, Little Dorrit. Upon entering the studio to visit Minnie Gowan, she finds Henry painting a portrait with his model, Blandois, in a hooded cloak in the act of turning away from the viewer. What is not shocking is the dog's growling at the devious Frenchman (which has just occurred), but rather how the fashionably-dressed Henry Gowan savagely rebukes the animal in the presence of the three young ladies — exhibiting his power over the brute by knocking the animal to the floor and (in the accompanying text) repeatedly kicking it until its jaws are bloody. Despite the civilised environment of the dilettante's studio, with its classical statues, bric-a-brac, armour, and sketches, the true subject is the savage nature of a supposedly modern, sophisticated young Englishman of the upper-middle class. Significantly, Phiz embeds emblems of violence around Blandois — a mediaeval broadsword beside him and a flintlock pistol on the platform at his feet. A gorgon's head and fragmentary female bust look up, apparently regarding Blandois rather than Gowan in alarm. Rather than kicking his faithful pet as in the text, Gowan in the illustration appears to be strangling the dog, just as he has been systematically suffocating Minnie (extreme right) emotionally.

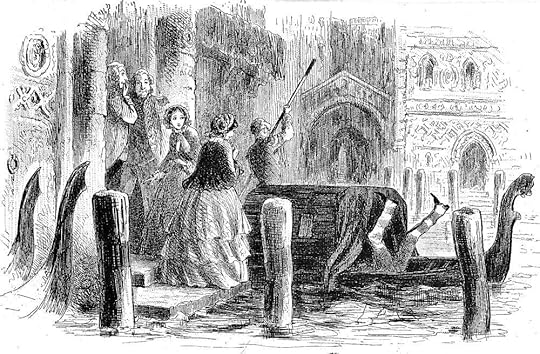

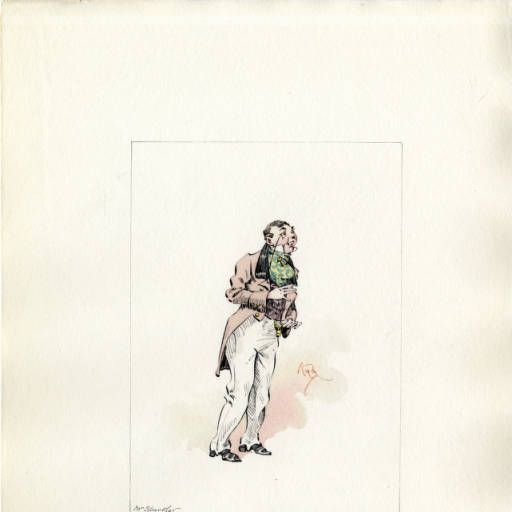

Mr. Sparkler under a Reverse of Circumstances

Chapter 6, Book 2

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

In effect, the swain was standing up in his gondola, card-case in hand, affecting to put the question to a servant. This conjunction of circumstances led to his immediately afterwards presenting himself before the young ladies in a posture, which in ancient times would not have been considered one of favourable augury for his suit; since the gondoliers of the young ladies, having been put to some inconvenience by the chase, so neatly brought their own boat in the gentlest collision with the bark of Mr. Sparkler, as to tip that gentleman over like a larger species of ninepin, and cause him to exhibit the soles of his shoes to the object of his dearest wishes: while the nobler portions of his anatomy struggled at the bottom of his boat in the arms of one of his men.

However, as Miss Fanny called out with much concern, Was the gentleman hurt, Mr Sparkler rose more restored than might have been expected, and stammered for himself with blushes, "Not at all so." Miss Fanny had no recollection of having ever seen him before, and was passing on, with a distant inclination of her head, when he announced himself by name. Even then she was in a difficulty from being unable to call it to mind, until he explained that he had had the honour of seeing her at Martigny. Then she remembered him, and hoped his lady-mother was well.

"Thank you," stammered Mr. Sparkler, "she's uncommonly well — at least, poorly." — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 6, "Something Right Somewhere.

Commentary:

After the melodramatic violence of Gowan's attack upon his own dog to preserve his model, Blandois, Dickens interjects a farcical scene in which Edmund Sparkler, Mrs. Merdle's son, in trying to give Fanny Dorrit has calling card, loses his balance and falls into the bottom of his gondola — a classic example of "streaky bacon" construction which alternates serious and comic scenes. Continuity between the previous, dramatic illustration and this comic interlude is afforded by the figures of Amy (left) and Fanny (center).

As in the companion illustration, "Instinct stronger than Training" in the same installment, the scene is the romantic and rapidly decaying city of Venice. However, whereas Phiz here had illustrated the chapter set in Venice by portraying the studio of Henry Gowan above a bank on an islet, he now provides both physical comedy and local color, putting young Sparkler in a characteristically awkward position while revealing Amy's genuine concern for his safety. Phiz has turned Fanny's face towards Edmund Sparkler, so that readers must supply Fanny's expression in witnessing the young man's discomfiture for themselves. Undoubtedly, Fanny is barely controlling a smile as she watches Sparkler's struggling to regain his composure, for this accident is certainly gratifying to a young woman who had been snubbed so recently by his mother.

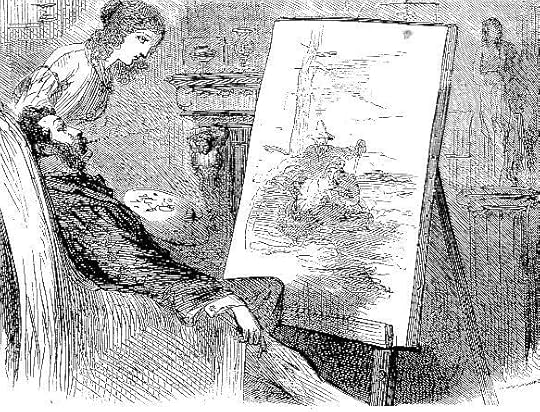

Mr. and Mrs. Henry Gowan

Chapter 6, Book 2

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Commentary:

The eighth paired character study to complement Dickens's narrative, Eytinge's "Mr. and Mrs. Henry Gowan," by virtue of its composition implies that the relationship between the former "Pet" Meagles and the artist Henry Gowan is imbalanced in that Gowan and his gigantic oil canvas on its easel fill the scene, whereas Minnie Gowan is jammed into the upper-left register. In a domestic scene laden with antique statuary, neoclassical cornices, and an elaborate fire-place mantel, the living female form, Minnie, seems a mere afterthought. The subject upon which the couple have focused their attention and which occupies the center of the illustration is the large canvas upon which Henry Gowan is still working and which, despite its foreign subject (Blandois in a cape at the Great Saint Bernard in Switzerland), is an extension of Gowan himself, who thus dominates the scene to the near exclusion of his young wife, who curiously regards the painting. Some two months into their European honeymoon, the relationship appears to be deteriorating.

Eytinge captures well the essence of Henry Gowan: the proud, "idle carelessness" and air of "degeneracy, "of being disappointed"; for example, as befits Eytinge's illustration, Henry Gowan constantly conveys the conviction that he has married beneath his class — despite the fact that Minnie's father, a banker, has paid his debts — and "against the wishes of his exalted relations", the Barnacles. Although this is a honeymoon scene set in Venice, the husband ignores his wife entirely as he studies the effect of his painting in Chapter 6, "Something Right Somewhere," of Book Two, "Riches." This would seem to be the relevant passage, shortly after the arrival of Fanny and Amy Dorrit, claiming mutual acquaintance with the Gowans through the Merdles, at the Gowans' home, although there is no precise correspondence between any passage in the chapter and the illustration:

"Don't be alarmed," said Gowan, coming from his easel behind the door. "It's only Blandois. He is doing duty as a model to-day. I am making a study of him. It saves me money to turn him to some use. We poor painters have none to spare."

Unable to realize visually his subject's false self-deprecation, Eytinge has nonetheless communicated well the essentials of Henry Gowan's nature. In order to adhere to his self-imposed two-character stricture, Eytinge has excluded other significant characters, including Amy and Fanny Dorrit, Gowan's dog Lion, and the elegantly attired Blandois (i. e., Rigaud), from the composition. Even though the illustrator has chosen a less sensational scene, it is one which nevertheless reveals the suave surface by focusing on his indolence rather than on the underlying meanness and brutality that he momentarily reveals in his attack on the dog, the shocking moment that concludes the episode. In balance, one may applaud Eytinge's choice of scene to realize in terms of his detailing, for so many of the scene's contributing elements — from the classical column (right) to the cigar dangling from Henry Gowan's lips — are completely atextual. Minnie looks timidly at her husband's creation, her face a blank of understanding and appreciation: the painting, like the painter himself, is, implies Eytinge, utterly beyond her limited comprehension.

Miss Fanny meets an acquaintance in Venice

Chapter 6, Book 2

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

In effect, the swain was standing up in his gondola, card-case in hand, affecting to put the question to a servant. This conjunction of circumstances led to his immediately afterwards presenting himself before the young ladies in a posture, which in ancient times would not have been considered one of favourable augury for his suit; since the gondoliers of the young ladies, having been put to some inconvenience by the chase, so neatly brought their own boat in the gentlest collision with the bark of Mr. Sparkler, as to tip that gentleman over like a larger species of ninepin, and cause him to exhibit the soles of his shoes to the object of his dearest wishes: while the nobler portions of his anatomy struggled at thebottom of his boat in the arms of one of his men.

However, as Miss Fanny called out with much concern, Was the gentleman hurt, Mr. Sparkler rose more restored than might have been expected, and stammered for himself with blushes, "Not at all so."

Miss Fanny had no recollection of having ever seen him before, and was passing on, with a distant inclination of her head, when he announced himself by name. Even then she was in a difficulty from being unable to call it to mind, until he explained that he had had the honour of seeing her at Martigny. Then she remembered him, and hoped his lady-mother was well.

"Thank you," stammered Mr. Sparkler, "she's uncommonly well — at least, poorly."

"In Venice?" said Miss Fanny.

"In Rome," Mr. Sparkler answered. "I am here by myself, myself. I came to call upon Mr. Edward Dorrit myself. Indeed, upon Mr. Dorrit likewise. In fact, upon the family."

Turning graciously to the attendants, Miss Fanny inquired whether her papa or brother was within? The reply being that they were both within, Mr. Sparkler humbly offered his arm.

Commentary:

Fin-de-siécle illustrator Harry Furniss's interpretation of the chapter in which Amy Dorrit has a disturbing experience with painter Henry Gowan and his model, who is none other than Blandois. However, here Furniss focuses on the comedic (Fanny's putting Edmund Sparkler in his place) rather than the melodramatic.

Whereas Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), the original serial illustrator, in Instinct Stronger than Learning had complemented the chapter set in Venice by portraying Gowan's studio above a bank on an islet, providing little local color but describing well the characters of the artist and the murderer, Blandois, the later illustrators of the novel at this point have been sure to include a gondola to underscore the exotic Italian setting. However, whereas James Mahoney's using the text of the closing of the chapter as his subject in allows him to re-work the original serial illustration by focusing on Blandois' comment that somebody has poisoned Gowan's dog, Furniss dwells upon Fanny's taking subtle revenge on Sparkler for his mother's refusal to recognize days before at the inn in Switzerland. Furniss thoroughly enjoys his exotic material and the lively gondoliers, an interpretation that may even owe something to The Gondoliers a light-hearted 1889 comic opera by Gilbert and Sullivan. It is easy, however, to lose track of the fatuous Sparkler, the designing Fanny, and Little Dorrit (center) amidst the Renaissance architecture on the Grand Canal.

Thanks, Peter. Good to be back.

Thanks, Peter. Good to be back.My expanded thoughts on Amy.

Dickens took great care describing Amy when we first meet her. He had a purpose in mind. He has always been trying to create a person of total goodness who is also steadfast in her beliefs. She is good but not helpless like so many of his other heroines.

IIRC, Dickens never believed Jesus was the son of God. He saw him as the great teacher of morality and decency, but as a man, not as a God. And he's always been trying to recreate this great teacher, but as a woman, not as a man, because it is women who have the capacity to love totally.

Little Dorrit isn't just little, she's amorphous. We are told her age, a young woman, but before that we are given her physical description. She is described as a young, pre-pubescent or just pubescent girl. I think the narrator even says it's difficult to tell her age by looking at her. She is portrayed as a child too young to have been corrupted by society -- innocence, purity, decency are the words that come to mind. And here she is doing good works. And she is diminished when she can't do them.

PS: I think in previous versions (Amys) Dickens confused helplessness with goodness. He corrects that here.

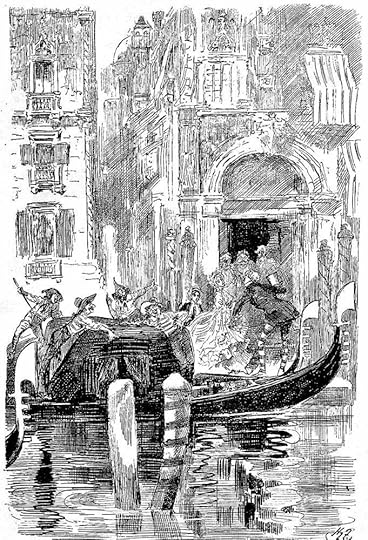

On the brink of the quay, they all came together."

Chapter 6, Book 2

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"The Merman with his light was ready at the box-door, and other Mermen with other lights were ready at many of the doors. The Dorrit Merman held his lantern low, to show the steps, and Mr. Sparkler put on another heavy set of fetters over his former set, as he watched her radiant feet twinkling down the stairs beside him. Among the loiterers here, was Blandois of Paris. He spoke, and moved forward beside Fanny.

Little Dorrit was in front with her brother and Mrs. General (Mr. Dorrit had remained at home), but on the brink of the quay they all came together. She started again to find Blandois close to her, handing Fanny into the boat.

"Gowan has had a loss," he said, "since he was made happy to-day by a visit from fair ladies."

"A loss?" repeated Fanny, relinquished by the bereaved Sparkler, and taking her seat.

"A loss," said Blandois. "His dog, Lion."

Little Dorrit's hand was in his, as he spoke.

"He is dead," said Blandois.

"Dead?" echoed Little Dorrit. "That noble dog?"

"Faith, dear ladies!" said Blandois, smiling and shrugging his shoulders, "somebody has poisoned that noble dog. He is as dead as the Doges!"

Commentary:

The emphasis in the illustration is divided between the black-clad Blandois and the angelic Amy, all in white. Fanny, Mrs. General, and the monocled Tip (Edward) are to the right.

Whereas Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz) had as his first illustration for the chapter set in Venice the dramatic scene in the studio of Henry Gowan above a bank on an islet, providing little local color but describing well the characters of the artist and the murderer, Blandois, the other illustrators of the novel at this point have been sure to include a gondola (the comic pratfalls of Edmund Sparkler in the original Phiz illustration Mr. Sparkler under a "Reverse of Circumstances" being Furniss's direct source of inspiration) to make the most of the exotic Italian setting. However, Mahoney's using the text of the closing of the chapter as his subject allows him to complement the original serial illustration by focusing on Blandois' comment that somebody (undoubtedly himself) has poisoned Lion, Gowan's great-hearted dog, whereas Furniss elected to focus on physical comedy.

With the judicious use of chiaroscuro, James Mahoney makes us the see the scene on the Venetian quay intensely, throwing Blandois' face and the flagstones into the light from the gondolier's lantern (left), and placing the tether-post and rope prominently in the foreground, while in the background a domed church (possibly San Michele in Isola) establishes the presence of the Renaissance city.

"Good-bye, my love! Good-bye!" The last words were spoken aloud as the vigilant Blandois stopped, turned his head, and looked at them from the bottom of the staircase."

Chapter 7, Book 2

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

". . . Mrs. Gowan whispered:

"He killed the dog."

"Does Mr. Gowan know it?" Little Dorrit whispered.

"No one knows it. Don't look towards me; look towards him. He will turn his face in a moment. No one knows it, but I am sure he did. You are?"

"I — I think so," Little Dorrit answered.

"Henry likes him, and he will not think ill of him; he is so generous and open himself. But you and I feel sure that we think of him as he deserves. He argued with Henry that the dog had been already poisoned when he changed so, and sprang at him. Henry believes it, but we do not. I see he is listening, but can't hear. Good-bye, my love! Good-bye!"

The last words were spoken aloud, as the vigilant Blandois stopped, turned his head, and looked at them from the bottom of the staircase. Assuredly he did look then, though he looked his politest, as if any real philanthropist could have desired no better employment than to lash a great stone to his neck, and drop him into the water flowing beyond the dark arched gateway in which he stood. No such benefactor to mankind being on the spot, he handed Mrs. Gowan to her boat, and stood there until it had shot out of the narrow view; when he handed himself into his own boat and followed."

Commentary:

Taking his cue from the original Phiz illustration for the previous chapter, Mahoney has the sardonic Blandois wait upon Henry Gowan's wife, Pet, and her new English friend, Amy Dorrit, at the base of the stairs in the Gowan flat in Venice. Both young women strongly suspect that the cruel and cunning Frenchman has poisoned Henry's mastiff because the dog threatened to attack him when he was serving as Henry's model in the studio above — but both are at a loss as how to prove that he is the malefactor, let alone how to persuade Henry that Blandois is hardly a friend. In fact, he terrifies both women, but they cannot determine how to eliminate him from Pet's life as long as Gowan cultivates his friendship in order to keep his wife off-balance. What neither young woman realizes is that Gowan secretly detests his new-found, foreign friend.

Although James Mahoney's illustration is successful insofar as it offers a visual characterization of these three characters, showing how their disparate paths have now crossed in Venice, the illustrator offers none of those interesting background details that inform the Italian scenes in the original serial. Although this is the chapter in which Mrs. General's marital "designs" upon William Dorrit become apparent, Mahoney has responded instead to Blandois' poisoning of Gowan's dog, and the putative menace that he represents to Pet, the elegantly dressed young woman with the sausage-roll curls, shawl, and elegant muff, dressed still in bridal white to distinguish her from the more serviceably attired Amy. In his villainous cloak, Blandois smirks at them both, as if he knows precisely what they are talking about — but cannot gather evidence to support their supposition. In the absence of anyone else whom she can trust, Pet has made a recent acquaintance into a confidante. The only ornamental element, the ornate balustrade, serves to connect the ladies to the right and Blandois to the left, and subtly emphasizes their descent to his level, when he hopes to have them in his power.

Prunes and Prism

Book 2 Chapter 7

Sol Eytinge Jr.

The Diamond Edition of Dicken's Little Dorrit 1871

Commentary:

The eleventh illustration, although entitled "Prunes and Prism," has as its subject the overbearing, class-conscious companion that Mr. Dorrit has engaged for his daughters on their Grand Tour, the unflappable Mrs. General. Although it would seem to complement the seventh chapter of Book Two, "Mostly Prunes and Prism," the title may be taken as an allusion to the following passage in an earlier chapter, in which she instructs Little Dorrit in elocution:

"I hope so," returned her father. "I — ha — I most devoutly hope so, Amy. I sent for you, in order that I might say — hum — impressively say, in the presence of Mrs. General, to whom we are all so much indebted for obligingly being present among us, on — ha — on this or any other occasion," Mrs General shut her eyes, "that I — ha hum — am not pleased with you. You make Mrs. General's a thankless task. You — ha — embarrass me very much. You have always (as I have informed Mrs. General) been my favourite child; I have always made you a — hum — a friend and companion; in return, I beg — I — ha — I do beg, that you accommodate yourself better to — hum — circumstances, and dutifully do what becomes your — your station."

Mr. Dorrit was even a little more fragmentary than usual, being excited on the subject and anxious to make himself particularly emphatic.

"I do beg," he repeated, "that this may be attended to, and that you will seriously take pains and try to conduct yourself in a manner both becoming your position as — ha — Miss Amy Dorrit, and satisfactory to myself and Mrs General."

That lady shut her eyes again, on being again referred to; then, slowly opening them and rising, added these words: —

"If Miss Amy Dorrit will direct her own attention to, and will accept of my poor assistance in, the formation of a surface, Mr. Dorrit will have no further cause of anxiety. May I take this opportunity of remarking, as an instance in point, that it is scarcely delicate to look at vagrants with the attention which I have seen bestowed upon them by a very dear young friend of mine? They should not be looked at. Nothing disagreeable should ever be looked at. Apart from such a habit standing in the way of that graceful equanimity of surface which is so expressive of good breeding, it hardly seems compatible with refinement of mind. A truly refined mind will seem to be ignorant of the existence of anything that is not perfectly proper, placid, and pleasant." Having delivered this exalted sentiment, Mrs. General made a sweeping obeisance, and retired with an expression of mouth indicative of Prunes and Prism. Book 2, Chapter 5, "Something Wrong Somewhere"

However, the imperious chaperon appears again in full sail, as it were, at the opening of Chapter 7, "Mostly Prunes and Prism," enforcing the proprieties, or, rather, imposing them on the Dorrit family from the mental vantage point of a coach box. Amy for her part attempts to accede to Mrs. General's attempts at "varnishing" of her surface as the socially correct one, hiding under layers of lacquer the real, the sensitive Little Dorrit, Child of the Marshalsea:

The wholesale amount of Prunes and Prism which Mrs. General infused into the family life, combined with the perpetual plunges made by Fanny into society, left but a very small residue of any natural deposit at the bottom of the mixture. This rendered confidences with Fanny doubly precious to Little Dorrit, and heightened the relief they afforded her.

"Amy," said Fanny to her one night when they were alone, after a day so tiring that Little Dorrit was quite worn out, though Fanny would have taken another dip into society with the greatest pleasure in life, "I am going to put something into your little head. You won't guess what it is, I suspect."

"I don't think that's likely, dear," said Little Dorrit.

"Come, I'll give you a clew, child," said Fanny. "Mrs. General."

Prunes and Prism, in a thousand combinations, having been wearily in the ascendant all day — everything having been surface and varnish and show without substance — Little Dorrit looked as if she had hoped that Mrs. General was safely tucked up in bed for some hours.

Fanny is perceptive enough to see what her sister Amy, pure of heart, is blind to, namely that, as Fanny tells her, "Mrs. General has designs on pa!"

In the 1999 BBC One adaptation of the novel, British actress Pam Ferris provided a performance informed by a perceptive reading the self-deceiving Dickens character who is so determined to enforce a rigid, upper-middle-class code of respectability and impose it upon the Dorrits:

Mrs General is a triumph of genteel respectability. A widow, she has set herself up as a 'companion to ladies'. She hates to be thought of as a working woman and when Mr. Dorrit employs her to 'finish' his daughters, she adopts the pretence that she is a friend of the family, rather than a governess. She is extremely strict about decorum, putting Amy and Fanny through a gruelling training regime.

The passage upon which Eytinge based his visual character study actually occurs in Book Two, Chapter 2 ("Mrs. General") which explains how Mr. Dorrit came to employ the widow as a companion on the European tour for his daughters:

In person, Mrs. General, including her skirts which had much to do with it, was of a dignified and imposing appearance; ample, rustling, gravely voluminous; always upright behind the proprieties. She might have been taken; had been taken — to the top of the Alps and the bottom of Herculaneum, without disarranging a fold in her dress, or displacing a pin. If her countenance and hair had rather a floury appearance, as though from living in some transcendently genteel Mill, it was rather because she was a chalky creation altogether, than because she mended her complexion with violet powder, or had turned grey. If her eyes had no expression, it was probably because they had nothing to express. If she had few wrinkles, it was because her mind had never traced its name or any other inscription on her face. A cool, waxy, blown-out woman, who had never lighted well.

Mrs. General had no opinions. Her way of forming a mind was to prevent it from forming opinions. She had a little circular set of mental grooves or rails on which she started little trains of other people's opinions, which never overtook one another, and never got anywhere. Even her propriety could not dispute that there was impropriety in the world; but Mrs. General's way of getting rid of it was to put it out of sight, and make believe that there was no such thing. This was another of her ways of forming a mind — to cram all articles of difficulty into cupboards, lock them up, and say they had no existence. It was the easiest way, and, beyond all comparison, the properest.

Thus, Dickens makes Mrs. General the exemplar of a social attitude (propriety) and in subsequent chapters gives her a distinct voice or verbal presence, but little in the way of physical features for the inspiration of an illustrator. Eytinge, of course, could reference Phiz's original images of Mrs. General for the Chapman and Hall serialization (in which the earlier illustrator has crammed the widow of the commissariat officer's widow into the lower right corner of "The Travellers," one of two illustrations for the eleventh monthly part, October 1856, but has not developed her), but otherwise he had to select a carriage and fashion appropriate to the above description. Eytinge departs from Phiz's depiction in that this 1871 "Mrs. General" has no massive bonnet and is not shown in full mourning. With her nose held high and lace at her wrists and throat, complemented by a lace handkerchief, Eytinge's figure is far more impressive than Phiz's, and certainly as "dignified and imposing" as Dickens would have his reader think her, although her floral "fascinator" headgear must have struck some of Eytinge's readers as a little fey — a suggestion of Italianate fashion, perhaps.

Julie wrote: "Did everyone like this passage as much as I did? It's not remotely subtle but it's well put.

Julie wrote: "Did everyone like this passage as much as I did? It's not remotely subtle but it's well put. It appeared on the whole, to Little Dorrit herself, that this same society in which they lived, great..."

Amen. My observation, too. We move from one community to the next and if there is not some real change, we fall into the same modes and patterns as the next community. Even those who wonder around the world have a pattern that we can observe. It is difficult for us to change. peace, janz

Peter wrote: "I think one thing that is so off-putting about her is the name Little Dorrit."

Peter wrote: "I think one thing that is so off-putting about her is the name Little Dorrit."It's even worse when you are reading out of my edition, which has a cover that makes Amy look about 7 years old:

https://sep.yimg.com/ca/I/yhst-137970...

What were they thinking?

Kim wrote: "

"As his hand went up above his head and came down upon the table, it might have been a blacksmith's"

Book 2, Chapter 5

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"Uncle?" cried ..."

An interesting commentary. I like how it suggested that Mr Dorrit was trying to invent his family as members of the aristocracy. Earlier in the novel he was the Father (patron) of the Marshalsea. He obviously likes being the person at the apex of the social hierarchy whether it be as a penniless man or a rich man.

This would enquire equal parts of endless energy to maintain the facade and a total lack of a grasp of reality. How can one sustain this energy forever?

"As his hand went up above his head and came down upon the table, it might have been a blacksmith's"

Book 2, Chapter 5

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"Uncle?" cried ..."

An interesting commentary. I like how it suggested that Mr Dorrit was trying to invent his family as members of the aristocracy. Earlier in the novel he was the Father (patron) of the Marshalsea. He obviously likes being the person at the apex of the social hierarchy whether it be as a penniless man or a rich man.

This would enquire equal parts of endless energy to maintain the facade and a total lack of a grasp of reality. How can one sustain this energy forever?

Kim wrote: "

Mr. and Mrs. Henry Gowan

Chapter 6, Book 2

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Commentary:

The eighth paired character study to complement Dickens's narrative, Eytinge's "Mr. and Mrs. Henry Gowan," by virtue of ..."