The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit, Book 2, Chp. 19-22

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 20 is titled "Introduces the next" and Arthur has arrived in Calais looking for Miss Wade and through her hopefully, Blandois. Pancks had gotten the address of Miss Wade from the loose papers in Mr. Casby's house, but when he first sees the house he is surprised that she should be found in such a rundown place. It is described as a dead sort of house with a dead wall and a dead gateway, and a bell handle that produces two dead tinkles. More and more gloom. Miss Wade is here though and she does agree to see him when he gives his name as "Monsieur Blandois". She is surprised to see him and he tells her he used the false name because he didn't think she would see him if she knew who it was. He then tells her he wants information on Blandois, a person he knows she has met, and goes on to tell her about the time he had seen her and Blandois meeting in the street. After reflecting she agrees that the meeting was out in the open and could have been seen by him, but still doesn't know what he could now want with her.

He tells her he is interested in finding Blandois who has disappeared and his mother is suspected of having something to do with it. Miss Wade says she knows nothing of the matter. She tells him he should go ask his friend Henry Gowan about the matter and goes on to say that she hates his wife. She also hates Gowan even more because she had once loved him. I think this is very strange that a woman who never says a word about herself to anyone would all of a sudden tell Arthur, a man she barely knows, that she was in love with Gowan. Not only that, but she has written it all down for him to read and gives it to him. Why would she write it all down for Arthur? They barely know each other, or am I forgetting something between them. Of course I'd be surprised at her giving a document of her past life to anyone And I guess it shouldn't surprise me she gave it to Arthur, he seems to be in the middle of everyone's lives, I'm not sure what they ever did without him. But he takes it and is about to leave when Tattycoram comes into the room, Tatty asks if "they" are well and admits she had been down to look at the house when Miss Wade wasn't home. Miss Wade becomes angry and tells her to return to them but Tattycoram says she never could. And so another dismal chapter ends with this:

He came down the dark winding stairs into the yard with an increased sense upon him of the gloom of the wall that was dead, and of the shrubs that were dead, and of the fountain that was dry, and of the statue that was gone. Pondering much on what he had seen and heard in that house, as well as on the failure of all his efforts to trace the suspicious character who was lost, he returned to London and to England by the packet that had taken him over. On the way he unfolded the sheets of paper, and read in them what is reproduced in the next chapter.

He tells her he is interested in finding Blandois who has disappeared and his mother is suspected of having something to do with it. Miss Wade says she knows nothing of the matter. She tells him he should go ask his friend Henry Gowan about the matter and goes on to say that she hates his wife. She also hates Gowan even more because she had once loved him. I think this is very strange that a woman who never says a word about herself to anyone would all of a sudden tell Arthur, a man she barely knows, that she was in love with Gowan. Not only that, but she has written it all down for him to read and gives it to him. Why would she write it all down for Arthur? They barely know each other, or am I forgetting something between them. Of course I'd be surprised at her giving a document of her past life to anyone And I guess it shouldn't surprise me she gave it to Arthur, he seems to be in the middle of everyone's lives, I'm not sure what they ever did without him. But he takes it and is about to leave when Tattycoram comes into the room, Tatty asks if "they" are well and admits she had been down to look at the house when Miss Wade wasn't home. Miss Wade becomes angry and tells her to return to them but Tattycoram says she never could. And so another dismal chapter ends with this:

He came down the dark winding stairs into the yard with an increased sense upon him of the gloom of the wall that was dead, and of the shrubs that were dead, and of the fountain that was dry, and of the statue that was gone. Pondering much on what he had seen and heard in that house, as well as on the failure of all his efforts to trace the suspicious character who was lost, he returned to London and to England by the packet that had taken him over. On the way he unfolded the sheets of paper, and read in them what is reproduced in the next chapter.

Chapter 21 is titled The History of a Self-Tormentor which is an excellent name for this chapter. The entire chapter is the letter - or whatever it is - that Miss Wade has given to Arthur. It appears that whenever anyone was nice to her she felt they were looking down on her. She says that if she had been a fool and believed people were really being kind she would have had a happier life, but she knows they were all patronizing her. As a child she had lived with a woman who claimed to be her grandmother. There were nine other girls who lived there but Miss Wade was the only orphan. Frustrated at how everyone pitied her and how superior they felt toward her, she often picked fights with them. When she succeeded she was angry that they were quick to make up with her.

It goes on and on, she had one friend as a child, but she was angry because the girl was nice to everyone, saying she knows the girl did it to hurt her. When she overheard the girl tell her aunt that all the girls try to be nice to her, Miss Wade insists on leaving and tells her grandmother to send her away before her friend returns to their home. No matter where she went the same thing would happen, if anyone was nice to her she thought they were triumphing over her and made a pretense of treating her kindly. Becoming a governess she insists on leaving because the children's nurse is kind to her and tries to get the children to love her. Wisely the children seem to want nothing to do with her. When she tells the mother of the children she wants to leave this is part of the conversation:

'Miss Wade, I fear you are unhappy, through causes over which I have no influence.'

I smiled, thinking of the experience the word awakened, and said, 'I have an unhappy temper, I suppose.'

'I did not say that.'

'It is an easy way of accounting for anything,' said I.

'It may be; but I did not say so. What I wish to approach is something very different. My husband and I have exchanged some remarks upon the subject, when we have observed with pain that you have not been easy with us.'

'Easy? Oh! You are such great people, my lady,' said I.

'I am unfortunate in using a word which may convey a meaning—and evidently does—quite opposite to my intention.' (She had not expected my reply, and it shamed her.) 'I only mean, not happy with us. It is a difficult topic to enter on; but, from one young woman to another, perhaps—in short, we have been apprehensive that you may allow some family circumstances of which no one can be more innocent than yourself, to prey upon your spirits. If so, let us entreat you not to make them a cause of grief. My husband himself, as is well known, formerly had a very dear sister who was not in law his sister, but who was universally beloved and respected—'

I saw directly that they had taken me in for the sake of the dead woman, whoever she was, and to have that boast of me and advantage of me; I saw, in the nurse's knowledge of it, an encouragement to goad me as she had done; and I saw, in the children's shrinking away, a vague impression, that I was not like other people. I left that house that night.

Eventually she becomes engaged, how she managed this is beyond me, but asks her fiancé not to show affection to her because she knew that the rich people he knew thought he was only marrying her for her looks. When he finally agrees and in front of company sits with his cousin she is furious - even though she is the one that didn't want his attention. During all this she meets Henry Gowan. Henry is the first person who understood her, he must be quite the guy if he can understand her, I wish he could explain her to me. Very shortly she tells us, Henry occupied every thought she has. He was always pleasant, everyone was his friend, but she knew he was just pretending. Whether he was or not I don't know. Eventually, everyone noticed the way she was acting and finally her Mistress decided to speak to her about it. That didn't go well:

It would probably have come, sooner or later, to the end to which it did come, but she brought it to its issue at once. She told me, with assumed commiseration, that I had an unhappy temper. On this repetition of the old wicked injury, I withheld no longer, but exposed to her all I had known of her and seen in her, and all I had undergone within myself since I had occupied the despicable position of being engaged to her nephew. I told her that Mr Gowan was the only relief I had had in my degradation; that I had borne it too long, and that I shook it off too late; but that I would see none of them more. And I never did.

For a while she is happy in her retreat where Henry follows her, but eventually he tells her that it is time they part, they are both people of the world, and were prepared to go their way to make their fortunes, she didn't contradict him and he left. Shortly after that he was courting Pet and now we all know why she hates them both. Why she decided to share the awful story of her life to Arthur I don't know. Why, I wonder is she like this? What part of her childhood made her so filled with hate? And hate not just for a few people but for the world as far as I can tell. I also wonder what her reasons are for taking Tatty, she says it is because her circumstances were similar to her own, but is it? Does she really want Tatty to end up as unhappy as she is? I don't know. I understand her a little better now, that's something I guess.

It goes on and on, she had one friend as a child, but she was angry because the girl was nice to everyone, saying she knows the girl did it to hurt her. When she overheard the girl tell her aunt that all the girls try to be nice to her, Miss Wade insists on leaving and tells her grandmother to send her away before her friend returns to their home. No matter where she went the same thing would happen, if anyone was nice to her she thought they were triumphing over her and made a pretense of treating her kindly. Becoming a governess she insists on leaving because the children's nurse is kind to her and tries to get the children to love her. Wisely the children seem to want nothing to do with her. When she tells the mother of the children she wants to leave this is part of the conversation:

'Miss Wade, I fear you are unhappy, through causes over which I have no influence.'

I smiled, thinking of the experience the word awakened, and said, 'I have an unhappy temper, I suppose.'

'I did not say that.'

'It is an easy way of accounting for anything,' said I.

'It may be; but I did not say so. What I wish to approach is something very different. My husband and I have exchanged some remarks upon the subject, when we have observed with pain that you have not been easy with us.'

'Easy? Oh! You are such great people, my lady,' said I.

'I am unfortunate in using a word which may convey a meaning—and evidently does—quite opposite to my intention.' (She had not expected my reply, and it shamed her.) 'I only mean, not happy with us. It is a difficult topic to enter on; but, from one young woman to another, perhaps—in short, we have been apprehensive that you may allow some family circumstances of which no one can be more innocent than yourself, to prey upon your spirits. If so, let us entreat you not to make them a cause of grief. My husband himself, as is well known, formerly had a very dear sister who was not in law his sister, but who was universally beloved and respected—'

I saw directly that they had taken me in for the sake of the dead woman, whoever she was, and to have that boast of me and advantage of me; I saw, in the nurse's knowledge of it, an encouragement to goad me as she had done; and I saw, in the children's shrinking away, a vague impression, that I was not like other people. I left that house that night.

Eventually she becomes engaged, how she managed this is beyond me, but asks her fiancé not to show affection to her because she knew that the rich people he knew thought he was only marrying her for her looks. When he finally agrees and in front of company sits with his cousin she is furious - even though she is the one that didn't want his attention. During all this she meets Henry Gowan. Henry is the first person who understood her, he must be quite the guy if he can understand her, I wish he could explain her to me. Very shortly she tells us, Henry occupied every thought she has. He was always pleasant, everyone was his friend, but she knew he was just pretending. Whether he was or not I don't know. Eventually, everyone noticed the way she was acting and finally her Mistress decided to speak to her about it. That didn't go well:

It would probably have come, sooner or later, to the end to which it did come, but she brought it to its issue at once. She told me, with assumed commiseration, that I had an unhappy temper. On this repetition of the old wicked injury, I withheld no longer, but exposed to her all I had known of her and seen in her, and all I had undergone within myself since I had occupied the despicable position of being engaged to her nephew. I told her that Mr Gowan was the only relief I had had in my degradation; that I had borne it too long, and that I shook it off too late; but that I would see none of them more. And I never did.

For a while she is happy in her retreat where Henry follows her, but eventually he tells her that it is time they part, they are both people of the world, and were prepared to go their way to make their fortunes, she didn't contradict him and he left. Shortly after that he was courting Pet and now we all know why she hates them both. Why she decided to share the awful story of her life to Arthur I don't know. Why, I wonder is she like this? What part of her childhood made her so filled with hate? And hate not just for a few people but for the world as far as I can tell. I also wonder what her reasons are for taking Tatty, she says it is because her circumstances were similar to her own, but is it? Does she really want Tatty to end up as unhappy as she is? I don't know. I understand her a little better now, that's something I guess.

The last chapter in this installment is titled "Who passes by this Road so late?" and Arthur has returned to London and Daniel Doyce is getting ready to leave. He has been hired by a "barbaric power". Our narrator tells us this:

This Power, being a barbaric one, had no idea of stowing away a great national object in a Circumlocution Office, as strong wine is hidden from the light in a cellar until its fire and youth are gone, and the labourers who worked in the vineyard and pressed the grapes are dust. With characteristic ignorance, it acted on the most decided and energetic notions of How to do it; and never showed the least respect for, or gave any quarter to, the great political science, How not to do it. Indeed it had a barbarous way of striking the latter art and mystery dead, in the person of any enlightened subject who practiced it.

Accordingly, the men who were wanted were sought out and found; which was in itself a most uncivilised and irregular way of proceeding. Being found, they were treated with great confidence and honor (which again showed dense political ignorance), and were invited to come at once and do what they had to do. In short, they were regarded as men who meant to do it, engaging with other men who meant it to be done.

They have no idea how long he will be gone, it could be months or even years. Daniel leaves the business in Clennam’s hands, he is fully confident in Arthur's abilities saying it will ease his mind knowing Arthur is there. He asks Arthur to abandon his invention, but Arthur refuses. He is confident he can get something from the Circumlocution Office saying he will not quit until he gets a real answer from those people and that it can do him no harm to try. Doyce is equally certain it may harm him, it has aged, tired, vexed and disappointed him. Still Arthur refuses.

Arthur is standing in his office singing a song when Mr. Baptist joins in:

'Who passes by this road so late?

Compagnon de la Majolaine;

Who passes by this road so late?

Always gay!'

'Of all the king's knights 'tis the flower,

Compagnon de la Majolaine;

Of all the king's knights 'tis the flower,

Always gay!'

The last time Arthur heard it, it was sung by Blandois—though he did not know him by that name. Mr. Baptist tells Arthur he knows the man from Marseilles. Blandois was a prisoner there, being convicted of murder. Mr. Baptist says he had been in Marseilles for contraband trading and Blandois had been in the same cell. Blandois was supposed to have been executed, but Baptist was released first and later sees Blandois. He worries that the man will find him again. If he has disappeared, Mr. Baptist is glad and gives a thousand thanks to heaven.

Arthur, though, can know no peace until Blandois is found and asks Baptist to find him. The chapter ends with this:

'I know it. If you could find this man, or discover what has become of him, or gain any later intelligence whatever of him, you would render me a service above any other service I could receive in the world, and would make me (with far greater reason) as grateful to you as you are to me.'

'I know not where to look,' cried the little man, kissing Arthur's hand in a transport. 'I know not where to begin. I know not where to go. But, courage! Enough! It matters not! I go, in this instant of time!'

'Not a word to any one but me, Cavalletto.'

'Al-tro!' cried Cavalletto. And was gone with great speed."

This Power, being a barbaric one, had no idea of stowing away a great national object in a Circumlocution Office, as strong wine is hidden from the light in a cellar until its fire and youth are gone, and the labourers who worked in the vineyard and pressed the grapes are dust. With characteristic ignorance, it acted on the most decided and energetic notions of How to do it; and never showed the least respect for, or gave any quarter to, the great political science, How not to do it. Indeed it had a barbarous way of striking the latter art and mystery dead, in the person of any enlightened subject who practiced it.

Accordingly, the men who were wanted were sought out and found; which was in itself a most uncivilised and irregular way of proceeding. Being found, they were treated with great confidence and honor (which again showed dense political ignorance), and were invited to come at once and do what they had to do. In short, they were regarded as men who meant to do it, engaging with other men who meant it to be done.

They have no idea how long he will be gone, it could be months or even years. Daniel leaves the business in Clennam’s hands, he is fully confident in Arthur's abilities saying it will ease his mind knowing Arthur is there. He asks Arthur to abandon his invention, but Arthur refuses. He is confident he can get something from the Circumlocution Office saying he will not quit until he gets a real answer from those people and that it can do him no harm to try. Doyce is equally certain it may harm him, it has aged, tired, vexed and disappointed him. Still Arthur refuses.

Arthur is standing in his office singing a song when Mr. Baptist joins in:

'Who passes by this road so late?

Compagnon de la Majolaine;

Who passes by this road so late?

Always gay!'

'Of all the king's knights 'tis the flower,

Compagnon de la Majolaine;

Of all the king's knights 'tis the flower,

Always gay!'

The last time Arthur heard it, it was sung by Blandois—though he did not know him by that name. Mr. Baptist tells Arthur he knows the man from Marseilles. Blandois was a prisoner there, being convicted of murder. Mr. Baptist says he had been in Marseilles for contraband trading and Blandois had been in the same cell. Blandois was supposed to have been executed, but Baptist was released first and later sees Blandois. He worries that the man will find him again. If he has disappeared, Mr. Baptist is glad and gives a thousand thanks to heaven.

Arthur, though, can know no peace until Blandois is found and asks Baptist to find him. The chapter ends with this:

'I know it. If you could find this man, or discover what has become of him, or gain any later intelligence whatever of him, you would render me a service above any other service I could receive in the world, and would make me (with far greater reason) as grateful to you as you are to me.'

'I know not where to look,' cried the little man, kissing Arthur's hand in a transport. 'I know not where to begin. I know not where to go. But, courage! Enough! It matters not! I go, in this instant of time!'

'Not a word to any one but me, Cavalletto.'

'Al-tro!' cried Cavalletto. And was gone with great speed."

Kim wrote: "This week begins with Chapter 19 titled "A Storming Of The Castle In The Air" and Mr. Dorrit's castle begins to collapse, for him and his brother it is a total collapse, for the rest of the family ..."

This is a very bizarre chapter. Castles to the coffin. I really can’t make much sense of Dickens’s methodology in this chapter. I get that Dorrit has not been able to escape from his past. I get that we all erect moats and walls and defences in order to preserve, protect or bury events in our past. What I don’t get is Dickens’s methodology and logic of how he presented the brothers’ deaths.

This is a very bizarre chapter. Castles to the coffin. I really can’t make much sense of Dickens’s methodology in this chapter. I get that Dorrit has not been able to escape from his past. I get that we all erect moats and walls and defences in order to preserve, protect or bury events in our past. What I don’t get is Dickens’s methodology and logic of how he presented the brothers’ deaths.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 20 is titled "Introduces the next" and Arthur has arrived in Calais looking for Miss Wade and through her hopefully, Blandois. Pancks had gotten the address of Miss Wade from the loose pape..."

Kim

I agree with you. The transition of Miss Wade from a woman of anger mixed with mystery to a person who makes revealing comments about her personal life seems discordant. Now both Miss Wade in this chapter and Mr Dorrit in the previous chapter are both people who have tried to bury their pasts. Both have been ultimately unsuccessful.

The re-emergence of one’s past and the revelation of how these pasts explain the person's present character is interesting but, to me, ultimately unsatisfying. This novel was planned in detail so I doubt if Dickens found himself backed into a corner by the plot. But, why, oh why, do I feel so uncomfortable with the direction of these late chapters?

Kim

I agree with you. The transition of Miss Wade from a woman of anger mixed with mystery to a person who makes revealing comments about her personal life seems discordant. Now both Miss Wade in this chapter and Mr Dorrit in the previous chapter are both people who have tried to bury their pasts. Both have been ultimately unsuccessful.

The re-emergence of one’s past and the revelation of how these pasts explain the person's present character is interesting but, to me, ultimately unsatisfying. This novel was planned in detail so I doubt if Dickens found himself backed into a corner by the plot. But, why, oh why, do I feel so uncomfortable with the direction of these late chapters?

Peter wrote: "But, why, oh why, do I feel so uncomfortable with the direction of these late chapters? ..."

Peter wrote: "But, why, oh why, do I feel so uncomfortable with the direction of these late chapters? ..."For me, it seems as if we're rushing to the end, and Dickens is trying to wrap things up more hastily than is in pace with the earlier parts of the book. Dorrit's paranoia has quickly turned to delusions, and I'm not sure how these psychological conditions have resulted in such a rapid physical decline (though I'd be lying if I said it bothered me). Same with Frederick -- we were always told that perhaps he wasn't robust, but I never was given the impression that he was at Death's door. In his case, I suppose we're meant to think that his grief pushed him over the edge. There's no accounting for brotherly love.

I thank God that William never married Mrs. General. It would be a much different book had that taken place.

Miss Wade. Kim - you summed up my thoughts exactly. Why? Why confide in Arthur? They've met, what? A total of four, maybe five times? She owes him nothing. I guess he's just one of those people everyone feels comfortable talking to. But it's very out of character for her, I think. I don't know what a shrink would make of her, but she's definitely got a persecution complex. Everyone is out to get her. The perpetual victim, determined to be bitter and unhappy. What a waste. It really angers me that she's trying to drag Harriet down with her, and I'm glad that Harriet is showing a bit of independence and spunk. In light of these new insights, I wonder if anyone has softened on the subject of the Meagles, or if I'm still all alone in being fond of them. They aren't perfect, but even Harriet seems to realized that maybe they weren't so awful.

When my kids were little we had a nice family across the street with a boy around their ages. I always encouraged them to play with him. They instinctively knew better and resisted my attempts. He ended up a drug addict who died under mysterious circumstances in his 20s. I think Miss Wade's charges also had those instincts. Kids (and dogs, in my experience) may not be able to verbalize that creepy feeling they get from some people, but we should trust it.

Leave it to Dickens to kill off the Dorrit brothers and then leave us hanging when it comes to Amy and her siblings. I'm sure we'll return to them next week. I'm betting Amy will take the first boat back to England. Will she move in with the Sparklers and the Merdles?

Thanks for pointing out that Mrs. Clennam was somehow implicated in the disappearance of Blandois. I completely missed that, and thought Arthur was just borrowing trouble by trying to track him down, but that would explain his reasoning. Still -- who would have even reported him missing? I feel like I must have missed a few pages along the way. (Insert puzzled emoji face here.)

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "But, why, oh why, do I feel so uncomfortable with the direction of these late chapters? ..."

For me, it seems as if we're rushing to the end, and Dickens is trying to wrap things up ..."

Mary Lou

I have no problem with Meagles. Sure he has mismanaged some aspects of his home life and his treatment of Tattycoram is awkward, but he is not a mean-spirited individual.

I wonder how he will ultimately react to the treatment of Pet?

For me, it seems as if we're rushing to the end, and Dickens is trying to wrap things up ..."

Mary Lou

I have no problem with Meagles. Sure he has mismanaged some aspects of his home life and his treatment of Tattycoram is awkward, but he is not a mean-spirited individual.

I wonder how he will ultimately react to the treatment of Pet?

While I don't particularly like the Meagles, and I think they did some things that probably have really screwed both Harriet and Minipet over, I don't particularly dislike them either. They were people of their time, thinking they did the right thing. I can totally imagine Harried being tired of their condescending ways, but I can also imagine she realises they at least meant well and were not bitter, as well as giving her some sort of future, in contrast to miss Wade who can hardly keep her bitter head above water level herself.

I was thinking, as we are left hanging with the Dorrit siblings ... That William inherited that estate and didn't even realise, probably meant it was entailed. Just like how in Downton Abbey the estate must go to a male heir, so suddenly it went to the cousin thrice removed on the left screwed side or whatever, instead of the daughters. That would probably also mean that all of the money would go to the gambling, almost non-existent Tip instead of Fanny and/or Amy. And suddenly I understand a bit better why William wanted them to be married - not only to get rid of them, but to make sure they could rely on their husbands' fortunes ...

I was thinking, as we are left hanging with the Dorrit siblings ... That William inherited that estate and didn't even realise, probably meant it was entailed. Just like how in Downton Abbey the estate must go to a male heir, so suddenly it went to the cousin thrice removed on the left screwed side or whatever, instead of the daughters. That would probably also mean that all of the money would go to the gambling, almost non-existent Tip instead of Fanny and/or Amy. And suddenly I understand a bit better why William wanted them to be married - not only to get rid of them, but to make sure they could rely on their husbands' fortunes ...

I never understood the Meagles. They come across as good sorts, but they fail as parents and guardians by refusing to take anything more than a superficial interest in their children -- a kind of good-natured, willful disregard. It's as if Dickens is saying there are people in this world, good-hearted individuals, who wreak havoc with their clueless good-heartedness.

I never understood the Meagles. They come across as good sorts, but they fail as parents and guardians by refusing to take anything more than a superficial interest in their children -- a kind of good-natured, willful disregard. It's as if Dickens is saying there are people in this world, good-hearted individuals, who wreak havoc with their clueless good-heartedness. Neither Tatty nor Pet are prepared for the real world for similar yet opposite reasons. Both are pets, a pet daughter and a pet companion. But Pet is spoiled beyond all measure, while Tatty is used beyond all measure. There were women in this time period who were hired as companions, but they were adults not children. It takes clueless parents not to see how destructive disparate treatment of children is, and it's hard to like the Meagles because of it.

Which brings me to this. It strikes me that Victorian novels do not spend a lot of time on loving relationships between parent and child. Dickens certainly didn't Can you think of any? There are exceptions. The woman hired by Dombey to nurse and raise his son -- sorry don't recall her name -- loved her children. But she is a minor character.

I'm trying to think through Dickens' novels.

Bleak House, forget it.

Little Dorrit, likewise.

Oliver Twist, give me a break.

Nicholas Nickelbye, meh!

Our Mutual Friend, nada!

Hard Times, hmmm . . . maybe.

Old Curiosity Shop, grandpa loved Nell to death, but there is Nell's friend and his relationship with his mother. Excellent.

David Copperfield, haven't read it.

Great Expectations, No way!!!! Havisham and Estella -- WhewHoo

Dombey and Sons -- A special place in Hell is reserved for Dombey for his treatment of his daughter.

Barnaby Rudge, didn't read it.

Xan

Interesting insight. I would add Mr Micawber from DC. He is portrayed as a feckless father figure and yet he turns out to be successful after he arrives in Australia. Still, what a role model for his children.

Interesting insight. I would add Mr Micawber from DC. He is portrayed as a feckless father figure and yet he turns out to be successful after he arrives in Australia. Still, what a role model for his children.

Xan - first, read David Copperfield! Barnaby Ridge, too, but Copperfield is the more essential of the two.

Xan - first, read David Copperfield! Barnaby Ridge, too, but Copperfield is the more essential of the two. Interesting look at parenting. I'd say the Cratchits were good parents. And there were good parents whose children went astray, like Mrs. Rouncewell in Bleak House. And also good foster parents, like Mrs. - what was it? Higden? From Our Mutual Friend. Also from OMF was Rumpty Wilfer - a good father who just chose, perhaps, the wrong mother for his kids.

The problem with parenting is that despite our best efforts and intentions, we can never be perfect. I think even Mrs. Clennam and William Dorrit may be doing their best, but they're products of their own upbringings, circumstances, and personalities. I think I was a reasonably good parent, as were my own mom and dad, but mistakes are always made -- out of love, fear, ignorance... That's what keeps therapists in business. ;-)

Cratchits were good. Don't remember Rouncewell or Higden for some reason. We know Wilfer was a good father because of his daughter's love for him -- like her character too -- a very touching scene when she takes him to lunch and gives him money. But, like Mr. Jellyby, by the time of the story he's no longer the father he once was. He reminds me of Mr. Jellyby.

Cratchits were good. Don't remember Rouncewell or Higden for some reason. We know Wilfer was a good father because of his daughter's love for him -- like her character too -- a very touching scene when she takes him to lunch and gives him money. But, like Mr. Jellyby, by the time of the story he's no longer the father he once was. He reminds me of Mr. Jellyby. Disagree about Mrs. Clenham and Mr. Dorrit. I place her in the Havisham camp and I''m not sure what camp to place him in. I see no redeeming value in her as a parent -- she is a religious hypocrite -- and he's a sad, sad mess. I have loads of sympathy and empathy for Mr. Dorrit, the person, but none for Mr. Dorrit, the parent. Whatever good father he might have been, he wasn't. What he did do was turn Amy into his servant and mommy and neglect the other two.

I think Dickens is projecting his own experiences onto his characters.

Book II Chapter 19 - Phiz

An Unexpected After-Dinner Speech

Book II Chapter 19

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The Father of the Marshalsea, now the wealthy William Dorrit, traveller through the Alps] looked confusedly about him, and, becoming conscious of the number of faces by which he was surrounded, addressed them:

"Ladies and gentlemen, the duty — ha — devolves upon me of — hum — welcoming you to the Marshalsea! Welcome to the Marshalsea! The space is — ha — limited — limited — the parade might be wider; but you will find it apparently grow larger after a time — a time, ladies and gentlemen — and the air is, all things considered, very good. It blows over the — ha — Surrey hills. Blows over the Surrey hills. This is the Snuggery. Hum. Supported by a small subscription of the — ha — Collegiate body. In return for which — hot water — general kitchen — and little domestic advantages. Those who are habituated to the — ha — Marshalsea, are pleased to call me its father. I am accustomed to be complimented by strangers as the — ha — Father of the Marshalsea. Certainly, if years of residence may establish a claim to so — ha — honourable a title, I may accept the hum — conferred distinction. My child, ladies and gentlemen. My daughter. Born here!"

She was not ashamed of it, or ashamed of him. She was pale and frightened; but she had no other care than to soothe him and get him away, for his own dear sake. She was between him and the wondering faces, turned round upon his breast with her own face raised to his. He held her clasped in his left arm, and between whiles her low voice was heard tenderly imploring him to go away with her."

Commentary:

This text accomplishes here what the illustration by itself cannot: the utter dismay of Amy Dorrit as she struggles to apprehend what is happening to her father. The majority of the assembly do not recognise what is happening, for William Dorrit speech about the Marshalsea is inexplicable to Mr. Merdle's well-wishers.

An Unexpected After-Dinner Speech

Book II Chapter 19

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The Father of the Marshalsea, now the wealthy William Dorrit, traveller through the Alps] looked confusedly about him, and, becoming conscious of the number of faces by which he was surrounded, addressed them:

"Ladies and gentlemen, the duty — ha — devolves upon me of — hum — welcoming you to the Marshalsea! Welcome to the Marshalsea! The space is — ha — limited — limited — the parade might be wider; but you will find it apparently grow larger after a time — a time, ladies and gentlemen — and the air is, all things considered, very good. It blows over the — ha — Surrey hills. Blows over the Surrey hills. This is the Snuggery. Hum. Supported by a small subscription of the — ha — Collegiate body. In return for which — hot water — general kitchen — and little domestic advantages. Those who are habituated to the — ha — Marshalsea, are pleased to call me its father. I am accustomed to be complimented by strangers as the — ha — Father of the Marshalsea. Certainly, if years of residence may establish a claim to so — ha — honourable a title, I may accept the hum — conferred distinction. My child, ladies and gentlemen. My daughter. Born here!"

She was not ashamed of it, or ashamed of him. She was pale and frightened; but she had no other care than to soothe him and get him away, for his own dear sake. She was between him and the wondering faces, turned round upon his breast with her own face raised to his. He held her clasped in his left arm, and between whiles her low voice was heard tenderly imploring him to go away with her."

Commentary:

This text accomplishes here what the illustration by itself cannot: the utter dismay of Amy Dorrit as she struggles to apprehend what is happening to her father. The majority of the assembly do not recognise what is happening, for William Dorrit speech about the Marshalsea is inexplicable to Mr. Merdle's well-wishers.

Book II Chapter 19 - Phiz

The Night

Book II Chapter 19

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"At first her uncle was stark distracted. "O my brother! O William, William! You to go before me; you to go alone; you to go, and I to remain! You, so far superior, so distinguished, so noble; I, a poor useless creature fit for nothing, and whom no one would have missed!"

It did her, for the time, the good of having him to think of and to succour.

"Uncle, dear uncle, spare yourself, spare me!"

The old man was not deaf to the last words. When he did begin to restrain himself, it was that he might spare her. He had no care for himself; but, with all the remaining power of the honest heart, stunned so long and now awaking to be broken, he honoured and blessed her.

"O God," he cried, before they left the room, with his wrinkled hands clasped over her. "Thou seest this daughter of my dear dead brother! All that I have looked upon, with my half-blind and sinful eyes, Thou hast discerned clearly, brightly. Not a hair of her head shall be harmed before Thee. Thou wilt uphold her here to her last hour. And I know Thou wilt reward her hereafter!"

They remained in a dim room near, until it was almost midnight, quiet and sad together. At times his grief would seek relief in a burst like that in which it had found its earliest expression; but, besides that his little strength would soon have been unequal to such strains, he never failed to recall her words, and to reproach himself and calm himself. The only utterance with which he indulged his sorrow, was the frequent exclamation that his brother was gone, alone; that they had been together in the outset of their lives, that they had fallen into misfortune together, that they had kept together through their many years of poverty, that they had remained together to that day; and that his brother was gone alone, alone!

They parted, heavy and sorrowful. She would not consent to leave him anywhere but in his own room, and she saw him lie down in his clothes upon his bed, and covered him with her own hands. Then she sank upon her own bed, and fell into a deep sleep: the sleep of exhaustion and rest, though not of complete release from a pervading consciousness of affliction. Sleep, good Little Dorrit. Sleep through the night!

It was a moonlight night; but the moon rose late, being long past the full. When it was high in the peaceful firmament, it shone through half-closed lattice blinds into the solemn room where the stumblings and wanderings of a life had so lately ended. Two quiet figures were within the room; two figures, equally still and impassive, equally removed by an untraversable distance from the teeming earth and all that it contains, though soon to lie in it.

One figure reposed upon the bed. The other, kneeling on the floor, drooped over it; the arms easily and peacefully resting on the coverlet; the face bowed down, so that the lips touched the hand over which with its last breath it had bent. The two brothers were before their Father; far beyond the twilight judgment of this world; high above its mists and obscurities. — Book The Second, "Riches," conclusion of Chapter 19, "The Storming of the Castle in the Air,"

Commentary

James Mahoney in the Household Edition volume of 1873 reinterpreted this illustration as The two brothers were before their Father. However, whereas Phiz has provided plenty of contextual bric-a-brac to establish the affluence of the English travellers on the Continent (indeed, these material objects such as statues and paintings almost seem to entomb the prostrate figure), Mahoney focuses on the somberly dressed, aged upper-middle-class English gentleman who has just followed his older brother into death, freeing them both from a tawdry past and a present obsession with decorous behaviour and the cultivation of polished, sophisticated surfaces.

"The Night" is the kind of subject which tended to stimulate Browne's emblematic imagination. No doubt the idea of showing just Mr. Dorrit's arm and hand, and having the illustration center on his loving and devoted brother Frederick, formed part of Dickens' instructions, though in this regard it does not follow the text precisely, since the latter speaks repeatedly of two figures, yet the notion is consistent with the last two sentences in the chapter, especially the description of "the arms easily and peacefully resting on the coverlet, the face bowed down so that the lips touched the hand over which with its last breath it had bent". On the wall are paintings of a king and a ruined castle, the first probably representing the condition of power and eminence Dorrit has so recently imagined himself to occupy, the second the collapse of his castle in the air. A third emblematic detail is a statue of a seminude woman, probably Psyche, with her head turned to took at the butterfly on her shoulder. The butterfly as soul is a traditional emblem, and here as in the plate dealing with Dora Copperfield's death the reference is to the impending departure of the dying person's soul.

The Night

Book II Chapter 19

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"At first her uncle was stark distracted. "O my brother! O William, William! You to go before me; you to go alone; you to go, and I to remain! You, so far superior, so distinguished, so noble; I, a poor useless creature fit for nothing, and whom no one would have missed!"

It did her, for the time, the good of having him to think of and to succour.

"Uncle, dear uncle, spare yourself, spare me!"

The old man was not deaf to the last words. When he did begin to restrain himself, it was that he might spare her. He had no care for himself; but, with all the remaining power of the honest heart, stunned so long and now awaking to be broken, he honoured and blessed her.

"O God," he cried, before they left the room, with his wrinkled hands clasped over her. "Thou seest this daughter of my dear dead brother! All that I have looked upon, with my half-blind and sinful eyes, Thou hast discerned clearly, brightly. Not a hair of her head shall be harmed before Thee. Thou wilt uphold her here to her last hour. And I know Thou wilt reward her hereafter!"

They remained in a dim room near, until it was almost midnight, quiet and sad together. At times his grief would seek relief in a burst like that in which it had found its earliest expression; but, besides that his little strength would soon have been unequal to such strains, he never failed to recall her words, and to reproach himself and calm himself. The only utterance with which he indulged his sorrow, was the frequent exclamation that his brother was gone, alone; that they had been together in the outset of their lives, that they had fallen into misfortune together, that they had kept together through their many years of poverty, that they had remained together to that day; and that his brother was gone alone, alone!

They parted, heavy and sorrowful. She would not consent to leave him anywhere but in his own room, and she saw him lie down in his clothes upon his bed, and covered him with her own hands. Then she sank upon her own bed, and fell into a deep sleep: the sleep of exhaustion and rest, though not of complete release from a pervading consciousness of affliction. Sleep, good Little Dorrit. Sleep through the night!

It was a moonlight night; but the moon rose late, being long past the full. When it was high in the peaceful firmament, it shone through half-closed lattice blinds into the solemn room where the stumblings and wanderings of a life had so lately ended. Two quiet figures were within the room; two figures, equally still and impassive, equally removed by an untraversable distance from the teeming earth and all that it contains, though soon to lie in it.

One figure reposed upon the bed. The other, kneeling on the floor, drooped over it; the arms easily and peacefully resting on the coverlet; the face bowed down, so that the lips touched the hand over which with its last breath it had bent. The two brothers were before their Father; far beyond the twilight judgment of this world; high above its mists and obscurities. — Book The Second, "Riches," conclusion of Chapter 19, "The Storming of the Castle in the Air,"

Commentary

James Mahoney in the Household Edition volume of 1873 reinterpreted this illustration as The two brothers were before their Father. However, whereas Phiz has provided plenty of contextual bric-a-brac to establish the affluence of the English travellers on the Continent (indeed, these material objects such as statues and paintings almost seem to entomb the prostrate figure), Mahoney focuses on the somberly dressed, aged upper-middle-class English gentleman who has just followed his older brother into death, freeing them both from a tawdry past and a present obsession with decorous behaviour and the cultivation of polished, sophisticated surfaces.

"The Night" is the kind of subject which tended to stimulate Browne's emblematic imagination. No doubt the idea of showing just Mr. Dorrit's arm and hand, and having the illustration center on his loving and devoted brother Frederick, formed part of Dickens' instructions, though in this regard it does not follow the text precisely, since the latter speaks repeatedly of two figures, yet the notion is consistent with the last two sentences in the chapter, especially the description of "the arms easily and peacefully resting on the coverlet, the face bowed down so that the lips touched the hand over which with its last breath it had bent". On the wall are paintings of a king and a ruined castle, the first probably representing the condition of power and eminence Dorrit has so recently imagined himself to occupy, the second the collapse of his castle in the air. A third emblematic detail is a statue of a seminude woman, probably Psyche, with her head turned to took at the butterfly on her shoulder. The butterfly as soul is a traditional emblem, and here as in the plate dealing with Dora Copperfield's death the reference is to the impending departure of the dying person's soul.

Book II Chapter 19 - James Mahoney

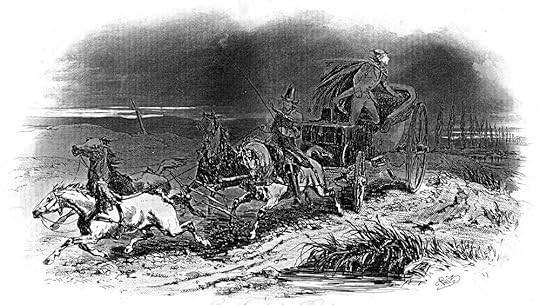

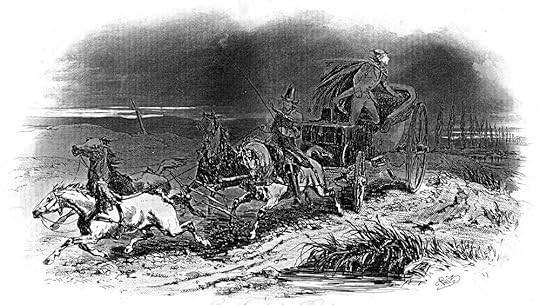

"The sun had gone down full four hours, and it was later than most travellers would like it to be for finding themselves outside the walls of Rome, when Mr. Dorrit's carriage, still on its last wearisome stage, rattled over the solitary Campagna."

Book II Chapter 19

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"The sun had gone down full four hours, and it was later than most travellers would like it to be for finding themselves outside the walls of Rome, when Mr. Dorrit's carriage, still on its last wearisome stage, rattled over the solitary Campagna. The savage herdsmen and the fierce-looking peasants who had chequered the way while the light lasted, had all gone down with the sun, and left the wilderness blank. At some turns of the road, a pale flare on the horizon, like an exhalation from the ruin-sown land, showed that the city was yet far off; but this poor relief was rare and short-lived. The carriage dipped down again into a hollow of the black dry sea, and for a long time there was nothing visible save its petrified swell and the gloomy sky.

Mr. Dorrit, though he had his castle-building to engage his mind, could not be quite easy in that desolate place. He was far more curious, in every swerve of the carriage, and every cry of the postilions, than he had been since he quitted London. The valet on the box evidently quaked. The Courier in the rumble was not altogether comfortable in his mind. As often as Mr. Dorrit let down the glass and looked back at him (which was very often), he saw him smoking John Chivery out, it is true, but still generally standing up the while and looking about him, like a man who had his suspicions, and kept upon his guard. Then would Mr. Dorrit, pulling up the glass again, reflect that those postilions were cut-throat looking fellows, and that he would have done better to have slept at Civita Vecchia, and have started betimes in the morning. But, for all this, he worked at his castle in the intervals."

Commentary:

Back from a hurried London trip, like Charles Dickens in December 1844 when he briefly visited his publishers to superintend the publication of the second Christmas Book, The Chimes, through the press and read the novella aloud to a select audience at 58 Lincoln's Inn Fields on the evening of December 3, 1844, William Dorrit must be exhausted. Called away from Rome to manage his financial affairs, he has had unsettling interviews with Mrs. Clennam and John Chivery, the latter being an embarrassing reminder of his former identity as Father of the Marshalsea. Now, still shocked by threat of exposure of his former life, he returns to the family in Rome, but the dark plate is full of foreboding.

A useful point of comparison is not an illustration for Little Dorrit, but On the Dark Road, the steel-engraving for Chapter 55 of Dombey and Son by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) twenty-five years earlier. According to Valerie Lester Browne, this was Phiz's first attempt at a classic 'dark plate', in this case to show the futility of the villainous Carker's trying to cheat death as he returns to England to confront Mr. Dombey. The 1848 illustration, moreover, engages the viewer with the sharpness and vivacity of the figures and the prancing horses — horses having been from his earliest compositions one of Phiz's strengths. Better reproductions of this delightful illustration convey the aerial perspective through making clear the line of Lombardy poplars running off the horizon, upper right.

For the illustration, 'On a dark road,' Phiz turned the plate horizontally and used a ruling machine, which pushed a bank of needles across the wax ground on the plate, creating a background of narrow stripes, akin to mezzo tinting. (The technique is sometimes referred to as 'machine tinting'.) He then drew into dark areas to make them blacker and produced a variety of greys by stopping-out other areas. To retain the dazzling whites, he burnished away the ruled lines and stopped out those areas completely on the first and all subsequent visits to the acid.

The dark plate becomes ubiquitous among Browne's etchings in the late forties and through the fifties, and it is as well to explain the technique at this point. In its most basic form it provides a way of adding mechanically ruled, very closely spaced lines to the steel in order to produce a "tint," a grayish shading of the plate. It is this simple method that Browne occasionally used for authors other than Dickens. But in general he made more subtle and complex use of the dark plate. . . . . The highlights, areas which were to remain white, would be stopped out with varnish, and then the biting could commence. Those areas which were to be lightest in tint would be stopped out after a short bite, the next lightest after a longer bite, and so on down to the very blackest areas — which would never, except where wholly exposed by the needle, become totally black, but would shimmer with the tiny lights of the unexposed bits between the ruled lines; the darkest sky in On the Dark Road has these little lights, while the dark parts of the puddle have none, apparently having been exposed to the acid by the needle rather than the ruling machine. [Steig, p. 106-107]

An ominous and menacing atmosphere surrounds each carriage as the onset of darkens implies impending doom, although the characters and horses in the Phiz engraving are more sharply delineated than the driver, passenger, and horses passing rapidly through Roman Campagna in the Mahoney wood-engraving, which has a rougher, less polished and precise effect, coinciding with the coarseness of the landscape and the peasantry which Dickens describes in the accompanying text. In particular, Phiz's horses are far more dynamic and precisely drawn than Mahoney's two, highlighted horses of much more solid build. Moreover, whereas Phiz has the open coach or barouche approaching the viewer, with an apparent break in the clouds throwing the face of the standing figure, the lead horse, the body of the postilion's horse, and the vegetation at the side of the road (lower right) into fleeting sunlight in a powerful chiaroscuro that contributes to the melodramatic effect of the illustration as a whole as dark and light compete for dominance in the plate. The effect of the Mahoney wood-engraving is somewhat different. As the closed carriage moves away from the viewer, very little detail about the carriage or the countryside evident is evident because the darkness is so intense. Indeed, the greatest point of interest seems to be the sky and the light-colored horses to the upper left as Mahoney has thrown the second postilion (holding the whip aloft), the obscured driver, and the passenger with his hand on the window ledge in darkness. In contrast, he shows the back of the first postilion, the road, the guard, several blocks of sawn wood, and the pond (lower center), at least providing aerial perspective through the sharpness of the foreground and the precision with which Mahoney has described the turning carriage wheels in the center. William Dorrit's hopes for a better future, his "castle in the air," Mahoney represents as the light on the horizon, upper left, so connected with the right-to-left movement of the horses and carriage that the reader fails to attend to the ominous bank of cloud, upper right. Given the technical limitations of the composite woodblock engraving, Mahoney has achieved a suitably gloomy atmosphere that prepares the reader for William Dorrit's death at the close of the chapter.

On the dark road

Phiz

"The sun had gone down full four hours, and it was later than most travellers would like it to be for finding themselves outside the walls of Rome, when Mr. Dorrit's carriage, still on its last wearisome stage, rattled over the solitary Campagna."

Book II Chapter 19

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"The sun had gone down full four hours, and it was later than most travellers would like it to be for finding themselves outside the walls of Rome, when Mr. Dorrit's carriage, still on its last wearisome stage, rattled over the solitary Campagna. The savage herdsmen and the fierce-looking peasants who had chequered the way while the light lasted, had all gone down with the sun, and left the wilderness blank. At some turns of the road, a pale flare on the horizon, like an exhalation from the ruin-sown land, showed that the city was yet far off; but this poor relief was rare and short-lived. The carriage dipped down again into a hollow of the black dry sea, and for a long time there was nothing visible save its petrified swell and the gloomy sky.

Mr. Dorrit, though he had his castle-building to engage his mind, could not be quite easy in that desolate place. He was far more curious, in every swerve of the carriage, and every cry of the postilions, than he had been since he quitted London. The valet on the box evidently quaked. The Courier in the rumble was not altogether comfortable in his mind. As often as Mr. Dorrit let down the glass and looked back at him (which was very often), he saw him smoking John Chivery out, it is true, but still generally standing up the while and looking about him, like a man who had his suspicions, and kept upon his guard. Then would Mr. Dorrit, pulling up the glass again, reflect that those postilions were cut-throat looking fellows, and that he would have done better to have slept at Civita Vecchia, and have started betimes in the morning. But, for all this, he worked at his castle in the intervals."

Commentary:

Back from a hurried London trip, like Charles Dickens in December 1844 when he briefly visited his publishers to superintend the publication of the second Christmas Book, The Chimes, through the press and read the novella aloud to a select audience at 58 Lincoln's Inn Fields on the evening of December 3, 1844, William Dorrit must be exhausted. Called away from Rome to manage his financial affairs, he has had unsettling interviews with Mrs. Clennam and John Chivery, the latter being an embarrassing reminder of his former identity as Father of the Marshalsea. Now, still shocked by threat of exposure of his former life, he returns to the family in Rome, but the dark plate is full of foreboding.

A useful point of comparison is not an illustration for Little Dorrit, but On the Dark Road, the steel-engraving for Chapter 55 of Dombey and Son by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) twenty-five years earlier. According to Valerie Lester Browne, this was Phiz's first attempt at a classic 'dark plate', in this case to show the futility of the villainous Carker's trying to cheat death as he returns to England to confront Mr. Dombey. The 1848 illustration, moreover, engages the viewer with the sharpness and vivacity of the figures and the prancing horses — horses having been from his earliest compositions one of Phiz's strengths. Better reproductions of this delightful illustration convey the aerial perspective through making clear the line of Lombardy poplars running off the horizon, upper right.

For the illustration, 'On a dark road,' Phiz turned the plate horizontally and used a ruling machine, which pushed a bank of needles across the wax ground on the plate, creating a background of narrow stripes, akin to mezzo tinting. (The technique is sometimes referred to as 'machine tinting'.) He then drew into dark areas to make them blacker and produced a variety of greys by stopping-out other areas. To retain the dazzling whites, he burnished away the ruled lines and stopped out those areas completely on the first and all subsequent visits to the acid.

The dark plate becomes ubiquitous among Browne's etchings in the late forties and through the fifties, and it is as well to explain the technique at this point. In its most basic form it provides a way of adding mechanically ruled, very closely spaced lines to the steel in order to produce a "tint," a grayish shading of the plate. It is this simple method that Browne occasionally used for authors other than Dickens. But in general he made more subtle and complex use of the dark plate. . . . . The highlights, areas which were to remain white, would be stopped out with varnish, and then the biting could commence. Those areas which were to be lightest in tint would be stopped out after a short bite, the next lightest after a longer bite, and so on down to the very blackest areas — which would never, except where wholly exposed by the needle, become totally black, but would shimmer with the tiny lights of the unexposed bits between the ruled lines; the darkest sky in On the Dark Road has these little lights, while the dark parts of the puddle have none, apparently having been exposed to the acid by the needle rather than the ruling machine. [Steig, p. 106-107]

An ominous and menacing atmosphere surrounds each carriage as the onset of darkens implies impending doom, although the characters and horses in the Phiz engraving are more sharply delineated than the driver, passenger, and horses passing rapidly through Roman Campagna in the Mahoney wood-engraving, which has a rougher, less polished and precise effect, coinciding with the coarseness of the landscape and the peasantry which Dickens describes in the accompanying text. In particular, Phiz's horses are far more dynamic and precisely drawn than Mahoney's two, highlighted horses of much more solid build. Moreover, whereas Phiz has the open coach or barouche approaching the viewer, with an apparent break in the clouds throwing the face of the standing figure, the lead horse, the body of the postilion's horse, and the vegetation at the side of the road (lower right) into fleeting sunlight in a powerful chiaroscuro that contributes to the melodramatic effect of the illustration as a whole as dark and light compete for dominance in the plate. The effect of the Mahoney wood-engraving is somewhat different. As the closed carriage moves away from the viewer, very little detail about the carriage or the countryside evident is evident because the darkness is so intense. Indeed, the greatest point of interest seems to be the sky and the light-colored horses to the upper left as Mahoney has thrown the second postilion (holding the whip aloft), the obscured driver, and the passenger with his hand on the window ledge in darkness. In contrast, he shows the back of the first postilion, the road, the guard, several blocks of sawn wood, and the pond (lower center), at least providing aerial perspective through the sharpness of the foreground and the precision with which Mahoney has described the turning carriage wheels in the center. William Dorrit's hopes for a better future, his "castle in the air," Mahoney represents as the light on the horizon, upper left, so connected with the right-to-left movement of the horses and carriage that the reader fails to attend to the ominous bank of cloud, upper right. Given the technical limitations of the composite woodblock engraving, Mahoney has achieved a suitably gloomy atmosphere that prepares the reader for William Dorrit's death at the close of the chapter.

On the dark road

Phiz

Book II Chapter 19 - James Mahoney

The two brothers were before their Father

Book II Chapter 19

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

"It was a moonlight night; but the moon rose late, being long past the full. When it was high in the peaceful firmament, it shone through half-closed lattice blinds into the solemn room where the stumblings and wanderings of a life had so lately ended. Two quiet figures were within the room; two figures, equally still and impassive, equally removed by an untraversable distance from the teeming earth and all that it contains, though soon to lie in it.

One figure reposed upon the bed. The other, kneeling on the floor, drooped over it; the arms easily and peacefully resting on the coverlet; the face bowed down, so that the lips touched the hand over which with its last breath it had bent. The two brothers were before their Father; far beyond the twilight judgment of this world; high above its mists and obscurities."

Commentary:

Visiting Rome on the nineteenth-century, bourgeois equivalent of the eighteenth-century, aristocratic Grand Tour, William Dorrit, Amy's father, is suddenly unwell, ironically just before he is about to commit the great misstep of proposing to his daughters' governess (the naïve family's companion and instructor), the sententious and dictatorial Mrs. General. At Mr. Merdle's farewell reception, Mr. Dorrit becomes confused, and reverts to his former identity as The Father of the Marshalsea when he delivers a farewell address before Rome's English expatriate community. The present scene of his death after a sharp decline is ten days after the reception. He dies in the family's lavishly furnished rooms, attended by his younger brother Frederick, the musician, who then dies himself. Thus, Mahoney has captured the highly sentimental moment when Frederick (depicted) dies, leaving Little Dorrit a complete orphan. The illustration is so highly effective that Harper and Brothers chose it for the frontispiece in the New York volume.

The Mahoney illustration is a re-interpretation of one of the original serial's illustration, namely Phiz's The Night, the second illustration for the sixteenth monthly number, the first being of the dinner at which Mr. Dorrit experiences a mental collapse (also Book Two, Chapter 19, originally March 1856), An Unexpected After-Dinner Speech. However, whereas Phiz has provided plenty of contextual bric-a-brac to establish the affluence of the English travelers (indeed, these material objects almost seem to entomb the prostrate figure), Mahoney focuses on the somberly dressed, aged upper-middle-class English gentleman who has just followed his older brother into death, freeing them both from a tawdry past and a present obsession with decorous behavior and the cultivation of polished, sophisticated surfaces.

The two brothers were before their Father

Book II Chapter 19

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

"It was a moonlight night; but the moon rose late, being long past the full. When it was high in the peaceful firmament, it shone through half-closed lattice blinds into the solemn room where the stumblings and wanderings of a life had so lately ended. Two quiet figures were within the room; two figures, equally still and impassive, equally removed by an untraversable distance from the teeming earth and all that it contains, though soon to lie in it.

One figure reposed upon the bed. The other, kneeling on the floor, drooped over it; the arms easily and peacefully resting on the coverlet; the face bowed down, so that the lips touched the hand over which with its last breath it had bent. The two brothers were before their Father; far beyond the twilight judgment of this world; high above its mists and obscurities."

Commentary:

Visiting Rome on the nineteenth-century, bourgeois equivalent of the eighteenth-century, aristocratic Grand Tour, William Dorrit, Amy's father, is suddenly unwell, ironically just before he is about to commit the great misstep of proposing to his daughters' governess (the naïve family's companion and instructor), the sententious and dictatorial Mrs. General. At Mr. Merdle's farewell reception, Mr. Dorrit becomes confused, and reverts to his former identity as The Father of the Marshalsea when he delivers a farewell address before Rome's English expatriate community. The present scene of his death after a sharp decline is ten days after the reception. He dies in the family's lavishly furnished rooms, attended by his younger brother Frederick, the musician, who then dies himself. Thus, Mahoney has captured the highly sentimental moment when Frederick (depicted) dies, leaving Little Dorrit a complete orphan. The illustration is so highly effective that Harper and Brothers chose it for the frontispiece in the New York volume.

The Mahoney illustration is a re-interpretation of one of the original serial's illustration, namely Phiz's The Night, the second illustration for the sixteenth monthly number, the first being of the dinner at which Mr. Dorrit experiences a mental collapse (also Book Two, Chapter 19, originally March 1856), An Unexpected After-Dinner Speech. However, whereas Phiz has provided plenty of contextual bric-a-brac to establish the affluence of the English travelers (indeed, these material objects almost seem to entomb the prostrate figure), Mahoney focuses on the somberly dressed, aged upper-middle-class English gentleman who has just followed his older brother into death, freeing them both from a tawdry past and a present obsession with decorous behavior and the cultivation of polished, sophisticated surfaces.

Book II Chapter 20 - Sol Eytinge Jr.

Miss Wade and Tattycorum

Book II Chapter 20

Sol Eytinge Jr.

The Diamond Edition 1871

Commentary:

In the fifteenth character study to complement Dickens's narrative, "Miss Wade and Tattycoram," Eytinge contrasts the stubborn adolescent (her nickname based on Coram's Foundling Hospital) taken up by the Meagles as a servant for their spoiled adolescent daughter and the psychologically disturbed, but "handsome" Miss Wade in the latter's rented rooms in Calais as Clennam prosecutes his search of Blandois. The relevant passage for this dual character study (the perspective presumably being Clennam's) is probably this, as Tattycoram — to Miss Wade, "Harriet" — enters and finds Arthur Clennam conversing with her mistress:

Are they well, sir?"

"Who?"

She stopped herself in saying what would have been "all of them"; glanced at Miss Wade; and said "Mr. and Mrs. Meagles."

"They were, when I last heard of them. They are not at home. By the way, let me ask you. Is it true that you were seen there?"

"Where? Where does any one say I was seen?" returned the girl, sullenly casting down her eyes.

"Looking in at the garden gate of the cottage."

"No," said Miss Wade. "She has never been near it."

"You are wrong, then," said the girl. "I went down there the last time we were in London. I went one afternoon when you left me alone. And I did look in."

"You poor-spirited girl," returned Miss Wade with infinite contempt; "does all our companionship, do all our conversations, do all your old complainings, tell for so little as that?"

"There was no harm in looking in at the gate for an instant," said the girl. "I saw by the windows that the family were not there."

"Why should you go near the place?"

"Because I wanted to see it. Because I felt that I should like to look at it again."

As each of the two handsome faces looked at the other, Clennam felt how each of the two natures must be constantly tearing the other to pieces.

"Oh!" said Miss Wade, coldly subduing and removing her glance; "if you had any desire to see the place where you led the life from which I rescued you because you had found out what it was, that is another thing. But is that your truth to me? Is that your fidelity to me? Is that the common cause I make with you? You are not worth the confidence I have placed in you. You are not worth the favor I have shown you. You are no higher than a spaniel, and had better go back to the people who did worse than whip you."

"If you speak so of them with any one else by to hear, you'll provoke me to take their part," said the girl.

"Go back to them," Miss Wade retorted — "go back to them."

"You know very well," retorted Harriet in her turn, "that I won't go back to them. You know very well that I have thrown them off, and never can, never shall, never will, go back to them. Let them alone, then, Miss Wade."

"You prefer their plenty to your less fat living here," she rejoined. You exalt them, and slight me. What else should I have expected? I ought to have known it."

"It's not so," said the girl, flushing high, "and you don't say what you mean. I know what you mean. You are reproaching me, underhanded, with having nobody but you to look to. And because I have nobody but you to look to, you think you are to make me do, or not do, everything you please, and are to put any affront upon me. You are as bad as they were, every bit. But I will not be quite tamed, and made submissive. I will say again that I went to look at the house, because I had often thought that I should like to see it once more. I will ask again how they are, because I once liked them and at times thought they were kind to me."

Hereupon Clennam said that he was sure they would still receive her kindly, if she should ever desire to return.

"Never!" said the girl passionately. "I shall never do that. Nobody knows that better than Miss Wade, though she taunts me because she has made me her dependent. And I know I am so; and I know she is overjoyed when she can bring it to my mind."

"A good pretence!" said Miss Wade, with no less anger, haughtiness, and bitterness; "but too threadbare to cover what I plainly see in this. My poverty will not bear competition with their money. Better go back at once, better go back at once, and have done with it!"

Arthur Clennam looked at them, standing a little distance asunder in the dull confined room, each proudly cherishing her own anger; each, with a fixed determination, torturing her own breast, and torturing the other's. He said a word or two of leave-taking; but Miss Wade barely inclined her head, and Harriet, with the assumed humiliation of an abject dependent and serf (but not without defiance for all that), made as if she were too low to notice or to be noticed.

Little of Miss Wade's anguish, or her rancorous jealousy of Pet Meagles, or her bitterness at having been thrown over by Gowan are evident in Eytinge's illustration; rather, she sternly and with mild surprise regards the gloomy Harriet as the girl (left, in servant's apron) confesses having taken an interest in the welfare of the Meagles after leaving them. Eytinge's Miss Wade is thoroughly respectable in dress and deportment, severe, and even dignified, but hardly handsome — and hardly the passionate misanthrope of Dickens's text. Likewise, Eytinge's figure of Harriet Beadle ("Tattycoram") suggests the girl's generalized resentment of Miss Wade, but nothing of her fine features, albeit features marred by a sense of being continually put upon.

Miss Wade and Tattycorum

Book II Chapter 20

Sol Eytinge Jr.

The Diamond Edition 1871

Commentary:

In the fifteenth character study to complement Dickens's narrative, "Miss Wade and Tattycoram," Eytinge contrasts the stubborn adolescent (her nickname based on Coram's Foundling Hospital) taken up by the Meagles as a servant for their spoiled adolescent daughter and the psychologically disturbed, but "handsome" Miss Wade in the latter's rented rooms in Calais as Clennam prosecutes his search of Blandois. The relevant passage for this dual character study (the perspective presumably being Clennam's) is probably this, as Tattycoram — to Miss Wade, "Harriet" — enters and finds Arthur Clennam conversing with her mistress:

Are they well, sir?"

"Who?"

She stopped herself in saying what would have been "all of them"; glanced at Miss Wade; and said "Mr. and Mrs. Meagles."

"They were, when I last heard of them. They are not at home. By the way, let me ask you. Is it true that you were seen there?"

"Where? Where does any one say I was seen?" returned the girl, sullenly casting down her eyes.

"Looking in at the garden gate of the cottage."

"No," said Miss Wade. "She has never been near it."

"You are wrong, then," said the girl. "I went down there the last time we were in London. I went one afternoon when you left me alone. And I did look in."

"You poor-spirited girl," returned Miss Wade with infinite contempt; "does all our companionship, do all our conversations, do all your old complainings, tell for so little as that?"

"There was no harm in looking in at the gate for an instant," said the girl. "I saw by the windows that the family were not there."

"Why should you go near the place?"

"Because I wanted to see it. Because I felt that I should like to look at it again."

As each of the two handsome faces looked at the other, Clennam felt how each of the two natures must be constantly tearing the other to pieces.

"Oh!" said Miss Wade, coldly subduing and removing her glance; "if you had any desire to see the place where you led the life from which I rescued you because you had found out what it was, that is another thing. But is that your truth to me? Is that your fidelity to me? Is that the common cause I make with you? You are not worth the confidence I have placed in you. You are not worth the favor I have shown you. You are no higher than a spaniel, and had better go back to the people who did worse than whip you."

"If you speak so of them with any one else by to hear, you'll provoke me to take their part," said the girl.

"Go back to them," Miss Wade retorted — "go back to them."

"You know very well," retorted Harriet in her turn, "that I won't go back to them. You know very well that I have thrown them off, and never can, never shall, never will, go back to them. Let them alone, then, Miss Wade."

"You prefer their plenty to your less fat living here," she rejoined. You exalt them, and slight me. What else should I have expected? I ought to have known it."