The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit, Book 2, Chp. 12-14

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 13 is titled "The Progress of an Epidemic" and although we are no longer at the home of Mr. Merdle we are still very much involved with Mr. Merdle. We get to hear more and more of how wonderful he is - in business anyway, and find that everyone seems to be talking of Mr. Merdle.

"As a vast fire will fill the air to a great distance with its roar, so the sacred flame which the mighty Barnacles had fanned caused the air to resound more and more with the name of Merdle. It was deposited on every lip, and carried into every ear. There never was, there never had been, there never again should be, such a man as Mr Merdle. Nobody, as aforesaid, knew what he had done; but everybody knew him to be the greatest that had appeared."

Down in Bleeding Heart Yard, where there was not one unappropriated halfpenny, still people talked of this "paragon of men" Merdle. Mrs. Plornish now is established in a small grocery and general trade shop with her father and Maggy acting as assistants, she talks of Merdle with her customers. Mr. Plornish now with a small share in a small builder's business talks of Merdle from on tops of scaffolds and tiles of houses. It is rumored that Mr. Baptist has given his savings for investment in one of Merdle's enterprises. Mr. Pancks when he goes through the yard collecting - or trying to - rent is told by the tenants that they don't have the money but would pay if they were "the rich gentleman whose name is in everybody's mouth".

Mr. Pancks often visits Mr. and Mrs. Plornish when he is finished working. Mrs. Plornish tells Pancks that their store isn't doing very well. They have plenty of business, but their neighbors buy things on credit and never pay for them. They then notice the behavior of Mr. Baptist - it seems as if he has had a fright and looks pale and agitated. Coming into the shop he tells them he has seen someone - "a bad man. A baddest man. I have hoped that I should never see him again". They get little information from him after this:

'Padrona, dearest,' returned the little foreigner whom she so considerately protected, 'do not ask, I pray. Once again I say it matters not. I have fear of this man. I do not wish to see him, I do not wish to be known of him—never again! Enough, most beautiful. Leave it.'

Shortly after this Arthur stops in on his way home from the factory. He had received a letter from Little Dorrit and wanted to share the news with the Plornishes. They are all pleased and interested, Mr. Pancks is especially pleased at his being specially remembered in the letter. As Arthur leaves for home Pancks accompanies him and Arthur asks him to stay for supper. Arthur and Pancks discuss Merdle and his enterprises, Arthur says even little Altro has been taken with Merdle. Pancks says the whole Yard have got it. He goes on to tell Arthur that he has invested with Mr. Merdle and advises Arthur to do the same. He says he's made the calculations, he's worked it and it's safe and genuine. He could invest the money from their business and recompense Doyle for his work and disappointments. He tells Arthur it's his duty to be as rich as he can, for Mr. Doyce who is growing old and for his mother who depends on him. The chapter ends with this:

"At intervals all next day, and even while his attention was fixed on other things, he thought of Mr Pancks's investment of his thousand pounds, and of his having 'looked into it.' He thought of Mr Pancks's being so sanguine in this matter, and of his not being usually of a sanguine character. He thought of the great National Department, and of the delight it would be to him to see Doyce better off. He thought of the darkly threatening place that went by the name of Home in his remembrance, and of the gathering shadows which made it yet more darkly threatening than of old. He observed anew that wherever he went, he saw, or heard, or touched, the celebrated name of Merdle; he found it difficult even to remain at his desk a couple of hours, without having it presented to one of his bodily senses through some agency or other. He began to think it was curious too that it should be everywhere, and that nobody but he should seem to have any mistrust of it. Though indeed he began to remember, when he got to this, even he did not mistrust it; he had only happened to keep aloof from it.

Such symptoms, when a disease of the kind is rife, are usually the signs of sickening."

"As a vast fire will fill the air to a great distance with its roar, so the sacred flame which the mighty Barnacles had fanned caused the air to resound more and more with the name of Merdle. It was deposited on every lip, and carried into every ear. There never was, there never had been, there never again should be, such a man as Mr Merdle. Nobody, as aforesaid, knew what he had done; but everybody knew him to be the greatest that had appeared."

Down in Bleeding Heart Yard, where there was not one unappropriated halfpenny, still people talked of this "paragon of men" Merdle. Mrs. Plornish now is established in a small grocery and general trade shop with her father and Maggy acting as assistants, she talks of Merdle with her customers. Mr. Plornish now with a small share in a small builder's business talks of Merdle from on tops of scaffolds and tiles of houses. It is rumored that Mr. Baptist has given his savings for investment in one of Merdle's enterprises. Mr. Pancks when he goes through the yard collecting - or trying to - rent is told by the tenants that they don't have the money but would pay if they were "the rich gentleman whose name is in everybody's mouth".

Mr. Pancks often visits Mr. and Mrs. Plornish when he is finished working. Mrs. Plornish tells Pancks that their store isn't doing very well. They have plenty of business, but their neighbors buy things on credit and never pay for them. They then notice the behavior of Mr. Baptist - it seems as if he has had a fright and looks pale and agitated. Coming into the shop he tells them he has seen someone - "a bad man. A baddest man. I have hoped that I should never see him again". They get little information from him after this:

'Padrona, dearest,' returned the little foreigner whom she so considerately protected, 'do not ask, I pray. Once again I say it matters not. I have fear of this man. I do not wish to see him, I do not wish to be known of him—never again! Enough, most beautiful. Leave it.'

Shortly after this Arthur stops in on his way home from the factory. He had received a letter from Little Dorrit and wanted to share the news with the Plornishes. They are all pleased and interested, Mr. Pancks is especially pleased at his being specially remembered in the letter. As Arthur leaves for home Pancks accompanies him and Arthur asks him to stay for supper. Arthur and Pancks discuss Merdle and his enterprises, Arthur says even little Altro has been taken with Merdle. Pancks says the whole Yard have got it. He goes on to tell Arthur that he has invested with Mr. Merdle and advises Arthur to do the same. He says he's made the calculations, he's worked it and it's safe and genuine. He could invest the money from their business and recompense Doyle for his work and disappointments. He tells Arthur it's his duty to be as rich as he can, for Mr. Doyce who is growing old and for his mother who depends on him. The chapter ends with this:

"At intervals all next day, and even while his attention was fixed on other things, he thought of Mr Pancks's investment of his thousand pounds, and of his having 'looked into it.' He thought of Mr Pancks's being so sanguine in this matter, and of his not being usually of a sanguine character. He thought of the great National Department, and of the delight it would be to him to see Doyce better off. He thought of the darkly threatening place that went by the name of Home in his remembrance, and of the gathering shadows which made it yet more darkly threatening than of old. He observed anew that wherever he went, he saw, or heard, or touched, the celebrated name of Merdle; he found it difficult even to remain at his desk a couple of hours, without having it presented to one of his bodily senses through some agency or other. He began to think it was curious too that it should be everywhere, and that nobody but he should seem to have any mistrust of it. Though indeed he began to remember, when he got to this, even he did not mistrust it; he had only happened to keep aloof from it.

Such symptoms, when a disease of the kind is rife, are usually the signs of sickening."

Our final chapter for this week is titled "Taking Advice" and we are unfortunately back in Rome with the Dorrit family. We find that Mrs. Merdle is circulating the news of Edmund's position saying that, yes, he had taken the place and that she hoped he might like it but she didn't know. It would keep him in town and he preferred the country, and if he liked it it was just as well he should have something to do. Henry Gowan goes around to all his acquaintances making sure everyone knew that he was delighted that Edmund had got the position, the only thing better would have been him getting it. He said it was the perfect job for Sparkler, there was nothing to do and he would do it charmingly. True. And it would have been perfect for Gowen too, I agree with him.

Fanny tells Amy that even though Pa is now extremely gentlemanly he is still in some respects, a little different from other gentlemen of fortune, partly on account of what he has gone through (mostly by being a Dorrit, they are all annoying.) Fanny thinks it may be up to her to carry the family through. She tells Amy that she is sure Mrs. General wants to marry their father. She says she will not stay and submit to Mrs. General, and she will not submit in any respect whatever to be patronized and tormented by Mrs. Merdle. She doubts whether she would want a clever husband and believes Sparkler will do for a husband, especially since he has been made a Lord of the Circumlocution Office. When Amy begs her not to marry Sparkler Fanny replies she has no intention of doing so to-night or tomorrow morning either, but she does not like their situation and wants to change it. While I am wondering how marrying Sparkler could possibly be a good idea knowing who his mother is she says this:

'One thing I could certainly do, my child: I could make her older. And I would!'

This was followed by another walk.

'I would talk of her as an old woman. I would pretend to know—if I didn't, but I should from her son—all about her age. And she should hear me say, Amy: affectionately, quite dutifully and affectionately: how well she looked, considering her time of life. I could make her seem older at once, by being myself so much younger. I may not be as handsome as she is; I am not a fair judge of that question, I suppose; but I know I am handsome enough to be a thorn in her side. And I would be!'

'My dear sister, would you condemn yourself to an unhappy life for this?'

I could see that actually working, so if she wants to spend her whole life making someone else miserable I guess she should go right ahead and marry the guy. Which is what is going to happen, for a few days after this Fanny and Edmund come to Amy and tell her that they are engaged. This is the end of the chapter:

"When he was gone, she said, 'O Fanny, Fanny!' and turned to her sister in the bright window, and fell upon her bosom and cried there. Fanny laughed at first; but soon laid her face against her sister's and cried too—a little. It was the last time Fanny ever showed that there was any hidden, suppressed, or conquered feeling in her on the matter. From that hour the way she had chosen lay before her, and she trod it with her own imperious self-willed step."

And now I finally get to say it, poor, poor Fanny.

Fanny tells Amy that even though Pa is now extremely gentlemanly he is still in some respects, a little different from other gentlemen of fortune, partly on account of what he has gone through (mostly by being a Dorrit, they are all annoying.) Fanny thinks it may be up to her to carry the family through. She tells Amy that she is sure Mrs. General wants to marry their father. She says she will not stay and submit to Mrs. General, and she will not submit in any respect whatever to be patronized and tormented by Mrs. Merdle. She doubts whether she would want a clever husband and believes Sparkler will do for a husband, especially since he has been made a Lord of the Circumlocution Office. When Amy begs her not to marry Sparkler Fanny replies she has no intention of doing so to-night or tomorrow morning either, but she does not like their situation and wants to change it. While I am wondering how marrying Sparkler could possibly be a good idea knowing who his mother is she says this:

'One thing I could certainly do, my child: I could make her older. And I would!'

This was followed by another walk.

'I would talk of her as an old woman. I would pretend to know—if I didn't, but I should from her son—all about her age. And she should hear me say, Amy: affectionately, quite dutifully and affectionately: how well she looked, considering her time of life. I could make her seem older at once, by being myself so much younger. I may not be as handsome as she is; I am not a fair judge of that question, I suppose; but I know I am handsome enough to be a thorn in her side. And I would be!'

'My dear sister, would you condemn yourself to an unhappy life for this?'

I could see that actually working, so if she wants to spend her whole life making someone else miserable I guess she should go right ahead and marry the guy. Which is what is going to happen, for a few days after this Fanny and Edmund come to Amy and tell her that they are engaged. This is the end of the chapter:

"When he was gone, she said, 'O Fanny, Fanny!' and turned to her sister in the bright window, and fell upon her bosom and cried there. Fanny laughed at first; but soon laid her face against her sister's and cried too—a little. It was the last time Fanny ever showed that there was any hidden, suppressed, or conquered feeling in her on the matter. From that hour the way she had chosen lay before her, and she trod it with her own imperious self-willed step."

And now I finally get to say it, poor, poor Fanny.

Kim wrote: "to me seemed like quite a long chapter and quite an uninteresting chapter..."

Kim wrote: "to me seemed like quite a long chapter and quite an uninteresting chapter..."To me, too, Kim. Seemed like a long way to go, just to get to the point that Sparkler got a government appointment. And that Merdle doesn't really seem like a happy, fulfilled man, despite all his fame and wealth. I think I detect a theme here...

Kim wrote: "Chapter 13 is titled "The Progress of an Epidemic" and although we are no longer at the home of Mr. Merdle we are still very much involved with Mr. Merdle. We get to hear more and more of how wonde..."

Kim wrote: "Chapter 13 is titled "The Progress of an Epidemic" and although we are no longer at the home of Mr. Merdle we are still very much involved with Mr. Merdle. We get to hear more and more of how wonde..."It can never be a good sign when the author/narrator equates investing with an epidemic. While I'd like to trust Pancks' research (since he did such a thorough, successful job tracking down the Dorrit fortune), one can't help but be wary that these characters we're fond of are speculating with money they may not be able to afford to risk. And now Arthur may well be considering such a move. My spidey-senses are tingling.

Kim wrote: "Fanny laughed at first; but soon laid her face against her sister's and cried too—a little. It was the last time Fanny ever showed that there was any hidden, suppressed, or conquered feeling in her on the matter. From that hour the way she had chosen lay before her, and she trod it with her own imperious self-willed step."

Kim wrote: "Fanny laughed at first; but soon laid her face against her sister's and cried too—a little. It was the last time Fanny ever showed that there was any hidden, suppressed, or conquered feeling in her on the matter. From that hour the way she had chosen lay before her, and she trod it with her own imperious self-willed step."And now I finally get to say it, poor, poor Fanny...."

Really? I think our sympathy might be better directed to poor, poor Sparkler! He's a bit of an idiot but, I think, is sincere when it comes to his affection for Fanny, misplaced though it may be.

I will give Fanny a bit of credit, though. If the narrator is to be believed, she made what she thought to be a practical, business decision in accepting Edward, and will now live with it, with no bigodd nonsense about it, i.e. no whining. I've known too many women who marry, or stay with, men knowing full-well their faults, and then spend all their time complaining about them. So, good for Fanny. She gave in to self-pity once, briefly, and now, it seems, is going to accept what is, and make the best of it.

PS It's nice that the Plornishes have stepped in to help look out for Maggy in Amy's absence.

I feel sorry for both of them to be honest, or more, for every person who has gotten married in this book up until now. So many bad choices, and wether they marry for love (like Minipet) or for other reasons, no one wins. Except perhaps Gowan, he has his pretty wife to misuse (and probably abuse), and the rich parents to buy off his debts.

Mary Lou wrote: "I will give Fanny a bit of credit, though. If the narrator is to be believed, she made what she thought to be a practical, business decision in accepting Edward, and will now live with it, with no bigodd nonsense about it, i.e. no whining. I've known too many women who marry, or stay with, men knowing full-well their faults, and then spend all their time complaining about them. So, good for Fanny. She gave in to self-pity once, briefly, and now, it seems, is going to accept what is, and make the best of it."

I do agree here, and it reminds me of that time I was just married to my wonderful autistic husband, and out of interest I joined a facebook group for wives of autistic men. I didn't know how fast I could run, all they could do was whine about how horrible their men were and how hard it was to be married to them. Basically they all thought autistics couldn't be capable of love. Meanwhile I am married to the most wonderful, loving, sweet man ever (and in my turn I love him very much, even after I got my diagnosis myself, tyvm). We both have our odds and our manual, but who doesn't?

I hope Fanny and Edmund will get to that spot where they at least respect each other, even if they are not perfect. I fear that while she is resolved to bear her burdens, Fanny will not respect Edmund and she will only see him as a burden though.

Mary Lou wrote: "I will give Fanny a bit of credit, though. If the narrator is to be believed, she made what she thought to be a practical, business decision in accepting Edward, and will now live with it, with no bigodd nonsense about it, i.e. no whining. I've known too many women who marry, or stay with, men knowing full-well their faults, and then spend all their time complaining about them. So, good for Fanny. She gave in to self-pity once, briefly, and now, it seems, is going to accept what is, and make the best of it."

I do agree here, and it reminds me of that time I was just married to my wonderful autistic husband, and out of interest I joined a facebook group for wives of autistic men. I didn't know how fast I could run, all they could do was whine about how horrible their men were and how hard it was to be married to them. Basically they all thought autistics couldn't be capable of love. Meanwhile I am married to the most wonderful, loving, sweet man ever (and in my turn I love him very much, even after I got my diagnosis myself, tyvm). We both have our odds and our manual, but who doesn't?

I hope Fanny and Edmund will get to that spot where they at least respect each other, even if they are not perfect. I fear that while she is resolved to bear her burdens, Fanny will not respect Edmund and she will only see him as a burden though.

I agree. I would not bet on a good marriage for Fanny - to anyone. She is so selfish and so pretentious and so eager to befriend "little" sister - and helps make her little. As for Edmund - he does not even have a brain, does he? Whoever marries him marries a burden for life (or as long as they stay married). I am still betting on Clennan and Amy. What does age matter? We know by now that they both like each other. Love? Who knows? That's why we have imaginations. peace, janz

I agree. I would not bet on a good marriage for Fanny - to anyone. She is so selfish and so pretentious and so eager to befriend "little" sister - and helps make her little. As for Edmund - he does not even have a brain, does he? Whoever marries him marries a burden for life (or as long as they stay married). I am still betting on Clennan and Amy. What does age matter? We know by now that they both like each other. Love? Who knows? That's why we have imaginations. peace, janz

I want to say Edmund will be a better husband than Fanny will be a wife. I don't know though ... I once dated a man without a brain, and it is exhausting. Still, at least he loves her, if you can call that infatuation love.

Indeed, age should not matter, but more than 20 years is a lot. Not as much as Esther would have had with Jarndyce though. I still think Arthur is a stalking creep, but he will make her a lot happier than her family does, won't he?

Indeed, age should not matter, but more than 20 years is a lot. Not as much as Esther would have had with Jarndyce though. I still think Arthur is a stalking creep, but he will make her a lot happier than her family does, won't he?

Kim wrote: "Hello Everyone,

This week's installment begins with Chapter 12 titled "In Which a Great Patriotic Conference Is Holden" (is holden even a word?) and to me seemed like quite a long chapter and quit..."

Yes. Merdle is a rather dry and unmemorable character. He doesn’t sparkle like his stepson or project himself as being expansive or showy as his wife. He seems to be a Midas-like character. I too found he just popped up into our plot again. For what purpose?

Yes, the first line of the chapter is a warning shot across the bow of our reading awareness. At this late point in the novel it seems that the Barnacles will continue to be a part of the novel in a role of humour and social/economic frustration but will not create a final disruptive plot event that is surely still coming in the novel.

Will Blandois create havoc, will Arthur’s world remain in limbo and unresolved, will Amy find true love, will Merdle become a risk to the financial stability of England?

Dickens still has many plot threads to follow this late in the novel.

This week's installment begins with Chapter 12 titled "In Which a Great Patriotic Conference Is Holden" (is holden even a word?) and to me seemed like quite a long chapter and quit..."

Yes. Merdle is a rather dry and unmemorable character. He doesn’t sparkle like his stepson or project himself as being expansive or showy as his wife. He seems to be a Midas-like character. I too found he just popped up into our plot again. For what purpose?

Yes, the first line of the chapter is a warning shot across the bow of our reading awareness. At this late point in the novel it seems that the Barnacles will continue to be a part of the novel in a role of humour and social/economic frustration but will not create a final disruptive plot event that is surely still coming in the novel.

Will Blandois create havoc, will Arthur’s world remain in limbo and unresolved, will Amy find true love, will Merdle become a risk to the financial stability of England?

Dickens still has many plot threads to follow this late in the novel.

This novel is certainly not a manual for how to select a partner for marriage or a study of what couples have done to create their individual happy marriages. Does the Plornish marriage provide the simple formula of caring for each other, caring for their neighbours and friends, and living an honest and hard-working life?

I don’t feel sorry for Fanny but Little Nell will always have my sympathy.

I liked Fanny for about a half chapter. Overall, I find her ungrateful, insensitive and too self-centred. She knows what her sparkling husband is like, and yet she marries him. Why? Well, money and prestige and a social standing. In some ways I see her as being a more successful and socially aware version of her father.

William Dorrit had to work to maintain his own facade of importance and social standing. He had to pretend to be accepted by constantly surrounding himself with the attention of others, accepting their pennies and their and cigars to validate his own existence. The harder he worked at creating and maintaining his facade the deeper he dug a psychological hole for himself.

On the other hand, Fanny was initially an actress. What a perfect beginning for a person who would then slip into the role of woman and wife. Let’s go back to the Phiz illustration for the Frontispiece of the novel. In it we see Fanny and Amy arriving at the Merdle home. Fanny is, symbolically, entering into a new environment. If we look at her head it is tilted up. Fanny’s world will, in time, ascend. Amy enters the home as well, but the reader knows the two sisters are diagrammatically different people. In the frontispiece Amy is looking straight forward. If we look at the title page illustration we see Amy emerging from the Marshalsea. Her look is directly forward. She is entering the world determined to be successful in her endeavours. If one compares the posture of Amy in the frontispiece to that of her in title page we see the same pose of Amy. Amy is steadfast. Two doors. Amy is the same no matter where she passes through.

Money to Amy is unimportant. She uses whatever she earns for the maintenance of her father. Fanny will learn to use money as well, but for her own profit.

I don’t feel sorry for Fanny but Little Nell will always have my sympathy.

I liked Fanny for about a half chapter. Overall, I find her ungrateful, insensitive and too self-centred. She knows what her sparkling husband is like, and yet she marries him. Why? Well, money and prestige and a social standing. In some ways I see her as being a more successful and socially aware version of her father.

William Dorrit had to work to maintain his own facade of importance and social standing. He had to pretend to be accepted by constantly surrounding himself with the attention of others, accepting their pennies and their and cigars to validate his own existence. The harder he worked at creating and maintaining his facade the deeper he dug a psychological hole for himself.

On the other hand, Fanny was initially an actress. What a perfect beginning for a person who would then slip into the role of woman and wife. Let’s go back to the Phiz illustration for the Frontispiece of the novel. In it we see Fanny and Amy arriving at the Merdle home. Fanny is, symbolically, entering into a new environment. If we look at her head it is tilted up. Fanny’s world will, in time, ascend. Amy enters the home as well, but the reader knows the two sisters are diagrammatically different people. In the frontispiece Amy is looking straight forward. If we look at the title page illustration we see Amy emerging from the Marshalsea. Her look is directly forward. She is entering the world determined to be successful in her endeavours. If one compares the posture of Amy in the frontispiece to that of her in title page we see the same pose of Amy. Amy is steadfast. Two doors. Amy is the same no matter where she passes through.

Money to Amy is unimportant. She uses whatever she earns for the maintenance of her father. Fanny will learn to use money as well, but for her own profit.

Like Kim, I found this week's initial chapter utterly boring and had to force myself through it, and while I did so I asked myself two things. First, the question occurred to me whether the lengthy description of the dinner party was done on purpose by Dickens - in order to illustrate the boredom and lack of spirit that is typical of Society, where everything is dictated by social rules and originality is frowned upon. If so, he did a marvellous job, but not one that is easily appreciated by the reader Tristram. My second question centred on Merdle himself: On the whole, he is supposed to be a negative figure, and in the light of the title of the following chapter, we are bound to expect that Mr Merdle's financial transactions will create ruin (if maybe not for himself, then for hundreds of investors), and yet I somehow feel sorry for this man, who is even intimidated by his Butler and who does not have it in himself to speak one sentence without blushing or looking down. This, however, raised a question in me: How are we supposed to believe that a man who is so diffident and insecure is taken as a financial genius? How can he convince, ensare and inveigle other people? Businessmen of his calibre are usually very self-confident, overbearing people, determined, ruthless and not likely to dither and to hide. In a way, Mr Merdle and his role in the novel does not really make sense to me at all.

Peter wrote: "She knows what her sparkling husband is like, and yet she marries him. Why? Well, money and prestige and a social standing. In some ways I see her as being a more successful and socially aware version of her father. "

It's even worse, Peter: Fanny does not marry for money and social prestige. She simply marries out of spite, namely in order to be able to humiliate for future mother-in-law. She really and truly joins her own life to the lot of a man she despises - but from his behaviour towards Amy, I noticed that Sparkler is quite a nice person - just to be able to quarrel with his mother on an equal basis. How absurd can a person become?

Fanny also seems desperate to marry at all - simply because she does not like to live in a household where Mrs. General might very soon take over the role of her mother. She tells her sister that she would like to marry a cleverer man, but that there are no clever men available in her sphere of society. So, apart from her feud with Mrs Merdle, Mr Sparkler seems to be her only ticket into a realm of relative independence. This tells us quite a lot about the range of opportunities Victorian society allowed even women of higher social status.

Did you notice, by the way, Amy's romantic outburst when she tells Fanny that you ought to marry for love. I wonder if she is speaking from experience here? ;-)

It's even worse, Peter: Fanny does not marry for money and social prestige. She simply marries out of spite, namely in order to be able to humiliate for future mother-in-law. She really and truly joins her own life to the lot of a man she despises - but from his behaviour towards Amy, I noticed that Sparkler is quite a nice person - just to be able to quarrel with his mother on an equal basis. How absurd can a person become?

Fanny also seems desperate to marry at all - simply because she does not like to live in a household where Mrs. General might very soon take over the role of her mother. She tells her sister that she would like to marry a cleverer man, but that there are no clever men available in her sphere of society. So, apart from her feud with Mrs Merdle, Mr Sparkler seems to be her only ticket into a realm of relative independence. This tells us quite a lot about the range of opportunities Victorian society allowed even women of higher social status.

Did you notice, by the way, Amy's romantic outburst when she tells Fanny that you ought to marry for love. I wonder if she is speaking from experience here? ;-)

I can't stop bashing Clennam, I know, but did you notice that when he paid his visit to the Plornishes in order to read Amy's letter to them, he was, once again, eager not to stay too long. When Mrs Plornish offered him some tea, he declined, wanting to make his visit as short as possible. - Mr F.'s aunt is right: That chap is a proud one!

Talking about the Plornishes, I am quite worried about them because it is clear that Mrs Plornish, with her readiness to give credit to all the Bleeding Hearts, is on the brink of bankruptcy. Hopefully, her husband's new job is good enough to pull them all through because otherwise, poor Mr Nandy will have to return to the workhouse again sooner or later.

Talking about the Plornishes, I am quite worried about them because it is clear that Mrs Plornish, with her readiness to give credit to all the Bleeding Hearts, is on the brink of bankruptcy. Hopefully, her husband's new job is good enough to pull them all through because otherwise, poor Mr Nandy will have to return to the workhouse again sooner or later.

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "She knows what her sparkling husband is like, and yet she marries him. Why? Well, money and prestige and a social standing. In some ways I see her as being a more successful and socia..."

If Amy is not speaking from any experience in love she is, perhaps, speaking in anticipation of love. ;-)

If Amy is not speaking from any experience in love she is, perhaps, speaking in anticipation of love. ;-)

Tristram wrote: "I can't stop bashing Clennam, I know, but did you notice that when he paid his visit to the Plornishes in order to read Amy's letter to them, he was, once again, eager not to stay too long. When Mr..."

Ah, the irony of the characters. Mrs Plornish is willing and able to help anyone and everyone out of the kindness of her heart while the Merdle’s of the world eagerly scheme to scam their way through life. On top of that we have the Barnacles of life who are, well, barnacles of the sides of life. They cling, feed and disrupt the smooth movement of a society from moving forward.

Ah, the irony of the characters. Mrs Plornish is willing and able to help anyone and everyone out of the kindness of her heart while the Merdle’s of the world eagerly scheme to scam their way through life. On top of that we have the Barnacles of life who are, well, barnacles of the sides of life. They cling, feed and disrupt the smooth movement of a society from moving forward.

Tristram wrote: "I can't stop bashing Clennam, I know, but did you notice that when he paid his visit to the Plornishes in order to read Amy's letter to them, he was, once again, eager not to stay too long. When Mr..."

Tristram wrote: "I can't stop bashing Clennam, I know, but did you notice that when he paid his visit to the Plornishes in order to read Amy's letter to them, he was, once again, eager not to stay too long. When Mr..."Clenham is kind of meh! isn't he? Nice guy, though. Shows you how far nice gets you :-) Having said that, Clenham's tour of the Circumlocution Office, along with the explanation of its mission, was worth putting up with Clenham for the entire book.

Mr. F's aunt is the breakout star, though. Flora, so agreeable with so much pent up hostility, could not survive without her puppet aunt. Flora says what's appropriate, and then auntie lets them know how Flora really feels about them. I can visualize Flora with her hand up auntie's back, throwing her voice. Nice trick if you can pull it off. Everyone should have a puppet with them while in polite company. I sometimes think Flora created auntie out of sheer will.

Love your analysis of Flora. I could only tolerate her for two minutes in the real world. Such a child. So full of nothing. But the aunt! Wow!. Thanks for the insight. peace, janz

Love your analysis of Flora. I could only tolerate her for two minutes in the real world. Such a child. So full of nothing. But the aunt! Wow!. Thanks for the insight. peace, janz

Tristram wrote: "I can't stop bashing Clennam, I know, but did you notice that when he paid his visit to the Plornishes in order to read Amy's letter to them, he was, once again, eager not to stay too long. When Mr..."

Well thanks for giving me another reason not to like the man who has to be in the center of everyone else's lives whether he's wanted or not.

Well thanks for giving me another reason not to like the man who has to be in the center of everyone else's lives whether he's wanted or not.

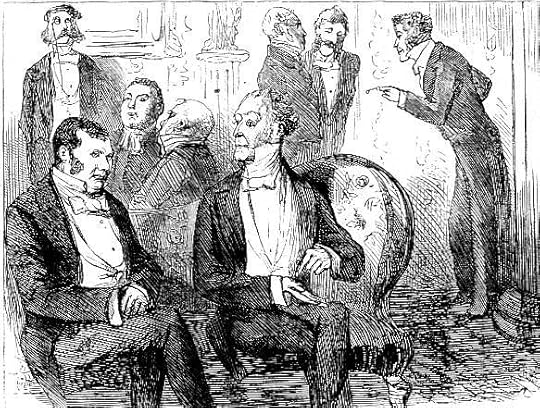

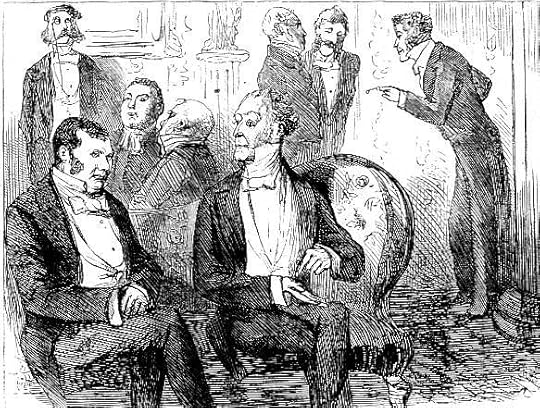

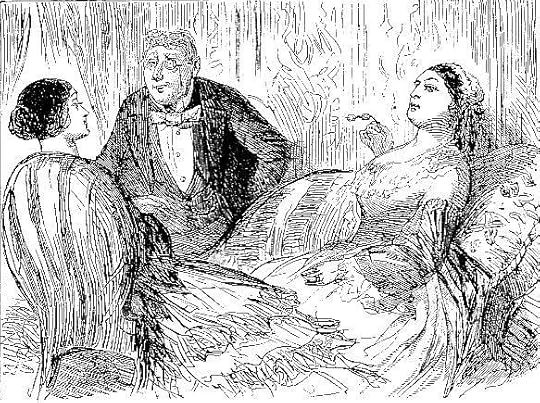

Book II Chapter 12 - Phiz

The patriotic conference

Book II Chapter 12

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Mr. Merdle issued invitations for a Barnacle dinner. Lord Decimus was to be there, Mr. Tite Barnacle was to be there, the pleasant young Barnacle was to be there; and the Chorus of Parliamentary Barnacles who went about the provinces when the House was up, warbling the praises of their Chief, were to be represented there. It was understood to be a great occasion. Mr. Merdle was going to take up the Barnacles.

Bar was truly repentant, and would not say another syllable. Would Bishop favour him with half-a-dozen words? (He had now set Mr. Merdle down on a couch, side by side with Lord Decimus, and to it they must go, now or never.)

And now the rest of the company, highly excited and interested, always excepting Bishop, who had not the slightest idea that anything was going on, formed in one group round the fire in the next drawing-room, and pretended to be chatting easily on the infinite variety of small topics, while everybody's thoughts and eyes were secretly straying towards the secluded pair. The Chorus were excessively nervous, perhaps as labouring under the dreadful apprehension that some good thing was going to be diverted from them! Bishop alone talked steadily and evenly. He conversed with the great Physician on that relaxation of the throat with which young curates were too frequently afflicted, and on the means of lessening the great prevalence of that disorder in the church. Physician, as a general rule, was of opinion that the best way to avoid it was to know how to read, before you made a profession of reading. Bishop said dubiously, did he really think so? And Physician said, decidedly, yes he did."

Commentary:

Accordingly, the novelist's treatment of the "patriotic" conference for bringing Merdle and Lord Decimus Barnacle together to arrange a rich bit of patronage is very much in the traditions of political caricature, if not literary allegory. Bar, Bishop, Physician, and Chorus are representative types rather than individuals, and this is consistent with all of the Barnacle imagery. Yet, except for the Bishop's collar, there is no way of distinguishing the types in Browne's illustration, The Patriotic Conference (Bk. 2, ch. 12). If we read ahead, we find that the three men shown behind Merdle and Lord Decimus are the "Chorus," while Bishop's companion is Physician, but in earlier Dickens novels one would not have to consult the text this closely in order to understand an illustration (whereas in "Sixties" illustrations the picture usually relies heavily on the text). Phiz's men are realized as individuals, not as types. One of his problems here is that Dickens has virtually dispensed with physical description beyond Merdle's habit of taking himself into custody. Yet were Phiz to label the characters with obvious symbols of their professions, the result would seem primitive, and jar with the rest of his work in this novel.

In this instance, it is difficult to dispute the argument that Dickens no longer needs an illustrator: illustrations do not work for this particular episode because Dickens chose to make use of a highly stylized, nonrealistic technique. His private imagination is still visual, however, as can be inferred from his instruction to Browne, "Don't have Lord Decimus's hand put out, because that looks condescending; and I want him to be upright, stiff, unmixable with more mortality" — an instruction Browne followed as best he could.

The only figure whose clothing suggests his profession, as Steig notes, is the Church of England Bishop, right. Above him, one of the dinner guests, presumably a connoisseur of art, with his eyeglass studies the details in a seventeenth-century Dutch painting of cattle such as those by Cuyp and Paulus Potter: "his Lordship composed himself into the picture after Cuyp, and made a third cow in the group" gave Phiz a hint as to how the powerbrokers might be arranged, and then Phiz actually incorporated such a painting into the background. However, the man at the painting is not Lord Decimus, for Merdle and Lord Decimus are the well-dressed, middle-aged businessmen in the left foreground — and in this cameo Merdle even resembles somewhat his real-life original, financier and Member of Parliament John Sadleir.

This is does not appear to be the same drawing-room ("the ladies' withdrawing-room") which forms the backdrop of Society expresses its Views on a Question of Marriage. The reception room, state-room, or grand salon is brilliantly lit and sumptuously furnished — and the middle-aged men who have just adjourned here from the dining-room are entirely undistinguished, unremarkable, and interchangeable, but, as Steig notes, they are at least individualised. Probably because he is so non-descript and a mere appendage of Mrs. Merdle, the other illustrators do not depict him."

The patriotic conference

Book II Chapter 12

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Mr. Merdle issued invitations for a Barnacle dinner. Lord Decimus was to be there, Mr. Tite Barnacle was to be there, the pleasant young Barnacle was to be there; and the Chorus of Parliamentary Barnacles who went about the provinces when the House was up, warbling the praises of their Chief, were to be represented there. It was understood to be a great occasion. Mr. Merdle was going to take up the Barnacles.

Bar was truly repentant, and would not say another syllable. Would Bishop favour him with half-a-dozen words? (He had now set Mr. Merdle down on a couch, side by side with Lord Decimus, and to it they must go, now or never.)

And now the rest of the company, highly excited and interested, always excepting Bishop, who had not the slightest idea that anything was going on, formed in one group round the fire in the next drawing-room, and pretended to be chatting easily on the infinite variety of small topics, while everybody's thoughts and eyes were secretly straying towards the secluded pair. The Chorus were excessively nervous, perhaps as labouring under the dreadful apprehension that some good thing was going to be diverted from them! Bishop alone talked steadily and evenly. He conversed with the great Physician on that relaxation of the throat with which young curates were too frequently afflicted, and on the means of lessening the great prevalence of that disorder in the church. Physician, as a general rule, was of opinion that the best way to avoid it was to know how to read, before you made a profession of reading. Bishop said dubiously, did he really think so? And Physician said, decidedly, yes he did."

Commentary:

Accordingly, the novelist's treatment of the "patriotic" conference for bringing Merdle and Lord Decimus Barnacle together to arrange a rich bit of patronage is very much in the traditions of political caricature, if not literary allegory. Bar, Bishop, Physician, and Chorus are representative types rather than individuals, and this is consistent with all of the Barnacle imagery. Yet, except for the Bishop's collar, there is no way of distinguishing the types in Browne's illustration, The Patriotic Conference (Bk. 2, ch. 12). If we read ahead, we find that the three men shown behind Merdle and Lord Decimus are the "Chorus," while Bishop's companion is Physician, but in earlier Dickens novels one would not have to consult the text this closely in order to understand an illustration (whereas in "Sixties" illustrations the picture usually relies heavily on the text). Phiz's men are realized as individuals, not as types. One of his problems here is that Dickens has virtually dispensed with physical description beyond Merdle's habit of taking himself into custody. Yet were Phiz to label the characters with obvious symbols of their professions, the result would seem primitive, and jar with the rest of his work in this novel.

In this instance, it is difficult to dispute the argument that Dickens no longer needs an illustrator: illustrations do not work for this particular episode because Dickens chose to make use of a highly stylized, nonrealistic technique. His private imagination is still visual, however, as can be inferred from his instruction to Browne, "Don't have Lord Decimus's hand put out, because that looks condescending; and I want him to be upright, stiff, unmixable with more mortality" — an instruction Browne followed as best he could.

The only figure whose clothing suggests his profession, as Steig notes, is the Church of England Bishop, right. Above him, one of the dinner guests, presumably a connoisseur of art, with his eyeglass studies the details in a seventeenth-century Dutch painting of cattle such as those by Cuyp and Paulus Potter: "his Lordship composed himself into the picture after Cuyp, and made a third cow in the group" gave Phiz a hint as to how the powerbrokers might be arranged, and then Phiz actually incorporated such a painting into the background. However, the man at the painting is not Lord Decimus, for Merdle and Lord Decimus are the well-dressed, middle-aged businessmen in the left foreground — and in this cameo Merdle even resembles somewhat his real-life original, financier and Member of Parliament John Sadleir.

This is does not appear to be the same drawing-room ("the ladies' withdrawing-room") which forms the backdrop of Society expresses its Views on a Question of Marriage. The reception room, state-room, or grand salon is brilliantly lit and sumptuously furnished — and the middle-aged men who have just adjourned here from the dining-room are entirely undistinguished, unremarkable, and interchangeable, but, as Steig notes, they are at least individualised. Probably because he is so non-descript and a mere appendage of Mrs. Merdle, the other illustrators do not depict him."

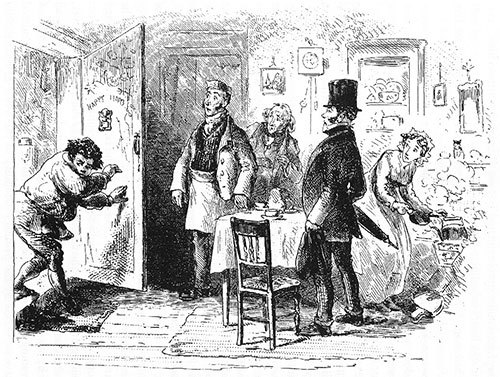

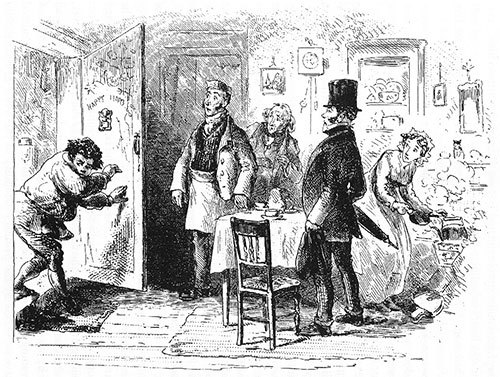

Book II Chapter 13 - Phiz

Mr. Baptist Is Supposed To Have Seen Something

Book II Chapter 13

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Nandy, re-entering the cottage with an air of mystery, entreated them to come and look at the strange behaviour of Mr. Baptist, who seemed to have met with something that had scared him. All three going into the shop, and watching through the window, then saw Mr. Baptist, pale and agitated, go through the following extraordinary performances. First, he was observed hiding at the top of the steps leading down into the Yard, and peeping up and down the street with his head cautiously thrust out close to the side of the shop-door. After very anxious scrutiny, he came out of his retreat, and went briskly down the street as if he were going away altogether; then, suddenly turned about, and went, at the same pace, and with the same feint, up the street. He had gone no further up the street than he had gone down, when he crossed the road and disappeared. The object of this last manoeuvre was only apparent, when his entering the shop with a sudden twist, from the steps again, explained that he had made a wide and obscure circuit round to the other, or Doyce and Clennam, end of the Yard, and had come through the Yard and bolted in. He was out of breath by that time, as he might well be, and his heart seemed to jerk faster than the little shop-bell, as it quivered and jingled behind him with his hasty shutting of the door.

"Hallo, old chap!" said Mr. Pancks. "Altro, old boy! What's the matter?"

Mr. Baptist, or Signor Cavalletto, understood English now almost as well as Mr. Pancks himself, and could speak it very well too. Nevertheless, Mrs. Plornish, with a pardonable vanity in that accomplishment of hers which made her all but Italian, stepped in as interpreter.

"E ask know," said Mrs. Plornish, "What go wrong?"

Commentary:

The chief illustrators of the book in the nineteenth century, Phiz and James Mahoney, have focused on very different aspects of the plot revealed in this chapter: whereas Phiz in the original serial illustration (and Harry Furniss in his derivative Mr. Baptist takes refuge in Happy Cottage) underscores Cavaletto's terror of Rigaud, who has suddenly appeared in London, Mahoney pursues the investment mania created by Merdle's promise of high rates of return on significant investment, a mania that has even swept up so cautious an investor as Panks, identified by his hat and bag here, as opposed to his spiky hair in Sol Eytinge, Junior's portrait of him and slum landlord Casby, and Harry Furniss's version of this group scene.

Having deployed a serious illustration as the first in the January 1857 number (Part Fourteen), Dickens and Phiz have elected to use a character-comedy steel-engraving as the second for that number, even though this installment explores a more important matter, the pernicious influence of Merdle's millions. In The Patriotic Conference (Book II, Chapter 12) artist and author had employed the rather lackluster Merdle social gathering to draw the reader's attention to Merdle's using his influence with the Barnacle clan to effect his step-son's promotion to a post in the governmental Circumlocution Office. Speculation fever based on the lure of high rates of return runs rampant throughout England. However, this second illustration for the fourteenth monthly number focuses instead upon the relatively jolly, lower-middle-class characters of Bleeding Heart Yard's "Happy Cottage," the tobacconist's shop run by Mrs. Plornish: Cavaletto nervously enters (left), startling the occupants; Mr. Plornish (identified by his plasterer's hat), Old Nandy (Mrs. Plornish's aged parent), Pancks with collection bag and umbrella in the foreground, and, in the process of making tea, Mrs. Plornish herself (right). The homey, lower-middle-class parlor is a sharp contrast to the sterile opulence of Mr. Merdle's salon in the previous plate, and each of these five figures is highly individualized, as opposed to the relatively undistinguished high society set of eight political and economic movers-and-shakers in the previous illustration. Once again, then, Phiz and Dickens utilize the "streaky bacon" principle of alternating the serious and comic scenes in the number's twin illustrations."

Mr. Baptist Is Supposed To Have Seen Something

Book II Chapter 13

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Nandy, re-entering the cottage with an air of mystery, entreated them to come and look at the strange behaviour of Mr. Baptist, who seemed to have met with something that had scared him. All three going into the shop, and watching through the window, then saw Mr. Baptist, pale and agitated, go through the following extraordinary performances. First, he was observed hiding at the top of the steps leading down into the Yard, and peeping up and down the street with his head cautiously thrust out close to the side of the shop-door. After very anxious scrutiny, he came out of his retreat, and went briskly down the street as if he were going away altogether; then, suddenly turned about, and went, at the same pace, and with the same feint, up the street. He had gone no further up the street than he had gone down, when he crossed the road and disappeared. The object of this last manoeuvre was only apparent, when his entering the shop with a sudden twist, from the steps again, explained that he had made a wide and obscure circuit round to the other, or Doyce and Clennam, end of the Yard, and had come through the Yard and bolted in. He was out of breath by that time, as he might well be, and his heart seemed to jerk faster than the little shop-bell, as it quivered and jingled behind him with his hasty shutting of the door.

"Hallo, old chap!" said Mr. Pancks. "Altro, old boy! What's the matter?"

Mr. Baptist, or Signor Cavalletto, understood English now almost as well as Mr. Pancks himself, and could speak it very well too. Nevertheless, Mrs. Plornish, with a pardonable vanity in that accomplishment of hers which made her all but Italian, stepped in as interpreter.

"E ask know," said Mrs. Plornish, "What go wrong?"

Commentary:

The chief illustrators of the book in the nineteenth century, Phiz and James Mahoney, have focused on very different aspects of the plot revealed in this chapter: whereas Phiz in the original serial illustration (and Harry Furniss in his derivative Mr. Baptist takes refuge in Happy Cottage) underscores Cavaletto's terror of Rigaud, who has suddenly appeared in London, Mahoney pursues the investment mania created by Merdle's promise of high rates of return on significant investment, a mania that has even swept up so cautious an investor as Panks, identified by his hat and bag here, as opposed to his spiky hair in Sol Eytinge, Junior's portrait of him and slum landlord Casby, and Harry Furniss's version of this group scene.

Having deployed a serious illustration as the first in the January 1857 number (Part Fourteen), Dickens and Phiz have elected to use a character-comedy steel-engraving as the second for that number, even though this installment explores a more important matter, the pernicious influence of Merdle's millions. In The Patriotic Conference (Book II, Chapter 12) artist and author had employed the rather lackluster Merdle social gathering to draw the reader's attention to Merdle's using his influence with the Barnacle clan to effect his step-son's promotion to a post in the governmental Circumlocution Office. Speculation fever based on the lure of high rates of return runs rampant throughout England. However, this second illustration for the fourteenth monthly number focuses instead upon the relatively jolly, lower-middle-class characters of Bleeding Heart Yard's "Happy Cottage," the tobacconist's shop run by Mrs. Plornish: Cavaletto nervously enters (left), startling the occupants; Mr. Plornish (identified by his plasterer's hat), Old Nandy (Mrs. Plornish's aged parent), Pancks with collection bag and umbrella in the foreground, and, in the process of making tea, Mrs. Plornish herself (right). The homey, lower-middle-class parlor is a sharp contrast to the sterile opulence of Mr. Merdle's salon in the previous plate, and each of these five figures is highly individualized, as opposed to the relatively undistinguished high society set of eight political and economic movers-and-shakers in the previous illustration. Once again, then, Phiz and Dickens utilize the "streaky bacon" principle of alternating the serious and comic scenes in the number's twin illustrations."

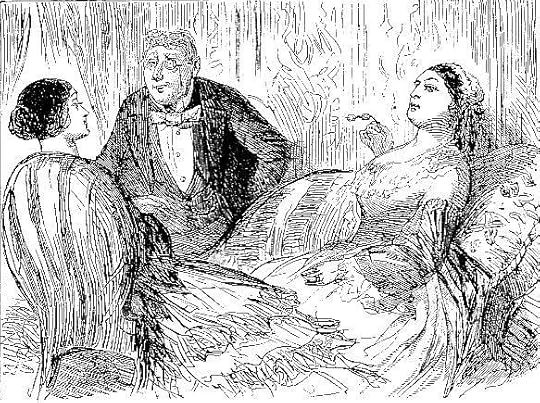

Book II Chapter 12 - Sol Eytinge Jr.

The Merdle Party

Book II Chapter 12

Sol Eytinge Jr.

The Diamond Edition of Dicken's Little Dorrit 1871

Commentary:

The Dorrits, making an upper middle class version of the Grand Tour, cross paths with Mrs. Merdle and her son by a previous marriage, Edmund Sparkler, at Martigny. Meanwhile, back in Cavendish Square, her banker-husband entertains the politically influential Barnacles to promote Edmund's interests in Book 2, Chapter 12, ""In Which a Great Patriotic Conference is Holden." The foregrounded juxtaposition of the fashionably dressed, older man with extensive shirt cuffs — undoubtedly, Mr. Merdle — seated beside a younger man in formal dress suggests that Eytinge has realised the following passage:

"Mr. Tite Barnacle, who, like Dr. Johnson's celebrated acquaintance, had only one idea in his head and that was a wrong one, had appeared by this time. This eminent gentleman and Mr. Merdle, seated diverse ways and with ruminating aspects on a yellow ottoman in the light of the fire, holding no verbal communication with each other, bore a strong general resemblance to the two cows in the Cuyp picture over against them."

The remaining six figures in the illustration are the assorted younger members of the Barnacle clan and lords of the Circumlocution Office, since the supreme Barnacle, Lord Decimus, has yet to arrive. Behind Merdle's companion is the attorney "Bar," clearly identifiable by virtue of his monocle (first introduced in Book One, Chapter 21, "Mr. Merdle's Complaint"). Whereas Dickens focuses on Merdle's inner discomfort, his feeling of being a rank stranger and utter interloper in his own drawing room, Eytinge gives us merely the placid and elegant exterior. In the absence of specific description of the financier, the American illustrator has had to improvise, giving him lean features, swept back blond hair, a double chin, and rigid posture. This pillar-like figure does not immediately suggest ineptitude or uneasiness, nor do his hands imply anxiety, but he does seem "reserved," and his head is indeed "broad, overhanging, watchful." Perhaps his skeletal thinness is intended to suggest his lack of enjoyment of expensive foodstuffs and rich meals. The emphasis on the rounded end of the ottoman in the illustration suggests that Merdle is not just seated, but enthroned.

The Merdle Party

Book II Chapter 12

Sol Eytinge Jr.

The Diamond Edition of Dicken's Little Dorrit 1871

Commentary:

The Dorrits, making an upper middle class version of the Grand Tour, cross paths with Mrs. Merdle and her son by a previous marriage, Edmund Sparkler, at Martigny. Meanwhile, back in Cavendish Square, her banker-husband entertains the politically influential Barnacles to promote Edmund's interests in Book 2, Chapter 12, ""In Which a Great Patriotic Conference is Holden." The foregrounded juxtaposition of the fashionably dressed, older man with extensive shirt cuffs — undoubtedly, Mr. Merdle — seated beside a younger man in formal dress suggests that Eytinge has realised the following passage:

"Mr. Tite Barnacle, who, like Dr. Johnson's celebrated acquaintance, had only one idea in his head and that was a wrong one, had appeared by this time. This eminent gentleman and Mr. Merdle, seated diverse ways and with ruminating aspects on a yellow ottoman in the light of the fire, holding no verbal communication with each other, bore a strong general resemblance to the two cows in the Cuyp picture over against them."

The remaining six figures in the illustration are the assorted younger members of the Barnacle clan and lords of the Circumlocution Office, since the supreme Barnacle, Lord Decimus, has yet to arrive. Behind Merdle's companion is the attorney "Bar," clearly identifiable by virtue of his monocle (first introduced in Book One, Chapter 21, "Mr. Merdle's Complaint"). Whereas Dickens focuses on Merdle's inner discomfort, his feeling of being a rank stranger and utter interloper in his own drawing room, Eytinge gives us merely the placid and elegant exterior. In the absence of specific description of the financier, the American illustrator has had to improvise, giving him lean features, swept back blond hair, a double chin, and rigid posture. This pillar-like figure does not immediately suggest ineptitude or uneasiness, nor do his hands imply anxiety, but he does seem "reserved," and his head is indeed "broad, overhanging, watchful." Perhaps his skeletal thinness is intended to suggest his lack of enjoyment of expensive foodstuffs and rich meals. The emphasis on the rounded end of the ottoman in the illustration suggests that Merdle is not just seated, but enthroned.

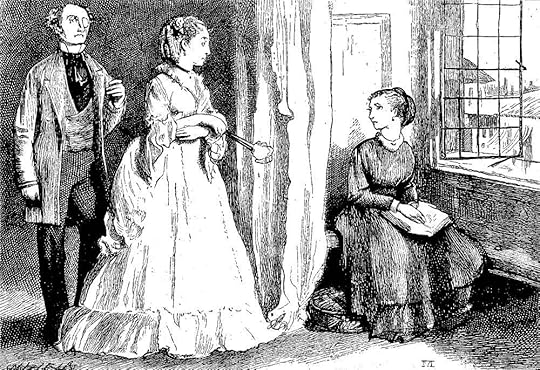

Book II Chapter 13 - Sol Eytinge Jr.

"Mr. and Mrs. Plornish and John Edward Nandy,"

Book II Chapter 13

Sol Eytinge Jr.

The Diamond Edition 1871

Commentary:

In the thirteenth character study to complement Dickens's narrative, "Mr. and Mrs. Plornish and John Edward Nandy," Eytinge does not include the Plornishes' highly painted shop-parlour masquerading as "Happy Cottage" in Bleeding Heart Yard, located in a maze of alleyways in Holborn, but focuses on the good-natured couple — Sally, the proprietress of a small grocery store funded by the suddenly-wealthy Mr. Dorrit, and her husband, Thomas, a plasterer (as one may judge from his cap) — and Mrs. Plornish's cheerful, elderly, pipe-smoking father. Eytinge conveys their bonhomie and mutual delight in each other's company, and realizes Thomas's sandy whiskers. The relevant passage is probably this:

Mrs. Plornish's shop-parlour had been decorated under her own eye, and presented, on the side towards the shop, a little fiction in which Mrs. Plornish unspeakably rejoiced. This poetical heightening of the parlour consisted in the wall being painted to represent the exterior of a thatched cottage; the artist having introduced (in as effective a manner as he found compatible with their highly disproportionate dimensions) the real door and window. The modest sunflower and hollyhock were depicted as flourishing with great luxuriance on this rustic dwelling, while a quantity of dense smoke issuing from the chimney indicated good cheer within, and also, perhaps, that it had not been lately swept. A faithful dog was represented as flying at the legs of the friendly visitor, from the threshold; and a circular pigeon-house, enveloped in a cloud of pigeons, arose from behind the garden-paling. On the door (when it was shut), appeared the semblance of a brass-plate, presenting the inscription, Happy Cottage, T. and M. Plornish; the partnership expressing man and wife. No Poetry and no Art ever charmed the imagination more than the union of the two in this counterfeit cottage charmed Mrs. Plornish. It was nothing to her that Plornish had a habit of leaning against it as he smoked his pipe after work, when his hat blotted out the pigeon-house and all the pigeons, when his back swallowed up the dwelling, when his hands in his pockets uprooted the blooming garden and laid waste the adjacent country. To Mrs. Plornish, it was still a most beautiful cottage, a most wonderful deception; and it made no difference that Mr. Plornish's eye was some inches above the level of the gable bed-room in the thatch. To come out into the shop after it was shut, and hear her father sing a song inside this cottage, was a perfect Pastoral to Mrs. Plornish, the Golden Age revived. And truly if that famous period had been revived, or had ever been at all, it may be doubted whether it would have produced many more heartily admiring daughters than the poor woman."

"Mr. and Mrs. Plornish and John Edward Nandy,"

Book II Chapter 13

Sol Eytinge Jr.

The Diamond Edition 1871

Commentary:

In the thirteenth character study to complement Dickens's narrative, "Mr. and Mrs. Plornish and John Edward Nandy," Eytinge does not include the Plornishes' highly painted shop-parlour masquerading as "Happy Cottage" in Bleeding Heart Yard, located in a maze of alleyways in Holborn, but focuses on the good-natured couple — Sally, the proprietress of a small grocery store funded by the suddenly-wealthy Mr. Dorrit, and her husband, Thomas, a plasterer (as one may judge from his cap) — and Mrs. Plornish's cheerful, elderly, pipe-smoking father. Eytinge conveys their bonhomie and mutual delight in each other's company, and realizes Thomas's sandy whiskers. The relevant passage is probably this:

Mrs. Plornish's shop-parlour had been decorated under her own eye, and presented, on the side towards the shop, a little fiction in which Mrs. Plornish unspeakably rejoiced. This poetical heightening of the parlour consisted in the wall being painted to represent the exterior of a thatched cottage; the artist having introduced (in as effective a manner as he found compatible with their highly disproportionate dimensions) the real door and window. The modest sunflower and hollyhock were depicted as flourishing with great luxuriance on this rustic dwelling, while a quantity of dense smoke issuing from the chimney indicated good cheer within, and also, perhaps, that it had not been lately swept. A faithful dog was represented as flying at the legs of the friendly visitor, from the threshold; and a circular pigeon-house, enveloped in a cloud of pigeons, arose from behind the garden-paling. On the door (when it was shut), appeared the semblance of a brass-plate, presenting the inscription, Happy Cottage, T. and M. Plornish; the partnership expressing man and wife. No Poetry and no Art ever charmed the imagination more than the union of the two in this counterfeit cottage charmed Mrs. Plornish. It was nothing to her that Plornish had a habit of leaning against it as he smoked his pipe after work, when his hat blotted out the pigeon-house and all the pigeons, when his back swallowed up the dwelling, when his hands in his pockets uprooted the blooming garden and laid waste the adjacent country. To Mrs. Plornish, it was still a most beautiful cottage, a most wonderful deception; and it made no difference that Mr. Plornish's eye was some inches above the level of the gable bed-room in the thatch. To come out into the shop after it was shut, and hear her father sing a song inside this cottage, was a perfect Pastoral to Mrs. Plornish, the Golden Age revived. And truly if that famous period had been revived, or had ever been at all, it may be doubted whether it would have produced many more heartily admiring daughters than the poor woman."

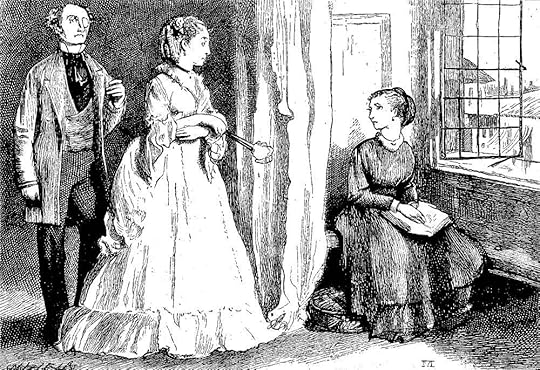

Book II Chapter 14 - Sol Eytinge Jr.

"Mrs. Merdle, Mr. Sparkler, and Fanny,"

Book II Chapter 14

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Commentary:

While Mr. Merdle entertains the Barnacle clan in London to advance his step-son's career as "one of the Lords of the Circumlocution Office", Mrs. Merdle entertains Fanny Dorrit in her apartments "on the shore of the yellow Tiber" in "Taking Advice," Chapter 14 of Book Two ("Riches"). Whereas in the text our apprehension of this translation to the upper political sphere is conditioned by the envious Henry Gowan's cutting remark "that Sparkler was the sweetest-tempered, simplest-hearted, altogether most lovable jackass that ever grazed on the public common", our assessment of his character in Eytinge's fourteenth character study is based on his youthful corpulence, fashionable evening dress, and quizzing-glass: visually, if his mother is striking a Queen Victoria like pose, then he is by extension to youthful Prince of Wales. The character whom Eytinge does not permit us to study is the rather more knowing Fanny, who has determined that she should have a husband who is not merely wealthy but lacking in intelligence so that she may dominate the relationship. Dickens notes in the twenty-first chapter of the first book that Edmund's idiocy has been accounted for by his brain supposedly having frozen during a frost in St. John's , New Brunswick, where he was born, or possibly having in infancy (in that same city where his father, Colonel Sparkler was stationed) been dropped out of window by a negligent nurse; and that ever since coming of age the "chuckle-headed high-shouldered" only child of Mrs. Merdle has been in the habit of proposing marriage "to all manner of undesirable young ladies".

Initially, Mrs. Merdle had objected to a match between her dissolute son and the daughter of an insolvent debtor (indeed, in chapter 20 of the first book she had actually bribed the young dancer to discourage her son's attentions), but in the next chapter withdraws her objection since the Dorrit family has come into a fortune. Fanny treats her imbecilic husband with contempt, despite his elevated post in the Circumlocution Office. The passage reflected rather than absolutely realized in Eytinge's fourteenth illustration is likely this:

"Amy observed Mr. Sparkler's treatment by his enslaver, with new reasons for attaching importance to all that passed between them. There were times when Fanny appeared quite unable to endure his mental feebleness, and when she became so sharply impatient of it that she would all but dismiss him for good. There were other times when she got on much better with him; when he amused her, and when her sense of superiority seemed to counterbalance that opposite side of the scale. If Mr. Sparkler had been other than the faithfulest and most submissive of swains, he was sufficiently hard pressed to have fled from the scene of his trials, and have set at least the whole distance from Rome to London between himself and his enchantress. But he had no greater will of his own than a boat has when it is towed by a steam-ship; and he followed his cruel mistress through rough and smooth, on equally strong compulsion.

Mrs. Merdle, during these passages, said little to Fanny, but said more about her. She was, as it were, forced to look at her through her eye-glass, and in general conversation to allow commendations of her beauty to be wrung from her by its irresistible demands. The defiant character it assumed when Fanny heard these extolling's (as it generally happened that she did), was not expressive of concessions to the impartial bosom; but the utmost revenge the bosom took was, to say audibly, "A spoilt beauty — but with that face and shape, who could wonder?"

The drawing-room scene, then, is one which Eytinge has imagined as having transpired when — off stage, so to speak — Mrs. Merdle had agreed to the union and Edmund had started to think of Amy Dorrit as a sister. Eytinge gives us Mrs. Merdle's ample bosom and eye-glass from the text, but must invent the rest.

"Mrs. Merdle, Mr. Sparkler, and Fanny,"

Book II Chapter 14

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Commentary:

While Mr. Merdle entertains the Barnacle clan in London to advance his step-son's career as "one of the Lords of the Circumlocution Office", Mrs. Merdle entertains Fanny Dorrit in her apartments "on the shore of the yellow Tiber" in "Taking Advice," Chapter 14 of Book Two ("Riches"). Whereas in the text our apprehension of this translation to the upper political sphere is conditioned by the envious Henry Gowan's cutting remark "that Sparkler was the sweetest-tempered, simplest-hearted, altogether most lovable jackass that ever grazed on the public common", our assessment of his character in Eytinge's fourteenth character study is based on his youthful corpulence, fashionable evening dress, and quizzing-glass: visually, if his mother is striking a Queen Victoria like pose, then he is by extension to youthful Prince of Wales. The character whom Eytinge does not permit us to study is the rather more knowing Fanny, who has determined that she should have a husband who is not merely wealthy but lacking in intelligence so that she may dominate the relationship. Dickens notes in the twenty-first chapter of the first book that Edmund's idiocy has been accounted for by his brain supposedly having frozen during a frost in St. John's , New Brunswick, where he was born, or possibly having in infancy (in that same city where his father, Colonel Sparkler was stationed) been dropped out of window by a negligent nurse; and that ever since coming of age the "chuckle-headed high-shouldered" only child of Mrs. Merdle has been in the habit of proposing marriage "to all manner of undesirable young ladies".

Initially, Mrs. Merdle had objected to a match between her dissolute son and the daughter of an insolvent debtor (indeed, in chapter 20 of the first book she had actually bribed the young dancer to discourage her son's attentions), but in the next chapter withdraws her objection since the Dorrit family has come into a fortune. Fanny treats her imbecilic husband with contempt, despite his elevated post in the Circumlocution Office. The passage reflected rather than absolutely realized in Eytinge's fourteenth illustration is likely this:

"Amy observed Mr. Sparkler's treatment by his enslaver, with new reasons for attaching importance to all that passed between them. There were times when Fanny appeared quite unable to endure his mental feebleness, and when she became so sharply impatient of it that she would all but dismiss him for good. There were other times when she got on much better with him; when he amused her, and when her sense of superiority seemed to counterbalance that opposite side of the scale. If Mr. Sparkler had been other than the faithfulest and most submissive of swains, he was sufficiently hard pressed to have fled from the scene of his trials, and have set at least the whole distance from Rome to London between himself and his enchantress. But he had no greater will of his own than a boat has when it is towed by a steam-ship; and he followed his cruel mistress through rough and smooth, on equally strong compulsion.

Mrs. Merdle, during these passages, said little to Fanny, but said more about her. She was, as it were, forced to look at her through her eye-glass, and in general conversation to allow commendations of her beauty to be wrung from her by its irresistible demands. The defiant character it assumed when Fanny heard these extolling's (as it generally happened that she did), was not expressive of concessions to the impartial bosom; but the utmost revenge the bosom took was, to say audibly, "A spoilt beauty — but with that face and shape, who could wonder?"

The drawing-room scene, then, is one which Eytinge has imagined as having transpired when — off stage, so to speak — Mrs. Merdle had agreed to the union and Edmund had started to think of Amy Dorrit as a sister. Eytinge gives us Mrs. Merdle's ample bosom and eye-glass from the text, but must invent the rest.

Book II Chapter 13 - Harry Furniss - I thought this was a Phiz illustration when I first saw it.

Mr. Baptist takes refuge in Happy Cottage

Book II Chapter 13

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

"Padrona, dearest," returned the little foreigner whom she so considerately protected, "do not ask, I pray. Once again I say it matters not. I have fear of this man. I do not wish to see him, I do not wish to be known of him — never again! Enough, most beautiful. Leave it."

The topic was so disagreeable to him, and so put his usual liveliness to the rout, that Mrs. Plornish forbore to press him further: the rather as the tea had been drawing for some time on the hob. But she was not the less surprised and curious for asking no more questions; neither was Mr. Pancks, whose expressive breathing had been labouring hard since the entrance of the little man, like a locomotive engine with a great load getting up a steep incline. Maggy, now better dressed than of yore, though still faithful to the monstrous character of her cap, had been in the background from the first with open mouth and eyes, which staring and gaping features were not diminished in breadth by the untimely suppression of the subject. However, no more was said about it, though much appeared to be thought on all sides: by no means excepting the two young Plornishes, who partook of the evening meal as if their eating the bread and butter were rendered almost superfluous by the painful probability of the worst of men shortly presenting himself for the purpose of eating them. Mr. Baptist, by degrees began to chirp a little; but never stirred from the seat he had taken behind the door and close to the window, though it was not his usual place. As often as the little bell rang, he started and peeped out secretly, with the end of the little curtain in his hand and the rest before his face; evidently not at all satisfied but that the man he dreaded had tracked him through all his doublings and turnings, with the certainty of a terrible bloodhound."

Commentary:

Whereas the original Phiz version, Mr. Baptist is Supposed to have seen Something, contains Pancks, the Plornishes, Old Nandy, and Cavaletto, Furniss has added the boy and girl eating bread-and-butter, and Maggy, recognizable immediately by her over-sized hat. The effect of a static group portrait is disrupted by the very different postures of the eight characters, with the strangely dressed Cavaletto turned to look out of the window, Maggy and Old Nandy seated, the Plornishes standing on the other side of the dining-table, and Pancks (also immediately recognizable by a single feature, his spiked hair) standing with his back to the fire.

The two chief illustrators of Dickens's novel in the nineteenth century, Phiz and James Mahoney, have focused on very different aspects of the plot revealed in this chapter: whereas Phiz in the original serial illustration (and Harry Furniss in his derivative Mr. Baptist takes refuge in Happy Cottage) underscores Cavaletto's terror of Rigaud, who has suddenly appeared in London, Mahoney pursues the investment mania created by Merdle's promise of high rates of return on significant investment, a mania that has even swept up so cautious an investor as Panks, identified by his hat and bag here, as opposed to his spiky hair in Sol Eytinge, Junior's portrait of him and slum landlord Casby, and Harry Furniss's version of this group scene. Furniss follows Phiz's lead in his choice of subject, preferring the character comedy of the parlor scene.

Mr. Baptist takes refuge in Happy Cottage

Book II Chapter 13

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

"Padrona, dearest," returned the little foreigner whom she so considerately protected, "do not ask, I pray. Once again I say it matters not. I have fear of this man. I do not wish to see him, I do not wish to be known of him — never again! Enough, most beautiful. Leave it."